Abstract

Nanotechnology is becoming a promise for scientific advancement nowadays in areas like medicine, consumer products, energy, materials, and manufacturing. Copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO NPs) were synthesized using Ocimum lamiifolium Hochst. ex Benth and Withana somnifera (L) Dunal leaf extract via green synthetic pathway. The leaf of O. lamiifolium and W. somnifera were known to have strong antibiotic and antioxidant properties arising due to the presence of various secondary metabolites, including, flavonoids, alkaloids, saponins, tannins, cardiac glycosides, and phenolic compounds which serve as reducing, stabilizing, and capping agents for the CuO-Nanoparticles (NPs) synthesized. The biosynthesized CuO NPs were characterized based on Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction spectroscopy, and scanning electron microscopy. O. lamiifolium and W. somnifera leaf extract mediated synthesis could produce CuO NPs with average crystallite size of 15 nm and 19 nm, respectively. The biosynthesized CuO-NPs were further examined for antibacterial activity with Gram-positive (S. aureus) and Gram-negative bacteria (E. coli and P. aeruginosa). The GZDK-CuO NPs synthesized using W. somnifera leaf extract inhibited the growth of E. coli. and P. aeruginosa largely in comparison to S. aureus. Whereas the DMAZ-CuO NPs synthesized with the help of O. lamiifolium leaf extract showed higher bacterial inhibition on E. coli compared to S. aureus and P. aeruginosa. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of both types of NPs are also assessed on all three pathogens. The newly biosynthesized nanoparticles, thus, were found to be optional materials for inhibiting the growth of drug- resistant bacterial pathogens.

Keywords: Nanotechnology, Green synthesis, Phytochemicals, Antibacterial activity

Subject terms: Microbiology, Chemistry, Nanoscience and technology

Introduction

Nanotechnology has vast applications across industries like chemical, pharmaceutical, mechanical, and food processing1. It enhances human living standards by contributing to energy efficiency, climate change mitigation, and health improvements, with potential cures for diseases such as cancer and Alzheimer’s2–4. Metal oxide nanoparticles of zinc, copper, iron, and cerium oxide are notable for their unique properties55–7.

Nanomaterials exhibit distinct activities compared to their bulk counterparts due to their size and shape-dependent properties8. Their use in catalysis has led to the synthesis of various functionalized nanoparticles, including metal oxide nanostructures, which are vital for environmental remediation and pollution management9,10. Defined as particles ranging from 1 to 100 nm, nanoparticles possess unique chemical, biological, and physical properties11,12. They can transform poorly absorbed or unstable biological substances into effective solutions, revolutionizing drug delivery systems and materials science13,14.

Bacterial drug resistance presents a worldwide challenge, with researchers actively seeking novel methods to address this issue15,16. One promising strategy is the synthesis of nanoparticles, particularly copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO-NPs), using plant extracts17–22. These bioengineered CuO-NPs offer sustainable, efficient, and biocompatible solutions for healthcare and environmental protection23–25.

Extracts of O. lamiifolium26,27 and W. sominfera28,29 have been reported to exhibit significant antibacterial effects. However, studies on the synthesis of CuO nanoparticles using the leaf extract of O. lamiifolium or W. sominfera, and their synergistic effects on bacterial pathogens, are limited. In this study, CuO-NPs were synthesized using aqueous leaf extracts from O. lamiifolium and W. somnifera, characterized, and tested for antibacterial activity. Using aqueous leaf extracts of O. lamiifolium and W. somnifera for synthesizing CuO-NPs is an eco-friendly approach avoiding the use of harmful solvents and chemicals30,31. Investigating the synergistic effects of CuO-NPs with the antibacterial properties of the plant extracts could also enhance the overall antibacterial efficacy32.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

The chemicals and reagents used in this study are diluted ammonia (NH3), Copper (II) nitrate trihydrate (CuNO3.3H2O, Sigma–Aldrich), ferric chloride (FeCl3, Sigma–Aldrich), acetic acid (CH3COOH, Sigma–Aldrich), concentrated Sulfuric acid (H2SO4, Merck), chloroform (CHCl3, Sigma–Aldrich), Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma–Aldrich), Mueller Hinton Agar (Merck), and bacterial strains(S. aureus, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa), fresh leaf of O. lamiifolium and W somnifera collected from Central Ethiopia Regional State. All chemicals are used as purchased, and no further purifications.

Preparation of W. sominfria and O. lamiifolium leaf extracts

The leaves of W.sominfria and O.lamiifolium was collected from Kambata Tambaro Zone (Dega kedida and Azedebeo areas of Central Ethiopia Regional State) in January 2023. The plant materials were identified at the Herbarium of the Department of Biology, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia. The leaf extraction was performed by a slight modification of the procedure explained in the literature33. The leaves were washed with distilled water to remove dust particles, shade-dried for about two week, and then crushed in to fine powder. W. somnifera and O.lamiifolium leaf extracts, 2% (w/v), were prepared by placing 10 g of plant leaf powder into a 500 mL beaker along with 400 mLof deionized water and then shaken with a mechanical shaker for 30 min and allowed to warm at 50 oC for 1 h on a magnetic stirrer. The extracts were then allowed to cool down at room temperature overnight. The plant filtrates were filtered by using filter paper (Wathman No. 1) and stored at 4 oC for other experiments.

Phytochemical assessment of W. sominfria and O. lamiifolium aqueous extracts

The two traditional plant leaves which are collected from the Kembata Tembaro zone of Central Ethiopia Regional State (specifically from two target sites namely Azedabo and Dega Kedida) were tested for the presence of secondary metabolites such as tannins, alkaloids, saponins, flavonoids, cardiac glycosides and phenolic compounds based on the methods described.

Test for tannins

A few drop of 0.1% FeCl3 was added to 5 mL plant leaf extract. Formation of brownish green or blue black color indicated the presence of tannins34,35.

Test for alkaloids

To about 5 mL of the plant leaf extract, 2 mL of dilute NH3 was added. Then 5 mL of chloroform was also added and shaken gently. The chloroform layer was extracted with 10 mL of acetic acid. Development of a cream with Mayer’s reagent approved the existence of alkaloids36.

Test for saponins

Three milliliters (3 mL) of plant leaf extract were added to 5 mL of distilled water in a test tube, and the mixture was vigorously shaken. The formation of a froth seen for 30 min approves the existence of saponins in the extract37,38.

Test for flavonoids

To a portion of an aqueous leaf extract of the each of powdered plant materials, about 5 mL of dilute ammonia solution was added followed by the addition of concentrated Sulphuric acid (1 mL) addition. The formation of yellow colorations that vanished on standing showed the existence of flavonoids39.

Test for cardiac glycosides

2 mL of aqueous plant leaf extract, 1 mL of acetic acid, and 1–2 drops of 0.1% FeCl3 were added followed by the addition of 1 mL of concentrated H2SO4. The appearance of a brown ring at the interface indicated the existence of cardiac glycosides. A violet ring also appeared under the brown ring endorsing the existence of cardiac glycosides in the leaf extract40.

Test for phenolics

1 mL of 1% FeCl3 solution was transferred to two milliliters of aqueous plant leaf extract. The blue color appeared after about one minute indicative of the presence of phenol40.

Biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticle, CuO-NPs

The procedure for the biosynthesis of Copper Oxide nanoparticles, CuO-NPs was adopted from literature1,20,41. A 0.25 M aqueous copper nitrate solution was prepared and stored in a brown bottle. 125 mL of plant leaf powder extract (Fig. 1) was mixed with 500 mL of 0.25 M of copper nitrate solution in a 1:4 ratio. Then the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 24 h. The color change was checked periodically after 30 min of duration. The formation of greenish brown visually showed the realization of copper oxide nanoparticles. The liquid part removed after centrifugation and the remaining residue washed with deionized water. Then after, the product dried out in an oven at 70 oC for 24 h to remove all the impurities. The resultant black powder stored in an airtight vial for characterization and test of its efficiency in inhibiting the growth of three kinds of pathogens.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram showing the synthesis of CuO NPs from W. somnifera (L) Dunal and O.lamiifolium Hochest.ex.Benth aqueous leaf extract, characterization, and use in antibacterial activity.

Characterization of synthesized copper oxide nanoparticle, CuO-NPs

The crystallinity of the synthesized CuO-NPs was characterized by employing an X-ray diffractometer (XRD-7000, Shimadzu Co., Japan) equipped with a Cu target for generating Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54056 Å). XRD spectra were verified from 10° to 80° with 2θ angles using Cu Kα radiation operated at 40 kV and 30 mA. The average size of NPs were calculated using Debye–Scherrer formulae from the full width at half maxima of the peaks in the XRD patterns.

|

Where, K is Scherrer’s constant (K = 0.94), λ = Wavelength of X-rays (1.54056 Å), FWHM = full width at half maxima of the peaks, and θ = Peak position in XRD graph. FTIR spectra were obtained using a spectrophotometer (Thermo Fischer scientific Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, i50abx, USA) in the spectral region of 4000 –400 cm− 1. The morphology of the synthesized CuO-NPs was characterized by field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, JEOL-JCM 6000 F, made in Japan). The solid-state UV-visible diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (UV-Vis-DRS) analysis was conducted using a UV-3600Plus Series instrument. The optical band gap energy (Eg) of the biosynthesized CuO nanomaterials was estimated using the Tauc plot method using the equation [F(Rꝏ)hv]2 vs. energy. Where F(Rꝏ) is the absorption coefficient, hv is the energy of the photon. The band gap (Eg) is determined by extrapolating the linear segment of the graph to the x-axis.

Antimicrobial activity of DMAZ-CuO and GZDK-CuO NPs

Muller Hinton Agar (ISO-6579) and Nutrient Broth were used during the study. Muller Hinton agar was used for the antimicrobial tests and the nutrient broth was also used for routine stock culture activation. Two gram-negative bacteria; (Escherichia coli ATCC 25722, and Pseudomonas aeriginosa ATCC27853) and one Gram-positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25903) known to cause food-borne bacterial infection were used to evaluate the antimicrobial activity of DMAZ-CuO and GZDK-CuO NPs. The Bacterial strains were reactivated by subculturing on nutrient broth at 37 °C and maintained on nutrient agar slant at 4 °C for further activity. The antibacterial activity of the CuO-NPs was tested against the selected bacterial strains through the agar disc diffusion method described by a literature42. The 24 h plate cultures of 0.5 Mc Farland standard (1 to 2 × 108 CFU mL− 1) bacterial suspensions were uniformly spread on the Mueller-Hinton agar plate (Oxide) to form lawn cultures. The micropipette tip-sized filter paper was soaked with different concentrations of CuO-NPs (10, 20, and 40 µg/mL). Amoxicillin (AMX) was used as a positive control (30 µg/mL) and Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as a negative control (10 µg/mL). The impressed paper was carefully placed on swabbed plates. After incubation for 24 h at 37 °C, the zone of inhibition was measured.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was evaluated for the plant extract-mediated synthesized CuO-NPs. The MIC of both CuO-NPs was determined by using concentrations (10, 5, 2.5, 1.25, and 0.625 µg/mL) of the CuO-NPs by using the broth dilution method4,43. 4 mL of the nutrient broth (NB) was pipetted into each of 6 test tubes. A 0.1 ml of the prepared successive two-fold serial dilutions of the CuO-NPs concentration was mixed with the nutrient broth. Thereafter, 0.1 mL of the standardized inoculum of test bacterium was distributed into each of the test tubes comprising of the suspension of nutrient broth and the CuO-NPs. Then, all test tubes were properly covered and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The MIC value was read as the least concentration that inhibited any observable growth of microorganisms (absence of turbidity) of the test organisms44,45.

Result and discussion

Phytochemical characterization of O. Lamiifolium (DM-AZ) and W. Somnifera (GZ-DK) aqueous leaf extract

An appropriate experimental procedure discussed in the previous section has been undergone to test the presence and absence of the phytochemicals in each of the crude leaf extracts in water solvent. The result (Table 1) shows that W. Somnifera (GZ-DK) leaf extract consists of tannins, alkaloids, saponins, flavonoids, cardiac glycosides, and phenolic compounds. On the other hand, O. Lamiifolium (DM-AZ) consists of all the above secondary metabolites except for saponins. The presence of a large number of phytochemicals suggests that the extracts have the potential to reduce and stabilize the nanoparticles46.

Table 1.

Phytochemical screening of aqueous crude extracts for GZ-DK and DM-AZ leaves.

| No | Phytochemical | Solvent | Types of leaf Extract | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GZ-DK | DM-AZ | |||

| 1 | Tannins | Water | + | + |

| 2 | Alkaloid | Water | + | + |

| 3 | Saponins | Water | + | - |

| 4 | Flavonoids | Water | + | + |

| 5 | cardiac glycosides | Water | + | + |

| 6 | Phenolic compounds | Water | + | + |

GZ-DK: W. somnifera collected from Dega Kedida area of Kambata Zone, Ethiopia. DM-AZ: O. Lamiifolium. collected from Azedbo area of Kambata Zone, Ethiopia. +: indicates presence of secondary metabolite. -: sign indicates absence of secondary metabolite.

Characterization of synthesized DMAZ-CuO and GZDK-CuO NPs

Powder XRD analysis

The powder x-ray diffraction (XRD) of biosynthesized DMAZ-CuO and GZDK-CuO nanoparticles (Fig. 2 (a) and (b) showed a series of diffraction peaks at 32.50, 35.56, 38.84, 48.98, 53.33, 58.15, 61.45, 66.27, 68.04, 72.61, and 75.14o, corresponding to the (110), (002), (111), ( ), (020), (202), (

), (020), (202), ( ), (

), ( ), (220), (311), and (

), (220), (311), and ( ) planes of reflections, respectively. Works of literature reveal that the two reflections at 2θ = 35.6 [002] and 2θ = 38.8 [111] are ascribed to the formation of CuO (space group C2/c) monoclinic crystal phase19,47 in the diffraction pattern of both biosynthesized nanoparticles. The current findings are similar to previous reports on CuO synthesis. The sharpness of the peaks in the XRD spectrum reveals their crystalline structure. The average size of DMAZ-CuO and GZDK–CuO NPs were calculated using Debye–Scherrer formulae (K = 0.94) from the full width at half maxima of the peaks (FWHM) in the XRD patterns17,48 and found to be 15 nm and 19 nm, respectively (Table 2). The four peaks in the range 2θ = 30 to 50 are used in the determination of the crystalite sizes. The peaks in the range 2θ = 30 to 50 are also compared to the calculated powder XRD patterns of CuO nanoparticles in the CCDC 1602101 reported so far (Fig. 2 (C)), and are seen at the same Bragg angles. This confirms that the leaf extracts can assist synthesis of smaller CuO nanoparticles.

) planes of reflections, respectively. Works of literature reveal that the two reflections at 2θ = 35.6 [002] and 2θ = 38.8 [111] are ascribed to the formation of CuO (space group C2/c) monoclinic crystal phase19,47 in the diffraction pattern of both biosynthesized nanoparticles. The current findings are similar to previous reports on CuO synthesis. The sharpness of the peaks in the XRD spectrum reveals their crystalline structure. The average size of DMAZ-CuO and GZDK–CuO NPs were calculated using Debye–Scherrer formulae (K = 0.94) from the full width at half maxima of the peaks (FWHM) in the XRD patterns17,48 and found to be 15 nm and 19 nm, respectively (Table 2). The four peaks in the range 2θ = 30 to 50 are used in the determination of the crystalite sizes. The peaks in the range 2θ = 30 to 50 are also compared to the calculated powder XRD patterns of CuO nanoparticles in the CCDC 1602101 reported so far (Fig. 2 (C)), and are seen at the same Bragg angles. This confirms that the leaf extracts can assist synthesis of smaller CuO nanoparticles.

Fig. 2.

X-ray diffraction patterns of GZDK-CuO NPs (a), DMAZ-CuO NPs (b) and CuO NPs calculated from CCDC 1,602,101.

Table 2.

Crystallite size estimation for DMAZ-CuO NPs and GZDK-CuO NPs.

| NPs | 2-Theta (degree) |

Wavelength of X-rays (λ) (Angstroms) |

FWHM (ß) (degrees) |

Miller Indices (hkl) |

Crystallite size (nm) |

Average Crystallite size (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMAZ-CuO | 32.50 | 1.54056 | 0.433680064 | (110) | 19.918716 | |

| 35.56 | 1.54056 | 0.557150006 | (002) | 15.629957 | ||

| 38.84 | 1.54056 | 0.761000801 | (111) | 11.550900 | 15.08883725 | |

| 48.98 | 1.54056 | 0.687420033 | ( ) ) |

13.255776 | ||

| GZDK-CuO | 32.50 | 1.54056 | 0.335080048 | (110) | 25.782584 | |

| 35.56 | 1.54056 | 0.441460005 | (002) | 19.729289 | ||

| 38.84 | 1.54056 | 0.596030006 | (111) | 14.755241 | 19.13609700 | |

| 48.98 | 1.54056 | 0.559950025 | ( ) ) |

16.277274 |

Both GZDK-CuO NPs and DMAZ-CuO NPs have similar peak at the same range except the existence of the two distinct and smaller intense peaks in the range 2θ = 65–70 in DMAZ-CuO NPs compared to GZDK-CuO NPs.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) analysis

The functional groups in GZDK-CuO and DMAZ-CuO nanoparticles, as well as in the leaf extracts (DMAZ and GZDK), were identified using FTIR spectrometry within the range of 4000 –400 cm⁻¹ (Fig. 3). As observed, a broadband peak around 3394 cm− 1 corresponds to the OH stretching of phenolic compounds stabilizing GZDK-CuO NPs18. The band at 1361 cm− 1 for GZDK-CuO NPs and 1362 cm− 1 for DMAZ-CuO NPs show the presence of C-N stretching vibrations of amines17. The peak at 1109 cm− 1 and 1108 cm− 1 shows C-O stretching present in the GZDK-CuO NPs and DMAZ-CuO NPs typical of flavonoids17,18. The intense bands down to 466 cm− 1 and 479 cm− 1 indicated the formation of pure Cu-O stretching vibrations, confirming the formation of CuO NPs in the GZDK-CuO NPs and DMAZ-CuO NPs respectively49. From the FTIR analysis, it can be concluded that phytochemicals such as phenols, flavonoids, alkaloids, and others in the plant extract are able to reduce and stabilize the metal ions to form CuO NPs. The FTIR spectra of the aqueous leaf extracts displayed a broad peak centered on 3312 and 3321 cm− 1, indicating the presence of water and hydrogen bonding. These peaks were diminished or eliminated after repeatedly exposing the nanoparticles to a vacuum oven. Additionally, other peaks were red-shifted, confirming the attachment of extract functionalities to the surface of the CuO nanoparticles, which served as capping and stabilizing agents. The decrease in the intensities of certain peaks in the FTIR spectra of the nanoparticles was attributed to the reduction in the amounts of secondary metabolites due to the heating process.

Fig. 3.

FT-IR spectra of GZDK -CuO NPs and DMAZ- CuO NPs.

UV-Vis-DRS analysis of biosynthesis CuO NPs

The optical properties of DMAZ-CuO and GZDK-CuO nanoparticles produced using a green synthesis method were determined through UV-visible diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (UV-Vis-DRS) in the 200–800 nm range (insets in Fig. 4 (a) and (b)). The band gap energy of the biosynthesized CuO nanomaterials was estimated using the Tauc plot method50. Figure 4 (a) and (b) illustrate the estimated band gap energies of 1.47 eV for DMAZ-CuO NPs and 1.6 eV for GZDK-CuO NPs, respectively. Furthermore, CuO NPs prepared using aqueous leaf extracts of O. lamiifolium and W. somnifera had smaller band gap energies compared to CuO NPs synthesized using other leaf extracts reported so far30,31, indicating the potential to produce CuO NPs active in the visible region of the electromagnetic spectrum.

Fig. 4.

Tauc plot of biosynthesized CuO NPs using (a) O. lamiifolium and (b) W. somnifera leaf extracts, respectively.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) analysis

The morphologies and surface structures of DMAZ-CuO NPs and GZDK-CuO NPs synthesized via the green method were analyzed using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). The resulting morphologies, depicted in Fig. 5 (A) and (B), reveal distinct structural characteristics for each type of nanoparticle. The SEM images in Fig. 5 (A) show that the DMAZ-CuO NPs have an irregular distribution of spherical particles. In contrast, the GZDK-CuO NPs, illustrated in Fig. 5 (B), exhibit a more varied morphology. This difference in shape can be attributed to the different precursor materials used in the green synthesis method. Additionally, the surface of the GZDK-CuO NPs appears rougher compared to that of the DMAZ-CuO NPs, which may enhance their reactivity and interaction with other substances in various applications.

Fig. 5.

SEM images of (A) DMAZ- CuO NPs and (B) GZDK- CuO NPs.

Antibacterial activity

GZDK-CuO NPs and DMAZ-CuO NPs were tested to have antibacterial activities towards S. aureus, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa. The effect of different concentrations of CuO NPs like 10 µg⁄mL, 20 µg ⁄mL, and 40 µg ⁄mL on bacteria was performed. As shown in Fig. 6, the increase in the concentration of CuO nanoparticles increases the antibacterial activity. Figure 6 shows a clear zone of growth inhibition (ZOI) when each of the bacteria was treated with either of the nanoparticles on the disc whereas the standard antibiotic (Amoxicillin = AMX) shows a higher zone of inhibition.

Fig. 6.

Disc diffusion observed when bacterial strains are treated with different concentration of GZDK- CuO NPs against (a) S. aureus, (b) P. aeruginosa and (c) E.coli; DMAZ-CuO NPs against (d) S. aureus, (e) P. aeruginosa and (f) E.coli.

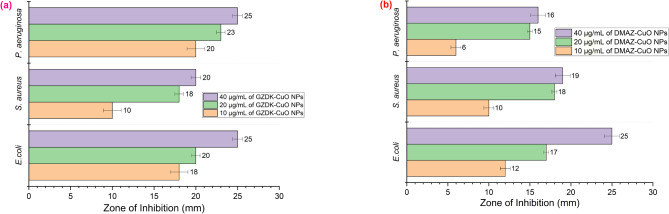

A one way ANOVA was utilized, and the mean ± standard deviation (SD) calculations were conducted in triplicate. The graph in Fig. 7(a) illustrates that 40 mg/mL of GZDK-CuO nanoparticles (NPs) inhibited E. coli and P. aeruginosa equally, with a zone of inhibition (ZOI) measuring 25 ± 0.58 mm. Conversely, a concentration of 10 mg/mL of GZDK NPs produced the smallest clear zone of inhibition against S. aureus, measuring 10 ± 1.06 mm. Similarly, a close look at graph Fig. 7(b), demonstrates that E. Coli is greatly inhibited (ZOI = 25 ± 0.92 mm) by 40 µg/mL DMAZ-CuO NPs whereas P. aeruginosa the least (ZOI = 6 ± 0.61 mm). Overall, both types of NPs are able to inhibit growth of Gram-negative (E. Coli and P. aeruginosa) and Gram-positive bacteria (S. aureus) with activity higher to Gram-negative bacteria as they have thinner cell wall. Analysis of Fig. 7(a) and (b) also indicated that an increase in the concentration of NPs increases clear zone of inhibition against bacteria. The corresponding bacteria treated with amoxicillin, which was taken as positive control showed a greater zone of inhibition (30 mm) compared to the action of GZDK- CuO NPs and DMAZ-CuO NPs. Similarly, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was taken as a negative control and it did not show any zone of inhibition against all three bacterial strains.

Fig. 7.

Zone of inhibition when different concentration of (a) GZDK-CuO NPs and (b) DMAZ- CuO NPs are treated with S. aureus, P. aeruginosa and E.coli. Error bars represent deviations from the mean, with significant differences at p < 0.05.

Determination of MIC value

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) value was determined by adding 3 to 4 bacterial colonies into 4 mL of broth solution and treating with various concentrations (10, 5, 2.5, 1.25, and 0.625 µg/mL) of GZDK-CuO NPs and DMAZ-CuO NPs. The mixtures were put under an incubator for about 24 h. As shown in Fig. 8, the least concentration of the NPs that inhibited any visible growth or less turbid bacterial culture in the test tube shows a higher MIC value.

Fig. 8.

MIC vale for GZDK-CuO NPs (a) and DMAZ-CuO NPs (b) against S. aureus, Ecoli and P. aeruginosa. Error bars represent deviations from the mean, with significant differences at p < 0.05.

A clear solution was obtained at 0.625 ± 0.236 µg/mL, 5 ± 0.236 µg/mL, and 1.25 ± 0.236 µg/mL concentration (MIC values) of GZDK-CuO NPs against S. aureus, E.coli, and P. aeruginosa, respectively (Fig. 8a). Similarly, clear solutions are observed at 2.5 ± 0.095 µg/mL, 1.25 ± 0.095 µg/mL and 0.625 ± 0.095 µg/mL concentration (MIC values) of DMAZ-CuO NPs against S. aureus, E.coli, and P. aeruginosa, respectively (Fig. 8b). The values presented are the mean ± SD, derived from triplicate calculations using a one-way ANOVA test.

Comparative analysis of the activity of CuO NPs over other green-synthesized NPs

The antibacterial activities of CuO nanoparticles (NPs) synthesized using the leaf extract of O. Lamiifolium (DMAZ-CuO) and W. Somnifera (GZDK-CuO) have been compared with previously published results. Table 3 indicates that the NPs being investigated currently exhibit comparable effectiveness to other similarly green-synthesized CuO NPs in combating both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.

Table 3.

Plants used in the synthesis of CuO nanoparticles, the methods for their characterization, and their antibacterial properties.

| No | Plant name | Parts of plants used |

size (nm) | Characterization techniques | Bacteria | The highest inhibition zone (mm) |

Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sesbania grandiflora | Leaves | 33 | UV–Vis DRS, FTIR, XRD, SEM | P. aeruginosa | 19 | 51 |

| S. aureus | 15 | ||||||

| 2 |

Ageratum houstonianum Mill |

Leaves | 80 | UV–Vis, FTIR, XRD, SEM | E. coli | 12.43 | 52 |

| 3 | Nilgirianthus ciliates | Leaves | 20 | UV–Vis, FTIR, XRD, SEM | P. aeruginosa | 17 | 53 |

| 4 | Rosmarinus officinalis | Leaves | - | UV–Vis, FTIR, XRD, FESEM, DLS | P. aeruginosa | 20 | 25 |

| 5 | Abutilon indicum leaves | Leaves | 28.10 | UV–Vis, FTIR XRD, SEM | S. aureus | 22 | 52 |

| E. coli | 32 | ||||||

| 6 | Ocimum Lamiifolium | Leaves | 15.09 | UV–Vis DRS, FTIR XRD, SEM | S. aureus | 19 | This work |

| E. coli | 25 | ||||||

| P. aeruginosa | 16 | ||||||

| 7 | Withana Somnifera | Leaves | 19.14 | UV–Vis DRS, FTIR XRD, SEM | S. aureus | 20 | This work |

| E. coli | 25 | ||||||

| P. aeruginosa | 25 |

Conclusion

CuO nanoparticles were successfully synthesized using green synthesis methods with aqueous extracts from O. Lamiifolium (DMAZ) and W. Somnifera (GZDK) plants. Detailed characterization of the nanoparticles was conducted using Scanning Electron Microscopy, X-Ray Diffraction analysis, and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. XRD analysis revealed average particle sizes of 15.09 nm for DMAZ CuO-NPs and 19.14 nm for GZDK-CuO NPs. Antibacterial activities of both DMAZ CuO-NPs and GZDK-CuO NPs were tested against E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus using the disc diffusion assay method. The results showed that the biosynthesized CuO nanoparticles have strong antimicrobial potential against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, with smaller particle sizes exhibiting higher antibacterial effects. The authors suggest that secondary metabolites play a vital role during the preparation of DMAZ-CuO and GZDK-CuO NPs, and plants with higher content of secondary metabolites are more likely to produce copper oxide nanoparticles. Future research is recommended to investigate the antibacterial properties of these nanoparticles against a broader range of bacterial strains, as well as other microorganisms like fungi and viruses. Additionally, exploring the synergistic effects of these nanoparticles when combined with other antimicrobial agents and studying their long-term stability and shelf-life are crucial considerations for ensuring their sustained efficacy.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Department of Chemistry and Biology, Wolaita Sodo University, Ethiopia for the keen support in allowing the laboratory facilities. The partial financial support of Wolaita Sodo University is also gratefully acknowledged.

Author contributions

S.M. conducted the experiments; T.H. and G.A. supervised S.M. and analyzed the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained errors. In the Materials and methods section, under the subheading ‘Characterization of synthesized copper oxide nanoparticle, CuO-NPs’, ‘ was omitted from the Debye–Scherrer formulae. Furthermore, Figure 6 contained errors, where the stated concentrations ‘10’, ‘20’, and ‘40 µg/ml’ were incorrectly given as ‘20’, ‘40’, and ‘60 µg/ml’. Lastly, Figures 1, 6 and 7 have been exchanged for higher resolution images. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

5/12/2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41598-025-98002-2

References

- 1.Selim, Y. A., Azb, M. A., Ragab, I. & Abd El-Azim, H. M. Green Synthesis of Zinc Oxide nanoparticles using Aqueous Extract of Deverra tortuosa and their cytotoxic activities. Sci. Rep.10, 3445 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barzinjy, A. A., Hamad, S. M., Aydın, S., Ahmed, M. H. & Hussain, F. H. S. Green and eco-friendly synthesis of nickel oxide nanoparticles and its photocatalytic activity for methyl orange degradation. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron.31, 11303–11316 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anjum, S. et al. Emerging applications of Nanotechnology in Healthcare Systems: Grand challenges and perspectives. Pharmaceuticals (Basel)14, 707 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Malik, S., Muhammad, K., Waheed, Y. & Nanotechnology A revolution in Modern Industry. Molecules28, 661 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Singh, K. R. B., Nayak, V., Singh, J., Singh, A. K. & Singh, R. P. Potentialities of bioinspired metal and metal oxide nanoparticles in biomedical sciences. RSC Adv.11, 24722–24746 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saqib, S. et al. Catalytic potential of endophytes facilitates synthesis of biometallic zinc oxide nanoparticles for agricultural application. BioMetals. 35, 967–985 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saqib, S. et al. Organometallic assembling of chitosan-Iron oxide nanoparticles with their antifungal evaluation against Rhizopus oryzae. Appl. Organomet. Chem.33, e5190 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baig, N., Kammakakam, I. & Falath, W. Nanomaterials: a review of synthesis methods, properties, recent progress, and challenges. Mater. Adv.2, 1821–1871 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gawande, M. B. et al. Cu and Cu-Based nanoparticles: synthesis and applications in Catalysis. Chem. Rev.116, 3722–3811 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joudeh, N. & Linke, D. Nanoparticle classification, physicochemical properties, characterization, and applications: a comprehensive review for biologists. J. Nanobiotechnol.20, 262 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boselli, L. et al. Classification and biological identity of complex nano shapes. Commun. Mater.1, 35 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saqib, S. et al. Bimetallic assembled silver nanoparticles impregnated in aspergillus fumigatus extract damage the bacterial membrane Surface and Release Cellular contents. Coatings. 12, 1505 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yetisgin, A. A., Cetinel, S., Zuvin, M., Kosar, A. & Kutlu, O. Therapeutic nanoparticles and their targeted delivery applications. Molecules25, 2193 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Stater, E. P., Sonay, A. Y., Hart, C. & Grimm, J. The ancillary effects of nanoparticles and their implications for nanomedicine. Nat. Nanotechnol.16, 1180–1194 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farhat, M. et al. Drug-resistant tuberculosis: a persistent global health concern. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.22, 617–635 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Mitcheltree, M. J. et al. A synthetic antibiotic class overcoming bacterial multidrug resistance. Nature. 599, 507–512 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nzilu, D. M. et al. Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles and its efficiency in degradation of rifampicin antibiotic. Sci. Rep.13, 14030 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atri, A. et al. Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using Ephedra Alata plant extract and a study of their antifungal, antibacterial activity and photocatalytic performance under sunlight. Heliyon. 9, e13484 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Veisi, H. et al. Biosynthesis of CuO nanoparticles using aqueous extract of herbal tea (Stachys Lavandulifolia) flowers and evaluation of its catalytic activity. Sci. Rep.11, 1983 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang, W., Fang, H., Zhang, S. & Yu, H. Optimised green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles and their antifungal activity. Micro Nano Lett.16, 374–380 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mendes, C. R. et al. Antibacterial action and target mechanisms of zinc oxide nanoparticles against bacterial pathogens. Sci. Rep.12, 2658 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Makabenta, J. M. V. et al. Nanomaterial-based therapeutics for antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.19, 23–36 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bai, B. et al. Biosynthesized copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO NPs) enhances the anti-biofilm efficacy against K. pneumoniae and S. Aureus. J. King Saud Univ. - Sci.34, 102120 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rabiee, N. et al. Biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles with potential Biomedical Applications. Int. J. Nanomed.15, 3983–3999 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bagherzadeh, M. et al. Bioengineering of CuO porous (nano)particles: role of surface amination in biological, antibacterial, and photocatalytic activity. Sci. Rep.12, 15351 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sahalie, N. A., Abrha, L. H. & Tolesa, L. D. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of leave extract of Ocimum lamiifolium (damakese) as a treatment for urinary tract infection. Cogent Chem.4, 1440894 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woldesellassie, M., Eyasu, M. & Kelbessa, U. In vivo anti-inflammatory activities of leaf extracts of Ocimum lamiifolium in mice model. J. Ethnopharmacol.134, 32–36 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paul, S. et al. Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal (Ashwagandha): a comprehensive review on ethnopharmacology, pharmacotherapeutics, biomedicinal and toxicological aspects. Biomed. Pharmacother.143, 112175 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Owais, M., Sharad, K. S., Shehbaz, A. & Saleemuddin, M. Antibacterial efficacy of Withania somnifera (ashwagandha) an indigenous medicinal plant against experimental murine salmonellosis. Phytomedicine. 12, 229–235 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Velsankar, K., Vinothini, V., Sudhahar, S., Kumar, M. K. & Mohandoss, S. Green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles via Plectranthus amboinicus leaves extract with its characterization on structural, morphological, and biological properties. Appl. Nanosci.10, 3953–3971 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Velsankar, K., R, R. M. A. K., Sudhahar, S. & P., V, M. & Green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles via Allium sativum extract and its characterizations on antimicrobial, antioxidant, antilarvicidal activities. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.8, 104123 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Velsankar, K., Parvathy, G., Mohandoss, S., Kumar, R. M. & Sudhahar, S. Green synthesis and characterization of CuO nanoparticles using Panicum sumatrense grains extract for biological applications. Appl. Nanosci.12, 1993–2021 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jain, S. & Mehata, M. S. Medicinal Plant Leaf Extract and pure flavonoid mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their enhanced Antibacterial Property. Sci. Rep.7, 15867 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shahrivari, S., Zeebaree, S. M. S., Alizadeh-Salteh, S., Feizy, H. S. & Morshedloo, M. R. Phytochemical variations antioxidant, and antibacterial activities among zebaria sumac (Rhus coriaria var. Zebaria) populations in Iraq. Sci. Rep.14, 4818 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu, M., Gouvinhas, I., Rocha, J. & Barros A.I.R.N.A. Phytochemical and antioxidant analysis of medicinal and food plants towards bioactive food and pharmaceutical resources. Sci. Rep.11, 10041 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ukwa, U. D., Saliu, J. K. & Akinsanya, B. Phytochemical profiling and anthelmintic potential of extracts of selected tropical plants on parasites of fishes in Epe Lagoon. Sci. Rep.13, 22727 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen, C. et al. Extraction and purification of saponins from Sapindus mukorossi. New J. Chem.45, 952–960 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rahman, M. M., Islam, M. B., Biswas, M., Khurshid & Alam A.H.M. In vitro antioxidant and free radical scavenging activity of different parts of Tabebuia pallida growing in Bangladesh. BMC Res. Notes. 8, 621 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salvamani, S., Gunasekaran, B., Shukor, M. Y., Abu Bakar, M. Z. & Ahmad, S. A. Phytochemical investigation, hypocholesterolemic and anti-atherosclerotic effects of Amaranthus viridis leaf extract in hypercholesterolemia-induced rabbits. RSC Adv.6, 32685–32696 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Senthilkumar, N. et al. Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using leaf extract of Tectona grandis (L.) and their anti-bacterial, anti-arthritic, anti-oxidant and in vitro cytotoxicity activities. New J. Chem.41, 10347–10356 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mahmood, R. I. et al. Biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles mediated Annona muricata as cytotoxic and apoptosis inducer factor in breast cancer cell lines. Sci. Rep.12, 16165 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rajamma, R., Nair, G., Abdul khadar, S., Baskaran, B. & F. & Antibacterial and anticancer activity of biosynthesised CuO nanoparticles. IET Nanobiotechnol.14, 833–838 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benkova, M., Soukup, O. & Marek, J. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing: currently used methods and devices and the near future in clinical practice. J. Appl. Microbiol.129, 806–822 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Belanger, C. R. & Hancock, R. E. W. Testing physiologically relevant conditions in minimal inhibitory concentration assays. Nat. Protoc.16, 3761–3774 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blondeau, D. et al. Antimicrobial activity and chemical composition of white birch (Betula papyrifera Marshall) bark extracts. MicrobiologyOpen. 9, e00944 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pradeep, M., Kruszka, D., Kachlicki, P., Mondal, D. & Franklin, G. Uncovering the phytochemical basis and the mechanism of plant extract-mediated eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ultra-performance Liquid Chromatography coupled with a photodiode array and high-resolution Mass Spectrometry. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng.10, 562–571 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shehab, W. S. et al. CuO nanoparticles for green synthesis of significant anti-helicobacter pylori compounds with in silico studies. Sci. Rep.14, 1608 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verma, R. et al. Microwave-assisted biosynthesis of CuO nanoparticles using Atalantia monophylla (L.) Leaf Extract and its Biomedical Applications. Chem. Eng. Technol.44, 1496–1503 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meena, J. et al. Copper oxide nanoparticles fabricated by green chemistry using Tribulus terrestris seed natural extract-photocatalyst and green electrodes for energy storage device. Sci. Rep.13, 22499 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Makuła, P., Pacia, M. & Macyk, W. How to correctly determine the Band Gap Energy of Modified Semiconductor Photocatalysts based on UV–Vis Spectra. J. Phys. Chem. Lett.9, 6814–6817 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patil, M. P. & Kim, G. D. Eco-friendly approach for nanoparticles synthesis and mechanism behind antibacterial activity of silver and anticancer activity of gold nanoparticles. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.101, 79–92 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sathiyavimal, S. et al. Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using Abutilon indicum leaves extract and their evaluation of antibacterial, anticancer in human A549 lung and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Food Chem. Toxicol.168, 113330 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vaidehi, D., Bhuvaneshwari, V., Bharathi, D. & Sheetal, B. P. Antibacterial and photocatalytic activity of copper oxide nanoparticles synthesized using Solanum lycopersicum leaf extract. Mater. Res. Express. 5, 085403 (2018). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.