Abstract

Background

To analyze the associations among autonomous motivation, self-efficacy, satisfaction of basic psychological needs, social support and perceived environment with physical activity practice of adolescents aged between 12 and 15 years; and to test autonomous motivations and self-efficacy as potential mediators of the associations between these environmental factors and physical activity practice.

Methods

We evaluated 553 adolescents, that participated in the ActTeens Program. Physical activity was assessed using the Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adolescents. Autonomous motivation, self-efficacy, satisfaction of basic psychological needs, parents’ social support and perceived environment were assessed using specifics questionnaires. Linear regression models were used to test the associations.

Results

Parents’ support (β = 0.32), satisfaction of basic psychological needs of colleagues (β = 0.21) and teachers (β = 0.12), and perceived environment (β = 0.10) had significant associations with physical activity (p < 0.05). The direct effect value was reduced when autonomous motivation was added as a mediator of the association between parents’ support and physical activity (β = 0.24), with a 25% mediated effect. Autonomous motivation was mediator of the relationship between basic psychological needs of colleagues (β = 0.13; EM = 38%), teachers (β = 0.02; EM = 83%), and perceived environment (β = 0.03; EM = 70%) with physical activity.

Conclusion

Self-efficacy was not associated with physical activity and autonomous motivation was an important mediator of adolescents’ physical activity.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40359-024-02055-3.

Keywords: Teenagers, Encouragement, Social support, Neighborhood environment, Mediating factors, Physical education

Background

Regular physical activity (PA) has been associated with numerous health benefits, including improved physical fitness [1], metabolic profile [2], immune system [3] and mental health [4]. Global recommendations on PA advise that children and adolescents should perform an average of 60 min of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) per day [5, 6], and should mainly engage in aerobic activities. In addition, they should engage in muscle and bone strengthening activities at least three times a week.

It is estimated that 81% of school-aged adolescents (11–17 years) do not meet the recommendations for MVPA [7]. In Brazil, only 8.4% are considered physically active [8]. Longitudinal studies have found decreases on PA levels during adolescence [9, 10], considering 13 years of age a critical period, especially for girls [11, 12]. Furthermore, habits acquired during adolescence tend to remain into adulthood [13], and physical inactivity is considered the fourth leading modifiable risk factor for mortality worldwide [14].

In order to develop more effective strategies for promoting PA, researchers have investigated the factors that can influence active behavior in adolescents [12, 15–21]. The main reasons for adolescents to engage in PA are individual factors (enjoyment, self-efficacy, perceived competence, autonomy and autonomous motivation) and environmental factors (social support from parents/colleagues; accessibility and availability of new practice opportunities) [22, 23].

Considering the individual factors for PA practice, the Self-Determination Theory [24] emphasizes the satisfaction of basic psychological needs (BPN) (autonomy, competence and relatedness) as a key driver of autonomous motivation for active behavior. On the other hand, the Social Cognitive Theory [25] highlights self-efficacy as the main motivator of action and a key factor in influencing and maintaining PA levels in adolescents.

Regarding environmental factors, both social (support of parents and colleagues) and physical environment (accessibility and availability of new practice opportunities) have been pointed as important factors in the acquisition of health-related behaviours in children and adolescents [26]. Parental encouragement has been positively associated with adolescents´ PA [27], and the provision of transportation and equipment is associated with increased PA in this population [28]. Systematic reviews addressing the relationship between the perception of the environment and PA practice showed a statistically significant association between better access to sidewalks and increased PA [29]. In addition, perceived availability of PA resources including sports facilities and parks were associated with increased MVPA [30].

Furthermore, systematic reviews have shown that self-efficacy, intention [12, 16, 21], perception of environmental barriers, expectation of results and autonomous motivation [21] are considered the main mediators in the acquisition of healthy behaviors in adolescents. Self-efficacy, in particular, can significantly increase intention and adherence to MVPA compared to other mediators [15, 19].

Due to the circumstances imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic [31, 32], which has led to a decline in PA practice [33], as well as psychological and emotional damage [34], it is necessary to confirm the determinants of PA in adolescents in order to develop behavior changes strategies. Thus, mediation analyses studies can provide a better understanding of the pathways that influence adolescents to be physically active, helping to understand whether changes in behavior occur due to a direct effect or due to influences from external factors [35].

The health benefits of PA are well established, but there is no point in continuing to seek more benefits if we are unable to get adolescents to adopt an active lifestyle [36]. Thus, it is important to identify these factors in low-and middle-income countries with their specific sociodemographic and culture characteristics [37]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to analyze the associations of autonomous motivation, self-efficacy, satisfaction of basic psychological needs (BPN), parents support and perceived environment with PA practice of adolescents aged between 12 and 15 years, and to test autonomous motivation and self-efficacy as potential mediators of the associations between these environmental factors and PA. Our initial hypothesis points out that self-efficacy and autonomous motivation are mediators, indirectly influencing the associations between satisfaction of BPN, parents support and perceived environment with PA practice of adolescents.

Methods

Participants and study design

This cross-sectional study was developed with baseline data from the ACTTEENS Program, a school-based intervention aimed to improve the PA level, health-related fitness, cardiometabolic and mental health in adolescents [38]. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the State University of Northern of Parana, Brazil (no 4.452.513).

The secondary public schools in City, Brazil, including students from 12 to 15 years old (i.e., Grades 8th and 9th ) were eligible to participate of the study. The schools were recruited through a list provided by the Regional Education Center. Then, emails were sent directly to eligible schools. Since the schools had expressed interest in the study, a member of the research team met with the school agent and explained the study requirements. Inclusion criteria for the schools were: being secondary level and having at least one class in 8th and 9th grades, and Physical Education classes two times a week. Six schools were considered eligible, and four agreed to participate. Parental/guardians signed informed written consent was obtained from students prior to participation. Students with disabilities were not included.

Data collection

All assessments were conducted in the school by trained staffs. Self-report measures were assessed before physical assessment. Anthropometric assessments were conducted by same-sex researcher staff. The data collection period was carried in March to June 2022. Data collection was performed during Physical Education classes. After completing the questionnaires, students were conducted to a private room for anthropometric assessment.

Anthropometric assessments

Measurements of weight (kg) and height (cm) followed a standardized process and were performed by qualified staff. The weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a standardized scale, and height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a stadiometer (Welmy®, São Paulo, Brazil). BMI was calculated by the equation BMI = weight (kg) / height (m2).

Physical activity

PA was assessed using the “Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adolescents” (PAQ-A), translated and validated for Brazilian adolescents by [39]. The PAQ-A is a self-administered, 7-day recall questionnaire, that assesses participation in different PA (during Physical Education classes, lunch break, after school, in the evenings and at weekends). Each of the 8 questionnaire items is scored between low (1) to high (5), and a mean score of all items constitutes the overall score, being the higher scores represents the more active adolescents. The PAQ-A presents a Sperman correlation moderate with total PA (rho = 0.56) and high to MVPA (rho = 0.63) measured by accelerometer [40].

Autonomous motivation

The “Behavioral Regulations in Exercise Questionnaire” [41] was used to assess autonomous motivation for PA. This questionnaire consists of 2-subscales: identified and intrinsic regulations for the practice of PA. Response options are on a 5-point scale, ranging from strongly disagree (0) to strongly agree (4), used to rate each of its 6 items with the generation of score based on mean across items. The highest values were for adolescents more motivated.

Self-efficacy, parents’ support and perceived environment

Self-efficacy, parents’ support and perceived environment were evaluated using the questionnaire “Scales on Intrapersonal, Interpersonal and Environmental Factors Associated with PA” [42]. This questionnaire measures six scales PA-related: attitude, self-efficacy, parental, teachers and friends’ support, and perceived neighborhood environment. For this study, we used only the following scales: self-efficacy, parental support, and perceived neighborhood environment. The questions and scales were previously validated among Brazilian adolescents and presented satisfactory psychometric indicators (i.e. construct validity, internal consistency and reliability) [42].

The self-efficacy scale had eight items assessing confidence in participating in PA in the presence of barriers (feeling lazy, not having a partner, unmotivated, not having a skill). Response options ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4). Social support of parents for the PA scale had by six items that assess adolescents’ perceptions of the frequency with which their parents stimulate PA practice (i.e. transport, playing together, and talking about). Response options ranging from never (1) to always (4). The perceived environment for the practice of PA scale have seven items, and assess adolescents´ perceptions of PA-related attributes (i.e., security, infrastructure, and access and attractiveness related to PA) in the neighborhoods where they lived. Response options ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4). For each scale, the average of the questions were calculated, where higher score is better [42].

Basic psychological needs satisfaction

The “Adolescent Psychological Need Support in Exercise Questionnaire” was used to evaluate colleagues´ and teachers’ support for the PA [43]. The evaluation of this instrument requires satisfaction during exercise across the three-item: autonomy support, relatedness support, and competence support. Participants reported their satisfaction using a 5-point scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5), used to rate each of its 7 items with the generation of score based on mean across items. The highest values were for adolescents with better satisfaction of BPN.

Statistical analyses

Means and standard deviations or median and inter-quartile range were used to describe the participants´ characteristic. Normality of continuous variables was checked, and to compare the variables between the sexes, the Student or Mann-Whitney tests were used. Linear regression models were used to test the association of individual and environmental factors (autonomous motivation, self-efficacy, social support of parents, BPN satisfaction, and perceived environment) with PA.

Since the self-efficacy was not significantly associated to the PA (p > 0.05), we created four models for the mediation analyses including just the autonomous motivation as a mediator: model 1 tested as a predictor the social support of parents; model 2 tested as a predictor the BPN satisfaction of teacher; model 3 tested as a predictor the BPN satisfaction of colleagues; and model 4 tested as a predictor the perceived environment. To test these four models of interest, ordinary least squares (OLS) regression was used. All assumptions of OLS were tested and satisfied. Confidence intervals for model effects were constructed using percentile bootstrapping (5,000 bootstrapped samples). Analyses of statistical mediation were conducted using the PROCESS macro in SPSS 25.0, adopting p < 0.05 for statistical significance.

The mediation effects were tested in accordance to [44] procedures: a) independent variable be significantly associated to the dependent variable (path C); b) independent variable be significantly associated to the mediator variable (path a); c) mediator variable be significantly associated to the dependent variable (path b); and d) association between the independent variable and dependent variable has been reduced by the mediator variable (path C’). Coefficients were calculated to determine the indirect effect of mediation (path a * path b). To estimate the mediation proportion (MP) was used the equation MP = C`/C. The mediated effect (ME) was calculated by [ME = (1 - MP) * 100] [45].

Results

This study evaluated 617 adolescents, 64 were excluded from the analysis for not meeting the exclusion criteria, resulting in a final sample of 553 students (53.1% female and 53.3% enrolled in the 8th grade) in additional file 1. Boys were more physically active than girls in Table 1. Significant differences were found between sexes for autonomous motivation, colleagues’ BPN satisfaction, parent support, self-efficacy and perceived environment in Table 2.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Boys | Girls | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 13.6 ± 0.7 | 13.5 ± 0.6* | 13.6 ± 0.6 |

| Weight (kg) | 58.4 ± 16.2 | 55.7 ± 15.5* | 57.0 ± 15.9 |

| Height (m) | 1.65 ± 0.08 | 1.59 ± 0.06* | 1.62 ± 0.07 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 21.1 ± 4.8 | 21.8 ± 5.5 | 21.5 ± 5.2 |

| Physical activity (score) | 2.4 ± 0.7 | 2.1 ± 0.6* | 2.2 ± 0.7 |

Note. * p < 0.05. Values in mean and standard deviation. kg – Kilograms. m – Meters

Table 2.

Scores of psychosocial variables hypothesized as mediators

| Psychosocial factors | Boys M (IQ) | Girls M (IQ) | Total M (IQ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomous motivation | 2.8 (2.0; 3.5) | 2.5 (2.0; 3.1)* | 2.6 (2.0; 3.3) |

| Colleagues’ BPN | 3.3 (2.5; 4.2) | 3.0 (2.2; 3.8)* | 3.1 (2.3; 4.0) |

| Teacher’s BPN | 3.5 (2.8; 4.5) | 3.5 (2.6; 4.5) | 3.5 (2.6; 4.5) |

| Parents’ support | 2.1 (1.5; 2.8) | 1.8 (1.3; 2.5)* | 2.0 (1.3; 2.6) |

| Self-efficacy | 2.3 (2.0; 2.8) | 2.5 (2.0; 2.8)* | 2.5 (2.0; 2.8) |

| Perceived environment | 2.0 (1.4; 2.4) | 2.1 (1.7; 2.4)* | 2.1 (1.7; 2.4) |

Note. Mann-Whitney test. * Significant difference between sexes - p < 0.05. M – Median. IQ – Interquartile. BPN – Basic Psychological Needs

No statistically significant associations were observed between self-efficacy and PA for both sexes, and the perceived environment was not associated with PA for girls in Table 3, which led to their exclusions from the mediation models.

Table 3.

Association between psychosocial variables and physical activity

| Boys β (R²) | Girls β (R²) | Total β (R²) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomous motivation | 0.29* (12%) | 0.21* (9%) | 0.26* (12%) |

| Colleagues’ BPN | 0.21* (11%) | 0.18* (10%) | 0.21* (11%) |

| Teacher’s BPN | 0.11* (3%) | 0.13* (6%) | 0.12* (4%) |

| Self-efficacy | -0.02 (0%) | -0.08 (0%) | -0.07 (0%) |

| Parents’ support | 0.24* (6%) | 0.34* (18%) | 0.32* (13%) |

| Perceived environment | 0.15* (1%) | 0.10 (0%) | 0.10* (0%) |

Note. * p < 0.05. BPN – Basic Psychological Needs

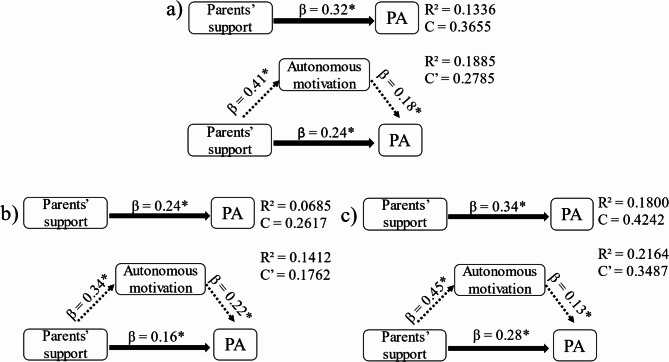

In the simple-mediation analyses, the direct effect of parental support on PA and the indirect effect through autonomous motivation can be observed in Fig. 1. In the general analysis, autonomous motivation mediated 25% (indirect effect β = 0.07; 95% CI = 0.04; 0.11) of the associations between parental support with adolecents’ PA. For boys and girls, the mediated effects were 33% (β = 0.07; 95% CI = 0.03; 0.12) and 18% (β = 0.06; 95% CI = 0.02; 0.10), respectively.

Fig. 1.

Mediation diagram between parent support and physical activity, mediated by autonomous motivation. *p < 0.05. a) – Total analysis. b) - Male. c) - Female. PA – Physical Activity. C – Total effect. C’ – Direct effect

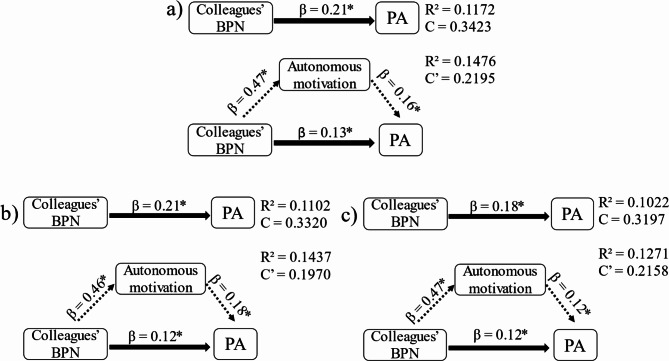

Analyzing the autonomous motivation as mediator of the associations between colleagues’ BPN and PA in Fig. 2, there was mediation of 38% in the general analysis (β = 0.07; 95% CI = 0.04; 0.11). When stratified by sexes, the mediated effects were 43% for boys (β = 0.08; 95% CI = 0.02; 0.15) and 33% for girls (β = 0.06; 95% CI = 0.01; 0.10).

Fig. 2.

Mediation diagram between colleagues’ basic psychological needs and physical activity, mediated by autonomous motivation. *p < 0.05. a) – Total analysis. b) - Male. c) - Female. BPN – Basic Psychological Needs. PA – Physical Activity. C – Total effect. C’ – Direct effect

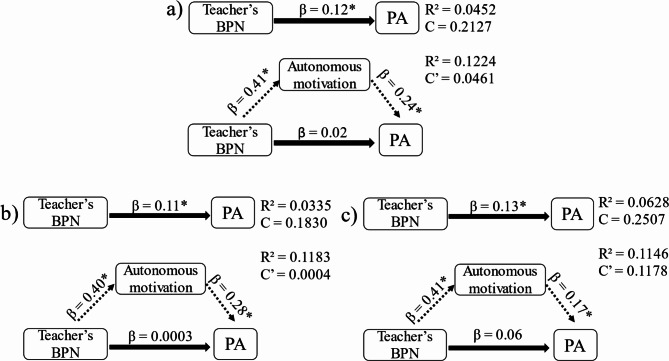

In the association between the Physical Education teacher’s BPN satisfaction and PA in Fig. 3, there was a complete mediation effect (β = 0.10; 95% CI = 0.06; 0.13). The autonomous motivation mediated about 83% of the association. When analyzed by sex, the mediated effect was 100% for boys (β = 0.11; 95% CI = 0.06; 0.17) and 54% for girls (β = 0.07; 95% CI = 0.03; 0.11).

Fig. 3.

Mediation diagram between teacher’s basic psychological needs and physical activity, mediated by autonomous motivation. *p < 0.05. a) Total analysis. b) Male. c) Female. BPN – Basic Psychological Needs. PA – Physical Activity. C – Total effect. C’ – Direct effect

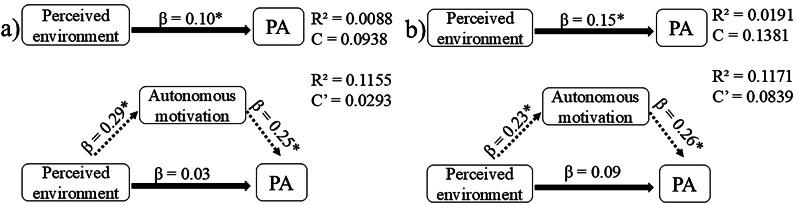

Similar associations were observed between perceived environment and PA in Fig. 4, with a complete mediation effect. In the total analysis, autonomous motivation mediated 70% of the association (β = 0.07; 95% CI = 0.03; 0.11). For the boys, the mediated effect was 40% (β = 0.06; 95% CI = 0.01; 0.11).

Fig. 4.

Mediation diagram between perceived environment and physical activity, mediated by autonomous motivation. *p < 0.05. a) – Total analysis. b) - Male. PA – Physical Activity. C – Total effect. C’ – Direct effect

Discussion

The current study aimed to analyze the associations of parents’ support, satisfaction of BPN and perceived environment with PA practice in adolescents, and to test autonomous motivations and self-efficacy as potential mediators of these associations. We found significant associations between the parents’ support, BPN` satisfaction by colleagues and teachers` physical education, and perceived environment with PA. In the simple-mediation analyses, only autonomous motivation mediated the associations between these environmental factors and PA.

The healthy lifestyle in youth may be influenced by external factors, such as home environment [46]. Parents’ support for PA practice occurs through different contexts, which includes verbal (e.g. incentives, watching, praise) and nonverbal (e.g. models and transportation) encouragement. In accordance with our results, a systematic review performed by [47] reported significant positive association between social support and PA, in line with several studies [27, 28, 48, 49].

In the current research, autonomous motivation mediated the association between parents’ support and PA in both sexes, corroborating the findings by [50]. Even if parents are not physically active, there are others types of parental support such as watching/supervision and encouragement that can motivate and promote the involvement of their child in PA [51]. In this context, this type of support provided by parents can prompt autonomy of adolescents [52], which influences autonomous motivation and this directly affects engagement in PA [53].

Analyzing the BNP of colleagues, we observed a significant association with PA, which was mediated by autonomous motivation. Colleagues` support may be considered an important construct for PA, as the most attractive and fun activities in adolescence are related to the participation of colleagues (e.g. team sports or recreational group games) [54, 55]. These conditions (relationship and enjoyable/fun) are positively related with autonomous motivation [56] [57]. evaluated 391 individuals (adolescents and adults), of all variables measured (exercise intention, BPN, sport commitment), only BPN were confirmed to be predictive for exercise adherence. Of the three variables pertaining to the scale BPN, relatedness has the strongest impact on exercise adherence. Such evidence may be explained by the fact that when people feel they belong to a group, they are more likely to join in health behaviours [58].

Regarding the perception of satisfaction of BPN adolescents through the Physical Education teacher, when we included the mediator autonomous motivation, no significant association was found, resulting in a complete mediation effect. Other studies [59, 60] corroborate our findings of the direct effect of this variable on PA by including autonomous motivation as a mediator [61]. suggest that this effect is because in Physical Education classes students need to fulfill activities and expectations defined by the teacher, preventing them from satisfying one of the BPNs (autonomy), thus, as one of the three BPNs is not met, there will be a negative impact [62].

With adolescents, there is an extra challenge in the developmental stage, a sense of autonomy develops and they are resistant to interventions that consider their independence to be impeded [63]. The motivational environment in Physical Education classes, with good perceived social relationships, can be a significant factor for youth to engage in PA [64].

Regarding the perceived environment, it was associated with PA only for boys. According to [65], the perception of the environment depends on individual experiences and personality. The questionnaire in the present study addressed questions about the neighborhood where the adolescents lived regarding the availability of places to practice PA, other people practicing PA, safety/crime, vehicle traffic, aesthetics, and quality of sidewalks.

Systematic reviews conducted addressing the relationship between the perception of the environment and the practice of PA demonstrate that in the majority of studies analyzed (6/10) a statistically significant association was found between better access to sidewalks and increased PA [29], that neighborhood aesthetics do not influence the practice of PA [66], and that analyses at the environmental level of the community (lack of accessibility to facilities and lack of safety in the neighborhood) were those that presented the most barriers to PA, being the facilitators at interpersonal levels [67].

In the present study, when including the autonomous motivation variable as a mediator of perceived environment with PA, the direct effect lost its significance [68]. showed that PA associations with the perception of the environment can be more complex than through direct associations. The systematic review by [69], concluded that there is no evidence that the built environment has a direct relationship with PA when controlling for individual-level factors, emphasizing that there is not enough evidence to evaluate its effect on young people.

In the path diagrams in this investigation, autonomous motivation presented a mediating role in both sexes, with a more significant mediating effect for boys in all models. According to [24] autonomous motivation is considered important for maintaining PA habits, since adolescents tend to continue the behavior if they are more autonomously motivated. Therefore, we suggest that interventions aimed at promoting an increase in adolescents’ daily PA practice should focus on improving autonomous motivation, as well as encouraging the involvement of parents and peers.

According to [36], self-efficacy represents someone’s belief in their ability to successfully perform the actions necessary to satisfy the demands of the situation. Thus, studies have demonstrated significant associations between self-efficacy and PA levels, justifying the importance of improving self-efficacy to increase PA levels in adolescents [46, 70–73]. However, in the present study, self-efficacy did not show a statistically significant association with PA, corroborating previous research [59, 74–76].

Current research becomes important to guide future interventions, which must provide psychologically favorable environments, offer alternatives, and give autonomy in choosing activities for school Physical Education classes, developing activities assisted and guided by the Physical Education teacher, and giving feedback to improve their perceptions of capacity and provide time for them to be more active with their peers, with multi-component strategies based on behavior change theories.

The present study presents important findings, however, we have some limitations that must be highlighted. First, adolescents’ PA was assessed using a self-reported method, which may be subject to memory bias. In addition, the questionnaire offers a score and not the time/intensity of PA. Furthermore, students were returning to face-to-face classes after a pandemic period, this factor in itself can cause psychosocial changes. Furthermore, the present study has a cross-sectional design, making it impossible to point causality.

The fact that there are few studies in South America of mediation analyses on factors that can influence the practice of PA among adolescents, specifically in Brazil, can be considered one strength of our study. An additional strength, the data presents information on when teenagers were returning to their usual routines following restrictions from the Covid-19 pandemic. Finally, adolescents have multiple motives and objectives acting simultaneously, which can influence their choices and behavior.

Conclusion

Given the results found, it is concluded that parental support, BPN satisfaction, and perceived environment were significantly associated with the practice of PA, and the autonomous motivation presented an important mediator of these associations. These results reinforce the literature and provide support for future PA interventions and for school Physical Education teachers, who should focus on autonomous motivation. Thus, we suggest that future studies use objective methods to assess PA, to increase the accuracy of information, and longitudinal studies should confirm whether autonomous motivation mediates changes in adolescents’ PA practice.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors, Géssika Castilho dos Santos (nº 88887.751116/2022-00 - Educational Scholarship – PostDoctoral Research) and Rodrigo de Oliveira Barbosa (nº 8887.7043/2022-00- Educational Scholarship – Master’s student), would also like to acknowledge support by CAPES.This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001. However, the funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Rodrigo de Oliveira Barbosa, Géssika Castilho dos Santos and Antonio Stabelini Neto, methodology, Rodrigo de Oliveira Barbos, Jadson Marcio da Silva, Thaís Maria de Souza Silva and Renan Camargo Correa; formal analysis, Rodrigo de Oliveira Barbos and Géssika Castilho dos Santos; data curation, Jadson Marcio da Silva and Renan Camargo Correa; writing—original draft preparation, Rodrigo de Oliveira Barbosa, Thaís Maria de Souza Silva and Pedro Henrique Garcia Dias; writing—review and editing, Géssika Castilho dos Santos, Jeffer Eidi Sasaki and Antonio Stabelini Neto; project administration Antonio Stabelini Neto. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that there was no funding used in this study.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the State University of Northern of Parana, Brazil (no: 4.452.513). All procedures applied in the research study were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and their literate legal guardian.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Landry BW, Driscoll SW. Physical activity in children and adolescents. PM&R. 2012;4(11):826–32. 10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.09.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen LB, Harro M, Sardinha LB, Froberg K, Ekelund U, Brage S, et al. Physical activity and clustered cardiovascular risk in children: a cross-sectional study (the European Youth Heart Study). Lancet. 2006;368(9532):299–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calcaterra V, Vandoni M, Rossi V, Berardo C, Grazi R, Cordaro E, et al. Use of Physical Activity and Exercise to reduce inflammation in children and adolescents with obesity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(11):6908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eime RM, Young JA, Harvey JT, Charity MJ, Payne WR. A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for adults: informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10(1):135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Who Guidelines on Physical Activity and sedentary Behaviour. Web annex. Geneva: WHO; 2020. pp. 1–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria De Atenção Primária à Saúde. Departamento De Promoção Da Saúde. Guia de atividade física para a população brasileira. 1st ed. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2021. pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: a pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1·6 million participants. Lancet Child Adolesc Heal. 2020;4(1):23–35. 10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30323-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Werneck AO, Oyeyemi AL, Fernandes RA, Romanzini M, Ronque ERV, Cyrino ES, et al. Regional socioeconomic inequalities in physical activity and sedentary behavior among Brazilian adolescents. J Phys Act Heal. 2018;15(5):338–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Dijk ML, Savelberg HHCM, Verboon P, Kirschner PA, De Groot RHM. Decline in physical activity during adolescence is not associated with changes in mental health. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1–9. 10.1186/s12889-016-2983-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.PR Silva P da, Santos, WF dos Faria GéssikaC de, RC Corrêa, Elias RGM, Stabelini Neto A. Tracking Da atividade física em adolescentes entre 2010 e 2014. Rev Bras Cineantropometria E Desempenho Hum. 2018;20(1):64–70. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, Guthold R, Haskell W, Ekelund U. Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):247–57. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60646-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cortis C, Puggina A, Pesce C, Aleksovska K, Buck C, Burns C, et al. Psychological determinants of physical activity across the life course: a DEterminants of DIet and physical ACtivity (DEDIPAC) umbrella systematic literature review. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(8):1–25. 10.1371/journal.pone.0182709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azevedo MR, Araújo CL, da Silva MC, Hallal PC. Tracking of physical activity from adolescence to adulthood: a population-based study. Rev Saude Publica. 2007;41(1):69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Physical Activity - Information Sheet No. 385. World Heal Organ. 2014.

- 15.Wu TY, Pender N. A panel study of physical activity in Taiwanese youth: testing the revised health-promotion model. Fam Community Heal. 2005;28(2):113–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Sluijs EMF, Kriemler S, McMinn AM. The effect of community and family interventions on young people’s physical activity levels: a review of reviews and updated systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(11):914–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Standage M, Gillison FB, Ntoumanis N, Treasure DC. Predicting students’ physical activity and health-related well-being: a prospective cross-domain investigation of motivation across school physical education and exercise settings. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2012;34(1):37–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDavid L, Cox AE, McDonough MH. Need fulfillment and motivation in physical education predict trajectories of change in leisure-time physical activity in early adolescence. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2014;15(5):471–80. 10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.04.006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang L, Zhang Y. An extended version of the theory of planned behaviour: the role of self-efficacy and past behaviour in predicting the physical activity of Chinese adolescents. J Sports Sci. 2015. 10.1080/02640414.2015.1064149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sparks C, Dimmock J, Lonsdale C, Jackson B. Modeling indicators and outcomes of students’ perceived teacher relatedness support in high school physical education. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2016;26:71–82. 10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.06.004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly S, Stephens J, Hoying J, McGovern C, Melnyk BM, Militello L. A systematic review of mediators of physical activity, nutrition, and screen time in adolescents: implications for future research and clinical practice. Nurs Outlook. 2017;65(5):530–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF, Wells JC, Loos RJF, Martin BW. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet. 2012;380(9838):258–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60735-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martins J, Marques A, Sarmento H, Carreiro Da Costa F. Adolescents’ perspectives on the barriers and facilitators of physical activity: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Health Educ Res. 2015;30(5):742–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. 1st ed. Englewood Cliffs (NJ): Pearson; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferreira I, van der Horst K, Wendel-Vos W, Kremers S, van Lenthe FJ, Brug J. Environmental correlates of physical activity in youth - a review and update. Obes Rev. 2007;8(2):129–54. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haidar A, Ranjit N, Archer N, Hoelscher DM. Parental and peer social support is associated with healthier physical activity behaviors in adolescents: a cross-sectional analysis of Texas School Physical Activity and Nutrition (TX SPAN) data. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reimers AK, Schmidt SCE, Yolanda Demetriou, Marzi I, Woll A. Parental and peer support and modelling in relation to domain-specific physical activity participation in boys and girls from Germany. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(10):1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei J, Wu Y, Zheng J, Nie P, Jia P, Wang Y. Neighborhood sidewalk access and childhood obesity. Obes Rev. 2021;22(S1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bucksch J, Kopcakova J, Inchley J, et al. Associations between perceived social and physical environmental variables and physical activity and screen time among adolescents in four European countries. Int J Public Health. 2019;64:83–94. 10.1007/s00038-018-1172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. 2020.

- 32.Aquino EML, Silveira IH, Pescarini JM, Aquino R, de Souza-Filho JA, Rocha ADS, et al. Social distancing measures to control the COVID-19 pandemic: potential impacts and challenges in Brazil. Cienc E Saude Coletiva. 2020;25:2423–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malta DC, Gomes CS, Barros MB, de Lima A, Silva MG, de Cardoso AG et al. M,. A pandemia de COVID-19 e mudanças nos estilos de vida dos adolescentes brasilieros. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2021;24:e210012.

- 34.Szwarcwald CL, Malta DC, Barros MB, de Júnior A, de Romero PRB, de Almeida D. Associations of sociodemographic factors and health behaviors with the emotional well-being of adolescents during the covid-19 pandemic in Brazil. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(11):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilczynska M, Lubans DR, Paolini S, Plotnikoff RC. Mediating effects of the ‘eCoFit’ physical activity intervention for adults at risk of, or diagnosed with, type 2 diabetes. Int J Behav Med. 2019;26(5):512–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McAuley E, Blissmer B. Self-efficacy determinants and consequences of physical activity. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2000;28(2):85–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farias Junior JC, Reis RS, Hallal PC. Physical activity, psychosocial and perceived environmental factors in adolescents from Northeast Brazil. Cad Saúde Pública, Rio Janeiro. 2014;30(5):941–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Stabelini Neto A, Santos GC, Silva JM, Correa RC, Da Mata LBF, Barbosa R, de O, et al. Improving physical activity behaviors, physical fitness, cardiometabolic and mental health in adolescents - ActTeens Program: a protocol for a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(8 August):1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guedes DP, Guedes JERP. Medida Da atividade física em jovens brasileiros: Reprodutibilidade E validade do PAQ-C e do PAQ-A. Rev Bras Med do Esporte. 2015;21(6):425–32. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Janz KF, Lutuchy EM, Wenthe P, Levy SM. Measuring activity in children and adolescents using self-report: PAQ-C and PAQ-A. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(4):767–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Markland D, Tobin V. A modification to the behavioural regulation in exercise questionnaire to include an assessment of amotivation. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2004;26(2):191–6. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barbosa Filho VC, Rech CR, Mota J, Júnior JC, de Lopes F. A da S. Validity and reliability of scales on intrapersonal, interpersonal and environmental factors associated with physical activity in Brazilian secondary students. Rev Bras Cineantropometria e Desempenho Hum. 2016;18(2):207–21.

- 43.Emm-Collison LG, Standage M, Gillison FB. Development and validation of the adolescent psychological need support in Exercise Questionnaire. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in Social Psychological Research. Conceptual, Strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.MacKinnon DP. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis. Handbook of Psychology, Second Edition. New York: Routledge; 2008. 1–488 p.

- 46.van Stralen MM, Yildirim M, Velde ST, Brug J, van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJM. What works in school-based energy balance behaviour interventions and what does not a systematic review of mediating mechanisms. Int J Obes. 2011;35(10):1251–65. 10.1038/ijo.2011.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mendonça G, Cheng LA, Mélo EN, De Farias Júnior JC. Physical activity and social support in adolescents: a systematic review. Health Educ Res. 2014;29(5):822–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanz-Martín D, Ubago-Jiménez JL, Ruiz-Tendero G, Zurita-Ortega F. Moderate-vigorous physical activity, family support, peer support, and screen time: an explanatory model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(23). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Su DLY, Tang TCW, Chung JSK, Lee ASY, Capio CM, Chan DKC. Parental influence on child and adolescent physical activity level: a Meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(24). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Li K, Iannotti RJ, Haynie DL, Perlus JG, Simons-Morton BG. Motivation and planning as mediators of the relation between social support and physical activity among U.S. adolescents: a nationally representative study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11(1):42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beets MW, Cardinal BJ, Alderman BL. Parental social support and the physical activity-related behaviors of youth: a review. Heal Educ Behav. 2010;37(5):621–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang L. Using the self-determination theory to understand Chinese adolescent leisure-time physical activity. Eur J Sport Sci. 2017;17(4):453–61. 10.1080/17461391.2016.1276968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vierling KK, Standage M, Treasure DC. Predicting attitudes and physical activity in an at-risk minority youth sample: a test of self-determination theory. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2007;8(5):795–817. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stanley RM, Boshoff K, Dollman J. A qualitative exploration of the critical window: factors affecting Australian children’s after-school physical activity. J Phys Act Heal. 2013;10(1):33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tesler R, Kolobov T, Ng KW, Shapiro E, Walsh SD, Shuval K, et al. Ethnic disparities in physical activity among adolescents in Israel. Am J Health Behav. 2019;43(2):337–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the role of basic psychological needs in personality and the organization of behavior. In: John OP, Robins RW, Pervin LA, editors. Handbook of personality: theory and research. 3rd ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 654–78. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kang S, Lee K, Kwon S. Basic psychological needs, exercise intention and sport commitment as predictors of recreational sport participants’ exercise adherence. Psychol Heal. 2019. 10.1080/08870446.2019.1699089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dowd AJ, Schmader T, Sylvester BD, Jung ME, Zumbo BD, Martin LJ, et al. Effects of social belonging and task framing on exercise cognitions and behavior. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2014;36(1):80–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Littlecott HJ, Moore GF, Moore L, Murphy S. Psychosocial mediators of change in physical activity in the Welsh national exercise referral scheme: secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kalajas-Tilga H, Koka A, Hein V, Tilga H, Raudsepp L. Motivational processes in physical education and objectively measured physical activity among adolescents. J Sport Heal Sci. 2020;9(5):462–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nogg KA, Vaughn AA, Levy SS, Blashill AJ. Motivation for physical activity among U.S. adolescents: a self-determination theory perspective. Ann Behav Med. 2021;55(2):133–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Feliz de Vargas Viñado J, Herrera Mor EM. Motivación Hacia La Educación Física Y Actividad física habitual en adolescentes. Agora EFyD 26 de diciembre de. 2020;22:187–208. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rose T, Barker M, Jacob C, Morrison L, Lawrence W, Strömmer S, et al. A systematic review of digital interventions for improving the diet and physical activity behaviours of adolescents. J Adolesc Heal. 2017;61(6):669–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kokkonen J, Gråstén A, Quay J, Kokkonen M. Contribution of motivational climates and social competence in physical education on overall physical activity: a self-determination theory approach with a creative physical education twist. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(16):1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brownson RC, Hoehner CM, Day K, Forsyth A, Sallis JF. Measuring physical activity environments: state of the Science. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(4):S99–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Qu P, Luo M, Wu Y, Zhang F, Vos H, Gu X, et al. Association between neighborhood aesthetics and childhood obesity. Obes Rev. 2021;22(S1):1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hu D, Zhou S, Crowley-Mchattan ZJ, Liu Z. Factors that influence participation in physical activity in school-aged children and adolescents: a systematic review from the social ecological model perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(6):1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bracy NL, Millstein RA, Carlson JA, Conway TL, Sallis JF, Saelens BE, et al. Is the relationship between the built environment and physical activity moderated by perceptions of crime and safety? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rhodes RE, Zhang R, Zhang CQ. Direct and Indirect relationships between the built environment and individual-level perceptions of physical activity: a systematic review. Ann Behav Med. 2020;54(7):495–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lubans DR, Foster C, Biddle SJH. A review of mediators of behavior in interventions to promote physical activity among children and adolescents. Prev Med (Baltim). 2008;47(5):463–70. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang T, Ren M, Shen Y, Zhu X, Zhang X, Gao M, et al. The association among social support, self-efficacy, use of mobile apps, and physical activity: structural equation models with mediating effects. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2019;7(9):1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fu Y, Burns RD, Hsu YW, Zhang P, Motivation SP, Activity. Sedentary behavior, and Weight Status in adolescents: a path analysis. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2020;93(1). 10.1080/02701367.2020.1804520. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.Kiyani T, Kayani S, Kayani S, Batool I, Qi S, Biasutti M. Individual, interpersonal, and organizational factors affecting physical activity of school adolescents in Pakistan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(13). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Robbins LB, Wen F, Ling J. Mediators of physical activity Behavior Change in the girls on the move intervention. Nurs Res Pract. 2019;68(4):257–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bacil EDA, Piola TS, da Silva MP, Bozza R, Fantineli E, de Campos W. Correlates of physical activity in adolescents of public schools in Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2020;38:e2018329–2018329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Silva EC, da Barbosa C, Silva AO, PF JM, de Farias Júnior JC. Are Self-Efficacy and Perceived Environmental Characteristics Determinants of Decline in Physical Activity Time? J Phys Act Heal. 2021;18(9):1097–104. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.