Abstract

This paper presents a numerical investigation into the fire endurance of carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP)-strengthened columns, shielded with fire-resistant materials, in piloti-type reinforced concrete buildings. The strengthened column, equipped with a fire protection system, underwent exposure to the ASTM E119 standard time-temperature curve for a duration of 4 h. To comprehensively evaluate the thermal and structural performance of the strengthened column at elevated temperatures and substantiate the effectiveness of the fire protection system, a fully coupled thermal-stress analysis was conducted. The numerical modeling approach employed in this study was rigorously validated through previous experimental studies in conjunction with adherence to the ACI design guideline, specifically ACI 440.2R-17. Using the validated structural fire model, the thermal and structural behaviors of the RC column with an insulated CFRP strengthening system were investigated based on four key performance criteria: glass transition temperature, ignition temperature of polymer matrix, critical temperature of reinforcing bars, and the design axial load capacity at elevated temperatures. Furthermore, a comparative assessment of fire endurance was performed using diverse fire-resistant materials, including Sprayed Fire-Resistive Material (SFRM) and Sikacrete®-213 F, with insulation thicknesses ranging from 10 to 30 mm, during the 4-hour fire exposure period.

Keywords: Fire performance, Piloti-type RC buildings, CFRP strengthening, Insulation system, Coupled thermal-stress analysis

Subject terms: Civil engineering, Mechanical engineering

Introduction

Many of the low-rise multi-family houses and neighborhood living facilities have adopted the reinforced concrete (RC) piloti-type structures. These structures typically consist of frame structures to accommodate parking spaces on the first floors or to house commercial facilities, while wall structures are employed to provide living spaces on the upper floors1–4. Recent earthquakes in Gyeongju and Pohang have exposed the seismic vulnerabilities of various piloti buildings, resulting in extensive property damage5–7and the loss of parked vehicles due to fires. In the event of a fire, these piloti buildings are particularly susceptible to fire spread, often experiencing a stack effect8,9. The typical structural vulnerabilities of piloti buildings in earthquakes include excessive inter-story drift of the piloti floor and insufficient strength of the piloti column itself10–12. Seismic retrofitting is necessary to address these issues, and it should also incorporate fire endurance measures to ensure prolonged structural performance.

Over the last two decades, there has been a significant increase in the use of fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) materials in civil engineering, especially for seismic retrofit. These materials offer notable advantages, including exceptional strength, stiffness and corrosion resistance13–15. One of the most common applications involves wrapping carbon or glass FRP sheets around the exterior of RC beams, columns and slabs to enhance their strength and ductility. However, it should be noted that the use of FRP strengthening systems in buildings is limited due to the degradation of their mechanical and bond properties at elevated temperatures16–21.

To address this concern, extensive research efforts, both experimental and numerical, have been undertaken to ensure the fire endurance of FRP-strengthening systems when applied to RC beams, slabs and columns22–26. In 2015, Firmo et al27. presented a comprehensive review of the state-of-the-art regarding the fire performance of FRP-strengthened RC structural elements. For slabs and beams, numerous experimental studies assessed the fire endurance of the FRP-strengthening systems28–32. The mechanical and thermal characteristics of FRP, as well as its bond properties to concrete at elevated temperatures, have undergone extensive investigation, including bond tests33–36. However, precisely determining when the effectiveness of the FRP system is compromised in terms of its interaction with concrete has proven challenging.

In the case of columns, only a limited number of studies have investigated the fire resistance behavior of FRP strengthening systems when subjected to both axial loads and fire. Bisby et al37. conducted standard furnace tests on two full-scale CFRP-wrapped circular RC columns, achieving more than 5 h of fire endurance with a 57-mm thick insulation based on ASTM E119-22 requirements38, although the confinement effect of the FRP system at high temperatures was not clearly identified. Simliarly, Chowdhury et al26. tested two CFRP-wrapped RC circular columns protected by a 53-mm thick layer of spray-applied cementitious mortar insulation. The study did not distinctly reveal the mechanical efficiency of the CFRP system at elevated temperatures, echoing the findings in the earlier study of Bisby et al37. Comparable observations were also noted in the studies conducted by Kodur et al39. and Benichou et al40.

Considering the limited number of studies on the structural fire behavior of FRP-strengthened RC columns, and the resulting lack of knowledge regarding the tensile and bond properties of FRP strengthening materials and systems, it is evident that further research in this field is necessary. Furthermore, given the variability in the fire endurance of the strengthened columns, which can be influenced by factors such as specific FRP systems, insulation properties, and column design, additional studies should be conducted to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the fire performance of FRP strengthening systems for columns.

This study presents a numerical investigation into the structural fire performance of RC columns strengthened with CFRP in piloti-type building structures. To ensure the structural integrity of CFRP sheets at elevated temperatures, the fire performance of the CFRP-strengthened RC column with fire protection under sustained axial loads was numerically assessed through coupled thermomechanical analyses, encompassing heat transfer and thermal-stress analysis. The numerical model incorporated temperature-dependent thermal and mechanical properties for the structural components to account for the degradation in the mechanical properties at elevated temperatures24,41. The numerical methodology used to develop the structural fire model of the column was validated using relevant past experimental data from Cree et al23.. They conducted full-scale fire tests on a square RC column strengthened with FRP wraps and covered with a supplemental fire protection system, applying the ULC-S101 standard fire curve for 4 h.

Using the validated numerical modeling methodology, this study investigated the structural fire endurance of CFRP-strengthened piloti column insulated with fire-resistant materials, namely, SFRM42 and Sikacrete®-213 F23, against the standard time-temperature fire curve defined in ASTM E119-2238. Fire endurance ratings based on insulation thickness were evaluated with respect to three performance criteria: CFRP composites glass-transition temperature, ignition temperature of CFRP, and critical temperature of reinforcing bars (rebars). The axial load capacity of the insulated strengthened column at elevated temperatures was also analyzed using a sustained load equivalent to the full service load, as specified in ASTM38and ACI43. Based on these numerical analyses, available design guidance was discussed, and recommendations for future research were provided.

Piloti structures with CFRP strengthening

Target structure

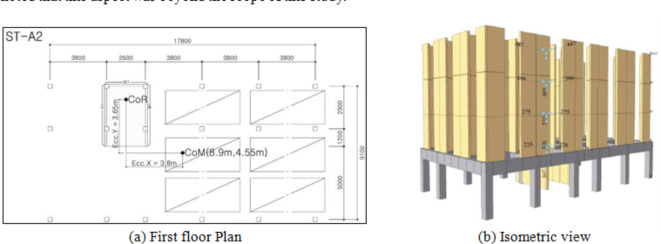

Piloti structures for evaluating the fire performance were taken from Kim2, who categorized eight types of general piloti structures. The piloti structure under consideration consisted of four stories with heights of 11.5 m and total floor areas of 648 m2, as shown in Fig. 1. The first story, designated for open car parking, has a height of 3.4 m. The ceiling in the open car park space was constructed using fire protection materials such as functionally graded material (FGM)44,45to prevent outer flashover46. This was done to prevent flames from penetrating the ceiling and propagating inward between the ceiling and the slab. However, it should be noted that this aspect was beyond the scope of this study.

Fig. 1.

Piloti structure [2].

CFRP sheet strengthening

Shin et al47. previously conducted a seismic performance evaluation of the piloti buildings in Kim2using Seismic Performance Evaluation Method for Existing Buildings48. This evaluation was necessary because piloti structures are known to have inherent seismic vulnerabilities characterized by excessive inter-story drift and insufficient column strength, particularly in the open car park area. It was found that the shear capacities of two columns did not meet the required shear forces at their performance points obtained from the pushover analysis. As such, the columns were strengthened in shear with two layers of unidirectional carbon fiber reinforced polymers (CFRP), as shown in Fig. 2. This strengthening approach, in accordance with ACI 440.2R-1743, aimed to enhance the ductility and strength of the columns, including the confinement effects achieved by completely wrapping the columns with CFRP sheets.

Fig. 2.

CFRP strengthening of piloti RC column [47].

The concrete compressive strength of the columns was estimated to be 17 MPa using Non-Destructive Testing (NDT). Each column contained ten D19 longitudinal rebars with a yield strength of 400 MPa (SD400). The lateral shear rebars (stirrups) comprised D10 rebars with a center-to-center spacing of 200 mm and a clear cover of 40 mm from the exterior concrete surface, where the yield strength was 300 MPa (SD300). The corners of the cross section were rounded with a minimum radius of 25 mm. This column was strengthened using CFRP sheets of type NR43R, which had an ultimate tensile strength of 2677.2 MPa, a tensile elastic modulus of 372652.7 MPa, a failure strain of 0.011, and a thickness of 0.165 mm per layer, as presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mechanical properties of NR34R CFRP sheets47.

| Property | Value | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Ultimate tensile strength (MPa) | 2677.2 | |

| Tensile elastic modulus (MPa) | 372.652.7 | |

| Failure strain | 0.011 | |

| Layer thickness (mm) | 0.165 | Per layer |

Design axial load capacity of CFRP-strengthened RC columns

The design axial load capacity, ϕPn, of the CFRP-strengthened RC rectangular column with steel-tie reinforcement is determined conforming to the ACI design guideline, ACI 440.2R-1743:

|

1 |

where ϕ is the strength reduction factor (= 0.65),  is the maximum confined concrete compressive strength, Ag is the gross area of concrete section, Ast is the total area of longitudinal reinforcement, fy is the specified yield strength of nonprestressed steel reinforcement. The maximum confined concrete compressive strength,

is the maximum confined concrete compressive strength, Ag is the gross area of concrete section, Ast is the total area of longitudinal reinforcement, fy is the specified yield strength of nonprestressed steel reinforcement. The maximum confined concrete compressive strength,  , takes into account the confinement effect of FRP49,50 and includes an additional reduction factor, ψf, of 0.95:

, takes into account the confinement effect of FRP49,50 and includes an additional reduction factor, ψf, of 0.95:

|

2 |

where  is the unconfined cylinder compressive strength of concrete, κa is the efficiency factor that accounts for the geometry of the section (= 0.55), and fl is the maximum confinement pressure.

is the unconfined cylinder compressive strength of concrete, κa is the efficiency factor that accounts for the geometry of the section (= 0.55), and fl is the maximum confinement pressure.

|

3 |

where Ef is the elastic modulus of FRP, n is the number of layer, tf is the nominal thickness of one ply of FRP reinforcement, εfe is the effective strain in CFRP at failure, and D is the diagonal length of the rectangular cross section with dimensions of b×h (= ). For further details on the stress-strain relationship of FRP-confined concrete, ACI 440.2R-17 can be referred to. The effect of slenderness was not considered in this study as the columns under investigation met the condition klu/r≤ 22 for columns not braced against sidesway51.

). For further details on the stress-strain relationship of FRP-confined concrete, ACI 440.2R-17 can be referred to. The effect of slenderness was not considered in this study as the columns under investigation met the condition klu/r≤ 22 for columns not braced against sidesway51.

Fire scenario and modeling

Fire and structural loads

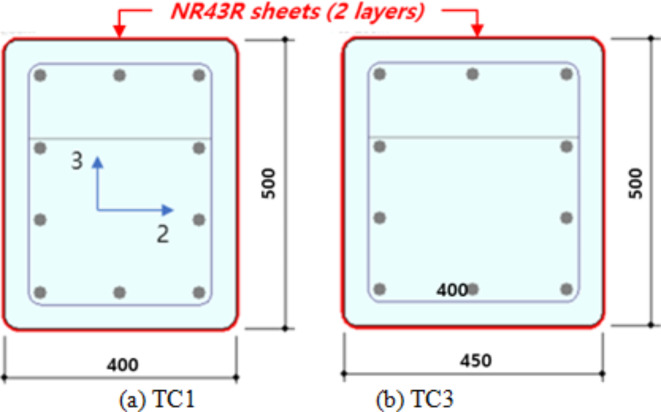

The fire performance of the CFRP-strengthened piloti RC columns insulated with fire-resistant materials was assessed following the requirements specified in ASTM E119-2238. During the evaluation, all four exterior sides of the column were exposed to the ASTM E119-22 standard fire time-temperature curve, as shown in Fig. 3, for a duration of 4 h. The analysis of thermal performance involved the examination of temperatures distribution across the cross section at the column’s mid-height using heat transfer analysis. Subsequently, the structural performance was evaluated by simulating the axial capacity at elevated temperatures through coupled thermal-stress analysis, as described in Sect. Procedure of structural fire evaluation.

Fig. 3.

ASTM E119-22 standard time-temperature curve.

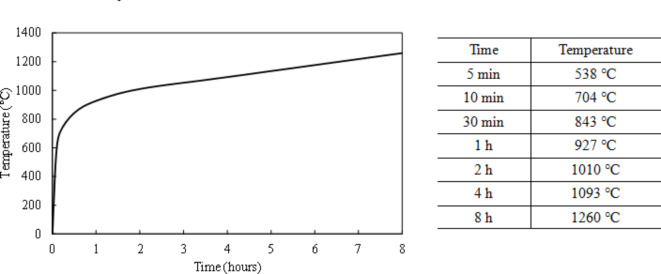

Procedure of structural fire evaluation

The numerical procedure of evaluating the fire performance of columns exposed to the ASTM E119 standard time-temperature curve is shown in Fig. 4. This evaluation was composed of three analyses: strength analysis at room temperature, thermal analysis using heat transfer analysis, and structural analysis employing thermal-stress analysis. For the insulated FRP-strengthened RC column under consideration, the initial step involved conducting strength analysis at room temperature using displacement-controlled loading until the column reached failure to determine the axial load capacity prior to the application of the fire load. This calculated axial load capacity served as a reference for assessing strength deterioration at elevated temperatures.

Fig. 4.

Procedure of structural fire evaluation.

Subsequently, transient heat transfer analysis was performed to obtain the temperature distributions over time. This analysis required temperature-dependent thermal properties of density, conductivity, specific heat and thermal expansion for concrete, steel, CFRP and insulation. The column was subjected to the ASTM E119-22 standard fire for 4 h at this stage. The results of the heat transfer analysis were then evaluated based on the predetermined performance criteria described in Sect. 3.5.

The temperature data derived from the heat transfer analysis were fully mapped into the thermal stress structural model. The structural responses at elevated temperatures were simulated using dynamic implicit analysis, which was employed in this study to simulate the structural response at high temperatures primarily to address the challenges associated with numerical singularity in the stress-coupled thermal stress analysis for evaluating the axial strength of columns. By adopting the dynamic implicit method, these difficulties could be effectively mitigated, allowing for a more stable and accurate numerical simulation. Additionally, because the actual time was directly applied to the analysis, the dynamic approach is expected to provide a response that is closer to the real behavior of the structure under high-temperature conditions compared to static analysis. This method captures the transient effects and temporal evolution of stresses and strains more accurately, which is crucial for understanding the structural response in fire scenarios.

The fire endurance of the column was assessed by verifying that the column withstood a sustained load under the 4-h standard fire conditions, as specified by ASTM38. Temperature-dependent stress-strain relationships of concrete, steel, CFRP and insulation were applied to account for the degradation of the mechanical properties at high temperatures. When the column failed under the sustained load, the insulation thickness was adjusted, and the sequentially coupled thermal-stress analysis was iterated until the axial load capacity at elevated temperatures remained above the applied sustained load.

Thermal and mechanical material properties at elevated temperatures

The numerical model of the CFRP-strengthened RC column with fire-resistant materials comprised concrete, rebars, CFRP sheets and insulation (fire-resistant material). Temperature-dependent mechanical and thermal properties of each material were defined for analysis.

Concrete was modeled using a constitutive material model of Concrete Damaged Plasticity (CDP). The temperature-dependent thermal and mechanical properties were determined based on Eurocode 252. Longitudinal and lateral rebars were modeled using isotopic materials with the temperature-dependent mechanical and thermal properties referencing Buchanan and Abu53. Unidirectional CFRP sheets using NR43R were defined with the properties in Table 1. Orthotropic characteristics were incorporated into the material definition of CFRP for its directionality. Since the CFRP are unidirectional, they exhibit significantly lower tensile strength in directions perpendicular to the longitudinal fibers. The temperature-dependent mechanical and thermal properties of CFRP were defined based on the work of Bisby et al22.. The CFPR sheets were laterally bonded to the column to enhance the shear strength using epoxy polymer. Bond slip was modeled with quadratic traction and defined with an interfacial fracture energy36.

Two fire-resistant materials were considered for fire protection: SFRM and Sikacrete®-213 F. SFRM is a spray-applied fire-resistant material commonly used fire proofing due to its cost effectiveness, ease of application and lightweight properties based on Choi42. It typically consists of gypsum and cement-based materials. The temperature-dependent thermal properties, including specific heat, conductivity and density, were defined based on the experimental work of Choi42. Sikacrete®-213 F, as used in Cree et al23, served as an alternate fire-resistant material. Sikacrete®-213 F is cement-based pre-bagged, dry mix fire protection mortar for wet sprayed application, with a specific focus on concrete structures. It is particularly well-suited for use in hot and tropical climatic conditions. The thermal conductivity, density and specific heat of 0.156 W/m K, 425 kg/m3 and 1888 J/kg K, respectively, as reported in Bhatt et al25, were used for numerical analysis.

Finite element modeling of columns

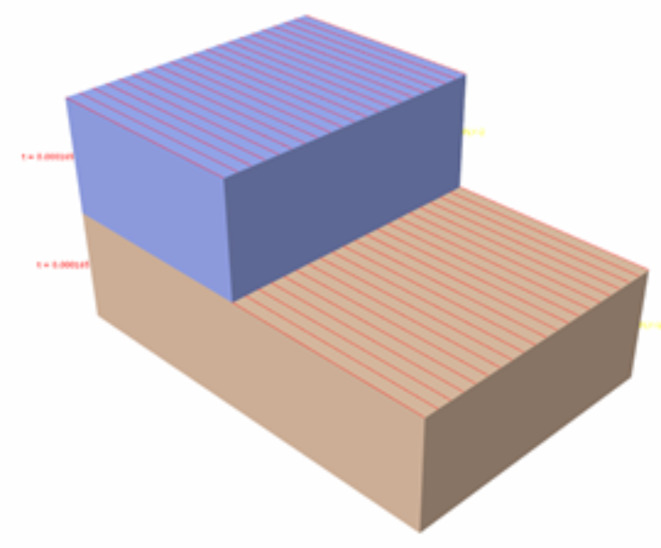

A numerical model of the CFRP-strengthened RC column with fire protections using SFRM or Sikacrete-213 F was developed using a commercial finite element (FE) code, ABAQUS54, as shown in Fig. 5. Concrete was modeled using eight-node linear brick elements with reduced integration and hourglass control (C3D8R). Longitudinal rebars and stirrups were modeled using two-node linear three-dimensional truss elements (T3D2) and embedded into concrete, assuming perfect bond, which was achieved using the embedded region constraint option.

Fig. 5.

FE modeling of column in ABAQUS.

The CFRP sheets, unidirectional composite materials made of a polymer matrix reinforced with fibers, were simulated using four-node doubly curved thin or thick shell elements with reduced integration, hourglass control and finite membrane strains (S4R). They were affixed to the concrete surface using a surface-to-surface contact interaction approach. Figure 6 shows two layers of CFRP sheets modeled in ABAQUS using orthotropic composite materials. The contact surface between the CFRP sheets and the concrete was defined to exhibit cohesive behavior in terms of traction-separation. This included defining the interfacial shear strength using cohesive properties such as stiffness coefficients, Knn, Ktt and Kss, of 2700, 2700 and 2700 N/mm3, respectively, fracture energy of 15.15 N/mm, and damage initiation based on quadratic traction, tnn, ttt and tss, of 270, 270 and 270 N/mm2, respectively. The fire-resistant materials, SFRM and Sikacrete®-213 F, were modeled using C3D8R solid elements and were tied to the CFRP sheets with the assumption of perfect bond.

Fig. 6.

Ply stack plot of CFRP.

The temperatures were estimated through heat transfer analysis at eight monitoring locations at the mid-height of the column, as shown in Fig. 7: ① outer surface of the insulation (fire-resistant material), ② CFRP sheet, ③ concrete surface, ④ shear reinforcement (stirrup), ⑤ longitudinal rebar on the side, ⑥ longitudinal rebar at the corner, ⑦ 1/4 of the cross-sectional dimension from the concrete surface, and ⑧ center of the concrete cross section.

Fig. 7.

Monitoring locations of temperature at mid-height.

Performance criteria

Four performance criteria have been established to assess the numerical results pertaining to the thermal and structural performances of the insulated CFRP-strengthened RC column exposed to fire:

Criterion 1 ensures that the average temperature of CFRP sheets does not surpass the glass-transition temperature, Tg, of the matrix polymer and bonding adhesives41. Exceeding this temperature can result in the loss of the FRP confinement effect, and it has been adopted as a design criterion to permit the use of CFRP in building applications. The Tgthreshold was set at 71℃23, noting commercially available polymers typically exhibit Tgvalues ranges from 60℃ to 82℃43.

Criterion 2 is that the temperatures at the outer face of CFRP sheets should not exceed the ignition temperature of polymer matrix, Tig41. The criterion is crucial to prevent the generation of toxic gases, smoke, and the escalation of flame spread. The designated ignition temperature was set at 450 ℃55.

Criterion 3 stipulates that the rebar temperatures, Tr, should not exceed 593℃, in accordance with the requirements of ASTM E119-2238. It should be noted that there was no specific temperature requirement for concrete.

Criterion 4 is that the axial compressive load capacity of the column should not fall below the full unfactored service load (sustained load) of strengthened members38,41. This criterion aligns with the traditional ULC-S101 failure criterion currently applied to RC columns in buildings in Canada. The sustained loads were determined as full service loads, utilizing the load and resistance factor design approach described in ASTM E119-2238and ACI 440.2R-1743, with a dead-to-live load ratio of 2.5, presuming that dead load dominates in the case of concrete column loads. The load factor on total specified load, α, of 1.314, as used in ASTM E119-2238, was thus adopted in this study. The required superimposed load on the column was then computed by dividing the design axial compressive strength, ϕPn, by α(1.314), and this value represented the sustained loads. Consequently, the sustained loads were estimated to be approximately 76% of the design axial strength according to ACI 440.2R-1743. Failure of the column was deemed to occur if the simulated design axial strength of the column at elevated temperatures dropped below the sustained load.

Validation of structural fire model

Piloti RC column

A validation study was conducted using an experimental study by Cree et al23. to demonstrate the rationality of the FE modeling methodology for the insulated CFRP-strengthened column, as described in Sect. 3. Cree et al. achieved fire tests following the procedure in ACI 440.R2-1743. The test specimen was an RC column with dimensions of 305 × 305 × 3734 mm, strengthened with carbon FRP (SikaWrap Hex 103 C) and fire-resistant material (Sikacrete®-213 F).

In the validation process, a preload equivalent to 88% of the design capacity of the column was applied for 1 h before exposing it to the ASTM E119 standard fire curve for 4 h. To demonstrate the robustness of the FE modeling method, a fully coupled heat transfer and thermal-stress analysis was carried out using ABAQUS. The calculated thermal and structural responses were then compared with the experimental results obtained by Cree et al23..

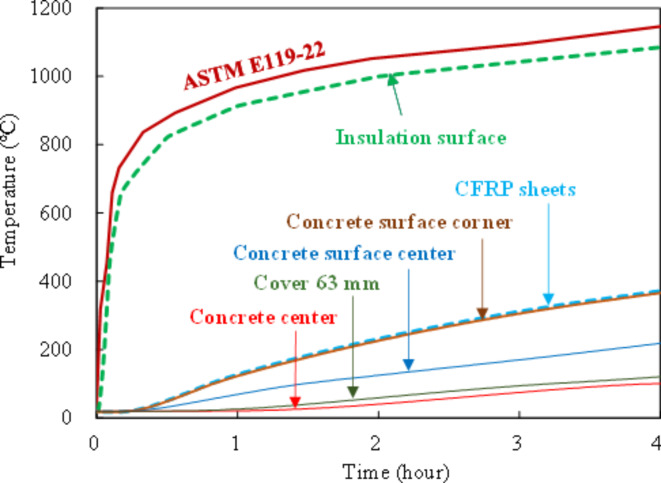

Validation of heat transfer analysis

Figure 8 shows the temperature-time histories calculated from the heat transfer analysis for six locations at mid height: insulation surface, CFRP sheets, concrete surface at the corner, concrete surface on the side, 63 mm from the concrete cover, and the center of the cross section. The temperatures recorded on the insulation surface were slightly lower than those on the ASTM E119-22 standard fire curve, with differences of less than 10%. It is evident that the temperatures of the structural components exhibited a significant decrease due to the presence of fire-resistant materials.

Fig. 8.

Results of heat transfer analysis.

These results of temperature histories compared to the test results of Cree et al23. are shown in Fig. 9. Slight differences were observed between the numerically calculated temperatures and test data for the insulation surface, particularly at the onset of fire exposure. However, these differences diminished as the duration of fire exposure increased. Regarding CFRP, there was a discrepancy around 100 ℃ between the numerical predictions and test results. The plateau around 100 ℃ in the fire test was attributed to the moisture evaporation within the insulation, as explained by Cree et al23. This moisture effect was not accounted for in the numerical model. Nevertheless, it can be concluded that the numerical calculations and test data exhibited a reasonable level of agreement, especially concerning the behavior during 4 h of fire exposure. For the concrete temperatures on the surface and at the center of cross section, the heat transfer calculations reasonably predicted the measured temperatures. The FE model of heat transfer analysis was therefore deemed to be validated.

Fig. 9.

Comparison between numerical predictions and test results.

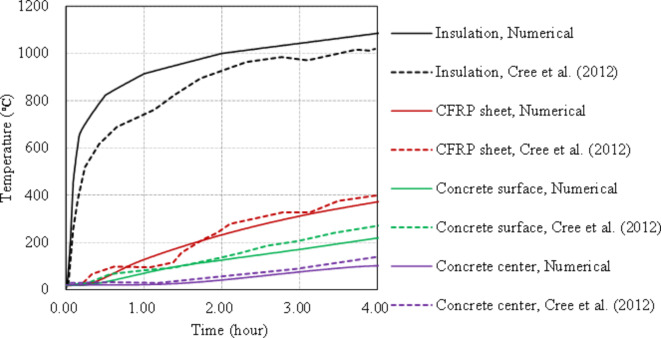

Validation of coupled thermal stress analysis

Axial load and deformation histories

The axial load and deformation histories, calculated through the sequentially coupled thermal-stress analysis, were subjected to a comparative evaluation with the test results in Cree et al23. A preload of axial compression of 1717 kN was applied for approximately 20 min and maintained during the fire test. This applied load corresponds to 75% of the ultimate strengthened design capacity, as per ACI 440.2R-1743. After the first hour, the column was exposed to the ASTM standard fire curve for an additional 4 h. At the 5-h mark, the axial load was incrementally increased until the point of failure was observed.

Figure 10(a) enables a comparison of axial load histories between the numerical predictions and test results. The applied loads over time in the thermal-stress analysis closely align with the test results, indicating the accurate application of the sustained load. The result of axial deformation history is presented in Fig. 10(b). It is seen that the computed axial deformation curve over time curve exhibits an acceptable degree of similarity to the measured values obtained during the tests. The sequentially coupled thermal-stress analysis was therefore considered to be validated.

Fig. 10.

Comparison of load and deformation histories between numerical predictions and test results.

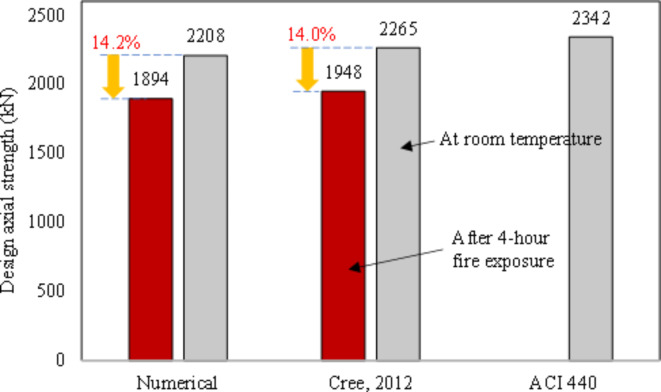

Design axial strength

Cree et al23. reported the estimated design axial strengths of the insulated CFRP-strengthened column based on the temperature measurements, using the approximate normalized strength and modulus curves provided by Chowdhury et al34.. The design axial strengths at room temperature were estimated to be approximately 2265 kN at room temperature and 1948 kN after undergoing 4 h of fire exposure, as shown in Fig. 11; Table 2. The coupled thermal-stress analysis conducted in this study yielded design axial strengths of 2208 kN at room temperature and 1894 kN after 4 h of fire exposure.

Fig. 11.

Design axial load capacities at elevated temperatures between numerical predictions, test results and ACI 440.2R-17.

Table 2.

Comparison of design axial capacities between numerical predictions, test results and ACI 440.2R-17.

| Fire condition | Design axial capacity (kN) | Differences from numerical predictions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numerical | Test results (Cree et al. [23]) |

ACI 440.2R-17 [43] |

Test results (Cree et al. [23]) |

ACI 440.2R-17 [43] |

|

| Room temp. | 2208 | 2265 | 2342 | 2.5% | 5.7% |

| 4-h fire | 1894 | 1948 | - | 2.8% | - |

When comparing these numerical predictions with the test results obtained by Cree et al., there was a discrepancy of 2.5% at room temperature and 2.8% after 4 h of fire exposure. Furthermore, the design strength in accordance with ACI 440.2R-17 was calculated to be 2342 kN, which exhibited a difference of 5.7% in comparison to the numerically calculated design strength at room temperature (2208 kN). Based on these comparisons, it can be concluded that the numerical model effectively predicted the design axial strengths at elevated temperatures.

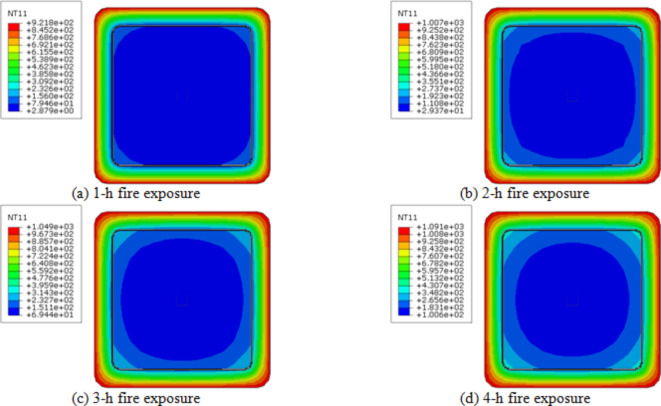

Figure 12 illustrates the temperature distributions across the column’s cross section at mid-height at 1, 2, 3 and 4 h of exposure to fire using the validated numerical model. The strengthened column demonstrates effective protection through the surrounding insulations. After 1 h of fire exposure, the maximum CFRP temperature exceeded 71 °C, which aligns with Criterion 1 defined in Section 3.5. However, this temperature did not surpass the ignition temperature, Tig, of 450 °C, which served as Criterion 2, even after a prolonged 4-h fire exposure. The maximum temperatures recorded on the concrete surface were as follows: 124 °C (1 h), 231 °C (2 h), 301 °C (3 h), and 372 °C (4 h). Similarly, at the center of the cross-section, temperatures were 6 °C (1 h), 28 °C (2 h), 58 °C (3 h), and 89 °C (4 h). As for the longitudinal rebars and stirrups, their maximum temperatures after 4 h of fire exposure were 271 °C and 266 °C, respectively, which are significantly below the critical rebar temperature of 593 °C specified in Criterion 3. This data demonstrates the efficacy of the fire protection measures employed.

Fig. 12.

Temperature distributions across cross section at mid height according to the level of fire exposure.

Fire endurance of piloti column with CFRP strengthening

Fire-protected column modeling

The fire performance evaluation of the CFRP-strengthened piloti RC column, which was insulated with fire-resistant materials as described in Sect. 2, was carried out using the established fire modeling methodology. This methodology was validated through sequentially coupled thermal-stress analysis, as elaborated in Sects. 3 and 4. The analysis focused on a rectangular tied RC column measuring 450 × 500 × 3000 mm. This column had been strengthened using NR34R CFRP sheets with two layers, each 0.165 mm thick, as illustrated in Fig. 2(b). The primary objective was to assess the column’s fire resistance against the ASTM E119-22 standard fire curve over a 4-hour duration. The investigation of the thermal and structural performance of the insulated strengthened column was conducted considering different fire-resistant materials and varying insulation thicknesses. Specifically, three insulation thicknesses of 10, 20, and 30 mm were applied.

Mesh convergence study

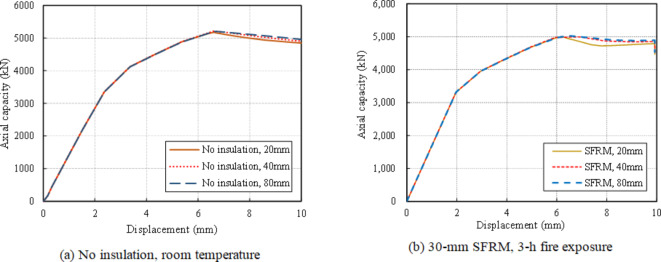

Prior to initiating the structural fire analysis of the piloti column, a mesh convergence study was conducted for both heat transfer and coupled thermal-stress analyses. Two CFRP-strengthened RC columns were considered: one without insulation and the other with the 30-mm SFRM. The analysis for heat transfer was conducted at six monitoring locations: insulation surface, CFRP sheet, side rebar, corner rebar, concrete surface, and concrete center of the cross-section at the column’s mid-height. Three mesh sizes of 20, 40, and 80 mm were selected. Figure 13 presents the results for the 30-mm insulation. For all monitoring locations, the mesh sizes of 20 and 40 mm demonstrated sufficient convergence, while the 80-mm mesh size yielded somewhat different results, particularly for the CFRP sheets and concrete surface during the 4-h fire exposure. Mesh sizes less than 40 mm were thus considered suitable for subsequent heat transfer analyses.

Fig. 13.

Mesh convergence for heat transfer analysis.

For coupled thermal-stress analysis, the mesh convergence was examined in both the absence of insulation and the presence of the 30-mm SFRM. Figure 14 displays the results of the axial capacities as a function of displacement for no insulation at room temperature and 30-mm SFRM during 3-h fire exposure. It was observed that both cases exhibited convergence for all mesh sizes. Thus, mesh sizes of 40 mm or less were employed for the coupled thermal-stress analysis, consistent with the heat transfer analysis mentioned previously.

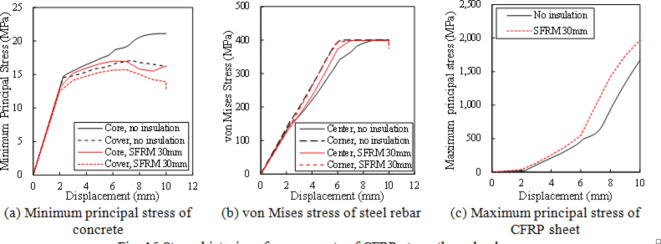

Local responses of column components

The stress states of the two columns under fire, as considered in Sect. 5.2, were examined to understand the failure mechanisms of the columns. Figure 15 shows the stress histories of concrete, steel rebar, and CFRP at a height of 4.8 m, where the maximum stresses were observed. It is evident that the minimum principal stresses in the concrete reach the yield point at a displacement of approximately 2 mm for all cases, as shown in Fig. 16(a), indicating that the compressive strength limits have been reached. This resulted in a decrease in stiffness and axial capacity of the columns, as illustrated in Fig. 14(a) and 14(b). Due to the confinement effect, the minimum principal stresses were greater in the concrete core.

Fig. 15.

Stress histories of components of CFRP-strengthened column.

Fig. 16.

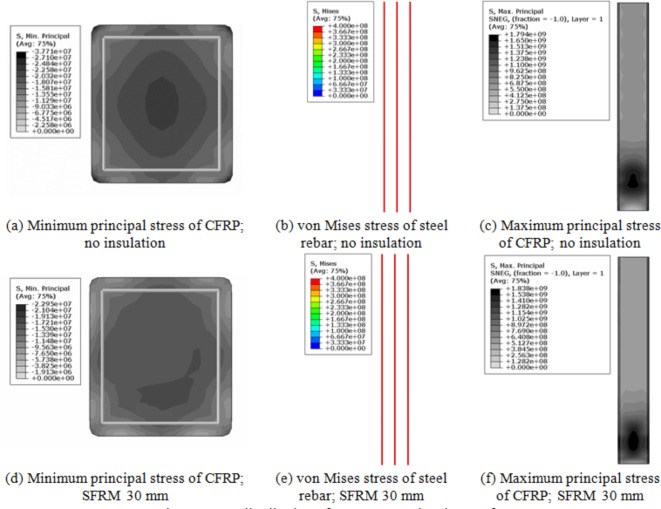

Stress distribution of concrete, steel and CFRP for.

Fig. 14.

Mesh convergence for thermal-stress analysis.

The maximum axial capacities were achieved at a displacement of approximately 6 mm, which is attributed to the yielding of the steel rebars, as shown in Fig. 15(b). Since the CFRP sheets were used to provide lateral strengthening, they did not significantly contribute to increasing the axial capacity independently.

As the concrete expands under compressive load, tensile stresses begin to dominate in the CFRP sheets. This behavior was analyzed using the maximum principal stress histories of the CFRP sheets, as shown in Fig. 15(c). Initially, the maximum principal stresses in the CFRP were minimal because there was insufficient expansion of the concrete to generate significant tensile stresses until the concrete yielded. The maximum principal stresses increase immediately after a displacement of 2 mm (yield point of the concrete) and escalate sharply at a displacement of 6 mm (yield point of the steel rebar). These results indicate that as the concrete expanded under compressive load, tensile stresses were generated in the CFRP sheets due to the confinement effect.

The simulation results at a displacement of 10 mm are presented in Fig. 16, illustrating the stress distributions on the structural components for both the non-insulated column and the column with 30 mm of SFRM insulation. The minimum principal stresses were concentrated at the center of the concrete core, with larger stresses observed in the non-insulated column.

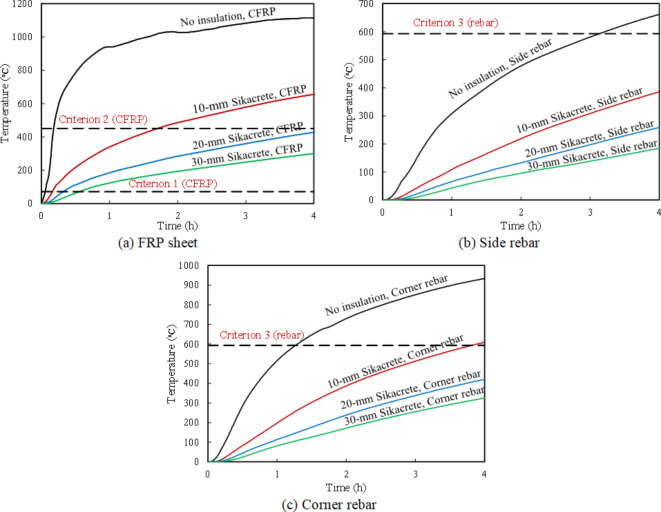

Thermal evaluation

The thermal performance of the insulated CFRP-strengthened column was evaluated based on the Criteria 1, 2, and 3 in Sect. 3.5. Figure 17 presents the results of the heat transfer analysis when SFRM was applied to the column. It is evident that the temperatures on the structural components were effectively reduced as the insulation thickness increased. In the absence of insulation, the temperatures on the CFRP closely matched the temperatures specified in the ASTM E119-22 fire curve. With the 10-mm SFRM thickness, these temperatures were reduced from 924 °C to 347 °C, 1015 °C to 556 °C, 1072 °C to 704 °C, and 1106 °C to 815 °C after 1, 2, 3, and 4 h, respectively. For the 20-mm thickness, the temperatures were even lower, reaching 186 °C, 312 °C, 419 °C, and 513 °C after the same durations. The temperatures were further reduced with the 30-mm thickness, reaching 127 °C, 212 °C, 292 °C, and 363 °C.

Fig. 17.

Results of heat transfer analysis for SFRM varying insulation thickness.

It should be noted that the temperatures at the corner rebar (location 6 in Fig. 7) were greater than those at the side rebar (location 5 in Fig. 7) due to the corner rebars being exposed to temperatures from two sides, whereas the side rebars were influenced by temperatures from only one side. This observation aligns with the findings from previous fire tests conducted by Cree et al. (2012). The maximum temperatures for the corner rebar (no insulation) were calculated as 510 °C, 729 °C, 849 °C, and 930 °C for 1, 2, 3 and 4-h fire exposures, respectively. For the 10-mm SFRM, these temperatures were reduced to 236 °C, 467 °C, 617 °C, and 720 °C. For the 20-mm SFRM, they were even lower at 129 °C, 291 °C, 426 °C, and 541 °C. Finally, with the 30-mm SFRM, the maximum temperatures reached 91 °C, 202 °C, 305 °C, and 400 °C.

The fire endurance of CFRP sheets was assessed with regard to two aspects: the glass transition temperature related to the effect of CFRP confinement and the ignition temperature associated with the evolution of toxic gas and smoke. The results of the fire endurance evaluation for SFRM are shown in Fig. 18. It was observed that the glass transition temperatures of CFRP (71℃) were reached at 3.2, 10, 19, and 32.4 min for no insulation, SFRM thicknesses of 10, 20, and 30 mm, respectively. This indicates that the CFRP confinement effects were lost at these specific time points. These results suggest that the time at which the temperature drops below the Tg onset can be constrained depending on the insulation system, particularly concerning bond performance to the concrete surface. The ignition temperatures of CFRP (450℃) were reached at 11 min, 1.4 h, and 3.3 h, respectively, for configurations with no insulation, 10 mm, and 20 mm. This indicates that there was no resistance to ignition and flaming beyond these time durations.

Fig. 18.

Evaluation of fire endurance for SFRM.

Based on Criterion 3, it was determined that rebar temperatures exceeded 593℃ at 1.3 and 2.8 h for configurations with no insulation and 10-mm SFRM, respectively. This implies that the corner rebars lost 50% of their strength at these specific times. However, the columns utilizing the 20 and 30-mm SFRM maintained their rebar temperatures below 593 ℃ for the entire 4-h duration. The summarized results of the heat transfer analysis evaluation based on the first three criteria can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Fire endurance ratings for CFRP-strengthened RC column insulated with SFRM.

| Insulation | Criterion 1 (CFRP) | Criterion 2 (CFRP) | Criterion 3 (Side rebar) | Criterion 3 (Corner rebar) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tg < 71 ℃ | Tig < 450 ℃ | Tr < 593 ℃ | Tr < 593 ℃ | |

| No insulation | 3.2 min | 11 min | 3.1 h | 1.3 h |

| 10-mm SFRM | 10 min | 1.4 h | – | 2.8 h |

| 20-mm SFRM | 19 min | 3.3 h | – | – |

| 30-mm SFRM | 32.4 min | – | – | – |

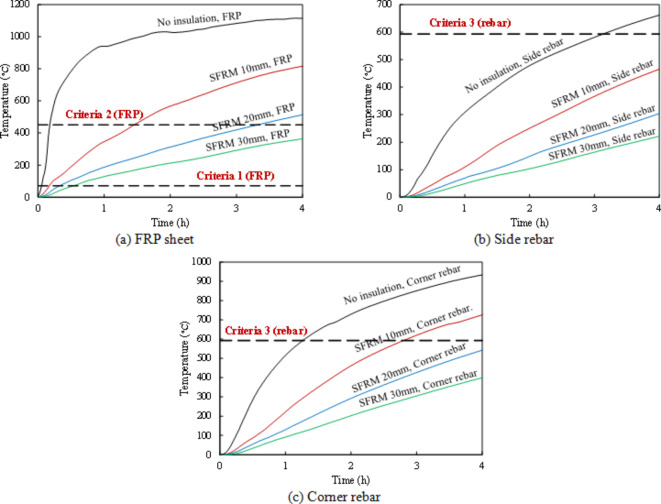

The results of the heat transfer analysis for Sikacrete®-213 F are presented in Fig. 19. Similar to the results for SFRM, increasing the insulation thickness was effective in significantly reducing the temperatures of all structural components. For the 10-mm thickness, the applied temperatures decreased to 341 ℃, 485 ℃, 579 ℃, and 655 ℃ after 1, 2, 3, and 4 h, respectively. With the 20-mm insulation, temperatures decreased further to 183 ℃, 284 ℃, 359 ℃, and 427 ℃, respectively. For the thickest insulation of 30 mm, temperatures reached 123 ℃, 193 ℃, 248 ℃, and 300 ℃ after the same time intervals.

Fig. 19.

Results of heat transfer analysis for Sikacrete®-213F varying insulation thickness.

It is worth noting that, as observed previously, corner rebars exhibited higher temperatures compared to side rebars. Corner rebars were affected by temperature from two sides, unlike the side rebars, which were subjected to heat from only one side. The maximum calculated rebar temperatures (corner rebar) for no insulation reached 510 ℃, 729 ℃, 849 ℃, and 930 ℃ after 1, 2, 3, and 4 h, respectively. For the 10-mm insulation, the temperatures were 196 ℃, 386 ℃, 513 ℃, and 610 ℃, respectively. With the 20-mm insulation, the temperatures were 113 ℃, 238 ℃, 338 ℃, and 419 ℃, respectively. For the 30-mm insulation, the temperatures were 82 ℃, 172 ℃, 255 ℃, and 327 ℃ after the same time durations.

Figure 20 allows for the evaluation of the simulated temperatures against the thresholds defined in the three performance criteria. In terms of Tg (71℃), the results indicate that this temperature was reached at 3.2, 9.6, 19, and 33.3 min for no insulation, 10, 20, and 30-mm insulation thickness, respectively. Note that these results were similar to those observed with the application of SFRM. However, better fire endurance performance was identified for Criteria 2 and 3 with Sikacrete®-213 F. For the 10-mm insulation, the ignition temperatures, Tig, were reached at 1.4 and 1.7 h for SFRM and Sikacrete®-213 F, respectively. With the 20-mm insulation, Tig was reached at 3.3 h for SFRM, while it was not reached for Sikacrete®-213 F.

Fig. 20.

Evaluation of fire endurance for Sikacrete®-213F.

Sikacrete®-213 F also exhibited superior fire endurance for rebars. The critical temperatures, Tr, indicating a 50% loss of compressive strength, for corner rebars were reached at 2.8 h and 3.8 h for SFRM and Sikacrete®-213 F, respectively. For the 20-mm insulation, Tr was reached at 3.3 h for SFRM, but the rebar temperatures for Sikacrete®-213 F remained below 593℃ for 4 h. Sikacrete®-213 F at the 30-mm insulation also resulted in rebar temperatures below 593℃ for 4 h, matching the performance of SFRM. The summarized results of the heat transfer analysis for Sikacrete®-213 F applications are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Fire endurance ratings for CFRP-strengthened RC column insulated with Sikacrete®-213 F.

| Insulation | Criterion 1 (CFRP) | Criterion 2 (CFRP) | Criterion 3 (Side rebar) | Criterion 3 (corner rebar) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tg < 71 ℃ | Tig < 450 ℃ | Tr < 593 ℃ | Tr < 593 ℃ | |

| No insulation | 3.2 min | 11 min | 3.1 h | 1.3 h |

| 10-mm Sikacrete | 9.6 min | 1.7 h | – | 3.81 h |

| 20-mm Sikacrete | 19 min | – | – | – |

| 30-mm Sikacrete | 33 min | – | – | – |

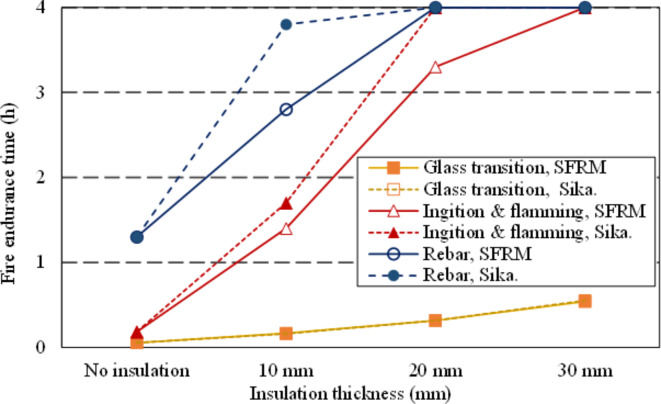

A comparative analysis of the fire endurance effects of the considered fire-resistant materials, SFRM and Sikacrete®-213 F was herein conducted. The fire endurance time plotted against insulation thickness is shown in Fig. 21. For Criterion 1, both SFRM and Sikacrete®-213 F achieved the fire endurance of 0.5-h with the 30-mm thickness. Regarding the ignition and flaming of CFRP (Criterion 2), the 1-h fire endurance was attained with the minimum insulation thickness of 10 mm for both fire-resistant materials. For the 20-mm thickness, SFRM provided the 3-h fire endurance, while Sikacrete®-213 F achieved the 4-h fire endurance. This indicates that Sikacrete®-213 F exhibited somewhat superior thermal performance as a fire protection material for this criterion. Both fire-resistant materials led to the 4-h fire endurance with the 30-mm thickness. In terms of rebar temperatures, the 10-mm thickness resulted in fire endurances of 2 h for SFRM and 3 h for Sikacrete®-213 F. With the 20 and 30-mm thicknesses, both materials achieved the 4-h fire endurance.

Fig. 21.

Fire endurance time as a function of insulation thickness.

The results for SFRM and Sikacrete®-213 F based on Criteria 1 are similar because, at the initial stage of fire exposure, both materials provide comparable thermal insulation, effectively delaying heat transfer due to their similar low-temperature thermal characteristics. However, for Criteria 2 and Criteria 3, the fire endurance times differ significantly. This difference occurs because Sikacrete®-213 F exhibits superior thermal stability and lower thermal conductivity at higher temperatures, which allows it to maintain its structural integrity and provide longer fire resistance under prolonged exposure. In contrast, SFRM’s thermal properties degrade more quickly at elevated temperatures, leading to shorter fire resistance times. Therefore, while both materials perform similarly at lower temperatures, Sikacrete®-213 F offers better fire protection at higher temperature benchmarks.

It’s important to highlight that, based on the numerical results, both fire-resistant materials may not be able to maintain CFRP temperatures below Tg for a sufficient period during a fire event. However, when using insulation thicknesses greater than 20 mm, it was possible to achieve fire endurances of more than 3 h for ignition and flaming of CFRP, and 4 h for rebar temperatures. This implies that there would be no significant deterioration in the mechanical properties of concrete and steel, and the axial load capacities of the column could be maintained. This aspect is further corroborated in Sect. 5.4, which presents an evaluation of the axial load capacities at elevated temperatures compared to the required service loads (sustained loads).

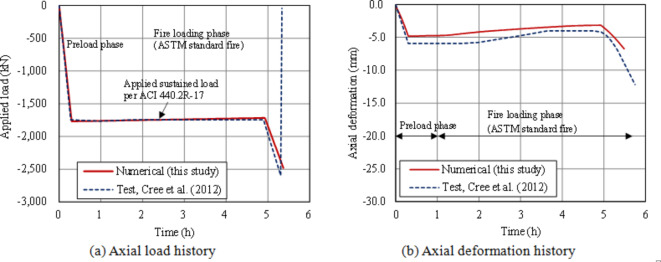

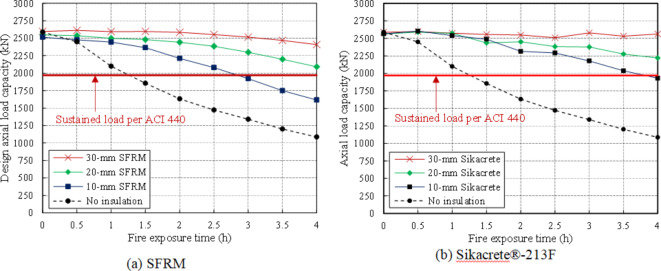

Structural evaluation

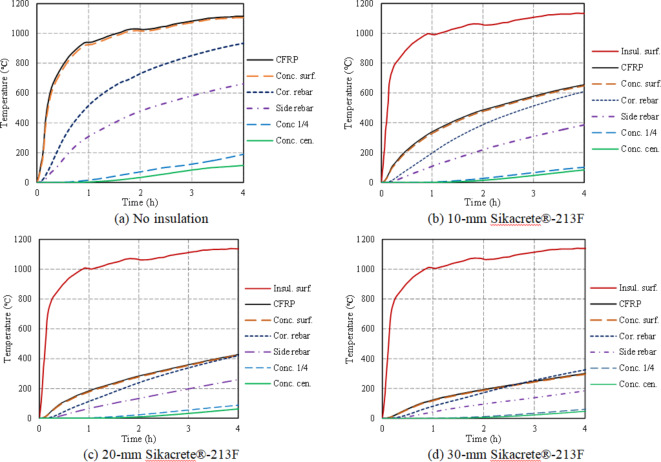

The design axial capacities according to the insulation thicknesses of Sikacrete®-213 F and SFRM were estimated through a parametric analysis using the sequentially coupled thermal-stress analysis, as described in Sect. 3.2. This process involved first conducting a heat transfer analysis, followed by a stress analysis using the structural model into which the temperature data were fully mapped. This sequence of analyses was performed iteratively until the column reached its maximum load capacity. The structural fire endurance performance was evaluated based on the Criterion 4, where the column was considered to have adequate fire endurance if the computed design axial capacity did not drop below the sustained load, as described previously in Sect. 3.5. The ultimate strengthened design load capacity according to ACI 440.2R-17, as described in Sect. 2.2, was estimated to be 2588 kN at room temperature. Therefore, the sustained load with the load factor, α, of 1.314 was calculated to be 1969 kN, which corresponds to 76% of the ACI 440.2R-17 design capacity.

Figure 22(a) presents the results of the design axial strengths as a function of fire exposure duration for SFRM. Each point represents a separate coupled thermal-stress analysis conducted at specific fire exposure times. For instance, the points for the 1-h fire exposure were obtained by applying an axial load to the column 1 h after it was exposed to fire. Without insulation, the design strength significantly decreased after approximately 0.5 h of fire exposure and reached the sustained load after approximately 1.24 h. When SFRM with the thickness of 10 mm was applied, the fire endurance was significantly improved, maintaining the axial strength above the sustained load for 2.8 h. For the columns protected with the 20 and 30-mm SFRM, the axial strengths remained above the sustained load for the full 4 h of fire exposure.

Fig. 22.

Design axial load capacities as a function of fire exposure time for SFRM and Sikacrete®-213F.

The results for Sikacrete®-213 F are presented in Fig. 22(b). For the 10-mm insulation thickness, the design strength dropped to the sustained load at 3.8 h, demonstrating better fire endurance compared to SFRM. For the 20 and 30-mm thicknesses, the design strengths did not fall below the sustained load for the entire 4-h fire exposure, similar to those for SFRM, noting that there was no momentous strength degradation for the 30-mm thickness. It is also worth noting that while the CFRP strengthening system may be ineffective within the first 0.5 h due to temperatures in excess of the glass transition temperatures, the insulation system enabled the column section to maintain its strength to resist the sustained load in the majority of cases. This was because the temperatures of the concrete and rebars did not exceed their critical points, and their strengths were thus not significantly degraded.

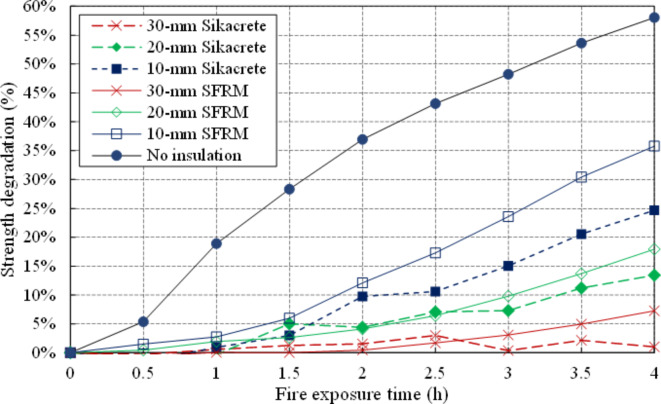

Figure 23 allows for a comparison of how the axial strength degrades over time when exposed to fire between SFRM and Sikacrete®-213 F. The strength of the non-insulated column, exposed to the ASTM E119-22 standard fire, decreased by 58% after 4 h. For the 10-mm thickness, SFRM showed a strength degradation of 36%, while Sikacrete®-213 F exhibited a lower reduction of 25%. For the thicknesses of 20 and 30 mm, both SFRM and Sikacrete®-213 F resulted in strength degradations of less than 20%. This demonstrates that the supplementary insulation systems effectively protect against fire-induced reduction in axial load capacity.

Fig. 23.

Strength degradation as a function of fire exposure time for SFRM and Sikacrete®-213F.

Concluding remarks

A numerical study was conducted using a fully coupled thermal-stress analysis to investigate the fire endurance of RC columns strengthened using CFRP sheets in piloti structures subjected to the ASTM E119-22 standard fire curve for 4 h. Fire protection systems using SFRM and Sikacrete®-213 F were applied by varying the thicknesses. Four performance criteria were established for the evaluation of the column’s fire endurance performance. The following conclusions can be drawn from the results of this study:

Both insulation fire protection systems, with the 30-mm thickness, were able to maintain the CFRP temperature below the Tg onset of 71 °C for 32 min. While this duration may not be fully adequate, there was no significant deterioration in the mechanical properties of materials and axial capacity of the column during 4 h of fire exposure.

Insulation with a thickness exceeding 20 mm led to 3-h fire endurance ratings, preventing the ignition and flaming of CFRP, as well as 4-h fire endurance ratings to maintain the rebar temperature below the critical threshold for both insulation materials. This indicates the effectiveness of the considered insulation systems.

The RC columns strengthened with insulation thicknesses of 20 mm and greater achieved 4-h fire endurance ratings in terms of axial load capacity. The design strengths remained above the sustained loads determined in accordance with ACI 440.2R-17 for the entire 4-h duration of fire exposure.

It can be firmly asserted that the employed insulation systems using SFRM and Sikacrete®-213 F were highly effective in protecting the CFRP-strengthened RC column during a fire event. It is worth noting that Sikacrete®-213 F showed marginally superior structural fire performance compared to SFRM.

The numerical model was experimentally and analytically validated, and it reasonably predicted the thermal and structural behaviors of the insulated CFRP-strengthened RC column. The presented modeling methodology would prove valuable for predicting the structural fire performance of buildings incorporating diverse FRP strengthening systems.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (Nos. 2021R1A4A1031201, 2021R1C1C1012833).

Author contributions

J.S.: Conceptualization, Validation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing - Original draft preparation. H.L.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Validation, Visualization. I.-R.C.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Writing - Review & Editing. J.-K.M.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing - Original draft preparation. S.-M.C.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing.

Data availability

Data will be made available upon request by the first or corresponding author.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Baek, E. L., Oh, S. H. & Lee, S. H. Seismic performance of an existing low-rise reinforced concrete piloti building retrofitted by steel rod damper. J. Earthq. Eng. Soc. Korea. 18, 241–251. 10.5000/EESK.2014.18.5.241 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim, J. Proposal of Shear Reinforcement Method for low Stories’ piloti Concrete Columns Using Engineering Plastic Panel (University of Seoul, 2021).

- 3.Shin, J., Lee, H., Min, J-K., Choi, I-R. & Choi, S-M. Predicting temperature loads in Open Car parks of Piloti structures exposed to Real Fire accidents. Int. J. Steel Struct.22, 1889–1907. 10.1007/s13296-022-00675-2 (2022b). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ko, D. W. & Lee, H. S. Shaking table tests on a high-rise RC building model having torsional eccentricity in soft lower storeys. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dynamics. 35, 1425–1451. 10.1002/eqe.590 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dang-Vu, H., Shin, J. & Lee, K. Seismic fragility assessment of columns in a piloti-type building retrofitted with additional shear walls. Sustainability. 12, 6530. 10.3390/su12166530 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grossi, E., Zerbin, M. & Aprile, A. Advanced techniques for pilotis RC frames seismic retrofit: performance comparison for a strategic building case study. Buildings. 10, 149. 10.3390/buildings10090149 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim, T., Park, J-H. & Yu, E. Seismic fragility of low-rise piloti buildings based on 2017 Pohang earthquake damage. J. Building Eng. 107032. 10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107032 (2023).

- 8.Kim, H. et al. A study on the analysis of pressure difference according to the stack effect of high-rise buildings during fire. J. Korean Soc. Hazard. Mitigation. 21, 161–168. 10.9798/KOSHAM.2021.21.1.161 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim, H-S., Oh, B-Y. & Park, M-Y. Fire spread in insulation materials in the ceiling of a piloti-type structure. Fire Sci. Eng.34, 18–26. 10.7731/KIFSE.78ac4f83 (2020a). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim, S-Y., Kim, K-N. & Yoon, T-H. Seismic performance of low-rise Piloti RC buildings with Eccentric Core. J. Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Soc.21, 490–498 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee, S-J. & Eom, T-S. Seismic design of columns and walls on weak first floor in Piloti-Type Bearing Wall buildings. ACI Struct. J. 117. 10.14359/51728066 (2020).

- 12.Karoubas, D. Review of Innovative Rehabilitation Techniques for Reinforced Concrete Buildings (West Virginia University, 2022).

- 13.Auman, H., Stratford, C. & Palermo, A. An overview of research and applications of FRP in New Zealand reinforced concrete structures. Struct. Eng. Int.30, 201–208. 10.1080/10168664.2019.1699491 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saghafi, M. H. & Golafshar, A. Seismic retrofit of deficient 3D RC beam–column joints using FRP and steel PT rods. Mater. Struct.55, 210. 10.1617/s11527-022-02046-z (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pohoryles, D. A., Melo, J., Rossetto, T., Varum, H. & Bisby, L. Seismic retrofit schemes with FRP for deficient RC beam-column joints: state-of-the-art review. J. Compos. Constr.23, 03119001. 10.1061/(ASCE)CC.1943-5614.0000950 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikramullah, A. A., Huzni, S., Thalib, S., Abdul Khalil, H. & Rizal, S. Effect of mesh sensitivity and cohesive properties on simulation of typha fiber/epoxy microbond test. Computation. 8, 2. 10.3390/computation8010002 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kodur, V., Bisby, L., Green, M. & Chowdhury, E. Fire endurance of insulated FRP-strengthened square concrete columns. ACI Struct. J.230, 1253–1268. 10.14359/14892 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elkady, H. Effect of high temperature on CFRP retroffitted columns, protected with different coatings. J. Struct. Fire Eng.1, 89–100. 10.1260/2040-2317.1.2.89 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bazli, M. & Abolfazli, M. Mechanical properties of fibre reinforced polymers under elevated temperatures: an overview. Polymers. 12, 2600. 10.3390/polym12112600 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li, Y., Liu, X. & Wu, M. Mechanical properties of FRP-strengthened concrete at elevated temperature. Constr. Build. Mater.134, 424–432. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.12.148 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng, G. et al. A review on mechanical properties and deterioration mechanisms of FRP bars under severe environmental and loading conditions. Cem. Concr. Compos. 104758. 10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2022.104758 (2022).

- 22.Bisby, L. A., Green, M. F. & Kodur, V. K. R. Modeling the behavior of fiber reinforced polymer-confined concrete columns exposed to fire. Journal of Composites for Construction. ;9:15–24. (2005). 10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0268(2005)9:1(15).

- 23.Cree, D., Chowdhury, E., Green, M., Bisby, L. & Bénichou, N. Performance in fire of FRP-strengthened and insulated reinforced concrete columns. Fire Saf. J.54, 86–95. 10.1016/j.firesaf.2012.08.006 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kodur, V., Bhatt, P. & Naser, M. High temperature properties of fiber reinforced polymers and fire insulation for fire resistance modeling of strengthened concrete structures. Compos. Part. B: Eng.175, 107104. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.107104 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhatt, P. P., Kodur, V. K., Shakya, A. M. & Alkhrdaji, T. Performance of insulated FRP-strengthened concrete flexural members under fire conditions. Front. Struct. Civil Eng.15, 177–193. 10.1007/s11709-021-0714-z (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chowdhury, E. U., Bisby, L. A., Green, M. F. & Kodur, V. K. Investigation of insulated FRP-wrapped reinforced concrete columns in fire. Fire Saf. J.42, 452–460. 10.1016/j.firesaf.2006.10.007 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Firmo, J. P., Correia, J. R. & Bisby, L. A. Fire behaviour of FRP-strengthened reinforced concrete structural elements: a state-of-the-art review. Compos. Part. B: Eng.80, 198–216. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2015.05.045 (2015b). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blontrock, H., Taerwe, L. & Vandevelde, P. July. Fire testing of concrete slabs strengthened with fibre composite laminates. FRPRCS-5: Fibre-reinforced plastics for reinforced concrete structures Volume 1: Proceedings of the fifth international conference on fibre-reinforced plastics for reinforced concrete structures, Cambridge, UK, 16–18 : Thomas Telford Publishing; 2001. pp. 547 – 56. (2001).

- 29.Williams, B., Bisby, L., Kodur, V., Green, M. & Chowdhury, E. Fire insulation schemes for FRP-strengthened concrete slabs. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manufac.37, 1151–1160. 10.1016/j.compositesa.2005.05.028 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stratford, T. J., Gillie, M., Chen, J. F. & Usmani, A. S. Bonded fibre reinforced Polymer strengthening in a real fire. Adv. Struct. Eng.12, 867–878. 10.1260/136943309790327743 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu, B. & Kodur, V. K. R. Fire behavior of concrete T-beams strengthened with near-surface mounted FRP reinforcement. Eng. Struct.10.1016/j.engstruct.2014.09.003 (2014b). 80:350 – 61.

- 32.Firmo, J. P., Correia, J. R. & França, P. Fire behaviour of reinforced concrete beams strengthened with CFRP laminates: Protection systems with insulation of the anchorage zones. Compos. Part. B: Eng.43, 1545–1556. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2011.09.002 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu, B. & Kodur, V. K. R. Effect of temperature on strength and stiffness properties of near-surface mounted FRP reinforcement. Compos. Part. B: Eng.58, 510–517. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2013.10.055 (2014a). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chowdhury, E., Eedson, R., Bisby, L. A., Green, M. F. & Benichou, N. Mechanical characterization of fibre reinforced polymers materials at high temperature. Fire Technol.47, 1063–1080. 10.1007/s10694-009-0116-6 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Firmo, J., Correia, J., Pitta, D., Tiago, C. & Arruda, M. Experimental characterization of the bond between externally bonded reinforcement (EBR) CFRP strips and concrete at elevated temperatures. Cem. Concr. Compos.60, 44–54. 10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2015.02.008 (2015a). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dai, J-G., Gao, W. & Teng, J. Bond-slip model for FRP laminates externally bonded to concrete at elevated temperature. J. Compos. Constr.17, 217–228. 10.1061/(ASCE)CC.1943-5614.0000337 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bisby, L. A., Kodur, V. K. R. & Green, M. F. Fire endurance of fiber-reinforced polymer-confined concrete. Aci Struct. J.102, 883–891. 10.14359/14797 (2005b). [Google Scholar]

- 38.ASTM. Standard Test Methods for Fire Tests of Building Construction and Material (ASTM E119) (American Society for Testing and Materials, 2022).

- 39.Kodur, V. K., Bisby, L. A. & Green, M. F. Experimental evaluation of the fire behaviour of insulated fibre-reinforced-polymer-strengthened reinforced concrete columns. Fire Saf. J.41, 547–557. 10.1016/j.firesaf.2006.05.004 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benichou, N., Cree, D., Chowdhury, E., Green, M. & Bisby, L. Fire testing of FRP strengthened reinforced concrete columns. International Conference on Durability and Sustainability of FRP Composites for Construction and Rehabilitation (CDCC 2011)2011. pp. 20 – 2.

- 41.Bisby, L. A., Kodur, V. K. R. & Green, M. F. Numerical parametric studies on the fire endurance of fibre-reinforced-polymer-confined concrete columns. Can. J. Civ. Eng.31, 1090–1100. 10.1139/l04-071 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi, I-R. High-temperature Thermal properties of Sprayed and Infill-Type Fire-resistant materials used in Steel-Tube columns. Int. J. Steel Struct.20, 777–787. 10.1007/s13296-020-00322-8 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 43.ACI. Guide for the Design and Construction of Externally Bonded FRP Systems for Strengthening Concrete Structures (ACI PRC-440.2-17) (American Concrete Institute, 2017).

- 44.Chandrasekaran, S., Hari, S. & Amirthalingam, M. Wire arc additive manufacturing of functionally graded material for marine risers. Mater. Sci. Engineering: A. 792, 139530. 10.1016/j.msea.2020.139530 (2020a). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chandrasekaran, S. & Pachaiappan, S. Numerical analysis and preliminary design of topside of an offshore platform using FGM and X52 steel under special loads. Innovative Infrastructure Solutions. 5, 1–14. 10.1007/s41062-020-00337-4 (2020b). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Noh, Y. A study on outer flashover mechanism in view of pilotis buildings fire. J. Korean Soc. Hazard. Mitigation. 19, 165–172. 10.9798/KOSHAM.2019.19.3.165 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shin, J. et al. Numerical Investigation of the Fire Performance of Piloti-Type RC Building Structures. The 23rd Japan-Korea-Taiwan Joint Seminar on Earthquake Engineering for Building Structures (SEEBUS 2022) (Nagoya Institute of Technology, 2022a).

- 48.MOLIT. Seismic Performance Evaluation Method for Existing Buildings (The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT), 2021).

- 49.Lam, L. & Teng, J. Design-oriented stress-strain model for FRP-confined concrete in rectangular columns. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos.22, 1149–1186. 10.1177/0731684403035429 (2003a). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lam, L. & Teng, J. G. Design-oriented stress–strain model for FRP-confined concrete. Construction and building materials. 2003b;17:471 – 89. 10.1016/S0950-0618(03)00045-X

- 51.ACI. Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete (ACI 318 – 19)-Commentary on Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete (ACI 318R-19) (Americal Concrete Institute, 2019).

- 52.European Committee For Standardization. EN January 1, 1992 - Eurocode 2: Design of Concrete Structures. Part 1–1: General Rules and Rules for Buildings (European Committee For Standardization, 2004).

- 53.Buchanan, A. H. & Abu, A. K. Structural Design for fire Safety (Wiley, 2017).

- 54.Dassault Systemes. Simulia User Assistance 2023-ABAQUS (Dassault Systemes, 2023).

- 55.Bisby, L. A. Fire Behaviour of fibre-reinforced Polymer (FRP) Reinforced or Confined Concrete (Queen’s University Kingston (Kanada), 2003).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Yu, B. & Kodur, V. K. R. Fire behavior of concrete T-beams strengthened with near-surface mounted FRP reinforcement. Eng. Struct.10.1016/j.engstruct.2014.09.003 (2014b). 80:350 – 61.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request by the first or corresponding author.