Abstract

Background:

Exposure to extreme weatherly events potentially develops mental disorders among affected individuals.

Aim:

To synthesize the burden of mental disorders following impact of extreme weather events in South-east Asian (SEA) countries.

Methods:

Proposal was registered in PROSPERO register [CRD42023469788] and reported as per PRISMA-2020 guidelines. Studies reporting prevalence of mental health disorders following extreme weather events from SEA countries during 1990 and 2023 were searched on Embase, PubMed, and Scopus databases. Study quality was assessed using Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies. Overall pooled prevalence was computed using DerSimonian–Laird method for random-effects model and reported as 95% confidence intervals.

Results:

On screening 12,046 records, we included 155 studies (2,04,474 participants) for analysis. Overall burden of mental disorders was 35.31% (95%CI: 30.42%–40.21%). In subgroup analysis, studies on cyclones, India, local residents, children and adolescents, rural settings, and community settings reported higher burden of mental disorders. Depression (28.58%; 95%CI: 24.05%–33.1%) and PTSD (29.36%; 95%CI: 26.26%–32.46%) had similar prevalence. Visiting tourists to SEA region experienced fear, fear of recurrence of tsunami, nightmares, and sense of helplessness. Mental health outcomes were relatively higher in studies conducted within 1 year of events. Heterogeneity and possibility of publication bias exists among the reported studies.

Conclusion:

With the significant rise in episodes of extreme weather events in SEA region over the last three decades, mental disorders are documented in different proportions. We suggest prioritizing well-informed policies to formulate inclusive and resilient strategies on effectively identifying and treating mental health concerns among victims of extreme weather events.

Keywords: Cyclones, floods, mental health disorders, posttraumatic stress, south-east Asia, tsunami

INTRODUCTION

Extreme weather events are geographical region-specific and influenced by latitude, altitude, and local and regional geography. South-east Asian countries (SEA), namely, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, India, Indonesia, Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Timor-Leste are in close proximity to each other and share similar geographical features like hills, river valleys, plateaus, and coastlines. The extreme weather events in these SEA nations often overlap each other [Supplementary Table 1]. Storms, cyclones, coastal storm surge and erosion, and floods are the common extreme weather events in these countries.[1] Notably, over the last three decades, episodes of extreme weather events have a significant upward trend.[2,3]

Supplementary Table 1.

Common extreme weather events in South-east Asian countries

| Country | Common extreme weather events | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh | Floods, river bank erosion, storm surge, cyclones, earthquake, drought, salinity intrusion, fire, tsunami | https://www.adrc.asia/nationinformation.php?NationCode=50&Lang=en | ||

| Bhutan | Earthquake, landslides, flash flood, forest fires | https://www.adrc.asia/nationinformation.php?NationCode=64&Lang=en | ||

| Democratic People’s Republic of Korea | Typhoons, floods, droughts, landslides, snowstorms, tsunamis, earthquakes. heavy rainfall | https://public.wmo.int/en/bulletin/reducing-disaster-risk-cities-%E2%80%94-republic-korea%E2%80%99s-experience | ||

| India | Floods, cyclones, droughts, earthquakes, landslides, avalanches and forest fires | https://nidm.gov.in/easindia2014/err/pdf/country_profile/India.pdf | ||

| Indonesia | Drought, floods, landslides, sea level rise, earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, forest fires | https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/indonesia/vulnerability | ||

| Maldives | Sea level rise, coastal storm surges, floods | https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/maldives/vulnerability | ||

| Myanmar | Extreme temperature, drought, cyclones, floods, storm surge, heavy rainfall | https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/myanmar/vulnerability | ||

| Nepal | Earthquakes, flash floods, landslides, droughts | https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/nepal/vulnerability | ||

| Sri Lanka | Droughts, floods, landslides, cyclones, coastal soil erosion | https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/sri-lanka/vulnerability | ||

| Thailand | Floods, tsunamis, storms, droughts, landslides, forest fires | https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/thailand/vulnerability | ||

| Timor-Leste | Floods, drought, cyclones, earthquake | https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/timor-leste/vulnerability |

Extreme weatherly events are potential hotspots to perpetual mental health (MH) conditions.[4,5] Such events have the potential to exacerbate mental illnesses among vulnerable groups within the society like children, adolescents, women and elderly members, neglected communities, homeless individuals, as well as those grappling with preexisting mental health conditions. Scoping review on African populations also found preliminary evidence for the association between extreme weather events and adverse mental health outcomes, particularly the vulnerable communities.[6] Recent systematic reviews on worldwide population[7] and from South and Southeast Asia,[8] Europe,[9] and the United Kingdom[10] reported extreme weather events could perhaps steer deterioration of mental health. Both studies indicated that prevention of mental illness in populations vulnerable to or affected by severe weather conditions should be made a top priority in public health initiatives. Research from Bangladesh, India, and Sri Lanka revealed that tsunami as well as every year flash floods, river bank erosion displaced millions of inhabitants and affect their mental well-being.[11,12] The trauma and losses following extreme weather events, such as losing a home or job and being disconnected from family, neighborhood, and community, potentially contribute to MH disorders such as stress, anxiety, depression, and PTSD.[11,13,14] This systematic review and meta-analysis (SRMA) focused on synthesizing the burden of MH disorders following impact of extreme weather events in the SEA countries.

METHODS

The proposal was registered in the PROSPERO register [CRD42023469788] and reported as per PRISMA-2020 guidelines.[15] The studies published between January 1990 and July 2023 was searched on three literature databases, namely, Embase, PubMed, and Scopus with the keywords in PEO format [Supplementary Table 2]. The last search was performed on November 2023. We predetermined the inclusion and exclusion criteria, as peer-reviewed primary research studies reporting prevalence of MH disorders following extreme weather events (cyclone, flood, storm, and tsunami) from SEA countries. We excluded editorial, commentary, viewpoints, expert opinion, narrative and systematic reviews, and conference proceedings from the review. Studies were published between January 1990 and July 2023. The decision to begin including studies was made due to the notable rise in extreme weather events over the past 30 years.[2]

Supplementary Table 2.

Search term and search strategy for literature review

| Components | Search Terms | Search Hits on (01/11/2023) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population (P) | All age group of both sexes | |||

| Exposure (E) | ((Extreme weather*) OR Cyclone* OR Hurricane* OR (Tropical Storm*) OR (Storms Tropical) OR (Coastal storm*) OR (Storm surge*) OR Rainstorm OR Typhoon* OR Flood* OR (Flooding Catastrophic) OR (Catastrophic Flooding*) OR (Tidal Wave*) OR Tidalwave* OR (Tides Ocean) OR (Ocean Tidal) OR (Earth Tide*) OR (Tides Earth) OR (Flash flood*) OR (Seasonal flood*) OR (River flood*) OR (Coastal flood*) OR (River bank erosion) OR (Tsunami*)) | 50,183 | ||

| Outcome (O) | ((Mental Health) OR (Mental Hygiene) OR (Hygiene Mental) OR (Mental Disorder*) OR (Psychiatric Illness*) OR (Psychiatric Disease*) OR (Mental Illness*) OR (Illness Mental) OR (Psychiatric Disorder*) OR (Behavior Disorders) OR (Psychiatric Diagnosis) OR (Severe Mental Disorder) OR (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder*) OR (Stress Disorder*) OR (Stress Disorder Post-Traumatic) OR (Post-Traumatic Neuroses) OR PTSD OR (Posttraumatic Neuroses) OR (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder*) OR (Posttraumatic Stress Disorder*) OR (Stress Disorder Posttraumatic) OR (Stress Disorders Posttraumatic) OR (Stress Disorder Post Traumatic) OR (Delayed Onset Post Traumatic Stress Disorder) OR (Chronic Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder) OR (Moral Injur*) OR (Injury Moral) OR (Moral Injuries) OR (Acute Post Traumatic Stress Disorder) OR Anxiety OR Angst OR (Anxiety Disorder*) OR (Disorder Anxiety) OR (Anxieties Social) OR (Anxiety Social) OR (Neuroses Anxiety) OR (Anxiety Neuros*) OR Hypervigilance OR (Hyper-vigilance) OR (Nervousness) OR (Anxiousness) OR (Depression) OR (Depressive Symptom*) OR (Symptom Depressive) OR (Depression Emotional) OR (Traumatic) OR (Stress Disorders Traumatic Acute) OR (Stress Disorders Acute) OR (Acute Stress Disorder*) OR (Suicide*) OR (Self-Injurious Behaviour) OR (Behaviour Self-Injuri*) OR (Self Injurious Behavior*) OR (Intentional Self Injur*) OR (Intentional Self Harm) OR (Nonsuicidal Self Injur*) OR (Deliberate Self-Harm) OR (Self-Injur*) OR (Self Harm) OR (Self-Destructive Behavior*) OR (Behaviour Self-Destructive) OR (Self Destructive Behavior) OR (Parasuicid*) OR (Fatal Attempt*) OR (Disorder Mood) OR (Disorders Mood) OR (Mood Disorder*) OR (Affective Disorder*) OR (Disorder Affective) OR (Disorders Affective) OR (Depressive Disorder*) OR (Disorder Depressive) OR (Neurosis Depressive) OR (Depressive Neuros*) OR (Depression Endogenous) OR (Depressions Endogenous) OR (Endogenous Depression*) OR (Depressive Syndrome*) OR (Depression Neurotic) OR (Depressions Neurotic) OR (Neurotic Depression*) OR (Melancholia*) OR (Unipolar Depression*) OR (Adjustment Disorder*) OR (Reactive disorder*) OR (Depression Reactive) OR (Depressions Reactive) OR (Reactive Depression*) OR (Anniversary Reaction*) OR (Transient Situational Disturbance*) OR (Neurocognitive Disorder*) OR (Neuro-cognitive Disorder*) OR (Disorder Neurocognitive)) | 2,739,869 | ||

| Objective | “E” AND “O” | 3,997 (PubMed) |

Note: Population was not kept in the search criteria since, our area of interest is population of all age groups of both sexes. Settings component was not kept in search criteria since, during preliminary search; some relevant studies did not have South-east Asia or countries’ name from SEA region mentioned in the title and abstract. Thus, by including only exposure and outcome, search strategy was able to include all relevant studies in these two domains. However, all components (P, S) were considered during the screening and selection of the studies in Rayyan software

Data abstraction: Search retrieved studies from databases were imported into Rayyan software (https://www.rayyan.ai/).[16] Studies were reviewed by two independent authors. Any disagreement between two authors was resolved by consulting a third author.

Assessment of methodological quality for individual studies: Data reported in the studies were extracted using data extraction form, adapted from Cochrane data extraction form. Study quality was assessed using Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS).[17]

Statistical analysis: Meta-analysis was performed using the Stata software, version 17 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). The pooled data were reported as prevalence with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We have performed Freeman–Tukey Double Arcsine Transformation[18] to stabilize the variances and then pooled the prevalence. I2-statistics was performed to assess heterogeneity. I2 values <25%, 25–75%, and >75% were considered as mild, moderate, and considerable heterogeneity, respectively. The overall pooled prevalence was computed using the DerSimonian–Laird method for the random-effects model, which is based on the inverse variance approach for measuring weight. Forest plots were used to present the pooled estimates for overall and subgroup analyses. Subgroup analysis was done based on types of events, study settings, population characteristics, and mode of study tool deployment. For pooling with nine and above studies with heterogeneity, meta-regression was performed to evaluate the sources of heterogeneity (using the following variables: year of publication, quality score of studies, sample size, and percentage of sample who lost their kin). We considered that the selected variable could explain heterogeneity when I2 was reduced by 50%, after adjusting for the selected variable in the meta-regression model.[19] Publication bias was assessed using Funnel plots and Eggers test.

RESULTS

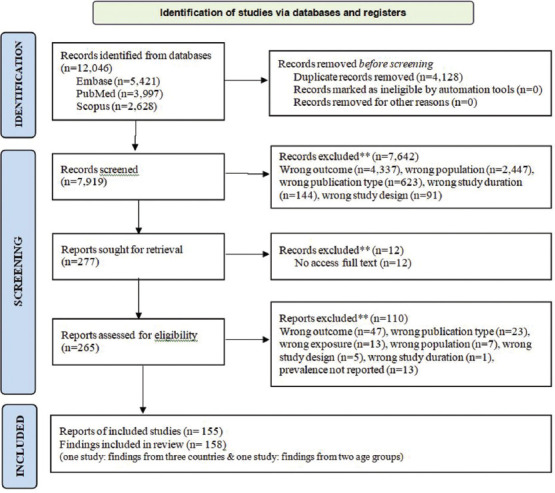

Initially, 12,046 studies were retrieved from the three databases. Thereupon, 155 studies (158 findings) (comprising of 204,474 people) were included in the analysis. The selection of studies is reported as a PRISMA flow diagram [Figure 1].[5,11,12,13,14,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169] More than three quarters of the studies (122/155) were related to tsunami. Twenty-four and nine studies were related to flood[5,14,29,32,41,43,45,60,61,64,75,81,83,90,105,106,120,127,146,147,150,153,154,159] and cyclone,[11,37,76,104,129,130,131,134,149] respectively; while three studies were related to combined weather events like flood, landslide erosion, riverbank erosion, or cloud burst.[89,128,164]

Figure 1.

Flowchart of literature search and study selection according to the PRISMA standard

Quality appraisal of studies: Regarding methodology, each selected study made explicit reference to target population. Statistical significance or precision estimates was clearly mentioned in around 86.5% studies, and in 96.8% studies, methods were described to allow study repeatability. About 92.3% studies used instruments that were trialed, piloted, or published previously. In 94.2% of studies, basic data were adequately described and 98.1% of studies presented results as described in methods. Ethical approval or participants’ informed consent was obtained in four-fifths of the studies [Supplementary Table 3].

Supplementary Table 3.

Risk of bias of selected studies by Appraisal tool for Cross-sectional Studies (AXIS)

| AXIS tool (quality assessment of selected studies) | Count (Yes) | % | Count (No) | % | Count (Don’t know) | % | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aims of the study clear? | 154 | 99.4 | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Methods | ||||||||||||

| Study design appropriate to stated aim? | 154 | 99.4 | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Sample size justified? | 103 | 66.5 | 51 | 32.9 | 1 | 0.6 | ||||||

| Target population clearly defined? | 155 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Sample frame represented target population? | 155 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Selection process likely to select subjects, representative of target population? | 155 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Measures undertaken to address and categorise non-responders? | 43 | 27.7 | 27 | 17.4 | 85 | 54.8 | ||||||

| Outcome variables appropriate to aims of study? | 153 | 98.7 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.6 | ||||||

| Instruments trialed, piloted or published previously? | 143 | 92.3 | 11 | 7.1 | 1 | 0.6 | ||||||

| Statistical significance and/or precision estimates clear? | 134 | 86.5 | 19 | 12.3 | 1 | 0.6 | ||||||

| Methods sufficiently described to be repeatable? | 150 | 96.8 | 5 | 3.2 | 0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Results | ||||||||||||

| Basic data adequately described? | 146 | 94.2 | 9 | 5.8 | 0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Does response rate raise concerns on non-response bias? | 43 | 27.7 | 41 | 26.5 | 71 | 45.8 | ||||||

| Information about non-responders described? | 42 | 27.1 | 38 | 24.5 | 75 | 48.4 | ||||||

| Results internally consistent? | 152 | 98.1 | 2 | 1.3 | 1 | 0.6 | ||||||

| Results presented described in methods? | 152 | 98.1 | 2 | 1.3 | 1 | 0.6 | ||||||

| Discussion | ||||||||||||

| Discussions and conclusions justified by results? | 152 | 98.1 | 2 | 1.3 | 1 | 0.6 | ||||||

| Were the limitations of the study discussed? | 142 | 91.6 | 13 | 8.4 | 0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Others | ||||||||||||

| Any funding sources or conflicts of interest affecting interpretation of results? | 76 | 49.0 | 76 | 49.0 | 79 | 51.0 | ||||||

| Ethical approval or consent of participants attained? | 125 | 80.6 | 28 | 18.1 | 2 | 1.3 |

Geographical locations: Forty-five studies were reported from South-east Asia, followed country-wise reporting from India (n = 44), Thailand (n = 28), Sri Lanka (n = 18), Indonesia (n = 15), and Bangladesh (n = 6). Six out of nine studies of cyclone were reported from India,[37,76,104,129,130,131] followed by two studies from Bangladesh[11,149] and one from Myanmar.[134] Over three-fifth studies (n = 17/27) reporting flood were from India, followed by Thailand (n = 5), Bangladesh (n = 4), and Malaysia (n = 1). Regarding tsunami studies, over one-third studies (n = 43/119) were reported from SEA region, followed by 18.5% studies (n = 22) from Thailand, 17.6% studies (n = 21) from India, 14.3% (n = 17) studies from Sri Lanka, 12.6% (n = 15) studies from Indonesia, and one study from Malaysia. Although three-fifth of the studies reported MH events among residents, notably, forty-eight studies reported outcome for visiting foreign tourists [50 locations, Supplementary Table 4 (356.2KB, pdf) ] during tsunami. Of these 50 locations, 54% (n = 27) and 30% (n = 15) studies were reported among tourists of Norway and Sweden, respectively. Remaining four, three, and one studies were reported among tourists from Switzerland, Denmark, and the Netherlands, respectively.

Extreme weather event period: All studies (n = 118) reported on December 26, 2004, tsunami as exposure, except one study.[20] Four studies of cyclone reported exposure as October 29, 1999.[37,76,129,130] Rest, each of the cyclone studies reported the event in the year 2008,[134] 2009,[104] 2017,[149] 2019,[131] and 2020.[11] Flood was covered in one study each in 2010[120] and 2017[147]; two studies each in 2000,[75,81] 2011-12,[29,61] 2015,[83,159] and 2019[127,150]; and four studies each in 2008,[14,41,43,60] 2014,[32,90,106,146] and 2018.[45,64,105,154] Almost two-thirds of all studies (n = 100) was initiated within 12 months of event, while eight studies were conducted between 5 and 12 years after the 2004 tsunami.

Study characteristics: Nearly nine-tenths of studies (n = 136) were community-based study, while 8.4% (n = 13) and 2.6% (n = 4) studies were school and hospital based, respectively. Only a single study was reported from college settings.[152] Most of the school-based studies reported MH disorders of 9–17 years age range students. Furthermore, sample size was mentioned in 154 studies with a wide range of 22–36,826 participants. The median numbers of participants recruited in the reported studies (157 findings) were 325 (IQR: 560.5), 379 (IQR: 564.0), and 325 (IQR: 560) in flood, tsunami, and cyclone studies, respectively.

Population: Participants’ age group was mentioned in 119 findings. Fifty-two findings included adult participants. Thirty-four findings reported MH events among children and adolescents. Yet again, thirty-nine findings reported findings on children, adolescents, and adults. The mean age of study participants varied widely (12.9–50.5 years in cyclone studies, 14.6–58.6 years in flood studies, and 9.4-70.5 years in tsunami studies).

Instruments: Across the studies, variety of instruments for MH outcomes were administered [Supplementary Table 4 (356.2KB, pdf) ]. Varied versions of Impact of Events Scale (IES) were used in fifty studies (forty-six tsunami, three flood, and one cyclone), General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) was used in thirty-two studies (thirty tsunami and two flood), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) was used in nine studies (six tsunami, two flood, and one cyclone), Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) was used in eight studies (one tsunami, five flood, and two cyclone), and CRIES was used in eight studies (seven tsunami and one flood). Five studies reported to have collected data through online mode[48,69,126,151,159] (web service/telemedicine), whereas 149 studies reported data collection in offline mode (face-to-face interviews). Thirty-eight studies (thirty-seven tsunami studies among Scandinavian tourists and one flood study among Indian residents) collected data by postal communication.

Eighty studies reported that study participants witnessed death of the kins. Five cyclone studies[37,76,130,131,149] reported witnessing death of the kins (range: 0%–32%). Among seven flood studies,[43,64,75,83,106,150,153] one study from Bihar, India,[43] reported that 100% participants saw loss of their kins. About three-fifths of tsunami studies (n = 68) reported study participants experiencing loss of kins (2.7%-100%). Five studies (four among tourists[69,124,140,141] and one among local residents[63]) reported death of kins of 100% study participants, while twenty tsunami studies mentioned more than half of participants witnessed loss of their kins. Only eight tsunami studies (6.6%) reported less than 5% of study participants saw the demise of their kins [Supplementary Table 4 (356.2KB, pdf) ].

Prevalence of MH disorders: The overall burden of MH disorders was mentioned in 27 studies (two cyclone: 9%–80.4%, five floods: 11.5%–45.3%, and twenty tsunami: 6.4%–77.6%), with overall prevalence ranging from 6.4%–80.4%. Burden of MH illness was less than 10% in three studies,[31,134,168] while six studies reported MH burden as 50% or more.[21,76,77,85,100,124] Prevalence of overall MH burden varied from 6.4% to 69% among the tourists (ten studies), whereas it was 6.6%–80.4% among local residents (seventeen studies). Psychological distress was measured by GHQ-12 and was mentioned in seven studies where the mean score ranged between 1.68 and 23.7. IES-R score was reported in twenty-three findings (mean score range: 0.99–39.31), while among tourists, the score was between 0.99 and 33.2.

Outcome measure was anxiety in nearly one-fourth (n = 36) of all selected studies, ranging from 0.4% to 100%. In five studies exposed to cyclone, the prevalence of anxiety ranged from 12% to 99% (all on local residents). Prevalence of anxiety in flood studies ranged from3.7% to 100%. The prevalence of anxiety in tsunami studies was reported as 0.4%–52%. In 57 findings, depression was the outcome variables as prevalence (0.9%–98.1%). In five cyclone studies, prevalence of depression varied from 17.6% to 82%. The prevalence of depression was between 1.6% and 98.1% in eight flood studies. In tsunami studies, prevalence of depression ranged from 0.92% to 77.1%. Stress was documented in eight studies (0.6%–93.8%), wherein five studies[31,50,51,65,134] had stress burden less than 3%. PTSD was reported in eighty-three findings, where the prevalence ranged from 0% to 100%. In six studies of cyclone, PTSD varied from 5.4% to 89%. PTSD was measured in sixty-nine tsunami findings, wherein prevalence ranged from 0% to 78.1%. PTSD was reported in twenty-three studies of tourists, where burden ranged from 0.4% to 78.1%. Intrusion was measured in fifteen studies. The prevalence of intrusion was 23.68%–71.4%. Avoidance was documented in twenty-one studies. The prevalence range of avoidance was 1.5%–62.8%.

Suicidal tendency was reported in fifteen studies, with prevalence varying between 1.1% and 24% (four cyclone, three flood, and eight tsunami studies). The prevalence of suicidal ideation was 1.1%–9.6% (studies within 12 months of event) in comparison to 2%–24% (studies beyond twelve months). Similar trend was seen for all types of extreme weather events among both tourists and locals. Insomnia was documented in eight studies varying between 8.3% and 62.5% (two cyclone, two flood, and four tsunami studies) among the locale only. It heterogeneously varied across studies carried out 2 to 60 months postevent. Burden of social isolation was measured in seven studies (two cyclone, two flood, and three tsunami studies) among the locale from India, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka (prevalence ranged from 0.4% to 75%). Four out of five studies reported prevalence of disaster memories (17.5%–85%) among children and adolescents (5–19 years). Regarding other MH illness, eight studies reported alcohol dependence among 0.7%–12.69% of midage participants (34–50 years). Fear ranged from 10.8% to 92.0%, while fear of recurrence of same event ranged from 11% to 94.3%. In tsunami studies, fear varied from 15.5% to 77.4%, while fear of recurrence of same events was documented as 94.3%. Nightmares ranged from 17.2% to 83.1% (one cyclone[131] and four tsunami studies[35,48,97,148]) [Supplementary Table 5 (267.7KB, pdf) ].

Mental health outcomes were relatively higher in the studies conducted within 1 year of the events [(overall MH (16 studies), anxiety (19 studies), depression (30 studies), and PTSD (46 studies)] compared to studies carried out after 1 year to 12 years of the events [(overall MH: (10 studies), anxiety: (6 studies), depression: (10 studies), and PTSD: (20 studies)].

Risk and protective factors

Systematic review of the studies identified infrastructural damage after cyclones, tsunami, flash floods, river bank erosion, saline water intrusion, displaced habitation, loss of home or job, being disconnected from family, and death of kin as some of the risk factors to the onset of mental health problems among extreme weather event victims. Alongside the risk factors, early warning system, frequent experience to adverse weather events, collective resilience to combat the events, and affectionate society supporting each other in times of distress were some of the protective factors to reorganize after such adverse events.

Meta-analysis

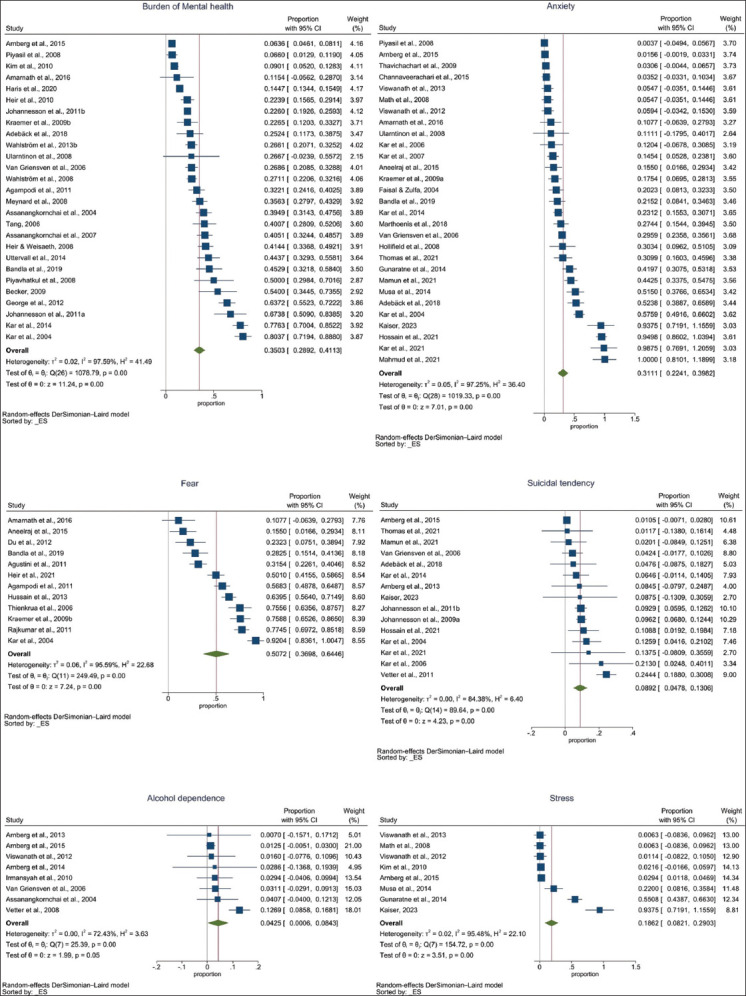

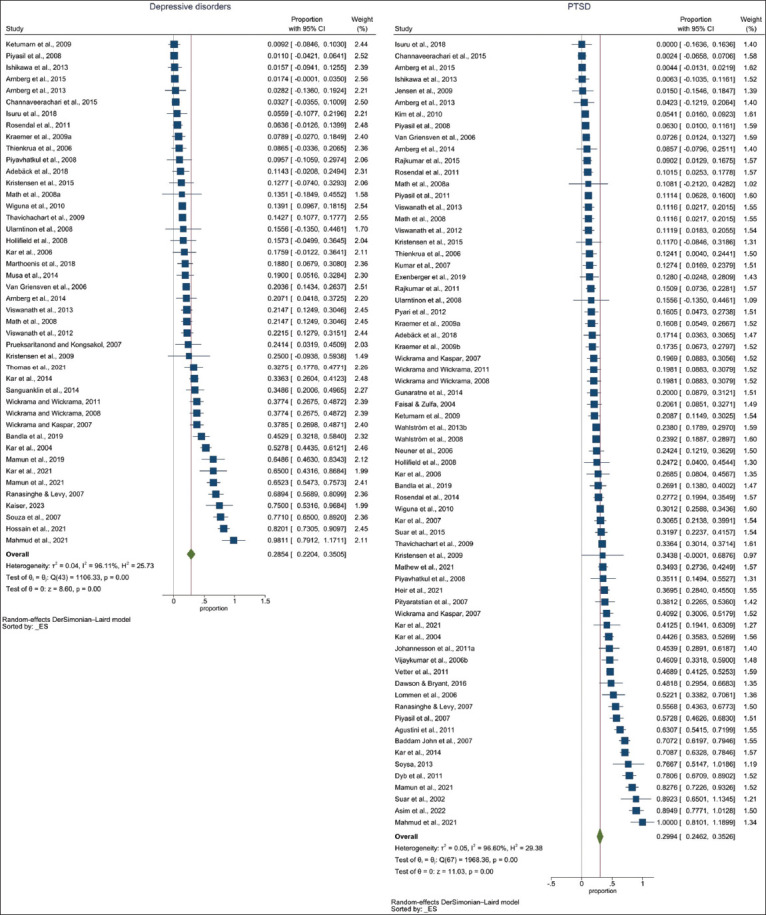

The overall burden of MH disorders was found to be 35.03% (95%CI: 28.92%–41.13%) with high heterogeneity among the reported twenty-seven studies [Supplementary Table 6]. In subgroup analysis, studies on cyclone (44.59%; 95%CI: 25.34%–100%), India (49.7%; 95%CI: 20.83%–78.58%), local residents (38.62%; 95%CI: 27.73%–49.51%), combined children and adolescents (50%; 95%CI: 29.84%–70.16%), rural settings (54%; 95%CI: 34.45%–73.55%), and community settings (39.55%; 95%CI: 29.83%-49.27%) reported higher burden of MH disorders. Studies on all subgroups significantly (P < 0.05) affected burden of MH, except studies on cyclone (P = 0.211). Anxiety was reported in twenty-nine studies (seventeen tsunami studies) depicting high heterogeneity among the studies [Figure 2]. Three studies from Bangladesh had significantly higher prevalence (77.25%; 95%CI: 39.99%–100%) followed by two studies from Sri Lanka (39.33%; 95%CI: 29.47%–49.19%). Depressive disorders (forty-four studies) and PTSD (sixty-eight studies) had similar prevalence (28.54%; 95%CI: 22.04%–35.05% and 29.94%; 95%CI: 24.62%–35.26%, respectively) with high heterogeneity [Figure 3]. Studies from Bangladesh had significantly higher prevalence followed by Sri Lanka.

Supplementary Table 6.

Pooled prevalence and sub-group independent variables (studies with event name, event country, population type, resident type, questionnaire administration mode: online/offline) explaining highest prevalence of outcome

| Outcome | Pooled prevalence % (95% CI) | I2 value (%) | Sub-group analysis (Independent variables & %) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MH burden (27 studies) | 35.03 (28.92-41.13) | 97.59 | Cyclone (44.59%); India (49.7%); Local residents (38.62%); Combined children & adolescents (50%); Rural settings (54%); Community settings (39.55%); Offline (36.21%) | |||

| Anxiety (29 studies) | 31.11 (22.41-39.82) | 97.25 | Cyclone (55.43%); Bangladesh (77.25%); Local residents (29.64%); Adults (35.29%); Rural settings (98.75%) | |||

| Depressive disorders (44 studies) | 28.54 (22.04-35.05) | 96.11 | Flood & riverbank erosion (75%); Bangladesh (72.48%); All age groups (37.07%) | |||

| PTSD (68 studies) | 29.94 (24.62-35.26) | 96.6 | Flood (46.94%); Bangladesh (82.76%); Local residents (31.2%); Children (40.89%); School settings (32.03%) | |||

| Stress (8 studies) | 18.62 (8.21-29.03) | 95.48 | Flood & riverbank erosion (93.75%); Bangladesh (93.75%); Adults (36.54%); Community shelter/camp settings (55.08%) | |||

| Fear (12 studies) | 50.72 (36.98-64.46) | 95.59 | Cyclone (92.04%); SEA (69.31%); Tourists (63.03%); All age groups (61.12%); Community settings (51.98%); Offline (54.12%) | |||

| Fear of recurrence of event (6 studies) | 47.02 (29.37-64.67) | 94.66 | Tsunami (56.35%); Sri Lanka (56.88%); Tourist (50.79%); All age groups (94.32%); School settings (57.67%); Online (50.79%) | |||

| Adjustment disorders (7 studies) | 20.55 (5.18-35.92) | 95.24 | Tsunami (24.02%); India (26.68%); All age groups (37.47%); Hospital settings (37.47%) | |||

| Insomnia (8 studies) | 32.35 (17.67-47.03) | 91.9 | Flood & riverbank erosion (62.5%); Bangladesh (62.50%); All age groups (54.57%); Community setting (32.96%) | |||

| Avoidance (9 studies) | 40.88 (26.86-54.89) | 89.26 | Cyclone (50.1%); Sri Lanka (50.97%); All age groups (62.88%); School settings (43.03%) | |||

| Disaster memories (5 studies) | 52.84 (26.84-78.84) | 95.19 | Cyclone (62.24%), Sri Lanka (85%), Local residents (52.84%); Children (85%), Community settings (55.98%) | |||

| Helplessness (6 studies) | 55.42 (39.06-71.78) | 93.5 | Tsunami (67.77%), SEA (69.31%); Tourists (64.33%); All age groups (77.45%) | |||

| Nightmares (5 studies) | 39.19 (17.19-61.19) | 94.63 | Cyclone (80%); India (80%); Tourists (56.5%); Adults (65.78); Rural settings (80%); Community settings (43.91%). Online (56.5%) | |||

| Suicidal tendency (15 studies) | 8.92 (4.78-13.06) | 84.38 | Cyclone (12.77%); SEA (9.83%); Tourists (9.83%); Adolescents (21.3); Rural settings (13.75%); School settings (21.3%). Online (15.6%) | |||

| Social isolation (7 studies) | 17.0 (2.53-31.48) | 87.75 | Flood &riverbank erosion (75%); Bangladesh (75%) | |||

| Prolonged grief disorders (6 studies) | 17.95 (6.91-28.99) | 66.16 | Tsunami (19.93%), SEA (28.25%); Tourists (28.25%); All age groups (24.89%) | |||

| Somatic disorders (7 studies) | 11.26 (3.11-19.4) | 84.15 | Indonesia (30.5%); School settings (30.5%) |

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing pooled prevalence of burden of mental health, anxiety, fear, suicidal tendency, alcohol dependence and stress among the selected studies

Figure 3.

Forest plot showing pooled prevalence of depressive disorders and PTSD among the selected studies

Pooled prevalence of stress (eight studies)[31,50,51,65,102,128,134,156] and adjustment disorders (seven studies)[21,50,51,59,65,66,89] were similar. Stress had higher prevalence in flood studies in Bangladesh followed by Sri Lanka [Figure 2]. Adjustment disorders were significantly higher in India (26.68%; 95%CI: 7.96%–45.4%), compared to Thailand (9.57%; 95%CI: 0%–29.74%) and Indonesia (1.83%; 95%CI: 0%–6.07%). Pooled prevalence of fear (twelve studies)[20,44,73,76,83,92,111,114,137,138,148,159] [Figure 2], prolonged grief disorders (six studies), disaster memories (five studies),[20,35,130,131,153] helplessness (six studies),[20,73,106,111,114,138] difficulty in concentration (four studies),[106,129,130,148] and recurrence of fear of event (six studies)[20,26,35,48,130,137] were similar with high heterogeneity among the reported studies. Fear had higher prevalence in SEA followed by Thailand, Sri Lanka, and India (95%CI widely varied from 13.45% to 87.42%). Fear of recurrence of events was higher on studies from Sri Lanka with wide variability (56.88%; 95%CI: 22.01%–91.76%). Insomnia (eight studies)[13,35,45,97,128,129,130,148] and flashbacks (four studies)[20,48,106,148] were noted to have identical prevalence, while prevalence of insomnia was higher in studies from Bangladesh followed by Thailand.

Prevalence of avoidance (nine studies)[26,35,97,106,129,130,131,148,157] and nightmares (five studies)[35,48,97,131,148] were analogous and were noted as higher in cyclone studies. Prevalence of alcohol dependence (eight studies) and suicidal tendency (fifteen studies) were less than 10% with presence of heterogeneity among the selected studies [Figure 2]. Social isolation (7 studies)[35,45,50,65,128,130,131] and substance abuse (eight studies)[13,31,45,49,62,83,102,128] depicted similar prevalence (17%; 95%CI: 2.53%–31.48%; 10.57%; 95%CI: 1.72%–19.41%. respectively), with higher prevalence in studies of flood and community settings. In some forest plots of prevalence, the 95% CI that had negative lower bounds could be due to statistical artifacts, especially when the pooled prevalence was very low, or sample sizes were small, or variance was high. In some cases, prevalence estimates were just above one and could be due to sampling errors (all samples are positive/prevalent, small sample size, or due approximations while using the arcsine transformations) [Figures 1 and 2].[170] Meta-regression analysis was performed using the variables year of publication, quality score of studies, sample size, and percentage of sample who lost their kin. However, none of these variables could explain the source of heterogeneity for the pooling of following parameters with nine or more studies with heterogeneity (burden of MH disorders, anxiety, depressive disorders, PTSD, fear, avoidance, and suicidal tendency). Visual asymmetry in funnel plot and intercept with P < 0.05 in Eggers test suggests possibility of publication bias in following parameters with nine or more studies (burden of MH disorders, anxiety, depressive disorders, PTSD, and fear) [Supplementary Figure 1 (908.3KB, tif) ].

DISCUSSION

The results of this review provide an overview of the varied spectrum of MH disorders following impact of extreme weather events in the SEA nations. Our study noticed poorer outcomes for mental health after the occurrence of extreme weather events.[4,171] However, high heterogeneity in assessment tools for MH outcomes in the studies poses challenge in generalizing the results and having standard operating procedures in case of such adversities. Furthermore, planned research after disaster was challenging and had ethical constraints in some studies. In the aftermath of events, extending maximum support and relief to the affected holds top priority. Streamlining research approval through a centralized system and enhancing interagency coordination would avoid duplication of studies.

The December 2004 tsunami and flood events were reported from majority of SEA countries, while cyclone events were reported from India, Bangladesh, and Myanmar. Of the six cyclonic events, three are in the last decade (2017, 2019, and 2020, all in the month of May). The typical manifestation of MH disorders like anxiety, depression, PTSD, stress, insomnia, and residents was more prevalent among residents from SEA countries. In contrast, visiting tourists experienced fear, fear of recurrence of tsunami, nightmares, and sense of helplessness. This could be possibly because tsunami was an unprecedented experience for the Scandinavian tourists. Similar responses were reported in a recent systematic review on extreme weather events on Europeans.[10]

While we focused on the populations like women, elderly, children, people with preexisting mental illnesses, people with low-income, indigenous people, and native communities, they are most susceptible to extreme weather event associated MH disorders.[9,10,171,172] Perhaps, the key factors are their low adaptability and eco-paralysis to tackle the after-effects of impact of extreme weather events. Although people of all groups equally faced the MH challenges, disaster memories seem to be impregnated among the children and could have long-term consequences. The American Psychological Association has expressed children as more susceptible to the impacts of postdisaster MH outcomes when compared to adults.[173] The current study revealed increased psychological morbidities within a year of the disaster.[174,175]

Another intriguing discovery is that despite more than half of the chosen studies documenting the observation of loss of kins, there has been a comparable reaction to various MH disorders. For example, the average rate of PTSD occurrence was around 30% in studies where less than 10% of participants witnessed the death of their relatives, as well as in studies where over 50% of participants witnessed any death of their relatives. The prevalence of suicidal thoughts among this group was also below the average reported. This can be partially attributed to the collectivist societal culture in the SEA countries that fosters an affectionate environment where individuals understand and support each other in times of distress. However, there are contrasting and inconclusive evidence between suicidal ideation and climate change from the western communities.[175,176] Middle-aged individuals were noted to develop alcohol dependence, likely due to the demands and obligations of overseeing the restoration of their livelihoods after such events.

Alike the current study, American Psychological Association also iterated analogous MH outcomes following disaster that manifests as increase in alcohol use, PTSD, anxiety, and depression.[173] In contrast, Deglon et al.[6] found that in African countries, floods, extreme heat, droughts, and bushfires were associated with mood disorders, suicide, trauma, and stressor-related disorders. Furthermore, sleep disturbances, alcohol abuse, anxiety, and stress were prevalent in African nations, although below pathological threshold. All these related studies are not truly comparable between themselves because of variance in study initiation, participants, sampling design, instruments used, severity of disaster etc.[175,177]

Although this systematic approach generated wide range of information on extreme weather events and spectrum of MH disorders in the SEA region, there were many limitations. The exposure of interest in this SRMA was extreme weather events. During the literature review on extreme weather, we found storms, cyclones, floods, and tsunami as the common extreme weather events. Landslides and land-locked earthquakes, although were common events in the SEA, they were beyond the effects of weather induced events and were not included. Expression of MH distress after the devastation caused by tsunami, flood, and cyclone may not be the true meaning of exposure-based trauma and sufficiently explored using this methodological approach. Quantitative evidence for the association between extreme weather events and mental health was limited primarily due to absence of longitudinal data, exposure gradient, and comparison with an unaffected group and objective exposure measures. Although the purpose of this study was to summarize prevalence of MH outcomes, effect of gender, occupation, marginalized populations, and homeless people, people with existing mental illness were not considered. Furthermore, as we focused on peer-reviewed published information on burden of MH outcomes following extreme weather events, the non–peer-reviewed studies, databases, and reports were included in the search strategy. Variability in the tools used to express the common MH disorders may have influenced the results of this study. Another factor was the diverse time frames in which various studies have documented the prevalence of MH parameters following exposure to a traumatic event, thereby exhibiting high degree of heterogeneity. Despite vast number of eligible studies, some MH outcomes were based on only a few studies; such relative findings need to be considered cautiously. Notwithstanding these limitations, the aim of this study was met.

CONCLUSION

Adverse mental health outcomes are observed in the aftermath of extreme weather events. Although MH outcome varied across population in terms of sociodemographic characteristics like age, gender, residence (rural/urban), and collectivistic society in SEA nations is a sense of relief during postevent rehabilitations. Within the SEA countries, anxiety, depression, PTSD, substance abuse, suicide etc., have been documented in different proportions. Hence, it is imperative to develop inclusive and resilient approaches to give priority to mental health concerns among individuals affected by extreme weather events, ensuring effective identification, treatment, and well-informed policies.

Ethical approval statement

Ethical approval is not required; this article is a systematic review of secondary published data.

Financial support and sponsorship

Indian Council of Medical Research [GRANTATHON2/ MH8/2024NCDII].

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Characteristics of the selected studies including instruments used and mode of administration (n=155)

Characteristics of the selected studies according to different MH illnesses (n=155)

Funnel plot and Eggers test suggesting possibility of publication bias in following parameters with nine or more studies (Burden of MH disorders, Anxiety, Depressive disorders, PTSD, and Fear). *Burden of MH disorders, p=0.0048 (publication bias present); Anxiety, p=0.0009 (publication bias present); Depressive disorders, p=0.1512 (although Eggers test is not indicating, but visual observation of funnel plot indicates asymmetry hence, there could be the possibility of publication bias); PTSD, p=0.0664 (although Eggers test is not indicating, but visual observation of funnel plot indicates asymmetry hence, there could be the possibility of publication bias); Fear, p=0.0017 (publication bias present)

PRISMA 2020 ITEM CHECKLIST

| Section and topic | Item # | Checklist item | Location where item is reported Page No. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | ||||||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review. | 1 | |||

| Abstract | ||||||

| Abstract | 2 | See the PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist | 1 | |||

| Introduction | ||||||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge. | 2 | |||

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses. | 2 | |||

| Methods | ||||||

| Eligibility criteria | 5 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review and how studies were grouped for the syntheses. | 2 | |||

| Information sources | 6 | Specify all databases, registers, websites, organisations, reference lists and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted. | 2 | |||

| Search strategy | 7 | Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, including any filters and limits used. | 2-3 (Suppl. file) | |||

| Selection process | 8 | Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of the review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | 2-3 | |||

| Data collection process | 9 | Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | 2-3 | |||

| Data items | 10a | List and define all outcomes for which data were sought. Specify whether all results that were compatible with each outcome domain in each study were sought (e.g. for all measures, time points, analyses), and if not, the methods used to decide which results to collect. | 3 | |||

| 10b | List and define all other variables for which data were sought (e.g. participant and intervention characteristics, funding sources). Describe any assumptions made about any missing or unclear information. | 6-15 (Suppl. file) | ||||

| Study risk of bias assessment | 11 | Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies, including details of the tool(s) used, how many reviewers assessed each study and whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | 3 | |||

| Effect measures | 12 | Specify for each outcome the effect measure(s) (e.g. risk ratio, mean difference) used in the synthesis or presentation of results. | 3 | |||

| Synthesis methods | 13a | Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis (e.g. tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing against the planned groups for each synthesis (item #5)). | 3 | |||

| 13b | Describe any methods required to prepare the data for presentation or synthesis, such as handling of missing summary statistics, or data conversions. | 3 | ||||

| 13c | Describe any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses. | 3 | ||||

| 13d | Describe any methods used to synthesise results and provide a rationale for the choice(s). If meta-analysis was performed, describe the model(s), method(s) to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity, and software package(s) used. | 4 | ||||

| 13e | Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (e.g. subgroup analysis, meta-regression). | 3 | ||||

| 13f | Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess robustness of the synthesised results. | 3 | ||||

| Reporting bias assessment | 14 | Describe any methods used to assess risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases). | 3 | |||

| Certainty assessment | 15 | Describe any methods used to assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome. | 3 | |||

| Results | ||||||

| Study selection | 16a | Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review, ideally using a flow diagram (see Fig. 1). | 1 (Figure file) | |||

| 16b | Cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded. | 1 (Figure file) | ||||

| Study characteristics | 17 | Cite each included study and present its characteristics. | 3-5 | |||

| Risk of bias in studies | 18 | Present assessments of risk of bias for each included study. | 4 & 4 (Suppl. file) | |||

| Results of individual studies | 19 | For all outcomes, present, for each study: (a) summary statistics for each group (where appropriate) and (b) an effect estimate and its precision (e.g. confidence/credible interval), ideally using structured tables or plots. | 3-6 & 5-27 (Suppl. file) | |||

| Results of syntheses | 20a | For each synthesis, briefly summarise the characteristics and risk of bias among contributing studies. | 3-6 & 4 (Suppl. file) | |||

| 20b | Present results of all statistical syntheses conducted. If meta-analysis was done, present for each the summary estimate and its precision (e.g. confidence/credible interval) and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect. | 3-7 & 5-27 (Suppl. file) | ||||

| 20c | Present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results. | 8 | ||||

| 20d | Present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesised results. | 8 | ||||

| Reporting biases | 21 | Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed. | 8 | |||

| Certainty of evidence | 22 | Present assessments of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed. | 8 | |||

| Discussion | ||||||

| Discussion | 23a | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence. | 8-9 | |||

| 23b | Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in the review. | 9-10 | ||||

| 23c | Discuss any limitations of the review processes used. | 9-10 | ||||

| 23d | Discuss implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research. | 10 | ||||

| Other information | ||||||

| Registration and protocol | 24a | Provide registration information for the review, including register name and registration number, or state that the review was not registered. | 1 | |||

| 24b | Indicate where the review protocol can be accessed, or state that a protocol was not prepared. | PROSPERO | ||||

| 24c | Describe and explain any amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol. | No amendments | ||||

| Support | 25 | Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for the review, and the role of the funders or sponsors in the review. | 2 (First page file) | |||

| Competing interests | 26 | Declare any competing interests of review authors. | 2 (First page file) | |||

| Availability of data, code, and other materials | 27 | Report which of the following are publicly available and where they can be found: template data collection forms; data extracted from included studies; data used for all analyses; analytic code; any other materials used in the review. | Supplementary files (Suppl. file) |

PRISMA 2020 ABSTRACT CHECKLIST

| Section and topic | Item # | Checklist item | Location where item is reported Page 3 (Title page file) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | ||||||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review. | Line number 1-2 | |||

| Background | ||||||

| Objectives | 2 | Provide an explicit statement of the main objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses. | Line number 5-6 | |||

| Methods | ||||||

| Eligibility criteria | 3 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review. | Line number 8-10 | |||

| Information sources | 4 | Specify the information sources (e.g. databases, registers) used to identify studies and the date when each was last searched. | Line number 8-9 | |||

| Risk of bias | 5 | Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies. | Line number 10-12 | |||

| Synthesis of results | 6 | Specify the methods used to present and synthesize results. | Line number 11-12 | |||

| Results | ||||||

| Included studies | 7 | Give the total number of included studies and participants and summarize relevant characteristics of studies. | Line number 13-14 | |||

| Synthesis of results | 8 | Present results for main outcomes, preferably indicating the number of included studies and participants for each. If meta-analysis was done, report the summary estimate and confidence/credible interval. If comparing groups, indicate the direction of the effect (i.e. which group is favoured). | Line number 14-20 | |||

| Discussion | ||||||

| Limitations of evidence | 9 | Provide a brief summary of the limitations of the evidence included in the review (e.g. study risk of bias, inconsistency and imprecision). | Line number 19-20 | |||

| Interpretation | 10 | Provide a general interpretation of the results and important implications. | Line number 21-24 | |||

| Other | ||||||

| Funding | 11 | Specify the primary source of funding for the review. | … | |||

| Registration | 12 | Provide the register name and registration number. | Line number 7 |

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the support of the Indian Council of Medical Research for this project [GRANTATHON2/MH-8/2024-NCD-II]. Authors are grateful to Director-in-Charge and Dr. Saibal Das, Scientist D, ICMR- Centre for Ageing and Mental Health, Kolkata and for their scientific support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asian Development Bank (ADB) Six ways South-east Asia strengthened disaster risk management. 2021 Available from: https://www.adb.org/news/features/six-ways-southeast-asia-strengthened-disaster-risk-management . [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Meteorological Organization State of the Climate in Asia 2023 [Internet] Available from: https://wmo.int/publication-series/state-of-climate-asia-2023. [Last accessed on 2024 Jul 25] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Majumder J, Saha I, Saha A, Chakrabarti A. Climate change, disasters, and mental health of adolescents in India. Indian J Psychol Med. 2023;45:289–91. doi: 10.1177/02537176231164649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keya TA, Leela A, Habib N, Rashid M, Bakthavatchalam P. Mental health disorders due to disaster exposure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cureus. 2023;15:e37031. doi: 10.7759/cureus.37031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wahid SS, Raza WA, Mahmud I, Kohrt BA. Climate-related shocks and other stressors associated with depression and anxiety in Bangladesh: A nationally representative panel study. Lancet Planet Heal. 2023;7:e137–46. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00315-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deglon M, Dalvie MA, Abrams A. The impact of extreme weather events on mental health in Africa: A scoping review of the evidence. Sci Total Environ. 2023;10:163420. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.163420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walinski A, Sander J, Gerlinger G, Clemens V, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Heinz A. The effects of climate change on mental health. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2023;120:117–24. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.m2022.0403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patwary MM, Bardhan M, Haque MA, Moniruzzaman S, Gustavsson J, Khan MMH, et al. Impact of extreme weather events on mental health in South and Southeast Asia: A two decades of systematic review of observational studies. Environ Res. 2024;250:118436. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2024.118436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cruz J, White PCL, Bell A, Coventry PA. Effect of extreme weather events on mental health: A narrative synthesis and meta-analysis for the UK. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1–17. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17228581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weilnhammer V, Schmid J, Mittermeier I, Schreiber F, Jiang L, Pastuhovic V, et al. Extreme weather events in europe and their health consequences – A systematic review. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2021;233:113688. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2021.113688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hossain A, Ahmed B, Rahman T, Sammonds P, Zaman S, Benzadid S, et al. Household food insecurity, income loss, and symptoms of psychological distress among adults following the Cyclone Amphan in coastal Bangladesh. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0259098. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0259098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Descilo T, Vedamurtachar A, Gerbarg PL, Nagaraja D, Gangadhar BN, Damodaran B, et al. Effects of a yoga breath intervention alone and in combination with an exposure therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder and depression in survivors of the 2004 South-East Asia tsunami. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121:289–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Griensven F, Chakkraband MLS, Thienkrua W, Pengjuntr W, Cardozo BL, Tantipiwatanaskul P, et al. Mental health problems among adults in tsunami-affected areas in Southern Thailand. JAMA. 2006;296:537–48. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.5.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wind TR, Joshi PC, Kleber RJ, Komproe IH. The impact of recurrent disasters on mental health: A study on seasonal floods in Northern India. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2013;28:279–85. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X13000290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rayyan-AI Powered Tool for Systematic Literature Reviews. Available from: https://www.rayyan.ai/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean R. Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS) BMJ Open. 2016;6:1–7. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freeman MF, Tukey J. Transformations related to the angular and the square root. Ann Math Stat. 1950;21:607–11. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rücker G, Schwarzer G, Schumacher M. Heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Misconceiving I2. Available from: https://abstracts.cochrane.org/2008-freiburg/heterogeneity-meta-analysis-misconceiving-i2 . [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aneelraj D, Kumar CN, Somanathan R, Chandran D, Joshi S, Paramita P, et al. Uttarakhand disaster 2013: A report on psychosocial adversities experienced by children and adolescents. Indian J Pediatr. 2016;83:316–21. doi: 10.1007/s12098-015-1921-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piyavhatkul N, Pairojkul S, Suphakunpinyo C. Psychiatric disorders in tsunami-affected children in Ranong province, Thailand. Med Princ Pract. 2008;17:290–5. doi: 10.1159/000129608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ponnamperuma T, Nicolson NA. The relative impact of traumatic experiences and daily stressors on mental health outcomes in Sri Lankan adolescents. J Trauma Stress. 2018;31:487–98. doi: 10.1002/jts.22311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prueksaritanond S, Kongsakol R. Biopsychosocial impacts on the elderly from a tsunami-affected community in southern Thailand. J Med Assoc Thail. 2007;90:1501–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pyari TT, Kutty RV, Sarma PS. Risk factors of post-traumatic stress disorder in tsunami survivors of Kanyakumari District, Tamil Nadu, India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2012;54:48–53. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.94645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rajkumar AP, Mohan TSP, Tharyan P. Lessons from the 2004 Asian tsunami: Nature, prevalence and determinants of prolonged grief disorder among tsunami survivors in South Indian coastal villages. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2015;61:645–52. doi: 10.1177/0020764015570713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ranasinghe PD, Levy BR. Prevalence of and sex disparities in posttraumatic stress disorder in an internally displaced Sri Lankan population 6 months after the 2004 Tsunami. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2007;1:34–41. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e318068fbb7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosendal S, Mortensen EL, Andersen HS, Heir T. Use of health care services before and after a natural disaster among survivors with and without PTSD. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65:91–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosendal S, Şalcioǧlu E, Andersen HS, Mortensen EL. Exposure characteristics and peri-trauma emotional reactions during the 2004 tsunami in Southeast Asia-what predicts posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms? Compr Psychiatry. 2011;52:630–7. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanguanklin N, Mcfarlin BL, Park CG, Giurgescu C, Finnegan L, White-Traut R, et al. Effects of the 2011 Flood in Thailand on birth outcomes and perceived social support. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2014;43:435–44. doi: 10.1111/1552-6909.12466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sattler DN, Assanangkornchai S, Moller AM, Kesavatana-Dohrs W, Graham JM. Indian ocean Tsunami: Relationships among posttraumatic stress, posttraumatic growth, resource loss, and coping at 3 and 15 months. J Trauma Dissociation. 2014;15:219–39. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2014.869144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arnberg FK, Gudmundsdóttir R, Butwicka A, Fang F, Lichtenstein P, Hultman CM, et al. Psychiatric disorders and suicide attempts in Swedish survivors of the 2004 southeast Asia tsunami: A 5 year matched cohort study. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:817–24. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00124-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh G, Kishore Verma K. Psychosocial impact in flood disaster affected area: Experience in Jammu & Kashmir. Int J Acad Med Pharm. 2023;5:229–33. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siqveland J, Nygaard E, Hussain A, Tedeschi RG, Heir T. Posttraumatic growth, depression and posttraumatic stress in relation to quality of life in tsunami survivors: A longitudinal study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:18. doi: 10.1186/s12955-014-0202-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Souza R, Bernatsky S, Reyes R, De Jong K. Mental health status of vulnerable tsunami-affected communities: A survey in Aceh Province, Indonesia. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20:263–9. doi: 10.1002/jts.20207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soysa CK. War and tsunami PTSD responses in Sri Lankan children: Primacy of reexperiencing and arousal compared to avoidance-numbing. J Aggress Maltreatment Trauma. 2013;22:896–915. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suar D, Das SS, Alat P. Bereavement, postdisaster trauma, and behavioral changes in tsunami survivors. Death Stud. 2015;39:226–33. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2014.979957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suar D, Mandal MK, Khuntia R. Supercyclone in Orissa: An assessment of psychological status of survivors. J Trauma Stress. 2002;15:313–9. doi: 10.1023/A:1016203912477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sveen J, Johannesson KB, Cernvall M, Arnberg FK. Trajectories of prolonged grief one to six years after a natural disaster. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0209757. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang CS kum. Positive and negative postdisaster psychological adjustment among adult survivors of the Southeast Asian earthquake-tsunami. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61:699–705. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Telles S, Naveen K V, Dash M. Yoga reduces symptoms of distress in tsunami survivors in the Andaman Islands. Evidence-based Complement Altern Med. 2007;4:503–9. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Telles S, Singh N, Joshi M. Risk of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in survivors of the floods in Bihar, India. Indian J Med Sci. 2009;63:330–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arnberg FK, Hultman CM, Michel PO, Lundin T. Social support moderates posttraumatic stress and general distress after disaster. J Trauma Stress. 2012;25:721–7. doi: 10.1002/jts.21758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Telles S, Singh N, Joshi M, Balkrishna A. Post traumatic stress symptoms and heart rate variability in Bihar flood survivors following yoga: A randomized controlled study. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thienkrua W, Cardozo BL, Chakkraband MLS, Guadamuz TE, Pengjuntr W, Tantipiwatanaskul P, et al. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression among children in tsunami-affected areas in Southern Thailand. JAMA. 2006;296:549–59. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.5.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomas JJ, B P, Kulkarni P, Murthy M R N. Exploring the psychiatric symptoms among people residing at flood affected areas of Kodagu district, Karnataka. Clin Epidemiol Glob Heal. 2021;9:245–50. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ularntinon S, Piyasil V, Ketumarn P, Sitdhiraksa N, Pityaratstian N, Lerthattasilp T, et al. Assessment of psychopathological consequences in children at 3 years after tsunami disaster. J Med Assoc Thai. 2008;91(Suppl 3):S69–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uttervall M, Hultman CM, Ekerwald H, Lindam A, Lundin T. After the flood: Resilience among tsunami-afflicted adolescents. Nord J Psychiatry. 2014;68:38–43. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2013.767373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vetter S, Rossegger A, Elbert T, Gerth J, Urbaniok F, Laubacher A, et al. Internet-based self-assessment after the tsunami: Lessons learned. BMC Public Health. 2011:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vetter S, Rossegger A, Rossler W, Bisson JI, Endrass J. Exposure to the tsunami disaster, PTSD symptoms and increased substance use-An Internet based survey of male and female residents of Switzerland. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Viswanath B, Maroky AS, Math SB, John JP, Cherian A V, Girimaji SC, et al. Gender differences in the psychological impact of tsunami. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2013;59:130–6. doi: 10.1177/0020764011423469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Viswanath B, Maroky AS, Math SB, John JP, Benegal V, Hamza A, et al. Psychological impact of the tsunami on elderly survivors. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20:402–7. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318246b7e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wahlström L, Michélsen H, Schulman A, Backheden M. Support, opinion of support and psychological health among survivors of a natural disaster. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2013;59:40–7. doi: 10.1177/0020764011423174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arnberg FK, Michel PO, Johannesson KB. Properties of Swedish posttraumatic stress measures after a disaster. J Anxiety Disord. 2014;28:402–9. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wahlström L, Michélsen H, Schulman A, Backheden M, Keskinen-Rosenqvist R. Longitudinal course of physical and psychological symptoms after a natural disaster. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2013:4. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.21892. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.21892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wahlström L, Michélsen H, Schulman A, Backheden M. Different types of exposure to the 2004 tsunami are associated with different levels of psychological distress and posttraumatic stress. J Traumatic Stress. 2008;21:463–70. doi: 10.1002/jts.20360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wahlström L, Michélsen H, Schulman A, Backheden M. Childhood life events and psychological symptoms in adult survivors of the 2004 tsunami. Nord J Psychiatry. 2010;64:245–52. doi: 10.3109/08039480903484092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wickrama KAS, Wickrama KAT. Family context of mental health risk in Tsunami affected mothers: Findings from a pilot study in Sri Lanka. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:994–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wickrama KAS, Wickrama T. Perceived community participation in tsunami recovery efforts and the mental health of tsunami-affected mothers: Findings from a study in rural Sri Lanka. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2011;57:518–27. doi: 10.1177/0020764010374426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wiguna T, Guerrero APS, Kaligis F, Khamelia M. Psychiatric morbidity among children in North Aceh district (Indonesia) exposed to the 26 December 2004 tsunami. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry. 2010;2:151–5. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wind TR, Joshi PC, Kleber RJ, Komproe IH. The effect of the postdisaster context on the assessment of individual mental health scores. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2014;84:134–41. doi: 10.1037/h0099385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yoda T, Yokoyama K, Suzuki H, Hirao T. Relationship between long-term flooding and serious mental illness after the 2011 flood in Thailand. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2017;11:300–4. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2016.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thavichachart N, Tangwongchai S, Worakul P, Kanchanatawan B, Suppapitiporn S, Pattalung AS, et al. 2009. Posttraumatic stress disorder of the tsunami survivors in Thailand. J Med Assoc Thail. 2009;92:420–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vijayakumar L, Kumar MS. Trained volunteer-delivered mental health support to those bereaved by Asian tsunami-An evaluation. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2008;54:293–302. doi: 10.1177/0020764008090283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Asim M, Sathian B, Van Teijlingen E, Mekkodathil AA, Babu MGR, Rajesh E, et al. A survey of post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression among flood affected populations in Kerala, India. Nepal J Epidemiol. 2022;12:1203–14. doi: 10.3126/nje.v12i2.46334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Math SB, John JP, Girimaji SC, Benegal V, Sunny B, Krishnakanth K, et al. comparative study of psychiatric morbidity among the displaced and non-displaced populations in the Andaman and Nicobar islands following the tsunami. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2008;23:29–34. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00005513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Math SB, Tandon S, Girimaji SC, Benegal V, Kumar U, Hamza A, et al. Psychological impact of the tsunami on children and adolescents from the Andaman and Nicobar islands. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10:31–7. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v10n0106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vijayakumar L, Kannan GK, Daniel SJ. Mental health status in children exposed to tsunami. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2006;18:507–13. doi: 10.1080/09540260601037581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Math SB, Girimaji SC, Benegal V, Uday Kumar GS, Hamza A, Nagaraja D. Tsunami: Psychosocial aspects of Andaman and Nicobar islands. Assessments and intervention in the early phase. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2006;18:233–9. doi: 10.1080/09540260600656001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kristensen P, Lars W, Heir T. Predictors of complicated grief after a natural disaster: A population study two years after the 2004 South-East Asian tsunami. Death Stud. 2010;34:137–50. doi: 10.1080/07481180903492455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kumar MS, Murhekar MV, Hutin Y, Subramanian T, Ramachandran V, Gupte M. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in a coastal fishing village in Tamil Nadu, India, after the December 2004 tsunami. Am J Public Health. 2020;97:99–101. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.071167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arnberg FK, Bergh Johannesson K, Michel PO. Prevalence and duration of PTSD in survivors 6 years after a natural disaster. J Anxiety Disord. 2013;27:347–52. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wickrama KAS, Kaspar V. Family context of mental health risk in Tsunami-exposed adolescents: Findings from a pilot study in Sri Lanka. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:713–23. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rajkumar AP, Mohan TSP, Tharyan P. Lessons from the 2004 Asian tsunami: Epidemiological and nosological debates in the diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder in non-Western post-disaster communities. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2011;59:123–9. doi: 10.1177/0020764011423468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Meynard JB, Nau A, Halbert E, Todesco A. Health indicators in children from Meulaboh, Indonesia, following the Tsunami of December 26, 2004. Mil Med. 2008;173:900–5. doi: 10.7205/milmed.173.9.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Assanangkornchai S, Tangboonngam Sa-nguansri, Edwards SG. The flooding of Hat Yai: Predictors of adverse emotional responses to a natural disaster. Stress Heal. 2004;20:81–9. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kar N, Jagadisha, Sharma PSVN, Murali N, Mehrotra S. Mental health consequences of the trauma of super-cyclone 1999 in Orissa. Indian J Psychiatry. 2004;46:228–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kar N, Krishnaraaj R, Rameshraj K. Long-term mental health outcomes following the 2004 Asian tsunami disaster. Disaster Heal. 2014;2:35–45. doi: 10.4161/dish.24705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Johannesson KB, Michel PO, Hultman CM, Lindam A, Arnberg F, Lundin T. Impact of exposure to trauma on posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology in swedish tourist tsunami survivors. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197:316–23. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181a206f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Johannesson KB, Lundin T, Fröjd T, Hultman CM, Michel PO. Tsunami-exposed tourist survivors: Signs of recovery in a 3-year perspective. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2011;199:162–9. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31820c73d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nomura A, Honda S, Hayakawa H, Amarasinghe S, Aoyagi K. Post-traumatic stress disorder among senior victims of tsunami-affected areas in southern Sri Lanka. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 81.Assanangkornchai S, Tangboonngam SN, Sam-Angsri N, Edwards JG. A Thai community’s anniversary reaction to a major catastrophe. Stress Heal. 2007;23:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Baddam John P, Russell S, Russell PSS. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder among children and adolescents affected by tsunami disaster in Tamil Nadu. Disaster Manag Response. 2007;5:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.dmr.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bandla S, Nappinnai NR, Gopalasamy S. Psychiatric morbidity in December 2015 flood-affected population in Tamil Nadu, India. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2019;65:338–44. doi: 10.1177/0020764019846166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Banford AJ, Ivey DC, Wickrama T, Fischer J, Prouty A, Smith D. The role of natural disaster in individual and relational adjustment in Sri Lankan mothers following the 2004 tsunami. Disasters. 2016;40:134–57. doi: 10.1111/disa.12137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Becker SM. Psychosocial care for women survivors of the tsunami disaster in India. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:654–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.146571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Berger R, Gelkopf M. School-based intervention for the treatment of tsunami-related distress in children: A quasi-randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78:364–71. doi: 10.1159/000235976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bondjers K, Willebrand M, Arnberg FK. Similarity in symptom patterns of posttraumatic stress among disaster-survivors: A three-step latent profile analysis. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2018;9:1546083. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2018.1546083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chaiphibalsarisdi P. Psychological wellbeing of survivors of the tsunami: Empowerment and quality of life. J Med Assoc Thai. 2008;91:1478–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Channaveerachari NK, Raj A, Joshi S, Paramita P, Somanathan R, Chandran D, et al. Psychiatric and medical disorders in the after math of the uttarakhand disaster: Assessment, approach, and future challenges. Indian J Psychol Med. 2015;37:138–43. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.155610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dar KA, Iqbal N, Prakash A, Paul MA. PTSD and depression in adult survivors of flood fury in Kashmir: The payoffs of social support. Psychiatry Res. 2018;261:449–55. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dawson KS, Bryant RA. Children’s vantage point of recalling traumatic events. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0162030. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Du YB, Lee CT, Christina D, Belfer ML, Betancourt TS, O’Rourke EJ, et al. The living environment and children’s fears following the Indonesian tsunami. Disasters. 2012;36:495–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2011.01271.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dyb G, Jensen TK, Nygaard E. Children’s and parents’ posttraumatic stress reactions after the 2004 tsunami. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;16:621–34. doi: 10.1177/1359104510391048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dyster-Aas J, Arnberg FK, Lindam A, Johannesson KB, Lundin T, Michel PO. Impact of physical injury on mental health after the 2004 Southeast Asia tsunami. Nord J Psychiatry. 2012;66:203–8. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2011.621975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Exenberger S, Ramalingam P, Höfer S. Exploring posttraumatic growth in Tamil children affected by the Indian Ocean Tsunami in 2004. Int J Psychol. 2016;53:397–401. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Exenberger S, Riedl D, Rangaramanujam K, Amirtharaj V, Juen F. A cross-sectional study of mother-child agreement on PTSD symptoms in a south Indian post-tsunami sample. BMC Psychiatry. 2019:19. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2408-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Irwanto, Faisal, Zulfa H. Posttraumatic stress disorder among Indonesian children 5 years after the tsunami. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2015;46:918–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Frankenberg E, Friedman J, Gillespie T, Ingwersen N, Pynoos R, Rifai IU, et al. Mental health in Sumatra after the tsunami. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1671–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.120915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Frankenberg E, Nobles J, Sumantri C. Community destruction and traumatic stress in post-tsunami Indonesia. J Health Soc Behav. 2012;53:498–514. doi: 10.1177/0022146512456207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.George C, Kanakamma LG, John J, Sunny G, Cohen A, De Silva MJ. Post-tsunami mental health: A cross-sectional survey of the predictors of common mental disorders in South India 9-11 months after the 2004 Tsunami. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry. 2012;4:104–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-5872.2012.00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gudmundsdottir R, Hultman CM, Valdimarsdottir U. Evacuation of Swedish survivors after the 2004 Southeast Asian tsunami: The survivors’ perspective and symptoms of post-traumatic stress. Scand J Public Health. 2019;47:260–8. doi: 10.1177/1403494818771418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gunaratne CD, Kremer PJ, Clarke V, Lewis AJ. Trauma-related symptoms in Sri Lankan adult survivors after the tsunami: Pretraumatic and peritraumatic factors. Asia-Pacific J Public Heal. 2014;26:425–34. doi: 10.1177/1010539513500337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]