Abstract

Aerosol and aqueous particles are ubiquitous in Earth’s atmosphere and play key roles in geochemical processes such as natural chemical cycles, cloud and fog formation, air pollution, visibility, climate forcing, etc. The surface tension of atmospheric particles can affect their size distribution, condensational growth, evaporation, and exchange of chemicals with the atmosphere, which, in turn, are important in the above-mentioned geochemical processes. However, because measuring this quantity is challenging, its role in atmospheric processes was dismissed for decades. Over the last 15 years, this field of research has seen some tremendous developments and is rapidly evolving. This review presents the state-of-the-art of this subject focusing on the experimental approaches. It also presents a unique inventory of experimental adsorption isotherms for over 130 mixtures of organic compounds in water of relevance for model development and validation. Potential future areas of research seeking to better determine the surface tension of atmospheric particles, better constrain laboratory investigations, or better understand the role of surface tension in various atmospheric processes, are discussed. We hope that this review appeals not only to atmospheric scientists but also to researchers from other fields, who could help identify new approaches and solutions to the current challenges.

1. Introduction

Surface tension is a key parameter that controls the shape and size of liquid particles present in another medium and the exchange of matter across their interface. It is thus expected to affect some important properties of the liquid particles present in Earth’s atmosphere and the processes in which they are involved, such as their formation and growth, size distribution, potentially their chemical evolution, and optical properties, all of which are important for the atmosphere and climate. However, measuring the surface tension of atmospheric particles is challenging. In fact, at the time of publication of this review, the surface tension of individual atmospheric particles has not yet been directly measured. Thus, for decades, the role of this parameter in atmospheric processes was neglected, and its value was systematically assumed to be equal to that of pure water. This has changed over the last 15 years with the emergence of various experimental approaches that are now giving some information about the surface tension of atmospheric aerosol samples and relevant laboratory mixtures or particles. This review presents an overview of this field of research, including a presentation of some basic concepts related to surface tension, emphasizing a molecular-level description (Section 1), a discussion of the atmospheric processes, in which surface tension is expected to play a role (Section 2), a presentation of the relevant measurement techniques (Section 3), and the current knowledge of the surface tension of atmospheric particles (Section 5). Section 4 presents a unique inventory of the experimental adsorption isotherms for about 130 water/organic mixtures, which can be used to develop relationships between molecular structure and surface tension in models or to validate other types of surface tension models for atmospheric particles. The last section of this review (Section 6) discusses the remaining challenges and identifies future areas of research such as future technical developments that would better constrain fundamental (laboratory) investigations, future investigations improving the understanding of atmospheric processes, and future areas of research addressing more specifically environmental issues. Previous reviews have discussed some aspects of the surface tension of atmospheric particles, but primarily focusing on specific processes, mostly cloud droplet formation,1,2 or on the compounds present at the surface of atmospheric aerosols and their properties.3,4 Other reviews have focused on the measurements techniques for surface tension.5,6 The sections overlapping with these previous articles have been kept as concise as possible in the present review to emphasize the complementary aspects and updates, and we refer to these articles for more complete information. Surface tension models themselves are beyond the scope of this review, and we refer to previous articles and reviews7−14 for more information on these theoretical approaches. We hope that, beyond atmospheric chemistry, this review raises the interest of chemists and chemical physicists from other fields to develop cross-disciplinary collaborations and possibly identify new solutions to the current challenges.

1.1. Definitions and Key Concepts

The following definitions are basic and can be found in textbooks. They are presented only briefly to clarify potential discrepancies between the concepts used in atmospheric chemistry and in other fields of chemistry and chemical physics. They are also presented to propose, whenever possible, a molecular description of the relevant processes and properties, most of which are inspired by the book of Rosen and Kunjappu.15

The historical definition of the surface tension, σ, by Gibbs16 is that of a thermodynamic and, thus, a macroscopic quantity: the energy per unit of surface area corresponding to the change dA to a surface area A, resulting from applying the element of work, dW:

| 1 |

where σ is usually expressed in mN m–1. Note that the surface tension is represented by the symbol “γ” in most fields of chemistry and chemical physics but by “σ” in the atmospheric chemical literature.

It has been recently demonstrated that the surface tension of solids is not related to their surface energy, thus that the Gibbs definition of surface tension does not apply to them.17 The present review thus discusses essentially the surface tension of liquid particles and mixtures. Surface tension effects can, however, been considered in solids such as the ice particles discussed in Section 2.4. Evidence has also been reported that solid particles such as soot coated with surface-active organic compounds, such as oleic acid or adipic acid, were more efficient in condensing water,18,19 which could potentially be attributed to surface tension effects.

Surface tension has a constant value (static surface tension) if the system of interest (bulk liquid or particle in contact with another phase) is equilibrated. However, with a rapidly changing system or interface, the surface tension will converge toward the new equilibrium value with some delay (dynamic surface tension), mostly due to diffusion effects.20,21 For atmospheric particles, such rapid changes in the interface occur, for instance, at the point of activation of forming water droplets or during the nucleation of new particles (see Section 2). The diffusion coefficients estimated for surfactants from atmospheric aerosols suggest that their diffusion time to the surface of a 1 μm-radius particle would be of the order of 1–100 s.22 Water droplet activation processes in the atmosphere are estimated to occur over the same time scale. Experimental measurements of the dynamic surface tension of aqueous solutions of amphiphilic surfactants (see Section 1.2.3 below) have shown that the largest differences between the static and dynamic surface tension occur at time scales shorter than 1 s.20,23 These dynamic surface tension effects are thus expected to have limited impacts on the atmospheric processes involving particles, as confirmed by recent measurements.24 The remainder of this review thus focuses on the static surface tension.

The International Union for Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC)25 defines a surfactant as “a substance which reduces the surface tension of the medium in which it is present”. The above definition implies that surfactants are at low molar fraction in the medium (otherwise they are part of the medium itself) so that this condition is explicit in the definition used in surfactant science: “a substance which, at low concentration, reduces the surface tension of the medium”.15 Since the term “surfactant” is the contraction of “surface-active agent”,15,25 both terms have the same meaning, as well as similar terms such as “surface-active compounds”. In the atmospheric chemical literature there is often confusion between surfactants and organic coatings, surface layers, or surface films.4 The latter differ from surfactants, as they form separate phases at the surface of the liquids without (necessarily) lowering their surface tension. Organic coatings, surface layers, and surface films will not be further discussed in this review, unless they clearly involve surface tension effects, and we refer to previous reviews3,4 for more information on such systems.

Since surfactants act on the surface tension at low molar fraction, they can be described, from a molecular point of view, as molecules present in small concentration in a solvent. In atmospheric chemistry the solvent of highest relevance is water but, as will be underlined in Section 2, surface tension can also play a role in particles made of other substances, such as concentrated sulfuric acid (as in newly nucleated particles) or organic liquids (as in Secondary Organic Aerosols). Surfactant molecules reduce the surface tension by replacing a small fraction of the solvent molecules at the surface and weakening the interactions between them.15 To achieve this, the surfactant needs to be not entirely soluble in the solvent, i.e., is dissolved in the solvent only up to a specific concentration, beyond which it builds a separate phase on top of it. Their presence in the solvent thus results in a distortion of the solvent structure and in an increase of the free energy of the mixture.15 However, the surfactant also needs to be at least partly soluble in the solvent to avoid being expelled into the adjacent phase (e.g., into the gas for a liquid/gas system), since the mixture will tend to minimize its energy by reducing the contact between the surfactant and the solvent and expelling the surfactant to the surface. Most organic compounds fulfill this partial solubility criterion in aqueous mixtures, thus acting as a surfactant with various degrees of efficiency (see Section 4). However, sugars, which are highly soluble in water, do not significantly reduce the surface tension of aqueous solutions (in fact, they tend to increase it). Similarly, organic compounds do not act as surfactants in organic solvents or particles in which they are fully soluble. At the opposite, the most efficient surfactants in aqueous solutions are amphiphilic compounds, which possess both a water-soluble (hydrophilic) moiety and nonwater-soluble (hydrophobic) molecular chains. The different types of surfactants potentially present in atmospheric aerosols have been discussed in previous reviews3,4 and the role of the molecular structure on the surfactant efficiency will be further discussed in Section 4.

1.1.1. Variation of the Surface Tension with Surfactant Concentration: Adsorption Isotherms

Building on the thermodynamic description of the surface tension (eq 1), the relationship between the surface concentration of surfactant, Γ, and the corresponding bulk concentration, C, is described with an adsorption isotherm, where the term “isotherm” indicates that it is established for a given temperature. However, for liquid/liquid and liquid/gas systems, the surfactant concentration at the interface can not be easily measured, and the Gibbs adsorption equation is rather expressed as a relationship between the surface tension of the mixture, σ, the surface concentration, Γi, and chemical potential, μi (thus, the bulk concentration) of the different components “i” present in the mixture:

| 2 |

For each component in the system

| 3 |

where ai = activity of compound i, R the gas constant, and T temperature. Thus, for system made of a solvent (for instance, water) with a1 ∼ 1 and a surfactant with a2 ∼ C, the bulk concentration, and Γ2 = Γm,

| 4 |

Eq 4 thus gives the variation of σ with the concentration of surfactant, C. Integrating eq 4 is not straightforward, and various assumptions can be used. An empirical equation that is often used to approximate the integration of eq 4 is the Szyszkowski equation:

| 5 |

where K is a constant depending on the surfactant, and σw is the surface tension of the pure solvent (here, assumed to be water). Numerous examples of adsorption isotherms are presented in Section 4 of this review, displaying a large range of shapes. Nonamphiphilic compounds accumulate at the surface of a mixture proportionally to their concentration in the bulk. This results in isotherms displaying two main regions: a first region at low bulk concentration, C, where σ ∼ σw, followed by a second region where σ decreases with C, until the concentration reaches the maximum solubility of the compound in water. Such isotherms are often described with a Szyszkowski-type equation (eq 5). By contrast, amphiphilic surfactants accumulate essentially at the surface (or interface) of a mixture so that their bulk concentration, C, is very small until the surface reaches saturation. When surface saturation is reached the surface tension is at its minimum value, σo. Beyond this concentration, the surfactant molecules do not dissolve in the bulk but produce micelles, which are highly organized phases and distinct from the bulk solution phase. The surface tension of the mixture does not further decrease with C but remains constant at σo. The value of C for which surface saturation is reached is thus called Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC). As a result, the adsorption isotherms for amphiphilic compounds display three distinct regions: a region at low C where σ = σw, an intermediate region where σ decreases sharply with C to reach σo, and a third region at large C where σ is constant and equal to σo (this last part is not predicted by the Szyszkowski equation, eq 5).

1.2. Surfactant Properties and External Parameters Affecting the Surface Tension

This section lists the various parameters affecting the surface tension of particles and mixtures, which includes both properties of the surfactants themselves (semisoluble surfactants, amphiphilic surfactants, etc.) and properties resulting from the medium in which they are present (mixing effects, geometric effects, etc.).

1.2.1. In Aqueous Media: Hydrogen Bond and Solvation

In aqueous solutions, the most important type of mixtures for atmospheric particles, the main molecular interactions between the solvent molecules (water) are hydrogen bonds. These bonds are responsible for the exceptionally large surface tension of water, σ (293 K) = 72.8 mN m–1. Although the strongest hydrogen bonds are those between water molecules, hydrogen bonding can also occur in other solvents containing hydrogen and electronegative atoms, such as oxygen, nitrogen, or halogen atoms: sugars, alcohols, organic acids, for instance. However, many organic compounds form only weak or no hydrogen bonds and, as solvents, have a surface tension markedly lower than that of water (typically, σ ≤ 30 mN m–1).26

As a consequence, semisoluble organic molecules present in aqueous mixtures, which do not form significant hydrogen bonds with water, weaken the hydrogen bonds between the water molecules and reduce the surface tension of the mixtures (see examples for many different organic molecules in Section 4). This effect is, however, modest and usually requires large bulk concentrations (>1 M) to substantially lower the surface tension (δσ > 10 mN m–1). It also decreases rapidly with dilution. Highly water-soluble organic molecules, such as sugars, which form substantial hydrogen bonds with water, do not act as surfactants as they do not fulfill the condition of partial solubility of surfactants. In addition, the formation of solvation shells (or solvation cages) around these compounds creates new structures for the water molecules, thus reinforcing the cohesion of the solvent and increasing the surface tension (see Section 4).

1.2.2. In Ion-Containing Media: Electrostatic Interactions

Ions, especially inorganic ones, are ubiquitous in the natural environment, including atmospheric aerosols. They strongly affect the interactions between the solvent molecules in which they are present and, thereby, the surface tension because they generate strong electrostatic forces. Depending on the solvent and on their charge and size, ions can either strengthen or weaken the cohesion between the solvent molecules and, thus, the surface tension. Inorganic salts such as NaCl and (NH4)2SO4 and, therefore, ions such as Na+, Cl–, SO42–, and NH4+ are ubiquitous and abundant in atmospheric particles. However, because they are fully soluble in aqueous mixtures, they do not act as a surfactant. However, the strong electrostatic fields that they produce reinforce the cohesions between the water molecules, resulting in the well-known effect of inorganic salts in increasing the surface tension of aqueous mixtures compared with pure water. The intensity of these effects depends on ions with their charge/radius ratio. Thus, among anions, SO42– has a larger effect than Cl– and, among cations, NH4+, has stronger effects than Na+.27,28 However, as electrostatic forces decrease rapidly with the distance between the charges, all of these effects decrease rapidly with dilution. Note, however, that the electrostatic interactions generated by dissolved inorganic ions also affect other components of solutions beside the solvent molecules and that their overall effects on the surface tension can be opposite to their effect in water alone (see Section 1.2.5 below).

1.2.3. Amphiphilic Interactions

As explained above, the most efficient surfactants for aqueous mixtures are amphiphilic molecules (also called amphipathic), carrying both a hydrophilic group (water-soluble) and one or more hydrophobic (=nonwater-soluble) groups (usually organic chains). In a water/air system, their hydrophobic groups ensure that their presence is essentially limited to the surface, the hydrophobic chains being in the air above the surface, where they can adopt a range of conformations (Figure 1). At the same time, their water-soluble moieties ensure their “anchoring” in the aqueous phase and prevent the molecules from being expelled from the aqueous phase and forming a separate phase above the surface. The physical process by which amphiphilic molecules lower the surface tension of aqueous solutions has been the subject of numerous experimental and theoretical studies (the latter mostly by molecular dynamics simulations).29,30 This effect is generally accepted to result from micromechanical “push-pull” effects of the hydrophobic chains perpendicular to the surface, as evidenced, for instance, by correlations between the surface tension and the chain length and rigidity of different amphiphilic surfactants.29 Depending on their water-hydrophilic group, amphiphilic compounds are classified as anionic, cationic, zwitterionic, or nonionic.15 These properties affect, for instance, their affinity toward negatively or positively charged surfaces.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the salting out and solvation of an amphiphilic surfactant (represented by the molecules with a long “tail”) by inorganic ions (red and green dots) and distribution of the different components between the surface and the bulk of an aqueous solution. From ref (60). Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society. Licensed under the CC-BY-NC-ND.

1.2.4. Macromolecules

Some organic molecules found in atmospheric aerosols contain more than 20 C atoms and have a molecular weight of several hundred Da or more. From the point of view of atmospheric chemistry, they can be considered as macromolecules, even though in chemistry and biochemistry this term is usually employed for much larger molecules. They include biopolymers (polysaccharides such as cellulose, chitosan, chitin, starch, etc.; polypeptides such as collagen and gelatin, etc.),31,32 polymers from biomass burning (some Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons, PAHs, and graphitic material, etc.),33−37 gels and hydrogels (extracellular polymeric substances),38−40 and polyphenolic compounds (lignin, humic, and fulvic substances).41−45 Their large molecular structure limits their solubility in water, thus allowing them to act as a surfactant. Some of those reported in atmospheric particles, and their commercial reference, have been shown to reduce the surface tension of aqueous solutions (see also Section 4, Table 5). They include fulvic acids (Suwannee River Fulvic Acid, SRFA41,44,46−48 and Nordic Aquatic Fulvic Acids, NAFAs41,49,50), commercial humic acid,48,51,52 aerosol-extracted Humic-Like substances (HULISs),41,42,44 and microbial or environmentally extracted Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPSs).53−55 The mode of action of these macromolecular compounds on the surface tension of aqueous mixtures is unclear. Aqueous solutions of macromolecules have been shown to undergo liquid–liquid phase separation and organize internally to lead to ultralow surface tension (down to 1 mN m–1).56,57 Such effects can thus not be excluded with humic substances, HULISs, and EPSs. However, humic and fulvic substances have also been shown to have some amphiphilic properties,58 and EPSs to contain non-negligible fractions of amphiphilic compounds.59 Thus, their surface tension properties could also partly result from these amphiphilic properties.

Table 5. List of the Binary Mixtures of Macromolecules in Water Included in This Inventory.

| n. | Type | Common name (IUPAC Name) | MW (g mol–1) | *σmin (mN m–1) | **ρ (g/cm3) | ***Atmos. ? | Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MA1 | macromolecules | SRFA (Suwannee river fulvic acid) | 57043 | 64.6,41 52.0,46 38.2,44 51.9,47 44.748 | 1.543 | PD,41,44,46,47 WP48 | |

| MA2 | macromolecules | NAFA (Nordic aquatic fulvic acid) | 4266359 | 63.4,41 55.2,49 52.550 | 1.5b | PD,49,50 NR41 | |

| MA3 | macromolecules | humic acid (commercial) | 226.14a | 48.1,51 52.5–65.8,48 58.7,52 57.5360 | 1.5b | WP,48,52 NR51,360 | |

| MA4 | macromolecules | HULIS (humic like substances) | ∼507 (410–610)44 | 49.6,42 ∼48.1 (41.8–53.0),41 41.4–42.944 | 1.643 | Y | NR,41 PD42,44 |

| MA5 | macromolecules | EPS (extracellular polymeric substances) | ∼158000 (62.4–213.1 kDa)361 | 52,53 66.6,54 59.6–61.555 | NR53−55 |

Data measured at 20–25 °C.

Data measured at 15–25 °C.

Reported in atmospheric aerosols; WP = Whilhelmy plate; PD = pending droplet, NR = Nouy ring.

Commercial Humic acid sodium salt C9H8Na2O4 68131-04-4 Thermo Scientific Chemicals.

Extrapolated from the surface tension of SRFA.43

1.2.5. Mixing Effects: Salting Out

In contrast with the increase in surface tension resulting from the presence of inorganic ions alone in water, adding inorganic ions to aqueous mixtures containing organic surfactants further reduces the surface tension. This effect has been observed both with nonamphiphilic, semisoluble organic compounds41,49,61−68 and with amphiphilic surfactants.60,68−74 It is known to result from the “salting out” of the organic molecules toward the surface, and is quantified by a Setschenow (or salting out) coefficient, Ks [M–1].15,75−77 In this process, the strong electrostatic interactions result in a strong reorganization of the water molecules as solvation shells (or “cages”) around the ions (Figure 1), thus lowering the solvation of the organic compounds and increasing the energy of the mixture.15 To minimize this energy, the organic molecules are “pushed” to the surface, resulting in larger surface concentration and thus lower surface tension than in the absence of salt. It also implies that surface saturation is reached with lower surfactant concentration and thus that the CMC is shifted to lower concentrations. As for the electrostatic interactions described above in Section 1.2.2, different anions and cations have different efficiencies in these processes, depending on their charge/radius ratio. Thus, SO42– and NH4+ have stronger salting out effects than Cl– and Na+,15 resulting in a more efficient surface tension reduction.

The salting out of organic surfactants by inorganic salts and additional reduction of the surface tension has been evidenced not only with bulk mixtures but also with submicrometer particles, both artificial ones49,67,78 and particles generated from surfactants extracted from atmospheric aerosols.64 In all cases, combining surface tension measurements with CN/CCN or CCN growth factor measurements (where “CN” stands for “Condensation Nuclei” and “CCN” for “Cloud Condensation Nuclei”) revealed that adding inorganic salts to the organic particles further decreased their critical supersaturation, which was unambiguously attributed to a decrease in the surface tension rather than to hygroscopic effects. In some cases, the critical supersaturation obtained with the mixed particles was even below that obtained with the salt alone,49,64 thus evidencing synergistic effects (see also definition in next paragraph) even in activated particles. This was shown, in particular, for particles made of organic fractions extracted from atmospheric (biomass burning) aerosols, displaying surface-active properties, with σ = 35–68 mN m–1. Adding (NH4)2SO4 to these particles reduced the critical supersaturation to below the value for pure (NH4)2SO4 particles.64 Salting out effects are thus important to take into account in atmospheric aerosols.

1.2.6. Mixing Effects: Nonideality, Synergism, and Antagonism

Atmospheric particles contain different types of organic compounds, which can affect the surface tension in different ways than simply adding their individual contributions. The simplest description of such mixtures is a two-component organic mixture including an organic acid that is abundant in atmospheric aerosols, such as oxalic, succinic acid, and an amphiphilic surfactant in a much smaller molar fraction. If these two components do not interact molecularly, i.e., have no direct or induced electrostatic attraction or repulsion between them (or at least not more than between each compound and the solvent) the mixture is defined as ideal.79 In that case, its overall properties, in particular the surface tension and CMC, is simply the combination of the contributions of each component, weighted by their relative molar fractions. However, if the organic components interact, the surface tension or CMC of the mixture can be lower or higher than expected for an ideal mixture, and the mixture is said to be nonideal. In some extreme cases, the overall surface tension can be even lower than both those for the pure components, and the mixture is said to be synergistic.15 Inversely, if the surface tension of the mixture is larger than those of the pure components, the mixture is antagonistic.15

Until now, mixing and ideality effects have mostly been studied for mixtures of different amphiphilic compounds. The molecular interactions between surfactants at the surface of a liquid and in the bulk during micelle formation are very different. At the surface, all the surfactant molecules have the same orientation, hydrophilic end in water and hydrophobic chains in the air above the surface. Thus, attraction or repulsion between surfactants can occur either between the hydrophilic ends at the surface or between the hydrophobic chains just above the surface. By contrast, the molecular interactions (attractions or repulsion) taking place in the bulk during micelle formation involve the entire surfactant molecules, which can take any orientation or conformation, thus leading to a wide variety of micelle structures. These different interactions at the surface and in the bulk explain why some mixtures of surfactants can be nonideal in surface tension but ideal in CMC, and vice versa.15,80 Examples of mixtures reported to be nonideal, and even synergistic or antagonistic, on the surface tension but ideal in CMC are mixtures of dodecyltrimethylammonium bromide (DTAB), and didodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB) in water.80,81 Recently, it has been shown that mixtures of amphiphilic compounds (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate or SDS, CetylTrimethyl Ammonium Chloride or CTAC, Triton X100/X114, Brij35) with oxalic and glutaric acid are nonideal in surface tension, even exhibiting some synergistic effects, but ideal in CMC.68 The nonideal effects on the surface tension were attributed to weakly repulsive effects (ionic or dipole–dipole) between the two types of molecules at the surface, thus reducing the surface tension. Synergistic effects on the CMC, such as observed in mixtures of different amphiphilic surfactants, are attributed to the formation of mixed micelles, i.e., including the two types of molecules.15,82 Antagonistic effects on the CMC are attributed to competition or steric hindrance between the two surfactants during the formation of the micelles.15,82

Nonideality, synergism, and antagonism are also likely to take place within the mixtures of amphiphilic surfactants present in atmospheric particles. However, to simplify the description of the surface tension of atmospheric aerosols, it might be easier to consider these amphiphilic mixtures as a single component, with net surface properties and isotherms resulting from all the interactions in the mixture.

1.2.7. Surface Curvature: Tolman Length

Because the surface tension results from the interactions between molecules at the surface of a liquid, it can be affected by the geometry of this surface. In small particles the curvature of the surface results in larger distances between the solvent molecules than in flat surfaces, thus weakening the interactions between the molecules83 and lowering the surface tension compared to flat surfaces. The impact of such geometry on the surface tension has been extensively studied since the 1950s84−86 and resulted in the definition of a characteristic radius, Tolman length, δ, for which the surface tension of a substance diverges significantly from that of a planar surface. For most substances the Tolman length is less than 1 nm:84,87,88 δ = 0.2189 and 0.53 nm87 for pure water (Figure 2), δ = 0 0.1 nm for deliquescent NaCl particles,86 and δ = 0.5–0.7 nm for organic compounds such as pentane and heptane.88 Most of these estimates are, however, obtained from theoretical models, as measuring this quantity experimentally is difficult and experimental values are scarce. In conclusion, particles made of pure substances or of homogeneous mixtures (i.e., having the same composition throughout the particle) have the same surface tension as flat surfaces of the same composition, down to radii as small as a few nanometers.

Figure 2.

Variation of the surface tension of water (here, “γ”) as a function of the particle radius predicted by different models (dashed line = fit with Tolman’s equation; continuous line: modified Tolman model accounting for the size-dependent surface energy; dots: simulation of the system using thermodynamic perturbation theory). Adapted with permission from ref (87). Copyright 2005 American Chemical Society.

It is interesting to note that, in small particles, the “Tolman effect” on the surface tension and the well-known Kelvin effect83 on the vapor pressure (i.e., a larger vapor pressure of a compound above a curved surface than above a flat surface) are two sides of the same molecular phenomenon: the weakening of the bonds between the molecules on the curved surface. In the Kelvin effect, the weakening of the bonds allows more molecules to leave the surface for the gas, thereby increasing the vapor pressure. This effect becomes significant for larger radii (several 10 of nm) than the “Tolman effect” (≤1 nm) because the molecules occupy more space in the gas than in the condensed phase (or at the surface), thereby resulting in a stronger effect on the vapor pressure than on the surface tension. While the Kelvin effect is the main constraint in homogeneous nucleation processes, and largely taken into account to describe the nucleation of new aerosol particles and water droplets in the atmosphere, the role of surface tension in these processes has been much less taken into account (see Section 2).

1.2.8. Surface/Volume Ratio: Bulk-to-Surface Partitioning

Because surfactants accumulate primarily at the surface of liquids rather than in the bulk, the existence of concentration gradients for these compounds inside small particles, referred to as bulk-to-surface partitioning, was proposed.90 The main implication is that, for a given ratio of total surfactant molecule number to sample volume (indicated as bulk concentration in adsorption isotherms), the surface tension of small particles would be larger than that of large-volume samples. As a discussion of surface tension models is beyond the scope of the present review, we refer to previous articles2−4,8,91,92 for more details on these theoretical discussions. Practically, bulk/surface partitioning implies that the surface tension values obtained from large-volume samples (>μL, corresponding to a particle radius of ∼1 mm), using classical techniques such as Wilhelmy plates, Du Noüy ring, or pendant drop (see Section 3) should underestimate the surface tension of microscopic particles of the same composition. As further discussed in Section 6, the occurrence and magnitude of these partitioning effects is still being debated, as very few experimental setups are able to investigate them and give somewhat contradictory results. For now, we underline in Section 3 that the measurements obtained from large-volume samples might need to be corrected for partitioning effects to be applied to micrometer or submicrometer particles.

1.2.9. Temperature

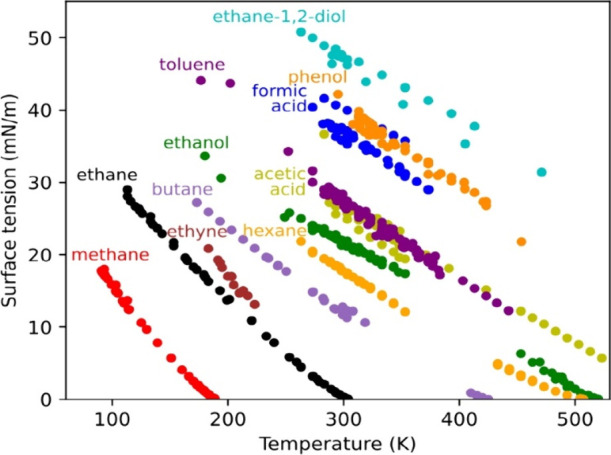

As the temperature increases the motion of molecules, it weakens the interactions at the surface of liquids. Thus, high temperature reduces the surface tension, while low temperature increases it. The effects are, however, relatively small over the range of atmospheric temperature. The surface tension of water decreases by about 10% between 273 and 323 K.93 And while the surface tension of pure organic compounds varies by as much as 40% over the same range94 (Figure 3) it varies much less when they are present in aqueous solutions (<5% over 290–330 K).95 No significant effects of temperature was observed either on the CMC of SDS mixtures over 298–313 K.96

Figure 3.

Variation of the surface tension with temperature for various organic compounds. Plotted from the surface tension data from ref (94). Reproduced with permission of SNCSC. Copyright 1997 Springer-Verlag.

2. The Role of Surface Tension in Atmospheric Processes

Surface tension affects a number of phenomena and properties in gas/liquid systems, from their shape and size (spherical shape of droplets, formation or dampening of surface waves, etc.) and other capillary phenomena97 to the more complex Marangoni effects,98 resulting in common observations such as tears of wine and coffee stains.99 It also affects the transfer of mass and heat across the gas/liquid interface.100−104 Surface tension is thus expected to control many important properties and processes in atmospheric particles and droplets (Figure 4, top). However, only a few of them have been studied so far, which are discussed below. We emphasize again that the present review discusses exclusively the processes directly related to surface tension and not those involving organic coatings and surface films, for which we refer to previous reviews.3,4 The studies discussed below are thus either those in which surface tension was measured and a reduction evidenced or those that involve amphiphilic surfactants. It is also important to keep in mind that, besides actual atmospheric processes, surface tension is likely to be important in most of the techniques used for generating artificial particles in the laboratory. These techniques and their limits are directly relevant to the understanding of atmospheric processes as generating artificial particles in a controlled way, i.e., with a controlled composition and size distribution, is essential for constraining fundamental investigations.

Figure 4.

A) Overview of the atmospheric processes in which surface tension can potentially play a role; B) Variation of the surface tension (σ) of nanodroplets containing different amounts of organic molecules (represented by Norg = number of organic molecules) during the condensation of water (Nw = water molecule number). From ref (122). Copyright 2023 American Chemical Society. Licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0; C) Evolution of the surface tension of sulfur particles during their nucleation, normalized by that of the corresponding flat surface, σ∞, and determined experimentally from their nucleation rate at different temperatures. Reproduced with permission from ref (125). Copyright 2016 Elsevier Ltd.

2.1. Cloud Droplet Formation

The atmospheric process in which the role of surface tension has been the most investigated is by far the formation of cloud droplets. By potentially affecting the size distribution of cloud droplets, surface tension could affect the cloud optical and radiative properties (Figure 4A) and also the cloud lifetime in the atmosphere. Because the Kelvin effect precludes the homogeneous nucleation of liquid water in Earth’s atmosphere (see Section 2.3 below), liquid cloud droplets are formed exclusively by the condensation of water on pre-existing particles, called Cloud Condensation Nuclei (CCN).105 The founding work of Köhler105,106 resulted in an equation describing the equilibrium between the water vapor concentration in the gas (or saturation ratio, S) and the particle radius, r, resulting from the water uptake:

| 6 |

where e is the water vapor pressure, es the saturation water vapor, and Mw and ρw are the molecular weight of water (18 g mol–1) and density of water (1 g cm–3), respectively. In eq 6 three parameters depend on the properties of the initial particle: its initial size (as an offset in the variable r), the water activity, aw, and the surface tension of the particle and forming droplet, σsol. The curves corresponding to eq 6 display a maximum, defining a critical radius, rcrit, and critical in saturation, Scrit, below which (S < Scrit) evaporation dominates and the droplets evaporate and above which (S > Scrit) condensation dominates and the droplets grow. Lowering the surface tension reduces Scrit thus enhances either evaporation or condensation, depending on the conditions of relative humidity (i.e., the value of S). Since these early works, these processes have been the subject of thousands of articles, some of the most representative being refs (1, 8, 9, 107, and 108) and the reviews (1−4), to which we refer for more information. For instance, ref (108) alone is cited by more than 2200 articles, giving a scale for the number of studies focusing on CCN activation over the last 20 years. A small fraction of these studies has addressed specifically the role of surface tension.8,9 For a long time, the approaches to investigate the CCN properties of atmospheric aerosols were almost exclusively the measurement of CCN growth factors with Hygroscopic Tandem Differential Mobility Analyzers, HTDMAs or CCN numbers Cloud Condensation Nuclei Counters, CCNCs.1,109 It is, however, difficult to isolate the effects specifically due to surface tension from other effects (hygroscopcity, etc.) with these instruments. In laboratory, these effects have been distinguished, for instance, by exposing (NH4)2SO4 particles to organic vapors (methylglyoxal and acetaldehyde) and observing a reduction of the critical supersaturation based on CN/CCN measurements.110 However, only a few HTDMA-based observations of surface tension effects have been reported for atmospheric particles: measurements of CCN growth factors in the tropical Atlantic Ocean111 and Central Germany112 indicated that these particles might have a surface tension significantly lower than pure water (50–60 mN m–1).111,112 Recent HTDMA measurements of CCN growth factors in Southern China reported similar observations for newly formed particles (σ ∼ 60 mN m–1).113 To go around the lack of sensitivity of HTDMA and CCNC measurements to surface tension and the absence of direct surface tension measurements for atmospheric particles, different approaches have been developed over the last 15 years to estimate this parameter and its importance in cloud droplet formation. One approach consists of using in models the surface tension properties of surfactants extracted from atmospheric aerosols to estimate the surface tension of atmospheric particles and their contribution to cloud droplet formation. However, such multiple-step approaches result in large uncertainties. More global (or top-down) investigations of the role of surface tension in cloud droplet formation would be advantageous. To our knowledge, at the time of publication of this review, no direct evidence for the role of surface tension on cloud formation or properties has been reported yet. However, some potential future directions of investigation are proposed below in Section 2.5.

2.2. Nucleation of New Particles

Besides aqueous droplets, surface tension is expected to affect the nucleation of all types of materials. This parameter would affect both the condensation processes and the evaporation of the forming nanoparticles (the Kelvin effect). In the atmosphere, this applies to the homogeneous nucleation of sulfuric acid, amines and other organic compounds,114−119 processes reported to be potentially reversible in some observations.120 However, while surface tension in an explicit parameter in nucleation theory,115,117 its value is generally assumed to be constant and its importance for the formation of atmospheric particles has, to our knowledge, not been investigated experimentally. An experimental study of the nucleation of sub-3 nm sulfuric acid particles has shown that the classical condensation model fails to predict the observed growth, as well as its dependence on temperature and RH,121 indicating the involvement of other parameters, which could include the surface tension. Molecular dynamics simulations of the nucleation of organic/water particles,122 have also reported strong deviations of the surface tension from the continuous behavior assumed in usual theories, with surface tension of ∼20 to 40 mN m–1 predicted for sub-4 nm particles (Figure 4, bottom), thus underlining the importance of investigating this parameter experimentally.

To our knowledge, experimental investigations of the role of surface tension in nucleation processes were performed only in fields other than atmospheric science. They further confirm the importance of the surface tension in these processes. For instance, a study measuring the surface tension as a function of the surface curvature for nucleating colloidal particles of polyn-isopropylacrylamide (PNIPAM) in solutions of 3-methylpyridine (3MP) and heavy water showed that a reduction of the surface tension by 20% resulted in an increase of the nucleation rate by 3 orders of magnitude.123 In other studies, the surface tension of nucleating metal zinc and silver particles124 and of sulfur nanoparticles125 (Figure 4, bottom) from the gas phase and its variation with the particle radius (down to less than 1 nm) were determined from their nucleation rates. Given the strong impact of surface tension on nucleation rates, it could be interesting to study this parameter in atmospherically relevant nucleation processes. Some potential directions of investigation are proposed in Section 2.5.

2.3. Uptake of Gases and Heterogeneous Reactions

In addition to condensation/evaporation processes, surface tension is expected to affect the exchange of other compounds across the gas/liquid interface. For instance, adding relatively small surfactants (up to 10 C atoms) to solutions was shown to enhance the uptake of ammonia, NH3,100,104 and carbon dioxide, CO2.103 Inversely, adding long-chain surfactants (C > 10) to aqueous solutions was shown to oppose the uptake of NH3100 and O2,101 with a clear correlation between the surfactant chain length and mass-transfer reduction in the H2O/NH3 system.100 Thus, the surface tension of atmospheric particles is expected to affect the uptake and release of gases, which can, in turn, affect the removal of some gases from the atmosphere, the chemical composition of the particles, and possibly some reactions at the particle surface (heterogeneous reactions).

However, the effect of surface tension on the uptake of gases by atmospheric particles has been little studied. Most focus has been on the effects of organic coatings and surface films on the uptake of gases,3,4 which oppose the exchanges with the gas, but are not related to surface tension. A few exceptions could have been the studies involving amphiphilic surfactants such as Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS). However, they focused on the oxidation processes at the air/water interface, in particular on the reaction of SDS with an OH radical126,127 and its impact on the reaction rate of an organic compound (Tricarballylic acid, TCA) dissolved in the bulk.127 However, surface tension was not measured in these studies, and its potential effects on the gas uptake and surface reactivity were not investigated. Thus, to the best of our knowledge, the effects of surface tension on the uptake of gases by atmospheric particles and their heterogeneous chemistry still remain to be studied.

2.4. Ice Nucleation

Although, as indicated in Section 1, the Gibbs definition of surface tension might not apply to solids, a number of studies have addressed the potential role of surfactants on the nucleation of ice crystals in the atmosphere (see, for instance, the reviews3,4). This topic is thus briefly discussed here. In Earth’s atmosphere, the formation of ice crystals can occur either by homogeneous nucleation from liquid water at a temperature near or below −38 °C (235 K)105 or by heterogeneous nucleation on pre-existing solid particles, referred to as Ice Nucleating Particles (INPs) at much higher temperature, almost up to 0 °C. These heterogeneous processes can occur in different modes, referred to as immersion freezing, condensation freezing, and contact freezing. In immersion freezing the INP acts as CCN and the resulting water droplet freezes, in condensation freezing water vapor condenses on the INP to form first a liquid droplet, then freezes, and in contact freezing the INP collides with a water droplet, then freezes.128 While immersion freezing involves initially the same processes as described in Section 2.1 for liquid droplets formation, homogeneous nucleation and condensation freezing can be described by classical nucleation theory,129 in which surface tension is an explicit parameter. However, the key surface tension in these processes, and possibly also contact freezing, is that between the ice-nucleating surface (liquid water or INP) and the ice phase.105 Substances such as mineral dust, inorganic salts, soot,130 or biological particles,131 have been reported to act as INPs, i.e., to increase the threshold temperature at which ice crystals are formed. In particular, experimental studies such as refs (132−139) have even evidenced the INP efficiency of monolayers of amphiphilic organic compounds. However, these substances do not affect the interfacial tension between the ice-nucleating surface and the ice phase. Their INP efficiency is due to their highly ordered molecular structures, providing a 2D-lattice pattern favoring the nucleation of hexagonal ice. To our knowledge, no experimental data are available on the interfacial tension between the ice-nucleating surface and the ice phase, as this parameter is very challenging to measure. Such experimental data would be interesting to have. However, unlike for liquid surfaces, this interfacial tension is not expected to vary significantly during the ice nucleation processes in the atmosphere or to be affected by the presence of surfactants and, thus, to be a limiting factor in the nucleation processes.

2.5. Perspectives on the Investigations of Surface Tension in Various Atmospheric Processes

As discussed in this section, the role of surface tension in atmospheric processes has mostly been investigated for cloud droplet formation. However, even in this case, no clear evidence of a role of surface tension on cloud formation has been established, and there is a need to develop new directions of investigation to overcome the limits of the current techniques. An interesting approach could be, for instance, to develop methods to achieve the selective sampling of CCN and interstitial aerosols or of cloudwater and interstitial aerosols. Such a selection could perhaps be performed based on growth factors at the output of a HTDMA, collecting separately the particles with GF = 1 (interstitial particles) and those with GF > 1 (CCN). Provided that enough material can be accumulated, the surface tension could be measured for both populations and compared and indicate whether the CCN or cloudwater contain more surfactants than the interstitial aerosols. Even more global investigation of a role of surface tension on cloud formation or properties could consist, for instance, in evidencing correlations or causality relationships140 between long-term series of cloud properties (frequency, lifetime, droplet size distribution, etc.) at a given site and corresponding series for the surface tension of the aerosols or CCN upwind from the site.

As discussed in Section 2.2, although evidenced in other fields, the role of surface tension in the nucleation of materials other than water remains entirely to be studied for atmospheric particles. This could be investigated in the laboratory. For instance, for organic particles by comparing the nucleation rates of different organic materials with different surface tensions. For more complex mixtures, such as sulfuric acid/organic, the surface tension could be estimated from the vaporization enthalpies.141,142

The role of surface tension in the uptake and release of gases, while also evidenced in other fields of research, remains also largely to be investigated from the point of view of atmospheric particles. This could also be done in the laboratory, where the role of common organic aerosol components (for instance, organic acids) or amphiphilic surfactants in the uptake and release of gases could be studied, the same way as many other uptake processes have been studied in the atmospheric literature.

As in the case of cloud droplet formation, a main reason for not exploring the role of surface tension in these other processes was, for a long time, the lack of data on the surface tension of atmospheric particles and widespread belief that it was identical with that of pure water. However, the progress made over the last 15 years shows that this is not the case, and the new approaches for measuring the surface tension now allow us to explore its role in these other processes.

3. Surface Tension Measurement Techniques for Atmospherically Relevant Mixtures and Particles

Some of the most spectacular developments in the investigation of the surface tension of atmospheric particles and relevant mixtures over the last 10 years were those of measurement techniques. While surface tension had mostly been studied with techniques requiring large volume samples in other fields of chemistry and chemical physics, within a decade the atmospheric community has developed approaches to determine the surface tension of μL-atmospheric samples and individual pL (pico-L) particles. This section presents the techniques currently available to determine the surface tension of atmospherically relevant mixtures and particles. This includes the classical techniques requiring large volume samples (≥μL), which are still largely used for the investigation of model mixtures in the laboratory, those requiring mL- to μL-volume samples, that have been applied to atmospheric fogwater, cloudwater and aerosol sample extracts (see Section 5), and the techniques applicable to micrometer or submicrometer individual particles. The main reason for developing techniques applicable to individual micrometer-sized particles is to eventually measure the surface tension of individual atmospheric particles. In addition, as discussed in Section 1.2.8, such techniques are the only ones allowing to investigate bulk-to-surface partitioning and other effects specific to microscopic particles. It is thus important to keep in mind that the results of the “bulk techniques” presented below (and the isotherms presented in Section 4) might require some bulk-to-surface partitioning corrections to be applicable to microscopic particles.

Note that as underlined in Section 1, the techniques presented in this section measure the static surface tension, except perhaps for the optical traps and optical tweezers techniques described in Section 3.2.1. Many of the techniques described below have already been presented elsewhere,5 in particular those for individual particles,6,143−146 and we refer to these previous articles for more detail. The descriptions below are kept short to focus on the main features, advantages, or limitations regarding atmospheric samples. Each of the techniques described below is assigned an abbreviation, referring to the literature data presented in Section 4 and in Tables 1−5.

Table 1. List of the Binary Mixtures of Organic Acids in Water Included in This Inventory.

| n. | Common name (IUPAC Name) | Brut formula | CAS n. | MW (g mol–1) | *σpur (mN m–1) | **ρ (g cm–3)248 | ***Atmos. ? | Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC1 | formic acid (methanoic acid) | CH2O2 | 64-18-6 | 46.03 | 37.2,15 38.17,249 37.03,250 35.81–40.7194 | 1.220 | Y192,194,196 | DVT,249 WP250 |

| AC2 | acetic acid (ethanoic acid) | C2H4O2 | 64-19-7 | 60.05 | 29.4,10 27.08,249 27.12,250 25.61–27.894 | 1.045 | Y196 | DVT,249 WP250 |

| AC3 | propionic acid (propanoic acid) | C3H6O2 | 79-09-4 | 74.08 | 26.17,250 26.2,20,248 26.15,249 25.13–2794 | 0.988 | DVT,249 WP250 | |

| AC4 | butyric acid (butanoic acid) | C4H8O2 | 107-92-6 | 88.11 | 26.05,248 26.19,249 26.21,251 25.31–26.8394 | 0.953 | DVT,249,251 CR151 | |

| AC5 | oxalic acid (ethanedioic acid) | C2H2O4 | 144-62-7 | 90.03 | 1.900 | Y192−198 | PD,47,68,252,253 WP48,149,150,254 | |

| AC6 | methanesulfonic acid | CH4O3S | 75-75-2 | 96.11 | 53255 | 1.481 | Y196 | WP,255,256 NR148 |

| AC7 | valeric acid (pentanoic acid) | C5H10O2 | 109-52-4 | 102.13 | 26.7,15 26.63251 | 0.934 | DVT,251 NR257 | |

| AC8 | malonic acid (propanedioic acid) | C3H4O4 | 141-82-2 | 104.06 | 1.63a | Y192,196,197 | PD,47,252,253 WP,149,150 AFM183 | |

| AC9 | β-hydroxybutyric acid (3-hydroxybutanoic acid) | C4H8O3 | 300-85-6 | 104.11 | 1.13b | WP52 | ||

| AC10 | maleic acid ((2Z)-but-2-enedioic acid) | C4H4O4 | 110-16-7 | 116.07 | 1.590 | Y192,197,198 | PD,47,253 WP150,254 | |

| AC11 | caproic acid (hexanoic acid) | C6H12O2 | 142-62-1 | 116.16 | 27.51,251 27.2–28.194 | 0.921 | DVT,251 NR,257 AFM,186 NP186 CR62 | |

| AC12 | succinic acid (butanedioic acid) | C4H6O4 | 110-15-6 | 118.10 | 1.572 | Y192−199 | PD,46,47,252,253,258,259 WP,48,149,150,254 CR65 | |

| AC13 | benzoic acid (benzenecarboxylic acid) | C7H6O2 | 65-85-0 | 122.12 | 1.266 | DW260 | ||

| AC14 | cyclohexylmethanoic aci (cyclohexanecarboxylic acid) | C7H12O2 | 98-89-5 | 128.17 | 1.033 | DVT261 | ||

| AC15 | enanthic acid (heptanoic acid) | C7H14O2 | 111-14-8 | 130.19 | 27.8,15 30.07,257 28.14–28.794 | 0.912 | NR,257 WP262 | |

| AC16 | glutaric acid (pentanedioic acid) | C5H8O4 | 110-94-1 | 132.11 | 1.429 | Y193,194,196−198 | PD,47,68,252,253,259 WP,48,149,174,263 AFM,183 OT174,264 | |

| AC17 | malic acid (2-hydroxybutanedioic acid) | C4H6O5 | 6915-15-7 | 134.09 | 1.601 | Y192,194,197−199 | PD,47,253 WP150 | |

| AC18 | p-toluic acid (4-methylbenzoic acid) | C8H8O2 | 99-94-5 | 136.15 | 1.06c | DW260 | ||

| AC19 | 3-hydroxybenzoic acid | C7H6O3 | 99-06-9 | 138.12 | 71.352 | 1.485 | WP52 | |

| AC20 | cyclohexylethanoic acid | C8H14O2 | 5292-21-7 | 142.20 | 1.042 | DVT261 | ||

| AC21 | caprylic acid (octanoic acid) | C8H16O2 | 124-07-2 | 144.21 | 28.2–29.294 | 0.907 | NR257 | |

| AC22 | adipic acid (hexanedioic acid) | C6H10O4 | 124-04-9 | 146.14 | 1.360 | Y193,197,198 | PD,47,252,253 WP48,265 | |

| AC23 | 4-ethylbenzoic acid | C9H10O2 | 619-64-7 | 150.17 | 1.1p | DW260 | ||

| AC24 | cyclohexylpropanoic acid | C9H16O2 | 701-97-3 | 156.22 | 0.912 | DVT261 | ||

| AC25 | pelargonic acid (nonanoic acid) | C9H18O2 | 112-05-0 | 158.24 | 26.2–29.794 | 0.905 | NR,257 WP,266 PB267 | |

| AC26 | 4-propylbenzoic acid | C10H12O2 | 2438-05-03 | 164.20 | 1.1p | DW260 | ||

| AC27 | phtalic acid (benzene-1,2-dicarboxylic acid) | C8H6O4 | 88-99-3 | 166.13 | 1.59d | Y192,197−199 | WP48 | |

| AC28 | cyclohexylbutanoic acid | C10H18O2 | 4441-63-8 | 170.25 | 1.0p | DVT261 | ||

| AC29 | capric acid (decanoic acid) | C10H20O2 | 334-48-5 | 172.27 | 0.9p | NR,257 PB268 | ||

| AC30 | 4-butylbenzoic acid | C11H14O2 | 20651-71-2 | 178.23 | 1.1p | DW260 | ||

| AC31 | pinonic acid (3-acetyl-2,2-dimethylcyclobutylacetic acid) | C10H16O3 | 473-72-3 | 184.23 | 1.1p | Y193 | DVT,61 PD,47,253 WP,52,150 NR63 | |

| AC32 | undecylic acid (undecanoic acid) | C11H22O2 | 112-37-8 | 186.29 | 0.891 | NR257 | ||

| AC33 | azealic acid (nonanedioic acid) | C9H16O4 | 123-99-9 | 188.22 | 1.225 | Y193,197−199 | WP48,52 | |

| AC34 | citric acid (2-hydroxypropane-1,2,3-tricarboxylic acid) | C6H8O7 | 77-92-9 | 192.12 | 1.665 | PD,47,253,269 WP254,263 | ||

| AC35 | 4-pentylbenzoic acid | C12H16O2 | 26311-45-5 | 192.25 | 1.0p | DW260 | ||

| AC36 | lauric acid (dodecanoic acid) | C12H24O | 143-07-7 | 200.32 | 0.9p | WP270 | ||

| AC37 | trimesic acid (benzene-1,3,5-tricarboxylic acid) | C9H6O6 | 554-95-0 | 210.14 | 1.7p | WP48 | ||

| AC38 | oleic acid ((9Z)-octadec-9-enoic acid) | C18H34O2 | 112-80-1 | 282.47 | 32.79,271 31.8,272 30.99–32.894 | 0.894 | NR,273,274 PD,275 WP276 | |

| AC39 | ricinoleic acid ((9Z,12R)-12-hydroxyoctadec-9-enoic acid) | C18H34O3 | 141-22-0 | 298.46 | 0.945 | NR277 | ||

| AC40 | arachidonic acid ((5Z,8Z,11Z,14Z)-icosa-5,8,11,14-tetraenoic acid) | C20H32O2 | 506-32-1 | 304.5 | 0.908 | NR278 | ||

| AC41 | 7,10-dihydroxy-8(E)-octadecenoic acid | C18H34O4 | 131021-99-3 | 314.5 | 1.0p | NR277 |

Data measured at 20–25 °C.

Data measured at 15–25 °C.

Reported in atmospheric aerosols; WP = Whilhelmy plate; PD = pending droplet (shape of a droplet); DVT = drop volume tensiometry, NR = Nouy ring; CR = capillary rise; DW = drop weight; PB = pending Bubble; AFM = atomic force microscopy, NP: Du Noüy-Padday method, OT = optical tweezer.

ThermoFischer Scientific, Safety Data sheet according to Regulation UK SI 2019/758 and UK SI 2020/1577, Malonic acid, A11526, 2024 Revision 6.

Sigma-Aldrich, Safety Data Sheet according to Regulation (EC) No. 1907/2006, 3-Hydroxybutyric acid, 166898, 2023 Version 6.4.

Sigma-Aldrich, Safety Data Sheet according to Regulation (EC) No. 1907/2006, 4-Methylbenzoic acid for synthesis, 2023 Version 6.12.

Sigma-Aldrich, Safety Data Sheet, 4-Phthalic acid for synthesis, 2023 Version 9.0.

Predicted data from ChemSpider (RSC) generated using the ACD/Laboratories Percepta Platform - PhysChem Module version 14.00.

3.1. Techniques Applicable to Bulk Samples (>1 μL)

3.1.1. Force Measurement (WP, NR, DNP)

Some of the oldest and most common techniques to measure the surface tension of liquids, which are also those requiring the largest sample volume (>mL), are based on dropping a metal object, a plate (Wilhelmy Plate, WP), a ring (Du Noüy Ring, NR) (Figure 5), or a thin rod (Du Noüy-Padday, DNP) in the liquid of interest and measuring the force, F, necessary to pull it up, usually with an electrobalance:

| 7 |

where A is the surface area of the object in contact with the liquid. Thus, these techniques depend on the surface area of the object in contact with liquid A, and might require some correction factors to account for limited wettability. The uncertainties on the measurements with these techniques have been reported to be of the order of 0.1 mN m–1.147 However, the required sample volumes are at least in the mL range. These techniques have been used to measure the surface tension of a large number of binary aqueous mixtures of reference compounds of atmospheric relevance (organic acids, etc.) in the laboratory (see Section 4 and refs (48, 148−150)).

Figure 5.

Schematics of various experimental techniques used to determine the surface tension. Adapted with permission from ref (169). Crown copyright 2015 Elsevier Ltd.

3.1.2. Gravitational Equilibrium (CR, PD, PB, DVT, DW, DN, BP)

A vast class of techniques for the measurement of the surface tension of liquids is based on equilibrating the surface tension forces, F, applied to a sample with gravity, i.e., with the sample weight. They include the Capillary Rise (CR), Pendant Droplet (PD, also referred to as “Pending droplet” or “Hanging droplet”), Pendant Bubble (PB), Drop Volume Tensiometry (DVT), Drop Weight (DW), Drop Number (DN), and Bubble Pressure (BP) techniques. In these techniques, the surface tension is determined from the Young–Laplace equation, expressing the capillary pressure, ΔP, across an interface of area A, thus corresponding to a force, F, resulting from the surface tension, σ:

| 8 |

where R1 and R2 are the two main radii of curvature, in the case of a nonspherical surface. Equilibrating the force F with the sample weight thus gives

| 9 |

where m is the mass of the sample and g the gravitational constant.

There are many variations on this approach. The one requiring the most volume samples (≥mL) is the Capillary Rise technique (CR, Figure 5), which consists in dipping a capillary tube into the liquid of interest and measuring the height of the liquid, h, in the capillary tube. In this approach, the adhesion forces result in the formation of a meniscus at the interface, so that both R1 and R2 can be replaced by R in eq 9 and A/R = π r cos θ, where r is the radius of the liquid column and θ is the contact angle between the liquid and the capillary (often neglected). Expressing m as a function of the liquid density, ρ, and volume of the liquid column (h × π r2) in eq 9 thus allows σ to be determined. This technique has the advantage to convert small forces into a significant height, h, thus lowering the uncertainties compared with direct force measurements such as WP and NR. CR has thus mostly been used for the investigation of artificial mixtures of atmospheric relevance, such as in ref (151).

Other variants of this approach consist in forming a small droplet of the liquid of interest at the tip of a needle or a capillary tube and equilibrating it against its own weight. A very common method is the Pendant Droplet (PD, Figure 5), in which the shape of the droplet is measured with a camera to determine the radii R1 and R2. Comparing the droplet shape with its weight using the Young–Laplace equation (eq 9) provides the value of σ.152 The Drop Volume Tensiometry (DVT), Drop Weight (DW), and Drop Number (DN)153 approaches are based on the same principle than PD, the droplet being formed at the extremity of a capillary and equilibrated with the surface tension force by eq 9 at the time of its detachment. However, instead of measuring the shape of the droplet, the DW and DN techniques consist of measuring the combined weight or volume resulting from several droplets, thus avoiding the need of a camera. The DVT technique is similar to PD, as the volume of the droplet is measured with a camera just before its detachment, but is usually employed for droplets formed inside another liquid. Other approaches that are also based on eq 9 consist of forming a small gas bubble inside of the liquid of interest and measuring either its shape with a camera (Pendant Bubble, PB) or determining its pressure from its curvature (Bubble Pressure, BP, Figure 5).

Several of these gravitational techniques, in particular PD, DW, and DVT, require relatively small volume samples (<100 mL) and, thus, are applicable to atmospheric samples. The techniques based on the formation of bubbles in a liquid, such as DW and PB, require at least several tens of milliliters of samples and thus can be applied to fog or cloudwater samples. DW has thus been used to measure the surface tension of atmospheric fogwater154 and PB for fog and cloudwater.155,156 The PD is the technique requiring the least sample volume (<μL) and also limits the contacts between the sample and laboratory vessels (thus potential contamination) and thus are most applicable to atmospheric aerosol samples, as illustrated by several studies.157−168

3.2. Techniques Applicable to Individual Particles (<μL)

3.2.1. Airborne Particles: Electrodynamic Balance, Optical Tweezers, and Optical Traps (OTs)

Techniques to isolate individual particles with a diameter between 10 and 200 μm in air or microfluidic systems and determine their surface tension have been developed as early as the 1990s.170−172 Airborne particles can be isolated in a small domain by combing oscillating and static electric fields in electrodynamic balance,168 or by levitating them on a focused laser beam or stabilizing them between two crossing beams in optical traps and optical tweezers (Figure 6).24,173−181 In these techniques, the surface tension of the particles is usually determined by inducing first a deformation of the particle, then by monitoring the resulting oscillations from the backscattered light or Quasi-Elastic-Laser Scattering (QELS),168,181,182 from which the surface tension is obtained. Initial deformation and surface oscillations have thus been generated by applying a pulsed electric field,172 coalescing two particles inside the optical trap,174,175,178,180,181 or by applying thermal fluctuations.182 These techniques have the advantage of avoiding contacts between the particles and any surface in the instruments and of being noninvasive, thus avoiding contaminations. The individual particles can be stabilized long enough to vary the RH and study complete adsorption isotherms. The uncertainties reported on the surface tension measurements with these techniques are reported to be of the order of ±1 mN m–1,174 thus substantially larger than with the large-volume techniques for bulk samples because of the inherent difficulties in studying micrometer-size particles. Potential drawbacks of these techniques are that, because of the induced oscillations, they might be measuring a dynamic σ rather than a static one and the analysis performed to determine the surface tension must involve some assumptions on the dynamic behavior of the particle material (density, viscosity, compressibility, etc.). However, by measuring the surface tension of particles in the 5–10 μm size range, these techniques are among the only ones allowing investigating some fundamental aspects, such as the importance of bulk-to-surface partitioning on the surface tension. These techniques also allow one to study other properties of the particles.177 For instance, they could be used to study the role of σ in condensation/evaporation, in nucleation processes, or in the exchange of compounds between the particles and air discussed in Section 2. They are also the most promising techniques to determine another essential parameter related to surface tension: the concentration of the surfactant in individual particles (see Section 6). This information is key in many investigations of the surface tension of particles but particularly challenging to measure. This could potentially be done by adding specific dyes to the particles, that would complex with the surfactant molecules, and measuring their signatures with optical spectroscopies.

Figure 6.

Illustration of an optical tweezer/optical trap: A) Two optical traps are generated using a kinoform on a spatial light modulator (SLM). Once the droplets are confined to the traps, they are moved together to coalesce; B) Elastically scattered light of the event collected with a photodiode and a fast-Fourier transform (FFT) providing the oscillation frequency of the surface modes from which the surface tension is determined; C) Cavity-enhanced Raman spectrum collected with the spectrograph yielding, after analysis of the spectrum with Mie Theory, the radius and refractive index of the droplet resulting from coalescence. The concentration of the cosolute is determined from the refractive index. Reproduced with permission from ref (180). Copyright 2023 American Chemical Society. Licensed under CC-BY 4.0.

3.2.2. Deposited Particles: Nanotensiometry, Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

Another family of techniques allowing the measurements of the surface tension of individual particles are those based on nanotensiometry, i.e., the same principle as the Wilhelmy plate (WP) and Du Noüy ring (NR) techniques, but at microscopic scale: to drop the tip (diameter < a few μm) of an Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM, Figure 7)) instrument or a nanoneedle (typically several 100 of nm in diameter),183 in the sample of interest and measure the force necessary to retrieve it. Atomic Force Microscopy, which is used routinely to study submicrometer details on surfaces, has also been used to measure the surface tension of small surfaces.144 Over the last 10 years it has been used to measure the surface tension of submicrometer atmospherically relevant particles,183−188 as summarized in ref (6). The uncertainties on the surface tension values obtained with such techniques are reported to be on the order of ±0.5 mN m–1. These techniques are the only ones able to investigate particles well below the micrometer-size. It has also the advantages of being a direct determination of σ, i.e., with few intermediate steps and corrections, and to measure a static σ rather than a dynamic one. Its main drawback, however, is that the droplets are not airborne but necessarily deposited on a surface (substrate), thus increasing the risks of contamination of the sample. Potential further development and applications of these different techniques are discussed in Section 6.

Figure 7.

Illustration of surface tension measurements by AFM. A) Top: zoom on the nanoneedle used to probe the surface; bottom: example of force curves obtained from the measurements, from which the surface tension is determined. Reproduced with permission from ref (186). Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society. B) Illustration of the interactions between the AFM tip and microdroplets deposited on a surface. Reproduced with permission from ref (189). Copyright 2023 American Chemical Society. Licensed under CC-BY 4.0.

4. Adsorption Isotherms for Organic/Water Mixtures of Atmospheric Relevance

4.1. Scope of the Inventory

The increase of interest for the surface tension of atmospheric particles over the last 15 years has led to the development of a number of models trying to predict it.7−14 However, the experimental data on the surface tension of atmospherically relevant organic compounds in water, which are needed to validate such models or develop relationships between molecular structure and surface tension, are widely dispersed in the literature. To facilitate these works, this section presents a unique inventory of experimental adsorption isotherms reported in the literature for more than 130 aqueous mixtures of organic compounds. Complete lists of the organic compounds included in this inventory are given in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5: organic acids (Table 1), alcohols, aldehydes, and ketones (Table 2), amines, amino acids, and sugars, (Table 3), amphiphilic compounds in Table 4, and macromolecular compounds (Table 5). Most of these data was measured at 20–25 °C, unless indicated otherwise. The uncertainties reported on these measurements are generally less than ±1% or ±0.2 mN m–1. The complete isotherm data are provided in Sections S2 and S3 of the Supporting Information, reporting all the data sets found in the literature for each compound, those originally published being shown in bold. All the isotherms are presented as a function of both concentration, C (M), and molar fraction, x, of the compound, and the conversion made between these units are presented in Section S1. Whenever available in the literature, other units, such as mass fraction, are also provided in the SI.

Table 2. List of the Binary Mixtures of Aldehydes, Ketones, and Alcohols in Water Included in This Inventory.

| n. | common name (IUPAC Name) | Brut formula | CAS n. | MW (g mol–1) | *σpur (mN m–1) | **ρ (g cm–3)248 | ***Atmos. ? | Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AK1 | formaldehyde (methanal) | CH2O | 50-00-0 | 30.03 | 1.09sa | PD279 | ||

| AK2 | methanol | CH3OH | 67-56-1 | 32.04 | 22.51,280 24,281 22.14,282 25,283 22.7,284 21.8–22.9594 | 0.791 | WP,280,281 DVT,282 BP,283 NR284 | |

| AK3 | acetaldehyde (ethanal) | C2H4O | 75-07-0 | 44.05 | 20.6–21.294 | 0.783 | PD279 | |

| AK4 | ethanol | C2H5OH | 64-17-5 | 46.07 | 22.0,285 21.82,280 22,281 21.72,282 22.07–22.85,286 22.6,284 21.3–23.3294 | 0.789 | CR,285 WP,280,281 DVT,282 DN,286 NR284 | |

| AK5 | acetone (propan-2-one) | C3H6O | 67-64-1 | 58.08 | 23.1,287 23.02,288 24.5,283 21.62–24.0294 | 0.785 | CR,289 BP,283,287 PD,288 NR290 | |

| AK6 | propan-1-ol | C3H7OH | 71-23-8 | 60.1 | 23.28,280 26,291 23.1,292 23.32,282 23.5,284 23.1–23.994 | 0.800 | WP,280 BP,291 CR,151,292 DVT,282 NR,284 CR62 | |

| AK7 | propan-2-ol | C3H7OH | 67-63-0 | 60.1 | 21.22,280 23.5,283 20.34–21.7494 | 0.781 | WP,280 BP283 | |

| AK8 | ethylene glycol (ethane-1,2-diol) | C2H6O2 | 107-21-1 | 62.06 | 46.24,293 47,291 47.6–48.4994 | 1.114 | CR,293 BP291 | |

| AK9 | propylene glycol (propane-1,2-diol) | C3H8O2 | 57-55-6 | 76.09 | 35.46,293 36.6,294 35.6,292 35.8–36.694 | 1.036 | CR,292,293 BP294 | |

| AK10 | propane-1,3-diol | C3H8O2 | 504-63-2 | 76.09 | 45.58,292 46.95,293 45.62–49.294 | 1.054 | CR292 | |

| AK11 | pentan-1-ol | C5H11OH | 71-41-0 | 88.15 | 24.8–25.694 | 0.814 | DVT295 | |

| AK12 | 1,3-butanediol | C4H10O2 | 107-88-0 | 90.12 | 37.04293 | 1.005 | CR293 | |

| AK13 | 1,4-butanediol | C4H10O2 | 110-63-4 | 90.12 | 43.79,293 44.6–47.494 | 1.017 | CR293 | |

| AK14 | glycerol (propane-1,2,3-triol) | C3H8O3 | 56-81-5 | 92.09 | 63.4,296 62.5,285 63.0,292 59.5,189 62.9,189 59.4–63.794 | 1.261 | CR,285,292 WP,189,296 AFM189 | |

| AK15 | phenol (benzenol) | C6H6O | 108-95-2 | 94.11 | 39.59–42.294 | 1.07a | DW260 | |

| AK16 | hexan-1-ol | C6H13OH | 111-27-3 | 102.18 | 24.08–26.5594 | 0.814 | DVT,295 WP297 | |

| AK17 | hexan-2-ol | C6H13OH | 626-93-7 | 102.18 | 24.25–24.794 | 0.818b | WP297 | |

| AK18 | 2,3-dimethylbutan-2-ol | C6H13OH | 594-60-5 | 102.18 | 23.74–23.7494 | 0.824 | WP297 | |

| AK19 | 2-methylpentan-2-ol | C6H13OH | 590-36-3 | 102.18 | 22.58–22.994 | 0.835 | WP297 | |

| AK20 | 1,5-pentanediol | C5H12O2 | 111-29-5 | 104.15 | 44.16,298 43.394 | 0.991 | WP298 | |

| AK21 | p-cresol (4-methylbenzenol) | C7H8O | 106-44-5 | 108.13 | 1.034c | DW260 | ||

| AK22 | heptan-1-ol | C7H15OH | 111-70-6 | 116.2 | 25.7–27.2594 | 0.822 | WP,262 DVT295 | |

| AK23 | hexane-1,2-diol | C6H14O2 | 6920-22-5 | 118.17 | 23.8299 | 0.951d | CR299 | |

| AK24 | hexane-1,6-diol | C6H14O2 | 629-11-8 | 118.17 | 0.96e | CR299 | ||

| AK25 | hexane-1,5-diol | C6H14O2 | 928-40-5 | 118.17 | 33.9299 | 0.971 | CR299 | |

| AK26 | hexane-2,5-diol | C6H14O2 | 2935-44-6 | 118.17 | 31.6299 | 0.961 | CR299 | |

| AK27 | 4-ethylphenol | C8H10O | 123-07-9 | 122.16 | 1.01f | DW260 | ||

| AK28 | octan-1-ol | C8H17OH | 111-87-5 | 130.2 | 25.56–27.994 | 0.826 | NR,300 DVT,295 WP297 | |

| AK29 | octan-2-ol | C8H17OH | 123-96-6 | 130.2 | 25.5–26.794 | 0.819g | WP297 | |

| AK30 | 4-propylphenol | C9H12O | 645-56-7 | 136.19 | 1.009 | DW260 | ||

| AK31 | 1-naphthol (naphthalen-1-ol) | C10H8O | 90-15-3 | 144.17 | 1.28h | NR301 | ||

| AK32 | 2-naphthol (naphthalen-2-ol) | C10H8O | 135-19-3 | 144.17 | 1.28 | NR301 | ||

| AK33 | nonan-1-ol | C9H19OH | 143-08-8 | 144.25 | 27–28.394 | 0.828 | WP297 | |

| AK34 | nonan-5-ol | C9H19OH | 623-93-8 | 144.25 | 0.822 | WP297 | ||

| AK35 | 4-tert-butylphenol | C10H14O | 98-54-4 | 150.22 | 0.908i | DW260 | ||

| AK36 | 4-s-butylphenol | C10H14O | 99-71-8 | 150.22 | 0.986 | DW260 | ||

| AK37 | 2,3-dihydroxynaphthalene | C10H8O2 | 92-44-4 | 160.17 | 1.3p | NR301 |

Data measured at 20–25 °C.

Data measured at 15–25 °C.

Reported in atmospheric aerosols; WP = Whilhelmy plate; PD = pending droplet (shape of a droplet); DVT = drop volume tensiometry, NR = Nouy ring; DN = drop number; DW = drop weight; BP = bubble pressure; CR = capillary rise; sa37 wt.% in H2O, Sigma-Aldrich (pure: 0.815 at 253.15 K248).

Roth, Safety Data Sheet acc. to Regulation (EC) No. 1907/2006 (REACH), Phenol ≥99%, Ph.Eur., crystalline, 3215, 2020, Version 5.0.

Sigma-Aldrich, Safety Data Sheet according to Regulation (EC) No. 1907/2006, 2-Hexanol, 128570, 2023, Version 6.3.

Sigma-Aldrich, Safety Data Sheet according to Regulation (EC) No. 1907/2006, p-Cresol, C85751, 2023, Version 7.2.

Sigma-Aldrich, Safety Data Sheet according to Regulation (EC) No. 1907/2006, 1,2-Hexanediol, 213691, 2022, Version 6.7.

Sigma-Aldrich, Safety Data Sheet according to Regulation (EC) No. 1907/2006, 1,6-Hexanediol for synthesis, 804308, 2023, Version 6.8.

Sigma-Aldrich, Safety Data Sheet according to Regulation (EC) No. 1907/2006, 4-Ethylphenol, E44205, 2023, Version 8.6.

Sigma-Aldrich, Safety Data Sheet according to Regulation (EC) No. 1907/2006, 2-Octanol, O4504, 2023, Version 6.6.

Sigma-Aldrich, Safety Data Sheet according to Regulation (EC) No. 1907/2006, 1-Naphthol for synthesis, 822289, 2023, Version 6.15.

Sigma-Aldrich, Safety Data Sheet according to Regulation (EC) No. 1907/2006, 4-tert-Butylphenol, B99901, 2024, Version 6.11.

Predicted data from ChemSpider (RSC) generated using the ACD/Laboratories Percepta Platform - PhysChem Module version 14.00.

Table 3. List of the Binary Mixtures of Sugars and Amines in Water Included in This Inventory.

| n. | Common name (IUPAC name) | Brut formula | CAS n. | MW (g mol–1) | *σpure (mN m–1) | **ρ (g cm–3)248 | ***Atmos. ? | Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA1 | colamine (2-aminoethan-1-ol) | C2H7NO | 141-43-5 | 61.08 | 48.95,302 48.10,303 48.30,304 48.3–49.2494 | 1.018 | Y196 | WP,302 PD303 |

| SA2 | pyrrolidine (prolamine) | C4H9N | 123-75-1 | 71.12 | 29.75,305 29.65,304 29.23–29.6594 | 0.859 | WP305 | |