Abstract

Background.

This systematic review/meta-analysis aimed to synthesize empirical evidence from randomized controlled trials on the efficacy of culturally adapted interventions (CAIs) for substance use and related consequences for adults of color.

Methods.

Six electronic databases were searched to identify eligible studies. Two reviewers independently screened studies, extracted data, and assessed risks of bias. We used robust variance estimation in meta-regression to synthesize effect size estimates and conduct moderator analyses.

Results.

Twenty-two studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. The overall effect size was .23 (95% Confidence Interval [CI]= .12, .35). The subgroup effect sizes for comparing CAIs with inactive controls and with active controls were .31 (CI=.14, .48) and .14 (CI=-.02, .29), respectively. The effect sizes for alcohol use, illicit drug use, unspecified substance use outcomes, and substance use related consequences were .25 (CI=.08, .43), .35 (CI =-.30, 1.00), .22 (CI=-.17, .62), and .02 (CI=-.11, .16), respectively. Moderator analysis showed that CAIs’ effects might not vary significantly by treatment model, dose, country, follow-up assessment timing, participant age, or gender/sex.

Conclusions.

Research on substance use interventions that are culturally adapted for people of color is growing, and more high-quality studies are needed to draw definitive conclusions about CAIs’ treatment effects. Our study found CAIs to be a promising approach for reducing substance use and related consequences. We call for more efficacy/effectiveness and implementation research to further advance the development and testing of evidence-based CAIs that meet the unique needs and sociocultural preferences of diverse populations.

Keywords: Culturally adapted interventions, Racial/ethnic minorities, Alcohol use, Drug use, Substance use related consequences, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

1. Introduction

The increasing diversity in the United States (US) population is fueled by rapid growth in racial and ethnic groups, accounting for 28% and 16% of the population, respectively (United States Census Bureau, 2010). Accumulating evidence indicates that existing health disparities related to alcohol and drug use among people of color are growing. Between 2001–2002 and 2012–2013, increases in alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder (AUD) were the greatest among racial/ethnic minorities compared to non-Hispanic White (NHW) individuals (Grant et al., 2017). Moreover, despite lower prevalence rates of substance use than NHW people, people of color (Latino/a, Black/African American, American Indian/Alaskan Native [AIAN]) show a greater burden of poor health and consequences as a result of use (Huang et al., 2006; Mulia, et al., 2008; Turner & Lloyd, 2002; Whitbeck et al., 2012; Zapolski et al., 2014). For example, Latino/a people are more likely to be arrested for being under the influence of alcohol than other racial/ethnic groups and meet criteria for AUD (Grant et al., 2017; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2019), paralleling findings for Native Americans, who are more likely to meet 12-month criteria for AUD than other racial/ethnic groups (SAMHSA, 2019; Whitbeck et al., 2012). In addition, Black/African Americans and Native Americans are significantly more likely to meet the criteria for comorbid drug use disorder (DUD) and mood disorder (Huang et al., 2006).

Yet, despite bearing a greater burden of substance use, people of color have lower access, initiation, and retention rates and poorer response to substance use treatment (Alegria et al., 2002; Caetano, 2003; Campos-Outcalt et al., 2002; Carroll et al., 2009; Creedon and Cook, 2016; Guerrero et al., 2013; Manuel, 2017; Redmond et al., 2009; Saloner and Cook, 2013; Schmidt et al., 2006; US Department of Health and Human Services, 2003; Wells, et al., 2001). Therefore, there is a critical need for interventions that can help reduce substance-use-related health disparities and meet the unique needs and preferences of people of color.

1.1. The Need for Cultural Adaptation

Culturally adapting interventions is believed to minimize racial/ethnic health disparities related to substance use (National Institutes of Health, 2020). In the present study, we define cultural adaptation as cultural, linguistic, and contextual modifications to existing evidence-based practices that take into consideration a client’s worldviews, including personal and cultural values (Bernal et al., 2009). Culturally adapted interventions (CAIs) may make treatments more accessible and relevant to people of color, thus increasing individual engagement (initiation, retention) among marginalized groups who traditionally have been found to underutilize substance use services (e.g. Latino/a, Asian Americans, immigrants) (Brach and Fraserirector, 2000; Zemore et al., 2018). Indeed, research has found that culturally adapting substance use services (e.g., using culturally competent, bilingual Asian therapists) resulted in improved service utilization among Asian Americans (Yu et al., 2009). Studies of cultural adaptation are also considered to be important to advance intervention implementation and dissemination because they help to answer under what conditions, for whom, and where interventions might be most appropriate for different racial/ethnic groups (Baumann et al., 2017; Steiker, 2008).

Reviews of some evidence-based substance use interventions have concluded that there is a need for culturally adapted treatment models. Windsor et al. (2015) conducted a meta-analysis that compared studies investigating the effects of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) on substance use with predominantly NHW samples to studies with predominantly Black and/or Latino/a samples. Based on 16 studies, this meta-analysis found CBT’s effect sizes were significantly larger in NHW studies than in Black/Latino/a studies. This indicated a need for further testing the efficacy of CBT among Black and Latino/a people and for culturally adapting CBT to improve outcomes among people of color. Similarly, a review on Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT), an evidence-based substance use intervention, also suggested that SBIRT’s efficacy among people of color may be improved and validated through adaptation (Manuel et al., 2015).

1.2. Existing Reviews on Culturally Adapted Substance Use Interventions

Several systematic reviews have examined culturally adapted substance use interventions and generally found CAIs to offer promise as an effective approach to address substance use among youth and adults of color (Hernandez Robles et al., 2018; Hodge et al., 2012; Leske et al., 2016; Steinka-Fry et al., 2017; Valdez et al., 2018).

Three reviews investigated CAIs’ efficacy for improving substance use outcomes among youth of color and all yielded small yet positive treatment effects (Hernandez Robles et al., 2018; Hodge et al., 2012; Steinka-Fry et al., 2017). Specifically, both Hodge et al. (2012) and Steinka-Fry et al. (2017) reviews focused on youth from diverse racial/ethnic groups and found CAIs to be associated with significantly larger reductions in substance use compared to comparison conditions. Hernandez Robles et al. review (2018) focused specifically on Latino/a adolescents and found CAIs to have small effects on substance use outcomes at posttest and slightly larger effects at follow up.

Only two existing systematic reviews examined CAIs’ effects for substance use among adults of color and each focused on a specific racial/ethnic group (Leske et al., 2016; Valdez et al., 2018). Leske et al. (2016) reviewed culturally non-adapted, culturally adapted, and culture-based interventions for indigenous adults with mental or substance use disorders in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the US. It identified one study on culturally adapted substance use intervention for indigenous adults, which found a significant reduction in alcohol use outcomes among a primarily indigenous adult sample of first-time driving while intoxicated offenders (Leske et al., 2016; Woodall et al., 2007). Another review focused on Latino men and found that the most scientifically rigorous studies suggested that CAIs outperformed standard treatment for improving the physical, behavioral, and social outcomes among Latino men with substance use problems (Valdez et al., 2018).

1.3. The Present Study

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no systematic review or meta-analysis has reviewed the existing literature on CAIs for substance use among adults of color. To narrow this research gap, the present study sought to synthesize the best quality research evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCT) on culturally adapted substance use interventions for adults of color. We aim to provide implications for clinical/policy practice and future research by systematically identifying and reviewing existent RCTs on CAIs for substance use and related consequences, summarizing the study and intervention characteristics, and critically assessing study quality. We also conducted a meta-analysis, which applies objective formulas (objective relative to narrative reviews) to estimate treatment effect sizes and makes it more feasible to synthesize research evidence across many studies. In light of the diverse nature of CAI studies (across countries, treatment models, populations, etc.), we also conducted moderator analysis and subgroup analysis to account for the heterogeneity of the studies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Studies included in this review met the preset eligibility criteria described below.

2.1.2. Interventions

We included CAIs that targeted the prevention or reduction of alcohol and/or illicit drug misuse among adults. Our review of the literature identified interventions from studies of cultural adaptation that made: (1) explicit reference to “adapting” treatment to the preferences or lifestyles of the population, with information on the adaptation provided; or provided (2) commentary on a trial that was inadvertently or partially adapted (i.e., providing the intervention in a different language or through ethnic matching between client and provider).

2.1.3. Control Conditions

Control conditions included no treatment, waitlist control, treatment as usual (TAU), standard care (SC), or not/less culturally adapted interventions. Control conditions were categorized as being (a) inactive or (b) active (Higgins et al., 2019). An inactive control condition meant that the study estimated the CAI’s absolute effects, i.e., that it was designed to show whether people benefit from receiving the CAI compared with not receiving it at all (Higgins et al., 2019). An active control condition means that the study estimated the CAI’s relative effects, i.e., that it was designed to show whether the CAI is more efficacious/effective than another intervention (Karlsson and Bergmark, 2015). Inactive controls included no treatment (e.g., Tsai et al. 2009), waitlist control (e.g., Pearson et al. 2019), and TAU/SC alone (when compared with TAU/SC+CAI) (e.g., Robles et al. 2004). In contrast, active controls included treatment (e.g., non-fully-culturally-adapted interventions) (e.g., Lee et al. 2019) and TAU/SC alone (compared with CAI alone) (e.g., Carroll et al. 2009).

2.1.4. Study Outcomes

Study included one or more outcomes on alcohol or illicit drug use (e.g., frequency, dose, % days of abstinence), or substance-use-related consequences (e.g., the Drinker Inventory of Consequences [DrInC]).

2.1.5. Populations

Study participants were adults ages 18 or older with substance use problems (e.g., heavy drinking, illicit drug use, substance use disorders).

2.1.6. Study Design

Studies employed the RCT design.

2.1.7. Other Criteria

Studies were not excluded based on publication date, publication status, or country. However, studies were excluded if they were not written in English or if they did not report sufficient data for effect size calculation.

2.2. Search Strategy

The Cochrane recommendations for searching RCTs were followed for the search process (Higgins et al., 2019). Six electronic databases were searched: APA PsycINFO, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, Social Sciences Full Text, CINAHL, PubMed, and ProQuest Dissertation and Theses Global. Database-specific strategies were used for each database. An example of search terms used is (“culturally adapted” OR “cultural adaptation” OR adapt* OR translate* OR multicultural OR “cross-cultural” OR ethnic* OR bicultural OR intercultural OR “culturally relevant” OR “culturally sensitive” OR “culturally competent” OR sociocultural OR social* OR immigration OR discrimination OR “immigration stressors” OR acculturation OR linguistic) AND (alcohol OR drug OR substance) AND (random* OR experiment* OR RCT). These electronic databases comprise peer-reviewed journal articles, books and book chapters, as well as gray literature including dissertations/theses, conference abstracts, presentations, proceedings, and standards of practice. We also consulted experts in culturally adapted addiction interventions and reviewed the reference lists of other CAI systematic reviews/meta-analyses and studies included in this review to identify additional eligible studies (including both published and unpublished studies).

2.3. Selection of Studies

Two reviewers independently conducted the title and abstract screening and full-text screening. The inter-rater agreement rate was 98.6% (i.e., the number of studies with a consensus in a reviewer pair divided by the total number of studies screened). Disagreements between reviewers during the screening process were resolved through discussion and consultation with a third reviewer.

2.4. Data Extraction

We designed a data extraction form for summarizing and analyzing the study information based on Cochrane’s recommendations (Higgins et al., 2019). The data extraction form was intended to collect information on bibliography information, participants and setting descriptors, intervention descriptors, and effect size data. The data extraction form may be obtained from the first author. Two reviewers coded the studies independently and resolved areas of discrepancies through discussion with a third reviewer. The interrater reliabilities in data extraction were acceptable with kappa for categorical variables ranging from .79 to .94 and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for continuous variables ranging from .81 to .96.

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

Two reviewers independently conducted risk of bias assessment using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials (RoB 2.0) (Sterne et al., 2019). Studies were rated with low risk of bias, some concerns, and high risk of bias in six domains: (1) bias arising from the randomization process, (2) bias due to deviations from intended interventions, (3) bias due to missing outcome data, (4) bias in the measurement of the outcome, (5) bias in the selection of the reported result, and (6) overall risk of bias.

2.6. Data Analysis

We used R Studio to conduct data analysis in three steps: (1) estimating individual effect sizes, (2) synthesizing effect size estimates and conducting moderator analyses using robust variance estimation in meta-regression, and (3) conducting sensitivity analysis and publication bias assessment. Effect sizes were estimated using Hedges’s g effect size with Hedge’s small sample size correction (noted as d) (Cooper et al., 2009; Hedges and Olkin, 1985). Positive effect sizes indicate better outcomes.

Given the heterogeneous nature of the studies included in this review (Q[df = 119]= 224.42, p < .001, I2= 46.97%), random-effects model was used for meta-analysis which allows the true effect size to differ by studies rather than assuming a common true effect size across studies (Borenstein et al., 2010). In addition, moderator analysis and subgroup analysis were also conducted to account for the heterogeneity across the studies. Specifically, moderator analyses were conducted to investigate whether the culturally adapted intervention’s (CAI) effects varied by treatment model (e.g., motivational interviewing [MI], cognitive behavioral therapy [CBT]), dose (single session versus multiple sessions), country, participant age, gender/sex (% women/females in the sample), or the follow-up assessment timing (number of weeks after posttest). Besides an overall effect size by pooling all effect sizes from studies included in this review, we also calculated subgroup effect sizes for different types of control conditions (inactive, active) and outcomes (alcohol use, illicit drug use, unspecified substance use, and substance-use-related consequences). In addition, we assessed publication bias using the Trim and Fill method (Duval and Tweedie, 2000) and conducted sensitivity analysis by excluding effect size outliers. An effect size was considered an outlier when the upper bound of its 95% confidence interval (CI) was lower than the lower bound of the pooled effect size’s CI or the lower bound of its CI was higher than the upper bound of the pooled effect size CI (Viechtbauer and Cheung, 2010). Statistical significance of results was inferred by an alpha level of .05 when the degrees of freedom (df) were greater than or equal to four, and an alpha level of .01, when the df were below four (Tanner-Smith et al., 2016; Tipton, 2015).

Robust variance estimation in meta-regression was used for synthesizing effect sizes and conducting moderator analyses for two reasons (Hedges et al., 2010; Tanner-Smith et al., 2016). First, most of the studies included in this review reported multiple treatment outcomes for each study sample, and therefore effect sizes in this review are not independent. Robust variance estimation has advantages over other statistical methods that can also handle within-study dependence, such as generalized least squares estimation (Gleser & Olkin, 2009) and multilevel meta-analysis model (Van den Noortgate et al., 2013), because it makes no assumption about the specific form of effect sizes’ sampling distributions and requires no information about the covariate structure of dependent effect sizes (Hedges et al., 2010; Tanner-Smith and Tipton, 2014). Second, simulation studies found that robust variance estimation can yield accurate effect size estimates with as few as 10 studies (Tanner-Smith and Tipton, 2014) and get accurate moderator analysis results with 20–40 studies (Hedges et al., 2010; Tipton, 2013).

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

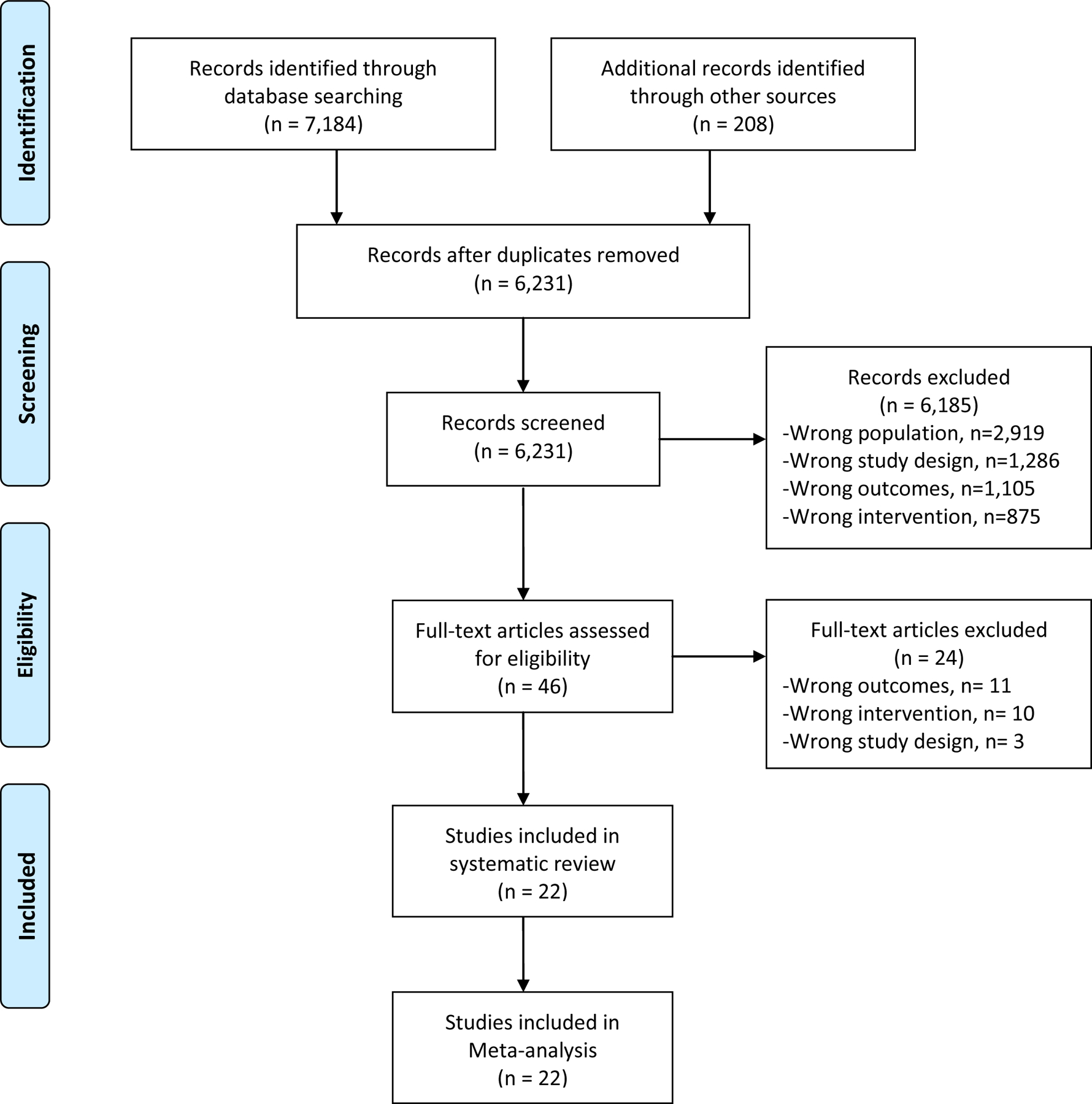

Figure 1 presents a PRISMA diagram of the steps in the search and selection process (Moher et al., 2009). After removing duplicate studies, an initial pool of 6,231 studies remained for screening; 6,185 studies were excluded based on titles and abstracts; and 24 studies were excluded in the full-text review. In total, 22 studies (25 publications) met inclusion criteria and were included in the review.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection process.

3.2. Study and Participant Characteristics

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the 22 studies in this review. The present review included a total of 5,961 participants, with individual study samples ranging from 37 to 700. All 22 studies were published in or after 2004 in peer-reviewed journals. One study (5%) was published in 2004, four studies (18%) were published between 2006 and 2010, nine studies (41%) were published between 2011 and 2015, and eight studies (36%) were published between 2016 and 2020. Approximately 40% of the studies were conducted in the US (n=9, 41%). Three studies were conducted in Russia (14%), three in China (14%), two in Kenya (9%), two in Taiwan (9%), one in Rwanda (5%), one in Poland (5%), and one in the Republic of Georgia (5%). Eight out of the nine US studies were focused on Latino/a Americans (89%) and the other study was focused on Native Americans (11%). The 13 studies conducted in non-US countries did not report samples’ racial/ethnic compositions. Of the 22 studies in this review, four studies focused on men only (18%), three studies focused on women/females only (14%), and the percent of women/females in the remaining 15 study samples ranged from 11% to 50%. Participants’ average age ranged from 26 to 50.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies under review (N=22).

| Author Year; Country; Sample Size (N) | Participant Characteristics (Mean Age; Gender/sex; Race/Ethnicity; and Any Special Characteristic); Setting | Culturally Adapted Intervention | Fidelity; Interventionist and Interventionist Training | Control Condition | Outcomes of Interest (measures); Summary of Results* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allen et al. 2011; Russia; N=441 | Mean age not reported; 0% women/females; Working age men with “hazardous and harmful drinking” in Russia; Clinic or home | Standard care (SC) + Motivational interviewing (MI) culturally adapted for Russian context: 2 initial sessions were 2 weeks apart with 2 additional sessions available upon request; Delivered in a one-on-one format | Fidelity monitored through regular supervision, which involved discussions of session audio-recordings; It was reported that MI was likely not consistently delivered to international standards; Interventionists were a psychiatrist and a psychologist who received a 3-day initial training and some further training | Inactive; SC A health check and the general health promotion feedback in the form of a letter | Past month hazardous drinking (self-report, measure NR); No significant differences were detected between the randomized groups in either the primary or the secondary outcomes at three months in the intention to treat analyses. |

| Carroll et al. 2009; US; N=436 | 32.5 yo; 11.6% women/females; Latinx Americans with substance use problems; 1.7% South American; 10.6% Central American; 49.4% Mexican; 16% American; 7.2% Cuban; 14.1% Puerto Rican; 1.0% Other Caribbean; Outpatient substance abuse treatment programs | Motivational enhancement therapy (MET) in English adapted into a Spanish-language protocol: delivered in a one-on-one format; 3 sessions over 4 weeks (.75 sessions/week) | Fidelity was monitored using audiotapes, supervision, and third-party rater systems and show high levels of adherence; Interventionists were community clinicians with 16 initial hours of training and some further practice sessions | Active; TAU: three sessions of counseling as usual delivered in Spanish; equally adapted compared to the CAI condition (both translation only). | % days abstinent from primary substance used (a self-report measure of substance use derived from the time line follow-back [TLFB] method); % positive urine specimens (urine test); Results suggest that the individual treatments delivered in Spanish were both attractive to and effective with this heterogeneous group of Hispanic adults, but the differential effectiveness of MET may be limited to those whose primary substance use problem is alcohol and may be fairly modest in magnitude. |

| Chaudhury et al. 2016; Rwanda; N=293 | 41.0 yo; 48.8% women/females; HIV-affected families in Rwanda (no substance use related inclusion criteria reported; 16% of participants reported harmful drinking at baseline); home | SC+Family Strengthening Intervention for HIV affected families culturally adapted for use in Rwanda: Delivered in group and individual format; 11 sessions over 24 weeks; Delivered in Kinyarwanda language | Fidelity not reported; Interventionists were bachelor-level counselors (training not reported) | Inactive; SC: social work support services provided through the HIV clinic. | Problematic alcohol use (Adapted Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test [AUDIT]); Reductions in alcohol use and intimate partner violence among caregivers are supported by qualitative reports of improved family functioning, lower levels of violence and problem drinking as well as improved child mental health, among the intervention group. This mixed methods analysis supports the potential of family-based interventions to reduce adverse caregiver behaviors as a major mechanism for improving child well-being. |

| Chawarski et al. 2011; China; N=37 | 36.7 yo; 19.0% women/females; Individuals eligible for methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) in Wuhan, China; Two MMT clinics in Wuhan, China | TAU+Methadone Maintenance Treatment and Behavioral drug and HIV risk reduction counseling (MMT+BDRC) culturally adapted for Chinese context: Delivered one-on-one; 13 sessions over 13 weeks (1 session/week); Delivered in Mandarin; Not technology-based | Fidelity of counselors’ adherence to the manual was monitored via regular group supervision sessions involving the study team in China, as well as via conference calls and occasional visits by the author of the BDRC manual (MCC); Four nurse counselors completed training in BDRC (consisting of several didactic workshops, case conferences and treating two closely supervised BDRC practice cases). | Inactive; TAU: MMT | Proportion of opiate positive urine tests (urine test); Participants in MMT+BDRC achieved both greater reductions of HIV risk behaviors and of illicit opiate use. |

| Cherpitel et al. 2010; Poland; N=299 | Age not reported; 14.7% women/females; “At-risk and dependent drinkers” in an emergency department in Sosnowiec, Poland | Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) culturally adapted for use in Poland: Delivered in one-on-one format; one session in total; Delivered in Polish | Fidelity monitored through audiotapes, researcher observations, and interviews of participants; Nurses’ training covered a 2-day period and included practice interventions in the emergency department, in the presence of one of the trainers; Booster training sessions were provided by study staff as needed | Active; TAU: assessment + a list of AA groups and specialized services for alcohol treatment and counseling following assessment; Likely delivered in Polish; seems to be translation only and therefore less adapted than the CAI condition. | At-risk drinking % (measure NR, possibly TLFB); No. drinking days per week (TLFB); No. drinks per drinking day (TLFB); No. maximum drinks on an occasion, last month (TLFB); No. negative consequences (Short Inventory of Problems); At 3-month follow-up, both groups showed significant decreases in drinking outcomes. No significant group difference was found. |

| Field & Caetano, 2010; US; N=537 | 29.0 yo; 11.5% women/females; Hispanic patients who were screened for an alcohol-related injury or alcohol problems at an urban Level I trauma center | TAU+Brief Motivational Interviewing culturally adapted for Hispanic population through ethnic matching: Delivered in one-on-one format; 1 session in total; Delivered in Spanish | Ten percent of interventions were randomly selected to be audiotaped which showed high levels of adherence; Community clinicians were master’s level or degreed and were certified in brief intervention following the successful completion of 3 days of training in Motivational Interviewing and 2 days of training regarding the application of Motivational Interviewing principles in the trauma care setting. | Inactive; TAU: patient handouts. | Volume per week (calculated by multiplying usual quantity of drinks per occasion by frequency of drinking); Frequency of 5 or more per occasion (“During the past 12 months, how often did you have 5 or more drinks of any kind of alcoholic beverage at one time (i.e., any combination of cans of beer, glasses of wine, or drinks containing liquor of any kind)?”); Maximum amount consumed (“Now think of all kinds of alcoholic beverages combined, that is, any combination of beer, wine, or liquor. During the past 12 months, what was the largest number of drinks that you had in a single day?”); For Hispanics who received brief motivational intervention, an ethnic match between patient and provider resulted in a significant reduction in drinking outcomes at 12-month follow-up; In addition, there was a tendency for ethnic match to be most beneficial to foreign-born Hispanics and less acculturated Hispanics. |

| Harder et al. 2020; Kenya; N=300 | 38.0 yo; 22.0% women/females; Kenyans with alcohol use problems (based on a translated three-question version of AUDIT); This study site was a tier 2 facility (primary care health center) in a county in Eastern Province, 100 kilometers East of Nairobi, Kenya. | Mobile Motivational Interviewing (MI) culturally adapted for use in Kenya: Delivered one-on-one; 1 session in total; Delivered in Kiswahili (the national language) and Kikamba (the local language); Used technology (mobile phones) | Adapted versions of the MI Interview Rating Worksheet and MI Competency and Adherence Feedback scale by Martino and colleagues [72] were used by clinicians to evaluate recordings of each other’s practical sessions during peer-to-peer sessions; The three clinicians who delivered MI had a Master’s degree in nursing, doctoral degree in clinical psychology or a medical degree, and were fluent in all three languages. They were trained over a 6-month period on how to deliver MI. | Inactive; Waitlist control | AUDIT-Consumption; The average AUDIT-C scores were nearly three points higher (difference = 2.88, 95% confidence interval = 2.11, 3.66) for waiting-list controls after 1 month of no intervention versus mobile MI 1 month after intervention. Results for secondary outcomes (difference in alcohol score for in-person MI versus mobile MI one and 6 months after MI) supported the null hypothesis of no difference between in-person and mobile MI at 1 month (Bayes factor = 0.22), but were inconclusive at 6 months (Bayes factor = 0.41). |

| Hser et al. 2011; China; N=319 | 38.0 yo; 23.8% women/females; Chinese people who were consecutively admitted to one of five participating methadone maintenance clinics (MMT); Five participating MMT clinics (3 in Shanghai, 2 in Kunming) | TAU+ Contingency management intervention culturally adapted for use in China: Delivered one-on-one; 12 sessions over 12 weeks (1 session/week); Delivered in Mandarin; Not-technology based | Procedures were intended to prevent potential tampering and ensure the proper number, probability distribution, and amount; The intervention was delivered by the clinical staff (methadone prescribers or nurses) who were trained by the senior investigators before trial implementation | Inactive; TAU: Methadone Maintenance Treatment included a physical exam, weekly urine testing for opiates, and daily methadone ingestion under supervision (after initial dosage adjustment and stabilization; No counseling sessions were offered, except that in Shanghai social workers maintained contact with patients outside MMT | Longest duration of sustained abstinence in opiate use (urine test); Total number of opiate negative samples submitted (urine test); Percentage of negative samples among total samples, % (urine test); Percentage of negative samples among submitted samples, % (urine test); Opiate use in past 30 days (Addiction Severity Index [ASI]); Relative to the treatment-as-usual (control) group, better retention was observed among the Incentives group in Kunming (44% vs. 75%), but no difference was found in Shanghai (90% vs. 86%); Submission of negative urine samples was more common among the Incentive group than the usual care (74% vs. 68% in Shanghai, 27% vs. 18% in Kunming), as was the longest duration of sustained abstinence (7.7 wks vs. 6.5 in Shanghai, 2.5 vs. 1.6 in Kunming). |

| Kirtadze et al. 2018; Republic of Georgia; N=128 | 41.2 yo; 100% women/females; 89.1% Georgian; 3.9% Russian; 0.8% Armenian; All women had injected illicit substances in the past 30 days; The research site rented for this trial was located in the central residential district of the capital city Tbilisi | Reinforcement-Based Treatment and the Women’s CoOp (RBT+WC) culturally adapted for Georgian women/females; Delivered one-on-one; 12 sessions over 6 weeks (2 sessions/week); Delivered in Georgian; Not technology-based | Fidelity not reported; The research team consisted of young women/females —project director, research assistant, three consultants, and two recreational teachers—that were trained in advance by the US research team. | Active; TAU: information booklets provided with case management only for 12 sessions giving service referrals for injection-drug-using women/females. Likely delivered in Georgian; seems to be translation only and therefore less adapted than the CAI condition. | Opioids (urine test); Benzodiazepines (urine test); Amphetamines (urine test); Cannabis(urine test); alcohol use (breathalyzer test); The findings showed that RBT+WC was not more effective than UC, although both treatments positively impacted opioid, benzodiazepine, and amphetamine/ methamphetamine use. |

| Lee et al. 2013; US; N=58 | 34.91 yo; 44.0% women/females; Latinx people with hazardous drinking tendencies; Community-based recruitment methods included advertising on Spanish-radio talk show, presenting the study at local churches and in English as a Second Language classes using “word-of-mouth” techniques, in Providence, RI | Culturally adapted motivational interviewing (CAMI) for Latinx heavy drinkers: Delivered one-on-one; 1 session in total; Delivered in English; Not technology-based | Adherence to each treatment protocol was achieved by reviewing session audiotapes during ongoing supervision and by using checklists of required MI intervention components. There was a checklist for both conditions (MI and CAMI); Interventionists were all graduate or postgraduate clinical psychology students trained for 16 hours on the description of the social contextual model of cultural adaptation, review of how each MI component was adapted, culturally relevant content, process issues in delivering the CAMI, and role plays. | Active; TAU: Motivational Interviewing (MI); delivered in English; fully non-adapted. | Drinking consequence (Drinkers Inventory of Consequences [DrInC]); Drinc_Impulse; Significant declines across both were found in heavy drinking days/month and drinking consequences (p < .001), with greater reductions for drinking consequences for CAMI at 2 months (p = .009) and continuing reductions in CAMI at 6 months. |

| Lee et al. 2019; US; N=296 | 41.1 yo; 37.5% women/females; Heavy drinking Latinx people; Race: .7% Asian; 13.9% Black; White: 21.3%; 2% American Indian/Alaskan Native; 1.7% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander; 60.5% More than one race; Ethnicity: 45.3% Puerto Rican; 15.2% Dominican; 9.8% Central American; 17.9% South American; 1.4% Mexican; 2.0% Cuban; 0.7% Spanish; 7.7% More than one ethnicity. | Culturally adapted motivational interviewing (CAMI) for Latinx heavy drinkers: Delivered one-on-one; 1 session in total; Delivered in English/Spanish based on participant’s preference; Not technology-based | Audiotapes were reviewed during supervision sessions by the PI and the study therapist and 66% of all sessions were coded using the MITI; 11 study therapists were Master’s level graduate students (social work, psychology) who received 16 hr of training in MI (including role plays and demonstration of MI principles), and an additional 16 hr learning the two treatments. | Active; TAU: Motivational Interviewing (MI); Delivered in English/Spanish based on participant’s preference; seems to be translation only and therefore less adapted than the CAI condition. | % heavy drinking days (TLFB); Drinking consequence (DrInC);; Both conditions showed significant reductions in percent heavy drinking days and frequency of alcohol-related consequences through 12-month follow-up when compared with baseline; reductions were not significantly different by condition. Acculturation moderated treatment condition effect on alcohol-related problems at 3 months (d .22, 95% CI [.02, .41]); less acculturated individuals experienced less frequent consequences of drinking after CAMI than MI (d .34, 95% CI [.60, .08]). Discrimination moderated condition effect on frequency of alcohol-related consequences at 3 months (d .17, 95% CI [.33, .01]); individuals with higher levels of baseline discrimination had less frequent consequences after CAMI than MI (d .20, 95% CI [.39, .01]). |

| Li et al. 2013; China; N=179 (clients) N=41 (providers) | 37.41 yo; 34.66% women/females; Service providers and clients in methadone maintenance treatment clinics in China; Six methadone maintenance therapy clinics (MMT) in Sichuan, China | SC+Methadone Maintenance Treatment (MMT) care culturally adoptee for Chinese context: Delivered in groups to providers and delivered one-on-one to clients; For providers 3 sessions over 3 weeks (1 session/week) and for clients 2 sessions in total; Delivered in Mandarin; Not technology-based | Clients were given a journal to document their experience, including date, time, and what they liked or disliked about the contents and formats of each session; Researchers conducted brief interviews to seek clients’ opinions about the sessions and areas to be improved; Service providers recruited from the intervention clinics received three group sessions in three consecutive weeks; Each session was about 90 minutes in length and conducted with a group of 5–7 providers at each clinic | Inactive; SC: MMT | Heroin use (urine test); Significant intervention effects for providers were found in improved MMT knowledge, provider-client interaction and perceived clinic support. For clients, better improvements in drug avoidance self-efficacy and reduced concurrent drug use were observed for the intervention compared with the standard care group |

| Liu et al. 2011; Taiwan; N=616 | 41.4 yo; 0% women/females; Taiwanese men with “unhealthy alcohol use” admitted to medical or surgical wards in a medical center in Taipei; Interventions took place either in an interview room or at the bedside in a medical ward in Taipei and second session could take place either during or after hospitalization | SC+Brief Intervention (BI) culturally adapted for use in Taiwan: Delivered one-on-one; 2 sessions over 1 week (2 sessions/week); Delivered in Mandarin; Not technology-based | Researchers provided weekly supervision to prevent drift; Interventionists completed a checklist at the end of each session, recording components of the intervention delivered; The interventionists were social workers who received 5 days of skills-based training in administering the intervention, using role-playing and general skills training techniques | Inactive; SC: medical care | Drinks in the previous 3 months (TLFB); Drinking days in the previous 3 months (TLFB); Days of heavy drinking (>5 drinks) episodes in the previous 3 months (TLFB); alcohol problems in the previous 3 months (Quick Drinking Screen [QDS]); no. days hospitalized in the previous 3 months (QDS); accident and emergency visits in the previous 3 months (QDS); Based on intention-to-treat analyses, the intervention group consumed significantly less alcohol than the control group among both unhealthy drinkers and the subgroup of alcohol-dependent participants over 12 months, on both 7-day and 3-month assessments. Adjunctive analyses of only those who completed all assessments found that total drinks consumed did not remain significant. |

| Moore et al. 2016; US; N=29 | 42.7 yo; 0% women/females; Heavy drinking men/male Latino day laborers; 7% American; 69% Mexican; 21% Central American; 3% South American; Between October and December 2012, 66 participants were contacted by distributing flyers at public places where day laborers look for work | Motivational enhancement therapy (MET) and strengths-based case management (SBCM) culturally adapted for Latinx men: Delivered one-on-one; 3 sessions over anywhere from 3 to 6 weeks (.5–1 session/week); Delivered in Spanish; Not technology-based | Fidelity for the RCT was not measured; Interventionists were volunteer promotors, all primarily Spanish-speaking Latina immigrants with a range of 3–8 years of experience as health promoters; Trained for 16 hours by bilingual psychologists and received further training via biweekly supervision | Active; TAU: feedback about alcohol use administered once by a trained, Spanish speaking research assistant immediately after the baseline assessment; seems to be translation only and therefore less adapted than the CAI condition. | Number of drinks consumed per week (AUDIT); Alcohol problems (AUDIT); Harmful drinking (AUDIT); Binge drinking (AUDIT); Alcohol related measures improved in both groups over time with no statistically significant differences observed at any of the time points. However the comparative effect size of MET/SBCM on weekly drinking was in the large range at 6-weeks and in the moderate range at 12-weeks. Post hoc analyses identified a statistically significant reduction in number of drinks over time for participants in the intervention group but not for control group participants. Despite the extreme vulnerability of the population, most participants completed all sessions of MET/SBCM and reported high satisfaction with the intervention |

| Ornelas et al. 2019; US; N=121 | 47.8 yo; 0% women/females; Heavy drinking men/male Latino laborers; 65.3% Mexican; 26.5% Central American; 8.3% Other; Men waiting for work opportunities at a day labor worker center in Seattle, Washington were approached and screened for eligibility by promotors | The Vida PURA (Puede Usted Reducir su consumo de Alcohol) [Pure Life (You can reduce your alcohol use)] based on screening and brief intervention theory and culturally adapted for Latinx context: Delivered one-on-one; 1 session in total; Delivered in Spanish; Not technology-based | Ongoing supervision and evaluation of intervention fidelity using the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Tool (MITI); Interventionists were Spanish-speaking promotors; Several days of training included Training included an overview of alcohol-related disorders and disease, basic information about alcohol use, including what is considered a “standard drink,” AUDIT risk levels, and National Institute for Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) guidelines for unhealthy alcohol use | Active; SC: information about local agencies providing substance use education, counseling, medical care, and referrals to in-patient treatment; Likely delivered in Spanish; seems to be translation only and therefore less adapted than the CAI condition. | Total AUDIT; Drinks per drinking day (TLFB); Drinking days in 14 days (TLFB); Heavy episodic drinking (TLFB); Both the intervention and control groups reduced their alcohol-related behaviors over time, but there were no significant differences between the groups. |

| Papas et al. 2011; Kenya; N=75 | 37.07 yo; ~50% women/females (There were six gender-stratified cohorts, half of them were women/females); Kiswahili-speaking HIV-infected outpatients with hazardous or binge drinking); A large HIV outpatient clinic in Eldoret, Kenya | Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) culturally adapted for Kenyan context: Delivered in groups; 6 sessions over 6 weeks (1 session/week); Delivered in Kiswahili; Not technology-based | All CBT group sessions were videotaped and monitored weekly by RP, with translational support provided as needed. Fifty percent of sessions with men/males and women/females, respectively (n=18 sessions), were randomly selected, translated into English, with random back translational verification, and rated by two highly experienced YACS [Yale Adherence and Competence Scale] raters from the Yale Psychotherapy Development Center; The two counselors (one man/male, one women/females, one HIV-infected) possessed high school and psychological counseling diplomas, and received 175 and 300 hours, respectively, of total training/supervision time prior to the trial | Active; SC (routine primary medical care in the AMPATH clinic [which provides HIV care]; likely delivered in Kiswahili. seems to be translation only and therefore less adapted than the CAI condition. | Percent drinking days (adapted TLFB); Drinks per drinking day (adapted TLFB); Effect sizes of the change in alcohol use since baseline between the two conditions at the 30-day follow-up were large (d=.95, p=.0002, mean difference=24.93 (95% CI: 12.43, 37.43) percent drinking days; d=.76, p=.002, mean difference=2.88 (95% CI: 1.05, 4.70) DDD). Randomized participants attended 93% of the 6 CBT sessions offered. Reported alcohol abstinence at the 90-day follow-up was 69.4% (CBT) and 37.5% (usual care). |

| Paris et al. 2018; US; N=92 | 42.9 yo; 32.6% women/females; Spanish speakers with cocaine, marijuana, opioid, alcohol, or other stimulant abuse or dependence based on DSM-IV; 71.7% Puerto Rican; 4.3% American; 2.2% South American; 8.7% Mexican; 9.8% Central American; 3.3% Other; Recruited participants from individuals seeking treatment at 1 of 3 settings offering outpatient services to Latinos in the New Haven, Connecticut, area | CBT4CBT+TAU culturally adapted for for Spanish-speaking individuals: Delivered one-on-one and in groups; 7 sessions over 8 weeks (.875 sessions/week); Delivered in Spanish; Uses technology (web-based) | Fidelity not reported; Intervention was counseling and web-based | Inactive; TAU: standard care at each of the clinics, which typically consisted of supportive counseling delivered via weekly group or individual sessions, with access to other services as needed; For all conditions, researchers monitored receipt of medical, legal, psychological, and social support services both within and out- side the program at each assessment visit. | % days abstinent from primary drug during treatment (Substance Use Calendar); % urine specimens negative for all drugs; % positive breathalyzer tests; For the primary outcome (change in frequency of primary substance used), there was a significantly greater reductions for those assigned to Web CBT, which were durable through the 6-month follow-up. The knowledge test indicated significantly greater increases for those assigned to Web CBT. |

| Pearson et al. 2019; US; N=73 | Age not reported; 100% women/females; Native American women/females with heavy drinking/illicit drug use and signs of PTSD; Two rural Pacific Northwest behavioral health clinics: a tribally-operated clinic located on the reservation and a privately-operated nonprofit clinic located in a town adjacent to the reservation | Culturally Adapted Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) culturally adapted for Native American context: Delivered one-on-one; 13 sessions in total; Length of intervention not reported; Delivered in English; Not technology-based | Supervision calls included monitoring of weekly symptom measures, review of audio recordings of intervention sessions, and group discussion on case conceptualization, delivery of strategies, and clinical challenges; Counselors successfully completed 1 week of training before delivering CPT and attended weekly supervision meetings with a clinical psychologist with CPT expertise throughout the study duration | Inactive; Waitlist control | Alcohol problems (Alcohol Short Inventory of Problems); Alcohol use % (Drug Use Frequency Measure); Substance use disorder (The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for DSM-IV); Among immediate intervention participants, compared to waitlist participants, there were large reductions in PTSD symptom severity, high-risk sexual behavior, and a medium-to- large reduction in the frequency of alcohol use. CPT appears to improve mental health and risk behaviors, suggesting that addressing PTSD may be one way of improving HIV-risk related outcomes. |

| Robles et al. 2004; US; N=557 | Age not reported; 10.6% women/females; Adults in Vega Baja, Puerto Rico, who had injected drugs in the past 30 days; Recruitment sites in Vega Baja included locate areas where drugs were procured (copping areas) and injected (shooting galleries), as well as prostitute strolls and other sites (hangouts) frequented by drug users; Potential subjects were accompanied to an assessment facility (“study site”) also in Vega Baja | TAU+Combined counseling and case management behavioral intervention culturally adapted for Puerto Rican context: Delivered one-on-one; 6 sessions over 6 weeks (1 session/week); Delivered in Spanish; Not technology-based | Case manager with a bachelor’s degree in social work and training in the intervention protocol met with participants after each counseling session to review and evaluate the session in terms of lessons learned and to provide assistance in overcoming any impediments (e.g. care of children, legal problems) encountered by participants to attending the next session; All six sessions were conducted by a registered nurse specially assigned to this intervention, with intensive training in motivational interviewing strategies. | Inactive; TAU: counseling for HIV testing, safe needle use and safe sex skills, HIV testing for those who consented, and a second session that focused on counseling post-test as well as drug treatment or health care referrals if interested. | Continued injection drug use (revised and culturally adapted versions of the Risk Behavior Assessment [RBA] and Risk Behavior Follow-up Assessment [RBFA]); Subjects in the experimental arm were significantly less likely to continue drug injection independent of entering drug treatment, and were also more likely to enter drug treatment. Subjects in both arms who entered drug treatment were less likely to continue drug injection. Among subjects who continued drug injection, those in the experimental arm were significantly less likely to share needles. |

| Samet et al. 2015; Russia; N=700 | 30.1 yo; 40.7% women/females; Russian people who are HIV positive and have at-risk drinking tendencies; Recruited from four clinical in-patient and out-patient HIV and addiction sites in St Petersburg, Russia; Interventions took place at Botkin Infectious Disease Hospital in St Petersburg | HERMITAGE based on Healthy relationships intervention (HRI) and Motivational interviewing (MI) and adapted for Russian context: Delivered one-on-one and in groups; 5 sessions in total; Three group sessions took place in a one week time frame, with an individual session preceding and following the week of group sessions; Delivered in Russian; Not technology-based | Adherence was monitored by observation of the sessions, which occurred for 10% of randomly selected participants using audiotapes made across all sessions, the quality and coverage of material in the session components were scored as low, medium or high, and participants gave survey feedback; Observations indicated high adherence to curriculum, good capacity of interventionists to implement the program and high engagement of participants in program sessions; Interventions were led by peer-professional teams who received structured training on both conditions and regular supervision and monitoring | Active; SC: five-session control program including two individual and three group sessions focused on stress reduction, social support and good nutrition for HIV-infected individuals; These group sessions were similarly led by peer-professional teams and provided education and skills building activities, as well as social support. Likely delivered in Russian; seems to be translation only and therefore less adapted than the CAI condition. | Average drinks per day (TLFB); Number of heavy drinking days (TLFB); Both groups decreased unsafe behaviors, although no significant differences were found between groups. |

| Tsai et al. 2009; Taiwan; N=275 | 49.64 yo; 18.19% women/females; Taiwanese inpatients with hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption; Eighteen units were selected from surgery units (e.g., traumatic, orthopedic, and neurological unit) and medical units (e.g., gastro- intestinal and psychiatric unit) at a medical center in northern Taiwan | Brief Intervention (BI) culturally adapted for use in Taiwan; Delivered one-on-one; 1 session in total; Delivered in Mandarin; Not technology-based | Fidelity not reported; The 2 RA [nurses] were trained for 1 year to use the AUDIT for alcohol assessments, to consult patients about alcohol use, and to enhance their communication skills | Inactive; No treatment. | Alcohol use quantity (AUDIT); Alcohol use symptoms of dependence (AUDIT); AUDIT total; Alcohol use disorders identification test scores decreased significantly in both groups at 6 months after the intervention, but did not differ significantly between the 2 groups. However, 12 months after the brief alcohol intervention, experimental subjects’ AUDIT scores were significantly better than those of the control group. |

| Wechsberg et al. 2012; N=100 | 25.9 yo; 100% women/females; Russian women/females between 18 and 30 years of age who self-reported injection drug use in the past year and had been undergoing Leningrad Regional Center of Addictions (LRCA) substance abuse treatment for more than 4 days; Leningrad Regional Center of Addictions (LRCA) | Woman-Focused Intervention based on Empowerment theory and social cognitive theory culturally adapted to Russian context; Delivered one-on-one; 2 sessions over 2 weeks (1 session/week); Delivered in Russian; Not technology-based | A multilingual project director from LRCA served as a senior team member and conducted quality assurance and observations; Interventionist was a staff psychologist trained by the principal investigator | Active; The equal-attention control group received a two-session intervention adapted from the Colorado State University Extension Nutrition Program’s “Eat Well for Less” (EWFL) curriculum; Likely delivered in Russian; seems to be translation only and therefore less adapted than the CAI condition. | Mean days injected heroin (Russian adapted Revised Risk Behavior Assessment [RRBA]); Cocaine use (RRBA); Heroin and cocaine use (RRBA); Marijuana use (RRBA); Ecstasy use (RRBA); Crack/cocaine use (RRBA); Jeff (ephedrone) use (RRBA); At 3-month follow-up, both groups showed reduced levels of injecting frequency. However, participants in the Woman-Focused intervention reported, on average, a lower frequency of partner impairment at last sex act and a lower average number of unprotected vaginal sex acts with their main sex partner than the Nutrition condition. |

Note. yo= years old.

Fourteen studies measured alcohol use outcomes, five studies reported illicit drug use outcomes, four studies measured substance use outcomes in general without specifying the type of the substance used, and four studies measured substance-use-related consequences. With regards to outcomes reporting, nearly three-quarters of the studies relied on self-report measures only (n=16, 73%), three studies used only biomedical tests (e.g., urine and breathalyzer tests) (14%), and three studies used both self-reported measures and biomedical tests (14%). Ten studies utilized active controls (45%) and twelve studies employed inactive controls (55%). Examples of active control interventions include MI with no cultural adaptation and customized brief feedback after assessment. Examples of inactive controls include waitlist control, SC alone (compared with SC + culturally adapted MI), and TAU alone (compared with TAU + SBIRT).

3.2.2. CAI Characteristics

Nearly 60% of the CAIs included in this review (n=13, 59%) were based on MI, and three of these MI-based studies focused on culturally adapted SBIRT. Four studies focused on CAIs that were based on cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) (18%) and one study focused on contingency management intervention (5%). Eight of the 22 reviewed studies (36%) focused on CAIs that were designed to reduce substance use among HIV-infected individuals/families or to prevent substance use and other HIV risk behaviors among high-risk populations. Three of the eight HIV-related CAIs were based on CBT, two were based on MI, one was based on empowerment theory and social cognitive theory, one was a family strengthening intervention, and one was a reinforcement-based treatment plus Women’s CoOp. The CAIs in almost a third of the reviewed studies consisted of only one session (n=7, 32%), six CAIs had two to four sessions (27%), four CAIs had five to seven sessions (18%), and five CAIs had 11–13 sessions (23%). All CAIs appeared to be fully or partially manualized. The majority of the CAIs in this review were delivered in a one-on-one format (n=17, 77%), one was delivered in a group format (5%), and four were delivered in a combination of individual and group formats (18%). Three studies (14%) reported the incorporation of intervention content/components related to discrimination and acculturation stress in the cultural adaptation (Lee et al., 2019, 2013; Moore et al., 2016). Three of the 22 studies (14%) employed technology in the delivery of the CAIs (Harder et al., 2020; Hser et al., 2011; Paris et al., 2018).

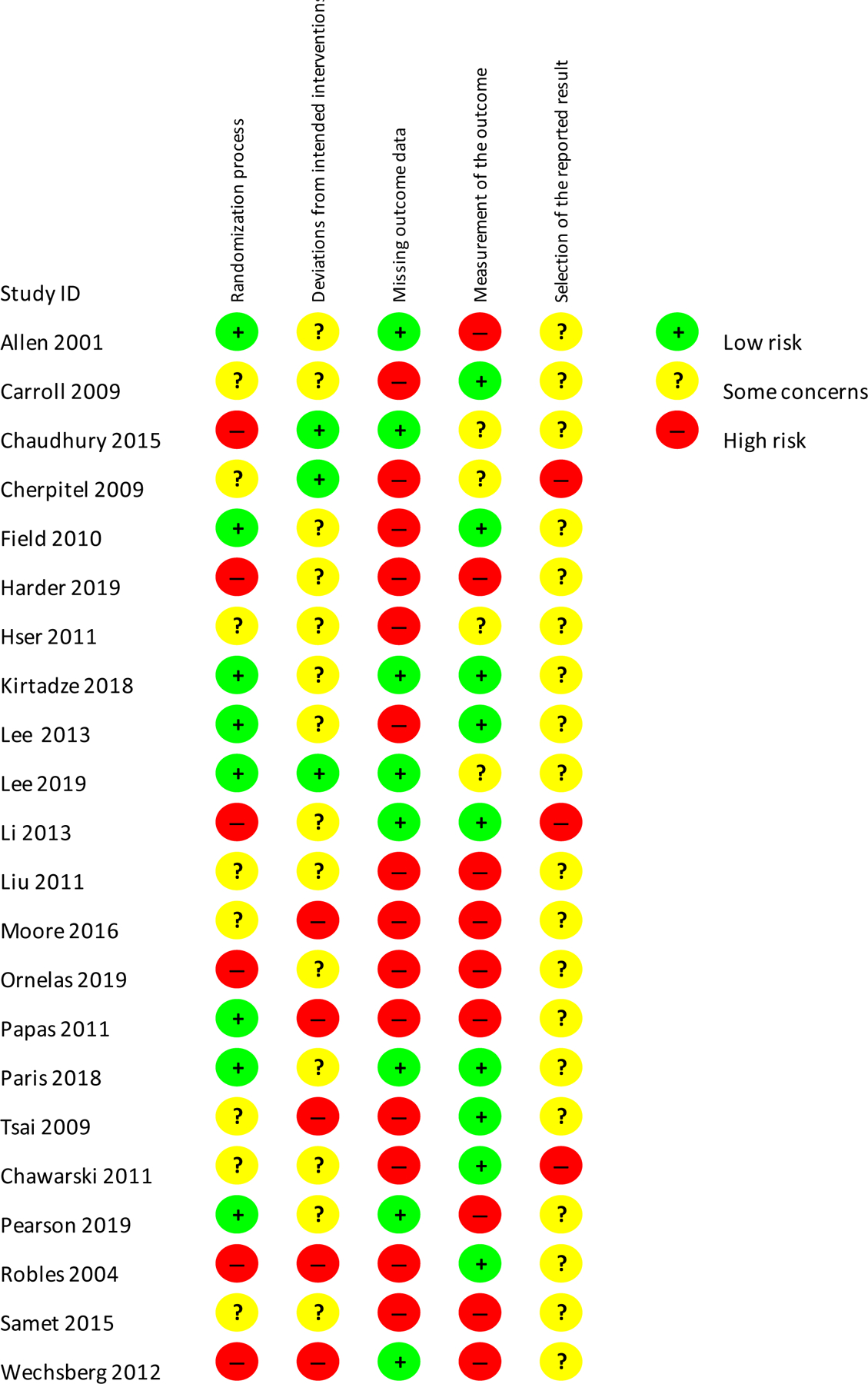

3.3. Risk of Bias Assessment Results

Figure 2 presents the risk of bias assessment results graphically. Eight (36%) of the 22 studies in this review were rated low risk in the randomization process because (a) they described a proper method of random sequence generation (e.g., using random number tables, computer random number generators, or shuffling cards), (b) the allocation sequence was concealed until participants were enrolled and assigned to interventions, and (c) there were no significant baseline differences between intervention groups. Eight (36%) and six (28%) studies were determined to raise some concerns and have high risk in the randomization process respectively, because they did not meet or provide a clear report on one or more of the aforementioned criteria.

Fig. 2.

Risk-of-bias summary.

Three studies (14%) were rated as having a low risk for deviations from the intended intervention (failure to implement the trial or intervention protocols as intended or non-adherence by participants to their assigned intervention) because (a) participants, research staff, and interventionists were likely to be unaware of participants’ intervention assignment, (b) there was unlikely any deviation from the intended intervention that arose because of the trial context (e.g., the informed consent leading control participants feel unlucky and therefore seek the experimental intervention), and (c) appropriate analysis was used to estimate the effect of assignment to intervention (e.g., intention-to-treat analysis). More than 60% of the studies included in this review (n=14, 63%) were considered to raise some concerns about potential deviation and 5 studies (23%) were rated high risk in terms of deviations from the intended intervention, mostly because blinding is usually not feasible in social science and some studies did not adhere to the intention-to-treat principle when estimating intervention effects.

Eight (36%) studies were judged to have a low risk in regard to missing outcome data, because they had low attrition (<10%) and/or there was evidence that the result was not biased by missing outcome data (e.g., missing completely at random, participant dropouts were caused by reasons unlikely to be related to the true value of the outcome). In contrast, the other 14 studies (64%) had more than 10% attrition and there was no evidence suggesting that the result was not biased by missing outcome data, and therefore were considered to have a higher risk with regards to the bias that missing outcome data can exert on study interpretability.

More than 40% of the included studies (n=9, 41%) were rated low risk regarding bias in the measurement of outcomes for (a) using appropriate methods of measuring outcomes, (b) the measurement was unlikely to have differed between intervention groups, and (c or the outcome assessment was not likely to be influenced by outcome assessors (e.g., participant self-report or clinicians giving biomedical tests) knowledge of the intervention assignments (e.g., using biomedical tests to corroborate self-report). Four studies (18%) were judged to raise some concerns in the measurement of the outcome because the outcome assessors were the participants (i.e., relied on self-report measures) who were not blinded to their intervention assignment. Nine studies (41%) were rated high risk in measurement of the outcome mostly because they relied on self-report and the outcome assessment could or were likely influenced by knowledge of participants’ intervention assignments.

The majority of the studies in this review (n=19, 86%) were considered to raise some concerns in the selection of the reported results because there was not sufficient information to determine whether data was analyzed in accordance with a pre-specified analysis plan. Some studies did not have or provide pre-registered study protocols, while other studies’ pre-registered protocols did not specify a data analysis plan. Three studies (14%) did not report results on all outcome variables listed in the publication or study protocols and therefore were rated high risk in the selection of the reported results.

3.4. Meta-Analysis Results

Table 2 presents the overall effect size estimate and the subgroup effect size estimates for different types of control conditions and outcomes. The overall effect size estimate representing the effect of CAIs on substance use and related consequences, with 120 effect sizes from 22 studies, was d= .23, which was statistically significant (95% CI= .12, .35) and favored CAIs. The effect size for comparing CAIs with inactive controls was .31 and statistically significant (CI=.14, .48) and favored CAIs. The effect size for comparing CAIs with active controls was .14, which favored CAIs but was not statistically significant (CI=-.02, .29). The effect size for CAIs’ effects on alcohol use was .25 and statistically significant (CI=.08, .43). The effect sizes for illicit drug use, unspecified substance use outcomes (without differentiating alcohol and illicit drug use), and substance-use-related consequences were .35, .22, and .02 respectively and were not statistically significant (CIdrug=-.30, 1.00; CIsubstance=-.17, .62; CIconsequences=-.11, .16), potentially due to low power as evidenced by the low degrees of freedom (df<3). Table 3 shows the moderator analysis results. Moderator analysis revealed that CAIs’ effects might not differ significantly as a function of the treatment model, dose, country, follow-up assessment timing, participant age, or gender/sex. The Trim and Fill publication bias assessment results showed that the estimated number of missing studies due to publication bias was 17, suggesting that there was publication bias (p < .001). The pooled effect size estimate that has been adjusted for publication bias was slightly smaller than the unadjusted pooled fixed-effect estimate (dunadjusted = .15, SE= .01, p <.001, CI= .12, .18; dadjusted = .12, SE= .01, p <.001, CI=.09, .15), suggesting that the publication bias was moderate. Sensitivity analyses yielded comparable effect size and moderator analysis results when effect size outliers were excluded. Individual effect sizes from each study can be obtained from the first author.

Table 2.

Overall and subgroup effect size estimates

| K1 | K2 | d | SE | df | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Effect Size | 120 | 22 | .23 * a | .05 | 16.70 | .000 | .12, .35 |

| Control Type | |||||||

| Inactive Control | 54 | 12 | .31 * | .07 | 8.48 | .003 | .14, .48 |

| Active Control | 66 | 10 | .14 | .07 | 7.10 | .074 | −.02, .29 |

| Comparing more fully adapted CAIs with partially adapted (translated) active control | 59 | 8 | .17 | .08 | 5.46 | .098 | −.04, .38 |

| Outcome | |||||||

| Alcohol Use | 69 | 14 | .25 * | .08 | 10.56 | .008 | .08, .43 |

| Illicit Drug Use | 27 | 5 | .35 | .15 | 2.02 | .146 | −.30, 1.00 |

| Unspecified Substance Use | 9 | 4 | .22 | .10 | 2.09 | .139 | −.17, .62 |

| Consequences | 15 | 4 | .02 | .04 | 2.57 | .593 | −.11, .16 |

Note. K1=number of effect sizes, K2=number of studies, d=small sample corrected Hedge’s g, SE=standard error, df=degree of freedom, CI=confidence interval, SBI= Screening and Brief Intervention, SBIRT=Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment.

p <.05 when df >= 4, * p <.01 when df < 4.

Q[df = 119]= 224.42, p < .001, I2= 46.97%

Table 3.

Moderator analysis results

| N | Coefficient | SE | t | df | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up Assessment Timing | 22 | .004 | .003 | 1.28 | 7.71 | .238 |

| Age | 18 | .0001 | .019 | .006 | 3.20 | .996 |

| % of Female Participants | 22 | .003 | .004 | .78 | 3.63 | .481 |

| Single Session (versus multiple sessions) | 22 | −.21 | .18 | −1.16 | 4.78 | .299 |

| Treatment Model | 22 | |||||

| Motivational Interviewing (Reference) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| SBI/SBIRT | - | .34 | .27 | 1.25 | 3.67 | .285 |

| Cognitive Behavioral Therapy | - | .02 | .21 | .08 | 3.64 | .937 |

| Contingency Management | - | −.43 | .27 | −1.58 | 2.07 | .250 |

| HIV-related Intervention | - | −.18 | .24 | −.76 | 2.95 | .503 |

| Country | 22 | |||||

| US (Reference) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Russia | - | −.15 | .09 | −1.79 | 2.89 | .174 |

| China | - | .65 | .22 | 2.94 | 1.54 | .134 |

| Kenya | - | .61 | .24 | 2.51 | 2.02 | .127 |

| Taiwan | - | −.19 | .12 | −1.53 | 2.72 | .233 |

| Rwanda | - | .09 | .25 | .34 | 4.48 | .746 |

| Poland | - | −.31 | .20 | −1.57 | 2.96 | .216 |

| Republic of Georgia | - | −.16 | .35 | −.46 | 3.93 | .671 |

Note. N=number of studies with data available for each moderator. Follow-up assessment timing, age ,and % of female participants were mean centered. SE=standard error, df=degrees of freedom, CI=confidence interval.

p <.05 when df >= 4, * p <.01 when df < 4

4. Discussion

The existing RCTs provide suggests that CAI is a promising approach for reducing substance use and related consequences (overall effect size d=.23, CI= .12, .35). Results showed that CAIs were significantly more efficacious than inactive controls (d=.31, CI=.14, .48) (e.g., culturally adapted MI + SC vs SC alone, Spanish CBT4CBT + TAU vs TAU alone, Culturally Adapted Cognitive Processing Therapy vs waitlist control). When CAIs were compared with active controls (e.g., culturally adapted MI vs. standard MI alone, culturally adapted MI vs counseling as usual) the effect size favored CAIs but did not reach statistical significance (d=.14, CI=-.02,.29). It is possible that the non-significant active control effect size was indicative of the need to improve CAIs’ treatment effects and we provide some suggestions for this in the Directions for Future Research section below. Another possible explanation of the non-significant active control effect size was related to the fact that the majority of the active control interventions were linguistically translated (all but Lee et al., 2013), thus were already partially culturally adapted (Valdez et al., 2018), therefore potentially decreasing the active control effect size.

Instead of only focusing on studies that compared CAIs with totally non-adapted control interventions, we followed the approach of prior CAI reviews (e.g., Steinka-Fry et al., 2017; Valdez et al., 2018) which included CAI studies with translated control interventions, to avoid excluding too many studies that may provide important evidence on CAIs. In addition, comparing more fully adapted interventions with less adapted interventions could still provide important implications for CAI research. Accordingly, we conducted an ad hoc analysis to estimate the effect size for comparing more fully adapted interventions with partially adapted (translated only) control interventions. The effect size was not statistically significant but favored more fully adapted interventions (d=.17, CI=-.04,.38), suggesting that cultural adaptation may increase the treatment effect over and above translation alone. Moreover, this finding was based on only eight studies, so more research on this question is needed.

With regards to the subgroup effect sizes for different substance use outcomes (alcohol use d=.25, illicit drug use d=.35, unspecified substance use d=.22, consequences d=.02) all favored CAIs. However, with the exception of the alcohol use effect size, none of the other subgroup effect sizes reached statistical significance, possibly due to the limited number of studies in each subgroup resulting in low power. For example, only four out of the 22 studies examined CAI’s effects on substance-use-related consequences, resulting in a df of 2.57. Moderator analyses yielded preliminary findings suggesting that CAI’s efficacy did not vary by the chosen moderators for this analysis: treatment model, dose, follow-up assessment timing, participant’s age, gender, or country, but this finding might be underpowered as indicated by df ranging from 1.54 to 7.71. We encourage future systematic reviews and meta-analyses on culturally adapted substance use interventions to replicate these analyses and to examine additional potential treatment moderators when there are more RCTs in this field that can provide greater statistical power and allow more definitive conclusions about the subgroup effect sizes and treatment moderators. Consistent with previous reviews on culturally adapted substance use interventions (Barrera et al., 2013; Hernandez Robles et al., 2018; Leske et al., 2016; Manuel et al., 2015; Steinka-Fry et al., 2017a; Valdez et al., 2018), the present review found that there is a shortage of high-quality research in this area.

4.1. Cultural Adaptation Approach

CAIs for substance use among adults generally used one of three approaches to cultural adaptation (Table 4). The first, “translation” was to translate the original intervention protocol and deliver it in a different language without incorporating additional social or cultural components (used by Carroll et al., 2009). Translation is a form of cultural adaptation because language is a key carrier of culture (Valdez et al., 2018), but it is considered a partial adaptation because it may not reflect cultural values and beliefs (Resnicow et al., 1998). The second, “ethnic matching” focuses on matching the ethnicity between patient/client and provider (used by Field and Caetano, 2010). Providers who share the same ethnicity with the client may be more likely to understand and introduce cultural-specific values, perceptions, norms, and attitudes related to substance use (Field and Caetano, 2010; Lee et al., 2019).

Table 4.

Adaptation methods and content

| Author Year | Adaptation Method and Content |

|---|---|

| Allen et al. 2011 | “An adaptation of MI [motivational interviewing] was developed for the Russian context.” Adaptation method and content were not reported (NR). Translation of MI to Russian is likely. |

| Carroll et al. 2009 | Translation of motivational enhancement therapy (MET) to Spanish. Translation methods NR. |

| Chaudhury et al. 2016 | Family Strengthening Intervention for HIV affected families culturally adapted for use in Rwanda. Adaptation method: Qualitative data and community-based participatory methods (e.g., community advisory board input) informed the adaptation and to “ensure that the intervention targeted relevant problems manifest in Rwandan children and families and built on local strengths.” Adaptation content: Main components of the adapted HIV family intervention included (1) Psychoeducation to address misconception about HIV and to destigmatize it; (2) supports parents by encouraging strong parenting skills (kurera neza) and to recognize community supports (ubufasha abaturage batanga); (3) addresses caregiver fears and concerns; (4) builds a family narrative to build a sense of perseverance (kwihangana) and self-esteem (kwigirira ikizere) in children and improve family unity (kwizerana ) and communication; (5) helps families to think about the social, medical, and community resources available to them and uses family discussions to deepen family communication, trust and unity (kwizerana) so that they can start addressing problems; (6) takes a public health approach to care (Betancourt et al., 2011). Translation to Kinyarwanda language. |

| Chawarski et al. 2011 | Methadone Maintenance Treatment and Behavioral drug and HIV risk reduction counseling (MMT+BDRC) culturally adapted for Chinese context. Adaptation method and content NR. |

| Cherpitel et al. 2010 |

Adaptation method: Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) training materials were “translated and adapted for use in Poland, based on information obtained from an earlier focus-group study of reasons for drinking and barriers to change among dependent and at-risk drinkers previously identified in the same ED [emergency department].” Adaptation content NR. Intervention was delivered in Polish. |

| Field & Caetano, 2010 | Ethnic matching between clinicians and patients (Hispanic clinician – Hispanic patients). Assessment and MI were conducted in Spanish. |

| Harder et al. 2020 | Mobile MI was culturally adapted for use in Kenya and delivered in Kiswahili (the national language) and Kikamba (the local language). Adaptation method and content NR. |

| Hser et al. 2011 | Contingency management intervention culturally adapted for use in China. Adaptation method: “To adapt a motivational incentives intervention for Chinese settings, we conducted formative research to solicit feedback and suggestions from local providers and patients on the feasibility and acceptability of the research protocols. Participants expressed enthusiasm for the study and provided constructive suggestions for finalizing protocols.” Adaptation content NR. Translation to Chinese is likely. |

| Kirtadze et al. 2018 |

Adaptation method: Through a community based participatory approach (CBPR) (e.g., Community Advisory Board + Beneficiary Advisory Board), Reinforcement Based Treatment (RBT) and the Women’s CoOp (WC) (original version and other adapted version such as the WC South Africa and Russian) were adapted through in-depth individual interviews and focus group interviews with women who inject drugs and providers of health services. The resulting intervention (RBT+WC) was then pretested and further refined in a pilot trial. Adaptation content: e.g., “stress management adapted to Georgian culture”, “given HCV (hepatitis C virus) prevalence in Georgia, and use of local drugs such as “vint” and “jeff” and buprenorphine,” original materials were rearranged and new materials were added (Jones et al., 2014). RBT+WC was delivered in Georgian. |

| Lee et al. 2013 | Culturally adapted motivational interviewing (CAMI) for Latina/o heavy drinkers. Adaptation method: CBPR (community advisory board) and focus groups to identify social processes underlying the relationship between acculturation and heavy drinking among Latina/o immigrants. The Rounsaville and Carroll’s stage model of behavioral therapies research (Onken et al., 2014; Rounsaville et al., 2001) and Lau’s framework for cultural adaptations of evidence-based treatments (2006) were followed. Adaptation content: “The CAMI was adapted in three main ways. First, a MI element, establishing rapport, was augmented by inviting participants to discuss their social contexts, including reasons for U.S. immigration. Second, the CAMI included culturally relevant content, including ethnic-specific drinking norms, that is, information on how the participant’s weekly alcohol consumption compared with Latinxs of the same gender and age. Feedback on consequences specific to heavy drinking for Latinxs, that is, higher rates of cirrhosis mortality and of motor vehicle crashes, was also provided. The CAMI also introduced a new treatment module that emphasized unique social risk factors for heavy drinking, such as isolation, marginalization, discrimination, acculturation stress, economic disadvantage, and lack of access to job opportunities.” CAMI was delivered in English or Spanish depending on the participant’s preference. |

| Lee et al. 2019 | Same as Lee et al. 2013. |

| Li et al. 2013 | A culturally adapted intervention targeting methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) service providers and clients in China (i.e., MMT CARE intervention). Adaptation method: two survey studies informed the adaptation. One was a survey with MMT providers about provider-client interactions (Li et al., 2012) and the other was a survey with both providers and clients to identify structural-level factors affecting implementation of MMT program in China (Lin et al., 2010). Adaptation content: “The MMT CARE intervention consisted of two linked components: (i) group sessions with service providers and (ii) individual sessions delivered by trained providers to clients.” In the first component, service providers received three group sessions in about “MMT protocol and procedures, understanding stigma and its impact, and effective communication with clients and motivational interviewing concepts and skills,” which reflected the challenges faced by MMT providers identified in earlier formative studies (Li et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2010). In the second component, trained providers delivered two brief MI sessions in a one-on-one format to 3–6 clients. “The providers were encouraged to apply the skills, tools and strategies learned from the provider training to assist clients in treatment adherence by enhancing their motivation and commitment to positive behavior changes.” Translation of MI to Chinese is likely and translation methods NR. |

| Liu et al. 2011 | Brief intervention based on the principles of MI and strategies of MET delivered in Taiwan. Translation is likely. Translation/adaptation methods and content NR. |