Abstract

The breakthrough of 3D printing in biomedical research has paved the way for the next evolutionary step referred to as four dimensional (4D) printing. This new concept utilizes the time as the fourth dimension in addition to the x, y, and z axes with the idea to change the configuration of a printed construct with time usually in response to an external stimulus. This can be attained through the incorporation of smart materials or through a preset smart design. The 4D printed constructs may be designed to exhibit expandability, flexibility, self‐folding, self‐repair or deformability. This review focuses on 4D printed devices for gastroretentive, esophageal, and intravesical delivery. The currently unmet needs and challenges for these application sites are tried to be defined and reported on published solution concepts involving 4D printing. In addition, other promising application sites that may similarly benefit from 4D printing approaches such as tracheal and intrauterine drug delivery are proposed.

Keywords: 4D printing, esophageal, gastroretentiveness, intravesical, shape configuration

Evolution of the four dimensional (4D) printing concept represents an outstanding opportunity to reinvigorate the drug delivery field by enabling the fabrication of dynamic delivery systems changing shape or function in response to a predetermined stimulus. This review focuses on the potential opportunities of 4D printing for the advancement of gastroretentive, intravesical and esophageal drug delivery systems, challenges, and future perspectives.

1. Introduction

The 3D printing technology was first described by Hull in the year 1986.[ 1 ] This technology involves precise deposition of materials in a layer‐by‐layer mode utilizing computer‐aided designs, which in turn can yield numerous complex 3D geometrical shapes with desirable spatial arrangements.[ 2 ] The 3D printing technology has gained great attention in the biomedical field as a result of its ability to provide on‐demand and advanced personalized treatments.[ 3 ] Irrespective of the many advantages of 3D printing in designing biomedical devices with favorable and precise geometries, 3D printed constructs are static by concept.[ 4 ] In order to respond to cues of living tissues and physiologic conditions, such as pH, temperature, light, and moisture, an additional property has to be integrated in the material design concept. Triggered by the mentioned stimuli, changes in the 3D printed construct should occur in a predefined time frame which is referred to as the fourth dimension.[ 5 , 6 ] Within that time frame the 4D printing devices show specific properties, e.g., expandability, self‐folding, unfolding or self fitting in response to a certain stimulus.[ 7 , 8 ] The transformation to the fourth dimension can be achieved through incorporation of smart materials or through a preset design which is then called a smart design.[ 9 , 10 ] 4D printed materials are fabricated employing the various techniques of 3D printing such as stereolithography,[ 11 ] fused deposition modeling,[ 12 , 13 ] direct inkjet cure,[ 14 , 15 , 16 ] selective laser melting,[ 17 ] and laser‐assisted bioprinting.[ 18 ] The fabrication technique is usually coupled with a single smart material (e.g., shape memory polymers) or composites as feedstocks. 4D‐printed materials can advance the drug delivery field as they can load a drug and deliver it where the targeted environment provides the predetermined stimulus. Drug delivery science can benefit from smart shape transformation in various ways including shape changes to prolong the residence time of the device at the site of action, administration of the device with minimally invasive procedures, e.g., through narrow orifices or facilitate the removal of the emptied delivery system from the targeted site.[ 19 ] However, the advantages of 4D printing in the pharmaceutical field are still obscured due to the infancy of the concept and the necessity to comply with strict safety and quality guidelines. Consequently, there are a limited number of 4D printing applications that has been proposed in literature. The aim of this review is to provide a focused insight into the advancement of 4D printing in the drug delivery field through reviewing the articles that reported delivery systems which comply well with the 4D printing concept and categorize them from the therapeutic delivery perspective. In this article, we shed the lights on the potential applications of 4D printing in drug delivery with particular emphasis on gastroretentive, esophageal, and intravesical delivery.

2. The 4D Printing Approach: Smart Materials and Designs

In order to obtain 4D printed constructs with changeable features or/and functions, utilization of smart materials and/or smart designs have been introduced[ 5 ] These smart materials and designs should take into account the planned shape or size change (e.g., folding, deployment, twisting, bending) after the printing process.

2.1. Smart Materials

In order to realize the 4D concept, materials that have been used for 4D printing such as shape memory alloys, shape memory polymers, or stimuli responsive hydrogels will be shortly introduced in this section.[ 5 , 20 ]

2.1.1. Classification

Shape Memory Alloys

Shape memory alloys represent metal alloy materials which exist in several specific phases upon exposure to changes in temperature or mechanical load. They depict shape memory behavior as they can regain their initial shapes even after massive deformation.[ 21 ] One of the most studied shape memory alloys for biomedical applications is nitinol which is an equiatomic nickel and titanium alloy. Nitinol is superelastic, biocompatible, and exhibits high resistance to corrosion. It belongs to a group of shape memory alloys that show a phase transformation which is known as martensitic transformation. Shape memory alloys exist in two distinctive solid phases, the austenite and the martensite phase, showing well‐defined crystalline structures and peculiar characteristics. At high temperature, the austenite phase predominates, which depicts a cubic crystalline structure. The martensite phase, on the other hand, exhibits orthorhombic, tetragonal or monoclinic crystalline structure relying on the composition of the alloy. Overall, the trigger for the phase transformation in the shape memory alloys is not only the temperature change but also the application of high mechanical load that is sufficient to promote the transformation from the austenite to the martensite phase. Finally, when the load is released upon heating above specific temperature which is known as “austenitic finish temperature,” the shape recovery will occur through transformation to the original austenite phase.[ 19 ] Shape memory alloys have been widely utilized to fabricate stents for medical purposes. Generally, a stent is a hollow structured mechanical device that is designed to maintain the passageway of the hollow organs in the human body opened (i.e., prevent stenosis of the obstructed organs).[ 22 ] In 1983, the first nitinol stent was proposed by Dotter's group.[ 23 ] In 2001, an in vivo evaluation of a drug eluting stent in human was reported proposing the stents for drug delivery rather than their use solely as a mechanical support.[ 24 ] According to the targeted site, the stents can be divided into vascular stents that remove the occlusion in the vascular bed and nonvascular stents such as stents used for pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and urinary systems.[ 22 ] Recently, nitinol has gained great interest in drug delivery field as a shape memory alloy to fabricate drug releasing stents (e.g., through coating with a drug loaded polymeric matrix) to target various body organs.[ 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ] In addition to the stents, the use of nitinol as a shape memory material in combination with other smart materials to fabricate drug delivery devices such as esophageal device has been reported.[ 29 ] Accordingly, shape memory alloys can be regarded as a potential class of smart materials for drug delivery applications.

Shape Memory Polymers

Shape memory polymers provide a number of advantages compared to shape memory alloys such as high flexibility in stimulus response with reference to composition that can be easily adapted via synthesis and crosslinking degree. The shape memory effect of the polymers was first investigated for polynorbornene‐based polymers in 1984. Later, caprolactones, acrylates, and acrylamide were studied to synthesize shape memory polymers.[ 30 ] Furthermore, polyurethane shape memory polymers have been developed with high flexibility in composition, resulting in a broad range of glass transition temperatures and improved processing abilities.[ 31 ]

Basically, the shape memory polymers are polymeric networks consist of chain segments in addition to netpoints. The netpoints crosslink the chain segments dictating the permanent shape and providing stability of the material. Within shape memory polymers, the netpoints can be generated through chemical or physical crosslinking (covalent bonds or intermolecular interactions, respectively). During shape programming process, shape memory polymers can be deformed upon applying an external stress. Fixation of the temporary shape occurs through incorporating additional reversible netpoints (switchable parts), that prevent the recoiling and restrict the movement of the polymeric chain segments. Hence, a temporary shape can be preserved after releasing the applied stress. The obtained temporary shape remains stable until exposing the material to an appropriate external stimulus, that removes the internal structural barriers initiating the original shape recovery.[ 32 , 33 ] The switching transitions for shape memory polymers can be crystallization/melting, a glass/rubber transition, transition between distinctive liquid crystalline phases, reversible covalent or noncovalent bonds in addition to other stimuli‐responsive domains, for instance, reversible light sensitive groups that are able to induce a segmental rearrangement.[ 34 ] Compared to shape memory alloys, shape memory polymers provide a number of advantages, such as lower density ranging from 1.13 to 1.25 g cm−3 in contrast to nitinol with ≈6.5 g cm−3), higher elongation as well as improved biocompatibility and shape recovery. In addition, shape memory polymers can be combined with various adjuvants such as magnetic particles, nanotubes, and carbon fibers to attain composites with favorable properties.[ 35 ]

Hydrogels

Hydrogels are 3D crosslinked polymeric network structures with high capacity to retain large quantities of water. They are widely investigated for biomedical applications including drug delivery as they possess a bundle of attractive properties.[ 36 , 37 ] For instance, their great water content make them physically similar to tissues with high biocompatibility along with high encapsulation efficiency for hydrophilic drugs. Additionally, the risk of exposing the drugs to organic solvents is avoided since the hydrogels are formed typically in water or aqueous solutions.[ 38 ] Further, hydrogels are believed to protect the highly labile therapeutic compounds from premature enzymatic degradation as a result of hindering the penetration of numerous proteins inside the network.[ 39 ] Generally, hydrogels can be classified according to numerous properties such as physical properties (semicrystalline or amorphous), source (natural, synthetic or hybrid), crosslinking (physical or chemical), electric charge (ionic or neutral), and polymeric composition (homopolymeric, copolymeric or multipolymeric).[ 40 ] Interestingly, hydrogels that exhibit smart behaviors through reversibly transforming their shape in response to certain external stimuli have been recognized as smart hydrogels. These hydrogels can be categorized into shape memory hydrogels and hydrogel actuators. The shape memory hydrogels have the ability to exist in a temporary shape and regain their initial shapes through introduction of crosslinks or their cleavage upon exposure to certain stimulus. On the other hand, hydrogel actuators exhibits asymmetric swelling/ shrinkage in water in a response to certain stimulus.[ 41 ] Although, hydrogels have been employed as active materials for 4D printing purposes, their limitation is their low mechanical strength.[ 42 ] Many approaches can be utilized to overcome this limitation, for instance, blending two polymers in order to build interpenetrating hydrogels. Such hydrogels can be mechanically stiff when the polymeric networks are tightly crosslinked through ionic or covalent bonds formed between the two components. Besides, tuning the mechanical strength of hydrogels can be achieved by particles or fibers reinforcement.[ 43 , 44 , 45 ] Examples of hydrogels that have been investigated for 4D printing applications are hydrogels of sodium alginate,[ 46 ] poly(N‐isopropyl acrylamide), crosslinked poly(2‐hydroxyethyl methacrylate), and 2‐hydroxyethyl methacrylate.[ 22 ]

2.1.2. Stimuli Actuated Shape Transformation

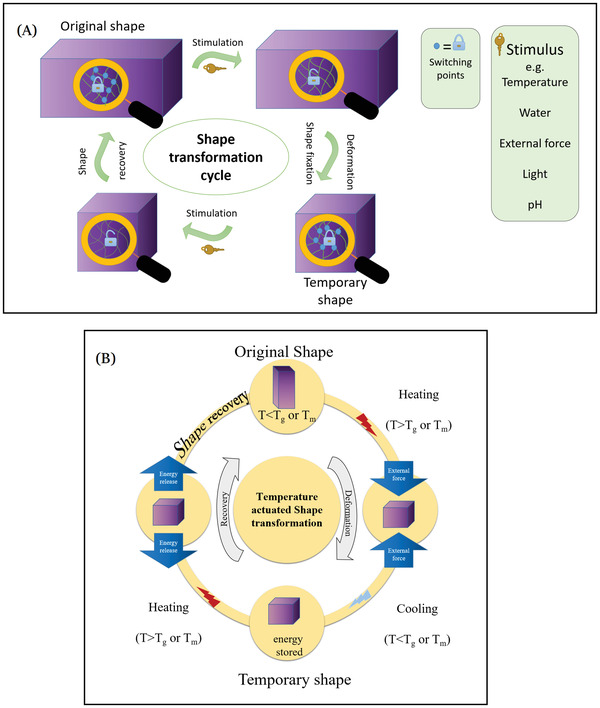

Temperature Actuated Shape Transformation

Among the different reported stimuli, temperature has been widely used as a stimulus in many research studies to produce shape configurable parts. The reversible shape transformation of thermally responsive shape memory polymers depends on the presence of stiff segments in the polymer (primary crosslinking points) which memorize and determine the original shape, in addition to the presence of soft segments (secondary switching points) with a specific transition temperature. The transition temperature can be the glass transition temperature (Tg) in case of amorphous polymers or melting temperature (Tm) in case of crystalline polymers.[ 47 ] In general, polymers with shape memory effect are usually printed in the permanent shape. Then they are subjected to a deforming process at proper conditions (i.e., at a temperature higher than the transition temperature of the polymer in combination with external forces) permitting shape transformation into a temporary shape that is locked through cooling below the transition temperature. Finally, the permanent shape will be regained upon increasing the temperature to or above their transition temperature as illustrated in Figure 1B. Accordingly, the polymers that possess Tg ranging from 25 to 37 °C exhibit high significance for drug delivery and other biomedical applications. The adjustment of Tg of the polymers can be attained through incorporation of plasticizers or tuning the molecular weight or the composition of the polymer.[ 48 , 49 ] Among the temperature responsive polymers are polyurethane,[ 19 , 50 ] crosslinked methacrylated poly(caprolactone),[ 51 ] polylactic acid,[ 52 , 53 ] poly(N‐isopropylacrylamide),[ 54 ] methacrylated poly(ethylene oxide)–poly(propylene oxide)–poly(ethylene oxide) triblock copolymers,[ 55 ] poly(N‐isopropylacrylamide‐co‐acrylic acid),[ 56 ] and poly(hydroxyl ethylacrylamide‐co‐N‐isopropylacryl‐amide).[ 57 ]

Figure 1.

Graphical illustration depicts A) stmilui actuated shape transformation and B) temperature actuated shape transformation as an example.

Water Actuated Shape Transformation

Water has been investigated as an interesting stimulus to attain smart shape configuration; being a cheap stimulus and abundant in human body makes it a potential mechanism for designing shape changing drug delivery systems.[ 58 ] Shape configuration occurs as a result of the differential swelling of the various compartments which happens in a temporally and spatially dependent pattern. In glass transition actuated polymers, the penetration of water molecules into the amorphous domains causes plasticizing effect that increases the flexibility of the polymeric chains. Consequently, Tg drops below the ambient temperature facilitating the recovery of the original shape. On the other hand, dissolution of the crystalline domains in water can be a driving mechanism for shape recovery in case of semicrystalline polymers.[ 59 ] However, some aspects need to be taken into account while designing systems based on water responsive polymers such as the decrease in mechanical strength post swelling or expansion and the delayed responsiveness. Examples of polymers that belong to this category are polyvinyl alcohol (PVA),[ 60 ] crosslinked poly(ethylene glycol),[ 61 ] crosslinked carboxymethyl cellulose,[ 62 ] and crosslinked poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate.[ 63 ] PVA has gained much interest in drug delivery applications as a shape memory polymer with dual responsiveness to temperature or water. Besides, it is a biocompatible, hydrophilic, and nontoxic polymer with the ability to tune its shape memory behavior by adjusting the crosslinking degree of the polymer.[ 64 ] The reported water dependent shape memory behavior of PVA is dependent on the semicrystallinity of the polymer. Thus, the polymer chains can be mobile when the temperature reaches Tg relying on the amorphous parts of the polymer. On the other hand, the permanent shape is preserved based on the crosslinked network and the crystalline regions. Upon contact of PVA with water, the intramolecular or intermolecular hydrogen bonds are weakened thus increasing the mobility of the polymeric chains with a subsequent decrease in Tg and recovery of the permanent shape without the need to use high temperature.[ 65 ] Similarly, beside the thermal responsiveness of the thermoplastic polyurethane polymers, their moisture/water actuated shape transformation has also been reported. As the hydrogen bonds between the C=O and the N—H groups are weakened upon moisture absorption, an augmented mobility of the adjacent chains is observed.[ 66 , 67 ]

Mechanically Actuated Shape Transformation

This mechanism relies on the elastic polymers (named as elastomers), which can be deformed on applying an external force, maintain the deformed shape as long as the force is applied and then they can regain their original shape subsequent to removing the applied force. Utilizing 3D printing technology along with the incorporation of elastic or flexible materials permits the fabrication of delivery systems with the ability to be folded into smaller sized structures upon application of mechanical force. Further, upon removal of the mechanical constraint those devices can retrieve their original expanded shape. For instance, poly(dimethylsiloxane) elastomers undergo folding based on the elastic bending energy.[ 5 ] This feature can be favorably implemented in drug delivery field to fabricate dosage forms that can easily pass through the narrow body orifices, relying on their temporary small shape, thus facilitate their administration via different routes. Further, these dosage forms can expand later in the targeted area to exert a certain function which is the prolonged retention in the target area.

Light Actuated Shape Transformation

The utilization of light as a stimulus for shape transformation has shown numerous advantages including rapid actuation, accuracy, and sustained properties.[ 68 , 69 ] Irradiation of light can induce many transitions involving size or shape configuration as it can form zwitterions, generate charges and induce photodimerization.[ 70 , 71 ] Light actuated shape configuration is more favorable than thermal actuation, since the materials can undergo shape change at ambient temperature without the need to use any external heat. Among the light responsive materials are the azobenzene‐based liquid crystalline polymeric networks which depict shape transformation upon exposure to linearly polarized light. The bending of the material can be achieved through varying the polarization of the incident light. Another example are gels prepared from triphenylmethane leucocyanide functionalized polymers; they have the ability to swell in water upon exposure to UV radiation and shrink upon the removal of the radiation. This transformation occurs as a result of evolution of osmotic pressure between the gel and water following exposure to UV radiation.[ 22 ]

pH Actuated Shape Transformation

The use of pH responsive materials has also been studied with reference to physiological and pathological pH conditions. For instance, the pH differences along the gastrointestinal tract in addition to the local acidity in tumors and inflamed regions. Consequently, the release of drugs from oral dosage forms can be tailored in specific organs and the targeted delivery of anticancer drugs could be achieved.[ 72 , 73 ] The materials that exhibit pH responsiveness have the ability to swell, shrink, dissociate or degrade as a result of cleavage of acid labile bonds. Such materials can be used for 4D printing as they can undergo shape or size transformation depending on their responsiveness to pH variation. There are a number of natural and synthetic polymers that exhibit pH responsive behavior. Among the natural pH responsive polymers are collagen and gelatin, while poly(2‐vinylpyridine) is an example for a synthetic polymer with a pH dependent swelling/shrinkage behavior.[ 74 ] The use of natural pH responsive polymers is limited due to their weak mechanical properties. However, this can be solved by the use of polymer blends to obtain hybrid materials with desirable properties.

2.2. Smart Design

The evolution of 4D printing technology has increased the demand for innovative and sophisticated modeling software to simulate the behavior and deposition of the materials during the printing process. Hence, various commercially available programs have been utilized for 4D printing such as Foundry, CANVAS, and project cyborg software, which were innovated by MIT's computer science and artificial intelligence laboratory, Mosaic Manufacturing, and Autodesk; respectively.[ 5 , 75 ] Additionally, there is other programming software having the ability to create complex constructs with origami designs such as E‐Origami system and Origamizer.[ 76 ] The origami design has gained great interest in 4D printing due to the ability of creating self‐folding structures which resemble the folding and unfolding behavior of an origami paper. This design provides solutions when a large construct needs to pass through or be stored in a small space (e.g., fitting an expandable delivery system into a capsule) so they can fold into smaller constructs with the ability to recover their original large shape upon exposure of specific stimulus.[ 77 ] Various 4D printed constructs can be obtained by giving attention to the smart design so it can serve along with the used materials to achieve the main objective of the 4D printed drug delivery system. Generally, through using either one or more of the smart materials and/or a smart design, 4D objects can be printed and made responsive to one or more stimuli to attain the required dynamism. This dynamism could be investigated in various drug delivery applications. Herein, we will focus on the current applications and opportunities of 4D printing concept in drug delivery.

3. Current Applications of 4D Printing Concept in Drug Delivery

3.1. Gastroretentive Drug Delivery

3.1.1. Anatomy and Physiology of the Stomach

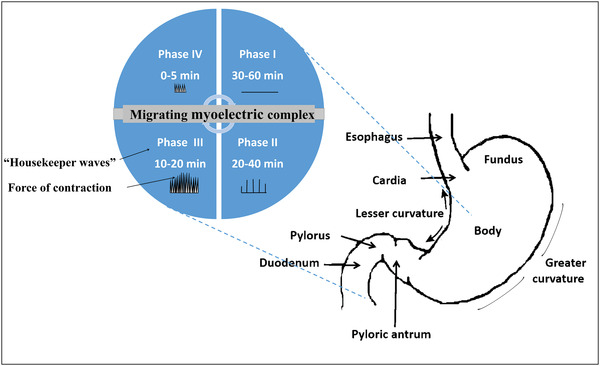

In order to design a successful gastroretentive drug delivery system, it is crucial to understand the anatomy and the physiological function of the stomach. The stomach is composed of two parts including the proximal and distal parts. The former comprises the fundus and the stomach body whereas the latter comprises the antrum and the pylorus (Figure 2 ). The chief function of the stomach is to store food temporarily, digest it by the aid of acid and enzymes particularly peptidases[ 78 ] and eventually deliver it slowly to the duodenum[ 79 ] through the pyloric sphincter whose diameter is nearly 12 ± 7 mm.[ 80 ] The proximal part of the stomach functions as a reservoir for the undigested materials while the antrum functions as a pump with a propelling action to aid in emptying the stomach. The stomach exerts an electromechanical activity which is known as migrating myoelectric complex (MMS) and occurs in a distinct pattern involving four phases. Phase one lasts for 30–60 min. It is the quiescent period during which contractions rarely occur, and then the magnitude and the frequency of the contractions are gradually increased in phase two which lasts 20–40 min. Upon reaching phase three, there are a number of potent and regular contractions that last for 10–20 min permitting clearance of the undigested materials from the stomach to the small intestine thus this phase is known as “the housekeeper wave.” Phase four represents the intermediate phase that occurs as a transitional state between phase three and phase one of two successive cycles and it takes 0–5 min.[ 81 ] The gastric emptying pattern dramatically differs between both the fast and fed state, as in the fasting state the interdigestive electrical events occur sequentially in a cyclic pattern every 90–120 min through the stomach and the small intestine. During the interdigestive phase, the pyloric sphincter expands and its diameter increases, so that smaller materials can pass easily to the duodenum.[ 82 ] The fed state, on the other hand, is characterized by a delayed gastric emptying rate as the motor activity is prolonged to the period during which the food resides in the stomach.[ 83 ] Consequently, an ideal gastroretentive drug delivery system should be able to withstand the stress and the contraction of the gastric housekeeper waves without marked change in gastroretention properties or drug release profile particularly in fasted state. Overall, the gastric environment is harsh and highly variable as a result of the highly acidic conditions in the fasted state where the pH of the stomach ranges from 1.5 to 2,[ 84 ] while it rises in the fed state to be from 3 to 6. Besides, the abundance of the digestive enzymes and the presence of food is counted as another hurdle,[ 85 ] that needs to be considered while designing gastroretentive shape changing drug delivery devices.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of the anatomy of the stomach depicting its electromechanical activity (migrating myoelectric complex) with its four phases.

3.1.2. The Purposes of Achieving Gastroretention of the Drug Delivery Systems

Gastroretentive drug delivery systems have gained a great interest in the last 50 years with the aim of releasing the drugs in the stomach gradually either for providing effective therapeutic concentrations of the drugs in the stomach to exert a local action or for enhancing the systemic absorption.[ 86 , 87 ]

Gastroretention for Local Delivery

The local drug delivery is favorable in managing certain stomach related pathological conditions. There are a number of diseases affecting the stomach and thus it can be advantageous to deliver the therapeutics locally to the site of action. For instance, peptic ulcer, gastritis, infections with H. pylori or other pathogenic bacteria[ 70 ] and gastric cancers.[ 88 ] Various drugs are widely investigated as local therapies for stomach diseases as exhibited in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Potential drug candidates for future 4D printing applications as gastroretentive, intravesical, and esophageal drug delivery systems

| System | Aim | Therapeutic action | Drug | Retention mechanism | Duration | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastroretentive drug delivery systems | Delivery of the drug locally to the stomach | Treatment for peptic ulcer | Ranitidine HCl | Floating | >12 h in vitro | [168] |

| Mucoadhesion | >4 h in vitro | [169] | ||||

| Eradication of H‐ pylori | Amoxicillin | Mucoadhesion | >12 h in vitro | [170, 171] | ||

| Ofloxacin | Floating | >5 h to >12 h in vitro | [172, 173, 174] | |||

| Magnetization | N.D. | [175] | ||||

| Metronidazole | Floating | >24 h in vitro | [176] | |||

| Mucoadhesion | >8 h in vitro | [177] | ||||

| Levofloxacin | Floating | >24 h in vitro | [178] | |||

| Size expansion | >5 h in vitro | [179] | ||||

| Enhancing bioavailability and minimizing side effects | Treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia | Nilotinib | Floating and size expansion | >24 h in vitro | [180] | |

| Prolonging the drug release, eliminate the necessity of frequent dosing and enhance bioavailability | Treatment of hypertension, angina, arrhythmia and migraine | Propranolol HCl | Floating | >24 h in vitro | [181] | |

| >12 in vitro | [182] | |||||

| Local delivery, protection from degradation in intestinal pH and enhance bioavailability | Stomach cancer and ulcer, inflammation, rheumatic and hepatic diseases | Curcumin | Floating | 24 h in vitro | [183] | |

| 24 h in vitro | [184] | |||||

| >8 h in vitro | [185] | |||||

| > 48 h in vitro | [186] | |||||

| Local delivery, enhancing the poor drug absorption and eliminating frequent dosing because of the short half life of the drug (10–20 min) | Treatment of numerous solid tumors including pancreas, colorectal, breast, liver, brain and stomach cancer | 5‐Fluorouracil | Floating | >12 h in vitro | [187] | |

| >48 h in vitro | [188] | |||||

| Gastroretentive drug delivery systems | Enhancing the drug absorption and eliminating frequent dosing and provide constant plasma concentration | Therapy for Parkinson's disease | Levodopa | Size expansion | >5 h in vivo (humans) | [189] |

| Triple mechanism: high density‐size expansion‐mucoadhesion | >24 h in vitro | [190] | ||||

| Treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus | Metformin | Floating | >24 h in vitro | [191] | ||

| >10 h in vitro | [192] | |||||

| >24 h in vitro | [193] | |||||

| Mucoadhesion | >10 h in vitro | [194] | ||||

| Treatment of intermittent claudication and prevention of cerebral infarction | Cilostazol | Floating | >12 h in vitro | [195] | ||

| >2 h in vitro | [196] | |||||

| Treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy, fibromyalgia and seizures | Pregabalin | Floating | >24 h in vitro | [197] | ||

| Delivering to the drug to the site of absorption | Treatment of hypertension, myocardial infarction, angina pectoris and arrhythmia | Atenolol | Mucoadhesion | N.D. | [198] | |

| Floating | > 24 h in vitro | [199] | ||||

| Overcoming drug degradation in the intestinal pH and eliminate the necessity of multiple dosing | Treatment of hypertension and congestive heart failure | Captopril | Floating | >24 h in vitro | [200] | |

| >12 h in vitro | [201] | |||||

| Enhancing bioavailability, improve patient compliance and reduce the risk of drug resistance | Treatment of tuberculosis | Rifampicin | Mucoadhesion | >320 min in vivo (humans) | [202] | |

| Floating | >8 h in vitro | [203] | ||||

| Esophageal drug delivery systems | Local and sustained drug delivery to overcome the limitations of systemic drug administration | Treatment of esophageal cancer | 5‐Fluorouracil | Size expansion | >45 days in vivo (rabbits) | [204] |

| Implantation by surgical sutures | >1 week in vivo (rats) | [205] | ||||

| Belomycin | Mucoadhesion following magnetic guidance | 30 min in vivo (rabbits) | [206] | |||

| Paclitaxel | Size expansion | >2 weeks in vivo (rabbits) | [207] | |||

| Treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis | Budesonide | Mucoadhesion | 30 min in vitro | [208] | ||

| Intravesical drug delivery systems | Reducing the side effects associated with systemic administration of anticholinergic drugs by acting directly on the smooth muscles of the bladder | Treatment of neurogenic bladder | Oxybutynin hydrochloride | Mucoadhesion | ND | [209] |

| Local delivery of anticancer drugs to prolong the residence time in the site of action, reduce systemic drug toxicity and enhance the poor drug penetration through the urothelium | Treatment of bladder cancer | Epirubicin | Mucoadhesion | ND | [210, 211] | |

| Magnetization | ND | [212] | ||||

| Paclitaxel | Mucoadhesion | 120 min in vivo | [213] | |||

| 1 h in vitro | [214] | |||||

| Gemcitabine | Floating | 270 min in vitro | [215] | |||

| Mucoadhesion | ND | [216] | ||||

| ND | [217] | |||||

| Docetaxel | Mucoadhesion | 2 h in vivo (mice) | [218] | |||

| Adriamycin | Floating | 8 h in vitro | [219] | |||

| Mitomycin‐C | Mucoadhesion | ND | [220, 221] | |||

| Doxorubicin | Floating | 3.5 h in vitro | [222] | |||

| Gambogic acid | Mucoadhesion | 60 h in vivo (mice) | [223] | |||

| Cisplatin | Mucoadhesion | ND | [224] | |||

| Local and sustained management of pain associated with ureteral stenting | Treatment of inflammation and relief pain | Ketorolac tromethamine | Mucoadhesion | 12 h in vivo (rabbits) | [225] |

Gastroretention for Systemic Delivery

The repetitive and numerous dosing frequencies of medications are usually responsible for poor patient compliance especially in chronic diseases that require lifelong therapies, inconvenient routes, and methods of administration. The lack of patient adherence to the dosing regimens of their prescribed medications was found to have a significant negative impact on the efficacy of the therapy.[ 89 ] Hence, there is always a great demand on decreasing the complexity of dosing regimens, which endeavor continuous efforts to solve this issue. Consequently, various prolonged release drug delivery systems have been proposed which permit complete drug dissolution and absorption.[ 90 ] Moreover, these delivery systems are beneficial in case of drugs exhibiting a narrow absorption index in the stomach or the upper part of the small intestine along with drugs that exhibit poor stability or solubility at the intestinal pH ranges as illustrated in Table 1.

3.1.3. Current Status of Gastroretentive Drug Delivery and its Challenges

Various formulation approaches have been utilized to achieve an extended gastric retention. These approaches include mucoadhesion, magnetization, buoyancy over the gastric fluid as a result of the low density of the formulations, settling at the stomach bottom due to the high density or volume expansion which hinder the evacuation of the formulation from the stomach.[ 91 , 92 ] However, the application of the gastroretentive formulations may be affected by a number of physiological challenges that occur in the stomach. For instance, the changeable volume and rheological characteristics of the gastric contents in fast and fed states, continuous turnover of the mucus, the displacement of the gastric fluids as a result of the individual movements and positions and the contractile forces of the stomach muscles. Generally, these conditions may restrict the capability of achieving reliable and long‐time residence in the stomach. For example, mucoadhesive formulations may suffer from untimely clearance from the stomach because of the excessive turnover of the mucus. Further, there is an additional consideration regarding the mucoadhesive formulations which is the uncontrollable site of mucoadhesion with a risk of premature mucoadhesion in the esophagus.[ 93 ] The high density formulations may encounter difficulty in manufacturing as they require high drug doses to compensate the progressive reduction in the matrix weight upon continuous drug release.[ 94 ] Among the gastroretentive approaches, the most commercially applicable approach depends on the floating of the dosage form.[ 95 ] However, the floating formulations have some challenges including the dependence of the formulation on the body position[ 96 ] as well as the need to maintain adequate gastric content to permit an efficient separation between the formulation and the pyloric area.[ 97 ] Hence, to achieve a reliable gastroretention a number of points need to be taken into consideration. 1) The system should be able to withstand the harsh environment and the mechanical forces present in the stomach. 2) The in vitro/in vivo evaluation of the system should be able to reliably judge the gastroretention properties and predict the gastroretentive behavior of the system when administered to humans. 3) Safety issues regarding the retention in the proper site, the administration, and the evacuation of the system.

3.1.4. The Potential Opportunities of 4D Printing in Gastroretentive Drug Delivery

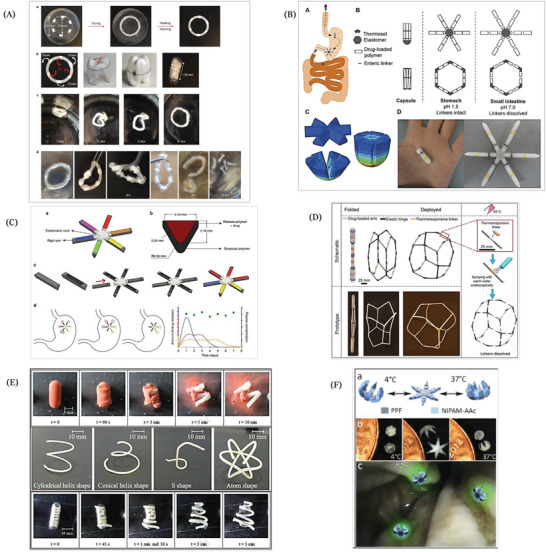

Expandable drug delivery systems have been accomplished to render more reliable stomach residency regardless of the variant physiological conditions.[ 98 ] These systems were planned to exhibit initial relatively small sizes permitting an easy oral administration followed by an in situ expansion taking place directly after reaching the stomach, in order to avoid their evacuation through the widely opened pyloric sphincter. Meanwhile, these expandable drug delivery systems should be amenable to undergo size reduction in order to be easily eliminated after the completion of drug release.[ 99 ] Size expansion can take place as a result of swelling or changing the temporary shapes of the expandable systems upon exposure to a specific stimulus in stomach. In the latter case the system is constrained to a collapsed structure, for example, by folding after fabrication to ease its administration.[ 90 ] Innovative research studies have been recently conducted to fabricate and evaluate various expandable drug delivery systems with a great emphasis on the evacuation mechanism of the exhausted systems from the stomach. Generally, gastric clearance of the systems may be obtained based on size reduction, which can be achieved by oral uptake of specific materials when applicable. Alternatively, breakage or weakening of predetermined portions, designed in the systems, may cause decreased resistance to stomach contractile forces with subsequent clearance.[ 100 , 101 , 102 , 103 ] Recently, taking the advantages of the revolution of the 3D printing technology and more recently the 4D printing, researchers could innovate a number of 4D printed materials that possess gastroretentive properties based on changing their configuration in response to certain stimuli or removal of mechanical constraint. Zhang et al. reported the first enteric elastomer material that possesses a combination of the enteric and elastic characteristics which allows prolongation of the residence time in the stomach and at the same time facilitate safe passage from the gastrointestinal tract after dissolution in neutral pH conditions in the small intestine[ 104 ] (Figure 3A). The material was composed of poly(methacrylic acid‐co‐ethyl acrylate) as enteric and poly(acryloyl 6‐aminocaproic acid) as elastic component and combined with poly(ε‐caprolactone) (PCL) to form a ring‐shaped device employing 3D printing technology for the generation of the design molds. The elasticity of the enteric elastomer material enabled the ring folding into a capsule followed by shape recovery of the ring within 15 min post administration to a Yorkshire pig. The device exhibited an extended gastric residence for a period ranging from 2 to 5 days. Furthermore, the X‐ray imaging allowed to track the device and ensured the safe passage of PCL pieces through the intestine after dissolution of the enteric elastomer parts. In another study, Bellinger et al. have reported the fabrication of a star‐shaped 3D printed gastroretentive system of ivermectin to be used as a dual therapy with artemisinin for the control of malaria infection transmission. The system was designed in a geometry that is able to hamper its passage, at the same time permits the passage of food, through the pylorus thus imparting gastric residence properties to the system.[ 100 ] The system was designed with a polygonal structure of alternating flexible and rigid elements and a central flexible stellate structure from which the rigid elements protrude to form a star‐shaped structure. The incorporation of the flexible elements could impart deformation and deployment abilities to the system while the polymer‐based rigid portions functioned as a drug reservoir. Moreover, enteric components with a degradation ability in the neutral pH were also incorporated to ensure the safe passage of the system out of the stomach through size reduction (Figure 3B). The careful selection of excipients is an important issue that needs to be taken into account while formulating the expandable pharmaceutical dosage forms. The authors used PCL for fabrication of the rigid elements and blended the material with the drug to form a drug releasing matrix. PCL is widely used for 3D printing of sustained release systems due to its biocompatibility and ability to be processed at low melting temperature. In vivo evaluation of this innovative delivery system in a swine model did not exhibit any evidence of obstruction of the pylorus or occurrence of injuries. Further, the system could maintain the stability of ivermection and prolong its release in the stomach over a period up to 14 days which is much longer than what is achievable by the conventional gastroretentive formulations as illustrated in Table 1. Interestingly, both studies[ 100 , 104 ] provided a longer and more reliable gastroretention when compared to the conventional gastroretentive drug delivery systems. This was proven by in vivo studies employing a large animal model (45 to 55 Kg body weight) with a gastrointestinal anatomy close to human. Additionally, the safety issues regarding administration and evacuation were considered in both studies. Nevertheless, the used animal model has one limitation as the pigs exhibit slower gastric emptying rate and longer intestinal transit time compared to humans. Hence, clinical studies will be necessary to support the attained outcomes.

Figure 3.

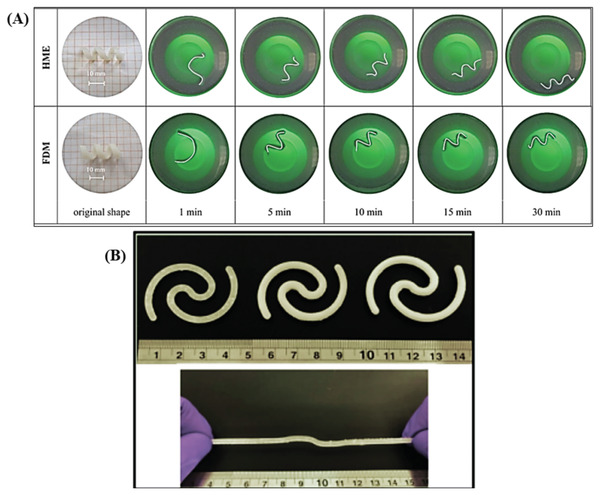

A presentation illustrating the utilization of shape configuration in developing gastroretentive drug delivery systems. A) Fabrication of a ring‐shaped device comprising PCL arcs with disjunctive linkers composed of an enteric elastomer polymer. Ring devices were fabricated from cubic pieces of polymer gel with alternating PCL beads in a polydimethylsiloxane mold via PCL melting at 70 °C. The ring was folded in order to fit into a capsule. After disintegration of the capsule shell, the original ring shape was recovered in simulated gastric fluid at 37 °C. Finally, the enteric elastomer linkers undergo progressive dissociation in simulated intestinal fluid at 37 °C with eventual fractionation of the ring into PCL parts. Reproduced with permission.[ 104 ] Copyright 2015, Nature Publishing Group. B) A modular star shaped system with a schematic illustration of its pathway starting with administration of a capsule that releases its content in the stomach. Presentation of geometric arrangements of rigid and elastic parts of the system to fit the device in a capsule and the dissolution behavior of the system where the enteric linkers (black lines) are intact in gastric pH while the system undergoes fracturing in intestinal pH. Finite element analysis revealed the distribution of stress through the system upon folding it in the capsule by means of its flexible element and representative finished product after assembly and filling in a gelatin capsule where the yellow and black colored parts are the linkers. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons CC BY license.[ 100 ] Copyright 2016, The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). C) (a,c) A system involves 6 API‐carrying rigid arms (multicolored) that are assembled to a star‐shaped device via an elastomeric central core (gray color). (b) A cross‐sectional view of the arm where the external sleeve of the arm is fabricated from a rigid structural polymer that provides the necessary mechanical strength. After that, the sleeve is filled with the desired drug–polymer formulation that by the choice of polymer (represented by different colors) is intended to tune the release rate. The predicted in vivo performance of the system assuming that the system is loaded with three different polymers. (d) Schematic representation of release from the different compartments in the stomach and expected but not experimentally attained plasma concentrations. Reproduced under Creative Commons CC BY license.[ 101 ] Copyright 2018, the Authors. Published by Springer Nature. D) A schematic presentation of the configurable system exhibits the composition of the system and its deployment in the stomach. The panel in the right illustrates the disintegration of the thermoresponsive linkers after endoscopic spraying of warm water at 55 °C with a subsequent fragmentation of the system. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons CC BY license.[ 29 ] Copyright 2019, the Authors. Published by AAAS. E) Formulation of 3D printed PVA gastroretentive systems, the photographs (in the top) illustrate the disintegration of capsule followed by shape transformation of the enclosed system in 0.1 N HCl at 37 °C from a super coiled temporary shape to a cylindrical helix original shape, that was printed with fused deposition modeling technique; the photographs (in the middle) exhibiting the various designed shapes attained from the extruded PVA/glycerol/allopurinol rods by hot melt extrusion technique. The photographs (in the bottom) explain the deformed super coiled formulation undergoing recovery of the original conical helix‐shaped in 0.1 N HCl at 37 °C. Reproduced with permission.[ 99 ] Copyright 2019, Elsevier. F) Schematic presentation of the polymeric multifingered theragrippers exhibiting the rigid poly(propylene fumarate) (PPF) fragments and the flexible hinges of poly(N‐isopropylacrylamide‐co‐acrylic acid). The figure shows the thermal actuation of theragrippers depicting the original closed shape of theragrippers at 4 °C, which transform to the opened shape upon increasing the temperature followed by closure at 37 °C. The theragrippers grasped the colon wall as an illustration of the concept and release a fluorescent compound at the targeted colon regions. Reproduced with permission.[ 56 ] Copyright 2014, Wiley‐VCH GmbH.

Similar to this technology, Kritane et al. have reported another drug delivery system with a once weekly dosing regimen for the controlled release of antiretroviral drugs for managing HIV infections.[ 101 ] This delivery system intended to provide a universal strategy for the delivery of various therapeutic moieties either alone or in combination. This was made possible by matching a range of polymer matrices to the required release kinetics for different drugs, regardless of the polymer's mechanical properties. Hence, this gastroretentive system could successfully deliver three antiretroviral drugs (dolutegravir, cabotegravir, and rilpivirine) from a single structure for a period of one week in a sustained release manner, following a once weekly dose in a swine animal model. In brief, the design of the system involved six rigid arms linked through an elastomeric central core which permits the folding inside a capsule and deployment of the system after disintegration of the capsule shell (Figure 3C). In order to load the drugs and tune their controlled release, the authors milled a pocket inside the backbone of the rigid arms to be incorporated with different drug–polymer reservoirs. With the purpose of ensuring safe passage of the designed system from the stomach, pH responsive linkers that connect the peripheral rigid arms with the central core were included in the design to be stable in the stomach and dissociate in the intestine. This novel strategy may enhance the patient adherence to antiretroviral therapy with a subsequent enhancement of therapy effectiveness. Interestingly, the authors performed fatigue test to mimic the bending forces that affecting the dosage forms in the stomach and to investigate these effects on the integrity of their system. Besides, in vitro test was conducted to determine the force needed for the passage of the system through a simulated pylorus. Further, the gastroretention was proven by X‐ray imaging and pharmacokinetic evaluation which ensured sustained drug release for one week. However, clinical studies are still needed to support these interesting findings of the study.

Among the continuous efforts that have been exerted to innovate adaptable drug delivery systems and devices, Babaee et al. have reported the designing of a highly foldable gastroretentive drug delivery system comprising a number of 24 semirigid PCL arms (50 mm in length) as drug carriers, elastic hinges made of ellastolan 1185A to impart the required flexibility to the system. In addition, thermoreactive linkers (a blend of polycarbonate‐based thermoplastic polyurethane and low molecular weight PCL in a ratio of 2:1 w/w) were incorporated into the system to allow controlled dissociation upon exposure to heat and to ensure safe passage through the gastrointestinal tract[ 29 ] (Figure 3D). Via the elastic hinges the system can be folded into a capsule to be delivered safely through the narrow esophagus. Upon reaching the stomach the system undergoes shape recovery and expands into a large semispherical shape to accomplish extended gastric residence as this large size of the system hinders its passage through the pylorus. The thermal linkers were designed to disintegrate upon endoscopic administration of warm water spray (55 °C) to prevent the risk of intestinal obstruction. This system had the capacity to load drugs that need to be administered in large daily doses such as moxifloxacin and carbamazepine. Up to 3 g could be loaded in a device that provided a daily drug release of 215 mg for a period of 14 days. It also exhibited higher bioavailability of the drugs compared to immediate release formulations, when administered to pigs. Similar to the aforementioned studies, this work presented a longer and more reliable gastroretention than the conventional gastroretentive drug delivery systems (Table 1), that was also proven by in vivo studies on Yorkshire pigs. Additionally, the safety issues regarding administration and evacuation were considered through shape change and the thermal actuation, respectively. Nevertheless, clinical studies are needed in the future to support the attained outcomes. All the concepts presented here refer to 3D printing technologies, but they perfectly fulfill all the requirements of the 4D printing concept as the systems can change their shape taking the time as the fourth dimension.

More recently, Melocchi et al. reported the formulation of a 4D printed system using PVA, which is a widely used polymer in various pharmaceutical applications. The formulations were fabricated employing either fused deposition modeling or hot melt extrusion followed by immediate shaping of the extruded rods.[ 99 ] Different shaped formulations were attained according to the fabrication technique including conical helix‐, cylindrical, atom‐, and S‐shaped (Figure 3E). The designed formulations were manually deformed into various temporary shapes using templates to achieve a size reduction that would allow insertion into the capsule. The formulations were designed to have the capability of changing their configuration to regain their original shape when they reach the stomach. The mechanism of shape recovery of the formulations depended on the shape memory properties of PVA in presence of hydration or heating above Tg; a combination of these two conditions is possible in the stomach. Moreover, the authors incorporated glycerol in the formulation as a plasticizer in order to decrease the Tg of PVA to guarantee the shape recovery under stomach conditions. Unlike the aforementioned gastroretentive devices, the shape recovery of the PVA formulation does not depend on the removal of a mechanical constraint. All the produced formulations were able to recover their shapes within few minutes to exceed 13 mm, which is required for gastric retention. The formulations could control the release of allopurinol for 6 h after coating with Eudragit RS/RL polymer. The authors suggested that the release rate can be tuned through adjusting the controlled release coating or using higher molecular weights of PVA. Finally, the large void volume of the formulations was intended to facilitate the passage of gastric content and the safe clearance of the formulations from the stomach was guaranteed based on the biodegradability of PVA with time. In that work, the safety issues were considered based on the shape recovery of the system after reaching the stomach while the elimination of the system is dependent on the erosion of PVA with time. The work focused on engineering of the 3D printed PVA gastroretentive system and studying the shape recovery as well as the drug release from the system. Hence, further in vivo or clinical studies to investigate the potential gastroretention are needed.

Additionally, a promising application of 4D printing might be the site specific therapeutic grippers, which is termed as theragripper.[ 56 ] Theragrippers are drug loaded polymeric devices with multiple fingers to grip closely and tightly to the cells and tissues to deliver therapeutics. Malachowski et al. reported the fabrication of theragripper whose gripping effect occurs at temperatures higher than 32 °C in order to directly release the drug in a close contact with the tissues in a sustained release pattern (as shown in Figure 3F). Theragrippers were designed utilizing rigid poly(propylene fumarate) fragments and poly(N‐isopropylacrylamide‐co‐acrylic acid) stimuli responsive flexible hinges inspired by origami structures. The thermally induced shape actuation of the theragrippers was due to the hydrophilicity and swelling properties of poly(N‐isopropylacrylamide‐co‐acrylic acid) in water at a temperature lower than 32 °C while upon raising the temperature above 32 °C its hydrophobic groups dehydrate with a subsequent collapse in the polymer. For testing in vitro drug release, theragrippers were loaded with doxorubicin and mesalazine. Via integration of mesalazine in the poly(propylene fumerate) network, the authors were able to show a release that lasted for more than 100 h. Further, doxorubicin loaded theragrippers were aimed at delivering the drug to the stomach after their placement by means of endoscopy to treat stomach cancers. They were shown to be capable of grasping the mucosal tissue of porcine stomach and resisting being drifted away by the flow in the gastrointestinal tract post actuation at body temperature (37 °C). The authors envisioned that their fabricated theragrippers can be removed during the turnover of the mucus that usually occurs weekly or every two weeks.[ 56 ] The mechanism of gastroretention that is achieved by theragrippers differs from the previously mentioned systems, as it depends on grasping the stomach tissue induced by shape change rather than the shape change induced expansion.

Overall, the studies reviewed here present promising gastroretentive concepts, which depend mainly on stimuli driven shape change to attain longer residence in the stomach. However, all the in vivo evaluation of the proposed systems was conducted in pig models, which resemble the human gastric anatomy. Nevertheless, they exhibit slower gastric emptying rate than humans,[ 101 ] which probably influence the gastric retention time of the evaluated systems. Hence, it may be difficult to expect similar behavior when those systems are administered to humans. Generally, it is important to consider the faster transit time in human, which is induced by the powerful contractions (housekeeping waves), particularly in the fasted state as it is reported to be a major hurdle for developing successful gastroretentive drug delivery systems.[ 105 ] Consequently, clinical evaluation is necessary to judge the efficacy of the 4D printed gastroretentive materials for human use.

3.2. Esophageal Drug Delivery

3.2.1. Anatomy and Physiology of Esophagus

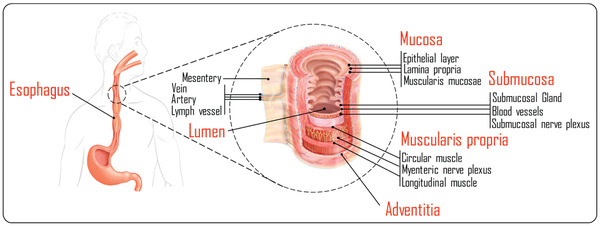

In order to understand the challenges of delivering therapeutics to the esophagus, it is crucial to get a brief insight into its anatomy and physiology. The esophagus is a tube with a length of ≈23 cm[ 106 ] and a diameter of 2.5 cm[ 107 ] and it represents the pathway through which the ingested solid and liquid substances pass to reach the stomach. It is composed of four consecutive layers including mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, and adventitia as illustrated in Figure 4 . The tough layer of stratified squamous epithelium that covers the esophagus, provides it with the required resistance to withstand the bolus abrasion induced distress. Similarly to the saliva, the pH of esophageal region ranges from ≈6 to 7.[ 108 ] Moving from the esophagus toward the stomach, particularly at the junction between both organs where the esophageal sphincter lies, the epithelial liner converts to the gastric epithelial tissue that is lined by mucosal layer which provides the required tissue protection from the acidic conditions in the stomach.[ 109 ] During relaxation, the esophagus is much folded while expansion of the esophagus occurs during swallowing which is accompanied with a peristaltic wave pushing the boluses or saliva down. The occurrence of peristaltic waves makes the transit time of formulations in the esophagus usually as short as 10 to 14 s.[ 111 ] There is also an unstirred water layer covering the surface of esophageal epithelium, which contains, in addition to water, submucosal glands secretions and substances from the swallowed saliva.

Figure 4.

The anatomy of the esophagus. Reproduced with permission.[ 110 ] Copyright 2021, Elsevier.

3.2.2. Current status of Esophageal Drug Delivery and Its Challenges

The esophagus is susceptible to a number of pathological conditions such as esophageal infections that frequently occur especially in immunocompromised patients[ 111 ] such as esophageal candidiasis.[ 112 ] Additionally, a number of disorders may affect the esophagus causing malfunction of esophageal motility known as esophageal spastic disorders, for instance, achalasia, nutcraker esophagus, and diffuse esophageal spasm.[ 113 ] These diseases are often, but not exclusively diagnosed in patients suffering from perceptual or cognitive dysfunctions as a secondary result of dementia, stroke or chronic degenerative diseases. Another esophageal pathology is gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which occurs as a result of increased acid reflux along with the bile substances moving up from the stomach back to the esophagus. Esophageal cancer is one of the most fatal cancer types globally, at the same time it is one of the least studied cancers.[ 114 ] It is ranked as the eighth most common type of cancer and the sixth most reasons of cancer mortality in the world.[ 115 ] It can be categorized into two subtypes: adenocarcinoma and squamous carcinoma.[ 116 ] Different treatment strategies are available to treat esophageal cancers depending on the disease stage including endoscopic management, surgery which may be associated with chemotherapy,[ 117 ] systemic chemotherapy, and photodynamic therapy.[ 118 ] Further, eosinophilic esophagitis is a local immune disease that affects the esophagus and it is characterized by inflammation with predominance of eosinophils.[ 119 ] Due to the low esophageal blood supply and the presence of thick squamous cell linings, large systemic doses of drugs are usually required to deliver drugs to the esophagus in sufficient concentrations, which, however, increases the risk of side effects and toxicities. Consequently, a local drug administration will be desirable to achieve high drug concentration at the site of action. However, the local drug delivery is very challenging as a result of the short residence time in the esophagus. There are a number of challenges that need to be taken into consideration while designing esophageal drug delivery systems including 1) the necessity of selecting the optimum dose, 2) the inconsistent saliva clearance which results in variation in the bioavailability, 3) the short residence time of the materials in the esophagus, and 4) the possibility of swallowing the dosage form.[ 120 ] The conventional oral formulations for example mouth washes and rinses are of limited benefits in achieving local delivery of the drugs to the esophagus as they fail to maintain sufficient therapeutic drug concentrations in saliva for an extended period of time. Therefore, alternative local drug delivery systems were developed to attain sustained drug concentrations in saliva including oral retentive buccal tablets, sustained release films, chewing gums, buccal gels, pastes, liquid filled lozenges, and bioadhesive liquids. Alginate esophageal bandages (formulations that form a drug releasing film on the esophageal surface) have been reported in literature as an adhesive drug delivery system for therapeutic management of GERD.[ 121 , 122 ] Moreover, chewing gum can be used to enhance the solubility of poorly soluble drugs as they can prolong the residence of drugs in saliva which can be beneficial in esophageal drug delivery.[ 123 ] Among esophageal drug delivery approaches, there is the endoscopic therapy, which provides significant relief of the symptoms eliminating the complications concomitant to the chronic therapies.[ 120 ] The mechanism for drug targeting to the esophagus is most commonly relying on the mucoadhesion.[ 124 ] Other targeting approaches comprise magnetic targeting in which a mucoadhesive polymer embedding magnetic particles can be directed to a target site in the esophagus employing an external magnetic field[ 125 ] in addition to implantable devices that can be placed endoscopically to treat GERD through stimulation of the lower sphincter of the esophagus.[ 126 ] In the context of managing esophageal tumors, self‐expanding metal,[ 127 ] and plastic stents[ 128 ] are commonly used to immediately relieve esophageal dysphagia. The plastic stents are usually used in the benign conditions,[ 129 ] while the metal type has wide applications in cancers induced esophageal obstruction.[ 130 ] The plastic stents possess a number of advantages over the metal type including their affordable costs, ease of delivery and removal, limited tissue complications and treatment efficacy. Nevertheless, plastic stents exhibit high migration potential.[ 131 , 132 ] On the other hand, metal stents have mesh structure permitting them to be compressed and expand as required.[ 133 ] Unfortunately, the use of the metal stents may be associated with some complications related to their mesh structure such as the growth of tumor tissue inside the stent, stent migration, tissue perforation, and bleeding.[ 134 ] Generally, the stents are not only used to clear the esophageal obstruction but also the stents may be loaded with drug‐containing polymer matrix in certain cases to achieve prolonged and local drug delivery of chemotherapy.[ 135 ] Recently, the evolution of 3D printing technology has inspired researchers to innovate a novel local delivery device (EsoCap) loaded with fluorescein sodium for long‐lasting esophageal targeting to treat eosinophilic esophagitis; the device has been assembled of various parts including a slitted capsule, a mucoadhesive rolled‐up film, a sinker device in addition to a retainer as illustrated in Figure 5A.[ 136 ] Moreover, this device can be used as a platform to adapt many drugs to treat many esophageal diseases through efficacious prolonged local delivery of therapeutics. Generally, the ideal esophageal drug delivery system should be amenable to reliably retain in the esophageal region for enough time to allow delivering the drugs to their site of action in sufficient concentrations. Additionally, the system should be administered and retrieved easily with minimum invasion. Further, the safety of the delivery system should be guaranteed such as avoiding the possible obstruction of the esophagus.

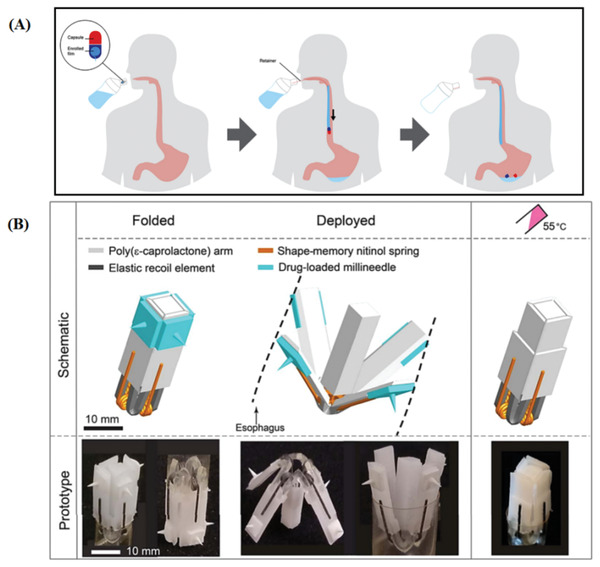

Figure 5.

A) A presentation illustrates the application of EsoCap, which composed of hard gelatin capsule containing a sinker to decrease the buoyancy and mucoadhesive enrolled film and retainer thread, using the 3D printed applicator. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons CC‐BY license.[ 136 ] Copyright 2020, Elsevier. B) Schematic presentation of the flower‐shaped esophageal drug delivery system illustrates its composition, the folded configuration prior to administration, its deployment upon reaching the esophagus and recovery of its original shape upon thermal triggering of nitinol wires. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons CC BY license.[ 29 ] Copyright 2019, the Authors. Published by AAAS.

3.2.3. The Potential Opportunities of 4D Printing in Esophageal Drug Delivery

In the lights of making the best use of combining the 3D printing technology with shape memory effect in addition to getting inspiration from a blooming flower, a recent study has reported an innovative esophageal drug delivery system with the size of a capsule. The delivery system has the capability of deployment, utilizing its elastic parts, and the recovery of its original shape based on the thermoresponsive shape memory effect of the integrated nitinol springs. The structure of the system has been built employing four PCL arms joined together to a PCL central core by means of four elastic parts made of ellastollan 1185A. For the purpose of thermal actuation of the system, four wires made of biocompatible nitinol have been fitted in the design. The system has been loaded with biodegradable millineedles incorporating budesonide. Upon folding the system, elastic energy is trapped in the elastic parts of the system, this energy releases once the system reaches the upper part of the esophagus causing deployment of the system and contact of the arms with the esophageal wall with subsequent penetration of the millineedle into esophageal mucosa. Eventually, the system can be thermally actuated by the uptake of warm water (55 °C) to recover the original folded shape to facilitate a safe passage to the stomach (Figure 5B).[ 29 ] Interestingly, the system has the potential to advance the esophageal drug delivery through providing highly functional systems with higher safety as the thermally actuated in situ disintegration of the device can be a safer elimination procedure compared to the endoscopic retrieval of esophageal delivery devices. Another study reported the fabrication of a 3D printed biodegradable stent to solve the problems associated with the currently available stents regarding the migration and tumor ingrowth. The stent has a tube shape with spirals to prevent the migration to the stomach and it was fabricated using flexible thermoplastic polymer (polyurethane) to give the stent the flexibility required to deploy and expand, along with the stiff poly(lactic acid) to impart the stent an adequate mechanical strength to clear the obstructed esophagus and to slow the rate of degradation thus reduce the requirements of multiple interventions. The developed flexible stent exhibited the capability of being compressed to be fitted in the delivery catheter followed by rapid expansion and shape recovery after being released from the catheter. Further, the stent degraded slowly with no significant change in its mechanical strength after 3 months making it a platform device for chemotherapeutic delivery with possible tuning drug release through controlling the rate of polymer degradation. The stent was developed in a dense structure, which has the advantage to prevent tissue ingrowth compared with mesh structure devices.[ 137 ] Fouladian et al. have recently reported fabrication of 5‐fluorouracil‐eluting 3D printed flexible polyurethane stent with a dumbbell‐shaped design where both ends were printed of drug free polyurethane and were in the shape of mesh tapered flanges to prevent the migration of the stent from the esophagus. The central part of the stent was the drug loaded region thus it can be located directly to be in contact with the tumor tissues. The designed stent was elastic, in response to compression it takes a temporary shape followed by rapid recovery of its original shape to resist the possible migration during peristaltic waves. The stent could sustain the in vitro release of 5‐fluorouracil for a period up to 110 days. Permeability investigations via porcine esophageal mucosa showed even slower release.[ 138 ] Another recent study has outlined the fabrication of 3D printed esophageal rings incorporating fluticasone propionate for the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. The rings have been fabricated utilizing biocompatibile resins; thus PCL dimethacrylate was synthesized to allow crosslinking via photopolymerization upon 3D printing process. The drug could be incorporated in the ring either prior to or after the 3D printing. Drug release was faster in the case of drug loading after printing. The ring has been designed to be able to deform into a temporary shape to allow administration and then underwent shape recovery after removal of the compression force.[ 139 ] Consequently, 4D printing technology has the potential to fabricate diverse esophageal drug delivery systems relying on the shape configuration which imparts the systems favorable properties including ease of administration with minimally invasive procedures, self‐fitting ability, reduced liability to migration and eventually the ability to be retrieved safely. Moreover, 4D printing permits the use of various smart materials that can be invested to tailor the pattern of drug release from the shape changing‐esophageal drug delivery systems. However, further studies yet need to be conducted to ensure the functionality and the safety of these systems and to pave the way for their future use in humans.

3.3. Intravesical Drug Delivery

The intravesical drug delivery represents drug administration by means of a catheter directly to the urinary bladder.

3.3.1. Anatomy and Physiology of the Bladder

In order to better understand this drug delivery approach, it is crucial to highlight some information about the intrinsic structure and the physiological function of the bladder. The bladder is a hollow organ in the human body that functions to store and dispose the urine delivered from the kidneys through the ureters; thus allowing clearance of waste materials from the blood.[ 140 , 141 ] The storage of the urine in the bladder is a short‐term repetitive process with a bladder capacity of almost 400–600 mL of urine as an average volume.[ 142 ] Nevertheless, the collection of volumes of ≈150–200 mL of urine provoke an urge for urination that is governed by the myovesical plexus in the urinary bladder as it sends signals to the detrusor muscle which in turn controls the rate and the extent of the urination process.[ 143 ] The bladder wall is composed of several layers such as the mucin layer and urothelium which is known to be the bladder permeability barrier (Figure 6 ). The urothelium plays its role as an impermeable barrier to separate the urine from the systemic circulation, thus preventing the passage of poisonous and infective materials into the blood.[ 144 , 145 ]

Figure 6.

Schematic illustration shows the anatomy of the urinary bladder and the bladder permeability barrier (urothelium).

3.3.2. Current Status of Intravesical Drug Delivery and Its Challenges

There are a number of bladder related diseases that affect patients quality of life for instance bladder hyperactivity, recurrent pathogenic infections, urinary incontinence, interstitial cystitis, and bladder cancer.[ 145 ] The treatment of bladder disease usually involves both systemic and local delivery approaches, with the latter approach being more favorable as it provides sufficient concentrations of drugs at the desired location with less systemic exposure. Hence, the local drug delivery is particularly applied in case of interstitial cystitis and bladder cancer and it involves intravesical instillation of liquid drug formulations by means of a transurethral catheter which enables reaching the bladder cavity from externally.[ 141 , 146 ] Unfortunately, there are a number of limitations for intravesical drug delivery involving the difficulty of attaining therapeutic concentrations of the drugs due to the continuous dilution process of the drugs with the urine and the wash out of drugs concomitant to the urination process.[ 147 ] The residence time of the drugs in the bladder is short (commonly 2 h), which necessitates a frequent drug dosing with a consequent decrease in the patient compliance.[ 148 ] Furthermore, the poor penetration of the drugs through the impermeable urothelium barrier limit the efficacy of the drugs. When it comes to the administration procedure, it is noteworthy to say that the frequent and chronic use of catheters is usually associated with an increased risk of bacterial infections as well as mucosal injuries which may worsen the whole disease conditions. Besides, the invasive nature of the catheterization procedure and the related discomfort result in lack of patient adherence to their treatment schedules.[ 149 ] In recent years, much attention has been paid to finding new formulation strategies to improve the delivery of drugs to the bladder, with great emphasis on liposomes, smart hydrogels, and nanoparticles. Additionally, the use of indwelling devices has been also investigated. These devices provide a retention in the bladder upon insertion due to their spatial encumbrance that hinders them from being washed out with the urine.[ 150 ] A special attention must be given to the elimination method of these indwelling implants as it can be eliminated spontaneously or manually depending on the nature of the fabricating materials being biodegradable or not.[ 151 ] Some pharmaceutical companies developed indwelling devices such as UROS infusion pump that was developed by Situs Corporation to be filled with oxybutynin externally after insertion into the bladder. Moreover, TARIS Biomedical company has produced two osmotic pump based devices named as GemRIS and LiRIS to release gemicitabine and lidocaine, respectively, over a period of 2 weeks. Both devices have a pretzel‐shaped design that can be elongated to fit into an insertion catheter depending on the superelasticity of nitinol.[ 152 ] Overall, an ideal intravesical drug delivery system should 1) be small enough in order to avoid obstruction of the urinary tract or hampering the urination and to decrease patient discomfort, 2) retain in the bladder for sufficient time and resist drainage with urine, 3) enhance drug penetration through the urothelium, and 4) be degradable or easily removed without transurethral retrieval procedures.[ 152 , 153 , 154 ]

3.3.3. The Potential Opportunities of 4D Printing in Intravesical Drug Delivery

The evolution of 4D printing technology has led to fabrication of promising retentive intravesical drug delivery systems, based on their shape configuration properties. These properties enable existence of the delivery system in a shape that permits its administration easily through catheters followed by retention in the bladder due to shape or size change. Melocchi et al.[ 155 ] have reported the fabrication of 4D printed PVA based retentive intravesical drug delivery systems employing two 3D printing hot processing techniques which are fused deposition modeling and hot melt extrusion. Selection of PVA relied on a number of favorable characteristics of this polymer such as feasibility for hot processing by the used 3D techniques, viability to prolong drug release as it interacts slowly with aqueous phases, being bioerodible so it degrades with time without any requirement for invasive removal procedures from the bladder, exhibition of water actuated shape memory effect, existence in various molecular weights which permits the control of drug release and eventually its high safety profile. The authors fabricated a helix‐shaped device (Figure 7A), that could be temporarily deformed into a bar shape to ease administration through a catheter. Upon contact with warm urine it was shown to recover the helix shape with a resultant intravesical retention in the bladder. Moreover, this shape can decrease patient discomfort by acting as a spring that can compress itself and reduce its length; thus resisting the muscular contraction derived mechanical stress that occur during urination. The fabricated device could control the release of caffeine that was used as a model drug in that study for 2 h. Despite the novelty of this work, further research needs to be conducted to determine whether such a delivery system can be loaded with clinically relevant actives and whether prolonged release is possible as a release profile over 2 h period is comparable to the normal residence time of the drugs in the bladder. However, the release profile may be easily extended, as suggested by the authors, by blending higher molecular weight polymers, changing the amount of the plasticizer or incorporation of drug release modifiers. Meanwhile, this work opened a new perspective for the application of 4D printing to develop intravesical drug delivery systems.

Figure 7.

A presentation illustrating the utilization of shape configuration in fabricating intravesical drug delivery systems. A) The shape recovery of PVA intravesical devices fabricated using hot melt extrusion and fused deposition modeling. The devices exhibit an original shape of helix and a temporary (I) shape. Reproduced with permission.[ 155 ] Copyright 2019, Elsevier. B) Intravesical drug delivery systems, 3D printed with stereolithography and incorporated with different concentration of lidocaine as depicted in the figure: solid 10% lidocaine‐loaded system (top left), solid 30% lidocained‐loaded system (top middle), and solid 50% lidocaine‐loaded device (top right). The ruler scale is in cm. Reproduced with permission.[ 156 ] Copyright 2020, Elsevier.