Abstract

Background

As healthcare professional trainees, resident physicians are expected to help with COVID-19 care in various ways. Many resident physicians worldwide have cared for COVID-19 patients despite the increased risk of burnout. However, few studies have examined the experience with COVID-19 care among resident physicians and its effects on competency achievement regarding clinical basics and COVID-19 patient care.

Method

This nationwide, cross-sectional Japanese study used a clinical training environment questionnaire for resident physicians (PGY-1 and − 2) in 593 teaching hospitals during the General Medicine In-Training Examination in January 2021. The General Medicine In-Training Examination questions comprised four categories (medical interviews and professionalism; symptomatology and clinical reasoning; physical examination and clinical procedures; and disease knowledge) and a COVID-19-related question. We examined the COVID-19 care experience and its relationship with the General Medicine In-Training Examination score, adjusting for resident and hospital variables.

Results

Of the 6,049 resident physicians, 2,841 (47.0%) had no experience caring for patients with COVID-19 during 2020. Total and categorical General Medicine In-Training Examination scores were not different irrespective of the experience with COVID-19 patient care. For the COVID-19-related question, residents with experience in COVID-19 care showed a significant increase in correct response by 2.6% (95% confidence interval, 0.3–4.9%; p = 0.028).

Conclusions

The resident physicians’ COVID-19 care experience was associated with better achievement of COVID-19-related competency without reducing clinical basics. However, approximately half of the residents missed the critical experience of caring for patients during this unparalleled pandemic in Japan.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12909-024-06085-8.

Keywords: Basic clinical competency, Medical education, COVID-19, Resident physician, General medicine in-training examination (GM-ITE), Clinical knowledge

Background

The coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) has spread worldwide since the end of 2019 [1]. As a result, hospitals received many COVID-19 patients, which affected physicians’ residency training [2]. Many resident physicians globally cared for COVID-19 patients. With the growing demand for COVID-19 care, the opportunity for COVID-19 care increased. However, resident physicians who were exposed to COVID-19 patients experienced a higher rate of stress and burnout compared to those who were not [3]. On the other hand, engaging in COVID-19 care could help physicians learn medical professionalism, system-based care, communication skills, and clinical knowledge of COVID-19 care [4]. Nonetheless, physician trainees must also obtain competency in clinical basics during their training [5].

In Japan, training hospitals may have limited residents’ practice, including in COVID-19 care, to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in their hospital at the early stages of the pandemic. However, the impact of this situation on the achievement of clinical competency among resident physicians has not been elucidated. A two-year residency training program for postgraduate physicians has been mandatory in Japan since 2004 to achieve basic clinical competency. Resident physicians must rotate through different clinical departments, including emergency medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, psychiatry, internal medicine, surgery, and community medicine [6]. The COVID-19 pandemic may have also limited the provision of patient care, including COVID-19 care, by resident physicians who rely on patient care experience to achieve basic clinical competency during the rotation of the residency program.

Furthermore, the global pandemic may have affected resident physicians’ training process; however, no nationwide study has examined the relationship between experience in COVID-19 care and achievement of basic clinical competency during residency training. A nationwide survey in 2020 in Saudi Arabia showed that 43% of resident physicians experienced direct COVID-19 care, with 44% proper use of personal protective equipment (PPE) [7]. In another study, orthopedics and traumatology resident physicians in Germany responded that 80% were set back in time of their general training due to the pandemic [8]. Meanwhile, in Turkey, 90% of family medicine residency trainees were negatively affected by COVID-19, with a total of 31% having depression and 24% facing severe burnout problems [9]. Chinese radiology and U.S. Veterans Affairs residents expressed decreased satisfaction with training [10, 11]. However, few studies have investigated resident physicians’ experience in COVID-19 care and its effects on competency achievement in clinical basics and COVID-19 care. Thus, this study examines the relationship between the experience of caring for patients with COVID-19 and competency in clinical basics and COVID-19 care based on a nationwide General Medicine in-Training Examination (GM-ITE) with a resident survey in Japan.

Methods

Study design

This nationwide, multicenter, cross-sectional study was conducted in Japan. We used a self-reported questionnaire to clarify the educational environment of resident physicians, including their experience of caring for patients with COVID-19. The co-authors iteratively modified this questionnaire independently of the prior literature because the COVID-19 pandemic was unprecedented. We examined the experience of caring for COVID-19 patients and its relationship with the General Medicine In-Training Examination score in 2020, as described below. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Japan Institute for Advancement of Medical Educational Program (JAMEP) (No. 22–25). This cross-sectional study adhered to the STROBE guidelines.

Participants

The present study included postgraduate year 1 (PGY-1) and PGY-2 resident physicians who attempted the General Medicine In-Training Examination in Japan at the end of the 2020 fiscal year (from January 13 to 31, 2021). Only resident physicians who consented to participate in this study were included. Resident physicians with missing data in the self-reported questionnaire, including data on their experience in caring for patients with COVID-19, were excluded.

General medicine in-training examination

The JAMEP, a non-profit organization, has been conducting annual examinations of resident physicians (PGY-1 and PGY-2) to evaluate their basic clinical competency since 2011 [12–17]. The General Medicine In-Training Examination is administered in Japan. It is similar to the US Residency Internal Medicine in-Training Examination that assesses resident physicians’ clinical knowledge. The General Medicine In-Training Examination aims to provide residents and training program directors with an objective, a reliable, and a validated assessment of clinical knowledge. The examination includes important disciplines focusing on primary care to evaluate resident physicians’ competency regarding clinical basics. In January 2021, the General Medicine In-Training Examination included 60 questions on four main topics: medical interviews and professionalism (six questions), symptomatology and clinical reasoning (15 questions), physical examination and clinical procedures (15 questions), and disease knowledge (24 questions). Some of the questions were in video and audio formats. The questions are developed annually by an independent committee of board-certified physicians. The General Medicine In-Training Examination can only be attempted by residents who work in training hospitals authorized to administer the examination.

Data collection and variables

We collected data on resident physicians’ educational environments and hospital characteristics. These characteristics were divided into resident and hospital variables. A self-reporting questionnaire included the following resident variables: PGY grade, sex, desired specialty, rotational training in the Department of GM, rotational training in the Department of Internal Medicine, night duty work in the emergency room (ER) during a residency program, mean number of caring for inpatients, mean self-study time per day, frequency of case conferences per week, and supply of PPE for caring for a patient with COVID-19, from a self-reporting questionnaire sheet. The residents were divided into the following five groups based on the number of COVID-19 patients they treated: 0 patients, 1–10 patients, 11–20 patients, 21–30 patients, and 31 patients or more. The present study defined experiencing care of one or more patients as the presence of experience with COVID-19 (“0 patient” as no experience).

The following training hospital variables were extracted from the hospitals’ websites: the location of each hospital, region (47 prefectures in Japan), region-level state of the COVID-19 pandemic, category of an infectious disease-designated medical institution, hospital function, university hospital or community hospital, and administration type. The high-incidence areas of COVID-19 were determined from published websites, and there were 23 high-incidence areas among the 47 prefectures.

The outcome variables were determined from the total and four categorical General Medicine In-Training Examination scores: (1) general skills (medical interview and professionalism), (2) symptomatology and clinical reasoning, (3) physical examination and clinical procedures, and (4) disease knowledge. In addition, the examination included one COVID-19-specific question, which was developed by two certified physicians for selection validity and reliability (Additional file 1 Supplementary Questionnaire).

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome measure was the General Medicine In-Training Examination score. We examined the difference in General Medicine In-Training Examination scores based on the presence and absence of experience in caring for patients with COVID-19, which was estimated using linear generalized estimating equation (GEE) models by clustering hospitals. The GEE does not require many observations (i.e., physicians) in each cluster (i.e., hospitals) to obtain valid point and interval estimates as the number of clusters increases. The model adjusted for resident variables (graduated years, sex, desired specialty, general medicine rotation, internal medicine rotation, night shift in ER department, number of care patients, study time, frequency of case conference, and PPE supply) and hospital variables (hospital location, hospital function, pandemic area for COVID-19, designated hospitals for specified infectious diseases, urban or rural, university or community hospital, and administration type). A similar model was applied to the COVID-19-specific question (binary outcome); the estimate represented the difference in the correct response rate between the groups. Each background variable was analyzed for association of presence of experience with COVID-19 in univariable and multivariable models using clustered log-linear ‘modified’ Poisson models. Statistical significance was set at a two-tailed p-value < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using the geeglm function in the “geepack” package of the R software.

Results

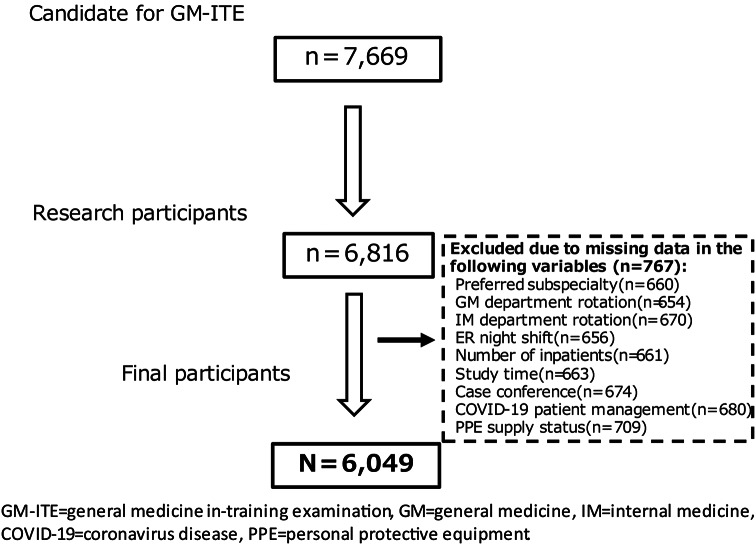

Among the 7,669 residents who attempted the General Medicine In-Training Examination in January 2021 from 593 teaching hospitals, 6,049 residents were finally included in this study (Fig. 1). The response rate was 78.9%. It was found that 2,841 residents cared for 0 COVID-19 patients (47.0%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 45.7–48.2%), 2,733 cared for 1–10 patients (45.2%), 305 cared for 11–20 patients (5.0%), 73 cared for 21–30 patients (1.2%), 97 cared for more than 31 patients (1.6%). There was no significant tendency between the total score of the General Medicine In-Training Examination (including scores of the four test categories) and the number of experiences caring for patients with COVID-19 (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Inclusion criteria flow chart

Table 1 reveals background characteristics divided into resident and hospital variables. The number of male residents exceeded that of female residents. Most of the resident physicians (total 84%) sufficiently supplied PPE in the fiscal year 2020. Training hospitals for residents were more in rural than urban areas.

Table 1.

Background variable (N = 6,049)

| Resident variable | n | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade | PGY-1 | 3,072 | (51) |

| PGY-2 | 2,977 | (49) | |

| Sex | Male | 4,107 | (68) |

| Female | 1,942 | (32) | |

| Hoped specialty department | Internal medicine | 2,163 | (36) |

| Surgery | 1,258 | (21) | |

| General medicine | 146 | (2) | |

| Emergency room | 209 | (3) | |

| Others | 2,273 | (38) | |

| General medicine rotation | No | 3,461 | (57) |

| Yes | 2,588 | (43) | |

| Internal medicine rotation | 0–5 month | 1,182 | (20) |

| 6–10 month | 3,813 | (63) | |

| 11–15 month | 1,054 | (17) | |

| Emergency department duty per month | 0 per month | 218 | (4) |

| 1–2 per month | 927 | (15) | |

| 3–5 per month | 4,255 | (70) | |

| ≥ 6 per month | 617 | (10) | |

| Unknown | 32 | (1) | |

| Care of in-patients | 0–4 patients | 1,420 | (23) |

| 5–9 patients | 3,633 | (60) | |

| 10–14 patients | 675 | (11) | |

| ≥ 15 patients | 172 | (3) | |

| Unknown | 149 | (2) | |

| Study time | 0–30 minutes per day | 2,059 | (34) |

| 31–60 minutes per day | 2,515 | (42) | |

| 61–90 minutes per day | 1,007 | (17) | |

| ≥ 91 minutes per day | 255 | (4) | |

| Unknown | 213 | (4) | |

| Case conferences in a hospital | 0 per week | 990 | (16) |

| 1 per week | 2,987 | (49) | |

| 2 per week | 1,268 | (21) | |

| 3 per week | 348 | (6) | |

| 4 per week | 456 | (8) | |

| PPE supply status | Completely sufficient supply | 2,844 | (47) |

| Sufficient supply | 2,228 | (37) | |

| Neither | 622 | (10) | |

| Insufficient supply | 295 | (5) | |

| Completely insufficient supply | 60 | (1) | |

| Hospital variable | |||

| Location | Rural area | 4,048 | (67) |

| Urban area | 2,001 | (33) | |

| Region | Hokkaido | 206 | (3) |

| Tohoku | 454 | (8) | |

| Kanto | 1,751 | (29) | |

| Chubu | 907 | (15) | |

| Kinki | 1,353 | (22) | |

| Chugoku | 389 | (6) | |

| Shikoku | 232 | (4) | |

| Kyushyu/Okinawa | 757 | (13) | |

| Epidemic area for COVID-19 | Non-contaminated area | 2,605 | (43) |

| Contaminated area | 3,444 | (57) | |

| Category of infectious disease designated medical institution | Specific-designated medical institutions for specified infectious diseases | 4 | (0) |

| Class 1-designated medical institutions for specified infectious diseases | 570 | (9) | |

| Class 2-designated medical institutions for specified infectious diseases | 1,946 | (32) | |

| Non-designated medical institutions for specified infectious diseases | 3,529 | (58) | |

| Hospital function | Small and middle-sized hospital | 1,325 | (22) |

| Advanced treatment hospital | 712 | (12) | |

| Regional medical care support hospital | 4,012 | (66) | |

| University or community hospital | University | 682 | (11) |

| University-branch hospital | 312 | (5) | |

| Community hospital | 5,055 | (84) | |

| Administration type | National hospital organization’s hospital | 260 | (4) |

| Japan community health care organization’s hospital | 60 | (1) | |

| Industrial accident compensation hospital | 140 | (2) | |

| Prefectural hospital | 411 | (7) | |

| Ordinance designated city hospital | 161 | (3) | |

| Municipality-owned hospital | 725 | (12) | |

| Others | 4,286 | (71) | |

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease, PGY = post graduate year, PPE = personal protective equipment

Table 2 shows resident variables associated with the experience of caring for patients with COVID-19. Significant residents’ variables associated with the experience were PGY-2, man, resident physicians who were interested in specialty as ER physicians, resident physicians who worked greater hours in the ER, resident physicians who cared for patients with COVID-19, resident physicians who had a significant amount of study time, and resident physicians who received a sufficient supply of PPE.

Table 2.

Factors associated with the experience regarding the care of patients with COVID-19 (N = 6,049)

| COVID-19 care | Univariable | Multivariable adjusted | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resident variable | n | no (%), n = 2841 | yes (%), n = 3208 | probability ratio | 95%CI | probability ratio | 95%CI | |||||||||

| Grade | PGY-1 | 3,072 | 1,496 | (-48.7) | 1,576 | -51.3 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||||

| PGY-2 | 2,977 | 1,345 | -45.2 | 1,632 | -54.8 | 1.07 | 1 | 1.14* | 1.07 | 1.01 | 1.14* | |||||

| Sex | Male | 4,107 | 1,815 | -44.2 | 2,292 | -55.8 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||||

| Female | 1,942 | 1,026 | -52.8 | 916 | -47.2 | 0.85 | 0.8 | 0.9* | 0.86 | 0.82 | 0.91* | |||||

| Hoped specialty department | Internal medicine | 2,163 | 999 | -46.2 | 1,164 | -53.8 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||||

| Surgery | 1,258 | 575 | -45.7 | 683 | -54.3 | 1.01 | 0.94 | 1.08 | 0.99 | 0.93 | 1.05 | |||||

| General medicine | 146 | 71 | -48.6 | 75 | -51.4 | 0.96 | 0.78 | 1.17 | 1.06 | 0.9 | 1.25 | |||||

| Emergency room | 209 | 64 | -30.6 | 145 | -69.4 | 1.29 | 1.17 | 1.42* | 1.23 | 1.11 | 1.37* | |||||

| Others | 2,273 | 1,132 | -49.8 | 1,141 | -50.2 | 0.93 | 0.88 | 0.99* | 0.96 | 0.91 | 1.01 | |||||

| General medicine rotation | No | 3,461 | 1,634 | -47.2 | 1,827 | -52.8 | 0.99 | 0.9 | 1.004 | 1.02 | 0.94 | 1.08 | ||||

| Yes | 2,588 | 1,207 | -46.6 | 1,381 | -53.4 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | |||||||

| Internal medicine rotation | 0–5 month | 1,182 | 553 | -46.8 | 629 | -53.2 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||||

| 6–10 month | 3,813 | 1,812 | -47.5 | 2,001 | -52.5 | 0.99 | 0.92 | 1.06 | 0.99 | 0.92 | 1.05 | |||||

| 11–15 month | 1,054 | 476 | -45.2 | 578 | -54.8 | 1.04 | 0.94 | 1.15 | 0.99 | 0.91 | 1.09 | |||||

| Emergency department duty per month | 0 per month | 218 | 147 | -67.4 | 71 | -32.6 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||||

| 1–2 per month | 927 | 510 | -55 | 417 | -45 | 1.38 | 1.04 | 1.83* | 1.32 | 1.02 | 1.71* | |||||

| 3–5 per month | 4,255 | 2,017 | -47.4 | 2,238 | -52.6 | 1.62 | 1.2 | 2.18* | 1.45 | 1.13 | 1.86* | |||||

| ≥ 6 per month | 617 | 149 | -24.1 | 468 | -75.9 | 2.33 | 1.71 | 3.17* | 1.97 | 1.54 | 2.51* | |||||

| Unknown | 32 | 18 | -56.3 | 14 | -43.8 | 1.34 | 0.89 | 2.07 | 1.49 | 0.98 | 2.27 | |||||

| Care of in-patients | 0–4 patients | 1,420 | 762 | -53.7 | 658 | -46.3 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||||

| 5–9 patients | 3,633 | 1,718 | -47.3 | 1,915 | -52.7 | 1.14 | 1.04 | 1.24* | 1.04 | 0.97 | 1.12 | |||||

| 10–14 patients | 675 | 244 | -36.1 | 431 | -63.9 | 1.38 | 1.22 | 1.56* | 1.16 | 1.04 | 1.29* | |||||

| ≥ 15 patients | 172 | 43 | -25 | 129 | -75 | 1.62 | 1.37 | 1.92* | 1.33 | 1.12 | 1.57* | |||||

| Unknown | 149 | 74 | -49.7 | 75 | -50.3 | 1.09 | 0.9 | 1.32 | 1.13 | 0.96 | 1.32 | |||||

| Study time | 0–30 minutes per day | 2,059 | 991 | -48.1 | 1,068 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | |||||||

| 51.9) | ||||||||||||||||

| 31–60 minutes per day | 2,515 | 1,188 | -47.2 | 1,327 | -52.8 | 1.02 | 0.96 | 1.08 | 1 | 0.95 | 1.06 | |||||

| 61–90 minutes per day | 1,007 | 454 | -45.1 | 553 | -54.9 | 1.06 | 0.98 | 1.15 | 1 | 0.93 | 1.07 | |||||

| ≥ 91 minutes per day | 255 | 101 | -39.6 | 154 | -60.4 | 1.16 | 1.03 | 1.31* | 1.03 | 0.92 | 1.14 | |||||

| Unknown | 213 | 107 | -50.2 | 106 | -49.8 | 0.96 | 0.84 | 1.1 | 0.96 | 0.86 | 1.08 | |||||

| Case conferences in a hospital | 0 per week | 990 | 493 | -49.8 | 497 | -50.2 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||||

| 1 per week | 2,987 | 1,436 | -48.1 | 1,551 | -51.9 | 1.03 | 0.95 | 1.12 | 1 | 0.93 | 1.07 | |||||

| 2 per week | 1,268 | 562 | -44.3 | 706 | -55.7 | 1.11 | 1 | 1.23* | 1.05 | 0.97 | 1.14 | |||||

| 3 per week | 348 | 145 | -41.7 | 203 | -58.3 | 1.16 | 1.02 | 1.32* | 1.1 | 0.99 | 1.22 | |||||

| 4 per week | 456 | 205 | -45 | 251 | -55 | 1.1 | 0.97 | 1.24 | 1.03 | 0.93 | 1.14 | |||||

| PPE supply status | Completely sufficient supply | 2,844 | 1,253 | -44.1 | 1,591 | -55.9 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||||

| Sufficient supply | 2,228 | 1,090 | -48.9 | 1,138 | -51.1 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.94* | 0.93 | 0.9 | 0.99* | |||||

| Neither | 622 | 324 | -52.1 | 298 | -47.9 | 0.86 | 0.77 | 0.92* | 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.998* | |||||

| Insufficient supply | 295 | 139 | -47.1 | 156 | -52.9 | 0.95 | 0.83 | 0.93* | 0.95 | 0.85 | 1.03 | |||||

| Completely insufficient supply | 60 | 35 | -58.3 | 25 | -41.7 | 0.75 | 0.54 | 1.02 | 0.88 | 0.69 | 1.13 | |||||

| Hospital variable | ||||||||||||||||

| Location | Rural area | 4,048 | 2,241 | -55.4 | 1,807 | -44.6 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||||

| Urban area | 2,001 | 600 | -30 | 1,401 | -70 | 1.57 | 1.41 | 1.75* | 1.25 | 1.14 | 1.38* | |||||

| Region | Hokkaido | 206 | 97 | -47.1 | 109 | -52.9 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||||

| Tohoku | 454 | 320 | -70.5 | 134 | -29.5 | 0.56 | 0.38 | 0.81* | 0.87 | 0.6 | 1.26 | |||||

| Kanto | 1,751 | 556 | -31.8 | 1,195 | -68.2 | 1.29 | 1.07 | 1.56* | 1.28 | 1.09 | 1.51* | |||||

| Chubu | 907 | 445 | -49.1 | 462 | -50.9 | 0.96 | 0.77 | 1.2 | 1.08 | 0.9 | 1.3 | |||||

| Kinki | 1,353 | 517 | -38.2 | 836 | -61.8 | 1.17 | 0.97 | 1.41 | 1.22 | 1.03 | 1.45* | |||||

| Chugoku | 389 | 284 | -73 | 105 | -27 | 0.51 | 0.35 | 0.74* | 0.84 | 0.58 | 1.23 | |||||

| Shikoku | 232 | 184 | -79.3 | 48 | -20.7 | 0.39 | 0.28 | 0.55* | 0.69 | 0.46 | 1.01 | |||||

| Kyushyu/Okinawa | 757 | 438 | -57.9 | 319 | -42.1 | 0.8 | 0.62 | 1.23 | 1 | 0.8 | 1.26 | |||||

| Epidemic area for COVID-19 | Non-contaminated area | 2,605 | 1,765 | -67.8 | 840 | -32.2 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||||

| Contaminated area | 3,444 | 1,076 | -31.2 | 2,368 | -68.8 | 2.13 | 1.86 | 2.44* | 1.53 | 1.3 | 1.79* | |||||

| Category of infectious disease designated medical institution | Specific-designated medical institutions for specified infectious diseases | 4 | 3 | -75 | 1 | -25 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||||

| Class 1-designated medical institutions for specified infectious diseases | 570 | 280 | -49.1 | 290 | -50.9 | 2.04 | 0.25 | 16.4 | 2.92 | 0.35 | 24.78 | |||||

| Class 2-designated medical institutions for specified infectious diseases | 1,946 | 1,072 | -55.1 | 874 | -44.9 | 1.8 | 0.22 | 14.4 | 2.4 | 0.29 | 20.11 | |||||

| Non-designated medical institutions for specified infectious diseases | 3,529 | 1,486 | -42.1 | 2,043 | -57.9 | 2.32 | 0.29 | 18.5 | 2.55 | 0.3 | 21.37 | |||||

| Hospital function | Small and middle-sized hospital | 1,325 | 644 | -48.6 | 681 | -51.4 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||||

| Advanced treatment hospital | 712 | 411 | -57.7 | 301 | -42.3 | 0.82 | 0.63 | 1.08 | 0.86 | 0.71 | 1.04 | |||||

| Regional medical care support hospital | 4,012 | 1,786 | -44.5 | 2,226 | -55.5 | 1.08 | 0.95 | 1.23 | 1.08 | 0.99 | 1.18 | |||||

| University or community hospital | University | 682 | 400 | -58.7 | 282 | -41.3 | 0.77 | 0.6 | 1 | 1 | 0.78 | 1.27 | ||||

| University-branch hospital | 312 | 89 | -28.5 | 223 | -71.5 | 1.34 | 1.17 | 1.53* | 1.02 | 0.88 | 1.18 | |||||

| Community hospital | 5,055 | 2,352 | -46.5 | 2,703 | -53.5 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | |||||||

| Administration type | National hospital organization’s hospital | 260 | 160 | -61.5 | 106 | -40.8 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||||

| Japan community health care organization’s hospital | 60 | 12 | -20 | 48 | -80 | 2.01 | 1.28 | 3.16* | 1.44 | 0.996 | 2.08 | |||||

| Industrial accident compensation hospital | 140 | 56 | -40 | 84 | -60 | 1.51 | 0.9 | 2.52 | 1.04 | 0.71 | 1.52 | |||||

| Prefectural hospital | 411 | 280 | -68.1 | 131 | -31.9 | 0.8 | 0.49 | 1.32 | 0.97 | 0.64 | 1.47 | |||||

| Ordinance designated city hospital | 161 | 52 | -32.3 | 109 | -67.7 | 1.7 | 1.11 | 2.61* | 1.14 | 0.7 | 1.86 | |||||

| Municipality-owned hospital | 725 | 354 | -48.8 | 371 | -51.2 | 1.28 | 1.11 | 0.85 | 1.26 | 0.88 | 1.8 | |||||

| Others | 4,286 | 1,927 | -45 | 2,359 | -55 | 1.38 | 0.94 | 2.03 | 1.13 | 0.81 | 1.58 | |||||

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease, PGY = post graduate year, PPE = personal protective equipment. p < 0.05

Multivariable model adjusted for resident and hospital variables

Resident variable: number of years since graduation, sex, hoped/preferred specialty, general medicine rotation, internal medicine rotation, emergency department duty per month, number of care patients, study time, frequency of case conferences, and PPE supply

Hospital variable: hospital location, hospital function, epidemic area for COVID-19, designated medical institutions for specified infectious diseases, urban or rural, university or community hospital, administration type

Table 2 also includes hospital variables associated with the experience of caring for patients with COVID-19. Significant hospital variables associated with the experience were urban areas, Kanto (close to Tokyo) or Kinki (close to Osaka), high-incidence areas for COVID-19, and non-designated hospitals for specified infectious diseases.

Sixty questions were provided in the General Medicine In-Training Examination in January 2021. As shown in Table 3, univariable GEE analysis of the relationship between difference in General Medicine In-Training Examination scores based on the experience in caring for patients with COVID-19 revealed the following: total score (score difference 0.436, 95% CI, 0.052–0.820; p = 0.026), symptomatology and clinical reasoning (score difference 0.120, 95%CI, 0.001–0.238; p = 0.047), and COVID-19-related question (score difference 0.046, 95%CI, 0.023–0.069; p < 0.001). After adjustment for resident and hospital variables, the COVID-19-related question (score difference 0.026, 95%CI, 0.003–0.049; p = 0.028) was significantly associated with experience in caring for patients with COVID-19 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Relationship between COVID-19 care and General Medicine In-Training examination score (univariable and multivariable-adjusted linear generalized estimating equations analysis)

| Univariable | Multivariable adjusted | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 care | Mean score | Score difference | 95%CI | p-value | Score difference | 95%CI | p-value | |||

| Total (score, 0–60) | no experience | 28.85 | reference | reference | ||||||

| experience | 29.28 | 0.436 | 0.052 | 0.820 | 0.026* | 0.242 | -0.128 | 0.611 | 0.200 | |

| Medical Interview and Professionalism (score, 0–6) | no experience | 2.89 | reference | reference | ||||||

| experience | 2.93 | 0.041 | -0.027 | 0.109 | 0.230 | 0.008 | -0.061 | 0.076 | 0.824 | |

| Symptomatology and Clinical Reasoning (score, 0–15) | no experience | 8.54 | Reference | reference | ||||||

| experience | 8.66 | 0.120 | 0.001 | 0.238 | 0.047* | 0.069 | -0.049 | 0.187 | 0.254 | |

| Physical Examination and Clinical Procedures (score, 0–15) | no experience | 6.71 | reference | reference | ||||||

| experience | 6.83 | 0.116 | -0.01 | 0.243 | 0.072 | 0.061 | -0.074 | 0.196 | 0.372 | |

| Disease Knowledge (score, 0–24) | no experience | 10.70 | reference | reference | ||||||

| experience | 10.86 | 0.159 | -0.04 | 0.358 | 0.120 | 0.104 | -0.089 | 0.296 | 0.292 | |

| COVID-19 related question (score, 0–1) | no experience | 0.80 | reference | reference | ||||||

| experience | 0.85 | 0.046 | 0.023 | 0.069 | < 0.001* | 0.026 | 0.003 | 0.049 | 0.028* | |

GM-ITE = general medicine in-training examination, COVID-19 = coronavirus disease, CI = confidence interval, * p < 0.05

Estimates of the coefficients of COVID-19 management experience in linear generalized estimating equation models, including hospitals as clusters with the independent working correlation structure. The interpretation of coefficients is the mean difference of scores (total score and scores in subject-specific areas) or difference in correct answer rates (COVID-19-related question)

Multivariable model adjusted for resident-level and hospital-level variables

Resident variable: number of years since graduation, sex, hoped/preferred specialty, general medicine rotation, internal medicine rotation, emergency department duty per month, number of care patients, study time, frequency of case conferences, and PPE supply

Hospital variable: hospital location, hospital function, epidemic area for COVID-19, designated medical institutions for specified infectious diseases, urban or rural, university or community hospital, administration type

Discussion

The present study is the first to use nationwide data from Japan to investigate the effect of caring for patients with COVID-19 on the educational achievements of resident physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Fewer than half of the Japanese resident physicians (47%) had no experience caring for COVID-19 patients in 2020. It was found that experience in caring for patients with COVID-19 did not significantly affect the total score obtained in the General Medicine In-Training Examination, but it did affect the score for the COVID-19-related question; resident physicians who had experience in treating patients with COVID-19 scored higher than those who did not.

An unexpected finding was that approximately half of the Japanese resident physicians (47%) did not care for COVID-19 patients during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. The result revealed that percentage of Japanese resident physicians with experience in COVID-19 is too low, even though it is early in the COVID-19 pandemic. However, almost all cared for in-patients and worked in the ER 3–5 times a month (Table 1). Furthermore, in the initial phase of the COVID-19 epidemic, the ER training frequency of the Japanese resident physicians was almost the same as that before the outbreak. Thus, training hospitals in rural and non-contaminated areas could have failed to provide resident physicians with the opportunity to care for patients with COVID-19 (Table 2).

As mentioned earlier, the present study revealed that COVID-19 care did not affect resident physicians’ General Medicine In-Training Examination scores. This suggests that resident physicians who cared for patients with COVID-19 did not experience a reduction in educational achievement. Perhaps because the ratio of resident physicians who cared for over 21 patients with COVID-19 was low (2.8%) in the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic, indicating a low medical load, COVID-19 care did not reduce education achievement. Moreover, caring for patients with COVID-19 may improve clinical knowledge associated with COVID-19 care; the COVID-19-related question was correctly answered by over 80% of the resident physicians, as shown in Table 3. This question has a 4.6% significance level for the correct answer rate between the presence and absence of experience in caring for patients with COVID-19, which may be valuable for clinical practice. Therefore, experience of caring for patients with COVID-19 may contribute to the acquisition of clinical knowledge, and COVID-19 care may not negatively impact Japanese resident physicians’ educational outcomes.

In the sub-analysis of the number of experiences caring for COVID-19 patients (data not shown), the univariable analysis showed no difference in General Medicine In-Training Examination scores between the 0 patients, 1–20 patients, or > 21 patients groups. The analysis found a tendency for a sufficient supply of PPE and an increased number of care for patients with COVID-19. This result indicates that training hospitals with sufficient PPE supply were affirmatively involved in resident physicians’ training for COVID-19 care early in the COVID-19 pandemic. In a further sub-analysis between the PGY-1 and PGY-2, the same tendency was observed in the correct answer rate to the COVID-19-related question and experience in caring for patients with COVID-19 (Additional file 2 Supplementary Table). However, among only the PGY-2 resident physicians, experience in caring for patients with COVID-19 was significantly associated with the correct answer of the COVID-19-related question (Additional file 2 Supplementary Table). Thus, it may be speculated that those in PGY-2 had not only more experience in but also greater responsibility toward patient care, including of patients with COVID-19, than those in PGY-1 [18].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first multilevel study to determine the relationship between experience in caring for COVID-19 patients and the medical achievement of resident physicians. Extant studies have examined the medical education of under-graduate medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic [19–21]. However, only a few studies have qualitatively examined the post-graduate medical education of resident physicians [4, 22–25]. Previous research has focused on specific department resident physicians (e.g., emergency medicine in the U.S., surgery in the Netherlands, and surgery and anesthesiology in the U.S.) and used a small sample of resident physicians. The present study examined the characteristics of resident physicians in various departments. Therefore, the results of this study may be useful for resident physicians in other countries with a similar rotational system.

Furthermore, the sample size was large, accounting for one-third of the resident physicians in Japan. In short, among about 18,000 resident physicians reported by the Japanese government [26], the present study involved 6,049 resident physicians. Therefore, this study has high internal validity because of the large sample size. In addition, the General Medicine In-Training Examination has been administered over a long period since 2011, with an increasing number of resident physicians attempting it (data not shown); thus, the examination score is highly reliable.

However, the study has some limitations. First, we studied the relationship between the experience in caring for patients with COVID-19 and the resident physicians’ General Medicine In-Training Examination score for only one year, that is, during the COVID-19 pandemic. The training environment for resident physicians has changed every year since the pandemic. Therefore, additional longitudinal analysis might highlight the effects of COVID-19 care and COVID-19-specific knowledge on some of the four categories, including medical interviews and professionalism, symptomatology and clinical reasoning, physical examination and clinical procedures, and disease knowledge. Second, this study did not include all the participants from training hospitals in Japan. Third, only one question in the study was related to the COVID-19. Fourth, our study has a cross-sectional design; thus, the results cannot explain the causal relationship between COVID-19 care and the score for the COVID-19-related question. Furthermore, this study could not identify a correlation between the number of experiences caring for patients with COVID-19 and the General Medicine In-Training Examination score (sub-analysis finding, data not shown). Additionally, other aspects of the different services of care for patients with COVID-19 were not considered in this study.

Consequently, future studies are needed to clarify the appropriate number of experiences caring for patients with COVID-19 during residency training. A longitudinal study with more detailed questions on the experience of caring for patients with COVID-19 is required to contribute to COVID-19 residency training.

Conclusion

COVID-19 care provided by Japanese resident physicians did not affect the General Medicine In-Training Examination score; however, it did highlight an improvement in the score on the COVID-19-related question. Therefore, experience in caring for patients with COVID-19 is important for effective training in the management of COVID-19 infection.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the JAMEP secretaries for their support.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease-2019

- GM-ITE

General medicine in-training examination

- JAMEP

Japan institute for advancement of medical educational program

- PGY

Postgraduate year

- PPE

Personal protective equipment

- GEE

Generalized estimating equation

- ED

Emergency room

- CI

Confidence interval

- GM

General Medicine

- IM

Internal Medicine

Author contributions

S.N. and Y.N. had the original idea for the paper, which was further developed in discussions with A.G., M.I., K.S., K.K., T. Shimizu, Y. Y., S.F., and Y.T., and led the statistical analyses. T. Shinozaki contributed to the interpretation of findings and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All the authors contributed to drafting the manuscript. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Health, Labour and Welfare Policy Grants of Region Medical (21IA2004) from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare and by JSPS KAKENHI Grant (21K17229).

Data availability

The data and materials will not be officially available because the informed consent of participants in each hospital does not permit such publication. The corresponding author will respond upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All the procedures were followed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the ethics review board of the Japan Institute for Advancement of Medical Educational Program (JAMEP) (approval number 21 − 9). Written consent was obtained from participants to participate in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

K.S. of the authors is an Editorial Board Member. Y.N. received an honorarium from the Japan Institute for Advancement of Medical Education Program (JAMEP) as a GM-ITE project manager. Y.T. is the director of JAMEP; he and H.K. and K.S. received an honorarium from JAMEP for delivering lectures for the JAMEP. T.Shimizu, Y.Y., K.S., and S.F. received honoraria from JAMEP as exam preparers for the GM-ITE. S.N., M.H., A.G., M.I., T.Shinozaki., K.K., and S.F. have declared no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation [Report]– 51 2020.

- 2.Joishy SK, Sadohara M, Kurihara M. Complexity of the diagnosis of COVID-19 in the context of pandemicity: need for excellence in diagnostic acumen. Korean J Fam Med. 2022;43(1):16–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kannampallil TG, Goss CW, Evanoff BA, et al. Exposure to COVID-19 patients increases physician trainee stress and burnout. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(8):e0237301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen SY, Lo HY, Hung SK. What is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on residency training: a systematic review and analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peter Densen. Challenges and opportunities facing medical education. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2011;122:48–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Ministerial Ordinance Resid Train Stipulated Paragraph 2002;1:article 16 – 2 of the Medical Practitioners Act.

- 7.Balhareth A, AlDuhileb MA, Aldulaijan FA, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on residency and fellowship training programs in Saudi Arabia: a nationwide cross-sectional study. Ann Med Surg. 2020;57:127–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adl AD, Herbolzheimer M, Lutz PM, et al. Effects of the SARS-CoV–2 pandemic on residency training in orthopedics and traumatology in Germany: a nationwide survey. Orthopadie (Heidelb). 2022;51(10):844–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Çevik H, Ungan M. The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health and residency training of family medicine residents: findings from a nationwide cross-sectional survey in Turkey. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22(1):226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang P, Zhang J, Chen Y, et al. The satisfaction with radiology residency training in China: results of a nationwide survey. Insighs Imaging. 2022;13(1):196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Northcraft H, Bai J, Griffin AR, et al. Association of the COVID-19 pandemic on VA resident and fellow training satisfaction and future VA employment: a mixed methods study. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14(5):593–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishizaki Y, Nagasaki K, Shikino K, et al. Relationship between COVID-19 care and burnout among postgraduate clinical residents in Japan: a nationwide cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2023;13(1):e066348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimizu T, Tsugawa Y, Tanoue Y, et al. The hospital educational environment and performance of residents in the General Medicine In-Training examination: a multicenter study in Japan. Int J Gen Med. 2013;6:637–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kinoshita K, Tsugawa Y, Shimizu T, et al. Impact of inpatient caseload, emergency department duties, and online learning resource on General Medicine In-Training examination scores in Japan. Int J Gen Med. 2015;8:355–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mizuno A, Tsugawa Y, Shimizu T, et al. The impact of the Hospital volume on the performance of residents on the General Medicine In-Training examination: a Multicenter Study in Japan. Intern Med. 2016;55:1553–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishizaki Y, Shinozaki T, Kinoshita K, et al. Awareness of diagnostic error among Japanese residents: a nationwide study. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:445–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishizaki Y, Mizuno A, Shinozaki T, et al. Educational environment and the improvement in the General Medicine In-training examination score. J Gen Fam Med. 2017;18:312–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cowley DS, Markman JD, Best JA, et al. Understanding ownership of patient care: a dual-site qualitative study of faculty and residents from medicine and psychiatry. Perspect Med Educ. 2017;6(6):405–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim JW, Myung SJ, Yoon HB, et al. How medical education survives and evolves during COVID-19: our experience and future direction. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0243958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Byrne L, Gavin B, McNicholas F. Medical students and COVID-19: the need for pandemic preparedness. J Med Ethics. 2020;46:623–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaul V, Gallo de Moraes A, Khateeb D, et al. Medical Education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Chest. 2021;159:1949–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poelmann FB, Koëter T, Steinkamp PJ, et al. The immediate impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on burn-out, work-engagement, and surgical training in the Netherlands. Surgery. 2021;170:719–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ford TR, Fix ML, Shappell E, et al. Beyond the emergency department: effects of COVID-19 on emergency medicine resident education. AEM Educ Train. 2021;5:e10568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nofi C, Roberts B, Demyan L, et al. A survey of the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on skill decay among surgery and anesthesia residents. J Surg Educ. 2022;79:330–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El Mouedden I, Hellemans C, Anthierens S, et al. Experiences of academic and professional burn-out in medical students and residents during first COVID-19 lockdown in Belgium: a mixed-method survey. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22:631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ministry of Health. Labour and Welfare. A result of matching between a resident and a clinical teaching hospital in 2019 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data and materials will not be officially available because the informed consent of participants in each hospital does not permit such publication. The corresponding author will respond upon reasonable request.