Abstract

Spinal cord injury (SCI) causes sensory dysfunctions such as paresthesia, dysesthesia, and chronic neuropathic pain. MiR-20a facilitates the axonal outgrowth of the cortical neurons. However, the role of miR-20a in the axonal outgrowth of primary sensory neurons and spinal cord dorsal column lesion (SDCL) is yet unknown. Therefore, the role of miR-20a post-SDCL was investigated in rat. The NF-200 immunofluorescence staining was applied to observe whether axonal outgrowth of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons could be altered by miR-20a or PDZ-RhoGEF modulation in vitro. The expression of miR-20a was quantized with RT-PCR. Western blotting analyzed the expression of PDZ-RhoGEF/RhoA/GAP43 axis after miR-20a or PDZ-RhoGEF was modulated. The spinal cord sensory conduction function was assessed by somatosensory-evoked potentials and tape removal test. The results demonstrated that the expression of miR-20a decreased in a time-dependent manner post-SDCL. The regulation of miR-20a modulated the axonal growth and the expression of PDZ-RhoGEF/RhoA/GAP43 axis in vitro. The in vivo regulation of miR-20a altered the expression of miR-20a-PDZ-RhoGEF/RhoA/GAP43 axis and promoted the recovery of ascending sensory function post-SDCL. The results indicated that miR-20a/PDZ-RhoGEF/RhoA/GAP43 axis is associated with the pathophysiological process of SDCL. Thus, targeting the miR-20a/PDZ-RhoGEF /RhoA/GAP43 axis served as a novel strategy in promoting the sensory function recovery post-SCI.

Keywords: MicroRNA-20a, Dorsal column lesion, PDZ-RhoGEF, RhoA, Neurite growth, Dorsal root ganglion, Primary sensory neuron

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a catastrophic traumatic event that results in the loss of sensory and motor function below the plane of injury, which greatly affects the patients’ quality of life, leading to an enormous financial, social, and emotional burden (Ropper and Ropper 2017). Sensory disruptions, such as paresthesia, including chronic pain (Richards et al. 1980) and dysesthesias (Hoschouer et al. 2010), caused by spinal cord injury (Wang et al. 2014), affect the cortical arousal and subsequently lead to cognitive dysfunction (Richards et al. 1982) and mental illness (Krishnan et al. 1992). The complete damage of spinal cord dorsal column ascending conductive pathway destroys or severely affects the sensory function to discriminate tactile textures, touch frequencies, and directions of moving tactile stimuli (Kaas et al. 2008) due to the separation of the axons and the primary sensory neuron soma. The demyelinated axons of dorsal column contribute to the symptoms including loss of peripheral reflexes, impairment of vibration, position sense, and progressive ataxia. Laboratory investigations have demonstrated that restoring the ascending spinal sensory conductive pathway in injured dorsal column promotes the recovery of sensory function (Goganau et al. 2017; Neumann and Woolf 1999). However, due to the ambiguity of the internal mechanism, the development of effective clinical treatment strategies is hindered. Therefore, elucidating the intrinsic mechanism underlying the primary sensory neuron axonal regeneration is of great significance for finding therapeutic targets and strategies post-dorsal column injury.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a kind of small noncoding RNAs of 20–24 nucleotides that regulate the expression of various genes by repressing translation or degenerating mRNA via binding to the 3-untranslated regions (3′UTRs) of target mRNAs(Bhalala et al. 2012). MiRNAs could modulate the neuron functions and states via posttranscriptional regulation target genes expression and act an necessary role in the pathophysiological process of SCI (Wang et al. 2015a). MiR-20a, together with miR-128, can promote the axon outgrowth of the cortical neurons by regulating the PSD-95/Dlg/ZO-1 homology-Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor (PDZ-RhoGEF)/Ras homolog gene family member A (RhoA)/growth associated protein-43 (GAP43) axis (Sun et al. 2013). PDZ-RhoGEF, a member of RhoGEF subfamily, is a specific activator of RhoA without activating the other members of the Rho-GTPase family (Sun et al. 2013). PDZ-RhoGEF also acts a role in neurite guidance, growth cone collapse, and neurite retraction (Lin et al. 2011). RhoA, a member of the Rho family GTPases, regulates various processes of neural stem cell differentiation to neuron, including neurite growth and arborization, by triggering multiple effector pathways that regulate the actin and microtubule dynamics (Lin et al. 2011). PDZ-RhoGEF exerts a role in shifting the inactive Rho guanosine diphosphate (GDP) to active Rho guanosine triphosphate (GTP) state in response to extracellular signals (Shang et al. 2013), as the downstream molecules of PDZ-RhoGEF, RhoA and GAP43, are major neuronal axon regulator proteins with respect to the growth of neuronal axons post-SCI(Zhang et al. 2016). Different from the peripheral branches that could regenerate after injury, injured central axons of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons in spinal cord do not regenerate, because the intrinsic abilities of expressing growth associated proteins and activating growth cone are decreased in mature neurons, and the microenvironment is inhibitory to axon regeneration(Ko et al. 2016).

Due to similarities in the structure and function between primary sensory neurons and cortical neurons, the present study aimed to investigate whether regulation of miR-20a/PDZ-RhoGEF/RhoA/GAP43 axis could promote the axonal outgrowth of primary sensory neurons and further improve the ascending spinal sensory conductive pathway recovery (Fig. 1a). To date, this was the first research that confirms miR-20a is fully expressed in DRG neurons and performed crucial functions. The miR-20a/PDZ-RhoGEF/RhoA/GAP43 axis that promotes axonal outgrowth in motor neurons and corticospinal tract can exert a similar role in the primary sensory neurons and spinal cord ascending sensory pathways.

Fig. 1.

a Hypothetical mechanism of miR-20a/PDZ-RhoGEF/RhoA/GAP43 axis in DRG neuronal axon regeneration post-spinal cord dorsal column injury. Red lines mean inhibition, while blue arrows mean promotion. b Relative expression trend of miR-20a and miR-128 in DRG tissues post-dorsal column injury as assessed by RT-PCR from day 1 to 28. c The predicted binding site of miR-20a and PDZ-RhoGEF mRNA 3′ UTR. Data are expressed as mean ± SD of triplicate experiments (n = 4, *P < 0.05)

Results

Dorsal Column Injury Decreases miR-20a Expression

Since miR-20a and miR-128 participate in the process of axonal outgrowth of cortical neurons, the level of miR-20a and miR-128 was examined by RT-PCR to investigate whether miR-20a and miR-128 were involved in the pathophysiological process of ascending spinal sensory pathway injury following dorsal column lesion. MiR-20a and miR-128 were detected at 1 day, 3 days, 7 days, 14 days, 21 days, and 28 days post-dorsal column injury. The expression of miR-20a was found to be decreased sharply at 1 day checkpoint, and this trend was sustained until 28 days. The expression of miR-128 in all checkpoints had no statistical difference with that in control group (Fig. 1b). The binding sites of miR-20a and the 3′UTR of rat PDZ-RhoGEF mRNA were showed (Fig. 1c). These results indicated that miR-20a was expressed in DRG and miR-20a expression trend was decreased in a time-dependent manner post-dorsal column injury.

MiR-20a Induces Primary Sensory Neuron Neurite Growth via PDZ-RhoGEF /RhoA/GAP43 Axis

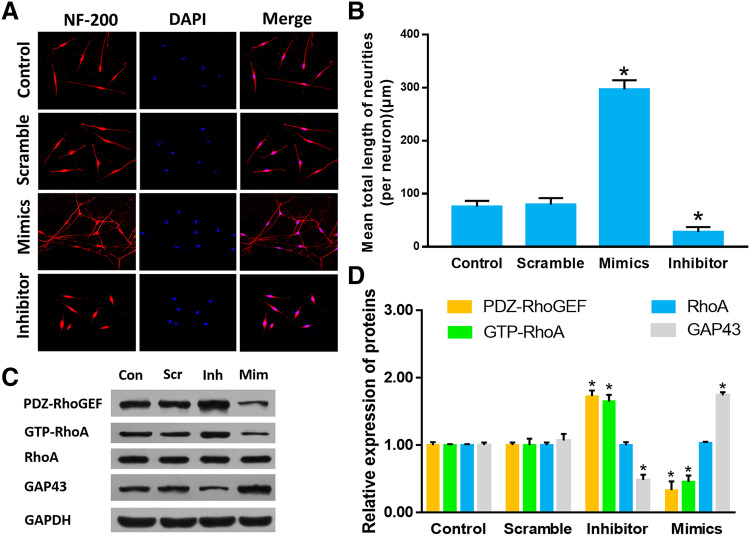

To clarify whether miR-20a induces axon outhgrowth of DRG neurons, we regulated the expression of miR-20a in vitro. The DRG neurons in the mimics group showed significantly longer neurites as compared to that in the control group (P < 0.05). In the inhibitor group, the neurite was shorter as compared to that in the control group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2a, b) (control group: 75.67 ± 10.78 µm; scramble group: 79.33 ± 12.66 µm; inhibitor group: 27.67 ± 9.50 µm; mimics group: 296.67 ± 17.24 µm, P < 0.05). In order to verify whether miR-20a promotes axonal growth through the PDZ-RhoGEF/RhoA/GAP43 axis, we detected the expression of PDZ-RhoGEF, GAP43, and GTP-RhoA in cultured DRG neurons. GAP43 was found to be increased, while that of GTP-RhoA and PDZ-RhoGEF decreased sharply in the mimics group as compared to the that in the control group (P < 0.05). On the contrary, the level of GAP43 decreased and that of GTP-RhoA and PDZ-RhoGEF increased in the inhibitor group as compared to that in the control group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2c, d). The results indicated that miR-20a could regulate the DRG neurons axonal growth via the PDZ-RhoGEF/RhoA/GAP43 axis in vitro.

Fig. 2.

a Immunocytofluorescent images of cultured DRG neurons. NF-200 staining were shown in red, and DAPI staining of cell nuclei was shown in blue (× 200). b Quantitative histogram of neurite length. c Relative protein expression of PDZ-RhoGEF, GTP-RhoA, RhoA and GAP43 detected by Western blot normalized to GAPDH. d Quantitative histogram of Western blot. Data were expressed as mean ± SD of triplicate experiments (n = 4, *P < 0.05). (Con: control group; Scr: scramble group; Inh: inhibitor group; Mim: mimics group)

PDZ-RhoGEF Plays a Key Role in the miR-20a/PDZ-RhoGEF/RhoA/GAP43 Axis

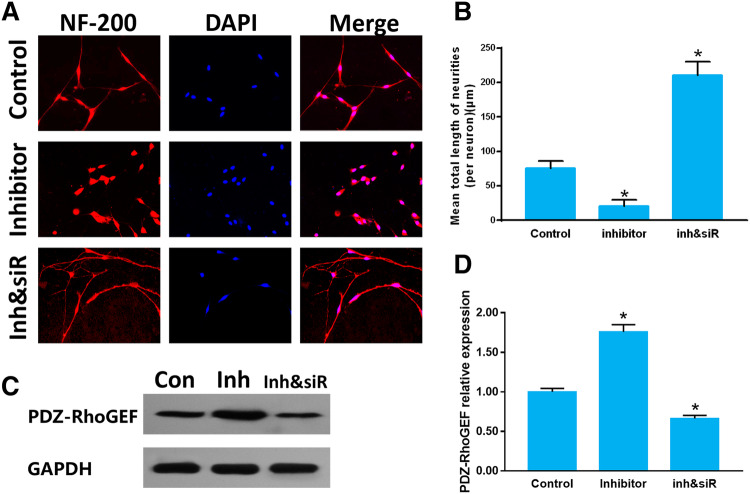

As we all know, one microRNA could regulate multiple target genes, and the above results merely proved that miR-20a targets PDZ-RhoGEF. However, whether miR-20a regulated neuron axon growth via other potential genes should be clarified. Then, we applied miR-20a inhibitor and PDZ-RhoGEF siRNA to combined treat DRG neurons. PDZ-RhoGEF siRNA significantly increased neurite length in miR-20a inhibitor transfected DRG neurons. (Fig. 3a, b) (control: 76.51 ± 11.22; miR-20a inhibitor: 21.36 ± 8.92; miR-20a inhibitor & siRNA: 211 ± 19.52). The PDZ-RhoGEF expression was increased in miR-20a inhibitor group compared with that in control group. The PDZ-RhoGEF expression in miR-20a inhibitor & PDZ-RhoGEF siRNA group was downregulated compared with that in control group (Fig. 3c, d). These results demonstrated that PDZ-RhoGEF was a necessary protein of the miR-20a /PDZ-RhoGEF/RhoA/GAP43 axis, and miR-20a will not modulate the primary sensory neuron neurite growth through other target genes.

Fig. 3.

a Immunofluorescent images of cultured DRG neurons. NF-200 staining was shown in red, and DAPI staining of cell nuclei was shown in blue (× 200). b Quantitative histogram of neurite length. c Relative protein expression of PDZ-RhoGEF by Western blot normalized to GAPDH. d Quantitative histogram of Western blot. Data were expressed as mean ± SD of triplicate experiments (n = 4, *P < 0.05). (Con: control group; Inh: miR-20a inhibitor; Inh&siR: miR-20a inhibitor& PDZ-RhoGEF siRNA)

MiR-20a Antagonizes the Inhibition Effect of Nogo-A-FC on DRG Neurons Axon Outgrowth

The extracellular Nogo66 loop of Nogo-A is the functional structure that interacts with NogoR1 of neurons. The binding of Nogo-A and NogoR1 could activate RhoA to GTP-RhoA and subsequently results in growth cone collapse and neurite retraction (Niederost et al. 2002). As PDZ-RhoGEF could activate RhoA to GTP-RhoA in responds to extracellular signals (Shang et al. 2013), the downregulated PDZ-RhoGEF that operated by miR-20a was supposed to decrease GTP-RhoA to facilitate DRG neuron neurite growth in inhibitory Nogo-A-Fc condition. Therefore, Nogo-A-Fc was applied to cultured DRG neurons with or without miR-20a mimics. An evident reduction in neurite length was observed in Nogo-A-Fc group compared with that in control group. However, miR-20a mimics antagonized the neurite inhibitory effect of Nogo-A-Fc (control: 83.12 ± 5.31 µm; Nogo-A-Fc: 20.67 ± 9.02 µm; Nogo-A-Fc & miR-20a mimics: 75.67 ± 10.79 µm) (Fig. 4a, b). The expressions of GTP-RhoA that regulated by Nogo-A-Fc and miR-20a were evaluated by Western Blot. The GTP-RhoA expression was increased after Nogo-A-Fc treatment compared with that in control group. The GTP-RhoA expression in miR-20a mimics & Nogo-A-Fc group was downregulated compared with that in Nogo-A-Fc group and was similar to that in control group (Fig. 4c, d). These results indicated that miR-20a could promote DRG neuron neurite growth in Nogo-A-Fc inhibition condition via inhibiting RhoA activation.

Fig. 4.

a Immunofluorescent images of cultured DRG neurons. NF-200 staining was shown in red, and DAPI staining of cell nuclei was shown in blue (× 200). b Quantitative histogram of neurite length. c Relative expression of GTP-RhoA and RhoA by Western blot normalized to GAPDH. d Quantitative histogram of Western blot. Data were showed as mean ± SD of three experiments (n = 4, *P < 0.05). (mimics&Nogo: miR-20a mimics & Nogo-A-Fc)

MiR-20a Regulates PDZ-RhoGEF/RhoA/GAP43 Axis in the Dorsal Column Injury Rats

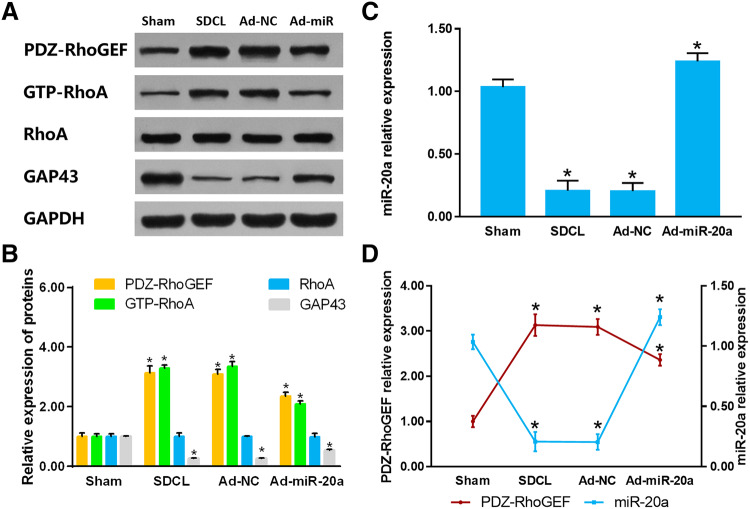

To confirm the regulatory effect of miR-20a on PDZ-RhoGEF/RhoA/GAP43 axis in vivo, we upregulated the miR-20a expression by adenovirus (Ad) DRG injection. Two weeks after adenovirus administration, we detected the miR-20a, PDZ-RhoGEF, GTP-RhoA, and GAP43 expression. The PDZ-RhoGEF protein expression decreased in Ad-miR-20a group as compared to that in the SDCL group (P < 0.05). The expression trend of GTP-RhoA was in agreement with that of PDZ-RhoGEF, while the GAP43 expression trend was converse to that of PDZ-RhoGEF (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5a, b). The miR-20a expressed at a relatively low level in SDCL group and upregulated significantly in the Ad-miR-20a group. The expression trends of PDZ-RhoGEF and miR-20a were reversed among sham, SDCL, Ad-NC, and Ad-miR-20a groups (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5c, d). The expression trend of PDZ-RhoGEF/RhoA/GAP43 axis in vivo was consistent with that in vitro.

Fig. 5.

a Relative protein expression levels of PDZ-RhoGEF, GTP-RhoA, RhoA and GAP43 in DRG tissues post-dorsal column injury assessed by Western blot. b Quantitative histogram of PDZ-RhoGEF, GTP-RhoA, RhoA and GAP43 assessed by Western blot. c Quantitative histogram of miR-20a expression assessed by RT-PCR. d Relative expression trend of miR-20a and PDZ-RhoGEF in DRG tissues post-dorsal column injury. Data were showed as mean ± SD of three experiments (n = 4, *P < 0.05). (SDCL: spinal cord dorsal column lesion; Ad-NC: adenovirus-negative control; Ad-miR: adenovirus-microRNA-20a)

MiR-20a Upregulation Promotes Sensory Conduction Function Recovery

To clarify whether regulation of miR-20a could induce neurite regeneration and sensory conduction function recovery in vivo, NF-200 immunohistochemistry, somatosensory-evoked potentials (SSEP), and tape removal test were conducted (Fig. 6a). Compared to the SDCL group, NF-200 relative expression was remarkable in the Ad-miR-20a group in DRG tissues and dorsal column (Fig. 6b, c) (P < 0.05). These results confirmed that the miR-20a upregulation could promote the neurofilament synthesis and neurite regeneration in vivo. A normal typical SSEP waveform was observed in the sham group, while that was not recognized in the SDCL and Ad-NC groups. Ad-miR-20a restored the SSEP latency and amplitude as compared to the SDCL and Ad-NC groups, but poorer than the sham group. Compared to the sham group, N1-P1 amplitude values were declined in the Ad-miR-20a group (P < 0.05) and the N1 peak latency was decreased in the Ad-miR-20a group (P < 0.05). Ad-miR-20a recovered the amplitude value and improved the delayed latency time as compared to the Ad-NC and SDCL group (Fig. 6d–f). In the tape removal test, we recorded the time taken to sense and remove the tape (Fig. 6g, h). Rats in Sham group removed the tapes quickly, whereas the latency times of rats in Ad-NC and SDCL groups were delayed with no statistical difference (P > 0.05). Ad-miR-20a treated animals showed a moderate improvement of latency times compared to that in Ad-NC and SDCL groups for the sensory and removal of the tape (P > 0.05). However, the latency times from Ad-miR-20a group did not reach the values of Sham group (P > 0.05). These results indicated that the Ad-miR-20a could enhance the DRG neurons neurite growth and sensation function recovery after SDCL.

Fig. 6.

a Schematic representations of dorsal column lesion, adenovirus DRG injection, and the SSEP examination. b NF-200 immunohistochemistry stain of DRG tissues (top panel, × 400) and spinal cord dorsal column (bottom panel, × 200). c Relative integrated option density quantitative histogram of NF-200 immunohistochemistry images. d Representative average waveform curves of SSEP examination. e N1-P1 amplitude quantitative histogram of SSEP. f N1 latency quantitative histogram of SSEP. g, h The ability to sense and removal the adhesive tape on the hind paws was assessed by tape removal test. Data were expressed as mean ± SD of triplicate experiments. (n = 4, *P < 0.05). (SDCL: spinal cord dorsal column lesion; SCDC: spinal cord dorsal column; Ad-NC: adenovirus-negative control; Ad-miR-20a: adenovirus-microRNA-20a)

Discussion

After SCI, the rupture and demyelination of the axons in the lesion site directly lead to the interruption of peripheral sensory transmission. Therefore, the SCI causes not only the loss of motor function below the injury level but also the sensory dysfunction. In addition to proprioceptions and sensations loss, paresthesia, including chronic pain (Richards et al. 1980) and dysesthesias (Hoschouer et al. 2010), was formed after spinal cord injury. Aberrant sensations affect the cortical arousal and subsequently induce cognitive deficiency (Richards et al. 1982) and psychological issues (Krishnan et al. 1992).

The dorsal column of the T10 spinal cord is mainly composed of the central branch of the DRG neurons and transmits the sensation impulse, including tactile information, discriminatory touch, vibration and proprioception (Attwell et al. 2018). The complete damage of sensory ascending conductive pathway destroys or severely affects the sensory function to discriminate tactile textures, touch frequencies, and directions of moving tactile stimuli (Kaas et al. 2008). Disease that impairs the dorsal column can impair the sensory function. The demyelinated axons of dorsal column in tabes dorsalis contribute to the symptoms including loss of peripheral reflexes, impairment of vibration, position sense, and progressive ataxia. Severe pain could happen with no reason in tabes dorsalis (Al-Chalabi and Alsalman 2018). Patients with only dorsal column lesions were almost clarified as ASIA D injuries (McKinley et al. 2007).

MiRNAs have been widely known to participate in the pathophysiological process of SCI, and modulation of miRNA is one of the potential therapies (Gao et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2015; Xie et al. 2018). miR-20a, a member of miR-20a family (including miR-20a, miR-17-5p and miR-106b), could modulate neural stem cell and monocyte differentiation. miR-20a could also decrease Alzheimer’s Amyloid precursor protein (Hebert et al. 2009) and downregulated endogenous proteolipid protein in oligodendrocytes in Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease (Wang and Cambi 2012). Previous study reported that miR-20a plays a crucial role in modulating cortical neuron neurite growth via targeting PDZ-RhoGEF (Sun et al. 2013). This is the first research that confirmed that miR-20a is fully expressed in the dorsal root ganglion neuron and performs important functions. The PDZ-RhoGEF/RhoA/GAP43 axis, which promotes axonal outgrowth in cortical neurons, can exert a similar role in primary sensory neurons axons, i.e., spinal cord ascending sensory pathways.

After the extraction of DRG neurons from rats, the both branches of DRG neuronal axons are injured, and the length of the regrown neurite reflects the regenerative ability of DRG neuron. The axon growth and partial nerve remodeling are triggered by axon damage, which depends on the synthesis of proteins such as GAP-43 and NF-200. As markers of neurite, GAP43 and NF-200 are specifically expressed during neural development and participate in neurodevelopment, axon growth, and synapse formation (Yang and Tang 2017).

It is well known that the peripheral branches of DRG neuron axons could regenerate after injury, while it is difficult for central branches(Eva et al. 2017). The difficulties of regeneration faced by central branches of DRG neuron axons are thought to be greatly induced by the decreased intrinsic regenerative ability, the inhibitory microenvironment formed after injury and the ingredient differences of myelin sheath between peripheral and central axons (Ko et al. 2016). The two branches of DRG neurons share the same condition in in vitro experiments and do not have the myelin cells and microenvironment differences as in vivo experiments. Thus, our team calculated the average total axon length manually, which is a common method as reported in many literature (Kwon et al. 2013; Zhou et al. 2012). Then, the in vivo experiments were conducted to verify the function of miR-20a. The in vivo experiments complement the inadequacy of in vitro experiments, which further confirmed miR-20a could restore the sensory conductive function after spinal cord dorsal column injury.

As shown in Fig. 4a, the length of DRG neuron axon was shorter in inhibitory environment imitated by Nogo-A-Fc compared with that in control group. The transfection of miR-20a lowered the expression of the key downstream protein, GTP-RhoA, and facilitated the DRG neuron axon regeneration in inhibitory environment imitated by Nogo-A-Fc. The axon length in miR-20a&Nogo-A-Fc group was similar to that in control group and longer than that in Nogo-A-Fc group.

Post-SCI, glial scar, physically hinders the neuron axon regeneration, and the inhibitory molecules, distributed in the injured site matrix, contribute to the inhibitory microenvironment (Okada et al. 2018; Zhou et al. 2014). However, astrocyte contributes to neuroinflammation, compacted inflammatory cells and dense glial scar formation, and plays a controversial role in spinal cord injury (Cirillo et al. 2016; Papa et al. 2014). The inhibitory molecules in the microenvironment interact with the corresponding neuronal membranous receptors to trigger the intrinsic inhibitory signal pathway to prevent the axon regeneration. The neurite growth inhibitory factors, such as myelin-associated protein (MAP), Nogo, and oligodendrocyte myelin glycoprotein (OMgp) generated after SCI, constitute the inhibitory microenvironment and inhibit the axonal growth (Xu et al. 2016). Rho GTPases play an important role in the modulation of inhibitory signaling cues after inhibitory ligands bind to the Nogo-66 receptor (NgR) (Ahmed et al. 2011). The inhibition effect on neurite growth regulated by Nogo-A triggered by the interaction of Nogo-A and the NgR1-p75NTR receptor complex, increasing the association of p75NTR with RhoGDIα and releasing Rho-GDP that is converted to Rho-GTP by PDZ-RhoGEF (Sun et al. 2013). PDZ-RhoGEF belongs to a subgroup of the Dbl family of GEFs that functions upstream of RhoA GTPase in initiating the intracellular signaling in response to extracellular molecules or direct cell-to-cell interaction (Zheng 2001). PDZ-RhoGEF is expressed abundantly in the spinal cord dorsal horn, wherein primary nociceptive afferents terminate, and PDZ-RhoGEF is enriched in the nociceptive sensory neurons in DRG tissues (Kuner et al. 2002). PDZ-RhoGEF is a specific activator of RhoA and does not affect the other members of Rho-GTPase family (Reuther et al. 2001). RhoA inhibition strongly enhanced the axonal growth (Hu et al. 2016).

The SSEP, first reported in 1947, is an objectively, widely and reproducibly applied test to detect the integrity of sensory conduction pathway that origins from the peripheral sensor, through the spinal cord, to the brain (Caizhong et al. 2014; Han et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2018). It has been applied in both animal research and human in clinic (Wang et al. 2015b). The normal SSEP waveform consists of a negative N peak and a positive P peak. The latency of N peak is the time cost from the start of stimulation to the appearance of N peak. The N − P amplitude is the potential difference between N peak and P peak. The waveform of SSEP shows different characters in different phases and injured levels after spinal cord injury. Moreover, this method is also applied to the intraoperative monitoring (Wang et al. 2015b). Therefore, the SSEP test was chose for detecting the sensory function recovery after spinal cord dorsal column injury in this study. Also, the Ad-miR-20a DRG tissue injection restored the SSEP performance, and the values of SSEP N peak potential and N − P amplitude were still poorer than the Sham group. The reason of limited repair of sensory conductive function might be that although the Ad-miR-20a DRG tissue injection enhanced the intrinsic growth ability of axons, it could not affect the inhibitory molecules and relieve the physical blockage of dense glial scar in the injured site. Therefore, in future, the combination treatment of enhancing the intrinsic ability and inhibiting the extrinsic microenvironment could be more promising.

Collectively, the present results suggested that miR-20a overexpression inhibited the RhoA activity via targeting PDZ-RhoGEF and promoted the DRG neuronal axon growth and facilitated the sensory function recovery post-dorsal column injury.

In conclusion, this study is the first evidence that miR-20a/PDZ-RhoGEF/RhoA/GAP43 axis is involved in the axonal regeneration post-dorsal column injury, indicating that targeting this axis could improve the spinal cord sensory conduction function recovery. These findings indicated a new pathophysiology mechanism and provided novel therapeutic targets on SCI.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement and Animal Grouping

Eighty (weight, 240–260 g) adult female Wistar rats and four neonatal Wistar rats (age, < 24 h) were purchased from the Radiation Study Institute Animal Center (Tianjin, China) and housed at 12-h light/dark cycle with access to food and water ad libitum. The study was conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines (http://www.nc3rs.org.uk/ARRIVE) and National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications no. 85-23, revised 1996) and approved by the Ethics Committee of the 266th Hospital of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (Approval No. 20170038). Twenty-eight rats were employed for detecting the miR-20a expression post-spinal dorsal column injury. Forty-eight rats were randomly divided into sham, SDCL, Ad-negative control, and Ad-miR-20a groups. Four neonatal rats were used for DRG neuron culture.

Dorsal Column Injury Model Establishment

The dorsal column injury was generated based on previous researches (Wang et al. 2018). Anesthesia was administered, and the skin prepared and disinfected as per the routine protocol. A 2-cm-long skin incision was made over the thoracic 10 segmental spinous processes. The subcutaneous fascia and paravertebral muscles were bluntly dissected, and the lamina was exposed. The laminectomy was performed at the 10 thoracic vertebrae to expose the dorsal side of the spinal cord. Ophthalmic scissors were applied to open the theca vertebralis carefully. Subsequently, a pair of ophthalmic fine forceps were applied to pinch the dorsal branch of spinal cord tissues between the bilateral dorsal roots, sticking into the spinal cord 2 mm in depth and pinching tightly for 10 s (Neumann and Woolf 1999; Qiu et al. 2005). The gelatin sponge was pressed to stop bleeding, and the wound closed layer-by-layer. 0.3 mL/rat cefoperazone was injected intraperitoneally to prevent the wound infection.

Sample Collection and RNA Extraction

Chloral hydrate (10%, 3.3 mL/1 kg) was injected intraperitoneally to anesthetize the rats and cold saline was applied to perfuse. 1.5 cm spinal cord centered on the 10th segment of the thoracic vertebra, and L4-6 DRGs were collected.

The mirVana RNA Isolation Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) was applied for extracting the total RNA. Briefly, DRGs tissues were homogenized thoroughly in lysis/binding buffer. Then, the miRNA homogenate additive was added into the lysate and kept in 0 °C condition for 10 min. After adding acid‑phenol/chloroform to the lysate, 30–60 s vortex, and centrifuging at 10,000×g, the aqueous phase was collected. Subsequently, added absolute ethanol and vortexed fully. After passing through the filter cartridge by centrifuging at 10,000×g for 15 s, the filters were rinsed with wash solution 1 and two times with wash solution 2/3. The elution solution (95 °C) was applied to the filter, and the samples centrifuged at 10,000×g for 20–30 s to recover the RNA that was stored at − 80 °C for further experiments.

Real-Time Quantitative Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

MiScript II Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) or PrimerScript™ RT reagent kit (Takara Bio, Inc., Otsu, Japan) was applied to assess the microRNA and mRNA, respectively. Then the experiment was conducted on a LightCycler® 480 II RT-PCR Instrument (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) in a 10-µL reaction mixture. Each sample was performed three times.

Western Blot

DRG tissue samples and DRG neurons were collected and lysed in RIPA buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA) adding with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma‑Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). After quantification of the proteins with BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China), the samples were resolved by SDS–PAGE transferred to PVDF membranes. After incubation in blocking buffer overnight, the membranes were incubated with primary (anti-PDZ-RhoGEF antibody (1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), anti-RhoA antibody (1:500; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-GAP-43 antibody (1:500; Abcam), and anti-GAPDH antibody (1:500; Proteintech, Chicago, IL, USA)) and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:2000; Hua’an, Hangzhou, China), followed by image acquisition. The experiments were performed at least three times.

Transfection of siRNA

The transfection efficiency in DRG neurons was determined by transfecting with FITC-Oligo. A transfection efficiency of 95% was achieved. The scramble siRNA was applied as negative control. The siRNA sequence for PDZ-RhoGEF (5′-CCUCAUCUUCUACCAGCGCAU-3′ corresponding to PDZ-RhoGEF mRNA 2295–2315) was synthesized by Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd.C (China)(Lin et al. 2011). The transfection of siRNA was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as suggested by the manufacturer’s instructions. PDZ-RhoGEF knockdown efficiency was determined by Western blot analysis.

Assessment of Neurite Outgrowth in Cultured DRG Neurons

DRG tissues were dissociated and cultured as described previously(Jia et al. 2018). Briefly, the DRG tissues from neonatal rats were collected and digested into single cell suspension with 0.25% trypsin (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, U.S.). Then, the DRG neurons were cultured in poly-L-lysine (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, U.S.) coated plates with complete culture medium neurobasal medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA) supplied with NGF(50 ng/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA), B-27(2%, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA), and L-glutamine (1%, 0.2M, Gibco, USA).

Nogo-A-Fc (4 mg/ml, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, USA) was applied to inhibit axon growth. MiR-20a mimics, inhibitor, and scramble sequences (GenePharma, Shanghai, China), transfections were performed with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) on the 4th day of cell culture. 24-h post-transfection, standard DRG neuronal culture medium was changed. DRG neurons were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and immunofluorescence performed using anti-NF200 antibody (1:200; N4142, Sigma) and anti-IgG-Cy3 (1:200, BA1032, Boster, China), followed by DAPI (D9564, Sigma) staining, and fluorescence microscopy (Nikon TiU, Tokyo, Japan) was applied for capturing the neuronal images. Six images were acquired per well, and averaged total axon length from four well/group was calculated manually with the Image-Pro Plus (IPP) 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA).

Adenovirus Vector Preparation

The recombinant adenovirus of miR-20a was purchased from Yijun Co., Ltd.C (Tianjin, China). The precursor of Rno-miR-20a was synthesized and adenoviral vectors used for virus construction; Ad-miR-20a and Ad-NC-GFP were designed with the AdMax adenovirus system (Microbix Biosystems, Toronto, ON, Canada) and amplified in HEK293A cells. The HEK293A cells were from our laboratory.

The prepared adenovirus DRGs injections were conducted as described previously (Mason et al. 2010). The L4-L6 DRGs were exposed, followed by a puncture by a glass needle 400 µm in depth. After holding for 3 min, 1.1 µL adenovirus solution was injected at 0.2 µL/min, the needle was held for 5 min post-injection, removed, and sutured loosely. The expression of miR-20a in vivo was detected with RT-PCR 2 weeks after adenovirus injection.

Somatosensory-Evoked Potentials (SSEP)

SSEP is an objective electrophysiological analysis that reflects the sensory conductive pathway integrity (Han et al. 2011). SSEP was conducted 8-weeks post-dorsal column injury and adenovirus administration to clarify the sensory function improvement of miR-20a modulation as described previously (Han et al. 2011). Prior to record the SSEP data, intramuscular stimulator needle electrodes were inserted into the bilateral gastrocnemius muscle of hindlimb and make sure that only the stimulated hindlimb twitched lightly(2.1 mA, 4.1 Hz). The recording needle was inserted at the middle point between ears, and the reference needle was inserted at the root of nose. A custom peaks were consisted with a positive P1 peak and negative N1 peak of each averaged SSEP waveform. The averaged waves were obtained from 200 repetitions, and the latency time of N1 peak and the amplitude of N1-P1 were calculated to clarify the sensory condition. The detected data were averaged for four rats in each of the groups. Subsequently, the rats were killed for immunohistochemistry.

Tape Removal Test

The tape removal test assessed the competency of sensory function as reported previously with minor modulation (Fagoe et al. 2016; Moreno-Flores et al. 2006). The adhesivity of the tapes was such that they will not fall off spontaneously, and hair did not stick to the tape when it was removed. The results were not recorded if the tape was not fully stuck to the hindlimb. The data from both hindlimbs were averaged, and the estimations conducted three times. The baseline data were collected 1 week before the injury, and the removal latency was detected once a week for 8 weeks post-injury. The investigators were blinded to the treatment. Adhesive tapes (0.9 cm × 2.5 cm) were affixed to the palm of the hind paws, and the time latency to sense the affixed tape (indicated by paw shake), and the removal latency was recorded. If the animals could not sense the tape over 120 s, this time duration was recorded as the time latency (Moreno-Flores et al. 2006).

Immunohistochemistry

Following 10% paraformaldehyde perfusion to obtain spinal cord and DRG tissue specimens, the samples were sliced horizontally on frozen sections (16 µm). Slices were incubated in citrate buffer solution (pH 6.0, 0.1 mol/L) for 15 min under the microwave. Then, the slices were treated with 3% H2O2 to avoid endogenous peroxidase effect. Rabbit serum (10%) was applied to block the slices. The slices were incubated with anti-NF-200 (1:200; Abcam) at 4 °C O/N, incubated in anti-IgG/biotin (1:200; Abcam) for 1 h at room temperature. Then the slices were incubated with tertiary antibody streptavidin/HRP (1:400; Abcam) for 30 min at room temperature. DAB and hematoxylin were applied for staining of the slices.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were conducted at least three times. Data were showed as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s correction was conducted to analyze the differences. P value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the General Program of Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province of China (Grant Number H2017101030), the Medical Science and Technology Youth Cultivation Project of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (Grant Numbers 16QNP074 and 13QNP017), the Research and Development of Science and Technology Program Supported by Chengde Government (Grant Number 201606A062), the Beijing Municipal Education Commission General Project (KM201710025028), the Capital characteristic project (Z161100000116064), and the Public Experiment Training Foundation of Beijing Luhe Hospital, Capital Medical University, China (Grant Number lh201425Shi).

Author Contributions

XG, XZ and XC designed this study; ZW was in charge of the methodology; LC and MY were in charge of the software and validation; Formal analysis was done by YX; ZZ and WL were in charge of the investigation; FW was in charge of data curation; BL wrote the original draft; TW reviewed and edited the draft; XY was in charge of the visualization; YZ and XY supervised the study; TW administrated this study; Funding was acquired from TW; ZW, YZ and XC.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

ARRIVE guidelines and National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications no. 85-23, revised 1996) for the care and use of animals were followed. All protocols performed in this study were approved by the Ethics Committee of the 266th Hospital of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (Approval No. 20170038).

Footnotes

Tianyi Wang, Bo Li, Xin Yuan and Libin Cui have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Xiaoling Guo, Phone: +86-18632437171, Email: 870808116@qq.com.

Xiangyang Zhao, Phone: +86-13398660993, Email: wtyjjandt@sina.cn.

Xueming Chen, Phone: +86-13901346654, Email: sjxfcd@sina.com.

References

- Ahmed Z, Douglas MR, Read ML, Berry M, Logan A (2011) Citron kinase regulates axon growth through a pathway that converges on cofilin downstream of RhoA. Neurobiol Dis 41:421–429. 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Chalabi M, Alsalman I (2018) Neuroanatomy, posterior column (dorsal column). In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing LLC, Treasure Island (FL) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwell CL, van Zwieten M, Verhaagen J, Mason MRJ (2018) The dorsal column lesion model of spinal cord injury and its use in deciphering the neuron-intrinsic injury response. Dev Neurobiol. 10.1002/dneu.22601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalala OG, Pan L, Sahni V, Mcguire TL, Gruner K, Tourtellotte WG, Kessler JA (2012) microRNA-21 regulates astrocytic response following spinal cord injury. J Neurosci 32:17935–17947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caizhong X, Chunlei S, Beibei L, Zhiqing D, Qinneng D, Tong W (2014) The application of somatosensory evoked potentials in spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Neuro Rehabil 35:835–840 10.3233/NRE-141158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirillo G, Colangelo AM, De Luca C, Savarese L, Barillari MR, Alberghina L, Papa M (2016) Modulation of matrix metalloproteinases activity in the ventral horn of the spinal cord re-stores neuroglial synaptic homeostasis and neurotrophic support following peripheral nerve injury. PLoS ONE 11:e0152750. 10.1371/journal.pone.0152750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eva R, Koseki H, Kanamarlapudi V, Fawcett JW (2017) EFA6 regulates selective polarised transport and axon regeneration from the axon initial segment. J Cell Sci 130:3663–3675. 10.1242/jcs.207423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagoe ND, Attwell CL, Eggers R, Tuinenbreijer L, Kouwenhoven D, Verhaagen J, Mason MR (2016) Evaluation of five tests for sensitivity to functional deficits following cervical or thoracic dorsal column transection in the rat. PLoS ONE 11:e0150141. 10.1371/journal.pone.0150141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L, Dai C, Feng Z, Zhang L, Zhang Z (2018) MiR-137 inhibited inflammatory response and apoptosis after spinal cord injury via targeting of MK2. J Cell Biochem 119:3280–3292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goganau I, Sandner B, Weidner N, Fouad K, Blesch A (2017) Depolarization and electrical stimulation enhance in vitro and in vivo sensory axon growth after spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol 300:247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X et al (2011) Simvastatin treatment improves functional recovery after experimental spinal cord injury by upregulating the expression of BDNF and GDNF. Neurosci Lett 487:255–259. 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert SS, Horre K, Nicolai L, Bergmans B, Papadopoulou AS, Delacourte A, De Strooper B (2009) MicroRNA regulation of Alzheimer’s Amyloid precursor protein expression. Neurobiol Dis 33:422–428. 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoschouer EL, Finseth T, Flinn S, Basso DM, Jakeman LB (2010) Sensory stimulation prior to spinal cord injury induces post-injury dysesthesia in mice. J Neurotrauma 27:777–787. 10.1089/neu.2009.1182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Zhang G, Rodemer W, Jin LQ, Shifman M, Selzer ME (2016) The role of RhoA in retrograde neuronal death and axon regeneration after spinal cord injury. Neurobiol Dis 98:25–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L, Chopp M, Wang L, Lu X, Zhang Y, Szalad A, Zhang ZG (2018) MiR-34a regulates axonal growth of dorsal root ganglia neurons by targeting FOXP2 and VAT1 in postnatal and adult mouse. Mol Neurobiol 10.1007/s12035-018-1047-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH, Qi HX, Burish MJ, Gharbawie OA, Onifer SM, Massey JM (2008) Cortical and subcortical plasticity in the brains of humans, primates, and rats after damage to sensory afferents in the dorsal columns of the spinal cord. Exp Neurol 209:407–416. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko HR et al (2016) Akt1-Inhibitor of DNA binding2 is essential for growth cone formation and axon growth and promotes central nervous system axon regeneration. Elife 5:e20799 10.7554/eLife.20799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan KR, Glass CA, Turner SM, Watt JW, Fraser MH (1992) Perceptual deprivation in the acute phase of spinal injury rehabilitation. J Am Parapleg Soc 15:60–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuner R, Swiercz JM, Zywietz A, Tappe A, Offermanns S (2002) Characterization of the expression of PDZ-RhoGEF, LARG and G(alpha)12/G(alpha)13 proteins in the murine nervous system. Eur J Neurosci 16:2333–2341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon MJ et al (2013) Contribution of macrophages to enhanced regenerative capacity of dorsal root ganglia sensory neurons by conditioning injury. J Neurosci 33:15095–15108. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0278-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MY, Lin YM, Kao TC, Chuang HH, Chen RH (2011) PDZ-RhoGEF ubiquitination by Cullin3-KLHL20 controls neurotrophin-induced neurite outgrowth. J Cell Biol 193:985–994. 10.1083/jcb.201103015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Huang Y, Jia C, Li Y, Liang F, Fu Q (2015) Administration of antagomir-223 inhibits apoptosis, promotes angiogenesis and functional recovery in rats with spinal cord injury. Cell Mol Neurobiol 35:483–491. 10.1007/s10571-014-0142-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason MR et al (2010) Comparison of AAV serotypes for gene delivery to dorsal root ganglion neurons. Mol Ther 18:715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley W, Santos K, Meade M, Brooke K (2007) Incidence and outcomes of spinal cord injury clinical syndromes. J Spinal Cord Med 30:215–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Flores MT et al (2006) A clonal cell line from immortalized olfactory ensheathing glia promotes functional recovery in the injured spinal cord. Mol Ther 13:598–608. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann S, Woolf CJ (1999) Regeneration of dorsal column fibers into and beyond the lesion site following adult spinal cord injury. Neuron 23:83–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederost B, Oertle T, Fritsche J, McKinney RA, Bandtlow CE (2002) Nogo-A and myelin-associated glycoprotein mediate neurite growth inhibition by antagonistic regulation of RhoA and Rac1. J Neurosci 22:10368–10376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada S, Hara M, Kobayakawa K, Matsumoto Y, Nakashima Y (2018) Astrocyte reactivity and astrogliosis after spinal cord injury. Neurosci Res 126:39–43. 10.1016/j.neures.2017.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa M, De Luca C, Petta F, Alberghina L, Cirillo G (2014) Astrocyte-neuron interplay in maladaptive plasticity. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 42:35–54. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J, Cafferty WB, McMahon SB, Thompson SW (2005) Conditioning injury-induced spinal axon regeneration requires signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 activation. J Neurosci 25:1645–1653. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3269-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuther GW et al (2001) Leukemia-associated Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor, a Dbl family protein found mutated in leukemia, causes transformation by activation of RhoA. J Biol Chem 276:27145–27151. 10.1074/jbc.M103565200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JS, Meredith RL, Nepomuceno C, Fine PR, Bennett G (1980) Psycho-social aspects of chronic pain in spinal cord injury. Pain 8:355–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JS, Hirt M, Melamed L (1982) Spinal cord injury: a sensory restriction perspective. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 63:195–199 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ropper AE, Ropper AH (2017) Acute Spinal Cord Compression N. Engl J Med 376:1358–1369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang X et al (2013) Small-molecule inhibitors targeting G-protein-coupled Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:3155–3160. 10.1073/pnas.1212324110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Zhou Z, Fink DJ, Mata M (2013) HspB1 silences translation of PDZ-RhoGEF by enhancing miR-20a and miR-128 expression to promote neurite extension. Mol Cell Neurosci 57:111–119. 10.1016/j.mcn.2013.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang E, Cambi F (2012) MicroRNA expression in mouse oligodendrocytes and regulation of proteolipid protein gene expression. J Neurosci Res 90:1701–1712. 10.1002/jnr.23055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W et al (2014) SNAP25 ameliorates sensory deficit in rats with spinal cord transection. Mol Neurobiol 50:290–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T et al (2015a) miR-142-3p is a potential therapeutic target for sensory function recovery of spinal cord injury medical science monitor international medical. J Exp Clin Res 21:2553–2556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Cui H, Pu J, Luk KDK, Hu Y (2015b) Time-frequency patterns of somatosensory evoked potentials in predicting the location of spinal cord injury. Neurosci Lett 603:37–41. 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z et al (2018) PEITC promotes neurite growth in Primary sensory neurons via the miR-17-5p/STAT3/GAP-43 Axis J Drug Target. 10.1080/1061186x.2018.1486405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W et al (2018) Knockdown of MicroRNA-21 promotes neurological recovery after acute spinal cord injury. Neurochem Res 10.1007/s11064-018-2580-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, He J, He H, Peng R, Xi J (2016) Comparison of RNAi NgR and NEP1-40 in acting on axonal regeneration after spinal cord injury in rat. Models Mol Neurobiol 54:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Tang W-Y (2017) Resistance of interleukin-6 to the extracellular inhibitory environment promotes axonal regeneration and functional recovery following spinal cord injury. Int J Mol Med 39(2):437–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Lei F, Zhou Q, Feng D, Bai Y (2016) Combined application of Rho-ROCKII and GSK-3β inhibitors exerts an improved protective effect on axonal regeneration in rats with spinal cord injury Molecular Medicine Reports 14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zheng Y (2001) Dbl family guanine nucleotide exchange factors. Trends Biochem sci 26:724–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S et al (2012) microRNA-222 targeting PTEN promotes neurite outgrowth from adult dorsal root ganglion neurons following sciatic nerve transection. PLoS ONE 7:e44768. 10.1371/journal.pone.0044768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y et al (2014) Matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) expression in rat spinal cord injury model. Cell Mol Neurobiol 34:1151–1163. 10.1007/s10571-014-0090-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]