Abstract

Objectives:

Smokeless tobacco (SLT) use is a phenomenon that is detrimental to the health of adults worldwide and dramatically impacts the health of resettled populations. The prevalence of SLT has exponentially grown as a public health threat for the refugee and immigrant populations and is worthy of addressing. This research study examined the SLT cultural drivers of the Texas immigrant and refugee community, which led to their knowledge, perception, awareness, and cessation practices.

Methods:

A convenience sample of refugee and immigrant community members resettled in San Antonio was recruited from the local Health Clinic and Center. Ninety-four consented participants completed a 29-item survey that gathered participants’ demographics, SLT history, beliefs, knowledge, perceptions of the risk, awareness, availability of SLT, and cessation practices influenced by their culture.

Results:

Of the 94 participants, 87.2% identified as Asian or natives of Afghanistan, Myanmar, and Pakistan. 70% reported SLT as a ‘feel good’ or recreational use, while 33% used it to relieve stress. Thirty-five percent stated they continuously use or have the desire to use SLT first thing in the morning. 86.2% perceived SLT products as unsafe for their health, 83% believed that it caused oral cancer and periodontal disease, and 76.6% were aware that SLT contains nicotine. 63.8% wished to stop using them, and 36.2% attempted to quit but were unsuccessful. 54% sought cessation assistance from a family member, 32% from a friend, and only 12% from a healthcare provider.

Conclusion:

SLT use is culturally prevalent within the immigrant and refugee populations. Participants’ quit attempts likely failed due to a lack of professional cessation support that was taxing due to language, interpretation, and literacy barriers. Healthcare providers are well-positioned to offer cessation interventions and reduce SLT use to achieve community well-being pathways.

Keywords: Culture, Oral Health, Health Belief Model, Refugees, Tobacco Use Cessation, Smokeless Tobacco Use

INTRODUCTION

Smokeless tobacco (SLT) use is a health determinant for millions of adults globally, especially those from Southeast Asian ethnic backgrounds.1 Evidence-based tobacco interventions are established pathways to prevent tobacco-related cancer.2,3 Of the 5.7 million adults (2.3%) who consume SLT products in the U.S., individuals of Asian ethnicity have the highest percentage (6.8%) of use.5,6 The 2016 U.S. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System reports males (7.4%) are more likely to use SLT products than females (1.3%) in Texas.7

SLT use varies from inhaling to chewing products, where moist tobacco is placed between cheeks, lips, gums, and nasal cavities.8 Dry snuff powder originates from cured or fermented tobacco leaves.9 Dipping tobacco is shredded leaves that are easily pinched and placed inside the mouth. Snus is the moist tobacco placed behind the upper lip as loose or portioned sachets resembling miniature tea bags.10

Betel quid (Gutka) combines powdered tobacco, areca nut, slaked lime, and catechu.11 Mawa is areca nut, tobacco, and slaked lime, khaini is used with slaked lime, and Chimo is a syrup or paste from Venezuela.12,13 Naswar (Nass) is a dip used by Afghans made from sun-dried, powdered tobacco (N. rustica), ash, oil, flavoring agents (e.g., cardamom, menthol), coloring agents (indigo), and, in some areas, slaked lime placed in the oral cavity to achieve a euphoric sensation.14

Health consequences of SLT use, like cigarette smoking, include impairments in brain neurology that change cognitive and neurobehavioral functions.15 Tobacco-specific nitrosamines are tobacco alkaloids from curing, fermentation, and aging as the most abundant carcinogens in chewing tobacco and snuff SLT products.16

Oral health consequences of SLT use include oral carcinomas and malignant disorders presenting as leukoplakia and erythroplakia.17 Snuff and betel leaf are risk factors for oral cavity cancer.18 SLT use is a predisposing risk factor for tooth decay, tooth loss, and periodontal disease.19,20

Resettlement depends on individuals choosing to move from their native land to live permanently in a foreign country (immigrants) or if they are forced to move (refugees).21 As the resettlements increase due to global conflicts, refugee patients seeking care present with a higher incidence of SLT-related oral lesions.22

Cultural implications of SLT use include activities between family and friends, where traditions, spiritual values, and religious beliefs are formed. SLT use is influenced by accessibility and affordability, except for lower socioeconomic South Asian populations that use SLT products to suppress hunger and boredom.14,23–26 In Saudi Arabia, the use of Shammah (SLT) is culturally and socially bonding family and friends, and in Venezuela, chimó (SLT) is a traditional practice from the pre-Columbian Indian era.27,28 Religion either prohibits SLT use or condones it as a stress-coping mechanism.29

Healthcare providers should be aware of cultural drivers leading to family and peers as primary SLT cessation support. We hypothesized that SLT cessation interventions are feasible when the providers 1) understand their refugee and immigrant patients’ cultural drivers and perspectives promoting SLT use and 2) recognize patient barriers deterring the cessation process.

METHODS

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved this study as HSC20220274EX for this study. The study was funded by a small grant from the Institute for Integration of Medicine and Science (IIMS) Community Engagement Small Project. Verbal and written consent for the study was obtained from all participants.

Participants

Participants were members of San Antonio’s local refugee and immigrant populations, such as any refugee or immigrant community member 18 years and older who used SLT as a lifetime or current practice and consented to participate. Participants were compensated with a $20 gift card for their time.

Ninety-four (n=94) participants were recruited from the San Antonio Refugee Health Clinic and El-Bari Community Health Center, where providers delivered healthcare to this local refugee and immigrant population. The study coordinators visited site-specific Health Fairs to recruit participants with assistance from certified interpreters who addressed language and health literacy barriers. Random participants were approached and asked about SLT product use. Participants who currently or had previously used SLT and consented were informed about the IRB protocol and surveyed.

Survey Design

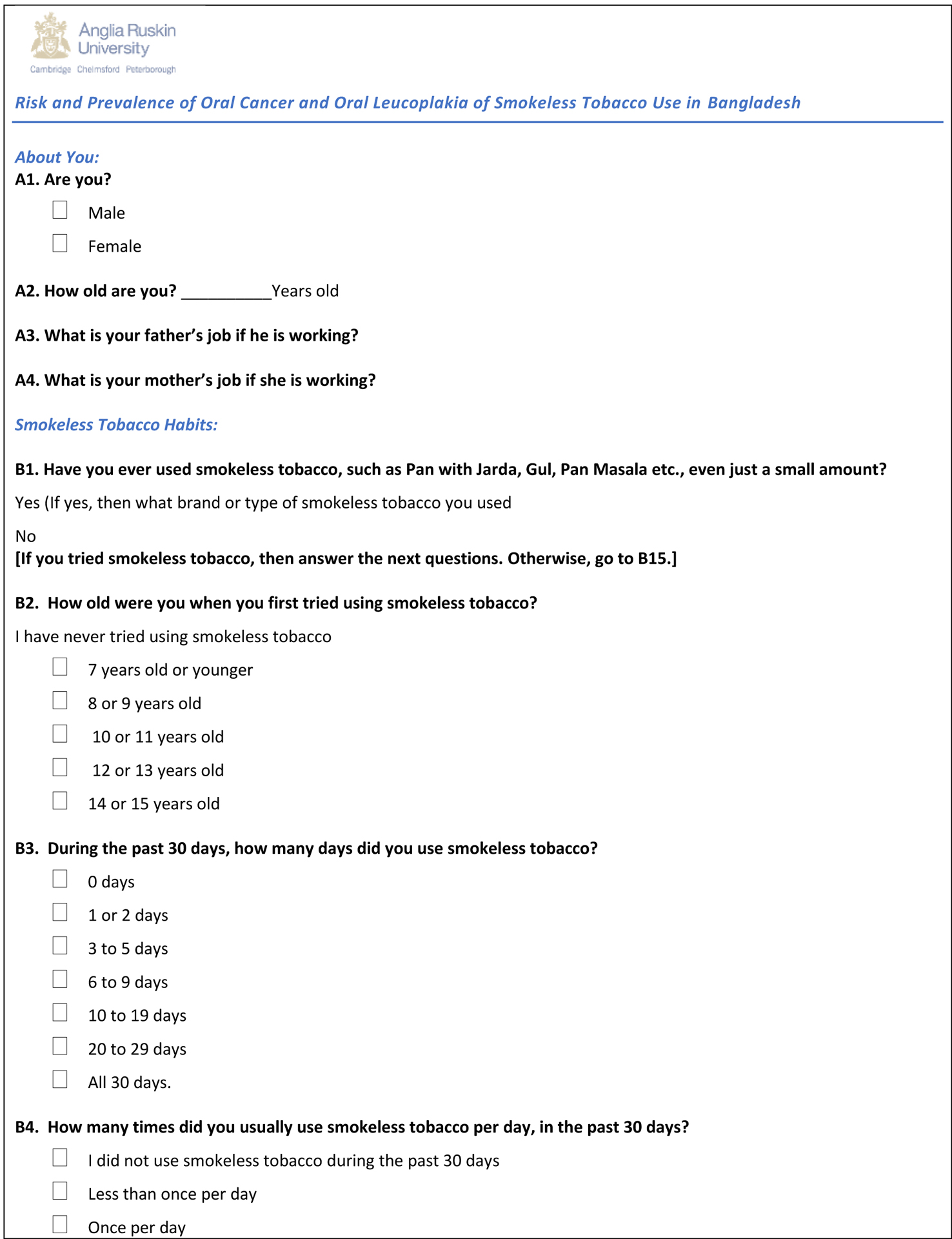

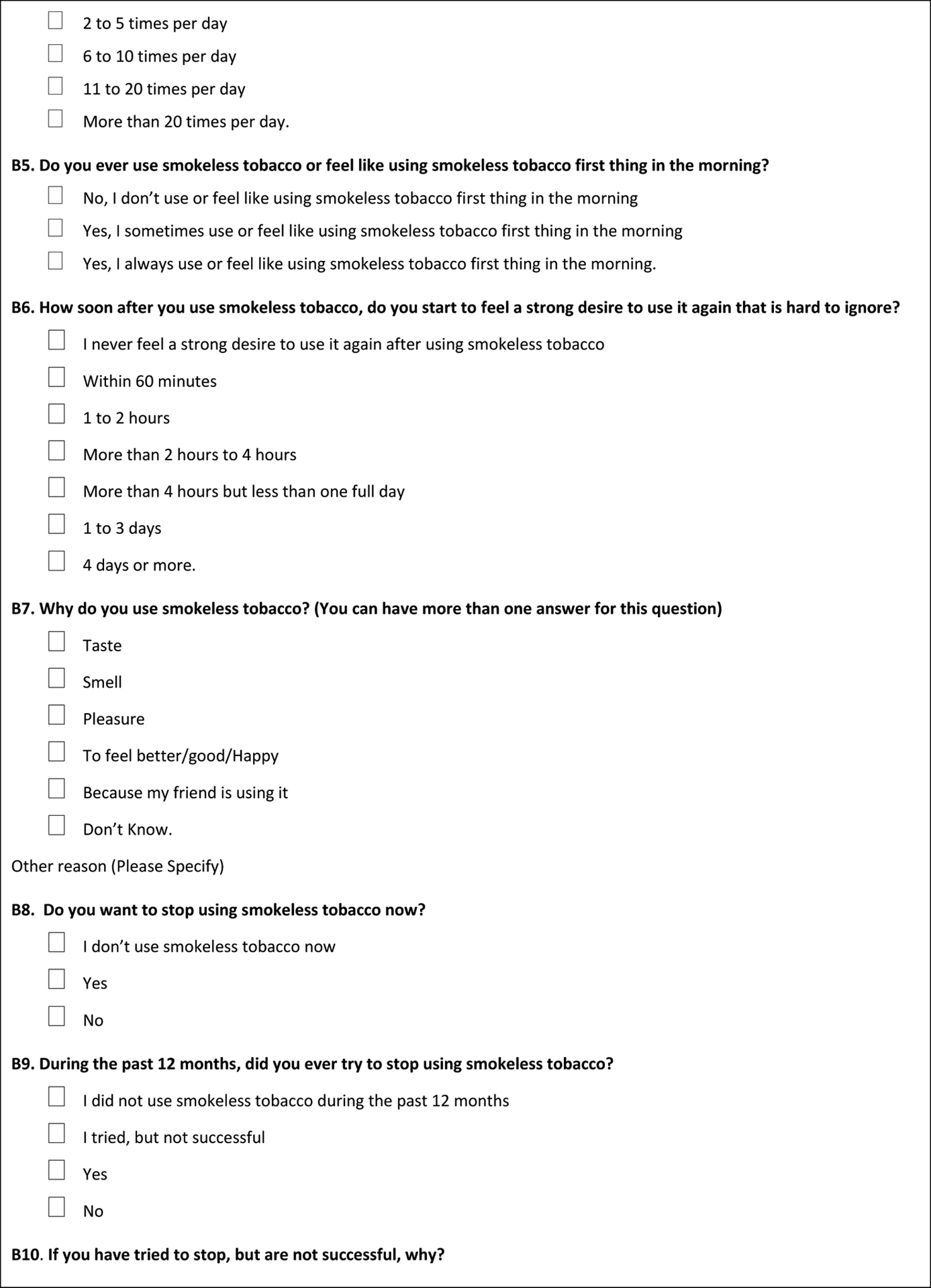

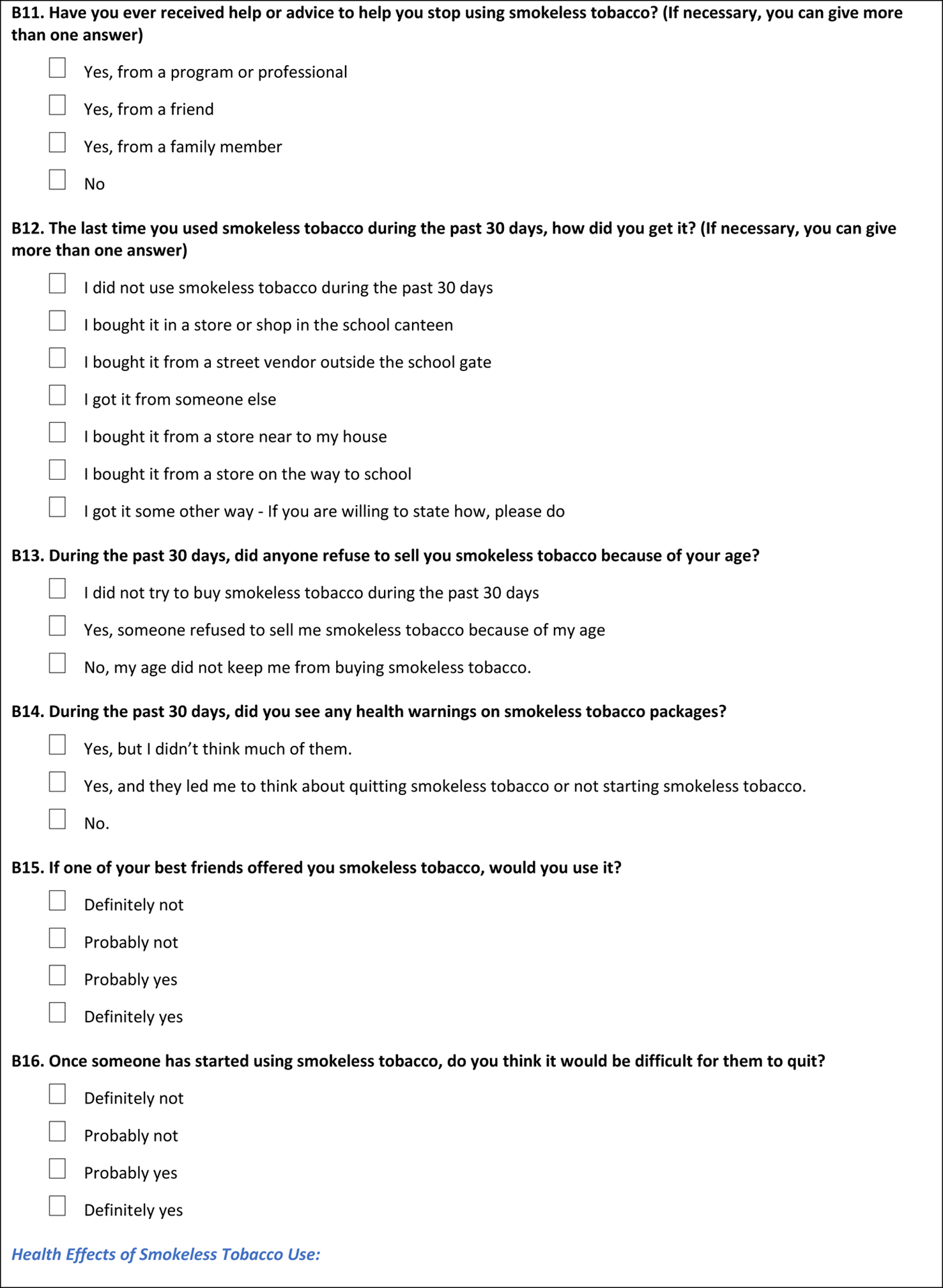

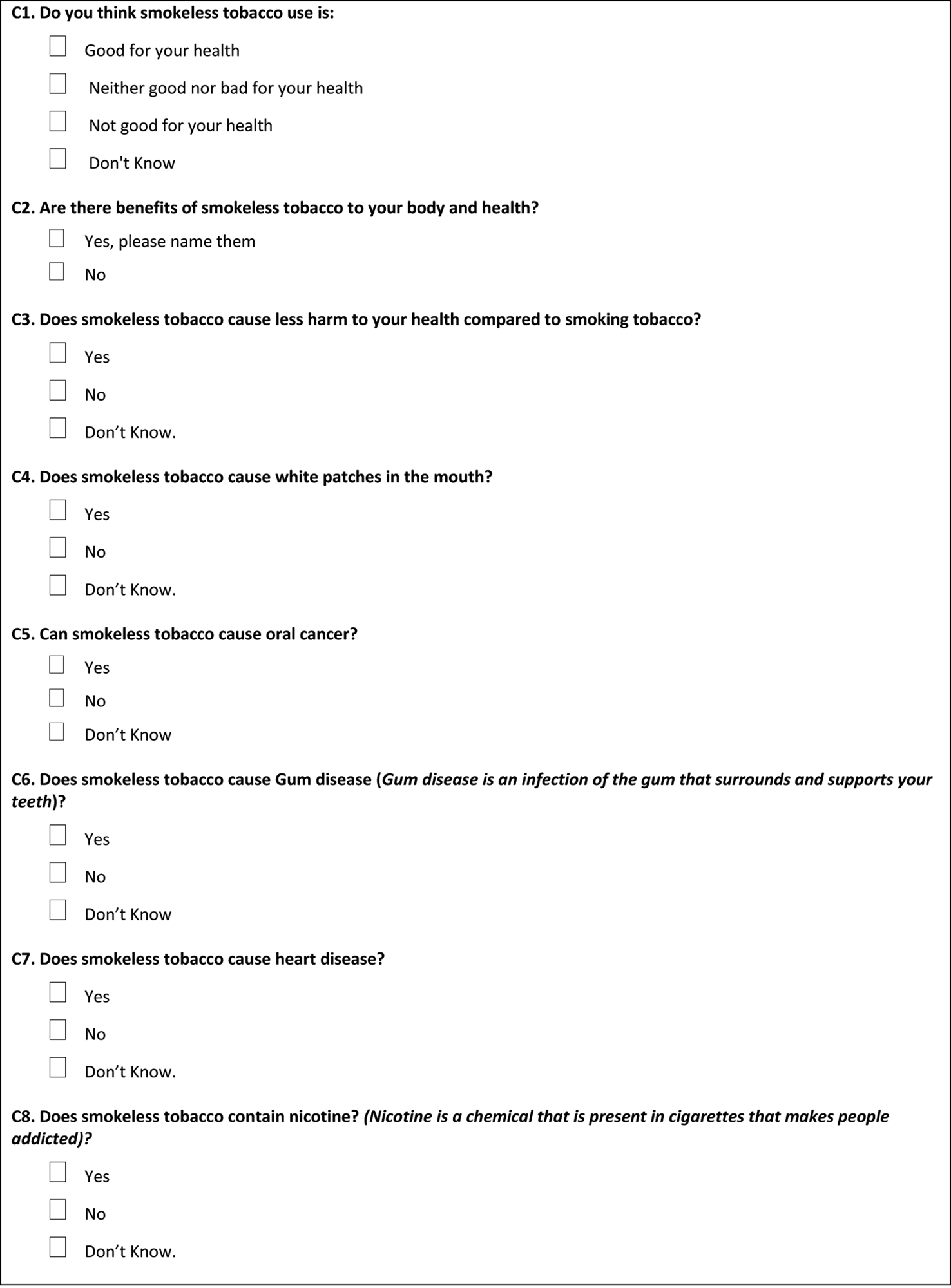

The quantitative survey design included a 29-question multiple-choice, dichotomous, validated survey (Table 1).23 The survey design was a deliberate act to tackle participants’ reading and comprehension since they either spoke English as a second language or used an interpreter to complete survey questions. The survey was also planned with the cultural and linguistic assistance of refugee and immigrant community interpreters as an online REDCap30 web-based link. The design generated a culturally appropriate health-literate and plain language survey with illustrative aptitude.31 The survey gathered participants’ sociodemographic data, history of SLT use, types of SLT products, beliefs, knowledge, perceptions about SLT use, awareness, availability, and SLT cessation practices. The survey blended the cultural and behavioral attitudes, intentions, or motivational factors influencing behavior toward SLT use, adapted from the worldview of Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) and the Health Belief Model (HBM).32,33

Table 1:

THE VALIDATED SURVEY

|

|

|

|

The SCT model emphasizes internal and external influences by which individuals acquire and maintain behavior.32 SCT considers whether behavioral action will occur with expectations that shape whether an individual will engage in a specific behavior and why they engage in that behavior.

For this study, SCT questions related to the effect of social environment on the individual’s health behavior, such as using SLT products, enabled researchers to understand cultural and external factors that affect someone’s decision to use SLT.23 Environmental influences were trended as questions about cultural and religious appeals, social norms, peer pressure, recreational use, and stress. Environmental determinants of health indicated the availability and accessibility of SLT products and exposure to SLT advertisements.

The HBM model construction includes the perceived quitting benefits from a health or social perspective, perceived barriers or potential obstacles to quitting, and perceived self-efficacy as the self-ability to stop smoking.33 HBM derives components of health- related behavior that influence strategies promoting healthy behaviors by preventing and treating health conditions.33 The HBM model also includes the decision-making process of accepting a recommended health action as internal (e.g., wheezing, difficulty swallowing) or external factors (e.g., culturally influenced advice from friends). Finally, this model braces an individual’s confidence in their ability to succeed.

For this study, HBM survey questions were related to understanding motives to partake in SLT use, and reasons for unsuccessful SLT quit attempts.23 Questions about the harmful effects of SLT measured participants’ perceived susceptibility, and items asking about barriers determined reasoning for SLT use. Questions about attitude refer to the degree to which a person has a favorable or unfavorable evaluation of the behavior of interest.

Analysis

The study’s primary goal was to identify the perspectives of recently resettled refugee and immigrant SLT users. Percentages summarized categorical variables, and continuous outcomes defined the medians and interquartile ranges (25th and 75th percentiles). The hypothesis tested was that the characteristics of SLT users would vary by ethnicity. This was assessed using Chi-square tests for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric tests for continuous outcomes. All testing was two-sided at a significance level of p=.05.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic data for the 94 participants trended an age range of 19–78 years, where the majority (87%, n=82) were males compared to (13%, n=12) females. 87.2% self-identified as Asian or natives of Afghanistan, Myanmar, and Pakistan. Participant’s highest level of education obtained varied by their ethnicity (p=.002). 31% (n=29, 36% Asians vs. 0% Latino and 0% Non-Latino White) had completed less than a high school education. Considering higher education, they received associate’s (2.1%, n=2), bachelor’s (15%, n=14), and graduate degrees (11%, n=10). Most had annual incomes less than or equal to $25,000 (57%, n=54). Asian participants reported the lowest income level (64%, n=51) compared to 25% for Latinos, mainly from Venezuela, and 0% for non-Latino whites (p=.014, Table 2).

Table 2.

PARTICIPANT SOCIODEMOGRAPHICS

| Characteristic | Overall, N = 941 |

Asian, N = 801 |

Latinos, N = 121 |

Non-Latino/White N = 21 |

p-value2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smokeless Use | |||||

| Yes | 94 (100%) | 80 (100%) | 12 (100%) | 2 (100%) | |

| Age | 36 (31, 44) | 36 (31, 44) | 38 (34, 48) | 34 (32, 37) | 0.8 |

| Unknown | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Gender | <0.001 | ||||

| Female | 12 (13%) | 6 (7.5%) | 6 (50%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Male | 82 (87%) | 74 (92%) | 6 (50%) | 2 (100%) | |

| Education | 0.002 | ||||

| No education at all | 17 (18%) | 17 (21%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Less than a high school diploma | 29 (31%) | 29 (36%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| High school diploma or GED | 18 (19%) | 15 (19%) | 3 (25%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Some college | 4 (4.3%) | 2 (2.5%) | 1 (8.3%) | ||

| Associate degree | 2 (2.1%) | 1 (1.3%) | 1 (8.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 14 (15%) | 10 (12%) | 3 (25%) | ||

| Graduate degree | 10 (11%) | 6 (7.5%) | 4 (33%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Household Size | 5.00 (3.00, 6.00) | 5.00 (3.00, 7.00) | 5.00 (5.00, 5.25) | 4.00 (3.50, 4.50) | 0.8 |

| Income | 0.014 | ||||

| Up-to (> or = to) $25,000 | 54 (57%) | 51 (64%) | 3 (25%) | 0 (0%) | |

| $25,001-$50,000 | 17 (18%) | 14 (18%) | 3 (25%) | 0 (0%) | |

| $50,001-$100,000 | 8 (8.5%) | 5 (6.2%) | 2 (17%) | 1 (50%) | |

| Over $100,000 | 7 (7.4%) | 6 (7.5%) | 1 (8.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 8 (8.5%) | 4 (5.0%) | 3 (25%) | 1 (50%) |

n (%): Median (IQR)

Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test: Pearson’s Chi-squared test

Smokeless Tobacco (SLT) Use and Beliefs According to the Survey

The frequency of SLT use was highest among the Asian refugee population, or 100% of the participants reported using SLT at some point. More than half (52%, n=49) used SLT every day monthly. SLT use during the past 30 days before the survey ranged from 2–5 times daily (30%, n=28) to 6–10 times a day (16%, n=15), and 29.8% (n=28) had not used any SLT products in the past 30 days.

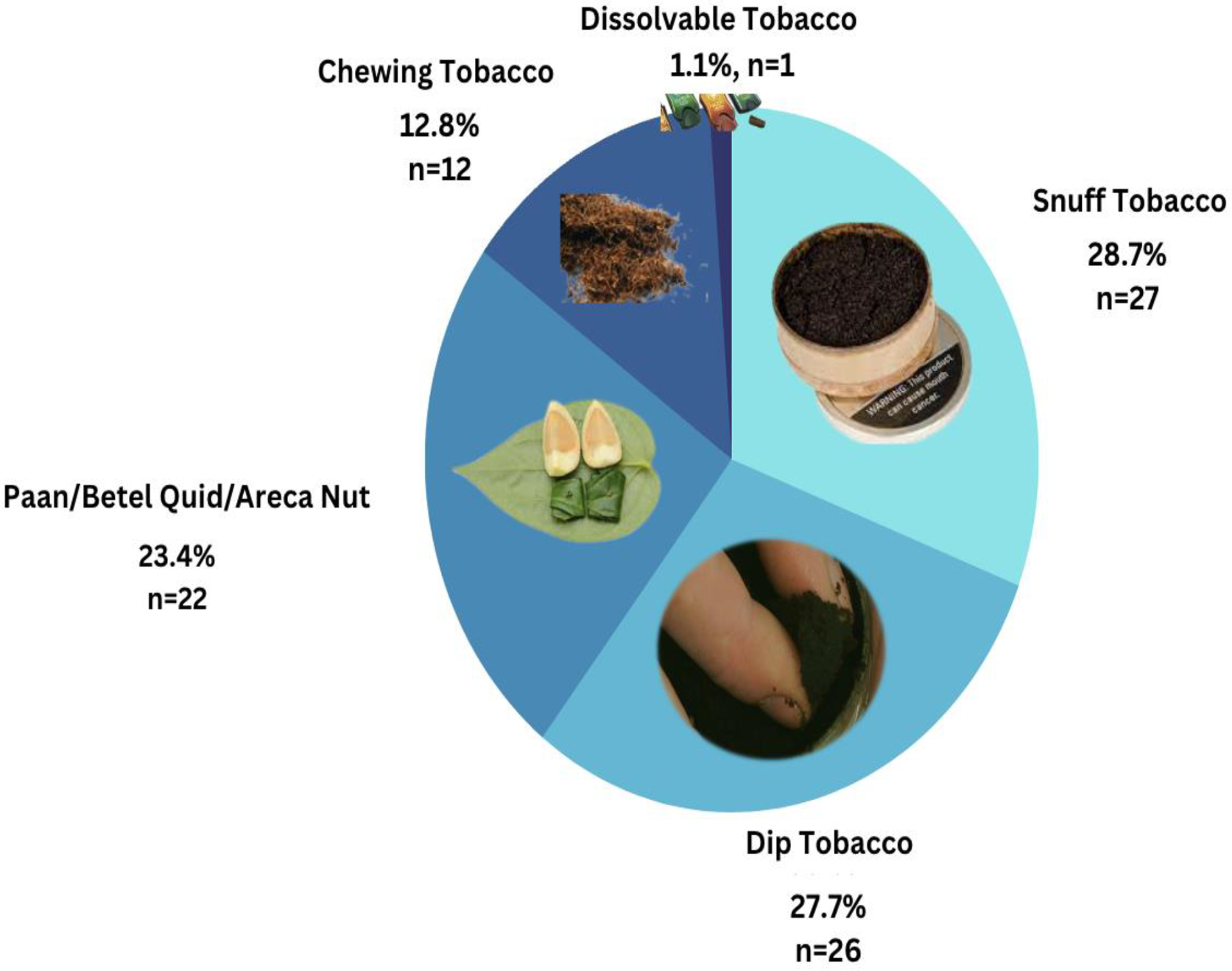

SLT Types of product use and dependence indicated that snuff tobacco (28.7%, n=27), dip tobacco (27.7%, n=26), Paan/betel quid/areca nut (23.4%, n=22), and chewing tobacco (12.8%, n=13), were most frequently forms used (Figure 1). SLT dependence rates were limited to 20.2% (n=19) of participants who reported a strong desire to use SLT within a 60-minute window of waking up. Many participants (76.6%, n=72) started using SLT at 15 years or older, and 3.2% (n=3) reported first-time use at 7 years or younger.

Figure 1:

SLT PRODUCTS

Drivers of SLT use reported by the participants were to 1) to feel good or happy (34%, n=32), 2) use it as recreation (35%, n=33), 3) cope with stress (33%, n=31), 4) taste (18%, n=17), and because of peer pressure (12% n=Table 3). Participants reported that cultural drivers, including family (8.5%, n=8), social purposes (17%, n=16), and overall culture (7.4%, n=7, p=0.001), influenced their decision to use. Meanwhile, 9.6% (n=9) of the participants used SLT for the smell, and 11% (n=10) used it for curiosity (Table 3).

Table 3.

PARTICIPANT REPORTED DRIVERS OF SLT USE

| Characteristic/Drivers | Overall N = 941 |

Asian N = 801 |

Latinos N = 121 |

Non-Latino/White N = 21 |

p-value2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taste | 17 (18%) | 14 (18%) | 2 (17%) | 1 (50%) | 0.5 |

| Smell | 9 (9.6%) | 8 (10%) | 1 (8.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.9 |

| Feel Happy | 32 (34%) | 31 (39%) | 1 (8.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.069 |

| Recreational | 33 (35%) | 30 (38%) | 2 (17%) | 1 (50%) | 0.3 |

| Cultural Drivers | |||||

| Stress | 31 (33%) | 25 (31%) | 4 (33%) | 2 (100%) | 0.12 |

| Curious | 10 (11%) | 7 (8.8%) | 3 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 0.2 |

| Don’t Know | 4 (4.3%) | 3 (3.8%) | 1 (8.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.7 |

| Other including loneliness | 8 (8.5%) | 4 (5.0%) | 4 (33%) | 0 (0%) | 0.004 |

| Other Reason |

n (%)

Pearson’s Chi-squared test

Knowledge, risks, and perception for most participants (86.2%, n=81) was that SLT products were unsafe for their health, caused changes in their mouth (87.2%, n=82)), and caused oral cancer and gum disease (83%, n=78). When comparing SLT to smoking other tobacco use, 60.2% (n=56) perceived it to be less harmful, and a vast majority (76.6%, n=72) understood that the SLT products contained nicotine. The immigrants and refugees of Asian ethnicity were most likely to use SLT products despite an increased awareness (89%, n=71) of their harmful effects and because of cultural norms.

Awareness, availability, and warning statements indicated that participants purchased SLT products within the past 30 days at a convenience store or gas station (48%, n=45) or at a supermarket (22.3%, n=22). 46.8% (n=44) were aware of positive advertising to promote tobacco products at the point of sale, and 43.6% (n=41) did not recall any advertisements or promotions at the point of purchase. More than half (59.6%, n=56) did not notice any health warning statement on SLT packages, and 21% (n=17) reported having seen warning labels but did not think much of them.

SLT cessation practices indicated that 63.8% (n=60) desired to stop using SLT, and 22.3% (n=21) no longer used SLT. 36.2% (n=34) attempted to quit using SLT on their own unsuccessfully, 26.6% (n=25) did not quit at all, and 19% (n=18) stopped using SLT products within the past 12 months of the survey.

Reasons for unsuccessful cessation practices included increased levels of stress, anxiety, loneliness, addiction, and peer pressure as family or friends’ cultural offers. Most who attempted to quit SLT use received support from their family (54%) and friends (32%). Only 12% received an intervention from a healthcare provider, and 1.1% from a health program. 45% percent believed that once someone started using SLT, quitting attempts would be difficult. 50% of non-Latino White (50%) and 51% of Asian participants reported that SLT was hard to quit, relative to the 0% of Latino participants (p<.001).

DISCUSSION

This study found that the most significant SLT use was among South Asians and presented as a cultural norm for predominantly male participants (100%), supported by research, even though some females prefer the SLT form of tobacco, as did the immigrant Venezuelan females for this study.34,35

We found that the prevalence of SLT use by participants was rooted in easy access to the products at nearby ethnic convenience stores, gas stations, or supermarkets catering to their purchasing needs, also reported by research.26 However, participant SLT use escalated due to their desire to feel happy or cope with stress and loneliness as determinants of health as supported by similar research highlighting immigrants’ cultural beliefs about using tobacco products (e.g., aiding digestion or sleep effectiveness).26

Our study found that participants’ dependence on SLT products, culturally acceptable SLT use, and stressors were risk factors inhibiting quitting. The dependent nature of SLT products explained why participants continued using them even though they understood the adverse health effects. Finally, culture and religion as recreation and social interactions influenced the profound use of SLT as supported by research from Pakistan, indicating family, friends, and peer pressure significantly impacted SLT use.28–29,36

The limitations of this study include the self-reported survey and the proportion of Afghan participants as the dominant Asians, even though this composition is scaled to the current resettled population in Texas. Participants included individuals who considered Venezuela (Latinos), Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Myanmar (Asians) as their native lands and resettled in San Antonio. Considering the results may not precisely scale to other cities, the resettled population represents the global community using SLT products. Finally, our study trended frequent forms of Naswar (Afghans), Paan (Burmese), and Betel Quid (Pakistanis) for the current refugee and immigrant population served in San Antonio.

Clinical relevance connects oral to overall health outcomes as tobacco cessation intervention is prioritized by professional associations, including the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American Dental Education Association, where providers are called to intervene.37,38 Healthcare providers should connect their vulnerable patients’ social, cultural, and addictive nature of SLT use with tailored interventions.

Providers should examine their refugee/immigrant patient SLT use by considering their limited access to care due to oral health literacy, financial, transportation, and interpretation challenges upon resettlement in the U.S.39 It was discouraging to realize that practitioners and community intervention programs played an insignificant role for this population’s SLT quit attempts.

Based on this study and supportive current research, future interventions should focus on tailored, culturally sensitive intervention approaches endorsed by the WHO.40 SLT interventions should focus on 1) resettlement-induced stressors and cultural norms combating SLT cessation, 2) the role that underlying trauma, loneliness, stress, and anxiety play in SLT quitting attempts and relapse challenges, 3) assessing the patient’s level of health literacy pre-interventions, and 4) addressing patient barriers to quitting realizing that SLT tobacco cessation protocols are further complicated for refugee patients requiring time and interpretation services for cessation interventions.

CONCLUSION

This effort aims to empower providers to enhance their vulnerable resettled patient SLT cessation practices as participants either did not have access to professional support or were not offered tailored cessations.

Practitioners must aim for more upstream early cessation interventions in contrast to the traditional downstream late-stage cancer detection approach.29 The critical role of friends and family in supporting the use and the quitting process of SLT should not be underestimated. Cultural norms and easy access to SLT products intertwined with literacy and language barriers are trials providers encounter engaging with their newly resettled patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

This study was conducted by the South Texas Oral Health Network (STOHN), supported by the National Center for Advancing Translation Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant UL1TR002645. This study was approved by the University of Texas Health San Antonio Institutional Review Board as an Exempt Study. All participants gave written or verbal consent to participate. The content is solely the authors’ responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. All authors affirm that they have no financial affiliation (employment, direct payment, stock holdings, retainers, consultantships, patent-licensing arrangements, or honoraria) or involvement with any commercial organization with a direct financial interest in the subject or materials discussed in this manuscript, nor have any such arrangements existed in the past three years. The authors deny any conflicts of interest related to this study. We also acknowledge the work of Ms Anusha Kuchibhotla and Ms Kayla Hernandez, interns from the South Texas Oral Health Network. We want to acknowledge Ms Marissa Mexquitic, who was instrumental in this study’s IRB acquisition and all related administrative tasks.

FUNDING STATEMENT:

The study described was supported by the Institute for Integration of Medicine & Science Community Engagement Small Projects Grant, UT Health San Antonio.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Moshtagh R. Farokhi, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, School of Dentistry, San Antonio, Texas; Department of Comprehensive Dentistry, Dental Director, The San Antonio Refugee Health Clinic, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, Texas;.

Jonathan A. Gelfond, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Joe and Teresa Long School of Medicine, Department of Population Health Sciences, San Antonio, Texas.

Saima Karimi Khan, Lucent Dental Group, Private Practice Dentistry, Duncanville, Texas.

Melanie V. Taverna, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, School of Dentistry, Department of Periodontics, Division of Dental Hygiene, San Antonio, Texas.

Fozia A. Ali, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Joe and Teresa Long School of Medicine, Department of Family and Community Medicine, San Antonio, Texas.

Caitlin E. Sangdahl, Practice-Based Research Network Coordinator, Supporting Older Adults through Research Network (SOARNet), South Texas Oral Health Network (STOHN). Institute for Integration of Medicine and Science, Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas

Rahma Mungia, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, School of Dentistry, Department of Periodontics, San Antonio, Texas.

DATA AVAILABILITY:

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the South Texas Oral Health Network (STOHN) website: https://iims.uthscsa.edu/ce/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2023/08/SmokelessTobaccoCEGr_DATA_LABELS_2023-08-02_0932.xlsx

REFERENCES

- 1.Singh PK. Smokeless tobacco use and public health in countries of South-East Asia region. Indian J Cancer. 2014. Dec;51 Suppl 1: S1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Cancer Institute and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smokeless Tobacco and Public Health: A Global Perspective. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. 2014; NIH Publication No. 14–7983. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hecht SS, Hatsukami DK. Smokeless tobacco and cigarette smoking: chemical mechanisms and cancer prevention. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022. Mar;22(3):143–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hatsukami D, Zeller M, Gupta P, et al. Smokeless Tobacco, and Public Health: A Global Perspective. 2014. The National Institute of Health Publication No. 14–7983.

- 5.Cornelius ME, Loretan CG, Wang TW, et al. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults - United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022. Mar 18;71(11):397–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han BH, Wyatt LC, Sherman SE, et al. Prevalence and Correlates of Cultural Smokeless Tobacco Products among South Asian Americans in New York City. J Community Health. 2019. Jun;44(3):479–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu SS, Wang TW, Homa DM, et al. Cigarettes, Smokeless Tobacco, and E-Cigarettes: State-Specific Use Patterns Among U.S. Adults, 2017–2018. Am J Prev Med. 2022. Jun;62(6):930–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chagué F, Guenancia C, Gudjoncik A, et al. Smokeless tobacco, sport and the heart. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2015. Jan;108(1):75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Titova OE, Baron JA, Michaëlsson K, et al. Swedish snuff (snus) and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality: a prospective cohort study of middle-aged and older individuals. BMC Med. 2021:19, 111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clarke E, Thompson K, Weaver S, et al. Snus: a compelling harm reduction alternative to cigarettes. Harm Reduct J. 2019; 16: 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patidar KA, Parwani R, Wanjari SP, et al. Various terminologies associated with areca nut and tobacco chewing: A review. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2015. Jan-Apr;19(1):69–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chadda R, Sengupta S. Tobacco use by Indian adolescents. Tob Induc Dis. 2002. Jun 15;1(2):111–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez-Rivas JP, Santiago RJG, Mechanick JI, et al. Chimo, a Smokeless Tobacco Preparation, is Associated with a Lower Frequency of Hypertension in Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Cardiovas. Sci 2017;30(5): 373–379. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakhaei Moghaddam T, Mobaraki F, Darvish Moghaddam MR, et al. A review on the addictive materials paan masala (Paan Parag) and Nass (Naswar). SciMedicine Journal. 2019; 1(2): p. 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nadar MS, Hasan AM, Alsaleh M. The negative impact of chronic tobacco smoking on adult neuropsychological function: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21, 1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richter P, Hodge K, Stanfill S, et al. Surveillance of moist snuff: total nicotine, moisture, pH, un-ionized nicotine, and tobacco-specific nitrosamines. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008. Nov;10(11):1645–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muthukrishnan A, Warnakulasuriya S. Oral health consequences of smokeless tobacco use. Indian J Med Res. 2018. Jul;148(1):35–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan SZ, Farooq A, Masood M, et al. Smokeless tobacco use and risk of oral cavity cancer. Turk J Med Sci. 2020. Apr 9;50(1):291–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Factsheet: Smokeless Tobacco: Health Effects. December 2016. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/smokeless/health_effects/index.htm.

- 20.Kamath KP, Mishra S, Anand PS. Smokeless tobacco use as a risk factor for periodontal disease. Front Public Health. 2014; Oct 20;2:195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The United Nations Commission of Refugees. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/what-refugee.

- 22.Dreher A, Langlotz S, Matzat J, Parsons C. Immigration, Political Ideologies and the Polarization of American Politics. CESifo WP 8789. Munich: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ullah MZ, Lim JN, Ha MA, et al. Smokeless tobacco use: pattern of use, knowledge, and perceptions among rural Bangladeshi adolescents. PeerJ. 2018. Aug 21;6:e5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rollins K, Lewis C, Edward Smith T, et al. Development of a Culturally Appropriate Smokeless Tobacco Cessation Program for American Indians. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2018. Spring;11(1):45–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Auluck A, Hislop G, Poh C, et al. Areca nut and betel quid chewing among South Asian immigrants to Western countries and its implications for oral cancer screening. Rural Remote Health. 2009. Apr-Jun;9(2):1118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blank M, Deshpande L, Balster RL. Availability and characteristics of betel products in the U.S. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2008. Sep;40(3):309–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moafa I, Crutzen R, van den Borne B, et al. Towards a better understanding of the psychosocial determinants associated with adults’ use of smokeless tobacco in the Jazan Region of Saudi Arabia: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2022. Apr 13;22(1):732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamen-Kaye D Chimó: an unusual form of tobacco in Venezuela. Bot Mus Lealf Harv Univ. 1971. Jan 20; 23:1–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farhadmollashahi L Sociocultural reasons for smokeless tobacco use behavior. Int J High Risk Behav Addict. 2014; Jun 1;3(2): e20002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009. Apr;42(2):377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shohet L, Renaud L. Critical analysis on best practices in health literacy. Can J Public Health. 2006. May-Jun;97 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S10–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bandura A Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychol. Health 1998;13(4):623–649. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pribadi ET, Devy SR. Application of the Health Belief Model on the intention to stop smoking behavior among young adult women. J Public Health Res. 2020. Jul 2;9(2):1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hussain A, Zaheer S, and Shafique K. Individual, social and environmental determinants of smokeless tobacco and betel quid use amongst adolescents of Karachi: a school-based cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2017; 17(1): 913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pampel F, Khlat M, Bricard D, et al. Smoking Among Immigrant Groups in the United States: Prevalence, Education Gradients, and Male-to-Female Ratios. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020. Apr 17;22(4):532–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mukherjea A, Morgan PA, Snowden LR, et al. Social and cultural influences on tobacco-related health disparities among South Asians in the USA. Tob Control. 2012. Jul;21(4):422–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.American Association of Family Physicians. Ask and Act Tobacco Cessation Program. Available from: https://www.aafp.org/family-physician/patient-care/care-resources/tobacco-and-nicotine/ask-act.html.

- 38.American Dental Association Position on Tobacco Cessation. Available from: https://www.ada.org/about/governance/current-policies#tobacco.

- 39.Farokhi MR, Muck A, Lozano-Pineda J, et al. Using Interprofessional Education to Promote Oral Health Literacy in a Faculty-Student Collaborative Practice. J Dent Educ. 2018. Oct;82(10):1091–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Health Organization (WHO) monograph on tobacco cessation and oral health integration. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-monograph-on-tobacco-cessation-and-oral-health-integration. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the South Texas Oral Health Network (STOHN) website: https://iims.uthscsa.edu/ce/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2023/08/SmokelessTobaccoCEGr_DATA_LABELS_2023-08-02_0932.xlsx