Abstract

Background and purpose

Among patients with solid tumors, those with breast cancer (BC) experience the most severe psychological issues, exhibiting a high global prevalence of depression that negatively impacts prognosis. Depression can be easily missed, and clinical markers for its diagnosis are lacking. Therefore, this study in order to investigate the diagnostic markers for BC patients with depression and anxiety and explore the specific changes of metabolism.

Method and results

Thirty-eight BC patients and thirty-six matched healthy controls were included in the study. The anxiety and depression symptoms of the participants were evaluated by the 17-item Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD-17) and Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA). Plasma levels of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and lipocalin-2 (LCN2) were evaluated using enzyme linked immunosorbent assay, and plasma lactate levels and metabolic characteristics were analyzed.

Conclusion

This study revealed that GFAP and LCN2 may be good diagnostic markers for anxiety or depression in patients with BC and that plasma lactate levels are also a good diagnostic marker for anxiety. In addition, specific changes in metabolism in patients with BC were preliminarily explored.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Mood, Metabolism, Diagnosis, Patients

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most prevalent cancer and the primary contributor to cancer-related death in women globally [1]. With its increasing prevalence, BC contributes to 11.7% of all new cancer diagnoses and 6.9% of all cancer-related deaths worldwide, as reported in Global Cancer Statistics 2020 [2].

Depression, which is more common in women, is associated with an increased risk of developing tumors and increased tumor-specific and all-cause mortality [3]. In addition, cancer patients are 20% and 10% more likely to experience depression and anxiety, respectively [4]. Furthermore, the incidence of mood disorders among Chinese cancer patients is approximately 44.63%, which is six to seven times higher than that reported in the general population [5]. Fatigue, sleep disturbance, depression, and cognitive impairment are the most common sequelae in BC patients [6]. Female BC patients have a long-term increased risk of first-time depression [7], one of the most common psychiatric symptoms [8]. A previous study indicated that the occurrence of depression and anxiety among individuals with BC can reach 32.2% and 41.9%, respectively [8, 9]. Increasing evidence suggests that mental health disorders hinder the healing process of BC patients, leading to a decline in physical functioning, reduced quality of life, poor adherence to treatment, and shortened life expectancy [10, 11], which results in additional stress for patients, families and society. Psychological health disorders in BC patients should not be overlooked, but most oncological institutions focus on physical treatment procedures, paying more attention to patients’ vital signs and symptoms, while their psychological distress and mental health are often neglected. Therefore, it is urgent to find diagnostic biomarkers for BC with depression and anxiety in order to alleviate the situation and burden, make a more accurate diagnosis and provide a better treatment plan.

Lipid carrier protein-2 (LCN2, also referred to as neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipid carrier protein (NGAL)) was originally identified as a chaperone in covalent complexes with neutrophil gelatinase, also known as matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) [12, 13]. LCN2 overexpression has been observed in patients with a variety of cancers, including lung cancer [14], pancreatic cancer [15] and BC [14, 16, 17]. Multiple studies have shown that LCN2, a potent bacteriostatic agent involved in iron carrier-mediated iron chelation [18, 19], triggers T-cell apoptosis by reducing intracellular iron levels and that iron transported into the tumor microenvironment supports tumor cell growth and promotes tumor progression [20]. Furthermore, the tumor-promoting activity of LCN2 can be linked to MMP-9, which aids in breaking down the extracellular matrix and fostering the growth of tumor cells. Moreover, LCN2 triggers epithelial‒mesenchymal transition (EMT) [16]. LCN2 is frequently linked to estrogen receptor-negative breast tumors [21] and may promote BC progression by regulating EMT. In particular, LCN2 overexpression in human BC cells leads to an increase in mesenchymal markers such as vimentin and fibronectin, a decrease in the epithelial marker E-calmodulin, and a significant increase in cell movement and invasion [16]. In contrast, silencing LCN2 inhibited cell migration and the mesenchymal phenotype [16]. Studies in human BC cell lines have also confirmed that the overexpression of LCN2 results in enhanced breast tumor growth, increased MMP-9 activity, tumor angiogenesis, and tumor cell proliferation [22]. LCN2 deficiency in a spontaneous model of mammary tumors resulted in a notable delay in the development of mammary tumors [23]. A growing number of studies have also shown that elevated LCN2 levels may be related to depression and anxiety. LCN2 is Required for DSS-Induced Depressive Behaviors, LCN2 shRNA rescued the DSS-induced reduction in the number of dendritic spines [24]. LCN2-null mice presented synaptic impairment in hippocampal long-term potentiation, and display anxious and depressive-like behaviors [25]. The plasma level of LCN2 in depressed patients was significantly higher than that in non-depressed controls. Patients with depression who were in partial remission in the month prior to sampling had lower plasma LCN2 levels compared to patients who met the criteria for major depressive disorders [26]. Hence, LCN2 may be a potential biomarker for BC diagnosis.

Astrocytes play numerous vital roles in the central nervous system and are essential for regulating various aspects of neuronal development, synaptic plasticity, and maintenance of neuronal function [27]. Accumulating evidence strongly suggests that astrocytes are involved in neuropsychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder [28]. Increased serum glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) levels can serve as a potential biomarker for neurologic disease [29]. Increased serum GFAP levels are related to worse outcomes in BC patients with brain metastases and may be a potential marker for diagnosis and prognosis [30]. Present study has demonstrated that plasma GFAP was positively correlated with age in patients from BC [31]. Breast tumors may activate astrocytes in the amygdala and hippocampus [32]. Interestingly, LPS treatment of cultured primary astrocytes increases the expression of cellular A1 markers and the production and secretion of LCN2 [32], a reactive astrocyte marker that is triggered in activated astrocytes in response to neurological disease and induces dose-dependent damage to primary neurons [33]. However, LCN2 is detected only in reactive astrocytes in the neuropathological state, not in normal brain tissue [34–37]. The sensitivity of astrocytes to cytotoxic stimuli is increased by induced LCN2 expression or treatment with the LCN2 protein [38]. Thus, GFAP and LCN2 may be biomarkers for the prognostic assessment of BC patients.

The aim of this study was to examine the plasma concentrations of GFAP and LCN2, as well as their associations with depression and anxiety scale scores, meanwhile explore the specific metabolism changes, in order to identify potential indicators of BC patients with depression and anxiety.

Methods

Study participants

In total, 38 BC patients were enrolled. The study was approved by the local ethics committee and conducted in strict accordance with Good Clinical Practice Guidance and Pragmatic Clinical Trials and the Declaration of Helsinki (HZCH-2024-001). The detailed inclusion criteria for BC patients included female patients between the ages of 20 and 70 years with postoperative BC who were determined to be metastasis-free by ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), bone scan, and/or positron emission tomography (PET)/CT. The exclusion criteria were as follows: comorbidities with other malignancies, neurological disorders, metabolic disorders, or other disorders that could affect drug tolerability or compliance. Additionally, 36 healthy adult women without psychiatric disorders or malignancies were recruited as a control group, all of whom signed an informed consent form.

The BC group included all BC patients, which were categorized into depression and non-depression groups and anxiety and non-anxiety groups according to the 17-item Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD-17) and Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA) scores, respectively. The HAMD-17 and HAMA were used to assess the severity of depression and anxiety, respectively. Two trained and experienced doctors scored independently by two raters by interview and observation. The HAMD-17 and HAMA consist of 17 and 14 items, respectively, with almost five possible responses for each item: none, mild, moderate, severe, and extremely severe, with the score of 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 assigned to each option. Specifically, patients with HAMD-17 scores > 7 were included in the depression group, and those with HAMA scores > 7 were included in the anxiety group [39, 40]. BC-depression and anxiety (BCD) group represents BC patients both HAMD-17 and HAMA scores > 7 while BC-non depression and anxiety (BCND) group refers to BC patients with met both HAMD-17 and HAMA scores < 7.

In addition, when we enrolled the healthy subjects’ symptoms assessment, two professional senior doctors include psychiatrists and breast surgeon as the interviewer judge about the mood and breast healthy from the control subjects.

Sample collection

Blood samples were collected from the participants and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was immediately stored at -80 °C until further use.

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay and lactic acid level measurement

GFAP (AF0825-A, AiFang Biological), LCN2 (AF1983-A, AiFang Biological), and lactic acid (A019-2-1, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute) plasma concentrations were measured following the guidelines provided by the manufacturer.

Plasma metabolomics

The plasma samples were thawed at 4 °C and mixed well. Methanol solution was added, and the samples were vortexed and centrifuged for 10 min (12,000 rpm, 4 °C). The supernatant was concentrated, dried and redissolved for liquid chromatography (LC)-mass spectrometry (MS) detection [41]. LC–MS/MS analyses were performed using an AB Sciex QTRAP® 6500+ (SCIEX, USA) by Kaitaibio Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, China) [42].

Statistical analyses

To determine whether the data conformed to a normal distribution, the Shapiro‒Wilk test was used. The data are expressed as the means ± standard deviations for normally distributed continuous variables or the medians ± interquartile ranges for continuous variables that were not normally distributed. T tests were used to compare normally distributed variables between the two groups. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 9.3.1 (GraphPad Software). Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. The analysis of plasma metabolome data included the use of multivariate statistics, including principal component analysis (PCA), partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA). Prior to multivariate statistical analysis of the metabolomic data, standardization (scaling) of the data was performed. To preserve the original information, the data were downscaled and regressed, followed by screening for differentially abundant metabolites and subsequent analysis.

Results

General and cytokine characteristics of the subjects

In total, 38 female BC patients and 36 healthy female controls were enrolled in the present study.

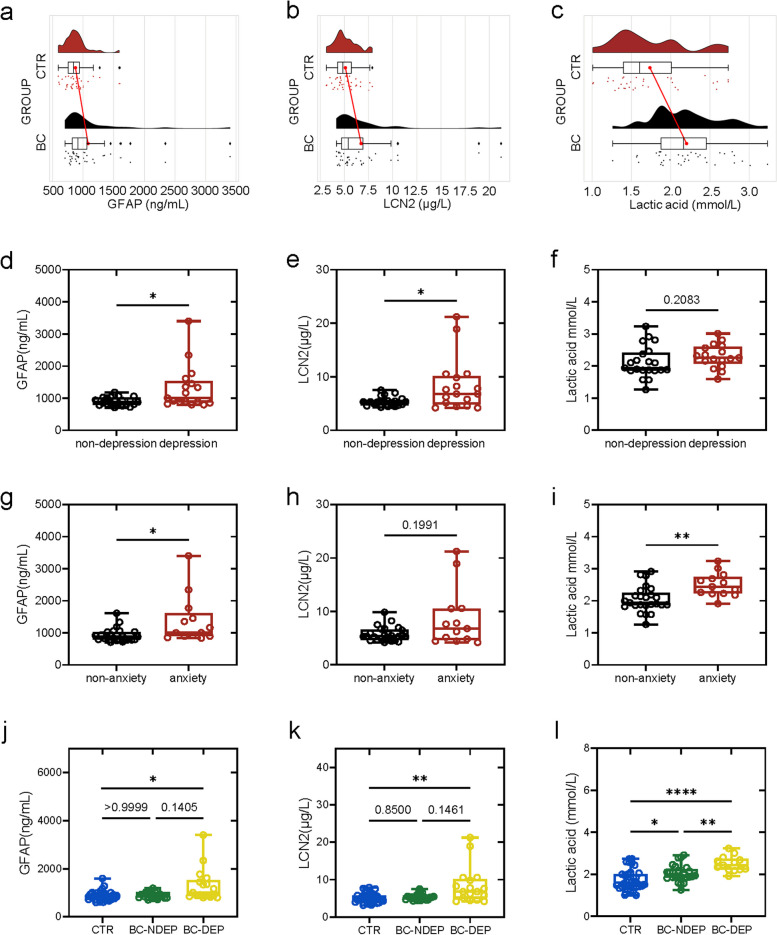

The results indicated that plasma GFAP (916.63 (705.02, 3401.1) ng/mL), LCN2 (5.4044 (4.1880, 21.222) µg/L), and lactic acid (2.1638 (1.2617, 3.2328) mmol/L) levels were increased in BC patients compared with those in CTR subjects (GFAP, 844.09 (594.47, 1594.0) ng/mL; LCN2, 4.8437 (3.1364, 7.8897) ng/mL; and lactic acid, 1.6043 (1.0081, 2.7332) mmol/L) (Fig. 1a-c). In addition, BC group was further divided into non-depression and depression groups, non-anxiety and anxiety groups, the levels of GFAP, LCN2 and lactic acid were compared between them (Fig. 1d-i), respectively. BC patients with depression had higher plasma levels of GFAP (1004.4 (792.06, 3401.1) ng/mL) and LCN2 (6.7877 (4.1880, 21.222) µg/L) than BC patients without depression (GFAP, 877.11 (705.02, 1184.3) ng/mL, p = 0.0328; LCN2, 5.2938 (4.2927, 6.9662) µg/L, p = 0.0286) (Fig. 1d and e). BC patients with anxiety presented elevated GFAP and lactic acid levels compared with BC patients without anxiety (GFAP: BC with anxiety: 1007.7 (834.84, 3401.1) ng/mL; BC without anxiety: 877.11 (705.02, 1611.2) ng/mL, p = 0.0111 (Fig. 1g); lactic acid: BC with anxiety: 2.4400 (1.9107, 3.2328) mmol/L; BC without anxiety: 1.9381 (1.2617, 2.9133) mmol/L, p = 0.0016 (Fig. 1i)). Notably, only BC patients with depressive symptom (BC-DEP) rather than BC patients without depressive symptom (BC-NDEP) presented increased GFAP and LCN2 levels compared with those in CTR (Fig. 1j and k), while lactic acid was elevated in BC-DEP and BC-NDEP patients (Fig. 1l). The detailed demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

The plasma level of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), lipocalin-2 (LCN2) and lactic acid in control (CTR) and breast cancer (BC) patients.(a-c) Changes of plasma GFAP, LCN2 and lactic acid in CTR (n = 36) and BC patients (n = 38). (d-f) Changes of plasma GFAP, LCN2 and lactic acid between BC patients with or without depressive symptom (non-depression: n = 21; depression: n = 17). (g-i) Changes of plasma GFAP, LCN2 and lactic acid between BC patients with or without anxiety symptom (non-anxiety: n = 25; anxiety: n = 13). (j-l) Changes of plasma GFAP, LCN2 and lactic acid among CTR (n = 36) and BC patients with depressive symptom (BC-DEP) or without depressive symptom (BC-NDEP) (non-depression: n = 21; depression: n = 17). Not significant (ns), p ≥ 0.05, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001

Table 1.

Subjects characteristic

| Measure | CTR (N = 36) | BC (N = 38) | t-test | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 47.81 ± 10.88 | 51.71 ± 11.46 | 1.501 | 0.1376 |

| Sex(male/female) | 36 | 38 | / | / |

| HAMD-17 | 2.083 ± 1.381 | 8.974 ± 6.914 | 5.867 | <0.0001 |

| HAMA | 1.861 ± 1.588 | 6.605 ± 6.288 | 4.394 | <0.0001 |

| GFAP (ng/mL) | 844.09 (594.47, 1594.0) | 916.63 (705.02, 3401.1) | 2.296 | 0.0246 |

| LCN2 (µg/L) | 4.8437 (3.1364, 7.8897) | 5.4044 (4.1880, 21.222) | 2.571 | 0.0122 |

| Lactic acid (mmol/L) | 1.6043 (1.0081, 2.7332) | 2.1638 (1.2617, 3.2328) | 4.331 | <0.0001 |

CTR Control, BC Brest cancer, HAMD-17 17-item Hamilton Depression Scale, HAMA Hamilton Anxiety Scale, GFAP Glial fibrillary acidic protein, LCN2 Lipocalin-2

In the BC group, depressive symptoms were significantly positively correlated with the plasma levels of GFAP (rho = 0.61, p < 0.0001; Fig. 2a) and LCN2 (rho = 0.67, p < 0.0001; Fig. 2b), whereas there was no significant correlation between the plasma lactic acid level and HAMD-17 score (rho = 0.27, p = 0.095). We found that the HAMA score was positively correlated with plasma GFAP (rho = 0.62, p < 0.0001; Fig. 2d), LCN2 (rho = 0.61, p < 0.0001; Fig. 2e), and lactic acid (rho = 0.33, p = 0.042; Fig. 2f) levels.

Fig. 2.

Associations between depressive and anxiety symptoms and plasma GFAP, LCN2 and lactic acid levels. (a-c) Association between 17-item Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD-17) scores and plasma GFAP, LCN2 and lactic acid levels. (d-f) Association between Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA) scores and plasma GFAP, LCN2 and lactic acid levels. (g-h) ROC analysis revealed an optimal diagnostic value for plasma GFAP, LCN2 and GFAP + LCN2 levels in BC patients with depressive or anxiety symptoms. (i) ROC analysis revealed an optimal diagnostic value for the plasma lactic acid level in BC patients with anxiety symptoms

In addition, we evaluated the ability of each protein to detect BC with depression or anxiety and BC without depression or anxiety separately using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and the area under the curve (AUC) (Fig. 2g-i). The candidate biomarkers GFAP (AUC 0.728), LCN2 (AUC 0.741), and GFAP + LCN2 (AUC 0.815) could be used to accurately distinguish patients with and without depressive symptoms. ROC analysis revealed the optimal diagnostic values for plasma GFAP, LCN2 and GFAP + LCN2 levels in BC patients with anxiety (AUCs: 0.784, 0.688, and 0.834, respectively). Lactic acid could be used to accurately distinguish patients with and without anxiety (AUC: 0.858); the detailed data are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Cytokines discovered by comparisons and their differential diagnosis ability

| Biomarkers | AUC | 95%CI | p | Youden Index |

Cut-off | Sensitivity | Specificity | AIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | |||||||||

| GFAP | 0.728 | 0.584–0.871 | 0.002 | 0.400 | 1122.229 | 0.471 | 0.930 | / | / |

| LCN2 | 0.741 | 0.577–0.905 | 0.004 | 0.478 | 5.761 | 0.706 | 0.772 | / | / |

| GFAP + LCN2 | 0.815 | 0.683–0.947 | < 0.001 | 0.536 | 0.362 | 0.588 | 0.947 | 56.923 | 61.531 |

| Anxiety | |||||||||

| GFAP | 0.784 | 0.657–0.911 | < 0.001 | 0.435 | 1003.920 | 0.615 | 0.820 | / | / |

| LCN2 | 0.688 | 0.498–0.878 | 0.052 | 0.407 | 6.737 | 0.538 | 0.869 | / | / |

| GFAP + LCN2 | 0.834 | 0.707–0.960 | < 0.001 | 0.594 | 0.190 | 0.692 | 0.902 | 53.388 | 57.996 |

| Lactic acid | 0.858 | 0.771–0.946 | < 0.001 | 0.710 | 2.164 | 0.923 | 0.787 | / | / |

GFAP Glial fibrillary acidic protein, LCN2 Lipocalin-2, AUC Area Under Curve, AIC Akaike information criterion, BIC Bayesian information criterion

Plasma metabolic profiles

We performed an untargeted metabolomics analysis to assess the specific metabolic profiles of BC patients that differ from those of CTR patients. We constructed a volcano map with a fold change threshold of ≥ 2 and p ≤ 0.05. Metabolites in the BCD group were significantly different from those in the CTR group. Differentially abundant metabolites between the two groups are shown in Fig. 3a. Hierarchical clustering analysis (HCA) revealed 24 differentially abundant metabolites in BCD patients compared with HCs. Sixteen metabolites were increased in BCD patients compared with CTR patients, whereas 8 metabolites were decreased in BCD patients (Fig. 3b). Among the differentially abundant metabolites, xanthine, hypoxanthine and 5’-methylthioadenosine were positively correlated with allopurinol. 5-Aminopentanoic acid was negatively correlated with levonorgestrel and hypoxanthine (Fig. 3c). Additionally, we investigated the top metabolites of the plasma metabolome via pathway analysis. According to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database, which is a database project that integrates genome sequence data, molecular networks, and functional orthologs, identified the top 20 metabolites with significant differences between the BCD group and the CTR group were involved in pathways such as the protein digestion and absorption, arginine metabolism, purine metabolism, and proline metabolism pathways, as shown in Fig. 3d and e.

Fig. 3.

Plasma metabolomics analysis between the BCD group and CTR group. (a) Volcano map reflecting the differentially abundant metabolites between the BCD group and CTR group. (b) Heatmap of the relative abundance of differentially abundant metabolites. (c) Differentially abundant metabolite correlation analysis. The color represents the correlation: red represents a positive correlation, blue represents a negative correlation, and the darker the color is, the greater the correlation. (d) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of differentially abundant metabolites. (e) Metabolite and metabolic pathway network diagram. Red indicates that the difference is greater, and blue indicates that the difference is lower

We also detected the differentially abundant metabolites between the BCND group and CTR group (Fig. 4a). HCA identified 30 differentially abundant metabolites between the BCND and CTR groups. Notably, 15 metabolites were increased in BCND patients compared with those in CTR patients, and 15 metabolites were decreased in BCND patients (Fig. 4b). We analyzed the top differentially abundant metabolites via pathway analysis. According to the KEGG database, the top 20 metabolites with significant differences between the two groups were involved in pathways such as retinol metabolism, the intestinal immune network for IgA production, and Th17 cell differentiation, as shown in Fig. 5d and e.

Fig. 4.

Plasma metabolomics analysis between the BCND group and CTR group. (a) Volcano map reflecting the differentially abundant metabolites between the BCND group and CTR group. (b) Heatmap of the relative abundance of differentially abundant metabolites. (c) Differentially abundant metabolite correlation analysis. The color represents the correlation: red represents a positive correlation, blue represents a negative correlation, and the darker the color is, the greater the correlation. (d) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of differentially abundant metabolites. (e) Metabolite and metabolic pathway network diagram. Red indicates that the difference is greater, and blue indicates that the difference is lower

Fig. 5.

Plasma metabolomics analysis between the BCD group and the BCND group. (a) Volcano map reflecting the differentially abundant metabolites between the BCND group and BCD group. (b) Heatmap of the relative abundance of differentially abundant metabolites. (c) Differentially abundant metabolite correlation analysis. The color represents the correlation: red represents a positive correlation, blue represents a negative correlation, and the darker the color is, the greater the correlation. (d) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of differentially abundant metabolites. (e) Metabolite and metabolic pathway network diagram. Red indicates that the difference is greater, and blue indicates that the difference is lower

We also investigated differentially abundant metabolites between the BCD and BCND groups. Nine differentially abundant metabolites could separate BCD and BCND patients in the HCA (Fig. 5a). According to the KEGG database, the top 20 metabolites with significant differences between the BCD group and the BCND group were involved in pathways such as arginine and proline metabolism, protein digestion and absorption and central carbon metabolism in cancer, as shown in Fig. 4d and e.

By identifying plasma-specific metabolites and the related metabolic pathways in BCD, BCND and CTR patients, we found that the metabolite differences were well separated and that the dispersion within each group was small. We used OPLS-DA to visualize the distinct patterns of score plots in both negative and positive modes among the three groups (Fig. 6a and b). These findings indicated that BCD, BCND and CTR individuals have good differential repeatability. Eighteen differentially abundant metabolites were identified among the BCD, BCND and CTR groups. 2-Methoxyestradiol, beta-carotene, and PC (18_3(6Z,9Z,12Z) 18_3(6Z,9Z,12Z)) were increased in the BCD group compared with the CTR and BCND groups (Fig. 6e, f and h). 5-Aminopentanoic acid was significantly lower in the BCD group than in the BCND and CTR groups. KEGG analysis showed that the 5 metabolites with significant changes among the 3 groups were involved in pathways such as protein digestion and absorption, mineral absorption, D-amino acid metabolism, linoleic acid metabolism, and retinol metabolism, as shown in Fig. 6d.

Fig. 6.

Plasma metabolomics analysis among the CTR group, the BCD group and BCND groups.(a-b) Orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) in positive ion mode and negative ion mode for three groups. (c) Z-score map of secondary differential metabolites. (d) KEGG path map. (e-i) Violin diagram of differential metabolites. Not significant (ns), p ≥ 0.05, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001

Discussion

Research has revealed a complex association between BC and depression. Our study validated the increased prevalence of depression among individuals with BC. While previous research has suggested that chronic stress may contribute to the development of BC, the relationship of depression to BC remains inadequately addressed in clinical settings. Our investigation revealed a correlation between GFAP and LCN2 levels and symptoms of depression and anxiety in BC patients, with higher levels observed in patients with both depression and BC than in BC patients without depression. Additionally, lactic acid levels could be linked to anxiety in individuals diagnosed with BC. Moreover, we confirmed the diagnostic efficacy of these markers by employing ROC curve analysis. The findings suggested that these molecules could be effective indicators for comorbid anxiety and depression in patients with BC.

Many studies have reported a strong correlation between LCN2 and BC [43]. LCN2 levels are notably elevated in the more aggressive types of BC, including triple-negative and HER2-positive subtypes. Significant upregulation of LCN2 mRNA was observed in BC tumor tissues [44]. In addition, LCN2 knockout in MMTV-PyMT female mice delayed the appearance of BC and significantly reduced the weight and volume of tumors. These findings indicate that suppressing the LCN2 gene can successfully prevent the excessive growth and dissemination of BC cells and impede the progression of primary cancer in MMTV-PyMT mice [44]. Similarly, there was a notable increase in LCN2 expression in several triple-negative BC cell lines [45], and the growth of TNBC cells was significantly hindered by specific LCN2 antibodies. Wei et al. further demonstrated that LCN2 levels in BC patients were greater than those in healthy controls. LCN2 levels are significantly correlated with leukocyte, neutrophil, monocyte, lymphocyte and platelet counts [17]. These findings suggest that LCN2 may contribute to the progression of BC by initiating inflammatory reactions. Additionally, our results showed elevated levels of LCN2 in BC patients; however, further investigation revealed no significant differences between nondepressed BC patients and healthy controls. Considering the high comorbidity rate of depression in BC patients, LCN2 could be a biomarker for comorbid depression rather than solely indicating the presence of BC. Notably, LCN2 is present in key components of the central nervous system, such as neurons, microglia, and astrocytes. LCN2 regulates various cellular functions and characteristics within the central nervous system, including cell survival, movement, and morphological changes [35, 46]. Granulocyte-produced LCN2 triggers inflammation in astrocytes, leading to bone marrow cell migration into the brain. These findings highlight the crucial role played by LCN2 in triggering neuroinflammation, as evidenced by reduced neuroinflammation when the LCN2 gene is targeted or when bone marrow from LCN2-/- mice is transplanted [46]. According to Wu et al. [47], neuroplasticity and genetic abnormalities influenced by inflammation might significantly contribute to the development of depression. Previous research has also revealed elevated levels of inflammatory markers among individuals with depression. Furthermore, meta-analysis data support significant antidepressant effects associated with several anti-inflammatory drugs [48]. During periods of neuroinflammation in the CNS, microglia and astrocytes release substantial amounts of LCN2. However, excessive LCN2 can also have detrimental effects on the nervous system by compromising the integrity of cells lining the blood vessels, which ultimately leads to neuronal death [33]. In animal models, serum levels of LCN2 were found to be elevated in mice subjected to chronic restraint stress (CRS). Inhibition of the LCN2 pathway in both the peripheral and central regions effectively mitigated the behavioral deficits induced by CRS, suggesting a pivotal role for increased LCN2 in the development of depression [49].

We observed an increase in astrocyte activation and the degeneration marker GFAP in BC patients. GFAP is considered as a biomarker of reactive astrogliosis, and plasma GFAP is related to central inflammation and emotion [50]. Upon further examination, we found comparable outcomes to those of LCN2, with the plasma GFAP level in the nondepressed BC group not significantly greater than that in the CTR group. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that there was more obvious neuroinflammation in the BCD group than in the BCND group, and GFAP may be a good indicator of this neuroinflammation. Furthermore, our findings indicate that the combination of GFAP and LCN2 is a robust biomarker for assessing anxiety and depression in individuals diagnosed with BC. Previous research has consistently demonstrated a significant elevation in serum GFAP levels in BC patients with brain metastases, further highlighting the independent association of GFAP with unfavorable prognosis [30]. However, this study included patients without brain metastases and also demonstrated an increase in GFAP in patients with depression or anxiety. Further research on brain metastases and mental diseases is needed. Combined with our finding that GFAP is specific for predicting the onset of BC with depression or anxiety, repeated measurements of GFAP in the preclinical stages of psychiatric disorders may be more valuable as a diagnostic indicator in future clinical trials. If a reduction in GFAP levels due to antidepressant or antianxiety treatment is clearly associated with a clinically beneficial effect, then future trials for BC patients with psychiatric disorders could use plasma GFAP levels as a potential predictor.

Clinically, elevated levels of the circulating enzyme lactate dehydrogenase have traditionally served as a prognostic indicator in oncology and are typically associated with increased tumor burden and altered cancer metabolism. There is limited evidence regarding the potential impact of circulating lactate levels on the clinical management of individuals with BC. However, some studies have reported cases of hyperlactatemia in patients with BC [51]. This study may be the first to report circulating lactate levels in BC patients. We found that patients with BC had significantly higher levels of circulating lactate than the CTR group did, and patients with anxiety symptoms had higher levels than patients without anxiety symptoms did. We found that, compared with that in the CTR group, the level of circulating lactic acid was significantly greater in patients with BC, and that in patients with anxiety symptoms was greater than that that in patients without anxiety symptoms, indicating that BC patients generally had high levels of lactic acid and that anxiety further aggravated the increase in lactic acid. Typical anxiety symptoms are caused by exercise and appear to be accompanied by a very rapid rise in blood lactic acid [52]. Intravenous lactate administration may cause major anxiety attacks in 93% of anxiety patients and 20% of normal controls that occur within 48 h of dosing [53]. Intravenous sodium lactate infusion has been used to induce anxiety-like responses in rodent models [54]. Consequently, lactic acid can be employed as a diagnostic biomarker for anxiety, exhibiting robust diagnostic accuracy and potential as an anxiety biomarker in individuals diagnosed with BC.

Metabolomics has been extensively applied in clinical settings for disease diagnosis, distinguishing itself from genomics and proteomics by focusing on the end products of cellular metabolic processes. This characteristic makes metabolomics a valuable tool for identifying biomarkers [55]. In this study, metabolomic analysis of plasma from subjects in the three groups was performed; similar to the results of previous studies, there was a clear separation between the three groups, indicating the presence of specific metabolic characteristics in each group. For CTR and BCND patients, our metabolomics results suggest that D-amino acid metabolism is the most important pathway in BC. Emerging evidence suggests that D-amino acids may have implications in the development, therapy, and identification of cancer, despite limited human data and the preliminary stage of research in this field [56]. Retinol metabolism was the principal metabolic pathway in BCD and BCND patients, in which all-trans retinoic acid exhibits prominent alterations. Notably, all-trans retinoic acid enhances the efficacy of suicide gene therapy in the treatment of BC and prevents cancer recurrence induced by cancer stem cells [57, 58]. All-trans retinoic acid can induce the apoptosis and/or differentiation of cells in solid tumors, including BC, and has become a therapeutic tool for this disease [59]. Chronic stress may contribute to the development of BC by reducing the levels of all-trans retinoic acid in patients with depression and anxiety.

Our study has certain limitations. First, the sample size was initially quite limited, as all participants were recruited from a single center. Second, the number of cases used in the metabolomics analysis was small, and the results were not validated in other cohorts. Third, the precise mechanism by which these metabolites are involved in BC remains unknown, and validation in animal models was not performed. Therefore, larger sample sizes from multiple centers are needed to validate our findings, along with additional utilization of animal models for validating the findings of metabolomics studies. Fourthly, due to the number of subtypes varies greatly, we cannot compare the plasma biomarkers (GFAP, LCN2 and etc.) in different subtypes, and in the future study the researchers could focus on it and make depth study. More crucially, the study has its strengths. First of all, as the sample size is small, it is better to calculate the power of the study. In addition, a significant correlation was found between plasma GFAP, LCN2 and lactate levels and the severity of depression and anxiety in the patients, which showed excellent diagnostic ability, may help in the diagnosis and management of the disease.

In conclusion, this study found distinct metabolism changes in BC patients. More importantly, this study demonstrated a correlation between plasma GFAP and LCN2 levels and symptoms of depression and anxiety in BC patients, specifically, the higher levels were observed in those with depression symptoms. Furthermore, the study suggested a potential association between lactic acid and anxiety in BC patients. These insights providing valuable diagnostic markers for identifying BC patients with depression and anxiety.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the support of funds from Health and family planning technology plan general project of Hangzhou (No.A20210395), The medical and health research project of Zhejiang province (No.2023KY964).

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: Jing Lu, Yibo He, Ruzhen Zheng Methodology: Yibo He, Shangping Cheng, Lingrong Yang, Lingyu Ding, Yidan Chen Visualization: Yibo He, Shangping Cheng Funding acquisition: Yibo He, Shangping Cheng, Ruzhen Zheng Supervision: Jing Lu, Yibo He, Ruzhen Zheng Project administration: Yibo He, Shangping Cheng, Lingrong Yang , Lingyu Ding, Yidan Chen Writing – original draft: Yibo He, Shangping Cheng Writing – review & editing: Jing Lu, Ruzhen Zheng.

Funding

acquisition: Yibo He, Shangping Cheng, Ruzhen Zheng.

Supervision: Jing Lu, Yibo He, Ruzhen Zheng.

Project administration: Yibo He, Shangping Cheng, Lingrong Yang, Lingyu Ding, Yidan Chen.

Writing – original draft: Yibo He, Shangping Cheng.

Writing – review & editing: Jing Lu, Ruzhen Zheng.

Data availability

Additional data relevant to the article are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

was granted by the Hangzhou Cancer Hospital ethics committee (HZCH-2024-001). Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants prior to the study. All studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the Data Protection Law and Good Clinical Practice (GCP), as well as other relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

The manuscript does not contain sensitive information of any individual who participated. The participants will provide consent for publication if any identifying information/images are included in the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yibo He and Shangping Cheng contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Jing Lu, Email: lujing2016@zju.edu.cn.

Ruzhen Zheng, Email: zhengruzhen2008@163.com.

References

- 1.Qu F, Wang G, Wen P, Liu X, Zeng X. Knowledge mapping of immunotherapy for breast cancer: a bibliometric analysis from 2013 to 2022. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2024;20(1): 2335728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang YH, Li JQ, Shi JF, Que JY, Liu JJ, Lappin JM, Leung J, Ravindran AV, Chen WQ, Qiao YL, et al. Depression and anxiety in relation to cancer incidence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(7):1487–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, Halton M, Grassi L, Johansen C, Meader N. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(2):160–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ding X, Wu M, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Han Y, Wang G, Xiao G, Teng F, Wang J, Chen J, et al. The prevalence of depression and suicidal ideation among cancer patients in mainland China and its provinces, 1994–2021: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 201 cross-sectional studies. J Affect Disord. 2023;323:482–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bower JE. Behavioral symptoms in patients with breast Cancer and survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(5):768–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suppli NP, Johansen C, Christensen J, Kessing LV, Kroman N, Dalton SO. Increased risk for depression after breast cancer: a nationwide population-based cohort study of associated factors in Denmark, 1998–2011. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(34):3831–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pilevarzadeh M, Amirshahi M, Afsargharehbagh R, Rafiemanesh H, Hashemi SM, Balouchi A. Global prevalence of depression among breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;176(3):519–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hashemi SM, Rafiemanesh H, Aghamohammadi T, Badakhsh M, Amirshahi M, Sari M, Behnamfar N, Roudini K. Prevalence of anxiety among breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer. 2020;27(2):166–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giese-Davis J, Collie K, Rancourt KM, Neri E, Kraemer HC, Spiegel D. Decrease in depression symptoms is associated with longer survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a secondary analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(4):413–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baik SH, Oswald LB, Buscemi J, Buitrago D, Iacobelli F, Perez-Tamayo A, Guitelman J, Penedo FJ, Yanez B. Patterns of Use of Smartphone-based interventions among latina breast Cancer survivors: secondary analysis of a pilot randomized controlled trial. JMIR Cancer. 2020;6(2):e17538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Triebel S, Bläser J, Reinke H, Tschesche H. A 25 kDa alpha 2-microglobulin-related protein is a component of the 125 kDa form of human gelatinase. FEBS Lett. 1992;314(3):386–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kjeldsen L, Johnsen AH, Sengeløv H, Borregaard N. Isolation and primary structure of NGAL, a novel protein associated with human neutrophil gelatinase. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(14):10425–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedl A, Stoesz SP, Buckley P, Gould MN. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in normal and neoplastic human tissues. Cell type-specific pattern of expression. Histochem J. 1999;31(7):433–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomez-Chou SB, Swidnicka-Siergiejko AK, Badi N, Chavez-Tomar M, Lesinski GB, Bekaii-Saab T, Farren MR, Mace TA, Schmidt C, Liu Y, et al. Lipocalin-2 promotes pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by regulating inflammation in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2017;77(10):2647–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang J, Bielenberg DR, Rodig SJ, Doiron R, Clifton MC, Kung AL, Strong RK, Zurakowski D, Moses MA. Lipocalin 2 promotes breast cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(10):3913–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei CT, Tsai IT, Wu CC, Hung WC, Hsuan CF, Yu TH, Hsu CC, Houng JY, Chung FM, Lee YJ, et al. Elevated plasma level of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) in patients with breast cancer. Int J Med Sci. 2021;18(12):2689–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goetz DH, Holmes MA, Borregaard N, Bluhm ME, Raymond KN, Strong RK. The neutrophil lipocalin NGAL is a bacteriostatic agent that interferes with siderophore-mediated iron acquisition. Mol Cell. 2002;10(5):1033–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flo TH, Smith KD, Sato S, Rodriguez DJ, Holmes MA, Strong RK, Akira S, Aderem A. Lipocalin 2 mediates an innate immune response to bacterial infection by sequestrating iron. Nature. 2004;432(7019):917–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Che R, Wang Q, Li M, Shen J, Ji J. Quantitative proteomics of tissue-infiltrating T cells from CRC patients identified Lipocalin-2 induces T-Cell apoptosis and promotes Tumor Cell Proliferation by Iron Efflux. Mol Cell Proteom. 2024;23(1):100691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gruvberger S, Ringnér M, Chen Y, Panavally S, Saal LH, Borg A, Fernö M, Peterson C, Meltzer PS. Estrogen receptor status in breast cancer is associated with remarkably distinct gene expression patterns. Cancer Res. 2001;61(16):5979–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fernández CA, Yan L, Louis G, Yang J, Kutok JL, Moses MA. The matrix metalloproteinase-9/neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin complex plays a role in breast tumor growth and is present in the urine of breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(15):5390–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leng X, Ding T, Lin H, Wang Y, Hu L, Hu J, Feig B, Zhang W, Pusztai L, Symmans WF, et al. Inhibition of lipocalin 2 impairs breast tumorigenesis and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2009;69(22):8579–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Y, Zheng D, Wang H, Zhang S, Zhou Y, Ke X, Chen G. Lipocalin 2 in the paraventricular thalamic nucleus contributes to DSS-induced depressive-like behaviors. Neurosci Bull. 2023;39(8):1263–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferreira AC, Pinto V, Novais SDM, Sousa A, Correia-Neves JC, Sousa M, Palha N, Marques JA. Lipocalin-2 is involved in emotional behaviors and cognitive function. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naudé PJ, Eisel UL, Comijs HC, Groenewold NA, De Deyn PP, Bosker FJ, Luiten PG, den Boer JA. Oude Voshaar RC: Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin: a novel inflammatory marker associated with late-life depression. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75(5):444–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang N, Shen Y, Zhu W, Li C, Liu S, Li H, Wang Y, Wang J, Zhang Q, Sun J, et al. Spatial transcriptomics shows moxibustion promotes hippocampus astrocyte and neuron interaction. Life Sci. 2022;310: 121052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim R, Healey KL, Sepulveda-Orengo MT, Reissner KJ. Astroglial correlates of neuropsychiatric disease: from astrocytopathy to astrogliosis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;87(Pt A):126–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heimfarth L, Passos FRS, Monteiro BS, Araújo AAS, Quintans Júnior LJ, Quintans JSS. Serum glial fibrillary acidic protein is a body fluid biomarker: a valuable prognostic for neurological disease - A systematic review. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022;107:108624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Darlix A, Hirtz C, Mollevi C, Ginestet N, Tiers L, Jacot W, Lehmann S. Serum glial fibrillary acidic protein is a predictor of brain metastases in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2021;149(8):1605–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mandelblatt J, Dage JL, Zhou X, Small BJ, Ahles TA, Ahn J, Artese A, Bethea TN, Breen EC, Carroll JE, et al. Alzheimer disease-related biomarkers and cancer-related cognitive decline: the thinking and living with Cancer study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2024;116(9):1495–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strehle LD, Otto-Dobos LD, Grant CV, Glasper ER, Pyter LM. Microglia contribute to mammary tumor-induced neuroinflammation in a female mouse model. FASEB J. 2024;38(2):e23419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bi F, Huang C, Tong J, Qiu G, Huang B, Wu Q, Li F, Xu Z, Bowser R, Xia XG, et al. Reactive astrocytes secrete lcn2 to promote neuron death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(10):4069–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cowland JB, Borregaard N. Molecular characterization and pattern of tissue expression of the gene for neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin from humans. Genomics. 1997;45(1):17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jha MK, Lee S, Park DH, Kook H, Park KG, Lee IK, Suk K. Diverse functional roles of lipocalin-2 in the central nervous system. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;49:135–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marques F, Mesquita SD, Sousa JC, Coppola G, Gao F, Geschwind DH, Columba-Cabezas S, Aloisi F, Degn M, Cerqueira JJ, et al. Lipocalin 2 is present in the EAE brain and is modulated by natalizumab. Front Cell Neurosci. 2012;6:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao N, Xu X, Jiang Y, Gao J, Wang F, Xu X, Wen Z, Xie Y, Li J, Li R, et al. Lipocalin-2 may produce damaging effect after cerebral ischemia by inducing astrocytes classical activation. J Neuroinflammation. 2019;16(1):168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee S, Park JY, Lee WH, Kim H, Park HC, Mori K, Suk K. Lipocalin-2 is an autocrine mediator of reactive astrocytosis. J Neurosci. 2009;29(1):234–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun Y, Fu Z, Bo Q, Mao Z, Ma X, Wang C. The reliability and validity of PHQ-9 in patients with major depressive disorder in psychiatric hospital. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jin K, Lu J, Yu Z, Shen Z, Li H, Mou T, Xu Y, Huang M. Linking peripheral IL-6, IL-1beta and hypocretin-1 with cognitive impairment from major depression. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:204–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Want EJ, Masson P, Michopoulos F, Wilson ID, Theodoridis G, Plumb RS, Shockcor J, Loftus N, Holmes E, Nicholson JK. Global metabolic profiling of animal and human tissues via UPLC-MS. Nat Protoc. 2013;8(1):17–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang M, Dong J, Yang S, Xiao M, Guo H, Zhang J, Wang D. Ecotoxicological effects of common fungicides on the eastern honeybee Apis cerana Cerana (Hymenoptera). Sci Total Environ. 2023;868: 161637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bao Y, Yan Z, Shi N, Tian X, Li J, Li T, Cheng X, Lv J. LCN2: versatile players in breast cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;171: 116091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stoesz SP, Friedl A, Haag JD, Lindstrom MJ, Clark GM, Gould MN. Heterogeneous expression of the lipocalin NGAL in primary breast cancers. Int J Cancer. 1998;79(6):565–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malone MK, Smrekar K, Park S, Blakely B, Walter A, Nasta N, Park J, Considine M, Danilova LV, Pandey NB, et al. Cytokines secreted by stromal cells in TNBC microenvironment as potential targets for cancer therapy. Cancer Biol Ther. 2020;21(6):560–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adler O, Zait Y, Cohen N, Blazquez R, Doron H, Monteran L, Scharff Y, Shami T, Mundhe D, Glehr G, et al. Reciprocal interactions between innate immune cells and astrocytes facilitate neuroinflammation and brain metastasis via lipocalin-2. Nat Cancer. 2023;4(3):401–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu Y, Dissing-Olesen L, MacVicar BA, Stevens B. Microglia: dynamic mediators of Synapse Development and Plasticity. Trends Immunol. 2015;36(10):605–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bai S, Guo W, Feng Y, Deng H, Li G, Nie H, Guo G, Yu H, Ma Y, Wang J, et al. Efficacy and safety of anti-inflammatory agents for the treatment of major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91(1):21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yan L, Yang F, Wang Y, Shi L, Wang M, Yang D, Wang W, Jia Y, So KF, Zhang L. Stress increases hepatic release of lipocalin 2 which contributes to anxiety-like behavior in mice. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):3034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guo Y, You J, Zhang Y, Liu WS, Huang YY, Zhang YR, Zhang W, Dong Q, Feng JF, Cheng W, et al. Plasma proteomic profiles predict future dementia in healthy adults. Nat Aging. 2024;4(2):247–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Frisardi V, Canovi S, Vaccaro S, Frazzi R. The significance of microenvironmental and circulating lactate in breast cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(20):15369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pitts FN Jr, McClure JN Jr. Lactate metabolism in anxiety neurosis. N Engl J Med. 1967;277(25):1329–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cai Y, Guo H, Han T, Wang H. Lactate: a prospective target for therapeutic intervention in psychiatric disease. Neural Regen Res. 2024;19(7):1473–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johnson PL, Fitz SD, Engleman EA, Svensson KA, Schkeryantz JM, Shekhar A. Group II metabotropic glutamate receptor type 2 allosteric potentiators prevent sodium lactate-induced panic-like response in panic-vulnerable rats. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27(2):152–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rinschen MM, Ivanisevic J, Giera M, Siuzdak G. Identification of bioactive metabolites using activity metabolomics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20(6):353–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bastings JJAJ, van Eijk HM, Olde Damink SW, Rensen SS. d-amino Acids in Health and Disease: A Focus on Cancer. Nutrients. 2019;11(9):2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Kong H, Liu X, Yang L, Qi K, Zhang H, Zhang J, Huang Z, Wang H. All-trans retinoic acid enhances bystander effect of suicide gene therapy in the treatment of breast cancer. Oncol Rep. 2016;35(3):1868–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li RJ, Ying X, Zhang Y, Ju RJ, Wang XX, Yao HJ, Men Y, Tian W, Yu Y, Zhang L, et al. All-trans retinoic acid stealth liposomes prevent the relapse of breast cancer arising from the cancer stem cells. J Control Release. 2011;149(3):281–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mather F. Amalgam controversy: an update for dental students. Dentistry. 1990;10(3):14–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Additional data relevant to the article are available from the corresponding author upon request.