Abstract

Background

Food allergy (FA) is a common disorder in children and affects the health of children worldwide. The gut microbiota is closely related to the occurrence and development of FA. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is a way to treat diseases by reconstituting the microbiota; however, the role and mechanisms of FA have not been validated.

Methods

In this study, we established an ovalbumin (OVA)-induced juvenile mouse model and used 16S RNA sequencing, pathological histological staining, molecular biology, and flow-through techniques to evaluate the protective effects of FMT treatment on FA and to explore the mechanisms.

Results

OVA-induced dysregulation of the gut microbiota led to impaired intestinal function and immune dysregulation in FA mice. FMT treatment improved the structure, diversity, and composition of the gut microbiota and restored it to a near-donor state. FMT treatment reduced levels of Th2-associated inflammatory factors, decreased intestinal tissue inflammation, and reduced IgE production. In addition, FMT reduced the number of mast cells and eosinophils and suppressed OVA-specific antibodies. Further mechanistic studies revealed that FMT treatment induced immune tolerance by inducing the expression of CD103+DCs and programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) in mesenteric lymph nodes and promoting the production of Treg through the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/PD-L1 pathway. Meanwhile, Th2 cytokines, OVA-specific antibodies, and PD-1/PD-L1 showed a significant correlation with the gut microbiota.

Conclusions

FMT could regulate the gut microbiota and Th1/Th2 immune balance and might inhibit FA through the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, which would provide a new idea for the treatment of FA.

Keywords: Food allergy, Pathology, Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) treatment, Mechanism pathway

Introduction

Food allergy (FA) is a serious health problem, and food-induced anaphylaxis can often be life-threatening. Food allergies are more common in children compared with adults; they usually develop early in life and affect up to 10% of children.1 The estimated prevalence of FA among children in Europe and the West is around 6–8%.2,3 A recent meta-analysis of the Chinese population has also concluded that FA prevalence from 2009 to 2018 was 8% (95% CI: 6%–11%), higher than that from 1999 to 2008 (5%; 95% CI: 3%–7%).4 Therefore, it is important to address FA in children FA is an immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated hypersensitive reaction to food that results in the appearance of allergic symptoms.5 The incidence of FA has continued to rise over the last several decades, posing significant burdens on health and quality of life. Although elimination diets are a mainstay of management for children with FA, inappropriate dietary restrictions can occur.6 Oral immunotherapy (OIT) has been the best-researched therapeutic approach for treating FA. However, OIT-related adverse events are common during treatment,7 highlighting the need for better strategies for prevention, diagnosis, and therapy.

The gut microbiota plays an important role in maintaining intestinal homeostasis and affects the development of disease by affecting intestinal immunity. The gut microbiota alters the structure and function of the immune system, reshaping the immune microenvironment and affecting the immunity of the intestinal region. The use of probiotics or microbiota transplantation functions to recalibrate immune homeostasis while also contributing to the treatment or amelioration of diseases.8

FA is an adverse health effect arising from a specific immune response that occurs reproducibly on exposure to a given food.9 Intestinal microbial diversity during early-life colonization is critical to establishing an immunoregulatory network that protects against the induction of mucosal IgE, which is linked to allergy susceptibility.10 Growing evidence points out that dysbiosis of the gut microbiota can affect the progression of FA. Epidemiologic studies demonstrate associations between exposures known to modify the microbiome and the risk of food allergies. Human cohort studies have demonstrated gut microbiota dysbiosis in FA compared to healthy control subjects.11 Goldberg et al reported that, compared with infants without FA, those with FA had a lower abundance of Prevotella and short-chain fatty acids, which may disrupt gut homeostasis and gut barrier function.12 The gut microbiota may affect food allergy susceptibility by modulating type 2 immunity, influencing immune development and tolerance, regulating basophil populations, and promoting intestinal barrier function.13 Further studies on correcting dysbiosis for the prevention and treatment of FA are warranted.

The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is essential to regulating the inflammatory responses to autoimmunity and allergies. The main role of PD-1 and its ligands is to balance the immune response.14 Recent studies have shown that PD-L1 acts to regulate T-cell activation and function.15 In FA, overactive immune responses involve IgE-dependent activation and increased CD4+T helper type 2 (Th2) lymphocytes.16 PD-1 and its ligands have an essential role in maintaining T cell homeostasis via regulatory T-and B-cells (Tregs and Bregs)17 Th2 cells can be inactivated via PD-1 or with its ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2 18. PD-1/PD-L1 can function as a brake or a kick-start to regulate the adaptive immune response. These findings suggest that PD-1/PD-L1may be a key factor in FA. The study discovered that gut microbiota can influence immune function in vivo by regulating PD-1 levels. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) from cancer patients who responded to immune checkpoint inhibitors (targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis) into germ-free or antibiotic-treated mice ameliorated the antitumor effects of PD-1 blockade, whereas FMT from nonresponding patients failed to do so.18 It has been shown that PD-1 can influence the function of immune cells such as DCs and T cells and interfere with the Th1/Th2 immune balance after interacting with PD-L1 20-21.

Recently, FMT has attracted a lot of attention because of its modulation of the host microbiota. FMT is a treatment that involves transplanting gut microbiota from healthy donors into recipients.19 Therefore, FMT may be a promising alternative option for the treatment of allergic diseases. Currently, the clinical treatment of FMT improves a variety of systemic diseases, such as Clostridium difficile infection, ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, hepatic encephalopathy, and autism spectrum disorder.19 However, the effect of FMT on FA has not been reported. This study will be the first to investigate the therapeutic effect of FMT on FA in juvenile mice and its potential mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Animals and experimental design

Pregnant BALB/c mice were purchased from the Fourth Military Medical University. During the experiment, mice were housed at 21–25 °C with a humidity of approximately 50%–65% under a 12-h light/dark cycle, respectively. Mice were given free access to food and water. This study was approved by the Animal Research Ethics Committee of the Fourth Military Medical University (20170403).

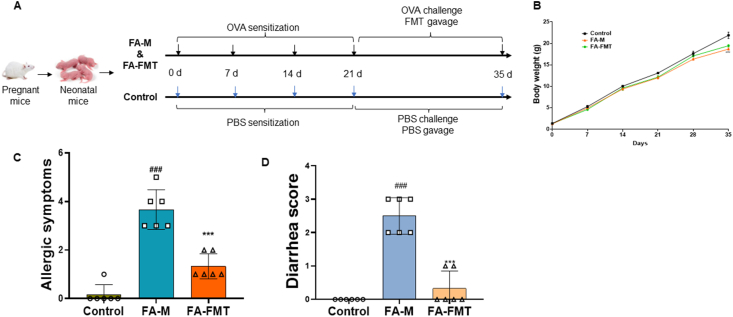

After the pregnant mice gave birth naturally, neonatal mice were divided into 3 groups randomly: the control group, the model group (FA-M group), and the FMT treatment group (FA-FMT group). FA-M and FA-FMT mice were sensitized intraperitoneally with 10 μg of OVA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.) and 800 μg of AL(OH)3 (Tianjin Tianshili Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China) in a final volume of 20 μL per mouse on days 0, 7, and 14. One week later, mice received OVA gavage (50 mg/200 μL/mouse) every other day from day 21 to day 35. At the same time, the control group received the same concentration of physiological saline. Moreover, on days 21–35, the FA-FMT group was gavaged with 150 μL of fresh fecal solution daily (when administering OVA and FMT on the same day, allow a 2-h interval between administrations), while the FA-M and control groups were gavaged the same concentration of physiological saline every day. The experimental protocol is shown in Fig. 1A.

Fig. 1.

FMT improved body weight, diarrhea score and allergic symptoms in food allergy mice. Animal experiment protocol (A). Body weight (B, n = 5). Allergic symptoms (C, n = 6). Diarrhea score (D, n = 6). ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 FA-M group vs Control group, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001 FA-FMT group vs FA-M group. FA, food allergy. FA-M, food allergy model mice. FA-FMT, food allergy mice gavage with fecal microbiota transplantation

Preparation for fecal microbiota transplantation

FMT was prepared as previously described.20 Briefly, fresh stools were collected from the control group mice and resuspended in sterile saline (500 mg of feces were immediately placed into 5 mL of sterile saline) for 1 min. Then, the dissolved feces were centrifuged at 1000 g (4 °C) for 3 min. The collected fecal suspension was administered within 10 min.

Body weight, diarrhea, and allergic symptoms score

Body weight was determined each week throughout the experiment. Referring to the description of Yamaki K et al, after the OVA challenge, mice were observed for diarrhea within 1 h and scored. The score of Diarrhea and allergic symptoms were showed in Table 1, Table 2.21

Table 1.

Diarrhea score of mice

| score | stool condition of mice |

|---|---|

| 0 | normal stools |

| 1 | a few wet and unformed stools |

| 2 | a number of wet and unformed stools with moderate perianal staining of the coat |

| 3 | severe, watery stool with severe perianal staining of the coat |

Table 2.

Allergic symptoms score of mice

| score | symptoms |

|---|---|

| 0 | no symptoms |

| 1 | reduced activity and trembling of limbs |

| 2 | loss of consciousness and no activity upon prodding |

| 3 | convulsions and death |

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Serum samples were collected to analyze the levels of inflammatory cytokines and OVA-specific immunoglobulins (Igs). Serum interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-13, OVA-specific IgE, IgG1, and circulating mast cell protease 1 (MCPT-1) were measured using ELISA kits (RD System, Boston, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Small intestinal tissues were collected to evaluate local allergic inflammation. After weighing 25 mg of small intestine tissue and adding 250 μL of PBS, the specimen was well homogenized using a tissuelyser (Shanghai Jingxin Industrial Development Co., Ltd., China) at 65 Hz for 500s. Afterwards, it was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected. The concentrations of IL-5, IL-13, IL-17, and IgA in the supernatant were measured using an ELISA kit.22

Inflammatory cells

Take 5 μL of fresh blood to make a blood smear of appropriate thickness and count the eosinophils under an oil microscope using Wright-Giehl's stain.

Histopathology

The intestinal tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. After that, paraffin embedding and sectioning were performed to make 5-μm paraffin sections, paraffin deparaffinized in xylene, hydrated with an ethanol gradient, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE). Sections were observed using a light microscope and reviewed histologically in a blinded fashion.

Flow cytometry

Mesenteric lymph nodes (mLNs) were collected from mice, then lymph node single-cell suspensions were prepared and stained for fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis. Cells were stained with CD103-FITC, CD11c-PE, CD40-APC, CD80-eflour710, and PD-L1-PE-Cyanine7 to detect DCs. Cells were stained for surface markers using CD4-FITC, CD25-PE Cy7, and PD1-APC (eBioscience, Carlsbad, CA, USA) to detect Tregs. Cells were then incubated with fixation/permeabilization reagents in the dark for 30–60 min at room temperature, after which they were washed at least twice with permeabilization reagents and treated with Foxp3-PE, and Helios-eFlour 450 staining (eBioscience, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used for intracellular labeling. Stained cells were analyzed using the BD FACSCanto system (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), and the data were analyzed by FlowJo 10.7 software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR).

Microbiome analysis

Fresh mouse feces were collected aseptically and stored at −80 °C. DNA was extracted from the fecal samples using the QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (QIAgen, Valencia, CA, USA) and then the concentration of DNA was detected (260/A280 = 1.8–2.0 ng/μl). The V3–V4 hypervariable region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified with universal primers using an ABI GeneAmp® 9700 PCR thermocycler (ABI, CA, USA). After removing chimeric sequences, operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were classified based on the 97% similarity of valid sequences across all samples. Sample diversity was assessed using the Shannon index and Simpson index; differences in the composition of the gut microbiota between groups and samples were analyzed using principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) and principal component analysis (PCA). Based on linear discriminant analysis effect size analysis method (LEfSe), it identifies the main contributing bacteria responsible for differences in samples and analyzes different species at the phylum and genus level using STAMP and R (http://www.R-project.org/). 16S rRNA sequencing data are available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA815920.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed statistically using SPSS software (version 22.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and presented as means ± SEM. Differences between multiple experimental groups were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with LDS-t multiple comparison tests. Non-parametric analysis was carried out using the Mann-Whitney test and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Correlations between biomarkers, PD-1/PD-L, and gut microbiota were analyzed using Spearman's analysis. P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

FMT alleviated allergic symptoms in FA mice

The FA-M group showed a significant decrease in body weight compared to the control group. After FMT treatment, the weight gain of the mice was greater than that of the FA-M group (Fig. 1B). Compared to the control group, the mice in the FA-M group showed obvious states of repeated nose scratching, face rubbing, reduced activity, and diminished response to stimuli; compared with the FA-M group, the symptoms in the FA-FMT group were significantly alleviated. FMT could significantly ease the allergic symptom scores of FA mice compared with the FA-M group (Fig. 1C). Mice in the FA-M group exhibited significant diarrhea compared to the control group, whereas the diarrhea scores of mice were significantly reduced after FMT treatment compared to the FA-M group (Fig. 1D).

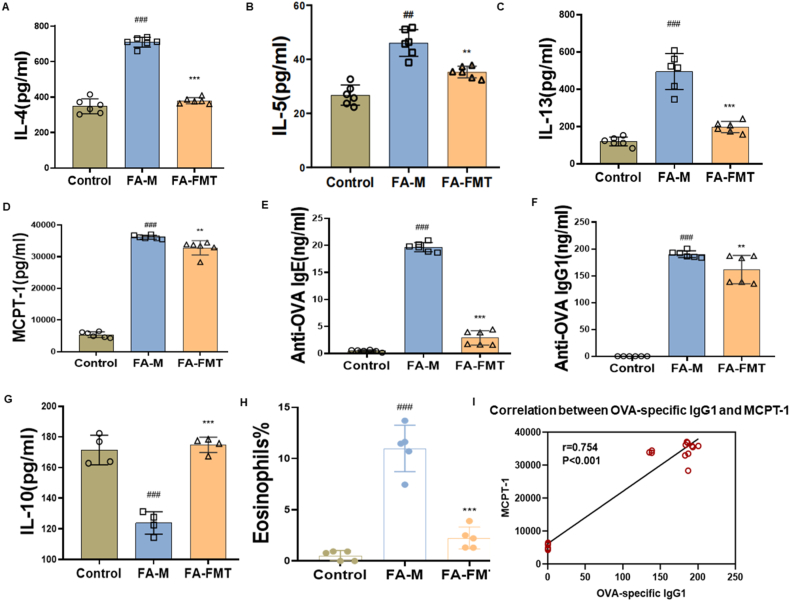

FMT reduced OVA-induced allergic inflammation in FA mice

Mice serum was collected to detect Th2-related cytokines and mMCP-1. Serum levels of IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and mMCP-1 (Fig. 2A–D), as well as OVA-specific IgE and OVA-specific IgG1 (Fig. 2E and F), were significantly elevated in the FA-M group compared with the control group; all of the above indexes were significantly reduced in the FA-FMT group compared with the FA-M group. However, IL-10 levels were reduced in the FA-M group and significantly increased in the FA-FMT group (Fig. 2G). It was also observed that eosinophils were significantly reduced in the FA-FMT group compared to the FA-M group (Fig. 2 H). In addition, OVA-specific IgG1 showed a significant positive correlation with MCPT-1 (Fig. 2I).

Fig. 2.

Effect of FMT on OVA-induced serum inflammation in FA mice. Interleukin-4, IL-4 (A, n = 6). Interleukin-5, IL-5 (B, n = 6). Interleukin-13, IL-13 (C). (D, n = 6). Circulating mast cell protease 1, MCPT-1 (D, n = 6). Immunoglobulin E, IgE (E, n = 6). Immunoglobulin G1, IgG1 (F, n = 6). Interleukin-10, IL-10 (G, n = 4). Eosinophils in blood (H, n = 5). The correlation between OVA-specific IgG1 and MCPT-1 (I, n = 36). #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 FA-M group vs Control group, and ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 FA-FMT group vs FA-M group. FA-M, food allergy model mice. FA-FMT, food allergy mice gavage with fecal microbiota transplantation

FMT inhibited the inflammation of the intestinal in FA mice

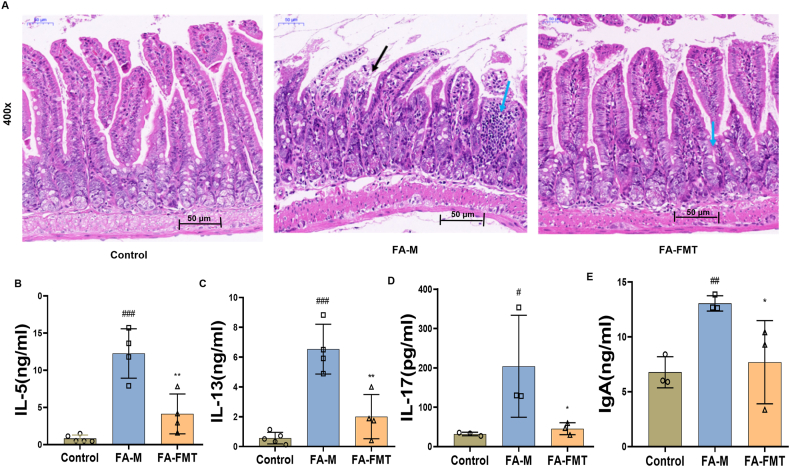

The HE staining of intestinal tissues showed that compared to the control group, the infiltration of inflammatory cells in the FA-M group increased significantly (as shown by blue arrows), and the intestinal epithelium was detached and eroded (as shown by black arrows in the figure); compared to the FA-M group, mice in the FA-FMT group had a relatively mild intestinal inflammatory response, less inflammatory cell infiltration, and no significant structural damage (Fig. 3A). Compared with the control group, IL-5, IL-13, IL-17, and IgA in the small intestine were significantly increased in FA mice. Surprisingly, IL-5, IL-13, and IL-17 were significantly decreased in the FA-FMT group compared with the FA-M group (Fig. 3B–E).

Fig. 3.

Effect of FMT on intestinal inflammation in FA mice. HE staining of intestinal tissues in FA mice (A, 400x). IL-5 in small intestine (B, n = 4). IL-13 in small intestine (C, n = 4). IL-17 l in small intestine (D, n = 3). IgA level in small intestine (E, n = 3). #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 FA-M group vs Control group, and ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 FA- FMT group vs FA-M group. IL-5, Interleukin-5. IL-17, Interleukin-17. IgA, Immunoglobulin A. FA-M, food allergy model mice. FA-FMT, food allergy mice gavage with fecal microbiota transplantation

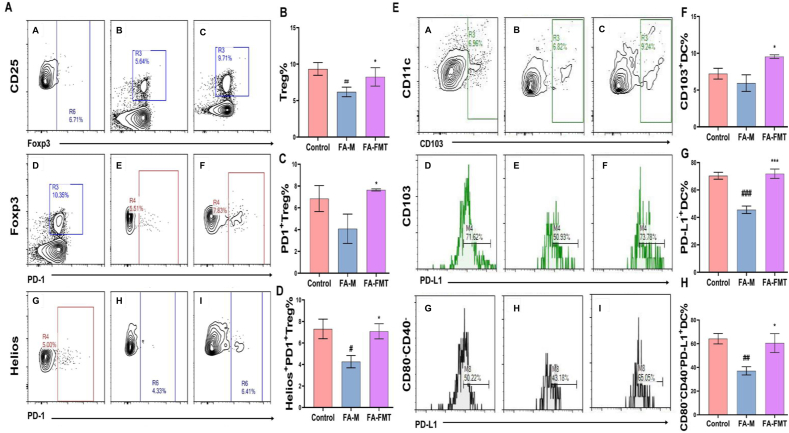

FMT increased the CD103+DCs, the accumulation of Tregs, and the expression of PD-1/PD-L1 in FA mice

In mLNs, the levels of Tregs and their surface PD-1 expression, as well as Helioxs + PD-1+Tregs, were significantly lower in the FA-M group compared to the control group. Conversely these were notably higher in the FA-FMT group compared to the FA-M group (Fig. 4A–D). Compared with the control group, levels of CD103+DCs in mLNs in the FA-M group did not change significantly, but PD-L1 levels on the surface of CD103+DCs and CD103+CD80−CD40−DCs decreased significantly. PD-L1 levels on the surface of CD103+DCs and CD103+CD80−CD40−DCs, and the levels of CD103+DCs in the FA-FMT group increased significantly compared with the FA-M group (Fig. 4E–H).

Fig. 4.

Effect of FMT on Treg and DCs and their PD-1/PD-L1 expression in mLNs (n = 3). The gating strategy of Tregs (A). A, D, G: control group; B, E, H: FA-M group; C, F, I: FA-FMT group. Frequency of Treg cells in MLN (B). The frequency of PD-1+ Treg cells among Treg cells in MLN (C). The frequency of Helios+PD-1+ Treg cells among Treg cells in MLN (D). The gating strategy of DCs (E). Frequency of CD103+DC cells in MLN (F). The frequency of PD-L1+DC cells among DC cells in MLN (G). The frequency of CD80−CD40−PD-L1+DC cells among DC cells in MLN (H). #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 FA-M group vs Control group, and ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 FA-FMT group vs FA-M group. FA-M, food allergy model mice. FA-FMT, food allergy mice gavage with fecal microbiota transplantation

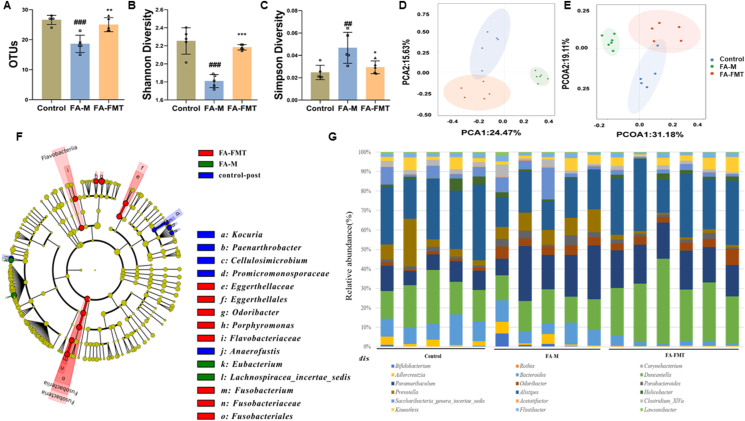

FMT modulated the gut microbiota in FA mice

In the FA-M group, OTUs (Fig. 5A) and Shannon index (Fig. 5B) decreased significantly, and Simpson index (Fig. 5C) increased significantly compared to the control group. In the FA-FMT group, the OTUs, Shannon index increased significantly, and Simpson index reduced significantly compared to the FA-M group. PCA and PCoA results showed that FA-FMT was closer to the control group than FA-M, indicating that the microbiome composition of the FA-FMT group was more similar to that of the control group (Fig. 5D and E). Further research, we compared the relative contribution of differential taxa and used LEfSe to detect key taxa that contributed to the differences between the groups. A total of 15 different taxa at different levels were identified with significant differences in abundance between the three groups (Fig. 5F). In the control group, key taxa that contributed to the differences between groups were Kocuria, Paenarthrobacter, Cellulosimicrobium, Promicromonosporaceae and Anaerofustis; In the FA-M group, Eubacterium and Lachnospiracea-incertae-sedis were key taxa that contributed to the differences between groups. The key taxa in the FA-FMT group that contributed to the differences between groups were Eggerthellaceae, Eggerthellales, Odoribacter, Porphyromonas, Flavobacteriaceae, Fusobacterium, Fusobacteriaceae and Fusobacteriales. Fig. 5G showed the difference in the composition of the microbiota at each taxonomic level in the three groups.

Fig. 5.

Effect of FMT on the composition and diversity of gut microbiota in FA mice (n = 5). Change in OTUs between three groups (A). Analysis of alpha diversity of gut microbiota by Shannon analysis (B). Analysis of alpha diversity of gut microbiota by Simpson analysis (C). PCA plots of beta diversity based on Bray-Curtis distance analysis in different groups (D). PCoA plots of beta diversity based on weighted UniFrac analysis in different groups (E). Differential taxa identified by linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe, F). Composition and relative abundance of microbiota at different taxonomic levels (G). ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 FA-M group vs Control group, and ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 FA-FMT group vs FA-M group. OTUs, Operational taxonomic units. PCoA, Principal coordinate analysis. PCA, Principal component analysis; FA-M, food allergy model mice. FA-FMT, food allergy mice gavage with fecal microbiota transplantation

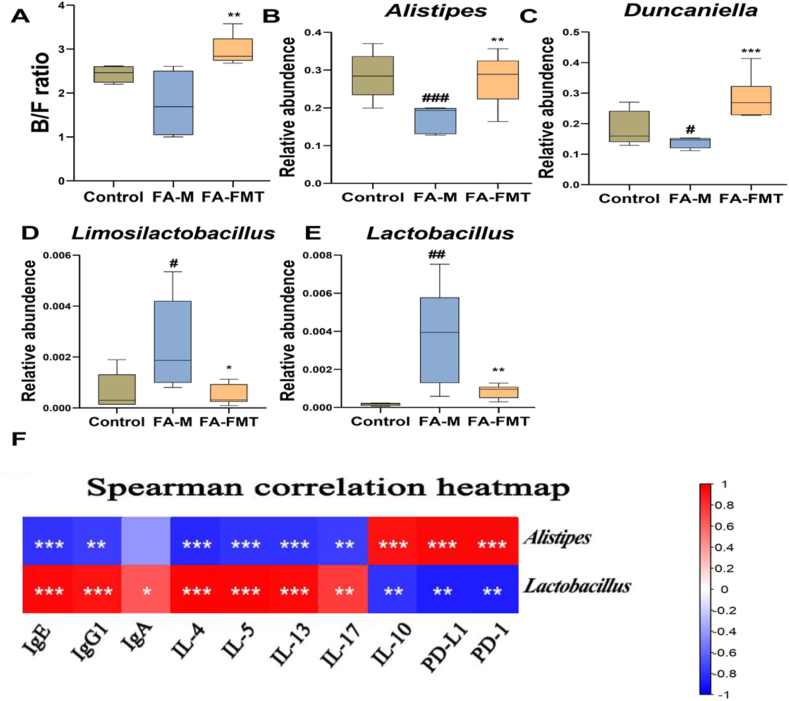

In addition, we analyzed species with significant differences at the phylum level among the groups and found that in the FA-M group mice, Bacteroidetes decreased but Firmicutes increased, and compared with the model group, FMT treatment changed this difference (Fig. 6A). At the genus level, compared with the control group, the relative abundance of Alistipes and Duncaniella decreased, while that of Limosilactobacillus and Lactobacillus increased in the FA-M group. Compared with the FA-M group, the relative abundance of Alistipes and Duncaniella increased (Fig. 6B and C), while that of Limosilactobacillus and Lactobacillus decreased in the FA-FMT group (Fig. 6D and E).

Fig. 6.

Effect of FMT on the relative abundance of bacteria at the phylum and genus levels in FA (n = 5). Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes (B/F) ratio (A). Alistipes (B). Duncaniella (C). Limosilactobacillus (D). Lactobacillus (E). Heatmap of the correlation between microbiota and other experimental results, 0 to 1 means a positive correlation, and 0 to −1 represents a negative correlation (F). #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 FA-M group vs Control group, and ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 FA-FMT group vs FA-M group. FA-M, food allergy model mice. FA-FMT, food allergy mice gavage with fecal microbiota transplantation

FMT improved FA was associated with gut microbiota in FA mice

The results showed that the abundance of Lactobacillus and Limosilactobacillus was significantly positively correlated with IgE, IgG1, and IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IL-17. Furthermore, the abundance of Lactobacillus and Limosilactobacillus was significantly negatively correlated with IL-10, PD-1, and PD-L1. We found the opposite result in Alistipes. In addition, we also found that the abundance of Lactobacillus was significantly positively correlated with IgA (Fig. 6F).

Discussion

FMT treatment was considered to alleviate allergies and decrease diarrhea scores in mice. The most common type of FA is an IgE-mediated hypersensitive reaction to food that is closely related to the Th2 immune response. Several key cytokines such as, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, play an important role in the production of IgE.23 We discovered that FMT has the ability to inhibit IgE and Th2-mediated inflammation. IL-10 is an inhibitory cytokine that plays a regulatory role from the beginning of immune initiation, limiting inflammation to a certain range.24 Beneficially, we found elevated levels of IL-10 after FMT administration. Consistent with the Coomes' study that IL-10 directly regulates Th2 cells and decreases Th2 cell levels in over airway allergic inflammation.25 Our results found a reduction in IgG1 levels in the FMT group. High levels of specific IgG1 in mice are associated with a strongly specific Th2 response, which can trigger allergic reactions in sensitive individuals. IgG antibodies were also noted to activate mast cells.26 Antigen-specific IgE and IgG1 antibodies are systemic manifestations of Th2-type immune responses.27 There was a reduction in serum eosinophils and MCPT-1 in the FMT group. Research found mast cells can lead to allergies, inflammation, and autoimmune diseases.28 Serum MCPT-1 level is related to systemic mast cell activation, and MCPT-1 promotes mucosal permeability in intestinal allergic reactions.29 Moreover, OVA-specific IgG1 showed a significant positive correlation with MCPT-1, this suggests that elevated OVA-specific IgG1 activates mast cells and is one of a cause of FA.

Treg cells have an important role in mucosal immune tolerance and maintenance.30 The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is indispensable for regulating the inflammatory response to allergy. Recent studies found that PD-1 and its ligands play a part in regulating T cell activation and function.31 In this study, Tregs in mLNs were substantially increased in the FMT group, and the levels of PD-1 on the surface of Tregs and Helios+PD-1+Tregs were also increased. Similarly, research found that PD-1 expression in combination with PD-L1 restored tolerance in food-allergic mice.32 We also found that the number of CD103+DCs and their surface PD-L1 were significantly elevated in the FA-FMT group. Studie showed that the CD103+ DC subset mainly induces regulatory T cells, whereas PD-L1-deficient mice fail to induce regulatory T cells in the MLN.31 Helios + Treg cells were found to have greater suppression and more stable Foxp3 expression.33 PD-L1 expressed on dendritic cells is a key mediator of tolerance and regulation of germinal center effector cells and can inhibit the initial activation of reactive CD4+T cells.11 We further found that expression of PD-L1 on the surface of CD103+CD80−CD40−DCs was significantly increased after FMT treatment, suggesting that a subpopulation of CD103+CD80−CD40−DCs may play an important role. Related studies showed that dendritic cells expressing lower levels of co-stimulatory molecules produce higher levels of IL-10.34 The research noted that the gut microbiota affects the immune function of the body by regulating PD-L1 levels.35

Ecological dysbiosis of the gut microbiome can cause dramatic immune imbalances and disturbances in the immune microenvironment, which consequently lead to different diseases, especially during early life.36 A reduction in the diversity of gut microbiota is a risk factor for allergies.37 Our results showed that FMT treatment increased gut microbiota diversity in FA mice. After FMT treatment, the composition of the gut microbiota was improved, which is in accordance with the findings of Trompette et al.37 Abdel-Gadir et al. found a protective effect of Bacteroidetes against FA,38 and a clinical study found a decrease in Bacteroidetes and an increase in Firmicutes in the gut of children with food allergies.39 Importantly, FMT treatment changed the ratio of Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes (B/F) in our study. The research showed that Bacteroidetes decreased serum IgE levels, increased sIgA levels, attenuated Th2-type inflammatory responses, and increased Treg levels in mice.40 But, how could the altered gut microbiome by FMT induce the expression of CD103+DCs and PD-L1? Research found that therapeutic FMT initiates the restoration of intestinal homeostasis through the simultaneous activation of different immune-mediated pathways, ultimately leading to IL-10 production by innate and adaptive immune cells, including CD4+ T cells, iNKT cells and Antigen Presenting Cells (APC), and reduces the ability of dendritic cells, monocytes and macrophages to present MHCII-dependent bacterial antigens to colonic T cells.41 In addition, FMT regulated γδ T cells via DC-T regulatory cell interaction, and induced metabolic reprogramming in DCs.42 Intestinal DCs directly sample lumen contents and microbes,43 migrating to mLNs where they can induce Treg polarization.44 Studies indicate that FMT increases probiotics that act on DCs in mLNs. Upon phagocytosing probiotics, DCs adopt an immunosuppressive phenotype, producing more IL-10 while producing less IL-12 and TNF-α.45,46 The observed increase in suppressive DCs after FMT in mLNs, further confirmed in vitro, suggests microbiome-mediated induction of a regulatory phenotype in intestinal DCs.42 Numerous studies have shown that the gut microbiota can serve as a novel biomarker to predict responses to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy. However, further in-depth research is needed to elucidate how could the altered gut microbiome by FMT induce the expression of PD-L1.

After FMT treatment, beneficial bacteria such as Alistipes and Duncaniella increased. Alistipes are found primarily in the healthy human gut microbiota as a potential short-chain fatty acid maker (SCFA), and SCFA can reduce intestinal inflammation.47 Also, Alistipes showed a positive correlation with IL-10, PD-1/PD-L, and showed a negative correlation with IgE, IgG1, Il-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IL-17, indicating that Alistipes may play a role in the reduction of inflammation in FA mice. Harmful bacteria such as Lactobacillus decreased after FMT treatment. Cosenza et al. similarly observed that the abundance of Lactobacillus significantly increased and the abundance of Alistipes significantly decreased in the FA mice at the genus level.39 Moreover, Lactobacillus showed a positive correlation with IgE, IgG1, Il-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IL-17 and a negative correlation with IL-10 and PD-1/PD-L, revealing that Lactobacillus proliferation exacerbates FA inflammation. Dunaliella is found in the healthy mouse intestine and plays a protective role in the development of intestinal inflammation.39, which was increased after FMT treatment.

Conclusion

FMT restored the disturbed gut microbiota, increased the diversity of the microbiota, reduced allergic inflammation in FA mice by increasing beneficial bacteria or reducing harmful bacteria, and brought it into a healthy state. After FMT treatment, intestinal inflammation, Th2 type cytokine, and OVA-specific antibody levels were significantly reduced in FA mice. Meanwhile, FMT also induced CD103+ DCs and expression of PD-L1 on its surface in mLNs. High levels of PD-L1 promoted the production of Tregs through the PD-L1/PD-1 pathway. However, this study still has some limitations, such as elucidating how FMT changes the gut microbiome to induce CD103+ DC and PD-L1 expression. To further elucidate the role of PD-1/PD-L1 in the treatment of FA with FMT, future studies will involve further validation of this pathway using blocking antibodies and obtaining knockout mice. Summary, the possible mechanism of FMT alleviating allergic diseases is that the interaction between normal microbiota and intestinal mucosa raises the PD-L1 level on the surface of CD103+ DCs, and may play an immunomodulatory role through the PD-L1/PD-1 pathway in promoting the differentiation of Tregs, which in turn alleviates the Th2-type immune response and reduces the IgE level. And in this process, the CD103+ CD80− CD40− DCs subpopulation may play an important regulatory role.

Abbreviations

FA, Food allergy; FMT, Fecal microbiota transplantation; Ovalbumin, OVA; PD-L1, Programmed cell death ligand 1; PD-1, Programmed cell death protein 1; IgE, Immunoglobulin E; OIT, Oral immunotherapy; IL-4, 5, 10, 13, 17, Interleukin 4, 5, 10, 13, 17; ELISA, Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; MCPT-1, Mast cell protease 1; HE, Hematoxylin-eosin; mLNs, Mesenteric lymph nodes; OTUs, Operational taxonomic units; PCoA, Principal coordinate analysis; PCA, Principal component analysis; LEfSe, Effect size analysis method.

Funding source

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82170026); Shaanxi Province Technological Innovation Guidance Special Project (2022QFY01-09); Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province (2022JQ-764) and the Discipline Promotion Project of Xijing Hospital (XJZT21L11).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Xin Sun and Xingzhi Wang designed the study. Jinli Huang wrote the first draft of the manuscript, collected the data and interpreted of results. Juan Zhang and Hui Su performed the statistical analysis and critically revised the work. Cheng Wu, Yuanyuan Jia, Panpan Zhang, and Qiuhong Li commented on several drafts.

Ethics statement

All animal procedures and experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Research Ethics Committee of the Fourth Military Medical University.

Authors’ consent for publication

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

Nothing to declare.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank our funding source, thankful to Department of Pediatrics, Xijing Hospital, the Fourth Military Medical University for providing the various resources for completion of the current article, and Yue Zhang for statistical analysis help.

Footnotes

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

Contributor Information

Hui Su, Email: Huisu2014@163.com.

Xin Sun, Email: sunxin6@fmmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Barni S., Liccioli G., Sarti L., Giovannini M., Novembre E., Mori F. Immunoglobulin E (IgE)-Mediated food allergy in children: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, prevention, and management. Medicina (Kaunas) 2020;56:111. doi: 10.3390/medicina56030111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyons S.A., Clausen M., Knulst A.C., et al. Prevalence of food sensitization and food allergy in children across Europe. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:2736–2746.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Devdas J.M., Mckie C., Fox A.T., Ratageri V.H. Food allergy in children: an overview. Indian J Pediatr. 2018;85:369–374. doi: 10.1007/s12098-017-2535-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luo J.Z., Zhang Q.Y., Gu Y.J., et al. Meta-analysis: prevalence of food allergy and food allergens - China, 2000-2021. China CDC Wkl. 2022;4:766–770. doi: 10.46234/ccdcw2022.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barni S., Liccioli G., Sarti L., Giovannini M., Novembre E., Mori F. Immunoglobulin E (IgE)-Mediated food allergy in children: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, prevention, and management. Medicina. 2020;56:111. doi: 10.3390/medicina56030111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sancakli O., Akın Aslan A. Effects of elimination diets and clinical findings on mothers' anxiety in infants with food allergy with non-life-threatening reactions. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;54:108. doi: 10.23822/EurAnnACI.1764-1489.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arasi S., Castagnoli R., Pajno G.B. Oral immunotherapy in pediatrics. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2020;31:51–53. doi: 10.1111/pai.13159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou B., Yuan Y., Zhang S., et al. Intestinal flora and disease mutually shape the regional immune system in the intestinal tract. Front Immunol. 2020;11:575. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muraro A., Silva D.D., Halken S., et al. Managing foodallergy: GA2LEN guideline 2022. World Allergy Organ J. 2022;15 doi: 10.1016/j.waojou.2022.100687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donald K., Finlay B.B. Early-life interactions between the microbiota and immune system: impact on immune system development and atopic disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2023;23:735–748. doi: 10.1038/s41577-023-00874-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao W., Ho H., Bunyavanich S. The gut microbiome in food allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;122:276–282. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2018.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldberg M.R., Mor H., Magid Neriya D., et al. Microbial signature in IgE-mediated food allergies. Genome Med. 2020;12:92. doi: 10.1186/s13073-020-00789-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bunyavanich S., Berin M.C. Food allergy and the microbiome: current understandings and future directions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144:1468–1477. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galván Morales M.A., Montero-Vargas J.M., Vizuet-de-Rueda J.C., Teran L.M. New insights into the role of PD-1 and its ligands in allergic disease. IJMS. 2021;22 doi: 10.3390/ijms222111898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun C., Mezzadra R., Schumacher T.N. Regulation and function of the PD-L1 checkpoint. Immunity. 2018;48:434–452. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steelant B., Seys S.F., Gerven L.V., et al. Histamine and T helper cytokine-driven epithelial barrier dysfunction in allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:951–963.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheetal Bodhankar S., Vandenbark A.A., Offner H. Oestrogen treatment of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis requires 17β-oestradiol-receptor-positive B cells that up-regulate PD-1 on CD4+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Immunology. 2012;137:282–293. doi: 10.1111/imm.12013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Routy B., Le Chatelier E., Derosa L., et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1–based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science. 2018;359:91–97. doi: 10.1126/science.aan3706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parker A., Romano S., Ansorge R., et al. Fecal microbiota transfer between young and aged mice reverses hallmarks of the aging gut, eye, and brain. Microbiome. 2022;10:6. doi: 10.1186/s40168-022-01243-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao Z., Ning J., Bao X., et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation protects rotenone-induced Parkinson's disease mice via suppressing inflammation mediated by the lipopolysaccharide-TLR4 signaling pathway through the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Microbiome. 2021;9:226. doi: 10.1186/s40168-021-01107-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamaki K., Yoshino S. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib relieves systemic and oral antigen-induced anaphylaxes in mice. Allergy. 2012;67:114–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma S., Sethi G.S., Naura A.S. Curcumin ameliorates ovalbumin-induced atopic dermatitis and blocks the progression of atopic march in mice. Inflammation. 2020;43:358–369. doi: 10.1007/s10753-019-01126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee C., Hong S.N., Paik N.Y., et al. CD1d modulates colonic inflammation in NOD2−/− mice by altering the intestinal microbial composition comprising Acetatifactor muris. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis. 2019;13:1081–1091. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagata K., Nishiyama C. IL-10 in mast cell-mediated immune responses: anti-inflammatory and proinflammatory roles. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:4972. doi: 10.3390/ijms22094972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coomes S.M., Kannan Y., Pelly V.S., et al. CD4+ Th2 cells are directly regulated by IL-10 during allergic airway inflammation. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10:150–161. doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shamji M.H., Valenta R., Jardetzky T., et al. The role of allergen-specific IgE, IgG and IgA in allergic disease. Allergy. 2021;76:3627–3641. doi: 10.1111/all.14908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanagaratham C., El Ansari Y.S., Lewis O.L., Oettgen H.C. IgE and IgG antibodies as regulators of mast cell and basophil functions in food allergy. Front Immunol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.603050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dong J., Chen L., Zhang Y., et al. Mast cells in diabetes and diabetic wound healing. Adv The. 2020;37:4519–4537. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01499-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kordowski A., Reinicke A.T., Wu D., et al. C5a receptor 1-/- mice are protected from the development of IgE-mediated experimental food allergy. Allergy. 2019;74:767–779. doi: 10.1111/all.13637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanoue T., Atarashi K., Honda K. Development and maintenance of intestinal regulatory T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:295–309. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galván Morales M.A., Montero-Vargas J.M., Vizuet-de-Rueda J.C., Teran L.M. New insights into the role of PD-1 and its ligands in allergic disease. IJMS. 2021;22 doi: 10.3390/ijms222111898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanaka R., Ichimura Y., Kubota N., et al. Differential involvement of programmed cell death ligands in skin immune responses. J Invest Dermatol. 2022;142:145–154.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2021.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thornton A.M., Shevach E.M. Helios: still behind the clouds. Immunology. 2019;158:161–170. doi: 10.1111/imm.13115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao L., Wang H., Thomas R., et al. NK cells modulate T cell responses via interaction with dendritic cells in Chlamydophila pneumoniae infection. Cell Immunol. 2020;353 doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2020.104132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nie D., Fang Q., Cheng J., et al. The intestinal flora of patients with GHPA affects the growth and the expression of PD-L1 of tumor. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2022;71:1233–1245. doi: 10.1007/s00262-021-03080-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dai Z., Zhang J., Wu Q., et al. Intestinal microbiota: a new force in cancer immunotherapy. Cell Commun Signal. 2020;18:90. doi: 10.1186/s12964-020-00599-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akagawa S., Kaneko K. Gut microbiota and allergic diseases in children. Allergol Int. 2022;71:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2022.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abdel-Gadir A., Stephen-Victor E., Gerber G.K., et al. Microbiota therapy acts via a regulatory T cell MyD88/RORγt pathway to suppress food allergy. Nat Med. 2019;25:1164–1174. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0461-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cosenza L., Nocerino R., Di Scala C., et al. Bugs for atopy: the Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG strategy for food allergy prevention and treatment in children. Benef Microbes. 2015;6(2):225–232. doi: 10.3920/BM2014.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim I.S., Lee S.H., Kwon Y.M., et al. Oral administration of ¥ glucan and Lactobacillus plantarum alleviates atopic dermatitis-like symptoms. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2019;29:1693–1706. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1907.07011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burrello C, Garavaglia F, Cribiù FM, Ercoli G, Lopez G, Troisi J, et al. Therapeutic faecal microbiota transplantation controls intestinal inflammation through IL10 secretion by immune cells. Nat Commun 201;9(1):5184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Geng H.Y., Zhang H.B., Cheng L.F., Dong S.M. Sivelestat ameliorates sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction by activating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Int Immunopharm. 2024;131 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2023.111466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jung C., Hugot J.P., Barreau F. Peyer's patches: the immune sensors of the intestine. Int J Inflamm. 2010;2010 doi: 10.4061/2010/823710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Houston S.A., Cerovic V., Thomson C., Brewer J., Mowat A.M., Milling S. The lymph nodes draining the small intestine and colon are anatomically separate and immunologically distinct. Mucosal Immunol. 2016;9(2):468–478. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Comi M., Avancini D., Santoni de Sio F., et al. Coexpression of CD163 and CD141 identifies human circulating IL-10-producing dendritic cells (DC-10) Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17(1):95–107. doi: 10.1038/s41423-019-0218-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sela U., Park C.G., Park A., et al. Dendritic cells induce a subpopulation of IL-12rβ2-expressing treg that specifically consumes IL-12 to control Th1 responses. PLoS One. 2016;11(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parker B.J., Wearsch P.A., Veloo A.C.M., Rodriguez-Palacios A. The genus Alistipes: gut bacteria with emerging implications to inflammation, cancer, and mental health. Front Immunol. 2020;11:906. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.