Abstract

Background

Postpartum Anxiety [PPA] is a prevalent problem in society, posing a significant burden to women, infant health, and the National Health Service [NHS]. Despite this, it is poorly detected by current maternal mental health practices. Due to the current lack of appropriate psychometric measures, insufficiency in training of healthcare professionals, fragmentation of maternal mental healthcare policy and practice, and the magnitude of the effects of PPA on women and their infants, PPA is a critical research priority. This research aims to develop a clear understanding from key stakeholders, of the current landscape of maternal mental health and gain consensus of the needs associated with clinically identifying, measuring, and targeting intervention for women with PPA, in the NHS.

Methods

Four focus groups were conducted with a total of 21 participants, via Zoom. Data were analysed using Template Analysis.

Results

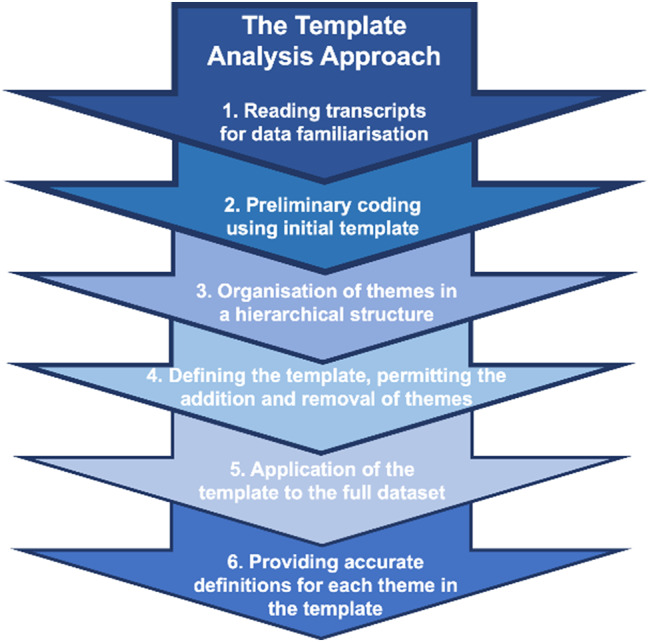

Analysis rendered four main themes: (1) Defining Postpartum Anxiety; (2) Postpartum Anxiety in Relation to other Mental Health Disorders; (3) Challenges to Measurement and Identification of Maternal Mental Health; and (4) An Ideal Measure of Postpartum Anxiety.

Conclusions

Findings can begin to inform maternal mental healthcare policy as to how to better identify and measure PPA, through the implementation of a postpartum-specific measure within practice, better training and resources for staff, and improved interprofessional communication.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12888-024-06058-7.

Keywords: Focus groups, Healthcare policy, Postpartum anxiety, Perinatal psychology, Maternal mental health, Multi-disciplinary team, Template analysis, Qualitative research

Background

The postpartum period is generally expected to be a positive experience for a mother and her newborn. However, this lifecourse transition may encompass mental ill health [1, 2], with the prevalence of perinatal mental health problems in the UK estimated at 20% [3]. Postpartum Anxiety [PPA] is estimated to affect 8% of all mothers in the UK [4] and, as a result, poses a significant burden to women and the National Health Service [NHS], highlighting a major public health concern [5]. Despite this, PPA is under-recognised [6], emphasising the importance of identifying women who require intervention [1].

Whilst some levels of anxiety in the postpartum can be considered adaptive from an evolutionary perspective, a ‘tipping point’ of anxiety can be surpassed, where symptoms significantly impact on women’s functioning and precipitate negative maternal and infant outcomes. Some levels of anxiety may be adaptive and so promote caregiving [7], but negative levels that surpass a tipping point and/or levels of persistent anxiety in the postnatal period can pose risks to both mother and baby [8–10]. For healthcare professionals [HCPs], distinguishing adaptive from pathological anxiety can be challenging [11, 12]. Literature has documented how PPA has the potential to disrupt fundamentals in mothering, including: mother-infant bonding; [13–15] breastfeeding; [16, 17] as well as maternal perception of infant temperament [18–20] infant sleep [21] and infant cognitive outcomes [22]. Additionally, it has been found [5] the lifetime cost per woman experiencing PPA was high to both the healthcare system and for loss of quality-of-life. The multitude of complexity surrounding PPA and the negative outcomes reinforce this disorder as a public health priority [23, 24], however, identification and management of PPA has faced several challenges [25].

The overshadowing of Postpartum Depression [PPD] in research and practice has left women’s experiences of PPA largely misunderstood. In 2010, several recommendations were made with regard to the classification of mental disorders during the perinatal period in the ICD-11, [26] including broadening the onset specifier to include a larger range of illnesses [27]. However, the ICD-11 does not currently offer a separate specifier for PPA, and the disorder cannot be diagnosed unless it can be classified elsewhere. Instead, the focus remains on PPD, despite suggestions that favouring PPD over PPA may underestimate the incidence of PPA [28]. Similarly, although the DSM-5 offers a “with peripartum onset” specifier to a range of mood disorders this does not apply to anxiety during the postpartum period [29], which presents a problem for both diagnosis and treatment of PPA. It has been found [30] that almost all postnatal women who met criteria for anxiety disorder not otherwise specified [ADNOS] also met criteria for generalized anxiety disorder, further highlighting how anxiety disorders are not well defined for women. This has further implications for the diagnosis and treatment of PPA. This overshadowing effect has garnered more recent attention in the field [31], but still exists as a clinical diagnostic phenomenon, despite existing independently [11, 18], and at a higher prevalence rate [18]. PPA is often incorrectly diagnosed as PPD [32] or as comorbid PPA-PPD [33]. Regarding this comorbidity, research and clinical practice consistently refer to anxiety as a product of depression, rather than anxiety accompanied by depression [14]. Evidently, the overshadowing effect presents significant challenges for the specific and targeted identification and management of PPA symptomatology and aetiology (1, 34–35). As such, further research is required to understand the current landscape of maternal mental healthcare in the NHS, including current measurement of PPA in clinical practice.

This overshadowing has led to the pre-eminence of psychometric tools designed to assess PPD rather than PPA, specifically. These include the: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale [EPDS] [36]; Perinatal Depression Inventory [PDI] [37]; and Whooley Questions [38]. These measures can include anxiety sub-scales, but holistic and specific measurement of anxiety remains rare. In practice, this may mean that PPA may be mis-diagnosed as PPD due to lack of appropriate measurement tools for anxiety. Additionally, measures of anxiety which were developed and validated in general populations are frequently utilised in postpartum research and practice, including the State Trait Anxiety Inventory [STAI] [39]; and Generalised Anxiety Disorder [GAD] 7-item [GAD-7] [40] and 2-item [GAD-2] [41]. Consequently, maternal- and infant-focused anxieties, specific to the postpartum, including feeding, bonding, and sleeping, may fail to be captured accurately. General measures also tend to inflate scores by items which would generally be expected during the postpartum [31, 42], for example, “I tire quickly” and “I feel rested” as found within the STAI [39]. Moreover, work conducted with the sub-scales of the Postpartum Specific Anxiety Scale [PSAS] [31] demonstrated the prediction of unique variance above general measures in infant feeding [17] and maternal bonding [13], suggesting childbearing-specific tools are superior in their ability to predict maternal and infant outcomes over general measures. However, as yet, the PSAS has only been used as a research tool.

Evidently, general measures limit clinical measurement and identification in current practice. The EPDS has not performed well as a measure of PPA [42] and its anxiety-based sub-scale, the EPDS-A, has not been found to have significantly higher correlations than the EPDS, with other anxiety measures [43]. The GAD-2 offered superior psychometric properties to the EPDS in measuring PPA [32, 44], and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE] recommends use of the GAD-2 (and the GAD-7 for follow-up) at all universal health visits [6]. However, both GAD measures have failed to achieve sensitivity and specificity thresholds in perinatal samples [45]. It has been found [46] that the prevalence of anxiety symptoms to be 15.0% with the GAD-2, 28.8% with the EPDS-A, and 17.1% with a direct question asking whether women had experienced anxiety in the postpartum period. Kappa coefficients suggested a ‘weak level of agreement’ between measures highlighting demand for improved psychometric scales validated for PPA [42]. Importantly, postpartum women of minority ethnic backgrounds are less likely to report self-identified anxiety [47], highlighting the need to develop culturally appropriate measures [46].

Practice to date has therefore often meant, that in the absence of effective measures, extrapolation from general measures to perinatal contexts is undertaken, despite insufficient psychometric evidence. This is exacerbated by the gap between evidence, policy, and practice surrounding PPA [48], which must be acknowledged in order to enhance the wellbeing of postpartum women, as well as improve perceptions of care. In 2017, the Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists [RCOG] further highlighted the regional disparity of care for perinatal women across England [49], with the Maternal Mental Health Alliance [MMHA] further corroborating the so-called ‘postcode lottery’ when accessing support [50]. Despite commitment by the English government to increase spending on perinatal mental health services [51], and NICE guidance highlighting and prioritising the need for multi-agency services [6], there remains stark disparity across all four nations of the UK in terms of access to perinatal mental healthcare, with only 16% of teams in England, 14% of teams in Scotland and no teams in Wales or Northern Ireland meeting standards for community perinatal mental health services [50]. Poor interdisciplinary communications and variations in service organisations across the NHS, has created confusion from Health Visitors about the ever-changing clinical landscape of referral pathways, frustrated at the availability of specialist services, and waiting lists for psychological support [12, 52]. Clearer policies are vital to identify needs and improve access to support, yet maternity practice and policy initiatives are often unsupported by the evidence previously discussed [53]. Additionally, 10% of postnatal women reported they had not been questioned about their mental wellbeing by their healthcare providers [54]. This may be the result of HCPs feeling unequipped to support women with PPA, due to lack of training [12, 33]. This raises the issue of parity of esteem, with mental healthcare significantly neglected in comparison to physical health. Since women with PPA typically utilise healthcare services more frequently, an effective measure would directly reduce strain on resources [32, 34].

Considering the literature surrounding inadequate measures, poor training, fragmentation of maternal mental health [MMH] policy and practice, and the magnitude of the effects of PPA, there is a need for further research. This multifactorial rationale demands understanding of the current landscape of PPA in the UK, including current identification and measurement, to enable improved measurement, screening, and targeted intervention.

Methods

Present study and setting

The study aimed to better understand the current landscape of MMH within the NHS, and gain consensus from stakeholders, of the needs associated with clinically identifying, measuring, and targeting intervention for PPA. Focus groups with key stakeholders located across the UK, explored views of PPA policy and practice, and data were analysed through Template Analysis [55, 56]. Template Analysis can be adapted to different contexts [57] and its pragmatic and utilitarian outlook allows for multiple worldviews. Subsequently, this work can be considered from a dimensional position rather than dichotomous positivist or constructivist perspectives [57].

Ethics

This study was approved by the University of Liverpool Institute of Population Health Research Ethics Committee on 09 March 2022 (ref:-11083).

Participants and recruitment

Potential participants who identified as being employed in maternal mental healthcare, research, or advocacy were recruited between March and April 2022, via e-mails (for stakeholders with whom the research team had an existing relationship), posting of recruitment adverts on social media, and word-of-mouth snowballing. Inclusion criteria included participants who were aged ≥ 18years, the ability to understand and converse in English, availability to participate in a focus group, and employed within the following categories in the UK: Frontline HCPs, Third Sector Organisations (e.g., community groups, charities, voluntary sector), Regulatory Organisations, and Policy Makers. It was essential for participants to work within the broadly defined field of MMH.

Participants received an information sheet outlining the aims and procedures of the study before providing written informed consent via a form, as well as additional verbal consent from all participants to record prior to recording at the beginning of each focus group. Consent forms were stored on a secure drive only accessible by the research team. The researcher’s emphasised confidentiality of personal data and asked all participants to respect the confidentiality of fellow participants. Each participant was reimbursed £25, in-line with NIHR guidelines [58].

Twenty-three participants were recruited to four focus groups, which included six, eight, four, and three participants, respectively. Two participants were deemed to have provided too little input to their respective focus groups to have made meaningful contributions (i.e. provided their name and role, and perhaps only adding a word of agreement to other participants’ points), and so their data were removed, rendering analysis based on twenty-one participants, including: HCPs (n = 11; 52.38%), Policy Makers (n = 5; 23.80%), Academic Researchers (n = 12; 57.14%), individuals from Third Sector Organisations (n = 5; 23.80%), and individuals involved in Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement (PPIE; n = 2; 9.52%). Participants were geographically located across the UK, allowing for a broad understanding of current MMH policy. See Table 1 for demographic information.

Table 1.

Professional roles of participants

| Participant Identifier | Professional Role | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare Professionals | Policy Makers | Third Sector Organisation Workers | Academic Researchers |

PPIE | |

| A | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| B | ✓ | ||||

| C | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| D | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| E | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| F | ✓ | ||||

| G | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| H | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| I | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| J | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| K | ✓ | ||||

| L | ✓ | ||||

| M | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| N | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| O | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| P | ✓ | ||||

| Q | ✓ | ||||

| R | ✓ | ||||

| S | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| T | ✓ | ||||

| U | ✓ | ||||

N/B

-Some participants were employed within multiple roles

-Policy makers included local and/or central government roles

Data collection

Focus groups conducted via the on-line platform Zoom [59], ensured a national participant pool could participate, and were led by an experienced qualitative researcher [SAS], with another member of the research team also in attendance [EJH, SW]. The four focus groups ranged from 62 to 102 mins (MTime=80.75 mins). A topic guide facilitated consistent questioning across focus groups, but allowed for individual stakeholders’ views and experiences to be heard (see Appendix 1). Focus groups investigated current national policy of MMH, whether regional policies were perceived to support national policy, how PPA is currently defined in clinical practice, the relationship between PPA and PPD, whether stakeholders perceive identification and measurement of PPA to be a problem, and what a measure of PPA should involve. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed by an approved transcription service, pseudo-anonymised, and accuracy checked against the original audio-recording, allowing also for data familiarisation. Transcripts were stored on a secure drive only accessible by the research team. Transcripts were uploaded, managed, and analysed in NVivo12.

Data analysis

Template analysis can obtain meaningful results using smaller samples, and therefore was appropriate for the focus group study we conducted. A coding template was developed and refined according to the topic guide [56] and included themes: (i) Defining Postpartum Anxiety; (ii) Identification and Measurement of Maternal Mental Health; (iii) Postpartum Anxiety in Relation to other Mental Health.

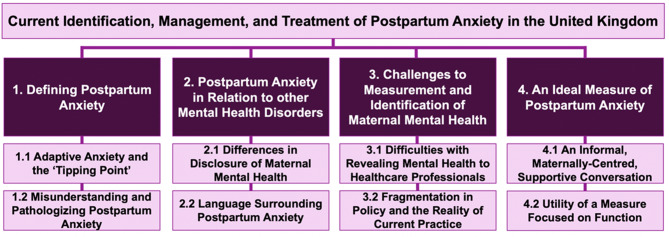

We adopted a methodical, yet reflexive approach to analysis, including: (1) Reading transcripts for data familiarisation; (2) Preliminary coding using initial template; (3) Organisation of themes in a hierarchical structure; (4) Defining the template, permitting the addition and removal of themes; (5) Application of the template to the full dataset; (6) Providing accurate definitions for each theme in the template [56]; see also Fig. 1. The analysis was conducted by one researcher [EJH], under the supervision of a qualitative methods expert [SAS]. Findings were checked for coherence, accuracy, and logical progression from raw data to descriptive and then interpretive analysis with the wider study team [VF, SW]. This team approach allowed for rigorous interrogation of our analysis and eventual findings. Accuracy checking throughout the final two stages confirmed thematic saturation, whereby final themes were supported by sufficient data. An iterative and consultative approach was employed, repeatedly reviewing quotations, ensuring full representation of the dataset, and in the early part of the analysis, the template was adapted to include a fourth theme titled: ‘An Ideal Measure of Postpartum Anxiety’.

Fig. 1.

The Template Analysis Methodology

Results

The final Template Analysis comprised four themes (see Fig. 2 for visual presentation of themes), which are detailed below, with the most illustrative quotations presented and participant identifier for reference.

Fig. 2.

Template Analysis themes and sub-themes

Theme 1: Defining postpartum anxiety

This section of the template dealt with participants’ definitions of PPA. Sub-themes included: Adaptive Anxiety and the ‘Tipping Point’; and Misunderstanding and Pathologizing Anxiety.

Adaptive anxiety and the ‘tipping point’

Stakeholders stated the importance of understanding adaptive anxiety, expected of the postpartum period.

“We really need to get a handle on the distinction between a normative perinatal mental health so that that functional aspect that motivates appropriate caregiving and relate, is reciprocal to the infant attachment system.” (Participant-D).

“I think it’s validating people’s anxiety to say: ‘It’s completely normal to have those feelings.’” (Participant-P).

Moreover, stakeholders suggested anxiety was only negative when perceived as a problem by the mother.

“It is less easy to define perhaps than other mental health issues in the sense that there’s some element of it which is adaptive, so it’s probably what the woman says it is really… if it’s causing her an issue then it’s an issue.” (Participant-G).

The impact on functioning was the ‘tipping point’ which stakeholders used to distinguish between adaptive anxiety and something more pathological.

“At some point that can translate into something that is really adversely affecting quality of life and function.” (Participant-A).

“It’s about recognition of when that is affecting relationships or functioning.” (Participant-P).

“I’ve always thought it’s an evolutionary adaptation if you have a very vulnerable newborn. But obviously, at some point that can translate into something that is really adversely affecting quality of life and function” (Participant-K).

Misunderstanding and pathologizing postpartum anxiety

Many stakeholders acknowledged the misunderstandings surrounding the recognition, prevalence, and impact of PPA; and how commonly these misconceptions occur amongst HCPs.

“I think anxiety is under-recognised both in terms of its prevalence but also its impact and how disabling it is.” (Participant-T).

“I think a lot of practitioners don’t fully understand.” (Participant-E).

Stakeholders expressed efforts to categorise PPA as its own distinct disorder, rather than a feature of depression.

“It’s about trying to hold the space for anxiety being its own disorder… I think it’s not helped by the NICE guidelines.” (Participant-U).

Additionally, this misunderstanding can increase the risk of pathologizing PPA, which may worsen health.

“It’s always been hard to know how anxious is too anxious.” (Participant-U)

“They are functional, and we are pathologizing… normative mood which runs the risk… of… messing people up in terms of their normative caregiving.” (Participant-D).

As a result, fears were expressed surrounding labelling women.

“… ‘labelling’ – to what extent it is enabling and to what extent it’s stigmatising or puts people into boxes that are unhelpful.” (Participant-O).

In contrast, diagnoses were seen as being potentially helpful and an encouraging experience, particularly for those mothers in distress about their symptoms.

“I personally found it quite liberating to have it suggested that what I was experiencing was anxiety because it gave something firm to hang onto in a very confusing situation.” (Participant-O).

Theme 2: Postpartum anxiety in relation to other mental health disorders

The second part of the template discussed PPA in Relation to other Mental Health Disorders. Sub-themes included: Differences in Disclosure of Maternal Mental Health; and Language Surrounding PPA.

Differences in disclosure of maternal mental health

Stakeholders felt a clear difference in patient disclosure surrounding depression and anxiety. Many believed symptoms of anxiety were easier to disclose.

“Depression has a negative connotation, whereas anxiety is something that they can just easily tell clinicians without fearing any issues to do with Social Services.” (Participant-N).

Moreover, disclosing anxiety may be easier due to its advantageous caregiving connotations in comparison to that of PPD.

“They’re more comfortable to say: ‘I’m feeling anxious’, because that almost allows them to feel that they’re being a good parent. You should be anxious, you should be worried about your child, you should be concerned about your child.” (Participant-R).

“I think it does feel, in a sense, less stigmatising than depression, and there’s always that difficult thing that although people are encouraged to talk about their feelings and their mental health… it’s not easy actually to talk to people about feeling low… and in a way it’s easier to talk about anxiety than depression.” (Participant-O).

Stakeholders thought this difference was linked to misunderstandings surrounding anxiety as its own disorder.

“I think that makes it hard for people to… err… kind of think about anxiety in the way that you think about depression. People have a really clear idea of what being depressed means, but being anxious, has a lot bigger range of symptoms or impacts possibly.” (Participant-U).

Moreover, stakeholders suggested that both disorders are often disclosed as one entity.

“I think there’s a tendency in general that anxiety and depression are almost shared in the same breath… you ask them if they have a history of mental health conditions and they say: ‘Oh, I’ve got anxiety and depression’, it comes as a pair.” (Participant-L).

Language surrounding postpartum anxiety

Stakeholders believed language surrounding anxiety to be different to that of depression, which may cause differences in rates and ease of disclosure. They suggested the term anxiety – as a clinical disorder – is often used to describe short-lived emotion.

“I suppose the word anxiety has entered the general language that people use to talk about their mood… I think parents use ‘anxiety’ to mean a whole host of things on a huge continuum, some of which are causing them immense distress… and others of which are causing them a mild level of worry.” (Participant-G).

As previously mentioned, stakeholders believed anxiety does not have the same negative connotations as depression, however, this may cause underestimation of severity.

“It doesn’t feel like it’s so gloomy and so dark, though it’s really, really important for people to recognise that people are desperately challenged by anxiety, and it is a very serious condition…” (Participant-O).

Despite stakeholders believing anxiety to be easier to disclose, stigma still surrounds this mental illness.

“I think there’s too much focus on treatments for PND whereas I think we almost do a bit of, not cheerleading for postnatal anxiety, but get the word out that it’s there and is a condition in its own right. Maybe stigma breaking around that.” (Participant-T).

Theme 3: Challenges to measurement and identification of maternal mental health

The penultimate part of the template covered Challenges to Measurement and Identification of Maternal Mental Health, more generally. Sub-themes included: Difficulties with Revealing Mental Health to Healthcare Professionals; and Fragmentation in Policy and the Reality of Current Practice.

Difficulties with revealing mental health to healthcare professionals

The relationship between HCPs and women and especially the one-to-one mother-HCP relationship which developed over pregnancy, was discussed as being crucial to disclosure of mental health and providing a source of stability.

“The relationship with that practitioner for the benefit of the woman is so critical and that practitioner from a continuity point of view being able to act as a transitional attachment figure themselves… whoever is involved needs to stay involved.” (Participant-D).

“If you don’t know someone and they come into your house and just ask you some questions from a list, I’m really unlikely to tell them anything that’s bothering me.” (Participant-Q).

The lack of use of sensitive language also emerged as a barrier to disclosure, with many participants highlighting the importance of the different elements of the relationship between HCPs and mothers.

“The language that you use, the communication that you use, are really crucial for them opening up about stuff in future.” (Participant-E).

Safeguarding was reported as a barrier to disclosure as women may fear losing their child.

“I’ve worked with families before who were quite worried because their family members said, ‘If you say this, they are going to take your children away’.” (Participant-E).

Furthermore, stakeholders reported confusion about available support.

“In terms of perinatal anxiety, I think we don’t really know what is available to women, what’s acceptable to women and what women are being offered.” (Participant-Q).

Staff training, or a lack thereof, was believed to be the fundamental issue causing difficulty in identification of PPA and offering an obstacle to disclosure by those who were struggling with mental ill health to HCPs.

“The critical thing that’s lacking… is actually any expertise in the broad multidisciplinary perspective.” (Participant-D).

Stakeholders believed this lack of training explained why emotional wellbeing was being disregarded.

“…you’re supposed to ask about maternal wellbeing, and that’s the first thing that Midwives will skip because… they don’t feel that they have the required training to signpost women further.” (Participant-M).

It was also revealed that there is a lack of training on using measures in practice and some reported sourcing external training to provide skills for delivering postnatal care.

“Staff do need training on how to use measures, how to ask women to complete them…and how to interpret what the meanings of that are in terms of the outcome of your clinical assessments.” (Participant-T).

“We have no pre-reg training… I have sourced training which is completely outside of the NHS to enable me to do that client-facing work with greater efficacy.” (Participant- D).

Fragmentation in policy and the reality of current practice

Stakeholders believed the level of fragmentation in both policy and practice was inhibiting the quality of postnatal care delivered.

“Overall, the problems that women experience with postnatal care is fragmentation of services compared to the rest of their maternity journey.” (Participant-S).

Poor communication between services was often cited as causing fragmentation.

“There needs to become some kind of flexibility, finding a better way for services to work alongside each other because the communication between GP, like primary care and secondary care and then mental health services is really poor.” (Participant-E).

Stakeholders also expressed that the guidance on care they receive, is not based upon perinatal research evidence.

“If you look at how the guidance is developed, it isn’t actually drawn from any perinatal studies.” (Participant-A).

Within the focus groups, stakeholders also discussed general measures used within clinical practice:

“We use the GAD-2 questions and if they get a score of three or above then we would proceed to use the GAD-7… there hadn’t been very much research with perinatal populations, a lot of that is based on the GAD-2 in general population.” (Participant-P).

They often expressed negative views surrounding the measures available.

“I honestly don’t think there is a good option for anxiety at the moment.” (Participant-G).

Many stakeholders admitted to drawing on their own expertise to adapt guidance to individual needs.

“There isn’t specific perinatal mental health guidance for those sorts of services, so I’m constantly having to adapt and use what is quite often clinical guidance and use in a more socially oriented and community setting.” (Participant-L).

Stakeholders discussed the reality of trying to access desired support whilst suffering from mental ill health.

“It’s a very complex process and incredibly difficult to navigate if you are already experiencing poor mental health.” (Participant-F).

“There is a mass of often conflicting information about just getting help and I believe that contributes to anxiety and for women who then need help with their anxiety, it’s hard to find and you almost need to be absolutely sane and on top of your game to be able to find the help you need.” (Participant-S).

Flexibility was noted as a requirement to tailor national guidelines to local levels but may cause inconsistencies with care.

“Although NHS England makes recommendations, they’re often left to local implementation and whereas one organisation within my service might agree that something is the right thing to do, the other organisations may not.” (Participant-T).

Theme 4: An ideal measure of postpartum anxiety

The final section of the template was dedicated to perceptions of An Ideal Measure of Postpartum Anxiety, which covered what stakeholders believed to be essential criteria for an effective clinical measure. Sub-themes included: An Informal, Maternally-Centred, Supportive Conversation; and Utility of a Measure Focused on Function.

An informal, maternally-centred, supportive conversation

Stakeholders expressed fears surrounding the risk of stigmatising PPA whilst using a clinical measure and that it should be based solely around support.

“As long as it’s put in the context of giving support… not stigmatising… to detect people who could do with extra support.” (Participant-B).

“What’s the point in assessing mental health, why would we do that, and it’s to ensure that families get the right support that they need” (Participant-C).

Giving supportive information alongside the items of the measure, may increase disclosure and decrease fear.

“I guess having examples… like 'Some anxiety is normal… are you feeling a lot more anxious than you expected or than your peers are?' and then that leading to hopefully a useful conversation.” (Participant-I).

Stakeholders preferred a measure in the form of a conversation to a tick box type measure.

“I’ve always felt the measurements interrupt and disrupt the conversation and make it more tick-boxy and difficult rather than actually opening up the conversation.” (Participant-G).

“I think I’d prefer to be able to have a measure that I could use in a more informal, conversational chatty type of a way.” (Participant-G).

It was also established that a useful measure should take a maternal focus.

“Permitting women to focus on themselves rather than the baby.” (Participant-S).

With this in mind, some stakeholders preferred the idea of a single open-ended question to instigate a meaningful conversation.

“So, we’ll ask the Whooley questions and parents might well say no, and then ask, 'So have you ever suffered with…depression but never spoken to anyone about it?' And the majority would say yes.” (Participant-D).

“A kind of general help for women to disclose, was to say ‘How are you finding being a mum? Is it better than you expected or not to so good as you expected?’… if she suspects there are things the woman is not really disclosing but still looks worried.” (Participant-S).

The importance of the safety of the measure, if utilised for self-diagnosis, was stressed amongst stakeholders.

“I think it’s also really important to be aware that lots of women will use this as a self- diagnosis test… how we can make that a safe thing as well.” (Participant-F).

To overcome issues with disclosure and facilitate conversation, a motivational style of interviewing may be a useful method.

“So, it’s about being able to have that discussion with people, ‘Is this something that’s affecting your life?… What can I do for you?’ Getting them to verbalise it, so using that kind of motivational interviewing style with people.” (Participant-P).

Utility of a measure focused on function

Stakeholders reported that a useful measure for PPA must be clinically actionable.

“So, there’s something about it being clinically actionable; what does it change about your treatment plan or your care pathway or what you offer a family that meant that that tool was useful to you as a practitioner?” (Participant-J).

“It’s not that we label someone with ‘You have postnatal anxiety’, it’s ‘you have these particular symptoms which are making your life really difficult and therefore that informs what support we need to put in place for you’.” (Participant-U).

Many stakeholders commented on the length of what they deemed to be an ideal measure.

“When I’m thinking about my kind of ideal tool for measuring postnatal anxiety, realistically it needs to be something which is short, initially, that has an initial screening and then a longer version.” (Participant-U).

When discussing current measures in practice, shorter measures were favoured due to heavy workloads.

“The GAD-2 perhaps, but definitely not the GAD-7, there are too many questions for Midwives to go through that one, even though that would be preferred, it’s just too much I think for them on top of all the other things that they have to check in a postnatal visit.” (Participant-M).

However, benefits to longer tools were discussed.

“The other thing that has come out is that some of these tools are so long… going into really such detail that it becomes a psychological intervention.” (Participant-T).

Stakeholders expressed the difficulty in producing an ideal short measure which encompasses sufficient breadth and depth.

“I think one of the things which is always going to be difficult is that kind of conflict between getting the breadth you want to cover all anxiety disorders and having it as brief as it needs to be to be realistically used in clinical practice, in a routine way. And that is a really difficult balance.” (Participant-U).

Regardless of a tool’s length, stakeholders highlighted the importance of a focus on maternal functioning.

“If you wanted to make it truly a postnatal anxiety tool, that functionality also has to include functioning as a new mother and not just day-to-day functioning.” (Participant- M).

Frequency and intensity of symptoms also emerged as a priority for an effective measure of PPA.

“Because if the person’s showing symptoms, finding it difficult to function and experiencing these symptoms on a frequent basis, then they will need a lot more support than someone who may not be experiencing it frequently.” (Participant-H).

Discussion

The study aimed to acquire understanding from key stakeholders, including Frontline HCPs, Third Sector Organisations, Policy Makers, and Academic Researchers, of the landscape of current MMH policy and practice, in the NHS. A secondary aim was to gain consensus of the needs associated with clinically identifying, measuring, and targeting intervention for women with PPA.

Defining postpartum anxiety

Stakeholders addressed the under-recognised prevalence and severity of PPA. It has been reported [11] that the concept of perinatal anxiety was ill-defined, presenting as a barrier to its identification and management, and the potential for poorer health outcomes. Consequently, the absence of clear definitions prevents stakeholders from distinguishing between adaptive and pathological anxiety. The ‘tipping point’ identified by stakeholders also coincides with findings of others [60], suggesting anxiety to only be problematic upon the impairment of everyday functioning. The study’s findings, reinforced by literature, highlights PPA as under-researched causing challenges to deliver effective support.

Stakeholders expressed mixed views on labelling women with a disorder, with some suggesting it to be unhelpful and others suggesting its benefits for validating experiences. In support of this, previous research has reported [61] that General Practitioners were reluctant to diagnose and medicalise women’s experiences. However, more recent research [47] suggests specialist care and support for perinatal mental health may positively affect women who find healthcare hard to access, to engage with wider health services. Further research is required regarding safe methods to identify MMH.

Postpartum anxiety in relation to other maternal mental health

The current study suggested anxiety was easier to disclose than depression, due to fewer negative connotations. Furthermore, previous reports suggest [11] perinatal anxiety was not understood well in comparison to depression. Similarly, stakeholders also acknowledged that depression may be readily disclosed due clarity in its definition, as it has remained at the focus of research and practice, overshadowing PPA and its recognition as a disorder [62]. This may inhibit effective articulation of anxiety symptoms and reinforces within women that PPD is the disorder of importance. Subsequently, feelings of marginalisation may emerge when unable to resonate with PPD symptoms with no alternative explanation [63, 64]. This domination of depression and the under-recognition of PPA combined, present as a major issue for identification. The ICD-11 only provides a diagnosis for PPA when not otherwise specified; definitions for disorders with and without presentation of psychosis largely relate to PPD and PPA is not specifically mentioned. Although PPA is often comorbid with PPD [65], increasingly evidence suggests that both prevalence [18] and severity of PPA means it requires attention in its own right. Further evidence needs considering in PPA. Stakeholders discussed that anxiety and depression can be shared within the same breath. Symptoms of anxiety can be subsumed within depression, and therefore dismissed when depression is absent [66]. This inter-relationship is challenging to disentangle which can further inhibit effective identification [62]. This highlights the importance of recognising both anxiety and depression separately, to avoid women and the severity of their mental health being overlooked and undervalued [63]. It also further emphasises the need for an appropriate measure of anxiety to be used in the NHS in order to effectively distinguish, identify, and treat the disorders.

Challenges to measurement and identification of maternal mental health

Stakeholders discussed the issue of staff training especially in regard to effective utilisation and interpretation of psychometric measures. Research has also documented HCPs’ confusion approaching the use of measures in practice [34], and that HCPs lack the necessary competencies to effectively identify and manage disorders [67]. This highlights training as a significant factor in the quality of postpartum care delivered. As such, any new measure that needs to be developed must also offer clear instructions on how the measure needs to be completed, emphasising which scores may indicate the need for further intervention. Stakeholders also expressed dissatisfaction with current measures and acknowledged that general measures had not been evidenced within perinatal populations, causing women to be overlooked for referral to support [31]. These findings emphasise the poor reality of postpartum care in the identification, management, and treatment of mental health disorders, especially in relation to PPA [68]. Furthermore, the societal silencing of negative experiences of motherhood, reveals stigma as source of anxiety and barrier to support [69] with women feeling stigmatised when disclosing mental health to HCPs [70]. This emphasises the significance of addressing safeguarding fears to encourage disclosure.

Moreover, relational care was presented as a poignant aspect of effective postpartum practice. It has been previously reported [71] that women required a trusting relationship with HCPs, regardless of the screening measure used, to disclose information. However, others have found [72] that no individual HCP would take responsibility for the emotional care of women and due to heavy workloads. The lack of follow up from a consistent HCP, further inhibited disclosure [66, 73]. This fragmentation of postpartum care highlights the accountability that stakeholders must take to address these issues within policy and practice [52].

An ideal measure of postpartum anxiety

With the dissatisfaction stakeholders displayed towards current practice, important components of an ideal measure of PPA were suggested. A supportive maternally focused approach was deemed essential with a measure in the form of a conversation, preferred over a tick box type measure. Importantly, HCPs may have the opportunity to reinvent society’s concept of a ‘good mum’ as a mother who discloses, accesses help and recovers, to increase self-worth and foster a new identity [69]. Stakeholders also required the measure to be clinically actionable, similar to others [74], who emphasised that measure outcomes should indicate a clear referral pathway. Stakeholders’ negative views of the GAD and the Whooley questions are reinforced by evaluations of current measures [42, 43, 46] concluding that there is no effective measure of PPA [74].

Stakeholders’ demands regarding what an effective measure needs to encompass, highlights potential modifications that can be actioned to measures. The flaws of general measures have motivated the creation of perinatal-specific tools, such as the Perinatal Anxiety Screening Scale [PASS] [75] and the Postpartum Specific Anxiety Scale [PSAS] [31]. The PASS has been validated in perinatal women. However, by measuring both the prepartum and postpartum, it suggests that symptoms are comparable, despite both encompassing unique experiences [31]. In contrast, the PSAS has been validated and utilised within research around the world. Its successful implementation within research, opens doors for modifications for use in clinical practice. Despite its research success, the PSAS does not cover maternal functioning aspects, an essential component of the current study’s results, and key for the diagnosis of PPA (e.g., anxiety may be experienced often but is not debilitating, or may be experienced infrequently but severely which may require intervention). This suggests that any tool used to measure PPA in clinical settings also needs to consider functioning. These tools provide the foundations of an effective measure of PPA, to be modified and adapted for use within the NHS.

Strengths, limitations, and future directions

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report the perspectives of a range of stakeholders on the current landscape of MMH policies and the effective measurement of PPA. Despite the sample’s ethnic diversity, the variety of professions proved to be an overarching strength, allowing a holistic exploration of PPA in current policy and practice. However, the use of remote focus groups is argued to build weaker rapport compared to a face-to-face discussion [76]. The profile of PPA needs significant elevation to increase awareness and improve identification and management. HCPs in direct contact with women, require improved training and resources on PPA as a disorder, the ever-changing referral pathways, and the appropriate measures to use. Work must be done to have specific tools embedded into clinical practice and use of general measures should be avoided.

Conclusions

This research has obtained clearer understanding of the complex national landscape of MMH through insight from Frontline HCPs, Third Sector Organisations, Policy Makers, and Academic Researchers. A thorough argument for the implementation of postpartum-specific measures into healthcare, specifically warranted for anxiety, has been developed which allows for conversation surrounding anxieties specific to motherhood in order to inform appropriate intervention. This study addressed a multi-factorial rationale, drawing research attention to the under-recognition, under-detection, misunderstandings, and the significant burden PPA poses to women, infants, and the NHS. Overall, this study has contributed important findings to literature around the identification, management, and current policy and practice of PPA.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend thanks to all participants who gave their time to participate in this study.

Abbreviations

- ADNOS

Anxiety Disorder Not Otherwise Specified

- EPDS

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

- GAD-2

Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (2-item)

- GAD-7

Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (7-item)

- HCPs

Healthcare Professionals

- ICD-11

International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision

- MMHA

Maternal Mental Health Alliance

- MMH

Maternal Mental Health

- NHS

National Health Services

- NICE

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- PASS

Perinatal Anxiety Screening Scale

- PDI

Perinatal Depression Inventory

- PPA

Postpartum Anxiety

- PPD

Postpartum Depression

- PPIE

Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement

- PSAS

Postpartum Specific Anxiety Scale

- RCOG

Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists

- STAI

State Trait Anxiety Inventory

Author contributions

Conceptualisation: [VF, SAS]; Methodology: [VF, SAS, EJH]; Software: [EJH]; Validation: [SAS, VF]; Formal Analysis: [EJH, SAS]; Investigation: [SAS, VF, SW]; Resources: [SAS, VF]; Data Curation: [EJH]; Writing – Original Draft: [EJH]; Writing – Review & Editing: [VF, SAS, SW]; Visualization: [EJH]; Supervision: [SAS, VF]; Project Administration: [SW, EJH]; Funding: [VF, SAS].

Funding

This project was funded by the University of Liverpool Faculty of Health and Life Sciences Policy Support Fund – a Research England-funded initiative (ref:- JXG13076), successfully awarded to V. Fallon & S.A. Silverio.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due the potential for identifiability amongst participants. The topic guide is available in the supplementary materials associated with this article.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the University of Liverpool Institute of Population Health Research Ethics Committee on 09 March 2022 (ref:-11083). All participants provided consent to participate. All participants provided informed consent to participate.

Consent for publication

N/A.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sergio A. Silverio and Victoria Fallon share joint senior authorship.

References

- 1.Ali E. Women’s experiences with postpartum anxiety disorders: a narrative literature review. Int J women’s health 2018 May 29:237–49. 10.2147/IJWH.S158621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Saxbe D, Rossin-Slater M, Goldenberg D. The transition to parenthood as a critical window for adult health. Am Psychol. 2018;73(9):1190. 10.1037/amp0000376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The economic case for. increasing access to treatment for women with common mental health problems during the perinatal period [Internet]. [cited 2023 Nov 20]. https://maternalmentalhealthalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/economic-case-increasing-access-treatment-women-common-maternal-mental-health-problems-report-lse-2022-mmha.pdf

- 4.Bauer A, Parsonage M, Knapp M, Iemmi V, Adelaja B, [Internet]., Centre for Mental Health. LSE & ; 2014 [cited 2023 Nov 20]. https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/59885/

- 5.Bauer A, Knapp M, Parsonage M. Lifetime costs of perinatal anxiety and depression. J Affect Disord. 2016;192:83–90. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NICE. 2014 [cited 2023 Nov 20]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg192/resources/antenatal-and-postnatal-mental-health-clinical-management-and-service-guidance-pdf-35109869806789

- 7.Yatziv T, Vancor EA, Bunderson M, Rutherford HJ. Maternal perinatal anxiety and neural responding to infant affective signals: insights, challenges, and a road map for neuroimaging research. Neurosci Biobehavioral Reviews. 2021;131:387–99. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landoni M, Silverio SA, Ionio C, Ciuffo G, Toscano C, Lega L, Gelabert E, Kalcey G, Roca-Lecumberri A, Plaza Estrade A, Brenna V, Bramante A. Mothers who kill their children: a systematic review of perinatal risk factors. Mothers who kill their children: a systematic review of perinatal risk factors. Maltrattamento E Abuso all’Infanzia: Rivista Interdisciplinare. 2022;33–61. 10.3280/MAL2022-002004.

- 9.Wenzel A, Matthey S. Anxiety and stress during pregnancy and the Postpartum Period. The Oxford Handbook of Perinatal psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2014. pp. 132–49. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silverio SA, Wilkinson C, Fallon V, Bramante A, Staneva AA. When a mother’s love is not enough: a cross-cultural critical review of anxiety, attachment, maternal ambivalence, abandonment, and infanticide. International handbook of love: Transcultural and transdisciplinary perspectives. 2021 May 5:291–315.

- 11.Folliard KJ, Crozier K, Wadnerkar Kamble MM. Crippling and unfamiliar: analysing the concept of perinatal anxiety; definition, recognition and implications for psychological care provision for women during pregnancy and early motherhood. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(23–24):4454–68. 10.1111/jocn.15497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silverwood V, Nash A, Chew-Graham CA, Walsh-House J, Sumathipala A, Bartlam B, Kingstone T. Healthcare professionals’ perspectives on identifying and managing perinatal anxiety: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69(688):e768–76. 10.3399/bjgp19X706025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fallon V, Silverio SA, Halford JC, Bennett KM, Harrold JA. Postpartum-specific anxiety and maternal bonding: further evidence to support the use of childbearing specific mood tools. J Reproductive Infant Psychol. 2021;39(2):114–24. 10.1080/02646838.2019.1680960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matthies LM, Müller M, Doster A, Sohn C, Wallwiener M, Reck C, Wallwiener S. Maternal–fetal attachment protects against postpartum anxiety: the mediating role of postpartum bonding and partnership satisfaction. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;301:107–17. 10.1007/s00404-019-05402-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paul IM, Downs DS, Schaefer EW, Beiler JS, Weisman CS. Postpartum anxiety and maternal-infant health outcomes. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):e1218–24. 10.1542/peds.2012-2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fallon V, Groves R, Halford JC, Bennett KM, Harrold JA. Postpartum anxiety and infant-feeding outcomes: a systematic review. J Hum Lactation. 2016;32(4):740–58. 10.1177/0890334416662241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fallon V, Halford JC, Bennett KM, Harrold JA. Postpartum-specific anxiety as a predictor of infant-feeding outcomes and perceptions of infant-feeding behaviours: new evidence for childbearing specific measures of mood. Arch Women Ment Health. 2018;21:181–91. 10.1007/s00737-017-0775-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Field T. Postnatal anxiety prevalence, predictors and effects on development: a narrative review. Infant Behav Dev. 2018;51:24–32. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2018.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nieto L, Lara MA, Navarrete L, Manzo G. Infant temperament and perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms in Mexican women. Sex Reproductive Healthc. 2019;21:39–45. 10.1016/j.srhc.2019.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davies SM, Silverio SA, Christiansen P, Fallon V. Maternal-infant bonding and perceptions of infant temperament: the mediating role of maternal mental health. J Affect Disord. 2021;282:1323–9. 10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davies SM, Todd-Leonida BF, Fallon VM, Silverio SA. Exclusive breastfeeding duration and perceptions of infant sleep: the mediating role of postpartum anxiety. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(8):4494. 10.3390/ijerph19084494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ross KM, Letourneau N, Climie E, Giesbrecht G, Dewey D. Perinatal maternal anxiety and depressive symptoms and child executive function and attention at two-years of age. Dev Neuropsychol. 2020;45(6):380–95. 10.1080/87565641.2020.1838525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alderdice F. What’s so special about perinatal mental health? J Reproductive Infant Psychol. 2020;38(2):111–2. 10.1080/02646838.2020.1734167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tripathy P. A public health approach to perinatal mental health: improving health and wellbeing of mothers and babies. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2020;49(6):101747. 10.1016/j.jogoh.2020.101747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weis JR, Renshon D. Steps towards a comprehensive approach to maternal and child mental health. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4(6):e268–9. 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.International Classification of Diseases. Eleventh Revision (ICD-11) [Internet]. World Health Organization; [cited 2023 Nov 21]. https://icd.who.int/browse11

- 27.Austin MP, ICD-11. Classification of mental health disorders in the perinatal period: future directions for DSM-V and. Archives of women’s mental health. 2010;13:41 – 4. 10.1007/s00737-009-0110-5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Matthey S, Barnett B, Howie P, Kavanagh DJ. Diagnosing postpartum depression in mothers and fathers: whatever happened to anxiety? J Affect Disord. 2003;74(2):139–47. 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Russell EJ, Fawcett JM, Mazmanian D. Risk of obsessive-compulsive disorder in pregnant and postpartum women: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(4):18438. 10.4088/JCP.12r07917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phillips J, Sharpe L, Matthey S, Charles M. Maternally focused worry. Arch Women Ment Health. 2009;12:409–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fallon V, Halford JC, Bennett KM, Harrold JA. The postpartum specific anxiety scale: development and preliminary validation. Arch Women Ment Health. 2016;19:1079–90. 10.1007/s00737-016-0658-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toler S, Stapleton S, Kertsburg K, Callahan TJ, Hastings-Tolsma M. Screening for postpartum anxiety: a quality improvement project to promote the screening of women suffering in silence. Midwifery. 2018;62:161–70. 10.1016/j.midw.2018.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alkhader YK. Generalized anxiety disorder: a review. Int J Med Developing Ctries. 2018;2(2):65–9. 10.24911/IJMDC.51-1518966687. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ashford MT, Ayers S, Olander EK. Supporting women with postpartum anxiety: exploring views and experiences of specialist community public health nurses in the UK. Health Soc Care Commun. 2017;25(3):1257–64. 10.1111/hsc.12428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bener A, Gerber LM, Sheikh J. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders and associated risk factors in women during their postpartum period: a major public health problem and global comparison. Int J women’s health 2012 May 10:191–200. 10.2147/IJWH.S29380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150(6):782–6. 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brodey BB, Goodman SH, Baldasaro RE, Brooks-DeWeese A, Wilson ME, Brodey IS, Doyle NM. Development of the Perinatal Depression Inventory (PDI)-14 using item response theory: a comparison of the BDI-II, EPDS, PDI, and PHQ-9. Arch Women Ment Health. 2016;19:307–16. 10.1007/s00737-015-0553-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, Browner WS. Case-finding instruments for depression: two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(7):439–45. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spielberger CD. State-trait anxiety inventory for adults.

- 40.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–7. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Monahan PO, Löwe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(5):317–25. 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simpson W, Glazer M, Michalski N, Steiner M, Frey BN. Comparative efficacy of the generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale and the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale as screening tools for generalized anxiety disorder in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(8):434–40. 10.1177/070674371405900806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brouwers EP, van Baar AL, Pop VJ. Does the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale measure anxiety? J Psychosom Res. 2001;51(5):659–63. 10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zappas MP, Becker K, Walton-Moss B. Postpartum anxiety. J Nurse Practitioners. 2021;17(1):60–4. 10.1016/j.nurpra.2020.08.017. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Austin MP, Mule V, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Reilly N. Screening for anxiety disorders in third trimester pregnancy: a comparison of four brief measures. Archives Women’s Mental Health 2022 Apr 1:1–9. 10.1007/s00737-021-01166-9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Fellmeth G, Harrison S, Quigley MA, Alderdice F. A comparison of three measures to identify postnatal anxiety: analysis of the 2020 National Maternity Survey in England. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(11):6578. 10.3390/ijerph19116578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pilav S, De Backer K, Easter A, Silverio SA, Sundaresh S, Roberts S, Howard LM. A qualitative study of minority ethnic women’s experiences of access to and engagement with perinatal mental health care. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):1–3. 10.1186/s12884-022-04698-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Antenatal and Postnatal. mental health: clinical management and service guidance (updated edition) [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2023 Nov 21]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK305023/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK305023.pdf

- 49.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. 2017 [cited 2024 Apr 22]. https://www.rcog.org.uk/media/3ijbpfvi/maternal-mental-health-womens-voices.pdf

- 50.Specialist perinatal mental health care in the UK 2023 [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Apr 22]. https://maternalmentalhealthalliance.org/media/filer_public/9a/51/9a513115-1d26-408a-9c85-f3442cc3cb2b/mmha-specialist-perinatal-mental-health-services-uk-maps-2023.pdf

- 51.England NHS. NHS England investment in mental health 2015/16 A note to accompany the 2015/16 National Tariff Payment System – a consultation notice. 2014. www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/payment-systs-mh-note.pdf

- 52.Smith MS, Lawrence V, Sadler E, Easter A. Barriers to accessing mental health services for women with perinatal mental illness: systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies in the UK. BMJ open. 2019;9(1):e024803. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rowan C, Bick D, Bastos MH. Postnatal debriefing interventions to prevent maternal mental health problems after birth: exploring the gap between the evidence and UK policy and practice. Worldviews Evidence-Based Nurs. 2007;4(2):97–105. 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2007.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Redshaw M, Henderson J. Who is actually asked about their mental health in pregnancy and the postnatal period? Findings from a national survey. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:1–8. 10.1186/s12888-016-1029-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.King N. Doing template analysis In: Symon G, Cassell C, editors Qualitative organizational research: Core methods and current challenges.

- 56.Brooks J, McCluskey S, Turley E, King N. The utility of template analysis in qualitative psychology research. Qualitative Res Psychol. 2015;12(2):202–22. 10.1080/14780887.2014.955224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brooks J, King N. Doing template analysis: evaluating an end of life care service. Sage Research methods cases; 2014.

- 58.Payment guidance for researchers and professionals [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Nov 21]. https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/payment-guidance-for-researchers-and-professionals/27392

- 59.Archibald MM, Ambagtsheer RC, Casey MG, Lawless M. Using zoom videoconferencing for qualitative data collection: perceptions and experiences of researchers and participants. Int J Qualitative Methods. 2019;18. 10.1177/16094069198745.

- 60.Wenzel A. Anxiety symptoms during pregnancy and the postpartum period. 2011. 10.1037/12302-001

- 61.Ford E, Lee S, Shakespeare J, Ayers S. Diagnosis and management of perinatal depression and anxiety in general practice: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Br J Gen Pract. 2017;67(661):e538–46. 10.3399/bjgp17X691889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Postnatal anxiety. Under-recognised, over-shadowed, and misrepresented [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2023 Nov 21]. https://www.mumsnet.com/talk/guest_posts/2924476-Postnatal-anxiety-Under-recognised-over-shadowed-and-misrepresented

- 63.Wardrop AA, Popadiuk NE. Women’s experiences with Postpartum anxiety: expectations, relationships, and Sociocultural influences. Qualitative Rep. 2013;18:6. 10.46743/2160-3715/2013.1564. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Coates R, de Visser R, Ayers S. Not identifying with postnatal depression: a qualitative study of women’s postnatal symptoms of distress and need for support. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2015;36(3):114–21. 10.3109/0167482X.2015.1059418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pawluski JL, Lonstein JS, Fleming AS. The neurobiology of postpartum anxiety and depression. Trends Neurosci. 2017;40(2):106–20. 10.1016/j.tins.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miller RL, Pallant JF, Negri LM. Anxiety and stress in the postpartum: is there more to postnatal distress than depression? BMC Psychiatry. 2006;6(1):1–1. 10.1186/1471-244X-6-12.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rothera I, Oates M. Managing perinatal mental health: a survey of practitioners’ views. Br J Midwifery. 2011;19(5):304–13. 10.12968/bjom.2011.19.5.304. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fairbrother N, Corbyn B, Thordarson DS, Ma A, Surm D. Screening for perinatal anxiety disorders: room to grow. J Affect Disord. 2019;250:363–70. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Law S, Ormel I, Babinski S, Plett D, Dionne E, Schwartz H, Rozmovits L. Dread and solace: talking about perinatal mental health. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2021;30:1376–85. 10.1111/inm.12884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oh S, Chew-Graham CA, Silverwood V, Shaheen SA, Walsh-House J, Sumathipala A, Kingstone T. Exploring women’s experiences of identifying, negotiating and managing perinatal anxiety: a qualitative study. BMJ open. 2020;10(12):e040731. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.G3ruhn MA, Dunbar JP, Watson KH, Reising MM, McKee L, Forehand R, Cole DA, Compas BE. Testing specificity among parents’ depressive symptoms, parenting, and child internalizing and externalizing symptoms. J Fam Psychol. 2016;30(3):309. 10.1037/fam0000183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chew-Graham C, Chamberlain E, Turner K, Folkes L, Caulfield L, Sharp D. GPs’ and health visitors’ views on the diagnosis and management of postnatal depression: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58(548):169–76. 10.3399/bjgp08X277212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Prevatt BS, Desmarais SL. Facilitators and barriers to disclosure of postpartum mood disorder symptoms to a healthcare provider. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22:120–9. 10.1007/s10995-017-2361-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Evans K, Morrell CJ, Spiby H. Women’s views on anxiety in pregnancy and the use of anxiety instruments: a qualitative study. J Reproductive Infant Psychol. 2017;35(1):77–90. 10.1080/02646838.2016.1245413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Somerville S, Dedman K, Hagan R, Oxnam E, Wettinger M, Byrne S, Coo S, Doherty D, Page AC. The perinatal anxiety screening scale: development and preliminary validation. Arch Women Ment Health. 2014;17:443–54. 10.1007/s00737-014-0425-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Weller S. Using internet video calls in qualitative (longitudinal) interviews: some implications for rapport. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2017;20(6):613–25. 10.1080/13645579.2016.1269505. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due the potential for identifiability amongst participants. The topic guide is available in the supplementary materials associated with this article.