Abstract

Background

Apnea is common in preterm infants and can be accompanied with severe hypoxic damage. Early assessment of apnea risk can impact the prognosis of preterm infants. We constructed a prediction model to assess apnea risk in premature infants for identifying high-risk groups.

Methods

A total of 162 and 324 preterm infants with and without apnea who were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit of Xiamen University between January 2018 and December 2021 were selected as the case and control groups, respectively. Demographic characteristics, laboratory indicators, complications of the patients, pregnancy-related factors, and perinatal risk factors of the mother were collected retrospectively. The participants were randomly divided into modeling (n = 388) and validation (n = 98) sets in an 8:2 ratio. Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to independently filter variables from the modeling set and build a model. A nomogram was used to visualize models. The calibration and clinical utility of the model was evaluated using consistency index, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, calibration curve, and decision curve, and the model was verified using the validation set.

Results

Results of LASSO combined with multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that gestational age at birth, birth length, Apgar score, and neonatal respiratory distress syndrome were predictors of apnea development in preterm infants. The model was presented as a nomogram and the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test showed a good model fit (χ2=5.192, df=8, P=0.737), with Nagelkerke R2 of 0.410 and C-index of 0.831. The area under the ROC curve and 95% CI were 0.831 (0.787-0.874) and 0.829 (0.722-0.935), respectively. Delong's test comparing the AUC of the two data sets showed no significant difference (P=0.976). The calibration curve showed good agreement between the predicted and actual observations. The decision curve results showed that the threshold probability range of the model was 0.07-1.00, the net benefit was high, and the constructed clinical prediction model had clinical utility.

Conclusions

Our risk prediction model based on gestational age, birth length, Apgar score 10 min post-birth, and neonatal respiratory distress syndrome was validated in many aspects and had good predictive efficacy and clinical utility.

Keywords: Preterm infant, Apnea, Influencing factors, Lasso regression, Nomogram, Predictive model

Background

According to the global epidemiology of preterm birth released by the World Health Organization [1], preterm infants accounted for approximately 11% of the total number of newborns worldwide, and complications of preterm infants accounted for approximately 16% of global causes of deaths and 35% of global neonatal deaths in 2016 [2]. Survival rates and quality of life issues associated with preterm births have been the focus of research in the pediatric field. Apnea of prematurity(AOP) is usually defined as a cessation of breathing > 20 s, accompanied by bradycardia (< 100 beats per minute), cyanosis, or a decrease in oxygen saturation [3]. Which is the most common diagnoses in preterm infants and its incidence rates are 7%, 15%, and 54% for infants born at gestational ages of 34–35 weeks, 32–33 weeks, and 30–31 weeks, respectively [3]. If apnea treatment is delayed, and hypoxia lasts longer than 1 min, it can cause irreversible damage to brain cell function in premature infants [4]. Repeated apnea leads to hypoxemia that can damage the function of various organs, which may result in severe neurological sequelae or sudden death, leading to safety concerns and possible delay in development of children [5, 6]. Frequent apnea with chronic intermittent hypoxia causes ventilator dependence, delay in oral feeding, and increased risk of retinopathy of prematurity [7, 8]. At present, there is a lack of effective tools to assess the risk of apnea in premature infants, and healthcare professionals can only address it passively after occurrence. Early detection of apnea of prematurity (AOP) can have important clinical significance and provide social benefits of improved survival rates and prognoses of premature infants. Therefore, this study aimed to construct a predictive model of AOP to identify high-risk patients and provide a basis for AOP prevention strategies and implementation of intervention measures.

Methods

Patient characteristics

Preterm infants born at Zhongshan Hospital, affiliated with Xiamen University, between January 2018 and December 2021 and transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) were selected. The inclusion criteria were as follows: live births before normal gestational age; diagnosis of apnea as per the 5th edition of Practical Neonatology (respiratory arrest time > 20 s, a slow heart rate [< 100 beats/min], or a decrease in oxygen saturation) for inclusion into the case group; and no diagnosis of apnea for inclusion into the control group [3]. The exclusion criteria were severe congenital malformations, inherited metabolic diseases, being critically ill and death within 48 h of admission, transfer to another hospital or abandoned hospitalization, and incomplete information. Overall, 162 premature infants with AOP and 324 adjacent premature infants without AOP were included in this study. Of these patients, 291 (59.9%) were boys, and 195 (40.1%) were girls. The male-to-female ratio was 1.49:1. The gestational age ranged from 26.14 w to 36.86 w, with a mean of 34.29 ± 0.09 w. The birth weight ranged from 730 to 3750 g, with an average birth weight of 2178.45 ± 23.91 g. A total of 377 patients were singletons (77.6%), 101 were twins (20.8%), 8 were with three fetuses or above (1.6%). Of these patients, 51 (10.5%) were fertilized in vitro and 435 (89.5%) were conceived naturally. This study was approved by the medical ethics committee of the affiliated Zhongshan hospital, Xiamen University (approval number: XMZSYY-AF-SC-12–03).

Study methods

Using a case–control study design, the following information was obtained from the 486 preterm infants: general data (Gender, postnatal age, gestational age, birth weight, birth head circumference, birth cry status, growth classification, and Apgar score etc.), history of resuscitation (asphyxia at birth, mode of ventilation support at birth, and use of pulmonary surfactants), laboratory indicators at admission (C-reactive protein, creatine kinase isoenzymes, and blood gas analysis results), vital signs at admission (temperature, heart rate, respiration rate, and oxygen saturation), and clinical data of the underlying diseases (neonatal respiratory distress syndrome, acidosis, necrotizing enterocolitis, feeding intolerance, clinical sepsis, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, periventricular-intraventricular hemorrhage, patent ductus arteriosus, and neonatal anemia etc.). Maternal perinatal-related factors were also collected, including the mother's age, conception mode, delivery mode, abnormal amniotic fluid, the number of fetuses in the delivery, the umbilical artery blood stream S/D value, whether the mother used hormones prenatally, whether premature rupture of membranes occurred, gestational diabetes, and hypertension during pregnancy etc..

Using the R software sample function, 486 participants were randomly divided into the training set (80%, 388 cases) and validation set (20%, 98 cases) [9, 10]. The training set was used to develop the model, and the validation set was used for internal validation of the model. In the training set, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression was used for the initial screening of model variables, and model construction was conducted through multifactor logistic regression, and the regression model with the smallest Akaike information criterion (AIC) was selected as the final prediction model and presented as a nomogram.The LASSO regression is a compressed estimation method that reduces the number of variables, which can well deal with biased estimators with complex collinear data. By constructing a penalty function to compress the coefficients of variables, this method can compress the estimated coefficients of redundant prediction variables to 0, which plays the role of variable screening at the same time. The problem of insufficient generalization ability of the model caused by over-fitting can be effectively avoided, and a more concise model with higher prediction efficiency can be obtained.

Statistical analyses

In this study, SPSS Statistics (Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) and R Statistical Software (v4.0.5; R Core Team 2021) were used. The metrological data conformed to the normal distribution were expressed by mean ± standard deviation () and compared between groups using T-test. Those that did not conform to the normal distribution were described by median and quartiles [M (P25, P75)] and compared between groups using the Mann–Whitney U test. The count data were statistically described using cases and percentage n (%) and analyzed using Chi-square (χ2) test, or Fisher exact probability method, as applicable. LASSO regression was used for the initial screening of the model variables. The regression equation was constructed using multifactor stepwise logistic regression (bidirectional method), and the goodness-of-fit of the model was judged using the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. Consistency index (C-index), area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC), calibration curve and decision curve (DCA) were used to evaluate the differentiation, calibration, and clinical application value of the model, and the data from the validation set was used to verify the model. Comparisons between AUCs were performed using the Delong test.

Results

Comparison of the baseline patient data between modeling and validation sets

The overall population distribution was as follows: 388 patients were in the training cohort and 134 had AOP (34.54%); 98 patients were in the validation cohort, and 28 had AOP (28.57%). There were no significant differences in the main demographic characteristics, the incidence of comorbidities, or laboratory indicators between the modeling and validation groups (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline data of patients in the modeling and validation sets

| Variables | Training set (n=388) | Validation set (n=98) | T/Z/χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic patient data | ||||

| Gender [no. of cases (%)] | 0.993c | 0.319 | ||

| Male | 228(58.76) | 63(64.29) | ||

| Female | 160(41.24) | 35(35.71) | ||

| Gestational age w () | 34.30±2.06 | 34.27±2.13 | 0.147a | 0.883 |

| Birth weight g () | 2175.17±545.53 | 2191.43±448.68 | -0.306a | 0.760 |

| Birth length cm () | 44.39±3.46 | 44.75±2.85 | -1.077a | 0.283 |

| Birth head circumference cm () | 30.98±2.32 | 31.18±1.95 | -0.899a | 0.370 |

| Growth classification [no. of cases (%)] | 4.376c | 0.112 | ||

| SGA Infant | 39(10.05) | 17(17.35) | ||

| AGA Infant | 340(87.63) | 78(79.59) | ||

| LGA Infant | 9(2.32) | 3(3.06) | ||

| Apgar.1 Points () | 8.46±1.07 | 8.70±0.63 | -2.938a | 0.004 |

| Apgar.5 Points () | 8.86±0.83 | 9.02±0.43 | -2.641a | 0.009 |

| Apgar.10 Points () | 9.27±0.77 | 9.42±0.57 | -2.082a | 0.039 |

| Postnatal age d () | 0.06±0.38 | 0.13±0.88 | -0.778a | 0.438 |

| Perinatal-related factors of pregnant mothers | ||||

| Gravidity [M (P25, P75)] | 2(1,3) | 2(1,3) | -0.452b | 0.652 |

| Parity [M (P25, P75)] | 2(1,2) | 1.5(1,2) | -1.029b | 0.304 |

| Maternal age year [M (P25, P75)] | 31(28,34) | 30(27,33) | -1.459b | 0.145 |

| The way of conception [no. of cases (%)] | 1.468c | 0.226 | ||

| Natural conception | 344(88.66) | 91(92.86) | ||

| Artificial test tube | 44(11.34) | 7(7.14) | ||

| Mode of delivery [no. of cases (%)] | 0.067c | 0.796 | ||

| Transvaginal delivery | 98(25.26) | 26(26.53) | ||

| C-section | 290(74.74) | 72(73.47) | ||

| General anesthesia during delivery [no. of cases (%)] | 0.284c | 0.594 | ||

| No | 367(94.59) | 94(95.92) | ||

| Yes | 21(5.41) | 4(4.08) | ||

| Singleton or multiple births [no. of cases (%)] | 0.124c | 0.940 | ||

| Singleton | 301(77.58) | 76(77.55) | ||

| Twins | 81(20.88) | 20(20.41) | ||

| Triplets or above | 6(1.55) | 2(2.04) | ||

| Prenatal use of hormones [no. of cases (%)] | 0.374c | 0.541 | ||

| No | 44(11.34) | 9(9.18) | ||

| Yes | 344(88.66) | 89(90.82) | ||

| Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy [no. of cases (%)] | 0.612c | 0.434 | ||

| No | 324(83.51) | 85(86.73) | ||

| Yes | 64(16.49) | 13(13.27) | ||

| Gestational diabetes mellitus [no. of cases (%)] | 0.065c | 0.798 | ||

| No | 260(67.01) | 67(68.37) | ||

| Yes | 128(32.99) | 31(31.63) | ||

| Abnormal amniotic fluid [no. of cases (%)] | 3.654c | 0.056 | ||

| No | 315(81.19) | 71(72.45) | ||

| Yes | 73(18.81) | 27(27.55) | ||

| Premature Rupture of Membrane [no. of cases (%)] | 0.014c | 0.907 | ||

| No | 244(62.89) | 61(62.24) | ||

| Yes | 144(37.11) | 37(37.76) | ||

| S/D value [M (P25, P75)] | 4.17(4.05,4.38) | 4.16(4.04,4.35) | -0.724b | 0.469 |

| Other perinatal risk factors | ||||

| Birth cry status [no. of cases (%)] | 1.498c | 0.221 | ||

| Normal | 183(47.16) | 53(54.08) | ||

| Abnormal | 205(52.84) | 45(45.92) | ||

| Asphyxia at birth [no. of cases (%)] | 4.255c | 0.039 | ||

| Absent | 340(87.63) | 93(94.90) | ||

| Present | 48(12.37) | 5(5.10) | ||

| Mode of ventilation support at birth [no. of cases (%)] | 2.640c | 0.450 | ||

| None | 303(78.09) | 83(84.69) | ||

| Oxygen inhalation stimulation | 31(7.99) | 7(7.14) | ||

| Simple breathing air bag | 23(5.93) | 4(4.08) | ||

| Simple breathing air bag and endotracheal intubation | 31(7.99) | 4(4.08) | ||

| Use of pulmonary surfactants [no. of cases (%)] | 3.302c | 0.069 | ||

| Absent | 319(82.22) | 88(89.80) | ||

| Present | 69(17.78) | 10(10.20) | ||

| Preterm infant-related comorbidities | ||||

| Patent ductus arteriosus [no. of cases (%)] | 0.760c | 0.383 | ||

| Absent | 316(81.44) | 76(77.55) | ||

| Present | 72(18.56) | 22(22.45) | ||

| Abnormal coagulation function [no. of cases (%)] | 0.498c | 0.481 | ||

| Absent | 364(93.81) | 90(91.84) | ||

| Present | 24(6.19) | 8(8.16) | ||

| Hypoglycemia [no. of cases (%)] | 3.118c | 0.077 | ||

| Absent | 288(74.23) | 64(65.31) | ||

| Present | 100(25.77) | 34(34.69) | ||

| HIE [no. of cases (%)] | 0.000c | >0.999 | ||

| Absent | 382(98.45) | 97(98.98) | ||

| Present | 6(1.55) | 1(1.02) | ||

| PIVH [no. of cases (%)] | 3.563c | 0.059 | ||

| Absent | 371(95.62) | 89(90.82) | ||

| Present | 17(4.38) | 9(9.18) | ||

| Electrolyte disorder [no. of cases (%)] | 0.366c | 0.545 | ||

| Absent | 345(88.92) | 85(86.73) | ||

| Present | 43(11.08) | 13(13.27) | ||

| Clinical sepsis [no. of cases (%)] | 0.772c | 0.380 | ||

| Absent | 373(96.13) | 96(97.96) | ||

| Present | 15(3.87) | 2(2.04) | ||

| NEC [no. of cases (%)] | 0.223c | 0.636 | ||

| Absent | 358(92.27) | 89(90.82) | ||

| Present | 30(7.73) | 9(9.18) | ||

| Feeding intolerance [no. of cases (%)] | 4.074c | 0.044 | ||

| Absent | 260(67.01) | 76(77.55) | ||

| Present | 128(32.99) | 22(22.45) | ||

| Anemia [no. of cases (%)] | 0.275c | 0.600 | ||

| Absent | 291(75) | 76(77.55) | ||

| Present | 97(25) | 22(22.45) | ||

| NRDS [no. of cases (%)] | 0.395c | 0.530 | ||

| Absent | 232(59.79) | 62(63.27) | ||

| Present | 156(40.21) | 36(36.73) | ||

| Aciosis [no. of cases (%)] | 0.616c | 0.432 | ||

| Absent | 257(66.24) | 69(70.41) | ||

| Present | 131(33.76) | 29(29.59) | ||

| Life signs and laboratory indicators on admission | ||||

| Temperature ℃ () | 36±0.30 | 36.07±0.27 | -2.407a | 0.017 |

| Heart rate cpm () | 140.71±10.60 | 140.20±14.89 | 0.318a | 0.751 |

| Respiration rate cpm () | 55.40±5.62 | 55.23±4.37 | 0.313a | 0.754 |

| Oxygen saturation% () | 91.88±4.82 | 91.82±6.80 | 0.082a | 0.935 |

| C-reactive protein mmol/l [M (P25, P75)] | 0.19(0.19,0.25) | 0.19(0.19,0.21) | -1.050b | 0.294 |

| Creatine kinase isozyme mmol/l [M (P25, P75)] | 87.35(58.7,123.13) | 93(64.58,121.65) | -0.848b | 0.397 |

| PH value in blood gas [M (P25, P75)] | 7.3(7.24,7.35) | 7.3(7.24,7.37) | -0.532b | 0.595 |

| Total partial pressure of carbon dioxide in blood gas mmgh [M (P25, P75)] | 46.75(41,56) | 47(41,55) | -0.122b | 0.903 |

| Oxygen partial pressure in blood gas mmgh [M (P25, P75)] | 64.5(53,81) | 62.5(54,79.75) | -0.492b | 0.623 |

| Lactic acid in blood gas mmol/l [M (P25, P75)] | 2.5(1.8,3.40) | 2.3(1.63,3.58) | -0.670b | 0.503 |

| Alkaline residual in blood gas mmol/l [M (P25, P75)] | -3.6(-5.3,-1.90) | -3(-5.9,-1.70) | -0.612b | 0.541 |

SGA Small for Gestational Age, AGA Appropriate for Gestational Age, LGA Large for Gsetational Age, Apgar.1 Apgar score 1 min post-birth, Apgar.5 Apgar score 5 min post-birth, Apgar.10 Apgar score 10 min post-birth, HIE Neonatal Hypoxic-ischemic Encephalopathy, PIVH Periventricular-intraventricular Hemorrhage, NEC Neonatal Necrotizing Enterocolitis, NRDS Neonatal Respiratory Distress Syndrome, PS Pulmonary Surfactant

at-test

bNonparametric rank sum test

cChi-square test

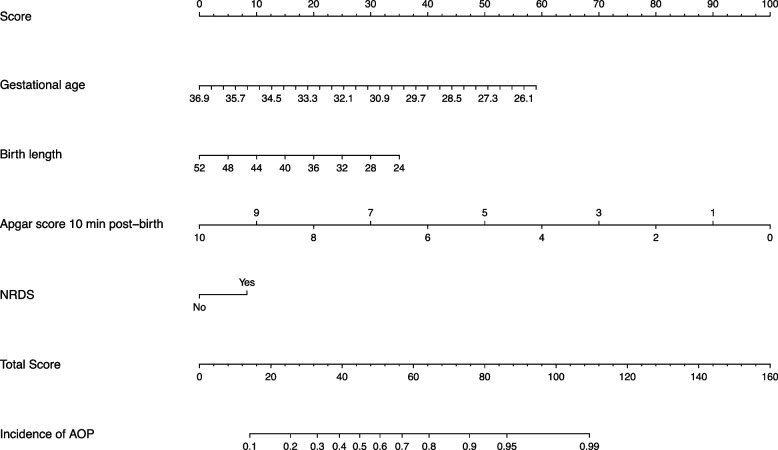

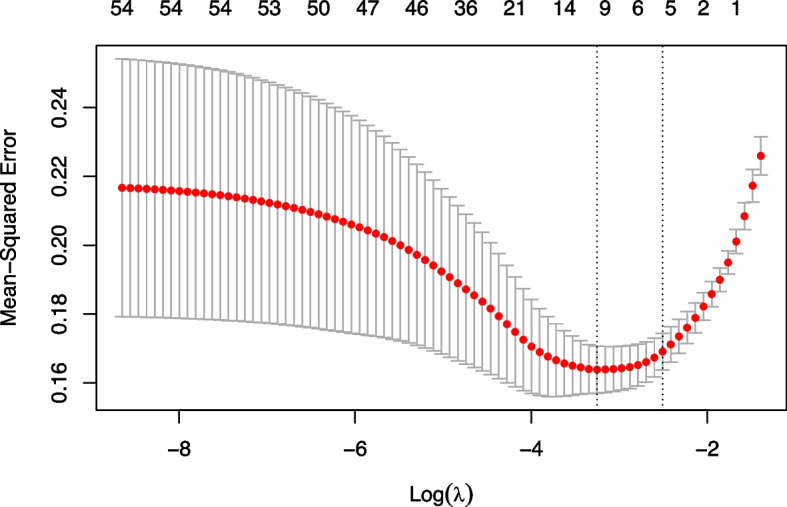

LASSO regression analysis for screening of factors affecting apnea in preterm infants

All variables were included in the LASSO regression analysis. In the model estimation, the optimal solution was the Lambda value (λ) corresponding to the distance of minimum mean square error of one standard deviation. After calculating for λ = 0.0815, five predictor variables were selected, namely the gestational age at birth, birth length, Apgar score 10 min post-birth, neonatal respiratory distress syndrome, and anemia. The regression coefficients were: -0.273, -0.019, -0.226, 0.124, and 0.089, respectively (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1.

Dynamic process diagram of screening variables by Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression. The corresponding lambda value of the LASSO model was 0.0815 for determining the minimum mean square error of one standard deviation (right vertical dashed line) based on the cross-validation method (10 ×)

Fig. 2.

The selection process of the best parameter using lambda values of the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) model. The LASSO regression coefficients for the 50 variables. Based on the log(lambda) sequence, the optimal lambda produced five features with non-zero coefficients

Modeling set construction of an AOP risk prediction model for preterm infants

The five variables obtained from LASSO regression were included in the multivariate stepwise logistic regression model, and the variable of anemia was removed by the model. When trying to include anemia again and build a new logistic regression model, it was found that the AIC for the model that included anemia was 374.4 while the AIC for the model that did not include anemia was 373.4. Based on the model selection principle of minimum AIC, we finally chose the model not containing anemia. In addition, although birth length was not statistically significant (P > 0.05), the respective model had the smallest AIC value. Therefore, it was retained in the multivariate analysis. And the regression equation was constructed using the multivariate logistic regression results as follows: logit (AOP incidence) = 22.4213–0.3756 × birth gestational age-0.0892 × birth length-0.7131 × Apgar.10 + 0.5923 × NRDS. The Nagelkerke R2 was 0.410 and the C-index was 0.831; the model was visualized by the nomogram (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

A nomogram predicting the occurrence of apnea in premature infants

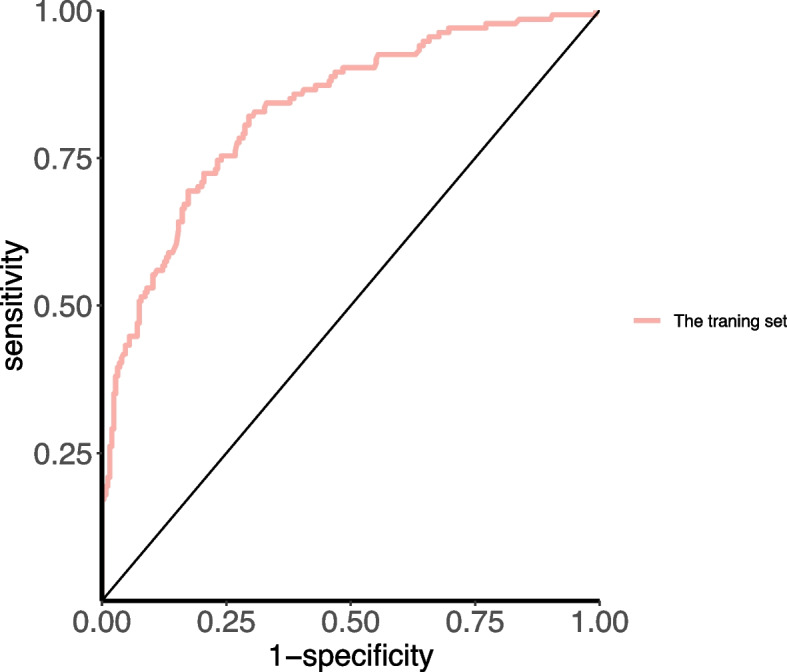

Evaluation of differentiation degree

The prediction model constructed by the modeling set was applied to the validation set, and the results showed that the AUC-ROCs (95% confidence interval [CI]) for assessing the risk of apnea in preterm infants were 0.831 (0.787–0.874) and 0.829 (0.722- 0.935) in the modeling and validation sets, respectively (Figs. 4 and 5). The AUC- ROC curve compared using Delong's method was not significant (P = 0.976), suggesting that the model was stable in both cohorts. When the model prediction point was 0.252, the modeling intensive index was the largest (Youden index = 0.525), model sensitivity was 82.09%, specificity was 70.47%, positive predictive value was 59.46%, and negative predictive value was 88.18%. The validation intensive index was 0.635, model sensitivity was 67.86%, specificity was 95.71%, positive predictive value was 86.36%, and negative predictive value was 88.16%.

Fig. 4.

Area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of the modeling set

Fig. 5.

Area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of the validation set

Evaluation of calibration degree

Further calibration curves were plotted for the modeling and validation sets. The modeling set fitting line was close to the reference line, and the validation set fitting line fluctuated around the reference line, indicating good agreement between the predicted and actual observations (Figs. 6 and 7). In addition, the modeling and the validation set were tested using the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, which showed a good model fit (χ2 = 5.192, df = 8, P = 0.737, and χ2 = 14.522, df = 8, P = 0.069, respectively).

Fig. 6.

The calibration curve of patient prediction nomogram of apnea of prematurity (AOP) risk in the modeling set

Fig. 7.

The calibration curve of patient prediction nomogram of apnea of prematurity (AOP) risk in the validation set

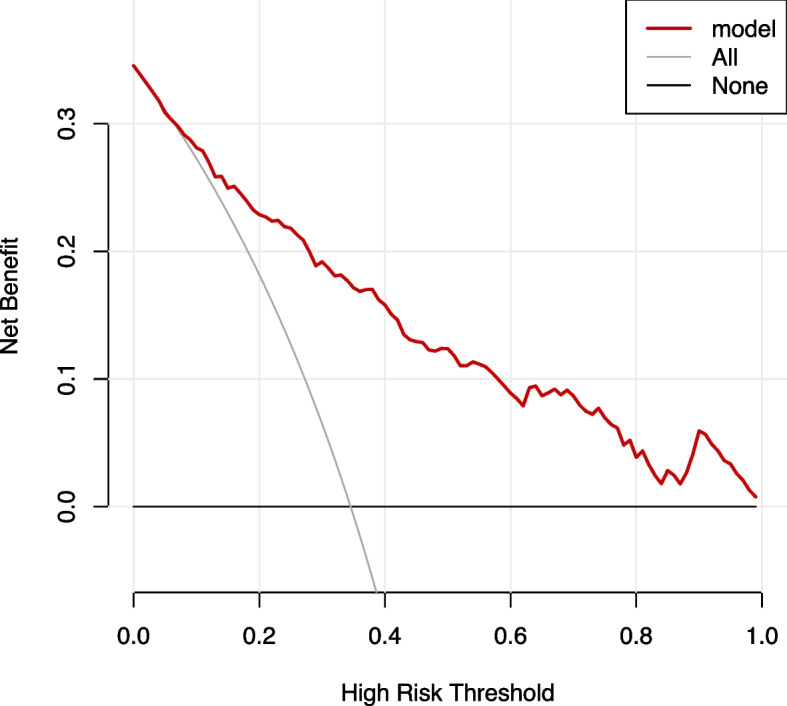

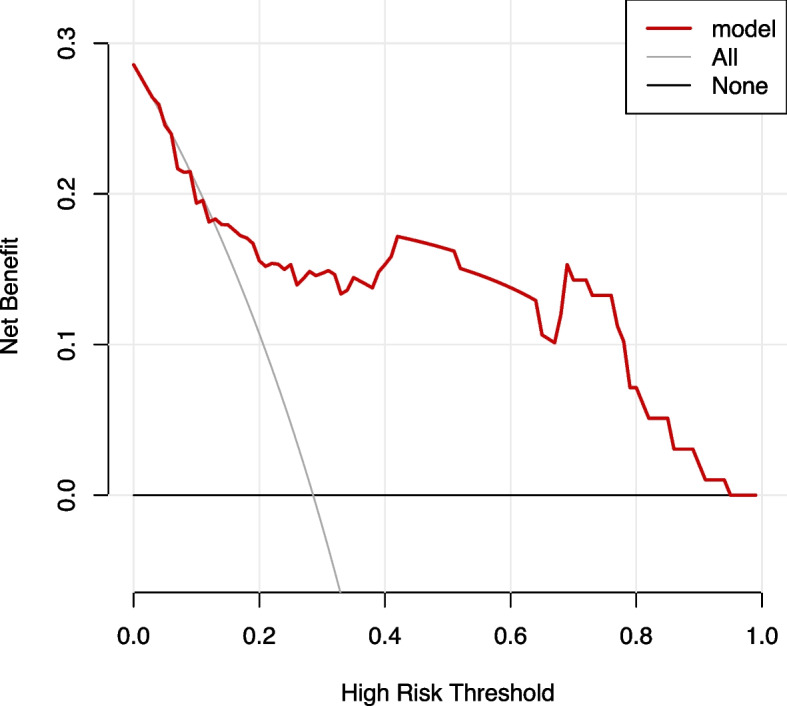

Evaluation of clinical efficacy

A clinical DCA was used to evaluate the clinical application of the model. The results showed that the modeling set fluctuated between the threshold probability of 0.07 and 1, and the application of this AOP risk assessment tool could bring a net benefit to patients, as shown in Fig. 8. While the validation set fluctuates between 0.03 and 0.94, the application of the AOP risk assessment tool can bring net benefits to patients, as shown in Fig. 9. The horizontal axis at the bottom of the figure represents the threshold probability, and the ordinate (backline with a negative slope) represents the net benefit (NB). The "None" line represents the assumption that no intervention is taken for all patients, and the net benefit is zero, whereas the "ALL" line represents that intervention is taken for all patients. The net benefit is shown in the gray back diagonal line in the figure, and the red curve represents the net benefit of the intervention based on the AOP risk in the model. The further the red curve is from the two extremes, the higher the clinical utility of the model.

Fig. 8.

Decision curve for the predicted apnea of prematurity (AOP) risk in the modeling set using the nomogram

Fig. 9.

Decision curve for the predicted apnea of prematurity (AOP) risk in the validation set using the nomogram

Discussion

Apnea is a common disease in preterm infants that threatens life safety and later development of preterm infants owing to its high incidence and possible severe hypoxemia. To avoid adverse outcomes, an AOP risk prediction model was developed in this study. The model had moderate predictive value, and after multiple validations it showed good stability and practical clinical value that might provide a diagnostic basis for clinical healthcare professionals to identify patients with high-risk of AOP to some degree.

The establishment of the nomogram to predict the risk of premature infant apnea is reasonable

In the univariate analysis of all variables in this study, 30 were statistically different. From the statistical analysis, the number of positive cases in the logistic regression analysis model was required to be at least 10 times the number of covariates [11]. However, the number of positive cases (i.e., preterm infants with apnea) was 134, which did not reach the Logistic regression score conditions; therefore, LASSO regression was used to select the variable line [12]. The results were then entered into the logistic regression analysis to construct the model and draw the nomogram. The LASSO regression is a compressed estimation method that reduces the number of variables. By constructing the penalty function, we compressed the coefficients of the variables so that some regression coefficients became zero, thus achieving the purpose of variable screening, which can deal well with biased estimations with complex collinearity data [13]. LASSO applied to logistic regression has been widely used in model construction in the medical field, such as the diagnosis and prediction of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, diagnosis and prediction of subclinical coronary arteriosclerosis, and hospitalization risk prediction of patients with novel coronavirus infection, all of which have achieved good prediction efficacy and showed model stability [14, 15].

A nomogram refers to a quantitative analysis diagram in which a cluster of disjoint line segments represents the functional relationship between multiple variables in plane coordinates. It can directly calculate the value of a variable that has been used in the medical field for a long time [16]. The application of a nomogram to predict the risk of developing apnea has not yet been established. The prediction model for the nomogram and model calculation is simple and short, and can help healthcare professionals in the early detection of apnea risk in premature infants, improve timeliness of assessment, aid appropriate allocation of medical resources, help make auxiliary clinical decisions, such as early use of caffeine or theophylline (respiratory stimulant drugs) in high-risk groups, determine timely use of three-ladder prone therapy and kangaroo care measures, and aid reasonable arrangement of nursing human resources. In addition, the results showed that the model had good discrimination: the AUC-ROC curve was 0.831, the accuracy of the model prediction was 74.48%, and the negative predictive value was 88.18%, which can avoid the missed AOP population. The model’s Nagelkerke R2 (R2 = 0.410) showed a good fit as per the Hosmer–Lemeshow test for goodness-of-fit, but the positive predictive value of the model was low at 59.46%. New predictive variables are required to improve the positive predictive value.

The internal validation of the model for predicting risk of AOP was good

The model was internally assessed using data from the validation set, which showed an AUC value of 0.829, indicating that the prediction accuracy of the nomogram was moderate (0.7–0.9). The results of the ROC curve for the two datasets indicated that the model was stable for both datasets. The nomogram could detect apnea in premature infants and identify high-risk groups. Calibration curves were constructed for both datasets. The basic idea of the calibration graph was to use the nomogram model to predict individual risk of AOP, segment the premature infants into cohorts according to the low- to high-risk order, and calculate the average predicted risk value of each segmented AOP occurrence. The actual risk value of AOP was plotted as the Y axis and the predicted risk value of AOP as the X axis. The calibration point of this segmented queue is obtained from the coordinate chart. Different calibration points were obtained for each segment queue using this method. In the calibration curve, the diagonal (dotted) line indicates that the predicted results completely match the actual results, whereas the solid line (curve) indicates a deviation between the predicted results and the actual results of the nomogram. The closer the correction curve is to the diagonal line, the better the predictive ability of the model. As shown in Fig. 5, the predicted incidence of the model fluctuated around the actual observed value, and the deviation between the diagonal line (dotted line) and the solid line (curve) was small, indicating that the nomogram model could effectively evaluate AOP in preterm infants.

Clinical efficacy of the model for predicting AOP

At present, research on apnea in preterm infants mainly focuses on drug treatment, the choice of mechanically assisted ventilation mode, different intervention means (including medications, kangaroo care, posture management, and the development of awakening instruments and equipment), and the analysis of influencing factors. There are only a few studies on predicting the risk of occurrence. Williamson et al. [17–19] used cardiopulmonary signals and motor signal signatures to develop a model to predict apnea within a short time window. The principle of this method is to trace physiological signals, analyze the dataset, and distinguish the signal characteristics of different periods. However, in the above studies, the sample size was small (ranging from 6 to 10 people), and the duration of observation was short (up to 72 h); therefore, the reliability and stability of the conclusions should be further confirmed. A total of 486 patients were included in this study, and the observation time was the entire hospitalization duration of the preterm infants, which compensated for the above deficiencies to some extent. Shirwaikar et al. [20, 21] used multiple machine learning algorithms to construct a prediction model for the risk of apnea within one week of neonatal admission to the NICU. The study participants were newborns (including term and preterm infants), the observation time for apnea was within 7 days after admission, the sample size was 229 cases, the AUC value of the multi-layer perceptron neural network model was 0.82, and the accuracy rate was 0.66. However, 14 predictors were incorporated in the model, including continuous 72-h average heart rate data, which is not easy to collect. In this study, participants were preterm infants during their NICU stay. Because this population is more likely to experience apnea and requires more attention, the observation time was much longer. The sample size was relatively large, and the constructed model included four predictor variables, which were all readily available indicators in clinical setting. In addition, the visualization effect of the nomogram is relatively strong, the evaluation method is simple compared with the machine-learning model, and it is more convenient for clinical use. The predictive model constructed in this study had an AUC value of 0.831, an accuracy rate of 0.74, a sensitivity of 82.09%, and a specificity of 70.47%. The overall model performed slightly better than the multi-layer perceptron neural network model in the previous study.

In addition, a DCA was used to determine the clinical benefits of this model. The AUC and accuracy focused only on the degree of differentiation and accuracy of model prediction and could not assess the actual clinical utility of the outcome of the model. The predictive model established in this study was based on the combined prediction of four indicators, weighing the clinical benefits of the incidence of AOP, and the evaluation method was determined by comparing the NB rate. As shown in Fig. 6, NB was higher when the threshold probability was in the range of 0.07 to 1.0 compared with that in all patients with or without intervention. That is, when the incidence probability was between 0.07 and 1.00, the prediction model could benefit the patients. Therefore, the model can be expected to have clinical utility and contribute to self-decision-making in AOP prevention.

The present study has several limitations. First, this was a single-center retrospective study, and the study lacked external validation; therefore, the extrapolation of the model remains to be verified. Second, previous studies have shown that factors such as gastroesophageal reflux, sleep duration, and genetic factors may influence the development of AOP. As this was a retrospective cohort study, it was not possible to collect and analyze these variables. Therefore, in future studies, we will further conduct external verification of the model and try to apply it to clinical practice in more convenient forms, such as application software, web pages, or machine scoring, to improve clinical efficiency. Simultaneously, we will continue to investigate new predictor variables and further optimize the prediction model.

Acknowledgements

We thank Editage for English language editing.

Authors’ contributions

Xiaodan Xu designed the study concept and wrote the manuscript. Lin Li contributed equally to this work. Daiquan Chen performed the data analyses. Shunmei Chen, Ling Chen, and Xiao Feng critically revised the manuscript. All the authors reviewed and agreed to the final manuscript.

Funding

The study did not receive any funding.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, Lin Li, upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the medical ethics committee of the affiliated Zhongshan hospital, Xiamen University (approval number: XMZSYY-AF-SC-12–03). The data are anonymous, and the requirement for informed consent was therefore waived. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xiaodan Xu and Lin Li are co-first authors.

References

- 1.Vogel JP, Chawanpaiboon S, Moller AB, Watananirun K, Bonet M, Lumbiganon P. The global epidemiology of preterm birth. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;52:3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNICEF, Bank W, Division UP. Levels and trends in child mortality: report 2017. Estimates developed by the UN Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. 2017. https://www.unicef.org/reports/levels-and-trends-child-mortalityreport-2017.

- 3.Xiaomei S, Hongmao Y, Xiaoshan Q. Practical neonatology. 5th ed. Beijing: People’s Health Publishing House; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shivakumar M, Jayashree P, Najih M, Lewis LE, Kamath A. Comparative efficacy and safety of caffeine and aminophylline for apnea of prematurity in preterm (≤34 weeks) neonates: a randomized controlled trial. Indian Pediatr. 2017;54:279–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Travers CP, Abman SH, Carlo WA. Control of breathing in preterm infants. neonatal ICU and beyond. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:1518–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ambalavanan N, Weese-Mayer DE, Hibbs AM, et al. Cardiorespiratory monitoring data to predict respiratory outcomes in extremely preterm infants. Am J Resp Crit Care. 2023;208:79–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Fiore JM, Raffay TM. The relationship between intermittent hypoxemia events and neural outcomes in neonates. Exp Neurol. 2021;342:113753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim F, Bateman DA, Garey D, et al. Association between intermittent hypoxemia and neurodevelopmental outcomes in extremely premature infants: a single-center experience. Early Hum Dev. 2024;188:105919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu W, Zhang L, Xin Z, et al. A promising preoperative prediction model for microvascular invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma based on an extreme gradient boosting algorithm. Front Oncol. 2022;12:852736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma P, Liu R, Gu W, et al. viaConstruction and interpretation of prediction model of teicoplanin trough concentration machine learning. Front Med. 2022;9:808969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhiman P, Ma J, Qi C, et al. Sample size requirements are not being considered in studies developing prediction models for binary outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2023;23:188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alhamzawi R, Ali H. The Bayesian adaptive lasso regression. Math Biosci. 2018;303:75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bainter SA, McCauley TG, Fahmy MM, Goodman ZT, Kupis LB, Rao JS. Comparing Bayesian variable selection to lasso approaches for applications in psychology. Psychometrika. 2023;88:1032–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu YJ, Mar GY, Wu MT, Wu FZ. A LASSO-derived risk model for subclinical CAC progression in Asian population with an initial score of zero. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7:619798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xue B, Wu S, Zheng M, Jiang H, Chen J, Jiang Z, et al. Development and validation of a radiomic-based model for prediction of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in patients with intrahepatic lithiasis complicated by imagologically diagnosed mass. Front Oncol. 2020;10:598253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang X, Zhao M, Zhang C, et al. Establishment and clinical application of the nomogram related to risk or prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: a review. J Hepatocellular Carcinoma. 2023;10:1389–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williamson J R, Bliss D W. Individualized apnea prediction in preterm infants using cardiorespiratory and movement signals[C]. 2013 IEEE International Conference on Body Sensor Networks. Cambridge: IEEE; 2013. p. 1–6.

- 18.Williamson JR, Bliss DW. Using physiological signals to predict apnea in preterm infants[C]. Proceedings of the 45th Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems and Computers. Pacific Grove: IEEE; 2011. p. 1098–102.

- 19.Zuzarte I, Sternad D, Paydarfar D. Predicting apneic events in preterm infants using cardio-respiratory and movement features. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2021;209:106321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shirwaikar RD, Acharya UD, Makkithaya K, Surulivel RM, Lewis LE. Machine learning techniques for neonatal apnea prediction. J Artif Intell. 2016;9:33–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shirwaikar RD, Acharya UD, Makkithaya K, Surulivelrajan M, Srivastava S. Optimizing neural networks for medical data sets: a case study on neonatal apnea prediction. Artif Intell Med. 2019;98:59–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, Lin Li, upon reasonable request.