Abstract

Prior studies have shown strong genetic effects on cortical thickness (CT), structural covariance, and neurodevelopmental trajectories in childhood and adolescence. However, the importance of genetic factors on the induction of spatiotemporal variation during neurodevelopment remains poorly understood. Here, we explore the genetics of maturational coupling by examining 308 MRI-derived regional CT measures in a longitudinal sample of 677 twins and family members. We find dynamic inter-regional genetic covariation in youth, with the emergence of regional subnetworks in late childhood and early adolescence. Three critical neurodevelopmental epochs in genetically-mediated maturational coupling were identified, with dramatic network strengthening near eleven years of age. These changes are associated with statistically-significant (empirical p-value <0.0001) increases in network strength as measured by average clustering coefficient and assortativity. We then identify genes from the Allen Human Brain Atlas with similar co-expression patterns to genetically-mediated structural covariation in children. This set was enriched for genes involved in potassium transport and dendrite formation. Genetically-mediated CT-CT covariance was also strongly correlated with expression patterns for genes located in cells of neuronal origin.

Subject terms: Brain, Behavioural genetics, Dynamical systems

Schmitt et al. studied the genetics of maturational coupling via longitudinal models of cortical thickness in N=677. Genetic correlations were dynamic. Patterns resembled expression of genes associated with potassium channels and dendrite formation.

Introduction

The human cerebral cortex is highly dynamic in youth1,2. From mid-childhood to early adulthood, maturational changes in cortical volumes are primarily driven by cortical thickness (CT)3. Longitudinal studies using MRI have found rapid increases in CT in the newborn period4,5, followed by more protracted and generally monotonic decreases in CT over later childhood and adolescence3,6–8. These global trends are underpinned by considerable spatial variability in rates of change in CT across the cortical sheet. For example, adolescence is a period of accelerated thinning in the lateral frontal lobes, but decelerating thinning in occipital regions3. There is also evidence that peri-Sylvian and peri-calcarine cortex have less pronounced thinning relative to other areas3,8,9. In general, cortical maturation proceeds along a posterior to anterior gradient, first involving primary sensory cortex, with subsequent maturation of association areas10.

While longitudinal studies have provided important insights into how CT changes with age, these univariate analyses do not directly consider the complex spatial interactions between brain regions. Multivariate investigations into structural covariance have characterized the cross-region neuroanatomic relationships in cross-sectional samples, finding reproducible and scientifically plausible networks in typically-developing samples across the lifespan11–14. For example, a study of structural covariance patterns in a series of four distinct child and adolescent cohorts (total age range 4.9–18.0) found that cortical networks are small and initially limited to adjacent structures and contralateral homologs; primary and sensory cortical networks subsequently emerge, followed by higher-order networks15. While many canonical networks appear to progressively increase in size with age, the spatial extent of many networks (e.g. visual, auditory, and the default mode network) experience their peak near 13 years of age, with subsequent pruning during late adolescence – ultimately resembling networks of young adults.

By examining dynamic changes in cross-regional covariance over time (i.e. combining the longitudinal and multivariate analytic approaches described above), the coordinated spatiotemporal patterns of CT changes over neurodevelopment, i.e. maturational coupling, can be investigated9. This work has found that correlational patterns of CT change are weak in neonates and strengthen in toddlerhood16. Across adolescence, maturational coupling is strongest in the fronto-temporal association cortex, and weakest in primary sensory cortex9. Peak network connection strength and nodal density is observed at ~9.5–11.5 years of age, followed by reductions in network strength in late childhood17. Weakening network strength continues into early adulthood18. Prior studies have found that patterns of maturational coupling, structural covariance, and functional networks are similar9,19,20.

In an independent thread of research, prior quantitative genetic analyses using twin samples have found that numerous structural neuroimaging phenotypes are significantly heritable21. For example, genetic influences on cerebral gray matter are detectable even in neonates22, and the heritability of cortical gray matter increases in older children23. Our prior work on NIMH’s Intramural Longitudinal MRI Study of Human Brain Development24,25 found regionally-specific variation in in the heritability of CT, with stronger genetic effects observed in more evolutionarily-novel regions25. Analysis of CT-CT structural covariance between gyral-level regions of interest (ROIs) in this sample found a strong shared global genetic factor that influences CT throughout the brain, but regionally-specific genetic factors are also critical in local cortical patterning26. When examining CT at high spatial resolution (40,962 vertices), genetically mediated associations with global mean CT were strongest in association cortex, and genetic factors were dominant in explaining the covariance between cerebral hemispheres (e.g. between contralateral homologs)27.

There is emerging evidence that genetic factors also influence the longitudinal trajectories of brain growth2,28–30. When examining the NIMH longitudinal sample using genetically informative latent growth curve models, we previously found that the genetic influences on CT in youth are highly dynamic2. Both genetic and environmental variance decreases with age, while heritability generally increases due to smaller reduction in genetic variance. The areas of greatest change correspond to more evolutionarily novel cortical regions2. However, the role of genetics on maturational coupling in youth (i.e. examining genetic, multivariate, and longitudinal information simultaneously) remains relatively unexplored. Cortical thickness is influenced by numerous factors including cellular density, cell size, dendrite formation, synaptogenesis, and cortical myelination31–35; these are all presumably influenced by genetic effects. Following early neurodevelopment, shared trophic factors and functional activity may induce maturational coupling, subsequently leading to more stable structural covariance patterns following early neurodevelopment. We have previously investigated the genetics of maturational coupling at the lobar-level using genetically informative, multivariate, longitudinal models, finding dynamic changes in CT-CT covariance over childhood and adolescence in 16 large cerebral ROIs36.

The current study expands on this prior work, fusing longitudinal, multivariate, and quantitative genetic models in order to explore the genetics of CT maturational coupling at significantly higher spatial resolution in a large MRI dataset of child and adolescent twins and families. Using these models, we probe several critical questions on the genetics of cortical development. First, we quantify the genetically-mediated patterns of structural covariance between cortical regions in youth. Second, we exploit the longitudinal nature of our data to model trajectories of CT-CT genetic correlations over time, and subsequently explore how age influences brain network cohesion. Third, we identify critical genetically-mediated maturational epochs in CT-CT maturational coupling. Finally, we fuse our results with extant transcriptional data from the Allen Human Brain Atlas (AHBA) in order to identify gene sets with similar expression patterns to the CT-CT genetic correlational patterns we observe in youth.

Results

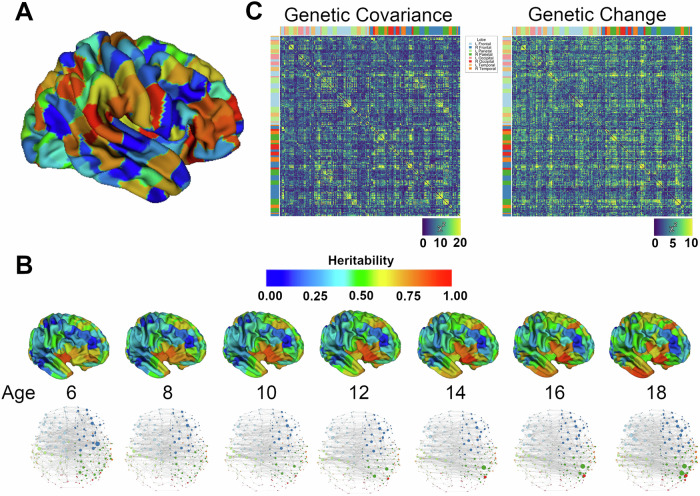

Dynamic genetic effects on CT variance and maturational coupling

Longitudinal, multivariate quantitative genetic models identified dynamic changes in genetic influences on the thickness of 308 cortical regions (Fig. 1A) over childhood and adolescence. In general, heritabilities (i.e. the proportion of phenotypic variances attributable to additive genetic effects) were highest in the inferior frontal gyri, superior frontal gyri, temporal pole, and insula (Fig. 1B). Regional estimates of CT heritability generally increased over childhood and adolescence. Genetically-mediated structural connectivity also changed substantially over childhood (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Movies). At younger ages (e.g., 5 years), there were already relatively strong regionally-specific (e.g. lobar) genetic correlations, but over time these local relationships tended to strengthen, while associations with more spatially distant ROIs generally weakened. The result was increasingly localized and more tightly coupled networks over the age range, particularly in late childhood and adolescence. In later childhood, strong network hubs emerged in the right parietal and posterior frontal lobes. Spectral clustering revealed the most striking in changes in genetically mediated ROI community membership between 10 and 15 years of age (Fig. S1).

Fig. 1. Genetic influences on cortical thickness in youth.

A Example of the 308 cortical parcellations used to measure regional thickness; color assignments were randomly generated. B Dynamic changes in the influence of genetic factors on cortical thickness. Brain maps display maximum likelihood (univariate) heritability for seven equally-spaced timepoints, while brain graphs display genetic correlations >0.80, with nodes colored by lobe and with node size proportional to its degree. The dynamic changes in genetically mediated maturational coupling can also be appreciated in the supplemental movies. C Statistical significance of additive genetic effects on CT-CT covariation. The matrix on the left plots χ2 comparing the full model to one without any genetic effects on CT-CT covariance (df=6), while the matrix on the right displays χ2 for genetic change (df=5), while allowing for main effects of genes on total ROI covariance.

The statistical significance of ROI-ROI genetic covariance is shown in Fig. 1C (Supplementary Data). Strong additive-genetic covariances were observed between nearby ROIs, with patterns generally replicating lobar anatomy based on genetic covariances alone (e.g. blocks of high correlations along the main diagonal). There were strong shared genetic effects between contralateral homologs. Genetically-mediated maturational couplings over the age range were, in some ways, similar to absolute genetic effects, with relatively strong coupling between ROIs in the same cerebral lobe. ROIs in the bilateral frontal cortices had relatively strong genetically-mediated changes with many ROIs elsewhere in the brain.

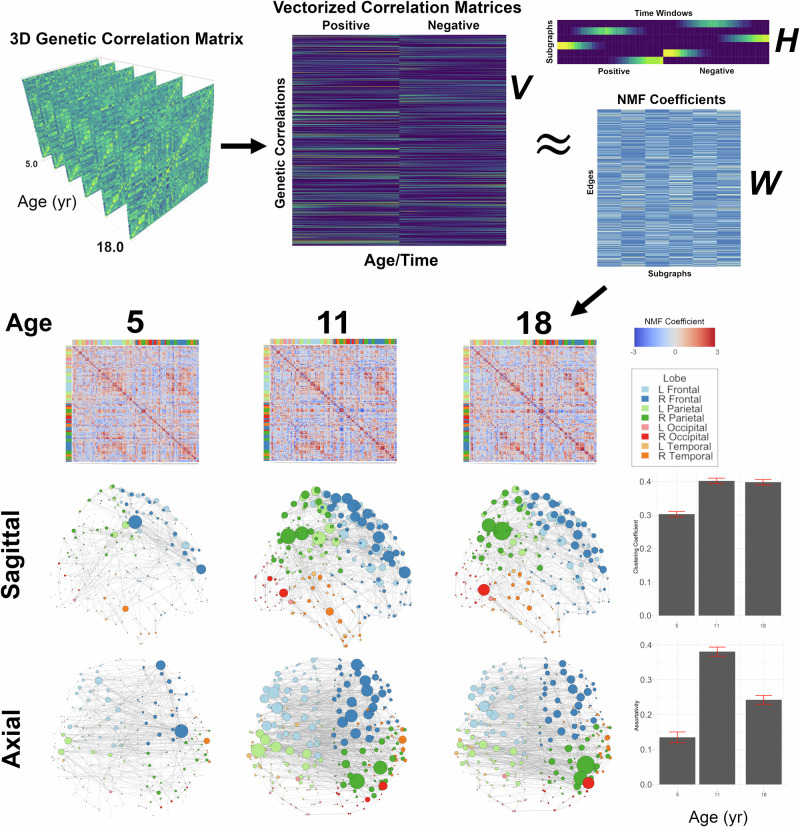

Identification of critical maturational epochs in CT-CT covariance

We then applied non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) to the 3D genetic correlation matrix. NMF is a machine learning technique that can be used cluster timeframes with similar spatial features. Results are summarized in Fig. 2. Three critical maturational epochs were identified near 5, 11, and 18 years of age. Between ages 5 and 11, there was a substantial increase in the number of strong genetic correlations (rG > 0.8), largely driven by increases network strength in the frontal and parietal lobes (Figs. 2 and S2). The right cerebrum had somewhat stronger genetically mediated structural connectivity relative to the left. There were statistically significant increases in both global clustering coefficient (Δ = 0.10, empirical p-value < 0.0001) and assortativity (Δ = 0.25, empirical p-value <0.0001) between 5 and 11 years of age. Differences between ages 11 and 18 were more subtle, with generally weaker genetic correlations, but focally stronger network hubs in the right parietal lobe. Global clustering coefficient was comparable between ages 11 and 18, but assortativity significantly decreased in late adolescence (Δ = −0.14, empiric two-p-value <0.0001). Similar findings persisted over all levels of network sparsity (Supplementary Figs. S3–S6).

Fig. 2. Identification of neurodevelopmental epochs in cortical thickness patterning using non-negative matrix factorization (NMF).

The 3D genetic correlation matrix was first transformed by vectorizing correlations from each timepoint. The matrix was constrained to be non-negative by dividing the data in to two segments, one with the positive values (zero if the correlation was originally negative), and the second with the absolute value of the negative correlation (zero if originally positive). NMF was then applied to generate matrices containing edge coefficients (W) and the temporal information on the temporal strength of each subgraph (H). The coefficient matrix was then reorganized into 3 subgraphs temporally peaking at ages 5, 11, and 18 years. Graph models of genetically mediated network architecture were then constructed (displayed graphs have density = 1%). Corresponding global network statistics with 95% confidence intervals are also provided (bottom right, see also Figs. S3–S6).

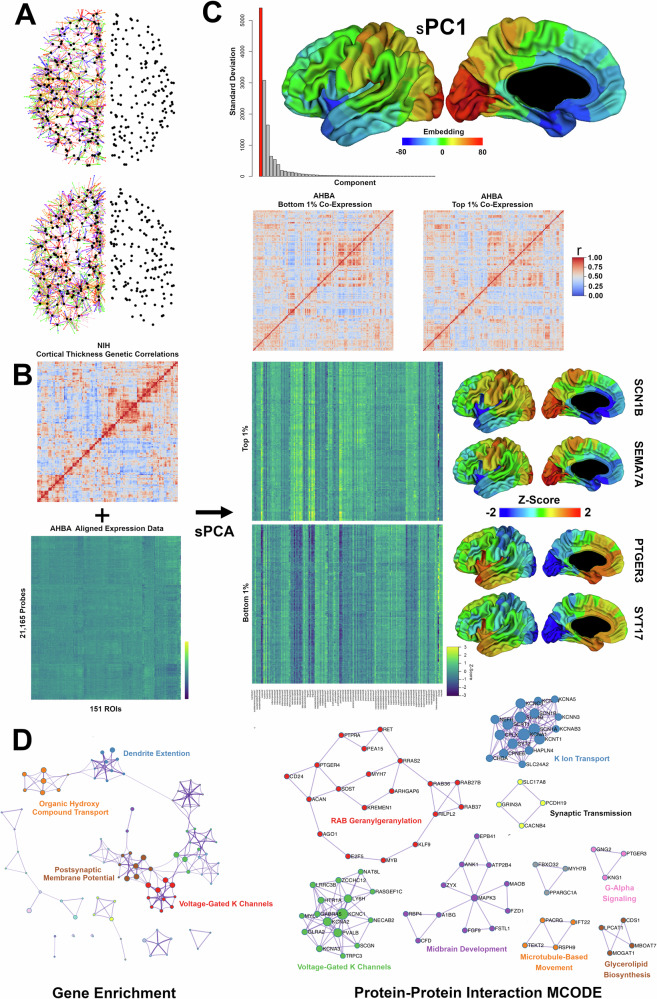

Neuronal gene expression parallels CT genetic correlations in youth

We then used our CT-CT genetic correlation matrix as a probe to identify genes in AHBA with similar co-expression patterns, via supervised principal components analysis (sPCA). Results are provided in Fig. 3. The dominant factor (sPC1) explained over 70% of the total variance in gene expression (Fig. 3C). Embeddings on this component had a strong anterior-posterior gradient, with strongest absolute values found in the occipital cortex, near the temporal poles, and in the anterior cingulate. Co-expression matrices based on those genes with the top and bottom 1% of factor loadings (Supplementary Data 1 and tab Table S1) were strikingly similar to the original CT-CT genetic correlation matrix. When comparing specific spatial gene expression between the top and bottom gene candidates, expression patterns were near mirror images of one another. This finding was confirmed when examining spatial expression patterns for specific genes with the highest (e.g. SCN1B, SEMA7A) and lowest (e.g. PTGER3, SY17) factor loadings.

Fig. 3. Associations between genetically-mediated CT covariance and gene co-expression patterns.

A Co-registration of data from the Allen Human Brain Atlas (AHBA) to 152 left-sided ROIs from our sample. The black dots represent MNI centroids for twin CT data, while the colored dots indicate the location of AHBA samples (colors correspond to individual subjects) and with lines indicating nearest neighbor connections. B Supervised PCA (sPCA) input. C Results from sPCA Scree barplot with dominant component (sPC1) highlighted in red. The embedding map for PC1 is also shown. Gene co-expression correlation matrices for the 2% of genes with the strongest loadings on PC1 are shown, as well as gene expression Z-scores for each ROI separately. Whole-brain expression maps for several genes with the strongest factor loadings (e.g. SCN1B, PTGER3) are also shown. D Gene enrichment and protein-protein interaction networks based on Metascape analysis of the top 2% of genes associated with sPC1.

Gene enrichment analysis (Fig. 3D) found that those genes with strongest factor loadings on sPC1 were significantly enriched for voltage-gated potassium channels (-log p-value = 7.24, q-value = 0.0013), with greater than 11-fold enrichment relative to background, and with our gene set including nearly 25% of all genes in the voltage-gated potassium channel Reactome ontology (Fig. S7). Genes involved in dendrite extension also were significantly enriched (-log p-value 4.15, q-value 0.0199) and included two semaphorins (SEMA7A and SEMA4F), NOTCH1, and monoamine oxidase (MAOB). Protein-protein interaction analyses found significant enrichment in neuronal systems (−log p-value = 12.0, q-value < 0.0001). The largest MCODE subnetworks were involved in potassium ion transport, voltage-gated potassium channels, and midbrain development (Fig. 3D, Supplementary Data 1, and tab Table S2). Post hoc analysis found that spatial patterns of sPC1-derived median gene expression were moderately correlated with both excitatory (r = 0.67) and inhibitory (r = 0.62) neuron gene sets, and were more weakly correlated with gene sets from glial cell types (all r < 0.35) (Fig. S8). ROI-ROI gene co-expression maps for both excitatory and inhibitory neurons were similar to sPCA regional co-expression patterns; out of all cell-derived sets, neuronal sets had the strongest similarities to sPC1 gene co-expression (empirical p-value <0.0001).

Discussion

The current study investigates the genetics of maturational coupling at high spatiotemporal resolution. We find dynamic patterns of CT-CT genetic correlational relationships throughout youth, with general trends towards increased regional specificity and the emergence of strong network hubs in frontoparietal regions in later childhood and adolescence. In early childhood, we find widespread and relatively uniform genetic correlations throughout the cerebral cortex, possibly due to shared global genetic effects influencing the entire cortex early in life (i.e., in the fetal period, or very early childhood). We also found strong genetic correlations between ROIs and their contralateral homologs over the study interval, a finding also observed in multiple samples over the entire lifespan; these correlations appear well-established by age 5 and persist at least into early adulthood. In contrast, we find profound increases in genetically-mediated regional connectivity over this age range. Our findings suggest that not only are the genetic influences on CT highly dynamic in childhood, but the evolving patterns of structural correlations also are highly influenced by changes in shared additive genetic factors.

The importance of genetics on maturational coupling has been previously hypothesized9,37. Patterns of gene expression in mouse models predict emergent patterns of structural covariance38,39. In humans, genetic, structural, functional, and maturational covariance maps show clear neuroanatomic similarities with one another26,20. Neurodevelopmental trajectories in cortical thinning over the lifespan have been shown to predict genetic structural covariance in middle age, and are remarkably similar to patterns of cortical thinning in older adults40. Our observed dynamic correlational patterns in youth resemble patterns of spatiotemporal brain dynamics previously reported in childhood and adolescence in postmortem samples41.

It has been postulated that cortical networks develop through distinct connectivity milestones42. Global structural network strength rapidly increases in early childhood, peaking in the beginning of the second decade of life17, and with subsequent weakening more gradually throughout adolescence18. We find similar patterns to those reported previously, although our data suggest that these changes in network strength are largely genetically mediated. We additionally report evidence of three distinct neurodevelopmental epochs in youth, based on the observed dynamic genetic correlational patterns, with particular changes in network structure observed late childhood near 11 years of age. Like prior studies, we find that average ROI degree, global clustering coefficient, and assortativity all dramatically increase during this time period. Although many neurodevelopmental processes wane by the second decade of life, late childhood and early adolescence are a period of active synaptic pruning43 and cortical myelination44. Our study provides further evidence that many of these changes are driven by shared additive genetic factors influencing spatiotemporal variation in CT-CT neurodevelopmental trajectories. Prior phylogenetic research has found periods of relative genetic convergence during mid embryogenesis, with divergence before and after this timepoint (i.e., the “hourglass” model of development), likely owed to evolutionary constraints at critical neurodevelopmental epochs45,46. A similar hourglass-shaped transcriptional profile has been observed for gene expression in the brain in human youth during fetal development47. These periods of relative genetic constraint could potentially explain some of our observed patterns of genetically-mediated CT-CT covariance in youth. Although temporally preceding the peak age of onset of most childhood psychiatric disorders by a few years48, the dramatic changes in structural networks that we observe during this time period may explain the genetic liability to these conditions49, as well as to their genetically-mediated comorbidities.

Finally, we identify gene sets with expression profiles that replicate CT genetic correlational patterns in youth. Prior studies have found that cortically-based transcriptional and structural covariance networks have similar properties50. Using sPCA to combine these data, we identify a dominant genetic factor with a clear anterior-posterior gene expression gradient. This finding mirrors previous work showing a dominant genetically-mediated anterior-posterior gene expression gradient in the cerebral cortex51,52, as well as paralleling known patterns of neurodevelopmental changes in the cerebral cortex observed over youth8,53. We found that the genes with the strongest loadings on this factor all had very strong anterior-posterior expression profiles when examined individually. The spatial co-expression pattern of our AHBA gene set was also remarkably similar to the CT genetic correlation matrix, and was particularly enriched for genes involved in potassium transport. Thus, variation in potassium transport may contribute to individual differences in CT in youth. Cortical thinning during adolescence has been associated with expression patterns of S1 pyramidal cells; these cells in turn have increased expression of potassium channels54. Genetic variation in potassium transport may induce spatiotemporal variation intracellular potassium levels, which is associated with apoptosis55. Ion channels and transporter gene expression have also been prominently associated with cortical volumes56 and resting state functional connectivity57,58. Genes involved in dendrite extension were also significantly enriched in our analysis. Cortical thickening in adolescence is associated with CA1 pyramidal cell expression profiles, which in turn are enriched in gene ontologies associated with neuroplasticity, particularly dendrite extension54. Our observations of strong similarities in regional gene co-expression between CT-associated genetic effects and neuron-expressed gene sets supports this hypothesis.

Limitations

There are several limitations to the current study that must be considered when interpreting these findings. First, the sample size is modest by the standards of quantitative genetic analysis. The presence of multivariate longitudinal data and continuous measures both ameliorate this issue; larger genetically informative longitudinal studies such as the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study will likely provide additional insights in the near future59. Second, as inherently based on a twin paradigm, our principal analyses inherit all the assumptions of this design, most notably the assumption of an equal shared environment for MZ and DZ twins, at least with respect to non-elicited factors influencing the phenotypes measured (i.e. CT). Additional assumptions include random mating, no non-additive genetic variation, no significant G-E covariance, and no G x E interaction. Third, due to the complex computational nature of these models, we do not explicitly test for shared environmental effects in this study. However, it is noteworthy that we did not find shared environmental influences in our prior work on maturational coupling in a similar sample (albeit using substantially larger ROIs36). Fourth, we exclusively used the CIVET pipeline for image processing, which increases the risk of methodologically specific results; although prior work has shown comparable measurements of CT across common image-processing pipelines, there are some notable pipeline-specific differences, for example in paralimbic and mid-occipital regions using CIVET60. However, we would expect these differences to have a relatively small effect on the current study given its focus on longitudinal changes and within-family covariance, rather than absolute measures of CT relative to a gold standard. Temporal changes in scanner settings could also potentially contribute to observed variation over time61. Fifth, the unusual nature of the NIH longitudinal Twin MRI dataset makes direct replication in independent samples challenging; replication of this work in ABCD and other samples will be important. Sixth, the AHBA data was obtained on adults rather than children, and variations in gene expression over age are not accounted for; this was the principal rationale for examining only spatial (rather than spatiotemporal) correlates with AHBA and our data, although in principle trajectories of genetically-mediated change could also be investigated. The role of environmental influences on gene expression, gene x environment interactions, and the potential differential environmental effects between the NIH and AHBA samples were also not examined. Additionally, by using the entire CT-CT genetic correlation matrix as a probe, our analysis did not investigate potential regionally-specific transcriptional variation in cortical subnetworks; this could represent a potential future research direction.

Methods

Subjects

677 typically developing children, adolescents and young adults from 382 families were recruited at the Child Psychiatry Branch of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), as part of the Longitudinal MRI Study of Human Brain Development53. The sample included pediatric, adolescent, and young adult monozygotic twins (MZ, N = 183), dizygotic twins (DZ, N = 75), siblings of twins (N = 71), and singleton (N = 232) family members (summarized in Table 1, Fig. S9). Parents of prospective participants were interviewed by phone and asked to report their child's health, developmental, and educational history. Subjects were excluded if they had taken psychiatric medications, had been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder, had undergone brain trauma, or had any condition known to affect gross brain development. Inclusion criteria were a minimum gestational age of 29 weeks and a minimum birth weight of 1500g. Approximately 80% of families responding to the ads met inclusion criteria. For twin subjects, zygosity was determined by DNA analysis of buccal cheek swabs using 9–21 unlinked short tandem repeat loci for a minimum certainty of 99%, by BRT Laboratories and Proactive Genetics. We obtained verbal or written assent from the child and written consent from the parents for their participation in the study. The Combined Neurosciences Institutional Review Board (CNS-IRB) at the National Institutes of Health approved the protocol. All ethical regulations relevant to human relevant to human research participants were followed.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample

| MZ | DZ | Siblings of twins | Singletons | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 222 | 101 | 84 | 270 | 677 |

|

Mean age at first scan (years SD) |

8.6 (3.7) | 7.4 (3.6) | 9.7 (4.3) | 9.1 (5.2) | 8.7 (4.5) |

|

Mean scan interval (years SD) |

2.3 (0.72) | 2.3 (0.60) | 2.5 (1.12) | 2.9 (1.44) | 2.6 (1.2) |

| Scan age range (years) | 5.4 – 27.0 | 5.3 – 25.6 | 5.4 – 23.9 | 3.3 – 34.4 | 3.3 – 34.4 |

| Gender |

119 F (54%) 103 M (46%) |

55 F (54%) 46 M (46%) |

36 F (43%) 48 M (57%) |

144 F (53%) 126 M (47%) |

354 F (52%) 323 M (48%) |

| Handedness |

194 R (87%) 15 M (7%) 13 L (6%) |

83 R (82%) 10 M (11%) 8 L (8%) |

68 R (80%) 7 M (8%) 9 L (11%) |

241 R (89%) 18 M (7%) 11 L (4%) |

586 R (87%) 50 M (7%) 41 L (6%) |

|

Socioeconomic status (SES) (Hollingshead Index SD) |

43.2 (18.0) | 41.8 (15.2) | 40.7 (17.3) | 40.1 (20.1) | 41.4 (18.4) |

MRI acquisition

All MRI images were acquired on the same General Electric 1.5 Tesla Signa Scanner located at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in Bethesda, Maryland. A three-dimensional spoiled gradient recalled echo sequence in the steady state sequence was used to acquire 124 contiguous 1.5-mm thick slices in the axial plane (TE/TR = 5/24 ms; flip angle = 45 degrees, matrix = 256 × 192, NEX = 1, FOV = 24 cm, acquisition time 9.9 min). A Fast Spin Echo/Proton Density weighted imaging sequence was also acquired for clinical evaluation. A total of 1,318 MRI scans were acquired. Up to six MRI scans were performed per individual (specific N by timepoint: timepoint 1 = 300, 2 = 213, 3 = 93, 4 = 46, 5 = 21, 6 = 4), with sibships containing up to five members. The mean interval between scans was 2.4 years. All anatomic images were visually inspected for quality by an expert reviewer using a four-point scale62; only scans with the highest quality rating were included in the current analysis. Given increasing concerns of the role of image quality on measurement63,64, a more stringent quality control pipeline was used compared to prior work36 resulting in the exclusion of 115 subjects from the current analysis.

Image analysis

All MR images were imported into the CIVET pipeline for automated structural image processing65. Briefly, the native MRI scans were registered into standardized stereotaxic space using a linear transformation66 and corrected for non-uniformity artifacts67. The registered and corrected volumes were segmented into white matter, gray matter, cerebrospinal fluid, and background using a neural net classifier68. The gray and white matter surfaces were fitted using deformable surface-mesh models and nonlinearly aligned toward a template surface69–71. Both surfaces were subsequently resampled into native space. The tissue classification information was combined with a probabilistic atlas to provide volumetric region of interest (ROI) measures72. Lobar volumes were included in this analysis for each hemisphere separately. Cortical thickness was measured in native-space using the linked distance between the white and pial surfaces70,73 and assigned to specific regions using a probabilistic atlas74. Each vertex was assigned to one of 308 regional parcellations based on the 68 ROIs of the Desikan-Killany atlas75. These canonical parcellations were further divided into ~500mm2 sub-ROIs based on a backtracking algorithm76. This approach resulted in relatively uniformly-sized ROIs, while also preserving the original boundaries of the Desikan-Killany atlas (Fig. 1A). ROIs were subsequently visually inspected to ensure quality.

Statistics and reproducibility

Latent growth curve modeling

Each subject’s neuroanatomic measures were imported into the R statistical environment for analysis77. The data were reformatted such that each record represented family-wise (rather than individual-wise) data. The subsequent dataset contained up to six longitudinal ROI measures per individual, and up to five individuals per family. Genetic modeling was performed in Open Mx, a structural equation modeling package fully integrated into the open source R environment78,79.

For each pairwise combination of ROIs, a genetically informative bivariate quadratic latent growth curve (LGC) model was constructed80,81. Genetically informative LGC models for the analysis of neuroimaging data have been described elsewhere2,36. Compared to other longitudinal methods, LGCs have the advantage that they allow for direct age-based predictions, are robust to missing data cells, and are customizable to unique data structures82. A simplified path diagram is provided in Supplementary Fig. S10. Structural equation models decomposed the variances and covariances between the three latent growth curve factors (intercept, linear, and quadratic) into additive genetic (A) and specific environmental (E) components. Quantitative genetic models often include latent factors estimating the role of the shared environment (C); however, since prior studies have shown that shared environmental contributions to CT variance in this age rage are minimal25, shared environmental latent factors were excluded from the model. Because the study design acquired panel rather than cohort longitudinal data, the age at scan was integrated into the model as a dynamic (i.e. definition) variable to individualize growth curve predictions83. ROI CT means were adjusted for sex, age, age, and global mean CT.

Models were fitted by maximum likelihood, which generally yields asymptotically unbiased parameter estimates of the genetic and nongenetic contributions to ROI-ROI CT covariance. In order to test the statistical significance of genetic factors on temporal variability, submodels were constructed which removed the free parameters modeling changes in ROI-ROI covariance (while retaining the main effects); Given certain regularity conditions, differences in log-likelihood between these models asymptotically follow a χ2 distribution with degrees of freedom equal to number of parameters removed (9 degrees of freedom for all genetic effects, 6 degrees of freedom for change)84–86. The statistical significance of all additive genetic influences on CT variability (i.e. both main effects and changes) were quantified similarly. Statistical tests were two-sided.

Visualizing dynamic changes in genetic associations

Using the maximum likelihood parameter estimates from our quadratic models, time-specific genetic covariance matrices were then estimated for 124 equally-spaced intervals over the 5–18 year age range (~0.1 year intervals), which resulted in sufficient temporal resolution to describe the growth curves. Genetic covariance matrices can be conceptualized as that portion of the phenotypic variance-covariance matrix associated with additive genetic effects on the diagonal. ROI-ROI genetic covariances, describing the covariance that two phenotypes share via additive genetic factors, comprise the of-diagonal elements Genetic correlations (rG) were then calculated for each timepoint by standardizing the genetic covariance matrix, mathematically defined as:

Where is an off-diagonal element of , and and are the corresponding diagonal elements.

Dynamic changes in rG over time were then visualized by concatenating serial heatmaps to construct a 3D correlation matrix, with 2 spatial dimensions (pairwise ROI-ROI combinations) and 1 temporal dimension (Supplemental Movie S1). As an alternative method of visualization, serial graph theoretical (i.e., network) models of the strongest CT-CT genetic correlations were constructed at multiple timepoints, with each ROI’s position in the graph set to the MNI spatial coordinates of its centroid. Undirected edges were determined by binarizing the 3D correlation matrix based on correlational thresholds (e.g., rG = 0.8) and the results visualized using serial graph models (e.g., Fig. 1B and Supplemental Movies S2 and S3). Heritability estimates (i.e. the proportion of phenotypic variance attributable to additive genetic effects) for each ROI were also calculated for each timepoint (Fig. 1B). Finally, spatiotemporal variation in community structure were visualized using the PisCES algorithm, a clustering method that incorporates temporal changes in network strength into its algorithm, enabling visualization of how genetically-mediated CT clusters evolve over time (Supplementary Fig. S1)87.

Neurodevelopmental epochs in maturational coupling

To identify critical neurodevelopmental periods in genetically-mediated maturational coupling, we applied nonnegative matrix factorization (NMF) to our 3D genetic correlation matrix (Fig. 2A). NMF is an unsupervised data reduction technique similar to latent variable analysis that has been applied to a variety of large datasets including image recognition88, gene discovery89, structural and functional brain connectivity analysis90,91, and a broad assortment of other high-dimensional bioinformatics data. NMF has several advantages relative to other dimensionality reduction techniques, including that it allows for overlap of subcomponents and generally leads to better interpretability of parameter estimates. Of particular note, NMF has previously been applied to high-dimensional neuroimaging datasets on temporally-varying endophenotypes90,92.

Our general analytic framework was modeled after Kao et al., which investigated similarly structured data consisting of a 3D series of dynamic ROI-ROI correlation matrices90. The lower triangular ROI-ROI genetic correlation matrix (g=47,278 pairwise elements) for t=31 equally-spaced time points (~0.4 year intervals) from ages 5-18 was vectorized; the choice of 31 timepoints was based on computational limitations. All time-specific correlation vectors were then concatenated into a single g x t matrix. Because NMF requires positive values, positive rG values were isolated by constructing a matrix in which negative correlations were set to zero. Negative correlations were similarly isolated (with positive values set to zero), and both positive and negative matrices were concatenated into a single V = g x 2t analysis matrix.

NMF was then applied to this matrix using the NMF package in R93. NMF attempts to identify:

where W and H are g x r and r x 2t non-negative matrices, respectively. The NMF algorithm initialized W and H parameters using Nonnegative Double Singular Value Decomposition94, and then performed iterative optimization of the Kullback-Leibler Divergence89,95. Choice of factorization rank, r, was determined empirically using the method of Hutchins et al.96. Specifically, the residual sum of squares (RSS) for models with r ranging from 2-26 was generated and plotted with 100 randomly-initiated runs per rank; r was selected at the natural inflection point in the RSS curve (Figure S11). For our data, this resulted in a factorization of 6. The output matrix W represents genetically-mediated edge strength between two ROIs for each of 6 subgraphs, and H represents time-varying expression strength of each subgraph. Similar to Kao et al., there was strong temporal correspondence between positive and negative correlation subgraphs; these were combined to generate subgraphs at the 3 critical neurodevelopmental timepoints identified by the NMF algorithm.

The network properties of each subgraph were then explored in igraph97. A 308 x 308 unweighted adjacency matrix R was generated that contained pairwise similarity measures for all elements rij, resulting in a set of M ROI-ROI connections (i.e. edges). Common global network statistics for three common measures of network strength (degree, clustering coefficient, assortativity)12 were then calculated for each epoch separately. Briefly:

Degree (D): The degree, or node strength, is simply the total number of connections that a network vertex (in our case, an ROI) has with other vertices. For vertices i and j:

The more connections an ROI has to other brain regions, the higher the degree. The global measure was simply calculated the mean degree over the entire network.

Clustering Coefficient (C): The global clustering coefficient (also known as transitivity) is the mean proportion of a vertex’s neighbors that are also connected to one another98. For a single vertex v in set V, the clustering coefficient C the proportion of all possible connections with neighboring vertices which are realized:

where a “closed triplet” represents a group of three vertices that are all connected, and “all triplets” also includes groups where only two vertices are connected.

Assortatitivity (A): Assortatitivity describes the tendency of vertices connect to other vertices with similar properties99. We used the most commonly used measure of assortiativity; degree assortativity. For M total edges in the network, the degree assortativity can be calculated as:

where ik and jk are the degrees of the vertices at the ends of the kth edge for k=1 … M100. Note that although this calculation appears complex, it essentially represents the Pearson correlation of degree between pairs of linked vertices.

Since network density can potentially influence many network statistics101, all global network densities were calculated for multiple network sparsities ranging from 1% to 20%. 95% confidence intervals were obtained via bootstrap, with the null distribution generated by randomly rewiring each graph (while preserving graph degree), with 1000 replicates per bootstrap. The two-sided statistical significance of age-related differences in global network statistics were assessed via permutation of difference scores, also with 1000 replicates per sparsity level.

Cortical thickness and gene transcription

We then compared the observed patterns of CT-CT genetic correlations to the normalized human gene transcriptional profiles provided by the Allen Human Brain Atlas (AHBA). The AHBA includes post-mortem transcriptional measurements for >62,000 probes from 6 individuals aged 24–57 years, sampled at hundreds neuroanatomic locations per subject (364 – 947), all mapped to MNI space102. Prior to transcriptomic analysis, gene-to-probe reannotation was performed with Re-Annotator103. We then excluded AHBA samples derived from noncortical structures (e.g. putamen). Only probes with high expression above background were included; specifically, only probes with a both (1) a mean difference score p-value <0.01, and (2) a standard deviation >2.6 above background levels survived QA104. Expression values for each sample were subsequently converted to Z-scores.

AHBA samples were then aligned to CT data by nearest neighbor matching, based on MNI coordinates (Fig. 3A). Because only two AHBA subjects had samples from the right cerebral hemisphere, these samples were mirrored onto the left hemisphere by inverting their MNI x coordinates. Following alignment, all but one of the 152 left-sided CT ROIs were matched to at least one sample. The single unmatched ROI (supramarginal gyrus 7) was excluded. Median expression values at each location between all subjects were then calculated. Following all QA, annotation, and alignment steps, expression data for 21,165 probes across 151 ROIs were available. We then used our CT genetic correlation matrix to extract gene sets with similar co-expression patterns. This analysis was accomplished using Seurat, an R package with algorithms designed for multidimensional transcriptomics105. The left-hemispheric genetic correlation matrix for age = 13 years (151 x 151) was converted to a k=20 weighted nearest neighbor kernel. Age 13 was selected because it was close to the median age of our sample, in the region of densest genetically informative data. Supervised Principal Component Analysis (sPCA) was then performed using this kernel and the genetic transcription matrix as inputs106. sPCA is similar to routine PCA, except the algorithm ensures that the subsequent components have maximal dependence on the kernel response variables.

The largest component (sPC1) explained nearly 70% of the total variance in the AHBA dataset. We subsequently constructed a candidate gene set associated with sPC1 by extracting genes with the strongest (top and bottom 1%) associations to this latent component, i.e., those genes with the strongest absolute loadings on the dominant factor. Spatial expression patterns for the genes with the strongest factor loadings were visualized by projecting expression Z-scores onto brain models. The total gene set was then input into Metascape for annotation, gene enrichment analysis, and identification of protein-protein interactions107. To minimize false positives, a custom set of 15,745 brain-expressed genes was used as the background for enrichment analysis108. Protein interaction analysis was performed with the Molecular Complex Detection (MCODE) algorithm109 and subsequent functional enrichment in Metascape.

Because of results from gene enrichment analysis, we also compared gene expression patterns from our sPCA-derived set with several cell-specific gene sets, as described in Seidlitz et al.110. Cell-specific sets were based on data from several prior studies111–114. Median gene expression for each cell-specific gene set was calculated over 151 cortical ROIs. Similar median expression vectors were also calculated for our sPCA gene set (Supplementary Data 1: tab Table S1), all 21,165 AHBA genes surviving QA/QC, and the subset 15,745 of brain-expressed genes also used as background for enrichment analyses108. Correlations in regional expression patterns between each set were calculated. Additionally, the 151 x 151 ROI-ROI co-expression matrices were compared between sPCA and each cell-specific gene set using the partial Mantel test, after controlling for co-expression patterns in the brain-expressed gene set. 10,000 permutations were used to estimate the null; statistical tests were two-sided.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgements

J.E.S. was supported by K01ES026840. A.A.B. was supported by NIH/NIMH K08MH120564. J.S. was supported by NIH/NIMH T32MH019112-29. A.R. was supported by the NIMH Intramural Research Program (1ZIAMH002949-04). M.C.N. was supported by NIH/NIDA grants R01DA049867 and U01DA051037.

Author contributions

Eric Schmitt: conceptualization, statistical design, analysis, visualization, writing-original draft, and editing. Aaron Alexander-Bloch: statistical consultation, software development, writing-review, and editing. Jakob Sleiditz: statistical/genomic consultation, generation of cell-specific expression dataset, writing-review and editing. Armin Raznahan: conceptualization, data acquisition, image processing, writing-review, and editing. Mike Neale: conceptualization, software development, writing-review, and editing.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Hervé Lemaître and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Michel Thiebaut de Schotten, Karli Montague-Cardoso and Jasmine Pan.

Data availability

The NIMH Longitudinal Development MRI dataset is available online at: http://nda.nih.gov/edit_collection.html?id=3142. Derived data (e.g. 3D genetic correlations), Supplementary Figs., tables, and movies are available in DataDryad: 10.5061/dryad.7h44j103r115.

Code availability

R code for genetically informative longitudinal structural equation models, NMF, AHBA-NIH sample integration, and sPCA is available from the corresponding author upon request. Gene enrichment analysis tools are freely-available available online.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-024-06956-2.

References

- 1.Gogtay, N. & Giedd, J. Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA101, 8174–8179 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmitt, J. et al. The dynamic role of genetics on cortical patterning during childhood and adolescence. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA111, 6774–6779 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tamnes, C. K. et al. Development of the cerebral cortex across adolescence: a multisample study of inter-related longitudinal changes in cortical volume, surface area, and thickness. J. Neurosci.37, 3402–3412 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyall, A. E. et al. Dynamic development of regional cortical thickness and surface area in early childhood. Cereb. Cortex25, 2204–2212 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilmore, J. H. et al. Longitudinal development of cortical and subcortical gray matter from birth to 2 years. Cereb. Cortex11, 2478–2485 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raznahan, A. et al. How does your cortex grow? J. Neurosci.31, 7174–7177 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw, P. et al. Neurodevelopmental trajectories of the human cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci.28, 3586–3594 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sowell, E. R. et al. Longitudinal mapping of cortical thickness and brain growth in normal children. J. Neurosci.24, 8223–8231 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raznahan, A. et al. Patterns of coordinated anatomical change in human cortical development: a longitudinal neuroimaging study of maturational coupling. Neuron72, 873–884 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walhovd, K. B., Fjell, A. M., Giedd, J., Dale, A. M. & Brown, T. T. Through thick and thin: a need to reconcile contradictory results on trajectories in human cortical development. Cereb. Cortex27, 1–10 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mechelli, A., Friston, K. J., Frackowiak, R. S. & Price, C. J. Structural covariance in the human cortex. J. Neurosci.25, 8303–8310 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alexander-Bloch, A., Giedd, J. N. & Bullmore, E. Imaging structural co-variance between human brain regions. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.14, 322–336 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lerch, J. P. et al. Mapping anatomical correlations across cerebral cortex (MACACC) using cortical thickness from MRI. NeuroImage31, 993–1003 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He, Y., Chen, Z. J. & Evans, A. C. Small-world anatomical networks in the human brain revealed by cortical thickness from MRI. Cereb. Cortex17, 2407–2419 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zielinski, B. A., Gennatas, E. D., Zhou, J. & Seeley, W. W. Network-level structural covariance in the developing brain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA107, 18191–18196 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geng, X. et al. Structural and maturational covariance in early childhood brain development. Cereb. Cortex27, 1795–1807 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vijayakumar, N. et al. The development of structural covariance networks during the transition from childhood to adolescence. Sci. Rep.11, 1–12 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Váša, F. et al. Adolescent tuning of association cortex in human structural brain networks. Cereb. Cortex28, 281–294 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khundrakpam, B. S. et al. Imaging structural covariance in the development of intelligence. NeuroImage144, 227–240 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alexander-Bloch, A., Raznahan, A., Bullmore, E. & Giedd, J. The convergence of maturational change and structural covariance in human cortical networks. J. Neurosci.33, 2889–2899 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maggioni, E., Squarcina, L., Dusi, N., Diwadkar, V. A. & Brambilla, P. Twin MRI studies on genetic and environmental determinants of brain morphology and function in the early lifespan. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev.109, 139–149 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilmore, J. H. et al. Genetic and environmental contributions to neonatal brain structure: a twin study. Hum. Brain Mapp.31, 1174–1182 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peper, J. S. et al. Heritability of regional and global brain structure at the onset of puberty: a magnetic resonance imaging study in 9-year-old twin pairs. Hum. Brain Mapp.30, 2184–2196 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giedd, J., Schmitt, J. E. & Neale, M. C. Structural Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Pediatric Twins. Hum. Brain Mapp. 28, 474–481 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Lenroot, R. K. R. K. et al. Differences in genetic and environmental influences on the human cerebral cortex associated with development during childhood and adolescence. Hum. Brain Mapp.30, 163–174 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmitt, J. E. et al. Identification of genetically mediated cortical networks: a multivariate study of pediatric twins and siblings. Cereb. Cortex18, 1737–1747 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmitt, J. E. et al. Variance decomposition of MRI-based covariance maps using genetically informative samples and structural equation modeling. Neuroimage47, 56–64 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Soelen, I. L. C. et al. Genetic influences on thinning of the cerebral cortex during development. Neuroimage59, 3871–3880 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brouwer, R. M. et al. Genetic variants associated with longitudinal changes in brain structure across the lifespan. Nat. Neurosci.25, 421–432 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teeuw, J. et al. Genetic influences on the development of cerebral cortical thickness during childhood and adolescence in a Dutch longitudinal twin sample: The brainscale study. Cereb. Cortex29, 978–993 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huttenlocher, P. R., & Dabholkar, A. S. Regional differences in synaptogenesis in human cerebral cortex. J. Comp. Neurol.387, 167–178 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rakic, P. Evolution of the neocortex: A perspective from developmental biology. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.10, 724–735 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rakic, P. Specification of cerebral cortical areas. Science (1979)241, 170–176 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krzanowski, J. W. Principal Component Analysis in the Presence of Group Structure. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C. (Appl. Stat.)33, 164–168 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Norbom, L. B. et al. New insights into the dynamic development of the cerebral cortex in childhood and adolescence: Integrating macro- and microstructural MRI findings. Prog. Neurobiol.204, 102109 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmitt, J. E., Giedd, J. N., Raznahan, A. & Neale, M. C. The genetic contributions to maturational coupling in the human cerebrum: a longitudinal pediatric twin imaging study. Cereb. Cortex28, 3184–3191 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Irimia, A. & Van Horn, J. D. The structural, connectomic and network covariance of the human brain. Neuroimage66, 489–499 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yee, Y. et al. Structural covariance of brain region volumes is associated with both structural connectivity and transcriptomic similarity. Neuroimage179, 357–372 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.French, L. & Pavlidis, P. Relationships between gene expression and brain wiring in the adult rodent brain. PLoS Comput Biol.7, e1001049 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fjell, A. M. et al. Development and aging of cortical thickness correspond to genetic organization patterns. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA112, 1–6 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kang, H. J. et al. Spatio-temporal transcriptome of the human brain. Nature478, 483–489 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fair, D. A. et al. The maturing architecture of the brain’s default network. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA105, 4028–4032 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petanjek, Z. et al. Extraordinary neoteny of synaptic spines in the human prefrontal cortex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA108, 13281–13286 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silbereis, J. C., Pochareddy, S., Zhu, Y., Li, M. & Sestan, N. The Cellular and Molecular Landscapes of the Developing Human Central Nervous System. Neuron89, 268 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kalinka, A. T. et al. Gene expression divergence recapitulates the developmental hourglass model. Nature468, 811–816 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Domazet-Lošo, T. & Tautz, D. A phylogenetically based transcriptome age index mirrors ontogenetic divergence patterns. Nature468, 815–819 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li, M. et al. Integrative functional genomic analysis of human brain development and neuropsychiatric risks. Science (1979)362, eaat7615 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paus, T., Keshavan, M. & Giedd, J. Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat. Rev. Neurosci.9, 947–957 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smoller, J. W. et al. Psychiatric genetics and the structure of psychopathology. Mol. Psychiatry24, 409–420 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Romero-Garcia, R. et al. Structural covariance networks are coupled to expression of genes enriched in supragranular layers of the human cortex. Neuroimage171, 256–267 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Valk, S. L. et al. Shaping brain structure: genetic and phylogenetic axes of macroscale organization of cortical thickness. Sci. Adv.6, 1–15 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burt, J. B. et al. Hierarchy of transcriptomic specialization across human cortex captured by structural neuroimaging topography. Nat. Neurosci.21, 1251–1259 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Giedd, J. N. et al. Child psychiatry branch of the national institute of mental health longitudinal structural magnetic resonance imaging study of human brain development. Neuropsychopharmacology40, 43–49 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shin, J. et al. Cell-specific gene-expression profiles and cortical thickness in the human brain. Cereb. Cortex28, 3267–3277 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cotella, D. et al. Toxic role of K + channel oxidation in mammalian brain. J. Neurosci.32, 4133–4144 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fu, J., Liu, F., Qin, W., Xu, Q. & Yu, C. Individual-level identification of gene expression associated with volume differences among neocortical areas. Cereb. Cortex30, 3655–3666 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Richiardi, J. et al. Correlated gene expression supports synchronous activity in brain networks. Science (1979)348, 1241–1244 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang, G. Z. et al. Correspondence between resting-state activity and brain gene expression. Neuron88, 659–666 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maes, H. H. M. et al. Genetic and environmental variation in continuous phenotypes in the ABCD Study®. Behav. Genet.53, 1–24 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Masouleh, S. K. et al. Influence of processing pipeline on cortical thickness measurement. Cereb. Cortex30, 5014–5027 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Han, X. et al. Reliability of MRI-derived measurements of human cerebral cortical thickness: The effects of field strength, scanner upgrade and manufacturer. Neuroimage32, 180–194 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Blumenthal, J. D., Zijdenbos, A., Molloy, E. & Giedd, J. N. Motion artifact in magnetic resonance imaging: implications for automated analysis. Neuroimage16, 89–92 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alexander-Bloch, A. et al. Subtle in-scanner motion biases automated measurement of brain anatomy from in vivo MRI. Hum. Brain Mapp.37, 2385–2397 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rosen, A. F. G. et al. Quantitative assessment of structural image quality. Neuroimage169, 407–418 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ad-Dab’bagh, Y. et al. The CIVET image-processing environment: a fully automated comprehensive pipeline for anatomcal neuroimaging research. in Proceedings of the 12th Annual Meeting of the Organization for Human Brain Mapping (ed. Corbetta, M.) (2006).

- 66.Collins, D., Neelin, P., Peters, T. & Evans, A. Automatic 3D intersubject registration of MR volumetric data in standardized Talairach space. J. Comput Assist Tomogr.18, 192–205 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sled, J. G., Zijdenbos, A. P. & Evans, A. C. A nonparametric method for automatic correction of intensity nonuniformity in MRI data. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging17, 87–97 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zijdenbos, A. P., Forghani, R. & Evans, A. C. Automatic ‘pipeline’ analysis of 3-D MRI data for clinical trials: application to multiple sclerosis. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging21, 1280–1291 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim, J. S. et al. Automated 3-D extraction and evaluation of the inner and outer cortical surfaces using a Laplacian map and partial volume effect classification. Neuroimage27, 210–221 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.MacDonald, D., Kabani, N., Avis, D., & Evans, A. C. Automated 3-D extraction of inner and outer surfaces of cerebral cortex from MRI. Neuroimage12, 340–356 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Robbins, S., Evans, A. C., Collins, D. L. & Whitesides, S. Tuning and comparing spatial normalization methods. Med. Image Anal.8, 311–323 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Collins, D. L., Holmes, C. J., Peters, T. M. & Evans, A. C. Automatic 3-D model-based neuroanatomical segmentation. Hum. Brain Mapp.3, 190–208 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lerch, J. & Evans, A. Cortical thickness analysis examined through power analysis and a population simulation. Neuroimage24, 163–173 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Collins, D., Zijdenbos, A., Barre, W. & Evans, A. ANIMAL-INSECT: improved cortical structure segmentation. in Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Information Processing in Medical Imaging (IPMI) 210–223 (Springer, 1999).

- 75.Desikan, R. S. et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage31, 968–980 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Romero-Garcia, R., Atienza, M., Clemmensen, L. H. & Cantero, J. L. NeuroImage Effects of network resolution on topological properties of human neocortex. Neuroimage59, 3522–3532 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.R. Core Team. R: A Language And Environment For Statistical Computing (2020).

- 78.Boker, S., Neale, M., Maes, H., Wilde, M. & Spiegel, M. OpenMx: an open source extended structural equation modeling framework. Psychometrika76, 306–317 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Neale, M. C. et al. OpenMx 2.0: extended structural equation and statistical modeling. Psychometrika81, 535–549 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Neale, M. & McArdle, J. Structured latent growth curves for twin data. Twin Res.3, 165–177 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McArdle, J. J. et al. Structural modeling of dynamic changes in memory and brain structure using longitudinal data from the normative aging study. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci.59, P294–P304 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mcardle, A. J. J. & Epstein, D. Latent growth curves within developmental structural equation models. Child Dev.58, 110–133 (2013). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mehta, P. & West, S. Putting the individual back into individual growth curves. Psychol. Methods5, 23–43 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Neale, M. M. C. & Cardon, L. R. L. Methodology for Genetic Studies of Twins and Families. Methodology for Genetic Studies of Twins and Families (Kluver, 1992).

- 85.Dominicus, A., Skrondal, A., Gjessing, H. K., Pedersen, N. L. & Palmgren, J. Likelihood ratio tests in behavioral genetics: problems and solutions. Behav. Genet.36, 331–340 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Visscher, P. M. Power of the classical twin design revisited. Twin Res.7, 505–512 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Liu, F., Choi, D., Xie, L. & Roeder, K. Global spectral clustering in dynamic networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA115, 927–932 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lee, D. & Seung, H. Learning the parts of objects by non-negative matrix factorization. Nature401, 788–791 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Brunet, J. P., Tamayo, P., Golub, T. R. & Mesirov, J. P. Metagenes and molecular pattern discovery using matrix factorization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA101, 4164–4169 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kao, C. H. et al. Functional brain network reconfiguration during learning in a dynamic environment. Nat. Commun.11, 1–13 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sotiras, A., Resnick, S. M. & Davatzikos, C. Finding imaging patterns of structural covariance via Non-Negative Matrix Factorization. Neuroimage108, 1–16 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Phalen, H., Coffman, B. A., Ghuman, A., Sejdić, E. & Salisbury, D. F. Non-negative matrix factorization reveals resting-state cortical alpha network abnormalities in the first-episode schizophrenia spectrum. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging5, 961–970 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gaujoux, R. & Seoighe, C. A flexible R package for nonnegative matrix factorization. BMC Bioinform.11, 367 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Boutsidis, C. & Gallopoulos, E. SVD based initialization: A head start for nonnegative matrix factorization. Pattern Recognit.41, 1350–1362 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 95.Berry, M. W., Browne, M., Langville, A. N., Pauca, V. P. & Plemmons, R. J. Algorithms and applications for approximate nonnegative matrix factorization. Comput Stat. Data Anal.52, 155–173 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hutchins, L. N., Murphy, S. M., Singh, P. & Graber, J. H. Position-dependent motif characterization using non-negative matrix factorization. Bioinformatics24, 2684–2690 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Csárdi, G. & Nepusz, T. The igraph software package for complex network research. InterJournal Complex Syst.1695, 1695 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 98.Barrat, A., Barthé Lemy †, M., Pastor-Satorras, R. & Vespignani, A. The Architecture of Complex Weighted Networks. www.iata.org (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 99.Foster, J. G., Foster, D. V., Grassberger, P. & Paczuski, M. Edge direction and the structure of networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA107, 10815–10820 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Newman, M. E. J. Assortative Mixing in Networks. Phys. Rev. Lett.89, 208701 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bassett, D. S. et al. Hierarchical organization of human cortical networks in health and Schizophrenia. J. Neurosci.28, 9239–9248 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hawrylycz, M. J. et al. An anatomically comprehensive atlas of the adult human brain transcriptome. Nature489, 391–399 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Arloth, J., Bader, D. M., Röh, S. & Altmann, A. Re-Annotator: annotation pipeline for microarray probe sequences. PLoS ONE10, 1–13 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Quackenbush, J. Microarray data normalization and transformation. Nat. Genet.32, 496–501 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Satija, R., Farrell, J. A., Gennert, D., Schier, A. F. & Regev, A. Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nat. Biotechnol.33, 495–502 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Barshan, E., Ghodsi, A., Azimifar, Z. & Zolghadri Jahromi, M. Supervised principal component analysis: visualization, classification and regression on subspaces and submanifolds. Pattern Recognit.44, 1357–1371 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhou, Y. et al. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat. Commun.10, 1523 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Morgan, S. E., Seidlitz, J., Whitaker, K. J., Romero-garcia, R. & Clifton, N. E. Cortical patterning of abnormal morphometric similarity in psychosis is associated with brain expression of schizophrenia-related genes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA116, 9604–9609 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bader, G. & Hogue, C. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinform.4, 2 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Seidlitz, J. et al. Transcriptomic and cellular decoding of regional brain vulnerability to neurogenetic disorders. Nat. Commun.11, 1–14 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhang, Y. et al. Purification and characterization of progenitor and mature human astrocytes reveals transcriptional and functional differences with mouse. Neuron89, 37–53 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lake, B. B. et al. Integrative single-cell analysis of transcriptional and epigenetic states in the human adult brain. Nat. Biotechnol.36, 70–80 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Habib, N. et al. Massively parallel single-nucleus RNA-seq with DroNc-seq. Nat. Methods14, 955–958 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Darmanis, S. et al. A survey of human brain transcriptome diversity at the single cell level. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA112, 7285–7290 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Schmitt, J. E., Alexander-Bloch, A., Sleiditz, J., Raznahan, A. & Neale, M. C. Data From: the genetics of spatiotemporal variation in cortical thickness in youth [dataset]. Dryad10.5061/dryad.7h44j103r (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The NIMH Longitudinal Development MRI dataset is available online at: http://nda.nih.gov/edit_collection.html?id=3142. Derived data (e.g. 3D genetic correlations), Supplementary Figs., tables, and movies are available in DataDryad: 10.5061/dryad.7h44j103r115.

R code for genetically informative longitudinal structural equation models, NMF, AHBA-NIH sample integration, and sPCA is available from the corresponding author upon request. Gene enrichment analysis tools are freely-available available online.