Abstract

Virulent and avirulent strains of swine vesicular disease virus (SVDV), a picornavirus, have been characterized previously. The major determinants for attenuation have been mapped to specific residues in the 1D-2A-coding region. The properties of the 2A proteases from the virulent and avirulent strains of SVDV have now been examined. Both proteases efficiently cleaved the 1D/2A junction in vitro and in vivo. However, the 2A protease of the avirulent strain of SVDV was much less effective than the virulent-virus 2A protease at inducing cleavage of translation initiation factor eIF4GI within transfected cells. Hence the virulent-virus 2A protease is much more effective at inhibiting cap-dependent protein synthesis. Furthermore, the virulent-virus 2A protease strongly stimulated the internal ribosome entry sites (IRESs) from coxsackievirus B4 and from SVDV, while the avirulent-virus 2A protease was significantly less active in these assays. Thus, the different properties of the 2A proteases from the virulent and avirulent strains of SVDV in regulating protein synthesis initiation reflect the distinct pathogenic properties of the viruses from which they are derived. A single amino acid substitution, adjacent to His21 of the catalytic triad, is sufficient to confer the characteristics of the virulent-strain 2A protease on the avirulent-strain protease. It is concluded that the efficiency of picornavirus protein synthesis, controlled directly by the IRES or indirectly by the 2A protease, can determine virus virulence.

Swine vesicular disease virus (SVDV), like Poliovirus (PV), is a member of the Enterovirus genus of the family Picornaviridae. SVDV is related both antigenically (11) and genetically to the human enterovirus coxsackievirus B5 (CB5) (14, 39). Virulent strains of SVDV induce the formation of vesicles in pigs that are clinically indistinguishable from those induced by another picornavirus, foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV), an aphthovirus. In addition, avirulent strains of SVDV have been isolated from apparently healthy pigs (21). The virulent and avirulent strains grow to similarly high titers in tissue culture cells (19). However, the virulent viruses display a large-plaque phenotype, while the avirulent viruses only produce small plaques.

Full-length infectious cDNA clones corresponding to both the virulent J1′73 strain (termed J1) and the avirulent H/3′76 strain (termed 00) of SVDV have been isolated (15, 18). The viruses recovered from these plasmids retain the biological characteristics of their parental viruses (18). The complete nucleotide sequences (7,401 nucleotides [nt]) of both strains of virus have been determined (14, 16). Furthermore, recombinant viruses have been rescued from chimeric cDNAs containing regions derived from the virulent and avirulent viruses. Hence, it is possible to map key determinants of virulence. The critical region of the genome (between nt 2233 and 3368) encodes the C terminus of 1C, the whole of 1D, and the N terminus of 2A (19). There are eight amino acid substitutions between the virulent J1 strain and the avirulent 00 strain within this region. Site-directed mutagenesis has shown that just two substitutions, at residue 132 within 1D (VP1) and residue 20 within the 2A protease, each have a major effect on plaque size in tissue culture. When tested together these two mutations alone were sufficient to confer the high-virulence phenotype in pigs on the avirulent virus (19). Furthermore, just the modification of residue 20 within the 2A protease conferred a small-plaque phenotype on the previously large-plaque-phenotype J1 strain.

The 2A protease of enteroviruses has several different biochemical activities. It is responsible for cleavage at the 1D/2A junction, the primary cleavage event in the enterovirus polyprotein (36). Furthermore the 2A protease is required for the cleavage of translation initiation factor eIF4G (22). Cleavage of eIF4G results in the inhibition of cellular cap-dependent protein synthesis. The recognition of capped mRNAs by the cellular translation machinery requires interaction of the 5′ terminal cap structure (m7GpppN) with the cap-binding complex eIF4F. This initiation factor comprises eIF4E (which binds to the cap), eIF4A (an RNA helicase), and eIF4G, which acts as a scaffold to bridge between the mRNA and the ribosome (9). There is some controversy concerning whether the cleavage of eIF4G induced by the 2A protease occurs directly in cells or is mediated by a cellular protease (reviewed in reference 2). Efficient cleavage of eIF4GI occurs at very low levels of virus protein expression (e.g., when virus replication is blocked [10]). The third known activity of the 2A protease is the stimulation of picornavirus internal ribosome entry site (IRES) activity (5, 13, 30). This process also only requires a low level of protease expression. The relationship between IRES activation and eIF4G cleavage is not firmly established (2); our own studies suggest that these processes are distinct (30).

The enterovirus 2A proteases are believed to be structurally similar to trypsin-like serine proteases (1, 33), and a catalytic triad has been identified in the PV 2A protease comprising His20, Asp38, and Cys109 (38) (note that the cysteine residue is the active-site nucleophile rather than a serine residue as in the serine proteases). As expected the catalytic triad is conserved in the SVDV 2A protease, and the catalytic triad thus comprises His21, Asp39, and Cys110. One of the key determinants of attenuation in SVDV, residue 20 of the 2A protease, which is Arg20 in the virulent J1 strain but Ile20 in the avirulent 00 strain, is adjacent to residue His21 in the catalytic triad. It seemed possible that residue 20 may affect substrate recognition by the protease. We therefore sought to analyze the properties of the 2A proteases from the two different strains of SVDV to determine whether differences in the known biochemical functions of 2A could explain the differences in virulence of the viruses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

All DNA manipulations were performed using standard methods (34). Fragments (1.3 kbp) corresponding to the 1D-2A-coding regions of the J1 and 00 strains of SVDV were generated in separate PCRs using Taq polymerase. The primers used were 1D-exp F (dCCGAATTCACCATGGAAC AAAAACTCATCTCAGAAGAGGATCTGGGGCCCCCAGGAGAGGTG; 62-mer) and 2A-exp R (dCCGGATCCTTATTGCTCCATGGCATCGTCCTCC; 33-mer). The full-length infectious cDNA plasmid for the 00 strain (15) and cDNA generated by reverse transcription of the virulent J1 viral RNA, with 2A-exp R as the primer, were used as templates. The fragments were ligated into vector pGEM-T (Promega) and introduced into Escherichia coli (strain JM109). Plasmid DNA, amplified from single colonies, was screened by digestion with EcoRI and BamHI (these enzyme sites [italics] were introduced by the PCR primers). The 1.3-kbp fragments obtained were ligated to similarly digested pGEM3Z (Promega) to generate pGEM3Z/00 and pGEM3Z/J1, respectively (Fig. 1). The expression of the c-myc-tagged 1D-2A is under the control of the T7 promoter.

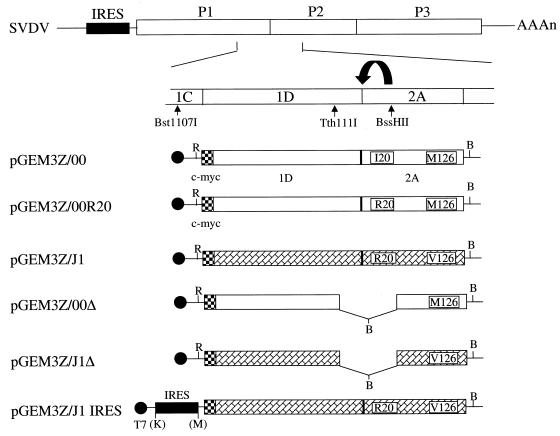

FIG. 1.

Structure of the SVDV cDNA plasmids used in this study. The region of the SVDV genome that contains the determinants of virulence is included within a Bst1107I-BssHII restriction enzyme cDNA fragment including the coding sequence for the whole of 1D and the N-terminal region of the 2A protease. Regions of the genome from the pathogenic J1 strain (hatched bars) and the attenuated 00 strain (open bars) were amplified by PCR and cloned as EcoRI (R)-BamHI (B) fragments into the vector pGEM3Z under the control of a T7 promoter (●). The SVDV IRES (solid bar) was within a KpnI (K)-MscI (M) fragment. The c-myc epitope tag (checkered bars) was attached to the N terminus of 1D. The amino acid differences (residues 20 and 126) within the 2A protease between the J1 and 00 strains of SVDV are shown. The 1D coding sequence of the 00 strain plasmid had two amino acid substitutions compared to the published sequence (C to Y, residue 69, and Y to C, residue 219) while the J1 strain 1D sequence had a single amino acid substitution (K to E, residue 266). These mutations were different for different isolates of the same plasmids (A to C) and hence were probably generated in the PCR.

An in-frame deletion within the 1D-2A-coding region was introduced by digestion of pGEM3Z/00 and pGEM3Z/J1 with Tth111I and BssHII (Fig. 1). The large fragments generated were gel purified, blunt ended (using the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I), treated with phosphatase, and ligated to phosphorylated BamHI linkers (9-mers; NEB). Following transformation of E. coli (JM109), plasmid DNA was isolated from amplified single colonies, screened for the presence of the new BamHI site, and sequenced. Plasmids pGEM3Z/00Δ and pGEM3Z/J1Δ had the expected structure and encoded a truncated 1D-2A (termed 1DΔ-2AΔ) lacking 53 amino acids (Fig. 1) of the original sequence but with the addition of extra amino acids encoded by the linker. Plasmid pGEM3Z/00Δ contained two tandem copies of the linker, which added six amino acids, whereas plasmid pGEM3Z/J1Δ contained a single linker adding just three amino acids.

The SVDV cDNA fragment from the 5′ noncoding region containing the predicted IRES sequence within a KpnI-MscI fragment (567 bp) was isolated from a plasmid containing the J1 cDNA. The fragment was blunt ended (using T4 DNA polymerase) and ligated into pGEM3Z/J1, which was digested with EcoRI, blunt ended (using the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I), and treated with phosphatase, to create pGEM3Z/J1 IRES (Fig. 1). The same IRES cDNA fragment and the corresponding sequence from the 00 cDNA was also inserted into pGEM-CAT/LUC dicistronic reporter plasmid (30), which had been blunt ended, cut with BamHI, filled in, and treated with phosphatase to create plasmids pGEM-CAT/SVDJ(+)/LUC, pGEM-CAT/SVDJ(-)/LUC, and pGEM-CAT/SVD00(+)/LUC containing the SVDV IRES cDNA (J1 or 00 strain) in the sense (+) and antisense (−) orientations, respectively.

Modification of the codon encoding Ile20 in the 2A protease of the 00 1D-2A to encode Arg (R) at this position was performed by PCR mutagenesis. Two PCRs were performed with plasmid pGEM3Z/00 as the template and Pfu DNA polymerase using primers 1Dfor (dCCGAATTCACCATGGAACAAAAAC) with 2Amutrev (dGTTGCGAGATGTCTATTCACCACTCTATAG) and with primers 2Amutfor (dAGTGGTGAATAGACATCTCGCAACGCG) and 2Arev (dCCGGATCCTTATTGCTCCATG). The products of about 900 and 400 bp, respectively, were gel purified, mixed, and used as the template for a single PCR with primers 1Dfor and 2Arev (as above). A fragment of 1.3 kbp was digested with EcoRI and BamHI and ligated into similarly digested pGEM3Z to create pGEM3Z/00R20. The presence of the expected mutation in the 00 cDNA background was verified by sequencing.

Expression assays.

In vitro transcription-translation (TNT) reactions were performed using the Promega TNT T7 kit essentially as described by the manufacturer. Aliquots (5 μl) of the reaction mixtures were removed at 30 and 120 min, mixed with sample buffer containing sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and dithiothreitol, boiled, and analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (23) and autoradiography.

Transient expression assays within cells infected with the recombinant vaccinia virus vTF7-3, which expresses the T7 RNA polymerase (8), were performed as described previously (30). Briefly, BHK cells were infected with vTF7-3 and transfected using Lipofectin (8 μg; Life Technologies) with plasmid DNA (2.5 μg) or cotransfected with 2 μg of reporter plasmid plus 0.5 μg of the 2A-encoding plasmids. Dicistronic reporter plasmid pGEM-CAT/CB4/LUC, which expresses a dicistronic mRNA encoding chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) and luciferase (LUC), has been described previously (30). Translation of the LUC sequence is dependent on the CB4 IRES. The construction of the analogous plasmids containing the SVDV IRES cDNA is described above. Plasmid pAΔ802, which expresses the PV 2A protease, has also been described (17). After 20 h, cell extracts were prepared and analyzed by SDS-PAGE (23), followed by Western blotting using antibodies specific for the c-myc epitope (monoclonal antibody 9E10; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.), eIF4GI (C terminus [W. Li, N. Ross-Smith, C. G. Proud, and G. J. Belsham, submitted for publication]), CAT (5prime-3prime Inc.), and LUC (Promega). Detection was achieved using peroxidase-labeled antispecies antibodies (Amersham) and chemiluminescence reagents (Pierce). LUC expression was also monitored using a luciferase assay kit (Promega) and a luminometer (Bio-orbit).

RESULTS

To compare the properties of the SVDV 2A proteases from the virulent (J1) and attenuated (00) strains of SVDV, a short region of the genome encoding the 1D-2A proteins was amplified from cDNA corresponding to the viral genomes. PCR primers 1D-exp F and 2A-exp R (see Materials and Methods) specify unique restriction enzyme sites, an initiation codon, a c-myc epitope tag (for detection), and a termination codon. These primers were used to obtain a single cDNA fragment from both the J1 and 00 reactions. Three independent plasmids containing the 1.3-kbp EcoRI-BamHI fragment from each cDNA were isolated and termed pGEM3Z/J1A, -B and -C and pGEM3Z/00A, -B, and -C, respectively. In each case, the expression of the cDNA was under the control of the T7 promoter. The assays described below were performed, in preliminary experiments, on each of the three isolates of both the J1 and 00 cDNAs, and similar behaviors were observed with all three plasmids. All the data presented are derived from a single isolate (C) of each plasmid. The complete nucleotide sequence of each insert was determined. Point mutations in the 1D coding sequence, compared to the previously published sequences, were observed (Fig. 1), but each of the 2A-coding sequences was identical to those described previously for these strains (14, 16).

In vitro analysis of SVDV 1D-2A expression and activity.

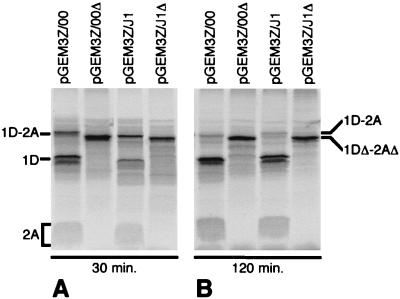

As an initial screen for the properties of the 2A proteases, the plasmids encoding the myc-tagged 1D-2A (Fig. 1) were assayed with in vitro coupled TNT reactions. Aliquots of the reaction mixtures were removed at 30 and 120 min and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography (Fig. 2). At 30 min, the major species detected was the uncleaved precursor 1D-2A but some cleavage had taken place to generate the mature 1D and 2A species. By 120 min, these two products were the predominant species in the reactions. A similar profile of proteins was present when plasmids encoding the J1 and 00 cDNAs were used, and the apparent kinetics of cleavage at the 1D/2A junction were indistinguishable. This efficient cleavage of the 1D/2A junction by both 1D-2A proteins was expected since both sequences were derived from viruses that replicate with similar efficiencies in tissue culture (19). It is clearly essential that efficient cleavage at the 1D/2A junction occurs to allow correct formation of the capsid precursor.

FIG. 2.

In vitro analysis of SVDV 1D-2A expression and self-cleavage activity. The indicated plasmids were used to program in vitro TNT reactions. Samples from the reactions, taken at 30 and 120 min as indicated, were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Uncleaved precursor 1D-2A and mature products 1D and 2A are identified, as is the uncleaved truncated product 1DΔ-2AΔ, generated by the deletion mutant lacking the 1D/2A cleavage site (Fig. 1).

An in-frame deletion was introduced into the 1D-2A constructs (Fig. 1, plasmids pGEM3Z/J1Δ and pGEM3Z/00Δ) to remove the 1D-2A cleavage site and inactivate the protease (29 residues of 1D and 24 residues of the 2A protease were deleted, including one component of the catalytic triad). These plasmids produced a single 44-kDa species (1DΔ-2AΔ), which was not processed during the incubation period as expected (Fig. 2).

Analysis of SVDV 2A activities within cells.

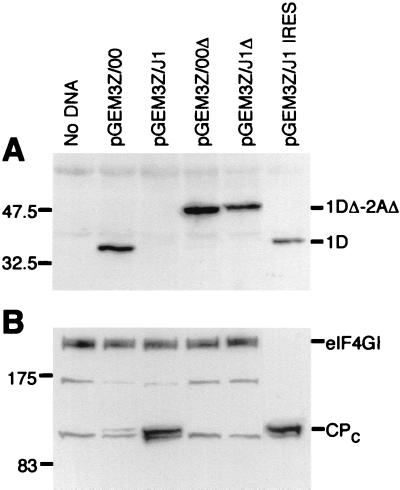

Further assays of the properties of the 2A proteases were performed using the vaccinia virus/T7 RNA polymerase transient expression system (8). Direct analysis of the expression of the 1D-2A proteins was performed using Western blot analysis with a monoclonal antibody (9E10) directed against the c-myc epitope introduced at the N terminus of the 1D protein (Fig. 1). Expression of a 34-kDa species was readily detected from cells transfected with plasmid pGEM3Z/00 (Fig. 3A). This protein is of the expected size for the mature myc-tagged 1D protein, indicating that complete cleavage at the 1D/2A junction had occurred. In contrast, little or no myc-tagged protein was detected in extracts of cells transfected with plasmid pGEM3Z/J1 (Fig. 3A). It is apparent that the pattern of products detected within cells is significantly different from that detected using the same plasmids within the in vitro translation system (Fig. 2). The efficiency of cleavage at the 1D/2A junction is clearly very high in cells, and translational control is more stringent within cells (see below).

FIG. 3.

The SVDV 2A protease from strain J1, but not that from strain 00, induces efficient eIF4GI cleavage and inhibits its own synthesis in BHK cells. The indicated plasmids were transfected into vTF7-3-infected BHK cells. After 20 h, cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using antibodies specific for the c-myc epitope tag on the N terminus of 1D (A) and for the C terminus of eIF4GI (B). CPC, C-terminal cleavage product of eIF4GI. Note that the product of about 175 kDa that reacts with the anti-eIF4GI antisera is characteristic of BHK cell extracts (see also reference 31); it is lost following eIF4GI cleavage and may be a breakdown product of eIF4GI.

Transfection of cells with plasmids pGEM3Z/J1Δ and pGEM3Z/00Δ resulted in the efficient expression of a 44-kDa protein corresponding to the uncleaved 1DΔ-2AΔ species in each case (Fig. 3A), as observed in vitro (Fig. 2). Note that this truncated protein is larger than the product detected from the unmodified 00 1D-2A construct, which confirmed that the species detected from the parental plasmid was the fully processed c-myc tagged 1D protein (34 kDa).

Since it was expected that the 2A proteases would induce cleavage of eIF4GI, the state of this protein in these same extracts was analyzed by Western blotting (Fig. 3B). It was apparent that eIF4GI was very efficiently cleaved in cells transfected with plasmid pGEM3Z/J1, but, in contrast, only low-level cleavage of eIF4GI was apparent in cells that received plasmid pGEM3Z/00. The efficiency of cleavage should be judged by the appearance of cleavage products, not the loss of full-length eIF4GI, since not all cells will be transfected. These results indicated that the lack of detection of the J1 strain 1D-2A product in Fig. 3A did not result from poor transfection but probably reflected the shutoff of cap-dependent protein synthesis resulting from the cleavage of eIF4GI (see below). As anticipated, the uncleaved and catalytically inactive J1 1DΔ-2AΔ did not induce eIF4GI cleavage (Fig. 3B).

In summary, these results indicated that the 1D-2A product from the attenuated strain (00) of SVDV was expressed at a much higher level than the J1 1D-2A product. However, this high level of 00 strain 2A protease was much less efficient at inducing the cleavage of eIF4GI than the low level of J1 2A protease. Clearly, a 2A protease that actively shuts off cap-dependent protein synthesis will block its own synthesis when it is translated by a cap-dependent mechanism. However, it was anticipated that insertion of the SVDV IRES upstream of the 1D-2A-coding region should result in the expression of the J1 1D-2A despite the cleavage of eIF4GI. Hence, plasmid pGEM3Z/J1 IRES containing the SVDV IRES was constructed (Fig. 1) and assayed within cells as described above. Efficient expression of the mature J1 strain myc-tagged 1D protein was now detected (Fig. 3A) from cell extracts in which eIF4GI was very efficiently cleaved (Fig. 3B). This result showed that the J1 1D-2A protein is fully functional both in cleaving the 1D/2A junction and in inducing eIF4GI cleavage. It should be noted that in the rabbit reticulocyte lysate in vitro translation system (as used in Fig. 2) the synthesis of a protein that induces eIF4GI cleavage had little effect on the translational efficiency of the uncapped transcripts that lack IRES elements (Fig. 2) produced in the TNT system. This result is consistent with previous data (e.g., from Ohlmann et al.[29]) which showed that cleavage of eIF4GI by the FMDV Lb protease did not inhibit the translation of uncapped transcripts in vitro.

IRES activation.

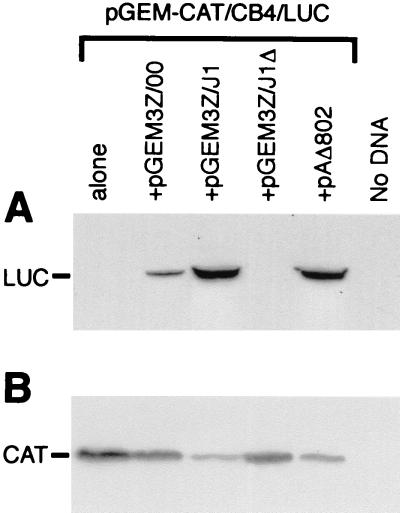

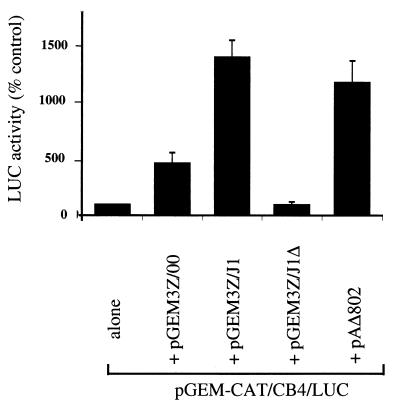

The enterovirus 2A proteases not only induce inhibition of cap-dependent protein synthesis but also stimulate translation directed by enterovirus IRES elements within cells in which these IRES elements function at relatively low efficiency (30). To analyze this activity, the plasmids encoding the SVDV 1D-2A proteins were cotransfected into BHK cells with reporter plasmid pGEM-CAT/CB4/LUC (Fig. 4). This plasmid (30) expresses a dicistronic mRNA encoding CAT (as a reporter for cap-dependent translation) and LUC. Translation of the LUC sequences depends on the activity of the IRES element that, in this construct, is derived from CB4, an enterovirus with strong similarities to SVDV. As a positive control for the activation of the CB4 IRES, a plasmid (pAΔ802) that encodes the PV 2A protease (17) was also assayed, as described previously (30). Transfection of vTF7-3-infected BHK cells with pGEM-CAT/CB4/LUC alone resulted in the efficient expression of CAT as determined by Western blot analysis (Fig. 4B). In BHK cells the CB4 IRES is relatively inactive, and thus little expression of LUC was observed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 4A). However, the more sensitive enzyme assay readily detected the level of LUC expression. (Note that the expression of LUC from the reporter plasmid containing the CB4 IRES is at least 50-fold higher than that from plasmid pGEM-CAT/LUC, which lacks an IRES element [data not shown].) Coexpression of the PV 2A protease (from plasmid pAΔ802) resulted in a strong stimulation (about 12-fold) of LUC expression directed by the CB4 IRES (Fig. 4A and 5). Furthermore, significant inhibition of cap-dependent protein synthesis, as indicated by CAT expression (Fig. 4B), was observed, consistent with previous results (30). Similarly, cotransfection with plasmid pGEM3Z/J1, containing the J1 strain 1D-2A sequence, resulted in a 14-fold stimulation of CB4 IRES-dependent LUC expression (Fig. 4A and Fig. 5) and inhibition of CAT expression (Fig. 4B). In contrast, plasmid pGEM3Z/J1Δ (with an in-frame deletion of codons for 53 amino acids in the 1D-2A-coding region) had no significant effect on CAT or LUC expression from the reporter plasmid (Fig. 4 and 5). Interestingly, plasmid pGEM3Z/00 induced a 4.5-fold increase in CB4 IRES-directed LUC expression (Fig. 4A and Fig. 5) but had little or no effect on CAT expression (Fig. 4B), in accordance with its very limited ability to induce eIF4GI cleavage (Fig. 3B). Thus, the 2A protease from the attenuated strain of SVDV was defective in inhibiting cap-dependent protein synthesis and only moderately stimulated CB4 IRES activity, whereas the 2A protease from the virulent SVDV strongly inhibited cap-dependent protein synthesis and greatly stimulated CB4 IRES activity.

FIG. 4.

Differential inhibition of cap-dependent protein synthesis and IRES activation by the SVDV 2A proteases. The indicated test plasmids (Fig. 1) were cotransfected with reporter plasmid pGEM-CAT/CB4/LUC into vTF7-3-infected BHK cells. After 20 h cell extracts were prepared and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using antibodies specific for LUC (A) and CAT (B). Plasmid pAΔ802 expresses the PV 2A protease.

FIG. 5.

Quantitation of CB4 IRES activation by enterovirus 2A proteases in BHK cells. Reporter plasmid pGEM-CAT/CB4/LUC was transfected alone or with the indicated plasmids into vTF7-3-infected BHK cells. LUC activity within cell extracts was determined using a luciferase assay kit (Promega) and luminometer. Results shown are the means ± standard deviations from up to five separate determinations. In each experiment, the LUC expression obtained from the reporter plasmid alone was set at 100% and the relative activities obtained in the presence of the test plasmids were calculated. Extracts were also analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting for CAT and LUC as for Fig. 4, and the results were mutually consistent in each case (data not shown).

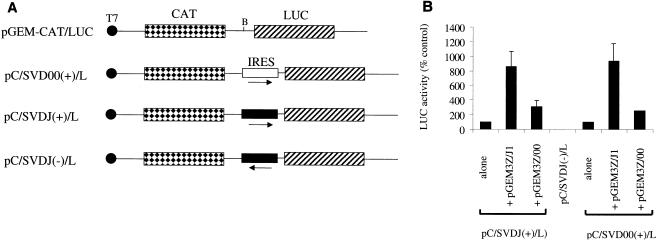

We also performed similar assays using reporter plasmids including the SVDV IRES from both the J1 and 00 strains (Fig. 6A). No significant difference in activities of the SVDV IRES elements from the two strains was apparent in this assay system (data not shown). No significant LUC expression was detected when the SVDV IRES was present in the inverse orientation, as expected (Fig. 6B). The activity of both SVDV IRES elements, in the positive orientation, was strongly stimulated (about ninefold) by the coexpression of J1 1D-2A but rather more weakly (about threefold) by the coexpression 00 1D-2A (Fig. 6B). Thus these results are entirely consistent with the data obtained with the CB4 IRES.

FIG. 6.

Differential activation of the SVDV IRES by SVDV 2A proteases. (A) Structures of reporter plasmids pGEM-CAT/SVDJ(+)/LUC (pC/SVDJ(+)/L), pGEM-CAT/SVDJ(−)/LUC (pC/SVDJ(−)/L), and pGEM-CAT/SVD00(+)/LUC (pC/SVD00(+)/L). The orientation of the SVDV IRES and the source of SVDV cDNA (00, open box; J1, solid box) are indicated. (B) The reporter plasmids were transfected alone or with the indicated plasmids into vTF7-3-infected BHK cells. LUC activity was determined within cell extracts using a LUC assay kit (Promega) and luminometer. Results shown are the means ± standard deviations from three separate determinations. In each experiment, the LUC expression obtained from the reporter plasmid alone was set at 100% and the relative activities obtained in the presence of the test plasmids were calculated. The expression of LUC from pC/SVDJ(−)/L alone was about 1% of that obtained from pC/SVDJ(+)/L alone.

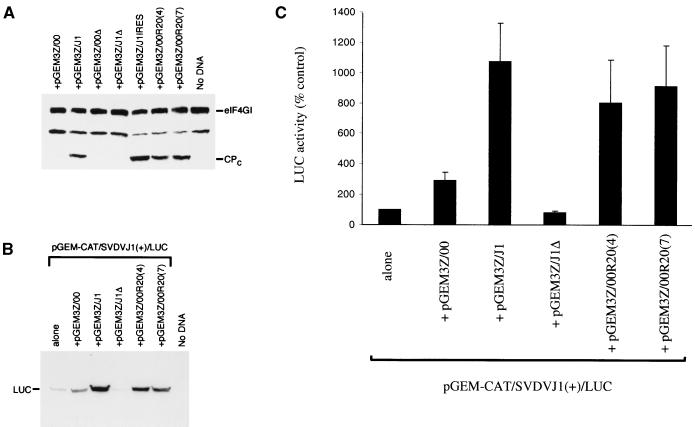

To confirm that the difference in the activities of the J1 and 00 1D-2A plasmids reflected just the amino acid substitution at residue 20 of the 2A protease, this residue was mutated in the 00 1D-2A background from an Ile (I) to Arg (R) using PCR mutagenesis. Two isolates of the resultant plasmid, termed pGEM3Z/00R20, were assayed in the transient expression system. Both displayed the same properties, namely, they induced efficient eIF4GI cleavage (in contrast to the parental pGEM3Z/00 and negative controls pGEM3Z/00Δ and pGEM3Z/J1Δ) in a manner that was similar to that observed with plasmid pGEM3Z/J1 (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, the single point mutation introduced into the pGEM3Z/00 plasmid resulted in a large increase in SVDV IRES activation in BHK cells (Fig. 7B). This result was confirmed in three separate experiments (Fig. 7C), and it was apparent that the efficiency of IRES activation by the pGEM3Z/00R20 plasmids was very similar to that observed with pGEM3Z/J1.

FIG. 7.

Residue 20 within the SVDV 2A protease determines its activity in BHK cells. (A) The indicated plasmids were transfected into vTF7-3-infected BHK cells as for Fig. 3. Cell extracts were analyzed for the integrity of eIF4GI by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. The full-length protein and its C-terminal cleavage product are indicated. (B) The dicistronic reporter plasmid containing the SVDV J1 IRES was transfected alone or with the indicated test plasmids into BHK cells (as for Fig. 6). Samples of cell extract were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-LUC antisera. The extracts were also analyzed for LUC expression by LUC assay. (C) From three separate experiments, performed as described for panel B, the level of LUC expression was measured by LUC assay with a luminometer. The activity observed from the reporter plasmid alone was set at 100% in each case, and other data were compared to it. The results presented are means ± standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

There are two amino acid differences between the J1 and 00 strain 2A proteases. These are at residues 20 and 126. The previous studies (19) on the properties of recombinant SVDVs indicated that the key determinant of virulence is present within a Bst1107I-BssHII fragment of the cDNA (Fig. 1). This region includes the coding sequence for 1D with the N terminus of the 2A protease, including residue 20 but not residue 126. Furthermore, the change in large-plaque to small-plaque phenotype was achieved merely by modification of residue 20 within the 2A protease (19). Hence, it seemed probable that the different properties of the 2A proteins from these two strains of virus reflected just the difference in residue 20. This expectation was verified (Fig. 7).

The 2A proteases from the J1 and 00 strains each very efficiently cleaved the 1D/2A junction in vitro and in vivo, thus indicating that they are both active enzymes. In contrast, it was apparent that there is a major difference in their efficiencies at inducing the cleavage of eIF4GI within BHK cells. It has been demonstrated that recombinant enterovirus 2A proteases can cleave eIF4GI directly in vitro (6, 25). However, this requires a high level of protease (6), whereas within picornavirus-infected cells the cleavage of eIF4GI occurs at very low levels of viral protein expression (3, 10). It has been suggested that a cellular protease may be activated by the viral protease (see reference 2 for a review). However, whether the cleavage of eIF4GI is direct or indirect, it appears that the modification of residue 20 within the 2A protease is sufficient to alter the recognition of a cellular protein by the protease. Since this residue is immediately adjacent to one component of the catalytic triad, it is clearly in the vicinity of the active site. A single amino acid insertion in the PV 2A protease has been shown previously to block eIF4G cleavage and thus to block the early shutoff of host cell protein synthesis (4). However, the modified 2A protease still cleaved the 1D/2A junction since a viable PV (small plaque) was obtained.

It is possible that the plaque size phenotype can reflect the ability of the 2A protease to inhibit cellular protein synthesis. It has been demonstrated recently that infection of cells by FMDV induces the transcription of interferon mRNAs (7). The presence of the FMDV Leader protein blocks cap-dependent protein synthesis and hence blocks interferon production. However, in cells infected by a mutant FMDV lacking the L protease, there was sufficient interferon produced to inhibit virus growth in neighboring cells. Hence, in terms of the SVDV variants, it is conceivable that the infection of cells with the J1 virus, encoding a 2A protease that actively blocks cap-dependent protein synthesis, would block interferon production whereas the 00 virus would induce interferon production. This could explain the small-plaque phenotype for the 00 strain even though the growth rates of the J1 and 00 viruses in a single-step growth curve analysis were indistinguishable (19).

It is interesting that the 2A protease from the 00 strain of SVDV still significantly activated both CB4 and SVDV IRES activity (almost fivefold and threefold, respectively) despite inducing only very low-level cleavage of eIF4GI and having no significant effect on cap-dependent protein synthesis. These data are consistent with the view that IRES activation and eIF4GI cleavage are distinct processes (30). Admittedly the activation (4.5-fold) of the CB4 IRES by the 00 2A protease was less than that achieved with the SVDV J1 2A protease (over 14-fold) or with the PV 2A protease (about 12-fold), but it was similar to that observed with the FMDV Lb protease. The last protein is much more efficient at inducing eIF4GI cleavage than the others (reference 30 and unpublished observations). The stimulation of IRES activity requires an active protease (13), and thus it is assumed that this process requires the cleavage of a cellular protein too.

It has been shown that the individual expression of PV 2A protease in cells can induce apoptosis (9a), but it seems unlikely that the distinct activities of the different SVDV 2A proteases reflect a difference in inducing apoptosis. Cell lysis normally occurs prior to the onset of apoptosis in picornavirus-infected cells. Furthermore it has been noted that eIF4GI is also cleaved in apoptotic cells, but the cleavage products (150 and 80 kDa) are distinct from those generated in picornavirus-infected cells (7a, 31), and we see no evidence for the generation of these alternate cleavage products in our assays (e.g., Fig. 7).

For all three serotypes of PV, key determinants of virulence have been mapped to a small region of the IRES (20, 28, 37). These mutations affect the efficiency of translation of the viral RNA in certain in vitro assay systems (35) and in neuroblastoma cells (24). However, it is not yet understood how these modifications in the PV IRES sequence affect the function of this IRES in a cell type-specific manner. It has been reported that the attenuating mutation within the IRES can reduce interaction with the polypyrimidine tract-binding protein (PTB) within extracts of neuroblastoma, but not HeLa, cell lines (12). PTB is one of several cellular proteins that have been shown to interact with picornavirus IRES elements in vitro and to enhance their activity (reviewed in reference 2).

There has been some previous evidence for a link between the PV 2A protease and neurovirulence (26, 27). However, these earlier studies did not examine the biochemical properties of the 2A proteases derived from viruses that were neurovirulent or not to determine whether these activities were altered. Indeed the effect of the PV 2A protease on mouse neurovirulence was attributed to some undefined role in capsid stability (26). The studies by Macadam et al. (27) analyzed revertants of viruses that were temperature sensitive and attenuated due to the presence of a mutation in the IRES. Some of these revertants had mutations in the 2A-coding region but retained the IRES mutation. Two out of 10 such mutants analyzed had substitutions in residues adjacent to the catalytic triad, and the other substitutions were predicted to occur in two main clusters on the protease surface. Recently additional mutations in 2A that have this effect have been identified (32). It had been suggested initially that the 2A protease may directly interact with the IRES element (27), but the internal location of some of the residues modified in the revertant viruses appears to make this unlikely. It has now been suggested that these mutations may disrupt a protein-protein interaction (32). Indeed, on the basis of our results, these substitutions, which served to overcome the deficit in translational efficiency imposed by the IRES mutation, may function by modifying the interaction of the PV 2A protease with some cellular component involved in the activation of IRES activity.

It seems that modifying the translational efficiency of the viral RNA can be a key determinant of picornavirus virulence. This may be achieved either directly through modifying IRES efficiency (as well documented for PV; see above) or indirectly, as demonstrated here, by modifying the shutoff of host cell protein synthesis and/or the stimulation of IRES activity during virus infection. It is apparent that numerous virus-host interactions determine the outcome of a virus infection within an animal. However, the analyses of the activities of the different 2A proteases shown here do seem to reflect the differences in the pathogenicities of the viruses from which they were derived.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded in part by a grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

We thank Soren Alexandersen and Peter Mason for their interest in this work and helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bazan J R, Fletterick R J. Viral cysteine proteases are homologous to the trypsin-like family of serine proteases: structural and functional implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:7872–7876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.7872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belsham G J, Jackson R J. Translation initiation on picornavirus RNA. In: Sonenberg N, Hershey J W B, Mathews M B, editors. Translational control of gene expression. Monograph 39. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2000. pp. 869–900. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belsham G J, McInerney G M, Ross-Smith N. Foot-and-mouth disease virus 3C protease induces cleavage of translation initiation factors eIF4A and eIF4G within infected cells. J Virol. 2000;74:272–280. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.272-280.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernstein H D, Sonenberg N, Baltimore D. Poliovirus mutant that does not selectively inhibit host cell protein synthesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:2913–2923. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.11.2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borman A M, Le Mercier P, Girard M, Kean K M. Comparison of picornaviral IRES-driven internal initiation in cultured cells of different origins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:925–932. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bovee M L, Lamphear B J, Rhoads R E, Lloyd R E. Direct cleavage of eIF4G by poliovirus 2A protease is inefficient in vitro. Virology. 1998;245:241–249. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chinsangaram J, Piccone M E, Grubman M J. Ability of foot-and mouth disease virus to form plaques in cell culture is associated with suppression of alpha/beta interferon. J Virol. 1999;73:9891–9898. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.9891-9898.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7a.Clemens M J, Bushell M, Morley S J. Degradation of eukaryotic polypeptide chain initiation factor (eIF) 4G in response to induction of apoptosis in human lymphoma cell lines. Oncogene. 1996;17:2921–2931. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuerst T R, Niles E G, Studier F W, Moss B. Eukaryotic transient expression system based on recombinant vaccinia virus that synthesizes bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:8122–8126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gingras A-C, Raught B, Sonenberg N. eIF4 initiation factors: effectors of mRNA recruitment to ribosomes and regulators of translation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:913–963. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9a.Goldstaub D, Gradi A, Bercovitch Z, Grosmann Z, Nophar Y, Luria S, Sonenberg N, Kahana C. Poliovirus 2A protease induces apoptotic cell death. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1271–1277. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.4.1271-1277.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gradi A, Svitkin Y V, Imataka H, Sonenberg N. Proteolysis of human eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF4GII, but not eIF4GI, coincides with the shutoff of host protein synthesis after poliovirus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11089–11094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graves J H. Serological relationship of swine vesicular disease virus and coxsackie B5 virus. Nature (London) 1973;245:314–315. doi: 10.1038/245314a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gutierrez A L, DenovaOcampo M, Racaniello V R, del Angel R M. Attenuating mutations in the poliovirus 5′ untranslated region alter its interaction with polypyrimidine tract-binding protein. J Virol. 1997;71:3826–3838. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3826-3833.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hambidge S J, Sarnow P. Translational enhancement of the poliovirus 5′ noncoding region mediated by virus-encoded polypeptide 2A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10272–10276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inoue T, Suzuki T, Sekiguchi K. The complete nucleotide sequence of swine vesicular disease virus. J Gen Virol. 1989;70:919–934. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-4-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inoue T, Yamaguchi S, Saeki T, Sekiguchi K. Production of infectious swine vesicular disease virus from cloned cDNA in mammalian cells. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:1835–1838. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-8-1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inoue T, Yamaguchi S, Kanno T, Sugita S, Saeki T. The complete nucleotide sequence of a pathogenic swine vesicular disease virus isolated in Japan (J1′73) and phylogenetic analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3896. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.16.3896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaminski A, Howell M T, Jackson R J. Initiation of encephalomyocarditis virus RNA translation: the authentic initiation site is not selected by a scanning mechanism. EMBO J. 1990;9:3753–3759. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07588.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanno T, Inoue T, Mackay D, Kitching P, Yamaguchi S, Shirai J. Viruses produced from complementary DNA of virulent and avirulent strains of swine vesicular disease virus retain the in vivo and in vitro characteristics of the parental strain. Arch Virol. 1998;143:1055–1062. doi: 10.1007/s007050050355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanno T, Mackay D, Inoue T, Wilsden G, Yamakawa M, Yamazoe R, Yamaguchi S, Shirai J, Kitching P, Murakami Y. Mapping the genetic determinants of pathogenicity and plaque phenotype in swine vesicular disease virus. J Virol. 1999;73:2710–2716. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2710-2716.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawamura N, Kohara M, Abe S, Komatsu T, Tago K, Arita M, Nomoto A. Determinants in the 5′ noncoding region of poliovirus Sabin 1 RNA that influence the attenuation phenotype. J Virol. 1989;63:1302–1309. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.3.1302-1309.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kodama M, Saito T, Ogawa T, Tokuda G, Sasahara J, Kumagai T. Swine vesicular disease viruses isolated from healthy pigs in non-epizootic period. II. Vesicular formation and virus multiplication in experimentally inoculated pigs. Natl Inst Anim Health Q. 1980;20:123–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kräusslich H-G, Nicklin M J, Toyoda H, Etchison D, Wimmer E. Poliovirus protease 2A induces cleavage of eucaryotic initiation factor 4F polypeptide p220. J Virol. 1987;61:2711–2718. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.9.2711-2718.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.La Monica N, Racaniello V R. Differences in the replication of attenuated and neurovirulent poliovirus in human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y. J Virol. 1989;63:2357–2360. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.5.2357-2360.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lamphear B J, Yan R Q, Yang F, Waters D, Liebig H D, Klump H, Küechler E, Skern T, Rhoads R E. Mapping of the cleavage site in protein synthesis initiation factor eIF-4γ of the 2A proteases from human coxsackievirus and rhinovirus. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:19200–19203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu H-H, Yang C-F, Murdin A D, Klein M H, Harber J J, Kew O M, Wimmer E. Mouse neurovirulence determinants of poliovirus type 1 strain LS-a map to the coding regions of capsid protein VP1 and proteinase 2Apro. J Virol. 1994;68:7507–7515. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.7507-7515.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Macadam A J, Ferguson G, Fleming T, Stone D M, Almond J W, Minor P D. Role for poliovirus protease 2A in cap-independent translation. EMBO J. 1994;13:924–927. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06336.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moss E G, O'Neill R E, Racaniello V R. Mapping of attenuating sequences of an avirulent poliovirus type 2 strain. J Virol. 1989;63:1884–1890. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.5.1884-1890.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohlmann T, Rau M, Pain V M, Morley S J. The C-terminal domain of eukaryotic protein synthesis initiation factor (eIF) 4G is sufficient to support cap-independent translation in the absence of eIF4E. EMBO J. 1996;15:1371–1382. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberts L O, Seamons R A, Belsham G J. Recognition of picornavirus internal ribosome entry sites within cells; influence of cellular and viral proteins. RNA. 1998;4:520–529. doi: 10.1017/s1355838298971989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts L O, Boxall A J, Lewis L J, Belsham G J, Kass G E N. Caspases are not involved in the cleavage of translation initiation factor eIF4GI during picornavirus infection. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:1703–1707. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-7-1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rowe A, Ferguson G L, Minor P D, Macadam A J. Coding changes in the poliovirus protease 2A compensate for 5′ NCR domain V disruptions in a cell-specific manner. Virology. 2000;269:284–293. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryan M D, Flint M. Virus-encoded proteinases of the picornavirus super-group. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:699–723. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-4-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Svitkin Y V, Cammack N, Minor P D, Almond J W. Translation deficiency of the Sabin type 3 poliovaccine genome: association with the attenuating mutation C472-U. Virology. 1990;175:103–109. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toyoda H, Nicklin M J H, Murray M G, Anderson C W, Dunn J J, Studier F W, Wimmer E. A second virus-encoded protease involved in proteolytic processing of poliovirus polyprotein. Cell. 1986;45:761–770. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90790-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Westrop G D, Wareham K A, Evans D M A, Dunn G, Minor P D, Magrath D I, Taffs F, Marsden S, Skinner M A, Schild G C, Almond J W. Genetic basis of attenuation of the Sabin type 3 oral poliovirus vaccine. J Virol. 1989;63:1338–1344. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.3.1338-1344.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu S F, Lloyd R E. Identification of essential amino acid residues in the functional activity of poliovirus 2A protease. Virology. 1991;182:615–625. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90602-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang G, Haydon D T, Knowles N J, McCauley J W. Molecular evolution of swine vesicular disease virus. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:639–651. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-3-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]