Abstract

Objectives

Internships in the pharmacy departments of training hospitals represent a crucial stage in the professional development of pharmacy students. However, the quality of internship training varies significantly across training hospitals in China, and there is a lack of standardized readiness evaluation tools. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to develop a self-assessment tool to evaluate the preparedness of training hospitals for providing internship training.

Methods

This study employed an exploratory mixed-methods approach and was conducted in two phases. In the first phase, during 2021, focus groups were conducted with 16 interns from three tertiary hospitals in Henan Province. In 2022, 14 preceptors from tertiary hospitals in various provinces were interviewed either one-on-one or in focus groups. The interview data were analyzed using thematic analysis to compile a set of self-assessment indicators for internship training readiness. Subsequently, the initial draft of the self-assessment tool for internship training readiness was developed by integrating the indicators derived from the interviews and literature review. In the second phase, the Delphi method was utilized. In 2023, the experts participated in two rounds of correspondence (21 experts in the first round and 19 in the second round), and consensus was reached on the indicators of the self-assessment tool after the two rounds. Meanwhile, these experts assessed the current status of internship training in training hospitals across China.

Results

The qualitative findings of the first phase included five themes and 22 sub-themes, which were integrated with the indicators derived from the literature review to develop an initial indicator framework for the second phase. This initial framework comprised five domains and 37 items. The second phase involved two rounds of expert surveys, with effective response rates of 90.48% and 89.47%, respectively. Ultimately, the self-assessment tool for evaluating the readiness of pharmacy departments in training hospitals for internships included five dimensions and 35 secondary indicators: (1) organizational structure, (2) training content, (3) training mode, (4) effectiveness evaluation, and (5) emergency management. Additionally, experts assessed the readiness of pharmacy departments in Chinese training hospitals for internships, yielding varied results. Emergency management preparedness scored the highest, followed by organizational structure and training content preparation. However, the modes of internship training and the evaluation of training effectiveness received lower scores.

Conclusion

The developed tool provides a comprehensive self-assessment checklist for the pharmacy departments of training hospitals and possesses the potential to enhance the development of more effective internship training programs.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12909-024-06088-5.

Keywords: Internship, Training hospital, Readiness, Mixed method study

Introduction

Internships in training hospitals are crucial for pharmacy students, serving as a key transition from academic study to the professional role of hospital pharmacists, and helping students understand and adapt to the requirements of pharmaceutical services [1]. Training hospitals provide interns with opportunities to apply theoretical knowledge to practical tasks. Through practice in training hospitals, students enhance their communication and teamwork skills, and gain a deeper understanding of hospital operations and patient needs, thereby laying a solid foundation for providing personalized pharmaceutical care [2]. Moreover, training hospitals significantly impact the schedule, content setting, and training mode planning of pharmacy internships. A well-structured hospital-based pharmacy internship program can significantly enhance the professional competence and skills of the interns. Therefore, it is necessary to improve the readiness of training hospitals in internship programs and content to enhance the quality and satisfaction of the interns [3, 4].

Compared to the development of hospital pharmacy education in the United States over the past 60 years, pharmacy internships in China began later, resulting in an incomplete training system and a lack of widely accepted readiness assessment tools. Since 1980, several training hospitals have initiated clinical pharmacy course training and standardized post-graduation training for pharmaceutical students. In recent years, with the rapid advancement of China’s hospital pharmacy sector, relatively mature internship mentoring systems have gradually formed in some large comprehensive tertiary hospitals [5]In Beijing, the clinical practice and standardized training for hospital pharmacists post-graduation are divided into two stages. The first stage, known as the general pharmacist training phase, encompasses six core competencies: prescription review, drug dispensing, medication consultation, adverse reaction reporting, pharmacy management, and drug quality management. The second stage, the clinical pharmacist training phase, emphasizes the importance of developing six key skills: ward rounds, consultations, discussions on challenging cases, information intelligence, patient education, and medication history documentation. In November 2005, the Ministry of Health issued a notice and plan to pilot clinical pharmacist training projects, clarifying the purpose, objectives, content, funding, time, and management requirements of the training, exploring the model and related policies for the development of clinical pharmacists [6, 7]. In 2018, the Ministry of Education of China issued a notice regarding the construction of the National Clinical Teaching and Training Demonstration Center, which clarified the objectives, scope, and criteria for the establishment of training bases [8]. To further enhance the teaching quality of clinical pharmacists, the Chinese Hospital Association released regulations and a training outline for clinical pharmacist teacher training bases in 2023. This program includes a one-year intensive clinical training for pharmacists holding clinical pharmacist qualification certificates, with specific provisions for training content and evaluation methods. This development holds significant value for advancing pharmacy practice education in China [9]. Despite these advancements, current pharmacy internship programs in China still face several challenges, including the lack of national operational guidelines, insufficient systematic internship mentoring programs, a shortage of authoritative tools for evaluating internship effectiveness, and inconsistencies in training programs across different Training hospitals [10]. Therefore, developing a self-assessment tool tailored to the readiness of pharmacy departments in training hospitals is crucial for addressing these issues and improving the overall quality of pharmacy internships.

Assessing the readiness of pharmacy departments in training hospitals has long been a focal point of international research. However, research on self-assessment of internship readiness in China remains insufficiently detailed. Key assessment factors commonly utilized today include preceptor qualifications, training resources, the practicality of the internship program, comprehensive placement, effective assessment tools and feedback mechanisms, and the fostering of collaborative relationships [11]. Ensuring that training hospitals deliver high-quality and comprehensive training experiences through methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, and communication with interns is crucial for enhancing the competence and professionalism of interns [12]. Zhao et al. [13] reported tools for assessing interns’ training experiences, including the “Postgraduate Hospital Educational Environment Measure (PHEEM), Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), General Health Questionnaire-12 or 30 (GHQ-12 or GHQ-30), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), and Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI)”. These tools aim to assess the well-being of interns, identify areas for improvement, and provide a reference for self-assessment of internship readiness. However, research on the quality of individual components of these internships remains relatively limited. In China, while several scholars have examined the hospital pharmacy internship mentoring model, discussed associated challenges and solutions, and summarized preceptor experiences, there is still a need for more in-depth research on the effectiveness and quality of these internship components [14–18]. Additionally, there is still a lack of research on the quality of internships and their impact on interns.

As mentioned above, there are still deficiencies in China’s pharmacy internship training system. In previous studies, we used qualitative research methods to understand the experience and recommendations of internships in training hospitals from the perspectives of interns and preceptors. Interns who participated in the study mentioned the negative experiences encountered in the internship process, and reflected that there are still shortcomings in the current pharmacy internship in China, such as insufficient clinical faculty ability, unreasonable internship mode, and unscientific internship content [10]. Similarly, preceptors have also highlighted issues within training hospitals in China, including the absence of a systematic practice training plan, a lack of uniform standards for practicum training content and methods, insufficient assessment of interns’ clinical practice competence, and a shortage of scientifically valid assessment tools [19]. Based on prior research findings and the recognized the lack of self-assessment tools for internship training readiness in China, this study aims to conduct exploratory research within the context of pharmacy departments in training hospitals. The objective is to develop a self-assessment tool for evaluating internship training readiness, providing a valuable reference for advancing pharmacy internship training systems both in China and internationally.

Methods

Ethical approvals

Ethics was approved by The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University Institutional Review Board approved the protocol (2019-KY-304). Written informed consent was obtained from all the study participants.

Study design

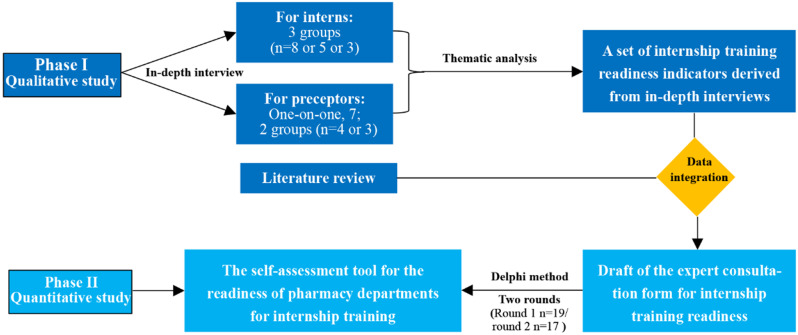

This study employed an exploratory mixed-methods approach [20] and was conducted in two phases. The first phase involved qualitative research, during which in-depth interviews were conducted with preceptors and interns. Based on these interviews, a set of self-assessment indicators was developed to provide empirical data for subsequent research. The second phase comprised quantitative research using the Delphi method, aimed at preliminarily validating the results from the first phase. Initially, literature was reviewed to identify relevant indicators, and the index collection from interviews was combined with those identified through literature research to create the first draft of the self-assessment index for internship training in medical institutions. Following two rounds of Delphi consultation, the self-assessment tool for internship training readiness in pharmacy departments was constructed and refined. We reported the entire mixed-methods study according to the Good Reporting of a Mixed Methods Study (See Appendix 1), the research ideas of this paper are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Research methodology

Phase I: Qualitative study

Participants

Focus group interviews were conducted with interns from large top three training hospitals in Henan Province (the first affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, the third affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, and the People’s Hospital of Henan Province) from February to June 2021. A series of interviews were conducted with preceptors from three general hospitals in China (The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University - Henan Province. Zhengzhou; the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhongshan University - Guangdong Province. Guangzhou; Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital - Sichuan Province. Chengdu) from January to March 2022. Purposeful sampling or snowball sampling was used for interns and preceptors.

The selection criteria for interns and preceptors are as follows. For interns: (1) generally speaking, pharmacy students in Chinese mainland start their internship in training hospitals in the fourth or third year, so we require them to complete at least three years of study in the School of Pharmacy, (2) in order to ensure that interns have enough understanding of hospital internships, we require Internship in the training hospital for at least three months. For preceptors: (1) pharmacists with intermediate titles are responsible for drug procurement, dispensing, and prescription review, guiding patients to use drugs rationally and serving in clinical pharmacy, and taking on certain scientific research and training tasks, generally, the preceptors are intermediate title or above, (2) having rich work experience, (3) having training experience as an intern. Both of them: are willing to participate in the present study.

Data collection

Researchers contacted interviewers directly by phone, WeChat, and email with recipients. Before the formal interview, we conducted pre-interviews with two interns and preceptors, then revised and supplemented the interview outline based on the interview data. A detailed outline of the interview is shown in Box 1. Participants were informed of the background and purpose of the study before each interview. Those who were willing to participate signed an informed consent form. The time and place of the interview were arranged according to the convenience of each participant. The interviews were conducted by the researcher (ZY) and recorded by the researcher (XDJ), (ZY and XDJ have rich training experience, and they conduct several qualitative studies with other groups). The entire interview process was audio-recorded. Data saturation was defined as “no new themes or codes emerging from interviews” [19]. The duration of the interviews with interns and instructors, the number of rounds of interviews, and the grouping are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Interview groups and interview durations for interns and preceptors

| Group information for interns and preceptors | Value | Interview duration |

|---|---|---|

|

Number of participants—interns, n Group 1—The first affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University Group 2—The third affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University Group 3—The People’s Hospital of Henan Province Number of participants—preceptors, n Group 1—The First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University Group 2— Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital One-on-one—The first affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University |

8 5 3 4 3 7 |

2 h and 45 min 56 min 1 h and 11 min 1 h and 1 min 45 min 32 (20–58) minutes |

| Box 1 Questions used in the interview guide |

|---|

| For interns: |

|

1. From your perspective, how should the pharmacy departments of medical institutions prepare for internship training? 2. Based on your own internship experience, do you think the current content, teaching methods, and evaluation methods of internship training are reasonable? What suggestions do you have? 3. Share the most impressive experience you had during your internship. |

| For preceptors: |

|

1. From your perspective, how should the pharmacy departments of medical institutions prepare for internship training? 2. What content do you usually cover when training interns? In your opinion, what aspects need improvement? 3. Do you think the current internship teaching methods are reasonable? What suggestions do you have? 4. How do you evaluate interns? What suggestions do you have regarding intern evaluation? 5. What do you think of the current readiness of the training hospital in terms of practice teaching? What do you suggest? 6. Share the good and bad experiences you have had in the teaching process. |

Data analysis

Interview data were analyzed using thematic analysis, a method widely used in qualitative research to identify, analyze, and report data patterns. Key steps in the topic analysis include familiarity with data, generating initial code, searching and reviewing topics, naming topics, and generating final reports, The researchers transcribed the recordings within 24 h, using NVivo12 to manage and analyze the data. After processing the transcribed interview data, the investigator confirmed with the participants that the results of the study were consistent with what the participants wanted to express. The two researchers independently extracted the code and wrote the first draft of the topic and subtopics. Subsequently, the research group discussed the first draft of the theme and sub-theme, and put forward opinions and suggestions on the topic structure and language expression, and the final theme and sub-theme were formulated with the consent of the research group, and the appropriate representative citations were selected to present the theme or sub-theme. The qualitative report follows the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist (see Appendix 2).

Phase II: quantitative study

Establishing of the expert panel

The selection of representative experts is crucial for the effective implementation of the Delphi method, as it determines the authority, scientific rigor, and validity of the research results [21, 22]. Generally, the optimal number of experts ranges between 15 and 50 [23]. Consequently, we established the following criteria for expert inclusion: (1) affiliation with well-known training hospitals that hold high rankings in China, (2) more than 5 years of professional experience in hospital pharmacy, (3) experience in teaching or management of internship training, and (4) willingness to participate in multiple rounds of expert consultations. Ultimately, 21 experts were selected for this study. These experts were from Central China (including the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Henan Provincial People’s Hospital, Henan Provincial Cancer Hospital), South China (the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University), and West China (Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital).

Research tools

Using the China Journal Full-text Database (CNKI), Wanfang Data, VIP Database, SinoMed, PubMed, Web of Science, The Cochrane Library, and EMBASE as literature sources, we conducted a comprehensive search for research related to pharmacy internships and teaching. The search period spanned from the inception of each database to April 2023, utilizing search terms such as “pharmacy interns,” “hospital pharmacy,” “internship training,” “training mode,” and “internship evaluation.” Based on a comprehensive analysis of qualitative results and literature review, the first draft of the Delphi correspondence was formulated through discussion by the research team. Prior to initiating the Delphi inquiry, the research team conducted cognitive interviews with two experienced preceptors from the pharmacy department of a training hospital [24]. During these interviews, the preceptors read the questions aloud, explained their understanding, and selected the options they deemed appropriate, thereby providing deeper insights into the questionnaire items. Following this, the draft was revised and refined. The first round of the Delphi correspondence questionnaire comprised 5 domains and 37 items, divided into three parts. The first part collected general information about the experts, including age, work experience, educational background, and professional title. The second part involved scoring the importance of self-assessment tool indicators using a Likert five-point scale, ranging from 1 (not important at all) to 5 (very important), with an additional recommendation column. The third part consisted of the index judgment basis table, which included the expert’s familiarity with the survey content and their scoring of the index judgment [25].

Data Collection

Two rounds of expert correspondence were carried out in strict accordance with the Delphi method. From June to August 2023, a survey was conducted using the online platform Questionnaire Star (Changsha Ranxing Information Technology Co., Ltd.), a free questionnaire platform widely used in China. First, we introduced the background of the study to the experts and obtained informed consent, and the experts scored the indicators and suggested modifications.

Data Analysis

We sorted out and summarized the opinions of experts, designed the second round of questionnaires, consulted experts again whether they agreed to delete the indicators with a mean value of < 4.0 and a coefficient of variation of > 0.25. Meanwhile, the experts were allowed to score the current status of the internship training in the training hospital in China [26]. Questionnaires were provided as supplementary materials (Appendices 3 and 4).

Excel and SPSS software were used to process the questionnaire results, and the importance of the indicators at all levels was expressed by arithmetic mean, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation. The questionnaire recovery rate represents the positive coefficient of experts, the coefficient of expert authority (Cr) is the average of the expert’s familiarity with the indicators (Cs) and the coefficient of indicator judgment (Ca) [27]. The degree of coordination of expert opinions is expressed by the coefficient of variation and the Kendall coordination coefficient, the Kendall coordination coefficient is used to test whether the experts’ scoring results of the indicators are consistent, the value is taken between 0 ~ 1, the closer to 1, the better the coordination degree of expert opinions. Then, the Spearman correlation was conducted to assess correlations between the average of the experts’ importance ratings for each indicator and the average of the experts’ ratings on the readiness to train for the internship.

Results

Demographic characteristics

The first phase of the qualitative study involved 16 interns and 14 preceptors. The average age of the interns was 21 years old, and the duration of the internship was more than 6 months. Their demographics are shown in Table 2. The average age of the preceptors was 36.1 years, the average length of service was 11.3 years. Their demographic data are shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of 16 interns

| Characteristics | Mean (SD) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender, n | |

| Male | 1(6.25) |

| Female | 15(93.75) |

| Age, years | |

| Mean (range) | 21(20–24) |

| Median(SD) | 21(1.05) |

| Major | Pharmacy |

| Number of departments rotated | |

| Mean (range) | 3(1–6) |

| Intership duration, months | |

| Mean (range) | 7.38(6–8) |

| Number of interns distributed among training hospitals | |

| The first affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University | 8(50.00) |

| The third affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University | 5(31.25) |

| The People’s Hospital of Henan Province | 3(18.75) |

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics of 14 internship instructors

| Characteristics | Mean (SD) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 6(42.86) |

| Female | 8(57.14) |

| Age, mean (range) | 36.1(27–52) |

| Working years, mean(range) | 11.3(4–30) |

| Title | |

| Intermediate level | 9(52.63) |

| Associate Advanced level | 7(42.11) |

| Advanced level | 1(5.26) |

| Number of interns trained(number) | |

| 01-Apr | 3(21.43) |

| 05-Oct | 8(57.14) |

| > 10 | 3(21.43) |

| Number of instructors distributed among training hospitals | |

| The First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University | 4(28.57) |

| Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital | 3(21.43) |

| The first affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University | 7(50.00) |

In the first phase of the quantitative study, 19 of the 21 invited experts responded to the questionnaire in the first round of the Delphi correspondence. In the second round of the Delphi Correspondence, 17 of the 19 invited experts answered the questionnaire. The sociodemographic information of the experts participating in the two rounds of Delphi letter consultation is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Demographic characteristics of the experts who participated in the two rounds of correspondence

| Characteristics | Delphi round 1 n (%) | Delphi round 2 n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of experts | 19 | 17 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 8(42.11) | 7(41.18) |

| Female | 11(57.89) | 10(58.82) |

| Age(years), mean (SD) | 37.74(5.97) | 37.94(5.97) |

| < 40 | 13(68.42) | 12(70.59) |

| 40–50 | 5(26.32) | 4(23.53) |

| > 50 | 1(5.26) | 1(5.88) |

| Work experience in pharmacy (years), mean (SD) | 12.11(6.94) | 12.24(7.22) |

| 4–9 | 10(52.63) | 9(52.94) |

| 10–19 | 7(36.85) | 6(35.30) |

| 20–29 | 1(5.26) | 1(5.88) |

| 30–39 | 1(5.26) | 1(5.88) |

| Title | ||

| Intermediate level | 10(52.63) | 9(52.94) |

| Associate Advanced level | 8(42.11) | 7(41.18) |

| Advanced level | 1(5.26) | 1(5.88) |

Qualitative results

The qualitative research in the first stage finally extracted 5 domains and 22 items, as shown in Fig. 2. The five domains are organizational structure for internships, internship training content, internship training mode, the evaluation of training effect, and emergency management of internship training. Results of the qualitative study for themes, sub-themes, and representative quotations are in Table 5.

Fig. 2.

Themes and subthemes from the first phase of qualitative research

Table 5.

Results of the qualitative study for themes, sub-themes, and representative quotations

| Dimension | Item | Representative quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Organizational structure | Hardware and facilities for internship | (G5P3) There are just too many people there, there’s limited space in the lab, and the students who go there can’t possibly say that if you’re interested, you can go to that kind of thing…. (G5P2) The mass spectrometer we have there are just so many students sitting there… I couldn’t even get into the room… Later, when that student came to me, there was no room for us to sit… |

| Detailed internship syllabus or manual | (G1P1) Then according to different specialties, there are different requirements, that is, for what you need to master the theoretical knowledge, what kind of clinical practice skills are a target requirement. So we have a basic syllabus to teach. | |

| Internship management rules and regulations | (G2P1) … It will also include organizational management, which is training in day-to-day work management. That is, when you go to work when you go off work, and then when you should obey the substitute teacher. And then there will be such a training, and then there is also leave, this is more critical, can not move leave, leave of absence of a management system training | |

| Individualized teaching programs | (P5) I think it is important to first of all, according to the intern’s position, that is, he may be a specialist, and the undergraduate of his foundation is not the same, he needs to master this is not particularly the same. | |

| Internship training content | Pre-job training (induction training) | (G2P2) When the students come over, I will do a half-hour to one-hour induction training. The main content is the distribution of our hospital, which is the basic information of the hospital, and then the basic information of the pharmacy department, because our pharmacy department may have more than ten departments in its management structure. The students may not be able to understand it, and then I will give them basic training. |

| Detailed internship syllabus or manual | (P7) I would give them a detailed, this is the plan for the internship. It’s just generally specific to the point where it would be specific to the week, it’s every week, and roughly what’s going to be covered would be listed out for him. | |

| Content and workflow of pharmacy work | (G2P2) For us it would be required, for example, in emergency medicine, then you would have to teach at least two per month, interns. We said then the content of this course should be related to the day-to-day work of our emergency medicine transfers. And then this is some of the systems, and then the basic processes, and some of the job specifications. | |

| Practical skills training | (P5)Then, in the outpatient department, you have to tell the patient what precautions there are for this medicine… (P4) in addition, you can also give patients medication education… | |

| Training in core competencies |

(G1P1) One of the main enhancement skills is the ability to review the literature and then organize it and summarise it… (G1P3)… This communication skill of yours, actually I think it’s as important as the professional course… (G5P2) I think that on the one hand, it’s developed my self-learning skills |

|

| Professional orientation and ethics training |

(P5) As an instructor, when you come into contact with the interns, you hope that they will make a lot of progress, or have a preliminary understanding of the direction of their future work… For example, the direction of pharmacists now is to have more contact with patients… (G4P2): It may give us some direction, there may be more choices after graduation to see which one they are suitable for… |

|

| Internship training mode | Intern’s needs and learning abilities | (G1P4) I think because frankly a variety of banding models, for an undergraduate intern, what kind of banding model does he need? I think it probably goes to the root of what kind of needs he has. Right? (G5P3) It should still depend on the individual, we were here when Mr.Pao told us that although it was mainly a sub kind of thing, it still allows you to choose on your own, and then after you’ve chosen it, the teacher in then adjusts it according to the real situation of each department. |

| Teaching model combining theory and practice | (G1P3) A model of practice leading… We focus very much on the practical aspect of it… | |

| Length of internship | (P3). One problem is that lies in the fact that it’s because some of the students who come to study have a long time, some have a short time, and the question of the length of time, yes, the question of the length of time, actually has a big impact on this for us. Because if it’s a short time, even though this is the piece of him that I’ve trained him well, he’s going to switch subjects soon. And then for me, I spend a lot but the student actually can’t fully grasp what the teacher is teaching. | |

| Certain degree of freedom in their time | (P7)… Then after coming to us, that is, we have relatively large degrees of freedom then, he may not have, not yet adapted (G4P3)…. People do want to specialize in this, learning is also quite good, specializing in this pressure is also quite big is special, just want to have a little more time to learn, you can negotiate it! | |

| evaluation of training effect | Meets the internship needs | (P7)… We will display our research directions one by one, and then let the students look at them and introduce them, and then see if they are interested in the direction of their graduate studies or if they are interested in their interests, and then we will let the teachers communicate with them after you have selected them. If you feel that they are a good match, then they will be assigned to the appropriate content of the subject group. |

| IEquipped with basic knowledge | (P1) There was a student from the Railway Institute of Vocational Technology, and when you asked him about antibiotics, cephalosporins, generation one, generation two, and generation three, he didn’t know, these are the most basic, the simplest, and he didn’t understand even when he asked him… Are you unable to teach him, how do you teach him… (G3P2) I think my truest feeling is that my knowledge is too little. The knowledge base is too little. I feel like I don’t know anything since I’ve been here. | |

| Evaluations of the internship process | (G1P3) Process assessment vs. In fact, our question paper is only for the final examination, it is a stage examination… Yes, and then the process assessment is actually like the medication education guide that I just mentioned or the medical advice pharmacy consultation. This is because it will be carried out every day… Finally the process of stopping clinical practice, you’ll see that he’s crossed the line. | |

| Two-way assessment | (G2P1) We kinda accept that two-way assessment …. The two-way, it includes the teacher’s consideration of the student, then our department’s consideration of the student, the hospital’s consideration of the student, and in turn, the student’s consideration of the instructor, the student’s consideration of the department in which he’s rotating. …. And then as well as the management of our department, he is in the pharmacy department, an evaluation of the pharmacy department, and even an evaluation of the entire management of the hospital. | |

| Theoretical examinations and clinical practice |

(G1P1) And then there’s also the paper that’s specifically for interns… And then there’s a paper for interns to improve their theoretical knowledge and professional skills. (G1P2) For clinical pharmacists, it’s generally theory, right? And then there’s also a skills test. |

|

| emergency management | Contact information for each other | (G1P1)…. And also with his guidance counselor and the group leader, anyway, all the various students went to contact him, and he couldn’t be contacted at home, including his parents, because he switched off his phone …. Then it was very anxious, yes, it was very anxious. |

| Emergency plans for safety and health | (G1P1) Then I asked their group leader, I said why this student didn’t come to class, and then the group leader said he didn’t know, and then later on he asked them to contact this student, and it turned out that no one could find him… That process was really too, too scary (P3) But I, if you have anything, anything, you have to take leave from me. Yeah, and then we’re still responsible for your safety here. | |

| There are two-way feedback channels | (G2P3) During the training in the admission to the department, they will be told that if they have any problems in the course of their daily internship, they can first react to the departmental team leader, for example, Mr Ren, or Mr Yuan. If you think it’s not good to communicate, you can come back to me, I’ll deal with it, I’ll communicate, will give them that (P2)… We have to communicate promptly, that is, you have to it’s quite normal that the problem is not resolved. But when you communicate, I know what you have probably worked on, and what are your interests in this area. |

Note: Code G1P1-G2P3, P1-P7 for the preceptor, G3P1-G5P5 for the intern

Quantitative results

In this study, the authority coefficient of experts is 0.779, close to 0.80, which indicates that the experts participating in this study have a high degree of authority. The Kendall coordination coefficient of the primary index was 0.216, P < 0.001, the Kendall coordination coefficient of the secondary index was 0.172, P < 0.001, the evaluation results of the indicators by the experts have consistency.

By integrating the results of the literature analysis with the findings from the qualitative research, the research team developed an initial Delphi consultation questionnaire that includes 5 domains and 37 items.

Delphi method round 1

In the first round, four experts proposed amendments, one of whom suggested deleting “3.4 Whether interns have some freedom of time”. The other three experts proposed language changes to four indicators, suggesting that the first level indicator “the degree of preparation of content for training internships” be changed to “training content readiness of internship”, and that the second level indicator “2.1 Whether interns are provided with training in vocational orientation and professional ethics in order to enhance interns’ awareness of the specialty and their future career planning” be changed to “Whether interns are provided with vocational orientation and professional ethics training “. The indicator “2.2 Whether to provide interns with career orientation and professional ethics training to enhance their awareness of the specialty and their future career planning” was changed to “The content of the pre-service training is well developed, including an introduction to the relevant pharmacy rules and regulations of the hospital and the department, the management rules for interns, and an introduction to the departmental settings and functions of the department”.“4.5 Whether there is a dynamic assessment of the internship process should be changed to Whether there is a regular or periodic evaluation of the internship process”. One of the experts suggested that “some secondary indicators have the phenomenon of multiple questions in one entry, which is not in line with the basic principle of entry design”, and after discussion by the panel, it was decided to change “2.10 Whether there is a training internship for clinical pharmacists specializing in prescription review, formulation of pharmacy monitoring plan, clinical medication guidance, rational medication evaluation, etc.” to “2.10 Whether there are training internships of specialized skills for clinical pharmacists”; 2.11 Whether interns are trained in core competencies such as communication skills, clinical thinking skills, research thinking skills, independent learning skills, critical thinking, etc. was changed to 2.11 whether interns are trained in the core competencies of pharmacists”. The mean, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation of each indicator were calculated by scoring the importance of the indicator by experts. The mean value of the primary indicator “preparedness for emergency management of internship training” and five secondary indicators (1.7; 3.4; 4.1; 4.2; 4.4) was < 4.0, and the coefficient of variation was > 0.25, so the experts were consulted again to see if they would agree to their deletion.

Delphi method round 2

In the second round, there was a consensus of expert opinion. Agreed with the language changes proposed in Round 1 for Level 1 Indicator “training content readiness of internship” and Level 2 Indicators 2.2, 2.10, 2.11, and 4.5, and disagreed with the language change for 2.1. All experts agreed to delete 1.7 and 3.4 and suggested retaining the primary indicator of preparedness for emergency management of internship training and the secondary indicators 4.1、4.2 and 4.4. After two rounds of correspondence inquiry, a self-assessment tool of the readiness of pharmacy departments for internship training is formed, which includes 5 first-level indicators and 35 s-level indicators, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Index system for self-evaluation of internship training

| Domains and item | Importance rating of indicators | Ratings the readiness in training hospitals | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | CV | Mean | SD | |

| 1. Readiness of the organizational structure for internships | 4.632 | 0.684 | 0.148 | ||

| 1.1 Whether there are sound rules and regulations for internship management | 4.684 | 0.671 | 0.143 | 89.412 | 10.880 |

| 1.2 Availability of relevant hardware and facilities in line with internship training | 4.526 | 0.612 | 0.135 | 88.824 | 12.187 |

| 1.3 Availability of an internship leadership team | 4.421 | 0.692 | 0.157 | 86.471 | 15.387 |

| 1.4 Availability of a selection program for internship preceptors | 4.105 | 0.809 | 0.197 | 81.176 | 19.648 |

| 1.5 Availability of job descriptions for internship preceptors | 4.158 | 0.688 | 0.166 | 78.235 | 18.787 |

| 1.6 Availability of a detailed internship lead syllabus or handbook | 4.632 | 0.597 | 0.129 | 84.706 | 18.748 |

| 1.7 Availability of individualized training programs tailored to the needs of the students*a | 3.737 | 0.933 | 0.250 | 63.529 | 30.402 |

| 1.8 Whether the internship instructors receive regular training in relevant training and pharmacy service training | 4.368 | 0.761 | 0.174 | 77.647 | 18.884 |

| 2. Training content readiness of internship *b | 4.789 | 0.419 | 0.087 | ||

| 2.1 Whether interns are provided with vocational orientation and professional ethics training*b | 4.526 | 0.772 | 0.171 | 75.294 | 19.722 |

| 2.2 The content of the pre-service training is well developed, including an introduction to the relevant pharmacy rules and regulations of the hospital and the department, the management rules for interns, and an introduction to the departmental settings and functions of the department*b | 4.474 | 0.841 | 0.188 | 87.647 | 11.472 |

| 2.3 Whether there is a detailed schedule and training plan for the progress of internship training in the training hospitals | 4.474 | 0.612 | 0.137 | 84.118 | 12.277 |

| 2.4 Availability of training in hospital pharmacy job content and workflow | 4.526 | 0.772 | 0.171 | 90.588 | 11.440 |

| 2.5 Availability of medicines dispensing skills, management skills, and practices | 4.421 | 0.838 | 0.189 | 88.824 | 13.639 |

| 2.6 Availability of medication counseling and medication instruction skills and practices | 4.263 | 0.806 | 0.189 | 78.824 | 19.001 |

| 2.7 Availability of pharmacy information technology operating system learning | 4.263 | 0.933 | 0.219 | 75.294 | 22.394 |

| 2.8 Availability of PIVAS job profile learning | 4.053 | 0.970 | 0.239 | 81.176 | 14.090 |

| 2.9 Availability of training on adverse drug reaction management and reporting process | 4.053 | 0.970 | 0.239 | 80.588 | 24.102 |

| 2.10 Whether there are training internships of specialized skills for clinical pharmacists*b | 4.368 | 0.955 | 0.219 | 80.000 | 21.506 |

| 2.11 Whether interns are trained in core pharmacist competencies*b | 4.316 | 0.671 | 0.155 | 72.353 | 22.229 |

| 2.12 Whether the internship instructor shows humanistic care for the interns in the process of training | 4.526 | 0.697 | 0.154 | 80.000 | 21.213 |

| 3. Readiness of the internship model | 4.368 | 0.761 | 0.174 | ||

| 3.1 Whether or not the internship preceptors use a diversified internship training model | 4.316 | 0.671 | 0.155 | 74.118 | 22.377 |

| 3.2 Whether to rationally arrange the content of training according to the length of internship time | 4.421 | 0.692 | 0.157 | 82.941 | 17.235 |

| 3.3 Whether the content of the training is organized by the intern’s practical needs and learning abilities | 4.053 | 0.970 | 0.239 | 74.706 | 17.363 |

| 3.4 Whether interns have some freedom of time*a | 3.421 | 1.071 | 0.313 | 71.176 | 19.327 |

| 3.5 Whether it is a combination of theoretical and practical models of training | 4.579 | 0.507 | 0.111 | 84.118 | 14.168 |

| 4. Readiness to assess the effectiveness of internships | 4.263 | 0.806 | 0.189 | ||

| 4.1 Whether interns are consulted to assess each individual’s internship needs | 3.684 | 1.057 | 0.287 | 70.000 | 20.917 |

| 4.2 Whether the training environment is assessed to meet the needs of the interns | 3.526 | 0.905 | 0.257 | 68.824 | 16.539 |

| 4.3 Whether or not the intern is assessed on whether the content of the internship meets the needs of the internship | 4.000 | 0.816 | 0.204 | 74.118 | 16.977 |

| 4.4 Whether interns are assessed to have the appropriate basic knowledge before joining the department | 3.842 | 1.119 | 0.291 | 64.118 | 21.523 |

| 4.5 Whether there is a regular or periodic evaluation of the internship process*b | 4.158 | 0.765 | 0.184 | 72.941 | 12.127 |

| 4.6 Whether the assessment of interns includes theoretical examinations and clinical practice tests | 4.474 | 0.513 | 0.115 | 77.647 | 19.852 |

| 4.7 Whether there is an evaluation of the effectiveness of the supervisor’s supervision by the internship supervision team | 4.158 | 0.765 | 0.184 | 69.412 | 25.365 |

| 4.8 Availability of interns’ assessment of the effectiveness of the preceptor’s guidance | 4.368 | 0.761 | 0.174 | 71.176 | 21.472 |

| 5. Preparedness for Emergency Management for Internship Leaders | 3.947 | 1.079 | 0.273 | ||

| 5.1 Whether to establish contact information for interns and preceptors | 4.368 | 0.684 | 0.157 | 93.529 | 10.572 |

| 5.2 Availability of two-way feedback channels for problems in the training process | 4.579 | 0.607 | 0.133 | 88.824 | 14.090 |

| 5.3 Availability of emergency plans for personal safety and health safety | 4.579 | 0.692 | 0.151 | 84.118 | 15.835 |

| 5.4 Whether to educate interns on occupational safety and promote self-protection awareness | 4.526 | 0.697 | 0.154 | 90.000 | 13.229 |

*a denotes the items in the table were included in the first Delphi method round 1 and later removed in the final version after Delphi round 2;*b denotes the items in the table were included in the first Delphi method round 1 and later edited in the final version after Delphi round 2; SD denotes standard deviation; CV denotes coefficient of variation

In Delphi method round 2, experts were asked to rate the current level of preparedness of China’s internship training in terms of each indicator on a scale from 0 to 100. The mean values of readiness for each indicator ranged from 61.118 (± 21.523)/100 (whether interns were assessed to have the appropriate basic knowledge before joining the department) to 93.529 (± 10.572)/100 (Whether to establish contact information for interns and preceptors). Among them, the readiness for emergency management of internship training was the highest, with an average of 89.118; the readiness for organizational structure of internship training (average: 81.25) and the readiness for internship training content (average: 81.226) were rated higher; The scores for the internship training model (average: 77.412) and the readiness for evaluation of internship training effects (average: 71.03) were low. Figure 3 shows Experts’ ratings on the importance of the internship training indicators and the current status of the training hospitals(r = 0.722, p < 0.0001).

Fig. 3.

Experts’ ratings on the importance of the internship training indicators and the current status of the training hospitals. X denotes the average of the experts’ importance ratings for each indicator. Y denotes the average of the experts’ ratings on the readiness to train the internship

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in mainland China to utilize a mixed-methods approach, incorporating both qualitative and quantitative research stages, to construct a readiness assessment for pharmacy internship in training hospitals. The findings indicate that pharmacy departments in training hospitals should prepare systematically and appropriately in the organization, training content, training modes, evaluating methods, and emergency management. Meanwhile, experts’ ratings of readiness for various aspects of internship training varied, indicating that our training hospital needs improvement in the following areas.

The results of this study reveal that the organizational structure of internship training encompasses the infrastructure and hardware of the training hospital, systems related to internship training, and the selection and training of preceptors. Notably, assessments related to the organizational structure of internship training indicated low ratings for the criteria “Availability of job descriptions for preceptors” and “Whether the preceptors receive regular training in relevant training and pharmacy service training.” Chinese pharmacy graduates face challenges such as a lack of clinical rotation training systems, legal safeguards, action guidelines, qualified clinical practice preceptors, and accredited internship sites [28]. In Japan [29], the government has established accreditation standards for internship sites to ensure effective internships, including basic hardware facilities, standardized preceptor qualification requirements, and well-defined training guidelines and assessment programs. Similarly, in Korea [30–32], universities and hospital pharmacies have collaborated to create and enhance education and assessment models. The hospital pharmacy department primarily manages students’ internships, while the school supports the training hospital, facilitating close collaboration and mutual development. Currently, some large training hospitals and major pharmacy chains in China have established internship bases with schools, accommodating numerous pharmacy interns from higher vocational colleges and universities. However, there is no unified certification standard for constructing these internship bases, and detailed requirements for the hardware and preceptor experience are lacking, which undermines the effectiveness of the internships [33]. Based on this analysis, future efforts should focus on enhancing preceptors’ job awareness, improving their comprehensive abilities, and developing a robust access system, effective training evaluation mechanisms, and a comprehensive support structure [34].

The findings of this study indicate that the content of internship training comprises several key components: career orientation and professional ethics training, pre-service training, training within the dispensing department, and practical training in clinical settings. However, interns reported relatively low ratings regarding their experiences in career orientation and professional ethics training, core competencies for pharmacists, and the operation of pharmaceutical information technology systems. This suggests a need for improvement in these critical areas of the internship program. Internship is a critical period for most graduates’ career decision-making, and graduation internship is an important way for students to fully understand the content of the work and the current employment situation, enabling them to make informed decisions about employment and further education. Additionally, internships provide better preparation for future clinical work [35]. Therefore, during the internship period, efforts should be made to enhance interns’ awareness of the pharmacy profession and help them plan their careers for the future [36]. The core competencies of hospital pharmacists refer to the knowledge, skills, judgment, and personal attributes required for pharmacists to provide safe, effective, cost-effective, and ethical patient-centered pharmacy services. These competencies include professional practice, coordination and communication, management, professional development, and critical thinking [37–39]. This study shows that the interns do not master these core competencies in the current training process. Pharmacy service is an important part of promoting rational drug use and ensuring the safety of patients. Strengthening the training of core competencies of pharmacists can improve the level of pharmaceutical services [40].

The research results show that internship training modes include diversified training approaches, combining theory and practice, and arranging training content according to the length of the internship and the different levels of interns. The ratings for adopting diversified training methods and arranging training content according to interns’ needs and learning abilities were low. The traditional internship training mode is mostly led by the preceptor, with interns in a passive acceptance state, which weakens their motivation to learn and reduces their initiative [41]. New training methods such as Problem-Based Learning (PBL) [42] and Case Based Learning (CBL), can help improve the effectiveness of internships [43]. The use of diversified training methods stimulates students’ motivation and enhances their independent learning and research abilities, equipping them with good clinical and communication skills and thus improving the effectiveness of the internship [44]. At the same time, the results also showed that the current training model did not arrange personalized training content according to students’ personal interests, basic knowledge, or career planning. Given the varying levels of interns in China’s pharmacy program, preceptors should rationally arrange the content of training according to the interns’ needs and learning abilities.

The results of this study show that the assessment of the effectiveness of internship training should include access assessment, process assessment, outcome assessment, and bidirectional assessment. However, the overall score of the evaluation effect of intern training in China is the lowest, indicating a disparity between China’s internship training system and those of developed countries in these aspects: (1)Lack of Access Assessment: Due to the late start of pharmacy internship training in China, the pharmacy departments of training hospitals accept interns at different levels of specialties, including undergraduate and master’s degrees, without consistent criteria for access assessment. In Japan, students are required to pass the Pharmacy Common Achievement Test (CBT: Computer-Based Testing and OSCE: Objective Structured Clinical Examination) before participating in pharmacy internships, preventing students without pharmacist licenses from participating in training site pharmacy internships [29, 45]. In the United States, a pharmacist can only become a clinical pharmacist after obtaining a Doctor of Pharmacy degree, passing the national standardized examination, and undergoing 1–2 years of residency training [46]. (2) Deficiencies in Process and Outcome Evaluation: China’s pharmacy graduates generally exhibit poor practical abilities, primarily due to an imperfect practice education system. Domestic training hospitals mostly use traditional written and operational examinations and lack a comprehensive assessment and evaluation system for internship outcomes [15]. In contrast, foreign pharmacy internships require participation in several practical courses throughout the entire professional learning period. Assessments include daily attendance, online testing, meeting and discussion performance, evaluations by mentors and classmates, and other forms of assessment, with each part contributing to the final results according to specific weightings [47]. (3) Need for a Two-Way Assessment Scheme: A two-way assessment includes the evaluation of both preceptors and interns. The evaluation of preceptors mainly involves feedback from interns and the training team, providing a comprehensive assessment of the preceptor’s training attitude, training content, and training effectiveness. This study underscores the necessity for systematic improvements in the assessment methods used for pharmacy internship training in China.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this paper are reflected in several key aspects: (1) The indicators of the self-assessment tool are primarily derived from the personal experiences of interns and instructors. They are constructed based on the consensus of Delphi experts, which improves the practicability and operability of the self-assessment tool. (2) The experts involved in this study came from the pharmacy departments of many top tertiary training hospitals in Central, Southern, and Southwestern China, which to some extent enhanced the study’s rigor and representativeness. However, several limitations are noteworthy. Firstly, the self-assessment tool for internship teaching readiness is a dynamic system that will evolve with the development of hospital pharmacy and national healthcare reform. It requires ongoing improvement and refinement of relevant indexes to ensure specificity and practicality. Secondly, this study has not conducted a large-scale empirical study on the self-assessment tool; the next step will be to conduct nationwide empirical studies to test the reliability and operability of the self-assessment tool, and to further improve the index system so that it will be more valuable for practical application.

Conclusion

The self-assessment tool for internship training readiness developed in this study can provide a checklist for the pharmacy departments of training hospitals. Based on our research results, we cautiously put forward the following recommendations: training hospitals should enhance infrastructure and hardware, establish relevant internship training systems, and develop selection and training programs for preceptors. The content of internship training should include pre-job training, training in the dispensing department, and training in clinical departments. A diversified approach should be adopted for the internship training model. For evaluating the effectiveness of internship training, there should be standards for admission evaluation, process evaluation, outcome evaluation, and bidirectional evaluation. Regarding emergency management in internship training, there should be emergency management plans and bidirectional feedback channels. China’s government departments should introduce a systematic pharmacy internship syllabus and training system, a selection system for internship training bases, and an authoritative internship effect evaluation tool. Given the limitations of this study, our team will continue further research. We plan to select multiple training hospitals across central, eastern, western, northern, and southern China to conduct large-scale empirical studies to test the reliability and operability of the tool, thereby providing evidence for its application.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of all the interviewees and Correspondence experts who participated in the study.

Author contributions

ZY designed the study; ZY and XDJ conducted the interviews; HTH and ZY analyzed the data, HTH wrote the manuscript. ZY was particularly involved in the drafting, and revising of the different versions of the manuscript, and final approval of the version to be published. All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design, All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by Henan Medical Education Research Project (WJLX2023016) 、 Henan Provincial Medical Science and Technology Public Welfare Program Soft Science Project, (RKX202302017) and Henan Zhongyuan Medical Science and Technology Innovation Development Foundation(ZYYC202301YB).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the Co-first author on reasonable request. Co-first author: Huitao Huang,hhtczybj@163.com; Zhao Yin, yinzhao0601@163.com.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics was approved by The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

The Institutional Review Board approved the protocol (2019-KY-304). Written informed consent was obtained from all the study participants. The study was conducted by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Huitao Huang and Zhao Yin contributed equally much to this article.

Contributor Information

Huiling Yang, Email: yanghlyfy@163.com.

Youhong Hu, Email: hyouhong@163.com.

References

- 1.Gimeno-Jorda M J, Gimenez-Poderos T, Negro-Vega E, et al. Evaluation of specialized training in hospital pharmacy[J]. Farm Hosp. 2020;44(5):198–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steeb D R, Zeeman J M, Bush A A, et al. Exploring career development through a student-directed practicum to provide individualized learning experiences[J]. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2021;13(5):500–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abublan RS, Nazer L H, Jaddoua S M, et al. A hospital-based Pharmacy Internship Program in Jordan[J]. Am J Pharm Educ. 2019;83(3):6547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Lababidi R, Osman F. Outcomes of a pharmacy internship program at a Quaternary Care Hospital[J]. Farm Hosp. 2022;46(4):251–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hou J, Michaud C, LI Z, et al. Transformation of the education of health professionals in China: progress and challenges[J]. Lancet. 2014;384(9945):819–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qu J, Liu GF, Zhu Z, et al. The construction and development of hospital pharmacy in China(Part III)[J]. Constr Dev Hosp Pharm China. 2014;34(17):1423–33. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li J, Xiao C, Hou J, et al. Clinical pharmacy undergraduate education in China: a comparative analysis based on ten universities’ training programs[J]. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2018-12/31/content_5439357.htm

- 9.https://www.cha.org.cn/site/content/22ee3d2662e2d85b24a064851f550a81.html

- 10.Yao X, Jia X, Shi X, et al. Exploring the experiences and expectations of pharmacist interns in large general hospitals in China: from the perspective of interns[J]. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanmartin-Fenollera P, Zamora-Barrios M D, Gimenez-Poderos T, et al. Specialized training in hospital pharmacy: an overview of the concerns, needs and current situation of resident tutors[J]. Farm Hosp. 2021;45(6):289–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koster ES, Philbert D. Communication and relationship building in pharmacy education: experiences from a student-patient buddy project[J]. Curr Pharm Teach Learn, 2023,15(4): 393–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Zhao Y, Musitia P, Boga M, et al. Tools for measuring medical internship experience: a scoping review[J]. Hum Resour Health. 2021;19(1):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo X, Yao D, Liu J, et al. The current status of pharmaceutical care provision in tertiary hospitals: results of a cross-sectional survey in China[J]. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rao Y, Zhao Q, Zhang X, et al. Current status and future prospects of the development of clinical pharmacy in China: a SWOT analysis[J]. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2016;29(2):415–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen B, Huang J J, Chen H F, et al. Clinical pharmacy service practice in a Chinese tertiary hospital[J]. Drug Metab Pers Ther. 2015;30(4):215–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu M, Yee G, Zhou N, et al. Development and current status of clinical pharmacy education in China[J]. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(8):157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lian S, Xia Y, Zhang J, et al. Comparison of general practice residents’ attitudes and perceptions about training in two programmes in China: a mixed methods survey[J]. Fam Med Community Health. 2019;7(4):e238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu X, Zhang W, Jia X et al. Exploring the problems and coping strategies of pharmacy internship in large general hospitals in China: from the perspective of preceptors[J]. BMC Med Educ, 2024,24(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Liu C, Chu H L, Li G, et al. The 20 most important questions for novices of full-endoscopic spinal surgery in China: a mixed-method study protocol[J]. BMJ Open. 2021;11(8):e49902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Black M, Matthews L R, Millington MJ. Using an adapted Delphi process to develop a survey evaluating employability assessment in total and permanent disability insurance claims[J]. Work. 2018;60(4):539–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campos-Luna I, Miller A, Beard A, et al. Validation of mouse welfare indicators: a Delphi consultation survey[J]. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):10249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hao J, Qiao LJ, Huang HT, et al. Construction of hospital pharmacists job satisfaction scale by Delphi method and analytic hierarchy process[J]. China J Hosp Pharm. 2021;41(2):200–6. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spark MJ. Application of cognitive interviewing to improve self-administered questionnaires used in small scale social pharmacy research[J]. Res Social Administrative Pharm. 2014;10(2):469–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei J, Fang X, Qiao J, et al. Construction on teaching quality evaluation indicator system of multi-disciplinary team (MDT) clinical nursing practice in China: a Delphi study[J]. Nurse Educ Pract. 2022;64:103452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maher E, Nielsen S, Summers R, et al. Core competencies for Australian pharmacists when supplying prescribed opioids: a modified Delphi study[J]. Int J Clin Pharm. 2021;43(2):430–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sutherland K, Yeung W, Mak Y, et al. Envisioning the future of clinical analytics: a modified Delphi process in New South Wales, Australia[J]. BMC Med Inf Decis Mak. 2020;20(1):210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng JC, Zhang H, Wu B, et al. Medical Education Reform in China: the Shanghai Medical Training Model[J]. J Grad Med Educ. 2020;12(6):655–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Utsumi M, Hirano S, Fujii Y et al. Evaluation of pharmacy practice program in the 6-year pharmaceutical education curriculum in Japan: hospital pharmacy practice program[J]. J Pharm Health Care Sci, 2015,1(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Song Y K, Chung E K, Lee YS, et al. Objective structured clinical examination as a competency assessment tool of students’ readiness for advanced pharmacy practice experiences in South Korea: a pilot study[J]. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin RD, Ngo N, Silva H, et al. An objective structured clinical examination to assess competency acquired during an introductory pharmacy practice Experience[J]. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(4):7625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoo S, Song S, Lee S, et al. Addressing the academic gap between 4- and 6-year pharmacy programs in South Korea[J]. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(8):149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen B, Jin X. Zhou J, Satisfaction of clinical teachers on Standardized Residency Training Program (SRTP) in China: a cross-sectional Survey[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2022,19(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Yang Q, Zhang YZ, Shao ML Consideration on the construction of the Teaching Team in clinical pharmacy practice Base[J]. China Pharm. 2017;28(27):3875–8. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Almarzoky A S, Elrggal M E, Salamatullah A K, et al. Work readiness scale for pharmacy interns and graduates: a cross-sectional study[J]. Saudi Pharm J. 2021;29(9):976–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noble C, Coombes I. Making the transition from pharmacy student to pharmacist: Australian interns’ perceptions of professional identity formation[J]. Int J Pharm Pract. 2015;23(4):292–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mclaughlin JE, Bush A A, Rodgers P T, et al. Exploring the requisite skills and competencies of pharmacists needed for success in an Evolving Health Care Environment[J]. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(6):116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saseen JJ, Ripley T L, Bondi D, et al. ACCP Clin Pharmacist Competencies[J] Pharmacotherapy. 2017;37(5):630–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chu YJ, Yin Z, Liang Y, et al. The index system of hospital pharmacists’ core competence constructed by using Delphi method and analytic hierarchy process[J]. China J Hosp Pharm. 2019;39(11):1198–202. [Google Scholar]

- 40.https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2018-12/31/content_5436829.htm

- 41.Cen X Y, Hua Y, Niu S, et al. Application of case-based learning in medical student education: a meta-analysis[J]. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25(8):3173–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou J, Zhou S, Huang C et al. Effectiveness of problem-based learning in Chinese pharmacy education: a meta-analysis[J]. BMC Med Educ, 2016,16(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Zhao W, He L, Deng W, et al. The effectiveness of the combined problem-based learning (PBL) and case-based learning (CBL) teaching method in the clinical practical teaching of thyroid disease[J]. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karimi R. Interface between problem-based learning and a learner-centered paradigm[J]. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2011;2:117–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamada K. [Clinical training of pharmacists after Licensure and Career paths in Medical Institutions][J]. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2022;142(9):965–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Joseph T, Hale G M Moreauc. Training pharmacy residents as transitions of care specialists: a United States perspective[J]. Int J Clin Pharm. 2021;43(3):756–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zeitoun A A, EL Z H, Zeineddine MM. Effect of pharmacy practice program on pharmacy student learning, satisfaction, and efficiency: assessment of introductory pharmacy practice course[J]. J Pharm Pract. 2014;27(1):89–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the Co-first author on reasonable request. Co-first author: Huitao Huang,hhtczybj@163.com; Zhao Yin, yinzhao0601@163.com.