Abstract

The roles of sex hormones such as estradiol, testosterone, and sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) in the etiology of lung and colorectal cancers in women, among the most common cancers after breast cancer, are unclear. This Mendelian randomization (MR) study evaluated such potential causal associations in women of European ancestry. We used summary statistics data from genome-wide association studies on sex hormones and from the Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT) and large consortia on cancers. There was suggestive evidence of 1-standard deviation increase in total testosterone levels being associated with a lower risk of lung non-adenocarcinoma (hazard ratio 0.60, 95% confidence interval 0.37–0.98) in the HUNT Study. However, this was not confirmed by using data from a larger consortium. In general, we did not find convincing evidence to support a causal role of sex hormones on risk of lung and colorectal cancers in women of European ancestry.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-75305-4.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Estradiol, HUNT, Lung cancer, Mendelian randomization, Sex hormones

Subject terms: Cancer epidemiology, Lung cancer, Colorectal cancer, Endocrinology, Epidemiology, Genetics research

Introduction

Lung and colorectal cancers are among the most common cancers in women1. Morbidity and mortality of lung cancer have decreased in men but increased among women in many developed countries1. Even though a great proportion of the sex difference can reflect changes in smoking habits, factors specific to women may play an important role2. All major histologic types of lung cancer are associated with smoking, the association being stronger for small-cell lung cancer than for lung adenocarcinoma3. Besides, around 20% of lung cancers in European females are not attributable to smoking, and lung adenocarcinoma is the most common histologic type among these women4. Unlike lung cancer, there is no single risk factor accounting for the majority of colorectal cancer cases1.

Sex hormones have been suggested to contribute to both cancers5,6. Both normal and cancerous lung and colonic cells contain estrogen receptors α and β5,7,8. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) found that the use of estrogen plus progestin may confer a protective role against the development of colorectal cancer, particularly colon cancer, in postmenopausal women9,10, while estrogen plus progestin may increase lung cancer mortality11. Moreover, endogenous estrogen, such as estradiol, may stimulate cellular proliferation and promote lung tumor growth5. Recent prospective cohort studies conducted in UK Biobank reported no association between total testosterone and colorectal cancer in women12–14, whereas bioavailable testosterone was found to be a protective factor for colorectal cancer in a cohort study of postmenopausal women13. While most of the discussion on sex hormones and lung cancer has been focused on the role of estrogen, several studies reported the presence of androgen receptor in the lung and its role in promoting lung cancer development15. Conversely, a recent case-control study suggested higher levels of bioavailable testosterone to be associated with a reduced risk of lung cancer in 397 case-control pairs of postmenopausal never-smoking women16. However, the sample size of this study was too small to draw any convincing conclusions. Sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), the protein responsible for binding and transporting sex hormones in the bloodstream, influences their action in target tissues by regulating their bioavailability. Only 1–2% of sex hormones are unbound and therefore bioavailable17. SHBG was not associated with colorectal cancer among women in the recent meta-analysis18. Overall, results from conventional epidemiological studies investigating the associations of sex hormones with lung and colorectal tumorigenesis are conflicting.

Mendelian randomization (MR) is an analytical method using genetic variants as instrumental variables for an exposure to investigate a potential causal relationship between this exposure and an outcome19. This approach attempts to overcome limitations of conventional observational studies, such as reverse causation and confounding, by using genetic variants that are randomly distributed at conception20. The statistical power and precision of MR studies may be enhanced by using two-sample MR, where genetic variant-exposure and genetic variant-outcome associations are derived from independent samples and combined to obtain the causal effect of the exposure on the outcome19,21. Several MR analyses suggested causal effects of sex hormones on various diseases22,23. For instance, Schmitz et al. estimated a causal effect of high estradiol levels on increased bone mineral density in women22. Ruth et al. found evidence that higher testosterone had adverse effects on breast and endometrial cancers but reduced the risk of ovarian cancer, while SHBG had a protective effect on endometrial cancer23. However, few MR studies have investigated the role of sex hormones on risk of lung and colorectal cancers. Larsson et al. did not find an association between genetically predicted estradiol levels and risk of lung and colorectal cancers in women24. Two other recent MR studies reported that estradiol, total testosterone, bioavailable testosterone, and SHBG were unrelated to colorectal cancer14,25. Nevertheless, these MR studies either did not analyze subtypes of lung cancer or subsites of colorectal cancer or did not have access to outcomes data for women specifically.

In this study, we aimed to apply two-sample MR analysis to investigate the potential causal relationships between endogenous estradiol, bioavailable testosterone, total testosterone, SHBG and risk of lung and colorectal cancers in women of European ancestry: in The Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT) in Norway, the International Lung Cancer Consortium (ILCCO), FinnGen and three large consortia of colorectal cancer.

Results

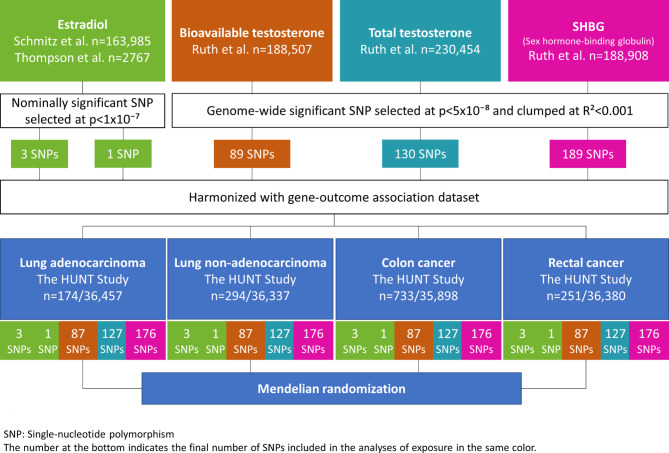

From publicly available data of genome-wide association studies (GWASs), we derived genetic instruments specific to women for sex hormones, including endogenous estradiol, bioavailable testosterone, total testosterone and SHBG. These consisted of two sets of genetic instruments for endogenous estradiol: respectively, three and one single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). The genetic instruments for bioavailable testosterone, total testosterone and SHBG levels comprised 89, 130 and 189 SNPs, respectively. Summary statistics for the associations of genetic variants of sex hormones with lung and colorectal cancers were generated in 36,631 women from the HUNT Study (Fig. 1). We performed additional MR analyses using the ILCCO, FinnGen and three large consortia of colorectal cancer data (Supplementary Fig. 1). Further details on study cohorts are provided in Supplementary Table S126.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of study methodology.

Table 1 presents the characteristics of women from the HUNT Study. Among the 36,631 women, 468 women had lung cancer including 174 lung adenocarcinoma and 294 lung non-adenocarcinoma, 733 had colon cancer and 251 rectal cancer. The mean age was 47.6 years, with 51.7% being ever smokers and 77.9% being ever passive smokers.

Table 1.

Characteristics of women with complete information on genetic data in HUNT2 and HUNT3.

| Variables | |

|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 36,631 |

| Age (years) | 47.6 ± 17.1 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.6 ± 4.7 |

| Number of lung cancer cases (%) | 468 (1.3) |

| Lung adenocarcinoma cases (%) | 174 (0.5) |

| Lung non-adenocarcinoma cases (%) | 294 (0.8) |

| Number of colorectal cancer cases (%) | 984 (2.7) |

| Colon cases (%) | 733 (2.0) |

| Rectal cases (%) | 251 (0.7) |

| Smoking status, % (never/ever/unknown) | 46.6/51.7/1.7 |

| Passive smoking, % (never/ever/unknown) | 21.1/77.9/1.1 |

| Alcohol consumption, % (never/ever/unknown) | 35.3/60.9/3.8 |

| Physical activity, % (inactive/active/unknown) | 21.7/49.1/29.2 |

| Total sitting time daily (hours), % (0–7/≥8/unknown) | 59.2/26.5/14.3 |

| Family history of cancer, % (no/yes/unknown) | 71.6/27.7/0.7 |

| Reported COPD, % (no/yes) | 98.1/1.9 |

| History of diabetes, % (no/yes/unknown) | 96.8/3.1/0.1 |

Data are given as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables. Information on lifestyle factors were derived from questionnaires in HUNT. If women participated in both HUNT2 and HUNT3 surveys, data were retrieved from HUNT2 if available.

BMI body mass index, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

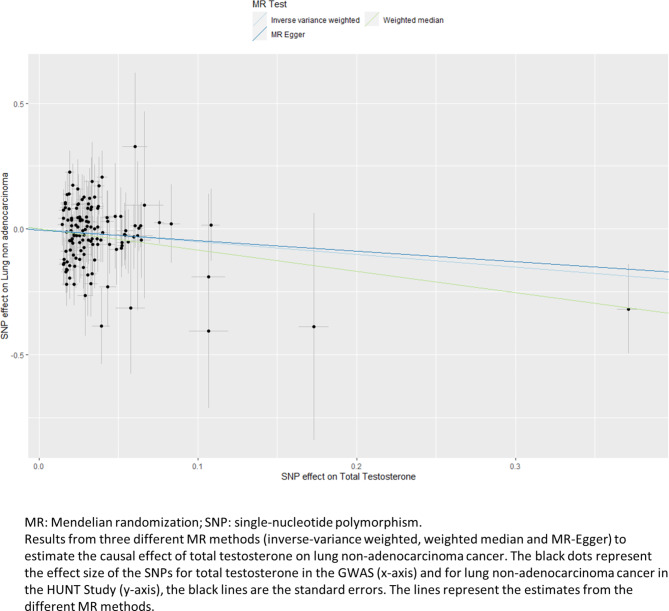

In the MR analysis using SNP-outcome association from HUNT, the two datasets were harmonized, leaving 3 SNPs and 1 SNP for estradiol, 87 SNPs for bioavailable testosterone analyses, 127 SNPs for total testosterone analyses and 176 SNPs for SHBG analyses (Fig. 1). There were five genetic instruments in total. The genetic instruments for estradiol—proxied by 3 SNPs and 1 SNP—had a combined R2-value of 0.1% and 1.0% and a F-statistic of 30.3 and 28.4, respectively. The genetic instruments for bioavailable testosterone, total testosterone and SHBG had a combined R2-value of 4.0%, 6.4% and 12.8%, and a F-statistic of 87.6, 120.6 and 146.3, respectively. As presented in Table 2, higher estradiol levels proxied by our first genetic instrument of 3 SNPs was associated with a decreased risk of colon cancer (hazard ratio (HR) 0.38, 95% CI 0.16–0.88) based on the IVW method. Likewise, genetic predisposition to higher bioavailable testosterone was associated with a decreased risk for lung non-adenocarcinoma (HR 0.47, 95% CI 0.23–0.96, Table 3). However, the MR estimates using the weighted median method did not support the estradiol-colon cancer and bioavailable testosterone-lung non-adenocarcinoma associations, with much wider 95% CIs (HR 0.61, 95% CI 0.19–1.92 and HR 0.45, 95% CI 0.13–1.58, respectively, Table 4). Genetically predisposed higher level of total testosterone was associated with a decreased risk of lung non-adenocarcinoma (HR 0.60, 95% CI 0.37–0.98), it was supported by the weighted median method (HR 0.43, 95% CI 0.19–0.95). The MR-Egger method showed the same direction of result but did not reach statistical significance (Table 4). Figure 2 displays the scatter plot of genetic association between total testosterone and lung non-adenocarcinoma using the three methods. The result from leave-one-out analysis did not suggest that the effect of total testosterone on risk of lung non-adenocarcinoma was disproportionally influenced by a single SNP (Supplementary Fig. 2)26. Nevertheless, none of the above reported associations held for multiple testing (p-value = 0.05/4 (number of sex hormones) = 0.0125). The p-values for MR-Egger intercepts and Q-statistics were above 0.05 (Table 4), suggesting no strong evidence of horizontal pleiotropy or heterogeneity for the associations described.

Table 2.

Mendelian randomization estimates for the association of estradiol level using 3-SNPs with risk of lung or colorectal cancer among women in HUNT.

| Cases | Estradiola | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRb (95% CI) | p-value | Q-statistic | p of Q-statistic | ||

| Lung cancer | 468 | 0.78 (0.28–2.18) | 0.64 | 10 | 0.008 |

| Lung adenocarcinoma | 174 | 0.52 (0.09–2.87) | 0.45 | 3 | 0.27 |

| Lung non-adenocarcinoma | 294 | 1.00 (0.28–3.63) | 1.00 | 7 | 0.03 |

| Colorectal cancer | 984 | 0.53 (0.26–1.08) | 0.08 | 2 | 0.38 |

| Colon cancer | 733 | 0.38 (0.16–0.88) | 0.02 | 3 | 0.20 |

| Rectal cancer | 251 | 1.32 (0.32–5.34) | 0.70 | 2 | 0.43 |

CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio, IVW inverse-variance weighted, MR Mendelian randomization, SD standard deviation.

aTwo-sample MR was performed using data on 3-SNPs (rs4764934, rs897797, rs16991615) from Schmitz22 for estradiol level and from HUNT for lung or colorectal cancer.

b Per one-SD increase in genetically predicted rank-transformed estradiol level, based on the IVW method.

Table 3.

Mendelian randomization estimates for the association of bioavailable and total testosterone levels with risk of lung or colorectal cancer among women in HUNT.

| Cases | Bioavailable testosteronea | Total testosteroneb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRc (95% CI) | p-value | Q-statistic | p of Q-statistic | HRd (95% CI) | p-value | Q-statistic | p of Q-statistic | ||

| Lung cancer | 468 | 0.64 (0.36–1.14) | 0.13 | 61 | 0.98 | 0.72 (0.50–1.05) | 0.09 | 103 | 0.94 |

| Lung adenocarcinoma | 174 | 1.07 (0.41–2.79) | 0.88 | 62 | 0.98 | 0.96 (0.51–1.80) | 0.91 | 106 | 0.91 |

| Lung non-adenocarcinoma | 294 | 0.47 (0.23–0.96) | 0.04 | 85 | 0.52 | 0.60 (0.37–0.98) | 0.04 | 136 | 0.26 |

| Colorectal cancer | 984 | 0.90 (0.60–1.34) | 0.60 | 80 | 0.66 | 0.94 (0.72–1.23) | 0.67 | 119 | 0.67 |

| Colon cancer | 733 | 0.97 (0.61–1.54) | 0.88 | 66 | 0.95 | 0.95 (0.70–1.29) | 0.73 | 96 | 0.98 |

| Rectal cancer | 251 | 0.68 (0.28–1.64) | 0.39 | 105 | 0.08 | 0.89 (0.50–1.59) | 0.69 | 158 | 0.03 |

CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio, IVW inverse-variance weighted, MR Mendelian randomization, SD standard deviation.

aTwo-sample MR was performed using summary statistics from Ruth23 for bioavailable testosterone level and from HUNT for lung or colorectal cancer.

bTwo-sample MR was performed using summary statistics from Ruth23 for total testosterone level and from HUNT for lung or colorectal cancer.

cPer one-SD increase in genetically predicted bioavailable testosterone level, based on the IVW method.

dPer one-SD increase in genetically predicted total testosterone level, based on the IVW method.

Table 4.

Mendelian randomization estimates and sensitivity analyses for the results in HUNT.

| Method | Estradiol levela on colon cancer | Bioavailable testosteroneb on lung non-adenocarcinoma | Total testosteronec on lung non-adenocarcinoma | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRd (95% CI) | p-value | Q-statistic/ p-value |

HRe (95% CI) | p-value | Q-statistic/ p-value |

HRf (95% CI) | p-value | Q-statistic/ p-value |

|

| IVW | 0.38 (0.16–0.88) | 0.02 | 3.25/0.20 | 0.47 (0.23–0.96) | 0.04 | 84.55/0.52 | 0.60 (0.37–0.98) | 0.04 | 136.62/0.26 |

| Weighted median | 0.61 (0.19–1.92) | 0.40 | 0.45 (0.13–1.58) | 0.21 | 0.43 (0.19–0.95) | 0.04 | |||

| MR-Egger | 4.73 (0.16–140.73) | 0.37 | 1.00/0.32 | 0.38 (0.10–1.37) | 0.14 | 84.40/0.50 | 0.66 (0.29–1.48) | 0.31 | 135.55/0.24 |

| MR-Egger intercept | -0.22 (-0.51–0.07) | 0.13 | 0.008 (-0.03–0.05) | 0.70 | -0.004 (-0.04–0.03) | 0.79 | |||

CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio, IVW inverse-variance weighted, SD standard deviation, SNP single-nucleotide polymorphism.

a3 SNPs/b87 SNPs/c127 SNPs were used as instrumental variables for estradiol level22, bioavailable and total testosterone23, respectively.

dPer one-SD increase in genetically predicted rank-transformed estradiol level.

ePer one-SD increase in genetically predicted bioavailable testosterone level.

fPer one-SD increase in genetically predicted total testosterone level.

Fig. 2.

Scatter plot of genetic association between total testosterone and lung non-adenocarcinoma in HUNT.

Genetically predicted SHBG levels were not associated with the studied cancer types (Table 5). The rs727479 SNP, used as the second genetic instrument for estradiol levels, was not associated with lung and colorectal cancers (Supplementary Table S2)26. In addition, we found several SNPs associated with more than one sex hormone, cholesterol, body mass index, height, and alcohol consumption.

Table 5.

Mendelian randomization estimates for the association of SHBG level with risk of lung or colorectal cancer among women in HUNT.

| Cases | SHBGa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRb (95% CI) | p-value | Q-statistic | p of Q-statistic | ||

| Lung cancer | 468 | 1.44 (0.71–2.90) | 0.31 | 184 | 0.31 |

| Lung adenocarcinoma | 174 | 1.04 (0.34–3.21) | 0.95 | 177 | 0.44 |

| Lung non-adenocarcinoma | 294 | 1.73 (0.70–4.25) | 0.23 | 190 | 0.20 |

| Colorectal cancer | 971 | 1.14 (0.70–1.84) | 0.60 | 179 | 0.40 |

| Colon cancer | 723 | 1.26 (0.73–2.19) | 0.41 | 175 | 0.49 |

| Rectal cancer | 248 | 0.87 (0.34–2.27) | 0.78 | 181 | 0.37 |

CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio, IVW inverse-variance weighted, MR Mendelian randomization, SD standard deviation, SHBG sex hormone binding globulin.

aTwo-sample MR was performed using summary statistics from Ruth23 for SHBG level and from HUNT for lung or colorectal cancer.

bAdjusted for body mass index, per one-SD increase in genetically predicted SHBG level, based on the IVW method.

In our additional analyses using larger datasets such as ILCCO (sex-stratified), FinnGen (sex-combined) and the three colorectal cancer consortia (GECCO, CCFR and CORECT) (sex-stratified), we did not find supportive evidence for associations of sex hormones with risk of lung and colorectal cancers (Supplementary Tables S3-S5 and Supplementary Fig. 3)26. The only borderline association was between bioavailable testosterone and rectal cancer in the three consortia (HR 1.26, 95% CI 1.00–1.59), but the meta-analysis of the MR estimates from HUNT, FinnGen and the three consortia did not support this association (HR 1.04, 95% CI 0.76–1.41) (Supplementary Fig. 3)26. The p-values for the Q statistic indicated evidence of heterogeneity for a few associations such as estradiol, bioavailable or total testosterone and lung adenocarcinoma in ILCCO (Supplementary Tables S3 and S4).

Discussion

In our two-sample MR analysis of the HUNT Study, we found a suggestive causal effect of genetically predicted higher level of total testosterone on a decreased risk of lung non-adenocarcinoma, but this was not supported by results from the larger ILCCO. Overall, our study did not provide convincing evidence for causal associations of sex hormones with risk of lung and colorectal cancers in women of European ancestry.

A limited number of MR studies have explored the potential causal associations between estradiol, bioavailable testosterone, total testosterone and SHBG, and lung and colorectal cancer risks in women14,24,25. Similar to the MR study of Larsson et al. investigating the effect of estradiol on lung cancer in 198,825 women in UK Biobank24, we did not find evidence of a causal association. To our knowledge, the only MR study investigating the causal effect of testosterone on lung cancer was performed among men27. In this study, Chang et al. reported no causal association of bioavailable testosterone and total testosterone with lung cancer risk in men27. Nevertheless, effects of sex hormones are heterogenous between males and females22 and may vary among lung cancer subtypes.

The recent study by Dimou et al. combined both observational analyses including 333,530 participants from the UK Biobank and MR analyses using the same GWAS for sex hormones14. They did not find causal associations of bioavailable testosterone and SHBG concentrations with colorectal cancer risk14. Although they identified a positive causal association between total testosterone and colorectal cancer in women (IVW: OR 1.09, 95% CI 1.01–1.17), this was not confirmed by their sensitivity analysis (Weighted median: OR 1.08, 95% CI 0.94–1.25)14. This supported the null findings in our MR study. Similarly, prospective cohort studies conducted in UK Biobank by Peila et al. and McMenamin et al. did not report any associations between total testosterone or SHBG and colorectal cancer in women12,13, even though McMenamin et al. found a protective effect of bioavailable testosterone on colorectal cancer in postmenopausal women13. Traditional observational studies may be more prone to confounding than MR studies.

A meta-analysis including four RCTs, eight cohort and eight case-control studies reported evidence of a protective role of estrogen therapy (RR: 0.79, 95% CI: 0.69–0.91) and combined estrogen-progestogen therapy (RR: 0.74, 95% CI: 0.68–0.81) on colorectal cancer10. Our findings did not support an association between genetically predicted estradiol levels and colorectal cancer risk in women, similarly to the MR studies of Larsson et al.24 and Cornish et al.25. The inconsistent findings in RCT and MR studies suggest that endogenous and exogenous estrogen may exert different effects on colorectal cancer risk. We also note that the genetic variants for estradiol levels are weak instruments. Future studies are needed to further investigate the role of endogenous estrogens in the prevention of colorectal cancer.

The current study is a thorough investigation of the causal associations of various sex hormones on risk of lung and colorectal cancer in women of European ancestry. The main strength of our study is the MR design, which reduced potential bias from confounders and reverse causality if the assumptions hold. These assumptions were likely satisfied by selecting genetic variants associated with bioavailable testosterone, total testosterone and SHBG at a genome-wide significance level and by relatively large F-statistics as well as applying multiple MR methods as sensitivity analyses that are more robust to pleiotropy. In addition, we explored the associations of sex hormones with lung and colorectal cancer subtypes, which were not investigated in the previous MR studies24,25. Finally, our study was the first to use sex-stratified genetic summary data from the ILCCO and the three colorectal cancer consortia (GECCO, CCFR and CORECT) to study such associations.

Our study had several limitations. First, the three SNPs used as instruments for estradiol in our study were nominally associated with estradiol levels at a p-value threshold of 1 × 10⁻⁷ in the UK Biobank, in which only a subset of the participants had estradiol levels above the detection limit22. This may result in weak instrument bias for estradiol, as also suggested by the small F-statistics for the two genetic instruments. Null associations in estradiol analyses might be due to lack of a true causal association but might also be due to weak instrument biasand insufficient statistical power to detect small effects. Second, we did not adjust for body mass index in estradiol and testosterone SNPs-outcome associations as we did for SHBG. Body mass index was not adjusted for in the original GWASs for estradiol and testosterone22,23,28. Two-sample MR analysis requires that the same covariates be adjusted for in both the genetic variant-exposure and genetic variant-outcome associations, and arbitrary adjustment of covariates may lead to collider bias19. Third, our genetic instruments included SNPs that overlapped for bioavailable testosterone, total testosterone and SHBG, and were associated with other traits, leading to potential pleiotropy effects. However, we excluded several genetic variants using LD-clumping to ensure independent variants and reduce such pleiotropy issues. In addition, there was no evidence of strong pleiotropy based on the results of Cochran’s Q and MR-Egger tests for our results in the HUNT Study, even though interpretation of MR-Egger estimate and intercept for estradiol levels should be cautious as the instrument comprised only 3 SNPs. Fourth, in our additional two-sample MR analyses, summary statistics for sex hormone SNPs-colorectal cancer associations from FinnGen were not sex-stratified. This could weaken the results as the effects of sex hormones may differ between women and men. However, meta-analysis of results from HUNT and the three colorectal consortia, with sex-specific data, would not make differences in the conclusions (data not presented). Fifth, the sample size and the number of lung and colorectal cancer cases were relatively small in the HUNT Study, making it possible to have a chance finding. To avoid this, our conclusions were drawn based on results from both the HUNT Study and the large consortia data. Finally, our analyses included women of European ancestry, limiting the generalizability of our findings to other ethnic populations.

By using summary statistics from the largest GWASs, the HUNT Study, data from ILCCO, FinnGen, three large consortia of colorectal cancer and multiple MR methods, we did not find convincing evidence for causal associations of estradiol, bioavailable testosterone, total testosterone and SHBG with lung and colorectal cancers in women of European ancestry.

Materials and methods

Genetic instruments

Summary statistics of sex hormones such as estradiol, bioavailable and total testosterone, SHBG were retrieved from available GWASs in women of European ancestry22,23,28, as presented in Supplementary Table S626. For endogenous estradiol levels, we used two sets of genetic instruments. The main instrument consisted of three SNPs previously identified to be associated with estradiol in a recent GWAS conducted in the UK Biobank, including rs4764934, rs16991615 and rs1063810122. Four genetic variants were found to be nominally significant (p-value < 1 × 10−7) in this GWAS of 163,985 women22. Among them, rs45446698 is located close to CYP3A7, a well-known gene involved in metabolizing exogenous hormones29. Therefore, this SNP was not included in our first genetic instrument due to potential pleiotropic effects. The second genetic instrument for estradiol comprised the SNP rs727479 located in CYP19A1 gene. This gene encodes aromatase, an enzyme that converts androgens to estrogens in adipose tissue30. SNP rs727479 appeared to be nominally (p-value < 1 × 10−7) associated with estradiol levels in a GWAS of 2767 postmenopausal women28. The two genetic instruments for estradiol did not include overlapping SNPs.

Genetic instruments for bioavailable testosterone, total testosterone and SHBG levels were selected at genome-wide significant level (p-value < 5 × 10−8) from the largest GWAS to date, conducted in the UK Biobank23. To obtain independent SNPs for our genetic instrument, SNPs in linkage disequilibrium (LD) were pruned with a stricter clumping R2 cut-off 0.001, as performed by Hayes et al.31. The original GWAS identified 180 SNPs for bioavailable testosterone in 188,507 women, 254 SNPs for total testosterone in 230,454 women and 359 SNPs for SHBG in 188,908 women23. Following LD-clumping, the number of SNPs was then reduced to 89, 130 and 189 SNPs for bioavailable testosterone, total testosterone and SHBG, respectively31. Figure 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1 display the flow charts for the study methods, and Supplementary Table S1 provides further details on study cohorts26.

Data sources for lung and colorectal cancers

We used data from the HUNT Study for lung and colorectal cancers. The HUNT Study is a large population-based health study in Norway32. The study enrolled participants aged 20 years or older in four surveys: HUNT1 (1984–1986), HUNT2 (1995–1997), HUNT3 (2006–2008) and HUNT4 (2017–2019). DNA was extracted from blood samples and stored at the HUNT Biobank. Genotyping was performed using Illumina HumanCoreExome arrays: HumanCoreExome12 v1.0 and v1.1 and UM HUNT Biobank v1.033. A strict quality control was performed, and samples were excluded based on specific criteria34. In total, 69,716 genotype samples of European ancestry passed the quality control. Imputation was performed in two rounds, using the Haplotype Reference Consortium (HRC) and the Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine (TOPMed) reference panels33.

For the current study we included 36,631 women from the HUNT2 and/or HUNT3 surveys, after excluding 5313 women who did not have information on genetic variants. As the estradiol-SNP rs10638101 was not genotyped, the proxy rs897797, in perfect LD (R2 = 1.0) with rs10638101, was included. Using the 11-digit personal identification number for all residents, participants’ information was linked to the Cancer Registry of Norway (www.kreftregisteret.no) and diagnoses of lung and colorectal cancers were obtained up to December 31, 2018. The Tenth Revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems codes used for registration of lung, colon and rectal cancers are C33–C34, C18 and C19–C20, respectively. Lung cancer histologic types were classified according to the International Classification of Disease of Oncology35. They were further categorized into two main subtypes: adenocarcinoma and non-adenocarcinoma including all other cell types based on possible difference in etiology4 and the same classification in previous studies36,37 to increase statistical power.

Additionally, we obtained genetic summary statistics data for associations of the hormone-related variants with lung cancer in women of European ancestry from ILCCO (9332 lung cancer cases and 9118 controls)38. Summary data for colorectal cancer were retrieved from FinnGen (4957 colorectal cancer cases and 174,006 controls)39 and a meta-analysis of GWASs involving 44,117 women (20,381 colorectal cancer cases and 23,736 controls) within the Genetics and Epidemiology of Colorectal Cancer Consortium (GECCO), the Colon Cancer Family Registry (CCFR) and the Colorectal Cancer Transdisciplinary Study (CORECT) consortium40. We excluded the UK Biobank participants from the three colorectal cancer consortia to avoid overlap with the datasets used for estimating SNP-sex hormones associations. Sex-stratified data were available from ILCCO and the three colorectal cancer consortia but not from FinnGen. Further information on the contributing studies is presented in Supplementary Table S126.

Two-sample MR analysis

MR analysis relies on three key assumptions as follows, the instrumental variable (i) is strongly associated with the exposure (relevance assumption), (ii) is unrelated to confounding factors of the exposure-outcome relationship (independence assumption) and (iii) only affects the outcome through the exposure (exclusion restriction assumption)19. Here, the first two-sample MR analysis was performed using summary statistics from available GWASs for sex hormones and summary statistics from the HUNT Study for lung and colorectal cancers.

The proportion of variance in each sex hormone explained by the SNPs was estimated by a combined R2-value, and the strength of each instrument was assessed by the F-statistic41. The instrument is considered as valid if F-statistic > 10. We tested for possible pleiotropic association of SNPs with other traits, including potential confounders and mediators, at the genome-wide significance level (p-value < 5 × 10−8) using the Phenoscanner database and the VEP tool (https://www.ensembl.org/Tools/VEP)42. To obtain SNP-outcome associations from the HUNT Study, we generated coefficients (ln(HR)) and standard errors from Cox regression of risk of lung cancer overall, its subtypes (adenocarcinoma and non-adenocarcinoma), colorectal, colon and rectal cancers on each SNP using individual-level data from the HUNT2 and HUNT3 surveys. The models were adjusted for batch and 20 principal components (PCs) to account for population stratification, and additionally adjusted for body mass index for SHBG (in the SNP-outcome and SNP-exposure associations) to be consistent with the adjustment made in the original GWAS by Ruth et al.23. The effect estimates in the exposure and outcome datasets were harmonized to the same effect allele. We applied the inverse-variance weighted (IVW) method41 if the instrument consisted of multiple SNPs or Wald method if it consisted of only one SNP43. An IVW estimate of the causal effect combines the ratio estimates of each genetic variant in a meta-analysis model41. A fixed-effect IVW model assumes that each SNP is a valid instrument, while the random-effect model allows horizontal pleiotropy as long as the pleiotropy is balanced between SNPs44. Sensitivity analyses included weighted median method and MR-Egger method. The weighted median method can give valid MR estimates even if up to 50% of the variants are invalid45. The MR-Egger method gives MR estimates after taking account of pleiotropic effects. To assess presence of horizontal pleiotropy, we calculated intercept and p-value of the intercept of the MR-Egger regression46. We tested for heterogeneity between SNPs using Cochran’s Q statistic for the IVW and MR-Egger methods47. If the p-value for the Q statistic was lower than 0.05, it indicates the presence of heterogeneity and can imply the presence of pleiotropy. Scatter plots were used to visualize consistency between the different methods. Leave-one-out analyses were performed to ascertain that the effect was not driven by a single SNP.

Additionally, we ran two-sample MR analyses using summary statistics from the same GWASs for sex hormones and from large-scale consortia provided by the ILCCO (sex-stratified), FinnGen (sex-combined) and GECCO, CCFR and CORECT (sex-stratified) for lung and colorectal cancers. For colorectal, colon and rectal cancers, the two-sample MR estimates from HUNT, FinnGen and the three colorectal cancer consortia were meta-analyzed using a random-effect model to increase the statistical power of the analyses and obtain an overall estimate. We did not perform meta-analysis of the MR estimates from HUNT and ILCCO for lung cancer as the subtypes were classified differently in the two studies. Statistical analyses were performed in STATA/MP 17 (College Station, TX, USA) and R (version 4.1.3) with packages TwoSampleMR48 and MendelianRandomization49.

The study has been approved by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK South-East 2019/337). All participants signed written informed consent on participation in HUNT, with linkage to previous HUNT surveys and specific registries in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval had also been obtained in the original studies22,23,28,38,39.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT) is a collaboration between the HUNT Research Centre (Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, NTNU, Norwegian University of Science and Technology), Trøndelag County Council, Central Norway Regional Health Authority, and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.The authors acknowledge the participants and investigators of the ILCCO and FinnGen study.ASTERISK: We are very grateful to Dr. Bruno Buecher without whom this project would not have existed. We also thank all those who agreed to participate in this study, including the patients and the healthy control persons, as well as all the physicians, technicians and students.CCFR: The Colon CFR graciously thanks the generous contributions of their study participants, dedication of study staff, and the financial support from the U.S. National Cancer Institute, without which this important registry would not exist. The authors would like to thank the study participants and staff of the Seattle Colon Cancer Family Registry and the Hormones and Colon Cancer study (CORE Studies).CLUE II: We thank the participants of Clue II and appreciate the continued efforts of the staff at the Johns Hopkins George W. Comstock Center for Public Health Research and Prevention in the conduct of the Clue II Cohort Study. Cancer data was provided by the Maryland Cancer Registry, Center for Cancer Prevention and Control, Maryland Department of Health, with funding from the State of Maryland and the Maryland Cigarette Restitution Fund. The collection and availability of cancer registry data is also supported by the Cooperative Agreement NU58DP006333, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Department of Health and Human Services.COLON and NQplus: the authors would like to thank the COLON and NQplus investigators at Wageningen University & Research and the involved clinicians in the participating hospitals.CORSA: We kindly thank all individuals who agreed to participate in the CORSA study. Furthermore, we thank all cooperating physicians and students and the Biobank Graz of the Medical University of Graz.CPS-II: The authors express sincere appreciation to all Cancer Prevention Study-II participants, and to each member of the study and biospecimen management group. The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution to this study from central cancer registries supported through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries and cancer registries supported by the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Program. The authors assume full responsibility for all analyses and interpretation of results. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the American Cancer Society or the American Cancer Society – Cancer Action Network.Czech Republic CCS: We are thankful to all clinicians in major hospitals in the Czech Republic, without whom the study would not be practicable. We are also sincerely grateful to all patients participating in this study.DACHS: We thank all participants and cooperating clinicians, and everyone who provided excellent technical assistance.EDRN: We acknowledge all contributors to the development of the resource at University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Gastroenterology, Department of Pathology, Hepatology and Nutrition and Biomedical Informatics.EPIC: Where authors are identified as personnel of the International Agency for Research on Cancer/World Health Organization, the authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy or views of the International Agency for Research on Cancer/World Health Organization.EPICOLON: We are sincerely grateful to all patients participating in this study who were recruited as part of the EPICOLON project. We acknowledge the Spanish National DNA Bank, Biobank of Hospital Clínic–IDIBAPS and Biobanco Vasco for the availability of the samples. The work was carried out (in part) at the Esther Koplowitz Centre, Barcelona.Harvard cohorts: The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and those of participating registries as required. We acknowledge Channing Division of Network Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital as home of the NHS. The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution to this study from central cancer registries supported through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) and/or the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Central registries may also be supported by state agencies, universities, and cancer centers. Participating central cancer registries include the following: Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Maine, Maryland, Michigan, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Puerto Rico, Rhode Island, Seattle SEER Registry, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia, Wyoming. The authors assume full responsibility for analyses and interpretation of these data.Kentucky: We would like to acknowledge the staff at the Kentucky Cancer Registry.LCCS: We acknowledge the contributions of Jennifer Barrett, Robin Waxman, Gillian Smith and Emma Northwood in conducting this study.NCCCS I & II: We would like to thank the study participants, and the NC Colorectal Cancer Study staff.NSHDS investigators thank the Västerbotten Intervention Programme, the Northern Sweden MONICA study, the Biobank Research Unit at Umeå University and Biobanken Norr at Region Västerbotten for providing data and samples and acknowledge the contribution from Biobank Sweden, supported by the Swedish Research Council. PLCO: The authors thank the PLCO Cancer Screening Trial screening center investigators and the staff from Information Management Services Inc and Westat Inc. Most importantly, we thank the study participants for their contributions that made this study possible. Cancer incidence data have been provided by the District of Columbia Cancer Registry, Georgia Cancer Registry, Hawaii Cancer Registry, Minnesota Cancer Surveillance System, Missouri Cancer Registry, Nevada Central Cancer Registry, Pennsylvania Cancer Registry, Texas Cancer Registry, Virginia Cancer Registry, and Wisconsin Cancer Reporting System. All are supported in part by funds from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, National Program for Central Registries, local states or by the National Cancer Institute, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program. The results reported here and the conclusions derived are the sole responsibility of the authors.SEARCH: We thank the SEARCH teamSELECT: We thank the research and clinical staff at the sites that participated on SELECT study, without whom the trial would not have been successful. We are also grateful to the 35,533 dedicated men who participated in SELECT.WHI: The authors thank the WHI investigators and staff for their dedication, and the study participants for making the program possible. A full listing of WHI investigators can be found at: : https://www-whi-org.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/WHI-Investigator-Long-List.pdf.

Author contributions

MD conducted statistical analyses, interpreted results and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. XMM and YQS contributed to the study design and statistical analyses. YL provided the sex-specific genetic summary data for lung cancer from the ILCCO. DA, ABH, PTC, SK, CIL, EW, JNS and MAJ provided the sex-specific genetic summary data for colorectal cancer from GECCO, CCFR and CORECT. XMM, YQS and BMB contributed to the manuscript writing with important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding information

Open access funding provided by NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology (incl St. Olavs Hospital - Trondheim University Hospital). The project was supported by The Norwegian Cancer Society (project ID 182688-2016) and The Research Council of Norway “Gaveforsterkning”. MD was supported by funding from the Norwegian Women’s Public Health Association (N.K.S.: 40014) and top-up funding from the collaboration partner between St Olav hospital and NTNU, Norwegian University of Science and Technology. YQS was supported by a researcher grant from The Liaison Committee for Education, Research and Innovation in Central Norway (project ID 2018/42794). International Lung Cancer Consortium (ILCCO): Grant 1R21CA235464. Genetics and Epidemiology of Colorectal Cancer Consortium (GECCO): National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (U01 CA137088, R01 CA059045, R01 CA201407. Genotyping/Sequencing services were provided by the Center for Inherited Disease Research (CIDR) contract number HHSN268201200008I. This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA015704. Scientific Computing Infrastructure at Fred Hutch funded by ORIP grant S10OD028685. ASTERISK: a Hospital Clinical Research Program (PHRC-BRD09/C) from the University Hospital Center of Nantes (CHU de Nantes) and supported by the Regional Council of Pays de la Loire, the Groupement des Entreprises Françaises dans la Lutte contre le Cancer (GEFLUC), the Association Anne de Bretagne Génétique and the Ligue Régionale Contre le Cancer (LRCC). The ATBC Study is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the U.S. National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services. CLUE II funding was from the National Cancer Institute (U01 CA086308, Early Detection Research Network; P30 CA006973), National Institute on Aging (U01 AG018033), and the American Institute for Cancer Research. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US government. Cancer data was provided by the Maryland Cancer Registry, Center for Cancer Prevention and Control, Maryland Department of Health, with funding from the State of Maryland and the Maryland Cigarette Restitution Fund. The collection and availability of cancer registry data is also supported by the Cooperative Agreement NU58DP006333, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Department of Health and Human Services. ColoCare: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers R01 CA189184 (Li/Ulrich), U01 CA206110 (Ulrich/Li/Siegel/Figueiredo/Colditz, 2P30CA015704- 40 (Gilliland), R01 CA207371 (Ulrich/Li)), the Matthias Lackas-Foundation, the German Consortium for Translational Cancer Research, and the EU TRANSCAN initiative. The Colon Cancer Family Registry (CCFR, www.coloncfr.org) is supported in part by funding from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), National Institutes of Health (NIH) (award U01 CA167551). Support for case ascertainment was provided in part from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program and the following U.S. state cancer registries: AZ, CO, MN, NC, NH; and by the Victoria Cancer Registry (Australia) and Ontario Cancer Registry (Canada). The CCFR Set-1 (Illumina 1 M/1 M-Duo) and Set-2 (Illumina Omni1-Quad) scans were supported by NIH awards U01 CA122839 and R01 CA143237 (to GC). The CCFR Set-3 (Affymetrix Axiom CORECT Set array) was supported by NIH award U19 CA148107 and R01 CA81488 (to SBG). The CCFR Set-4 (Illumina OncoArray 600 K SNP array) was supported by NIH award U19 CA148107 (to SBG) and by the Center for Inherited Disease Research (CIDR), which is funded by the NIH to the Johns Hopkins University, contract number HHSN268201200008I. Additional funding for the OFCCR/ARCTIC was through award GL201-043 from the Ontario Research Fund (to BWZ), award 112746 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to TJH), through a Cancer Risk Evaluation (CaRE) Program grant from the Canadian Cancer Society (to SG), and through generous support from the Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation. The SFCCR Illumina HumanCytoSNP array was supported in part through NCI/NIH awards U01/U24 CA074794 and R01 CA076366 (to PAN). The content of this manuscript does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the NCI, NIH or any of the collaborating centers in the Colon Cancer Family Registry (CCFR), nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government, any cancer registry, or the CCFR. COLON: The COLON study is sponsored by Wereld Kanker Onderzoek Fonds, including funds from grant 2014/1179 as part of the World Cancer Research Fund International Regular Grant Programme, by Alpe d’Huzes and the Dutch Cancer Society (UM 2012–5653, UW 2013–5927, UW2015-7946), and by TRANSCAN (JTC2012-MetaboCCC, JTC2013-FOCUS). The Nqplus study is sponsored by a ZonMW investment grant (98-10030); by PREVIEW, the project PREVention of diabetes through lifestyle intervention and population studies in Europe and around the World (PREVIEW) project which received funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) under grant no. 312057; by funds from TI Food and Nutrition (cardiovascular health theme), a public–private partnership on precompetitive research in food and nutrition; and by FOODBALL, the Food Biomarker Alliance, a project from JPI Healthy Diet for a Healthy Life. COLO2&3: National Institutes of Health (R01 CA060987). Colorectal Cancer Transdisciplinary (CORECT) Study: The CORECT Study was supported by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (NCI/NIH), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (grant numbers U19 CA148107, R01 CA081488, P30 CA014089, R01 CA197350; P01 CA196569; R01 CA201407; R01 CA242218), National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health (grant number T32 ES013678) and a generous gift from Daniel and Maryann Fong. CORSA: The CORSA study was funded by Austrian Research Funding Agency (FFG) BRIDGE (grant 829675, to Andrea Gsur), the “Herzfelder’sche Familienstiftung” (grant to Andrea Gsur) and was supported by COST Action BM1206. CPS-II: The American Cancer Society funds the creation, maintenance, and updating of the Cancer Prevention Study-II (CPS-II) cohort. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of Emory University, and those of participating registries as required. CRCGEN: Colorectal Cancer Genetics & Genomics, Spanish study was supported by Instituto de Salud Carlos III, co-funded by FEDER funds –a way to build Europe– (grants PI14-613 and PI09-1286), Agency for Management of University and Research Grants (AGAUR) of the Catalan Government (grant 2017SGR723), Junta de Castilla y León (grant LE22A10-2), the Spanish Association Against Cancer (AECC) Scientific Foundation grant GCTRA18022MORE and the Consortium for Biomedical Research in Epidemiology and Public Health (CIBERESP), action Genrisk. Sample collection of this work was supported by the Xarxa de Bancs de Tumors de Catalunya sponsored by Pla Director d’Oncología de Catalunya (XBTC), Plataforma Biobancos PT13/0010/0013 and ICOBIOBANC, sponsored by the Catalan Institute of Oncology. We thank CERCA Programme, Generalitat de Catalunya for institutional support. Czech Republic CCS: This work was supported by the Czech Science Foundation (21-04607X, 21–27902 S), by the Grant Agency of the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic (grants AZV NU21-07-00247 and AZV NU21-03-00145), and Charles University Research Fund (Cooperation 43-Surgical disciplines). DACHS: This work was supported by the German Research Council (BR 1704/6 − 1, BR 1704/6 − 3, BR 1704/6 − 4, CH 117/1–1, HO 5117/2 − 1, HE 5998/2 − 1, KL 2354/3 − 1, RO 2270/8 − 1 and BR 1704/17 − 1), the Interdisciplinary Research Program of the National Center for Tumor Diseases (NCT), Germany, and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (01KH0404, 01ER0814, 01ER0815, 01ER1505A and 01ER1505B). DALS: National Institutes of Health (R01 CA048998 to M. L. Slattery). EDRN: This work is funded and supported by the NCI, EDRN Grant (U01-CA152753). EPIC: The coordination of EPIC is financially supported by International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and also by the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Imperial College London which has additional infrastructure support provided by the NIHR Imperial Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). The national cohorts are supported by: Danish Cancer Society (Denmark); Ligue Contre le Cancer, Institut Gustave Roussy, Mutuelle Générale de l’Education Nationale, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM) (France); German Cancer Aid, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), German Institute of Human Nutrition Potsdam- Rehbruecke (DIfE), Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) (Germany); Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro-AIRC-Italy, Compagnia di SanPaolo and National Research Council (Italy); Dutch Ministry of Public Health, Welfare and Sports (VWS), Netherlands Cancer Registry (NKR), LK Research Funds, Dutch Prevention Funds, Dutch ZON (Zorg Onderzoek Nederland), World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF), Statistics Netherlands (The Netherlands); Health Research Fund (FIS) - Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), Regional Governments of Andalucía, Asturias, Basque Country, Murcia and Navarra, and the Catalan Institute of Oncology - ICO (Spain); Swedish Cancer Society, Swedish Research Council and and Region Skåne and Region Västerbotten (Sweden); Cancer Research UK (14136 to EPIC-Norfolk; C8221/A29017 to EPIC-Oxford), Medical Research Council (1000143 to EPIC-Norfolk; MR/M012190/1 to EPIC-Oxford). (United Kingdom). EPICOLON: This work was supported by grants from Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria/FEDER (PI08/0024, PI08/1276, PS09/02368, P111/00219, PI11/00681, PI14/00173, PI14/00230, PI17/00509, 17/00878, PI20/00113, PI20/00226, Acción Transversal de Cáncer), Xunta de Galicia (PGIDIT07PXIB9101209PR), Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad (SAF07-64873, SAF 2010–19273, SAF2014-54453R), Fundación Científica de la Asociación Española contra el Cáncer (GCB13131592CAST), Beca Grupo de Trabajo “Oncología” AEG (Asociación Española de Gastroenterología), Fundación Privada Olga Torres, FP7 CHIBCHA Consortium, Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca (AGAUR, Generalitat de Catalunya, 2014SGR135, 2014SGR255, 2017SGR21, 2017SGR653), Catalan Tumour Bank Network (Pla Director d’Oncologia, Generalitat de Catalunya), PERIS (SLT002/16/00398, Generalitat de Catalunya), CERCA Programme (Generalitat de Catalunya) and COST Action BM1206 and CA17118. CIBERehd is funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III. ESTHER/VERDI. This work was supported by grants from the Baden-Württemberg Ministry of Science, Research and Arts and the German Cancer Aid. Harvard cohorts: HPFS is supported by the National Institutes of Health (P01 CA055075, UM1 CA167552, U01 CA167552, R01 CA137178, R01 CA151993, and R35 CA197735), NHS by the National Institutes of Health (P01 CA087969, UM1 CA186107, R01 CA137178, R01 CA151993, and R35 CA197735), and PHS by the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA042182). Hawaii Adenoma Study: NCI grants R01 CA072520. HCES-CRC: the Hwasun Cancer Epidemiology Study–Colon and Rectum Cancer (HCES-CRC; grants from Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital, HCRI15011-1). Kentucky: This work was supported by the following grant support: Clinical Investigator Award from Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (CI-8); NCI R01CA136726. LCCS: The Leeds Colorectal Cancer Study was funded by the Food Standards Agency and Cancer Research UK Programme Award (C588/A19167). MCCS cohort recruitment was funded by VicHealth and Cancer Council Victoria. The MCCS was further supported by Australian NHMRC grants 509348, 209057, 251553 and 504711 and by infrastructure provided by Cancer Council Victoria. Cases and their vital status were ascertained through the Victorian Cancer Registry (VCR) and the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), including the National Death Index and the Australian Cancer Database. BMLynch was supported by MCRF18005 from the Victorian Cancer Agency. MEC: National Institutes of Health (R37 CA054281, P01 CA033619, and R01 CA063464). MECC: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (R01 CA081488, R01 CA197350, U19 CA148107, R01 CA242218, and a generous gift from Daniel and Maryann Fong. MSKCC: The work at Sloan Kettering in New York was supported by the Robert and Kate Niehaus Center for Inherited Cancer Genomics and the Romeo Milio Foundation. Moffitt: This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers R01 CA189184, P30 CA076292), Florida Department of Health Bankhead-Coley Grant 09BN-13, and the University of South Florida Oehler Foundation. Moffitt contributions were supported in part by the Total Cancer Care Initiative, Collaborative Data Services Core, and Tissue Core at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, a National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (grant number P30 CA076292). NCCCS I & II: We acknowledge funding support for this project from the National Institutes of Health, R01 CA066635 and P30 DK034987. NFCCR: This work was supported by an Interdisciplinary Health Research Team award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CRT 43821); the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (U01 CA074783); and National Cancer Institute of Canada grants (18223 and 18226). The authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of Alexandre Belisle and the genotyping team of the McGill University and Génome Québec Innovation Centre, Montréal, Canada, for genotyping the Sequenom panel in the NFCCR samples. Funding was provided to Michael O. Woods by the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute. NSHDS: The research was supported by Biobank Sweden through funding from the Swedish Research Council (VR 2017 − 00650, VR 2017 − 01737), the Swedish Cancer Society (CAN 2017/581), Region Västerbotten (VLL-841671, VLL-833291), Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (VLL-765961), and the Lion’s Cancer Research Foundation (several grants) and Insamlingsstiftelsen, both at Umeå University. OSUMC: OCCPI funding was provided by Pelotonia and HNPCC funding was provided by the NCI (CA016058 and CA067941). PLCO: Intramural Research Program of the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics and supported by contracts from the Division of Cancer Prevention, National Cancer Institute, NIH, DHHS. Funding was provided by National Institutes of Health (NIH), Genes, Environment and Health Initiative (GEI) Z01 CP 010200, NIH U01 HG004446, and NIH GEI U01 HG 004438. SEARCH: The University of Cambridge has received salary support in respect of PDPP from the NHS in the East of England through the Clinical Academic Reserve. Cancer Research UK (C490/A16561); the UK National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centres at the University of Cambridge. SELECT: Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers U10 CA037429 (CD Blanke), and UM1 CA182883 (CM Tangen/IM Thompson). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. SMS and REACH: This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (grant P01 CA074184 to J.D.P. and P.A.N., grants R01 CA097325, R03 CA153323, and K05 CA152715 to P.A.N., and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at the National Institutes of Health (grant KL2 TR000421 to A.N.B.-H.). The Swedish Low-risk Colorectal Cancer Study: The study was supported by grants from the Swedish research council; K2015-55X-22674-01-4, K2008-55X-20157-03-3, K2006-72X-20157-01-2 and the Stockholm County Council (ALF project). Swedish Mammography Cohort and Cohort of Swedish Men: This work is supported by the Swedish Research Council /Infrastructure grant, the Swedish Cancer Foundation, and the Karolinska Institute´s Distinguished Professor Award to Alicja Wolk. UK Biobank: This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under Application Number 8614. VITAL: National Institutes of Health (K05 CA154337). WHI: The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services through contracts 75N92021D00001, 75N92021D00002, 75N92021D00003, 75N92021D00004, 75N92021D00005. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The corresponding author had access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Data availability

Data from the HUNT Study that is used in research projects will, when reasonably requested by others, be made available on request to the HUNT Data Access Committee (hunt@medisin.ntnu.no). The HUNT data access information describes the policy regarding data availability (https://www.ntnu.edu/hunt/data).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants gave their informed consent for participation in HUNT. The current study was approved by the Norwegian Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK sør-øst 2019/337). The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclaimer

Data from the Cancer Registry of Norway (CRN) has been used in this publication. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors, and no endorsement by CRN is intended nor should be inferred.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.71(3), 209–249 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fidler-Benaoudia, M. M., Torre, L. A., Bray, F., Ferlay, J. & Jemal, A. Lung cancer incidence in young women vs. young men: A systematic analysis in 40 countries. Int. J. Cancer147(3), 811–819 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khuder, S. A. Effect of cigarette smoking on major histological types of lung cancer: A meta-analysis. Lung Cancer. 31 (2–3), 139–148 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun, S., Schiller, J. H. & Gazdar, A. F. Lung cancer in never smokers—a different disease. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 7 (10), 778–790 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gasperino, J. Gender is a risk factor for lung cancer. Med. Hypotheses. 76 (3), 328–331 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMichael, A. J. & Potter, J. D. Reproduction, endogenous and exogenous sex hormones, and colon cancer: A review and hypothesis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst.65 (6), 1201–1207 (1980). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell-Thompson, M., Lynch, I. J. & Bhardwaj, B. Expression of estrogen receptor (ER) subtypes and ERbeta isoforms in colon cancer. Cancer Res.61 (2), 632–640 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim, V. W. et al. Serum estrogen receptor beta mediated bioactivity correlates with poor outcome in lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer. 85 (2), 293–298 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chlebowski, R. T. et al. Estrogen plus progestin and colorectal cancer in postmenopausal women. N. Engl. J. Med.350(10), 991–1004 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin, K. J., Cheung, W. Y., Lai, J. Y. & Giovannucci, E. L. The effect of estrogen vs. combined estrogen-progestogen therapy on the risk of colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 130 (2), 419–430 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chlebowski, R. T. et al. Estrogen plus progestin and lung cancer: Follow-up of the women’s health initiative randomized trial. Clin. Lung Cancer. 17 (1), 10–7e1 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peila, R., Arthur, R. S. & Rohan, T. E. Sex hormones, SHBG and risk of colon and rectal cancer among men and women in the UK Biobank. Cancer Epidemiol.69, 101831 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McMenamin, Ú. C. et al. Circulating sex hormones are associated with gastric and colorectal cancers but not esophageal adenocarcinoma in the UK Biobank. Am. J. Gastroenterol.116 (3), 522–529 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dimou, N. et al. Circulating levels of testosterone, sex hormone binding globulin and colorectal cancer risk: Observational and mendelian randomization analyses. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev.30 (7), 1336–1348 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang, C., Lee, S. O., Yeh, S. & Chang, T. M. Androgen receptor (AR) differential roles in hormone-related tumors including prostate, bladder, kidney, lung, breast and liver. Oncogene. 33 (25), 3225–3234 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao, Y. et al. Endogenous sex hormones, aromatase activity and lung cancer risk in postmenopausal never-smoking women. Int. J. Cancer. 151 (5), 699–707 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coviello, A. D. et al. A genome-wide association meta-analysis of circulating sex hormone-binding globulin reveals multiple loci implicated in sex steroid hormone regulation. PLoS Genet.8 (7), e1002805 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu, Z. et al. Circulating sex hormone levels and risk of gastrointestinal cancer: Systematic review and Meta-analysis of prospective studies. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev.32 (7), 936–946 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies, N. M., Holmes, M. V. & Davey Smith, G. Reading mendelian randomisation studies: A guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians. BMJ. 362, k601 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawlor, D. A., Harbord, R. M., Sterne, J. A., Timpson, N. & Davey Smith, G. Mendelian randomization: Using genes as instruments for making causal inferences in epidemiology. Stat. Med.27 (8), 1133–1163 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pierce, B. L. & Burgess, S. Efficient design for mendelian randomization studies: Subsample and 2-sample instrumental variable estimators. Am. J. Epidemiol.178 (7), 1177–1184 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmitz, D. et al. Genome-wide association study of estradiol levels and the causal effect of estradiol on bone mineral density. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab.106 (11), e4471–e86 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruth, K. S. et al. Using human genetics to understand the disease impacts of testosterone in men and women. Nat. Med.26 (2), 252–258 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larsson, S. C. et al. Serum estradiol and 20 site-specific cancers in women: Mendelian randomization study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab.107 (2), e467–e74 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cornish, A. J. et al. Modifiable pathways for colorectal cancer: A mendelian randomisation analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol.5 (1), 55–62 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Denos, M. et al. Supplementary material for Sex hormones and risk of lung and colorectal cancers in women: A Mendelian randomization study: Zenodo; Deposited 27 October 2023 [ 10.5281/zenodo.10046866

- 27.Chang, J. et al. Genetically predicted testosterone and cancers risk in men: A two-sample mendelian randomization study. J. Transl Med.20 (1), 573 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thompson, D. J. et al. CYP19A1 fine-mapping and mendelian randomization: Estradiol is causal for endometrial cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 23 (2), 77–91 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohmori, S. et al. Differential catalytic properties in metabolism of endogenous and exogenous substrates among CYP3A enzymes expressed in COS-7 cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj.1380 (3), 297–304 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sohl, C. D. & Guengerich, F. P. Kinetic analysis of the three-step steroid aromatase reaction of human cytochrome P450 19A1. J. Biol. Chem.285 (23), 17734–17743 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayes, B. L. et al. Do sex hormones confound or mediate the effect of chronotype on breast and prostate cancer? A mendelian randomization study. PLoS Genet.18 (1), e1009887 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krokstad, S. et al. Cohort profile: The HUNT study, Norway. Int. J. Epidemiol.42 (4), 968–977 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brumpton, B. M. et al. The HUNT study: A population-based cohort for genetic research. Cell. Genom. 2 (10), 100193 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo, Y. et al. Illumina human exome genotyping array clustering and quality control. Nat. Protoc.9 (11), 2643–2662 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O) 3rd edn (World Health Organization, 2013).

- 36.Denos, M. et al. Reproductive factors in relation to incidence of lung and colorectal cancers in a cohort of Norwegian women: The HUNT study. J. Endocr. Soc.7 (1), bvac175 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kabat, G. C., Miller, A. B. & Rohan, T. E. Reproductive and hormonal factors and risk of lung cancer in women: A prospective cohort study. Int. J. Cancer. 120 (10), 2214–2220 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li, Y. et al. Genome-wide interaction analysis identified low-frequency variants with sex disparity in lung cancer risk. Hum. Mol. Genet.31 (16), 2831–2843 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kurki, M. I. et al. FinnGen provides genetic insights from a well-phenotyped isolated population. Nature. 613 (7944), 508–518 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fernandez-Rozadilla, C. et al. Deciphering colorectal cancer genetics through multi-omic analysis of 100,204 cases and 154,587 controls of European and east Asian ancestries. Nat. Genet.55 (1), 89–99 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burgess, S., Butterworth, A. & Thompson, S. G. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genet. Epidemiol.37 (7), 658–665 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kamat, M. A. et al. PhenoScanner V2: An expanded tool for searching human genotype-phenotype associations. Bioinformatics. 35 (22), 4851–4853 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burgess, S., Small, D. S. & Thompson, S. G. A review of instrumental variable estimators for mendelian randomization. Stat. Methods Med. Res.26 (5), 2333–2355 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lawlor, D. A. et al. A mendelian randomization dictionary: Useful definitions and descriptions for undertaking, understanding and interpreting mendelian randomization studies. (2019).

- 45.Bowden, J., Davey Smith, G., Haycock, P. C. & Burgess, S. Consistent estimation in mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet. Epidemiol.40 (4), 304–314 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bowden, J., Davey Smith, G. & Burgess, S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: Effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int. J. Epidemiol.44 (2), 512–525 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Greco, M. F., Minelli, C., Sheehan, N. A. & Thompson, J. R. Detecting pleiotropy in mendelian randomisation studies with summary data and a continuous outcome. Stat. Med.34 (21), 2926–2940 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hemani, G. et al. The MR-base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. eLife. 7, e34408 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Broadbent, J. R. et al. MendelianRandomization v0.5.0: Updates to an R package for performing mendelian randomization analyses using summarized data. Wellcome Open. Res.5, 252 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data from the HUNT Study that is used in research projects will, when reasonably requested by others, be made available on request to the HUNT Data Access Committee (hunt@medisin.ntnu.no). The HUNT data access information describes the policy regarding data availability (https://www.ntnu.edu/hunt/data).