Abstract

Objective

With the progress of economic globalization and food diversification, foodborne parasitic diseases pose a significant public health challenge in China. This study aimed to explore the knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding foodborne parasitic diseases among the Chinese population via WeChat, which is a promising tool for disease surveillance and health education.

Methods

Using a questionnaire, this cross-sectional study was conducted on September 25, 2023. Participants completed a structured questionnaire by scanning a QR code provided in a tweet from the WeChat official account of the Jiangsu Institute of Parasite Disease. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was employed to explore potential independent determinants of adequate knowledge of foodborne parasitic diseases, and the positive attitude and good practice rates of the participants were calculated.

Results

In total, 5,675 valid questionnaires were collected via the WeChat official account. Most participants (79.91%) fell within the age range of 20–40 years, with a higher representation of males (53.18%), and 89.80% were of Han Chinese ethnicity. It was found that 76.65% of the participants had adequate level of knowledge. Multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed that individuals of Hui nationality (OR = 0.57, 95% CI: 0.40–0.81, p = 0.002), clinicians (OR = 0.13, 95% CI: 0.09–0.19, p < 0.001), teachers (OR = 0.48, 95% CI: 0.34–0.69, p < 0.001), and government staff (OR = 0.40, 95% CI: 0.30–0.53, p < 0.001) had significantly higher levels of knowledge. Among the participants, 33.9% reported consuming raw fish or drunken shrimp, 10.6% would still try to consume raw fish despite the risk of parasitic infection, and 84.1% did not use separate cutting boards for raw and cooked foods in their kitchens.

Conclusions

Although majority of the Chinese public (76.65%) demonstrates adequate level of knowledge on foodborne parasitic diseases, there is a need to enhance personal hygiene practices and dietary habits, particularly the utilization of distinct cutting boards and the consumption of raw fish. A WeChat official account is an accessible tool for spreading foodborne parasitic diseases related health information to the public. WeChat-based health education should be implemented to enhance public awareness regarding the prevention and control of foodborne parasitic diseases.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-024-20279-1.

Keywords: Foodborne parasitic diseases; Knowledge, attitudes, and practices; Questionnaire; WeChat official account; China

Introduction

Foodborne parasitic diseases are caused by the ingestion of raw fish, crustaceans, vegetables, or water contaminated with parasitic larvae. This category encompasses a variety of conditions such as clonorchiasis, fascioliasis, paragonimiasis, toxoplasmosis, cysticercosis, giardiasis, and cryptosporidiosis, among others [1]. Foodborne parasitic diseases are prevalent worldwide, particularly in East Asia and South America, and have been classified as neglected tropical diseases by the World Health Organization (WHO) [2]. Unlike deadly diseases such as malaria, foodborne parasitic diseases mainly cause serious illness but not death. The WHO has highlighted the global disease burden associated with 11 foodborne parasitic diseases, which have caused more than 407 million illnesses, approximately 94,000 deaths, and 11 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) [3]. Nevertheless, parasites remain overlooked compared with bacterial and viral foodborne pathogens.

China was once the country with the highest prevalence of parasitic diseases, and foodborne parasitic diseases remain a significant public health concern because of their widespread occurrence and challenging diagnosis. Additionally, certain parasitic infections can promote tumorigenesis through immunosuppression [4]. A recent study on foodborne parasitic diseases in China revealed a prevalence of 1,500 cases per 100,000 individuals, resulting in an estimated 643,000 DALYs [5]. The increasing prevalence of foodborne parasitic diseases has been attributed to shifting dietary patterns, greater population mobility, globalization of food sources, and increased consumption of fresh produce in both developed and developing nations [6]. Health education plays a vital role in the prevention and control of foodborne parasitic diseases [7]. With the advent of the Internet, platforms, such as WeChat, have emerged as accessible mediums for sharing health information, significantly contributing to the acquisition of public health knowledge [8, 9]. Previous studies have examined the knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) regarding foodborne parasitic diseases in specific Chinese populations, including middle school [10], senior high school [11], and college students [12]. However, there is currently no application of WeChat in the health education of foodborne parasitic diseases among the general Chinese population.

We aimed to investigate the knowledge level, attitudes, hygiene practices, and dietary habits of the Chinese public to explore the KAP and influencing factors of foodborne parasitic diseases based on WeChat official account, which could provide a reference for future surveillance and prevention of foodborne parasitic diseases.

Methods

WeChat official account

The WeChat official account, Parasitic Disease Control and Prevention in Jiangsu, was used in this study. It represents the official account of the Jiangsu Institute of Parasite Disease (JIPD). The account was created in 2016 with the primary aim of sharing health-related information on parasitic diseases and providing public health services to residents. Subscribers of the WeChat official account have access to regularly updated tweets on parasitic diseases (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The interface of the WeChat-based questionnaire survey. Note: a, frontpage of the WeChat official account of JIPD; b, the tweet sent to subscribers of the WeChat official account on September 25, 2023; c and d, entry to the questionnaire through scanning QR code; e, questionnaire interface

Study design and implementation

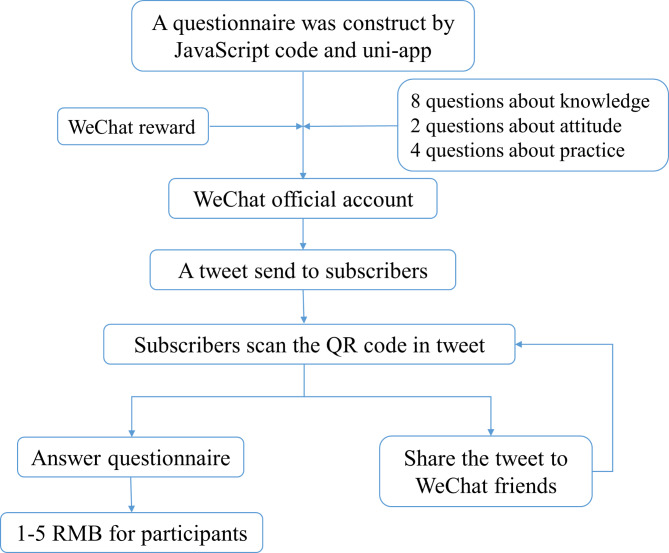

This study adopted a cross-sectional design using the WeChat official account (Parasitic Disease Control and Prevention in Jiangsu). JavaScript code and uni-app were used to construct the questionnaire for data collection.

The questionnaire, titled “Prize quizzes on foodborne parasitic diseases”, encompassed four main components: demographic characteristics (including age, gender, ethnicity, education, and occupation) and KAP related to foodborne parasitic diseases (see Additional file 1). The questionnaire was presented in Chinese and used a closed-ended format to minimize potential misinterpretations of the participants’ replies. A tweet was sent to subscribers of the JIPD WeChat official account on September 25, 2023. Interested subscribers could engage in the survey by scanning the QR code provided in the tweet (Fig. 1). Additionally, the tweet could be retweeted or shared on their WeChat moments to promote the survey. To incentivize timely completion of the questionnaire, a small WeChat reward ranging between 1 and 5 RMB was randomly allocated to the respondents. This reward significantly boosted the participants’ engagement, akin to a gamification strategy. The flow diagram for participation in the questionnaire is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Flow diagram for participating in the WeChat-based questionnaire survey

Data analysis

The exclusion criteria for invalid questionnaires include logical contradictions within the responses provided by the same respondent, such as a mismatch between educational background and occupation, or both the response time and content were identical across different respondents, indicating potential automated batch response activity.

The knowledge segment comprised eight questions, correct responses were scored as 1 and incorrect responses as 0. These scores were aggregated to generate a cumulative knowledge score that varied between 0 and 8. We used Bloom’s cut-off point of 60% to determine an adequate level of knowledge [13]. Specifically, participants who achieved a total knowledge score exceeding 4.8 were considered to have passed the knowledge section and were deemed to possess adequate knowledge.

Graphs were plotted to visualize the responses to the KAP using Microsoft Excel 2016. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 18.0) was used for statistical analysis. Categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages (n%) and were compared using the chi-square test. Multivariate logistic regression was used to explore the potential independent determinants of adequate knowledge of foodborne parasitic diseases, and odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated. Categorical variables were converted into dummy variables. A p values < 0.05 indicated statistically significant differences.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of JIPD. Informed consent to participate was obtained from all of the participants. Note that the use of data was presented at the beginning of the questionnaire, and their privacy and confidentiality were scrupulously maintained at all times.

Results

Basic characteristics of the participants

The survey was conducted over a single day, and all questionnaires were completed on September 25, 2023, coinciding with the distribution of the award. In total, 5,675 valid questionnaires were submitted via smartphones. Most participants (79.91%) were within the age range of 20–40 years, with male predominance (53.18%), and most respondents (89.80%) were of Han Chinese ethnicity. Moreover, 84.23% had attained a university-level education or higher. An analysis of occupational backgrounds revealed that the largest group consisted of workers (35.75%), followed by government staff (22.40%), clinicians (17.30%), and students (11.15%). These findings suggest a diverse range of occupational profiles among participants. The participants’ basic characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Adequate knowledge rate in the study participants

| Variables | No. participated (%) | No. adequate (%) | Adequate rate/% | χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 3018 (53.18) | 2276 (52.32) | 75.41 | 5.52 | 0.019* |

| Female | 2657 (46.82) | 2074 (47.68) | 78.06 | ||

| Age | |||||

| < 20 y | 457 (8.05) | 262 (6.02) | 55.16 | 103.68 | < 0.001* |

| 20–40 y | 4535 (79.91) | 3553 (81.68) | 78.35 | ||

| > 40 y | 683 (12.04) | 535 (12.30) | 78.33 | ||

| Ethnics | |||||

| Han | 5096 (89.80) | 3888 (89.38) | 76.30 | 10.94 | 0.012* |

| Hui | 250 (4.41) | 211 (4.85) | 84.40 | ||

| Miao | 146 (2.57) | 117 (2.69) | 80.14 | ||

| Others | 183 (3.22) | 134 (3.08) | 73.22 | ||

| Education level | |||||

| Primary and Junior high school | 300 (5.29) | 199 (4.58) | 66.33 | 45.78 | < 0.001* |

| Senior high school or technical secondary school | 595 (10.48) | 409 (9.40) | 68.74 | ||

| University and above (including Junior college) | 4780 (84.23) | 3742 (86.02) | 78.28 | ||

| Occupation | |||||

| Farmer | 633 (11.15) | 375 (8.62) | 59.24 | 337.93 | < 0.001* |

| Student | 155 (2.73) | 91 (2.09) | 58.71 | ||

| Worker | 2029 (35.75) | 1498 (34.44) | 73.83 | ||

| Teacher | 351 (6.19) | 277 (6.37) | 78.92 | ||

| Clinician | 982 (17.30) | 914 (21.01) | 93.08 | ||

| Government staff | 1271 (22.40) | 1036 (23.82) | 81.51 | ||

| Others | 254 (4.48) | 159 (3.66) | 62.60 |

Data were analyzed using Pearson’s chi-square

*Significant difference

Knowledge level in foodborne parasitic diseases

The cumulative knowledge scores of the participants regarding foodborne parasitic diseases were calculated. In total, 4,350 participants who achieved a cumulative knowledge score of 4.8 or higher were considered to possess adequate knowledge. The adequate knowledge rate ranged from 55.16 to 93.08%. Table 1 shows that gender, age, ethnicity, education, and occupation were significantly associated with adequate knowledge (all p < 0.05) from the univariate analyses.

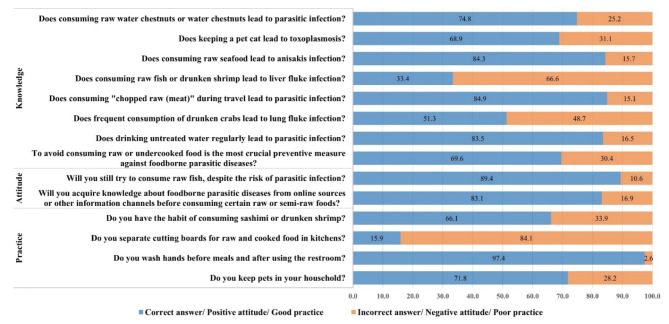

Most participants (74.8%) demonstrated awareness of the potential parasitic infection risks associated with consuming raw cane shoots or water chestnuts, whereas a slightly lower percentage (68.7%) correctly identified that keeping a pet cat could lead to toxoplasmosis. Of the participants, 84.3% recognized the risk of anisakis infection from consuming raw seafood. However, only 33.4% were aware of the potential risk of liver fluke infections from consuming sashimi or drunken shrimp. Conversely, 84.9% correctly identified that consuming “chopped raw (meat)” while traveling could lead to parasitic infection. More than half of the respondents (51.3%) were knowledgeable about the potential infection risk associated with the frequent consumption of drunken crabs, which may lead to lung fluke infection. Furthermore, a substantial majority (83.5%) was aware of the risk of parasitic infection from regularly drinking untreated water. Of the participants, 69.6% concurred that the most crucial preventive measure against foodborne parasitic diseases is to avoid consuming raw or undercooked food (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Responses to KAP questions toward foodborne parasitic diseases among study participants

Independent determinants of adequate knowledge

Variables with a univariate p-value below 0.05 were further analyzed using multivariable logistic regression to identify independent determinants of adequate knowledge. The results indicated significant differences in adequate knowledge among participants of diverse ethnicities and occupations (both p < 0.05). Compared to the Han ethnicity, the Hui nationality demonstrated a significantly higher level of knowledge (OR = 0.57, 95% CI: 0.40–0.81, p = 0.002). In comparison to farmers, clinicians exhibited the highest adequate knowledge rate concerning foodborne parasitic diseases (OR = 0.13, 95% CI: 0.09–0.19, p < 0.001). Furthermore, teachers (OR = 0.48, 95% CI: 0.34–0.69, p < 0.001) and government staff (OR = 0.40, 95% CI: 0.30–0.53, p < 0.001) also demonstrated significant levels of knowledge (Table 2).

Table 2.

Independent determinants associated with adequate knowledge in the study participants

| Variables | B | SE | Wald | p-value | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper | Lower | ||||||

| Gender (ref = Male) | |||||||

| Female | -0.03 | 0.07 | 0.20 | 0.65 | 0.97 | 0.85 | 1.11 |

| Age group (ref = < 20 y) | |||||||

| 20–40 y | -0.28 | 0.15 | 3.59 | 0.06 | 0.75 | 0.56 | 1.01 |

| > 40 y | -0.26 | 0.18 | 2.08 | 0.15 | 0.77 | 0.55 | 1.10 |

| Ethnics (ref = Han) | |||||||

| Hui | -0.56 | 0.18 | 9.57 | 0.002* | 0.57 | 0.40 | 0.81 |

| Miao | -0.26 | 0.22 | 1.45 | 0.23 | 0.77 | 0.50 | 1.18 |

| Others | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.02 | 0.89 | 1.02 | 0.73 | 1.45 |

| Education level (ref = Primary and Junior high school) | |||||||

| Senior high school or technical secondary school | 0.20 | 0.20 | 1.00 | 0.32 | 1.22 | 0.83 | 1.80 |

| University and above (including Junior college) | 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.56 | 0.45 | 1.15 | 0.80 | 1.66 |

| Occupation (ref = Farmer) | |||||||

| Student | 0.38 | 0.27 | 1.89 | 0.17 | 1.46 | 0.85 | 2.50 |

| Worker | -0.47 | 0.14 | 11.80 | 0.001* | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0.82 |

| Teacher | -0.73 | 0.18 | 16.15 | < 0.001* | 0.48 | 0.34 | 0.69 |

| Clinician | -2.03 | 0.18 | 129.58 | < 0.001* | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.19 |

| Government staff | -0.92 | 0.14 | 40.35 | < 0.001* | 0.40 | 0.30 | 0.53 |

| Others | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.02 | 0.89 | 1.03 | 0.72 | 1.47 |

*Significant difference

Attitude and practice

Regarding participants’ attitudes toward foodborne parasitic diseases, 10.6% indicated a willingness to consume raw fish despite being aware of the potential risk of parasitic infection. Conversely, a significant majority of participants (83.1%) expressed a preference for acquiring knowledge about foodborne parasitic diseases from online sources or other information channels prior to consuming certain raw or semi-raw foods.

In practice, nearly one-third (33.9%) of the participants had the habit of consuming sashimi or drunken shrimp. Notably, a significant majority of participants (84.1%) did not separate cutting boards for raw and cooked food preparation in their household kitchens. Most of the participants (97.4%) wash their hands before meals and after the restroom. Furthermore, 28.2% of the participants reported owning pets in their household (Fig. 3).

Discussion

This study explored a new method for assessing KAP using questionnaires distributed via social media, with incentives for participation in China. Among the participants, 76.65% were found to have adequate level of knowledge.

Notably, individuals of Hui nationality exhibited significantly higher knowledge scores than those in other ethnic groups. The Hui people, an ethnic minority in China, adhere to dietary practices that are influenced by Islamic religious regulations. In Islamic dietary law, adherence to halal guidelines is compulsory, designating certain foods as permissible (“Halal”) for consumption while categorizing those that do not meet these requirements as impure or unclean [14, 15]. The dietary prohibition against raw food consumption among the Hui people is rooted in their religious beliefs and cultural customs, providing them with increased exposure to and an understanding of foodborne parasitic diseases. Among the Hui people, 21.2% consumed raw fish or drunken shrimp. The proportion of individuals consuming raw food is lower than that of the general population. In addition, individuals working in the medical, educational, and governmental sectors exhibited notably greater levels of awareness about foodborne parasitic diseases than students, farmers, workers, and others. This disparity may be attributed to the higher educational background of teacher, clinician and government staff, leading to more exposure to information on foodborne parasites through information campaigns and educational programs [16, 17].

Among the participants in the present study, nearly one-third consumed raw fish or drunken shrimp. Additionally, over one-tenth of the participants expressed a willingness to continue consuming raw fish despite the potential risk of parasitic infection. Although people were aware of the dangers of parasite infections, they still sought to satisfy their cravings for delicious food, often harboring a fluke mentality that they could avoid such infections. Notably, most participants did not separate cutting boards for raw and cooked food in their kitchens. People with only one cutting board should be publicized that they can prevent parasite infections by thoroughly cleaning the board with boiling water either before or after use. These findings revealed a limited adoption of healthy practices, underscoring the need for enhanced health education initiatives targeting foodborne parasitic diseases.

Addressing these concerns requires focused educational initiatives. This involves the establishment of diverse educational programs within schools to raise awareness about the risks and implications of foodborne parasitic diseases among students across different academic levels [18, 19]. Additionally, activities such as lectures [20], broadcasts, and cultural events centered on foodborne parasitic diseases can be organized in various settings including communities [21], rural areas [22], and factories. Utilizing a range of media, such as leaflets, posters, and shopping bags [23], can further enhance the public’s understanding of foodborne parasitic diseases. Besides, several key strategies such as “proper food handling”, “cooking to safety temperatures”, “avoiding raw or undercooked food”, “safe water use” and “separation of raw and cooked foods” should be popularized to promote good practices toward foodborne parasitic diseases.

However, in certain instances, the impact of health education through traditional media on enhancing public health literacy has been found to be limited [24]. Compared with traditional media, new media offer advantages such as fast speed, low cost, diverse content, and strong interactivity. WeChat allows users to create official accounts to share content, engage with others, and offer services to their subscribers. These official accounts allow subscribers to access and exchange messages with others [25], which have been utilized to disseminate public health information and have had a significant impact on raising public awareness about conditions such as diabetes [26], malaria [27], and cancer [28]. Subsequently, health education on foodborne parasites should be disseminated to specific demographics through our WeChat official account. Moreover, online and offline informational campaigns [29] and educational interventions should be implemented to enhance public awareness of the prevention and control of foodborne parasitic diseases.

This study has several limitations. First, it was WeChat-based, which may have led to a participant pool without older people or children, potentially not representing the entire population. Older people are generally not good at using smartphones due to eye degeneration while parents typically limit their children’s smartphone usage to prevent potential impacts on vision and academic performance. Alternative approaches should be explored for individuals who do not use WeChat. Second, the sections on attitudes and practices had a limited number of questions, resulting in a lack of a thorough assessment in these areas. Finally, given the study’s cross-sectional design, which only allows for inferential interpretation rather than causation, the results should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusion

While majority of the Chinese population demonstrates adequate level of knowledge on these diseases, it needs to enhance personal hygiene practices and dietary habits, particularly the utilization of distinct cutting boards and the consumption of raw fish. Health education should be implemented to enhance public awareness of foodborne parasitic diseases. Our findings provide a reference for future WeChat-based surveillance and prevention of foodborne parasitic diseases.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- KAP

Knowledge attitudes and practices

- JIPD

Jiangsu Institute of Parasite Disease

- WHO

World Health Organization

- DALYs

Disability-adjusted life years

- ORs

Odds ratios

- CIs

: Confidence intervals

Author contributions

BN designed the study, wrote the protocol, conducted data gathering, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. QZ helped design the questionnaire and edited the WeChat official tweet. FT and JZ supervised the data collection and analysis procedures. YL and FM supervised data processing and provided guidance and comments on the analysis and initial drafts of this manuscript. All the authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Jiangsu Province Capability Improvement Project through Science, Technology, and Education (No. ZDXYS202207), and the Jiangsu Commission of Health Medical Research Project (No. M2022064).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the JIPD. Note that the use of data was presented at the beginning of the questionnaire, and personal privacy was well protected.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Fanzhen Mao, Email: maofanzhen@jipd.com.

Yaobao Liu, Email: Yaobao0721@163.com.

References

- 1.Torgerson PR, de Silva NR, Fèvre EM, Kasuga F, Rokni MB, Zhou XN, et al. The global burden of foodborne parasitic diseases: an update. Trends Parasitol. 2014;30(1):20–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hotez PJ, Brindley PJ, Bethony JM, King CH, Pearce EJ, Jacobson J. Helminth infections: the great neglected tropical diseases. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(4):1311–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torgerson PR, Devleesschauwer B, Praet N, Speybroeck N, Willingham AL, Kasuga F, et al. World Health Organization Estimates of the Global and Regional Disease Burden of 11 foodborne parasitic diseases, 2010: A Data Synthesis. PLoS Med. 2015;12(12):e1001920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdoli A, Ardakani HM. Helminth infections and immunosenescence: the friend of my enemy. Exp Gerontol. 2020;133:110852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xie Y, Shi D, Wang X, Guan Y, Wu W, Wang Y. Prevalence trend and burden of neglected parasitic diseases in China from 1990 to 2019: findings from global burden of disease study. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1077723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song LG, Xie QX, Lv ZY. Foodborne parasitic diseases in China: a scoping review on current situation, epidemiological trends, prevention and control. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2021;14(9):385–400. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorny P, Praet N, Deckers N, Gabriel S. Emerging food-borne parasites. Vet Parasitol. 2009;163(3):196–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang X, Wen D, Liang J, Lei J. How the public uses social media wechat to obtain health information in China: a survey study. BMC Med Inf Decis Mak. 2017;17(Suppl 2):66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bian D, Shi Y, Tang W, Li D, Han K, Shi C, et al. The influencing factors of Nutrition and Diet Health Knowledge Dissemination using the WeChat Official Account in Health Promotion. Front Public Health. 2021;9:775729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qi Z, Ya-Peng L, Li L. [Knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) of foodborne parasitic diseases among middle school students in Xuzhou City]. Zhongguo Xue Xi Chong Bing Fang Zhi Za Zhi. 2017;29(6):761–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jing-Han G, Ling-Ling L. [Investigation of knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) of foodborne parasitic diseases among senior high school students in Zigui County]. Zhongguo Xue Xi Chong Bing Fang Zhi Za Zhi. 2017;29(1):96–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.She GL, Lu XF, Ma YC. [Investigation on knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) of college students on food-borne parasitic diseases]. Zhongguo Xue Xi Chong Bing Fang Zhi Za Zhi. 2015;27(4):410–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuguyo O, Mukona DM, Chikwasha V, Gwanzura L, Chirenda J, Matimba A. Prevalence and risk factors for diabetic foot complications among people living with diabetes in Harare, Zimbabwe: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Regenstein JM, Chaudry MM, Regenstein CE. The kosher and halal food laws. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2003;2(3):111–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hossain MAM, Uddin SMK, Sultana S, Wahab YA, Sagadevan S, Johan MR, et al. Authentication of halal and kosher meat and meat products: Analytical approaches, current progresses and future prospects. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022;62(2):285–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xing-Da Y, Shuang L, Ren-Fan Z, Xiao-Xue Z, Chun-Nan D. [Investigation on knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) of foodborne parasitic diseases among medical students]. Zhongguo Xue Xi Chong Bing Fang Zhi Za Zhi. 2019;31(2):197–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao G, He S, Chen L, Shi N, Bai Y, Zhu XQ. Teaching human parasitology in China. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yan R, Wang LJ, Liu L, Li XF, Zhou BY, Jiang N, et al. [A preliminary study on the mixed teaching of human parasitology based on MOOC resources and the experimental teaching digital platform]. Zhongguo Xue Xi Chong Bing Fang Zhi Za Zhi. 2021;33(1):74–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jabbar A, Gasser RB, Lodge J. Can New Digital technologies support parasitology teaching and learning? Trends Parasitol. 2016;32(7):522–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen TTB, Bui DT, Losson B, Dahma H, Nguyen ATT, Nhu HV, et al. Effectiveness of health education in improving knowledge, attitude and practice related to foodborne zoonotic trematodes in Vietnam, with a particular focus on Clonorchis sinensis. Trop Med Int Health. 2024;29(4):280–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sripa B, Tangkawattana S, Sangnikul T. The Lawa model: a sustainable, integrated opisthorchiasis control program using the EcoHealth approach in the Lawa Lake region of Thailand. Parasitol Int. 2017;66(4):346–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaewpitoon SJ, Rujirakul R, Wakkuwattapong P, Matrakool L, Tongtawee T, Norkaew J, et al. Implementation of Health Behavior Education concerning Liver flukes among Village Health volunteers in an Epidemic Area of Thailand. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17(4):1713–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qian MB, Zhou CH, Zhu HH, Zhu TJ, Huang JL, Chen YD, et al. Assessment of health education products aimed at controlling and preventing helminthiases in China. Infect Dis Poverty. 2019;8(1):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aung PL, Pumpaibool T, Soe TN, Burgess J, Menezes LJ, Kyaw MP, et al. Health education through mass media announcements by loudspeakers about malaria care: prevention and practice among people living in a malaria endemic area of northern Myanmar. Malar J. 2019;18(1):362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang L, Jung EH. How does WeChat’s active engagement with health information contribute to psychological well-being through social capital? Univers Access Inf Soc. 2022;21(3):657–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng Y, Zhao Y, Mao L, Gu M, Yuan H, Lu J, et al. The effectiveness of an eHealth Family-based intervention program in patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) in the Community Via WeChat: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2023;11:e40420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y, Li C, Zhang J, Yang M, Zhu G, Liu Y, et al. Using social media for health education and promotion: a pilot of WeChat-based prize quizzes on China national malaria day. Malar J. 2022;21(1):381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhong F, Pengpeng L, Qianru Z. Grouping together to Fight Cancer: the role of WeChat groups on the Social Support and Self-Efficacy. Front Public Health. 2022;10:792699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang P, Sun J, Li Y, Li Y, Sun Y, Luo R, et al. An mhealth-based school health education system designed to scale up salt reduction in China (EduSaltS): a development and preliminary implementation study. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1161282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.