Abstract

Background

Angiogenesis is associated with tumour growth, infiltration, and metastasis. This study aimed to detect the mechanisms of angiogenesis-related genes (ARGs) in multiple myeloma (MM) and to construct a new prognostic model.

Methods

MM research foundation (MMRF)-CoMMpass cohort, GSE47552, GSE57317, and ARGs were sourced from public databases. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the tumour and control cohorts in GSE47552 were determined through differential expression analysis and were enriched with Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses. Weighted gene coexpression network analysis (WGCNA) was applied to derive modules linked to the ARG scores and obtain module genes in GSE47552. Differentially expressed ARGs (DE-ARGs) were selected for subsequent analyses by overlapping DEGs and module genes. Furthermore, prognostic genes were selected using univariate Cox and least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression analyses. Depending on the prognostic genes, a risk model was constructed, and risk scores were determined. Moreover, MM samples from MMRF-CoMMpass were sorted into high- and low-risk teams on account of the median risk score. Additionally, correlations among clinical characteristics, gene set variation analysis (GSVA), gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA), immune analysis, immunotherapy predictions and the mRNA‒miRNA‒lncRNA network were carried out.

Results

A total of 898 DEGs, 211 module genes, 24 DE-ARGs and three prognostic genes (AKAP12, C11orf80 and EMP1) were selected for this study. Enrichment analysis revealed that the DEGs were related to 86 GO terms, such as ‘cytoplasmic translation’, and 41 KEGG pathways, such as ‘small cell lung cancer’. A prognostic gene-based risk model was created in MMRF-CoMMpass and confirmed with the GSE57317 dataset. Moreover, a nomogram was established on the basis of independent prognostic factors that have proven to be good predictors. In addition, the immune cell infiltration results suggested that memory B cells were enriched in the high-risk group and that immature B cells were enriched in the low-risk group. Finally, the mRNA‒miRNA‒lncRNA network demonstrated that hsa-miR-508-5p was tightly associated with EMP1 and AKAP12. RT‒qPCR was used to validate the expression of the genes associated with prognosis.

Conclusion

A new prognostic model of MM associated with ARGs was created and validated, providing a new perspective for exploring the connection between ARGs and MM.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-024-13024-9.

Keywords: Multiple myeloma, Angiogenesis-related genes, Prognosis, Immune microenvironment, GEO

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant clonal plasma cell disease that originates in the bone marrow and is clinically characterized by an accumulation of clonal plasma cells in the bone marrow, which triggers the overproduction of nonfunctional intact immunoglobulins or immunoglobulin chains. As a haematological malignancy, MM accounts for 1.3% of all malignancies and 14% of haematological neoplasms [1]. The occurrence of MM is usually complicated by end-organ damage, which manifests itself as renal failure, anaemia, bone lesions, and hypercalcaemia. Although treatments for MM, such as proteasome inhibitors, immunomodulatory drugs, autologous stem cell transplantation, and cellular immunotherapy, have improved, MM is still incurable, with a 5-year survival rate of approximately 50% because of the drug-resistant and frequently relapsing nature of MM [2]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to search for potential prognostic genes in MM and to understand their effects on the prognosis of patients with MM to provide new ideas for the treatment of this torturous disease.

Angiogenesis is a multistep process triggered by multiple biological signals and can be regulated by a balance of growth and inhibitory factors in healthy tissues; when this balance is disrupted, too much or too little angiogenesis occurs, leading to a variety of diseases, including malignancies [3, 4]. Tumours need to establish new blood vessels to continue growing and therefore need to be stimulated by chemical signals from tumour cells to stimulate angiogenesis, which promotes tumour growth. In the absence of vascular support, tumours may undergo necrosis or even apoptosis. Angiogenesis is therefore one of the hallmarks of cancer and promotes rapid tumour progression, permits remote tumour spread, and provides tumour tissues with the oxygen and nutrients needed for metabolism [5–7]. Angiogenesis is one of the major contributors to tumour growth, infiltration, and metastasis [8]; however, the regulatory mechanisms of angiogenesis-related genes in MM are not well understood.

In this study, based on MM-related datasets in public databases, we performed bioinformatics assessments to explore angiogenesis-related biomarkers in MM and constructed a new prognostic assessment model to analyse the biological pathways associated with the resulting prognostic genes, as well as their relationships with clinical features, the immune microenvironment, and pharmacological treatments, with the aim of providing a new direction for prognostic treatments in MM.

Materials and methods

Data sources

The multiple myeloma research foundation (MMRF)-CoMMpass cohort, which included 843 MM samples with gene expression, clinical information and survival information, was retrieved from the MMRF database (https://research.themmrf.org) and treated as the training set. The GSE47552 (GPL6244) dataset, which contains 41 MM samples and 5 healthy control samples, was mined from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). The validation set GSE57317 (GPL570), which contained 55 MM samples with survival information, was also sourced from the GEO database. In addition, 36 angiogenesis-related genes (ARGs) were mined from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB, https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/).

Preprocessing and principal component analysis (PCA) of the dataset

We meticulously preprocessed three independent datasets, GSE47552, GSE57317 and MMRF, to ensure the consistency of the data and the accuracy of the analysis. First, the expression matrix and sample information were read, and the design matrix was constructed through the model.matrix function to clarify the sample grouping and lay the foundation for the subsequent statistical analysis. Subsequently, a linear model was fitted for each gene using the lmFit function within the limma package, and a comparison model was applied via contrasts.fit to compare the gene expression differences between different groups [9]. To further improve the reliability of statistical inference, we used the eBayes function for empirical Bayesian adjustment to reduce the false positive rate [10]. Finally, significantly differentially expressed genes were screened and extracted by the top Table function, and strict |log2FC| and adj. P value thresholds (adj. P < 0.05 and |log2FC| > 1) were set to ensure the significance of the selected genes.

To assess and visualize the batch effects among different datasets, we used the R packages ggplot2 (v. 3.4.3) and dplyr (v. 1.1.4) [11]for data processing and visualization. By extracting gene intersections and normalizing them across the three datasets, we ensured consistency in comparisons across datasets. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed using the prcom function from the stats package (v. 4.2.2) [12], an analysis designed to reduce the dimensionality of the data while revealing major patterns of variation in the data.

Identification and enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs)

DEGs between the tumour and control cohorts in GSE47552 were selected using the R language limma package (v. 3.52.0) [9], with adj. P < 0.05 and |log2FC| > 1. Moreover, Gene Ontology (GO), which includes biological process (BP), molecular function (MF) and cellular component (CC), and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses of the DEGs were performed using the clusterProfiler package (v. 4.2.2) [13] and the org.Hs.eg.db package (v. 3.14.0). The single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) algorithm of the GSVA package (v. 1.42.0) [14] was applied to compute the ARG scores in MM samples from GSE47552. All genes in the MM samples of GSE47552 were subsequently assigned to modules by weighted gene coexpression network analysis (WGCNA) (v. 1.71) [15]. Modules relevant to the ARG scores were confirmed as key modules. The differentially expressed ARGs (DE-ARGs) were subsequently obtained by overlapping the DEGs and module genes for subsequent analyses. GO, KEGG and correlation analyses were carried out on the DE-ARGs.

Construction and validation of the risk model

Univariate Cox regression and least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression analyses were performed using the glmnet package (v. 4.1-4) [16] to select prognostic genes related to the DE-ARGs. A risk model was subsequently constructed in accordance with the expression of prognostic genes and overall survival (OS) via LASSO. The risk scores were assessed using the formula below.

|

β and x indicate coefficients and gene expression, respectively. Moreover, the MM samples of MMRF-CoMMpass were sorted into high- and low-risk teams according to the median risk score. K‒M survival curves were generated using the survival package (v. 3.4-0) [17] for both risk groups. To further ensure the validity of the risk model, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed for 1, 2, and 3 years, and area under the curve (AUC) values were computed using survivalROC (v. 1.0.3) [18]. The risk model was validated with the GSE57317 dataset.

Relevance analysis of clinical characteristics and independent prognostic analysis

Correlations between risk scores and clinical characteristics (age, genders and stage) were analysed by correlation analysis. Survival differences were determined using the log-rank test. The risk scores and 3 clinical characteristics were subsequently included in the risk model for univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses. Independent prognostic factors were subsequently selected to construct a nomogram using rms (v. 6.3-0) [19]. The 1-, 2-, and 3-year survival rates were forecast based on total points (the higher the point, the lower the survival rate). The nomogram was constructed using calibration curves.

Gene set variation analysis (GSVA) and GSEA

GSVA was conducted using the GSVA package, with GO and KEGG as the background gene sets, and the results are presented as heatmaps. The interteam differences were subsequently analysed in DESeq2 (v. 1.34.0) [20], and the log2FC values obtained from the difference analysis were subsequently used as sorting criteria to perform GSEA.

Immune microenvironment analysis

The 28 immune cell scores were computed using ssGSEA. The Spearman correlation coefficients of the immune cell scores of the two risk groups in the MMRF-CoMMpass cohort were analysed by the Wilcoxon test. Correlation scatter plots of risk scores and immune cells with distinct differences between the two risk groups were also generated. The samples were classified into high- and low-abundance groups depending on their abundance and were analysed for survival.

Immunotherapy predictions and the molecular regulatory network

The analysis of immunotherapy efficacy was based on gene expression data from the MMRF-CoMMpass dataset. The Wilcoxon method was used to test differences in the expression levels of immune checkpoints in both risk groups and to calculate the correlations between risk score and immune checkpoint expression. Tumour Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion (TIDE), which is a computational framework for assessing the likelihood of tumor immune escape in gene expression profiles of tumor samples. The expression values of each gene in all samples are calculated as required by the official documentation on the TIDE website to obtain the average value for each gene. Using the average of all samples as a control, gene expression data from 843 normalized tumour samples were imported into TIDE (http://tide.dfci.harvard.edu/) to obtain tumour immune exclusion, tumour immune dysfunction, and TIDE scores of the samples and to analyse their relationships with risk scores further. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of 11 drugs (bortezomib, lenalidomide, cyclophosphamide, paclitaxel, cisplatin, bleomycin, docetaxel, gemcitabine, sorafenib, veliparib and vinblastine) were computed and compared between the high- and low-risk teams using the oncoPredict package (v. 0.1) [21]. Additionally, the DIANA-microT, miRanda and miRDB databases were selected to predict target miRNAs for prognostic genes using the R package multiMiR [22], and intersecting target miRNAs were selected for subsequent analysis. Target lncRNAs with clipExpNum > 4 were then sifted from the starBase database based on target miRNAs. Finally, prognostic genes, target miRNAs and target lncRNAs were integrated to construct an mRNA‒miRNA–lncRNA network.

Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT‒qPCR)

To further investigate the roles of prognostic genes in MM, the expression levels of prognostic genes were validated by RT‒qPCR. In this study, a total of 10 clinical bone marrow samples were obtained from normal individuals and patients with MM at the Department of Haematology, First People’s Hospital of Yunnan Province, China, including 5 control and 5 tumour samples. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of First People’s Hospital of Yunnan Province, China (approval number: KHLL2022-KY075).

Total RNA was extracted from the nucleated cells of the bone marrow using a protocol adapted from PBMC isolation procedures, followed by extraction with TRIzol reagent. Reverse transcription was performed using a SureScript First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit to obtain cDNAs. RT‒qPCR was performed as follows: 40 cycles of 95 °C for 1 min, 95 °C for 20 s, 55 °C for 20 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. GAPDH was used as the internal reference gene. The qPCR primers used are listed in Table 1. The relative expression levels of the prognostic genes were calculated by the 2-△△ct method.

Table 1.

RT‒qPCR primers

| Gene | Primer sequence |

|---|---|

| AKAP12 F | AAGCAAATGGGGACTCGGAC |

| AKAP12 R | AGCCTGCGAATGAAGGAGAC |

| C11orf80 F | GCACTGGCGGAGTTCCA |

| C11orf80 R | TCCTGCAGAAGCAACTCGAA |

| EMP1 F | GTGTGGGCTCTGTGAGTGAA |

| EMP1 R | AGAAGGGGCTGGAAGATTGC |

| GAPDH F | CGAAGGTGGAGTCAACGGATTT |

| GAPDH R | ATGGGTGGAATCATATTGGAAC |

Results

Identification and functional analysis of DEGs

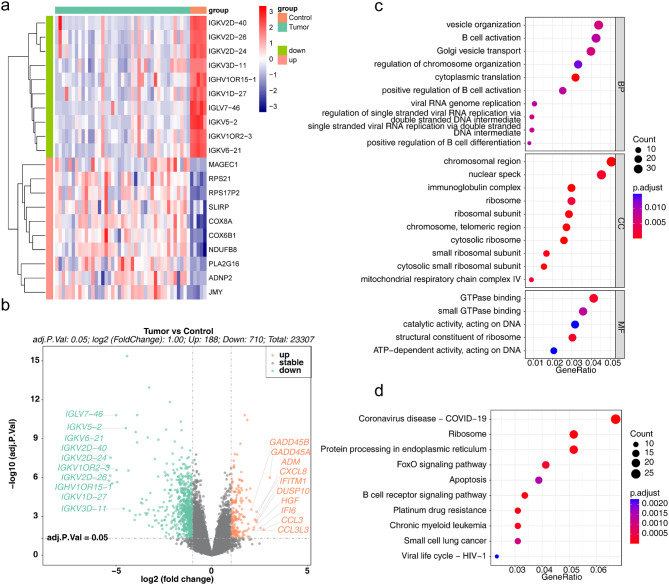

PCA analysis showed significant between-group differences among the three datasets, with no batch effects (Fig. S1). A total of 898 DEGs (188 upregulated and 710 downregulated) from the tumour and control cohorts were selected from the GSE47552 dataset (Fig. 1a and b). Functional enrichment analysis revealed that DEGs were related to 86 GO terms (Fig. 1c), including 47 BPs (e.g., ‘cytoplasmic translation’, ‘Golgi vesicle transport’ and ‘vesicle organization’), 34 CCs (e.g., ‘chromosomal region’, ‘nuclear speck’, ‘immunoglobulin complex’) and five MFs (e.g., ‘GTPase binding’, ‘small GTPase binding’, ‘catalytic activity, action on DNA’). In addition, 41 functional KEGG pathways (P.adj < 0.05), such as ‘small cell lung cancer’ (Fig. 1d), were enriched.

Fig. 1.

Identification and functional analysis of DEGs. (a) Heatmap of DEGs between the tumour and control cohorts in GSE47552. (b) Volcano plot of DEGs between the tumour and control cohorts in GSE47552. (c) GO enrichment results for DEGs. (d) KEGG enrichment results for DEGs. DEGs, differentially expressed genes; GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

Identification of module genes by WGCNA

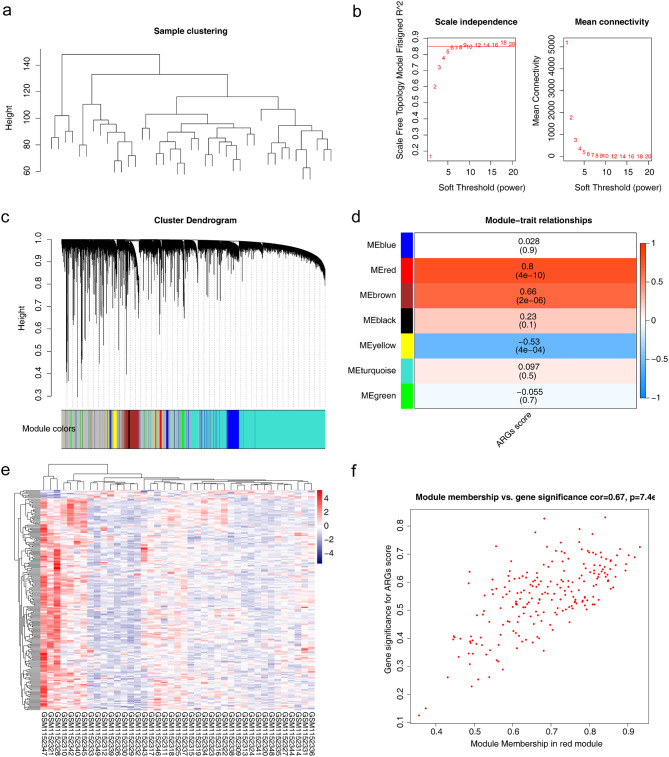

First, samples from GSE47552 were clustered to construct a clustering tree (Fig. 2a). A soft threshold of nine was subsequently set to structure a scale-free network, and the hierarchical clustering results are shown in Fig. 2b and c. Finally, seven modules were obtained, and the red module (Cor = 0.8, P < 0.05) was associated with ARG scores (Fig. 2d). The heatmap and scatter plot show the correlations of 211 module genes and the ARG scores of the MM samples, respectively (Fig. 2e and f).

Fig. 2.

Module genes from WGCNA. (a) Sample clustering tree for GSE47552. (b) Soft threshold screening. The threshold is 0.85, and the soft threshold is 9. (c) Cluster dendrogram. (d) Correlations between gene modules and ARG scores. (e) Heatmap showing the correlations between 211 module genes and the ARG scores of MM samples. (f) Scatter plot showing the correlations of the module membership in the red module and the gene significance for the ARG scores. WGCNA, weighted gene coexpression network analysis; ARGs, angiogenesis-related genes; MM, multiple myeloma

Acquisition and functional enrichment analysis of DE-ARGs

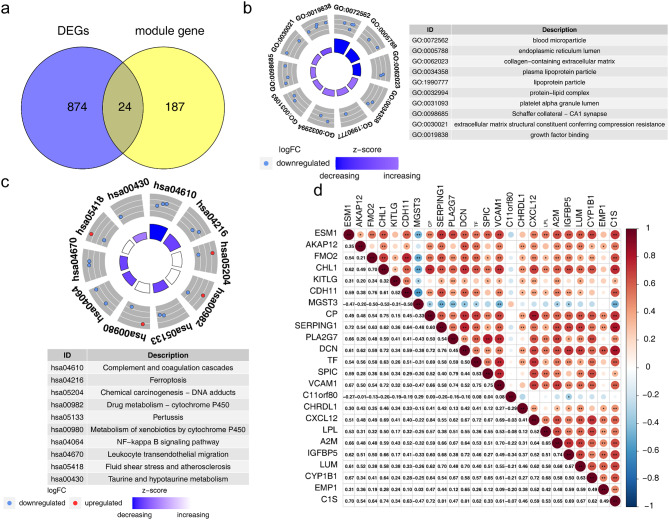

Overall, 24 DE-ARGs were obtained by overlapping DEGs and module genes (Fig. 3a). Moreover, the DE-ARGs were markedly related (P.adj < 0.05) to 38 GO terms, such as ‘humoral immune response’, ‘blood particles’ and ‘growth factor binding’ (Fig. 3b), and 10 KEGG pathways, such as ‘complement and coagulation cascades’ (Fig. 3c). The results of the correlation analysis among DE-ARGs revealed that CP had the strongest positive correlation with CXCL12 (Cor = 0.84, P < 0.05) and that CDH11 had the strongest negative correlation with MGST3 (Cor = -0.58, P < 0.05) (Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3.

Functions for DE-ARGs. (a) DE-ARGs identified by overlapping DEGs and module genes. (b) GO results for DE-ARGs. (c) KEGG results for DE-ARGs. (d) Correlations among the DE-ARGs. DEGs, differentially expressed genes; DE-ARGs, differentially expressed ARGs; GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

Risk model prediction

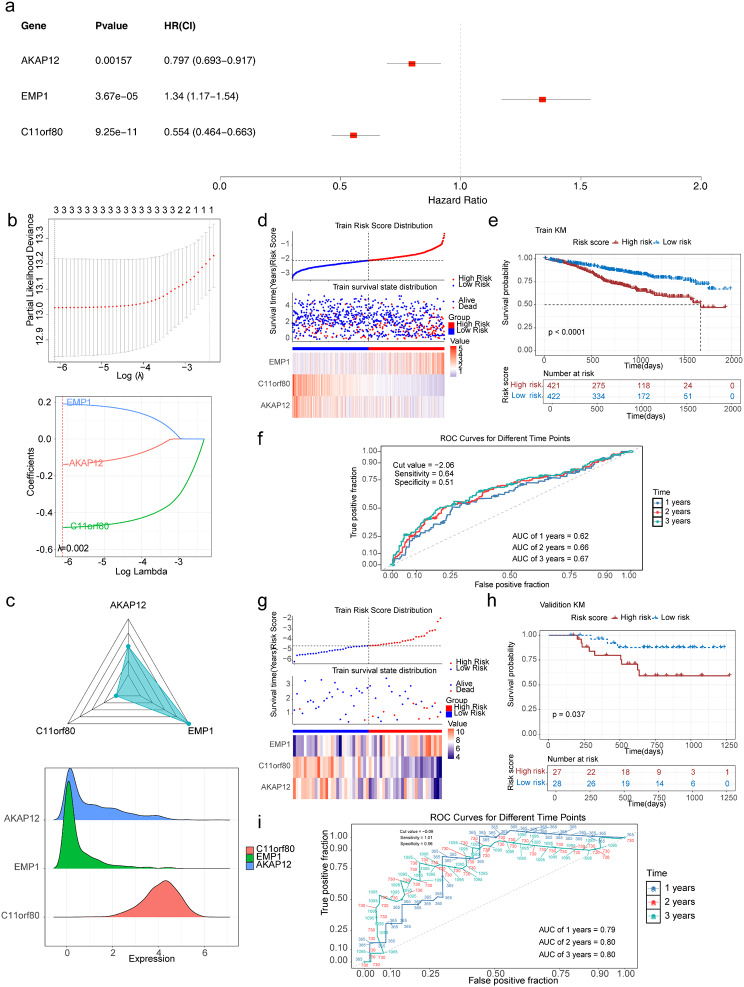

A total of three prognostic genes (AKAP12, C11orf80 and EMP1) were identified by univariate Cox regression analysis (Fig. 4a) and LASSO based on 24 DE-ARGs (Fig. 4b). A risk model was subsequently constructed according to the expression profiles of the three prognostic genes, and risk scores were computed (Fig. 4c). Risk score = − 0.139×AKAP12 + 0.191×EMP1-0.481×C11orf80. The risk curves and gene expression data of both risk groups associated with MMRF-CoMMpass were plotted based on the risk scores (Fig. 4d). K‒M curves for the two risk groups revealed that the survival of patients with MM was markedly significant (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4e). The AUC values all exceeded 0.6 at 1, 2, and 3 years, suggesting that these three prognostic genes could validly predict survival status (Fig. 4f). Moreover, the risk model was validated with the GSE57317 dataset. The distributions of the risk scores and survival status and a heatmap of prognostic gene expression data were constructed for both risk groups (Fig. 4g). K‒M curves revealed that patients with MM in the low-risk group had a greater survival rate than those in the high-risk group did, which was consistent with the training set (Fig. 4h). The AUC of the validation set exceeded 0.7 at years 1, 2 and 3, suggesting that the risk model was able to perform fairly well in the prediction (Fig. 4i).

Fig. 4.

Construction and validation of the risk model. (a) Univariate Cox regression forest plot. (b) LASSO model for the three prognostic genes (AKAP12, C11orf80 and EMP1). The horizontal coordinate is log (λ), and the vertical coordinate is the model error rate (up) and coefficient (down). (c) Prognostic gene expression in MM samples. (d) Risk curve, scatter plot and heatmap of prognostic gene expression for the high- and low-risk groups in MMRF-CoMMpass. (e) K–M curve for both risk groups in MMRF-CoMMpass. (f) ROC curves for both risk groups in MMRF-CoMMpass. (g) Risk curve, scatter plot and heatmap of prognostic gene expression for the high- and low-risk groups in the GSE57317 dataset. (h) K–M curves for both risk groups in the GSE57317 dataset. (i) ROC curves for both risk groups in the GSE57317 dataset. MM, multiple myeloma; K–M, Kaplan–Meier; ROC, receiver operating characteristic

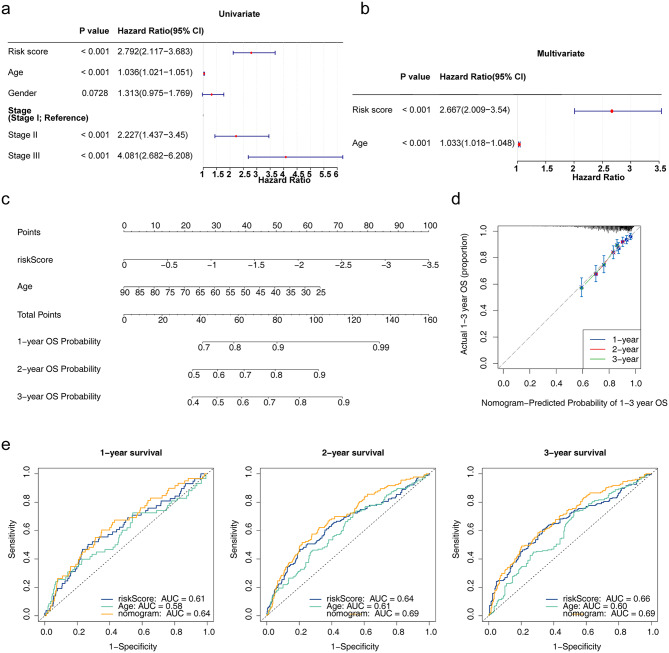

Correlation analysis of risk scores and clinical characteristics and construction of an independent prognostic model

Correlation analysis revealed major differences in the three clinical characteristics and risk scores across stages (Fig. S2). There were marked differences in the survival status of the samples in terms of age, sex and stage III disease (Fig. S3). Furthermore, risk score and age were identified as independent prognostic factors using univariate and PH hypothesis tests and multivariate Cox regression to construct a nomogram (Fig. 5a, b and c). Calibration curves and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves revealed that the nomogram had favourable prediction accuracy (Fig. 5d and e).

Fig. 5.

Prognostic nomogram model. (a) Univariate Cox regression forest plot. (b) Multivariate Cox regression forest plot. (c) Nomogram model. (d) Calibration curve. (e) Receiver operating characteristic curves for 1-, 2- and 3-year survival

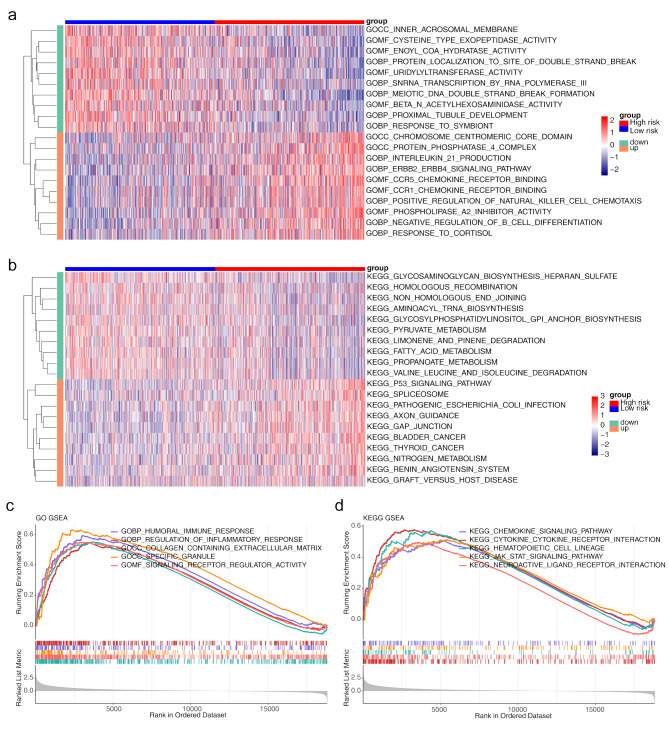

Functional enrichment by GSVA and GSEA

In the training set, GSVA enrichment revealed the top 10 pathways with the most markedly up- and downregulated genes between both risk groups, with GO and KEGG as background gene sets, respectively (Fig. 6a and b). There were 6,228 differential pathways (4,575 upregulated and 1,653 downregulated) in the GO analysis, e.g., ‘inner acrosomal membrane’, and 114 differential pathways (73 upregulated and 41 downregulated) in the KEGG analysis, e.g., ‘P53 signalling pathway’. GSEA revealed that the enriched genes were enriched mainly in ‘collagen containing extracellular matrix’, ‘signalling receptor regulation activity’, and ‘specific granule’, among others, in the GO analysis (Fig. 6c) and in ‘cytokine receptor interaction’, among others, in the KEGG analysis (Fig. 6d).

Fig. 6.

Gene set variation analysis (GSVA) and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA). (a) Heatmap of the results of GSVA analysis of the GO gene set. (b) Heatmap of the results of GSVA analysis of the KEGG gene set. (c) GSEA results for the GO gene set. (d) GSEA results for the KEGG gene set. GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

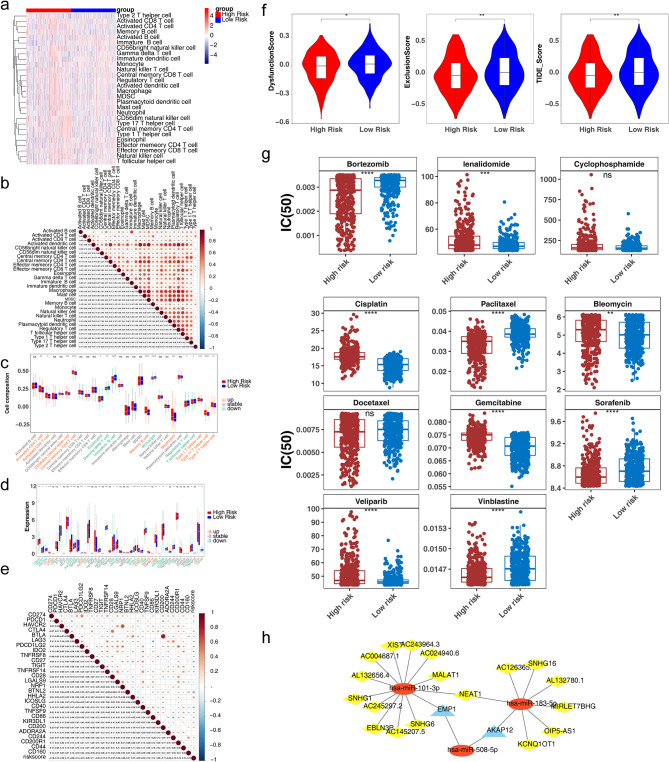

Immune microenvironment and drug sensitivity in the two risk groups and upstream regulatory mechanisms of prognostic genes

The results of immune cell scoring revealed that the number of memory B cells was greater in high-risk group and that immature B cells scored higher in low-risk group (Fig. 7a). The immune cells with significant correlations were all positive, and activated dendritic cells and macrophages were the most strongly positively correlated with each other (cor = 0.84) (Fig. 7b). Moreover, a total of 15 immune cells differed notably between the two risk groups (Fig. 7c). Correlation analysis revealed that risk scores were most positively linked to memory B cells and most negatively linked to immature B cells (Fig. S4). K‒M curves of the high- and low-abundance groups revealed that both groups of activated CD4 T cells, activated CD8 T cells, immature B cells, memory B cells, and type 2 T helper cells differed markedly in survival (Fig. S5). Immune checkpoint analysis revealed marked differences in the expression levels of 28 immune checkpoints (e.g., CD274, PDCD1, HAVCR2) between the two risk groups (Fig. 7d). The risk scores were most strongly positively correlated with HHLA2 and most strongly negatively correlated with BTNL2 (Fig. 7e). The results of TIDE analysis in the two risk groups revealed marked differences in tumour immune exclusion, dysfunction, and TIDE scores (Fig. 7f). Drug sensitivity analysis revealed that the IC50 values for bortezomib, paclitaxel, sorafenib, and vinblastine were lower in the high-risk group than in the low-risk group, indicating that patients with MM in the high-risk group were more sensitive to these four drugs, whereas patients in the low-risk group were more sensitive to lenalidomide, cisplatin, bleomycin, gemcitabine, and veliparib (Fig. 7g). Three target miRNAs were obtained by intersecting the predicted target miRNAs from three databases (Fig. S6). A subsequent mRNA‒miRNA‒lncRNA network incorporating two prognostic genes (AKAP12 and EMP1), three targeted miRNAs and 18 targeted lncRNAs was designed (Fig. 7h).

Fig. 7.

Regulatory mechanisms of the immune microenvironment, drug sensitivity and prognostic genes. (a) Heatmap of ssGSEA scores of immune cells in high- and low-risk groups. (b) Correlations between scores of immune cells. (c) Differences in the scores of immune cells in the high- and low-risk groups. (d) Differences in immune checkpoints between the high- and low-risk groups. (e) Correlations between the risk score and the expression of immune checkpoint genes. (f) Box plot of the risk score versus tumour immune exclusion, dysfunction, and TIDE scores. (g) IC50 values of drugs in the high- and low-risk groups. (h) The mRNA‒miRNA–lncRNA network. TIDE, tumour immune dysfunction and exclusion

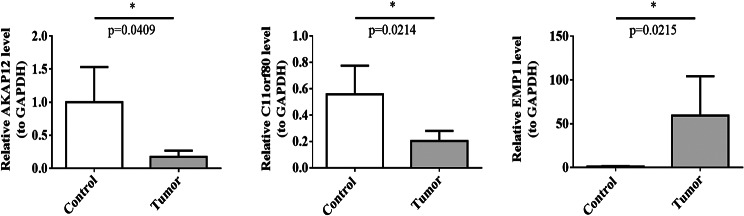

Validation of prognostic genes by RT‒qPCR

The RT‒qPCR results revealed that the expression levels of AKAP12 and C11orf80 in the MM group were significantly lower than those in the control group, whereas the expression level of EMP1 in the MM group was significantly greater than that in the control group (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Expression levels of prognostic genes. AKAP12, C11orf80 and EMP1. *P < 0.05

Discussion

MM is a haematologic malignancy that generally leads to kidney failure, anaemia, bone lesions, and hypercalcaemia. Angiogenesis [23], one of the major contributors to tumour growth [24], infiltration [25] and metastasis [26], is closely linked to cancer development [27]. Exploring the regulatory mechanisms of angiogenesis-related genes in MM is important. In our study, the use of bioinformatics confirmed that our risk score was significantly associated with MM prognosis, immune cell infiltration, immune checkpoint expression, and drug sensitivity. We then used clinical samples to detect the expression levels of the three genes identified in the analyses, and the results were consistent with those of bioinformatics, which confirmed the validity of the risk score and its utility as a prognostic marker for MM.

Differential expression analysis of myeloma samples and normal samples revealed that there were significantly more downregulated genes than upregulated genes in the tumour samples. This phenomenon may be attributed to the widespread inactivation of tumour suppressor genes in malignant tumours such as multiple myeloma; these genes are responsible for negatively regulating key processes such as cell growth, division, and apoptosis in the normal state, and their inactivation or downregulation results in uncontrolled cell proliferation and blocked apoptotic mechanisms, which in turn promote the development of tumours [28]. In addition, myeloma cells not only undergo genetic and epigenetic changes but also interact closely with their complex microenvironment (involving stromal cells, immune cells, and a variety of cytokines), and this interaction further influences the gene expression pattern of myeloma cells [29, 30]. To support tumour growth, the activation of specific signalling pathways may preferentially trigger the downregulation of some genes.

A-kinase anchoring protein (AKAP12), an angiogenesis inhibitor gene, is a scaffolding protein that anchors multiple signalling proteins to the plasma membrane. These signalling proteins include src family kinases, cyclins, protein kinase A, protein kinase C, protein phosphatase 2B, and calmodulin, which regulate their respective signalling pathways [31]. AKAP12 been studied in a number of tumours; for example, it is viewed as a component of plasma ovarian cancer risk models [32]. In prostate cancer (PCa), increased expression of AKAP12 inhibits PCa metastasis [33]. Positive regulation of AKAP12 inhibits the progression of triple-negative breast cancer [34]. Ke Li et al. suggested that AKAP12 may be an important therapeutic target for blocking colorectal cancer progression [35]. Hai Wang et al. reported that AKAP12 expression was downregulated in bladder cancer tumour tissues [36]. AKAP12 has also been studied in haematologic malignancies, and Yuye Shi et al. reported that the AKAP12 risk score was associated with a high incidence of trisomy 12q; thus, AKAP12 is an independent prognostic factor for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia [37]. Similarly, in our study, for the first time, AKAP12 was found to be associated with the prognosis of patients with MM and could be used as a biomarker for MM, but the specific merits still need to be further explored.

Few studies on chromosome 11 open reading frame 80 (C11ORF80) exist, and its function has not been clearly reported. Nan Li et al. investigated the relationships between signalling pathways and functional pathways in cervical cancer by gene set enrichment analysis. C11orf80 was detected as one of the key genes for the construction of the 6-gene signature, and this prognostic signature was significantly correlated with the overall survival rate [38].

Epithelial membrane protein 1 (EMP1) is expressed primarily in the epithelial cells of many tissues and organs. This gene is involved in cell proliferation, apoptosis, cell adhesion, and cell signalling, and it is abnormally expressed in a variety of tumours and may be associated with tumorigenesis and progression [39–41]. EMP1 was found to be significantly associated with the prognosis of patients with breast cancer by Kang Yao et al. [42]. Saniya Arfin et al. suggested that EMP1 plays a key role in the molecular interactions that drive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma tumorigenesis [43]. Xiaoxue Zhang et al. conducted a risk modelling study on EMP1 as a prognostic gene for ovarian cancer [44]. More importantly, in bladder cancer, EMP1 was found to have a significant tumour-promoting effect [45], which is complementary to our findings. Our study revealed that EMP1 tends to promote MM progression. In combination with the previously mentioned studies on AKAP12 inhibition of other tumours, this finding is also consistent with our study, validating, to some extent, the reliability of the modelling in our study.

The results of immune cell infiltration in our study revealed that memory B cells scored higher in the high-risk group, whereas immature B cells scored higher in the low-risk group. The immune cells with significant correlations were all positively correlated, with the most pronounced positive correlations for activated dendritic cells and macrophages. Merz, Maximilian et al. reported that next-generation flow (NGF) resulted in significant immunosuppression in relapsed/refractory MM (RRMM) compared with newly diagnosed MM (NDMM), as evidenced by fewer myeloid dendritic cells, unswitched memory B cells, Th9 cells, and CD8 effector memory T cells but more natural killer and regulatory T cells [46]. This finding is consistent with our findings to some extent and may shed light on the relationship between MM prognosis and immune cells. Bo Lin et al. revealed that EMP1 was positively correlated with the infiltration levels of CD8 + T cells, neutrophils and macrophages and with prognosis in patients with bladder cancer [47]. In summary, key genes are associated with immune cell infiltration and poor prognosis in a variety of tumours. Taken together, the results of our study suggest that, in MM, these three prognostic genes may influence the development of disease in patients by affecting the expression of memory B cells and immature B cells.

While our findings are promising, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the conclusions of this study may be limited by individual patient differences, including the potential impacts of multifaceted factors such as age, sex, disease stage, and treatment regimen. Second, focusing on the infiltration of only a few types of immune cells may make it difficult to fully capture the complexity and dynamics of the tumour immune microenvironment, thus limiting the comprehensiveness and depth of the conclusions. Furthermore, the potential interference of conventional treatments, such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy, on the immune balance in the tumour microenvironment is a variable that should not be ignored when evaluating the relationship between immune cell infiltration and prognosis, and its influence needs to be controlled or excluded when designing studies. Our study was designed to investigate MM but future studies could explore more inclusive approaches that cover all stages of myeloma to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the disease. For example, in research, we can use the MMRF dataset to develop transformation rules that adjust RT-qPCR expression values to a distribution that matches that dataset. Risk scores are more accurately predicted from RT-qPCR values by employing complex models such as deep neural networks [48]. This not only improves the accuracy of the predictions, but also enhances the usefulness of the model in a variety of clinical settings.

To more accurately reveal the complex relationship between immune cell infiltration and MM prognosis and explore potential therapeutic targets and mechanisms, there is an urgent need for larger, multicentre, prospective studies. These studies should aim to incorporate more potential key biomarkers and genetic variants to construct a more comprehensive immune microenvironment. Moreover, the impact of therapeutic interventions on the immune microenvironment should be effectively controlled or adjusted through finely designed study protocols to ensure the reliability and validity of the study results. Through these efforts, we expect to open new avenues for myeloma treatment and provide more precise and effective therapeutic strategies.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study has made a pivotal contribution to advancing our understanding of multiple myeloma (MM) by focusing on three angiogenesis-related prognostic genes. By applying bioinformatics to MM-related datasets from public databases, we identified angiogenesis biomarkers and constructed a prognostic model that delves into the biological pathways linked to these genes and their clinical feature correlations, immune microenvironment interactions, and pharmacological treatment implications. This comprehensive approach paves a new path for prognostic treatment strategies in MM, inspiring new research directions and clinical interventions.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the MMRF, GEO, MSigDB and other databases for providing invaluable data for statistical analyses.

Abbreviations

- MM

Multiple myeloma

- MMRF

Multiple myeloma research foundation

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- ARGs

Angiogenesis-related genes

- MSigDB

Molecular Signatures Database

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- GO

Gene Ontology

- BP

Biological Process

- MF

Molecular Functions

- CC

Cellular Components

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- ssGSEA

Single-sample gene set enrichment analysis

- WGCNA

Weighted gene coexpression network analysis

- DE-ARGs

Differentially expressed ARGs

- LASSO

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- OS

Overall survival

- K‒M

Kaplan‒Meier

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- AUC

Area under the curve

- GSVA

Gene set variation analysis

- TIDE

Tumour Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion

- IC50 50%

Inhibitory concentration

- RT‒qPCR

Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Author contributions

Rui Hu and Fengyu Chen contributed equally to this work. RH proposed the idea, participated in drafting and correcting the manuscript, and provided part of the funding support. FC drafted the manuscript and created the figures and tables. XY, ZL, YL and SF reviewed and tallied the data. JL and HL corrected the data. CS and ZL performed the calculation of the results and participated in the proposal of the study. XG was the chief architect for conducting the project and provided the majority of the grant funding. All the authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82360041), the Yunnan Health Training Project of High-level Talents (NO. D-2018018), the Yunnan Applied Basic Research Projects–Joint Fund for Applied Basic Research of Kunming Medical University, the Yunnan Provincial Department of Science and Technology [No. 2018FE001 (-113)], the Open Project of Yunnan Blood Clinical Medical Center (2022LCZXKF-XY11, 2021LCZXXF-XY04, 2021LCZXXF-XY05, 2020LCZXKF-XY02), and the 920th Hospital of PLA Joint Logistics Support Force Science and Technology Program Youth Project (2023YGY2).

Data availability

All the data generated or analysed in this study are included in this article. The datasets generated and/or analysed in this study are available online (MMRF database, https://research.themmrf.org; GEO database, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/; and MSigDB, https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of the First People’s Hospital of Yunnan Province, China (approval number: KHLL2022-KY075). All patients signed an informed consent form.

Consent for publication

All authors approved the publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original version of this article was revised: Fig. 6 was a duplicate of Fig. 5. This has been corrected.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rui Hu and Fengyu Chen contributed equally to this work.

Change history

12/18/2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1186/s12885-024-13349-5

Contributor Information

Xuezhong Gu, Email: gxz76@126.com.

Zhixiang Lu, Email: lzx70822@163.com.

References

- 1.Huang J, Chan SC, Lok V, Zhang L, Lucero-Prisno DE 3rd, Xu W, et al. The epidemiological landscape of multiple myeloma: a global cancer registry estimate of disease burden, risk factors, and temporal trends. Lancet Haematol. 2022;9(9):e670–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.van de Donk N, Pawlyn C, Yong KL. Multiple myeloma. Lancet (London England). 2021;397(10272):410–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stapor P, Wang X, Goveia J, Moens S, Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis revisited - role and therapeutic potential of targeting endothelial metabolism. J Cell Sci. 2014;127(Pt 20):4331–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Méndez-Ferrer S, Bonnet D, Steensma DP, Hasserjian RP, Ghobrial IM, Gribben JG, et al. Bone marrow niches in haematological malignancies. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20(5):285–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zuazo-Gaztelu I, Casanovas O. Unraveling the role of Angiogenesis in Cancer ecosystems. Front Oncol. 2018;8:248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dudley AC, Griffioen AW. Pathological angiogenesis: mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Angiogenesis. 2023;26(3):313–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karki R, Kanneganti TD. Diverging inflammasome signals in tumorigenesis and potential targeting. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019;19(4):197–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quan L, Ohgaki R, Hara S, Okuda S, Wei L, Okanishi H, et al. Amino acid transporter LAT1 in tumor-associated vascular endothelium promotes angiogenesis by regulating cell proliferation and VEGF-A-dependent mTORC1 activation. J Experimental Clin cancer Research: CR. 2020;39(1):266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, et al. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(7):e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phipson B, Lee S, Majewski IJ, Alexander WS, Smyth GK. Robust hyperparameter estimation protects against hypervariable genes and improves power to detect differential expression. Ann Appl Stat. 2016;10(2):946–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wickham HFR, Henry L, Müller K, Vaughan D, Dplyr. A grammar of data manipulation. R package version 1.1.4 2023 [ https://dplyr.tidyverse.org

- 12.R Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; October, 2022.

- 13.Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, He QY. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS. 2012;16(5):284–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hänzelmann S, Castelo R, Guinney J. GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y, Lu F, Yin Y. Applying logistic LASSO regression for the diagnosis of atypical Crohn’s disease. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):11340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramsay IS, Ma S, Fisher M, Loewy RL, Ragland JD, Niendam T, et al. Model selection and prediction of outcomes in recent onset schizophrenia patients who undergo cognitive training. Schizophrenia Res Cognition. 2018;11:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heagerty PJ, Lumley T, Pepe MS. Time-dependent ROC curves for censored survival data and a diagnostic marker. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):337–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sachs MC. plotROC: A tool for plotting ROC Curves. J Stat Softw. 2017;79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of Fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maeser D, Gruener RF, Huang RS. oncoPredict: an R package for predicting in vivo or cancer patient drug response and biomarkers from cell line screening data. Brief Bioinform. 2021;22(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Ru Y, Kechris KJ, Tabakoff B, Hoffman P, Radcliffe RA, Bowler R, et al. The multiMiR R package and database: integration of microRNA-target interactions along with their disease and drug associations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(17):e133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuchet P, Valette X. Radiation pneumonitis and chemotherapy in a patient with multiple myeloma. Lancet (London England). 2021;397(10283):1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sathiyanadan K, Alonso F, Domingos-Pereira S, Santoro T, Hamard L, Cesson V et al. Targeting endothelial Connexin37 reduces angiogenesis and decreases tumor growth. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Kandalaft LE, Dangaj Laniti D, Coukos G. Immunobiology of high-grade serous ovarian cancer: lessons for clinical translation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022;22(11):640–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Picon-Ruiz M, Morata-Tarifa C, Valle-Goffin JJ, Friedman ER, Slingerland JM. Obesity and adverse breast cancer risk and outcome: mechanistic insights and strategies for intervention. Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(5):378–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeng P, Wang F, Long X, Cao Y, Wen F, Li J, et al. CPEB2 enhances cell growth and angiogenesis by upregulating ARPC5 mRNA stability in multiple myeloma. J Orthop Surg Res. 2023;18(1):384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rizq O, Mimura N, Oshima M, Momose S, Takayama N, Itokawa N, et al. UTX inactivation in germinal center B cells promotes the development of multiple myeloma with extramedullary disease. Leukemia. 2023;37(9):1895–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Röllig C, Knop S, Bornhäuser M. Multiple myeloma. Lancet (London England). 2015;385(9983):2197–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allegra A, Di Gioacchino M, Tonacci A, Petrarca C, Musolino C, Gangemi S. Multiple myeloma cell-derived exosomes: implications on Tumorigenesis, diagnosis, prognosis and therapeutic strategies. Cells. 2021;10(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Turtoi A, Mottet D, Matheus N, Dumont B, Peixoto P, Hennequière V et al. Correction: the angiogenesis suppressor gene AKAP12 is under the epigenetic control of HDAC7 in endothelial cells. Angiogenesis. 2024;27(1):121-2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Yang X, Zheng M, Ning Y, Sun J, Yu Y, Zhang S. Prognostic risk factors of serous ovarian carcinoma based on mesenchymal stem cell phenotype and guidance for therapeutic efficacy. J Translational Med. 2023;21(1):456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang C, Wang S, Chao F, Jia G, Ye X, Han D, et al. The short inverted repeats-induced circEXOC6B inhibits prostate cancer metastasis by enhancing the binding of RBMS1 and HuR. Mol Therapy: J Am Soc Gene Therapy. 2023;31(6):1705–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Z, Gong X, Cheng C, Fu Y, Wu W, Luo Z. Circ_0001777 affects triple-negative breast Cancer Progression through the miR-95-3p/AKAP12 Axis. Clin Breast Cancer. 2023;23(2):143–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li K, Wu X, Li Y, Hu TT, Wang W, Gonzalez FJ, et al. AKAP12 promotes cancer stem cell-like phenotypes and activates STAT3 in colorectal cancer. Clin Translational Oncology: Official Publication Federation Span Oncol Soc Natl Cancer Inst Mexico. 2023;25(11):3263–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang H, Gao L, Chen Y, Zhang L, Bai Y, Zhao C et al. Identification of hub genes in bladder transitional cell carcinoma through ceRNA network construction integrated with gene network analysis. J Cell Mol Med. 2024;28(5):e17979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Shi Y, Xu X, He Z, Tao H, Chen Y, Zhang L, et al. AKAP12 and IGFBP4 are prognostic factors for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Acta Haematol. 2023;146(6):473–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li N, Yu K, Lin Z, Zeng D. Identifying a cervical cancer survival signature based on mRNA expression and genome-wide copy number variations. Exp Biol Med (Maywood NJ). 2022;247(3):207–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li X, Yan L, Xue H. Serum epithelial membrane protein 1 serves as a feasible biomarker in extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Int J Biol Mark. 2021;36(3):33–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miao L, Jiang Z, Wang J, Yang N, Qi Q, Zhou W, et al. Epithelial membrane protein 1 promotes glioblastoma progression through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Oncol Rep. 2019;42(2):605–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen X, Lv X, Han M, Hu Y, Zheng W, Xue H, et al. EMP1 as a potential biomarker in liver fibrosis: a Bioinformatics Analysis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2023;2023:2479192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yao K, Xiaojun Z, Tingxiao Z, Shiyao L, Lichen J, Wei Z, et al. Multidimensional analysis to elucidate the possible mechanism of bone metastasis in breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2023;23(1):1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arfin S, Kumar D, Lomagno A, Mauri PL, Di Silvestre D. Differentially expressed genes, miRNAs and network models: a strategy to shed light on molecular interactions driving HNSCC tumorigenesis. Cancers. 2023;15(17). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Zhang X, Han L, Zhang H, Niu Y, Liang R. Identification of potential key genes of TGF-beta signaling associated with the immune response and prognosis of ovarian cancer based on bioinformatics analysis. Heliyon. 2023;9(8):e19208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou T, Chen H, Wang Y, Wen S, Dao P, Chen M. Key molecules in bladder Cancer affect patient prognosis and immunotherapy efficacy: further exploration for CNTN1 and EMP1. JCO Precision Oncol. 2023;7:e2200630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Merz M, Hu Q, Merz AMA, Wang J, Hutson N, Rondeau C, et al. Spatiotemporal assessment of immunogenomic heterogeneity in multiple myeloma. Blood Adv. 2023;7(5):718–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin B, Zhang T, Ye X, Yang H. High expression of EMP1 predicts a poor prognosis and correlates with immune infiltrates in bladder urothelial carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2020;20(3):2840–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chadaga K, Prabhu S, Bhat V, Sampathila N, Umakanth S, Chadaga R. Artificial intelligence for diagnosis of mild-moderate COVID-19 using haematological markers. Ann Med. 2023;55(1):2233541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data generated or analysed in this study are included in this article. The datasets generated and/or analysed in this study are available online (MMRF database, https://research.themmrf.org; GEO database, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/; and MSigDB, https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/).