Abstract

The presence of residual undifferentiated pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) in PSC-derived cell therapy products (CTPs) is a major safety issue for their clinical application, due to the potential risk of PSC-derived tumor formation. An international multidisciplinary multisite study to evaluate a droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) approach to detect residual undifferentiated PSCs in PSC-derived CTPs was conducted as part of the Health and Environmental Sciences Institute Cell Therapy-TRAcking, Circulation & Safety Technical Committee. To evaluate the use of ddPCR in quantifying residual iPSCs in a cell sample, different quantities of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) were spiked into a background of iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (CMs) to mimic different concentrations of residual iPSCs. A one step reverse transcription ddPCR (RT-ddPCR) was performed to measure mRNA levels of several iPSC-specific markers and to evaluate the assay performance (precision, sensitivity, and specificity) between and within laboratories. The RT-ddPCR assay variability was initially assessed by measuring the same RNA samples across all participating facilities. Subsequently, each facility independently conducted the entire process, incorporating the spiking step, to discern the parameters influencing potential variability. Our results show that a RT-ddPCR assay targeting ESRG, LINC00678, and LIN28A genes offers a highly sensitive and robust detection of impurities of iPSC-derived CMs and that the main contribution to variability between laboratories is the iPSC-spiking procedure, and not the RT-ddPCR. The RT-ddPCR assay would be generally applicable for tumorigenicity evaluation of PSC-derived CTPs with appropriate marker genes suitable for each CTP.

Keywords: cell therapy, detection sensitivity, droplet digital PCR, multisite experiments, pluripotent stem cells, tumorigenicity, undifferentiation marker genes

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Significance statement.

The presence of residual undifferentiated pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) in cell therapy products (CTPs) poses a significant safety concern. To address this issue, a sensitive and broadly applicable method is essential for detecting and minimizing these cells in the final product. This is crucial for the translation of CTPs and advancements in regenerative medicine. Through an international multisite study across public and private settings, the droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) method was confirmed as highly sensitive and robust in detecting PSC impurities. This ddPCR approach contributes to enhancing safety and quality of PSC-derived CTPs as well as to efficient product development, incorporating new in vitro approaches, embracing the 3Rs principles.

Introduction

Pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), such as induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and embryonic stem cells (ESCs), have the ability to self-renew/proliferate and differentiate into various cell types. Thus, PSCs are considered promising sources for cell therapy products (CTPs) and PSC-derived CTPs are currently used for clinical applications all over the world.1 However, undifferentiated PSCs have the intrinsic capability of teratoma formation.2,3 Therefore, the presence of residual undifferentiated PSCs in PSC-derived CTPs is a major safety risk for transplantation into patients.4 Actually, preclinical tumorigenicity studies of human parthenogenetic stem cell-derived neural stem cells classified as PSC-derived CTPs were required by the US Food and Drug Administration and Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration prior to conducting a phase I clinical trial for treating Parkinson’s disease.5 To evaluate potential tumorigenic risks of PSC-derived CTPs, appropriate methods are crucial for measuring eventual PSCs remaining in the final CTP. Several assays are known to sensitively detect PSCs contained in CTPs in vitro6-9 as well as in vivo.10,11 Reverse transcription followed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) to measure mRNA levels of pluripotency marker genes is a useful in vitro method to detect undifferentiated PSCs in CTPs. RT-qPCR to quantify LIN28A gene has been reported to detect 0.002% iPSCs in retinal pigment epithelial cells without background signals with somatic cells.6 In addition to LIN28A gene, other marker genes have been proposed. Using RNA-seq analysis of iPSC-derived tissues, Lemmens et al have recently identified a panel of marker genes suitable for monitoring residual iPSCs in iPSC-derived products, showing a limit of detection (LOD) ranging from 0.001%-0.1% when RT-qPCR was used.12 To quantify gene expression, droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) has also been considered because ddPCR can offer greater precision and sensitivity than qPCR.13,14 Distinct from qPCR, ddPCR amplifies the target molecules in individual partitions of droplets, followed by the quantification of positive/negative droplets.15 Thus, ddPCR enables to directly and sensitively quantify DNA/mRNA copy numbers per reaction. Practically, ddPCR method targeting LIN28A gene has been reported to detect as low as 0.001% undifferentiated iPSCs spiked into primary cardiomyocytes.7 As a model of iPSC-derived CTPs, we selected cardiomyocytes in this multisite study. iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes are one of the most advanced CTPs for potential clinical use and now commercially available.16 Furthermore, it is presumed that ~109 cells need to be transplanted into a patient to treat heart failure,17 which requires highly sensitive assays to measure potential residual iPSCs in CTPs, and an assay method showing 0.001% LOD is estimated to detect impurities of 104 cells in 109 cells.

The testing methods used for evaluating the safety and quality of CTPs are expected to be commonly available, as this will contribute to the development of CTPs and quality control for manufacturing. In addition, assay performance via fit-for-purpose qualification parameters should be fully understood when applying it to the evaluation of CTPs. In particular, the variability among laboratories needs to be examined to confirm validity of the testing methods in multisite studies at the international level. The Health and Environmental Sciences Institute (HESI) Cell Therapy-TRAcking, Circulation & Safety (CT-TRACS) Technical Committee has launched an international project to evaluate 2 in vitro testing methods, the ddPCR assay and the Highly Efficient Culture assay, focusing on the detection of residual undifferentiated hPSCs, in collaboration with a Japanese experimental public–private partnership initiative (Multisite Evaluation Study on Analytical Methods for Non-clinical Safety Assessment of Human-Derived Regenerative Medical Products [MEASURE]).18

Here, we examined the performance of the ddPCR assay targeting PSC marker genes at multiple facilities using several doses of undifferentiated iPSCs in a background of iPSC-derived CTPs. The following parameters were considered—coefficient of determination, repeatability, reproducibility, specificity, and limit of detection. Conducting the study in 2 steps across multiple sites, we evaluated performance regarding both the ddPCR analytical process itself and the entire analytical process starting from the cell sample preparation step. In this work, we have estimated the variability of the experimental processes and thereby, investigated any potential source of variability.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participating facilities

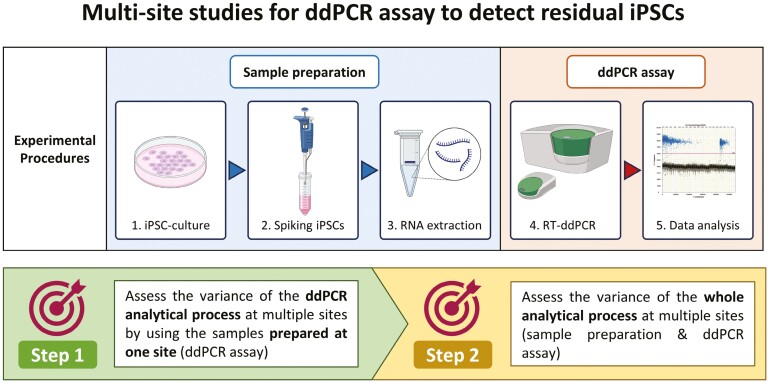

Based on the objective, this study was divided into 2 steps (Figure 1), where step 1 study aimed at assessing the variability of the ddPCR process alone, at 5 facilities by using the same RNA samples prepared at one site. Step 2 study examined the variability of the entire process at 3 facilities, when processes from preparation of spiked cells to ddPCR measurement were performed at each site. In step 1 study, ddPCR measurements using the same RNA samples were performed in technical triplicate and independently repeated 3 times excepting quality control failures. In step 2 study, the sample preparation (iPSC-culture, iPSC-spiking, and RNA extraction) was independently repeated 3 times and followed by ddPCR measurement in technical triplicate corresponding to each sample preparation. A selection of marker genes and dilutions were considered for step 2 study. To conduct ddPCR assay to detect undifferentiated iPSCs in CTPs for multisite validation, the study included 5 facilities: Cell and Gene Therapy Catapult, Novartis, National Institute of Health Sciences, Sumitomo Pharma, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals Company Limited.

Figure 1.

Overview of steps 1 and 2 studies. The study was divided into 2 steps, where step 1 study aimed at assessing the variability of the ddPCR process alone, at 5 facilities by using the same RNA samples prepared at one site. Step 2 study examined the variability of the entire process at 3 facilities, when processes from sample preparation to ddPCR measurement were performed at each site. The ddPCR assay in technical triplicate were performed with 3 independent runs excepting quality control failures in step 1 study, whereas both the sample preparation and ddPCR assay in technical triplicate were repeated 3 times in step 2 study. For step 2 study, a selection of marker genes and dilutions of spiking iPSCs were considered.

Cells and cell culture

Cellartis human iPS cell line 18 (ChiPSC18, Lot No. AF80011S) was obtained from Takara Bio. ChiPSC18 cells were maintained with the Cellartis DEF-CS Culture System (Takara Bio) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. When passaged, cells were detached by treatment with TrypLE Select and were re-seeded on culture dishes coated with DEF-CS COAT-1. To transfer cell vials, ChiPSC18 cells (passage 31, 3 × 106 cells/vial) were frozen in STEM-CELLBANKER (Zenogen Pharma) with a programmable freezer (PF-NP-200, NEPAGENE) at one facility and separately shipped to facilities performing spiking experiments with liquid nitrogen dry shippers. iCell Cardiomyocytes (C1106, Lot No. 103 700), which were cardiomyocytes derived from human iPSCs, were obtained from FUJIFILM Cellular Dynamics. Human iPSC line 201B7 was obtained from RIKEN Cell Bank. 201B7 cells were maintained on mitomycin C-treated SNL cells (a mouse fibroblast STO cell line expressing the neomycin-resistant gene cassette and LIF, CELL BIOLABS) in Primate ES Cell Medium supplemented with 4 ng/µL basic fibroblast growth factor (ReproCell) and were used at passage 29 for RNA isolation.

Spiking experiments

In step 1 study, spiking of ChiPSC18 cells into iCell Cardiomyocytes (iCell CM) was conducted at one facility. Cultured ChiPSC18 cells were dissociated into single cells with TrypLE Select at 37 °C for 5 min or until the cell layer had detached and suspended in DEF-CS supplemented with Cellartis DEF-CS Additives (GF1, 2, and 3; Takara Bio). Cells were counted with Countess II Automated Cell Counter (Thermo Fisher Scientific). ChiPSC18 cell suspension used for spiking was prepared by serial dilution from 5 × 105 cells/mL cells at a ratio of 10 or 33.3. The ChiPSC18 cell suspensions were added to the cell suspension of iCell CM (5.3 × 106 viable cells/vial) obtained from one vial to prepare mixtures containing 5300 (0.1%), 1590 (0.03%), 530 (0.01%), 159 (0.003%), 53 (0.001%), and 16 (0.0003%) ChiPSC18 cells. After centrifugation of the mixed cell suspension at 1500 × g for 5 minutes, the cell pellets were subjected to RNA isolation. Total RNA was isolated using RNeasy Fibrous Tissue Mini Kit with RNase-Free DNase Set (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Aliquots from the RNA samples were shared with 5 facilities for ddPCR analysis.

In step 2 study, spiking of ChiPSC18 cells into iCell CM was conducted at 3 facilities. One ChiPSC18 cell vial was thawed for each experiment, and the cells were used for spiking after 1 passage. Cryopreserved iCell CM was thawed with iCell Cardiomyocytes Plating Medium (FUJIFILM Cellular Dynamics) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were counted with Countess Automated Cell Counter (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or NucleoCounter NC-200 or -202 (ChemoMetec). The viability of hiPSCs at the 3 participating facilities was 95.1 ± 1.3%, 98.9 ± 0.5%, and 97.7 ± 0.3%, respectively, and that of iCell CM was 70.8 ± 2.3%, 85.8 ± 1.1%, and 74.8 ± 8.3%, respectively. As described in procedures of step 1 study, ChiPSC18 cell suspensions were added to the suspension of iCell CM from one vial to prepare mixtures at 0.01%, 0.003%, and 0.001%. The number of viable cells recovered from one iCell CM vial at the 3 participating facilities (n = 12 per facility) was 5.58 ± 0.50 × 106 cells, 4.87 ± 0.88 × 106 cells, 4.99 ± 0.33 × 106 cells, respectively. After centrifugation of the mixed cell suspension, the cell pellets were subjected to RNA isolation. Cell spiking and RNA isolation were repeated 3 times for ddPCR assay.

Specificity can be evaluated by analyzing the iCell CM spiked with undifferentiated iPS cells as impurities to compare with the assay results obtained on unspiked samples, according to ICH Q2.19

RNA quality control

Quantity of total RNA was determined using NanoDrop One (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RNA integrity was confirmed using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer with Agilent RNA 6000 Nano Kit (Agilent) or 4150 TapeStation System (Agilent). RNA Integrity Number20 of total RNA isolated from hiPSCs and iCell CM was confirmed to be ≥ 9.0.

Droplet digital PCR analysis

ddPCR assay was performed at 5 and 3 facilities in steps 1 and 2 studies, respectively. Custom probes labeled with 5´-FAM/3´-BHQ-1 and primers that target CNMD (chondromodulin), ESRG (embryonic stem cell related), LINC00678 (long intergenic non-protein-coding RNA 678), LIN28A (lin-28 homolog A), L1TD1 (LINE1 type transposase domain containing 1), VRTN (vertebrae development associated), and ZSCAN10 (zinc finger and SCAN domain containing 10) genes were obtained from Merck. The sequences of primers and probes used in the present study are listed in Supplementary Table S1. For manual droplet generation, 20 µL of reaction mixtures containing total RNA, 1 × Supermix, 20 U/µL reverse transcriptase, 250 nM probe, 900 nM forward and reverse primers, and 15 mM dithiothreitol were prepared with the One-Step RT-ddPCR Advanced Kit for Probes (Bio-Rad). Twenty microliters of the reaction mixtures and 70 μL of Droplet Generation Oil for Probes were loaded into DG8 cartridges, and droplets were generated using the QX100/QX200 droplet generator (Bio-Rad). The water-in-oil emulsions were transferred to a 96-well semi-skirted plate. For automated droplet generation, 22 µL of the reaction mixtures were prepared. Automated Droplet Generator (Bio-Rad) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Fifty nanograms of a total RNA sample per reaction were used for the reverse transcription (RT)-ddPCR. RT-ddPCR was performed using T100 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad), Veriti thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems), MyCycler thermal cycler (Bio-Rad), or C1000 Touch thermal cycler (Bio-Rad) across multiple sites. Thermal cycling conditions were as follows: reverse transcription at 50 °C for 60 minutes, followed by enzyme activation at 95 °C for 10 minutes, and 40 cycles of a thermal profile comprising denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s and annealing/extension at 58 °C for 60 s for detecting CNMD, ESRG, LINC00678, L1TD1, VRTN, and ZSCAN10 genes. For LIN28A gene, annealing/extension was performed at 65 °C for 60 s. After PCR amplification, products were denatured at 98 °C for 10 minutes and cooled at 4 °C. The fluorescence intensities of each droplet from the samples were measured using the QX100/QX200 droplet reader (Bio-Rad). Positive droplets containing amplification products were distinguished from negative droplets and counted by applying a fluorescence amplitude threshold in QuantaSoft software (Bio-Rad). Data from each assay/gene were plotted as histograms and the thresholds were manually calculated as the average between the mode of the amplitude of the negative and positive droplets. The ddPCR measurement of samples was performed in technical triplicate and repeated 3 times, except in cases of quality control failures (CNMD, LINC00678, and LIN28A were run only 2 times at one of the 5 facilities). To understand expression levels of the selected genes in target tissue, human heart total RNA was used as a reference material and purchased from Takara Bio (636532), Thermo Fisher Scientific (AM7966), and BioChain (R1234122-50). Total RNA isolated from ChiPSC18 cells (0.005, 0.015, 0.05, 0.015, and 0.5 ng RNA per reaction) was used as the positive control and standards for regression calculation.

Statistical analysis

The repeatability and reproducibility of the detected positive droplets (copy number/µL) of target genes was calculated with the mean values of technical triplicate measurements at each experiment, according to ISO 5725.21,22

Variability from a collaborative validation study can be modeled as

where is the reproducibility variance, is the between-laboratory variance, and is the repeatability variance.

The value of is calculated as

where p is the number of laboratories, ni is the number of test results in the ith laboratory, and si is the standard deviation of the test results in the ith laboratory.

The value of is calculated as

where

and is the mean of results in the ith laboratory.

To detect outliers, median absolute deviation (MAD) method was used with pooled data at all facilities in each target gene. If MAD equals 0, modified z-score was calculated from mean absolute deviation instead of MAD. Samples showing values with modified z-score of <−3.5 or >3.5 were excluded from the data analysis.23

For regression analysis with iPSC standards and iPSC-spiked iCell CM, power approximation (y = axb) was applied, and coefficient of determination (R2) was calculated using SigmaPlot 14.5 (HULINKS).

The copy numbers at overall facilities were compared among iPSC-spiked samples using Friedman repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) on ranks, followed by a post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls test using SigmaPlot 14.5. Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks and a post hoc Dunn’s method was used to compare mRNA expression between iCell CM and human heart total RNA from 3 providers (SigmaPlot 14.5). The copy numbers were compared between steps 1 and step 2 studies using 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA and a post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls test, following rank transformation for nonparametric factorial data analysis (SigmaPlot 14.5). A P-value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Marker genes selected for multisite studies of ddPCR assay

To have an efficient and sensitive assay detecting residual iPSCs in a CTP, a list of potential biomarkers needs to be assessed for their suitability. Previous reports have shown promising results using LIN28A7; however, further work has shown through the screening of multiple cell sources that no single marker can act universally for the characterization of different cell lineages.12,24 We selected CNMD, ESRG, LINC00678, LIN28A, L1TD1, VRTN, and ZSCAN10 genes, which have shown an LOD ranging from 0.001%-0.1% when measured, by qRT-PCR quantification, in iPSCs spiked into iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes.12

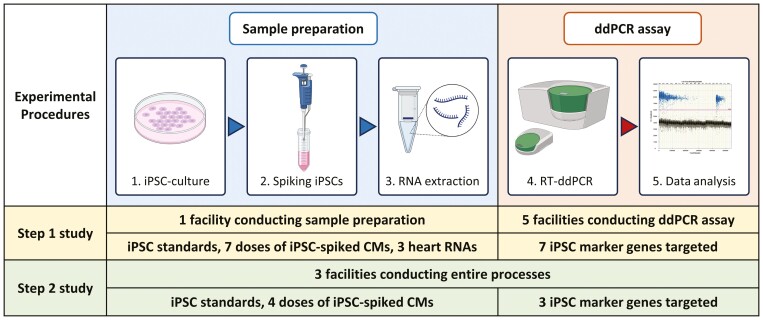

iPSC standard in step 1 study

Before performing the spike-in experiments, the performance of the ddPCR assay alone was evaluated for each target, at each facility. Serial dilutions of RNA extracted from a pure population of iPSCs, ranging from 0.005 ng to 0.5 ng per well, were used to measure by one-step RT-ddPCR the following genes: CNMD (Figure 2A), ESRG (Figure 2B), LINC00678 (Figure 2C), LIN28A (Figure 2D), L1TD1 (Figure 2E), VRTN (Figure 2F), and ZSCAN10 (Figure 2G). The regression analysis between input RNA and copy numbers was conducted for each marker gene and for each facility. All marker genes showed high coefficient of determination (R2) values in all facilities, indicating consistent correlation between copy number concentrations and RNA amount with power approximation. The obtained R2 values showed low coefficient of variation (CV), the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean, with overall R2 value being 0.9961, 0.9994, 0.9992, 0.9989, 0.9995, 0.9993, and 0.9947 in CNMD, ESRG, LINC00678, LIN28A, L1TD1, VRTN, and ZSCAN10, respectively, and each facility being over 0.99. CVs of overall facilities were <1%. This demonstrates operational range of ddPCR analysis across the facilities for all 7 tested marker genes. Representative 1D plots of ddPCR assay with probes and primers optimized at each gene are shown in Supplementary Figure S1.

Figure 2.

Standard curves using ddPCR assay targeting iPSC marker genes in step 1 study. Total RNA isolated from ChiPSC18 cells (0.005, 0.015, 0.05, 0.015, and 0.5 ng RNA per reaction) was used as the positive control and standards for regression calculation. Transcript expression of CNMD (A), ESRG (B), LINC00678 (C), LIN28A (D), L1TD1 (E), VRTN (F), and ZSCAN10 (G) was measured with the ddPCR method at 5 facilities. Mean and the coefficient of variation (CV) of mRNA copy numbers at overall facilities and coefficient of determination (R2) at each facility and overall facilities were indicated.

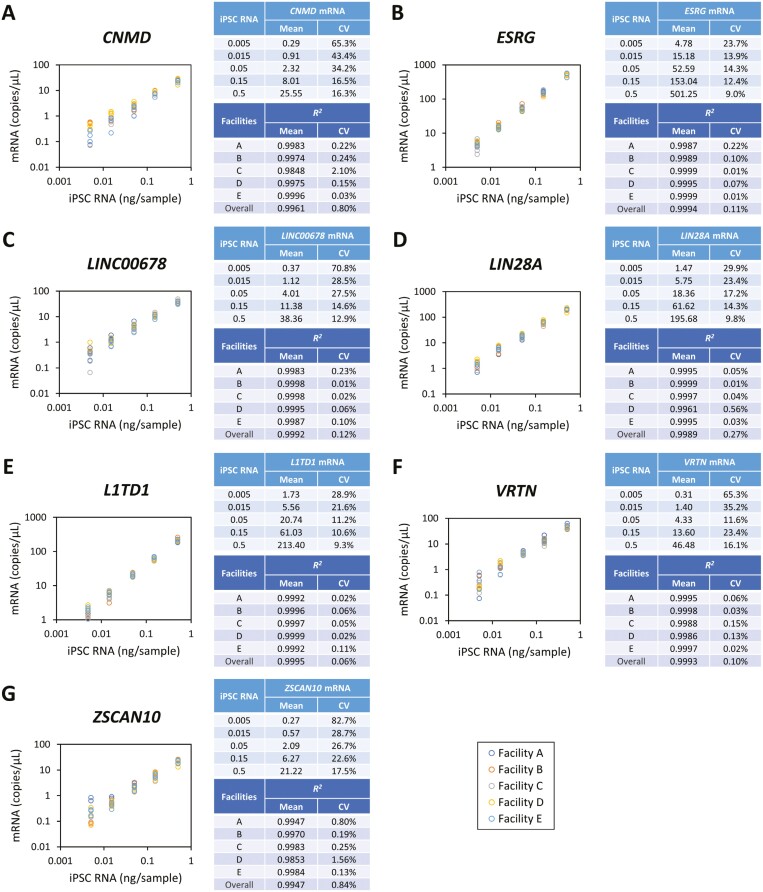

ddPCR assay in step 1 study

Dissociated undifferentiated iPSCs were spiked by one facility into 5.3 × 106 iCell CM at a final concentration ranging from 0.1%-0.0003%. RNA was isolated from each condition, equally distributed, and shipped among the 5 facilities and locally subjected to ddPCR assay targeting 7 marker genes (Figure 3). Total RNA from human heart obtained from 3 different providers was also used as controls to measure the endogenous expression of the target genes in somatic cardiomyocytes. The levels of expressed gene copies per microliter identified in the ddPCR across all of the markers exhibited a proportional shift alongside the serial dilution of iPSCs with most of the results exhibiting an overall R2 value >0.99, except VRTN, thus indicating a strong correlation of the gene expression levels of each marker and the concentration of iPSCs. Furthermore, the target concentration of detectable iPSCs spiked into a background of cardiomyocytes was set at a minimum of 0.001%, ie, 10 detectable iPSC cells in 1 × 106 cardiomyocyte cells (statistical significance of P < .05, relative to the base gene expression levels of 0% iPSCs), based on current technical development for the requirements for acceptable impurity assays.4 This detectable target concentration (0.001% of iPSC in cardiomyocytes) was achieved for all of the markers tested in our study with the exception of L1TD1 and VRTN (Figure 3). Furthermore, markers ESRG, LINC00678, and LIN28A exceeded this target and were more sensitive, with the ability to detect levels of 0.0003% iPSCs spiked in cardiomyocytes. Additionally, all of the no template control passed our acceptance criteria of no amplification. On the other hand, all references sourced from total heart RNA from 3 separate donors expressed levels of these genes that were lower than the expression levels in the cardiomyocytes without the iPSC (0% iPSCs), for markers LIN28A, L1TD1, and VRTN (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 3.

Copy numbers of iPSC marker genes investigated by ddPCR in step 1 study. ChiPSC18 cells were added to iCell CM (5.3 × 106 viable cells/vial) at 0.1%, 0.03%, 0.01%, 0.003%, 0.001%, and 0.0003% at one facility. Total RNA isolated from the cell mixtures was subjected to ddPCR assay targeting CNMD (A), ESRG (B), LINC00678 (C), LIN28A (D), L1TD1 (E), VRTN (F), and ZSCAN10 (G) with 3 lots of human heart RNA. ddPCR assay using the same samples was performed in technical triplicate with 3 independently repeated experiments at 5 facilities excepting quality control failures. Data represent means ± SD with 3 independently repeated experiments at each facility (left panel) and bars represent mean at overall facilities (right panel). Statistical difference between iPSC-spiked groups at overall facilities was indicated according to compact letter displays. Groups with the same letter are not detectably different, while groups that are detectably different have different letters. P < .05 is regarded as statistical significance. Coefficient of determination (R2) between copy numbers and iPSC doses at overall facilities were indicated.

CNMD: Copy number of CNMD proportionally changed at the upper doses of spiked iPSCs and reached plateau at the lower doses (R2 = 0.9954; Figure 3A). At least 0.001% spiking of iPSCs was statistically distinguished from iCell CM. The CNMD expression levels in human heart RNA ranged from 0.21 to 0.35 copies/µL indicated as the mean value at each provider.

ESRG: The iPSC-spiking experiments showed a high correlation between copy number and iPSC doses (R2 = 0.9997) and a proportional change of copy number with the doses (Figure 3B). Compared to iCell CM, iPSCs spiked at 0.0003% showed significant difference in copy number. However, ESRG expression levels were varied in human heart RNAs and ranged from 0.11 to 1.00 copies/µL.

LINC00678: LINC00678 showed a high correlation between copy number and iPSC doses (R2 = 0.9995). The copy number at 0.0003% spiking was significantly higher than that of iCell CM (Figure 3C). LINC00678 expression levels in human heart RNA varied from 0.04 to 0.25 copies/µL.

LIN28A: A high correlation between copy number of LIN28A and iPSC doses was observed (R2 = 0.9992; Figure 3D). Its transcript expression was significantly different among all doses of spiked iPSCs, suggesting that 0.0003% spiking was detectable. Positive signals with LIN28A gene in human heart RNA were negligible and almost not detected as background signals of somatic cells. A distinct difference in LIN28A mRNA expression was observed between iCell CM and 3 human heart RNA (Supplementary Table S2).

L1TD1: Copy number of L1TD1 changed depending on the number of spiked iPSCs but not so proportionally (R2 = 0.9939; Figure 3E). Therefore, iPSCs spiked at 0.01% were interpreted to be detectable. Copy number of L1TD1 in iCell CM was the most remarkable compared to those of other marker candidate genes beside VRTN, indicating high background signals in fully differentiated cells. L1TD1 mRNA levels in iCell CM were significantly high compared to those in 3 human heart RNA (Supplementary Table 2).

VRTN: No proportional change in copy number of VRTN was observed with the number of spiked iPSCs. Regression analysis also showed a weak correlation between copy number and iPSC doses in VRTN compared with the other genes (R2 = 0.8037; Figure 3F). VRTN mRNA expression in iCell CM was significantly higher than expression in 3 human heart RNA (Supplementary Table S2). Copy number in iCell CM appeared to be comparably high as L1TD1.

ZSCAN10: Copy number of ZSCAN10 proportionally changed with the number of spiked iPSCs (R2 = 0.9975; Figure 3G). The iCell CM was statistically distinct in copy number from 0.001% spiked iPSCs. ZSCAN10 expression in all human heart RNA was not statistically different from expression in the iCell CM and was similar to the levels of no template control (Supplementary Table S2).

Precision of ddPCR assay in step 1 study

According to formula described in ISO 572521,22 where the reproducibility variance is the sum of the repeatability variance (intra-laboratory variance) and between-laboratory variance, precision of the ddPCR assay was evaluated as methodology validation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Precision of ddPCR assay using the same RNA samples prepared from iPSC-spiked cardiomyocytes and human heart in step 1 study.

| Gene name | Precision indicators | Spiked iPSCs (%) | Human heart RNA | NTC | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.0003 | 0 | #1 | #2 | #3 | |||

| CNMD | General means (copies/µL) | 21.36 | 5.61 | 2.42 | 0.97 | 0.80 | 0.57 | 0.53 | 0.21 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.05 |

| Repeatability CV (%) | 8.4 | 10.5 | 14.6 | 24.7 | 31.0 | 35.8 | 37.8 | 43.9 | 37.2 | 43.2 | 139.3 | |

| Between-laboratory CV (%) | 8.6 | 13.0 | 10.3 | 18.1 | 5.8 | 0.0 | 14.0 | 0.0 | 10.3 | 21.0 | 77.4 | |

| Reproducibility CV (%) | 12.0 | 16.7 | 17.8 | 30.6 | 31.5 | 35.8 | 40.3 | 43.9 | 38.6 | 48.0 | 159.4 | |

| ESRG | General means (copies/µL) | 322.16 | 86.76 | 31.50 | 8.64 | 4.49 | 0.72 | 0.16 | 0.68 | 1.00 | 0.11 | 0.02 |

| Repeatability CV (%) | 3.8 | 6.7 | 6.8 | 9.6 | 10.8 | 29.1 | 35.1 | 31.6 | 29.7 | 34.5 | 324.6 | |

| Between-laboratory CV (%) | 1.8 | 6.4 | 8.1 | 7.5 | 9.3 | 37.4 | 70.4 | 41.5 | 43.9 | 89.5 | 0.0 | |

| Reproducibility CV (%) | 4.2 | 9.3 | 10.6 | 12.2 | 14.2 | 47.4 | 78.7 | 52.1 | 53.0 | 95.9 | 324.6 | |

| LINC00678 | General means (copies/µL) | 24.97 | 6.47 | 2.26 | 0.75 | 0.37 | 0.19 | 0.09 | 0.25 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| Repeatability CV (%) | 9.2 | 9.0 | 16.7 | 23.4 | 37.7 | 65.2 | 78.5 | 56.1 | 73.7 | 73.1 | 101.6 | |

| Between-laboratory CV (%) | 0.0 | 4.6 | 0.0 | 16.8 | 0.0 | 55.6 | 71.8 | 27.9 | 106.4 | 0.0 | 26.5 | |

| Reproducibility CV (%) | 9.2 | 10.1 | 16.7 | 28.8 | 37.7 | 85.7 | 106.4 | 62.7 | 129.4 | 73.1 | 105.0 | |

| LIN28A | General means (copies/µL) | 137.78 | 33.98 | 12.94 | 3.45 | 1.96 | 0.47 | 0.23 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Repeatability CV (%) | 11.5 | 9.4 | 12.9 | 11.0 | 29.4 | 18.6 | 26.6 | 156.4 | 200.1 | 155.2 | 187.9 | |

| Between-laboratory CV (%) | 9.7 | 14.9 | 0.0 | 10.2 | 4.4 | 15.6 | 0.0 | 80.6 | 178.0 | 172.5 | 138.0 | |

| Reproducibility CV (%) | 15.0 | 17.6 | 12.9 | 15.0 | 29.8 | 24.3 | 26.6 | 176.0 | 267.8 | 232.1 | 233.1 | |

| L1TD1 | General means (copies/µL) | 193.21 | 71.14 | 21.34 | 7.52 | 8.64 | 11.37 | 3.29 | 0.44 | 0.81 | 1.01 | 0.02 |

| Repeatability CV (%) | 1.8 | 6.9 | 7.3 | 10.9 | 6.5 | 7.0 | 10.4 | 17.6 | 25.2 | 20.3 | 208.3 | |

| Between-laboratory CV (%) | 2.1 | 0.0 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 6.0 | 9.9 | 8.6 | 18.1 | 0.0 | 6.9 | 111.4 | |

| Reproducibility CV (%) | 2.8 | 6.9 | 8.1 | 11.5 | 8.8 | 12.1 | 13.4 | 25.3 | 25.2 | 21.4 | 236.2 | |

| VRTN | General means (copies/µL) | 30.56 | 25.86 | 4.64 | 2.47 | 5.73 | 8.45 | 2.28 | 0.59 | 0.10 | 0.46 | 0.06 |

| Repeatability CV (%) | 5.3 | 11.1 | 16.6 | 14.8 | 16.8 | 14.5 | 20.4 | 274.7 | 104.7 | 305.3 | 119.7 | |

| Between-laboratory CV (%) | 5.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 15.9 | 13.7 | 0.0 | 9.1 | 10.7 | 19.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Reproducibility CV (%) | 7.5 | 11.1 | 16.6 | 21.7 | 21.7 | 14.5 | 22.3 | 274.9 | 106.6 | 305.3 | 119.7 | |

| ZSCAN10 | General means (copies/µL) | 14.36 | 3.57 | 1.55 | 0.47 | 0.36 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.09 |

| Repeatability CV (%) | 11.1 | 11.6 | 23.2 | 40.7 | 39.8 | 63.8 | 72.6 | 82.8 | 77.6 | 89.8 | 105.1 | |

| Between-laboratory CV (%) | 8.8 | 10.5 | 14.7 | 21.6 | 42.8 | 92.4 | 84.3 | 119.0 | 113.3 | 72.5 | 124.8 | |

| Reproducibility CV (%) | 14.2 | 15.7 | 27.5 | 46.1 | 58.4 | 112.3 | 111.2 | 145.0 | 137.3 | 115.4 | 163.2 | |

Abbreviations: NTC, no template control; CV, coefficient of variation.

CNMD: The number of spiked iPSCs affected repeatability and reproducibility, likely because reduction of positive signals in a small amount of spiked iPSCs increased variance of repeatability and reproducibility. Considering a CV of less than or equal to 30% as an indicator of good reproducibility,25,26 the reproducibility CV for spiked iPSCs at concentrations of 0.01% and higher were found to be acceptable.

ESRG: As the amount of spiked iPSCs decreased, all CV values of repeatability, between-laboratory and reproducibility gradually increased in a dose-dependent manner. The reproducibility CV was 14.2% at 0.001% spiked iPSCs, which was the smallest iPSC dose showing less than 30% of CV value in ESRG.

LINC00678: The CV values of repeatability and reproducibility increased with a decreasing number of spiked iPSCs but between-laboratory CV did not increase. This indicated that repeatability accounted for most of the reproducibility. The CV value of reproducibility at 0.003% spiked iPSCs was 28.8% in LINC00678.

LIN28A: The repeatability and reproducibility CV was relatively high at lower doses of spiked iPSCs, although dose-dependency of repeatability and reproducibility was not clearly observed. The CV values of reproducibility were <30% at all doses of spiked iPSCs, suggesting a reasonable multisite measurement of LIN28A at 0.0003% spiked iPSCs.

L1TD1: The CV values of reproducibility were <14% at all doses of spiked iPSCs and were mostly constant even though the number of spiked cells decreased. This indicated small variability of ddPCR assay at any dose of spiked iPSCs in L1TD1 although positive signals of iCell CM were not negligible as a background. Repeatability variance occupied most of repeatability variance, and between-laboratory CV was small.

VRTN: Similar to L1TD1, CV values of reproducibility in spiked iPSCs were low at any dose, and repeatability accounted for most of reproducibility. Positive signals in VRTN were detected even in iCell CM and would contribute to stable variability.

ZSCAN10: The CV value of reproducibility at 0.01% spiked iPSCs was 27.5%, thus less than 30%. A decrease in spiked iPSCs led to an enlargement of all CV values for repeatability and between-laboratory in a dose-dependent manner and resulted in an increase in the reproducibility CV.

Expression of marker genes in different iPSC lines

We confirmed the expression of 7 tested marker genes in 2 iPSC lines, ChiPSC18, and 201B7, using ddPCR assay (Supplementary Table S3). The difference in marker gene expression between the 2 iPSC lines ranged from 0.5- to 2-fold, excluding CNMD gene, even though these cells were distinct in donors, passage number, culture methods, and facilities for establishment. These results suggest that these differences only weakly influence the ddPCR signals when iPSC doses exceed the LOD using ESRG, LINC00678, LIN28A, L1TD1, VRTN, and ZSCAN10.

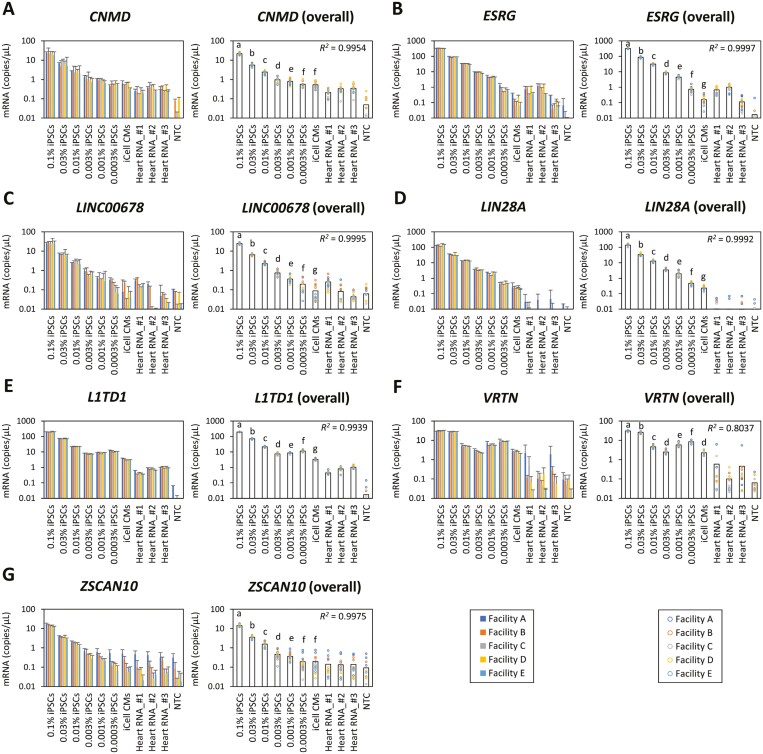

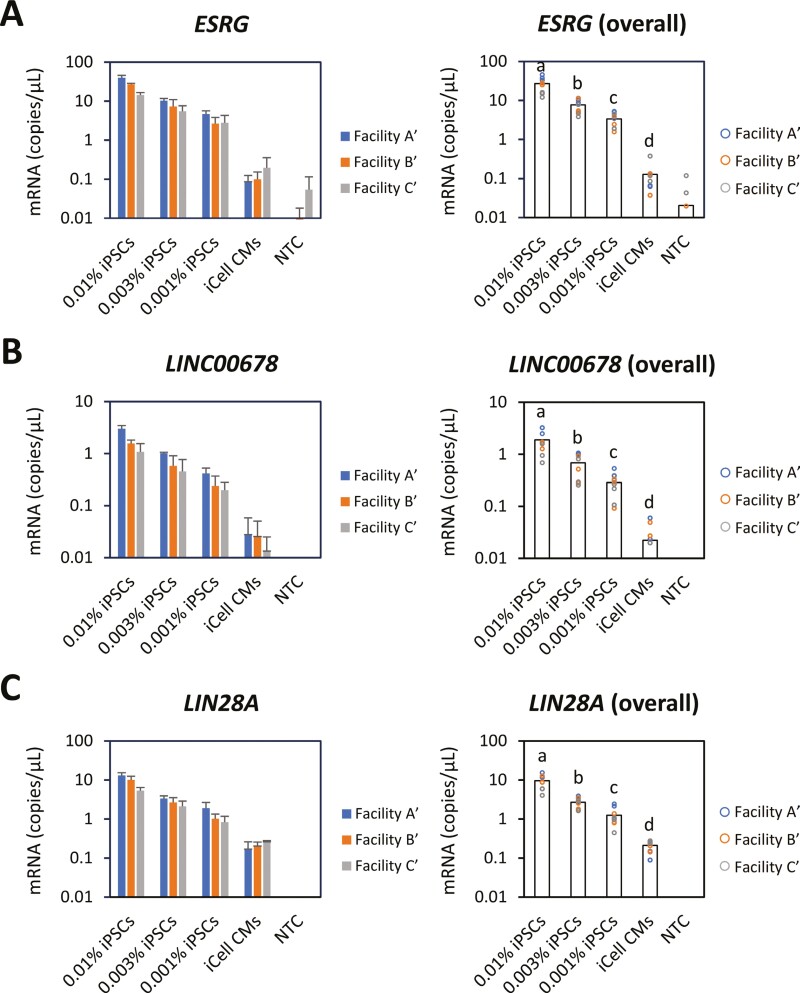

ddPCR assay in step 2 study

To shift from steps 1 to 2 studies, we selected 3 marker genes from the initial 7 candidates. The candidate marker genes evaluated in step 1 were scored 1-3 based on the following 8 parameters, with a maximum theoretical total score of 24: coefficient of determination with iPSC standards and with spiked-iPSCs, precision of spiked iPSCs, LOD, limit of quantification (LOQ), presence of signal in the background control (iCell CM), precision of iPSC standards, and target abundance (Table 2). Here, LOD and LOQ were calculated as mean + 3.3 SD and mean + 10 SD of copy number with iCell CM, respectively. As a result, ESRG, LIN28A, and LINC00678 were ranked as the top 3 marker genes and were chosen for further evaluation in step 2 study. To properly examine change of variability related to iPSC spiking, 3 concentrations were chosen, 0.0%1, 0.003%, and 0.001%, as doses of spiked iPSCs. Each of the 3 facilities completed entire procedures from sample preparation to ddPCR measurement.

Table 2.

Scoring candidate marker genes evaluated with ddPCR assay in step 1 study.

| CNMD | ESRG | LINC00678 | LIN28A | L1TD1 | VRTN | ZSCAN10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation with iPSC standards | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| Correlation with spiked iPSCs | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | + | ++ |

| Precision of spiked iPSCs | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| Limit of detection | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | + | ++ |

| Limit of quantification | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | + | ++ |

| Signals of iCell CM as the background control | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | + | +++ |

| Precision of positive control | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ |

| Target abundance | + | +++ | + | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| Overall score | 15 | 23 | 20 | 22 | 16 | 13 | 16 |

Correlation with iPSC standards (R2): +++, x > 0.999; ++, 0.990 < x ≤ 0.999; +, x ≤ 0.990.

Correlation with spiked iPSCs (R2): +++, x > 0.999; ++, 0.990 < x ≤ 0.999; +, x ≤ 0.990.

Precision of spiked iPSCs (the mean of overall CV): +++, x ≤ 15%; ++, 15% < x ≤ 30%; +, x > 30%.

Limit of detection: +++, x ≤ 0.5; ++, 0.5 < x ≤ 1; +, x > 1.

Limit of quantification: +++, x ≤ 1; ++, 1 < x ≤ 3; +, x > 3.

Signals of iCell CM as the background control: +++, x ≤ 0.25; ++, 0.25 < x ≤ 0.5; +, x > 0.5.

Precision of positive control (the mean of overall CV): +++, x ≤ 15%; ++, 15% < x ≤ 30%; +, x > 30%.

Target abundance (0.005 ng/sample of iPSCs): +++, x > 3; ++, 1 < x ≤ 3; +, x ≤ 1.

The regression analysis with copy number concentrations of iPSC standards was conducted with ESRG, LINC00678, and LIN28A (Supplementary Figure S2). R2 values showed high correlation between amount of iPSCs and copy number with these 3 marker genes and confirmed validity of ddPCR assay in step 2 study. Copy number of spiked iPSCs in ESRG (Figure 4A), LINC00678 (Figure 4B), and LIN28A (Figure 4C) changed in a dose-dependent manner and reflected amount of spiked iPSCs at all doses. The mRNA levels measured in step 2 study were significantly different from those measured in step 1 regarding LIN28A at 0.01%, 0.0.03%, and 0.001% iPSC-spiked groups (P < .05 at each dose) but not ESRG and LINC00678. R2 values with mean copy number of spiked iPSCs were 0.9986, 0.9997, and 0.9970 in ESRG, LINC00678, and LIN28A, respectively.

Figure 4.

Copy numbers of iPSC marker genes investigated by ddPCR in step 2 study. ChiPSC18 cells were once passaged and added to iCell CM (5.3 × 106 viable cells/vial) at 0.01%, 0.003%, and 0.001% with 3 independently repeated experiments at each facility. Total RNA isolated from the cell mixtures was subjected to ddPCR assay targeting ESRG (A), LINC00678 (B), and LIN28A (C). ddPCR assay using samples prepared at each facility was performed in technical triplicate with 3 independently repeated experiments corresponding to the spiking experiments at 3 facilities. Data represent means ± SD with 3 independently repeated experiments at each facility (left panel), and bars represent mean at overall facilities (right panel). Statistical difference between iPSC-spiked groups at overall facilities was indicated according to compact letter displays. Groups that are detectably different have different letters. P < .05 is regarded as statistical significance.

Precision of ddPCR assay in step 2 study

The repeatability and reproducibility (measured by % of coefficient of variance) in the step 2 study were consistently higher compared to step 1 study, mainly due to sample preparation procedures at individual study facilities (Table 3). Consistent with the step 1 study, the repeatability of spiked iPSCs in ESRG (Table 3A), LINC00678 (Table 3B), and LIN28A (Table 3C) tended to increase, as the positive signals of spiked iPSCs were impaired in samples from lower concentrations. On the other hand, the reproducibility of spiked iPSCs seemed to be relatively constant, independent of the concentration used. This was largely due to between-laboratory variation in step 2 study. These results suggest that differences between facilities in performing experiments induced large variation in procedures of iPSC-spiking.

Table 3.

Precision of the entire analytical process starting from the cell sample preparation with ddPCR assay in step 2 study.

| Gene name | Precision indicators | Spiked iPSCs (%) | NTC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0 | |||

| ESRG | General means (copies/µL) | 27.00 | 7.70 | 3.36 | 0.13 | 0.02 |

| Repeatability CV (%) | 15.1 | 32.7 | 37.1 | 78.7 | 175.4 | |

| Between-laboratory CV (%) | 45.4 | 24.9 | 25.5 | 11.3 | 105.1 | |

| Reproducibility CV (%) | 47.8 | 41.1 | 45.0 | 79.5 | 204.5 | |

| LINC00678 | General means (copies/µL) | 1.89 | 0.69 | 0.29 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| Repeatability CV (%) | 21.1 | 38.4 | 38.4 | 105.8 | NA | |

| Between-laboratory CV (%) | 51.7 | 37.2 | 34.4 | 0.0 | NA | |

| Reproducibility CV (%) | 55.9 | 53.5 | 51.6 | 105.8 | NA | |

| LIN28A | General means (copies/µL) | 9.56 | 2.70 | 1.25 | 0.21 | 0.00 |

| Repeatability CV (%) | 20.1 | 27.8 | 41.0 | 29.1 | NA | |

| Between-laboratory CV (%) | 39.7 | 16.9 | 38.9 | 14.4 | NA | |

| Reproducibility CV (%) | 44.5 | 32.5 | 56.6 | 32.5 | NA | |

NTC, no template control; CV, coefficient of variation; NA, not applicable.

Discussion

Here we have conducted an international multisite study to evaluate a ddPCR-based approach to detect undifferentiated iPSCs within iPSC-derived CMs, according to validation of analytical procedures described in ISO572521,22 and ICH Q2.19 In step 1 study, different amounts of iPSCs were spiked into iCell CMs by one site, and the expression of marker genes in the mixtures was measured at 5 facilities using aliquots of the same samples to examine precision, detection sensitivity and specificity of the ddPCR assay. iPSC standards showed strong correlation between spiked-iPSCs and copy number across the 100-fold range of amount of total RNA in all 7 marker genes. Human heart RNA was also measured as a reference sample to evaluate background signals in somatic cells. In step 2 study, the precision of the test method throughout the entire procedure, from cultured iPSC-spiking to ddPCR measurement, was confirmed with selected marker genes at 3 facilities. Our studies provide reference information on the testing methodology of ddPCR assay to evaluate iPSC impurities of CTPs, including a method for selecting PSC marker genes that are valid in assessing the quality of a particular PSC-derived CTP, taking into account the reproducibility of the test.

Marker gene selection

We measured transcript levels of 7 marker genes (CNMD, ESRG, LINC00678, LIN28A, L1TD1, VRTN, and ZSCAN10) in step 1 study and further selected 3 marker genes in step 2 study according to scoring of the initial 7 marker genes. ESRG, LINC00678, and LIN28A genes scored the highest, showing to be highly sensitive and robust for detection of impurities (ie, modeled with undifferentiated iPSCs, in this study) in iCell CMs in both steps 1 and 2 studies. These results positively support the use of a ddPCR based approach to monitor iPSC impurities in iPSC-derived products, as also other researchers have reported.27,28 However, it is worth mentioning that both steps of this multisite study were performed with only one lot of iCell CMs hence a batch effect cannot be completely excluded. In addition, since different kinetics in pluripotency marker genes decline have been reported during differentiation of human ESCs into cardiomyocytes,29 we propose that iPSC-derived CMs from different sources should be evaluated in future. Marker genes should be selected based on the final product cell type and timely monitored for each product manufacturing process. It is reported that markers suitable for detecting residual undifferentiated iPSCs in CTPs are different depending on embryonic cell lineage. LIN28A, ESRG and CNMD have showed basal expression in iPSC-derived nephron progenitor cells, and their expression has varied at different differentiation stages.24 To select marker genes, we note that the ddPCR assay may not distinguish undifferentiated PSCs from partially differentiated PSCs, depending on marker genes and types of CTPs. Multisite studies utilizing ddPCR assays with other PSC-derived cell types would be highly advised to further confirm the versatility of marker genes.

Setting a threshold in the ddPCR analysis

In ddPCR assay, determination of a correct threshold to separate positive from negative droplets should be discussed for a proper analysis.30 Two options, automatic and manual setting, are available to set a threshold with the QX100/200 Droplet Digital PCR system equipped with QuantaSoft software. Although automatic threshold setting would be preferred to analyze data in multisite validation study without bias, different populations of droplets may not be well separated, resulting in occurrence of false negative and positive droplets. On the other hand, with manual threshold setting, the operator can visually fine-tune the threshold, but differences in setting criteria may cause biases and inconsistencies between sites.15 To address this issue, a criterium to set threshold was agreed between sites. The threshold was manually set at the midpoint between negative and positive droplets, calculated as the average between the peak values of the positive and negative distribution as visualized by histogram. We verified the reliability of the applied method by comparing it with discriminant analysis.31 The discriminant analysis maximizes the ratio of between-class variance to within-class variance to determine a threshold. Notably, the 2 methods provided similar threshold values in the analysis using droplet fluorescence intensities (data not shown). Consistency with operation in data analysis can remove bias and would simplify factors that cause variability in ddPCR assay performed at multiple facilities.

LOD determination

For clinical application of iPSC-derived CTPs, the absolute number of undifferentiated iPSCs in CTPs could potentially contribute to tumor formation, and the number of residual iPSC could vary depending on the number of administered CTPs. As the gene expression is represented as copy number per sample volume according to the analytical property of ddPCR measurement, contents of iPSCs in iCell CM can be expressed as % but not the absolute number. In respect of the analytical methodology, cutoff level should be determined as LOD with signals of ddPCR using the same quantities of RNA background control, and % of spiked iPSCs exceeding LOD can be determined. Consequently, we are able to calculate the number of iPSC contaminated of CTPs based on the number of CTPs clinically used.

To evaluate sensitivity of a given methodology, LOD needs to be estimated with each product depending on the purpose of testing. We can propose 2 methods to determine LOD using iCell CM and 3 batches of human heart RNA to set as background control. According to the formula of mean + 3.3 SD of the background control, LOD were estimated with iCell CM (CNMD, 1.24; ESRG, 0.54; LINC00678, 0.39; LIN28A, 0.43; L1TD1, 4.71; VRTN, 3.94; ZSCAN10, 0.91 copies/µL) and with 3 batches of human heart RNA (CNMD, 0.55; ESRG, 2.08; LINC00678, 0.49; LIN28A, 0.01; L1TD1, 1.71; VRTN, 1.22; ZSCAN10, 0.15 copies/µL). iCell CM and human heart RNA have their own advantages and disadvantages to use as background control of ddPCR assay for determining LOD. iPSC-derived cells, such as iCell CM used in this study, can be routinely manufactured with the same iPSC line at large scale and are broadly available. Although, currently, some types of iPSC-derived cells, eg, iPSC-derived T cells, could be limitedly distributed, the ddPCR assay aims to target any cell therapy product derived from iPSCs. On the other hand, human heart RNA is derived from fully differentiated somatic cells and not impacted by contamination with iPSCs from a manufacturing process, but individual batches vary in quality and are limited in availability. Referring to data obtained in step 1 study, spiked iPSCs at 0.01% in CNMD, 0.001% in ESRG, 0.003% in LINC00678, 0.0003% in LIN28A, 0.0003% in L1TD1, 0.01% in VRTN and 0.01% in ZSCAN10 generally exceeded LOD estimated with both iCell CM and human heart RNA. The LOD, determined from the background control, serves as a critical criterion for identifying undifferentiated iPSC impurities in CTPs.

Variability of ddPCR assay

To obtain reliable results, it is crucial to have a comprehensive understanding of the precision of the used testing method. In step 1 study, when measuring by ddPCR the same RNA samples at 5 facilities, both the repeatability CV and reproducibility CV tended to increase as the number of spiked iPSCs decreased. According to the variability model for multisite validation, change of repeatability would mainly explain change of reproducibility, although dependency of between-laboratory variation on iPSC doses was observed with ESRG and ZSCAN10 genes. On the contrary, when iPSC-spiking and sample preparation were conducted at each laboratory in step 2 study, reproducibility CV was relatively constant, which was independent on the number of spiked iPSCs. Similar to the observation in step 1 study, repeatability CV increased as the number of spiked iPSCs decreased in step 2 study. As a result, change of repeatability only limitedly reflected the change of reproducibility, while the large between-laboratory variation in step 2 study compared to that in step 1 study significantly contributed to the variations in reproducibility. Variability of iPSC-spiking could cause a difference in copy number of LIN28A mRNA between step 1 and step 2 studies. The iPSC-spiking would induce large variability between facilities in the entire procedures of ddPCR assay for detecting undifferentiated PSCs contained in CTPs. Cell counting is thought to be another aspect accounting for errors in accurately determining the actual number of viable cells and possibly influences iPSC-spiking. In addition, technical skills of operators in handling cells may vary among laboratories and would require careful attention when testing methods evaluating the quality of CTPs. The between-laboratory variability of cell-spiking should be taken into consideration to determine LOD for evaluating PSC impurities of CTPs, especially when introducing the RT-ddPCR assay in in-house laboratories.

The risk-based approach is a general principle for regulation of pharmaceuticals and would be applied to decision making on the clinical use of CTPs.32 Impurities of CTPs with residual undifferentiated PSCs can be identified as a risk factor inherent to PSC-derived CTPs. Considering patient population, disease indication and intended dose of cells, acceptable levels of PSC contamination need to be determined compared to benefits from treatment with PSC-derived CTPs to patients under evaluation of risk-benefit balance.

Conclusion

Our international multisite studies have evaluated the performance of the ddPCR assay targeting PSC marker genes as a testing method to sensitively detect residual undifferentiated PSCs intermingled with iPSC-derived CMs. With respect to variability, specificity and sensitivity, ddPCR assay was confirmed to be a robust and reliable testing method to evaluate impurities from undifferentiated PSCs. Since the performance of the ddPCR assay largely depends on both the target genes and properties of CTPs, an initial screening test of the suggested markers genes needs to be performed on the individual specific CTP to assess suitability of the markers. However, the marker genes described here could be applicable to other PSC-derived CTPs when their versatility is confirmed. These studies provide a strong basis for use of the ddPCR assay for the assessment of critical quality attributes of CTPs. Once the method is standardized, it could become a powerful, highly sensitive and broadly applicable approach that would contribute to enhancing safety and quality of PSC-derived CTPs as well as to efficient product development.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Stem Cells Translational Medicine online.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the continuous support of the Health and Environmental Sciences Institute (HESI) Cell-Therapy—TRAcking, Circulation and Safety (CT-TRACS) Technical Committee and the Committee for Non-Clinical safety Evaluation of Pluripotent stem cell-derived product, the Forum for Innovative Regenerative Medicine (FIRM-CoNCEPT), and Ms Satoko Matsuyama for her expert technical support of the project. Graphical abstract and Figure 1 were created with BioRender.com.

Contributor Information

Satoshi Yasuda, Division of Cell-Based Therapeutic Products, National Institute of Health Sciences, Kawasaki, Japan.

Kiyoko Bando, Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd., Kobe, Japan.

Marianne P Henry, Cell and Gene Therapy Catapult, London, United Kingdom.

Silvana Libertini, Biomedical Research, Novartis, Basel, Switzerland.

Takeshi Watanabe, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, Fujisawa, Japan.

Hiroto Bando, Minaris Regenerative Medicine, Yokohama, Japan.

Connie Chen, Health and Environmental Sciences Institute, Washington, DC, United States.

Koki Fujimori, Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd., Kobe, Japan.

Kosuke Harada, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, Fujisawa, Japan.

Takuya Kuroda, Division of Cell-Based Therapeutic Products, National Institute of Health Sciences, Kawasaki, Japan.

Myriam Lemmens, Biomedical Research, Novartis, Basel, Switzerland.

Dragos Marginean, Cell and Gene Therapy Catapult, London, United Kingdom.

David Moss, Cell and Gene Therapy Catapult, London, United Kingdom.

Lucilia Pereira Mouriès, Health and Environmental Sciences Institute, Washington, DC, United States.

Nicole S Nicholas, Cell and Gene Therapy Catapult, London, United Kingdom.

Matthew J K Smart, Cell and Gene Therapy Catapult, London, United Kingdom.

Orie Terai, Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd., Kobe, Japan.

Yoji Sato, Division of Drugs, National Institute of Health Sciences, Kawasaki, Japan.

Author contributions

S.Y.: conception and design, financial support, collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript. K.B., M.P.H., S.L., T.W., M.L.: conception and design, collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript. H.B.: conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, final approval of manuscript. C.C.: project management; data analysis and interpretation, final approval of manuscript. K.F., K.H., T.K., O.T.: collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, final approval of manuscript. D.M., D.M., N.N., M.J.K.S.: data analysis and interpretation, final approval of manuscript. L.P.M.: conception and design, project management & coordination, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript. Y.S.: conception and design, financial support, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript.

Funding

This work was partly supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under grant number JP20mk0104176, JP20mk0104177, and JP22bk0104157, by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research 22KC5002, 23KC5002, and 24KC5001, and by the Health and Environmental Sciences Institute (HESI) Cell Therapy—TRAcking, Circulation, and Safety (CT-TRACS) Technical Committee. The Committee’s scientific work is primarily supported by the in-kind donation of time, expertise, and experimental efforts of its collaborators across academe, government, and industry.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no commercial, proprietary, or financial interest in the product or companies described in this article.

References

- 1. Ilic D, Ogilvie C.. Pluripotent stem cells in clinical setting-new developments and overview of current status. Stem Cells. 2022;40(9):791-801. 10.1093/stmcls/sxac040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hentze H, Soong PL, Wang ST, et al. Teratoma formation by human embryonic stem cells: evaluation of essential parameters for future safety studies. Stem Cell Res. 2009;2(3):198-210. 10.1016/j.scr.2009.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Damjanov I, Andrews PW.. Teratomas produced from human pluripotent stem cells xenografted into immunodeficient mice - a histopathology atlas. Int J Dev Biol. 2016;60(10-11-12):337-419. 10.1387/ijdb.160274id [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sato Y, Bando H, Di Piazza M, et al. Tumorigenicity assessment of cell therapy products: The need for global consensus and points to consider. Cytotherapy. 2019;21(11):1095-1111. 10.1016/j.jcyt.2019.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Garitaonandia I, Gonzalez R, Christiansen-Weber T, et al. Neural stem cell tumorigenicity and biodistribution assessment for phase I clinical trial in Parkinson’s disease. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34478. 10.1038/srep34478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kuroda T, Yasuda S, Kusakawa S, et al. Highly sensitive in vitro methods for detection of residual undifferentiated cells in retinal pigment epithelial cells derived from human iPS cells. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37342. 10.1371/journal.pone.0037342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kuroda T, Yasuda S, Matsuyama S, et al. Highly sensitive droplet digital PCR method for detection of residual undifferentiated cells in cardiomyocytes derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Regen Ther. 2015;2:17-23. 10.1016/j.reth.2015.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tano K, Yasuda S, Kuroda T, et al. A novel in vitro method for detecting undifferentiated human pluripotent stem cells as impurities in cell therapy products using a highly efficient culture system. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e110496. 10.1371/journal.pone.0110496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tateno H, Onuma Y, Ito Y, et al. A medium hyperglycosylated podocalyxin enables noninvasive and quantitative detection of tumorigenic human pluripotent stem cells. Sci Rep. 2014;4(4069):4069. 10.1038/srep04069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kanemura H, Go MJ, Shikamura M, et al. Tumorigenicity studies of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85336. 10.1371/journal.pone.0085336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yasuda S, Kusakawa S, Kuroda T, et al. Tumorigenicity-associated characteristics of human iPS cell lines. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0205022. 10.1371/journal.pone.0205022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lemmens M, Perner J, Potgeter L, et al. Identification of marker genes to monitor residual iPSCs in iPSC-derived products. Cytotherapy. 2023;25(1):59-67. 10.1016/j.jcyt.2022.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Taylor SC, Laperriere G, Germain H.. Droplet Digital PCR versus qPCR for gene expression analysis with low abundant targets: from variable nonsense to publication quality data. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):2409. 10.1038/s41598-017-02217-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu Y, Cathcart AL, Delaney WE 4th, Kitrinos KM.. Development of a digital droplet PCR assay to measure HBV DNA in patients receiving long-term TDF treatment. J Virol Methods. 2017;249:189-193. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2017.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huggett JF; dMIQE Group. The digital MIQE guidelines update: minimum information for publication of quantitative digital PCR experiments for 2020. Clin Chem. 2020;66(8):1012-1029. 10.1093/clinchem/hvaa125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deinsberger J, Reisinger D, Weber B.. Global trends in clinical trials involving pluripotent stem cells: a systematic multi-database analysis. NPJ Regen Med. 2020;5(15):15. 10.1038/s41536-020-00100-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tohyama S, Fukuda K.. Future treatment of heart failure using human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes. In: Nakanishi T, Markwald RR, Baldwin HS, Keller BB, Srivastava D, Yamagishi H, eds. Etiology and morphogenesis of congenital heart disease: from gene function and cellular interaction to morphology. Springer; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Watanabe T, Yasuda S, Chen CL, et al. International evaluation study of a highly efficient culture assay for detection of residual human pluripotent stem cells in cell therapies. Regen Med. 2023;18(3):219-227. 10.2217/rme-2022-0207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.International conference on harmonization (ICH) of technical requirements for registration of pharmaceuticals for human use, Topic Q2 (R2): validation of analytical procedures: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/ICH_Q2%28R2%29_Guideline_2023_1130.pdf

- 20. Schroeder A, Mueller O, Stocker S, et al. The RIN: an RNA integrity number for assigning integrity values to RNA measurements. BMC Mol Biol. 2006;7(3):3. 10.1186/1471-2199-7-3. https://bmcmolbiol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2199-7-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Accuracy (trueness and precision) of measurement methods and results - Part 2: Basic method for the determination of repeatability and reproducibility of a standard measurement method. ISO 5725-2:2019; 2019. https://www.iso.org/standard/69419.html [Google Scholar]

- 22. Luping T, Schouenborg B.. Methodology of inter-comparison tests and statistical analysis of the test results - Nordtest project No. 1483-1499. Accessed August 1, 2024. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:962159/FULLTEXT01.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 23. Iglewicz B, Hoaglin D.. The ASQC Basic References in Quality Control: Statistical Techniques. In: Mykytka EF, eds, How to Detect and Handle Outliers, Vol. 16. ASQC Quality Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tsujimoto H, Katagiri N, Ijiri Y, et al. In vitro methods to ensure absence of residual undifferentiated human induced pluripotent stem cells intermingled in induced nephron progenitor cells. PLoS One. 2022;17(11):e0275600. 10.1371/journal.pone.0275600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Busquet F, Strecker R, Rawlings JM, et al. OECD validation study to assess intra- and inter-laboratory reproducibility of the zebrafish embryo toxicity test for acute aquatic toxicity testing. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2014;69(3):496-511. 10.1016/j.yrtph.2014.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hayashi Y, Matsuda R, Maitani T, et al. Precision, limit of detection and range of quantitation in competitive ELISA. Anal Chem. 2004;76(5):1295-1301. 10.1021/ac0302859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Artyuhov AS, Dashinimaev EB, Mescheryakova NV, et al. Detection of small numbers of iPSCs in different heterogeneous cell mixtures with highly sensitive droplet digital PCR. Mol Biol Rep. 2019;46(6):6675-6683. 10.1007/s11033-019-05100-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yasui R, Matsui A, Sekine K, Okamoto S, Taniguchi H.. Highly Sensitive detection of human pluripotent stem cells by loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2022;18(8):2995-3007. 10.1007/s12015-022-10402-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tompkins JD, Jung M, Chen CY, et al. Mapping human pluripotent-to-cardiomyocyte differentiation: methylomes, transcriptomes, and exon DNA methylation “memories.”. EBioMedicine. 2016;4:74-85. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rutsaert S, Bosman K, Trypsteen W, Nijhuis M, Vandekerckhove L.. Digital PCR as a tool to measure HIV persistence. Retrovirology. 2018;15(1):16. 10.1186/s12977-018-0399-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Otsu N. A threshold selection method from gray-level histograms. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern. 1979;9(1):62-66. 10.1109/tsmc.1979.4310076 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hirai T, Yasuda S, Umezawa A, Sato Y.. Country-specific regulation and international standardization of cell-based therapeutic products derived from pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Rep., 2023;18(8):1573-1591. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2023.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.