Abstract

A generic, facile, and waterborne strategy is introduced to fabricate flexible, low‐cost nanocomposite films with room‐temperature phosphorescence (RTP) by incorporating waterborne RTP polymers into self‐assembled bioinspired polymer/nanoclay nanocomposites. The excellent oxygen barrier of the lamellar nanoclay structure suppresses the quenching effect from ambient oxygen (k q) and broadens the choice of polymer matrices towards lower glass transition temperature (T g), while providing better mechanical properties and processability. Moreover, the oxygen permeation and diffusion inside the films can be fine‐tuned by varying the polymer/nanoclay ratio, enabling programmable retention times of the RTP signals, which is exploited for transient information storage and anti‐counterfeiting materials. Additionally, anti‐interception materials are showcased by tracing the interception‐induced oxygen history that interferes with the preset self‐erasing time. Merging bioinspired nanocomposite design with RTP materials contributes to overcoming the inherent limitations of molecular design of organic RTP compounds, and allows programmable temporal features to be added into RTP materials by controlled mesostructures. This will assist in paving the way for practical applications of RTP materials as novel anti‐counterfeiting materials.

Keywords: nacre‐mimetics, nanocomposites, oxygen barrier, room‐temperature phosphorescence

A general and facile self‐assembly strategy for fabricating high‐performance films with room‐temperature phosphorescence (RTP), based on nacre‐mimetic nanocomposite design is proposed. The laminated nanoclay endows the films with tunable oxygen permeability, and programmable retention times of RTP signals can be achieved. Applications including oxygen sensors and photolithographic RTP tags, and a new anti‐interception concept are demonstrated.

Room‐temperature phosphorescence (RTP) holds great potential for applications including afterglow materials,[ 1 ] anti‐counterfeiting materials,[ 2 ] oxygen sensors,[ 3 ] and bioimaging probes.[ 4 ] Recent developments focused on exploring new molecule structures to expand the library of RTP compounds, aiming at longer wavelength, larger Stokes shift, and metal‐free or heavy‐atom‐free organic RTP chromophores.[ 5 ] In terms of practical applications, synthesis of less toxic, cheaper, and more robust RTP materials with facile preparation processes and enabling robust application scenarios continue to be of great demand. To extend practical applications of RTP compounds, challenges like fast nonradiative decay (k nr) and oxygen quenching (k q) of the excited triplet states at ambient conditions need to be overcome to achieve efficient activation of RTP.[ 6 ] One effective approach is to keep the luminophores in a relatively rigid environment to suppress molecular motion and thus reduce k nr, preferably also suppressing k q by blocking the oxygen diffusion into the rigid matrix. Rigidification can be realized by host–guest complexes,[ 7 ] crystalline structures,[ 8 ] or via an external matrix[ 9 ] to trap the emitter in a rigid phase. Among these strategies, incorporating potential RTP chromophores into amorphous polymer matrices is highly appealing for practical applications,[ 10 ] because the polymer matrix serves not only to activate efficient RTP by suppressing the k nr and k q, but also opens possibilities for efficient polymer‐based processing.

Previous approaches utilized high glass transition temperature (T g) polymers to provide rigidity, which suppressed k nr and promoted RTP efficiency, while at the same time providing some oxygen protection.[ 11 ] However, these high‐T g polymers, for instance polyacrylamide,[ 12 ] usually lead to brittle materials with processing challenges. Additionally, polymer bulk phases have intrinsic limitations in terms of their oxygen barrier. Indeed, for some chromophores, it was revealed that reducing oxygen quenching plays a more important role than suppressing molecular relaxation to activate RTP.[ 13 ] Unfortunately, oxygen sensitivity is an inherent property that can hardly be modified in a molecular design of RTP chromophores and therefore extra oxygen barriers are necessary on the materials design level,[ 14 ] yet at present, facile strategies for extreme oxygen barriers are lacking.

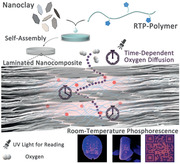

Recently, we and others have identified that highly reinforced nacre‐inspired lamellar nanocomposites prepared from alternating polymer/nanoclay stacks provide outstanding oxygen barrier properties, surpassing ordinary polymers by orders of magnitude.[ 15 ] Enhanced oxygen barrier properties arise from well‐exfoliated, perfectly aligned nanoclay sheets, and the tortuous pathway and gas barrier depend on the volume fraction, degree of alignment, and nanoclay aspect ratio (Scheme 1 ). Additionally, such bioinspired nanocomposites provide outstanding mechanical properties,[ 16 ] glass‐like transparency,[ 17 ] electrical or thermal conductivity,[ 18 ] and fire retardancy,[ 19 ] opening up possibilities for multifunctional hybrid materials. Furthermore, approaches to nacre‐mimetic films can be scalable based on simple evaporation‐induced self‐assembly.[ 16a ]

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of preparation and structure of the RTP‐copolymer/nanoclay nacre‐mimetic nanocomposite. The laminated nanoclay structure provides tunable oxygen barrier property that serves to mitigate the quenching effect from ambient oxygen on the triplet state of the RTP chromophores and thus controls the retention time of phosphorescence emission.

We hypothesized that these excellent features of nanoclay‐based nacre‐inspired nanocomposites, especially high oxygen barrier, transparency, and mechanical durability, could critically cross‐fertilize the field of RTP materials. Indeed, here we show the first example of RTP nacre‐mimetic nanocomposites with highly efficient RTP performance, and we demonstrate how structural variations in the hybrid films allow tunable RTP behaviors (light‐up and RTP retention) due to tunable oxygen permeation. We showcase that the merger of nacre‐inspired design and RTP materials can be used to make efficient oxygen sensors, rewritable patterns for transient information storage, and anti‐counterfeiting materials that allow for anti‐interception properties.

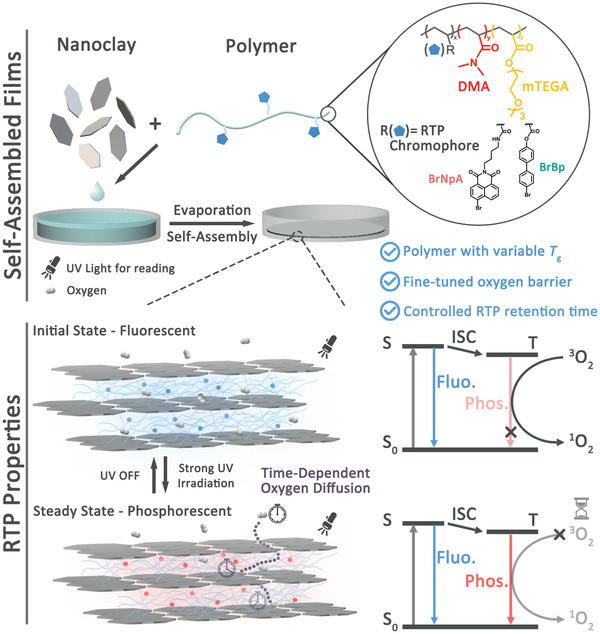

One crucial challenge for achieving RTP nacre‐mimetic films lies in incorporating potential phosphorescent components into well‐ordered laminated structures at high fractions of aligned inorganic nanoplatelets, and preferably maintaining good mechanical properties. Since it is known that the T g modulates both the mechanical properties and the k nr, a compromise needs to be found. To this end, we synthesized a series of poly[(N,N‐dimethylacrylamide)‐co‐(2‐[2‐(2‐methoxyethoxy)ethoxy]ethyl acrylate)] (DMA x mTEGA y , x and y are the molar fractions of DMA and mTEGA in the copolymers) copolymers with varying T g and incorporated a RTP chromophore 4‐bromo‐1,8‐naphthalic anhydride derivative (BrNpA) as comonomer (Figure S1, Supporting Information).[ 20 ] 1H NMR shows the modulated composition (Figure 1a, molecular weights and Đ in Table S1, Supporting Information), and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) shows a composition‐dependent tunable T g within a wide range from −56.3 °C for the BrNpA2mTEGA98 to 99.2 °C for the BrNpA2DMA98 (Figure 1b). All copolymers have a chromophore content of ≈4 wt% as determined by UV–Vis (Table S1, Supporting Information).

Figure 1.

Characterization of RTP‐copolymers and lamellar nacre‐mimetic nanocomposites. a) Chemical structure, 1H NMR spectra, and b) DSC thermograms of copolymers with corresponding T g values. c) Photographs of BrNpA2DMA79mTEGA19/NHT (50/50 w/w) film at: i) initial state; ii) steady state after 30 s under 365 nm light irradiation; and iii) a pure BrNpA2DMA79mTEGA19 polymer film in a Petri dish after 30 s under 365 nm light irradiation, which does not develop phosphorescence (control). d) Photographs showing flexibility and transparency of a BrNpA2DMA79mTEGA19/NHT (50/50 w/w) film. e) Cross‐sectional SEM images and f) 1D X‐ray diffractogram of BrNpA2DMA79mTEGA19/NHT (50/50 w/w) films with varied polymer/nanoclay ratio and the corresponding d‐spacing between nanoclay layers (inset).

Polymer/nanoclay nanocomposites films were then prepared using the set of copolymers by facile film casting using a synthetic NHT nanoclay with a very high aspect ratio of diameter/thickness of 750.[ 16a ] During film casting, self‐assembly of the nanoclays into alternating polymer/nanoclay layers takes place. Such films are known to present excellent oxygen barrier properties down to ≈0.005 cm3 mm−1 m−2 day−1 atm−1.[ 15 , 16 ] With the major goal to tune the fade‐away time of the RTP signals (defined as RTP retention time) of the films, which is highly dependent on the oxygen permeation and diffusion rate in the polymer/nanoclay nanocomposite, our strategy was to adjust the polymer/nanoclay ratio to obtain laminated structures with tunable tortuosity and hence oxygen diffusion. To this end, we varied the polymer/nanoclay weight ratio from 50/50 to 60/40, 70/30 and 80/20, giving four films with similar thickness around 22 µm (Table S2, Supporting Information). Cross‐sectional scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images indeed confirm the layered arrangement and nacre‐mimetic nanoclay orientation (Figure 1e). X‐ray diffraction (XRD) measurements confirm increasing d‐spacings between the nanoclays from 4.2 to 7.1 nm (as calculated from the primary diffraction peak), when increasing the polymer content from 50/50 to 80/20 (Figure 1f).

To investigate the RTP properties, we subjected the films to UV irradiation in the absorption region of BrNpA (365 nm),[ 12a ] during which the UV‐sensitized triplet state of BrNpA converts the entrapped 3O2 into 1O2 by nonradiative energy transfer, before its phosphorescent transition from the triplet (T1) to the ground state (S0) occurs (Scheme 1). This light‐up process depends on the amount and diffusivity of O2 and the fade‐away time corresponds to the O2 diffusion from the outside into the film. The efficacy of the phosphorescence emission yet also depends on the molecular constraints to prevent free nonradiative relaxation (k nr)—independent of the O2 content. The resulting films display an increase in RTP intensities with higher T g when fully activated (Figure S2b, Supporting Information). This correlation is in accordance with the principle that polymer matrices with higher T g suppress nonradiative decay (k nr) and therefore enable brighter RTP. However, since high T g polymers as in BrNpA2DMA98/NHT (50/50 w/w) lead to excessively brittle nacre‐mimetics, we focused on BrNpA2DMA79mTEGA19 as an optimal polymer for further investigation because it features a relatively low T g of 29.7 °C to realize good flexibility and mechanical durability, while at the same time providing satisfactory phosphorescence intensity.

To underscore the effect of the lamellar nacre‐mimetic structure on the activation of RTP, Figure 1c compares the RTP behavior of BrNpA2DMA79mTEGA19/NHT (50/50 w/w) film before (i) and after (ii) 30 s UV irradiation (0.954 mW cm−2) versus (iii) the pure polymer BrNpA2DMA79mTEGA19 after 30 s UV irradiation (0.954 mW cm−2) under a UV hand lamp (0.023 mW cm−2) at 50% relative humidity (%RH). The nanocomposite film gives rise to a clear RTP light‐up process under 365 nm UV irradiation as anticipated (i→ii), while the pure copolymer (iii) does not show any obvious phosphorescence emission (Figure 1c). This striking contrast confirms that the gas barrier provided by the well‐ordered laminated mesostructure allows to efficiently activate the phosphorescence emission by preventing the ambient oxygen from diffusing inside the film and quenching the excited triplet state of the RTP chromophores. It is noteworthy that the BrNpA2DMA79mTEGA19/NHT film (50/50 w/w), despite using a polymer with a T g near room temperature, possesses a RTP quantum yield (Φ p) of 6.6% (Table S3, Supporting Information), a value comparable to Φ p = 7.4% of our previously reported polyacrylamide matrix[ 12a ] with a much higher T g. This highlights the remarkable effect of suppressing k q in activating RTP as an important principle in designing high‐performance RTP materials. Due to nanoconfinement effects of the nanoclay layers (few nanometers, XRD in Figure 1f), it is known that polymer motion can be altered compared to bulk polymer.[ 21 ] Macroscopically, the films exhibit good flexibility and can be easily cut into desired shapes. Additionally, they are highly transparent under normal visible light due to the use of the synthetic nanoclay (Figure 1d).

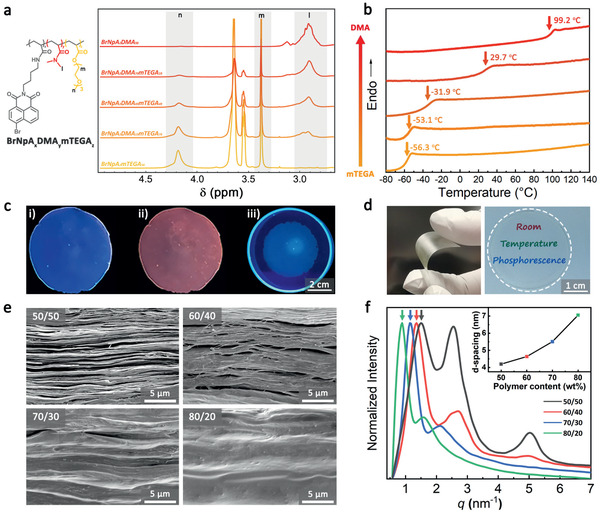

The nanoclay loading‐dependent oxygen permeability of these films was validated by monitoring the RTP light‐up and fade‐away process under UV irradiation. Films with higher polymer/nanoclay ratios clearly show a slower light‐up process and shorter retention times (Figure 2a), indicating a faster oxygen permeation and diffusion rate. Note that the light‐up process within different timescale reflects the difference not only in oxygen permeability but also in initial oxygen content of the films that is related to the different polymer/nanoclay ratio. To quantitatively study the RTP retention time, the fade‐away process of the films was monitored by recording the phosphorescence emission peak at 583 nm (Figure 2b). The RTP intensity of each film was recorded with probing intervals of 600, 900, 1800, and 3600 s after the films were fully activated (Figure 2d; Figure S3 and Table S2, Supporting Information). Since each measurement excites and inevitably repromotes the RTP, the global retention time obtained for shorter test intervals is expectedly longer. The results display a clear trend that the RTP retention time increases almost linearly with the higher nanoclay content. For instance, for a specific set of data at the test interval of 900 s, four films with nanoclay content from 20 to 50 wt% exhibit retention times increasing from 4.7 to 30.8 h (Figure 2c). The fine‐tuned retention times of the RTP fade‐away process demonstrate the successful implementation of tunable gas diffusion properties into the RTP materials based on the ordered nanoclay composite structure. The distinct relationship allows the design of controlled k q to expand the functionalities for programmable RTP properties.

Figure 2.

Time‐dependent photoluminescence properties of nacre‐mimetic RTP films. a) Photographic image series of the light‐up and fade‐away process of BrNpA2DMA79mTEGA19/NHT films with varied polymer/nanoclay ratio. b) Normalized phosphorescence intensity of BrNpA2DMA79mTEGA19/NHT (50/50 w/w) film during light‐up and fade‐away process at a test interval of 900 s (emission at 583 nm). Insets show the full photoluminescence spectra during light‐up and fade‐away. c) Normalized phosphorescence intensity (at 583 nm) of BrNpA2DMA79mTEGA19/NHT films with varied polymer/nanoclay ratio at a test interval of 900 s. Inset shows the enlarged region of 2–12 h. d) RTP fade‐away times (retention times) of BrNpA2DMA79mTEGA19/NHT films with varied polymer/nanoclay ratio at different test intervals (Figure S3, Supporting Information).

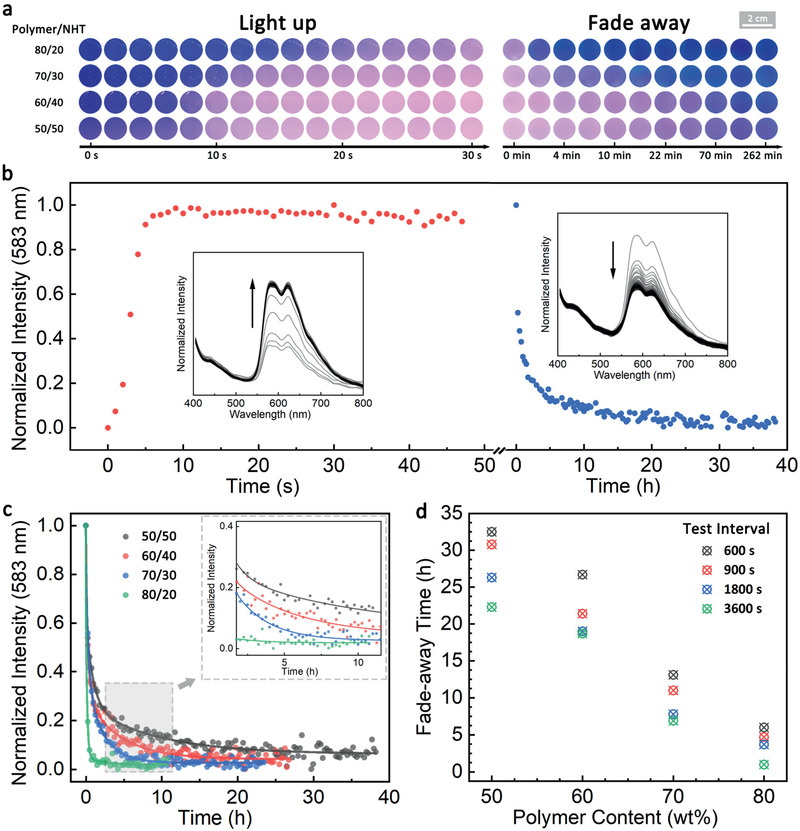

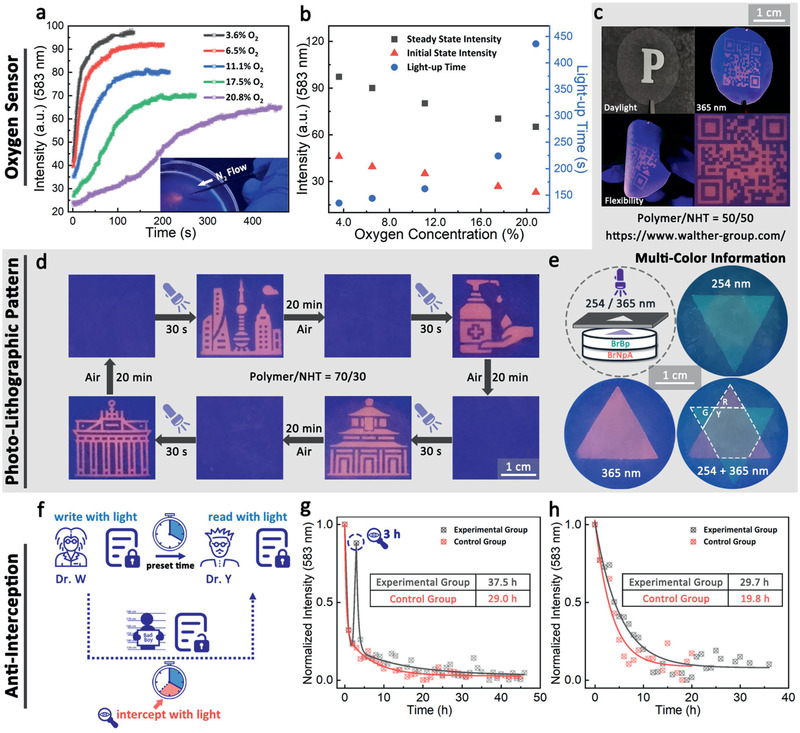

One advantage of the tunable design is to make precise oxygen sensors. In principle, to work as efficient luminescent oxygen sensors, the RTP materials should possess proper oxygen diffusion rates (appropriate k q) that allow sufficient RTP activation at a given relatively small nonradiative decay rate (low k nr) in a target oxygen concentration range.[ 3a ] However, this requirement can hardly be fulfilled by traditional single‐component polymer matrices, which face the dilemma that the oxygen diffusion cannot be independently designed from the matrix rigidity represented by T g of the polymer. Our strategy overcomes this limitation by providing controlled tortuosity as engineered via the nanoclay content through an additional mesoscopic structural layer orthogonal to T g. For example, to fit the range of oxygen concentration below 21%, the 70/30 film was picked and exposed to a tube with controlled nitrogen/air flow inside a spectroscopic setup. The film was lit up by irradiation at 365 nm with a fixed distance, and the RTP intensity of the light‐up process was recorded. As shown in Figure 3b, both the intensities of the initial state and steady state (I s) show a negative correlation with oxygen concentration and a good linear fitting between 1/I s and partial pressure of O2 () can be confirmed (Figure S4, Supporting Information). Additionally, the light‐up time, which depends not only on the different amount of oxygen stored in the film but also the diffusion rate of external oxygen into the film, shows a larger correlation slope within the high oxygen concentration region. This represents a higher sensitivity for high oxygen concentration measurement. Importantly, the storage and diffusion rate of oxygen for the films can be fine‐tuned, which provides opportunity to enhance the accuracy for oxygen sensing in different oxygen concentration range.

Figure 3.

Demonstration of applications based on the RTP nacre‐mimetic nanocomposites. Oxygen sensors: a) Phosphorescence intensity at 583 nm of BrNpA2DMA79mTEGA19/NHT (70/30 w/w) film under 365 nm irradiation at different oxygen concentration. Inset: spatially selective phosphorescence of a BrNpA2DMA79mTEGA19/NHT (70/30 w/w) film under nitrogen flow through a needle (365 nm irradiation). b) The initial and steady phosphorescence intensity and the light‐up time, determined as the total time of light‐up process, of BrNpA2DMA79mTEGA19/NHT (70/30 w/w) film at different oxygen concentration. Information coding: c) Photographs of the BrNpA2DMA79mTEGA19/NHT (50/50 w/w) film with photolithographic QR code pattern in front of a photomask under daylight and under 365 nm light. The films are flexible and can be bent. d) Transient photolithographic patterning of BrNpA2DMA79mTEGA19/NHT (70/30 w/w) film with fast writing and time‐dependent self‐erasing properties. Icons in (d) were made by Linector and Eucalyp from www.flaticon.com and are reproduced with permission. Permission for further reuse should be directed to Flaticon. Dual color information storage: e) Schematic illustration and photographs of the orthogonal multilayer patterning under 254/365 nm UV light irradiation using a combination of two RTP chromophores (BrBp and BrNpA). G, R, and Y represent the emission color of green, red, and yellow, respectively. Anti‐interception test: f) Schematic illustration of anti‐interception concept and g,h) the corresponding RTP retention time measurement in a global perspective (g) and a recipient perspective (h) to demonstrate the detection of prolonged retention time induced by interception. h) The light up event is at −4 h and the interception event is at −1 h taking into account a hypothetical transfer time of 1 h between interception and receiving by the recipient.

To demonstrate potential practical applications as phosphorescent tags for self‐erasable transient information storage and anti‐counterfeiting, we irradiated the films with 365 nm UV light through a photomask at a relatively high intensity (0.954 mW cm−2) for 30 s. For the reading process, the mask was removed and the film was irradiated at the same wavelength but with a much lower intensity (0.023 mW cm−2) to avoid the repromotion of RTP of the whole film. Figure 3c depicts patterned information—also on bent films—and Figure 3d demonstrates repeated information imprinting. Importantly, a programmable sequential light‐up process of photolithographic patterning can be achieved based on the different oxygen permeability of films with varied polymer/nanoclay ratios (Movie S1 and Figure S5, Supporting Information), showing its potential in the application as anti‐counterfeiting material. The films can be photo‐patterned for multiple times with excellent reversibility as shown for 15 cycles in Figure S3d, Supporting Information.

To demonstrate the versatility of the nacre‐inspired design method, one piece of a nacre‐mimetic film displaying green RTP emission based on a different chromophore BrBP (incorporated into a similar copolymer and nacre‐mimetic) with shorter excitation wavelength and RTP emission was prepared (Figure S6, Supporting Information), and gently compressed onto the red‐emissive BrNpA2DMA79mTEGA19/NHT (70/30 w/w) film. Since BrBP2DMA79mTEGA19 with a main absorption peak at ≈270 nm shows no absorption at 365 nm (Figure S7, Supporting Information), the double‐layered film allows the orthogonal writing and reading of information on the green/red layer by 254/365 nm UV light exposure (Figure 3e). This provides more complex information with higher storage capability per unit area.

As indicated above, these features give rise to a new anti‐interception concept. Given that the only way to read the stored information is to illuminate the film by UV light, which will inevitably consume the residual oxygen in the film at a rate depending on the UV intensity, any reading attempt will leave an oxygen consumption history and thus influence the global retention time of RTP signals. It is possible to detect if the information stored has been intercepted by monitoring the global retention time on a spectrometer. Moreover, the signal of the interception history can be captured and amplified with an appropriate test interval. Using this rationale, we propose a new concept of photolithographic encryption based on the fact that the interception inevitably interferes with a “hidden” property—the self‐erasing time preset in the imprinted information—which relates to one of the principles of “quantum cryptography”: You cannot measure a quantum property without changing or disturbing it.[ 22 ] To validate the anti‐interception functionality, we lit up the BrNpA2DMA79mTEGA19/NHT (50/50 w/w) film to store the information and tested two scenarios: 1) We monitored the film continuously at a constant read‐out interval (3600 s) and included one additional interception read‐out at 3 h, and then compared the change of retention time from a global perspective. 2) Closer to practical situations, the lit‐up film was left in dark for 3 h before one interception event, and after 1 h (to simulate a transfer time), the recipient measures the remaining retention time. The retention times of the control groups were measured following the same procedure without any interception event. In each case, the interception event is a low intensity read‐out with a UV flash torch (0.126 mW cm−2) for 3 s to shortly read/intercept the information. As shown in Figure 3g,h, the retention time gets extended from 29.0 to 37.5 h for scenario 1 and from 19.8 to 29.7 h for scenarios 2. Note that even though the irradiation from UV flash torch corresponds to a quite small intensity, and the change left by 3 s irradiation is macroscopically unnoticeable, the results of retention time measurements show obvious differences, indicating the high sensitivity of our methodology.

In summary, we demonstrated a general strategy for fabricating high‐performance RTP nacre‐mimetic nanocomposites based on facile self‐assembly of nanoclay with waterborne polymers harboring the RTP chromophores. Benefiting from the excellent oxygen barrier property of lamellar nanoclay mesostructures and the restricted segmental relaxation due to the nanoconfinement of the polymer layers, both k q and k nr can be significantly reduced, which allows the use of copolymers with relatively low T g. At the same time, this is beneficial for making flexible films without excessive brittleness as known from high T g polymers. Moreover, a programmable retention time of the RTP signals can be achieved based on controlling the oxygen permeability by tuning the polymer/nanoclay ratio. This renders these films good candidates for self‐erasing RTP tags for transient information storage or anti‐counterfeiting materials. Additionally, this study proposed a novel photolithographic anti‐interception concept based on the principle that information read‐out inevitably interferes with the preset self‐erasing time of the RTP signal and leaves a traceable oxygen history.

Our new design strategy of constructing high‐performance RTP materials provides efforts from an advanced hybrid materials level to break the inherent limitations of molecular design on controlling the k q and k nr exclusively by organic synthesis approaches, and adds a programmable temporal feature to RTP signals. This enriches the functionality of RTP materials and will pave the way for their practical applications as novel transient information storage and anti‐counterfeiting materials.

Experimental Section

Synthesis of N‐(4‐(6‐Bromo‐1,3‐dioxo‐1H‐benzo[de]isoquinolin‐2(3H)‐yl)butyl)acrylamide (BrNpA)

BrNpA was synthesized according to previously reported procedure.[ 12a ] 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, δ): 8.60 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 8.53 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 8.36 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.99 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.80 (dd, J = 8.6, 7.3 Hz, 1H), 6.22 (dd, J = 17.0, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 6.04 (dd, J = 17.0, 10.2 Hz, 1H), 5.90–5.80 (br, 1H), 5.56 (dd, J = 10.2, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 4.13 (t, 2H), 3.38 (q, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 1.80–1.69 (m, 2H), 1.67–1.56 (m, 2H).

Synthesis of 4′‐Bromo‐[1,1′‐biphenyl]‐4‐yl acrylate (BrBp)

A suspension of 4′‐bromo‐(1,1′‐biphenyl)‐4‐ol (1 g, 0.004 mol, 1.0 equiv.) and triethylamine (1.22 g, 0.012 mol, 3.0 equiv.) in DCM (40 mL) was cooled to 0–5 °C with an ice bath. Acryloyl chloride (3.63 g, 0.04 mol, 10.0 equiv.) was added dropwise under N2 atmosphere. The reaction mixture was stirred for 5 h at room temperature. The reaction mixture was filtrated and washed with DCM. The filtrate was concentrated and purified by column chromatography (ethyl acetate/cyclohexane, 1/1 v/v) to afford BrBP (1.06 g, 87%) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, δ): 7.59–7.54 (m, 4H), 7.46–7.41 (m, 2H), 7.24–7.18 (m, 2H), 6.64 (dd, J = 17.3, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 6.35 (dd, J = 17.3, 10.4 Hz, 1H), 6.04 (dd, J = 10.5, 1.2 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3, δ): 164.56, 150.27, 139.29, 137.82, 132.84, 131.94, 128.72, 128.03, 127.84, 122.01, 121.69. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + NH4]+ calcd for C15H15BrNO2 +, 320.0281; found, 320.0282.

Synthesis of RTP‐Chromophore‐Based Copolymers

All copolymers were synthesized according to the procedure similar as follows. BrNpA2DMA79mTEGA19 copolymer was prepared by free radical copolymerization of BrNpA (0.02 g, 0.05 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), DMA (0.20 g, 2 mmol, 40.0 equiv.), and mTEGA (0.10 g, 0.5 mmol, 10.0 equiv.) with AIBN (0.005 g, 0.03 mmol, 0.6 equiv.) as initiator in 20 mL DMF at 70 °C for 4 h under N2 atmosphere. The reaction mixture was afterwards dialyzed against water, filtrated, and the filtrate was freeze‐dried to provide the polymer as amorphous powder.

Preparation of Nacre‐Mimetic Films by Direct Mixing and Film Casting

A 0.5 wt% NHT dispersion was added dropwise to a 0.5 wt% polymer aqueous solution under vigorous stirring. The dispersion was stirred overnight to ensure complete homogeneity and afterwards poured into Petri dishes and dried at ambient conditions (RT, 50% humidity) to obtain the films.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Supplemental Movie 1

Acknowledgements

X.Y. and J.W. contributed equally to this work. The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from VW A125456. J.W. acknowledges support from the China Scholarship Council (CSC) for a scholarship, NSFC (21788102, 22020102006, and 21722603), and X.Y. thanks the USIAS‐FRIAS for a post‐doctoral fellowship. A.J.C.K. acknowledges funding from the BMBF via a NanoMatFutur AktiPhotoPol (13N13522) research group.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Yao X., Wang J., Jiao D., Huang Z., Mhirsi O., Lossada F., Chen L., Haehnle B., Kuehne A. J. C., Ma X., Tian H., Walther A., Room‐Temperature Phosphorescence Enabled through Nacre‐Mimetic Nanocomposite Design. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2005973. 10.1002/adma.202005973

Contributor Information

He Tian, Email: tianhe@ecust.edu.cn.

Andreas Walther, Email: andreas.walther@uni-mainz.de.

References

- 1.a) Kabe R., Notsuka N., Yoshida K., Adachi C., Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 655; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Li Y., Gecevicius M., Qiu J., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Jiang K., Zhang L., Lu J., Xu C., Cai C., Lin H., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 7231; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lei Y., Dai W., Guan J., Guo S., Ren F., Zhou Y., Shi J., Tong B., Cai Z., Zheng J., Dong Y., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 16054; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Huang Q. Q., Gao H. Q., Yang S. M., Ding D., Lin Z. H., Ling Q. D., Nano Res. 2020, 13, 1035. [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Yoshihara T., Hirakawa Y., Hosaka M., Nangaku M., Tobita S., J. Photochem. Photobiol., C 2017, 30, 71; [Google Scholar]; b) Zhu C.‐Y., Wang Z., Mo J.‐T., Fan Y.‐N., Pan M., J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 9916; [Google Scholar]; c) Wu L. Z., Liu X. Q., Zhang K., Gao J. F., Chen Y. Z., Tung C. H., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 23456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Zhen X., Tao Y., An Z., Chen P., Xu C., Chen R., Huang W., Pu K., Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1606665; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhen X., Qu R., Chen W., Wu W., Jiang X., Biomater. Sci., 10.1039/d0bm00819b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Ma X., Xu C., Wang J., Tian H., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 10854; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kenry, C. Chen , Liu B., Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2111; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Febriansyah B., Neo C. S. D., Giovanni D., Srivastava S., Lekina Y., Koh T. M., Li Y., Shen Z. X., Asta M., Sum T. C., Mathews N., England J., Chem. Mater. 2020, 32, 4431; [Google Scholar]; d) Zhao W., He Z., Tang B. Z., Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 869. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hirata S., Adv. Opt. Mater. 2017, 5, 1700116. [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Zhang Z. Y., Chen Y., Liu Y., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 6028; [Google Scholar]; b) Wang J., Huang Z., Ma X., Tian H., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 9928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Fateminia S. M. A., Mao Z., Xu S., Yang Z., Chi Z., Liu B., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 12160; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jia X., Shao C., Bai X., Zhou Q., Wu B., Wang L., Yue B., Zhu H., Zhu L., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 4816; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zhou B., Yan D. P., Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1807599; [Google Scholar]; d) Feng H. T., Zeng J., Yin P. A., Wang X. D., Peng Q., Zhao Z., Lam J. W. Y., Tang B. Z., Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2617; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Li Q., Li Z., Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Al‐Attar H. A., Monkman A. P., Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22, 3824; [Google Scholar]; b) Hirata S., Vacha M., Adv. Opt. Mater. 2017, 5, 1600996; [Google Scholar]; c) Kuila S., Rao K. V., Garain S., Samanta P. K., Das S., Pati S. K., Eswaramoorthy M., George S. J., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 17115; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Law A. S., Lee L. C., Yeung M. C., Lo K. K., Yam V. W., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 18570; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Yang X. G., Zhai Z. M., Lu X. M., Qin J. H., Li F. F., Ma L. F., Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 10395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ma X., Wang J., Tian H., Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Zhang G., Chen J., Payne S. J., Kooi S. E., Demas J. N., Fraser C. L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 8942; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lee D., Bolton O., Kim B. C., Youk J. H., Takayama S., Kim J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 6325; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Su Y., Phua S. Z. F., Li Y., Zhou X., Jana D., Liu G., Lim W. Q., Ong W. K., Yang C., Zhao Y., Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaas9732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Chen H., Yao X. Y., Ma X., Tian H., Adv. Opt. Mater. 2016, 4, 1397; [Google Scholar]; b) Zhou Q., Wang Z. Y., Dou X. Y., Wang Y. Z., Liu S. E., Zhang Y. M., Yuan W. Z., Mater. Chem. Front. 2019, 3, 257; [Google Scholar]; c) Wang S. Q., Wu D. B., Yang S. M., Lin Z. H., Ling Q. D., Mater. Chem. Front. 2020, 4, 1198. [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Lin J., Wan S., Liu W., Lu W., Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 4299; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lv F.‐N., Chen Y., Liu H.‐J., Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 9981; [Google Scholar]; c) Wan S., Zhou H., Lin J., Lu W., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 8416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gmelch M., Thomas H., Fries F., Reineke S., Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau7310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Oaki Y., Imai H., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 6571; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Priolo M. A., Holder K. M., Greenlee S. M., Grunlan J. C., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 5529; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Barthelat F., Science 2016, 354, 32; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Ding F., Liu J., Zeng S., Xia Y., Wells K. M., Nieh M. P., Sun L., Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1701212; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Song Y., Gerringer J., Qin S., Grunlan J. C., Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 6904; [Google Scholar]; f) Sethy P. K., Prusty K., Mohapatra P., Swain S. K., Polym. Compos. 2019, 40, 229; [Google Scholar]; g) Eckert A., Rudolph T., Guo J., Mang T., Walther A., Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1802477; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Eckert A., Abbasi M., Mang T., Saalwachter K., Walther A., Macromolecules 2020, 53, 1716; [Google Scholar]; i) Lossada F., Hoenders D., Guo J., Jiao D., Walther A., Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.a) Das P., Malho J. M., Rahimi K., Schacher F. H., Wang B., Demco D. E., Walther A., Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5967; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhu B., Jasinski N., Benitez A., Noack M., Park D., Goldmann A. S., Barner‐Kowollik C., Walther A., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 8653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Das P., Schipmann S., Malho J. M., Zhu B., Klemradt U., Walther A., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 3738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) Li Y. Q., Yu T., Yang T. Y., Zheng L. X., Liao K., Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 3426; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jiao D., Guo J., Eckert A., Hoenders D., Lossada F., Walther A., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 20250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Qiu S., Ren X., Zhou X., Zhang T., Song L., Hu Y., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 36639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.a) Benitez A. J., Lossada F., Zhu B., Rudolph T., Walther A., Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 2417; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lossada F., Abbasoglu T., Jiao D., Hoenders D., Walther A., Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2020, 41, 2000380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.a) Saalwachter K., Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2007, 51, 1; [Google Scholar]; b) Papon A., Saalwächter K., Schäler K., Guy L., Lequeux F., Montes H., Macromolecules 2011, 44, 913. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bernstein D. J., Lange T., Nature 2017, 549, 188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

Supplemental Movie 1