Abstract

Purpose:

We identify correlates and clinical outcomes of cystitis cystica, a poorly understood chronic inflammatory bladder change, in women with recurrent urinary tract infections.

Materials and Methods:

A retrospective, observational cohort of women with recurrent urinary tract infections who underwent cystoscopy (n=138) from 2015 to 2018 were identified using electronic medical records. Cystitis cystica status was abstracted from cystoscopy reports and correlations were identified by logistic regression. Urinary tract infection–free survival time associated with cystitis cystica was evaluated by Cox proportional hazards regression. Exact logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with changes to cystitis cystica lesions on repeat cystoscopy. Biopsies of cystitis cystica lesions were examined by routine histology and immunofluorescence.

Results:

Fifty-three patients (38%) had cystitis cystica on cystoscopy. Cystitis cystica was associated with postmenopausal status (OR: 5.53, 95% CI: 1.39–37.21), pelvic floor myofascial pain (6.82, 1.78–45.04), having ≥4 urinary tract infections in the past year (2.28, 1.04–5.09), and a shorter time to next urinary tract infection (HR: 1.54, 95% CI: 1.01–2.35). Forty-two patients (82%) demonstrated improvement or resolution of lesions. Ten/11 (91%) biopsied cystitis cystica lesions were tertiary lymphoid tissue with germinal centers and resembled follicular cystitis.

Conclusions:

Cystitis cystica lesions were associated with postmenopausal status, pelvic floor myofascial pain, and number of urinary tract infections in the prior year and predicted worse recurrent urinary tract infection outcomes. Cystitis cystica lesions are tertiary lymphoid tissue/follicular cystitis that may improve or resolve over time with treatment. Identifying cystitis cystica in recurrent urinary tract infection patients may be useful in informing future urinary tract infection risk and tailoring appropriate treatment strategies.

Study Need and Importance:

Postmenopausal women are particularly susceptible to recurrent urinary tract infections (rUTIs). There remains a great need to understand the clinical factors that drive the increase in susceptibility and frequency of rUTIs in this population, and we sought to identify potential pathological correlates. Previous work had identified that aged female mouse bladders develop lymphoid aggregates, and we systematically defined these structures as bladder tertiary lymphoid tissue (bTLT). bTLT formed with increasing age and following reproductive senescence, formed bona fide germinal centers, and was associated with a significant increase in rUTIs.

What We Found:

Bladders of postmenopausal women harbor inflammatory lesions evident as cystitis cystica (CC) on cystoscopy that were structurally bTLT in form and composition and that are better described in pathologic terms as follicular cystitis. To further understand the relationship between CC and rUTIs, we performed a retrospective and observational analysis of a cohort of 138 women with culture-proven rUTIs and who underwent cystoscopy. Our study showed that approximately 40% of women had bTLT/CC lesions and were significantly more likely to have multiple rUTIs in a given year. Furthermore, the presence of these lesions was strongly associated with a shorter time to next urinary tract infection (UTI). Tertiary lymphoid tissue in postmenopausal bladders have been shown to be associated with colocalization of Escherichia coli species. The presence of tertiary lymphoid tissues may potentiate overexuberant or ineffective immune responses that promote inflammation rather than resolution of UTIs. We could demonstrate that a multimodal regimen of therapy, which was successful in limiting UTIs, showed regression of bTLT lesions upon repeat cystoscopy.

Limitations:

Limitations of this study were the overall small sample size of women and a lack of standardized methods to cystoscopically assess the severity of CC. Developing a validated severity scale would improve CC lesion monitoring over time.

Interpretation of Patient Care:

We suggest that identifying CC in patients with rUTI may be useful in stratifying future UTI risk and tailoring appropriate treatment strategies (see Figure).

Keywords: urinary tract infections, menopause, urinary bladder, tertiary lymphoid structures, cystitis

Graphical Abstract

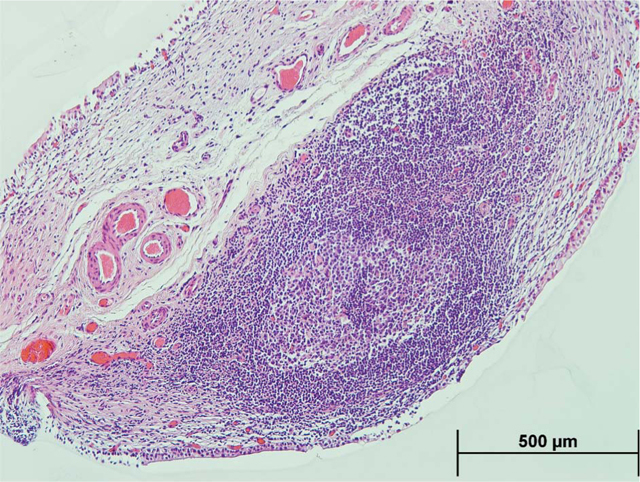

Figure. Representative hematoxylin and eosin image of lymphoid tissues with germinal center in cystitis cystica biopsies.

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are the most common infection in women, affecting at least half of all women during their lifetime and costing over $2 billion per year in the U.S.1 UTIs frequently recur (rUTIs) within 6–12 months after an initial infection.2 Postmenopausal women are particularly susceptible to rUTIs.3 While the pathogenesis of the most common uropathogens, such as Escherichia coli, has been well studied, less is known about the immune response to UTIs, clinical factors that influence this response, and how the immune response influences susceptibility to future infections.

Immune responses to a prior UTI likely play a significant role in promoting rUTIs. Mouse models of UTIs demonstrate that severe bladder inflammation predisposes to more severe and chronic infections from uropathogens.4 Adaptive immune responses to UTIs are not well understood, and in humans, few studies have examined immunological factors that may influence risk of recurrent infection. Furthermore, aging and menopause are associated with “inflammaging,” with the immune system less effective at eliminating pathogens while simultaneously promoting excess and prolonged inflammation.5 The higher UTI recurrence rate in older women could therefore be related to dysregulated immune responses to infection. Another factor that contributes to the high risk of UTIs in postmenopausal women is estrogen, which has been shown to play a protective role against UTIs.6 Lower estrogen levels after menopause increase the risk of UTIs. Vaginal estrogen therapy, which has low systemic absorption, is effective at reducing UTIs and inflammation in the urinary tract of postmenopausal women.

Cystoscopy is used to identify sources of lower urinary tract symptoms and potential niduses for rUTIs. One common cystoscopy finding in postmenopausal women is cystitis cystica (CC), which appears as multiple mucosal cysts or nodules that may be red, yellow, pink, or gray in appearance.7 Grossly, lesions described as cystitis cystica, cystitis glandularis, and follicular cystitis (FC) may appear similar, but biopsies of these lesions are not frequently performed to confirm the specific inflammatory pathology.8 It is currently unknown why some patients develop these inflammatory changes while others do not and whether the presence of CC impacts the pathogenic cycle of rUTIs.

We utilized a series of retrospectively assembled clinical studies and archived samples to address the following objectives: (1) identify clinical factors associated with the presence of CC on cystoscopy in women with rUTIs; (2) determine whether CC is associated with worse rUTI outcomes; (3) evaluate whether CC lesions resolve over time; and (4) begin to explore pathological mechanisms of CC and rUTIs by characterizing immune infiltrates in biopsies of CC lesions.

METHODS

Patient Population

All studies were approved by the Washington University School of Medicine (WUSM) Institutional Review Board (IRB No. 201712113, 201901033, and 20190534). Patient records were retrospectively identified using billing records for “cystourethroscopy” (hereafter referred to as “cystoscopy”) from 2015 to 2018, and patient demographics, medical history, and cystoscopy findings were manually abstracted to a REDCap database by 3 investigators. Inclusion criteria for all studies (objectives 1–4) were female, ≥18 years old, and evidence of rUTIs (defined as at least 2 symptomatic, culture-positive UTIs within 6 months or 3 within 1 year based on urine culture records) in the year before their first cystoscopy. Patients with bladder cancer were excluded. Data from a subset of patients who had CC on initial cystoscopy and later had a second cystoscopy were included in the study of factors related to CC improvement/resolution (objective 3), and data from a further subset of patients with CC who had a bladder biopsy were included in the histopathological study of CC (objective 4).

Data Collection

Pelvic floor prolapse was staged using the POP-Q (pelvic organ prolapse quantification) system. Patients were considered to have pelvic floor myofascial pain (PFMP) based on standardized exam and physician’s assessment. For the subset of patients with CC and a repeat cystoscopy, procedure notes were abstracted to classify CC lesions as “no change,” “improved,” or “resolved” (grouped as “improved or resolved” in the analysis). Use of UTI preventive treatments and antibiotics for ≥7 days for an acute UTI episode between cystoscopies was noted.

Bladder Biopsy Samples

A subset of patients known to have CC (by office cystoscopy) were consented to provide biopsy specimens of CC lesions while undergoing clinically indicated gynecologic surgery or exam under anesthesia. Separate specimens were sent for clinical pathology and for research. Biopsies were fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 5 μm thickness. Sections were stained with anti-CD3, anti-CD20, and anti-CD21 antibodies, and detected with AlexaFluor-conjugated secondary anti-bodies and Hoescht dye. Images were acquired using Zeiss Axio Imager M2 microscope with a Hamamatsu Flash4.0 camera and Zeiss Zen Pro software.

Statistics

Statistical analyses and data visualization were performed in R 3.6.1, Graphpad Prism v8, or SAS version 9.4. R packages used for data analysis were tidyverse, glm, survival, gtsummary, and ggfortify. Clinical characteristics of patients with and without CC were compared using Mann-Whitney U-test, χ2 test, and Fisher’s exact test. Odds ratios were calculated adjusting for menopausal status, presence of PFMP, and having ≥4 UTIs in the 12 months prior to cystoscopy (as binary variables) using logistic regression. To investigate whether CC is associated with UTI recurrence, survival analyses were conducted using log-rank tests and Cox proportional hazards regression adjusted for number of UTIs in the 12 months before cystoscopy (as a continuous variable). Time at risk for UTI following cystoscopy was calculated from the date of patients’ initial cystoscopy to the date of their first culture-positive, symptomatic UTI after cystoscopy or their last documented UTI-free contact (appointment, telephone, or electronic patient messaging), whichever came first. For CC patients with repeat cystoscopies, use of UTI prevention treatments and antibiotics for ≥7 days for an acute UTI episode was compared between patients with no change or worsening of their CC lesion over time to those whose lesion improved or resolved using exact logistic regression and Firth’s penalized likelihood regression, as appropriate. Models were adjusted for time between cystoscopies as 1 continuous term. P < .05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Factors Associated With CC

Over the 3-year study period, 464 women aged ≥18 had at least 1 cystoscopy procedure, and 138 (30%) patients met inclusion criteria for culture-positive, symptomatic rUTIs. Cystoscopy procedure notes described bladder changes consistent with CC in 53 (38%) of these 138 rUTI patients. Clinical characteristics of patients with and without CC are presented in Table 1. Compared to patients without CC, those with CC were significantly older (median 71, IQR 63, 75 vs median 66, IQR 55, 76; P = .035), had a higher number of UTIs in the prior 12 months (median 4, IQR 3, 5 vs median 3, IQR 1, 4; P = .042), were more likely to be postmenopausal (96% vs 82%; P =.046), and were more likely to have PFMP (94% vs 78%; P = .006; Table 1). Postmenopausal status (OR 5.53, 95% CI 1.39–37.21), PFMP (6.82, 1.78–45.04), and having ≥4 UTIs in the past 12 months (2.28, 1.04–5.09) were significantly associated with CC.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients With Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections Stratified by Those With vs Without Cystitis Cystica

| No CC n=85 | CC n=53 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age, median (IQR), ya | 66 (55,76) | 71 (63,75) | .035 (Mann-Whitney U-test) |

| White race, No. (%) | 80 (94) | 44 (86) | .13 (Fisher’s exact test) |

| UTIs in past 12 mo, median (IQR)a | 3 (2, 4) | 4 (3, 5) | .042 (Mann-Whitney U-test) |

| Postmenopausal, No. (%) | 67 (82) | 50 (96) | .035 (Fisher’s exact test) |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | 66 (78) | 39 (74) | .7 (Fisher’s exact test) |

| Immunosuppression, No. (%) | 17 (20) | 4 (7.7) | .085 (Fisher’s exact test) |

| Neurogenic bladder, No. (%) | 5(6) | 1 (1.9) | .4 (Fisher’s exact test) |

| Intermittent or indwelling catheter, No. (%) | 15 (18) | 8 (15) | .8 (Fisher’s exact test) |

| Pelvic floor myofascial pain, No. (%) | 62 (78) | 45 (94) | .003 (Fisher’s exact test) |

| Urinary incontinence, No. (%) | 41 (48) | 29 (56) | .5 (Fisher’s exact test) |

| PVR, median (IQR)a | 60 (25,170) | 70 (40,174) | .3 (Mann-Whitney U-test) |

| Prolapse (all types), No. (%) | 19 (23) | 19 (37) | .13 (Fisher’s exact test) |

| Anterior prolapse, No. (%) | 1 (12) | 11 (21) | .2 (Fisher’s exact test) |

| Apical prolapse, No. (%) | 5 (6) | 9 (17) | .07 (Fisher’s exact test) |

| Posterior prolapse, No. (%) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.9) | >.9 (Fisher’s exact test) |

| Prolapse stage, median (IQR)a | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 2) | .06 (Mann-Whitney U-test) |

| Prolapse stage, median (IQR)b | 2 (1.5, 2.5) | 2 (2, 3) | .06 (Mann-Whitney U-test) |

| Fecal incontinence, No. (%) | 10 (12) | 3 (5.7) | .3 (Fisher’s exact test) |

| Sexually active, No. (%) | 33 (41) | 19 (37) | .7 (Fisher’s exact test) |

| Dyspareunia, No. (%) | 15 (45) | 4 (21) | .2 (Fisher’s exact test) |

| Cancer, No. (%) | 24 (28) | 19 (36) | .4 (Fisher’s exact test) |

| Hysterectomy, No. (%) | 42 (50) | 29 (56) | .6 (Fisher’s exact test) |

| Oophorectomy (any), No. (%) | 19 (23) | 15 (31) | .4 (Fisher’s exact test) |

| Incontinence procedure, No. (%) | 22 (25) | 14 (27) | >.9 (Fisher’s exact test) |

| Mesh complication, No. (%) | 4 (4.8) | 3 (5.7) | >.9 (Fisher’s exact test) |

| Anatomical abnormality, No. (%) | 5 (6) | 0 (0) | .16 (Fisher’s exact test) |

Abbreviations: CC, cystitis cystica; IQR, interquartile range; PVR, post-void residual; UTI, urinary tract infection.

P values that are statistically significant (ie, < .05) are bolded.

Including those without prolapse as stage 0.

Omitting those without prolapse.

Association Between CC and Time to UTI Recurrence

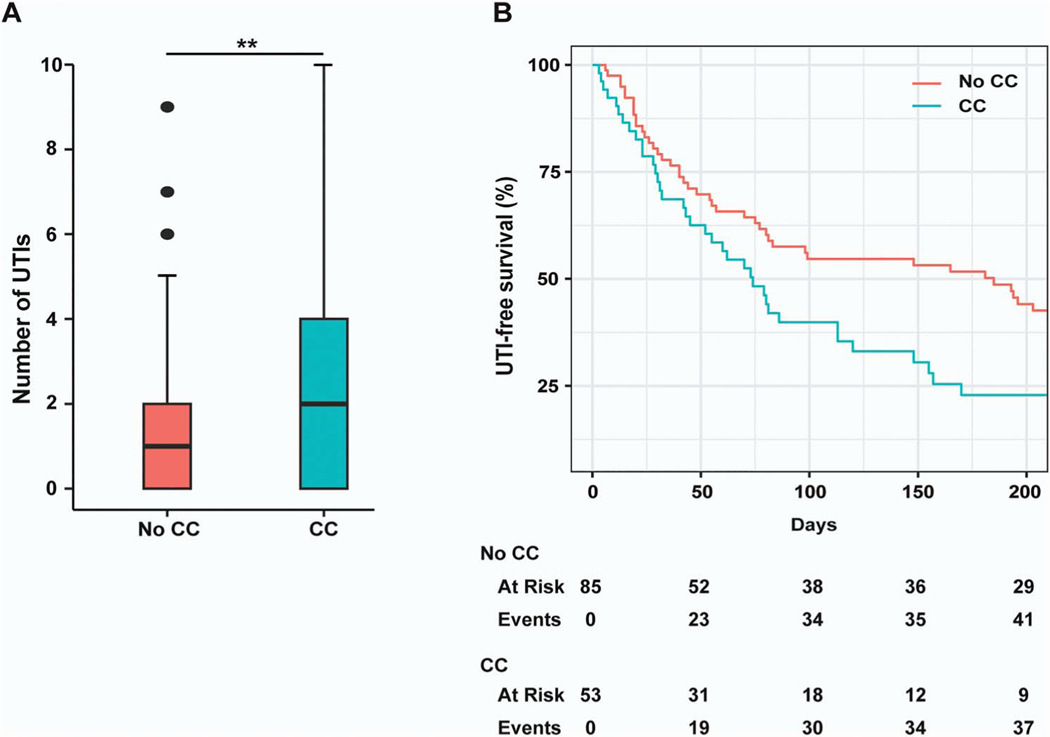

To determine whether patients with and without CC had different clinical outcomes, we examined the time until next culture-positive, symptomatic UTI following initial cystoscopy. Patients with CC had a shorter median UTI-free survival time (74 vs 185 days, P =.03; Figure 1, A). In adjusted analyses, CC (HR 1.54, 95% CI 1.01–2.35) and number of UTIs in the prior year (1.20, 1.07–1.34) were independently predictive of reduced UTI-free survival times. Over the 12-month period following initial cystoscopy, patients with CC had a significantly greater number of culture-positive, symptomatic UTIs (median 1, IQR 0–4) than patients without CC (1, 0–2; P < .01; Figure 1, B).

Figure 1.

Urinary tract infection (UTI)–free survival time and 12-month UTI frequency following initial cystoscopy in recurrent UTI patients with and without cystitis cystica (CC). A, Kaplan-Meier curve of UTI-free survival time after initial cystoscopy in recurrent UTI patients, stratified by presence or absence of CC (P < .03, log-rank test). B, Box and whisker plot shows number of culture positive UTIs in the 12 months following cystoscopy stratified by those with CC vs without CC on cystoscopy. Data were analyzed using Mann-Whitney U Test (**P = .0065). Whisker boundary was defined from 10th-90th percentile. Lines represent the median, and outliers were considered points >1.5 × interquartile range.

Improvement and Resolution of CC Lesions on Repeat Cystoscopy

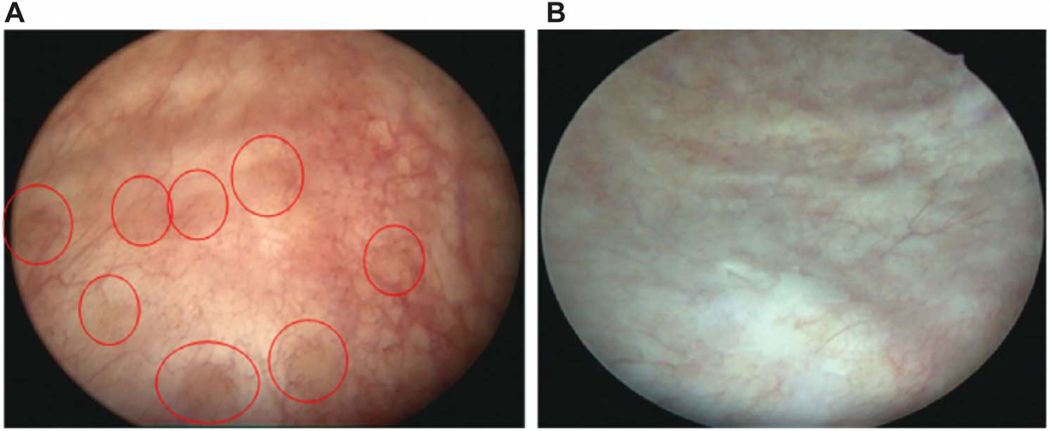

Fifty-one participants with CC had a repeat cystoscopy that showed either no change (18%), improvement (45%), or resolution (38%) of CC lesions (82% either improved or resolved). Example images from an initial and repeat cystoscopy with resolution of lesions is shown in Figure 2. Time between cystoscopies was longest for those with resolved lesions (median 84 days, IQR 28–229), intermediate for those with improved lesions (41, 24–77), and shortest for those with un-changed lesions (27, 20–37; P =.048). Patients treated with ≥7 days of antibiotics for an acute UTI between cystoscopies were more likely to have improved or resolved CC lesions on repeat cystoscopy independent of time between cystoscopies (OR 8.07, 95% CI 1.27–63.1; Table 2).

Figure 2.

Improvement and resolution of cystitis cystica upon repeat cystoscopy. A, Initial cystoscopic view of a postmenopausal repeat urinary tract infection patient showing cystitis cystica lesions (red circles), edema, and hyperemia. B, Repeat cystoscopy of the same patient showing resolution of inflammation and cystitis cystica lesions after using vaginal estrogen, D-mannose, and methenamine hippurate for urinary tract infection prophylaxis.

Table 2.

Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals of Improved or Resolved Cystitis Cystica Lesion Status on Repeat Cystoscopy in Women With Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections

| Change in cystitis cystica status |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Therapies used at time of first cystoscopy | No. | No change or worsened | Improved or resolved |

|

| |||

| Antibiotics | |||

| No | 9 | 55.6% | 44.4% |

| Yes | 42 | 9.5% | 90.5% |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)a | 1.00 | 8.07 (1.27–63.1) | |

| Vaginal estrogen | |||

| No | 16 | 18.8% | 81.3% |

| Yes | 35 | 17.1% | 82.9% |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)a | 1.00 | 1.15 (0.16–6.89) | |

| D-mannose | |||

| No | 37 | 18.9% | 81.1% |

| Yes | 14 | 14.3% | 85.7% |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)a | 1.00 | 1.73 (0.27–19.5) | |

| Methenamine | |||

| No | 42 | 19.1% | 81.0% |

| Yes | 9 | 11.1% | 88.9% |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)a | 1.00 | 2.10 (0.22–106.2) | |

| Cranberry extract | |||

| No | 42 | 21.4% | 78.6% |

| Yes | 8 | 0.0% | 100% |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)a | 1.00 | 4.92 (0.23–106.3) | |

| Vitamin C | |||

| No | 35 | 20.0% | 80.0% |

| Yes | 16 | 12.5% | 87.5% |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)a | 1.00 | 1.95 (0.31–21.8) | |

| Vitamin D | |||

| No | 32 | 21.9% | 78.1% |

| Yes | 19 | 10.5% | 89.5% |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)a | 1.00 | 2.34 (0.38–26.0) | |

| Probiotics | |||

| No | 43 | 20.9% | 79.1% |

| Yes | 8 | 0.0% | 100% |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)a | 1.00 | 5.87 (0.26–131.4) | |

| Multiple therapies | |||

| No | 10 | 40.0% | 60.0% |

| Yes | 41 | 12.2% | 87.8% |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)a | 1.00 | 3.91 (0.59–26.9) | |

| Multiple therapies excluding antibiotics | |||

| No | 24 | 25.0% | 75.0% |

| Yes | 27 | 11.1% | 88.9% |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)a | 1.00 | 3.37 (0.58–25.6) | |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

ORs and 95% CIs were calculated by exact logistic regression and Firth’s penalized likelihood regression.

Adjusted for time between cystoscopies as 1 continuous term.

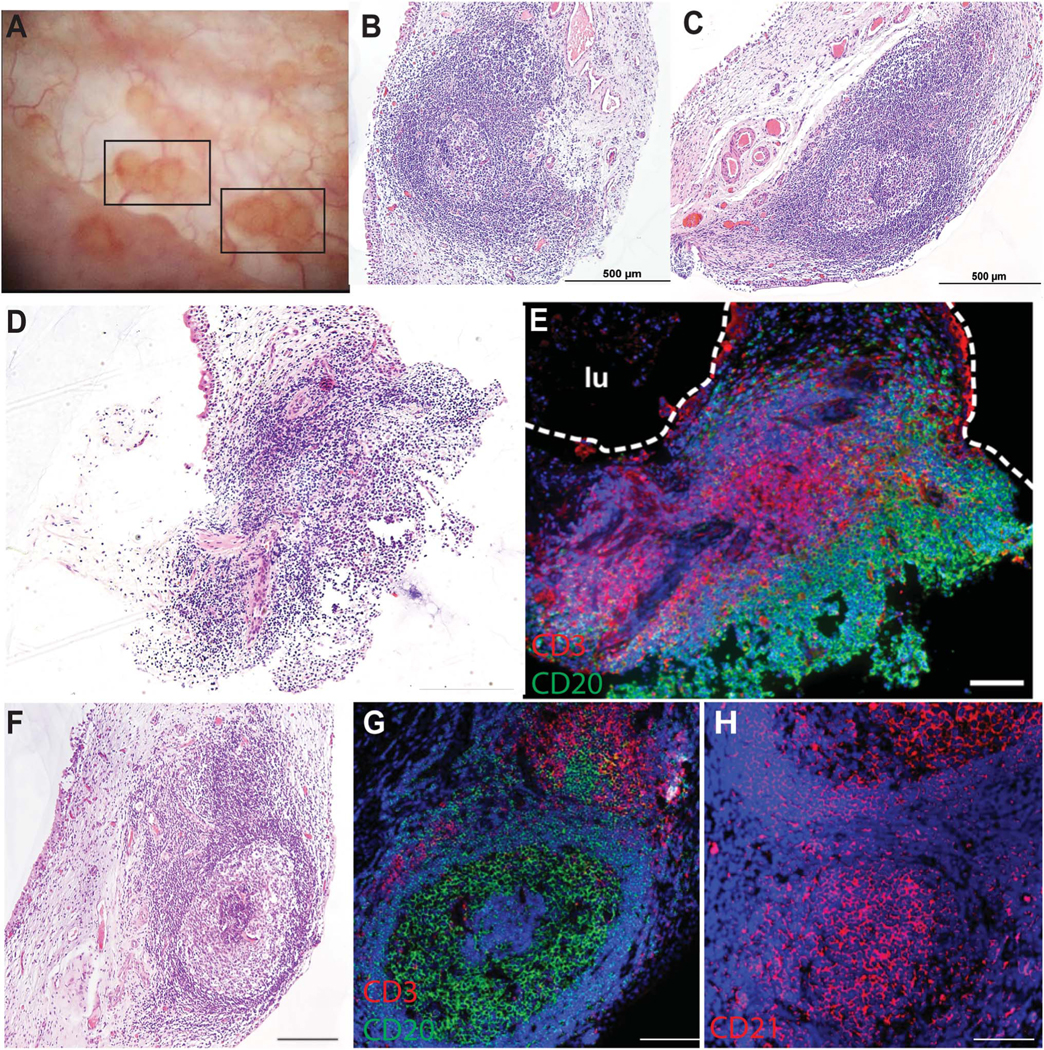

Histopathology of CC Biopsies

To characterize the immunological and pathological changes to the bladder that occur with CC, we obtained biopsies of CC lesions from 11 women (clinical characteristics presented in Table 3). One biopsy had insufficient tissue for a formal pathology report. Pathology reports for 10 biopsies (91%) reported chronic inflammation with no malignant changes. Five of the 10 (50%) biopsies contained distinct lymphoid follicles in the lamina propria diagnosis of FC on pathology report (Figure 3, A–D and F). Analysis of the separate biopsies simultaneously collected for research from 10/11 patients (91%) demonstrated B and T cell zones with follicular dendritic cell networks organized into lymphoid follicles with distinct germinal centers suggesting tertiary lymphoid tissue (TLT; Figure 3, E and G–H).

Table 3.

Patient Characteristics of Cystitis Cystica Biopsies

| Age, y | Menopause | UTIsa | Organism(s) | Cystoscopy description | Pathology description | Follicles on IF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 76 | Post | 2 | Escherichi coli | Cystitis cystica | None | Yes |

| 78 | Post | 4 | E. coli, Enterococcus, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus | Cobblestone appearance | Follicular cystitis | Yes |

| 65 | Post | 2 | Klebsiella | Cystic lesions | Follicular cystitis | Yes |

| 70 | Post | 2 | E. coli | Raised lesions | Acute and chronic inflammation | Yes |

| 70 | Post | 5 | Klebsiella, E. coli | Cobblestone appearance | Acute and chronic inflammation | Yes |

| 63 | Post | 6 | E. coli (ESBL) | Broad-based raised lesions | Chronic cystitis | Yes |

| 47 | Peri | 2 | Corynebacterium/diptheroids | Cystitis cystica | Chronic inflammation and reactive changes | No |

| 69 | Post | 3 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella | Plaque-like raised lesions | Acute and chronic inflammation | Yes |

| 60 | Post | 5 | Klebsiella, E. coli | Diffuse cystic raised, yellowish lesions and cystitis cystica | Follicular cystitis | Yes |

| 87 | Post | 4 | E. coli, Klebsiella, Citrobacter | Cystic yellow blebs with cystic and solid appearance | Cystitis cystica, cystitis glandularis, and follicular cystitis | Yes |

| 75 | Post | 3 | Klebsiella, E. coli, Citrobacter | Follicular cystitis | Follicular cystitis; acute and chronic inflammation with granulation tissue | Yes |

Abbreviations: ESBL, extended spectrum beta-lactamase; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Number of UTIs in the 12 months preceding initial cystoscopy.

Figure 3.

Cystitis cystica lesion biopsies are tertiary lymphoid tissue with germinal centers. A, Representative cystoscopic view of cystitis cystica lesions, denoted by black rectangles. B and C, Representative hematoxylin & eosin images of lymphoid tissues with germinal center in cystitis cystica biopsies. Scale bar, 500 μm. D and E, Hematoxylin & eosin image of cystitis cystica biopsy and corresponding immunofluorescent staining showing B cells (CD20, green) and T cells (CD3, red) within lymphoid follicle. Bladder lumenal (lu) space is outlined in white. Nuclei are stained blue with Hoechst. Scale, 200 μm. F, Hematoxylin & eosin image of cystitis cystica biopsy with germinal center within the lymphoid follicle. G and H, corresponding immunofluorescence staining of B cells (CD20, green) and T cells (CD3, red; G) and follicular dendritic cell network (CD21, red; H). Hoescht, blue. Scale, 200 μm.

DISCUSSION

CC has been generally regarded as a benign, insignificant, and nonspecific finding of chronic inflammation, and its prevalence, pathogenesis, and impact on UTIs have not been well described. We report an analysis of the frequency of CC in rUTI patients who underwent cystoscopy, and clinical and histological factors associated with this finding. We found that postmenopausal status, number of UTIs in the prior year, and PFMP were highly associated with finding CC on cystoscopy. Patients with CC were more likely to have a greater number of UTIs in the year following cystoscopy and a shorter time to their next UTI. We also observed that resolution of CC lesions typically occurs after approximately 3 months and was related to antibiotic use.

Our findings suggesting that the presence of CC is detrimental for rUTIs in postmenopausal women is supported in part by Vrljicak9 and Milosevic10 and colleagues, who determined a potential positive feedback loop with rUTIs and number of bladder wall nodules or CC in prepubertal females. They noted a correlation between the number of CC lesions observed on cystoscopy with number of UTIs in the prior year and bladder wall thickness and regression of the CC with improved rUTI incidence. Moreover, Koti et al have recently demonstrated that the presence of well-formed TLT-/CC-like structures was associated with bladder tumor stage.11 Extrapolating from these preclinical and clinical studies, the discovery and cellular composition of TLTs in prepubertal girls and in postmenopausal women warrant further research into their role as predictive biomarkers for rUTIs, bladder cancer progression, and other conditions.

Given the studies in prepubertal girls, our finding that CC and postmenopausal status are associated, and the known protective effects of estrogen in the bladder, forming CC lesions is likely influenced by estrogen or other sex hormones. TLT formation appears to be a sex-specific phenomenon as they occur in female and not in male mice.12,13 Recent work from our group shows that vaginal estrogen therapy in old female mice appears to promote regression of these CC/TLT lesions in part by reducing levels of TLT-promoting chemokines.14 Our study in postmenopausal women showed that antibiotics were associated with relatively rapid CC resolution. This is consistent with findings from De Nisco et al showing presence of TLTs associated with diverse bacterial species in bladder biopsy samples from postmenopausal women with rUTIs undergoing cystoscopy,15 and from Crivelli et al16 and Ordonez et al17 showing electrofulguration by cauterization of CC/TLT led to improved outcomes in women with antibiotic-refractory rUTIs.

In another retrospective cohort study of patients with rUTIs whose CC status was identified by cystoscopy and who were treated with D-mannose, patients with CC had a higher UTI incidence rate than patients without CC. Initiation of D-mannose prophylaxis led to a significant decrease in UTI incidence rate in patients with CC.18 Thus, the use of cystoscopy to assess for CC and developing therapies targeted at reducing the formation or maturation of CC lesions may be beneficial for improving women’s lower urinary tract health.

Our histological studies demonstrate that CC lesions contain TLTs that are better described in pathological terms as FC. Indeed, our histological findings are inconsistent with a pathological diagnosis of cystitis cystica, which consists of proliferation of invagination urothelium (von Brunn’s nests) forming cysts within the bladder wall. We posit that what appears as typical CC lesions on cystoscopy is frequently consistent with a pathological diagnosis of FC.

TLTs are organized lymphoid tissues that arise in nonlymphoid organs and are capable of generating local, adaptive immune responses and associated with chronic inflammation in response to infection, autoimmune disease, cancer, or other persistent stimuli.19–24 TLTs have been associated with both protective and pathogenic responses to different chronic infections. For example, TLTs in the lung are associated with protection against reactivation of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis.25–27 In contrast, TLTs associated with chronic hepatitis C virus infection result in greater inflammatory liver pathology and autoimmune complications.28 In chronic Helicobacter pylori gastroenteritis, TLTs have the potential to become mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas.29 Interestingly, these gastric TLTs, both benign and malignant, frequently regress after eradication of H. pylori with antibiotics, akin to resolution of CC that we observed with antibiotic and rUTI prophylaxis treatments. Given that patients with CC had a shorter time to their next UTI and a greater number of UTIs in the following year, TLTs likely play a pathogenic role in the bladder, generating ineffective immune responses that promote further inflammation rather than resolution of rUTIs. A histopathological diagnosis of CC/FC could be an indicator of rUTI risk and vice versa.

The strengths of this paper include a well-characterized clinical cohort of women with culture-proven rUTIs, cystoscopically confirmed CC, and associated biospecimens that formed the basis of this study. In addition, women underwent repeat cystoscopy by the same FPMRS (Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery) attending physician that performed the baseline cystoscopy allowed confirmation of CC status post-intervention. Limitations of this study include the overall small sample size of women who underwent repeat cystoscopy to power significant associations between postmenopausal status and UTI incidence. There is also not a validated method to cystoscopically assess severity of CC. Developing a validated severity scale would improve CC lesion monitoring over time. Extending the time frame of treatments such as D-mannose and performing repeat cystoscopy at defined intervals could provide more accurate information on impact on CC lesions. Finally, consensus of terminology between surgeons and pathologists would greatly benefit the field as CC and FC are often used interchangeably in clinical papers. We suggest that CC (as seen by cystoscopy) may frequently be a misnomer and would more accurately be described as FC.

CONCLUSIONS

We found that CC in women with rUTIs is associated with postmenopausal status, PFMP, a higher number of prior UTIs, and shorter UTI-free survival time after cystoscopy. CC lesions are composed of TLT with germinal centers, more appropriately termed FC, and can resolve over time with therapy including ≥7 days of antibiotic treatment. We suggest that CC/FC is a specific inflammatory change that promotes further susceptibility to UTIs and may be modified by targeted therapies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Zoe Jennings and Women’s Genitourinary Tract Specimen Consortium (WGUTSC) for consenting patients and collecting and cataloging samples. We also thank Jessica Sawhill and Dr Melanie Meister for collecting biopsies.

Support:

This work was funded in part by NIH Grants R01AG052494, R56AG064634, and P20DK119840 (I.U.M.); T32 GM007200, T32AI007172, and Washington University Institute for Clinical and Translation Sciences Grant JIT655 (M.M.L.); NIH CTSA Grant UL1TR002345 and a Washington University Institute for Clinical and Translation Sciences Grant (J.L.L.); and NIH Grant P30CA91842.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: I.U.M.: Scientific advisory board: Luca Biologics. The remaining Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethics Statement: This study received Institutional Review Board approval (IRB No. 20190534).

REFERENCES

- 1.Foxman B, Barlow R, D’Arcy H, Gillespie B, Sobel JD. Urinary tract infection: self-reported incidence and associated costs. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10(8):509–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ikahelmo R, Siitonen A, Heiskanen T, et al. Recurrence of urinary tract infection in a primary care setting: analysis of a I-year follow-up of 179 women. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22(1):91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brubaker L, Carberry C, Nardos R, Carter-Brooks C, Lowder JL. American Urogynecologic Society best-practice statement: recurrent urinary tract infection in adult women. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2018;24(5):321–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Brien VP, Hannan TJ, Yu L, et al. A mucosal imprint left by prior Escherichia coli bladder infection sensitizes to recurrent disease. Nat Microbiol. 2016;2(1):16196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fulop T, Larbi A, Dupuis G, et al. Immunosenescence and inflamm-aging as two sides of the same coin friends or foes?. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meister MR, Wang C, Lowder JL, Mysorekar IU. Vaginal estrogen therapy is associated with decreased inflammatory response in postmenopausal women with recurrent urinary tract infections. Female Pelvic Med Reconstruct Surg. 2021;27(1):e39–e44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walters MD, Karram MM. Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery, 4th ed. Elsevier/Saunders; 2015:674. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou M, Magi-Galluzzi C. Genitourinary Pathology: Foundations in Diagnostic Pathology, 2nd ed. Elsevier/Saunders; 2015:705. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vrljicak K, Turudíc D, Bambir I, et al. Positive feedback loop for cystitis cystica: the effect of recurrent urinary tract infection on the number of bladder wall mucosa nodules. Acta Clin Croat. 2013;52(4):444–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milosevic D, Trkulja V, Turudic D, Batinic D, Spajic B, Tesovic G. Ultrasound bladder wall thickness measurement in diagnosis of recurrent urinary tract infections and cystitis cystica in prepubertal girls. J Pediatr Urol. 2013;9(6):1170–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koti M, Xu AS, Ren KYM, et al. Tertiary lymphoid structures associate with tumour stage in urothelial bladder cancer. Bladder Cancer. 2017;3(4):259–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ligon MM, Wang C, DeJong EN, Schulz C, Bowdish DME, Mysorekar IU. Single cell and tissue-transcriptomic analysis of murine bladders reveals age- and TNFα-dependent but microbiota-independent tertiary lymphoid tissue formation. Mucosal Immunol. 2020;13(6):908–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamade A, Li D, Tyryshkin K, et al. Sex differences in the aging murine urinary bladder and influence on the tumor immune microenvironment of a carcinogen-induced model of bladder cancer. Biol Sex Differ. 2022;13(1):19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fashemi BE, Wang C, Chappidi RR, Morsy H, Mysorekar IU. Supraphysiologic vaginal estrogen therapy in aged mice mitigates age-associated bladder inflammatory response to urinary tract infections. Urogynecology. 2022; 10.1097/SPV.0000000000001276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Nisco NJ, Neugent M, Mull J, et al. Direct detection of tissue-resident bacteria and chronic inflammation in the bladder wall of postmenopausal women with recurrent urinary tract infection. J Mol Biol. 2019;431(21):4368–4379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crivelli JJ, Alhalabi F, Zimmern PE. Electrofulguration in the advanced management of antibiotic-refractory recurrent urinary tract infections in women. Int J Urol. 2019;26(6):662–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ordonez J, Christie AL, Zimmern PE. Role of flexible cystoscopy in the management of postmenopausal women with recurrent urinary tract infections. Urology. 2022;169:65–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiu K, Zhang F, Sutcliffe S, Mysorekar IU, Lowder JL. Recurrent urinary tract infection incidence rates decrease in women with cystitis cystica after treatment with d-mannose: a cohort study. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2022;28(3):e62–e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rangel-Moreno J, Hartson L, Navarro C, Gaxiola M, Selman M, Randall TD. Inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) in patients with pulmonary complications of rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(12):3183–3194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knoop KA, Newberry RD. Isolated lymphoid follicles are dynamic reservoirs for the induction of intestinal IgA. Front Immunol. 2012;3:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eddens T, Elsegeiny W, Garcia-Hernadez MD, et al. Pneumocystis-driven inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue formation requires Th2 and Th17 immunity. Cel Rep. 2820;18(13):3078–3090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lucchesi D, Bombardieri M. The role of viruses in autoreactive B cell activation within tertiary lymphoid structures in autoimmune diseases. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94(6):1191–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neyt K, Perros F, GeurtsvanKessel CH, Hammad H, Lambrecht BN. Tertiary lymphoid organs in infection and autoimmunity. Trends Immunol. 2012;33(6):297–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pitzalis C, Jones GW, Bombardieri M, Jones SA. Ectopic lymphoid-like structures in infection, cancer and autoimmunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(7):447–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khader SA, Guglani L, Rangel-Moreno J, et al. IL-23 is required for long-term control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and B cell follicle formation in the infected lung. J Immunol. 2011;15187(10):5402–5407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khader SA, Rangel-Moreno J, Fountain JJ, et al. In a murine tuberculosis model, the absence of homeostatic chemokines delays granuloma formation and protective immunity. J Immunol. 2009;183(12):8004–8014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ulrichs T, Kosmiadi GA, Trusov V, et al. Human tuberculous granulomas induce peripheral lymphoid follicle-like structures to orchestrate local host defence in the lung. J Pathol. 2004;204(2):217–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sansonno D, Tucci FA, Troiani L, et al. Increased serum levels of the chemokine CXCL13 and up-regulation of its gene expression are distinctive features of HCV-related cryoglobulinemia and correlate with active cutaneous vasculitis. Blood. 2008;112(5):1620–1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kobayashi M, Mitoma J, Nakamura N, Katsuyama T, Nakayama J, Fukuda M. Induction of peripheral lymph node addressin in human gastric mucosa infected by Helicobacter pylori. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(51):17807–17812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]