Abstract

Research has shown peer victimization to have strong lasting effects on adolescents’ mental health. The purpose of the current study was to examine relationships among religiousness, forgiveness and mental health in the context of peer victimization. We hypothesized that religiousness and forgiveness may be protective factors against negative effects of peer victimization on internalizing symptomatology and emotion regulation. Participants were 127 adolescents between 12 and 18 years and their primary caregivers. Results of Structural Equation Modeling analyses show that religiousness may not be a strong protective factor in the context of peer victimization and that certain dimensions of forgiveness (specifically benevolence motivations) may actually exacerbate the effects of peer victimization on internalizing symptomatology rather than acting as a protective factor.

Keywords: Adolescent, Peer Victimization, Protective Factors, Religiousness, Forgiveness, Mental Health, Internalizing Symptomatology, Emotion Regulation

Most adolescents will experience some form of peer victimization and many will experience chronic victimization throughout their school years (Hanish & Guerra, 2000). Two primary mental health issues that have been shown to be affected by peer victimization are emotion regulation and internalizing symptomatology (Herts et al., 2012; Prinstein, Cheah, & Guyer, 2005). Thus, the identification of protective factors that may aid adolescents in developing healthy emotion regulation and guard against internalizing symptomatology is an important step in understanding positive development in adolescence. Religiousness and forgiveness are two factors that have been shown to promote the development of emotion regulation and protect against the development of internalizing symptomatology (e.g. Ellison & Levin, 1998; Hackney & Sanders, 2003; Hirsch, Webb, & Jeglic, 2011; McCullough, 2000; Van Dyke & Elias, 2007), but have not been examined in the context of peer victimization. The current study examined whether religiousness and forgiveness serve as protective factors with regard to the effects of peer victimization on internalizing symptomatology and emotion regulation among adolescents.

Peer Victimization and Adolescent Mental Health

Peer victimization may take the form of physical (e.g. pushing, hitting, and kicking) or verbal (e.g. name calling, making fun of, or slander) attacks on an individual (Mynard & Joseph, 2000). It is well established in literature that both physical and verbal peer victimization can increase internalizing symptomatology and promote deficits in emotion regulation. Prinstein et al. (2005) noted the cyclical nature of peer victimization and internalizing symptomatology. In a longitudinal study spanning 17 months, they found that adolescents are more likely to experience depressive symptoms in response to peer victimization if they have a previous tendency to make critical self-referent attributions from ambiguous or negative social cues. They also stated that such interpretation of social cues may lead to behaviors such as withdrawal that increase the likelihood of further victimization. Such behaviors, in turn, affirm those social cue interpretations and subsequent behaviors resulting in increased internalizing symptomatology. In a meta-analysis of 18 longitudinal studies of peer victimization, Reijntjes et al. (2009) found that internalizing symptomatology acts as both an antecedent and a consequence of peer victimization. Specifically, being victimized by peers is related to higher internalizing symptomatology and that children with internalizing symptoms are more likely to be victimized, resulting a cycle that increases the likelihood of continued victimization.

Peer victimization is also associated with emotion dysregulation and, like internalizing symptomatology, may have a cyclical relationship with peer victimization. Shields and Cicchetti (2001) studied maltreated children’s risk for victimization and found that emotion dysregulation mediated the association between maltreatment and increased risk for victimization. Thus, emotion dysregulation may be a contributing factor to experiences of victimization. A longitudinal study by Herts et al. (2012) demonstrates that emotion regulation may also be a consequence of peer victimization. The authors studied 1,065 early adolescents over a four month period and found peer victimization to predict subsequent increases in emotion dysregulation. Similar to the study by Prinstein et al. (2005) cited earlier emphasizing the importance of social cue interpretation, Herts et al. (2012) speculated that peer victimization can have a negative effect on emotion regulation because of disruptions in social processing. The authors state that disruptions in social processing could adversely affect emotion regulation because they deprive the adolescent of information necessary to regulate emotional states with regard to the situation.

Extant research clearly supports that peer victimization can have extreme negative and long term effects on adolescents. However, not all adolescents who are exposed to peer victimization experience internalizing symptomatology and emotional dysregulation. This leads to the conclusion that factors must exist that buffer the adverse effects of peer victimization. Research as to what factors may help adolescents who experience peer victimization combat internalizing symptomatology and develop good emotion regulation is imperative in order to promote healthy psychological development in adolescents. Given previous research that demonstrates the benefits of religiousness and forgiveness for mental well being (e.g. Ellison & Levin, 1998; Hackney & Sanders, 2003; Hirsch et al., 2011; McCullough, 2000; Van Dyke & Elias, 2007), the current study propose that religiousness and forgiveness act as protective factors against the adverse effects of peer victimization.

Religiousness and Forgiveness as Protective Factors

According to McCullough and Willoughby (2009), religiousness may be defined as “cognition, affect, and behavior that arise from awareness of, or perceived interaction with supernatural entities that are presumed to play an important role in human affairs (p. 71).” Religiousness has been found in numerous studies to be inversely related to depression and has been found to be a protective factor against unfavorable outcomes in children and adolescents who have experienced trauma and emotional or physical maltreatment (e.g. Kim, 2008; Perez et al., 2009; Schnittker, 2001; Smith, McCullough, & Poll, 2003; Van Dyke & Elias, 2007). Similarly, a study of young to middle adults (ages 18 to 46 years) indicated that individuals high in intrinsic religiousness display better psychological adjustment and report greater life satisfaction (Salsman, Brown, Brechting, & Carlson, 2005). It has been concluded that the findings relating religiousness to lower depression are robust and hold across age, gender, and ethnicity (Smith et al., 2003). However, to the authors’ knowledge, religiousness has never been examined as possible protective factor against the adverse effects of peer victimization. Thus, the current study seeks to expand research on religiousness as a protective factor by examining its effects in the context of peer victimization.

Prior research suggests a strong relationship between forgiveness and factors associated with mental health. We view the conceptualization of forgiveness as prosocial changes in transgression-related interpersonal motivations (McCullough, Root, & Cohen, 2006). Desrosiers and Miller (2007) found forgiveness to be inversely related to depression in adolescent girls. Brown (2003) also found forgiveness to be inversely related to depression in college students. Forgiveness in adult samples has been associated with not only lower levels of negative affect such as anger and anxiety but also higher levels of positive affect such as happiness, hopefulness, and confidence (Van Dyke & Elias, 2007) as well as greater life satisfaction (Allemand, Hill, Ghaemmaghami, & Martin, 2012).

Hirsch et al. (2011) suggested that forgiveness affects mental health because it helps people “cognitively and emotionally progress beyond distressing experiences or persons from his or her past.” Thus, forgiveness helps people “let go” of negative emotions and thoughts that may cause emotional distress. Additionally, forgiveness in adolescence may lead to new developmental experiences that aid in dealing with future transgressions or negative life events such as learning compassion for others, and enhanced gratitude for interpersonal support systems (Enright, Freedman, & Rique, 1998; Van Dyke & Elias, 2007). While research on forgiveness and mental health in college students and adults is increasing, literature on the effects of forgiveness in adolescence is still lacking. Despite the fact that adolescents are often in situations of interpersonal conflict (e.g. abuse, peer victimization), little is known about how they forgive or what effect their forgiveness has on mental health outcomes (Worthington, 2004). Given the lack of understanding regarding how and whether forgiveness plays a protective role in adolescents’ coping with stressors, research on forgiveness and adolescent’s mental health is much needed.

The Present Study

The current investigation presents the first study examining religiousness and forgiveness as possible moderators in the relationship between peer victimization and internalizing symptomatology and emotion regulation. It was hypothesized that religiousness and forgiveness would moderate the relationship between peer victimization and the mental health outcomes such that the detrimental effects of peer victimization on adolescent internalizing symptomatology and emotion regulation are significantly lower for adolescents with higher levels of religiousness and forgiveness, compared to adolescents with lower levels of religiousness and forgiveness.

Method

Participants

Participants were 127 adolescents (71 males) between 12 and 18 years of age (M = 15.28; SD = .31) and their primary caregivers (parents, hereafter; mean age = 46.32; SD = 6.34) Parents were 82% mothers, 14% fathers, 3% grandmothers, and 1% other. Adolescents identified as 89% Caucasian, 6% African American, 1% Hispanic, 3% Biracial, and 1% other. Adolescent religious affiliation was 59% Protestant, 11% Catholic, 1% Jewish, 13% Other, and 16% None. Mean family annual income was between $35,000 and $49,000 (SD = 2.31 in the scale of 1 = $0 to 15 = $200,000 or more per year).

Procedures

Participants were from a southeastern state and were contacted via phone lists purchased from contact companies, snowball sampling (word-of-mouth), by responding to flyers, or by responding to notices placed on the internet. Families who were eligible (i.e. with an adolescent aged between 10 and 17 years) and were interested in the study were asked to call the research office. Research assistants described the nature of the study to the interested individuals over the telephone and invited them to participate. Data collection took place at the university’s offices in 2010. Upon arrival, the parent and the adolescent were escorted to separate interview rooms. Measures for the study were administered by two trained research assistants, one with each participant. Prior to the interview, parent consent and adolescent assent were obtained. The interviewers read the instructions to the participants and were present while participants filled out the questionnaires. Parents and adolescents received monetary compensation for participating. All procedures were approved by the university’s institutional review board.

Measures

Peer Victimization.

Peer victimization was measured using a modified version of the Multidimensional Peer Victimization Scale (MPVS; Mynard, & Joseph, 2000). The scale consisted of 8 items designed to measure aspects of victimization during the past year through negative physical actions (e.g. punched, kicked) and negative verbal actions (e.g. made fun of me for some reason, swore at me). Each item is rated on a three point Likert scale ranging from 0 = Not at all, 1 = Once, 2 = More than once. Scale reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) of the current sample was .81.

Religiousness.

The religiousness scale was a 13-item scale adapted from Fetzer Institute & National Institute on Aging Working Group (1999) and Jessor and Jessor’s (1977) Value on Religion Scale. The instrument contains three subscales: organizational religiousness, private practices, and personal religiousness. Organizational religiousness consists of two items measuring the respondent’s participation in formal religious activities, such as religious services or youth group attendance. Private practices religiousness consists of four items assessing informal religious practices, such as prayer. Personal religiousness consists of four items assessing the importance of faith. A composite variable of religiousness was created by averaging the scores of each of the three subscales. The composite variable of religiousness was used in the main analyses. Reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha) coefficients from the current sample were: Organizational religiousness = .78, Private Practice = .85, and Personal Religiousness = .90.

Forgiveness.

Behavioral forgiveness was measured using the Transgression-Related Interpersonal Motivations Inventory (TRIM; McCullough et al., 2006). The TRIM is an 18-item measure with the subscales of avoidance, revenge, and benevolence. Participants are asked to think about someone who has harmed them in the past and rate the items are on a five-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The avoidance subscale contains items such as “I live as if he/she doesn’t exist,” the revenge subscale includes items such as “I’ll make him/her pay,” and the benevolence subscale includes items such as “Even though his/her actions hurt me, I have goodwill for him/her.” Reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha) coefficients from the current sample were: Avoidance = .90, Revenge = .89, and Benevolence = .84.

Internalizing symptomatology.

Internalizing symptomatology was measured using the Youth Self Report (YSR; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) and the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). The YSR is a 102-item questionnaire assessing adolescents’ behavior problems and is typically used with children/adolescents between 11 and 18. The internalizing scale includes withdrawn, anxious/depressed, and somatic complaints syndrome scales. Higher score indicates more behavior problems. The YSR has shown strong psychometric properties on internalizing behaviors (α = .90; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). The CBCL is a 118-item questionnaire assessing caregiver perceptions of children’s behavior problems. The internalizing scale includes withdrawn, anxious/depressed, and somatic complaints syndrome scales where higher score indicates higher internalizing problems. The CBCL has demonstrated strong psychometric properties on internalizing symptomatology (α = .90; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001).

Emotion Regulation.

Adolescent emotion regulation was measured using the Emotion Regulation subscale of the Emotion Regulation Checklist (ERC; Shields & Cicchetti, 1997). The ERC is a 24 item scale that is completed by the child or an adult familiar with the child (in the case of the present sample, the parent or guardian). The Emotion Regulation subscale reflects processes central to adaptive regulation such as emotional self-awareness and empathy. Items are rated on a four point Likert scale ranging from 1 = Rarely/Never to 4 = Almost Always. For purposes of the current study, both parent and child reports of the ERC were used. Reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) from the current sample were .66 for parent reports and .70 for adolescent reports.

Plan for analysis

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) analyses were used to test the hypotheses. Moderation effects were tested by including interaction terms in the model. Overall model fit indices were examined using the following measures: (1) χ2 value, (2) degrees of freedom, (3) corresponding p-value, (4) Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and (5) Confirmatory Fit Index (CFI). An RMSEA value less than .06 and a CFI value equal to or greater than .95 indicated a good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). An α level of .05 was used for all statistical tests except in the case of the interactions. For testing interactions an alpha level of.10 was considered acceptable given the low power that characterizes analyses of moderator effects in quasi-experimental research designs (McClelland & Judd, 1993).

Results

Preliminary analyses

Data were screened for outliers and multivariate non-normality using Mahalanobis’s distance values. There was no outlier that had a Mahalanobis’s distance score greater than the critical value [χ2 (10) = 29.558, p < .001]. Skewness and kurtosis were also examined and fell within acceptable ranges (Skewness < 3; Kurtosis < 10). Descriptive statistics and correlations are presented in Table 1. Adolescent age was found to be significantly correlated with physical peer victimization (r = −.140, p < .038) and emotion regulation (r = .170, p < .012) and was added as a covariate in the main analyses. Ethnicity was not found to be significantly correlated with study variables and was not included in further analyses (p= .154 to .854).

Table 1.

Bivariate Correlations and Descriptive Statistics

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PV | ||||||||||

| 2.VV | .432** | |||||||||

| 3.REL | .092 | −.047 | ||||||||

| 4.REV | .119 | .135 | −.116 | |||||||

| 5.AV | .145 | .255** | −.013 | .371** | ||||||

| 6.BEN | −.116 | −.158 | .176* | −.330** | −.640 | |||||

| 7.CER | −.196 | −.147 | .078 | −.295** | .018 | .095 | ||||

| 8.PER | −.062 | −.065 | −.002 | −.221* | −.089 | .028 | .318** | |||

| 9.YSR | .071 | .440** | .005 | .195* | .110 | .002 | −.346** | −.101 | ||

| 10.CBC | .092 | .370** | −.036 | .212* | .092 | .027 | −.205* | −.340** | .454** | |

| 11.AGE | −.184* | −.033 | −.128 | −.188* | .062 | .117 | .210* | .137 | .037 | −.121 |

| M | 1.11 | 1.57 | 4.68 | 2.01 | 3.06 | 3.18 | 3.32 | 3.30 | 51.02 | 15.28 |

| SD | 0.28 | .061 | 1.81 | 0.89 | .99 | 0.86 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 9.80 | 1.65 |

| N | 127 | 127 | 127 | 127 | 127 | 127 | 127 | 127 | 127 | 127 |

Note: PV = Physical Victimization, VV = Verbal Victimization, REL = Religiousness Composite, REV = Revenge Motivations, AV = Avoidance Motivations, BEN = Benevolence Motivations, CER = Adolescent Reported Emotion Regulation, PER = Parent Reported Emotion Regulation, YSR = Adolescent Reported Internalizing Symptomatology, CBC = Parent Reported Internalizing Symptomatology, Age = Adolescent Age.

p < .05

p < .01.

Measurement model testing

Emotion Regulation and Internalizing Symptomatology.

Latent factors of emotion regulation and internalizing symptomatology were constructed using adolescent and parent reports. The correlated factors in the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) were comprised of adolescent report (ERC_C) and parent report (ERC_P) of adolescent’s emotion regulation for the emotion regulation latent factor, and adolescent report (YSR) and parent report (CBCL) of adolescent’s internalizing symptomatology for the internalizing symptomatology latent factor. The model was fully saturated (χ2 = 0, df = 0) and factor loadings were strong and significant with ERC_C (b* = .437, p < .01) and ERC_P (b* = .727, p < .05) for emotion regulation, and YSR (b* = .876, p < .01) and CBCL (b* = .519, p < .01) for internalizing symptomatology.

Hypothesis testing

SEM was used to test the association between peer victimization (physical and verbal) on adolescent internalizing symptomatology and emotion regulation as moderated by a latent factor of religiousness and three subscales of forgiveness (revenge, avoidance, and benevolence motivations). A latent factor for religiousness was used due to a strong correlation among the three subscales (r = .683, .717, .737) and because previous research has established use of the scale as a latent factor (e.g., Kim-Spoon, Farley, Holmes, & Longo, 2013). In contrast, subscale scores of the TRIM were used because the correlations among the three subscales were not substantial (r=> −.330, .371, −.640) and previous research has used these subscales individually (e.g., McCullough et al, 2006). Physical and verbal victimization were tested in separate models with each moderator separately, thus, ten separate models were tested.

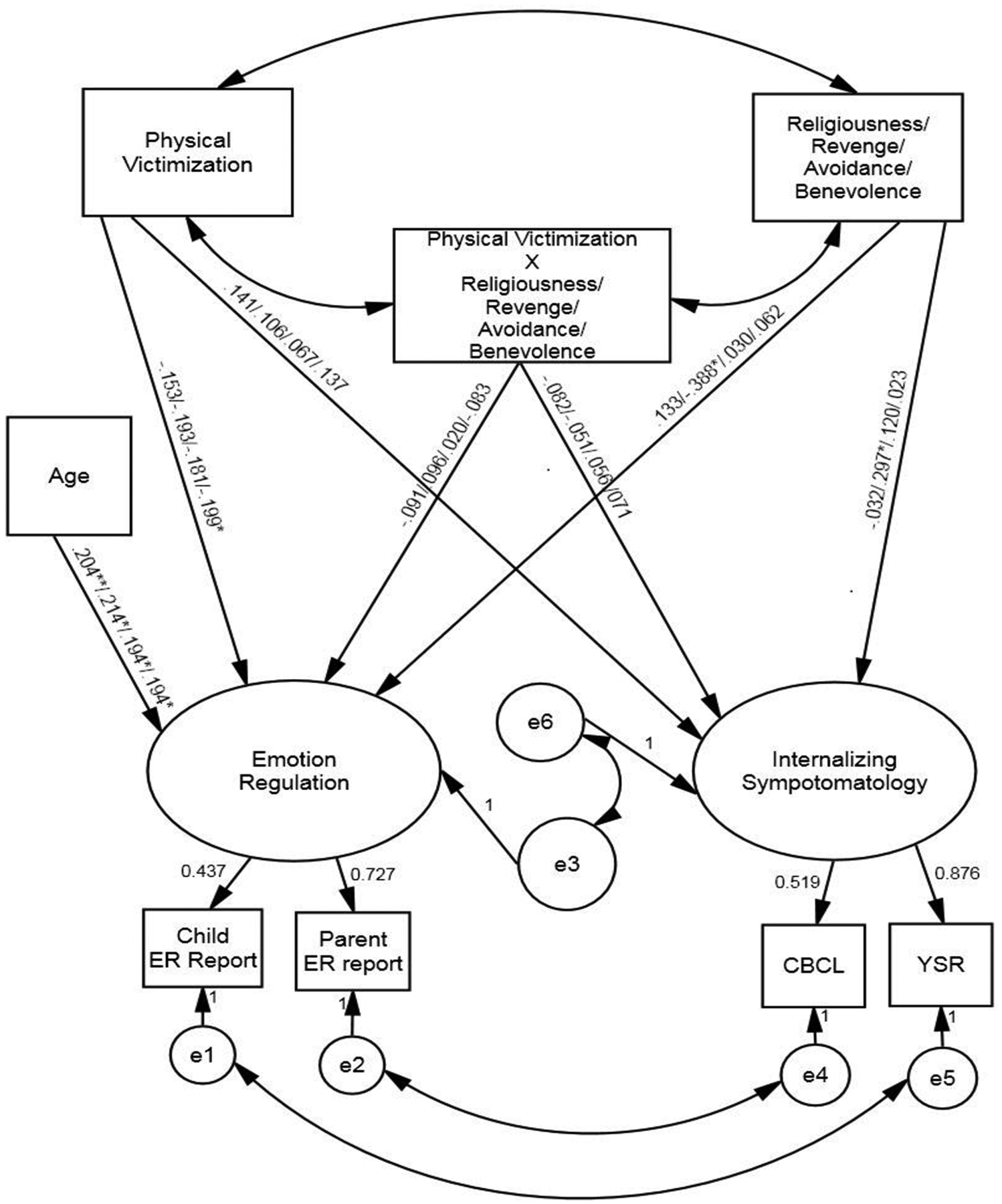

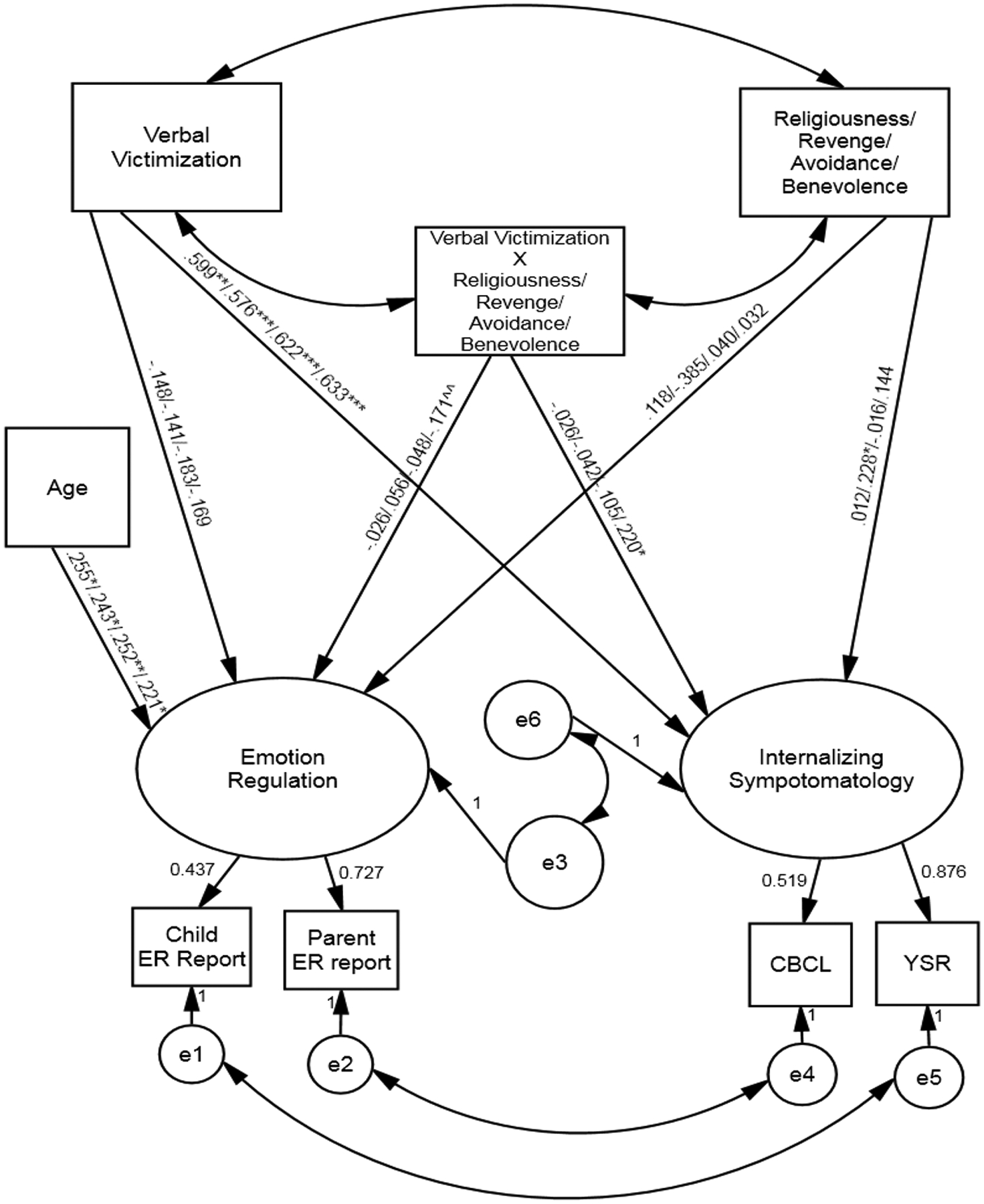

First, physical victimization, religiousness, and the interaction between physical victimization and religiousness were entered in to an SEM model predicting the outcomes of adolescent emotion regulation and internalizing symptomatology (see Figure 1). The model fit was excellent (χ2 = 7.181, df = 10, p = .708; CFI = 1.000; RMSEA = .000) but no path coefficients were found to be significant indicating that no relationships among the variables could be inferred. Similarly, verbal victimization, religiousness, and an interaction term between verbal victimization and religiousness were entered into an SEM model predicting the two outcomes (see Figure 2). The model fit was excellent (χ2 = 8.103, df = 10, p = .619; CFI = 1.000; RMSEA = .000). Verbal victimization was found to be significantly related to internalizing symptomatology (b* = .599, p < .001). No other path coefficients were found to be significant. In sum, religiousness was not shown to be a significant moderator between physical or verbal victimization and adolescent adjustment.

Figure 1.

Moderation effects of Religiousness, Revenge, Avoidance, and Benevolence on Physical Victimization and mental health outcomes. Standardized coefficients are presented in the format Religiousness/Revenge/Avoidance/Benevolence.

Figure 2.

Moderation effects of Religiousness, Revenge, Avoidance, and Benevolence on Verbal Victimization and mental health outcomes. Standardized coefficients are presented in the format Religiousness/Revenge/Avoidance/Benevolence.

Next, revenge motivations were examined as a moderator between physical victimization and the two outcomes (see Figure 1). Model fit was excellent (χ 2 = 9.118, df = 10, p =. 521; CFI = 1.000; RMSEA = .000) and revenge motivations were shown to be a negatively related to adolescent emotion regulation (b* = −.388, p < .001) and positively related to internalizing symptomatology (b* = .297, p < .03). No other path coefficients were significant. Similarly, revenge motivations were examined as a moderator between verbal victimization and the two outcomes (Figure 2). Model fit was excellent (χ2 = 8.879, df = 10, p = .544; CFI = 1.0; RMSEA = .000). Verbal victimization was positively related to internalizing symptomatology (b* = .576, p < .001), and revenge motivations were negatively related to emotion regulation (b* = −.385, p < .001) and positively related to internalizing symptomatology (b* = .228, p < .02). No other path coefficients were significant. In sum, revenge motivations were not shown to be a significant moderator.

The next two models tested avoidance motivations as a moderator in the relationship between physical victimization and the two outcomes (see Figure 1; χ2 = 5.483 df = 10, p = .857; CFI = 1.0; RMSEA = .000) as well as between verbal victimization and the two outcomes (see Figure 2; χ2 = 7.787 df = 10, p = .650; CFI = 1.000; RMSEA = .000). Only verbal victimization was shown to be significantly related to internalizing symptomatology (b* = .633, p < .001). No other path coefficients were significant. In sum, avoidance motivations were not found to be a significant moderator.

The final two models tested benevolence motivations as a moderator in the relationship between physical victimization and the two outcomes (see Figure 1; χ2 = 7.697 df = 10, p = .658; CFI = 1.000; RMSEA = .000) as well as verbal victimization and the two outcomes (see Figure 2; χ2 = 11.731 df = 10, p = .384; CFI = .993; RMSEA = .023). Benevolence motivations were found to be a significant moderator in the relationship between verbal victimization and emotion regulation (b* = −.171, p = .082) and internalizing symptomatology (b* = .220, p < .02). No effects of benevolence motivations were found for physical victimization.

A two group SEM model was used to probe the interaction between verbal victimization and benevolence motivations. A mean split was used to separate high and low benevolence groups. First, the path between verbal victimization and emotion regulation was constrained to be equal across groups. If the model fit degrades by imposing an equality constraint, the result indicates that the two groups significantly differ from each other with respect to the magnitude of the association between verbal victimization and emotion regulation. Significance testing for model fit difference suggested no significant difference between the high and low benevolence groups (Δχ2 = 2.310, Δdf = 1, p = .129) for emotion regulation. Second, equality constraint on the path between verbal victimization and internalizing symptomatology was added. Significance testing showed that the groups were significantly different (Δχ2 = 3.915, Δdf = 1, p = .048). For the low benevolence group, verbal victimization showed a positive relationship with internalizing symptomatology (b* = .554, p < .001). For the high benevolence group verbal victimization showed an even stronger positive relationship with internalizing symptomatology (b* = .645, p < .001). Thus, in contrast to the hypothesized direction of the relationship, higher benevolence motivations exacerbated rather than buffered the effects of verbal victimization on internalizing symptomatology.

Discussion

In general, the hypothesis that religiousness and forgiveness would buffer the adverse effects of peer victimization on internalizing symptomatology and emotion regulation were not directly supported. Benevolence motivations were found to moderate the relationship between verbal victimization and internalizing symptomatology, but the direction of the relationship was not as predicted. Instead of buffering the effects of verbal victimization on internalizing symptomatology, having high benevolence motivations appears to exacerbate the detrimental effects of verbal victimization among adolescents. In addition, significant main effects of peer victimization, religiousness, and forgiveness on the outcomes indicated that high verbal victimization was associated with high internalizing symptomatology and high revenge motivations were associated with poor emotion regulation and high internalizing symptomatology.

The lack of main effects of physical victimization may be explained, in part, by limitations of the scale and the relatively low prevalence of physical victimization in the sample. As detailed in the methods section, the MPVS consists of 8 items measured victimization only during the past year. Thus the scale provided a limited picture of experienced victimization and did not measure intensity or chronicity of victimization. Additionally, the current sample showed relatively low rates of peer victimization. Specifically, the MPVS was scored by calculating the mean of the indicated values across questions for each subscale and the highest score possible for the subscale was four and no participants scored four. About 99 percent of participants scored two or lower on the physical victimization subscale.

Religiousness was not shown to be a protective factor against adverse effects of peer victimization. Given that religiousness is usually shown to be a protective factor among adolescents, this finding is noteworthy and exploration as to why religiousness was not shown to be a protective factor in the context of peer victimization. One possible explanation is that research on factors that protect against adverse effects of peer victimization usually focus on relational factors such as support of family and friends. Most research on the protective effects of religiousness reveals it to be a protective factor in the face of maltreatment (usually by a caregiver or family member, e.g. Kim, 2008). Family conflict and divorce are also stressors in which adolescent religiousness is shown to be a protective factor (for a review see Paloutzian & Park, 2005). In sum, extant research shows that religiousness as a protective factor against stressors of a close relational nature. Particularly, when family and friend support levels are low, religiousness may act as a substitute for lack of relational support and therefore become more salient to the adolescent as a protective factor. However, when the stressor is not family or relational in nature (i.e. peer victimization), it is possible that social support of family and friends are the primary resource of protection for adolescents experiencing victimization. Thus, religiousness, in the context of also having good support from family and friends, may not be as salient in dealing with victimization experiences. A direction for future research might be to examine religiousness as a protective factor among adolescents experiencing peer victimization with varying degrees of support from family or friends.

With regard to the moderation effects of forgiveness on the relationship between peer victimization and mental health, the question that arises is why revenge and avoidance motivations appear to not have an effect on the relationship and why benevolence motivations appear to have an adverse effect even though extant research consistently shows forgiveness to be beneficial to mental health. Wade, Worthington, and Meyer (2005) suggest that the manifestation and effects of certain components of forgiveness may not be consistent across all relationships. In particular, feelings of positive regard (i.e. benevolence motivations) for the forgiven transgressor may only occur - and only be necessary - in close, continuing relationships.

According to McCullough (2001), forgiveness may be conceptualized as a transformation in emotional, cognitive and behavioral motivations towards a transgressor from negative to positive. These motivations can be captured in the three domains of revenge, avoidance, and benevolence. A person who has gone through the process of forgiving a transgressor should have given up revenge motivations, not have motivation to avoid the transgressor, and also, feel benevolence towards the transgressor despite past harm. However, the current study supports the idea that not all domains of forgiveness may manifest or even be necessary given the context of the relationship. For example, if the person who needs forgiveness is a family member, close friend, or colleague with whom a continued relationship may be a positive thing then having low avoidance motivations may be important. However, in the context of peer victimization, the transgressor is likely someone who will continue the abuse whether forgiveness is given or not. In this case, it may not be beneficial- indeed it could actually be dangerous- for the forgiver to give up avoidance motivations. Thus, in this context forgiveness may be given but avoidance motivations maintained.

With regard to revenge motivations, the lack of buffering effects may be explained by the nature of the construct. Having revenge motivations indicates the harboring of negative feelings and resentment that manifests in the desire to “get back” at the transgressor. However, not having revenge motivations says little about the harboring of negative feelings. One can harbor hurt and resentment but not feel the need to exact revenge. Revenge has been defined as “the infliction of harm to an offender in return for perceived wrong” and resentment as “a cold, emotional complex consisting of bitterness, hostility, residual fear, and residual anger in response to perceived harm from an offender.” While revenge and resentment may often co-occur they are not the same thing and the absence of revenge does not necessarily mean forgiveness (Mullet, Neto, & Rivére, 2005). Thus, revenge motivations, assessed independently, may not account for the process of forgiveness to be a significant protective factor.

The findings regarding the effects of benevolence are more difficult to explain given that extant research consistently supports positive benefits of forgiveness on mental health. That said, as mentioned before, little is known about forgiveness among adolescents and how forgiveness might be related to overcoming stressors like peer victimization that are especially salient to adolescents. Understanding of these relationships is especially important in developing interventions and helping adolescents deal with peer victimizations. Egan and Todorov (2009) argued for the need of forgiveness interventions in schools to help adolescents in dealing with bullying. However, the results of the current study highlight that this approach must be viewed with caution until more is known about forgiveness among adolescents.

The results of this study by no means indicate that benevolence motivations are universally detrimental nor do the results allow for the conclusion that forgiveness in general can be detrimental. They merely suggest that in the specific context of verbal victimization, high benevolence motivations are related to higher internalizing symptomatology. One possible explanation is that adolescents may be excusing or condoning the victimization rather than forgiving. Excusing and condoning relate to making excuses, justifying the behavior and absolving the transgressor of blame. Forgiveness, in contrast, specifically allows for the change in motivations towards a transgressor and overcoming emotional hurt while acknowledging that the transgressor has wronged them (Van Dyke & Elias, 2007). If adolescents excuse or condone those that are victimizing them, they may be placing the blame for the victimization on themselves which may then contribute to higher internalizing symptomatology.

Such a phenomenon is observed in women who stay in abusive relationships. They often make excuses for the behavior of their abusive partner and have positive feelings towards the transgressor and have negative feelings towards themselves such as low self-esteem (Cardi, Milich, Harris, & Kearns, 2007; Katz, Street, & Arias, 1997). Katz and colleagues (1997) found that women who had lower self-esteem reported that they would be more likely to forgive a partner who abused them. However, research shows that they are not actually “forgiving” their partner but “excusing” or “condoning” often by placing the blame on themselves and calling it forgiveness. Likewise, in the case of peer victimization, if adolescents have low self-esteem then they may report high benevolence motivations for transgressors because they take the blame upon themselves which may put them at greater risk for internalizing symptomatology. Indeed, prior research indicated that victimized middle school students reported high self-blame attributions of their victimization and low self-worth (Graham & Juvonen, 1998; Raskauskas, 2010). This tendency for low self-esteem and self-blame presents a caution in the promotion of forgiveness interventions. Indeed, Miller (2003) makes a case against promoting forgiveness in therapy for this very reason. Miller argues that forgiveness does not resolve latent hatred and self-hatred but simply masks them and can actually worsen feelings of guilt. The results of this study seem to provide preliminary evidence that supports Miller’s argument. However, it is important that an individual understand what forgiveness means before they are encouraged to engage in the process. Individuals, specifically those who are lower in self-esteem, may not understand that forgiveness does not absolve the transgressor of blame. Future research should examine adolescent conceptualizations of forgiveness as related to self-esteem and interventions promoting forgiveness should take care to educate individuals on the true meaning of forgiveness.

One limitation of the study is that the data is cross-sectional, therefore causal effects cannot be inferred. Additionally, we have relatively low power, due to small sample size, given the complexity of the model. A major strength of the study is that we had multiple informants (both parent and adolescent report) for the adolescent outcomes of emotion regulation and internalizing symptomatology. However, the relations between peer victimization and adolescent religiousness and forgiveness were estimated based solely upon adolescents’ self-reports, and they might have been influenced by method variance. Using multiple methods (e.g., observation, clinical interview, and formal diagnostic criteria) as well as multiple informants (e.g., parents, teachers, and clinicians) and may be recommended for future research. Finally, the forgiveness measure we used (TRIM) focused on assessing forgiveness that is specific to someone who has harmed and focused on the dimensions of revenge, avoidance, and benevolence. Future studies will benefit from examining the role of forgiveness that reflects the general propensity of the individual across different situations of interpersonal transgression and provide a better assessment of negative feelings towards transgressors as well as taking into account individual understanding of forgiveness and the possibility of self-blame.

Conclusion

In sum, the current study demonstrates that religiousness was not shown be a protective factor against victimization, possibly because relational support is a more salient factor. The findings also suggest that the manifestation and effects of domains of forgiveness may vary with context and that benevolence motivations may exacerbate the effects of victimization on internalizing symptomatology among adolescents. How adolescents perceive victimization by their peers may be an essential component of understanding how victimization affects mental health and has important implications for interventions with victimized adolescents. A forgiveness intervention as suggested by Egan and Todorov (2009) may be helpful to many adolescents dealing with peer victimization, but researchers developing forgiveness interventions for victimized adolescents should be cautious of simply advocating forgiveness without clearly defining what is meant by forgiveness. Additionally, research on forgiveness should strive to understand how individuals’ conceptualizations of forgiveness may affect results when studying the effects of forgiveness on mental health.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD057386).

References

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla L (2001). Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms and Profiles. Burlington,VT: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont. [Google Scholar]

- Allemand M, Hill PL, Ghaemmaghami P, & Martin M (2012). Forgivingness and subjective well-being in adulthood: The moderating role of future time perspective. Journal of Research in Personality, 46, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Brown RP (2003). Measuring individual differences in the tendency to forgive: Construct validity and links with depression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 759–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardi M, Milich R, Harriss MJ, & Kearns E (2007). Self-esteem moderates the response of forgiveness instructions among women with a history of victimization. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 804–819. [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers A, & Miller L (2007). Relational spirituality and depression in adolescent girls. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63 1021–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan LA, & Todorov N (2009). Forgiveness as a coping strategy to allow school students to deal with the effects of being bullied: Theoretical and empirical discussion. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 28, 198–222. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, & Levin JS (1998). The religion-health connection: Evidence, theory, and future directions. Health Education & Behavior, 25, 700–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enright R, Freedman S, & Rique J (1998). The psychology of interpersonal forgiveness. In Enright R & North J (Eds.), Exploring Forgiveness (pp.46–62). Madison: University of Wisconsin. [Google Scholar]

- Fetzer Institute & National Institute on Aging Working Group. (1999). Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/spirituality for use in health research. Kalamazoo, MI: Fetzer Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Graham S & Juvonen J (1998). Self-blame and peer victimization in middle school: An attributional analysis. Developmental Psychology, 34, 587–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackney CH, & Sanders GS (2003). Religiosity and mental health: A meta-analysis of recent studies. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 42, 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hanish LD, Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Spinrad TL,Ryan P, & Schmidt S (2004). The expression and regulation of negative emotions: Risk factors for young children’s peer victimization. Development and Psychopathology, 16, 335–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herts KL, McLaughlin KA, & Hatzenbuehler ML (2012). Emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking stress exposure to adolescent aggressive behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 1111–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch JK, Webb JR, & Jeglic EL (2011). Forgiveness, depression, and suicidal behavior among a diverse sample of college students. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67.9, 896–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, & Jessor SL (1977). Problem behavior and psychological development. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Katz J, Street A, & Arias I (1997). Individual differences in self-appraisals and responses to dating violence scenarios. Violence and Victims, 12, 265–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J (2008). The protective effects of religiosity on maladjustment among maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Child Abuse and Neglect, 32, 711–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Spoon J, Farley JP, Holmes CH, & Longo GS (2013). Religiousness buffers effects of abuse and poor self-control on adolescent substance use. Manuscript under review.

- McCullough ME (2000). Forgiveness as human strength: Theory, measurement, and links to well being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19, 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME (2001). Forgiveness: Who does it and how do they do it? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10, 194–197. [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Root LM, & Cohen A (2006). Writing about the benefits of an interpersonal transgression facilitates forgiveness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 887–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, & Willoughby BLB (2009). Religion, self-regulation, and self-control: Associations, explanations, and implications. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 69–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland GH, & Judd CM (1993). Statistical Difficulties of Detecting Interactions and Moderator Effects. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 376–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A (2003). Concerning forgiveness: The liberating experience of painful truth. Retrieved from http://www.alice-miller.com/articles_en.php?nid=48.

- Mullet E, Neto F, & Riviere S (2005). Personality and its effect on resentment, revenge, forgiveness, and self-forgiveness. In Worthington EL Jr. (Eds.) Handbook of Forgiveness (pp. 159–181). New York: Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Mynard H, & Joseph S (2000). Development of the multidimensional peer- victimization scale. Aggressive Behavior, 26, 169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Paloutzian RF, & Park CL (Eds.). (2005). Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Cheah CSL, & Guyer AE (2005). Peer victimization, cue interpretation, and internalizing symptoms: Preliminary concurrent and longitudinal findings. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 11–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez JE, Little TD, & Henrich CC (2009). Spirituality and depressive symptoms in a school-based sample of adolescents: a longitudinal examination of mediated and moderated effects. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 44, 380–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskauskas J (2010). Multiple peer victimization among elementary school students: Relations with social-emotional problems. Social Psychology of Education, 13, 523–539. [Google Scholar]

- Reijntjes A, Kamphius JH, Prinzie P, & Telch MJ (2009). Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Child Abuse and Neglect, 34, 244–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salsman JM, Brown TL, Brechting EH, & Carlson CR (2005). The link between religion and spirituality and psychological adjustment: the mediating role of optimism and social support. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 522–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker J (2001). When is faith enough? The effects of religious involvement on depression. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 3, 393–411. [Google Scholar]

- Shields A, & Cicchetti D (1997). Emotion regulation among school-age children: The development and validation of a new criterion Q-sort scale. Developmental Psychology, 33, 906–916. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.33.6.906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields A, & Cicchetti D (2001). Parental maltreatment and emotion dysregulation as risk factors for bullying and victimization in middle childhood. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30(3), 349–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TB, McCullough ME, & Poll J (2003). Religiousness and depression: Evidence for a main effect and the moderating influence of stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 614–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke CJ & Elias MJ (2007). How forgiveness, purpose, and religiosity are related to the mental health and well-being of youth: A review of the literature. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 10, 395–415. [Google Scholar]

- Wade NG, Worthington EL Jr, & Meyer JE (2005). But do they work? A meta-analysis of group interventions to promote forgiveness. Handbook of forgiveness, 423–439. [Google Scholar]

- Worthington EL Jr. (2004). The new science of forgiveness. Greater Good, 1, 6–9. [Google Scholar]