Abstract

Mutations in the IN domain of retroviral DNA may affect multiple steps of the virus life cycle, suggesting that the IN protein may have other functions in addition to its integration function. We previously reported that the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 IN protein is required for efficient viral DNA synthesis and that this function requires specific interaction with other viral components but not enzyme (integration) activity. In this report, we characterized the structure and function of the Moloney murine leukemia virus (MLV) IN protein in viral DNA synthesis. Using an MLV vector containing green fluorescent protein as a sensitive reporter for virus infection, we found that mutations in either the catalytic triad (D184A) or the HHCC motif (H61A) reduced infectivity by approximately 1,000-fold. Mutations that deleted the entire IN (ΔIN) or 34 C-terminal amino acid residues (Δ34) were more severely defective, with infectivity levels consistently reduced by 10,000-fold. Immunoblot analysis indicated that these mutants were similar to wild-type MLV with respect to virion production and proteolytic processing of the Gag and Pol precursor proteins. Using semiquantitative PCR to analyze viral cDNA synthesis in infected cells, we found the Δ34 and ΔIN mutants to be markedly impaired while the D184A and H61A mutants synthesized cDNA at levels similar to the wild type. The DNA synthesis defect was rescued by complementing the Δ34 and ΔIN mutants in trans with either wild-type IN or the D184A mutant IN, provided as a Gag-IN fusion protein. However, the DNA synthesis defect of ΔIN mutant virions could not be complemented with the Δ34 IN mutant. Taken together, these analyses strongly suggested that the MLV IN protein itself is required for efficient viral DNA synthesis and that this function may be conserved among other retroviruses.

Retrovirus assembly involves precursor polyproteins encoded by the gag, pol, and env genes. The Gag polyprotein plays a central role in virion assembly and is itself sufficient to produce noninfectious virus-like particles. The Pol polyprotein is translated as a Gag-Pol fusion protein that is produced by either a ribosomal frameshift or a read-through of the termination codon. In several retrovirus subfamilies, including Moloney murine leukemia virus (MLV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Pol consists of protease (PR), reverse transcriptase (RT), and integrase (IN). Thus, assembly of the viral enzymes occurs in the context of a large Gag-Pol precursor polyprotein. During assembly of MLV and HIV virions, the dimerization of PR induces proteolysis and subsequently cleavage of the Gag and Gag-Pol precursors into their mature protein products. This results in a rearrangement of the cleaved Gag and Pol polypeptides within the virion, which leads to condensation of the virus core, a process that is essential for formation of infectious virions (for reviews, see references 27 and 29).

The retroviral IN protein plays a central role in the formation of proviral DNA. After the virus enters a target cell and reverse transcription of the RNA genome is completed, IN catalyzes integration of the nascent viral cDNA into the host cell genome. From extensive in vitro analysis, significant progress has been made in understanding the structure of the IN protein, the contribution of IN subdomains to enzyme activity, and the mechanism of the integration reaction. Using recombinant IN and oligonucleotides that represent the viral DNA ends, the in vitro integration reaction proceeds in two steps: IN removes two nucleotides from the 3′ terminus of the linear DNA molecule (3′-end processing), which is then joined to the target DNA (strand transfer). Through amino acid sequence alignment and in vitro activity studies of wild-type and mutant IN, residues have been identified that are conserved among retroviral IN proteins, including those comprising a zinc finger-like motif (HHCC) located in the N terminus and a D,D(35)E motif required for polynucleotide transfer. Mutations in the D,D(35)E catalytic triad abolish strand transfer activity in vitro, indicating that this motif represents the catalytic site of IN. Mutations in the HHCC and D,D(35)E motifs of HIV type 1 (HIV-1) IN disrupt both 3′-end processing and strand transfer in vitro. The carboxyl terminus of IN is least conserved and possesses nonspecific DNA binding properties (for a review, see reference 4). The C terminus of the HIV-1 IN protein has been associated with nuclear import of the preintegration complex (13).

In vivo analyses of HIV-1 IN structure and function have suggested that the IN protein may play important nonenzymatic roles during the early stages of the virus life cycle (10). However, these in vivo studies with infectious virus (proviral DNA) have been complicated since mutations in IN affect the Gag-Pol precursor protein and often cause defects during the late stages of the virus life cycle. Numerous studies have reported IN mutations that cause defects in virion assembly, production, maturation, protein composition, or nuclear import of the preintegration complex (2, 3, 5, 6, 11, 22, 26). Some HIV-1 IN mutations impair viral DNA synthesis without an apparent effect on late-stage events (11, 15, 19). Similarly, studies of the IN of Ty3, a retrovirus-like element of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, identified nonconserved IN mutations that reduced the level of replicated DNA, despite normal levels of exogenous RT activity and capsid maturation (21).

To specifically analyze the function of the mature IN protein during early stages of the virus life cycle, we developed a trans-complementation approach. This enables the packaging of functional Pol proteins (RT and IN) into virions by their expression in trans, independently of the Gag-Pol precursor (17, 18, 31, 32). By expressing IN as a fusion partner of virus protein R (Vpr), fully functional IN can be incorporated into wild-type or IN mutant virions in trans (17, 32). Complementation studies indicated that the trans-IN protein rescued the defects in DNA synthesis caused by certain HIV-1 IN mutations, including those in the highly conserved HHCC motif (31). Complementation of this defect did not require the trans-IN protein to be enzymatically (integration) active, confirming that the IN protein itself augments DNA synthesis in vivo.

Several studies have analyzed MLV IN function in vivo by introducing mutations into the IN coding region of full-length proviral DNA. Nearly all of these mutations caused a severe loss of virus infectivity. Similarly to HIV-1, some mutations were also found to impair late-stage events of the virus life cycle (virion production or proteolytic processing of Gag and Pol), while others appeared to affect only early events (23–25). Southern blot analysis of unintegrated cDNA did not reveal a notable impairment in viral DNA synthesis (8, 9, 24, 25). These findings suggested that IN mutant viruses exhibited reduced infectivity as a result of a defect in the integration of proviral DNA. Since Southern blot analysis of unintegrated DNA measures only a portion of the total viral DNA synthesized, we reexamined the effects of IN mutations on MLV DNA synthesis in infected cells using sensitive, semiquantitative PCR-based methods. Our results indicate that complete deletion or C-terminal truncation of IN results in a reproducible reduction in viral cDNA synthesis. To rule out the possibility that this phenotype was due to negative effects of the mutations on a late-stage event of the virus life cycle, we used MLV Gag-IN fusion proteins to package IN into MLV virions in trans. This analysis demonstrated that trans-IN protein (derived from Gag-IN) rescued defects in both viral DNA synthesis and infectivity, confirming that the mature MLV IN protein itself augments reverse transcription in infected cells. This finding is consistent with those for HIV-1 and suggests a role of the IN protein in viral DNA synthesis that may be conserved among all retroviruses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and antibodies.

293T and HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U of penicillin, and 0.1 mg of streptomycin/ml. Rabbit polyclonal antisera against the MLV Pol, p30Gag, and RT proteins were generous gifts from Monica Roth, Alan Rein, and Stephen Goff, respectively.

Expression plasmids.

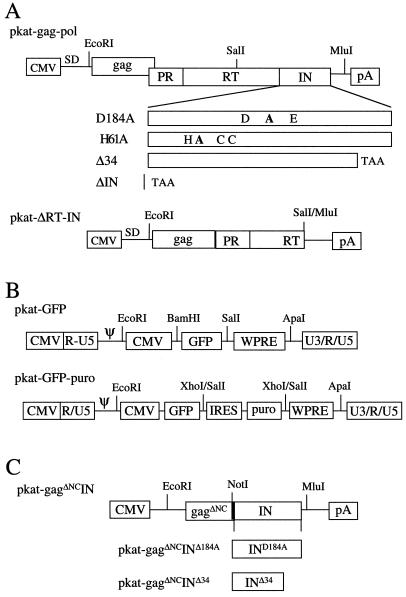

Our analysis of IN was performed using the MLV pkat vector system described previously (12). IN mutations were introduced into the pkat-gag-pol packaging plasmid. To facilitate cloning of the various IN mutants, pkat-gag-pol was first modified by introducing a unique MluI site at the end of the IN coding region (Fig. 1A). To abolish the catalytic activity of IN, the pkat-IND184A plasmid was constructed. Partially overlapping 5′ SalI-ScaI and 3′ ScaI-MluI DNA fragments were PCR amplified from pkat-gag-pol. The internal sense primer replaced alanine with an aspartic acid residue at position 184 (D184A). The ScaI site was introduced by design of the internal primers and did not change the amino acid sequence. The pkat-INH61A plasmid was constructed to disrupt the zinc finger domain of IN. Partially overlapping 5′ SalI-XhoI and 3′ XhoI-MluI DNA fragments were PCR amplified from pkat-gag-pol. The internal antisense primer replaced alanine with a histidine residue at position 61 (H61A). The XhoI site was introduced via primer design without changing the amino acid sequence. The pkat-INΔ34 plasmid deleted 34 amino acids from the carboxyl terminus of IN. It was constructed by ligating an SalI-MluI DNA fragment into pkat-gag-pol. The 3′ mutagenic primer deleted 102 bp of IN sequence and introduced a TAA translational stop codon at amino acid position 374. The pkat-ΔIN plasmid deleted the entire IN protein. It was constructed by ligating a PCR-amplified, RT-containing SalI-MluI DNA fragment into SalI-MluI-cut pkat-gag-pol. The 3′ antisense primer introduced an MluI site and included a TAA translational stop codon after the last codon of RT. The pkat-ΔRT-IN plasmid deleted the 3′ end of Pol, including most of RT (301 residues) and all of the IN coding region. It was constructed by cutting pkat-gag-pol with SalI and MluI, filling in with Klenow enzyme, and then religating with T4 DNA ligase.

FIG. 1.

DNA construction of MLV packaging, vector, and trans-IN expression plasmids. (A) Packaging constructs. The IN coding region of the wild-type pkat-gag-pol plasmid was mutated as illustrated, generating the D184A, H61A, Δ34, and ΔIN mutants. The pkat-ΔRT-IN mutation deletes all of IN and the 3′ half of RT. SD, splice donor sequence. (B) Gene transfer (vector) plasmids. The effects of IN mutations on infectivity and integration were analyzed using the pkat-GFP and pkat-GFP-puro gene transfer vectors. In both vectors, the GFP reporter is under the control of the CMV promoter. Using an IRES, the pkat-GFP-puro vector enables GFP and puromycin to be expressed from the same mRNA. (C) trans-IN expression plasmids. The pkat-gagΔNCIN, pkat-gagΔNCINΔ34, and pkat-gagΔNCIND184A plasmids fused gag (minus the NC domain) in frame with wild-type and mutant (Δ34 and D184A) IN. At the gag-IN junction, 42 bp of RT sequence was included (darkened bar) to preserve the natural protease cleavage site at the N terminus of IN.

The pkat-GFP vector was constructed by ligating an EcoRI-ApaI cytomegalovirus (CMV)-green fluorescent protein (GFP)-woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element (WPRE)-containing DNA fragment PCR amplified from pPCW-eGFP (7) into the rkat vector (12). The WPRE (34) was included to enhance gene expression. The pkat-GFP-puro vector was constructed by inserting an XhoI-XhoI internal ribosome entry site (IRES)-puromycin-containing DNA fragment, PCR amplified from the pIRES-puro plasmid (Clontech Inc.), into SalI-cut pkat-GFP (Fig. 1B).

The pkat-gagΔNCIN plasmid was used to express and package IN protein in trans to pkat-gag-pol. It was constructed by coligating a PCR-amplified EcoRI-NotI 5′ gag-containing DNA fragment and a NotI-MluI IN-containing DNA fragment into EcoRI-MluI-cut pkat-gag-pol. The NotI site was introduced with the internal primer pairs and did not change the amino acid sequence. This placed the IN coding region immediately downstream of the capsid (CA) domain of Gag (Fig. 1C). To preserve the N-terminal protease cleavage site of IN, 42 bp of 3′ RT sequence was included at the CA-IN junction. The pkat-gagΔNCINΔ34 plasmid was constructed by cloning an NotI-MluI IN-containing DNA fragment of pkat-gag-pol into pkat-gagΔNCIN. The 3′ antisense primer introduced the MluI site and a TAA translational codon at amino acid position 374 of IN. The pkat-gagΔNCINΔ184A plasmid was constructed by cloning an NotI-MluI IND184A-containing DNA fragment PCR amplified from pkat-IND184A into NotI-MluI-cut pkat-gagΔNCIN. The sequence of all the plasmids was confirmed by nucleotide sequence analysis. The pkat-env plasmid (pkatamenvATG) expresses the amphotropic MLV envelope and was described earlier (12).

Virus infectivity and integration assays.

Culture supernatants from 293T cells were collected 72 h after transfection, clarified by low-speed centrifugation (1,000 × g, 10 min), and filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size sterile filters. HeLa cells grown in 24-well plates were infected with serial fivefold dilutions of supernatant in DMEM containing 1% FBS and 10 μg of DEAE-dextran/ml at 37°C for 4 h. The medium was then replaced with fresh DMEM containing 10% FBS. Two days later, GFP-positive (green) cell colonies were counted using a fluorescence microscope. Each GFP-positive colony was counted as 1 virus infectious unit. For the analysis of proviral integration, DMEM containing puromycin (4 μg/ml) was added to the infected HeLa cells and the number of resistant, GFP-positive cell colonies was counted after 14 days of selection.

Semiquantitative analysis of viral DNA synthesis.

The PCR technique used to monitor the synthesis of viral DNA in infected cells was similar to that described earlier (31). Briefly, transfection-derived virus was filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size filters and incubated with DNase I (4 μg/ml; Worthington Inc.) at 37°C for 1 h to minimize DNA contamination. One milliliter of each virus stock (normalized for RT activity or the density of capsid protein [p30] on Western blotting) was used to infect 1 million HeLa cells. The cells were washed twice with DMEM by low-speed centrifugation after 4 h and lysed after 18 h. Total DNA was extracted by organic methods, resuspended in 100 μl of distilled water, and treated with the DpnI restriction endonuclease to digest bacterially derived plasmid DNA. Four hundred nanograms of each DNA extract was subjected to 25 rounds of PCR amplification using primers designed to detect late (R-gag [sense nucleotides 1 to 22, 5′-GCGCCAGTCCTCCGATTGACTG-3′, and antisense nucleotides 626 to 602, 5′-GCCCATATTCTCAGACAAATACAGAAA-3′]) products of reverse transcription. PCR products were separated on 1.5% agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide. The relative amount of amplified DNA was determined by comparison to known standards. As standards, fivefold serial dilutions of vector DNA ranging from 50 to 31,250 copies were analyzed in parallel.

RESULTS

Analysis of IN mutant virions.

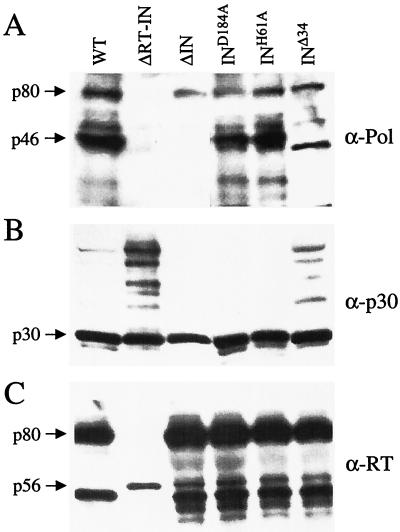

Our analysis of MLV IN protein function was performed in infected cells using the pkat MLV vector system described previously (12). Mutations were introduced into the IN sequence of the pkat-gag-pol packaging plasmid. These included mutations that disrupted the catalytic triad (D184A) or the N-terminal HHCC motif (H61A) and those that deleted either a portion of the C terminus (Δ34) or the entire protein (ΔIN) (Fig. 1A). Virions were generated by individually transfecting 293T cell cultures with the mutant packaging constructs, the pkat-GFP gene transfer vector, and the pkat-env plasmid. Wild-type virions were produced using the pkat-gag-pol packaging construct as a control. Virions collected from the culture supernatants by ultracentrifugation were analyzed by immunoblotting. The mature form (46 kDa) of the D184A and H61A mutant IN proteins was detected using anti-Pol antiserum (Fig. 2A). The Δ34 mutant was detected migrating with a lower molecular weight, consistent with the 34-amino-acid truncation. No IN protein was detected for the ΔIN mutant. Virions were also analyzed using anti-Gag antibody specific for the MLV p30 capsid protein. The D184A and H61A mutants were identical to the wild type with respect to the amount and proteolytic processing of the p65 Gag precursor protein. In the case of Δ34 mutant virions, slightly elevated amounts of incompletely processed Gag were detected (Fig. 2B). The ΔRT-IN mutant (included as a control) also exhibited increased levels of unprocessed and incompletely processed Gag protein. In comparing the signal intensities of p30, there did not appear to be a significant change in virion production among the different IN mutants. In using anti-RT antiserum to probe replica blots, no differences were detected between wild-type and IN mutant virions in either the amount or processing of the 80-kDa RT protein (Fig. 2C). A truncated RT protein (∼56 kDa) was detected in the ΔRT-IN mutant, consistent with the 301-amino-acid residue deletion. Culture supernatants were also analyzed for RT activity, and except for the ΔRT-IN mutant, all of the IN mutants exhibited levels similar to that of wild type (Table 1). Taken together, these results demonstrated that there was not a severe defect in the assembly, release, and maturation of the IN mutant virions.

FIG. 2.

Immunoblot analysis of IN mutant virions. Cultures of 293T cells were separately transfected with 3 μg each of the different mutant packaging constructs plus 3 μg of the pkat-GFP gene transfer vector and 1 μg of the pkat-env plasmid. Six milliliters of each culture supernatant was collected after 72 h, and virions were pelleted by ultracentrifugation (125,000 × g for 2 h) using a Beckman SW-41 rotor. Pellets were solubilized in lysis buffer and analyzed by immunoblotting as described previously (33). Replica blots were probed separately with anti-Pol (A), anti-CA (B), and anti-RT (C) antibodies. WT, wild type.

TABLE 1.

Analysis of IN mutant virionsa

| Virus | cpm/ml | IU/ml | % of wt |

|---|---|---|---|

| wt | 8.1 × 107 | 7.5 × 107 | 100 |

| ΔRT-IN | 2.5 × 102 | 0 | 0 |

| ΔIN | 6.5 × 107 | 4.5 × 103 | 0.006 |

| D184A | 7.4 × 107 | 5.0 × 104 | 0.066 |

| H61A | 6.5 × 107 | 3.5 × 104 | 0.046 |

| Δ34 | 8.3 × 107 | 5.5 × 103 | 0.007 |

Viral stocks were derived by transfecting 293T cells with 3 μg of each mutant pkat-gag-pol packaging construct together with 3 μg of the pkat-GFP vector and 1 μg of the pkat-env plasmid. Supernatants were collected after 72 h, filtered, and analyzed for RT activity (cpm per milliliter) and infectivity on cultures of HeLa cells. GFP-positive cell colonies (infectious units [IU]) per milliliter of culture supernatant were enumerated 2 days after infection. The numbers are representative of two independent experiments. wt, wild type.

Virion infectivity was analyzed on monolayer cultures of HeLa cells by quantifying the number of GFP-positive cell colonies produced after 2 days. The titer of the wild type was 7.5 × 107 infectious particles per ml. Inclusion of the WPRE sequence (Fig. 1B) in the pkat-GFP gene transfer vector led to a 5- to 10-fold increase in vector titer (data not shown). As expected, the IN mutants were markedly less infectious: their titers were reduced 1,000- to 10,000-fold compared with wild type (Table 1). Nevertheless, the IN mutants, including ΔIN, reproducibly generated a substantial number of GFP-positive colonies above that of background (approximately 5,000). The ΔRT-IN mutant failed to produce any GFP-positive cells, helping to rule out the possibility of pseudotransduction (GFP carryover). These results clearly demonstrated a defect in the infectivity of the IN mutants. In addition, they suggested that unintegrated DNA may have served as a template for GFP expression.

To confirm whether GFP expression of the IN mutants was mediated by unintegrated cDNA, the pkat-GFP transfer vector was modified by inserting an IRES and a puromycin-resistant gene downstream of GFP, generating pkat-GFP-puro (Fig. 1B). Viral stocks were generated by DNA transfection, normalized by RT activity, and used to infect HeLa cells. Two days after infection, the number of GFP-positive colonies was counted and then the cultures were placed on medium containing puromycin. The number of GFP-positive resistant cell colonies was counted after 14 days of selection (Table 2). The number of resistant, GFP-positive colonies produced by the wild type was 70% of that of GFP colonies prior to selection. For each of the IN mutants, only 0.4 to 0.04% of the GFP-positive colonies detected on day 2 survived puromycin selection, confirming a severe defect in integration. These results strongly suggested that unintegrated cDNA derived from the gene transfer vector served as a template for GFP expression for a short time following infection. This findings also provided an additional means to help distinguish between IN mutations that affect integration and those that affect DNA synthesis.

TABLE 2.

GFP expression from unintegrated DNAa

| Virus | No. of GFP+ cell colonies/ml

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Preselection | Postselection | |

| wt | 5.7 × 107 | 4 × 107 (70) |

| ΔRT-IN | 0 | 0 |

| ΔIN | 5.3 × 103 | 10 (0.19) |

| D184A | 8.5 × 104 | 30 (0.04) |

| H61A | 4.5 × 104 | 30 (0.06) |

| Δ34 | 5.0 × 103 | 20 (0.40) |

Viral stocks were prepared and normalized as described for Table 1, except that the pkat-GFP-puro vector was used in place of pkat-GFP. Supernatants were collected after 72 h, filtered, and used to infect HeLa cells. Two days later, the number of GFP-positive cell colonies was determined, and then 1 μg of puromycin per ml was added to the medium. The number of resistant, GFP-positive cell colonies (100% GFP positive) was determined 14 days later. Numbers in parentheses represent the number of GFP-positive colonies after puromycin selection relative to that prior to selection, which was arbitrarily set at 100. The numbers are representative of two independent experiments. wt, wild type.

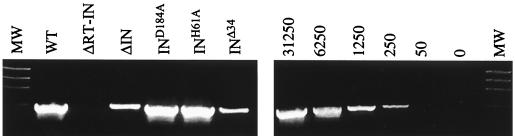

IN mutations impair viral DNA synthesis.

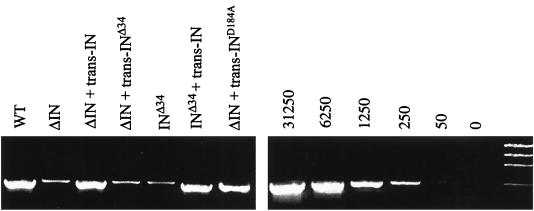

Our earlier studies demonstrated that the HIV-1 IN protein promotes viral cDNA synthesis independently of its enzymatic function (31). The results in Table 1 demonstrated that the infectivity of the ΔIN and Δ34 mutants was consistently about 10-fold less than that of the integration-defective IND184A mutant. Since unintegrated cDNA of the MLV vector can express GFP (Table 2), this result suggested that the ΔIN mutant was more severely impaired in DNA synthesis. To directly analyze viral DNA products of reverse transcription, HeLa cells were infected with normalized amounts of wild-type and IN mutant virions. Total DNA was extracted 18 h later, and cDNA was analyzed by semiquantitative PCR as described earlier (31). Approximately 10- to 20-fold less of the late (R-gag) DNA product was detected in cells infected with the ΔIN and INΔ34 mutants compared with wild type (Fig. 3). Identical results were obtained using primers that detected intermediate products of viral DNA synthesis (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Mutations in IN impair DNA synthesis. Wild-type (WT) and IN mutant (ΔIN, D184A, H61A, and Δ34) pkat-gag-pol were transfected into cultures of 293T cells together with pkat-GFP and pkat-env. After 72 h, the culture supernatants were filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size filters and aliquoted. One aliquot set was analyzed for RT activity, and another set was analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-p30 antibody. The sample volumes of the third aliquot set were normalized based on RT activity or, in the case of the pkat-ΔRT-IN control, the relative densities of the p30 protein. After treatment with RNase-free DNase (4 μg/ml), the virus stocks were placed on cultures of HeLa cells at 37°C. The cells were washed twice with DMEM by low-speed centrifugation after 4 h and lysed after 18 h. Total DNA was extracted, and 400 ng of each extract was analyzed using PCR to detect late (R-gag) viral DNA products of reverse transcription. The amplified products were resolved on 1.5% agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide. As standards, serial fivefold dilutions, ranging from 50 to 13,250 copies of the pkat-GFP plasmid, were analyzed in parallel under identical conditions. The data shown are from a representative experiment that was repeated three times, each time with independent transfection-derived virus preparations. MW, molecular weight markers.

The IND184A and INH61A mutants produced normal amounts of the R-gag DNA product. No viral DNA was detected in cells infected with control ΔRT-IN virions. The synthesis of minus-strand strong-stop DNA was not analyzed because of the lack of a DpnI endonuclease restriction enzyme site in this region to digest contaminating bacterially derived plasmid DNA. These results indicated that the ΔIN and INΔ34 mutants were impaired in reverse transcription of the RNA genome. The magnitude of this defect was consistent with a more severe defect in infectivity compared to the other mutants.

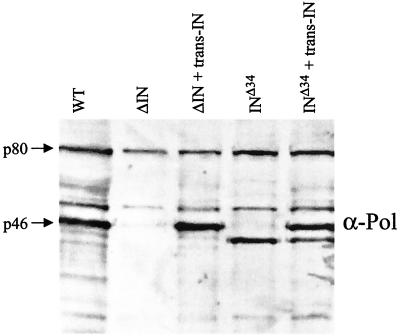

trans-IN protein complements DNA synthesis.

It has been well documented that various mutations in HIV-1 IN impair viral DNA synthesis (11, 15, 19). However, it was not until recently that this phenotype was associated with a direct effect of the mature IN protein on the initiation of reverse transcription (31). Elucidation of this novel IN function was made possible by incorporating IN protein into HIV-1 virions in trans, as a fusion partner of Vpr. This enabled the function of the trans-IN protein to be studied against the background of IN mutant provirus, uncoupling the function of the mature IN protein during early events of the virus life cycle from defects in the Gag-Pol precursor protein and its effects on late events such as assembly. To examine the role of the MLV IN protein in reverse transcription, the IN coding region was fused with gag. This construction (designated pkat-gagΔNCIN) deleted the NC sequence from gag and fused IN in frame at the 3′ end of CA (Fig. 1C). This design was meant to minimize the effects (both positive and negative) of coexpressing wild-type Gag together with the pkat-gag-pol packaging construct (28). To confirm that the trans-IN protein was assembled into virions, the pkat-gagΔNCIN expression plasmid was cotransfected into 293T cells with the ΔIN packaging plasmid, the pkat-GFP-puro gene transfer vector, and the pkat-env plasmid. Progeny virions were shown to contain trans-IN protein that comigrated with wild type (Fig. 4, compare lanes 1 and 3). This result indicated that trans-IN was efficiently incorporated and subsequently liberated by proteolytic cleavage. Similarly, mature trans-IN protein was detected in virions when coexpressed with the INΔ34 mutant packaging construct (lanes 4 and 5).

FIG. 4.

Incorporation of trans-IN into IN mutant virions. Wild-type (WT) and mutant (ΔIN and INΔ34) pkat-gag-pol plasmids were separately transfected into 293T cells by themselves (lanes 1, 2, and 4, respectively) or cotransfected with 1 μg of the pkatΔNCIN trans-IN expression plasmid (lanes 3 and 5). The 293T cell cultures were also transfected with pkat-GFP and pkat-env. After 72 h, the culture supernatants were passaged through 0.45-μm-pore-size filters, pelleted, and examined by immunoblot analysis using anti-Pol antibody.

To determine whether the trans-IN protein rescued viral DNA synthesis, HeLa cells were infected with normalized amounts of each virus stock and analyzed 18 h later for viral DNA. Figure 5 shows that both the ΔIN and INΔ34 mutants synthesized wild-type amounts of DNA when complemented with the trans-IN protein (compare lane 2 with lane 3 and lane 5 with lane 6). As controls, the Δ34 and D184A IN mutations were introduced into the pkat-gagΔNCIN construct, generating pkat-gagΔNCINΔ34 and pkat-gagΔNCINΔ184A, respectively. Virions examined by immunoblot analysis confirmed packaging of the trans-INΔ34 and trans-IND184A mutant proteins (data not shown). Cells infected with the trans-INΔ34-containing virions (lane 4) failed to synthesize greater amounts of viral cDNA while those containing trans-IND184A (lane 7) synthesized near-wild-type levels.

FIG. 5.

trans-IN protein rescues viral DNA synthesis. Wild-type (WT) and mutant (ΔIN and INΔ34) pkat-gag-pol plasmids were separately transfected into 293T cells by themselves (lanes 1, 2, and 5, respectively) or with the pkatΔNCIN, pkatΔNCINΔ34, and pkatΔNCIND184A trans-IN expression plasmids. The culture supernatants were collected 72 h later, filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size filters, and aliquoted. Each aliquot was analyzed exactly as described for Fig. 3. The data shown are from a representative experiment that was repeated three times, each time with independent transfection-derived virus preparations. The rightmost lane contains molecular weight markers.

The infectivity of virions containing trans-IN was examined on monolayer cultures of HeLa cells. trans-IN restored the infectivity of all the mutants (ΔIN, H61A, D184A, and Δ34) by approximately 3 orders of magnitude (Table 3). To specifically analyze the integration function of the trans-IN, the infected cultures were placed on puromycin-containing medium, and after 14 days, the number of resistant, GFP-positive cell colonies was counted. Relative to the number of GFP-positive cell colonies detected 2 days after infection, the number detected after puromycin selection was near that of wild-type Gag-Pol (76% or greater). These results demonstrate that the Gag-IN fusion protein, which was assembled into virions together with IN mutant Gag-Pol precursor protein, functioned to support both viral DNA synthesis and integration.

TABLE 3.

trans-IN complements viral DNA synthesis and integrationa

| Virus | trans-IN | No. of GFP+ cell colonies/ml

|

Post/Preselection ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preselection | Postselection | |||

| wt | − | 8.3 × 106 (100) | 7.8 × 106 | 0.93 |

| + | 7.9 × 106 (95) | ND | ND | |

| ΔIN | − | 2.8 × 103 (0.03) | 8 | 0.08 |

| + | 9.5 × 105 (11) | 7.2 × 105 | 0.76 | |

| D184A | − | 3.5 × 104 (0.42) | ND | ND |

| + | 1.2 × 106 (14) | 9.5 × 105 | 0.79 | |

| H61A | − | 2.0 × 104 (0.24) | ND | ND |

| + | 6.5 × 105 (7.8) | 5.5 × 105 | 0.84 | |

| Δ34 | − | 4.5 × 103 (0.05) | ND | ND |

| + | 7.8 × 105 (9.4) | 6.8 × 105 | 0.87 | |

Viral stocks were prepared as described for Table 2, except that in parallel experiments the pkat-gagΔNCIN plasmid (trans-IN +) was included in the transfection. Supernatants were collected after 72 h, filtered, and used to infect HeLa cells. Two days later, the number of GFP-positive cell colonies was counted, and then 1 μg of puromycin per ml was added to the medium. The number of resistant, GFP-positive cell colonies was determined 14 days later. The numbers in parentheses represent the number of GFP-positive colonies relative to that of wild type (wt; non-trans-IN complemented), which was arbitrarily set at 100. The numbers are representative of two independent experiments. ND, not done.

DISCUSSION

Several studies have examined the effects of MLV IN mutations on different steps in the virus life cycle and demonstrated that many of these mutations dramatically decreased virus infectivity. In using Southern blot analysis to analyze the unintegrated viral DNA following virus infection, IN mutations were not found to cause a defect in viral DNA synthesis, suggesting that reverse transcription occurred normally and that the observed defect in virus infectivity was due to an impairment in integration (8, 24, 25). Using sensitive PCR-based methods to analyze total viral DNA synthesis, our data show that certain IN mutations (ΔIN and INΔ34) decrease viral DNA synthesis 10- to 20-fold. One plausible explanation for our different results is that Southern blot analysis of unintegrated DNA (Hirt supernatants) measures only a portion of the viral DNA that is synthesized. Retroviral DNA exists in three forms in infected cells: integrated, unintegrated linear, and unintegrated circular. Certain IN mutations may change the relative amounts of these three DNA forms without affecting the total amount of viral DNA synthesized. In the case of HIV-1, mutations that affect integration may result in an accumulation of unintegrated circular DNA (10). Therefore, using PCR to directly measure total viral DNA provides a more sensitive and quantitative means to analyze the effect of IN mutations on viral DNA synthesis. Our results showing that certain IN mutations impair viral DNA synthesis are completely consistent with our analysis of virus infectivity. With a highly sensitive assay capable of detecting GFP expression from unintegrated DNA (Tables 1 and 2), the ΔIN and INΔ34 mutant viruses were shown to be consistently 10-fold-less infectious than the IND184A mutant virus. Taken together, our findings demonstrated, for the first time, that certain MLV IN mutations impair viral DNA synthesis in vivo.

We considered two possibilities to explain this finding. First, IN mutation may change the structure of the Gag-Pol precursor and affect late stages of the viral life cycle (such as viral assembly), so as to impair later events including reverse transcription. Second, in the context of uncoating and formation of the reverse transcription complex the mature IN protein itself may augment reverse transcription. Previously, using a trans-complementation approach to package the HIV-1 IN protein independently of the Gag-Pol precursor we demonstrated that the mature HIV-1 IN protein is required for efficient initiation of viral DNA synthesis in infected cells (31). Here, we addressed whether the defect in MLV DNA synthesis was due to a change in Gag-Pol or the mature IN protein by trans-complementing IN mutants with wild-type and mutant Gag-IN fusion proteins. Our results show that the MLV trans-IN restored viral DNA synthesis to normal levels when coassembled with IN mutant-containing Gag-Pol precursor. Importantly, neither the Gag-INΔ34 mutant nor trans-Gag precursor protein (without the IN fusion) rescued this defect. Moreover, GagΔNCIN rescued DNA synthesis at least as well as did a full-length Gag-IN fusion protein (data not shown), ruling out the possibility that NC protein derived from Gag-IN has a positive effect on DNA synthesis (1, 14, 16). Rather, these results indicate that the mature trans-IN protein itself was responsible for the restoration of viral DNA synthesis.

Recent studies of HIV-1 IN demonstrated three distinct phenotypes for IN mutant viruses: those that affect both viral DNA synthesis and DNA integration, those that affect only DNA synthesis, and those that affect only integration (15, 19). Our analysis of MLV indicates that the INΔ34 mutant impaired both integration and viral DNA synthesis, which is consistent with our analysis of HIV-1 IN (31). Disruption of the HIV-1 IN HHCC motif affects both integration and viral DNA synthesis (15, 19, 31). In contrast, our analysis of MLV IN indicates that this motif may not be required for efficient viral DNA synthesis. This result was quite interesting, since the IN HHCC motif is conserved among all retroviruses and retroelements. Future studies will examine the genetic and structural basis for this difference. Our earlier findings for HIV-1 and now for MLV that catalytically defective (e.g., D116A and D184A, respectively) trans-IN complements DNA synthesis indicate a nonenzymatic, structure-based role of IN in viral DNA synthesis. Our results may suggest that this IN function is conserved among retroviruses. Since IN is essential for integrating the viral cDNA into the host cell genome, we suggest that retroviruses may have evolved a mechanism whereby IN acts to trigger viral DNA synthesis to ensure its association with the preintegration complex once reverse transcription is completed. Our findings and those of others (Monica Roth, personal communication) that retroviral IN and RT physically interact may help support this notion (31).

Viral vector systems are often used to study viral gene function since they can mimic that of the parental virus. MLV has been widely used as a vector for gene transfer because of its relatively simple genome organization and ability to infect and integrate DNA into the host cell genome (20). Our analysis of MLV IN was focused on early events of the virus life cycle. The MLV vector preserves all of the cis-acting elements necessary for efficient encapsidation of the viral RNA genome, reverse transcription, and integration. Our choice to utilize the MLV vector, rather than an infectious viral clone, was based, at least in part, on our previous analysis of HIV-1 assembly and IN function. Analysis of HIV-1 integration-defective provirus using HeLa–CD4–β-galactosidase (β-Gal) indicator cells indicated that viral proteins could be expressed from unintegrated DNA. Integration-defective virus induced β-Gal expression at a frequency of approximately 10 to 15% compared with wild-type virus. CD4-positive HeLa cells containing the LTR–β-Gal reporter can detect infection of integration-defective HIV-1 (2, 11, 30). This enabled us to subdivide the early steps of the HIV-1 virus life cycle and specifically analyze the effects of IN mutations on viral DNA synthesis. This was confirmed by our results using PCR methods to analyze unintegrated viral cDNA, which paralleled those using the CD4–HeLa–β-Gal indicator cells (31). In this study, we used the MLV-based vector containing an internal CMV promoter to drive GFP expression as a reporter for DNA synthesis-infectivity. Our results show that unintegrated vector DNA, derived from integration-defective virus, can exist transiently and express GFP (Table 1). By analysis of infected cells for transient gene expression (GFP-positive cell colonies) and proviral DNA integration (puromycin resistance), the frequency of GFP-positive cells was 3 orders of magnitude higher than that of integration (Table 2). Thus, the MLV vector system helped us to uncouple the integration function of IN from its nonenzymatic function. In combination with trans-IN complementation, these approaches may offer new opportunities to study both the enzymatic and nonenzymatic functions of MLV IN in the context of a replicating virus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Alan Rein for the anticapsid (p30) antiserum, Monica Roth for the anti-Pol antiserum, and Stephen Goff for providing the anti-RT antiserum.

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants CA73470 and AI47714 and facilities of the Central AIDS Virus, Genetic Sequencing and Protein Expression Cores of the Birmingham Center for AIDS Research (P30-AI-27767). This research was also supported by a Merit Review Award, funded by the Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allain B, Lapadat-Tapadat M, Berlioz C, Darlix J-L. Trans-activation of the minus-strand DNA transfer by nucleocapsid protein during reverse transcription of the retroviral genome. EMBO J. 1994;13:973–981. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06342.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ansari-Lari M A, Donehower L A, Gibbs R A. Analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase mutants. Virology. 1995;211:332–335. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ansari-Lari M A, Gibbs R A. Expression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase in trans during virion release and after infection. J Virol. 1996;70:3870–3875. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3870-3875.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown P. Integration. In: Coffin J M, Hughes S H, Varmus H E, editors. Retroviruses. Plainview, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 161–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bukovsky A, Göttlinger H. Lack of integrase can markedly affect human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particle production in the presence of an active viral protease. J Virol. 1996;70:6820–6825. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6820-6825.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cannon P M, Byles E D, Kingsman S M, Kingsman A J. Conserved sequences in the carboxyl terminus of integrase that are essential for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. J Virol. 1996;70:651–657. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.651-657.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen W Y, Wu X, Levasseur D N, Liu H, Lai L, Kappes J C, Townes T M. Lentiviral vector transduction of hematopoietic stem cells that mediate long-term reconstitution of lethally irradiated mice. Stem Cells. 2000;18:352–359. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.18-5-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donehower L A. Analysis of mutant Moloney murine leukemia viruses containing linker insertion mutations in the 3′ region of pol. J Virol. 1988;62:3958–3964. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.11.3958-3964.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donehower L A, Varmus H E. A mutant murine leukemia virus with a single missense codon in pol is defective in a function affecting integration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:6461–6465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.20.6461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engelman A. In vivo analysis of retroviral integrase structure and function. Adv Virus Res. 1999;52:411–426. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60309-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engelman A, Englund G, Orenstein J M, Martin M A, Craigie R. Multiple effects of mutations in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase on viral replication. J Virol. 1995;69:2729–2736. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.5.2729-2736.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finer M H, Dull T J, Qin L, Farson D, Roberts M R. kat: a high efficiency retroviral transduction system for primary human T lymphocytes. Blood. 1994;83:43–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallay P, Hope T, Chin D, Trono D. HIV-1 infection of nondividing cells through the recognition of integrase by the importin/karyopherin pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9825–9830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo J, Henderson L E, Bess J, Kane B, Levin J G. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein promotes efficient strand transfer and specific viral DNA synthesis by inhibiting TAR-dependent self-priming from minus-strand strong-stop DNA. J Virol. 1997;71:5178–5188. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5178-5188.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leavitt A D, Robles G, Alesandro N, Varmus H E. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase mutants retain in vitro integrase activity yet fail to integrate viral DNA efficiently during infection. J Virol. 1996;70:721–728. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.721-728.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

16.Li X, Quan Y, Arts E J, Li Z, Preston B D, de Rocquigny H, Roques B P, Darlix J-L, Kleiman L, Parniak M A, Wainberg M A. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein (NCp7) directs specific initiation of minus-strand DNA synthesis primed by human tRNA

in vitro: studies of viral RNA molecules mutated in regions that flank the primer binding site. J Virol. 1996;70:4996–5004. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.4996-5004.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

in vitro: studies of viral RNA molecules mutated in regions that flank the primer binding site. J Virol. 1996;70:4996–5004. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.4996-5004.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - 17.Liu H, Wu X, Xiao H, Conway J A, Kappes J C. Incorporation of functional human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase into virions independent of the Gag-Pol precursor protein. J Virol. 1997;71:7701–7710. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7704-7710.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu H, Wu X, Xiao H, Kappes J C. Targeting human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 2 integrase protein into HIV type 1. J Virol. 1999;73:8831–8836. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8831-8836.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masuda T, Planelles V, Krogstad P, Chen I S Y. Genetic analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase and the U3 att site: unusual phenotype of mutants in the zinc finger-like domain. J Virol. 1995;69:6687–6696. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6687-6696.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller A D. Development and application of retroviral vectors. In: Coffin J M, Hughes S H, Varmus H E, editors. Retroviruses. Plainview, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 437–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nymark-McMahon M H, Sandmeyer S B. Mutations in nonconserved domains of Ty3 integrase affect multiple stages of the Ty3 life cycle. J Virol. 1999;73:453–465. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.453-465.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quillent C, Borman A M, Paulous S, Dauguet C, Clavel F. Extensive regions of pol are required for efficient human immunodeficiency virus polyprotein processing and particle maturation. Virology. 1996;219:29–36. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roth M J. Mutational analysis of the carboxy terminus of the Moloney murine leukemia virus integration protein. J Virol. 1991;65:2141–2145. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.4.2141-2145.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roth M J, Schwartzberg P, Tanese N, Goff S P. Analysis of mutations in the integration function of Moloney murine leukemia virus: effects on DNA binding and cutting. J Virol. 1990;64:4709–4717. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.10.4709-4717.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwartzberg P, Colicelli J, Goff S P. Construction and analysis of deletion mutations in the pol gene of Moloney leukemia virus: a new viral function required for productive infection. Cell. 1984;37:1043–1052. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90439-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shin C-G, Taddeo B, Haseltine W A, Farnet C M. Genetic analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase protein. J Virol. 1994;68:1633–1642. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1633-1642.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swanstrom R, Wills J W. Synthesis, assembly, and processing of viral proteins. In: Coffin J M, Hughes S H, Varmus H E, editors. Retroviruses. Plainview, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 263–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trono D, Feinberg M B, Baltimore D. HIV-1 Gag mutants can dominantly interfere with the replication of the wild-type virus. Cell. 1989;59:113–120. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90874-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vogt P K. Retroviral virions and genomes. In: Coffin J M, Hughes S H, Varmus H E, editors. Retroviruses. Plainview, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 27–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiskerchen M, Muesing M A. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase: effects of mutations on viral ability to integrate, direct viral gene expression from unintegrated viral DNA templates, and sustain viral propagation in primary cells. J Virol. 1995;69:376–386. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.376-386.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu X, Liu H, Xiao H, Conway J A, Hehl E, Kalpana G V, Prasad V, Kappes J C. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase protein promotes reverse transcription through specific interactions with the nucleoprotein reverse transcription complex. J Virol. 1999;73:2126–2135. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2126-2135.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu X, Liu H, Xiao H, Conway J A, Hunter E, Kappes J C. Functional RT and IN incorporated into HIV-1 particles independently of the Gag-Pol precursor protein. EMBO J. 1997;16:5113–5122. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.5113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu X, Liu H, Xiao H, Kim J, Seshaiah P, Natsoulis G, Boeke J D, Hahn B H, Kappes J C. Targeting foreign proteins to human immunodeficiency virus particles via fusion with Vpr and Vpx. J Virol. 1995;69:3389–3398. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3389-3398.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zufferey R, Donello J E, Trono D, Hope T J. Woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element enhances expression of transgenes delivered by retroviral vectors. J Virol. 1999;73:2886–2892. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2886-2892.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]