Summary

In the Western Pacific Region, the prevalence of dementia is expected to increase, however, the diversity of the region is expected to present unique challenges. The region has varying levels of preparedness, with a limited number of countries having a specific national dementia plan and awareness campaigns. Diversity of risk and healthcare services within the region is exerting impact on diagnosis, treatment, care, and support, with most countries being under resourced. Similarly, the ability to monitor dementia-related indicators and progress research, particularly relating to treatment and clinical trial access needs to be addressed. Countries require comprehensive national plans that lay out how resources will be allocated to improve dementia literacy, train, and support carers, mobilise resources to reduce risk factors and improve research capabilities. These plans need to be informed by consumers and tailored to the region to develop an inclusive society for people living with dementia and their families.

Keywords: Dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, Western pacific region, Health policy

Introduction

Dementia has profound implications for individual citizens, families, and wider communities, leading to disability and impaired quality of life, as well as increased burden on health care systems. From a global perspective, 57·4 million people are currently living with dementia, with the majority residing in low-income and middle-income countries (LMIC). Recent forecasts predict that this number will increase to 152·8 million by 2050,1 presenting a significant health challenge. To address this urgent global health priority, the World Health Organization (WHO) released the ‘Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017–2025’ outlining targets to improve the lives of people with dementia, their carers and families, while also reducing the impact of dementia on a national and global level.2

In the Western Pacific Region, 20.1 million people are estimated to be living with dementia representing the third highest prevalence of dementia globally.3 The prevalence of dementia is expected to increase in many countries in the region due to ageing populations, with LMIC being disproportionately affected.1 The landscape for dementia management and treatment, particularly Alzheimer’s disease, is rapidly changing and the associated financial, medical, and social burden will likely lead to even further disparities across LMIC and high-income countries (HIC).

This viewpoint proposes a regional roadmap for dementia prevention, diagnosis and care based on the reviews of the ‘Dementia in the Western Pacific’ series. The current dementia landscape and policies of LMIC and HIC in the Western Pacific Region will be discussed based on the WHO’s ‘Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017–2025’2 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of WHO ‘Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017–2025’,2 action areas and global goals to be attained by 2025.

| Action area | WHO global goals attained by 2025 |

|---|---|

| Dementia as a public health priority | 75% of countries implement a national strategy |

| Dementia awareness and friendliness | 100% of countries to develop at least one functioning public awareness campaign. 50% of countries will have at least one dementia friendly initiative to foster a dementia-inclusive society. |

| Dementia risk reduction | Relevant risk factors reduction estimates, defined by the ‘Global action plan for prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013–2020’ |

| Dementia diagnosis, treatment, care, and support | At least 50% diagnostic rate for dementia cases for 50% of nations globally |

| Support for dementia carers | 75% of countries to provide support and training programs for carers and families of people with dementia |

| Information systems for dementia | 50% of countries routinely collecting a core set of dementia indicators biennially |

| Dementia research and innovation | The output of global research on dementia doubles between 2017 and 2025. |

Dementia as a public health priority-policies, strategies, and awareness

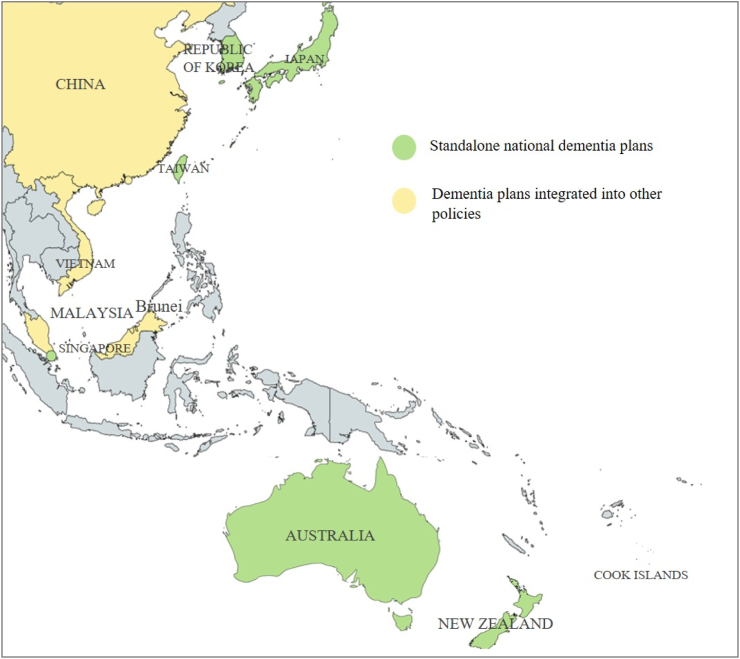

The WHO outlined the need for a multisectoral approach to address the complex needs associated with dementia, at a national level, by developing and coordinating policies and frameworks.2 Despite the global target set by WHO of 75% of countries implementing a national strategy (Table 1), and the significant health burden of dementia in the Western Pacific Region only six countries in the region (Fig. 1.) —Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Republic of Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore —have standalone national dementia plans, with a further five nations (Brunei Darussalam, China, Cook Islands, Vietnam and Malaysia) having a dementia plan integrated into a wider health care or ageing strategy.3 Though integrating many key priority areas, the national dementia plans in Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Republic of Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore vary in their approaches and priorities based on their specific healthcare, cultural and economic contexts. For instance, New Zealand and Australia emphasise culturally appropriate care, particularly for indigenous populations.4,5 Japan leads the region in incorporating risk reduction strategies and advanced technology into dementia care and the Republic of Korea has a particular emphasis around financial support6, 7, 8 The varying priorities within these standalone national dementia plans highlights the need for a tailored approach for the development and implementation of dementia policies throughout the Western Pacific Region.

Fig. 1.

National dementia plans in the Western Pacific Region. Map of Western Pacific Region indicating countries that have standalone national dementia plans (Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Republic of Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore) and countries that have a dementia plan integrated into a wider health care or ageing strategy (Brunei Darussalam, China, Cook Islands, Vietnam and Malaysia).

The Western Pacific Region comprises 37 countries, territories, and areas, nine of which are high-income (gross national income (GNI) per capita of >$14,005USD9,10), while the remaining 28 are classified as LMIC.9,10 Research has demonstrated that economic development and the presence of an ageing populations impacts the likelihood of a national dementia strategy.3,11 All of the countries with national dementia plans are classified as high-income.9 On the other hand, China and Malaysia are categorised as LMIC and are now developing national dementia plans, with the Philippines national dementia plan set to be included by the Philippine Council for Mental Health in its next Strategic Plan.12 Meanwhile, the Cook Islands and Brunei Darussalam, despite being HIC, are still in the process of developing their national dementia plans.

Overall, the region is underprepared from a national strategy perspective. Further contributing to the lack of public health response in the Western Pacific is the deficiency of dementia literacy across the region, particularly in LMIC.13 This lack of dementia literacy is exaggerated in the ageing population further compounding the issue.

Recent fieldwork has uncovered pervasive public misconceptions that dementia is not preventable and occurs as a normal part of the ageing process, a belief that is held even amongst healthcare professionals.14 These judgements may serve to promote diagnostic delay and impact the uptake of lifestyle factors that may modify risk, as well as disease-modifying treatments that are maximised earlier in the disease course.15,16 Of concern, Asian countries and LMIC are underrepresented in these surveys of public dementia literacy,14,15,17 where structural barriers to awareness and help-seeking are more common, and filial piety and elder care are often culturally embedded.18 Specifically, the expectation that children should care for their ageing parents might discourage external help seeking, especially in countries with laws mandating filial piety.19,20 However, reliance on family members to provide care may not meet the complex needs of people with dementia and is not sustainable, especially with ageing populations and demographic shifts in the Western Pacific Region.19

At a policy level, public misunderstanding about the futility of addressing dementia care reduces the drive for policy makers to devote resources to prevention and treatment services and may contribute to the low uptake of national frameworks across the region.14,19,21

Accordingly, the WHO has highlighted the importance of increasing dementia awareness and reducing stigma, setting a global target of 100% of countries to develop at least one functioning public awareness campaign by 2025 (Table 1).2 As of recent data, eight countries in the Western Pacific Region have initiatives and programs aimed at raising public awareness about dementia,3 while Australia, New Zealand, Republic of Korea, and Japan have established comprehensive public health campaigns, targeting dementia awareness, integrated into their national dementia frameworks.3 The aspirations of these frameworks include community support initiatives, public education programs, and collaboration with non-governmental organisations to provide resources and support for those impacted by dementia. Countries including China, Taiwan, Malaysia, Singapore, and the Philippines are actively working on improving public knowledge and understanding of dementia through various organisations as part of broader health initiatives.3 Some Western Pacific countries, such as the Cook Islands have no specific national campaign focused on dementia awareness, despite some engagement at the policy level,3 while the majority have no specific dementia awareness initiatives, aligning with the dearth of national policies.

Recommendations

Though assessing the impact of national awareness campaigns remains challenging,22 the uptake of dementia awareness programs helps to reduce stigma, facilitate early diagnosis and intervention, and improves quality of life by fostering a more inclusive environment.3,22 However, more research is required to better understand attitudes towards dementia and how this information can be applied to action change in LMIC and culturally diverse regions. Specifically, lower levels of dementia literacy disproportionally affect ethnic and racial minorities, including indigenous populations in the Western Pacific Region.17 In this context, informed, targeted and culturally appropriate approaches are needed to increase awareness to improve dementia literacy and solidify dementia as a public health priority via national frameworks. Specific approaches may include engaging with local communities and community leaders via tailored outreach programs to understand specific needs and preferences. Providing translational services and accessible education materials to foster culturally relevant communication and facilitating ongoing training for healthcare providers around cultural differences, and practices related to dementia diagnosis and care. Some of these strategies catering to multicultural and indigenous populations have been outlined in the national dementia plans of Australia and New Zealand and could help inform tailored national dementia plans across the Western Pacific region.4,5

Dementia risk reduction

Ageing is the primary risk factor associated with dementia with the risk of developing dementia, approximately doubling every five years over the age of 65.23 Within the Western Pacific Region, ageing populations have significantly contributed to the growing rates of dementia throughout the region. Specifically, LMIC have experienced an increase in ageing populations over recent decades, attributed to improvements in healthcare, increase in life expectancy and decreased fertility rates,24 potentially contributing to the increase in dementia rates in these nations which are probably already underestimated.

Though non-modifiable risk factors for dementia, including family history and genetic mutations such as the E4 form of the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene, can contribute to dementia risk,20 it is estimated globally that 40% of new cases of dementia could be avoided by ameliorating most modifiable risk factors.25 These factors include hearing impairment, head injury, low education, social isolation, depression, high blood pressure, midlife obesity, physical inactivity, diabetes, harmful use of alcohol, smoking, and air pollution.25 Notably, a 20% reduction in exposure to seven key risk factors (diabetes, hypertension in midlife, obesity in midlife, physical inactivity, depression, smoking, and low educational attainment) would result in a 15% reduction in the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease by 2050.26 The ‘WHO Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017–20252 (Table 1) has set targets aligning with these risk factors reduction estimates, defined by the ‘Global action plan for prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013–2020’.2,27 Correspondingly, high-income Western Pacific Region countries are projected to have the smallest increase in predicted dementia cases, contributed largely to an increase in educational attainment and a decline in cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors.1 However this remains uncertain due to the unknown effects of emerging risk factors. Notably, there are intranational differences in risk factors across different ethnic and cultural backgrounds, which may relate to socioeconomic disadvantage and an increased vulnerability to environmental influences rather than genetic disparities.28 As such, policies aimed at modifying risk factors need to have a nuanced approach which account for the diversity of the population within each nation.

Recommendations

In addition to ageing populations, low educational attainment, hearing loss, obesity, and low physical activity have been reported as major risk factors contributing to the proportion of dementia cases in LMIC and could be initially targeted by dementia prevention strategies.29 However, the majority of studies investigating dementia risk factors have been conducted in HIC, consequently there may be other risk factors in LMIC or other ethnic minority populations that are not being captured, requiring further investigation.30,31 Nevertheless, addressing known risk factors for dementia, through tailored strategies to improve education, nutrition, lifestyle, and health care within specific populations will positively impact the burden of dementia. Further, structured education promoting dementia risk reduction strategies at individual, community, and societal levels, addressing how risk factors can be modified, as well as understanding the contribution of non-modifiable risk factors is required. Policies also need to empower communities to take proactive steps and provide resources to tackle these risk factors. Based on reports to the WHO, seven countries in the Western Pacific Region have dementia risk reduction included in a health plan with only three countries (China, Japan, and Malaysia) having risk reduction outlined in specific dementia guidelines,3,32 emphasising the need for greater uptake of this dementia priority particularly in LMIC.

Dementia support, care, diagnosis, and treatment

People living with dementia have complex, multidisciplinary care needs and high levels of dependency and morbidity especially in the moderate to severe stages of the disease course.33 As a consequence of the wide economic and cultural variation across the Western Pacific Region, preparedness in integrated dementia care, diagnosis and support differs vastly and presents specific challenges from both human resource and economical perspectives.21

Diagnosis represents the critical first step for accessing formal dementia care, treatment, and support. The importance of early diagnosis was emphasised in the global dementia action plan, with the target of at least 50% diagnostic rate for dementia cases for 50% of nations globally (Table 1). On average, LMIC have around half the reported diagnostic rates of HICs, with a median reporting rate of only 27% for the whole Western Pacific Region.3 This disparity in diagnostics reflects the discrepancy in the availability of increasingly specialist diagnostic and care services for dementia, as well as issues with screening tools which may lack generalisability to populations with different social-economic and cultural backgrounds.34 Similarly, there are discrepancies in the readiness for emerging therapies such as recently approved amyloid-targeting monoclonal antibody therapies for Alzheimer’s disease.35 While some high to middle-income countries in the Western Pacific Region have taken initial steps towards the clinical approval and implementation of amyloid-targeting monoclonal antibody therapies, most LMIC are hindered by substantial barriers that also impact dementia care and treatment more broadly, including prohibitive treatment costs, limited healthcare infrastructure, inadequate access to advanced diagnostic and monitoring tools, and a shortage of specialised medical professionals.36

The considerable cultural diversity across the Western Pacific also has implications for dementia care services. A main provision for people with dementia is institutional care.3 Though all reporting WHO member states in the Western Pacific Region report tertiary facilities such as hospitals, other facilities such as respite care are considerably less available, particularly for LMIC.37 Additionally, equitable access to institutional care services can be challenging due to prohibitive costs, with vast variations in funding availability and access.38 Ensuring consistent quality of care and the availability of such services in remote or rural areas remain a challenge even in HIC.39 Additionally, some nations place more emphasis on intergenerational living and caregiving, particularly in LMIC where most people with dementia reside.19 Consequently, most people living with dementia are cared for by family members. This informal care is disproportionally provided by females, with the Western Pacific Region reporting the highest number of female informal care hours globally.3 The extent of informal dementia care costs are estimated to be twice that provided through formal health care avenues, with projections in the Asia–Pacific region estimated to be USD$109·9 billion annually.40,41 However, appropriate training or governmental support for these carers is limited, particularly outside of metropolitan areas.2,23 In recognition, the WHO has set a target of 75% of countries to provide support and training programs for carers and families of people with dementia by 2025. Though reporting from member states projects favourably with this target, a disproportionate number of LMIC, including those in the Western Pacific Region, are not represented or have a lower proportion of carer support services.3 Despite the target, over reliance on informal care is not sustainable and is inadequate in meeting the complex needs of people living with dementia, with evidence suggesting that the most effective model of care takes a multidisciplinary approach integrated with primary care.42 Ideally, these models of care should be developed to incorporate cultural and religious considerations for determining context specific risks. Additionally, the WHO recommends that people with dementia have access to rehabilitation services focusing on increasing self-care ability, independence, quality of life and mitigating carer burden.2 Despite this recommendation, rehabilitation is often under prioritised and resourced particularly in LMIC, with some estimates suggesting that less than 50% of people living with dementia receive the rehabilitation services required.43

Intra-national disparities are also evident for dementia services when comparing urban and rural locations, with most diagnostic, rehabilitation and support services being concentrated in urban centres. Consequently, direct access to relevant diagnostic and support services is acutely limited for people living in rural and remote areas which, in some countries of the Western Pacific Region, account for the majority of the population.44,45 This raises further issues regarding equity of access to services, treatments, and participation in clinical trials even for HICs. In addition to the geographic disadvantage of limited services in these remote locations, challenges are often associated with the unique needs and risk factors for different ethnic groups or indigenous populations often represented in rural and regional areas.2,46, 47, 48

Recommendations

Countries across the Western Pacific must develop and implement integrated care models applicable to different cultural settings and ethnic/racial groups. Though formal national dementia plans in the Western Pacific have addressed goals regarding supportive services for family caregivers, these efforts need to be expanded to cover more of the region. Including input from patient advocacy groups, such as Alzheimer’s Disease International may facilitate intergovernmental collaboration and investment. Specifically, infrastructure and workforce capacity need to be expanded, particularly for LMIC, around specialist assessment, care, and rehabilitation services for dementia. Building specialised facilities, such as memory clinics and dementia care centres would help to provide focused diagnosis, treatment, and expand support services. However, retrofitting existing healthcare facilities to integrate dementia care services maybe a more feasible solution in under-resourced countries. Developing community hubs that offer a range of services, including social activities, respite care, rehabilitation and support groups would expand capacity further, particularly in nations with a strong emphasis on community and remote regions with limited access to metropolitan hubs.

Investment in primary care, including staff training in dementia care practices to mitigate discrimination of people with dementia, and the interlinking with specialist assessment services will enable effective inter-sector health pathways mitigating diagnostic delays. Additionally, the use of new plasma biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease will assist in screening, triage, and diagnostic accuracy when available. Strategies must also be implemented to ensure equal access to diagnosis and subsequent rehabilitation and treatment options. The preparedness of the Western Pacific Region for novel treatments such as amyloid-targeting monoclonal antibody therapies for Alzheimer’s disease will require further investment into health system infrastructure, workforce growth, clinician training and support. As well as the provision of alternative therapies for those who are not eligible. Simultaneously, governments need to address fair and equitable access to these latest treatments and ensure infrastructure for their implementation. Complimentary to emerging therapies, non-pharmacological rehabilitation interventions could make a significant difference to the health and wellbeing of people with dementia and their carers.49 This may be especially impactful for LMICs, where rehabilitation programs could be incorporated into existing care models more seamlessly than emerging amyloid-targeting monoclonal antibody therapies.

Dementia research, innovation, and information systems

Systematic monitoring of dementia-related indicators is essential to support evidence-based policy, service planning and delivery, and to track progress of support programs and treatment strategies. The WHO ‘Global Dementia Action Plan’ outlines a global target of 50% of countries to routinely collect a core set of dementia indicators biennially by 20252 (Table 1), including anti-dementia medication availability, health and social workforce, community-based services, dementia care coordination, diagnostic rate, dementia-specific nongovernmental organisation, health and social care facilities, and standards/guidelines/protocols.

At the last report, only 37% of member states from the Western Pacific Region provided dementia indicators to the WHO’s global observatory of data, reflecting the dearth of appropriate monitoring systems, particularly in LMIC.3 The scarcity of dementia indicator reporting from LMIC demonstrates the need to support health infrastructure and build capacity to enable effective health information systems in these nations. However, the need to increase capacity is not limited to LMIC in the Western Pacific Region, with information systems for dementia being an underrepresented priority in existing national dementia plans of HIC, including Australia, Japan, and New Zealand.11

In addition to improving capacities to address gaps in care provision, building a comprehensive national surveillance system will facilitate research programs and the evaluation of novel treatment strategies and risk reduction programs using real-world data. Currently, dementia research accounts for less than 3% of the total health research output across all WHO regions, with the Western Pacific Region contributing 0·7%.3 The WHO’s ‘Blueprint for Dementia Research’ acknowledges research gaps and outlines 15 strategic goals to address deficits relating to research in dementia epidemiology and economics, disease mechanisms and models, drug development and clinical trials, and diagnosis and risk reduction.50 Additionally, there remain significant gaps in the dementia literature addressing the ethnic, racial, cultural and economic diversity of the Western Pacific Region. Specifically, the majority of research in dementia focuses on populations of European descent, including studies investigating genetic risk factors which can be greatly influenced by ethnic background.31,51 Engaging people with lived experience can inform all stages of research, from setting research priorities to translating research recommendations into practice and policy.50 Some countries in the region have incorporated consumer involvement at the policy level such as Australia’s ‘Statement on consumer and community involvement in health and medical research’ which recognises the benefit of including consumers to help deliver relevant research outcomes, however this is not common practise in many countries.50,52

Recommendations

The WHO’s ‘Blueprint for Dementia Research’ can provide a starting point for addressing gaps in dementia research by engaging research and funding focus in priority areas informed by people with lived experience, especially for LMIC.50 Currently, less than 10% of dementia research focuses on people living with dementia in LMIC.18 Correspondingly, no LMIC, including those in Western Pacific Region reported having a dementia research plan to the WHO.3 The predominance of published research from HIC is reflected in the allocation of resources to understanding disease pathogenesis via the establishment of patient registries and biobanks.53,54 Given the high cost in establishing and maintaining these resources, international links may be needed representing a potential area of capacity building particularly for LMIC. Such intergovernmental policies and bolstering of infrastructure across the region, especially for LMIC, will facilitate research output including investigation of novel treatment strategies. By supporting pharmaceutical companies to consider the Western Pacific Region for clinical trial involvement, more people living with dementia will gain access to potentially disease modifying novel treatments. This will also improve the generalisability of the results by recognising ethnic and racial differences in pathobiology and drug responses.55

Conclusion

Across the Western Pacific, countries need individualised and comprehensive national plans that lay out how resources will be allocated to improve dementia literacy, train, and support carers, mobilise resources to reduce risk factors and improve research capabilities. These plans need to be informed by consumers and tailored to the diversity of the region and address the unique inter- and intranational challenges with the goal of mitigating the growing social and economic impact to develop an inclusive society for people living with dementia and their families. The unique cultural diversity of this region presents specific issues for the development and implementation of policies. However, there are some protective factors unique to Western Pacific dwellers such as a strong emphasis on community, social connections, and participation, that should be harnessed to improve dementia awareness and prevention strategies in these communities. A broader international strategy across the region, focusing on collaboration, will help leverage the resources and knowledge in countries with greater preparedness and mitigate some of the challenges faced by under-resourced nations ensuring equitable access to care and treatment. The disparity in policies, clinical care, and research for dementia in the Western Pacific Region are representative of the issues faced by the wider global community. A collective engagement and taskforce for this region may serve as a blueprint for a worldwide effort to improve dementia care.

Contributors

HT: Concept, synthesis, writing original draft, writing, reviewing and editing; MCK: concept, writing, reviewing and editing; VCTM, SHK, NS, JYS, GS, SA, SW, KJA, DLT, SM, ST, RT, CSYL, CO, JCM, YHJ. DF. SLN, OP, RA, ED, SBP: writing, reviewing and editing.

Editor note

The Lancet Group takes a neutral position with respect to territorial claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Declaration of interests

ST's research is supported by an NHMRC Ideas Grant (APP2029871), FightMND, and Lenity Australia. SHK was supported by a grant of the Korea Dementia Research Project through the Korea Dementia Research Center (KDRC), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare and Ministry of Science and ICT, Republic of Korea (RS-2024-00348451)”. SW is the Clinical Lead/steering committee co-chair of the ADNeT Registry and received an honorium from ROCHE and Eisai for attendance at an advisory meeting. KJA received a speaker honorarium from Roche in 2023 and is supported by ARC FL19010001. CO is supported by a University of Sydney Robinson Fellowship and an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council EL2 Fellowship (2016866). CSYL is supported by the Sydney Medical School Foundation, University of Sydney. DF is supported by the Edwards Fund for Dementia Research and has received research grants from the Dementia Australia Research Foundation, outside the work submitted. OP is supported in part by an NHMRC Leadership Fellowship and has received research grants from the NHMRC and the Australian Research Council, outside the submitted work. JCM received a speaker honorarium; investigator-initiated research grant to institution from Eisai Australia. Y-HJ has received research grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and Arcare in Australia and travel support for invited talks from Singapore Sing Health, Northern Ireland Queen’s University Belfast, Hong Kong Jockey Club, and Korea National Health Insurance Service: Long-term Care, all outside the submitted work. MCK was supported by a NHMRC Practitioner Fellowship (1156093) and National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Partnership Project (1153439). RHT is supported by a FightMND Mid-Career Fellowship and her research is supported by NSW Health and MNDRA. GS is supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development. SN received a speaker honorarium HT, SP, DT, SM, SA, VCTM, NS, JYS, have no conflict of interests to declare.

References

- 1.GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7:e105–e125. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00249-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The World Health Organization . 2017. Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017–2025. Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 3.The World Health Organization . 2021. Global status report on the public health response to dementia. Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Australian Department of Health . Department of Health, Australian Government; 2015. National framework for action on dementia 2015–2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5.The New Zealand Ministry of Health . Ministry of Health; New Zealand: 2013. New Zealand framework for dementia care. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakanishi M., Nakashima T. Features of the Japanese national dementia strategy in comparison with international dementia policies: how should a national dementia policy interact with the public health- and social-care systems? Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(4):468–476.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seong S.J., Kim B.N., Kim K.W. National dementia plans of group of seven countries and South Korea based on international recommendations. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.40027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ministry of Health and Welfare Republic of Korea The 3rd national dementia plan. Ministry of Health and Welfare; Rupublic of Korea: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.The World Bank . 2024. Income classifications.https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 10.United Nations Statistics Division Per capita GNI at current prices - US dollars. UNData. https://data.un.org/Data.aspx?d=SNAAMA&f=grID%3a103%3bcurrID%3aUSD%3bpcFlag%3a1 Available from:

- 11.Sun F., Chima E., Wharton T., Iyengar V. National policy actions on dementia in the americas and asia-pacific: consensus and challenges. Pan Am J Public Health. 2020;44 doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2020.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anlacan V.M.M., Lanuza P.D.T., Sanchez A.A.R., Jamora R.D.G. Current status and challenges in dementia care in the Philippines: a scoping review. J Alzheim Dis. 2024;97(4):1533–1543. doi: 10.3233/JAD-230845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leung A.Y.M., Leung S.F., Ho G.W.K., et al. Dementia literacy in western pacific countries: a mixed methods study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2019;34:1815–1825. doi: 10.1002/gps.5197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cations M., Radisic G., Crotty M., Laver K.E. What does the general public understand about prevention and treatment of dementia? A systematic review of population-based surveys. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradford A., Kunik M.E., Schulz P., Williams S.P., Singh H. Missed and delayed diagnosis of dementia in primary care: prevalence and contributing factors. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23 doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181a6bebc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Power M.C., Willens V., Prather C., et al. Risks and benefits of clinical diagnosis around the time of dementia onset. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine. 2023;9 doi: 10.1177/23337214231213185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cahill S., Pierce M., Werner P., Darley A., Bobersky A. A systematic review of the public’s knowledge and understanding of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2015;29 doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prince M., Acosta D., Albanese E., et al. Ageing and dementia in low and middle income countries–using research to engage with public and policy makers. Int Rev Psychiatr. 2008;20:332–343. doi: 10.1080/09540260802094712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ayalon L., Roy S. Combatting ageism in the western pacific region. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2023;35 doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bu Q. To legislate filial piety: is the elderly rights law a panacea? Statute Law Rev. 2021;42(2):219–240. [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Lancet Regional Health-Western Pacific Dementia in the western pacific region: from prevention to care. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2022;26 doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diaz L.G., Durocher E., Gardner P., McAiney C., Mokashi V., Letts L. Assessment tools for measurement of dementia-friendliness of a community: a scoping review. Dementia. 2022;21:1825–1855. doi: 10.1177/14713012221090032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.2023 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19:1598–1695. doi: 10.1002/alz.13016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.United Nations . Department of Economic and Social Affairs; 2019. World population ageing 2019: highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/430) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Livingston G., Huntley J., Sommerlad A., et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the lancet commission. Lancet. 2020;396:413–446. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norton S., Matthews F.E., Barnes D.E., Yaffe K., Brayne C. Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: an analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:788–794. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70136-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The World Health Organization . 2013. Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alonso A., Mosley T.H., Jr., Gottesman R.F., Catellier D., Sharrett A.R., Coresh J. Risk of dementia hospitalisation associated with cardiovascular risk factors in midlife and older age: the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:1194–1201. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.176818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker R., Paddick S.M. Dementia prevention in low-income and middle-income countries: a cautious step forward. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7:e538–e539. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30169-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peters R., Booth A., Rockwood K., Peters J., D’Este C., Anstey K.J. Combining modifiable risk factors and risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anstey K.J., Ee N., Eramudugolla R., Jagger C., Peters R. A systematic review of meta-analyses that evaluate risk factors for dementia to evaluate the quantity, quality, and global representativeness of evidence. J Alzheim Dis. 2019;70:S165–S186. doi: 10.3233/JAD-190181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The World Health Organization Existence of standards/guidelines/protocols for prevention and risk reduction of dementia 2021. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/existence-of-standards-guidelines-protocols-for-prevention-and-risk-reduction-of-dementia Available from:

- 33.The World Health Organization . World Health Organization and Alzheimer’s Disease International; The United Kingdom: 2012. Dementia: a public health priority; p. 102. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chithiramohan T., Santhosh S., Threlfall G., et al. Culture-fair cognitive screening tools for assessment of cognitive impairment: a systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis Rep. 2024;8:289–306. doi: 10.3233/ADR-230194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferri C.P., Jacob K.S. Dementia in low-income and middle-income countries: different realities mandate tailored solutions. PLoS Med. 2017;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perneczky R., Jessen F., Grimmer T., et al. Anti-amyloid antibody therapies in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2023;146:842–849. doi: 10.1093/brain/awad005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.The World Health Organization Dementia health and social care facilities. Glob Health Observ Data. 2021 https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/dementia-care-facilities Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pedroza P., Miller-Petrie M.K., Chen C., et al. Global and regional spending on dementia care from 2000- 2019 and expected future health spending scenarios from 2020-2050: an economic modelling exercise. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;45 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giebel C. Current dementia care: what are the difficulties and how can we advance care globally? BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:414. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05307-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alzheimer Disease International . 2015. World alzheimer report 2015: the global impact of dementia: an analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. London. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oliva-Moreno J., Trapero-Bertran M., Peña-Longobardo L.M., Del Pozo-Rubio R. The valuation of informal care in cost-of-illness studies: a systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35:331–345. doi: 10.1007/s40273-016-0468-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frost R., Walters K., Aw S., et al. Effectiveness of different post-diagnostic dementia care models delivered by primary care: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70:e434–e441. doi: 10.3399/bjgp20X710165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.The World Health Organization . 2024. Rehabilitation.https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rehabilitation Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ritchie H. 2024. Urbanization: OurWorldInData.org.https://ourworldindata.org/urbanization Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 45.United Nations DoEaSA, Population Division . 2018. UN world urbanization prospect.https://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/Download/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arsenault-Lapierre G., Bui T.X., Le Berre M., Bergman H., Vedel I. Rural and urban differences in quality of dementia care of persons with dementia and caregivers across all domains: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23:102. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-09100-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnston K., Preston R., Strivens E., Qaloewai S., Larkins S. Understandings of dementia in low and middle income countries and amongst indigenous peoples: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Aging Ment Health. 2020;24:1183–1195. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2019.1606891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ma’u E., Cullum S., Cheung G., Livingston G., Mukadam N. Differences in the potential for dementia prevention between major ethnic groups WIthin one country: a cross sectional analysis of population attributable fraction of potentially modifiable risk factors in New Zealand. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2021;13 doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jeon Y.H., Krein L., O’Connor C.M.C., et al. A systematic review of quality dementia clinical guidelines for the development of WHO’s package of interventions for rehabilitation. Gerontol. 2023;63(9):1536–1555. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnac105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.The World Health Organization . 2022. A blueprint for dementia research. Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fitipaldi H., Franks P.W. Ethnic, gender and other sociodemographic biases in genome-wide association studies for the most burdensome non-communicable diseases: 2005-2022. Hum Mol Genet. 2023;32:520–532. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddac245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.National Health and Medical Research Council & Consumers Health Forum of Australia . 2016. Statement on consumer and community involvement in health and medical research. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mazumder S., Kiernan M.C., Halliday G.M., Timmins H.C., Mahoney C.J. The contribution of brain banks to knowledge discovery in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a systematic review. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2022;48 doi: 10.1111/nan.12845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boise L., Hinton L., Rosen H.J., et al. Willingness to Be a brain donor: a survey of research volunteers from 4 racial/ethnic groups. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2017;31:135–140. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ramamoorthy A., Pacanowski M.A., Bull J., Zhang L. Racial/ethnic differences in drug disposition and response: a review of recently approved drugs. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015;97:263–273. doi: 10.1002/cpt.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]