Abstract

The perovskite and organic solar cells are becoming the most cognizant of the photovoltaic communities. The Spiro-OMeTAD organic hole transport layer (HTL) shows a significant impact on the CH3NH3SnI3 perovskite solar cell (PSC) with TiO2 as the electron transport layer (ETL). So, we optimized the physical and electrical parameters of the organic HTL. Electrical optimization shows that the power conversion efficiency (PCE) of the cell can reach up to for the electron affinity of the organic HTL material of about . Further, the interpretation of the practical scale of series and shunt resistance reveals the maximum PCE of the cell as at and respectively. Also, the performance of the cell is analyzed for the hole mobility of the organic HTL material, which revealed the best PCE of the cell to . Moreover, the physical parameters are also optimized for the cell performance with illumination intensities which pointed out that the performance of the novel organic HTL perovskite solar cell is optimum for illumination intensity around (500Wm-2). Finally, the overall light harnessing efficiency or PCE of the proposed solar cell is declared to be and the other performance parameters as open circuit voltage (Voc), short circuit current (Jsc), and fill factor (FF) are , and respectively.

Keywords: Hybrid solar cell, Organic-inorganic perovskite, Spiro-OMeTAD, SCAPS-1D, Shallow acceptor density

1. Introduction

Energy needs will significantly increase in the forthcoming years. The majority of today's energy needs are met by fossil fuels, and they will soon run out. Therefore, creating a renewable energy source is the most challenging task since it pollutes the environment. Modernization and population increase are demanding more renewable power. Solar energy is a rising source of that, but only because it is safe for the environment and has minimum harmful impacts [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6]]. As a sustainable energy option, solar-powered devices are required as suggested by Wang et al. [7]. Due to the exceptional photoelectric capabilities of hybrid perovskite materials, perovskite solar cells-the dominant figure in photovoltaic technology has attained widespread recognition. Earlier halide-based perovskite solar cells CH3NH3PbX3 (X = Br, I) exhibited PCE 9.4 % and 6.7 % for absorber layers CH3NH3PbI3 and CH3NH3PbBr3 as commenced by researchers [8,9]. These halide perovskite solar cells (PSC) cause fluctuations in the electrical parameters, which disclose the transformation of the semiconductor into a metal with a growing structural dimension by Mitzi et al. [10].

The organic-inorganic hybrid PSC has grown surprisingly quickly in the six years after the invention of solid organic semiconductors as hole-transporting material (HTM) [11,12]. Recent developments in hybrid perovskite materials (HPM) have significantly impacted solar cell production due to their improved ability to convert photon energy effectively for prospective solar devices [13,14]. An electron-transporting material (ETM) and a hole-transporting material (HTM) are sandwiched between a perovskite photoactive layer {ABX3, A = CH3NH3, CH3(NH2)2, or Cs; B = Pb or Sn; X = Cl, Br, or I} in a conventional perovskite solar cell. As a consequence of this, photogenerated electrons and holes pass through materials that carry charges, called ETM and HTM, that are several hundred nm thick before reaching the current collectors. Charge transporting materials with sufficient carrier-carrying capacities are necessary to achieve optimum performance in PSC.

Because of their low-cost solution processing, high absorption coefficient, efficient light harvesting, carrier transport, low rate of charge generation and recombination, and large band gaps, organic-inorganic hybrid PSC are currently receiving a lot of attention from the solar cell industry [[14], [15], [16]]. The PCE of PSC has just exceeded 25 % [15]. Unadulterated and improved methylammonium lead halides have been investigated as perovskite materials because of their outstanding photocatalytic activity [[17], [18], [19], [20]] reported that the organic-inorganic hybrid CH3NH3PbI3 PSC was capable of converting energy, and they predicted that its PCE value would range from 20 % to 29 %. However, the use of lead-based electrical items has been severely restricted by the European Union and a few other organizations. The PCE of these compounds was remarkably high. Although it has many advantages, it can also have disadvantages such as problems with temperature and atmospheric consistency, problems with large-scale production and processing, and Pb toxic effects that are not good for the environment or humans [20,21].

Lead-free perovskite CH3NH3SnI3 has been investigated by numerous scientists and researchers as a photovoltaic material to address this problem because of its outstanding optoelectronic capabilities. Organic-inorganic hybrid PSC based on MAXI3 (MA = CH3NH3, X = Sn, Ge), which provides a high PCE value (25.05 %), has already been effectively manufactured/simulated by several researchers by Santos et al. [22]. According to a recent study's explanation, lead-free MAXI3 is just as beneficial as lead [[23], [24], [25]]. For use as an absorber in solar cell applications Lin et al. [26] MASnI3, has a straight band gap of 1.3eV. One essential element of PSC is the electron transport layer (ETL). Due to its favorable energy level for photogenerated electrons, high mobility of electrons, chemical resistance, cheap fabrication, and environmental protection, TiO2 is a viable replacement substance by Zhou et al. [27]. To reduce the recombination of charge carriers at the interface of HTL/absorber layer, the hole transport layer (HTL) requires high hole carrier mobility and should produce fewer defects at the interface. The majority of the top-performing PSC use Spiro-OMeTAD as their HTM [28]. Due to relatively poor hole mobility (10−5cm2V−1s−1) of Spiro-OMeTAD, numerous chemicals, such as 4-tert-butylpyridine (TBP) and lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI) and, are frequently employed with Spiro-OMeTAD to improve device efficiency. Finding a cheap and effective chemical dopant for Spiro-OMeTAD oxidation is extremely important. Omarova et al. [29] announced the manufacture of solid-state dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSC); sealing concerns caused by volatile electrolytes must be recognized to accomplish continuing endurance.

Briefly, In the present work, a lead-free MASnI3 absorber-based organic-inorganic hybrid PSCs is designed through SCAPS-1D simulator. Organic-inorganic hybrid CH3NH3SnI3 PSC having the structure from front to back TCO/ETL/IF2/Active/IF1/HTL, which includes MASnI3 (methanaminium triiodstannate (II) functioning as an active layer, at the front contact of FTO (SnO2: F), is stacked which behaves as transparent conducting oxide. Organic Spiro-OMeTAD is used as HTL, and TiO2 is used as ETL for the proposed device.

It is commonly understood that the performance of a solar cell may be modified by adjusting a number of parameters. Primarily, we optimized the many physical parameters of the proposed hole transport layer (HTL), such as doping concentration, thickness, electron affinity, shallow acceptor concentration, and hole mobility of MASnI3 hybrid organic-inorganic PSC. The impact of the thickness and the hole mobility of the HTL was observed to be much less. Further, we optimized firstly the operating environmental conditions, such as the effect of temperature and illumination of sunlight, and secondly, suitable electrical parameters, such as values of low series and high shunt resistance, for the optimum cell performance. Many theorists used the solar cell capacitance simulator to predict Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE of PSC. Finally, from the analyzed optimization plots of various physical and electrical parameters of HTL we evaluate the device performance parameters. The effect of ohmic contact characteristics on lead-free MASnI3 PSC was also examined.

2. Modeled device structure and parameters

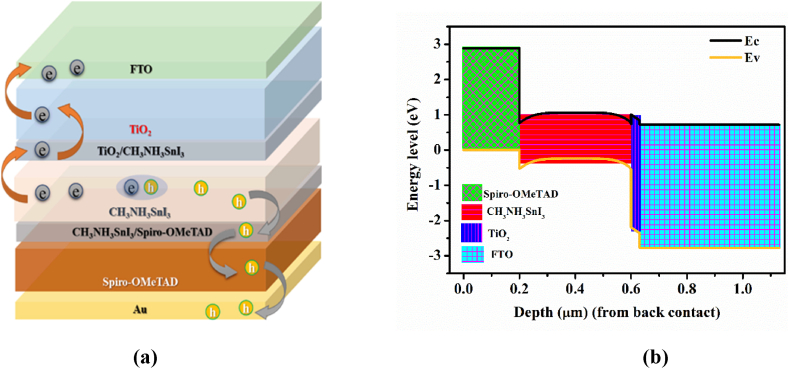

The proposed solar cell is designed using the well-known numerical simulation tool SCAPS 1D. The parameters used to model the proposed solar cell are taken from the pieces of literature based on experimental and theoretical studies as presented in Table 1. Further, optimization of the device is performed by optimizing the electrical parameters of the HTL as well as working parameters. The layered schematic representation of the modeled solar cell structure, along with the energy band diagram of all layers, is shown in Fig. 1(a & b). Fig. 1(a) presents the model of a hybrid organic-inorganic perovskite PSC having the structure trend from front to back “transparent conducting oxide (TCO)/ETL/IF2/Active/IF1/HTL”. The proposed device includes CH3NH3SnI3 functioning as an active layer at the front contact the FTO (SnO2: F fluorine-doped tin oxide) is stacked which behaves as transparent conducting oxide. The ETL is layered in between the active layer and TCO with TiO2 material and HTL layer is enameled with organic Spiro-OMeTAD. Moreover, Fig. 1(b) shows the energy band alignment of the proposed organic PSC over entire depth of the cell. The tin halide organic perovskite (CH3NH3SnI3) is the best substitute for lead halide perovskite, which is harmful to the environment because of the toxic lead material. The total parametric values used for the modeling and simulation study are tabulated in Table 1. The metal-work functions at the contacts are considered such that flat band conditions prevail for every calculation. The model for the flat bands is considered as provided by the SCAPS 1D simulation tool. The properties of the contacts are arranged in Table 2.

Table 1.

Total parametric values for device modeling and simulation.

| Parameters/layers | Spiro-OMeTAD (HTL) [29] | IF1 (HTL/Active) [29,30] | CH3NH3SnI3 (Active) [29] | IF2 (Active/ETL) [31] | TiO2 (ETL) [31] | FTO (TCO) [32] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thickness (μm) | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.03 | 0.5 | ||

| Bandgap (eV) | 2.88 | 1.30 | 3.2 | 3.5 | ||

| Electron affinity (eV) | 2.05 | 4.17 | 3.9 | 4 | ||

| Dielectric permittivity (relative) | 3.0 | 8.2 | 32 | 9 | ||

| Conduction band effective Density of state (cm−3) | 2.2 × 1018 | 1 × 1018 | 1 × 1019 | 2.2 × 1018 | ||

| Valence band effective density of state (cm−3) | 1.8 × 1019 | 1 × 1018 | 1 × 1019 | 1.8 × 1019 | ||

| The thermal velocity of an electron (cms−1) | 1 × 107 | 1 × 107 | 1 × 107 | 1 × 107 | ||

| The thermal velocity of holes (cms−1) | 1 × 107 | 1 × 107 | 1 × 107 | 1 × 107 | ||

| Electron mobility (cm2V−1s−1) | 2 × 10−4 | 1.6 | 20 | 20 | ||

| Hole mobility (cm2V−1s−1) | 2 × 10−4 | 1.6 | 10 | 10 | ||

| Donor density (ND) (cm−3) | 0 | 0 | 1 × 1017 | 2 × 1019 | ||

| Acceptor density (NA) (cm−3) | 2 × 1019 | 3.2 × 1016 | 0 | 0 | ||

| The Defect type | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral |

| Capture cross section of electron (cm2) | 1 × 10−15 | 1 × 10−15 | 1 × 10−14 | 1 × 10−19 | 2 × 10−14 | 1 × 10−15 |

| Capture cross section of holes (cm2) | 1 × 10−15 | 1 × 10−15 | 1 × 10−15 | 1 × 10−19 | 2 × 10−14 | 1 × 10−15 |

| Energetic distribution | Single | Single | Single | Single | Single | Single |

| Reference for defect energy level Et | Above EV | Above the highest EV | Above EV | Above the highest EV | Above EV | Above EV |

| Energy level concerning Reference (eV) | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Total defect density (cm−3) or (cm−2) | 1 × 1015 | 1 × 1015 | 2 × 1015 | 1 × 1010 | 1 × 1014 | 1 × 1015 |

Fig. 1.

(a) Schematic of the proposed Organic HTL PSC and (b) energy level diagram for the conduction band (EC) and valence band (EV) of the entire cell with depth from the rear contact.

Table 2.

Parameters of front and rear contact for device modeling and simulation.

| Parameters/layers | Front contact | Rear contact |

|---|---|---|

| Surface recombination velocity of electron (cms−1) | 1 × 107 | 1 × 105 |

| Surface recombination velocity of holes (cms−1) | 1 × 105 | 1 × 107 |

| Metal work function (eV) | 3.9428 (flat bands) | 4.9327 (flat bands) |

3. Theoretical description

Recently, most of the interest in solar cell research has been oriented toward numerical simulation treatment for the optimization and analysis of numerous physical parameters. In the present study, SCAPS-1D has been used to simulate planar heterojunction organic-inorganic perovskite (OIP) solar cells numerically. By resolving the following Poisson equation using the continuity equation for electrons and holes, performance characteristics such as the current density-voltage (J-V curve), power conversion effectiveness, energy bandgap estimate, etc., may be evaluated. These curves are also used to determine the device's FF, Voc, Jsc, and PCE.

| (1a) |

| (1b) |

| (1c) |

where G, , , D, q, , , , n(z), p(z), , , , and represent the rate of generation, the lifetime of an electron, the lifetime of a hole, coefficient of diffusion, electronic charge, electric potential, e-mobility, h-mobility, free e-concentration, free h-concentration, trapped e-concentration, trapped h-concentration, ionized acceptor concentration, ionized donor concentration, and electric field, respectively. ‘z' denotes the direction.

3.1. The fundamental principle, working and performance parameters

The fundamental principle involved in the functioning of a solar cell is the photovoltaic effect. The working of solar cells goes from the generation of carriers in the absorber layer to recombination at the respective electrodes. Generation of carriers takes place in the absorber via the absorption of suitable photons from the incident radiation. The photogenerated carriers are transported to the electrodes via the transporting layers such as ETL and HTL. Finally, the photogenerated carriers were collected at the electrodes. Mainly, four parameters decide the performance of the solar cell; they are as follows [33,34]:

Open circuit voltage (Voc): It is the voltage across the solar cell when the cell is not connected to the external circuit. And it is given by:

| (2) |

where, , , , and are the Boltzmann's constant, temperature, charge on the carrier, short circuit current, and the saturation current of the cell, respectively, and is the diode ideality factor.

Short circuit current (Jsc): The amount of current when the cell is short-circuited, i.e., the cell is connected to the external circuit. It is given by the equation:

| (3) |

where, and are diffusion lengths for electrons and holes. and are a charge on carriers and generation rate, respectively.

Fill factor (FF): It is the ideality factor that tells us how many times is the practical output of the maximum ideal output power. And can be framed as:

| (4) |

where, , , , and are the power, current, and voltage at the maximum power point, short circuit current, and open circuit voltage, respectively.

Efficiency or power conversion efficiency (PCE) is the ratio of the output power to the input power of the sun that the cell receives in its unit area, and it is given as:

| (5) |

where, is the input power for the cell that it receives from the cell.

3.2. Theories and formulations used in this simulation

The transportation of carriers in the solar cell depends on the different energy band levels at the interfaces of the layers stacked in the solar cell [35,36]. Therefore, at the interface, the band offsets, such as the conduction band offset (CBO) and the valence band offset (VBO), play a vital role in the performance of the solar cell. The CBO and the VBO at the interface of the active layer and HTL can be explained as follows:

| (6) |

and

| (7) |

where, , and , are the conduction band levels and electron affinities for the active and HTL and is the vacuum level energy of the reference and and , are the valence band levels for the active and HTL.

Now for the HTL, as the acceptor concentration increases, the electron concentration decreases, so there will be a surplus number of holes available in the HTL [37], which increases the charge difference and consequently the potential difference around the interface between the active and the HTL. From the conservation of mass , where, , and are the electron, hole, and intrinsic concentration of the HTL and for acceptor doping , being the acceptor concentration, thus, the concentration of the carriers in the dopped HTL can be given as follows.

| (8) |

where, , and are the effective density of states of conduction and valence band, is the band gap, and are Boltzmann's constant and the temperature. The transportation of carriers also depends on the mobilities of the carriers; therefore, the current in the cell also depends on the carrier's mobilities. The conductivity of the device is given as , where, and are the electron and hole mobilities of the HTL and are as defined above, and the current density is [38]:

| (9) |

where, is the electric field due to build-in potential in the HTL region. The energy band gap of the p-n junction formed by different layers in the solar cell is given as a function of temperature [39]:

| (10) |

where, and are the temperature constants for the semiconductors [[40], [41], [42]].

The series and shunt resistance in the solar cell is developed by many factors, which include fabrication processes and the physical conditions of the cell. The FF of the solar cell as a function of the series and shunt resistance can be represented by Refs. [[43], [44], [45]]:

| (11) |

where, and are the fill factor at some series resistance and at no series resistance. and is defined as characteristic resistance and is:

| (12) |

where, is the fill factor at some shunt resistance . The illumination-based simulation is done by applying the neutral density filter (ND filter) in SCAPS 1D. The transmission of this filter is given as . Thus, we applied the various illumination intensities by varying the ND filter value. To have concentrated sunlight we used ND filter <0 whereas for reduced sunlight the ND filter made >0 also simulated in Ref. [45].

4. Results and discussion

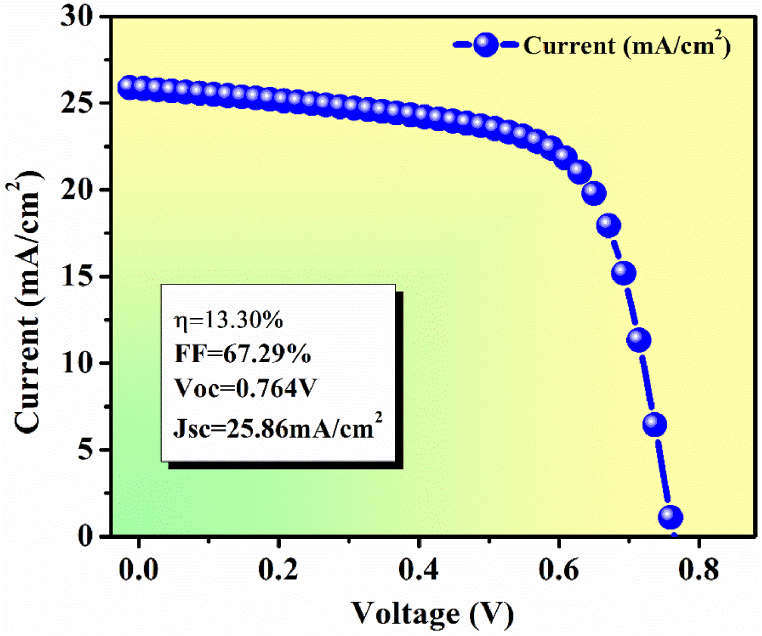

The proposed OIP solar cell (taken under this study) (FTO/TiO2/CH3NH3SnI3/Spiro-OMeTAD) ⁓(TCO/ETL/Active-layer/HTL) is being simulated using SCAPS-1D. Firstly the simulation is done for the optimization of the HTL layer, and then the device is simulated under different environmental, physical, and electrical conditions. The overall I-V curve of the proposed OIP solar cell is shown in Fig. 2. Fig. 2 well shows that the best possible values of the performance parameters at well-suited optimized values of input parameters are: η = 13.30 %; FF = 67.29 %; Voc = 0.764 V and Jsc = 25.86 mAcm−2. This detailed study will open doorways for the development of OIP solar cells in practice.

Fig. 2.

I–V characteristics of the proposed OIP solar cell.

Moreover, the external quantum efficiency (EQE) of the OIP solar cell over the entire spectrum is plotted in Fig. 3. The curve shows that the short wavelength EQE is less due to recombination at the front surface. The EQE is maximum at around 350 nm because high energy photons deliver a larger diffusion length to the carriers. Further, the lower energy photons correspond to smaller diffusion lengths causing higher recombination photogenerated carriers. So, the EQE is decreased for larger wavelengths due to increased recombination of photogenerated carriers [46].

Fig. 3.

The external quantum efficiency of the OIP cell for the entire spectrum.

The results and further discussion from the physics point of view of the proposed OIP device are as follows.

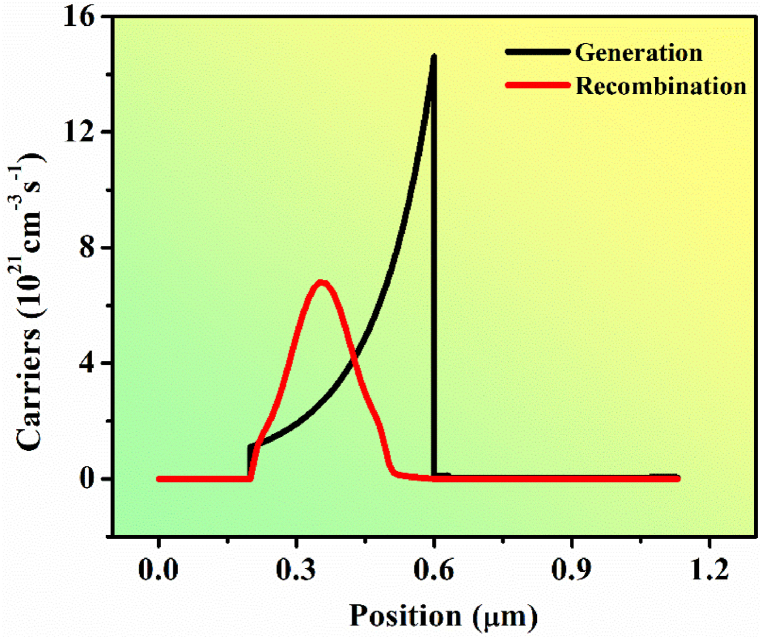

4.1. Generation and recombination in OIP cell

We observed the generation and recombination of carriers inside the device as presented in Fig. 4. Mostly the generation of carriers takes place in the absorber layer which is from 0.2 μm to 0.6 μm (0.4 μm thickness). The generation increases exponentially from HTL/active interface (IF1) which is at 0.2 μm to active/ETL interface (IF2) which is at 0.6 μm. From the curve, we can see that the maximum carrier generation rate is near the surface which is facing towards the sun. Besides the active layer, the generation rate is negligible. Also, the recombination rate is high in the active layer but negligible in other layers. This significant recombination rate in the active layer may be due to the presence of the defect states in the active layer. So, the current in the cell is only due to the generated carriers left after the recombination which flows through the electrodes at the front and rear. So, HTL only helps the current carriers and better transportation between the active and back metal electrodes.

Fig. 4.

Generation and recombination in the entire OIP cell (from rear to front).

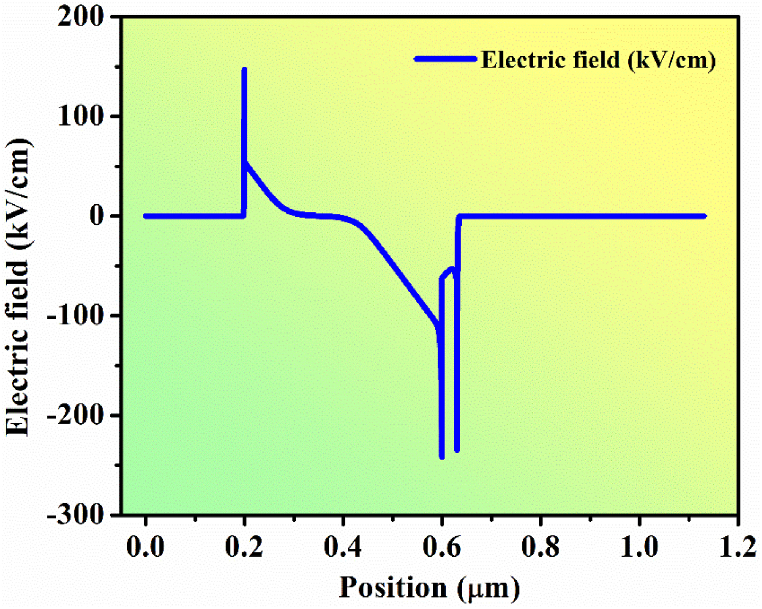

4.2. Electric field distribution in OIP cell

In Fig. 5 the electric field is plotted as a function of the position in the OIP cell. From the figure, it can be seen that finite electric fields exist only around the active layer and elsewhere it is almost negligible. At HTL/active interface (IF1) which is at 0.2 μm, the electric field is positive due to the p + type HTL and the p-type active layer. Whereas at active/ETL interface (IF2) which is at 0.6 μm, the electric field is negative because p-type active with n-type ETL. The positive electric field at the IF1 guides the holes towards the back and the negative electric field guides the electrons towards the front.

Fig. 5.

Electric field with the position of the proposed OIP cell from rear to front.

4.3. Effect of hole transport layer parameters

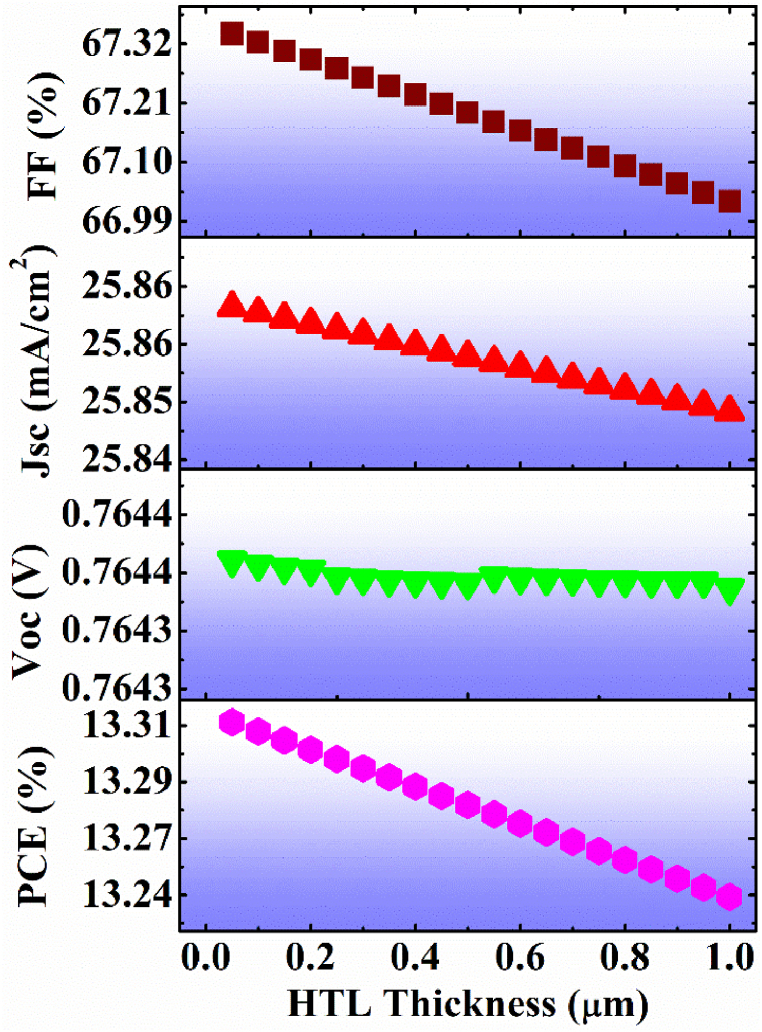

4.3.1. Effect of the thickness of the HTL

The variation of the performance parameters like PCE, FF, Jsc, and Voc of the proposed cell is observed as a function of the thickness of the organic HTL and depicted in Fig. 6. With the varying HTL thickness parameter (ranging from 0.05 to 1.0 μm), the result shows that Voc and Jsc are almost independent of the thickness having values of 0.764 V and 25.86 mAcm−2, respectively. While the values of FF and PCE show a slight reduction from 67.34 % to 67.03 % and 13.31 %–13.24 %, respectively. This slight reduction in FF and PCE parameters is due to the increase in the recombination of the excitons in the HTL layer. Since the relative dielectric permittivity of the HTL is less than that of the active layer (absorber layer) when the excitons generated in the active layer diffuse to the HTL layer, the exciton constituents (electron and hole) attract each other with more Coulomb attractive force than that in the active layer, therefore some of the exciton constituents get recombined. So, when the thickness of the HTL increases, there is a larger distance to be collected at electrodes, also there is more time before collecting at electrodes. Therefore, the exciton recombination increases with HTL thickness consequently, the PCE of the proposed cell reduces. Thus, the optimized value of the HTL thickness of the proposed cell is kept at 0.2 μm for further simulation.

Fig. 6.

Variation in HTL thickness for performance parameters of OIP cell.

4.3.2. Electron affinity of HTL

For optimization purposes, the electron affinity of the HTL of the concerned cell varied from 1.6 to 2.5eV, and the observed values of performance parameters of the cell are plotted in Fig. 7. Fig. 7 unfolds the behavior that all performance parameters first increase up to 2.3eV thereafter get saturated. In this process, Jsc increases from 23.96 to 27.25 mAcm−2, Voc from 0.314 to 0.928 V, FF from 52.98 to 71.57 %, and PCE from 3.99 to 18.10 %. These augmenting results are due to the smooth transition of the carriers at the interface of the HTL layer and the active layer. At the interface, the conduction band offset and the valence band offset get minimized, which helps the transition of the electrons in the conduction band from HTL to the active layer and the holes in the valence band from the active layer to HTL. These offsets of conduction and the valence band are explained using equations (6), (7)). Thus, the effective electron affinity of the (HTL) is 2.3eV which is responsible for the smooth transition of the carriers at the interface of the active and the HTL layer which can provide a maximum PCE of about 17.56 %.

Fig. 7.

Electron affinity of the HTL layer variations concerning the performance parameters of OIP cell.

4.3.3. Shallow acceptor concentration of the HTL

The electrical effect of the HTL layer on the output of the proposed cell is represented using the optimization of the shallow acceptor concentration (doping density) of the HTL layer. In our simulation study, we varied the shallow acceptor concentration of the HTL from 2 × 1018cm−3 to 1 × 1022cm−3, and the obtained result is shown in Fig. 8. Fig. 8 reveals that all performance parameters get enhanced with an increase in doping concentration. The Jsc increased from 25.68 to 26.29 mAcm−2, and the Voc from 0.717 to 0.904 V. This enhancement in the Jsc and Voc, is observed due to an increase in the conductivity of the cell (2019). As the acceptor concentration of the HTL layer increases, there is more hole concentration available which creates more charge difference around the interface of the active and the HTL layer, and this charge difference adds up to the conduction of the carriers at the interface and thus the conductivity of the cell increases which can be explained by equation (8).

Fig. 8.

Effect of shallow acceptor density of hole transport layer (HTL) on OIP cell performance parameters.

4.3.4. Effect of hole mobility of HTL

As the mobilities of the carriers in the different layers of the solar cell also affect the carrier transport in the cell. The contribution of hole mobilities in the HTL is more than that of the electron mobilities because there is a larger number of holes than electrons in the HTL. This is the reason we have plotted the device performance parameters with the hole mobilities of the HTL layer, which is shown in Fig. 9. From Fig. 9, we can see that the Voc is almost uniform at 0.764 V with hole mobility and thus show independent behavior. The other parameters show a little increase, such as Jsc from 25.85 to 25.86 mAcm−2, FF from 67.22 to 67.34 %, and PCE from 13.28 to 13.31 %. This shows that the hole mobilities of the organic HTL in the organic perovskite CH3NH3SnI3 solar cell have less impact on the device performance.

Fig. 9.

Effect of the hole mobility (μh) of HTL on the OIP cell parameters.

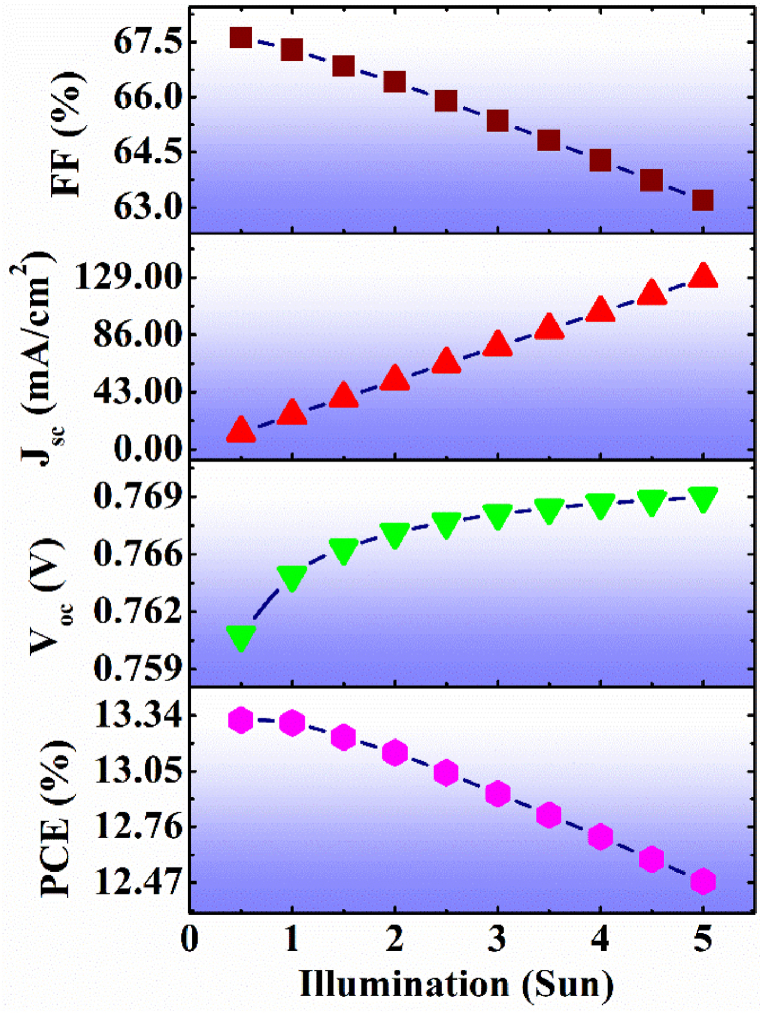

4.4. Effect of environmental condition (illumination intensity)

The environmental conditions like the illumination intensity of the sun at different altitudes of the globe are different. Therefore, the behavior of the device under temperature and illumination intensities of the sun is studied here. The photogenerated current in the solar cell is due to the transportation of photogenerated carriers through the cell, and these carriers are generated by the absorption of photons of incident illumination. However, the generation rate of the photogenerated carriers depends upon the intensity of the incident sunlight. This is the reason the illumination-dependent simulation study has been performed for the illumination intensity ranging 0.5 to 5 Sun (where 1 Sun = 1000Wm-2), and the obtained result is shown in Fig. 10. The figure shows that the Jsc increases consistently from (12.94–128.38 mAcm−2), and Voc also increases from (0.760–0.768 V). But the FF value decreases from (67.61–63.18 %), and the PCE value also decreases from (13.31–12.47 %). The increase in the Jsc value is due to the enhancement in the saturation current due to the larger amount of photogenerated current in the device. An almost similar trend of all the four performance parameters Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE for an organic solar cell with illumination intensity was also reported by Ryu et al. [47].

Fig. 10.

Effect of the different sun intensities on the performance parameter of the OIP cell.

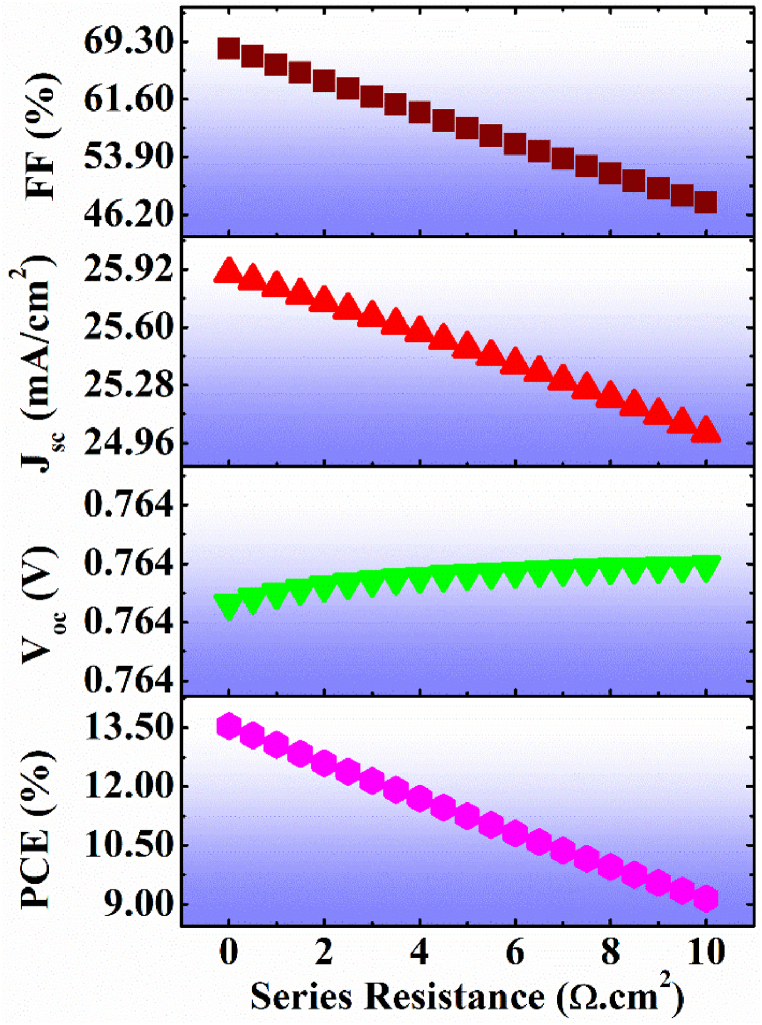

4.5. Effect of series and shunt resistance

The series and shunt resistance of the device is dependent on the different physical conditions and on the surrounding conditions of the cell. Therefore, we have analyzed the variation in the performance parameters of the proposed device by varying series and shunt resistance. Fig. 11 shows the effect of the series resistance on Voc, Jsc, FF, and the PCE of the device. The figure reveals that all the parameters decrease with the series resistance, but the Voc is almost constant, and the reason is well explained by its definition. The Jsc changes from (25.89–25.01 mAcm−2), FF from (68.38–47.82 %), and PCE from (13.53–9.14 %). With an increase in the series resistance, the Jsc decreases because higher series resistance provides a hindrance to the transportation of carriers through the cell. Further, the FF diminishes due to a decrease in maximum power delivered by the solar cell, which also deteriorates the PCE of the cell. Therefore, the series resistance of organic photovoltaics under study is kept at 0.5Ωcm2. Fig. 12 reveals the effect of shunt resistance on cell performance. The Voc value is almost constant, and the reason is defined by self-definition. The Jsc shows a substantial small change (25.73–25.85 mAcm−2), and the FF and PCE values have a remarkable change from (51.28–67.29 %) and (9.71–13.30 %), respectively. The shunt resistance acts as an alternate path for the photogenerated current in the device. Thus, the low shunt resistance allows more photogenerated currents to flow through it thereby reducing the Jsc, and alternately the increase in the shunt resistance enhances the Jsc value of the cell. The increase in the FF can be explained by equation (12), as mentioned in section 3.2.

Fig. 11.

Effect of series resistance on the proposed OIP cell performance.

Fig. 12.

Effect of shunt resistance on the proposed OIP cell performance.

4.6. Comparison/validation of the OIP solar cell configuration

The following Table 3 shows the relevant/similar theoretical/simulated and experimental performance of CH3NH3SnI3-based organic-inorganic perovskite solar cells with different ETLs and HTLs. At defect density of 2 × 1015cm−3 and shallow acceptor density of 3 × 1016cm−3 the proposed cell has PCE = 13.30 %, FF = 67.29 %, Voc = 0.764 V, and Jsc = 25.86 mAcm−2.

Table 3.

Comparison/Validation between the theoretical/experimental results reported in different works of reputed pieces of literature.

| S. No. | Configuration | Voc (V) | Jsc (mAcm−2) | FF (%) | PCE (%) | Method | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2. | TCO/TiO2/CH3NH3SnI3/ZnTe | 0.79 | 16.83 | 63.26 | 8.41 | Experimental | [48] |

| 3. | TiO2/CH3NH3SnI3/Spiro-OMeTAD | 0.880 | 16.80 | 42 | 6.4 | Experimental | [49] |

| 4. | FTO/CdZnS/MASnI3/MASnBr3 | 0.670 | 26.54 | 65.02 | 11.53 | Simulation | [50] |

| 5. | FTO/TiO2/CH3NH3SnI3/Spiro-OMeTAD | 0.764 | 25.85 | 67.29 | 13.30 | Our present study |

5. Conclusions

An OIP solar cell with a novel combination of CH3NH3SnI3 as an active layer, TiO2 as an ETL, and Spiro-OMeTAD organic HTL is proposed for the simulation study. The optimization of the HTL is done using SCAPS-1D software. The optimization of HTL revealed that the PCE of the modeled OIP solar cell reached up to 18.10 % at the electron affinity value (2.5eV) of the HTL. Further, for the optimized value of the acceptor doping level of the HTL, the best-obtained value of PCE is 16.58 %. The impact of the thickness and the hole mobility of the HTL shows the least effect on the performance of the proposed cell. Further, for the depth study of the proposed cell, the effect of physical, electrical, and operating environmental conditions has been observed. The results suggest that the cell performance was very efficient for the moderate illumination intensity of about 1 sun, and the cell performed at best PCE values for low series and high shunt resistance. Finally, this novel configuration is suited well when compared to other similar configurations experimentally as well as theoretically. In addition, the experimental realization/fabrication of the novel proposed solar device configuration by submitting the proposals to the leading government/industries based on the present research studies in the next phase of our task. This technology must be integrated into existing solar cell technology as we have proposed tin-based organic-inorganic perovskite which is a non-toxic, abundant, and environmentally friendly leading material.

Funding

Not Applicable.

Ethical approval

This is the first original research article. This original work has not been published or offered for publication in any other journal. This theoretical, computational, and simulation study does not belong to the extension of any earlier work.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Yes.

Data and code availability

Data will be made available on request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ankita Srivastava: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Atish Kumar Sharma: Writing – original draft, Validation, Software, Data curation. Prakash Kumar Jha: Visualization, Validation, Software, Data curation. Manish Kumar: Formal analysis. Nitesh K. Chourasia: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Ritesh Kumar Chourasia: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Dr. Marc Burgelman, University of Gent, Belgium, for the SCAPS-1D simulation software.

Contributor Information

Nitesh K. Chourasia, Email: niteshphyzics@gmail.com.

Ritesh Kumar Chourasia, Email: riteshphyzics@gmail.com, dr.riteshchaurasia@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Kim G.M., Sato H., Ohkura Y., Ishii A., Miyasak T. Phenethylamine-based interfacial dipole engineering for high Voc triple-cation perovskite solar cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022;12 doi: 10.1002/aenm.202102856. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma A.K., Srivastava A., Jha P.K., Kumar R., Kumar M., Kulriya P.K., Chourasia N.K., Chourasia R.K. Bulk/interface defects engineering and comparative performance analysis of p-Si/n-CdS/ALD-ZnO heterojunction solar cell. Energy Technol. 2023;11 doi: 10.1002/ente.202300169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim T.W., Uchida S., Kim M., Cho S.G., Kim S.J., Kondo T., Segawa H. Phase control of organometal halide perovskites for development of highly efficient solar cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2023;15(18):21974–21981. doi: 10.1021/acsami.2c22769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma A.K., Kumar R., Jha P.K., Kumar M., Chourasia N.K., Chourasia R.K. Bulk parameters effect and comparative performance analysis of p-Si/n-CdS/ALD-ZnO solar cell. Silicon. 2023;15:6497–6508. doi: 10.1007/s12633-023-02518-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehra S., Mamta, Tawale J., Gupta G., Singh V.N., Srivastava A.K., Sharma S.N. Evaluating Pb-based and Pb-free halide perovskites for solar-cell applications: a simulation study. Heliyon. 2024;10(12) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e33243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pandya A., Sharma A.K., Bhatt M., Jha P.K., Sangani K., Chourasia N.K., Chourasia R.K. A synergy of Cr2O3 with eco-friendly and thermally stable CsSnCl3 perovskite for solar energy storage: density functional theory and SCAPS-1D analysis. Energy Storage. 2024;6(5) doi: 10.1002/est2.70001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang R., Mujahid M., Duan Y., Wang Z., Xue J., Yang Y. A review of perovskites solar cell stability. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019;29(47) doi: 10.1002/adfm.201808843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim Hui-Seon, Lee Jin-Wook, Yantara Natalia, Boix Pablo P., Kulkarni Sneha A., Mhaisalkar Subodh, Grätzel Michael, Park Nam-Gyu. High-efficiency solid-state sensitized solar cell-based on submicrometer rutile TiO2 nanorod and CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite sensitizer. Nano Lett. 2013;13(6):2412–2417. doi: 10.1021/nl400286w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryu S., Noh J.H., Jeon N.J., Chan Kim Y.C., Yang W.S., Seo J., Seok S.I. Voltage output of efficient perovskite solar cells with high open-circuit voltage and fill factor. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014;7(8):2614–2618. doi: 10.1039/C4EE00762J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitzi D.B., Feild C.A., Harrison W.T.A., Guloy A.M. Conducting tin halides with a layered organic-based perovskite structure. Nature. 1994;369:467–469. doi: 10.1038/369467a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saliba M., Matsui T., Domanski K., Seo J.Y., Ummadisingu A., Zakeeruddin S.M., Correa-Baena J.P., Tress W.R., Abate A., Hagfeldt A., Gratzel M. Incorporation of rubidium cations into perovskite solar cells improves photovoltaic performance. Science. 2016;354(6309):206–209. doi: 10.1126/science.aah5557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee M.M., Teuscher J., Miyasaka T., Murakami T.N., Snaith H.J. Efficient hybrid solar cells based on meso-super structured organometal halide perovskites. Science. 2012;338(6107):643–647. doi: 10.1126/science.1228604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pathak C.S., Chang B.J., Song S. Review on scanning probe microscopy analysis for perovskite materials and solar cells. Dyes Pigments. 2023;218 doi: 10.1016/j.dyepig.2023.111469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaikh J.S., Shaikh N.S., Mishra Y.K., Kanjanaboos P., Shewale P.M., Sabale S., Praserthdam S., Lokhande C.D. Low-cost Cu-based inorganic hole transporting materials in perovskite solar cells: recent progress and state-of-art developments. Mater. Today Chem. 2021;20 doi: 10.1016/j.mtchem.2021.100427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao F., Li C., Qin L., Zhu L., Huang X., Liu H., Liang L., Hou Y., Lou Z., Hu Y., Teng F. Enhanced performance of tin halide perovskite solar cell by addition of lead thiocyanate. RSC Adv. 2018;8(25):14025–14030. doi: 10.1039/C8RA00809D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyu M., Yun J.H., Chen P., Hao M., Wang L. Addressing toxicity of lead: progress and applications of low-toxic metal halide perovskites and their derivatives. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017;7(15):1602512–1602537. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201602512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burschka J., Pellet N., Moon S.J., Baker R.H., Gao P., Nazeeruddin M.K., Grätzel M. Sequential deposition as a route to high-performance perovskite sensitized solar cells. Nature. 2013;499:316–319. doi: 10.1038/nature12340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawash Z., Ono L.K., Qi Y. Recent advances in spiro-MeOTAD hole transport material and its applications in organic-inorganic halide perovskite solar cells. Adv. Mater. Interfac. 2018;5(1) doi: 10.1002/admi.201700623. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park N.G. Organometal perovskite light absorbers toward a 20% efficiency low-cost solid-state mesoscopic solar cell. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013;4(15):2423–2429. doi: 10.1021/jz400892a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snaith H.J. Perovskites: the emergence of a new era for low cost, high-efficiency solar cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013;4(21):3623–3630. doi: 10.1021/jz4020162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sa R., Liu D., Chen Y., Ying S. Mixed-cation mixed-metal halide perovskites for photovoltaic applications: a theoretical study. ACS Omega. 2020;5(8):4347–4351. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.9b04484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santos I.M.D.L., Marrero H.J.C., Sánchez M.A.R., Difur L.H., Rodríguez F.J.S., Courel M., Hu H. Optimization of CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite solar cells: a theoretical and experimental study. Sol. Energy. 2020;199:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.solener.2020.02.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li X., Yang J., Jiang Q., Lai H., Li S., Xin J., Chu W., Hou J. Low-temperature solution-processed ZnSe electron transport layer for efficient planar perovskite solar cells with negligible hysteresis and improved photostability. ACS Nano. 2018;12(6):5605–5614. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b01351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devi C., Mehra R. Device simulation of lead-free MASnI3 solar cell with CuSbS2 (copper antimony sulfide) J. Mater. Sci. 2019;54:5615–5624. doi: 10.1007/s10853-018-03265-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lazemi M., Asgharizadeh S., Bellucci S. A computational approach to interface engineering of lead-free CH3NH3SnI3 highly-efficient perovskite solar cells. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018;20(40):25683–25692. doi: 10.1039/C8CP03660H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin L., Jiang L., Li P., Fan B., Qiu Y. A modelled perovskite solar cell structure with a Cu2O hole transporting layer enabling over 20% efficiency by low-cost low temperature processing. J. Phys. Chem. Solid. 2019;124:205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jpcs.2018.09.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou H., Chen Q., Li G., Luo S., Song T.B., Duan H.S., Hong Z., You J., Liu Y., Yang Y. Interface engineering of highly efficient perovskite solar cells. Science. 2014;345(6196):542–546. doi: 10.1126/science.1254050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang H.Y., Rho W.Y., Lee S.K., Kim S.H., Hahn Y.B. TiO2 nanoparticles/nanotubes for efficient light harvesting in perovskite solar cells. Nanomaterials. 2019;9(3):326–335. doi: 10.3390/nano9030326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Omarova Z., Yerezhep D., Aldiyarov A., Tokmoldin N. In Silico investigation of the impact of hole-transport layers on the performance of CH3NH3SnI3 perovskite photovoltaic cells. Crystals. 2022;12(5):699. doi: 10.3390/cryst12050699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walter T., Herberholz R., Müller C., Schock H.W. Determination of defect distributions from admittance measurements and application to Cu(In, Ga)Se2 based heterojunctions. J. Appl. Phys. 1996;80(8):4411–4420. doi: 10.1063/1.363401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anwar F., Mahbub R., Satter S.S., Ullah S.M. Effect of different HTM layers and electrical parameters on ZnO nanorod-based lead-free perovskite solar cell for high-efficiency performance. Int. J. Photoenergy. 2017;2017(1) doi: 10.1155/2017/9846310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iefanova A., Adhikari N., Dubey A., Khatiwada D., Qiao Q. Lead-free CH3NH3SnI3 perovskite thin-film with p-type semiconducting nature and metal-like conductivity. AIP Adv. 2016;6(8) doi: 10.1063/1.4961463. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Müller M. In: Handbook of Optoelectronic Device Modeling and Simulation. Piprek Joachim., editor. CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group; New York: 2018. Solar cell fundamentals; pp. 383–413. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sze S.M. second ed. Bell Laboratories, Incorporated Murray Hill; New Jersey: 2007. Physics of Semiconductor Devices. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abena A.M.N., Ngoupo A.T., Abega F.X.A., Ndjaka J.M.B. Numerical investigation of solar cells based on hybrid organic cation perovskite with inorganic HTL via SCAPS-1D. Chin. J. Phys. 2022;76:94–109. doi: 10.1016/j.cjph.2021.12.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar M., Raj A., Kumar A., Anshul A. Computational analysis of bandgap tuning, admittance and impedance spectroscopy measurements in lead-free MASnI3 perovskite solar cell device. Int. J. Energy Res. 2022;46(8):11456–11469. doi: 10.1002/er.7942. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu H., Yuan F., Zhou D., Liao X., Chen L., Chen Y. Hole transport layers for organic solar cells: recent progress and prospects. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2020;8(23):11478–11492. doi: 10.1039/D0TA03511D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kasap S.O. fourth ed. University of Saskatchewan Canada; 2018. Principles of Electronic Materials and Devices. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh P., Ravindra N.M. Temperature dependence of solar cell performance-an analysis. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cell. 2012;101:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.solmat.2012.02.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharma A.K., Chourasia N.K., Chourasia R.K. Optical, temperature, and bulk analysis theoretically in p-Si/n-CdS heterojunction solar cell. Mater. Today: Proc. 2022;67:632–636. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2022.06.094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Varshni Y.P. Temperature dependence of the energy gap in semiconductors. Physica. 1967;34(1):149–154. doi: 10.1016/0031-8914(67)90062-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pässler R. Parameter sets due to fittings of the temperature dependencies of fundamental bandgaps in semiconductors. Phys. stat. sol. b. 1999;216(2):975–1007. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3951(199912)216:2%3C975::AID-PSSB975%3E3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jha P.K., Chourasia N.K., Sharma A.K., Chourasia R.K. Optimization of electrical properties for performance analysis of p-Si/n-CdS/ITO heterojunction photovoltaic cell. Mater. Today: Proc. 2022;67:620–624. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2022.05.577. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sharma A.K., Chourasia N.K., Jha P.K., Kumar R., Kumar M., Chourasia R.K. Characteristic features and performance investigations of a PTB7:PC71BM/PFN: Br pure organic solar cell using SCAPS-1D. J. Electron. Mater. 2023;52:4302–4311. doi: 10.1007/s11664-022-10202-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jha P.K., Chourasia N.K., Srivastava A., Sharma A.K., Kumar R., Sharma S., Kumar M., Chourasia R.K. Study of eco-friendly organic-inorganic heterostructure CH3NH3SnI3 perovskite solar cell via SCAPS simulation. J. Electron. Mater. 2023;52:4321–4329. doi: 10.1007/s11664-023-10267-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frohna K., Stranks S.D. In: Handbook of Organic Materials for Electronic and Photonic Devices. second ed. Ostroverkhova O., editor. University of Cambridge; Cambridge, United Kingdom: 2019. 7 - hybrid perovskites for device applications; pp. 211–256. (Woodhead Publishing Series in Electronic and Optical Materials, Cavendish Laboratory). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ryu S., Ha N.Y., Ahn Y.H., Park J.Y., Lee S. Light intensity dependence of organic solar cell operation and dominance switching between Shockley-Read-Hall and bimolecular recombination losses. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-96222-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kumari K., Jana A., Dey A., Chakrabarti T., Sarkar S.K. Lead-free CH3NH3SnI3 based perovskite solar cell using ZnTe nanoflowers as the hole transport layer. Opt. Mater. 2021;111 doi: 10.1016/j.optmat.2020.110574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Noel N.K., Stranks S.D., Abate A., Wehrenfennig C., Guarnera S., Haghighirad A.A., Sadhanala A., Eperon G.E., Pathak S.K., Johnston M.B., Petrozza A., Herz L.M., Snaith H.J. Lead-free organic-inorganic tin halide perovskites for photovoltaic applications. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014;7(9):3061–3068. doi: 10.1039/C4EE01076K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baig F., Khattak Y.H., Marí B., Beg S., Ahmed A., Khan K. Efficiency enhancement of CH3NH3SnI3 solar cells by device modeling. J. Electron. Mater. 2018;47:5275–5282. doi: 10.1007/s11664-018-6406-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.