Abstract

Viral RNA level in plasma is a sensitive experimental endpoint for evaluating the efficacy of AIDS vaccines or therapies in nonhuman primates. By quantifying viral RNA in the plasma of 77 rhesus monkeys for 10 weeks after inoculation with simian-human immunodeficiency virus 89.6P (SHIV-89.6P) or simian immunodeficiency virus mac 251 (SIVmac 251), we estimated variability in three viral load (VL) measures: peak VL, the postacute set point VL, and VL decline from peak. Such estimates of biological variability are essential for determining the number of animals needed per group and may be helpful for selecting the most appropriate measure to use as the experimental endpoint. Peak VL was positively correlated with set point VL for both viruses. Variability (standard deviation) was substantially higher in monkeys infected with SIVmac 251 than in those infected with SHIV-89.6P for set point VL and VL decline. The variability of peak VL was less than one-half that of set point VL variability and only about two-thirds of that of VL decline, implying that the same treatment-related difference in peak VL could be detected with fewer animals than set point VL or VL decline. Thus, differences in VL variability over the course of infection and between viruses need to be considered when designing studies using the nonhuman primate AIDS models.

While the goals for developing AIDS vaccines or therapies are to prevent or eradicate virus infection, neither is achievable at this time. In human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected humans, the viral load (VL) in plasma can predict clinical outcome (10). Furthermore, therapies which decrease VL in plasma slow clinical progression after HIV infection (17). Thus, there is a rationale for pursuing interventional strategies that may not abort or eliminate virus infection but can reduce VL.

Nonhuman primate models of AIDS play an important role in testing the efficacy of HIV therapies and vaccines (6, 11, 12). These models permit repeated measurement of VL throughout the course of infection. The clinical outcome after simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection of rhesus monkeys has been predicted by the VL in plasma achieved during peak viremia (20) and during the postacute set point (20, 23) or by the change from peak to set point (21). Furthermore, experimental interventions that reduce peak viremia or lower the postacute VL set point delay clinical sequelae (1, 7, 9). Thus, plasma VL measurements can serve as sensitive experimental endpoints and may be useful surrogate markers for clinical endpoints in these models.

There are often ethical, practical, and financial constraints on the number of nonhuman primates used in such experiments. Thus, estimates of between-animal variability in VL measures are needed to ensure that the minimum number of animals are used to identify scientifically important differences in the VL measures as statistically significant. In addition, understanding how variability in the VL in plasma changes during the course of infection may help in choosing the most appropriate experimental endpoint.

We estimated the variability in three commonly used plasma VL measures by analyzing log10 RNA copies/ml data from 77 Indian rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) infected intravenously with either simian-human immunodeficiency virus 89.6P (SHIV-89.6P) (n = 45) or simian immunodeficiency virus mac 251 (SIVmac 251) (n = 32). Monkeys had been enrolled as controls in 22 vaccine, therapy, or pathogenesis studies (Table 1). All SHIV-89.6P inoculations used the same biological isolate that had undergone one additional in vivo passage after its initial description (16). This stock was expanded in rhesus monkey peripheral blood mononuclear cells. SIVmac inoculations used three different stocks of the 251 biological isolate expanded in rhesus or human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. One stock accounted for 7 of the 11 SIVmac experiments (63% of the 32 animals); the other two stocks accounted for 3 of the 11 experiments (28% of the animals) and 1 experiment (9% of the animals), respectively. All virus stocks had been titrated in vivo, and the inoculum was approximately 10 times that shown to reproducibly infect all rhesus monkeys. EDTA or acid-citrate-dextrose plasma specimens were obtained at various times after inoculation. In each monkey, 3 to 12 specimens were collected from 7 to 70 days after inoculation (for SHIV-89.6P, the median was 8 specimens per animal; for SIVmac 251, the median was 6 specimens per animal) and stored at −70°C until analyzed. The virus in plasma was quantified using branched DNA amplification assay (bDNA) (14) (17 experiments; 78% of animals), quantitative competitive (QC)-PCR (23) (2 experiments; 10% of animals), or real-time reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR (22) (3 experiments; 12% of animals) assays. The interassay precision levels of these different methods were all similar (the percent coefficient of variation was 25 to 39% [22, 23; Bayer Reference Testing Laboratory, personal communication]), and there was no evidence for variability across the assays. All monkeys were maintained in accordance with the guidelines of the Committee on Animals for the Harvard Medical School, or in accordance with the guidelines of the analogous animal care and use committees at collaborating institutions, and the Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals (13).

TABLE 1.

Description and results of individual experiments with summary by virus

| Infecting virus | Expt. no. id | Treatmenta | Sourceb or reference | Virus stockc | Viral load assay | LODd (RNA copies/ml) | No. of animals | Peak VL (log10 RNA copies/ml)

|

Set point VL (log10 RNA copies/ml)

|

VL decline (log10 RNA copies/ml)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||||||

| SHIV-89.6P | 1 | NT | UD | A | bDNA | 1,500 | 2 | 8.36 | 0.23 | 5.68 | 0.51 | 2.68 | 0.74 |

| 2 | NT | UD | A | bDNA | 500 | 2 | 6.62 | 0.41 | 3.97 | 0.77 | 2.66 | 1.17 | |

| 3 | IPI | NL | A | bDNA | 1,500 | 3 | 8.30 | 0.04 | 5.45 | 1.34 | 2.85 | 1.32 | |

| 4 | NT | KM | A | bDNA | 1,500 | 3 | 8.68 | 0.30 | 6.16 | 0.97 | 2.52 | 0.99 | |

| 5 | NT | 15 | A | QC-PCR | 10,000 | 4 | 8.44 | 0.45 | 5.32 | 0.52 | 3.12 | 0.55 | |

| 6 | IPI | NL | A | bDNA | 500 | 4 | 8.09 | 0.20 | 4.84 | 0.21 | 3.25 | 0.20 | |

| 7 | IAA | KM | A | bDNA | 1,500 | 4 | 8.23 | 0.47 | 5.52 | 0.95 | 2.71 | 0.48 | |

| 8 | CVI | DB | A | RT-PCR | 500 | 4 | 8.19 | 0.36 | 4.82 | 0.92 | 3.37 | 0.76 | |

| 9 | NT | KM | A | bDNA | 1,500 | 5 | 8.15 | 0.38 | 5.52 | 0.88 | 2.63 | 0.71 | |

| 10 | NT | NL | A | bDNA | 500 | 6 | 7.82 | 0.35 | 5.05 | 0.66 | 2.77 | 0.42 | |

| 11 | IDI | 1 | A | bDNA | 500 | 8 | 7.81 | 0.49 | 5.40 | 0.64 | 2.41 | 0.33 | |

| Overalle | 45 | 8.06 | 0.38 | 5.27 | 0.78 | 2.79 | 0.65 | ||||||

| SD97.5 | 0.50 | 1.02 | 0.86 | ||||||||||

| SIVmac 251 | 12 | IMA | 18 | B | bDNA | 1,500 | 2 | 7.90 | 0.13 | 5.81 | 2.04 | 2.08 | 2.17 |

| 13 | IMA | UD | B | bDNA | 1,500 | 2 | 7.94 | 0.43 | 5.79 | 0.90 | 2.14 | 0.47 | |

| 14 | NT | 19 | B | bDNA | 1,500 | 2 | 7.68 | 0.29 | 5.80 | 0.15 | 1.89 | 0.44 | |

| 15 | NT | UD | C | bDNA | 1,500 | 2 | 7.80 | 0.46 | 6.12 | 2.09 | 1.69 | 1.63 | |

| 16 | IMA | UD | B | bDNA | 1,500 | 2 | 7.36 | 0.35 | 5.79 | 0.37 | 1.57 | 0.02 | |

| 17 | NT | UD | C | RT-PCR | 100 | 2 | 7.39 | 0.26 | 6.28 | 0.99 | 1.10 | 0.74 | |

| 18 | NT | RV | D | RT-PCR | 125 | 3 | 7.21 | 0.04 | 5.34 | 0.34 | 1.87 | 0.35 | |

| 19 | IMA | 18 | B | bDNA | 1,500 | 4 | 7.82 | 0.44 | 6.45 | 0.91 | 1.37 | 0.92 | |

| 20 | NT | 15 | B | QC-PCR | 10,000 | 4 | 7.72 | 0.38 | 5.73 | 0.82 | 1.99 | 0.45 | |

| 21 | NT | UD; 8 | B | bDNA | 500 | 4 | 7.49 | 0.11 | 5.34 | 0.77 | 2.15 | 0.82 | |

| 22 | NT | KM | C | bDNA | 1,500 | 5 | 7.82 | 0.67 | 6.49 | 1.37 | 1.33 | 0.77 | |

| Overalle | 32 | 7.66 | 0.41 | 5.93 | 1.08 | 1.73 | 0.88 | ||||||

| SD97.5 | 0.59 | 1.54 | 1.25 | ||||||||||

Treatment abbreviations: CVI, control vaccinia immunization; IAA, immunization adjuvant alone; IDI, irrelevant DNA immunization; IMA, irrelevant monoclonal antibody; IPI, irrelevant peptide immunization; NT, no treatment.

Source of data abbreviations: DB, D. Barouch, personal communication; KM, K. Manson, personal communication; NL, N. Letvin, personal communication; RV, R. Veazey, personal communication; UD, unpublished data.

A single virus stock (A) was used for all SHIV-89.6P inoculations. Three SIVmac 251 stocks (B to D) generated in different laboratories were used.

LOD, limit of detection for each assay at the time experiment was performed.

Overall results are means and the standard deviations calculated from the residual sum of squares.

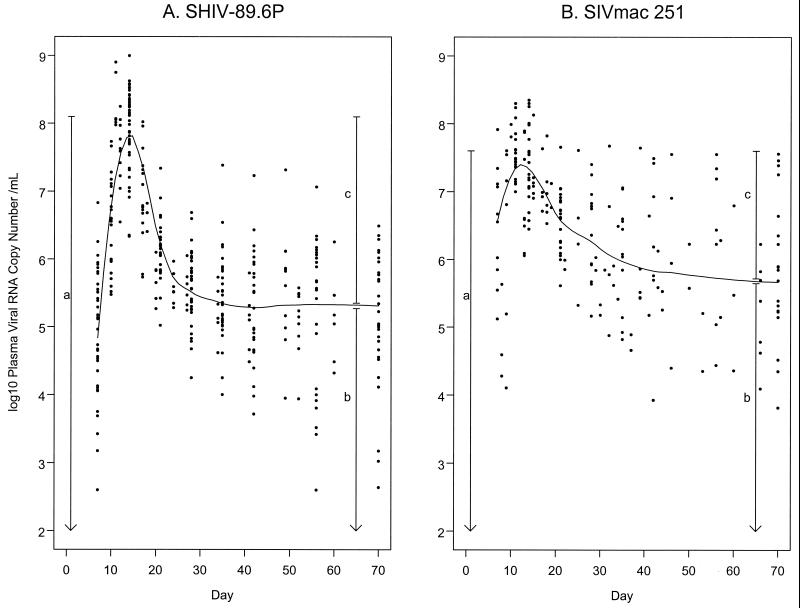

Infection with either virus resulted in peak VL between day 7 and 17 after inoculation in all animals, followed by a rapid decline (Fig. 1). The decline from peak, illustrated by the smoothed robust local regression line, appeared more rapid for monkeys infected with SHIV-89.6P than for monkeys infected with SIVmac 251. The VL in plasma then reached a plateau after infection with either virus.

FIG. 1.

Summary of viral RNA levels in plasma over time. The smoothed curve is the estimated viral load using a smoothed local regression (LOESS), with a quadratic fit, symmetric error distribution, and span of 0.50 (2). The vertical lines provide a graphical interpretation of peak VL (a), set point VL (b), and VL decline (c). (A) Analysis of 45 rhesus monkeys inoculated with SHIV-89.6P, with 4 to 12 observations per animal between days 7 and 70. Four measurements were less than the limit of detection (LOD) on day 7, one measurement was below LOD on day 56, and one measurement was below LOD on day 70. These values are shown in Fig. 1 and included in the analysis as the LOD value. There are also two measurements which exceeded the upper limit of the assay (8.486) on day 14 and were not tested at higher dilutions. These values are shown in Fig. 1 and included in the analysis as 8.486. (B) Analysis of 32 rhesus monkeys inoculated with SIVmac 251, with 3 to 11 observations per animal between days 7 and 70. No measurements were outside the ranges of the assays.

Because of their relevance as endpoints, demonstrated in previous studies, three VL measures were calculated (Fig. 1). Peak VL was defined as the maximum VL measured between days 7 to 17 inclusive after inoculation for each animal. Postacute set point (set point VL) was defined as the average value for an animal from days 35 to 70 inclusive. To determine when VL reached a plateau after the acute phase, we performed a preliminary analysis of stability over time separately for each virus, using mixed models analysis of variance (3) adjusting for experiment. By analyzing the range of 21 to 70 days and sequentially removing weeks (beginning at day 21) until there was no evidence for a significant time trend, we determined that the postacute VL in plasma was stable for both viruses from day 35 to day 70 inclusive. Decline from peak VL to set point VL (VL decline) was calculated as peak VL minus set point VL. For both SHIV-89.6P and SIVmac 251 infections, there was a significant positive correlation between peak VL and set point VL (for SHIV-89.6P, r = 0.60; for SIVmac 251, r = 0.62; for both, P < 0.001). In SHIV-89.6P infections, peak VL was higher (P < 0.001) while set point VL was lower (P < 0.01) than in SIVmac 251-infected monkeys. As a result, VL decline was smaller in SIVmac 251 than in SHIV-89.6P infections (P < 0.001).

Two estimates of variability for each of the three VL measures were made. First, the mean and within-experiment standard deviation (SDwe) were calculated for each experiment (Table 1). The overall standard deviation (SDov) was calculated from the residual sum of squares across experiments. We also calculated a more conservative estimate of variability (SD97.5) using the approximate 95% confidence interval (CI) for SDov using Satterthwaite's formula (4). SD97.5 would be expected to exceed SDwe in 97.5% of experiments, but there was usually at least one experiment, and for VL decline in SIVmac 251 there were three, in which SDwe exceeded SD97.5.

To assess the reliability of our variability estimates, we tested whether variances were homogenous across experiments. Despite a wide range in SDwe, there was no consistent evidence suggesting significant heterogeneity of variance across experiments for either virus in peak VL or set point VL measures. For VL decline, however, there was consistent evidence for heterogeneity of variance between experiments for both viruses (both P < 0.01 by Levene's test [5]). Thus, our estimates of SDov and SD97.5 for VL decline may be less useful than our estimates for the other two VL measures.

For each virus, substantial differences were observed in the estimated variability of the three VL measures. Variability differed for VL measures between the viruses to a lesser extent (Table 1). SDov for peak VL were similar for the two viruses (for SHIV-89.6P, 0.385 log10 viral RNA level in plasma; 95% CI, 0.311 to 0.504; for SIVmac 251, 0.412; 95% CI, 0.317 to 0.589), but were substantially less than the variability for both set point VL (for SHIV-89.6P, 0.780; 95% CI, 0.631 to 1.022; for SIVmac 251, 1.080; 95% CI, 0.831 to 1.544) and VL decline (for SHIV-89.6P, 0.653; 95% CI, 0.528 to 0.855; for SIVmac 251, 0.876; 95% CI, 0.674 to 1.252).

It is not clear why peak VL should exhibit less variability than set point VL. As peak VL is the highest of several measurements, from statistical theory one would expect that peak VL should be more variable than set point VL, an average of several measurements, assuming equal variability for each individual VL measurement over time. The absence of virus-specific immune responses during primary infection would result in unchecked virus replication in all animals during this early period, which may reduce the variability in peak VL. The existence of a large pool of susceptible target cells during primary infection might also result in more consistent peak VL levels between animals. In contrast, during the VL plateau phase, animals may differ substantially in the magnitude of their immune response to the virus. In addition, there may be greater differences between animals in the number of target cells susceptible to infection later in the course of the infection. These features could result in more between-animal variation in set point VL than in peak VL. As our data were limited to the first 10 weeks after inoculation, it is possible that the variability of set point VL defined as the average over a different period of time, or the related VL decline, would differ from our estimates.

Differences in variability were also noted between viruses. Although the overall standard deviation (SDov) for peak VL were similar for the two viruses, there was suggestive evidence that the variability in set point VL and VL decline was greater for SIVmac 251 infection than for SHIV-89.6P (for set point VL, P = 0.09; for VL decline, P = 0.13 in the likelihood-ratio test, mixed models analysis of variance). There was no evidence that a difference in genetic heterogeneity between the two groups was a likely explanation of the difference between viruses. Forty-eight percent of the SHIV-infected and 43% of the SIV-infected groups were positive for the rhesus major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I allele, Mamu A*01, among those tested (47 and 44%, respectively). The use of three different virus stocks in the SIVmac 251 experiments, however, might have led to additional variability in VL measures.

The higher variability in set point VL and VL decline in SIVmac 251 compared to SHIV-89.6P, however, may reflect differences between the two viruses in the outcome of infection. SHIV-89.6P infection results in a rapid and consistent progression to CD4 lymphopenia, minimal antiviral immune responses and AIDS-like pathological changes (15), while infection with SIVmac 251 results in variable antiviral immune responses and a wider range of clinical outcomes, from death within weeks to chronic infection with long term survival (20, 21, 23).

Our variability estimates were then used to calculate sample size (number of animals needed per group) to detect various differences in the three VL measures. Sample size was calculated assuming a two-group experiment with groups of equal sizes, equal variability across groups, and analysis using a standard t test with α = 0.05 two-sided. Because variability was lower, experiments using peak VL as the primary endpoint would require fewer animals than experiments using set point VL or VL decline to detect the same difference. For example, four animals per group would be required to detect a difference of 1.0 log10 RNA copies/ml for peak VL between the two groups with 80% power for either virus. At least twice as many animals per group would be required to detect the same difference for the other endpoints (for SHIV-89.6P, 11 for set point VL and 8 for VL decline; for SIVmac 251, 20 for set point VL and 14 for VL decline). Experiments using SHIV-89.6P generally require smaller sample sizes than do experiments using SIVmac 251 in order to detect the same difference in each VL measure.

Sample sizes that could detect a range of differences in VL (log10 viral RNA copy number/ml) between groups, at both 80 and 90% power, assuming either SDov or SD97.5, were calculated (Table 2). Since SD97.5 is a larger estimate of variability, increasing the number of animals needed, it may be considered an example of what might be needed if an experimenter were unlucky and a larger-than-expected variability was observed. To illustrate the use of Table 2, consider an experiment with six monkeys per group using SHIV-89.6P. Using the section headed “Sample size using estimated SD,” there would be 80% power to detect a 0.75 log10 difference in peak VL, a 1.50 log10 difference in set point VL, and a 1.25 log10 difference in VL decline using six animals per group. If the variability exceeds SDov but is not more than SD97.5, six animals/group would have 80% power to detect a 1.00 log10 difference in peak VL, a 2.00 log10 difference in set point VL, and a 1.75 log10 difference in VL decline (Table 2, “Sample size using upper 95% confidence limit for SD”). If 90% power were needed, sample size would have to increase from 6 to 7 animals per group to detect the same differences in VL measures. Given the variability in VL decline across experiments, however, the sample size may need to be even larger for this endpoint.

TABLE 2.

Sample size requirements for each group for different effect sizes and VL measures

| Infecting virus | Measure | DDa and power | SDov | Sample size using estimated SD | SD97.5 | Sample size using upper 95% confidence limit for SD | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHIV-89.6P | ||||||||||||||||

| DD | 0.50 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 1.25 | 1.50 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 1.25 | 1.50 | 2.00 | ||||

| Peak VL | 80% | 0.385 | 11 | 6 | 4 | 3b | 3b | 3b | 0.504 | 17 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 3b | |

| 90% | 14 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 3b | 3b | 23 | 11 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 3b | ||||

| DD | 1.00 | 1.25 | 1.50 | 1.75 | 2.00 | 2.50 | 1.00 | 1.25 | 1.50 | 1.75 | 2.00 | 2.50 | ||||

| Set point VL | 80% | 0.780 | 11 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3b | 1.022 | 18 | 12 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 4 | |

| 90% | 14 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 23 | 16 | 11 | 9 | 7 | 5 | ||||

| DD | 1.00 | 1.25 | 1.50 | 1.75 | 2.00 | 2.50 | 1.00 | 1.25 | 1.50 | 1.75 | 2.00 | 2.50 | ||||

| VL decline | 80% | 0.653 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3b | 13 | 9 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | ||

| 90% | 11 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3b | 0.855 | 17 | 11 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 4 | |||

| SIVmac 251 | ||||||||||||||||

| DD | 0.75 | 1.00 | 1.25 | 1.50 | 1.75 | 2.00 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 1.25 | 1.50 | 1.75 | 2.00 | ||||

| Peak VL | 80% | 0.412 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 3b | 3b | 3b | 0.589 | 11 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3b | |

| 90% | 8 | 5 | 4 | 3b | 3b | 3b | 14 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 4 | ||||

| DD | 1.50 | 1.75 | 2.00 | 2.25 | 2.50 | 3.00 | 1.50 | 1.75 | 2.00 | 2.25 | 2.50 | 3.00 | ||||

| Set point VL | 80% | 1.080 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 1.544 | 18 | 14 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 6 | |

| 90% | 12 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 24 | 18 | 14 | 11 | 10 | 7 | ||||

| DD | 1.25 | 1.50 | 1.75 | 2.00 | 2.25 | 2.50 | 1.25 | 1.50 | 1.75 | 2.00 | 2.25 | 2.50 | ||||

| VL decline | 80% | 0.876 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 1.252 | 17 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 6 | |

| 90% | 12 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 23 | 16 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 7 | ||||

Mean detectable difference (DD) in log10 RNA copies/ml between experimental and control groups. Note that for experiments with SHIV-89.6P, the smallest difference reported for peak VL is 0.50, while for set point VL and VL decline the smallest difference reported is 1.00. Also, the smallest detectable difference reported is smaller for each measurement (peak VL, set point VL, and VL decline) for SHIV-89.6P virus than for SIVmac 251, reflecting the larger estimated standard deviation in the SIVmac 251 virus.

Although calculations suggest that three animals per group would be adequate, we do not recommend experiments with less than four animals per group.

These variability estimates include assay variability, both within an individual assay and with three different assay methods (bDNA, QC-PCR, and real-time RT-PCR), and all the potential factors affecting biological variability between animals. Data were pooled from 22 different studies by multiple investigators. These studies had a number of differences in design, control therapy, and sampling times. For SIVmac 251, experiments used three different virus stocks. Thus, our estimates of variability should be quite robust.

Our estimates of variability for these three measures of VL in plasma will be useful in helping to select the appropriate VL measure to use as the experimental endpoint and to determine the necessary sample size per group. The differences we observed between SHIV-89.6P and SIVmac 251 suggest that these variability estimates and sample sizes may need to be determined for other viruses or other nonhuman primate species. Our sample size calculations assume that a t test is used to compare means between groups. Use of nonparametric tests, such as the Wilcoxon rank sum test, might require a slightly larger sample size to obtain the same power. Our estimates of variability will also be useful when determining sample size for experiments involving more than two groups of animals or using alternative statistical tests for data analysis, with the advice of a statistician.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants HL59747, RR13150, and RR00168.

We thank Dan Barouch, Norman Letvin, Kelledy Manson, and Ronald Veazey for contributing to the data used in the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barouch D H, Santra S, Schmitz J E, Kuroda M J, Fu T M, Wagner W, Bilska M, Craiu A, Zheng X X, Krivulka G R, Beaudry K, Lifton M A, Nickerson C E, Trigona W L, Punt K, Freed D C, Guan L, Dubey S, Casimiro D, Simon A, Davies M E, Chastain M, Strom T B, Gelman R S, Montefiori D C, Lewis M G, Emini E A, Shiver J W, Letvin N L. Control of viremia and prevention of clinical AIDS in rhesus monkeys by cytokine-augmented DNA vaccination. Science. 2000;290:486–492. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5491.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cleveland W S, Devlin S J. Locally weighted regression: an approach to regression analysis by local fitting. J Am Statist Assoc. 1988;83:596–610. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diggle P J, Liang K Y, Zeger S L. Analysis of longitudinal data. Oxford, United Kingdom: Clarendon Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaylor D W. Satterthwaite's formula. In: Kotz S, Johnson N L, Read C B, editors. Encyclopedia of statistical sciences. Vol. 8. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1988. pp. 261–262. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glaser R E. Levene's robust test of homogeneity of variances. In: Kotz S, Johnson N L, Read C B, editors. Encyclopedia of statistical sciences. Vol. 4. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1983. pp. 608–610. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haigwood N L. Progress and challenges in therapies for AIDS in nonhuman primate models. J Med Primatol. 1999;28:154–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.1999.tb00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirsch V M, Fuerst T R, Sutter G, Carroll M W, Yang L C, Goldstein S, Piatak M, Jr, Elkins W R, Alvord W G, Montefiori D C, Moss B, Lifson J D. Patterns of viral replication correlate with outcome in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected macaques: effect of prior immunization with a trivalent SIV vaccine in modified vaccinia virus Ankara. J Virol. 1996;70:3741–3752. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3741-3752.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuroda M J, Schmitz J E, Charini W A, Nickerson C E, Lifton M A, Lord C I, Forman M A, Letvin N L. Emergence of CTL coincides with the clearance of virus during primary simian immunodeficiency virus infection in rhesus monkeys. J Immunol. 1999;162:5127–5133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lifson J D, Rossio J L, Arnaout R, Li L, Parks T L, Schneider D K, Kiser R F, Coalter V J, Walsh G, Imming R J, Fisher B, Flynn B M, Bischofberger N, Piatak M, Jr, Hirsch V M, Nowak M A, Wodarz D. Containment of simian immunodeficiency virus infection: cellular immune responses and protection from rechallenge following transient postinoculation antiretroviral treatment. J Virol. 2000;74:2584–2593. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.6.2584-2593.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mellors J W, Rinaldo C R, Jr, Gupta P, White R M, Todd J A, Kingsley L A. Prognosis in HIV-1 infection predicted by the quantity of virus in plasma. Science. 1996;272:1167–1170. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5265.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nath B M, Schumann K E, Boyer J D. The chimpanzee and other non-human-primate models in HIV-1 vaccine research. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:426–431. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01816-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nathanson N, Hirsch V M, Mathieson B J. The role of nonhuman primates in the development of an AIDS vaccine. AIDS. 1999;13(Suppl. A):S113–S120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Research Council. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pachl C, Todd J A, Kern D G, Sheridan P J, Fong S J, Stempien M, Hoo B, Besemer D, Yeghiazarian T, Irvine B, Kolberg J, Kokka R, Neuwald P, Urdea M S. Rapid and precise quantification of HIV-1 RNA in plasma using a branched DNA signal amplification assay. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;8:446–454. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199504120-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reimann K A, Watson A, Dailey P J, Lin W, Lord C I, Steenbeke T D, Parker R A, Axthelm M K, Karlsson G B. Viral burden and disease progression in rhesus monkeys infected with chimeric simian-human immunodeficiency viruses. Virology. 1999;256:15–21. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reimann K A, Li J T, Veazey R, Halloran M, Park I W, Karlsson G B, Sodroski J, Letvin N L. A chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus expressing a primary patient human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate env causes an AIDS-like disease after in vivo passage in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1996;70:6922–6928. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6922-6928.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richman D D. HIV chemotherapy. Nature. 2001;410:995–1001. doi: 10.1038/35073673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmitz J E, Kuroda M J, Santra S, Sasseville V G, Simon M A, Lifton M A, Racz P, Tenner-Racz K, Dalesandro M, Scallon B J, Ghrayeb J, Forman M A, Montefiori D C, Rieber E P, Letvin N L, Reimann K A. Control of viremia in simian immunodeficiency virus infection by CD8+ lymphocytes. Science. 1999;283:857–860. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5403.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmitz J E, Lifton M A, Reimann K A, Montefiori D C, Shen L, Racz P, Tenner-Racz K, Ollert M W, Forman M A, Gelman R S, Vogel C W, Letvin N L. Effect of complement consumption by cobra venom factor (CVF) on the course of primary infection with simian immunodeficiency virus in rhesus monkeys. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1999;15:195–202. doi: 10.1089/088922299311619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith S M, Holland B, Russo C, Dailey P J, Marx P A, Connor R I. Retrospective analysis of viral load and SIV antibody responses in rhesus macaques infected with pathogenic SIV: predictive value for disease progression. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1999;15:1691–1701. doi: 10.1089/088922299309739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Staprans S I, Dailey P J, Rosenthal A, Horton C, Grant R M, Lerche N, Feinberg M B. Simian immunodeficiency virus disease course is predicted by the extent of virus replication during primary infection. J Virol. 1999;73:4829–4839. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.4829-4839.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suryanarayana K, Wiltrout T A, Vasquez G M, Hirsch V M, Lifson J D. Plasma SIV RNA viral load determination by real-time quantification of product generation in reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1998;14:183–189. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watson A, Ranchalis J, Travis B, McClure J, Sutton W, Johnson P R, Hu S L, Haigwood N L. Plasma viremia in macaques infected with simian immunodeficiency virus: plasma viral load early in infection predicts survival. J Virol. 1997;71:284–290. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.284-290.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]