Abstract

Background

Massive irreparable rotator cuff tears can cause significant shoulder pain and disability. Treatment options include physiotherapy or surgery, with a lack of research comparing treatment options. For physiotherapy there is uncertainty about which patients will have a successful or unsuccessful response to treatment and a lack of consensus on what constitutes the best physiotherapy programme. With these significant gaps in the research, it is challenging for clinicians seeing patients with massive irreparable rotator cuff tears to advise on what is their best treatment pathway.

Methods

A three round Delphi study was conducted with expert shoulder physiotherapists and orthopaedic surgeons to gain consensus on the important factors associated with response to physiotherapy in this patient population. Round 1 was an information-gathering round to identify predictors of response to physiotherapy in patients with massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. Rounds 2 and 3 were consensus-seeking rounds on the importance and modifiability of the predictors. Consensus criteria were determined a priori using median, interquartile range, percentage agreement and Kendall’s Coefficient of Concordance.

Results

Participants were recruited April–October, 2023. 88 experts participated in Round 1 and of these, 70 completed Round 3 (79.54%). In Round 1, content analysis of 344 statements identified 45 predictors. In Round 2, 29 predictors reached consensus as important and 2 additional predictors were identified. In Round 3, of the 31 predictors from Round 2, 22 reached consensus as important and 12 of these reached consensus as modifiable by physiotherapists. Both patient factors and clinician factors from a broad range of domains reached consensus: biomechanical, psychological, social, co-morbidities, communication / healthcare interactions and pain.

Conclusions

The results of this Delphi study suggest that clinicians assessing patients with massive irreparable rotator cuff tears should assess across all these domains and target the modifiable factors with interventions. Particular emphasis should be placed on optimising modifiable clinician factors including therapeutic alliance, comprehensive explanation of the condition and collaborative and realistic goal-setting. These in turn may influence modifiable patient factors including patient expectations, engagement with the physiotherapy programme, motivation and self-efficacy thus creating the ideal environment to intervene on a biomechanical level with exercises.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12891-024-07872-6.

Keywords: Physiotherapy, Physical therapy, Rehabilitation, Massive irreparable rotator cuff tears, Delphi study, Predictors, Prognosis

Background

One of the most challenging issues for clinicians who see patients with shoulder pain is to advise on the most appropriate treatment pathway for patients with massive irreparable rotator cuff tears (MIRCT). MIRCT is defined as complete tears of two or more tendons of the rotator cuff that cannot be repaired surgically [1]. Surgical options include partial rotator cuff repair, arthroscopic debridement, subacromial balloon spacers, superior capsule reconstruction, tendon transfer procedures and reverse total shoulder arthroplasty [2]. Non-surgical options include physiotherapy and corticosteroid injection [3]. Clinically, MIRCT is often associated with significant pain and disability. Whilst some patients can be pain-free and have acceptable function, many experience pain and weakness in the shoulder and have pain and difficulty when raising the affected arm above shoulder height or in some cases above 45º [3, 4]. This can cause difficulty with basic everyday activities such as washing, dressing, housework, cooking, overhead activities, work and can also cause sleep disturbance and have a profoundly negative impact on quality of life [5].

Clinicians face several challenges in selecting the best treatment. The first challenge as identified in our previous review [6] is that there are no high quality randomised controlled trials comparing treatment approaches and therefore no clarity on what intervention is superior [7]. Secondly, there are no appropriately designed prospective prognostic studies to identify factors that are associated with successful or unsuccessful outcomes from the different treatment approaches [6]. With this lack of clear research evidence to guide clinical decision-making, patients can be offered treatments based on other factors such as the clinician’s experience or personal preference, the cost of the treatment, the geographical location or healthcare setting [8]. Variability in funding models for surgical and physiotherapy interventions across different countries and healthcare systems may also influence clinical decision-making. A stepped care model, starting with a six-month trial of physiotherapy, has been suggested due to the invasive nature, higher complication rates, and costs associated with surgical interventions [3, 9].

This leads us to the third challenge. Our recent review of the literature identified that outcomes for patients undergoing physiotherapy for MIRCT are highly variable [6]. Even studies with almost identical treatment approaches and similar aged patients demonstrated very different results. For example, one prospective case series evaluated the response of patients (n = 17) with MIRCT to an anterior deltoid re-education programme [10]. The authors demonstrated a success rate of 82% at nine months. A subsequent case series (n = 30) with similar methodology, demonstrated a success rate of only 40% at two years [11]. It is not clear why there were dramatically different outcomes in these two similar studies. One possibility is that although the participants were similar in terms of age, symptoms and the physiotherapy intervention they received, that there were other differences in the baseline characteristics of the participants that were not explored, identified or reported.

The fourth challenge is that there is uncertainty about which patients with MIRCT are likely to improve with physiotherapy. Several studies have attempted to identify factors which may be associated with a successful or unsuccessful response to rehabilitation. These studies identified several factors as possibly being related to whether patients have a successful outcome. Range of motion of less than 50º flexion [11] a tear of subscapularis [12], lack of teres minor hypertrophy [13], glenohumeral arthritis, passive restriction of movement and weakness of external rotation or abduction strength [14] are all biomechanical factors that may be related to an unsuccessful response to physiotherapy. However, because these factors were investigated in studies that do not align with the PROGRESS guidelines for prognostic studies [15], it is difficult to ascertain whether these factors are truly predictive of response to physiotherapy. There is a strong emphasis in the literature on these biomechanical factors as possible predictors of treatment response.

It is not clear if orthopaedic surgeons and physiotherapists have similar perspectives and opinions on which factors are important in predicting a successful outcome from physiotherapy in patients with MIRCT. The studies that focus on biomechanical factors predicting response to treatment were all conducted by surgeons who perhaps have more focus on biomedical features. It is worth noting that other domains such as psychological or social factors which have been shown to be important in similar patient populations have not been explored in as much depth in patients with MIRCT. In other cohorts of patients with shoulder pain, psychosocial factors feature prominently in the factors most associated with outcome. For example, one high quality longitudinal prospective prognostic study found that psychological and social factors have been found to be the strongest predictors of successful outcome in non-operative approaches to rotator cuff related shoulder pain [16]. Another well-powered multi-centre prospective cohort study—including 433 participants— of predictors of negative response to non-operative management in patients with full-thickness rotator cuff tears reported that low patient expectation of improvement with physiotherapy predicted poor response and the need to proceed to surgery [17]. The authors concluded that from their data, a patient’s decision to have surgery is more influenced by their negative expectations of physiotherapy than by their symptoms or biomechanical features. These two studies emphasise that it is important to consider other domains in addition to biomechanical factors.

The final challenge is the lack of consensus on what constitutes the best physiotherapy programme for patients with MIRCT. Flexion-based exercises have gained most attention in the literature but the structure, parameters, mode of delivery and content have been variable across studies [6]. Without clear predictors of successful outcomes, it is challenging to design effective physiotherapy interventions. If we do not know which factors are associated with a successful response to physiotherapy, then perhaps we are not targeting the important factors with the intervention. Furthermore, in some cases we may be subjecting patients to lengthy physiotherapy programmes when they have underlying characteristics that mean they are unlikely to benefit from this treatment approach. Some authors have expressed concern that younger patients should be considered earlier for surgical intervention as they are at particular risk of progression of glenohumeral arthritis and narrowing acromio-humeral distance and this may limit their surgical options to reverse total shoulder arthroplasty rather than less invasive and less radical surgical procedures [18].

Because of the lack of research evidence, expert opinion is important to gain consensus on factors which may be important in predicting response to physiotherapy in this patient group. Establishing a range of factors that experts agree are important in predicting response to physiotherapy in patients with MIRCT will provide insight for clinicians which will help them to more appropriately advise patients on their best treatment pathway. From a research standpoint, it will enable investigation of the predictive ability of factors that may be important. Regarding the gap in our understanding of what constitutes the ideal physiotherapy programme, one way of exploring which physiotherapy approaches are most helpful is to examine the factors that gain consensus as predictors of response to physiotherapy. Following from this, a novel physiotherapy programme can be devised to specifically target the factors that gain consensus as being modifiable by physiotherapists. There is some precedent for this in other areas of musculoskeletal physiotherapy. In the Low Back Pain literature, Cognitive Functional Therapy (CFT) has emerged as a promising effective treatment for disabling low back pain [19]. This approach recognises that a wide range of factors can contribute to the pain experience of an individual. CFT targets modifiable factors and has shown promise when evaluated with a randomised controlled trial. To date, a similar approach has not been applied in the physiotherapy treatment of patients with shoulder pain. In seeking to identify factors across multiple domains, our Delphi study may inform a similar treatment approach in patients with MIRCT.

Aims

-

1. To gain consensus on the factors that physiotherapists and orthopaedic surgeons think are important in predicting either a successful or unsuccessful response to physiotherapy in patients with massive irreparable rotator cuff tears.

Note: we have defined a successful outcome as an outcome where the patient decides that they do not need to have surgery and/or where they have regained sufficient pain-free overhead range of movement to allow them to carry out the everyday functions that are important to them.

2. To gain consensus on whether these factors are modifiable by physiotherapists.

3. To explore whether there were similarities or differences in the perceptions and opinions of physiotherapists and orthopaedic surgeons on these questions.

Method

Design

Consensus techniques that systematically obtain expert opinion such as the Delphi technique can be used when there is limited published evidence in an area [20, 21]. The Delphi technique is an iterative technique that uses sequential questionnaires starting with an information-seeking round and proceeding to prioritisation rounds. The aim is to reach a convergence of opinion and consensus [22]. One of the hallmarks of the Delphi technique is that participants complete the questionnaires anonymously and do not interact with each other. This helps to avoid social pressure and conformity to a dominant view [23]. Other strengths of the Delphi technique are that experts with a range of knowledge and experience can be recruited and because of the electronic format, this can be from a diverse range of countries and healthcare settings.

This 3-round international e-Delphi study was launched on 27/4/23 and closed on 7/10/23 and is reported following guidance on conducting and reporting Delphi studies (CREDES) [23]. Ethical approval was granted by the ethics committee of the University of Antwerp / UZA on 17/4/23 (ID 3777—BUN B3002023000060). Informed consent was obtained from all participants before completing the questionnaires. The consent process and each round was conducted electronically using REDCap, a secure web application for building and managing online surveys [24].

Data handling

Data were processed pseudo-anonymised using a coding system. The investigators and participants did not know which responses came from which expert panel member. To enable this, each participant was allocated a code by REDCap which was used when reviewing and analysing the responses. However, the code was linked to the participant’s name and contact details so that (a) they can be contacted for subsequent rounds of the Delphi and b) they can be given feedback if requested. All personal data were stored securely on a password-protected computer. Only members of the study team had access to the data. On completion of the study, all data were stored on the secured network of University of Antwerp for ten years. Storage on such a server has a virtually unlimited storage capacity, and the data will frequently be backed up on the server and through the web application REDCap.

Participants

Sampling method

Sampling was purposive, and targeted physiotherapists and orthopaedic surgeons fitting the expert criteria across different countries and healthcare systems. As it has been identified that patients may be offered different treatments based on their geographical location or healthcare environment [8], it was considered important to include experts from a variety of different settings. We limited the sampling to high and middle income countries (World Bank classification) as lower income countries do not have the same operative and non-operative treatment options for this patient group. We attempted to maintain a balanced sample of physiotherapists and surgeons across different countries and healthcare settings.

Sample size

There is no universally accepted guide to sample size calculation in Delphi studies and expert panels have ranged from less than 10 to several hundred participants [25]. Previous studies achieved consensus with 10–27 final round responses [26]. It has been suggested that to ensure normal distribution of responses, groups should have a minimum of 30 participants [27]. Response and dropout rates from Delphi studies are extremely variable but a response rate of 70% by round 3 can be estimated [28]. Indeed, it has been argued that a minimum response rate of 70% is required to maintain the rigour of the Delphi technique [29]. Therefore, based on a 70% response rate, we estimated that in order to achieve a sample of 30 experts in each group by round 3, we should aim for a round 1 sample of 43 physiotherapists and 43 orthopaedic surgeons.

Eligibility criteria & definition of an expert

In this study, two categories of participant were defined:

1) Experienced physiotherapists with special interest in shoulder rehabilitation. Defined as a) a physiotherapist who has more than ten years of experience working in musculoskeletal physiotherapy and treats more than ten shoulder patients per month or at least 30% of current practice relates to shoulder patients, or b) a physiotherapist with more than ten years of experience working in research and has published more than five papers on rotator cuff related shoulder pain and/or prognostic studies. As this was a clinically-focused study, participants working primarily in research must also have a clinical caseload. It is acknowledged that there is no universally accepted definition of an expert. We have followed the seminal work of Benner [30] in specifying a minimum of ten years of experience.

-

2) Consultant Orthopaedic surgeons specialising in shoulder surgery

Defined as a fully qualified consultant (attending) orthopaedic surgeon specialising in shoulder surgery working either a) clinically in shoulder surgery or b) in research related to rotator cuff related shoulder pain or prognostic studies. Again, orthopaedic surgeon participants working primarily in research must also have a clinical caseload.

To enable representation from both expert groups, recruitment was monitored to achieve approximately equal numbers of physiotherapist and orthopaedic surgeon participants. A separate study will explore the patient perspective on this topic.

Study Steering Group (SSG) & Public & Patient Involvement (PPI)

An SSG was formed consisting of the study researchers, external members with clinical and research expertise and PPI representation. The role of the SSG was to provide study oversight on protocol design, recruitment; data analysis, study conduct and dissemination. PPI followed the Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and Public 2 Short Form (GRIPP2_SF).

Recruitment

Experts were identified worldwide through the International Confederation of Societies of Shoulder & Elbow Therapy, the European Society of Shoulder & Elbow Rehabilitation and the European Society for Surgery of the Shoulder & Elbow. These three large organisations helped with recruitment by sharing details of the study and the study invitation with their members via email. Additional experts were identified through professional networks, national societies, PubMed literature searches for lead authors on physiotherapy for MIRCT, and the Expertscape platform. Recommendations from other experts also contributed to recruitment. The invitation email, which included study information and participation criteria, directed interested individuals to an online questionnaire hosted on REDCap. Upon providing informed consent, participants were directed to complete the Round 1 questionnaire. A template of the invitation email is available in Supporting Materials S1.

Procedure & analysis

Round 1

The objective of Round 1 was to develop a longlist of possible predictors and to organise them into categories. The Round one questionnaire was developed by the SSG. We deliberately limited the Round 1 questionnaire to one question to reduce the experts’ time taken to complete the questionnaire. Participants were asked to list a minimum of 6 factors that relate to a successful or unsuccessful response to physiotherapy in patients with MIRCT. We defined a successful response to physiotherapy as an outcome where the patient decides that they do not need to have surgery and/or where they have regained sufficient pain-free overhead range of movement to allow them to carry out the everyday functions that are important to them. The questionnaire was then pilot-tested on 5 expert clinicians to evaluate readability, relevance, and appropriateness. Based on their feedback (and the feedback from the ethics committee), minor edits were made in the study invitation email, the study information and consent forms and in the wording of the question. Participant demographic information (sex, age, country of practice, work setting) was collected.

Round 1 data analysis

Qualitative data from the round 1 responses were analysed thematically to compile new statements, grouping the factors into positive and negative factors. The primary collation of the responses was carried out by the lead researcher (EOC) who listed all of the responses, grouped them into suggested categories and then presented the list of factors to the SSG. The SSG then discussed the long list of factors, amended the categorisation, merged duplicates and agreed a final list. This was carried out over the course of two online meetings and several follow-up emails.

Round 2

The objective of round 2 was to evaluate the importance of identified predictors. Round 2 was developed from the themes and statements identified from Round 1. Study participants were presented with a list of the predictors identified in Round 1 and using a five-point Likert scale (1 = not at all important; 2 = slightly important; 3 = moderately important; 4 = very important; 5 = extremely important), were asked to rate their importance in predicting outcome from physiotherapy in patients with MIRCT. Each of the predictors could be expressed as either a positive or negative factor. For example, the presence of a subscapularis tear could be expressed as a predictor of unsuccessful outcome from physiotherapy or conversely the absence of a subscapularis tear as a predictor of successful response to physiotherapy. We expressed the predictor in the format that the majority of the participants expressed it in round 1. Participants were also given the option to add any additional predictors that they thought had been omitted from Round 1.

Round 2 data analysis

Quantitative data analysis was carried out by two researchers (EOC & AR) using SPSS version 28 to examine the experts’ level of consensus on rating the importance of each factor. Mean ranks of the rated importance of the predictors was calculated. Expert consensus (the extent to which the group of experts share the same opinion) was evaluated for each statement using the following a priori criteria: median (≥ 3) interquartile range (≤ 1.5) and percentage agreement (the percentage of responses rated moderately/very/extremely important) (≥ 60%) [26, 31, 32]. These criteria were chosen because Likert scale data is considered ordinal data [33]. Statements not reaching consensus were removed for subsequent rounds. To evaluate inter-expert agreement across multiple statements, Kendall’s Coefficient of Concordance was used with statistical significance set at p < 0.05 [31]. Kendall’s Coefficient of Concordance produces a W value describing the strength of expert agreement where 0 is no agreement and 1 is perfect agreement [34]. Descriptive benchmarks have been recommended for measuring inter-rater agreement for ordinal data as < 0.00 poor agreement, 0.00–0.20 slight agreement, 0.21–0.40 fair agreement, 0.41–0.60 moderate agreement, 0.61–0.80 substantial agreement, and 0.81–1.00 almost perfect agreement [35].

Round 3

The objective of round 3 was to gain further consensus on the importance of predictors identified in Round 2 and to gain consensus on which predictors are modifiable by physiotherapists. The final objective of Round 3 was to explore if there were differences in the opinions of the physiotherapist and orthopaedic surgeon experts. Participants were given feedback from Round 2 including the level of agreement and consensus reached in the previous round, and were again asked to rate the importance of each factor in predicting outcome from physiotherapy in patients with MIRCT. In Round 3 we also asked participants to agree or disagree with statements related to whether a particular factor is modifiable by physiotherapists. Using a 5-point Likert scale, participants were asked to rate their agreement with the statements. The 5-point scale was as follows: 1 = Strongly disagree; 2 = Disagree; 3 = Neither agree nor disagree; 4 = Agree; and 5 = Strongly agree.

Round 3 data analysis

Consensus and agreement were analysed in round 3 following the same procedure as for round 2. However, we used more stringent criteria to strengthen overall consensus (median ≥ 3.5, IQR ≤ 1, percentage agreement ≥ 70%) [26, 36]. Criteria for agreement and consensus in rounds 2 and 3 are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Agreement and consensus criteria for Rounds 2 and 3

Results

Demographic data

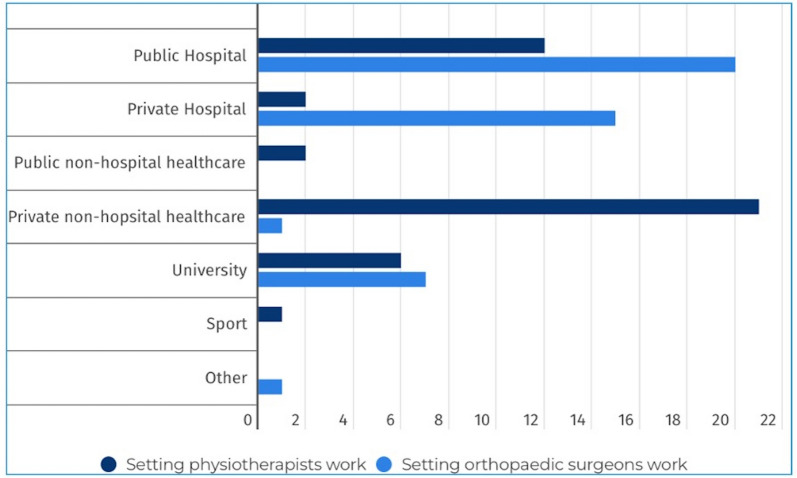

Round 1 was launched on 27/4/23 and closed on 27/5/23. 162 experts were identified and contacted by the lead author. Of those, 88 participated and completed the Round 1 questionnaire (44 physiotherapists and 44 orthopaedic surgeons). Figure 1 shows the breakdown of the settings in which the expert clinicians work.

Fig. 1.

Work settings in which expert participants work

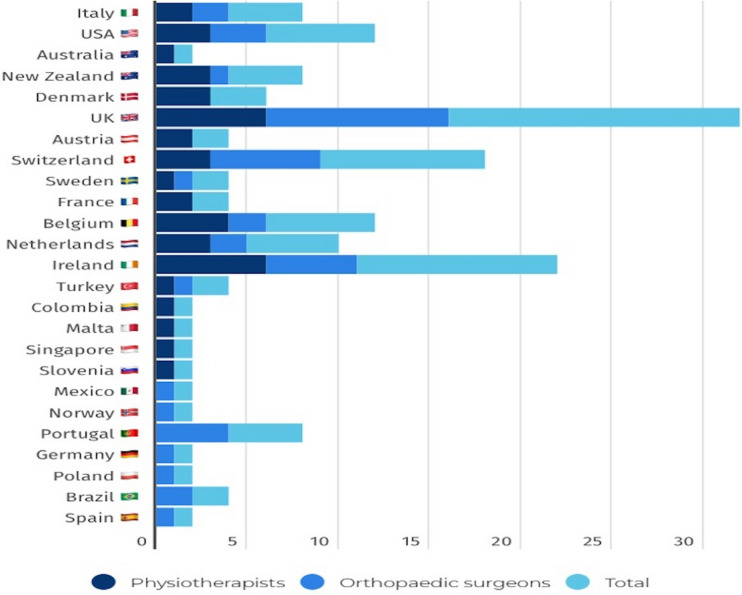

Participants were from 25 different countries. The breakdown of these countries is represented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Participant countries

Round 1 results

A total of 344 possible predictors of response to physiotherapy in patients with MIRCT were identified. All predictors that were mentioned more than once were included for analysis and once we had merged duplicates, we were left with 45 predictors. We grouped the predictors into 9 categories outlined in Table 2. All decisions regarding categorisation and merging of duplicates were ratified and agreed by the SSG.

Table 2.

Categories of predictors

The 45 predictors that were identified in Round 1 are listed in Table S2 in the supplementary materials section.

Round 2 results

Round 2 was launched on 3/7/23 and closed on 15/7/23. Of the 88 participants from Round 1, 72 (39 physiotherapists and 33 orthopaedic surgeons) responded. This represents an 81.81% response rate. Table 3 outlines the mean ranks of the importance of the predictors.

Table 3.

Mean ranks of the predictors in Round 2

The Kendall’s co-efficient of concordance (W) result for Round 2 was W = 0.268 with a significance of < 0.001. Whilst the analysis shows a high level of significance, the value of agreement indicates only fair agreement.

In Round 2, 29 predictors satisfied the a priori criteria for consensus. Table S3 in the supplementary materials section outlines the median, IQR and percentage agreement of the Round 2 predictors. Two additional predictors were added by participants: decreased internal rotation strength and radiological evidence of antero-superior migration of the head of the humerus. Both were identified as predictors of unsuccessful response to physiotherapy.

Round 3 results

Round 3 was launched on 21/09/23 and closed on 7/10/23. Of the 72 participants from Round 2, 70 (38 physiotherapists and 32 orthopaedic surgeons) responded. This figure includes one orthopaedic surgeon who participated in Round 1 but missed the Round 2 questionnaire due to it going into a junk email folder. The surgeon contacted the researchers to request participation in Round 3. This represents a 79.54% retention rate from Round 1. Table 4 outlines the mean ranks of the importance of the predictors in Round 3.

Table 4.

Mean ranks of the importance of the predictors round 3

The Kendall’s co-efficient of concordance (W) results for Round 3 indicate a high level of significance (< 0.01) but only fair agreement (0.22). We also carried out sub analysis of the physiotherapist and orthopaedic surgeon responses which indicated higher agreement in the physiotherapist group than the orthopaedic surgeon group. Table 5 outlines the Kendall’s coefficient of concordance for the importance of the predictors in Round 3.

Table 5.

Round 3 Kendall’s coefficient of concordance (W) for importance of the predictors

Regarding the importance of the predictors, 22 predictors satisfied the a priori criteria for consensus. These are outlined in Table 6.

Table 6.

Round 3: Median, IQR and percentage agreement (Importance)

Regarding the modifiability of the predictors, Table 7 outlines the mean ranks of the predictors in Round 3.

Table 7.

Round 3 mean ranks of the modifiability of the predictors

The Kendall’s co-efficient of concordance (W) results for Round 3 indicate a high level of significance (< 0.001) and moderate agreement (0.481) on the modifiability of the predictors. We also performed sub analysis of the physiotherapist and orthopaedic surgeon expert responses. Both demonstrated moderate agreement. Table 8 outlines the Kendall’s coefficient of concordance for modifiability of the predictors after Round 3 analysis.

Table 8.

Round 3 Kendall’s coefficient of concordance (W) for modifiability of the predictors

Regarding the modifiability of the predictors, consensus was achieved for 13 of the 31 predictors. In other words, 13 of the 31 predictors satisfied the a priori criteria. 12 of the predictors achieved consensus as being both important and modifiable. Table 9 outlines the median, IQR and percentage agreement.

Table 9.

Round 3: Median, IQR and percentage agreement (Modifiability)

apredictor achieved consensus as being both important and modifiable

We also performed a separate sub analysis of the physiotherapist and orthopaedic surgeon Round 3 data. Regarding the importance of the predictors, the physiotherapist expert group achieved consensus for 21 of the predictors whereas the orthopaedic surgeon expert group achieved consensus for 16 of the predictors. Regarding the modifiability of the predictors, consensus was achieved in the physiotherapist expert group for 18 of the predictors and for 11 of the predictors in the orthopaedic surgeon expert group. When we analysed which predictors gained consensus as being both important for predicting successful or unsuccessful outcome from physiotherapy and also modifiable by physiotherapists, 17 predictors gained consensus in the physiotherapist group and 9 predictors gained consensus in the orthopaedic surgeon group. Table S4 in supplementary materials compares the consensus for the physiotherapists and orthopaedic surgeons and highlights the areas of agreement and disagreement between the two professional groups. Table 10 summarises the key findings after Round 3.

Table 10.

Summary of key findings after Round 3

Discussion

This is the first study to gain expert consensus of physiotherapists and orthopaedic surgeons on the factors that are important for predicting response to physiotherapy in patients with MIRCT. It is also the first study to explore whether there were similarities or differences in the perceptions of each professional group on this question.

Factors predicting response to physiotherapy in patients with MIRCT

Twenty-two factors gained consensus as being important in predicting outcome from physiotherapy in patients with MIRCT. The factors were from a wide variety of domains: biomechanical, psychological, social, general health, lifestyle, communication / healthcare interaction and pain. The breadth of the factors is an important finding because although previous studies of shoulder pain have demonstrated an association between psychological factors and outcome from physiotherapy intervention [16, 17], no previous studies have shown this in patients with MIRCT. In addition, physiotherapy programmes for MIRCT that have been described and tested in published studies have focused solely on biomechanical factors and no study has described interventions that target other domains.

Factors modifiable by physiotherapists

Of the 22 factors that gained consensus as being important, ten of these gained consensus as being not modifiable by physiotherapists and 12 gained consensus as being modifiable by physiotherapists. In the low back pain literature, cognitive functional therapy (CFT) has demonstrated efficacy as an individualised approach that targets the interplay between multiple factors that contribute to pain and disability [37]. CFT uses a framework to identity modifiable and non-modifiable factors associated with a person’s disabling back pain. This framework distinguishes between patient factors and clinician factors. Given the breadth of the factors that gained consensus in our Delphi study, it is helpful to organise and review these factors using a framework based on the CFT model. Several clinician factors gained consensus in our study and these are factors that are readily amenable to change.

Important but non-modifiable patient factors

It is interesting to note that the top three predictors that achieved expert consensus as being important but not modifiable are all psychological factors. This is in line with previous studies of other cohorts of patients with shoulder pain [16, 17]. It is also notable that the majority of these non-modifiable predictors were typically expressed by the participants as negative factors i.e. predictors of unsuccessful outcome from physiotherapy. Of these 10 predictors, only the presence of a complete tear of subscapularis [12] and glenohumeral arthropathy [14] were identified in previous studies as being possible predictors of response to physiotherapy in patients with MIRCT.

Important and modifiable factors

Twelve factors achieved consensus as being both important in predicting response to physiotherapy and also modifiable by physiotherapists. Eight of these factors are patient factors and four are clinician factors. Early intervention with physiotherapy was more difficult to categorise. It could be considered an external social factor i.e. access to physiotherapy or healthcare services. In some cases it could be considered a patient factor such as ability to pay for healthcare or motivation to seek treatment for the shoulder. For the purposes of this study, we have designated it as a patient factor.

Patient factors

Positive expectation

Positive expectation and belief in the success of physiotherapy ranked highest in importance. 90% of participants agreed that it was modifiable. This is a strong endorsement for the key role that positive expectation plays in patients with MIRCT and echoes previous studies on shoulder pain [16] and in other musculoskeletal conditions [38]. It seems clear that patient expectation does not exist in isolation and is mediated by, and interacts with other factors. Psychological factors such as catastrophising [39] and depression and anxiety [40] may interact with expectation to influence clinical outcomes related to musculoskeletal pain conditions. In addition, we hypothesise that other patient factors that have gained consensus as important in this Delphi study such as the patient having a high level of self-efficacy and the patient having a previous positive experience of physiotherapy are additional important elements that may interact with patient expectation and therefore outcome.

The patient’s high level of motivation to participate

The finding that high levels of motivation gained consensus as important in predicting successful outcome echoes a recent qualitative evidence meta-synthesis of 19 studies exploring patients’ experience of shoulder pain that highlighted the importance of motivation [41]. Patients cited fear of pain, lack of perceived early improvement, low energy levels, poor time-management and reduced incentive to continue once symptoms resolved as key factors that influence their motivation to engage in exercise-based physiotherapy. We suggest that it is likely that clinician factors such as therapeutic alliance, the ability of the therapist to provide a high quality explanation to the patient and collaborative goal-setting can impact a patient’s motivation to participate.

Realistic expectations

It is interesting that the patient having realistic expectations of the outcome of physiotherapy gained consensus as both important and modifiable. There is a paucity of literature in this area, and it therefore requires more attention. We would contend that the clinician factors outlined below: high quality explanation, collaborative goal setting and therapeutic alliance can all influence the patient’s expectations.

Kinesiophobia

Kinesiophobia was seen as predictive of an unsuccessful outcome from physiotherapy. This is a key finding as although there is considerable evidence demonstrating a link between kinesiophobia and poorer prognosis with low back pain [42, 43] and indicating that kinesiophobia is modifiable by physiotherapists [44], there is a paucity of literature specifically related to the shoulder. One recent cross-sectional study of individuals with chronic shoulder pain, found an association between kinesiophobia and pain intensity and disability. However, the authors highlighted that these findings only explained 19% of the variance in shoulder pain and disability scores [45]. Another recent study evaluating kinesiophobia in patients with shoulder pain found that kinesiophobia was associated with shoulder function, but its influence was small (2.6%-4.5%, P < 0.05) and disappeared after adjusting for pain and sociodemographic and impairment variables [46].

Biomechanical factors

Three biomechanical factors were seen as predictive of a successful outcome from physiotherapy: clinical evidence of force production of the remaining parts of the rotator cuff, good passive range of motion and good active range of motion of the shoulder when the patient is lying supine. Of these, only good passive range of motion was highlighted in a previous study [14]. Clinical examination of patients (and future studies) should include measurement of active and passive range of motion testing in supine and assessment of strength of the remaining intact parts of the rotator cuff.

Early intervention with physiotherapy

Early intervention with physiotherapy was the lowest ranked in terms of importance. Timing of physiotherapy intervention for MIRCT has not been well studied in the literature. Most studies did not report the duration of symptoms before physiotherapy intervention and the two studies that did [11, 47] did not examine the relationship between duration of symptoms and outcome from physiotherapy treatment. This area needs to be investigated further. Indeed there is no consensus in the literature as to what constitutes early intervention.

Clinician factors

Sufficient dosage and quality of exercise prescription

Sufficient dosage and quality of exercise prescription has not been well researched in MIRCT. In our review of the literature we found that the content, delivery and duration of exercise interventions for MIRCT is highly variable across the available studies [6]. Following their recent systematic review of non-operative therapy for massive rotator cuff tears, Shepet et al. [48] developed a synthesized non-operative treatment protocol. The authors acknowledged that this protocol is based on low-level evidence. However, it identified key elements of the delivery of the rehabilitation based on 4 studies with the best outcomes. These key elements included manual therapy, passive range of motion exercises, postural re-education, scapular stabilization and proprioceptive exercises and a structured progressive strengthening programme. It was proposed that pain should be monitored closely when carrying out the exercises and should be no more than 4/10 on the visual analogue scale during or after the exercises. With regard to duration of the programme, the authors recommended a minimum of 12 weeks but that it may need to last up to 5 months. Regarding the quality of the exercise prescription, in the supplementary information section of the paper, the authors outline and illustrate specific exercises to target the key areas. These include strategies to re-educate muscle recruitment and then strengthen deltoid and teres minor commencing in supine and progressing to sitting and eventually standing and with increasing resistance. This is the most comprehensive guide to exercise prescription for patients with MIRCT available in the literature but requires evaluation with further research. Reviewing the literature related to dose of exercise and clinical outcomes in other types of shoulder pain and other areas of musculoskeletal pain highlights that the relationship between dose of exercise and clinical outcome is not straightforward. A recent systematic review of resistance exercise for knee and hip osteoarthritis found that although resistance exercise interventions of 3 to 6 months duration improve pain and physical function, these improvements do not depend on exercise volume or adherence. The authors conclude that exercise does not require rigid adherence to a specific dose [49]. A recent randomised controlled trial of exercise therapy for subacromial shoulder pain showed that adding a higher dose of shoulder exercise (which at least doubled the dose of shoulder strengthening) did not result in superior outcomes [50]. Interestingly a secondary analysis demonstrated that those with lower baseline catastrophising had improved benefits from the higher exercise dose [51]. This indicates there is low certainty about a dose–response relationship between exercise dose and clinical outcomes in patients with shoulder pain and it is likely that dose interacts with other variables to have different effects in different patients. Because of this, Powell and colleagues in their critical review of exercise therapy for shoulder pain have suggested that a patient’s treatment goals, stage of rehabilitation and irritability of symptoms may all influence the optimal dose of exercise [52].

High quality explanation, collaborative goal setting and therapeutic alliance

These three factors, which ranked extremely highly as both important and modifiable, are inextricably interlinked. The original definition of the therapeutic relationship characterised it as consisting of three essential qualities: (i) an emotional bond of trust, caring and respect (ii) agreement on the goals of therapy (iii) collaboration on the tasks of treatment [53]. The importance of this is highlighted by the finding that the quality of the therapeutic relationship has been shown to be associated with both patient satisfaction [54] and clinical outcomes in physiotherapy [55, 56]. Furthermore, a recent qualitative study on treatment decision-making for shoulder pain highlighted the importance of therapeutic alliance to both patients and physiotherapists [57]. Participants emphasised trust, rapport and patient confidence in the healthcare professional as the essential components of the therapeutic relationship and that these enhance patient expectations and improve engagement with the treatment plan. Although there are no studies specifically demonstrating the importance of therapeutic alliance in patients with MIRCT, wider research evidence from critical realist studies in the shoulder and lumbar spine suggest that the clinical context that an exercise programme is delivered in may determine whether or not the patient responds positively to the intervention [58, 59]. It is thought that the patient–clinician therapeutic consultation builds a foundation of trust and was associated with improved adherence, engagement and clinical outcomes [59].

We therefore suggest that providing a high-quality explanation and collaboratively setting goals that are meaningful to the patient are key skills that can enhance therapeutic alliance.

Differences in the perceptions and opinions of physiotherapists and orthopaedic surgeons

Of the 22 predictors that gained overall consensus as important, six did not demonstrate agreement between physiotherapists and orthopaedic surgeon participants, and four did not demonstrate agreement with regard to whether the predictor could be modified by physiotherapists. Overall, the levels of agreement for the physiotherapists were higher than for the orthopaedic surgeons with regard to both importance and modifiability of the factors. The areas of disagreement between the two professional groups highlight potentially contentious areas or perhaps reflect that orthopaedic surgeons and physiotherapists may see different profiles of patients with MIRCT at different stages in their treatment journeys. The presence of a tear of subscapularis, strong therapeutic alliance and the presence of depression or anxiety gained overall consensus as important but only one of the criteria (IQR ≤ 1.5) did not satisfy the a priori threshold for consensus amongst the orthopaedic surgeons. Given that over 93% of the orthopaedic surgeon participants rated all of these as important, we have concluded that for these factors there was no real disagreement between the two profession groups. The areas of higher disagreement between the professional groups are elaborated on below.

Catastrophising

Catastrophising has consistently been demonstrated to be associated with poorer outcomes from physiotherapy interventions [60]. Catastrophising was seen by surgeons as not modifiable by physiotherapists, whereas physiotherapists saw it as modifiable. This contentiousness is reflected in the literature in the area. We are not aware of any studies that have specifically evaluated interventions to modify catastrophising in patients with MIRCT or shoulder pain. However, one scoping review of interventions to reduce catastrophising in surgical patients specifically looked at whether physiotherapy can improve pain catastrophising scores [61]. Of the nine physiotherapy studies that they included, they found overall mean improvements that varied from 2.5 – 16.6 points on the Pain Catastrophising Scale. However only two of these studies demonstrated improvements that were clinically important. An additional study that they categorised as a patient education intervention rather than physiotherapy also demonstrated clinically important improvements. Three further studies in the same review that used cognitive behavioural interventions delivered by psychologists demonstrated clinically important improvements in catastrophising. The literature to date therefore suggests that catastrophising is not a fixed trait and that some patients can reduce their level of catastrophising following physiotherapy interventions but that this is often not successful. There are likely multiple factors that also contribute and interact. One study identified that the presence of mental health problems such as depression or Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder markedly reduced that effectiveness of physiotherapy interventions for reducing catastrophising [62]. This lack of clarity in the literature likely contributed to the lack of agreement in our study between the physiotherapists and orthopaedic surgeons on this factor. Another possible explanation for the difference is that the physiotherapists may have considered physiotherapy interventions to include a broader remit such as pain neuroscience education and cognitive behavioural interventions which have demonstrated efficacy when delivered by physiotherapists [63, 64].

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy, the confidence a person has in their own ability to achieve a desired outcome [65] has been identified as an important factor associated with response to physiotherapy in patients with shoulder pain. One multi-centre study of 1030 patients with shoulder pain identified pain self-efficacy as one of the two most influential factors associated with outcome from physiotherapy [16]. The authors recommended that pain self-efficacy should be included the physiotherapy assessment but acknowledge that further research is needed to determine if it can be modified by physiotherapy interventions.

Self-efficacy was seen by surgeons as not modifiable by physiotherapists, whereas physiotherapists saw it as modifiable. Once again, this lack of agreement is reflected in the literature. Much of the research on self-efficacy has focused on chronic pain. One systematic review of 60 randomised controlled trials for interventions for chronic musculoskeletal pain demonstrated improvement in self-efficacy with multi-component interventions such as exercise and psychological interventions [66]. Self-management strategies did not improve self-efficacy and no interventions improved pain self-efficacy after 1 year. The authors cautioned that the certainty of the evidence is low due to low effect sizes and high risk of bias in the included studies. Therefore in a chronic pain population the evidence suggests that it is very challenging to modify pain self-efficacy. Conversely, in low back pain populations, there is moderate certainty evidence that exercise can increase self-efficacy [67]. This area requires further exploration in shoulder pain patients.

High levels of baseline pain

High levels of baseline pain was seen by surgeons as important, whereas physiotherapists did not agree. It is possible that this difference of opinion between the professional groups is related to the two different professions seeing different profiles of patients with MIRCT in clinical practice, with surgeons perhaps seeing more patients who have previously tried physiotherapy and not tolerated it due to pain.

Strong biomedical beliefs about damage to the tendons

Strong biomedical beliefs about damage to the tendon gained consensus as being important but not modifiable by physiotherapists. However, it was ranked very lowly and demonstrated the largest disparity in the opinions between the two professional groups. The physiotherapists viewed it as both important and modifiable but surgeons viewed it as not important and not modifiable by physiotherapists. Two recent qualitative studies found that biomechanical beliefs about shoulder pain predominated in both patients and healthcare professionals and that these beliefs impacted clinical decision-making regarding treatment with many patients believing that if there was structural damage present that surgery was either the only solution or the preferred or superior option [41, 57]. These findings highlight the need for both physiotherapists and surgeons to explore these beliefs with patients with MIRCT. If for example, a patient expresses a strong belief that because they have torn tendons they need to have an operation to achieve a good outcome then they are unlikely to engage with a physiotherapy programme. This also links to the point about patient expectations of success discussed previously. The results of this Delphi study suggest that physiotherapists have more confidence in changing these beliefs. Perhaps this is a reflection of the fact that physiotherapists typically have the opportunity to spend more time with their patients than surgeons.

Clinical implications

Expert shoulder clinicians have demonstrated consensus that a broad range of factors influence the outcome of physiotherapy in patients with MIRCT. When assessing and treating these patients, clinicians should consider both patient and clinician factors.

Physical assessment should include testing of passive range of motion, active range of motion in supine and assessment of force production of the remaining intact parts of the rotator cuff. Our expert panel suggest that these are key biomechanical factors which may help identify patients likely to improve with physiotherapy. Patient expectations and motivation should also be assessed as both ranked very highly in importance.

When making a decision about whether a patient with MIRCT is likely to have a successful outcome from physiotherapy, the presence of several non-modifiable predictors may be helpful in identifying patients who are less likely to improve. For example, a patient with biomechanical features such as a complete tear of subscapularis and glenohumeral arthropathy and also psychological features such as underlying depression or anxiety and strong biomedical beliefs regarding the damage to the tendons may not be a good candidate for physiotherapy. According to our expert panel, additional presence of widespread pain, high baseline pain levels and low baseline levels of activity suggest that the patient is less likely to have a successful outcome. It is worth noting that patients with negative biomechanical factors for response to physiotherapy may be amenable to surgery. However those who have negative psychological and social factors may not be good candidates for either physiotherapy or surgery.

Particular attention should be paid to factors that are potentially modifiable. Optimising clinician factors such as taking the time to fully explain the nature of MIRCT to patients and collaboratively setting realistic goals that are meaningful to the patient are fundamental components of the physiotherapy encounter. The resultant improved therapeutic alliance may in turn influence patient factors such as motivation and willingness to engage in rehabilitation. It is also possible that it may reduce catastrophising and kinesiophobia.

Research implications

The 22 factors that gained consensus in our Delphi study as important in predicting outcome from physiotherapy in patients with MIRCT provide a platform for future research. The factors should now be evaluated in a prospective prognostic study. PROGRESS guidelines suggest that ideally these studies should have a no intervention group and be nested in a randomised controlled trial [15]. The results of this Delphi study also contribute to our knowledge regarding the content of physiotherapy interventions for patients with MIRCT. Previous studies have focused on the biomechanical elements of physiotherapy interventions. However, in our study, the predictors that gained consensus also included psychological and social factors and clinician factors related to communication and healthcare interaction. The broad range of factors that gained consensus as both important and modifiable are therefore suggested targets for physiotherapy intervention and should be used to design a novel physiotherapy programme that can be tested with a randomised controlled trial.

Strengths & limitations

This is the first study to gain expert consensus on potential predictors of response to physiotherapy in patients with MIRCT. The study was conducted according to a protocol submitted to the ethics committee which stated the a priori criteria for consensus. It was reported according to CREDES guidance [23]. The study recruited a large group of expert shoulder clinicians from a wide range of countries. The response rate from Round 1 to 3 was high (79.54%), highlighting the relevance of the topic. Use of the SSG including clinicians, methodologists and patients provided rigorous oversight of the study method, conduct and analysis. The study does have some limitations. The study did not include patients with experience of MIRCT. However this will be explored in a separate study. The questionnaire was only provided in English language. This means that there was some inherent selection bias (and response bias) in the recruitment of the experts and therefore may have introduced some bias in the answers. Because the sample only included respondents from high and middle income countries, it is likely that there was bias in the responses and we cannot necessarily extrapolate the results of this study to lower income countries where the choice of treatment options and perspectives may be very different. Finally the Delphi method has been criticised for the lack of guidance and agreement on the definition of expertise, the sample size, definitions of consensus and what are the most appropriate statistical methods [68].

Conclusions

This Delphi study set out to identify the predictors of response to physiotherapy in patients with MIRCT and to explore if there were similarities or differences in the perceptions of physiotherapists and orthopaedic surgeons. Twenty two factors gained consensus as important and twelve of these gained consensus as modifiable by physiotherapists. There was broad agreement between the physiotherapists and orthopaedic surgeons with some differences in perceptions of what factors are modifiable by physiotherapists. The factors that gained consensus were from a broad range of domains: biomechanical, psychological, social, co-morbidities, communication / healthcare interactions and pain. They included both patient factors and clinician factors. When assessing and treating patients with MIRCT, physiotherapists and surgeons should include assessment of this broad range of factors and target the modifiable factors with their interventions. Clinician factors such as optimising therapeutic alliance with high quality explanation of the condition and realistic and collaborative goal-setting should be given particular attention. This in turn may influence patient factors such as patient expectations, engagement with the physiotherapy programme, motivation and self-efficacy thus creating the ideal environment to intervene on a biomechanical level with exercises.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 1: S1. Email invitation to prospective participants.

Supplementary Material 2: Table S2. Predictors of response to physiotherapy in patients with MIRCT identified in Round 1.

Supplementary Material 3. Table S3. Median, IQR and percentage agreement (Round 2).

Supplementary Material 4: Table S4. Predictors reaching consensus for physiotherapists versus orthopaedic surgeons.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to than Lorcán Ó hUallacháin for his contributions as patient representative in the initial conceptualisation of the study and his participation in the study steering group. The authors would also like to thank Bernard Osangier & Tafadzwa Maseko REDCap administrators for their help and support with design and analysis of the Delphi questionnaire on REDCap. Finally the authors would like to thank all of the physiotherapist and orthopaedic surgeon participants for giving up their time to contribute to the study.

Authors’ contributions

The study was conceptualised by EOC and developed by FS and AR with AR taking a central role in overseeing the Delpi methodolgy. Data curation: EOC Formal analysis: EOC, AR, FS Investigation: EOC Methodology: EOC, AR, FS, AJ, RD Project administration: EOC Supervision: FS, AR Validation: EOC Visualization: EOC Writing – original draft: EOC Writing – review & editing: EOC, FS, AR, AJ, RD.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was granted by the ethics committee of the University of Antwerp / UZA on 17/4/23 (ID 3777—BUN B3002023000060). Informed consent was obtained from all participants before completing the questionnaires. The consent process and each round was conducted electronically using REDCap, a secure web application for building and managing online surveys [24].

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gerber C, Fuchs B, Hodler J. The results of repair of massive tears of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(4):505–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Juhan T, Stone M, Jalali O, Curtis W, Prodromo J, Weber AE, et al. Irreparable rotator cuff tears: current treatment options. Orthop Rev (Pavia). 2019;11(3):8146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thes A, Hardy P, Bak K. Decision-making in massive rotator cuff tear. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23(2):449–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denard PJ, Ladermann A, Jiwani AZ, Burkhart SS. Functional outcome after arthroscopic repair of massive rotator cuff tears in individuals with pseudoparalysis. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(9):1214–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hollinshead RM, Mohtadi NG, Vande Guchte RA, Wadey VM. Two 6-year follow-up studies of large and massive rotator cuff tears: comparison of outcome measures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(5):373–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conaire EO, Delaney R, Ladermann A, Schwank A, Struyf F. Massive irreparable rotator cuff tears: which patients will benefit from physiotherapy exercise programs? A narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(7):5242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kucirek NK, Hung NJ, Wong SE. Treatment options for massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2021;14:304–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ladermann A, Collin P, Athwal GS, Scheibel M, Zumstein MA, Nourissat G. Current concepts in the primary management of irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears without arthritis. EFORT Open Rev. 2018;3(5):200–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tashjian RZ. Epidemiology, natural history, and indications for treatment of rotator cuff tears. Clin Sports Med. 2012;31(4):589–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy O, Mullett H, Roberts S, Copeland S. The role of anterior deltoid reeducation in patients with massive irreparable degenerative rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(6):863–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yian EH, Sodl JF, Dionysian E, Schneeberger AG. Anterior deltoid reeducation for irreparable rotator cuff tears revisited. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(9):1562–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collin PG, Gain S, Nguyen Huu F, Ladermann A. Is rehabilitation effective in massive rotator cuff tears? Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2015;101(4 Suppl):S203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoon TH, Kim SJ, Choi CH, Yoon SP, Chun YM. An intact subscapularis tendon and compensatory teres minor hypertrophy yield lower failure rates for non-operative treatment of irreparable, massive rotator cuff tears. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(10):3240–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vad VB, Warren RF, Altchek DW, O’Brien SJ, Rose HA, Wickiewicz TL. Negative prognostic factors in managing massive rotator cuff tears. Clin J Sport Med. 2002;12(3):151–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hingorani AD, Windt DA, Riley RD, Abrams K, Moons KG, Steyerberg EW, et al. Prognosis research strategy (PROGRESS) 4: stratified medicine research. BMJ. 2013;346:e5793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chester R, Jerosch-Herold C, Lewis J, Shepstone L. Psychological factors are associated with the outcome of physiotherapy for people with shoulder pain: a multicentre longitudinal cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(4):269–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunn WR, Kuhn JE, Sanders R, An Q, Baumgarten KM, Bishop JY, et al. 2013 Neer Award: predictors of failure of nonoperative treatment of chronic, symptomatic, full-thickness rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(8):1303–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ladermann A, Denard PJ, Collin P. Massive rotator cuff tears: definition and treatment. Int Orthop. 2015;39(12):2403–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Sullivan PB, Caneiro JP, O’Keeffe M, Smith A, Dankaerts W, Fersum K, et al. Cognitive functional therapy: an integrated behavioral approach for the targeted management of disabling low back pain. Phys Ther. 2018;98(5):408–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy MK, Black NA, Lamping DL, McKee CM, Sanderson CF, Askham J, et al. Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technol Assess. 1998;2(3):i–iv 1-88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell SM, Cantrill JA. Consensus methods in prescribing research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2001;26(1):5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Price J, Rushton A, Tyros V, Heneghan NR. Consensus on the exercise and dosage variables of an exercise training programme for chronic non-specific neck pain: protocol for an international e-Delphi study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(5):e037656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jünger S, Payne SA, Brine J, Radbruch L, Brearley SG. Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: Recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat Med. 2017;31(8):684–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cantrill JA, Sibbald B, Buetow S. The Delphi and nominal group techniques in health services research. Int J Pharm Pract. 1996;4(2):67–74. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Price J, Rushton A, Tyros V, Heneghan NR. Expert consensus on the important chronic non-specific neck pain motor control and segmental exercise and dosage variables: an international e-Delphi study. PLoS One. 2021;16(7):e0253523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sim J, Wright C. Research in health care: concepts, designs and methods. Cheltenham: Nelson Thornes; 2000.

- 28.Keeney S, McKenna HA, Hasson F. The Delphi technique in nursing and health research. Chichester: Wiley; 2011.

- 29.Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(4):1008–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benner P. From novice to expert. Am J Nurs. 1982;82(3):402–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.von der Gracht HA. Consensus measurement in Delphi studies. Technol Forecast Soc Chang. 2012;79(8):1525–36. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Graham-Clarke E, Rushton A, Marriott J. A Delphi study to explore and gain consensus regarding the most important barriers and facilitators affecting physiotherapist and pharmacist non-medical prescribing. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0246273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna H. Consulting the oracle: ten lessons from using the Delphi technique in nursing research. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53(2):205–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Field AP. Kendall’s coefficient of concordance. Encycl Stat Behav Sci. 2005;2:1010–1. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zambaldi M, Beasley I, Rushton A. Return to play criteria after hamstring muscle injury in professional football: a Delphi consensus study. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(16):1221–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kent P, Haines T, O’Sullivan P, Smith A, Campbell A, Schutze R, et al. Cognitive functional therapy with or without movement sensor biofeedback versus usual care for chronic, disabling low back pain (RESTORE): a randomised, controlled, three-arm, parallel group, phase 3, clinical trial. Lancet. 2023;40:1866–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wassinger CA, Edwards DC, Bourassa M, Reagan D, Weyant EC, Walden RR. The role of patient recovery expectations in the outcomes of physical therapist intervention: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2022;102(4):8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Severeijns R, Vlaeyen JW, van den Hout MA, Weber WE. Pain catastrophizing predicts pain intensity, disability, and psychological distress independent of the level of physical impairment. Clin J Pain. 2001;17(2):165–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bair MJ, Wu J, Damush TM, Sutherland JM, Kroenke K. Association of depression and anxiety alone and in combination with chronic musculoskeletal pain in primary care patients. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(8):890–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maxwell C, Robinson K, McCreesh K. Understanding shoulder pain: a qualitative evidence synthesis exploring the patient experience. Phys Ther. 2021;101(3):pzaa229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adnan R, Van Oosterwijck J, Cagnie B, Dhondt E, Schouppe S, Van Akeleyen J, et al. Determining predictive outcome factors for a multimodal treatment program in low back pain patients: a retrospective cohort study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2017;40(9):659–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alhowimel A, AlOtaibi M, Radford K, Coulson N. Psychosocial factors associated with change in pain and disability outcomes in chronic low back pain patients treated by physiotherapist: a systematic review. SAGE Open Med. 2018;6:2050312118757387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Bogaert W, Coppieters I, Kregel J, Nijs J, De Pauw R, Meeus M, et al. Influence of baseline kinesiophobia levels on treatment outcome in people with chronic spinal pain. Phys Ther. 2021;101(6):pzab076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luque-Suarez A, Martinez-Calderon J, Navarro-Ledesma S, Morales-Asencio JM, Meeus M, Struyf F. Kinesiophobia is associated with pain intensity and disability in chronic shoulder pain: a cross-sectional study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2020;43(8):791–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clausen MB, Witten A, Holm K, Christensen KB, Attrup ML, Holmich P, et al. Glenohumeral and scapulothoracic strength impairments exists in patients with subacromial impingement, but these are not reflected in the shoulder pain and disability index. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18(1):302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Christensen BH, Andersen KS, Rasmussen S, Andreasen EL, Nielsen LM, Jensen SL. Enhanced function and quality of life following 5 months of exercise therapy for patients with irreparable rotator cuff tears - an intervention study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shepet KH, Liechti DJ, Kuhn JE. Nonoperative treatment of chronic, massive irreparable rotator cuff tears: a systematic review with synthesis of a standardized rehabilitation protocol. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020;30(6):1431–44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Marriott KA, Hall M, Maciukiewicz JM, Almaw RD, Wiebenga EG, Ivanochko NK, et al. Are the effects of resistance exercise on pain and function in knee and hip osteoarthritis dependent on exercise volume, duration, and adherence? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2024;76(6):821–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clausen MB, Holmich P, Rathleff M, Bandholm T, Christensen KB, Zebis MK, et al. Effectiveness of adding a large dose of shoulder strengthening to current nonoperative care for Subacromial Impingement: a pragmatic, double-blind randomized controlled trial (SExSI Trial). Am J Sports Med. 2021;49(11):3040–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clausen MB, Rathleff MS, Graven-Nielsen T, Bandholm T, Christensen KB, Holmich P, et al. Level of pain catastrophising determines if patients with long-standing subacromial impingement benefit from more resistance exercise: predefined secondary analyses from a pragmatic randomised controlled trial (the SExSI Trial). Br J Sports Med. 2023;57(13):842–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Powell JK, Lewis J, Schram B, Hing W. Is exercise therapy the right treatment for rotator cuff-related shoulder pain? Uncertainties, theory, and practice. Musculoskeletal Care. 2024;22(2):e1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bordin ES. The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy. 1979;16(3):252. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hush JM, Cameron K, Mackey M. Patient satisfaction with musculoskeletal physical therapy care: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2011;91(1):25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hall AM, Ferreira PH, Maher CG, Latimer J, Ferreira ML. The influence of the therapist-patient relationship on treatment outcome in physical rehabilitation: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2010;90(8):1099–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Latimer J, Adams RD. The therapeutic alliance between clinicians and patients predicts outcome in chronic low back pain. Phys Ther. 2013;93(4):470–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maxwell C, McCreesh K, Salsberg J, Robinson K. ‘Down to the person, the individual patient themselves’: a qualitative study of treatment decision-making for shoulder pain. Health Expect. 2022;25(3):1108–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Powell JK, Costa N, Schram B, Hing W, Lewis J. “Restoring that faith in my shoulder”: a qualitative investigation of how and why exercise therapy influenced the clinical outcomes of individuals with rotator cuff-related shoulder pain. Phys Ther. 2023;103(12):pzad088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wood L, Foster NE, Dean SG, Booth V, Hayden JA, Booth A. Contexts, behavioural mechanisms and outcomes to optimise therapeutic exercise prescription for persistent low back pain: a realist review. Br J Sports Med. 2024;58(4):222–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wertli MM, Burgstaller JM, Weiser S, Steurer J, Kofmehl R, Held U. Influence of catastrophizing on treatment outcome in patients with nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39(3):263–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gibson E, Sabo MT. Can pain catastrophizing be changed in surgical patients? A scoping review. Can J Surg. 2018;61(5):311–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Slepian P, Bernier E, Scott W, Niederstrasser NG, Wideman T, Sullivan M. Changes in pain catastrophizing following physical therapy for musculoskeletal injury: the influence of depressive and post-traumatic stress symptoms. J Occup Rehabil. 2014;24(1):22–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hall A, Richmond H, Copsey B, Hansen Z, Williamson E, Jones G, et al. Physiotherapist-delivered cognitive-behavioural interventions are effective for low back pain, but can they be replicated in clinical practice? A systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Louw A, Zimney K, Puentedura EJ, Diener I. The efficacy of pain neuroscience education on musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review of the literature. Physiother Theory Pract. 2016;32(5):332–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. United States: Worth Publishers; 1997.

- 66.Martinez-Calderon J, Flores-Cortes M, Morales-Asencio JM, Fernandez-Sanchez M, Luque-Suarez A. Which interventions enhance pain self-efficacy in people with chronic musculoskeletal pain? A systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, including over 12 000 participants. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2020;50(8):418–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gilanyi YL, Wewege MA, Shah B, Cashin AG, Williams CM, Davidson SRE, et al. Exercise increases pain self-efficacy in adults with nonspecific chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2023;53(6):335–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shang Z. Use of Delphi in health sciences research: a narrative review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102(7):e32829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: S1. Email invitation to prospective participants.

Supplementary Material 2: Table S2. Predictors of response to physiotherapy in patients with MIRCT identified in Round 1.

Supplementary Material 3. Table S3. Median, IQR and percentage agreement (Round 2).

Supplementary Material 4: Table S4. Predictors reaching consensus for physiotherapists versus orthopaedic surgeons.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.