Abstract

The replication of human rhinovirus 2 (HRV2), a positive-stranded RNA virus belonging to the Picornaviridae, requires a virus-encoded RNA polymerase. We have expressed in Escherichia coli and purified both a glutathione S-transferase fusion polypeptide and an untagged form of the HRV2 RNA polymerase 3Dpol. Using in vitro assay systems previously described for poliovirus RNA polymerase 3Dpol (J. B. Flanegan and D. Baltimore, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:3677–3680, 1977; A. V. Paul, J. H. van Boom, D. Filippov, and E. Wimmer, Nature 393:280–284, 1998), we have analyzed the biochemical properties of the two different enzyme preparations. HRV2 3Dpol is both template and primer dependent, and it catalyzes two types of synthetic reactions in the presence of UTP, Mn2+, and a poly(A) template. The first consists of an elongation reaction of an oligo(dT)15 primer into poly(U). The second is a protein-priming reaction in which the enzyme covalently links UMP to the hydroxyl group of tyrosine in the terminal protein VPg, yielding VPgpU. This precursor is elongated first into VPgpUpU and then into VPg-linked poly(U), which is identical to the 5′ end of picornavirus minus strands. The two forms of the enzyme are about equally active both in the oligonucleotide elongation and in the VPg-primed reaction. Various synthetic mutant VPgs were tested as substrates in the VPg uridylylation reaction.

Rhinoviruses belong to the family of Picornaviridae, a large group of plus-strand RNA viruses with different host ranges and disease symptoms but similar genetic organizations and replication strategies (50, 60). This virus family has been subdivided into nine genera: Enterovirus, Rhinovirus, Cardiovirus, Aphtovirus, Hepatovirus, Parechovirus, Erbovirus, Teschovirus, and Kobuvirus (55). Rhinoviruses, with more than a hundred serotypes (23), are considered to be the most important causative agents of the common cold, for which no effective treatment or prevention has yet been developed (6, 22, 49). They can be classified into two groups based on their use of cellular receptors. The majority of human rhinoviruses (HRVs) bind to human intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) (21, 57), while those belonging to the minor group, including HRV2, bind to various members of the low-density lipoprotein receptor gene family (27, 29).

HRV2, like other picornaviruses, is a small icosahedral particle composed of 60 copies each of the four capsid proteins VP1 to VP4, which enclose a plus-strand RNA genome covalently linked at the 5′ end to the terminal protein VPg (33, 34, 50, 63). Replication of the viral RNA takes place in membranous vesicles in the cytoplasm of the infected host cell (31, 32, 68). Three RNA species have been recognized in cells infected with HRV2 (68). These include a single-stranded RNA of a length similar to that of genomic RNA; a double-stranded RNA, the replicative form (RF); and a multistranded structure, called the replicative intermediate (RI) (68). It is generally accepted that picornavirus RNA replication is a two-step process carried out primarily by the viral RNA polymerase in conjunction with other viral and possibly also cellular proteins (reviewed in references 1 and 68). First the parental RNA is transcribed into a complementary minus strand, which is then used as the template for the synthesis of the progeny plus strands. Although the basic steps of RNA replication have been well defined, very little is known about the details of these processes. Most of the information accumulated thus far has been derived from studies of poliovirus, whose properties and replication are believed to parallel those of the other members of the entire picornavirus family.

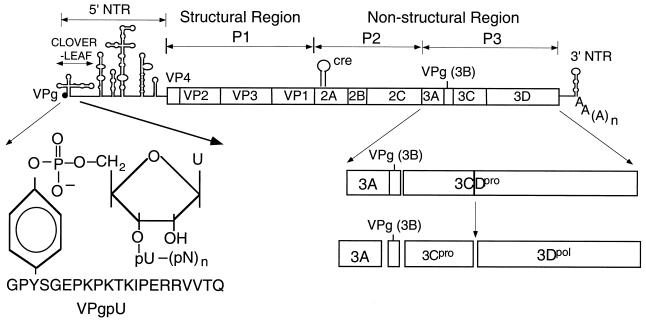

The RNA genome of HRV2 (7,151 nucleotides [nt]) contains a long 5′ nontranslated region (5′ NTR), a single large open reading frame, and a short 3′ NTR terminating with a poly(A) tail (52) (Fig. 1). The 5′ phosphate of the terminal UMP in picornaviral RNA is linked in a phosphodiester bond to the hydroxyl group of a tyrosine in VPg (2, 48) (Fig. 1). The first segment of the 5′ NTR forms a cloverleaf-like structure (47) that is required for plus-strand RNA synthesis (3, 4, 67) and possibly for progression from translation to replication (16). The remainder of the 5′ NTR consists of a large and highly structured segment, the internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) (30), whose primary function is to direct translation (7). The polyprotein, containing one structural (P1) and two nonstructural (P2 and P3) domains, is processed to mature viral proteins by viral proteinases 2Apro, 3Cpro, and 3CDpro (reviewed in references 25; 52, and 54). All of the nonstructural proteins and some of their precursors are required for RNA replication, with proteins of the P3 domain most directly involved in the process of RNA synthesis. These include a small hydrophobic and membrane-binding protein, 3A, with its precursor, 3AB; the terminal protein VPg (3B); proteinase 3CDpro; and the RNA polymerase 3Dpol (reviewed in references 1 and 65). The two important precursors, 3AB and 3CDpro, possess RNA binding activities that are essential for viral replication (3, 4, 26, 40, 67).

FIG. 1.

Structure of HRV2 genomic RNA. The single-stranded RNA genome of HRV2 is shown with the terminal protein VPg (3B) at the 5′ end of the 5′ NTR. The attachment site of the 5′-terminal UMP of the RNA to the tyrosine of VPg is shown enlarged. The polyprotein contains structural (P1) and nonstructural (P2 and P3) domains. Vertical lines within the polyprotein box represent proteinase cleavage sites. Processing of the P3 domain by proteinase 3CDpro is shown enlarged. The location of the cre in the 2Apro coding region is indicated (17).

It was nearly 30 years ago that an RNA polymerase activity was first detected in membrane-bound complexes of HRV2-infected HeLa cells (68). Subsequently. this activity was partially purified, and the enzyme was shown to be template and primer dependent in vitro (37). In these studies either homopolymeric or viral RNA sequences were used as templates with oligonucleotide primers that were elongated into complementary strands. At about the same time, other in vivo and in vitro studies with poliovirus suggested that VPg might serve as a primer in the initiation of picornaviral RNA replication (64). This possibility was supported by the observation that virus-infected HeLa cells contain VPgpUpU, in which VPg is covalently linked to UMP (10). In addition, the synthesis of VPgpU and VPgpUpU could be achieved in vitro by using membranous replication complexes isolated from virus-infected cells (58, 59, 62). Recently it was directly shown that the RNA polymerase of poliovirus possesses a synthetic activity in vitro that catalyzes the linkage of UMP to the hydroxyl group of tyrosine in VPg, yielding VPgpU and VPgpUpU (41). The final product in the uridylylation of VPg on a poly(A) template is VPg-linked poly(U) (41), the 5′ end of viral minus strands (38).

In addition to the nonstructural proteins, RNA replication also requires important cis-replicating elements located in the 5′ NTR, the 3′ NTR, possibly in the IRES, and in the coding sequences of picornaviral RNAs (reviewed in references 1 and 66). The exact functions of the 5′ cloverleaf structure, the IRES, and the 3′ NTR poly(A) in picornaviral RNA replication are not yet known. The internal replication signals (cre) of different picornaviruses all consist of a relatively simple hairpin structure with a conserved AAACA sequence in the loop (20, 35, 36, 42, 46), which is essential for initiation of minus-strand synthesis (20, 36). We have recently identified the function of this motif in the cre(2C) of poliovirus type 1 Mahoney [PV1(M)] RNA as the primary template for the synthesis of VPgpU and VPgpUpU by 3Dpol (42, 46).

In order to gain more insight into the properties of the enzyme responsible for RNA synthesis by HRV2, a virus belonging to a genus of Picornaviridae different from Enterovirus, we have expressed in Escherichia coli and purified two different forms of HRV2 3Dpol, one with a glutathione S-transferase (GST) tag and one with only an extra N-terminal methionine. In this study we used both forms of purified HRV2 3Dpol to test their activities on a poly(A) template in the oligonucleotide- and VPg-primed reactions. Our accompanying paper (17) describes the synthetic activity of HRV2 3Dpol on its cognate cis-replicating element that is located in the coding sequence of protein 2Apro.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of plasmids.

HRV2 cDNA (pT7HRV2) (12) nucleotide sequences given for plasmids or oligonucleotides refer to the full-length (nt 1 to 7151) plus-strand HRV2 cDNA sequence (52). All PCR fragments used for cloning were sequenced to ensure their accuracy.

(i) pGEX-HRV2 3D.

The sequence for 3Dpol was amplified from pT7HRV2 by PCR with oligonucleotide primers 5′-CCCGGATCCGGCCAAATAACGTTATCA-3′ (plus-strand sequence) and 5′-GGGGAATTCTTAAAATTTTTCATACCACTC-3′ (minus-strand sequence). The amplified product was cut with BamHI and EcoRI and was cloned into the same sites of pGEX-2T (Pharmacia Biotech). The resulting plasmid (pGEX-HRV2 3D) contained the HRV2 3Dpol coding sequence fused at its N terminus to the 26-kDa GST from Schistosoma japonicum.

(ii) pT5T-HRV2 3D.

The coding sequence for 3Dpol was amplified from pT7HRV2 by PCR using Pfu DNA polymerase and the oligonucleotide primers 5′-CCCATATGATGGGCCAAATAACGTTATCAAAG-3′ (plus-strand sequence) and 5′-CCGAATTCTTAAAATTTTTCATACCACTC-3′ (minus-strand sequence). The amplified product was cut with NdeI and EcoRI and was cloned into the same sites of pT5T (39). The resulting plasmid (pT5T-HRV2 3D) contained the HRV2 3Dpol sequence preceded by a methionine.

Peptides and proteins. (i) VPg peptides.

Wild-type (wt) and mutant synthetic VPg peptides were a generous gift of J. H. van Boom (41, 42, 46).

(ii) GST-HRV2 3Dpol.

GST-HRV2 3Dpol was purified as described elsewhere for PV1(M) GST-2C (43), except for the following modifications. E. coli strain BL21(DE3)pLysS was transformed with plasmid pGEX-HRV2 3D, and the protein was expressed at 16°C for 14 h. The yield of pure 3Dpol protein was about 3.5 mg/liter of bacterial culture.

(iii) HRV2 3Dpol and PV1(M) 3Dpol.

HRV2 3Dpol and PV1(M) 3Dpol were expressed in E. coli strain BL21(DE3)pLysS from pT5T-HRV2 3D and pT5T-PV1(M) 3D (39), respectively, and were purified as described elsewhere for PV1(M) 3Dpol by Pata et al. (39). The yield of pure HRV2 3Dpol was essentially the same as that of GST-HRV2 3Dpol (about 3.5 mg/liter of culture). Control proteins for HRV2 3Dpol were purified like HRV2 3Dpol, with the exception that the expression vector pT5T (39) did not contain the 3Dpol coding sequences.

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase assays. (i) VPgpU(pU) and VPg-poly(U) synthesis on a poly(A) template by HRV2 3Dpol and GST-HRV2 3Dpol.

The enzyme assay was the same as that previously described for PV1(M) 3Dpol (41) except for the pH of the buffer and the divalent cation. The standard reaction mixture (20 μl) for VPg uridylylation by HRV2 3Dpol contained 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), 0.2 mM manganese(II) acetate (MnAc2; Aldrich), 8% glycerol, 0.5 μg (0.35 μM) of poly(A) RNA template (∼200-nt - fragments; Pharmacia), 2 μg of synthetic HRV2 VPg (50 μM), 1 μg (1 μM) of purified 3Dpol, and 1 μCi of [α-32P]UTP (0.017 μM) (3,000 Ci/mmol; Dupont, NEN). The standard reaction mixture for VPg-poly(U) synthesis contained, in addition, 10 μM unlabeled UTP. Samples were incubated for 1 h at 30°C, and reactions were stopped by addition of 5 μl of gel-loading buffer (Bio-Rad) and analyzed on Tris–Tricine–sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels (Bio-Rad) with 13.5% polyacrylamide. Gels were dried at 68°C for 2 h without fixing and autoradiographed for 1 h (Kodak Biomax MS film). Reaction products were quantitated by measuring the amount of [α-32P]UMP incorporated into VPgpU(pU) and VPg-poly(U) products (Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager, Storm 860), and the data were translated into counts per minute with the help of a radioactive marker. VPgpU(pU) refers to the sum of VPgpU and VPgpUpU.

The assay with GST-HRV2 3Dpol was similar to that described above except that the standard reaction mixture for VPgpU(pU) synthesis contained 0.05 mM MnAc2 and that for VPg-poly(U) synthesis contained 0. 5 mM MnAc2 .

(ii) Oligo(dT)15-primed poly(U) synthesis on a poly(A) template.

The assay for oligo(dT)15-primed poly(U) synthesis was the same as that described above except that 50 ng of oligo(dT)15 primer (Boehringer Mannheim) replaced VPg.

RESULTS

Expression and purification of GST-HRV2 3Dpol and HRV2 3Dpol.

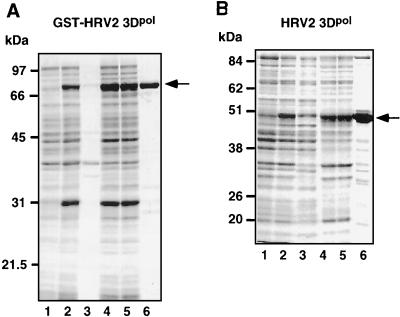

We have initially undertaken the expression in E. coli and purification of a GST-fusion polypeptide of HRV2 3Dpol (GST-HRV2 3Dpol). The protein, expressed in good yields, can be solubilized in 1% Triton X-100 and batch purified on glutathione-Sepharose beads to near-homogeneity. The fusion polypeptide has the expected molecular size of 76.5 kDa (Fig. 2A, lane 6). In order to rule out the possibility that an N-terminal GST tag interferes with the activity of the enzyme, we have subsequently also expressed in E. coli and purified HRV2 3Dpol without a tag. Previous studies have indicated that an extra methionine linked to the N-terminal glycine of PV1(M) 3Dpol is to a large extent processed off in the bacterial cell and that the activity of the resulting enzyme preparation is essentially the same as that of the wt protein (19). Therefore, we have proceeded to express in E. coli and purify HRV2 3Dpol with only an extra methionine linked to the N-terminal glycine of the 460-amino-acid 3Dpol polypeptide (Fig. 2B, lane 6). To distinguish this form from the GST fusion protein, we will refer to it as HRV2 3Dpol. The protein, with a molecular size of 50.5 kDa, was purified by ion-exchange chromatography to approximately 80% purity (Fig. 2B). Whether or not the minor fast-migrating bands of protein include degradation products of HRV2 3Dpol or contaminating bacterial proteins could not be determined, since no antibodies to this protein are available yet.

FIG. 2.

Purification of GST-HRV2 3Dpol and HRV2 3Dpol. (A) GST-HRV2 3Dpol was expressed in E. coli and purified to near-homogeneity as described in Materials and Methods. The purity of the enzymes was tested by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie-staining. Protein sizes (in kilodaltons) are given on the left. Shown are bacterial lysates before (lane 1) and after (lane 2) induction of GST-HRV2 3Dpol expression, the insoluble (lane 3) and soluble (lane 4) fractions of lysed bacteria expressing GST-HRV2 3Dpol, the soluble fraction after absorption to glutathione-Sepharose (lane 5), and the eluate containing GST-HRV2 3Dpol (lane 6). The major fraction corresponds to the 76.5-kDa GST-HRV2 3Dpol fusion protein. (B) HRV2 3Dpol was expressed in E. coli and purified as described in Materials and Methods. Shown are bacterial lysates before (lane 1) and after (lane 2) induction of HRV2 3Dpol expression, proteins that did not precipitate with 50% ammonium sulfate (lane 3), the flowthrough fraction of the sulphopropyl (SP)-Sepharose column (lane 4), 50 mM NaCl eluate of the SP-Sepharose column (lane 5), and 200 mM NaCl eluate of the SP-Sepharose column (lane 6). The major fraction corresponds to the 50.5-kDa HRV2 3Dpol protein.

Oligo(dT)15-primed poly(U) synthesis by GST-HRV2 3Dpol and HRV2 3Dpol

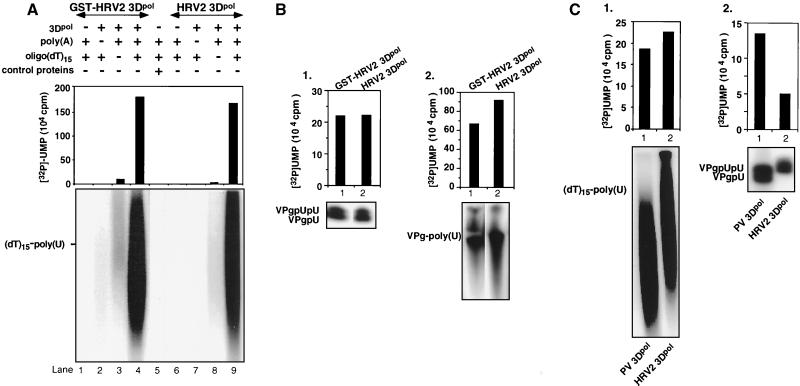

It has been previously shown by Morrow et al. (37) that HRV2 3Dpol isolated from virus-infected HeLa cells is active in an elongation reaction of an oligo(U) primer on a poly(A) template yielding poly(U). We have confirmed this observation with our enzyme preparations of HRV2 3Dpol, which were expressed in E. coli and purified. The two forms of 3Dpol were found to be about equally active in the synthesis of poly(U) on a poly(A) template (Fig. 3A; compare lane 4 with lane 9) in a reaction using UTP, Mn2+ as a cofactor, and oligo(dT)15, instead of oligo(U), as a primer. Both preparations of polymerases are template (Fig. 3A; compare lane 4 with lane 2 and lane 9 with lane 7) and primer (Fig. 3A, compare lane 4 with lane 3 and lane 9 with lane 8) dependent. We used a control plasmid, with no 3Dpol insert, to rule out the possibility that the RNA polymerase activity of the enzyme preparations is due to a contaminating bacterial protein. Purified proteins isolated from extracts of cells that were produced after the induction of the control plasmid had no detectable activity (Fig. 3A; compare lane 5 with lanes 4 and 9).

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the synthetic activities of GST-HRV2 3Dpol, HRV2 3Dpol, and PV1(M) 3Dpol. (A) Oligo(dT)15-primed poly(U) synthesis by GST-HRV2 3Dpol (lanes 1 to 4) and HRV2 3Dpol (lanes 6 to 9). Standard assays were used as described in Materials and Methods. Lanes 1 and 6, no enzyme; lanes 2 and 7, no poly(A) template; lanes 3 and 8, no oligo(dT)15; lanes 4 and 9, complete reaction mixtures. As a control for the enzymatic activity of HRV2 3Dpol, the empty pT5T vector was carried through the same expression and purification process as the pT5T vector containing the HRV2 3Dpol sequence (see Materials and Methods). Purified bacterial proteins were tested for polymerase activity (lane 5). (B) Synthesis of HRV2 VPgpU(pU) and VPg-poly(U) by GST-HRV2 3Dpol and HRV2 3Dpol. Standard assays for VPg-poly(U) synthesis were used as described in Materials and Methods. (Panel 1) VPgpU(pU) synthesis by GST-HRV2 3Dpol (lane 1) and HRV2 3Dpol (lane 2). (Panel 2) VPg-poly(U) synthesis by GST-HRV2 3Dpol (lane 1) and HRV2 3Dpol (lane 2). (C) Synthesis of (dT)15-poly(U) and VPgpU(pU) by PV1(M) 3Dpol and HRV2 3Dpol. The oligonucleotide-elongating and VPg-uridylylating activities of HRV2 3Dpol were measured as described in Materials and Methods, and that of PV1(M) 3Dpol was measured as described previously (41) except that the reaction mixture contained 0.5 mM Mn2+. Each enzyme was tested with its cognate VPg as a substrate. (Panel 1) (dT)15-poly(U) synthesis by PV1(M) 3Dpol (lane 1) and HRV2 3Dpol (lane 2). (Panel 2) VPgpU(pU) synthesis by PV1(M) 3Dpol (lane 1) and HRV2 3Dpol (lane 2). Quantified data are shown at the top, and autoradiographs are shown at the bottom.

VPgpU(pU) and VPg-poly(U) synthesis by HRV2 3Dpol and GST-HRV2 3Dpol.

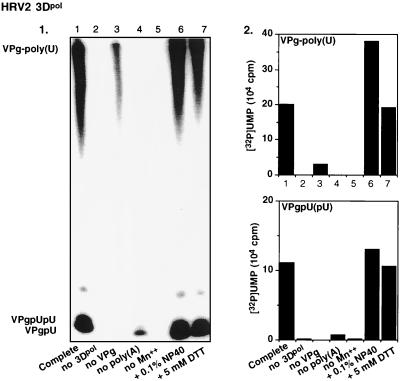

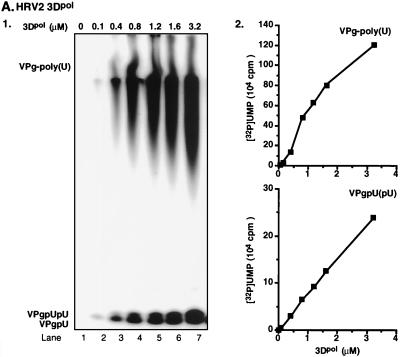

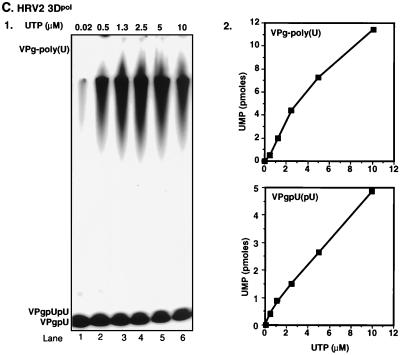

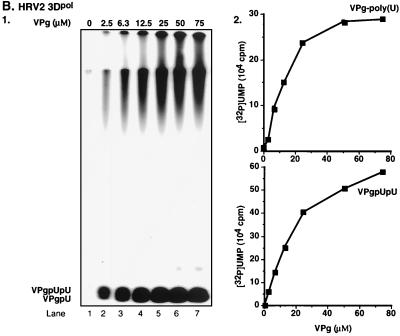

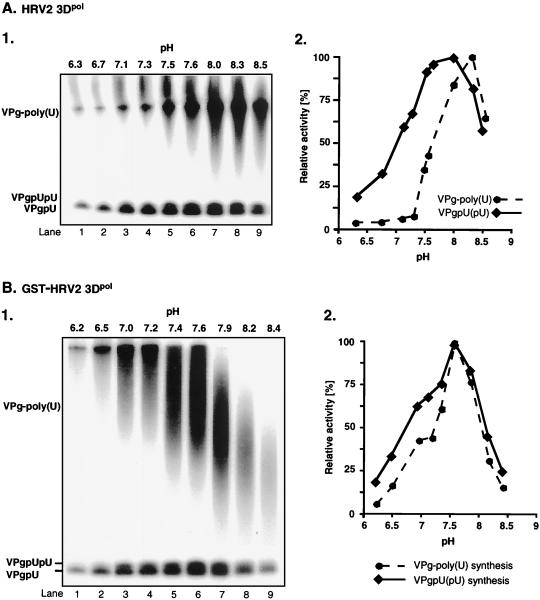

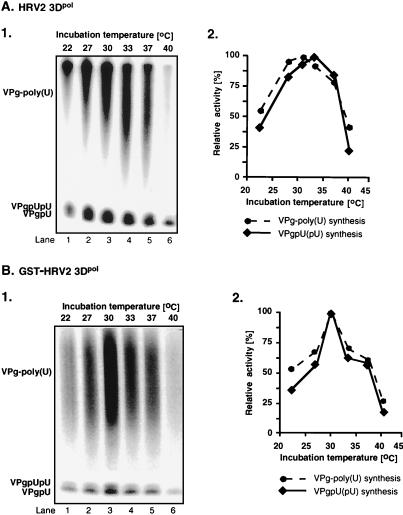

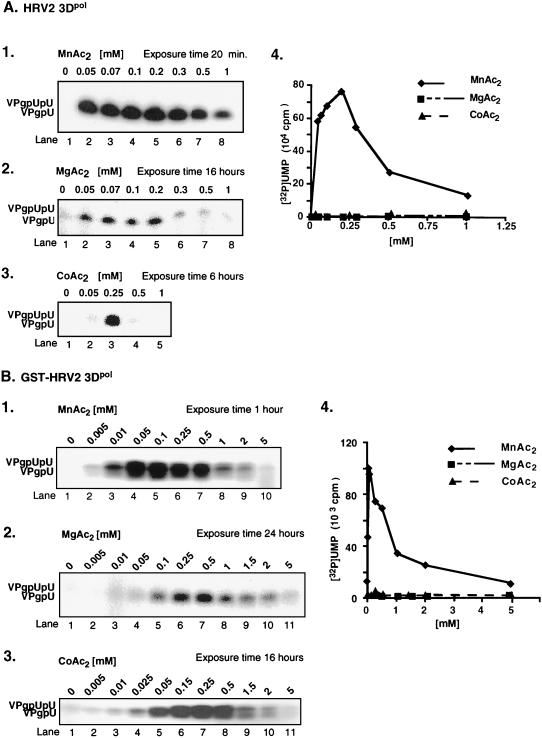

We have previously shown that under certain in vitro reaction conditions 3Dpol of PV1(M) is able to catalyze the covalent linkage of UMP to VPg, yielding VPgpU, a precursor that is elongated into VPgpUpU and then into VPg-poly(U) (41). The fact that the RNA polymerases of poliovirus and HRV2 are related (53) suggested the possibility that HRV2 3Dpol might also catalyze the same type of protein-priming reaction. As expected, HRV2 3Dpol is highly active in the synthesis of HRV2 VPgpU(pU) and VPg-poly(U) on a poly(A) template (Fig. 3B1 and 2). The in vitro reaction requires purified enzyme (Fig. 4, compare lanes 1 and 2), synthetic VPg (Fig. 4; compare lanes 1 and 3), UTP, and Mn2+ (Fig. 4; compare lanes 1 and 5). There appears to be no absolute requirement for poly(A) (Fig. 4; compare lanes 1 and 4), most likely since Mn2+ relaxes the specificity of the enzyme toward its template (5; A. V. Paul, J. Peters, and E. Wimmer, unpublished data). The yield of products is enhanced by the addition of a nonionic detergent (NP-40) (Fig. 4; compare lanes 1 and 6) but is not affected by the presence of dithiothreitol (DTT) (Fig. 4; compare lanes 1 and 7). The synthesis of VPg-poly(U) (Fig. 5B; compare lanes 1 and 7) is dependent on the presence of VPg, indicating that transcription of the poly(A) template is VPg primed. The small amount of polymeric product made in the absence of VPg (Fig. 4, lane 3, and Fig. 5B, lane 1) is most likely due to a terminal uridylyltransferase activity of the enzyme similar to that of poliovirus 3Dpol (44). Relatively high concentrations of 3Dpol (>3 μM [Fig. 5A]) and of VPg (50 μM [Fig. 5B]) are required for optimal synthesis of both the VPg-linked precursors and polymer. Under conditions of optimal VPg uridylylation (0.02 μM UTP) (Fig. 5C, lane 1), very little, if any, elongation of the precursors can be detected; however, polymers are synthesized when the UTP concentration is increased to >0.5 μM (Fig. 5C, lane 2). The optimum pH for the HRV2 3Dpol reaction is 7.5 to 8.0 (Fig. 6A), and the optimal incubation temperature is 33°C (Fig. 7A). The enzyme has a strong preference for Mn2+ over Mg2+ or Co2+ both in the VPg uridylylation reaction (Fig. 8A) and in the synthesis of VPg-poly(U) (data not shown). The optimal concentration of Mn2+ for both VPg uridylylation (Fig. 8A1) and VPg-poly(U) synthesis is 0.2 mM (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Requirements of HRV2 VPg uridylylation and VPg-poly(U) synthesis by HRV2 3Dpol. The standard assay for VPg-poly(U) synthesis was used, as described in Materials and Methods, except that various ingredients were omitted or added, as shown. Lane 1, complete reaction mixture; lane 2, no enzyme; lane 3, no VPg; lane 4, no poly(A); lane 5, no Mn2+; lane 6, complete mixture plus 0.1% NP-40; lane 7, complete mixture plus 5 mM DTT. (Panel 1) Autoradiography of the gel; (panel 2) quantified data.

FIG. 5.

Effects of varying HRV2 3Dpol, HRV2 VPg, and UTP concentrations on the synthesis of VPgpU(pU) and VPg-poly(U). The standard assay was used for VPg-poly(U) synthesis as described in Materials and Methods, except that the 3Dpol, VPg, or UTP concentration was varied as indicated. Effects of concentrations of 3Dpol (A), VPg (B), and UTP (C) are shown as autoradiographs (panels 1) and quantified data (panels 2).

FIG. 6.

Effects of pH on HRV2 VPgpU(pU) and VPg-poly(U) synthesis by HRV2 3Dpol (A) and GST-HRV2 3Dpol (B). Standard assays were used for VPg-poly(U) synthesis (see Materials and Methods) except that the pH of the reactions was varied as indicated. (Panels 1) Autoradiographs; (panels 2) quantified data, measured in counts per minute, are plotted as relative activity.

FIG. 7.

Effects of temperature on HRV2 VPgpU(pU) and VPg-poly(U) synthesis by HRV2 3Dpol (A) and GST-HRV2 3Dpol (B). Standard assays were used for VPg-poly(U) synthesis (see Materials and Methods) except that the incubation temperatures were varied as indicated. (Panels 1) Autoradiographs; (panels 2) quantified data, measured in counts per minute, are plotted as relative activity.

FIG. 8.

Effects of divalent metal concentrations on HRV2 VPgpU(pU) synthesis by HRV2 3Dpol and GST-HRV2 3Dpol. Uridylylation of VPg by HRV2 3Dpol (A) and by GST-HRV2 3Dpol (B) was measured by standard assays (see Materials and Methods) using either MnAc2 (panels 1), MgAc2 (panels 2), or CoAc2 (panels 3) at the indicated concentrations. (Panels 4) Quantified data. The length of exposure of the gel to Kodak film is given above each autoradiograph.

The activity of the GST-tagged enzyme in the synthesis of HRV2 VPgpU(pU) and VPg-poly(U) is comparable to that of HRV2 3Dpol (Fig. 3B). The optimal reaction conditions are also similar for the two versions of the enzyme. The optimal pH of GST-HRV2 3Dpol for the synthesis of both precursors and polymer is 7.6 (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, the size of the polymeric product decreases as the pH of the reaction is raised over pH 7.6 (Fig. 6B; compare lane 6 with lanes 7 to 9). The most favorable incubation temperature for the reactions is 30°C (Fig. 7B). Mn2+ is far superior to Mg2+ or Co2+ as a cofactor for GST-HRV2 3Dpol in both VPg uridylylation (Fig. 8B) and VPg-primed poly(U) synthesis (data not shown) under the conditions of the experiments. The optimal Mn2+ concentration for synthesis of the precursors is 0.05 mM (Fig. 8B), and that for synthesis of the polymer is 0.5 mM (data not shown).

Comparison of the RNA polymerase activities of HRV2 3Dpol and PV1(M) 3Dpol.

Using equal amounts (1 μM) of purified HRV2 3Dpol or PV1(M) 3Dpol (41) in the reaction mixtures, we have compared the synthetic activities of these two viral RNA polymerases. Both of these polypeptides were expressed in Escherichia coli with only an N-terminal methionine preceding the 3Dpol amino acid sequences. As shown on Fig. 3C, the two enzymes are about equally active in the elongation of a (dT)15 primer (panel 1; compare lanes 1 and 2). However, HRV2 3Dpol has two- to threefold-lower VPg-uridylylating activity than PV1(M) 3Dpol (panel 2; compare lanes 1 and 2) when each enzyme is tested with its cognate VPg as the substrate.

It has been reported previously that the uridylylated form of PV1(M) VPg, a 2-kDa peptide, migrates with an apparent molecular size of >7 kDa in SDS-PAGE gels (10, 34, 58). As can be seen from Fig. 3C, the apparent molecular size of HRV2 VPg is about the same. However, although HRV2 VPg is only 21 amino acids long, it migrates distinctly more slowly in the gel than the larger VPg of PV1(M) (22 amino acids) (Fig. 3C and 9C). The reason for the aberrant migration of the VPg peptides in these gels is not known.

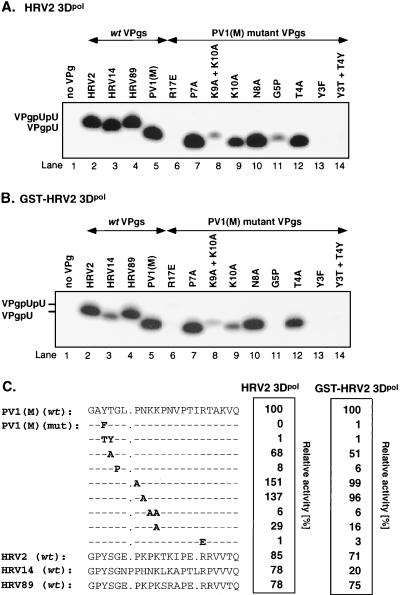

FIG. 9.

Comparison of wt and mutant (mut) PV1(M) VPgs and rhinovirus VPgs as substrates for uridylylation by HRV2 3Dpol and GST-HRV2 3Dpol. Standard assays for VPgpU(pU) synthesis were used (see Materials and Methods), except that HRV2 VPg was replaced by other VPgs, as indicated. (A) HRV2 3Dpol. (B) GST-HRV2 3Dpol. (C) Quantified data, measured in counts per minute, are shown as relative activity. Amino acid sequences of wt and mutant VPgs are given on the left. The mutant VPgs (with mutations shown in boldface) are derived from wt poliovirus VPg.

Comparison of wt and mutant VPg peptides as substrates for uridylylation by HRV2 3Dpol and GST-HRV2 3Dpol

Both the tagged- and untagged versions of HRV2 3Dpol are able to use PV1(M) VPg as a substrate in the in vitro reaction instead of HRV2 VPg (Fig. 9A and B; compare lanes 2 and 5). This observation has enabled us to assess the effects of amino acid substitutions in PV1(M) VPg, and presumably also in HRV2 VPg, on the in vitro activities of the peptides. Figure 9C shows a comparison of the wt and mutant PV1(M) VPg peptides as substrates for HRV2 3Dpol and GST-HRV2 3Dpol in the VPg uridylylation reaction. As expected, the tyrosine at position 3 in VPg, the attachment site to the viral RNA (2, 48), is essential for activity (Fig. 9A and B; compare lanes 5 and 13). The Y3T T4Y mutant VPg peptide is also totally inactive (Fig. 9A and B; compare lanes 5 and 14), confirming the importance of the tyrosine at the third position. Of the other mutant peptides, the R17E, K9A K10A, and G5P peptides had less than 10% of wt activity (Fig. 9A and B; compare lanes 5 with lanes 6, 8, and 11, respectively). Two mutations, P7A and N8A (Fig. 9A and B; compare lanes 5 with lanes 7 and 10, respectively), have no inhibitory effect, while others (K10A and T4A) give intermediate reductions in activity (Fig. 9A and B; compare lanes 5 with lanes 9 and 12, respectively). All of the mutant PV1(M) VPg peptides gave comparable results with the two different enzyme preparations. However, in contrast to HRV2 3Dpol (Fig. 9A; compare lane 5 with lane 3), the GST-tagged enzyme shows much-reduced activity with the VPg of HRV14 (56) compared with that of PV1(M) (Fig. 9B; compare lanes 5 and 3). The VPg of HRV89, a rhinovirus closely related to HRV2 (13), functions just as well as the VPg of HRV2 with both versions of the enzyme (Fig. 9A and B; compare lanes 2 and 4).

DISCUSSION

The RNA polymerase of poliovirus, a member of the genus Enterovirus, has been relatively well characterized. In contrast very little is known about the RNA polymerases of the other genera of Picornaviridae, such as HRVs. The synthetic activities of PV1(M) 3Dpol (15, 41) in vitro resemble those of the DNA polymerases of some double-stranded linear DNA viruses with genome-linked proteins such as phages φ29 and PRD1 and adenovirus (reviewed in reference 51). The DNA or RNA polymerases of all these viruses are unique because they are able to catalyze two different types of synthetic reactions. The first of these reactions is the elongation of an oligonucleotide primer on a DNA or RNA template, yielding a complementary strand. The second type of reaction consists of the covalent linkage of a nucleotide to the hydroxyl group of an amino acid in the viral terminal or preterminal protein (41, 51). The nucleotidylylated proteins then serve as primers for elongation of the new strands.

More than 15 years ago, HRV2 3Dpol was partially purified from virus-infected HeLa cells, and the enzyme was shown to be active in the elongation of oligonucleotide primers on both homopolymeric and heteropolymeric RNA templates (37). The experiments reported in this paper were undertaken with the aim of gaining more information about the synthetic activities of HRV2 3Dpol and the replication of HRVs. We expressed two different forms of the protein in E. coli, one as a GST fusion polypeptide and one with only an extra N-terminal methionine. The enzymes were purified, and their activities were first compared in vitro in the oligonucleotide elongation reaction with poly(A) as a template. Our results clearly show that these two preparations of HRV 3Dpol are about equally active in the elongation of a (dT)15 primer into (dT)15-poly(U). The same is true when one compares the elongation activity of HRV2 3Dpol with that of PV1(M) 3Dpol. This is not surprising in view of the fact that there is a 56% homology in the amino acid sequences of 3Dpol of these two viruses (53). However, the observation that GST-HRV2 3Dpol is highly active came as a big surprise (see below).

The picornaviral VPg is a peptide of about 20 to 25 amino acids whose single tyrosine residue provides the link to the 5′-terminal uridylylic acid of the viral genome (48, 50, 66). In this paper we provide evidence that HRV2 VPg can be uridylylated about equally well by both the GST-tagged and untagged forms of the polymerase of HRV2, yielding VPgpU and VPgpUpU. The optimal assay conditions that are used by the two enzyme preparations are similar. The uridylylation reaction requires only purified HRV2 3Dpol, synthetic HRV2 VPg, UTP, a poly(A) template, and Mn2+ as a cofactor. These precursors can then prime the transcription of poly(A) by 3Dpol to produce VPg-poly(U). The formation of polymeric products requires the presence of VPg, confirming the role of VPg as a primer for VPg-linked poly(U) synthesis. Although we have not directly shown that the bond between VPg and nucleotide in VPgpU is O4-(5′-uridylyl)tyrosine (2, 48), our experiments carried out with sequence variants of VPg fully support this proposal. As expected, no VPg-linked products were formed with a Y3F mutant VPg peptide, and this in vitro defect correlates with our genetic studies that showed this mutation to be lethal to HRV2 (17). The inability of the hydroxyl group of Y4 or T3 in a mutant T3Y4 VPg peptide to function as an acceptor of UMP demonstrates the very strict specificity of the enzyme both for the location and for the identity of the amino acid involved in the linkage. Surprisingly, relatively few other amino acids are essential (R17) or very important (G5, K9 with K10) for VPg's function in the in vitro reaction. This finding is further supported by the results of in vitro assays in which the VPg of HRV2 was replaced by that of PV1(M) or HRV14 (56). All of these viral VPgs were active as substrates for HRV2 3Dpol, although these peptides not only have different lengths but also contain only a few conserved residues (Fig. 9). These conserved amino acids (Y3, G5, K10, and R17) are identical with those shown to be required for VPg's function from studies of the mutant VPg peptides (see above). We have previously shown that these same amino acids in PV1(M) VPg are also required for the protein-priming reaction catalyzed by PV1(M) 3Dpol in vitro and for viral viability (41; A. V. Paul, J. Peters, and E. Wimmer, unpublished data). It is interesting that the VPg's of the two closely related viruses HRV2 and HRV89 (13) contain two negatively charged glutamate residues, which are absent in the VPgs of the other two viruses (Fig. 9). Apparently the absence of these amino acids from the VPgs of PV1(M) and HRV14 does not interfere with their ability to function as substrates for HRV2 3Dpol. The only noticeable difference between the substrate specificities of the two preparations of HRV2 3Dpol is the inability of GST-HRV2 3Dpol to efficiently uridylylate HRV14 VPg.

A partial structure of the poliovirus RNA polymerase as a “right hand” with “fingers,” “thumb,” and “palm” domains is already known from X-ray crystallographic studies by Hansen et al. (24). From the structural data it was predicted that the N-terminal polypeptide segment of 3Dpol might be derived from another polymerase molecule such that the N terminus of one contributes to the active-site cleft of the second molecule (24, 28). The importance of this segment was strongly supported by the finding that the N-terminal amino acids of 3Dpol are essential for its in vitro oligonucleotide elongation activity (24, 28, 44). In view of the fact that the enzymatic properties of HRV2 3Dpol are nearly identical to those of PV1(M) 3Dpol, it is remarkable that the bulky N-terminal GST tag on HRV2 3Dpol does not significantly interfere with its activity on a poly(A) template in either the oligonucleotide- or VPg-primed reactions. In contrast, a preparation of N-terminally fused GST-3Dpol of CAV21, an enterovirus closely related to PV1(M), is totally devoid of enzymatic activity in both of our assays, while the untagged form of the enzyme is fully active (E. Rieder and E. Wimmer, unpublished data).

It has been previously shown for PV1(M) 3Dpol that its RNA binding and polymerization activity is highly cooperative with respect to polymerase concentration, an observation suggesting that protein-protein interactions are important for its function (24, 39, 41). We have found that both VPg uridylylation and VPg-poly(U) synthesis by HRV2 3Dpol, just as by PV1(M) 3Dpol (41), are optimal at >1 μM 3Dpol, a concentration that has been shown to be similar to that required for oligomerization of the poliovirus enzyme (39). Whether HRV2 3Dpol must form dimers to interact with its template or primer (VPg or oligonucleotide) remains to be determined.

All known DNA and RNA polymerases require a divalent cation cofactor for optimal activity. Most in vitro polymerase assays that measure elongation use Mg2+, which is not only an effective activator but is also considered to be the metal most likely used in vivo. The activity of poliovirus 3Dpol in the oligonucleotide elongation assay is 10 times higher with Mn2+ than with Mg2+, and this has been attributed to a reduction in the Km value for 3Dpol binding to a primer and template (5). The protein-priming reactions catalyzed by DNA polymerases (8, 14, 45), the reverse transcriptase of hepatitis B virus (61), or PV1(M) 3Dpol (42) have an even more striking preference for Mn2+ as a metal cofactor. In this study we have confirmed this observation with both preparations of HRV2 3Dpol. In the presence of Mn2+, both VPg uridylylation and VPg-poly(U) synthesis on a poly(A) template by HRV2 3Dpol were increased about 100-fold over those in the presence of Mg2+. Whether or not the stimulatory activity of Mn2+ is due to an enhanced binding of the enzyme to the poly(A)-VPg complex is not yet known.

The facts that both minus and plus picornaviral RNA strands are VPg linked (38) and that the poly(A) tail of picornaviruses is genetically encoded (11) suggest that minus-strand synthesis commences with VPg-linked poly(U) synthesis. Therefore, one might expect that the uridylylation of VPg by 3Dpol on the poly(A) tail represents the very first step in that process. Our simple in vitro uridylylation assay was designed to represent exactly that type of reaction (41). Recently, however, we have made the surprising observation that the primary template in PV1(M) RNA for the synthesis of VPgpU(pU) in vitro is not the poly(A) tail but the cre(2C) hairpin (42), an RNA structure residing in the open reading frame of the poliovirus polyprotein (20). In our accompanying paper (17) we describe the VPg-uridylylating activity of HRV2 3Dpol using as a template its cognate cis-replicating element, which we have identified in the coding sequence of HRV2 2Apro.

The common cold probably represents the most frequent type of human illness against which no effective vaccine or chemotherapy has yet been developed. Although HRV infections do not cause severe disease, they can lead to secondary infections (9, 22) and can trigger acute asthma symptoms (18). The RNA polymerase of rhinoviruses is an ideal target for the development of antiviral drugs not only because it is essential for viral growth but also because it catalyzes a unique type of enzymatic reaction in the infected human cell.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. H. van Boom for the generous gift of synthetic VPg peptides, K. Kirkegaard for plasmid pT5T3D, T. Skern for plasmid pT7HRV2, T. Pfister and E. Rieder for helpful suggestions, and C. Cameron for critical reading of the manuscript.

K. Gerber was an exchange student from the graduate program of the University of Konstanz, Konstanz, Germany, at SUNY Stony Brook. This work was supported in part by NIH grant AI15122.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agol V I, Paul A V, Wimmer E. Paradoxes of the replication of picornaviral genomes. Virus Res. 1999;62:129–147. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(99)00037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambros V, Baltimore D. Protein is linked to the 5′ end of poliovirus RNA by a phosphodiester linkage to tyrosine. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:5263–5266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andino R, Rieckhof G E, Baltimore D. A functional ribonucleoprotein complex forms around the 5′ end of poliovirus RNA. Cell. 1990;63:369–380. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90170-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andino R, Rieckhof G E, Achacoso P L, Baltimore D. Poliovirus RNA synthesis utilizes a RNP complex formed around the 5′ end of viral RNA. EMBO J. 1993;12:3587–3598. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06032.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnold J J, Ghosh S K B, Cameron C E. Poliovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (3Dpol). Divalent cation modulation of primer, template, and nucleotide selection. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37060–37069. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arruda E, Pitkaranta A, Witek T J, Jr, Doyle C A, Hayden F G. Frequency and natural history of infections in adults during autumn. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2864–2868. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2864-2868.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borman A, Jackson R J. Initiation of translation of human rhinovirus RNA: mapping the internal ribosome entry site. Virology. 1992;188:685–696. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90523-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caldentey J, Blanco L, Savilahti H, Bamford D H, Salas M. In vitro replication of bacteriophage PRD1 DNA. Metal activation of protein-primed initiation and DNA elongation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:3971–3976. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.15.3971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cate T R, Roberts J S, Russ M A, Pierce J A. Effects of common colds on pulmonary function. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1973;108:858–865. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1973.108.4.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crawford N M, Baltimore D. Genome-linked protein VPg of poliovirus is present as free VPg and VPgpUpU in poliovirus-infected cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:7452–7455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.24.7452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorsch-Hasler K, Yogo Y, Wimmer E. Replication of picornaviruses. I. Evidence from in vitro RNA synthesis that poly(A) of the poliovirus genome is genetically coded. J Virol. 1975;16:1512–1527. doi: 10.1128/jvi.16.6.1512-1517.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duechler M, Skern T, Berger B, Sommergruber W, Kuechler E. Human rhinovirus serotype 2: in vitro synthesis of an infectious RNA. Virology. 1989;168:159–161. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90414-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duechler M, Skern T, Sommergruber W, Neubauer C, Gruendler P, Fogy I, Blaas D, Kuechler E. Evolutionary relationships within the human rhinovirus genus: comparison of serotypes 89, 2 and 14. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:2605–2609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.9.2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Esteban J A, Bernad A, Salas M, Blanco L. Metal activation of synthetic and degradative activities of φ29 DNA polymerase, a model enzyme for protein-primed DNA replication. Biochemistry. 1992;31:350–359. doi: 10.1021/bi00117a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flanegan J B, Baltimore D. Poliovirus-specific primer-dependent RNA polymerase able to copy poly(A) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:3677–3680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.9.3677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gamarnik A V, Andino R. Switch from translation to RNA replication in a positive-stranded RNA virus. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2293–2304. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.15.2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerber K, Wimmer E, Paul A V. Biochemical and genetic studies of the initiation of human rhinovirus 2 RNA replication: identification of a cis-replicating element in the coding sequence of 2Apro. J Virol. 2001;75:10969–10978. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.10979-10990.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gern J E, Busse W W. The effects of rhinovirus infections on allergic airway responses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:S40–S45. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/152.4_Pt_2.S40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gohara D W, Ha C S, Kumar S, Ghosh B, Arnold J J, Wisniewski T J, Cameron C E. Production of “authentic” poliovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (3Dpol) by ubiquitin-protease-mediated cleavage in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif. 1999;17:128–138. doi: 10.1006/prep.1999.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodfellow I, Chaudhry Y, Richardson A, Meredith J, Almond J W, Barclay W, Evans D J. Identification of a cis-acting replication element within the poliovirus coding region. J Virol. 2000;74:4590–4600. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.10.4590-4600.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greve J M, Davis G, Meyer A M, Forte C P, Yost S C, Marlor C W, Kamarck M E, McClelland A. The major human rhinovirus receptor is ICAM-1. Cell. 1989;56:839–847. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90688-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gwaltney J M., Jr Rhinovirus infection of the normal human airway. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:S36–S39. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/152.4_Pt_2.S36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamparian V V, Colonno R J, Cooney M K, Dick E C, Gwaltney J M, Jr, Hughes J H, Jordan W S, Jr, Kapikian A Z, Mogabgab W J, Monto A, Phillips C A, Rueckert R R, Schieble J H, Stott E J, Tyrrell D A J. A collaborative report: rhinoviruses—extension of the numbering system from 89 to 100. Virology. 1987;159:191–192. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansen J L, Long A M, Schultz S C. Structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of poliovirus. Structure. 1997;5:1109–1122. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00261-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris K S, Hellen C U T, Wimmer E. Proteolytic processing in the replication of picornaviruses. Semin Virol. 1990;1:323–333. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harris K S, Xiang W, Alexander L, Lane W S, Paul A V, Wimmer E. Interaction of the poliovirus polypeptide 3CDpro with the 5′ and 3′ termini of the poliovirus genome. Identification of viral and cellular cofactors needed for efficient binding. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27004–27014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hewat E A, Neumann E, Conway J F, Moser R, Ronacher B, Marlovits T C, Blaas D. The cellular receptor of human rhinovirus 2 binds around the 5-fold axis and not in the canyon: a structural view. EMBO J. 2000;19:6317–6325. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hobson S D, Rosenblum E S, Richards O C, Richmond K, Kirkegaard K, Schultz S C. Oligomeric structures of poliovirus polymerase are important for function. EMBO J. 2001;20:1153–1163. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.5.1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hofer F, Gruenberger M, Kowalski H, Machat H, Huettinger M, Kuchler E, Blaas D. Members of the low density lipoprotein receptor family mediate cell entry of a minor-group common cold virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1839–1842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jang S K, Krausslich H G, Nicklin M J H, Duke G M, Palmenberg A C, Wimmer E. A segment of the 5′ nontranslated region of encephalomyocarditis virus RNA directs internal entry of ribosomes during in vitro translation. J Virol. 1988;62:2636–2643. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.8.2636-2643.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koliais S I, Dimmock N J. Replication of rhinovirus RNA. J Gen Virol. 1973;20:1–15. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-20-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koliais S I, Dimmock N J. Rhinovirus RNA polymerase: products and kinetics of appearance in human diploid cells. J Virol. 1974;14:1035–1039. doi: 10.1128/jvi.14.5.1035-1039.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Korant B D, Lonberg-Holm K, Noble J, Stasny J T. Naturally occurring and artificially produced components of three rhinoviruses. Virology. 1972;48:71–86. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(72)90115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee Y F, Nomoto A, Detjen B M, Wimmer E. A protein covalently linked to poliovirus genome RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:59–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lobert P E, Escriou N, Ruelle J, Michiels T. A coding RNA sequence acts as a replication signal in cardioviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11560–11565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McKnight K L, Lemon S M. The rhinovirus type 14 genome contains an internally located RNA structure that is required for viral replication. RNA. 1998;4:1569–1584. doi: 10.1017/s1355838298981006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morrow C D, Lubinski J, Hocko J, Gibbons G F, Dasgupta A. Purification of a soluble template-dependent rhinovirus RNA polymerase and its dependence on a host cell protein for viral RNA synthesis. J Virol. 1985;53:266–272. doi: 10.1128/jvi.53.1.266-272.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nomoto A, Detjen B, Pozzatti R, Wimmer E. The location of the polio genome protein in viral RNAs and its implication for RNA synthesis. Nature. 1977;268:208–213. doi: 10.1038/268208a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pata J D, Schultz S C, Kirkegaard K. Functional oligomerization of poliovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. RNA. 1995;1:466–477. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paul A V, Cao X, Harris K S, Lama J, Wimmer E. Studies with poliovirus polymerase 3Dpol. Stimulation of poly(U) synthesis in vitro by purified poliovirus protein 3AB. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:29173–29181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paul A V, van Boom J H, Filippov D, Wimmer E. Protein-primed RNA synthesis by purified poliovirus RNA polymerase. Nature. 1998;393:280–284. doi: 10.1038/30529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paul A V, Rieder E, Kim D W, van Boom J H, Wimmer E. Identification of an RNA hairpin in poliovirus RNA that serves as the primary template in the in vitro uridylylation of VPg. J Virol. 2000;74:10359–10370. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.22.10359-10370.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pfister T, Wimmer E. Characterization of the nucleoside triphosphatase activity of poliovirus protein 2C reveals a mechanism by which guanidine inhibits poliovirus replication. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:6992–7001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.6992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Plotch S J, Palant O, Gluzman Y. Purification and properties of poliovirus RNA polymerase expressed in Escherichia coli. J Virol. 1989;63:216–225. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.1.216-225.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pronk R, van Driel W, van der Vliet P C. Replication of adenovirus DNA in vitro is ATP-independent. FEBS Lett. 1994;337:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80624-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rieder E, Paul A V, Kim D W, van Boom J H, Wimmer E. Genetic and biochemical studies of poliovirus cis-acting replication element cre in relation to VPg uridylylation. J Virol. 2000;74:10371–10380. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.22.10371-10380.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rivera V M, Welsh J D, Maizel J V. Comparative sequence analysis of the 5′ noncoding region of the enteroviruses and rhinoviruses. Virology. 1988;165:42–50. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90656-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rothberg P G, Harris T J, Nomoto A, Wimmer E. O4-(5′-uridylyl)tyrosine is the bond between the genome-linked protein and the RNA of poliovirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:4868–4872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.10.4868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rowlands D J. Rhinoviruses and cells: molecular aspects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:S31–S35. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/152.4_Pt_2.S31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rueckert R R. Picornaviridae. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 609–654. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salas M, Miller J T, Leis J, DePamphilis M L. Mechanisms for priming DNA synthesis. In: DePamphilis M L, editor. DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 131–176. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Skern T, Sommergruber W, Blaas D, Gruendler P, Fraundorfer F, Pieler C, Fogy I, Kuechler E. Human rhinovirus 2: complete nucleotide sequence and proteolytic processing signals in the capsid protein region. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:2111–2126. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.6.2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Skern T, Sommergruber W, Blaas D, Pieler C H, Kuechler E. Relationship of human rhinovirus strain 2 and poliovirus as indicated by comparison of the polymerase gene regions. Virology. 1984;136:125–132. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90253-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sommergruber W, Zorn M, Blaas D, Fessl F, Volkmann P, Mauer-Fogy I, Pallai P, Merluzzi V, Matteo M, Skern T, Kuechler E. Polypeptide 2A of human rhinovirus type 2: identification as a protease by mutational analysis. Virology. 1989;169:68–77. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stanway G, Brown F, Christian P D, Hovi T, Hyypia T, King A M Q, Knowles N J, Lemon S M, Minor P D, Pallansch M A, Palmenberg A C, Skern T. A taxonomy of the Picornaviridae: species designations and three new genera. 2000. Abstracts of the XIth Meeting of the European Study Group on Molecular Biology of Picornaviruses. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stanway G, Hughes P J, Mountford R C, Minor P D, Almond J W. The complete nucleotide sequence of a common cold virus: human rhinovirus 14. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:7859–7875. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.20.7859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Staunton D E, Merluzzi V J, Rothlein R, Barton R, Marlin S D, Springer T A. A cell adhesion molecule, ICAM-1, is the major surface receptor for rhinoviruses. Cell. 1989;56:849–853. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90689-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takegami T, Kuhn R J, Anderson C W, Wimmer E. Membrane-dependent uridylylation of the genome-linked protein VPg of poliovirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:7447–7451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.24.7447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Toyoda H, Yang C F, Takeda N, Nomoto A, Wimmer E. Analysis of RNA synthesis of type 1 poliovirus by using an in vitro molecular genetic approach. J Virol. 1987;61:2816–2822. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.9.2816-2822.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tyrrell D A J, Parsons R. Some virus isolations from common colds. III. Cytopathic effects in tissue cultures. Lancet. 1960;i:239–242. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(60)90168-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Urban M, McMillan D J, Canning G, Newell A, Brown E, Mills J S, Jupp R. In vitro activity of hepatitis B virus polymerase: requirement for distinct metal ions and the viral epsilon stem-loop. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:1121–1131. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-5-1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vartapetian A B, Koonin E V, Agol V I, Bogdanov A A. Encephalomyocarditis virus RNA synthesis in vitro is protein-primed. EMBO J. 1984;3:2593–2598. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Verdaguer N, Blaas D, Fita I. Structure of human rhinovirus serotype 2 (HRV 2) J Mol Biol. 2000;300:1179–1194. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wimmer E. Genome-linked proteins of viruses. Cell. 1982;28:199–201. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90335-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wimmer E, Hellen C U T, Cao X M. Genetics of poliovirus. Annu Rev Genet. 1993;27:353–436. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.27.120193.002033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xiang W, Paul A V, Wimmer E. RNA signals in entero- and rhinovirus genome replication. Semin Virol. 1997;8:256–273. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xiang W, Harris K S, Alexander L, Wimmer E. Interaction between the 5′-terminal cloverleaf and 3AB/3CDpro of poliovirus is essential for RNA replication. J Virol. 1995;69:3658–3667. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3658-3667.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yin F H, Knight E., Jr In vivo and in vitro synthesis of human rhinovirus type 2 ribonucleic acid. J Virol. 1972;10:93–98. doi: 10.1128/jvi.10.1.93-98.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]