Abstract

Parents (N = 599) of 6-month-old to 10-year-old children were given a handbook intervention that educates about healthy discipline in a pediatric clinic serving low-income families in Nashville, Tennessee. A research assistant spent approximately 1 minute introducing the intervention. A total of 440 parents (73.4%) responded to a follow-up survey 2 to 4 months later. Most parents (88%) who completed the follow-up survey had read at least part of the handbook. Of parents who received the handbook, 63% reported that the handbook helped them discipline their children. Half of parents reported specific changes they made because of the handbook. The most frequently reported changes were more talking/explaining/communicating (25%), more redirecting (7.8%), more patience/listening (6.0%), less anger/yelling (10.8%), and less spanking (7.5%). 42% of parents reported that they shared the handbook with other caregivers, friends, relatives, and children. A brief clinic intervention improves parents’ discipline practices and reaches other caregivers.

Keywords: parenting, primary care, public health, child abuse prevention

Introduction

Parenting lays the foundation for a child’s health. 1 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) encourages health care providers to educate parents about using healthy discipline and avoiding unhealthy discipline, especially physical punishment. 2 Pediatricians can counsel directly or, if available, recommend other resources and programs. A short list of effective programs includes Healthy Steps, 3 the SEEK program, 4 the Video Interaction Project, 5 Triple P, 6 the Incredible Years, 7 and Play Nicely. 8 Despite overwhelming evidence that parenting education works9,10 and that many parents want support, 11 less than half of parents of young children report that they received discipline education as part of their child’s well visit.12,13

This gap in services reflects the many challenges of educating parents about discipline in pediatrics. Pedia-tricians report being hindered by lack of time, lack of resources, lack of knowledge about how to counsel, and lack of evidence that counseling is effective. 14 Other implementation barriers include cost, office-space, determining who will provide the intervention, cultural sensitivity, meeting individual family needs, and educating fathers and other caregivers who may not attend the visit.1,9,15,16 A key point in a document, “Parenting Matters,” published by the National Academies states, “most studies are focused on mothers, with a lack of research on fathers and other caregivers.” 1 Of concern, fathers are often using unhealthy discipline strategies—in 1 report, 40% of fathers spanked their 3-year-old child. 17 Also, parents report that family and friends are who they turn to first for advice about childrearing. 18 Thus, health care providers should consider trying to reach other caregivers through the parent presenting in clinic. Of note, most effective parenting programs are hours in duration and none are known to reach caregivers who do not attend.1,10 Studies of brief clinical interventions are needed to overcome these hurdles.

In this context, the primary aim of this study was to determine whether a brief intervention helps parents improve their discipline and the secondary aim was to determine whether the intervention reaches other caregivers. We discuss how the results have been used to integrate parenting education into the well-child visit at our institution.

Methods

This mixed-methods study reports data from a clinical trial of an educational intervention delivered to parents of young children in a pediatric clinic serving low-income families in Nashville, Tennessee. In this study, we focus only on outcome measures that were collected from the intervention groups, specifically whether parents were helped by, and shared, the intervention. This study was approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board (#161987) on January 10, 2017.

Participants

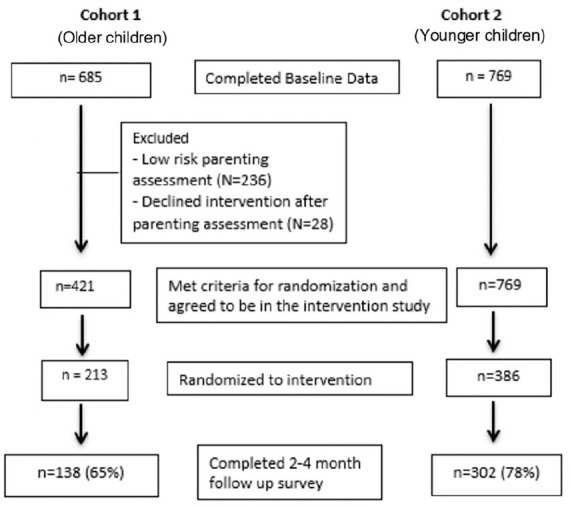

Research assistants recruited English and Spanish-speaking parents presenting with a young child to clinic. In this study, “parent” was defined as any caregiver presenting with the child to the clinic. Although parents were not screened for literacy, parents with poor literacy skills would have been unlikely to enroll after the procedures (ie, complete written survey, read handbook intervention at home) were explained during the informed consent statement. All materials were written at the 8th grade level. Enrollment was completed in 2 cohorts. The first cohort was comprised of parents of 2- to 10-year-old children and was enrolled from January 19 to November 3, 2017. Approximately 70% of eligible parents agreed to be in the study and completed baseline data (N = 685). The second cohort was comprised of parents of 6-month to 2-year-old children and were enrolled from October 16, 2017 to November 5, 2018. Approximately 80% of those eligible parents agreed to be in the study and completed baseline data (N = 769). Parents within each cohort were randomly assigned to receive the Play Nicely Healthy Discipline Handbook intervention. A requirement for eligibility for the intervention in the first cohort was that they were at risk for unhealthy discipline 15 ; 421 met the criteria and 213 were randomly assigned to receive the intervention. Within the second cohort, 386 were randomized to the intervention group. At risk for unhealthy discipline was defined as a Quick Parenting Assessment (QPA) >2; the QPA is a validated instrument designed to detect unhealthy parenting strategies and allow clinicians the opportunity to offer higher precision support to parents. 15 The rationale for recruiting parents who were at risk for unhealthy parenting in the first cohort was to select a more targeted, “at-risk” sample for an initial assessment of the intervention effects. In the second cohort, the priority was to focus on a population-based sample; thus, we recruited all parents whose children were in the designated age range, regardless of parenting behaviors. Two to four months post-intervention, follow-up data were obtained for 138/213 (65%) parents in the first cohort and 302/386 (78%) parents in the second cohort. Figure 1 illustrates the participant flow.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for intervention participants.

Intervention

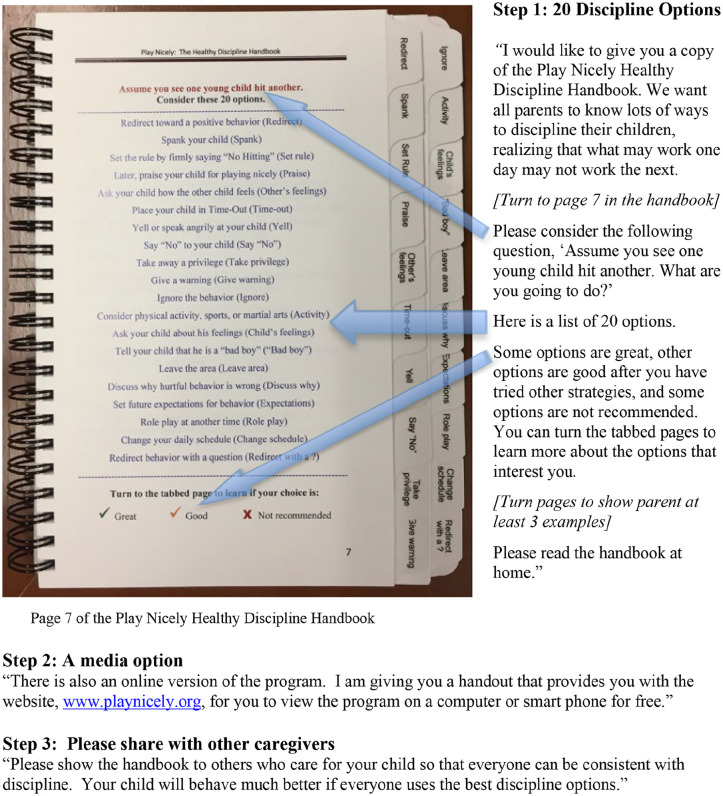

The intervention was a handbook on healthy discipline and a 1-minute introduction to the handbook. Parents assigned to the intervention were given a copy of the Play Nicely Healthy Discipline Handbook, available in English and Spanish. Research assistants introduced the handbook to parents while they were in the examination room, either before or after provider/nurse interaction, using a standardized 1-minute script (Figure 2). Key components in the script were (1) showing parents, on page 7 of the handbook, a list of 20 options to respond to a child with hurtful behavior, (2) demonstrating to parents that there is an online multimedia version, and (3) encouraging the parent to share the resource with other caregivers.

Figure 2.

Research assistants introduced the handbook to parents with a 1-minute script.

Measures

The survey measures were collected using REDCap, a secure, online data storage system. 19 Baseline measures, collected at the time of enrollment on a tablet computer, included demographics and the QPA. Other measures, not reported herein given this paper’s focus, were collected at baseline and follow-up; these included childhood behavior problems, parents’ disciplinary behaviors, and attitudes about spanking.

Participants randomized to the intervention group in each cohort were contacted (via REDCap or phone) 2 to 4 months after being given the Play Nicely Healthy Discipline Handbook for a follow-up survey. Participants were sent a message via email with a REDCap link. If there was no response after 5 emails, participants were called by phone and, if still interested in participating, were sent a new REDCap link either by text or email, per their preference. For a minority of parents who could neither be reached by email or phone, a research assistant attempted to meet the parent in the clinic at a future visit, providing them with the REDCap survey on a tablet computer. Binary yes/no questions were followed by open-ended questions. Key measures, asked only of the intervention groups, were (1) did the handbook help them discipline their child and, if “Yes,” what were they doing differently and (2) did they share the handbook with anyone, and, if “Yes,” whom.

Analysis

Frequency distributions were used to summarize participant characteristics and parents’ responses to the question of how the intervention changed their discipline strategies. Any comparisons were conducted using chi-square tests with P < .05 used for determining statistical significance. Two researchers independently coded parents’ response to the question of changed behavior, compared results, and reconciled any significant discrepancy. We did not perform a formal inter-rater reliability assessment because the categorization of discipline change was straightforward for most responses. For example, 1 parent’s response to the question of what they are doing differently was “I am not just yelling and spanking all the time” and this response was coded into the categories, “Less spanking” and “Less anger/yelling.” One category “More redirecting” did require more clarity; responses were coded as into this category if the word “redirecting” was mentioned or any notion of changing a child’s behavior toward a more positive behavior.

Results

Of the total 599 participants randomized to the intervention, 440 (73.4%) responded to at least one of the quantitative questions about the helpfulness of the handbook. The demographic characteristics of the respondents are summarized in Table 1. Most of the parents (87.7%, 386 of 440) reported that they read parts of the handbook at home (Table 2). The percentage of parents who read the handbook was slightly higher in the cohort with older children (93.5%, 129 of 138) than in the cohort of younger children (85.1%, 257 of 302, P = .013).

Table 1.

Demographics.

| Characteristic | Cohort 1: older children |

Cohort 2: younger children |

All (N = 440) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English (N = 113) | Spanish (N = 25) | English (N = 189) | Spanish (N = 113) | ||

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |

| Age (caregiver) | 30.0 (26-35) | 31.0 (29-35) | 28.0 (23-32) | 28.0 (24-35) | 29.0 (24-34) |

| Age (child) | 4.2 (2.5-7.0) | 5.0 (3.6-7.6) | 1.0 (0.6-1.5) | 1.2 (0.7-1.6) | 1.5 (0.7-2.6) |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Gender (caregiver) | |||||

| Female | 92 (83.6) | 22 (88.0) | 163 (87.2) | 97 (87.4) | 374 (86.4) |

| Male | 18 (16.4) | 3 (12.0) | 24 (12.8) | 14 (12.6) | 59 (13.6) |

| Race (caregiver) | |||||

| White | 32 (29.9) | 0 (0.0) | 51 (27.4) | 2 (1.8) | 85 (19.8) |

| Black | 48 (44.9) | 0 (0.0) | 86 (46.2) | 0 (0.0) | 134 (31.2) |

| Asian | 2 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (3.9) | 2 (1.8) | 15 (3.5) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 13 (12.1) | 23 (92.0) | 26 (14.0) | 104 (93.7) | 166 (38.7) |

| Other | 8 (7.5) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (3.2) | 1 (0.9) | 15 (3.5) |

| Multiple | 4 (3.7) | 2 (8.0) | 6 (3.2) | 2 (1.8) | 14 (3.3) |

| Education level | |||||

| <High school | 13 (12.0) | 4 (16.0) | 18 (9.6) | 47 (43.9) | 82 (19.2) |

| High school | 26 (24.1) | 16 (64.0) | 66 (35.3) | 42 (39.3) | 150 (35.1) |

| Some college | 52 (48.1) | 4 (16.0) | 65 (34.8) | 12 (11.2) | 133 (31.1) |

| ≥Bachelor’s | 17 (15.7) | 1 (4.0) | 38 (20.3) | 6 (5.6) | 62 (14.5) |

| Relationship to child | |||||

| Mother | 93 (84.5) | 22 (88.0) | 155 (83.3) | 100 (90.1) | 370 (85.6) |

| Father | 13 (11.8) | 3 (12.0) | 22 (11.8) | 11 (9.9) | 49 (11.3) |

| Other | 4 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (3.0) |

| Gender (child) | |||||

| Female | 50 (44.2) | 12 (48.0) | 104 (55.9) | 58 (52.3) | 224 (51.5) |

| Male | 63 (55.8) | 13 (52.0) | 82 (44.1) | 53 (47.7) | 211 (48.5) |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Table 2.

Summaries of the Quantitative Helpfulness Responses.

| Characteristic | Cohort 1: older children |

Cohort 2: younger children |

All | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English (N = 113) | Spanish (N = 25) | English (N = 189) | Spanish (N = 113) | (N = 440) | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Read parts at home | |||||

| Yes | 106 (93.8) | 23 (92.0) | 162 (85.7) | 95 (84.1) | 386 (87.7) |

| Info helped discipline | N = 110 | N = 188 | N = 436 | ||

| Yes | 75 (68.2) | 20 (80.0) | 103 (54.8) | 81 (71.7) | 279 (64.0) |

| Share with others | N = 112 | N = 187 | N = 112 | N = 436 | |

| Yes | 51 (45.5) | 10 (40.0) | 76 (40.6) | 45 (40.2) | 182 (41.7) |

Of the parents who received the intervention, a majority (64%, 279 of 436) reported that it helped them discipline their child. There was no statistically significant difference between the cohorts in the percentage of parents reporting that the information in the handbook helped them discipline their children (older = 70.4%, 95 of 135; younger = 61.1%, 184 of 301, P = .063) (Table 2).

The parents (n = 279) who reported that the information helped them were asked, “What, if anything, are you doing differently to discipline your children because of the handbook?” Most parents were able to respond with a specific change (66%, 185 of 279) and the rest of parents either did not respond (25%, 70 of 279) to the question or their response was non-specific (9%, 24 of 279). Of the 185 parents who did respond with a specific change they made in parenting because of the handbook, 132 (71%) reported 1 change and 53 (29%) reported 2 or more changes. The most frequently reported changes were:

More talking/explaining/communicating (33%, 91 of 279).

More redirecting (7.5%, 21 of 279).

More patience/listening (6.4%, 18 of 279).

Less anger/yelling (12.9%, 36 of 279).

Less spanking (7.2%, 20 of 279).

Parents Reported Behavior Change

Examples of parents’ verbatim responses to the question of what they were doing differently to discipline their child as a result of the handbook are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Exemplar Quotes From Parents About Changes in Discipline as a Result of the Handbook.

| More talking/explaining/communicating |

| 1. “By talking to them and explaining things better and helping them understand what is right instead of being angry at them.” |

| 2. “Using more communication and explanation.” |

| 3. “It helps me talk to my child in an orderly fashion.” |

| More Redirecting |

| 1. “Redirecting the child’s behavior into a positive.” |

| 2. “Redirecting my children when they have a tantrum.” |

| 3. “How to discipline and redirect his behavior and deal with different situations differently and with patient.” |

| 4. “I use redirecting to discipline my children.” |

| 5. “Talking out my expectations and redirecting bad behavior with positive activity.” |

| 6. “Whenever he does something he isn’t supposed to do I tell him what he’s supposed to be doing rather than that. For example, when he bites me I tell him that biting is for eating and not for hurting people.” |

| More patience/listening |

| 1. “Just being more patient and knowing that a child is like a sponge so with good explanation and time they do understand.” |

| 2. “I listen to them more and make sure I’m calm before I deal with the discipline.” |

| Less Anger/Yelling and/OR less Spanking |

| 1. “I can explain things to them so I am not just yelling and spanking all the time.” |

| 2. “Talk and explain more, reduced yelling and avoided spanking.” |

| 3. “Less yelling and spanking, more redirecting.” |

| 4. “More talking, less yelling and spanking.” |

| 5. “Used to give spankings, yell more.” |

| 6. “To not yell at them or spank them, to guide them with an example.” |

| 7. “It’s not necessary to yell at them or hit them, to first talk so that they understand better and to not raise the voice at them.” |

| 8. “Choosing other methods discipline instead of spanking.” |

| 9. “Stop spanking.” |

| 10. “It isn’t necessary to spank. be more patient. try to understand how to explain the situation to children instead of hit them.” |

| 11. “Because less spanking and more time out.” |

| Non-specific response |

| 1. “It gave me new ideas to help with my older son because what I was doing never worked.” |

| 2. “It shows you other ways to discipline your child.” |

| 3. “Helped improve both my kids’ behavior.” |

| 4. “Helped us motivate the kids to behave well.” |

Other Notable Parent Responses

One parent commented on how the handbook helped her address her mental health:

It really helped me, plus they gave me some depression medicine which has helped me be able take care of my kids. Not yelling or screaming at kids. When depressed, I was just down. The handbook helped [me] find a provider for depression. Wonderful helpful thing for me, people need to read it. Don’t do stupid things to kids. I really appreciate the handbook.

Another parent reported that the handbook alleviated her guilt for not spanking, stating, It frees me from a lot guilt on choosing other methods discipline instead of spanking. I am a Christian and discipline and love is important to our family. It helped me in terms of guilt with not spanking.Yet another parent indicated that, before the handbook, she was unfamiliar with redirecting:

Very resourceful. The discipline book was very helpful. We raise our kids the way we were raised not knowing anything else. I was not familiar with redirecting my kids and it all makes sense now. I have been redirecting my child more and it has been very helpful.

Reaching Other Caregivers

Many participants (42%, 182 of 436) reported that they shared the handbook with others; the rate of sharing was similar among both cohorts (Table 2). These parents were asked with whom they shared the handbook; 163 of 182 (90%) responded with 119 listing 1 person and 44 listing multiple people. The people with whom parents shared the handbook were a relative (94), friend (33), spouse/fiancé/significant other (28), child/children (15), and other (eg, babysitter/neighbor) (10). One mother who shared the handbook with her husband relayed that it affected her spouse’s parenting behaviors, stating, “My husband has gotten better with disciplining our children.”

Discussion

A 1-minute office-based intervention can affect parenting behaviors and reach other caregivers. Over 80% of parents reported that they read at least part of the handbook intervention, over 60% of parents reported that the handbook helped them discipline their child, and approximately 40% of parents shared the handbook with others. Similar results were observed for both English-speaking and Spanish-speaking parents. This study adds to the literature about parenting in several ways.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that a brief clinical intervention can reach other caregivers, a recognized, high-priority issue. 1 We found that over 40% of parents shared the intervention. Many parents shared the handbook with a spouse, fiancé, or significant other (eg, boyfriend). Interestingly, some parents shared the handbook with their child; 1 parent reported that the father read the book to their child. The actual number of fathers reached is unclear as we do not know how many of the spouses, fiancés, or boyfriends were fathers. Still, a takeaway message is that clinicians can reach other caregivers and children, who may be future parents, via brief office-based interventions.

Brief interventions, 8 in contrast to other effective parenting programs that typically require hours,3 -7 may offer a scalable solution to the challenge of implementing parenting interventions in pediatric primary care. In that context, another important finding is that parenting interventions, even brief ones, can be effective in a printed format. The Play Nicely multimedia program, which mirrors the content of the handbook, can affect parenting outcomes as documented in over a dozen studies. 8 Parents who were given the Play Nicely CD-ROM by their pediatrician reported that the program helped them manage their child’s aggression 1 year later. 20 In other studies, parents who viewed the multimedia program shifted their attitudes toward using less physical punishment, both short term 21 and several months later. 22 Parents who viewed 5 to 10 minutes of the program in clinic were 12 times more likely to report a planned change in how they discipline compared with a control group. 23 The multimedia program (50 minutes) has been demonstrated to improve clinicians’ knowledge and skills to counsel parents about healthy discipline.24 -26 That brief parenting interventions can be effective in different formats is important as formats will need to vary depending upon the setting (eg, clinic, home), learner preferences, literacy skills, availability of resources (eg, Internet), cost (eg, once developed, multimedia programs can be delivered at no cost), and other factors.

An unexpected finding, albeit from only 1 parent, was a mother’s unsolicited comment that the intervention prompted her to obtain treatment for her depression. This is important because of the link between parental depression, parenting, and child behavior. 27 We speculate that the following handbook content played a role:

Consider the mental health of family members. For example, parents with depression may have difficulty managing challenging behavior. Parents with an alcohol or drug addiction will not be able to monitor children as needed. You might ask yourself, ’Are all of my child’s caregivers mentally and physically able to care for my child?’ If not, seek professional advice.

Further studies are needed to determine the role of brief interventions in guiding parents toward seeking help for themselves.

There are several limitations of the study. Parents who did not respond to the follow-up survey may have reported different experiences with the intervention (ie, non-response bias). The study was conducted at 1 site and had 1 intervention. In this analysis, we focus only on data, mostly qualitative, that were collected from participants in the intervention groups; follow-up analyses, beyond the scope of this article, will be needed to compare outcomes between the intervention and control groups. Social desirability bias may have prompted some parents to inaccurately report that the handbook helped them discipline their child and that they shared the resource. However, this bias would not explain the qualitative data that suggests actual parental behavior change. Also, it seems unlikely that a parent would fabricate the person with whom they shared the handbook. Another limitation is that the handbook was delivered by a research assistant rather than a health care provider. However, given the recognized value of the parent/physician relationship, we suspect that having a primary care provider deliver the intervention script would, if anything, increase the potency of the intervention.

At our institution, these and other data have been operationalized into clinical practice. Ideally, parenting education and support, tailored to the family’s needs, should be included in well-child visits.1,2,15,28 One challenge for providers is determining the appropriate level of support, realizing that some parents need little parenting support whereas other parents need extensive resources. To increase objectivity about the level of parenting support needed, providers in our clinic use a validated parenting assessment. 15 Then, when at-risk families are identified, the health care provider can offer support as indicted with evidence-based interventions. 15

In summary, for parents from diverse backgrounds, a simple intervention shows promise to shift norms related to parenting and reach children’s other caregivers. The findings have implications for overcoming barriers related to educating more parents about healthy discipline strategies. If parents routinely receive effective education about healthy discipline in pediatric primary care and are asked to share resources with other caregivers, it could, in theory, prevent many poor health outcomes.

Author Contributions

Dr. Scholer conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Dr. Dietrich helped design the study, analyzed the data, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Ms. Adams coordinated and supervised data collection, analyzed the data, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Dr. Martin collected data, analyzed the data, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Numbers: Clinical trial numbers are NCT03058861 and NCT04160013.

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr Scholer is the author of the Quick Parenting Assessment (QPA) and Play Nicely, a parenting program. Both the QPA and Play Nicely are owned by Vanderbilt University. The other authors have no relevant conflicts to disclose.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Building Strong Brains Adverse Childhood Experiences Initiative. State of Tennessee. FY2017-FY2019. The funder had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

ORCID iD: Seth J. Scholer  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1657-2575

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1657-2575

References

- 1. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Parenting Matters: Supporting Parents of Children Ages 0-8. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sege RD, Siegel BS; Council on Child Abuse and Neglect; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. Effective discipline to raise healthy children. Pediatrics. 2018;142(6):e20183112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Minkovitz CS, Strobino D, Mistry KB, et al. Healthy Steps for Young Children: sustained results at 5.5 years. Pediatrics. 2007;120(3):e658-e668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dubowitz H, Feigelman S, Lane W, Kim J. Pediatric primary care to help prevent child maltreatment: the Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) Model. Pediatrics. 2009;123(3):858-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mendelsohn AL, Valdez PT, Flynn V, et al. Use of videotaped interactions during pediatric well-child care: impact at 33 months on parenting and on child development. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2007;28(3):206-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sanders MR, Kirby JN, Tellegen CL, Day JJ. The Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: a systematic review and meta-analysis of a multi-level system of parenting support. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34(4):337-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Perrin EC, Sheldrick RC, McMenamy JM, Henson BS, Carter AS. Improving parenting skills for families of young children in pediatric settings: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(1):16-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vanderbilt University. Play nicely: the healthy discipline program. Published 2015. Accessed March 12, 2022. http://www.playnicely.org.

- 9. Smith JD, Cruden GH, Rojas LM, et al. Parenting interventions in pediatric primary care: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2020;146(1):e20193548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shah R, Kennedy S, Clark MD, Bauer SC, Schwartz A. Primary care-based interventions to promote positiveparenting behaviors: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2016;137(5):e20153393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Taylor CA, Moeller W, Hamvas L, Rice JC. Parents’ professional sources of advice regarding child discipline and their use of corporal punishment. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2013;52(2):147-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Olson LM, Inkelas M, Halfon N, Schuster MA, O’Connor KG, Mistry R. Overview of the content of health supervision for young children: reports from parents and pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2004;113(suppl 6):1907-1916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Finch SA, Weiley V, Ip EH, Barkin S. Impact of pediatricians’ perceived self-efficacy and confidence on violence prevention counseling: a national study. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12(1):75-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fleckman JM, Scholer SJ, Branco N, Taylor CA. Educating parents about corporal punishment and effective discipline: pediatricians’ preparedness, motivation, and barriers. Acad Pediatr. 2021;21(1):149-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sausen KA, Randolph JW, Casciato AN, Dietrich MS, Scholer SJ. The development, preliminary validation, and clinical application of the quick parenting assessment. Prev Sci. 2022;23(2):306-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kolko DJ, Perrin E. The integration of behavioral health interventions in children’s health care: services, science, and suggestions. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2014;43(2):216-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. MacKenzie MJ, Nicklas E, Waldfogel J, Brooks-Gunn J. Spanking and child development across the first decade of life. Pediatrics. 2013;132(5):e1118-e1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Edwards R, Gillies V. Support in parenting: values and consensus concerning who to turn to. J Soc Policy. 2004;33:627-647. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Scholer SJ, Cherry R, Garrard HG, IV, Gupta AO, Mace R, Greeley N. A multimedia program helps parents manage childhood aggression. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2006;45(9):835-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chavis A, Hudnut-Beumler J, Webb MW, et al. A brief intervention affects parents’ attitudes toward using less physical punishment. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37(12):1192-1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Scholer SJ, Hamilton EC, Johnson MC, Scott TA. A brief intervention may affect parents’ attitudes toward using less physical punishment. Fam Community Health. 2010;33(2):106-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Scholer SJ, Hudnut-Beumler J, Dietrich MS. A brief primary care intervention helps parents develop plans to discipline. Pediatrics. 2010;125(2):e242-e249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Scholer SJ, Reich SM, Boshers RB, Bickman L. A multimedia violence prevention program increases pediatric residents’ and childcare providers’ knowledge about responding to childhood aggression. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2005;44(5):413-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Scholer SJ, Reich SM, Boshers RB, Bickman L. A brief program improves counseling of mothers with children who have persistent aggression. J Interpers Violence. 2012;27(6):991-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Scholer SJ, Brokish PA, Mukherjee AB, Gigante J. A violence-prevention program helps teach medical students and pediatric residents about childhood aggression. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2008;47(9):891-900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Callender KA, Olson SL, Choe DE, Sameroff AJ. The effects of parental depressive symptoms, appraisals, and physical punishment on later child externalizing behavior. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2012;40(3):471-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. O’Connell LK, Davis MM, Bauer NS. Assessing parenting behaviors to improve child outcomes. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):e286-e288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]