Abstract

Background

Strategies to promote workplace mental health can target system, organization, team, and individual levels exclusively or in concert with each other. Creating toolkits that include these different levels is an emerging innovative strategy to support employees working in various sectors. Our paper describes the development, implementation, and refinement of two different online toolkits: the Healthy Professional Worker Toolkit for Education Workers and the Health Worker Burnout Toolkit.

Methods

The Knowledge to Action Framework guided the team during the development and early interventions phases of toolkit development. Stakeholder engagement regarding the intended use of the toolkit of promising practices for workplace interventions was integrated throughout with different forms of feedback in a research capacity between 2022 and 2024.

Results

Reflecting on the different phases of the KTA Framework, we describe first the engagement involved in building the toolkits and then on their utilization. Our toolkits were built to include different resources aimed at empowering workers, teams, and employers offering innovative ideas to address the mental health-leaves of absence and return to work cycle in one case and the different forms and consequences of burnout in the other. Criteria for inclusion were informed by ongoing research with a range of stakeholders and other intended toolkit users including managers, supervisors, executives, human resource specialists, staff, and others in healthcare and educational organizations and settings. In the implementation phase, the volume of resources available in each toolkit considered a strength by some was overwhelming for some partners and individual workers to navigate. Capacity, engagement, time, and readiness for change, are themes that heavily influenced if and when organizations interacted with each toolkit, and how much time they spent exploring the resources provided.

Conclusion

It is critical to ground toolkits in the experiential evidence of workplace mental health as is linking these to evidence-informed interventions that correspond to workplace concerns. Organizational readiness to adopt and adapt resources and implement changes is a key consideration. Ultimately, user engagement is what brought these toolkits to life.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-024-20039-1.

Keywords: Toolkits, Mental health, Burnout, Engagement, Capacity, Health worker, Professional worker

Background

Maintaining positive mental health in the workplace is a priority for many countries and organizations. Some countries have implemented workplace mental health standards and frameworks. In Canada, the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC), created the National Standard for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace (the Standard) [1]. The Centre of Expertise on Mental Health in the Workplace, created by the Canadian government, includes resources in alignment with the Standard for organizations, managers, employees, and executives, and offers training related to mental health in the workplace [2]. Programs such as Mental Health First Aid and The Working Mind continue to provide evidence-based mental health training while also reducing the stigma associated with seeking mental health support [3].

WorkWell in England is similarly developing a national health at work standard which aims to support the increasing number of people out of work due to ill health by focusing on early intervention [4]. Organizations in the United Kingdom (UK) have implemented role-based interventions in the workplace where a ‘business champion’ is employed and supported to create, distribute, and assess healthy workplace initiatives [5]. Others have focused on prevention by using artificial intelligence to monitor individual health trends and identify early warning signs of employee ill health [4].

In the United States (US), the Surgeon General developed a Framework for Workplace Mental Health & Well-Being which offers a foundation for organizations to build on and emphasizes protection from harm, connection and community, work-life harmony, ‘mattering’ at work, and opportunity for growth with a focus on workers’ voices and equity [6].

Such standards and frameworks provide high level guidance, but evidence suggests that system, organization and individual level approaches are more effective at addressing workplace mental health issues when combined, and especially when they utilize participatory approaches (i.e., co-worker support, employer-employee interactions) [7]. Work-related stressors embedded in an organization’s culture and climate can be addressed by creating healthy work environments that embrace non-stigmatizing strategies to improve employees’ well-being [8]. For sustainable change to occur, workplace cultures that encourage learning and empower workers need to be fostered [9]. The presence of feedback loops between an organization and its workers increases worker perceptions of control within the workplace [10]. Workers want to be supported by leadership and receive clear communication surrounding the socialization, sustainability, and availability of mental health interventions [8].

A means by which to integrate interventions to address mental health in the workplace across different levels includes the development of toolkits that can be utilized by various stakeholders. Toolkits can take on a variety of forms but is typically a curated resource that provides practical advice, guidance, and information on a particular subject [11]. They may include guidelines, policies, procedures, programs, training, documents, or websites to assist users. Toolkits aim to help organizations and individuals cultivate and sustain the health and wellbeing of workers [12]. Despite a growth of virtual toolkits that exist, there is much we do not know about their development for, uptake in and effectiveness for different workplaces. For example, how and what resources are included? How many of them are being utilized? How are they formally evaluated? Do these toolkits make a difference for individuals, teams, and organizations seeking to address mental health in the workplace?

Our team received funding for two research projects for which we developed two distinct toolkits targeting different facets of workers’ health and well-being. The first toolkit was a component of a larger Healthy Professional Worker (HPW) study which sought to examine the mental health, leave of absence, and return to work trajectories of seven different professional workers in Canada [13]. For example, the HPW toolkit for education workers was developed to address concerns about a lack of resources to address their specific workplace mental health concerns.

The Health Worker Burnout (HWB) toolkit was designed to be more inclusive of all health workers with a specific focus on burnout. An additional goal of the HWB study was to partner with organizations interested in adopting the toolkit to choose a fit-for-purpose package of interventions to address burnout at their particular site [14]. Both toolkits were technically structured in a similar way employing a set of screening criteria and applying coding options that included audience, format, focus, and other features, with links to the external resources our teams shortlisted for relevance and efficacy. Details on toolkit development are found in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

HWB toolkit development

| Focus of Intervention | Format | Intervention Levels | Users |

|---|---|---|---|

| Promoting mental health | Video/Webinar | System | Worker |

| Managing workload | Course/Training/Workshop | Organization | Educator |

| Handling conflict, bullying & harassment | Guide | Team | Other/Mixed |

| Confronting discrimination | Policy | Individual | Employer |

| Program | Multileveled | Trainee | |

| Document/Report | |||

| Other | |||

| Toolkit | |||

| Website |

Table 2.

HPW education worker toolkit development

| Focus of intervention | Format | Location | Users |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preventing burnout | Article | Alberta | Trainee |

| Addressing burnout | Book | British Columbia | Educator |

| Accommodating burnout | Podcast | Ontario | Administrator |

| Policy | Quebec | School Board | |

| Program | Canada | ||

| Report | United States | ||

| Other | Worldwide | ||

| Toolkit | Virtual | ||

| Training | United Kingdom | ||

| Video | |||

| Website | |||

| Workshop |

Across both studies, we drew upon the Knowledge to Action (KTA) Framework [15] to help guide the team regarding the intended use of the toolkit with different levels of feedback from development and implementation partners. In this paper, we describe each toolkit, the engagement process undertaken in their development and refinement and share valuable insights regarding their utilization potential.

Methods

Guiding knowledge to action framework

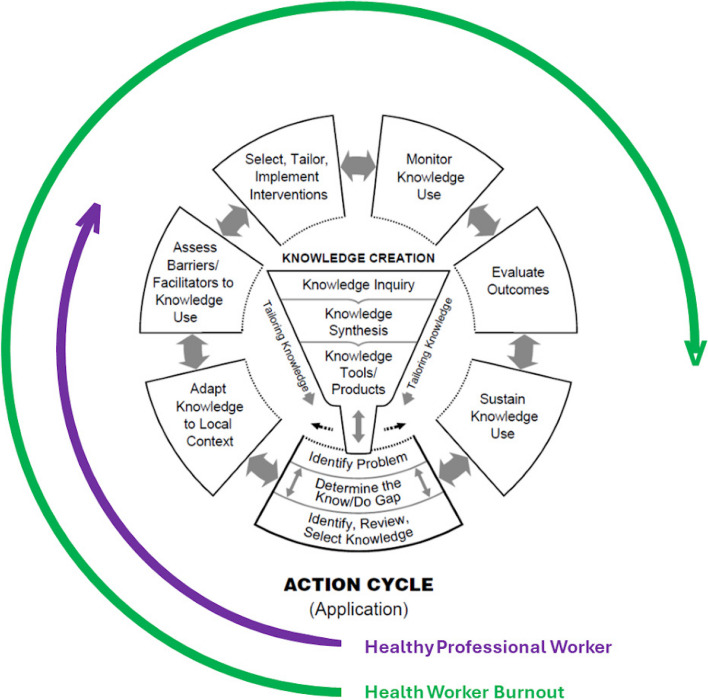

Developed by Graham and colleagues (2006), the KTA Framework provides a deliberate approach for making change, including a seven-phase cycle to move knowledge into practice [15] (Fig. 1). The knowledge creation process starts with inquiry and synthesis producing tools and products that are adapted to local contexts for which unique barriers and facilitators are experiences requiring further tailoring and monitoring with outcomes evaluated and sustained.

Fig. 1.

The knowledge to action cycle from Strauss S, Tetroe J, & Graham I: Knowledge translation in health care: moving from evidence to practice. Second edition, 2013, p. 10. Modified and reprinted with permission from John Wiley and Sons

Different parts of the KTA cycle were integrated into the development and implementation of the HPW and HWB toolkits as indicated in Fig. 1. For phase 1 this included a synthesis of relevant literature, complemented with an empirical survey and semi-structured interview data from workers and key stakeholders about promising practices to address their mental health and burnout experiences.

The HPW Toolkit for Education Workers involved phases 1 to 3 of the action cycle (Table 3 column 1). It was developed based on 980 surveys [16] and 53 semi-structured interviews (Supplement 1) conducted with education workers and 26 stakeholders from across Canada and included a targeted review of the literature on relevant interventions. The focus of the selection of interventions were informed by the empirical data. Once developed, the toolkit was presented to two partner organizations for feedback on toolkit refinement. We received valuable feedback about sharing our research findings at the beginning of toolkit development to provide context for users. Partner organizations also recommended resources pertaining to violence and microaggressions which were later added to the toolkit. Implementation of the toolkit was not part of the study protocol, but uptake is ongoing among partner organizations.

Table 3.

Sources of evidence for the HPW education worker & HWB toolkits

| KTA phase | Healthy professional worker—education worker toolkit | Health worker burnout toolkit |

|---|---|---|

|

Phase 1 knowledge creation |

980 Education Worker Surveys 53 Education Worker Interviews 26 Stakeholder Interviews 49 Intervention Literature Sources |

154 Intervention Literature Sources |

| Phase 2 adapt |

4 partner organization presentations November 2022—National Staff Conference October 2023—Presentation/Workshop to Educational Services Officers March 2023—Presentation/Workshop to Educational Services Committee June 2024—Presentation to National Teachers’ Research Network Meeting Video guide and five additional intervention sources added to toolkit |

Initial Worker Surveys—141 Initial Worker Interviews—24 participants |

| Phase 3 barriers & facilitators |

A presentation to all staff including management was undertaken at each site Two additional intervention sources added to toolkit |

|

| Phase 4 tailor interventions |

Partner #1—5–7 Shortlisted interventions Partner #2—7 Shortlisted interventions |

|

| Subsequent meetings to wellness leadership teams—10–12 across both sites | ||

| Phase 5 monitor |

Partner #1—Implemented 4 adapted interventions Partner #2—Implemented 1 adapted interventions |

|

| Phase 6 evaluate outcomes |

128 Follow up Worker Surveys 10 Follow Up Worker and Manager Interviews |

The HWB Toolkit was developed employing a similar methodology to the HPW toolkits which was then utilized by four clinical sites in a large urban Canadian city that advanced to phase 6 of the cycle (Table 3 column 2). Initial selection and curation of the toolkit elements was undertaken before engaging with four clinical sites, informed in part by the health worker professional case studies of the HPW study [17]. Following the conduct of worker surveys, and semi-structured interviews and focus groups (Supplement 2) with management teams in partnering organizations, refinement and additional interventions were added to address identified resource gaps. Our approach was to meet each clinical site where they were at, informed by the empirical data, and work to co-develop a set of interventions that would address the issues impacting burnout in their organizations. Relationship building with partner organizations was part of the work plan from the onset, making it more likely that uptake, implementation, and sustainability would occur.

Results

Reflecting on the question we posed at the outset—if we build it, will they come—we transpose each of these questions onto the different phases of the KTA Framework.

“Building it”

Toolkit structure and format

The HPW and HWB toolkits curate evidence-informed strategies to address different facets of workplace mental health, discussed below, and are structured in similar ways. Both are online, open access and categorize interventions in the toolkit according to four levels: system, organization, team, and individual. Both contain a filtering option on the left-hand side where users can search for resources by format, location, cost, or language (the HWB toolkit is also available in French as well as English). Users can choose from a variety of formats such as articles, websites, podcasts, and programs. There is also an opportunity for users to leave comments about resources they found helpful to create a community of support for education workers. The target users for the HPW Education Worker toolkit are inclusive of teachers, early childhood educators, and educational assistants. The target users for the HWB toolkit are inclusive of all health workers across sectors and from different practitioner backgrounds.

Toolkit content: healthy professional worker – education worker toolkit

During the knowledge creation phase of the KTA framework, we listened to what education workers had to say about their mental health, leaves of absence and return to work experiences (Supplement 3) and complemented with a search of the grey and academic literature for high-quality evidence-based resources. We were particularly interested in what they would identify as the promising practices that would address their experiences in a more supportive way facilitating leaves of absence and enhanced return to work. Education workers made it very clear that they are not interested in individual wellness initiatives where the onus is on them to “fix” themselves. Indeed, we found education worker mental health is predominantly influenced at a system level (e.g., staffing and workload) thus requires system-level interventions, such as reducing large class sizes and increasing support staff. Adapting this feedback to the realities of the school system was an important consideration when developing the Education Worker Toolkit, because engaging in a wellness webinar or practicing yoga is not helpful when the education system is not set up to promote educators’ positive mental health. Education workers mentioned more support and funding for mental health followed by more preparation time as promising practices to improve education worker mental health. Education workers discussed streamlining the paperwork process for leaves of absence and return to work and the importance of building a culture of care for each other within the education system.

During a combined phase 2 and 3 of the KTA cycle applicability and assessment of potential barriers and facilitators to knowledge use were examined. One of the challenges was how to spread and scale the toolkit for a virtual audience. Workshops and presentations were facilitated by our partner organizations. We received valuable feedback at the end of each workshop, ranging from gratitude that the toolkit existed to more practical suggestions such as adding closed captioning to the introductory video and ensuring the platform is mobile-friendly. When education workers are feeling overworked, underappreciated, and feelings of burnout start to surface, how helpful is a toolkit? Workshop participants mentioned that looking at many resources in a toolkit may be overwhelming to navigate. Reflecting on this feedback, the team included an instructional video to guide users through the toolkit. Additional resources on microaggressions and how to create an anti-racism policy were added to the toolkit after receiving feedback from workshop participants.

Toolkit content: health worker burnout toolkit

During the KTA knowledge creation phase, our team undertook a search of interventions in both the public and private sectors across countries dated between 2018 and 2023 that were available in English or French, and ideally open access yielding 48 sources at the system, 48 at the organizational, 36 at the team and 22 at the individual levels. Similar to the HPW toolkit, the team was very selective in choosing individual level interventions that didn’t over-responsibilize workers to increase their resilience to challenging work environments.

During the second phase of the KTA framework, we conducted pre-implementation online surveys and interviews with healthcare workers and leadership teams in the partner organizations (Supplement 4). Across all sites, we found high rates of burnout, particularly work-related burnout, and high rates of presenteeism where staff come to work even when they felt they really should not be at work. Workers expressed the sentiment of feeling particularly disconnected when working remotely. Workload burden, especially considering client complexity, and financial stress related to compensation, especially in light of financial constraints were themes that arose during interviews. In considering any intervention or set of interventions, healthcare workers wanted to be heard, respected, and valued, a strong theme which came through in the focus groups conducted.

Following this feedback, several additional interventions were added to the health worker burnout toolkit. For example, a desire to do more advocacy was brought up during a site meeting and the research team identified a gap in advocacy resources within the toolkit. In response, two advocacy tools were added and shared with the clinical site.

Phase 3 of the action cycle entailed assessing barriers and facilitators to knowledge use. One of the sites noted at the outset the challenge of reviewing the number and varied interventions gathered in the toolkit. This is similar to what we heard in this phase of the HPW Education Workers Toolkit mobilisation.

“Will they come?”

Implementation of health worker burnout toolkit

Phase 4 of the action cycle involved selecting the right implementation strategy that adopted or adapted interventions to address growing health worker burnout. Choosing an intervention and implementing it was a thoughtful process that took time, trust, and a willingness to listen. To respond to the feeling of overwhelm at the number of interventions in the online toolkit, the research team created a shortlist of interventions for consideration handpicked to meet the specific challenges faced by the partner organization informed by the empirical data analysis. We went through the toolkit with the highlighted concerns and chose the top 5–7 interventions we believed may help address the issues at each clinical site. Narrowing the number of interventions can help participants feel less overwhelmed and more willing to move forward in the action cycle.

With one partner organization, the research team took a strengths-based approach when proposing interventions as they were given feedback from leadership that staff were weary of discussing “pain points” without solutions. They opted to cater some of the short-listed interventions to focus on managers as they were identified during interviews as a valuable support to staff that also needed to care for themselves:

“I think our managers [are most in need of mental health interventions]. Yeah, our managers would have been through a lot. Because we see them in meetings, sometimes it's one-on-ones, and they're very professional. They keep everything together. But I do question: who checks in with them, right?”

After presenting the selected interventions, we encouraged sites to customize them and make them their own—not just to adopt but adapt interventions to their setting. One clinical site was drawn to the idea of commensality groups [18] where workers share a meal and build trust, relationships and meaning in work. They decided to rename the intervention to ‘connection circles’ to make it their own. Combining ideas, changing the names or altering content was part of the customization process.

Phase 5 entailed monitoring knowledge use. Across our clinical sites, there was a desire for workplace resources that connected staff and fostered a shared sense of purpose in work. Removing barriers of participation for staff was a crucial consideration. One clinical site created a wellness working committee and compensated staff employees for their time on this committee; this sent a message that wellness was a priority that is valued. Another site had a dedicated HR coordinator who was passionate, positive and kept everyone organized and on task by sending meeting reminders, taking notes, and drafting an agenda for each meeting. The HR coordinator acted as a well-being champion and helped to inspire others within the organization which helped maintain momentum. A clinical leader at one site noticed no part-time staff signed up for a particular intervention. In response, they provided additional information about the purpose of the intervention, and the deadline for part-time staff to register was extended.

Readiness for change was another consistent theme during the implementation process. There were multiple levels of readiness including organizational, unit and individual readiness, and varying levels of engagement across the sites. One of the challenges encountered in one of our sites was repeated negative comments and feedback from one individual worker which started becoming cyclical during monthly meetings. This individual often presented their expressed concerns as negative feedback from other colleagues that they were asked to convey on their behalf. To anticipate the potential ramifications of this negativity, our team provided tools to help the individual respond to any resistance coming from others. Given that there will always be those who do not agree with or object to changes, we found it valuable to shift the focus to what is working well. After nearly a year into the intervention, this individual became a champion for the project after participating in mental health initiatives at the site.

Leadership involvement played a key role and their commitment and readiness for change affected workers’ willingness to engage and invest in the process. The Wellness Working Committee were heavily involved in Phase 4 of the KTA framework. The Wellness Working Committee took the initiative and spent the time to research and understand the short list of interventions so they could confidently share what they felt was valuable to the organization. The well-being champion from one site shared the importance of approaching this process with an appreciative inquiry lens [19], a strengths-based approach to change that focuses on existing assets [20]. Maintaining a positive outlook and recognizing little wins was key. She shared,

“As a social worker I have learned when even the best group initiatives are offered numbers are often still low. If you find that even one staff member joins in, let's consider it a success, you’re truly helping someone feel better.”

We also wanted employees to recognize that creating a Wellness Working Committee is an intervention unto itself.

Phase 6 of the action cycle entails evaluating outcomes, a process we are presently undertaking. Follow up surveys and interviews are near completion in two of the partner sites with strong participation. Although there were no notable differences in burnout, stress and presenteeism measures from the aggregated surveys submitted so far, there remained a sense of momentum with plans to continue wellness initiatives into the future to embed in organizational culture.

Discussion

Addressing mental health in the workplace requires a multifaceted approach [8, 21, 22]. Toolkits are a means by which to assemble these different approaches in a user-friendly format, but their merit is primarily in their utilization and application [23]. We learned that toolkits are optimized when they are empirically based and embed consideration for different users. Application and implementation of toolkit elements for some users are enhanced when targeted to specific organizational needs and when trusted relationships between research teams and partner organizations are developed. Right-sizing interventions is an important consideration. The availability of too many resources may have the unintended impact of activating stress for those experiencing high levels of burnout if we do not consider team, organization, and system-level factors and influences more broadly. Once organizations identified their main concerns (e.g. burnout, presenteeism, disconnect) they were then able to make informed choices about how or which resources might address these concerns. Choosing appropriate interventions can be informed by the KTA framework where staff decide what resonates with their concerns and how interventions could be tailored to meet their specific needs. While the research team provided a short list of interventions, ultimately staff were given the time and space to decide which interventions were chosen. The power of decision making should rest with the staff who will be implementing and impacted by the interventions. After intervention implementation, organizations can evaluate and determine whether an intervention is working and can pivot as necessary. Organizations must also prioritize and pace interventions based on the bandwidth their employees have to engage. When a disconnect between leadership and frontline workers develops (as it pertains to prioritizing and pace), change implementation often fails and exacerbates worker burnout [9].

The context of each workplace is also important to consider before engaging in mental health initiatives [24]. It is unreasonable to ask employees to engage in additional work without compensation. It is also a profoundly gendered issue as female professions are disproportionately asked to engage in this kind of invisible labour [17]. Individual worker and organizational readiness are critical and can depend on those in leadership positions to enable collective action for change [25, 26]. Leaders can propose ideas, but workers need to feel part of the process and valued as change partners. All participants in change management must also be attuned to change fatigue [9]. Workers who experience change fatigue can be overwhelmed by feelings of stress, exhaustion and burnout fuelled by feelings of ambivalence and powerlessness associated with ongoing change in the workplace [9]. Change fatigue was exacerbated during the Covid-19 pandemic, especially in professions such as teaching and healthcare (the foci of our toolkit interventions), as rapid and continuous changes were made in response to evolving pandemic trajectories and subsequent municipal, provincial and national responses.

Building a toolkit is an important step, however, the engagement process and relationships that were fostered between the research team and each partner organization are ultimately what brought each toolkit to life and create sustainability beyond the collaboration. In the absence of this kind of opportunity, which was not part of the HPW Education Worker protocol, leaders are well-positioned to evaluate their organization’s capacity for change. The value add for us is listening to the needs of each site and being a support to help them attain their goals as they identify their champions and become empowered to continue this work. We are continuing to engage with partners with whom we co-created the toolkit, toolkit elements, and adopted/adapted initiatives based on these interventions. We hope to empower each partner site by focusing on small positive changes that can have a ripple effect among staff teams. There remains optimism that wellness initiatives will become part of the normal work cycle and partner sites will continue this work beyond our involvement. The seed of change has been planted and now it must be nurtured until growth can be sustained. Next steps are to spread and scale the lessons learned so that other organizations/leaders can foster improved mental health in their workplaces.

There are limitations we experienced across our two studies, some of which provided important feedback. As noted earlier, the protocol for the HPW education worker study did not include an evaluation of the toolkit, thus the insights from these phases of the KTA process are derived from only one study. Limitations experienced in the HWB project included variability in levels of engagement in the KTA cycle; more time would have benefited clinical sites that were slow to implement during the implementation stage. Another limitation of our research is sustainability and financial constraints. The support provided to organizations only lasts the duration of the funding period which speaks to the importance of empowering workers to continue the work beyond our involvement. Caution is needed when making broad conclusions based on our observations with clinical sites. Each organization is unique and mental health initiatives should be tailored to the specific demographic utilizing them. Learning from our experiences with the toolkits presented in this paper, future research should assess organizational and individual worker and leader readiness before engaging in mental health initiatives and work towards developing meaningful relationships with workers to implement and evaluate resources that have the potential to improve work culture.

Conclusions

Practical considerations have emerged from the process of toolkit development and implementation with collaborating partner organizations. Ultimately, relationships between the research team and partner organizations and feedback from user engagement are what brought to life these toolkits to address workplace mental health. It is critical to ground toolkits in the experiential evidence of workplace mental health as is linking these to evidence-informed interventions that correspond to workplace concerns. Toolkit users both have different roles and approach resources in different ways—with some appreciating the opportunity to review on their own whereas others appreciate the effort to tailor to the needs of their organization based on local empirical data. Readiness of organizations to adopt and adapt resources and implement changes is an important consideration. Creating additional, wider reaching toolkits is feasible when interventions are tailored for the organizational context. The gap between evidence and practice can be closed when champions are identified, readiness is assessed, and interventions are adapted and adopted.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 1: Supplementary Doc 1 – HPW interview guide.

Supplementary Material 2: Supplementary Doc 2 – HWB interview guide.

Supplementary Material 3: Supplementary Data 3 – Healthy professional worker partnership: education workers case study survey findings.

Supplementary Material 4: Supplementary Doc 4 – HWB survey.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Magda Baczkowska for helping the research team search and curate resources for the HWB toolkit. Thank you to Alvin Law for transferring the information, creating an online version, and maintaining the HPW and the HWB toolkits.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Abbreviations

- HPW

Healthy Professional Worker

- HWB

Health Worker Burnout

- CIHR

Canadian Institute of Health Research

- MHCC

Mental Health Commission of Canada

- KTA

Knowledge to Action Framework

Authors’ contributions

MC worked across both toolkits and developed the themes that influenced toolkit usage and engagement; she was the lead contributor in writing the manuscript. SM contributed to the background section and worked with MC to incorporate the knowledge to action framework throughout the methods section. IB and JA contributed greatly to the design of the HPW and HWB toolkit component of the studies. IB made a great contribution to the overall structure of the paper. IB, MC, JA, SM, HB, CB, EN, KS, KM, SP reviewed the manuscript. All authors read, revised, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The Healthy Professional Worker Partnership was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grant #159072 and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Grant # 895–2018–4014.

The Health Worker Burnout Toolkit was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, as part of the Operating Grant Studying the Global Impact of COVID-19 on health. Grant # 478269.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current studies are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics board approval for the overall project was received by the University of Ottawa Research Ethics Board (S-05–19–2508—REG-2508 -) and research ethics boards of 16 other participating universities affiliated with team members across Canada. Our research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Each HPW and HWB survey participant provided informed consent to participate before they started the survey.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mental Health Commission of Canada. National Standard. 2024. https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/national-standard/. Accessed 25 June 2024.

- 2.Centre of Expertise on Mental Health in the Workplace. 2024. https://www.canada.ca/en/government/publicservice/wellness-inclusion-diversity-public-service/health-wellness-public-servants/mental-health-workplace.html. Accessed 30 May 2024.

- 3.Mental Health Commission of Canada. Home. 2024. https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/. Accessed 30 May 2024.

- 4.Department for Work and Pensions, Department of Health and Social Care. GOV.UK. 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/ai-to-help-keep-people-in-work-through-15-million-investment-in-occupational-health. Accessed 28 May 2024.

- 5.Robinson M, Tilford S, Branney P, Kinsella K. Championing mental health at work: emerging practice from innovative projects in the UK. Health Promot Int. 2014. 10.1093/heapro/das074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2022. https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/priorities/workplace-well-being/index.html. Accessed 28 May 2024.

- 7.Corbiere M, Shen J, Rouleau M, Dewa C. A systematic review of preventive interventions regarding mental health issues in organizations. Work. 2009;33:81–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akoo C, McMillan K, Price S, Ingraham K, Ayoub A, Rolle Sands S, Shankland M, Bourgeault I. I feel broken": chronicling burnout, mental health, and the limits of individual resilience in nursing. Nurs Inq. 2024. 10.1111/nin.12609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMillan K, Perron A. Change fatigue in nurses: a qualitative study. J Adv Nurs. 2020. 10.1111/jan.14454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egan M, Bambra C, Thomas S, Petticrew M, Whitehead M, Thomson H. The psychosocial and health effects of workplace reorganisation: a systematic review of organisational-level interventions that aim to increase employee control. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2007;61:945–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Government of South Australia: Glossary. 2024. https://dhs.sa.gov.au/about-us/open-government/internal-policies/diversity-and-inclusion/diversity-access-and-inclusion-plans/2020-to-2024/2023-Addition/glossary. Accessed 08 Aug 2024.

- 12.Lelliott P, Tulloch S, Boardman J, Harvey S, Henderson M, Knapp M. Mental health and work. London: London Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2008.

- 13.Healthy Professional Worker Partnership. University of Ottawa. 2024. https://www.healthyprofwork.com/. Accessed 25 June 2024.

- 14.Health Worker Burnout Toolkit. University of Ottawa. 2024. https://www.mhcaretoolkit.ca/burnout-toolkit. Accessed 24 June 2024.

- 15.Graham I, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, Robinson N. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006. 10.1002/chp.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tulk C, Ferguson K, Corrente M, Rodger S, Bourgeault I. Healthy professional worker partnership: education workers case study survey findings. Healthy Professional worker partnership. 2024. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5d7bbcde8eb7a65a6fd614ab/t/6567b523ad74590e8d83352f/1701295396691/HPW+Education+Workers+Report+FINAL.pdf. Accessed 10 Aug 2024.

- 17.Bourgeault IL, Atanackovic J, McMillan K, Akuamoah-Boateng H, Simkin S. The pathway from mental health, leaves of absence, and return to work of health professionals: gender and leadership matter. Healthcare Management Forum. 2022: 10.1177/08404704221092953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Stanford Medicine. Commensality Groups. 2024. https://wellmd.stanford.edu/innovations-and-progress/commensality-groups.html. Accessed 24 June 2024.

- 19.Coopperrider DL, Whitney D. A positive revolution in change. In: Cooperrider DL, Sorenson P, Whitney D, Yeager T, editors. Appreciative inquiry: an emerging direction for organization development. Champaign: Stipes; 2001. p. 9–29. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kristman VL, Lowey J, Fraser L. A multi-faceted community intervention is associated with knowledge and standards of workplace mental health: the Superior Mental Wellness @ Work study. BMC Public Health. 2019. 10.1186/s12889-019-6976-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Wu A, Roemer EC, Kent KB, Ballard DW, Goetzel RZ. Organizational best practices supporting mental health in the workplace. J Occup Environ Med. 2021. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Gabutti I, Colizzi C, Sanna T. Assessing organizational readiness to change through a framework applied to hospitals. Public Organiz Rev. 2023: 10.1007/s11115-022-00628-7.

- 23.Thoele K, Ferren M, Moffat L. Development and use of a toolkit to facilitate implementation of an evidence-based intervention: a descriptive case study. Implement Sci Commun. 2020. 10.1186/s43058-020-00081-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Volpe RL, Mohammed S, Hopkins M, Shapiro D, Dellasega C. The negative impact of organizational cynicism on physicians and nurses. Health Care Manag (Frederick). 2014. 10.1097/HCM.0000000000000026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Vaishnavi V, Suresh, M. Assessment of healthcare organizational readiness for change: a fuzzy logic approach. Journal of King Saud University - Engineering Sciences. 2022. 10.1016/j.jksues.2020.09.008.

- 26.Miake-Lye IM, Delevan DM, Ganz DA. Unpacking organizational readiness for change: an updated systematic review and content analysis of assessments. BMC Health Services Research. 2020. 10.1186/s12913-020-4926-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Supplementary Doc 1 – HPW interview guide.

Supplementary Material 2: Supplementary Doc 2 – HWB interview guide.

Supplementary Material 3: Supplementary Data 3 – Healthy professional worker partnership: education workers case study survey findings.

Supplementary Material 4: Supplementary Doc 4 – HWB survey.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current studies are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.