To the Editor,

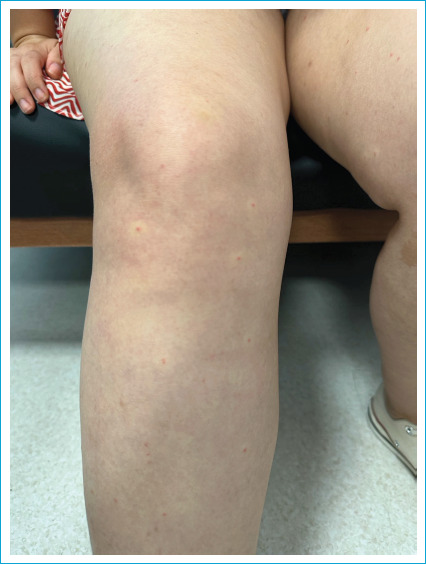

A 25-year-old woman presented with a six-week history of skin lesions. Initially, numerous asymptomatic vascular lesions appeared on her upper extremities. Then, lower extremities were involved as well. Lesions had a fluctuating course with newly appearing and resolving lesions. Her medical and family history was unremarkable except for an acute gastroenteritis that occurred 2 weeks before onset of the symptoms. Dermatological examination revealed multiple, symmetrically distributed 2-4 mm blanchable erythematous, hemangioma-like papules with a pale halo located on the extremities (Fig. 1). There was no mucosal, hair or nail involvement. Lesions blanched completely at diascopy and refilled from center on release of pressure. Polarized dermoscopy showed multiple, red, pin-point dots within erythematous structureless areas. Purpuric globules and dots were absent ruling out erythrocyte extravasation and vasculitis.

Figure 1.

Multiple, symmetrically distributed 2-4 mm blanchable erythematous, hemangioma like papules with a pale halo.

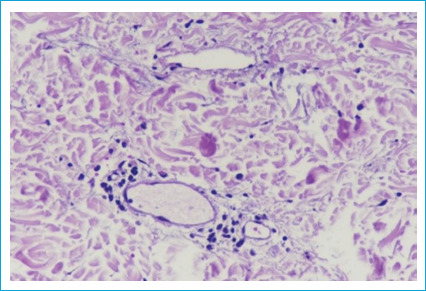

Routine laboratory investigations were within normal limits. ANA and ANCA were negative. Viral serological tests for HIV, HBV, HCV, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV) were all negative. A 4 mm punch biopsy was obtained for histopathological examination and the hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed dilated blood vessel with plump endothelial cells surrounded by mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the mid and deep dermis (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Dilated blood vessel with plump endothelial cells surrounded by mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the mid and deep dermis.

Considering the clinical characteristics of the lesions (acute onset, asymptomatic nature, hemangioma-like lesions but without lacunas, and spontaneous resolution), history of a possibly triggering viral infection (gastroenteritis), laboratory and histopathological features, the diagnosis of “eruptive pseudoangiomatosis (EP)” was made. A topical corticosteroid cream containing methylprednisolone aceponate was prescribed and all the lesions resolved within 10 days without any residual scarring or relapse.

EP is a rare exanthem characterized by blanchable, hemangioma-like lesions with perilesional halo that resolve spontaneously. It was first described in 1969 by Cherry et al. in four children after echovirus infection and it was first named in 1993 by Prose et al.[1,2] Although it was initially described in children and considered a childhood rash for a long time, Navarro et al.[3] reported the first adult case with evidence of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection in 2000. Since then adult cases have also been reported in the literature.

The exact pathogenesis of this entity is still not fully elucidated. Although viral etiologies are predominantly considered in pathogenesis, paraviral etiology has also been suggested. Typical dermatological findings of EP occurring after a prodromal period with evidence of viral infection such as echovirus, CMV, EBV, parvovirus B19, adenovirus and SARS-CoV-2 have been reported in the literature.[1-6] However, it has been shown that it may be associated with paraviral etiologies such as insect bites, vaccination (COVID-19 immunization) and immunosuppression.[7-11] The characteristics of exposed skin lesions after insect bites, especially mosquito bites, support that insect bites may induce EP.[7,8] In adult, and elderly patients, a stronger relationship has been demonstrated between EP and immunosuppression. González Saldana et al.[11] reported two cases of EP in an HIV-positive patient in the AIDS stage and in another patient with non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Despite diverse underlying etiologies, the clinical features are similar in the affected patients. EP is characterized by 2-4 mm, blanchable, erythematous, hemangioma-like papules with a pale halo that are usually distributed symmetrically in visible areas such as extremities and face.[12] The lesions are usually asymptomatic but 22% of patients can also describe pruritus.[13] Clinical features may vary between children and adults. The onset of lesions occurs following a prodromal period in pediatric patients, whereas prodromal symptoms are usually absent in the adult patients. In addition, the eruption lasted longer in adults than in children.[11] The rash resolves spontaneously without residual scarring in 2-18 days in children and more than one month in adults.[11,14] Histopathological examination shows dilated blood vessels with plump endothelial cells and mild-to-moderate perivascular lymphohistiocytic cell infiltration. Epidermis is usually normal and it’s noteworthy that there is no vascular proliferation or leukocytoclasia, fibrinoid necrosis that support vasculitis.[12]

Viral exanthem, insect bite, ictus reaction, papular urticaria, hemangioma, leukocytoclastic vasculitis and punctate telangiectasia were considered in the differential diagnosis in our patient. Differential diagnosis of EP from “hemangioma-like lesions” includes leukocytoclastic vasculitis and punctate telangiectasia. Dermatological manifestations of leukocytoclastic vasculitis were petechiae and palpable purpura that were not blanchable. Also, histopathology reveals leukocytoclasia, fibrinoid necrosis in the vessel wall and/or extravasated erythrocytes.[15] Hemangioma and punctate telangiectasia are benign vascular lesions that are blanchable on pressure, but they do not resolve.[16] Based on clinical features and dermatological examination, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, hemangioma and punctate telangiectasia were ruled out. Differential diagnosis of EP from “erythematous lesions” includes insect bites, ictus reaction and papular urticaria. Insect bite is a pruritic erythematous papule after being bitten by various agents. Whereas ictus reaction is a rare reaction caused by insect bites. It is pruritic, erythematous papular reaction with a perilesional pale halo. Papular urticaria is an itchy rash characterized by recurrent lesions that disappear within 24 hours resulting from hypersensitivity reaction to bites of various types of insects and arthropods.[17] Histopathological examination shows typically a mixed infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes and especially eosinophils. The category of erythematous lesions can also be ruled out by examining the clinical and histopathological features.

In conclusion, in dermatology practice, clinicians do not frequently encounter spontaneously resolving vascular lesions. We present this rare case of EP in order to increase awareness of clinicians about this rare entity and help them to make an accurate differential diagnosis for good clinical practice.

Disclosures

Patient Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Conflict of Interest

All the other authors declared they did not have anything to disclose regarding conflict of interest with respect to this manuscript.

Financial Support (Funder's Name)

The authors declare that there were no relationships that provided financial or editorial support for the study which may in potential cause competing interest for the submission.

Use of AI for Writing Assistance

None declared.

Authorship Contributions

Concept – P.O.C., S.A., I.K.A., A.A.C., B.O.K.; Design – P.O.C., S.A., I.K.A.; Supervision – P.O.C., S.A., B.O.K.; Data collection &/or processing – P.O.C., S.A., A.A.C., D.T.; Analysis and/or interpretation – P.O.C., S.A., B.O.K., D.T.; Literature search – P.O.C., S.A.; Writing – P.O.C., S.A.; Critical review – P.O.C., S.A., I.K.A., A.A.C., D.T., B.O.K.

References

- 1.Cherry JD, Bobinski JE, Horvath FL, Comerci GD. Acute hemangioma-like lesions associated with ECHO viral infections. Pediatrics. 1969;44:498–502. doi: 10.1542/peds.44.4.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prose NS, Tope W, Miller SE, Kamino H. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis: a unique childhood exanthem? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:857–9. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70255-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Navarro V, Molina I, Montesinos E, Calduch L, Jordá E. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis in an adult. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:237–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maqsood F, Vassallo C, Derlino F, Croci GA, Ciolfi C, Brazzelli V. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis: clinicopathological report of 20 adult cases and a possible novel association with parvovirus B19. Acta Derm Venereol. 2021;101:adv00398. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chuh A, Panzer R, Rosenthal AC, Proksch E, Kempf W, Zawar V, et al. Annular eruptive pseudoangiomatosis and adenovirus infection: a novel clinical variant of paraviral exanthems and a novel virus association. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:354–7. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alonzo Caldarelli A, Barba P, Hurtado M. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis and SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infection. Int J Dermatol. 2021;60:1028–9. doi: 10.1111/ijd.15598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neri I, Assirelli V, Chessa MA, Gurioli C, Filippi F, Virdi A. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis induced by mosquito bites in an infant. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2019;10:e2020024. doi: 10.5826/dpc.1001a24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ban M, Ichiki Y, Kitajima Y. An outbreak of eruptive pseudoangiomatosis-like lesions due to mosquito bites: erythema punctatum Higuchi. Dermatology. 2004;208:356–9. doi: 10.1159/000077850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Restano L, Cavalli R, Colonna C, Cambiaghi S, Alessi E, Caputo R. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis caused by an insect bite. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:174–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohta A, Sharma MK, Ghiya BC, Mehta RD. Clinical, histopathological, and dermatoscopic characterization of eruptive pseudoangioma developing after COVID-19 vaccination-A case-series. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:1799–801. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.González Saldaña S, Mendez Flores RG, López Gutiérrez AF, Salas Núñez LN, Hermosillo Loya AK, Ramírez Padilla M, et al. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis in adults with immune system disorders: a report of two cases. Dermatol Reports. 2020;12:8836. doi: 10.4081/dr.2020.8836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chopra D, Sharma A, Kaur S, Singh R. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis-cherry angiomas with perilesional halo. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84:424–30. doi: 10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_483_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim JE, Kim BJ, Park HJ, Park YM, Park CJ, Cho SH, et al. Clinicopathologic review of eruptive pseudoangiomatosis in Korean adults: report of 32 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:41–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kushwaha RK, Mohta A, Jain SK. A case of eruptive pseudoangiomatosis: clinical, histopathological, and dermoscopic findings. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2020;11:672–3. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_407_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goeser MR, Laniosz V, Wetter DA. A practical approach to the diagnosis, evaluation, and management of cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:299–306. doi: 10.1007/s40257-014-0076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takcı Z, Tekin Ö Tezer A. Two cases of hereditary benign telangiectasia in Turkey: sporadic occurrence with punctate telangiectasias surrounded by anemic halos. Turk J Pediatr. 2015;57:94–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jordaan HF, Schneider JW. Papular urticaria: a histopathologic study of 30 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:119–26. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199704000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]