Abstract

The first night in an unfamiliar environment is marked by reduced sleep quality and changes in sleep architecture. This so-called first-night effect (FNE) is well established for two consecutive nights and lays the foundation for including an adaptation night in sleep research to counteract FNEs. However, adaptation nights rarely happen immediately before experimental nights, which raises the question of how sleep adapts over nonconsecutive nights. Furthermore, it is yet unclear, how environmental familiarity and hemispheric asymmetry of slow-wave sleep (SWS) contribute to the explanation of FNEs. To address this gap, 45 healthy participants spent two weekly separated nights in the sleep laboratory. In a separate study, we investigated the influence of environmental familiarity on 30 participants who spent two nonconsecutive nights in the sleep laboratory and two nights at home. Sleep was recorded by polysomnography. Results of both studies show that FNEs also occur in nonconsecutive nights, particularly affecting wake after sleep onset, sleep onset latency, and total sleep time. Sleep disturbances in the first night happen in both familiar and unfamiliar environments. The degree of asymmetric SWS was not correlated with the FNE but rather tended to vary over the course of several nights. Our findings suggest that nonconsecutive adaptation nights are effective in controlling for FNEs, justifying the current practice in basic sleep research. Further research should focus on trait- and fluctuating state-like components explaining interhemispheric asymmetries.

Keywords: first-night effect, environment, sleep quality, polysomnography, asymmetry, sleep/wake cognition, EEG analysis, electrophysiology

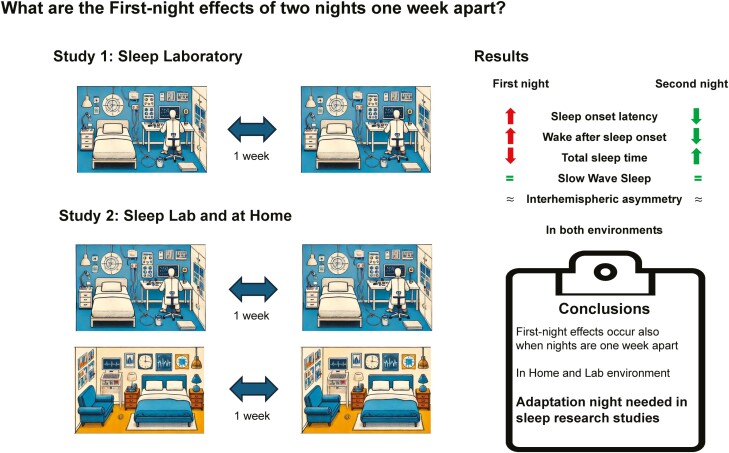

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Statement of Significance.

Sleep studies aim to investigate the nature of sleep to provide appropriate treatments or interventions to improve its quality. However, the sleep quality during the first night of sleep studies in unfamiliar environments seems to be confounded by a first-night effect. Here, we provide evidence that the current practice in sleep research of using adaptation nights several days before the actual experiment is effective in controlling for sleep impairments on the first night. These adaptation nights remain important in both unfamiliar (e.g. sleep lab) and familiar (e.g. home recording) environments.

A considerable body of literature describes that sleep during the first night in a new, unfamiliar surrounding differs from sleep in a familiar environment. This phenomenon is known as the first-night effect (FNE) of sleep and was first described by Agnew et al. [1] in 1966. In 2022, Ding et al. [2] conducted a meta-analysis of 53 studies on the FNE over consecutive nights and found that indeed sleep quality (SQ) and quantity were generally reduced in the first night compared to the second night: particularly, objective sleep onset latency (SOL), wake after sleep onset (WASO), the duration spent in nonrapid eye movement (NREM) sleep N1, and rapid eye movement (REM) latency were all longer on the first night. Additionally, compared to the second night, there was a decrease in total sleep time (TST), sleep efficiency, and REM sleep. However, the meta-analysis did not find any significant effect on slow-wave sleep (SWS) or SWS latency, nor any effects on N2 sleep. Based on the known changes in sleep architecture during the first night in an unfamiliar environment, it is recommended for sleep studies to include one adaptation night prior to the subsequent experimental night but to disregard its data for further analyses [3]. Although this procedure is associated with a high investment of effort, time, and money for researchers [3], it is generally accepted in the field of sleep research.

However, this common practice has several weaknesses. First, the relative importance of adaptation nights for all sleep studies is controversial, depending on whether primary sleep variables are a central object of the investigation or not [4]. Second, although Ding et al. [2] concluded in their meta-analysis that no significant differences were observed in most sleep parameters between the second and the following nights, it remains unclear whether an unfamiliar environment influences the sleep architecture only in the first night or whether the adaptation process continues onto subsequent nights ([1, 2, 5–7]). Third, the FNE is influenced by several factors, such as sleep patterns in the past week [3] or age (i.e., milder FNEs in young participants compared to older participants [2]). Finally, and most importantly, most data on the FNE are derived from studies conducted on consecutive nights, meaning that participants spent two nights in a row in the sleep lab [2]. This procedure differs from the common practice in sleep research, which typically includes an adaptation night several days or even weeks before the actual experimental night. Thus, to establish a strong foundation for integrating adaptation nights in sleep research, data on the FNE and adaptation effects of sleep in an unfamiliar environment over several nonconsecutive nights in healthy young participants are required. So far, only very few studies have systematically examined adaptation processes across nonconsecutive nights. One study by Lorenzo and Barbanoj [8] recorded sleep in healthy young participants in three sessions over the course of four consecutive nights each. The interval between the three sessions was 1 month. They observed reductions in objective SQ, particularly significant changes in REM-related sleep variables indicative of an FNE only in the first night of the first session. No FNE was observed in the first nights of the second or third session.

A similar finding is reported by Thornby [9] who studied healthy young participants for four nights each separated by a few days. An FNE was also observed, especially in variables related to REM sleep. In a long-term study over 10 weeks, patients with insomnia slept in the sleep laboratory for two consecutive nights each week. The authors did not report any reoccurrence of the FNE [10]. However, Scharf et al. [11] also carried out a long-term sleep study with patients with insomnia. As opposed to Stepanski et al. [10], they reported that a reduction in SQ indicative of FNE occurred when patients with insomnia returned to the sleep laboratory. Thus, although some findings suggest that adaptation to the new environment may also be observed in nonconsecutive sleep recordings, the data are not fully consistent.

In addition, it remains unclear whether FNEs in nonconsecutive nights only occur in unfamiliar environments, or whether they also occur in a familiar environment (e.g. at home) [5]. For consecutive nights, impairments of sleep in the first night also occur in familiar home settings, possibly due to the unfamiliarity of the recording situation and the polysomnographic equipment (e.g. electrodes, etc., see meta-analysis [2]). However, it is still unknown whether FNEs also occur in a home environment when recording nights are spaced apart by several days.

Finally, the underlying mechanisms generating FNEs remain unclear. In recent years, an interesting hypothesis has been proposed linking changes in sleep architecture during the first night to asymmetric sleep behavior: Tamaki et al. [12] proposed that the FNE may be related to increased monitoring demands of the new, unfamiliar environment, reflected in a decrease in one hemisphere’s depth of sleep. In their study, the left hemisphere showed reduced power in the delta activity range (1–4 Hz) during SWS in the first night, but not in the second night recorded 1 week later. This interhemispheric asymmetry of delta activity during SWS predicted increases in objective SOL during the first night. Follow-up studies confirmed that the left hemisphere reacted more vigilantly than the right hemisphere in the first sessions. From these data, the researchers concluded that the FNE might act as a protective mechanism in an unfamiliar environment during the first night by keeping one brain hemisphere more alert. Contrary to this idea, multiple earlier studies examining interhemispheric asymmetries have found no consistent relationship between hemispheric asymmetry during SWS and FNEs [13, 14]. Furthermore, recent studies rather suggest stable and trait-like components for hemispheric asymmetries during sleep, possibly linking the degree of asymmetries to inter-individual differences in the anatomy of the corpus callosum [15]. In light of these contradicting findings, we also analyzed whether or not the hemispheric asymmetry of delta oscillations during SWS was larger during the first night compared with subsequent nights and whether the degree of asymmetry was correlated with an FNE of sleep.

Thus, the aim of our study was to investigate whether an FNE reoccurs in sleep studies with nonconsecutive weekly nights, and whether or not FNEs in a familiar environment differ from those in an unfamiliar environment. In addition, we examined the degree of interhemispheric asymmetric activity (IAA) over the course of the different nights and in the different environments. To generate more data on this equivocal matter, we studied the adaptation processes over two, weekly separated, nonconsecutive nights. In Study 1, 45 participants spent two nights in the sleep laboratory. In Study 2, 30 participants spent two nights in the sleep laboratory, and two nights at home, in a balanced sequence. Sleep was recorded using polysomnography. We show that an FNE occurs in nonconsecutive nights mainly affecting SOL, WASO, and TST. In addition, we report that FNEs occur in nonconsecutive nights in both familiar and unfamiliar environments. Finally, we find that the degree of IAA of delta oscillations during SWS is not related to the FNE, but that the left-hemispheric reduction in sleep depth is rather stable over the course of the nonconsecutive nights.

Methods

Participants

Study 1 is a re-analysis of data sets drawn from two independent experiments (published in [16, 17]; A more detailed description of the two subsamples is provided in Supplementary Information). We collapsed the data of both experiments into one single data set, as the two experimental designs were basically identical (see Design and procedure for further details). Study 1 included 45 young and healthy participants (32 females), ages 18–31 (M = 22.27; SD = 2.85) in the analysis of sleep parameters. In the frontal asymmetry analysis, we included only 35 participants due to the loss of the essential frontal EEG electrodes during one night of the two recorded nights.

Study 2 was specifically designed to investigate the adaptation process between an unfamiliar and a familiar sleeping environment. A total of 31 healthy young participants (22 female, 1 diverse) were included, aged 19–31 (M = 22.81; SD = 3.28). Due to the loss of EEG electrodes during the night, the data from one participant had to be excluded from the analysis of sleep architecture and another data set had to be excluded from the frontal asymmetry analysis. As a result, data from 30 participants were taken into account in each analysis.

All participants were either German-, French-, or Italian-speaking, in good general health (as indicated by the absence of any medical conditions, physical or mental diseases as assessed by a prescreening questionnaire) and reported a healthy wake-sleep cycle with no sleep problems. In addition, the participants were not involved in shift work and did not suffer from jet lag. We recruited participants via a newsletter sent to psychology students and advertisements on several internet platforms. Two days before each session, participants received a reminder e-mail containing the instruction to refrain from consuming caffeine and alcohol for two days prior to the experiment. Additionally, we asked participants to get up no later than 7:00 am on the day of the experiment. Noteworthy, for Study 2, an additional eligibility requirement was that participants generally did not share a bedroom.

The studies were approved by the local ethics committee and all participants gave written informed consent at the beginning of the adaptation night. The study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. Participants received a compensation of 160 CHF for their participation. In case of an early abandonment, we paid participants proportionally.

Design and procedure

In both studies, we recorded sleep using polysomnography (see Figure 1 for a summary of our design and procedure). In Study 1, participants spent all nights in the sleep laboratory at the University of Fribourg, with exactly 1 week between both nights (Figure 1a). Nights were undisturbed but differed with respect to presleep instructions and interventions which were counterbalanced intra-individually (see [16, 17] and Supplementary Information). Thus, it is possible to rule out the impacts of these interventions on order and habituation during the nights. Participants arrived at the sleep laboratory every night between 08:15 and 08:30 pm. After filling out various questionnaires, participants had time to get prepared for the night. Next, the experimenter attached the electrodes for the polysomnographic recordings and the participants performed a cognitive task. Then, the participants went to bed and lights were turned off for 8 h. In the morning, the experimenter turned on the light and woke up the participant. Participants immediately filled out questionnaires and performed several cognitive tasks. Subsequently, the experimenter detached the electrodes, and the participants left the laboratory between 7:00 and 8:00 am.

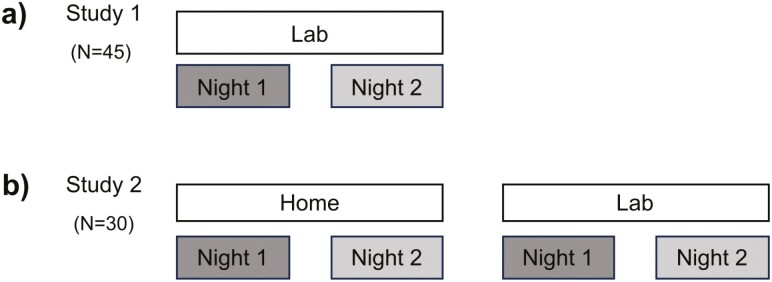

Figure 1.

(a) Study design of Study 1: the study consisted of two nights, each separated by 1 week. In all nights, participants slept in the sleep laboratory. (b) Study design of Study 2: the study consisted of four nights, each separated by a 1-week interval. Half of the participants slept first in the sleep laboratory for two nights and then two nights at home or vice versa. The order was randomized and counterbalanced between the participants.

In Study 2, the participants spent two nights in the sleep laboratory and two nights in their usual familiar environment, each seperated by one week, in a balanced order (Figure 1b). We considered the sleep laboratory as the “unfamiliar” sleep environment and sleeping at home as the “familiar” sleep environment. After the experimenter attached all electrodes, participants either went home or spent the night in the sleep laboratory.

Before participants left the laboratory to sleep at home, the experimenter instructed them to sleep according to their individual sleep habits. In contrast, we strictly enforced a bedtime between 10:30 and 11:00 pm in the sleep laboratory, and the participants were woken up after exactly 8 h.

Questionnaires

Prior to the first session, participants filled out various questionnaires to obtain information about demographics, general health, handedness, drug consumption, and personality. We used the Morningness-Eveningness-Questionnaire [18] and Pittsburgh Sleep Questionnaire Inventory [19] to gain information about the chronotype, self-reported SQ, and sleep habits during the last 4 weeks. Throughout each session, participants filled out short questionnaires before they went to bed and after they woke up. They rated their SQ of the preceding night. They were also asked about any alcohol, nicotine, caffeine, and other drug consumption during the day. Finally, in order to determine the present mood, they used a Likert scale to rate several items (MDBF [20]).

The following morning, we operationalized the self-reported SQ from the previous night using the SF-A/R questionnaire [21], and once more, we collected data on the participants’ moods using the MDBF [20].

Polysomnographic recordings

We collected electrophysical data during sleep using different polysomnographic components: The electroencephalogram (EEG) consisted of 12 single gold-cups electrodes which we positioned in accordance with the international 10–20 system (C3, C4, Cz, F3, F4, Fpz, P3, P4, M1, M2, O1, and O2) [22]. Moreover, we attached the electromyogram (EMG), the electrooculogram (EOG), and the electrocardiogram (ECG) according to the international recommendation by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM [23]). We derived the EEG referentially, whereas the EMG, EOG, and ECG were generated bipolar. However, we maintained all impedances below 5 kΩ and set the sampling rate to 500 Hz, along with the low- and high-frequency recording filters of each component set to the suggested level of the AASM (EEG: 0.3 Hz/35 Hz; EOG: 0.3 Hz/35 Hz; EMG: 10 Hz/100 Hz; ECG: 0.3 Hz/70 Hz) [23].

In Study 2, we used a mobile polysomnographic device (SOMNOtouch RESP, SOMNOmedics, Randersacker, Germany), for electrophysiological recordings with 10 single gold-cup electrodes. We positioned the six EEG electrodes at F3, F4, Fpz, Cz, M1, and M2 [22] and the two EOG and two EMG electrodes following the standards of the AASM [23].

Sleep scoring

Prior to sleep scoring, we used the program BrainVisionAnalyzer 2.2 (Brain Products, Gilching, Germany) to prepare and filter the polysomnographic data as recommended by the AASM [23]. Then, we segmented the 8 h of bedtime (from “Lights Off” to “Lights On”) into 30-s epochs, which were visually scored and classified into the different stages “Wake,” “REM,” “N1‘, ’N2,” or “SWS” by two independent sleep research PhD students, who are highly trained and experienced in sleep scoring. The agreement rate of the two sleep scorers was on average 86%. In case of a disagreement, we consulted a third expert sleep scorer.

Power analysis

We used the BrainVisionAnalyzer 2.2 (Brain Products, Gilching, Germany) for EEG data management and frequency analyses. In the beginning, we imported sleep scorings as segmentation markers. For the following steps of performing a Fast Fourier Transformation (FFT), we used the procedure described by Ackermann et al. [24] with small exceptions. Likewise, we set a high-pass filter (0.1 Hz) and a low-pass filter (40 Hz) and re-referenced the data to the averaged power of both mastoids. Then, we used the SleepCycles package for R [25] to segment the sleep into its sleep cycles. Following the procedure of Tamaki et al. [12] we also inspected only the SWS of the first sleep cycle.

After performing these steps, within the SWS of the first sleep cycle, we created equally sized sections of 2048 data points respectively 4 s with a 100-point overlap. Making sure that only segments free of artifacts were analyzed, an automatic artifact rejection excluded segments, if the maximal difference in EMG activity was over 150 µV and the maximal difference in each EEG channel was over 500 µV. Finally, an FFT with a 10% Hanning window and a resolution of 0.25 Hz was performed for every EEG channel to calculate the power (in µV) of the delta (1–4.5 Hz), theta (4.5–8 Hz), alpha (8–11 Hz) sigma (11–15 Hz) and beta (15–25 Hz) frequency bands. Importantly, due to the fact that only frontal electrodes (F3 and F4) were available in Study 2, it was only possible to compare the frontal power of the different frequency bands in both Study 1 and 2.

Asymmetry index

The asymmetry index (AI) corresponds to the interhemispheric slow-wave activity (SWA) in the frontal regions during SWS and it is calculated following the formula [(left SWA − right SWA)/(left SWA + right SWA)] [12]. The more the final value (given in µV) differs from 0 the more asymmetric activity was present.

Statistical analysis

We carried out all analyses using the R Studio software 4.3.1 [26]. In order to determine the existence and appearance of an FNE and asymmetric activity, we ran several sets of analyses of variances (ANOVAs). Effect patterns were further explored by post hoc t-tests. For all analyses, the significance level was set to p ≤ .05, and a level of p < .1 was considered to indicate a statistical trend. When Mauchly’s tests revealed a violation of sphericity, the correction proposed by Greenhouse-Geisser was used. Prior to any analyses, objective data were checked for outliers. When a value for each individual sleep metric throughout the course of the two nights together exceeded the range of ± 3 SD of the mean formed, that value was conservatively designated as an outlier. In this case, the participant was excluded from the ANOVA considering the respective sleep parameter. This was done separately for Study 1 and 2.

We used no correction for multiple comparisons. We deliberately chose a liberal statistical threshold to reduce the chance of false negatives and to increase the statistical power of our study. This allows us to detect also medium-sized FNEs on sleep parameters. With this strategy, we minimized the chance of falsely concluding that some parameters do not show FNEs when they actually do. Thus, we were more conservative in rejecting the need for an adaptation night. Conversely, if we do not find significant differences for certain sleep parameters even with our liberal threshold, we can be fairly certain that no medium-sized adaptation effect exists for these parameters. This means that an adaptation night is probably not necessary when these sleep parameters (e.g. SWS) are the focus of investigation. We believe that our liberal statistical strategy is well justified given the main aim of our study. Please note that our strategy implies that some of our reported FNEs may be false positives and therefore require independent replication.

Results

In a first analysis step, we tested adaptation effects across the two first nights in Study 1. Then, we report the impact of the factor “Environment” on the adaptation process in Study 2. In the end, we present the results concerning the IAA within the delta band during SWS.

Study 1: adaptation processes over four nonconsecutive nights

In Study 1, we detected evidence for a FNE for the following sleep parameters: Objective SOL, TST, and total time between sleep onset and lights on (TOTAL), and trends for wake after sleep onset (WASO) and SWS latency (see Table 1 for descriptive values).

Table 1.

Sleep parameters of Study 1

| Sleep parameter | Night 1 | Night 2 | Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SEM | Mean±SEM | N | ANOVA | |

| SOL (min)a | 20.37 ± 2.05 | 14.01 ± 2.19 | 45 | F(1,44) = 8.33, p =.006, ηG2 =.05 |

| WASO (%)b | 3. 5 ± 0.58 | 2.26 ± 0.39 | 43 | F(1,42) = 3.33, p =.075, ηG2 =.04 |

| N1 (%) | 5.85 ± 0.34 | 6.14 ± 0.36 | 43 | F(1,42) = 0.59, p =.448, ηG2 <.01 |

| N2 (%) | 46.25 ± 1.1 | 47.66 ± 1.01 | 45 | F(1,44) = 1.20, p =.279, ηG2 =.01 |

| SWS (%) | 21.64 ± 1.18 | 20.69 ± 0.8 | 44 | F(1,43) = 0.66, p =.422, ηG2 <.01 |

| REM (%) | 19.48 ± 0.74 | 20.34 ± 0.6 | 45 | F(1,44) = 1.19, p =.281, ηG2 <.01 |

| SWS latency (min)b | 15.69 ± 0.97 | 14.14 ± 0.89 | 45 | F(1,44) = 3.03, p =.089, ηG2 =.02 |

| REM latency (min) | 103.07 ± 5.98 | 90.83 ± 5.98 | 44 | F(1,43) = 2.82, p =.100, ηG2 =.02 |

| TST (min)a | 438.05 ± 5.05 | 450.65 ± 4.14 | 44 | F(1,43) = 4.26, p =.045, ηG2 =.04 |

| TOTAL (min)a | 457.99 ± 3.2 | 465.95 ± 2.57 | 42 | F(1,41) = 4.60, p =.038, ηG2 =.04 |

| Self-reported SOL (min) | 19.22 ± 2.34 | 15.12 ± 2.7 | 45 | F(1,44) = 2.00, p =.165, ηG2 =.01 |

| Self-reported WASO (min) | 14.63 ± 3.13 | 13.56 ± 3.47 | 45 | F(1,44) = 0.09, p =.771, ηG2 <.01 |

| Self-reported SQ (index) | 26.36 ± 0.68 | 26.16 ± 0.75 | 45 | F(1,44) = 0.05, p =.818, ηG2 <.01 |

Time spent in the different sleep stages in Study 1 during Night 1 and Night 2. Numbers are means ± SEM (in minutes or percentage). All effects are indicated by bold text.

aAverage of the first night differed significantly from the second night (p < .05).

bAverage of the first night differed from the second night marked with a trend (p < .1).

Abbreviations: SOL, sleep onset latency; WASO, wake after sleep onset; N1, N2, NonREM sleep stages N1 and N2; SWS, slow-wave sleep; REM, rapid eye movement sleep; TST, total sleep time; TOTAL, total time between sleep onset and “Lights On”; SQ, sleep quality.

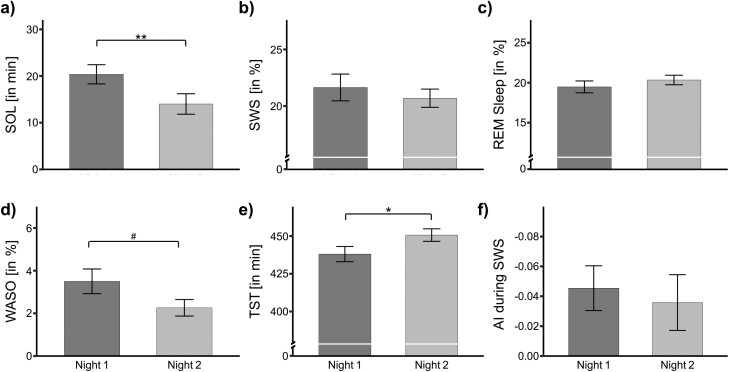

For example, in the adaptation night, participants took an average of 20.37 ± 2.05 min to fall asleep, compared to 14.01 ± 2.19 min in Night 2, F(1, 44) = 8.33, p = .006, ηG2 =.05 (see Figure 2a for pair-wise comparisons). Moreover, TST was significantly shorter in the first night (438.05 ± 5.05 min) compared to the second night (450.65 ± 4.14 min; F(1, 43) = 4.26, p = .045, ηG2 =.04; Figure 2e) as well as TOTAL, which was shorter in the first night (457.99 ± 3.20 min) than in the second night (465.95 ± 2.56 min; F(1, 41) = 4.60, p = .038, ηG2 =.04).

Figure 2.

Sleep parameters during both nights of Study 1 in the sleep laboratory. (a) Sleep onset latency (SOL). (b) Slow-wave sleep (SWS). (c) Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. (d) Wake after sleep onset (WASO). (e) Total sleep time (TST). (f) Asymmetry index (AI) during SWS within the first sleep cycle. Data are means ± SEM. Numbers indicate absolute or relative values.

We also found that during the first night, participants reached the stage of SWS (indicated by the SWS latency) later (15.69 ± 0.97 min) relative to the second night (14.14 ± 0.89 min). This sleep parameter was marked with a trend (F(1, 44) = 3.03, p = .089, ηG2 =.02). In the same vein, we found another trend for WASO, as participants were more awake in the first night than the second night (3.50 ± 0.58% vs. 2.26 ± 0.39%; F(1, 42) = 3.33, p = .075, ηG2 =.04).

Interestingly, no other objective sleep parameters (including the duration of N2, SWS, or REM sleep) showed a significant FNE (Figure 2, b and c), For self-reported sleep parameters (i.e., self-reported SOL, WASO, and SQ), we also found no significant main effects (all p > .165; Table 1).

It is possible that the presleep activity in Study 1 may have had an impact on the participants’ SQ. To exclude this potential bias, we conducted an additional analysis comparing only the adaptation night versus the neutral night of participants who slept in the second night in the neutral condition. This sample consisted of 16 participants. Even in this smaller sub-sample, we continued to find FNE-affected sleep parameters. We still observed statistical trends for TST (F(1, 14) = 4.14, p = .061, ηG2 = .11), SOL (F(1, 15) = 3.14, p = .097, ηG2 = .06), SWS latency (F(1, 15) = 4.36, p = .054, ηG2 = .03), and a significant difference for WASO (F(1, 14) = 5.29, p = .037, ηG2 = .14), In addition, participants spent significantly less time in the sleep stage N2 during the first night than in the second neutral night, F(1, 15) = 5.58, p = .032, ηG2 = .06. For further details (including means ± SEMs), please refer to Supplementary Table S1.

In summary, adaptation nights seem to be beneficial for some sleep stages since SOL, TST, TOTAL, SWS latency, WASO but also N2 sleep appear to be sensitive to FNEs but adapt during a subsequent, nonconsecutive night spent in the sleep laboratory, whereas time spent in SWS appear to be rather unaffected by FNEs.

Study 2

Study 2: better sleep at home than in the sleep laboratory

In Study 2, we examined the impact of the environment (home vs. sleep laboratory) on sleep and FNEs. Participants spent two nonconsecutive nights in their own home environment and two nonconsecutive nights in the sleep laboratory, with the order of home vs. laboratory environment counterbalanced among participants. The mobile recording devices were identical in both sleeping environments. For these analyses, we used ANOVAs including the within factors “Environment” (Home vs. Laboratory) and “Environment Night” (First vs. Second night). Table 2 presents an overview of all sleep parameters, significant main effects, and trends.

Table 2.

Sleep parameters of Study 2 separated by environment

| Sleep parameter | Home | Lab | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Night 1 | Night 2 | Night 1 | Night 2 | |

| Mean±SEM | Mean±SEM | Mean±SEM | Mean±SEM | |

| SOL (min) | 22.86 ± 3.5 | 2 0.1 ± 3.11 | 2 7.52 ± 2.9 | 25.62 ± 3.24 a |

| WASO (%)b | 4.35 ± 0.54 | 3.63 ± 0.58 | 5.65 ± 0.82 | 4.21 ± 0.58 |

| N1 (%)c | 4.81 ± 0.34 | 4.57 ± 0.39 | 5.09 ± 0.39 | 4.44 ± 0.35 |

| N2 (%) | 42.59 ± 1.2 | 43.28 ± 1.28 | 42.73 ± 1.28 | 43.71 ± 1.28 |

| SWS (%) | 24.98 ± 1.01 | 24.19 ± 1.19 | 25.22 ± 1.36 | 25.03 ± 1.17 |

| REM (%) | 2 2.87 ± 0.64 | 2 3.33 ± 0.91 | 2 0.26 ± 0.72 | 21.62 ± 0.64 a |

| SWS Latency (min) | 12.63 ± 0.91 | 12.21 ± 0.77 | 13.71 ± 0.66 | 12.46 ± 0.57 |

| REM Latency (min) | 82.66 ± 5.28 | 78.97 ± 6.26 | 86.78 ± 5.02 | 91.03 ± 6.15 |

| TST (min) | 4 56.5 ± 7.69 | 456.7 ± 8.32 | 428.14 ± 4.73 | 432.14 ± 5.5 a |

| TOTAL (min)c | 473.25 ± 6.81 | 482.95 ± 6.79 | 451.14 ± 3.19 | 453.71 ± 3.34 a |

| TIB (min) | 492.32 ± 6.43 | 494.23 ± 7.77 | 481.05 ± 0.33 | 480.63 ± 0.17 a |

| SE (%) | 90.9 ± 0.9 | 89.9 ± 1.23 | 88.78 ± 0.96 | 89.74 ± 1.12 |

| Self-reported SOL (min)c | 18.22 ± 1.75 | 13.87 ± 1.6 | 20.13 ± 1.73 | 20.27 ± 1.58 a |

| Self-reported WASO (min) | 9.73 ± 1.72 | 8.98 ± 1.6 | 12.72 ± 1.86 | 10.47 ± 1.44 |

| Self-reported SQ (index) | 22.83 ± 1.04 | 24.2 ± 1.2 | 22.37 ± 1.01 | 23.07 ± 1.01 |

Time spent in the different sleep stages during Study 2 presented by the environment condition and number of nights spent in this specific environment. Numbers are means ± SEM (in minutes or percentage). All effects are indicated by bold text.

aSignificant main effect of the factor Environment (p < .05).

bSignificant FNEs in both environments (main effect, p < .05).

cFNEs marked with a trend in both environments (p < .1).

Abbreviations: SOL, sleep onset latency; WASO, wake after sleep onset; N1, N2, NonREM sleep stages N1 and N2; SWS, slow-wave sleep; REM, rapid eye movement sleep; TST, Total sleep time; TOTAL, total time between sleep onset and “Lights On”; SE, sleep efficiency; TIB, time in bed; SQ, sleep quality.

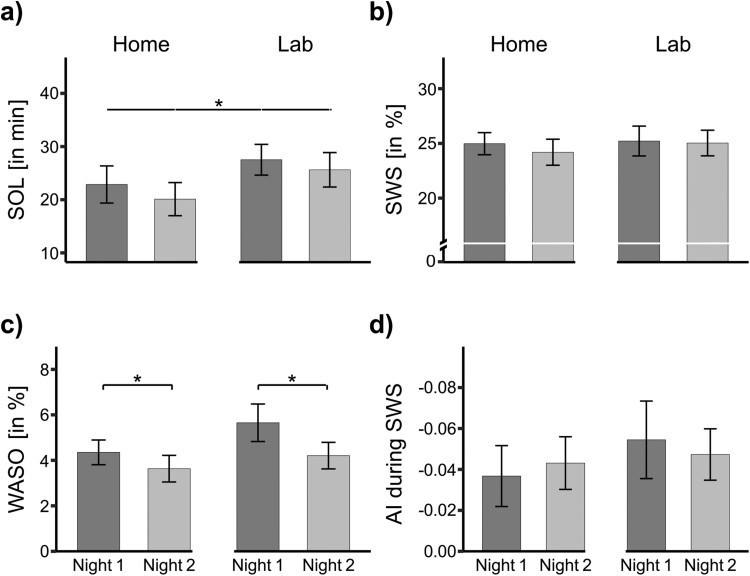

Overall, participants slept better in their home environment than in the sleep laboratory. For example, SOL was significantly shorter when participants slept at home (21.48 ± 2.33 min) compared with the laboratory (26.57 ± 2.16 min, F(1, 28) = 6.47, p = .017, ηG2 =.02; Figure 3a). Furthermore, TST and TOTAL were ca. 25–26 min longer at home compared to the laboratory (both main effects p < .001). The time in bed (TIB) was also significantly different in the two environments (F(1, 27) = 5.25, p = .030, ηG2 =.05). It should be noted, however, that the duration of bedtime in the sleep laboratory was restricted to 8 h, whereas no such restrictions were applied at home. Because participants slept longer, the percentage of REM sleep was also generally higher when participants slept at home (23.10 ± 0.55%) as opposed to in the sleep laboratory (20.94 ± 0.63%; F(1, 27) = 8.58, p = .007, ηG2 =.07).

Figure 3.

Sleep parameters in familiar (Home) vs. unfamiliar (Lab) environment of Study 2. (a) Sleep onset latency (SOL). (b) Slow-wave sleep (SWS). (c) Wake after sleep onset (WASO). (d) Asymmetry index (AI) during SWS within the first sleep cycle. Data are means ± SEM. Numbers indicate absolute or relative values.

We found no further significant influence of the factor Environment on any other objective sleep parameters (all p > .129; Figure 3b; Table 2). Considering the self-reported sleep parameters, we observed that participants reported falling asleep faster at home (16.04 ± 1.21 min) than in the sleep laboratory (20.20 ± 1.64 min; F(1, 29) = 5.68, p = .024, ηG2 =.05). Nonetheless, self-reported WASO and self-reported SQ showed no significant main effects of the environment (p > .173).

Are FNEs modulated by sleeping in a different environment?

In addition to the main effects of the environment reported above, we were interested in the question whether the general increase in SQ between the first and second night in a specific environment would be modulated by the type of environment (home vs. laboratory). Thus, we were specifically interested in the interaction between the factors Environment and Environment Night (First vs. Second night). However, we were not able to find a significant interaction, neither the objective nor the self-reported sleep parameters (all p > .236). We only observed one statistical trend for an interaction between the two factors Environment and Environment Night for self-reported SOL (F(1, 29) = 3.82, p = .060, ηG2 =.02): at home, participants indicated that they fell asleep later in the first night (18.22 ± 1.75 min) compared with the second night (13.87 ± 1.60 min). In the laboratory, self-reported SOL judgments were highly comparable (20.13 ± 1.73 min and 20.27 ± 1.58 min).

As we were not able to observe any significant interaction, FNEs appear to be comparable across different environments. In support of this conclusion, we found several significant main effects of the factor Experimental Night, independent of the actual environment: For example, we observed a significant main effect for WASO (F(1, 26) = 4.32, p = .048, ηG2 =.03): Participants were more awake in the first night (5.00 ± 0.50%) than in the second night, independent of the familiar or unfamiliar sleeping environment (3.92 ± 0.41%; Figure 3c). In addition, the portion of N1 sleep was larger in the first night (4.95 ± 0.26%) than the second night across both environments (4.51 ± 0.26%; F(1, 29) = 3.14, p = .087, ηG2 =.01). Moreover, we observed a trend for shorter TOTAL time in the first night (462.20 ± 4.01 min) than in the second night (468.33 ± 4.24 min; F(1, 27) = 3.15, p = .087, ηG2 =.01). Finally, self-reported SOL tended to be experienced shorter during the second night than during the first night (F(1, 29) = 3.42, p = .075, ηG2 =.01). Other sleep parameters, including objective SOL, TST and SWS latency reported in Study 1, did not reveal significant main effects for FNEs (all p > .131).

In summary, these results indicate that FNEs do not appear to be modulated by different settings as they occur in both unfamiliar and familiar environments. Instead, these analyses reveal that sleep in the second night is generally better than sleep during the first night, irrespective of the environment. This suggests that there is a habituation effect to the polysomnographic setup during the night and that this situational factor plays a crucial role in the development of the FNE.

Does sleeping at home with PSG reduce the FNEs in the sleep laboratory?

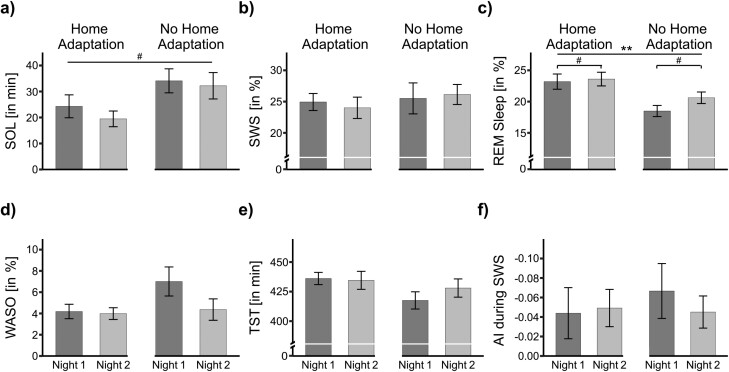

In the next analyses, we specifically addressed the question of whether two nights spent at home with a mobile recording device can reduce FNEs in the sleep laboratory. For this analysis, we only inspected nights spent in the sleep laboratory. We compared two groups of participants: The “Home adaptation” group spent two nights at home using the mobile recording device prior to their first night in the sleep laboratory. The other group slept directly in the lab, without any adaptation at home ("No home adaptation” group). If sleeping at home prior to the two experimental nights would reduce FNEs, we would expect a significant interaction between the factors Experimental Night (First vs. Second) and the factor Group (Home adaptation vs. No home adaptation). However, we observed no evidence for such an interaction (all p > .155). Instead, we observed a main effect marked with a trend for the first vs. the second night in the lab in both groups for REM sleep: Participants spent less time in REM sleep in the first night in the lab (20.76 ± 0.86%) compared with the second night (22.06 ± 0.75%), F(1, 27) = 3.14, p = .088, ηG2 =.03 (Figure 4c). For N1 we also observed a trend for more N1 sleep in Night 1 vs. Night 2 (5.09 ± 0.39% vs. 4.44 ± 0.35%; F(1, 28) = 3.17, p = .086, ηG2 =.03). Thus, FNEs for REM and N1 persisted (at least marked with a trend) regardless of whether two adaptation nights were spent at home or not. Still, we observed a general benefit of spending two adaptation nights at home: participants with home adaptation generally spent more time in REM sleep in the sleep laboratory (23.40 ± 0.80%) than participants without home adaptation (19.55 ± 0.66%, F(1, 27) = 9.13, p = .005, ηG2 =.20; Figure 4c). Moreover, participants with home adaptation had a greater TIB in the sleep lab (481.05 ± 0.22 min) than participants without home adaptation (480.48 ± 1.52 min, F(1, 27) = 5.21, p = .031, ηG2 =.08). Besides that, participants rated the self-reported SOL in the sleep laboratory as generally shorter after home adaptation (17.28 ± 1.71 min) than after no home adaptation (23.12 ± 1.41 min; F(1, 28) = 4.59, p = .041, ηG2 =.11). Additionally, we observed some statistical trends for generally improved sleep in the lab after home adaptation e.g., participants of the Home adaptation group objectively took less time to fall asleep (21.88 ± 2.66 min) than the No home adaptation group (33.15 ± 3.37 min; F(1, 28) = 4.10, p = .052, ηG2 =.11). Finally, TOTAL was longer for participants of the Home adaptation group (457. 08 ± 2.90 min) than for those of the No home adaptation group (446.55 ± 3.40 min; F(1, 28) = 3.37, p = .077, ηG2 =.09). Table 3 provides all values of the sleep architecture.

Figure 4.

Sleep parameters in the unfamiliar (Lab) environment of Study 2, separated by Home adaptation vs. No home adaptation group. (a) Sleep onset latency (SOL). (b) Slow-wave sleep (SWS). (c) Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. (d) Wake after sleep onset (WASO). (e) Total sleep time (TST). (f) Asymmetry index (AI) during SWS within the first sleep cycle. Data are means ± SEM. Numbers indicate absolute or relative values.

Table 3.

Sleep parameters of laboratory nights separated by groups in Study 2

| Sleep parameter | No home adaptation | Home adaptation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lab night 1 | Lab night 2 | Lab night 1 | Lab night 2 | |

| Mean±SEM | Mean±SEM | Mean±SEM | Mean±SEM | |

| SOL (min) | 24.30 ± 4.40 | 19.47 ± 3.02 | 34.10 ± 4.62 | 32.20 ± 5.08 a |

| WASO (%) | 4.19 ± 0.68 | 3.99 ± 0.55 | 7.01 ± 1.37 | 4.36 ± 1.01 |

| N1 (%)b | 4.73 ± 0.55 | 4.41 ± 0.55 | 5.45 ± 0.55 | 4.48 ± 0.45 |

| N2 (%) | 43.46 ± 1.85 | 43.83 ± 1.89 | 41.94 ± 1.80 | 43.58 ± 1.79 |

| SWS (%) | 24.94 ± 1.36 | 24.01 ± 1.71 | 25.51 ± 2.48 | 26.14 ± 1.60 |

| REM (%)b | 23.19 ± 1.22 | 23.60 ± 1.09 | 18.49 ± 0.89 | 20.61 ± 0.92 c |

| SWS latency (min) | 14.36 ± 0.93 | 13.43 ± 0.95 | 12.75 ± 0.82 | 12.04 ± 0.65 |

| REM latency (min) | 81.18 ± 7.40 | 87.32 ± 6.87 | 92.00 ± 6.79 | 94.50 ± 10.17 |

| TOTAL (min) | 455.30 ± 4.36 | 458.87 ± 3.92 | 445.80 ± 4.65 | 447.30 ± 5.13 |

| TST (min) | 436.07 ± 5.17 | 434.53 ± 7.61 | 417.54 ± 7.29 | 428.00 ± 7.73 |

| TIB (min) | 481.29 ± 0.36 | 480.82 ± 0.24 | 480.43 ± 0.21 | 480.53 ± 0.23 c |

| SE (%) | 90.53 ± 1.06 | 90.38 ± 1.59 | 86.90 ± 1.51 | 89.06 ± 1.61 |

| SOL self-reported (min) | 16.87 ± 2.47 | 17.70 ± 2.46 | 23.40 ± 2.20 | 22.83 ± 1.84 c |

| WASO self-reported (min) | 11.37 ± 2.63 | 9.23 ± 2.08 | 14.07 ± 2.66 | 11.70 ± 2.03 |

| SQ self-reported | 23.93 ± 1.58 | 23.60 ± 1.67 | 20.80 ± 1.18 | 22.53 ± 1.19 |

Time spent in the different sleep stages in Study 2 during the laboratory nights only. For the No home adaptation group, the nights in the laboratory are the absolute first and second night within the study. For the Home adaptation group, the laboratory nights follow after the two nights they already spend at home to get familiar with the device. The absolute night number is Night 3 and Night 4. Numbers are means ± SEM (in minutes or in percentage). All effects are indicated by bold text.

aDifference marked with a trend for the factor Group (p < .1).

bFNEs marked with a trend in both groups (p < .1).

cSignificant main effect of the factor Group (p < .05).

Abbreviations: SOL, sleep onset latency; WASO, wake after sleep onset; N1, N2, NonREM sleep stages N1 and N2; SWS, slow-wave sleep; REM, rapid eye movement sleep; TST, total sleep time; TOTAL, total time between sleep onset and “Lights On”; SE, sleep efficiency; TIB, time in bed; SQ, sleep quality.

In conclusion, spending two nights at home tends to improve some sleep parameters for subsequent nights in the sleep laboratory, indicating that some adaptation to the recording equipment occurs. However, home adaptation is not sufficient to eliminate all indices for FNEs in the laboratory.

EEG power spectrum and interhemispheric asymmetry during SWS

In addition to the sleep architecture, we examined the interhemispheric asymmetry activity (IAA) of the delta band (1–4.5 Hz) within SWS of the first sleep cycle throughout the nights. This was done against the background of Tamaki et al. [12], who reported that the IAA in the delta band during SWS is a neural correlate of a “Night Watch System” during sleep and therefore a correlated and potential mechanism of the FNE. We first examined the factor Night in Study 1, to see whether a difference in the AI across the different nights existed or not. Then, we focused our attention on the factor Environment of Study 2. Finally, we examined the relationship between the asymmetry index (AI) and the FNE, as previously investigated in the key study by Tamaki et al. [12], who observed a negative correlation between the AI and the SOL.

We first analyzed the average frontal power (in µV) of the delta (1–4.5 Hz), theta (4.5–8 Hz), alpha (8–11 Hz) sigma (11–15 Hz), and beta (15–25 Hz) bands during SWS within the first sleep cycle of both brain hemispheres. We compared the power of all frontal frequency band activities across all nights for both studies. We also compared occipital delta activity in the first study, as it has been suggested that a reduced SWA power may be involved in the FNE [27]. However, we found no significant differences between any of the nights or environments for the frontal power in any frequency bands for both studies (all p > .132, see Tables 4–6 for Means ± SEMs) and not for the occipital delta power in Study 1 (p > .369). We only observed a trend for frontal sigma power in Study 1 (adaptation night: 0.33 ± 0.02 µV; second night: 0.30 ± 0.02 µV, F(1, 33) = 3.52, p = .069, ηG2 = .11), whereas no such difference occurred in Study 2 (p > .161; see Tables 5 and 6).

Table 4.

Frontal frequency power (in µV) in SWS of the first sleep cycle for Study 1

| Study 1 | Night 1 | Night 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Mean±SEM | Mean±SEM | |

| Frontal delta | 38.49 ± 3.89 | 38.38 ± 3.57 |

| Frontal theta | 2.21 ± 0.18 | 2.16 ± 0.18 |

| Frontal alpha | 0.74 ± 0.06 | 0.69 ± 0.06 |

| Frontal sigma | 0.33 ± 0.02 | 0.30 ± 0.02 |

| Frontal beta | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.03 ± 0.00 |

| Occipital delta | 12.70 ± 1.05 | 13.72 ± 1.09 |

The extracted mean power (in µV) of the delta (1–4.5 Hz), theta (4.5–8 Hz), alpha (8–11 Hz), sigma (11–15 Hz), and the beta band (15–25 Hz) during SWS in the first sleep cycle for each experimental night. We extracted the mean frontal and also occipital delta power during SWS in the first sleep cycle for the first two nights. Numbers are means ± SEM (in µV).

Table 5.

Frontal frequency power (in µV) in SWS of the first sleep cycle for Study 2, separated by environment

| Study 2 | Home | Lab | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Night 1 | Night 2 | Night 1 | Night 2 | |

| Mean±SEM | Mean±SEM | Mean±SEM | Mean±SEM | |

| Frontal delta | 67.65 ± 4.52 | 67.66 ± 4.74 | 66.90 ± 4.95 | 70.10 ± 5.07 |

| Frontal theta | 3.09 ± 0.21 | 3.07 ± 0.18 | 3.09 ± 0.21 | 3.16 ± 0.20 |

| Frontal alpha | 1.50 ± 0.18 | 1.55 ± 0.17 | 1.52 ± 0.18 | 1.61 ± 0.19 |

| Frontal sigma | 0.87 ± 0.08 | 0.93 ± 0.09 | 0.93 ± 0.08 | 0.94 ± 0.08 |

| Frontal beta | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 |

The extracted mean power (in µV) of the delta (1–4.5 Hz), theta (4.5–8 Hz), alpha (8–11 Hz), sigma (11–15 Hz), and the beta band (15–25 Hz) during SWS in the first sleep cycle for each experimental night. We extracted the averaged frontal power during SWS of the first sleep cycle separated by Environment (Home and Lab). Occipital delta was not extracted in Study 2 as no occipital electrodes were available in this study. Numbers are means ± SEM (in µV).

Table 6.

Frontal frequency power (in µV) in SWS of the first sleep cycle for Study 2, separated by group

| No home adaptation | Home adaptation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lab night 1 | Lab night 2 | Lab night 1 | Lab night 2 | |

| Mean±SEM | Mean±SEM | Mean±SEM | Mean±SEM | |

| Frontal delta | 69.32 ± 8.55 | 71.34 ± 9.97 | 64.64 ± 8.42 | 68.95 ± 8.20 |

| Frontal theta | 3.30 ± 0.35 | 3.36 ± 0.34 | 2.91 ± 0.26 | 2.98 ± 0.24 |

| Frontal alpha | 1.53 ± 0.25 | 1.56 ± 0.23 | 1.51 ± 0.26 | 1.66 ± 0.30 |

| Frontal sigma | 0.96 ± 0.11 | 0.99 ± 0.12 | 0.90 ± 0.12 | 0.88 ± 0.11 |

| Frontal beta | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.01 |

The extracted mean power (in µV) of the delta (1–4.5 Hz), theta (4.5–8 Hz), alpha (8–11 Hz), sigma (11–15 Hz), and the beta band (15–25 Hz) during SWS in the first sleep cycle for each experimental night. We extracted the averaged frontal power during SWS of the first sleep cycle separated by Group (Home adaptation and No home adaptation). Occipital delta was not extracted in Study 2 as no occipital electrodes were available in this study. Numbers are means ± SEM (in µV).

In Study 1, we were also unable to detect a significant main effect of the factor Night on the interhemispheric asymmetry (p > .572). Interestingly enough, however, we found a significant intercept (F(1, 34) = 7.70, p = 009, ηG2 = .15), providing evidence for the existence of IAAs in both nights. We found a negative AI, indicating higher SWA power in the right frontal hemisphere compared to the left hemisphere. In Study 1, an AI value of −0.045 ± 0.015 µV was recorded during Night 1, which then decreased to −0.036 ± 0.019 µV in Night 2. We also used one-sample t-test to determine whether the AIs were significantly different from 0. This was the case for Night 1 (t(34) = −3.04, p = .005, d = −0.51), and for Night 2 we detected a trend, t(34) = −1.92, p = .064, d = −0.32, (Figure 2f).

In Study 2, we analyzed the factors Environment and Environment Night on IAAs of delta oscillations during SWS. In the sleep laboratory, the AI value was −0.054 ± 0.019 µV on the first night and on the second night at −0.047 ± 0.013 µV. At home, the AI was at −0.037 ± 0.015 µV and on the second night at −0.043 ± 0.013 µV. Again, except the significant intercept (F(1, 27) = 14.4, p = .001, ηG2 = .25), no main effect or interaction reached significance (all p > .4376). In Study 2, all AIs significantly differed from 0 (Sleep laboratory night 1: t(27) = −2.87, p = .008, d = −0.54; Sleep laboratory night 2: t(27) = −3.77, p < .001, d = −0.71; Home night 1: t(27) = −2.47, p = .020, d = −0.47) except Home night 2: (t(27) = −3.35, p = .002, d = −0.63; Figure 3d).

We also examined whether there was a group difference in IAAs during the nights within the sleep laboratory, but no main effect or interaction became significant (all p > .375), except for a significant intercept indicating a stable presence of asymmetric sleep depth (F(1, 26) = 12.39, p = .002, ηG2 = .27; Figure 4f).

To more accurately describe the stability of asymmetric sleep depth throughout the different nights, we calculated the intraclass coefficient (ICC) to assess the reliability of AIs across all nights for each study separately. For Study 1, a moderate average ICC of 0.504 was found over the course of the two nights within a 95% CI = 0.208 to 0.715 (F(34, 34.4) = 2.99, p < .001). For Study 2, we also observed a moderate degree of reliability between the four nights. The average measure ICC was 0.516 with a 95%CI = 0.329 to 0.7 (F(27, 83.5) = 5.23, p < .001). Between the familiar and unfamiliar sleeping environments, we also observed a moderate degree of reliability: ICC = 0.59 with a 95%CI = 0.288 to 0.787 (F(27, 27.8) = 3.86, p < .001). Lastly, looking at the degree of reliability within the environments, both ICC were moderate (Home: ICC = 0.626, F(27,27.4) = 4.26, p < .001; Lab: ICC = 0.583, F(27,27.3) = 3.72, p < .001). Thus, the IAA may be a partially established trait feature with additional state influences.

Finally, we calculated a Pearson’s correlation coefficient to evaluate the linear relationship between the SOL and the interhemispheric asymmetry in the delta band as reported by Tamaki et al. [12]. However, neither in Study 1 (r(68) = −0.00, p = .977) nor in Study 2 (r(102) = 0.01, p = .949) did we find such a correlation.

Overall, we found no association between frontal or occipital power activity during SWS of the first sleep cycle and any particular night. Moreover, we were able to detect IAAs in the delta band during SWS both in Study 1 and 2, with a higher SWA power in the right brain hemisphere compared to the left hemisphere. This asymmetry was moderately stable across all nonconsecutive nights and across environments in Study 2. Nevertheless, we were not able to find any link between this interhemispheric asymmetry in sleep depth and the FNEs of sleep.

Discussion

In our studies, we examined the nature of FNEs during nonconsecutive nights. Additionally, we also investigated the role of a familiar versus an unfamiliar environment, as well as the potential relationship between FNEs and different settings in regard to the IAA of delta oscillations during SWS.

Our analyses of Study 1 revealed that several sleep parameters of the first night significantly differed from the following night indicating the presence of an FNE, including objective SOL, TST, and total time between sleep onset and lights on (TOTAL). To a lesser extent, the FNE also affected WASO and SWS latency. However, SWS was not affected by an FNE. In Study 2, we also found significant nonconsecutive FNEs for WASO and a weak FNE for sleep stage N1, REM sleep, TOTAL, and self-reported SOL in both familiar and unfamiliar recording environments, with overall greater SQ at home than in the sleep laboratory. Analyses of the delta power showed no significant difference between the nights but the environment and also that the IAA within the delta band (1–4.5 Hz) during SWS revealed a general difference in the presence of IAAs but this was not exclusively associated with a specific night or environment.

Our results are consistent with the meta-analytic findings of Ding et al. [2] for consecutive nights: They report consistent FNEs for SOL, WASO, TST, and other sleep parameters in the first rather than subsequent nights. Generally, more sleep parameters showed FNEs in consecutive nights (as reported in the meta-analysis) compared to our study with nonconsecutive nights. A possible explanation is the age of our participants: Ding et al. [2] recognized that young participants had only modest FNEs, which is consistent with our findings in young participants. A second explanation for the greater FNEs on consecutive nights as compared to nonconsecutive nights may be due to direct rebound effects that occur on a second night immediately following a first night of impaired sleep due to an unfamiliar environment [2]. Thus, nonconsecutive adaptation nights may even be helpful in obtaining more habitual sleep patterns in the sleep laboratory. The meta-analysis by Ding et al. [2] also detected no differences in the degree of FNEs between home and lab studies. This fits well with our findings in Study 2 in familiar and unfamiliar environments, suggesting that an adaptation night is still necessary even when the study is conducted in a familiar environment. Thus, the best option to minimize FNEs is still to adapt to the same recording environment as the actual sleep study is taking place. Nevertheless, adaptation nights at home resulted in a more general improvement in sleep parameters during the first and second night of recording in the laboratory, irrespective of the FNE in the lab. Therefore, adaptation nights at home may improve subsequent SQ in a more general way in the sleep laboratory, possibly allowing for a general adaptation to the recording situation with electrodes, cables, and other equipment.

Interestingly, in our two studies, some sleep parameters (e.g. SWS) were not affected by FNE and remained relatively stable over the nights. Also in consecutive nights, Ding et al. [2] reported no FNEs for SWS and N2. If sleep studies have focus only on SWS and do not focus on SQ per se, an adaptation night may be omitted in these particular sleep studies.

Although many sleep parameters showed the expected effects of the first night, we were unable to show that these adaptation processes were correlated with changes in specific frequency band power or IAAs in the delta band during SWS of the first sleep cycle. Our analyses showed a general difference in the presence of IAAs in both studies over several nights and also between familiar and unfamiliar environments, which is incompatible with the findings and hypothesis reported by Tamaki et al. [12]. However, please note that Tamaki et al. [12] detected IAAs using magnetoencephalography to localize IAAs and focused only on brain networks including the default mode network. Furthermore, the medium stability (as indicated by the ICC) of the IAA across nights, suggests that a few stable trait components may underlie IAAs in the delta band during SWS. Interestingly, some researchers have suggested that structural differences such as the integrity of the corpus callosum may underlie interhemispheric asymmetries in slow-wave activity [14, 15]. In addition to these trait influences, the moderate ICCs in our study indicate that some state aspects also have an influence on the IAA, but these state aspects do not appear to be related to concepts of “familiarity” or FNEs.

Our study has some limitations and drawbacks. As mentioned in Methods section, we obtained the data of Experiment 1 from two independent sleep studies which had an identical design but differed in aim, research questions, and experimental conditions (more details about conditions provided in the Supplementary Information and in [16, 17]). However, we consider this limitation to be minor, as the results of a subgroup analysis including 16 participants who all had only neutral nights (without intervention) after the adaptation night revealed relatively comparable results (Supplementary Information). A limitation of Study 2 is that the bedtime restriction of 8 h in the sleep lab was not applied in the home environment. Consequently, the significant effects of TST, TOTAL, and TIB may be due to this restriction. Moreover, we cannot exclude the possibility that the other sleep parameters were also affected by this free choice of sleep opportunity within the home environment. Additionally, the sex ratio in our samples was unbalanced, which casts doubt on how broadly applicable the findings are. Furthermore, the negative finding that the environment did not moderate FNEs, together with some nonsignificant interactions, may be attributed to the relatively small sample size. Moreover, we used only a minimal set of two electrodes, which makes it difficult to pinpoint the location of asymmetric activity given the already poor spatial resolution of the EEG. Finally, we used a very liberal and conservative testing strategy to analyze our data. While we minimize the risk of excluding false-negative cases, our strategy also carries the potential for an increased number of acceptances of more false positives. Therefore, general comparisons between the studies should be interpreted with caution.

Taken together, the results of our two experiments highlight the importance of including an adaptation night in sleep studies with nonconsecutive nights, ideally in the same environment as the later experimental nights. In addition, our findings indicate that familiarity with the environment may not be sufficient to attenuate an FNE, as FNEs also occur in a home environment. Based on our data, it seems unlikely that home adaptation nights can completely replace sleep lab adaptation nights. Nevertheless, additional adaptation nights at home may be beneficial to improve SQ in the laboratory. To provide a complete clarification of this question, future studies would need to directly compare two to three experimental nights with an adaptation night at home or in the laboratory.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at SLEEP online.

Acknowledgments

We thank Niveettha Thillainathan, Maxine Heft, Liv Roth, and Finn Riedel for helping with the data collection.

Contributor Information

Anna Zoé Wick, Department of Psychology, University of Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland.

Selina Ladina Combertaldi, Department of Psychology, University of Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland.

Björn Rasch, Department of Psychology, University of Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland.

Funding

This study was conducted at the University of Fribourg, Department of Psychology, Division of Cognitive Biopsychology and Methods. This work was supported by a grant of the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement number 667875).

Disclosure Statement

Financial Disclosure: none.

Non-Financial Disclosure: none.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed in this article are available online in Open Science Framework (OSF) at https://osf.io/5fmsp/.

References

- 1. Agnew HW, Webb WB, Williams RL.. The first night effect: an EEG study of sleep. Psychophysiology. 1966;2(3):263–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1966.tb02650.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ding L, Chen B, Dai Y, Li Y.. A meta-analysis of the first-night effect in healthy individuals for the full age spectrum. Sleep Med. 2022;89:159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lee DH, Cho CH, Han C, et al. Sleep irregularity in the previous week influences the first-night effect in polysomnographic studies. Psychiatry Investig. 2016;13(2):203–209. doi: 10.4306/pi.2016.13.2.203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sprajcer M, Gupta C, Roach G, Sargent C.. Can we put the first night effect to bed? An analysis based on a large sample of healthy adults. Chronobiol Int. 2022;39(12):1567–1573. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2022.2133611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Le Bon O, Staner L, Hoffmann G, et al. The first-night effect may last more than one night. J Psychiatr Res. 2001;35(3):165–172. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(01)00019-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Johns MW, Doré C.. Sleep at home and in the sleep laboratory: disturbance by recording procedures. Ergonomics. 1978;21(5):325–330. doi: 10.1080/00140137808931730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Newell J, Mairesse O, Verbanck P, Neu D.. Is a one-night stay in the lab really enough to conclude? First-night effect and night-to-night variability in polysomnographic recordings among different clinical population samples. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200(2-3):795–801. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.07.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lorenzo JL, Barbanoj MJ.. Variability of sleep parameters across multiple laboratory sessions in healthy young subjects: the “very first night effect.”. Psychophysiology. 2002;39(4):409–413. doi: 10.1111/1469-8986.3940409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thornby JI Mauk JL, Karacan I.. A further examination of the adjustment/readjustment-night phenomena. Sleep Res. 1979;8(152). [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stepanski E, Roehrs T, Saab P, Zorick F, Roth T.. Readaptation to the laboratory in long-term sleep studies. Bull Psychon Soc. 1981;17(5):224–226. doi: 10.3758/bf03333720 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Scharf MB, Kales A, Bixler EO.. Readaptation to the sleep laboratory in insomniac subjects. Psychophysiology. 1975;12(4):412–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1975.tb00013.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tamaki M, Bang JW, Watanabe T, Sasaki Y.. Night watch in one brain hemisphere during sleep associated with the first-night effect in humans. Curr Biol. 2016;26(9):1190–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.02.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Armitage R, Hoffmann R, Loewy D, Moffitt A.. Variations in period‐analysed EEG asymmetry in REM and NREM sleep. Psychophysiology. 1989;26:329–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1989.tb01928.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Roth C, Achermann P, Borbély AA.. Frequency and state specific hemispheric asymmetries in the human sleep EEG. Neurosci Lett. 1999;271(3):139–142. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00048-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Avvenuti G, Handjaras G, Betta M, et al. Integrity of corpus callosum is essential for thecross-hemispheric propagation of sleep slow waves: a high-density EEG study in split-brain patients. J Neurosci. 2020;40(29):5589–5603. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2571-19.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Combertaldi SL, Rasch B.. Healthy sleepers can worsen their sleep by wanting to do so: the effects of intention on objective and subjective sleep parameters. Nat Sci Sleep. 2020;12:981–997. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S270376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Combertaldi SL, Ort A, Cordi M, Fahr A, Rasch B.. Pre-sleep social media use does not strongly disturb sleep: a sleep laboratory study in healthy young participants. Sleep Med. 2021;87:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Griefahn B, Künemund C, Bröde P, Mehnert P.. Zur validität der deutschen übersetzung des morningness-eveningness-questionnaires von Horne und Östberg. Somnologie. 2001;5:71–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-054x.2001.01149.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ.. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Steyer R, Notz P, Schwenkmezger P, Eid M.. Der Mehrdimensionale Befindlichkeitsfragebogen MDBF. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Görtelmeyer R. SF-A/R und SF-B/R: Schlaffragebogen A und B. 2011. http://ub-madoc.bib.uni-mannheim.de/29052. Accessed June 21, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chatrian GE, Lettich E, Nelson PL.. Ten percent electrode system for topographic studies of spontaneous and evoked EEG activities. Am J EEG Technol. 1985;25(2):83–92. doi: 10.1080/00029238.1985.11080163 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson A, Quan SF.. The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: Rules, terminology and technical specification. Version 1. 1st ed.Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ackermann S, Hartmann F, Papassotiropoulos A, de Quervain DJF, Rasch B.. No Associations between interindividual differences in sleep parameters and episodic memory consolidation. Sleep. 2015;38(6):951– 959. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Blume C, Cajochen C.. ‘SleepCycles’ package for R - A free software tool for the detection of sleep cycles from sleep staging. MethodsX. 2021;8:101318. doi: 10.1016/j.mex.2021.101318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria. 2023. https://www.r-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tamaki M, Won Bang J, Watanabe T, Sasaki Y.. The first-night effect suppresses the strength of slow-wave activity originating in the visual areas during sleep. Vision research. 2013;99:154-161. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2013.10.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in this article are available online in Open Science Framework (OSF) at https://osf.io/5fmsp/.