Abstract

We have studied transcription in vitro by Qβ replicase to deduce the minimal features needed for efficient end-to-end copying of an RNA template. Our studies have used templates ca. 30 nucleotides long that are expected to be free of secondary structure, permitting unambiguous analysis of the role of template sequence in directing transcription. A 3′-terminal CCCA (3′-CCCA) directs transcriptional initiation to opposite the underlined C; the amount of transcription is comparable between RNAs possessing upstream (CCA)n tracts, A-rich sequences, or a highly folded domain and is also comparable in single-round transcription assays to transcription of two amplifiable RNAs. Predominant initiation occurs within the 3′-CCCA initiation box when a wide variety of sequences is present immediately upstream, but CCA or a closely similar sequence in that position results in significant internal initiation. Removal of the 3′-A from the 3′-CCCA results in 5- to 10-fold-lower transcription, emphasizing the importance of the nontemplated addition of 3′-A by Qβ replicase during termination. In considering whether 3′-CCCA could provide sufficient specificity for viral transcription, and consequently amplification, in vivo, we note that tRNAHis is the only stable Escherichia coli RNA with 3′-CCCA. In vitro-generated transcripts corresponding to tRNAHis served as poor templates for Qβ replicase; this was shown to be due to the inaccessibility of the partially base-paired CCCA. These studies demonstrate that 3′-CCCA plays a major role in the control of transcription by Qβ replicase and that the abundant RNAs present in the host cell should not be efficient templates.

Genome replication among the positive-strand RNA viruses is accomplished by sequential end-to-end transcriptions, first of the encapsidated positive sense RNA and subsequently of the newly synthesized negative-sense antigenome. Except for viruses whose genomes are covalently linked at the 5′ end to a specialized protein, these transcriptions occur by de novo initiation (9). For successful replication by this pathway, transcriptional initiation must occur predominantly or exclusively at the 3′ ends of genome and antigenome RNAs, with minimal initiation occurring internally or on other RNAs present within the cell. Qβ replicase provides a convenient means to study the template properties underlying these required specificities for a representative positive-strand RNA virus.

Qβ replicase is the 4-subunit RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) enzyme complex that amplifies the 4.2 kb positive-strand genome of bacteriophage Qβ, a phage infecting Escherichia coli (6, 34). Unlike the RdRp of any eukaryotic positive-strand RNA virus, Qβ replicase has been purified to homogeneity and shown to be capable of supporting the full viral genome amplification cycle in vitro (6). This enzyme catalyzes de novo strand initiation with GTP opposite a short cluster of C residues in the CCCA 3′ termini that are a feature of both positive and negative strands of almost all amplifiable templates described in the literature (24, 26, 40). After full-length transcription, termination is accompanied by the addition of a nontemplated A residue (6), thereby restoring the 3′ A that was not copied into the complementary strand.

While internal sequences whose removal decreases the transcription of Qβ positive- and negative-sense genomic RNAs have been mapped (27, 29), the precise features required for directing the transcription of the genomic RNAs are unclear. Further, these elements are not universally present in the wide variety of short RNAs amplifiable by Qβ replicase (40). Indeed, it was recognized several years ago (26) that the only feature common to replicatable RNAs appears to be the CCCA 3′ terminus; this observation has held true with two exceptions, one being a variant Qβ positive-sense RNA with a UCCA 3′ end (28), the other being a 6S RNA amplified by Qβ replicase with a GCCA terminus (33). Nevertheless, it has not been demonstrated experimentally whether the presence of a CCCA-terminal sequence is all that is required for an RNA to be transcribed by Qβ replicase. Our recent studies have shown that Qβ replicase can direct initiation from every C2-4A repeat present in short linear RNAs comprised of multiple C2-4A repeats (38), a property shared by the RdRps from turnip yellow mosaic and turnip crinkle viruses (39). While these studies suggested that a C2-4A element could act as an independent initiation site, they did not resolve whether overall transcription in these RNAs was supported by the reiterated C-rich sequence motifs; Qβ replicase is well known for its ability to transcribe poly(C) (6). Further, RNAs such as (C2-4A)n are not practical templates for amplification because of the large amounts of internal initiation.

We set out in the present studies to investigate the ability of a C2-4A sequence to act independently to direct transcriptional initiation and to determine what sequences are necessary to ensure that initiation occurs at the 3′-most C residue and not at an internal site, thus ensuring the complete end-to-end copying that is needed for sequence maintenance during replication. The results presented here provide a prescription for the minimal 3′-sequence requirement needed by Qβ replicase for efficient 3′-end initiation on a template. This knowledge provides an explanation for the range of 3′ sequences observed for natural and model RNAs amplifiable by Qβ replicase and insight into the mechanism that ensures the propagation of full-length viral RNA with minimal interference in this process by other RNAs present in the cell. Although there is evidence that internal “promoter” elements specifically recognized by the replicase function in positive-strand RNA viral systems (see, for example, reference 12), including Qβ (the M-site on Qβ positive-sense RNA [27]), such elements are not absolutely required to ensure transcription by Qβ replicase. In this system, we show that a small number of nucleotides at the 3′ terminus of an RNA exert a crucial influence over the fate of that RNA as a template.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Qβ replicase, a generous gift from Michael Farrell (Vysis, Inc.), was prepared by overexpression in E. coli (20). Synthetic DNA oligomers used for the preparation of template RNAs were synthesized by Life Technologies, Inc., or at the Central Services Laboratory of the Center for Gene Research and Biotechnology, Oregon State University.

Preparation of RNA templates for Qβ replicase assays.

Template RNAs were prepared enzymatically with T7 RNA polymerase from DNA templates comprising annealed DNA oligomers as described previously (38) or from templates generated by PCR as described previously (30) in the case of E. coli tRNAHis and its derivatives. All of the DNA templates, other than those used to make CCCA9 and CCCCA7 RNAs (see Fig. 3) and GGA(CCA)7X RNAs (see Fig. 5B), contained modified 2′-O-methyl uridine and/or 2′-O-methyl guanosine at the two 5′-most nucleotide positions to suppress the formation of n + 1 transcripts (17). Transcripts were purified by 7 M urea–10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) with single-base resolution. Concentrations of RNA solutions were determined by spectrophotometry by using extinction coefficients calculated by Oligo 6.0 software.

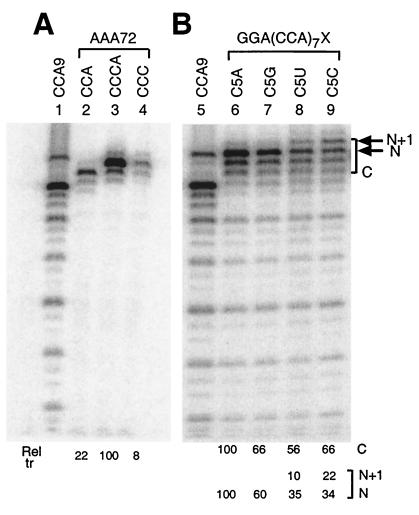

FIG. 3.

C3-5A sequences provide optimal 3′ initiation sites. The RNAs shown in panel A were analyzed as transcriptional templates for Qβ replicase (panel B) as described in Fig. 2. The relative levels of transcription (% of total, with reference to box #8 of CCA9) originating from boxes #8 and #9 of each RNA are given below each lane (average of three experiments; typical standard deviation = 10 to 20%); note that for lanes 14 and 15, the numbers refer to initiation from the 3′ and 3′-penultimate boxes, respectively. Below these figures are shown the proportions of transcripts >12 nt in length originating from box #9 (as well as box #8 for CCA9) as a percentage.

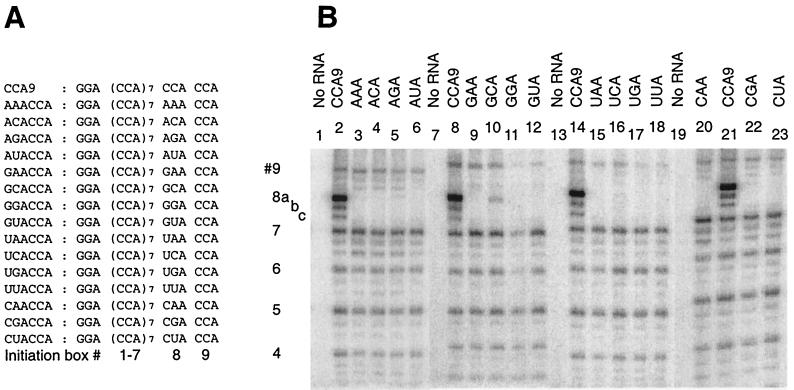

FIG. 5.

Role of the 3′-terminal A residue. Two families of RNAs are analyzed as transcriptional templates for Qβ replicase as described in Fig. 2. In lanes 2 to 4, derivatives of AAA72 RNA with the indicated 3′ ends are analyzed: the AAA72 RNA family has the sequence GGA5UA6UA5UA6 upstream of the indicated C-rich initiation box. In lanes 6 to 9, derivatives of GGA(CCA)7X RNA, with the indicated 3′ ends representing X, are analyzed. The major end-to-end transcription product is marked N at the right side of the figure, with the upper band evident in lanes 8 and 9 marked N+1. The entire cluster of bands originating from the initiation boxes of the RNAs in lanes 6 to 9 is bracketed and labeled “C.” The relative percent transcription yields are given below each lane, separately for C, N, and N+1 in panel B. The yields of products in lanes 3 and 6 were 170 and 125%, respectively, relative to transcription from box #8 of CCA9 RNA. The RNAs in lanes 6 to 9 were previously analyzed (38) at 21 mM MgCl2, which favors internal over 3′-end initiation.

Qβ replicase assay and analysis of products.

Typical Qβ replicase reactions (25 μl) contained 2.5 pmol (100 nM) of template RNA and 1.25 pmol (50 nM) of Qβ replicase in 80 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5); 10 mM MgCl2; 1 mM dithiothreitol; 200 μM concentrations each of ATP, GTP, and UTP; and 50 μM CTP, including 10 μCi of [α-32P]CTP. The experiments of Fig. 1 were conducted in the presence of 21 mM MgCl2 as in previous studies (38); we have adopted 10 mM MgCl2 as our standard reaction condition to make our experiments more representative of conditions used by other researchers. Incubation was for 10 min at 37°C, and products were recovered by phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation. At the time of ethanol precipitation in the case of CCA9 RNA and its GGA(CCA)7NNACCA derivatives, 250 pmol of DNA oligomer complementary to the T7 transcript of CCA12 RNA was added; this DNA promotes displacement of the template RNAs from the Qβ replicase products during sample preparation for electrophoresis. In other cases, 250 pmol of DNA exactly complementary to the RNA template was added as described above, except for the RNAs analyzed in Fig. 6, for which no antisense nucleic acids were used.

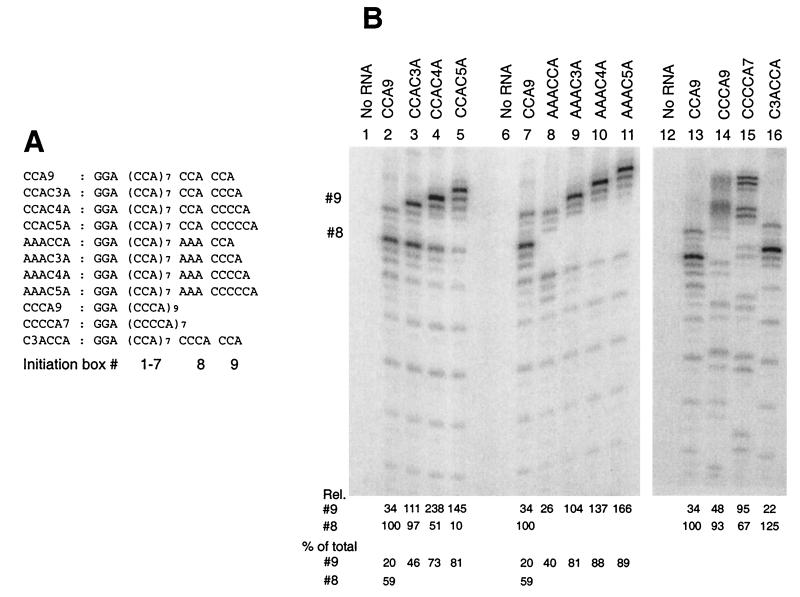

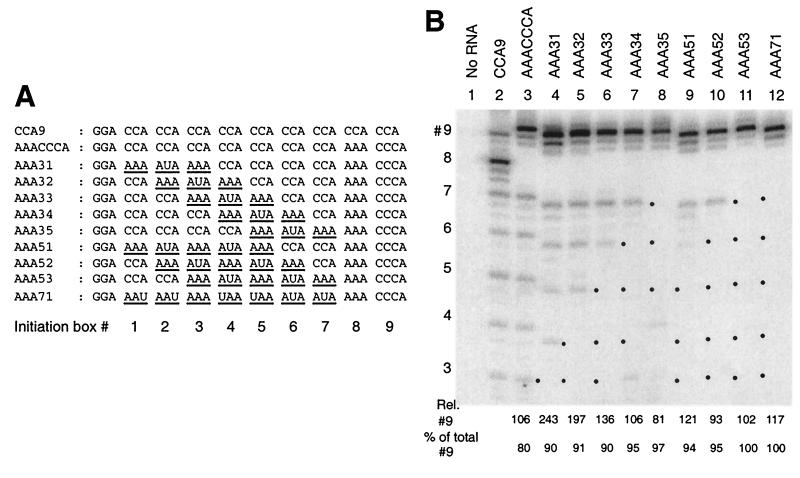

FIG. 1.

Inactivation of the 3′-penultimate CCA initiation box does not increase initiation from the 3′-CCA initiation box. RNA variants derived from CCA9 RNA, bearing the mutations of the C residues in initiation box #8 shown in panel A, were tested as templates with Qβ replicase. RNAs were incubated in the presence of Qβ replicase and [α-32P]CTP for 10 min at 37°C as described in Materials and Methods, except that MgCl2 was present at 21 mM. Products made from templates identified by their initiation box #8 sequence were separated by 12.5% denaturing PAGE (shown in panel B). The numbers at the left identify the CCA repeat (initiation box numbers) from which product strands originate, #9 representing the 3′-most CCA. Each CCA initiation box produces three products, marked a, b, and c at the left, whose origins are explained in the text.

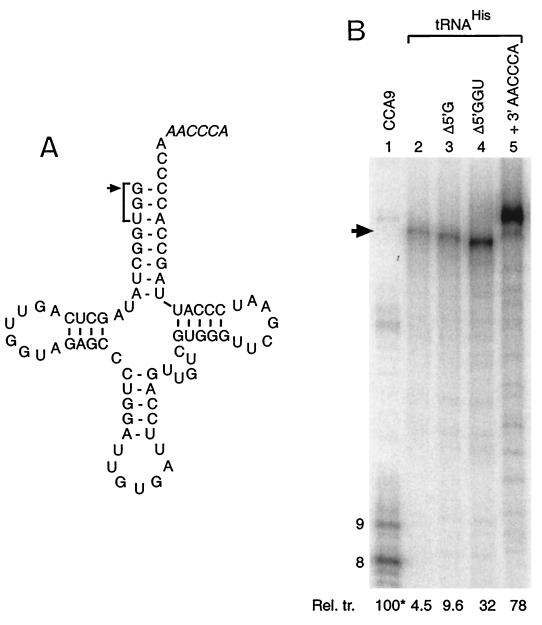

FIG. 6.

E. coli tRNAHis is a poor template for Qβ replicase because its 3′ terminus is unavailable. (A) Sequence of tRNAHis (lacking posttranscriptional modifications). The arrow marks the additional 5′-nucleotide (G) that is unique to tRNAHis and that is absent from the RNA template used in lane 3 of panel B. The bracket encompasses the 5′-GGU missing from the template tested in lane 4. The additional 3′ sequence present on the RNA tested in lane 5 is shown in italics. (B) Transcription products generated from the indicated templates after incubation with Qβ replicase as described in Fig. 2, except that analysis is by 10% denaturing PAGE. The relative molar transcription levels (Rel. tr. [percent], with reference to box #8 of CCA9, 100*) originating from each RNA is given at the foot of each lane (average of three experiments; typical standard deviation = 10 to 20%).

Dried pellets recovered after ethanol precipitation were dissolved in 50 μl of 90% formamide–10 mM EDTA–0.02% dyes, boiled for 5 min, and ice-chilled, and then 10 μl was subjected to 7 M urea–PAGE. After electrophoresis, gels were fixed and dried, and radioactivity was detected and analyzed with a PhosphorImager with ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics).

Single-round transcription assays.

Assays were performed as described above, except that CTP was initially withheld. After incubation for 1 min at 37°C, polyethylene sulfonate (PES) was added to 5 μg/ml, followed by 50 μM CTP, including 10 μCi of [α-32P]CTP. The assay was completed by incubation at 37°C for 9 min, followed by product analysis as described above.

RESULTS

A CCCA 3′ terminus is superior to CCA at directing initiation predominantly from the 3′ end.

Our previous experiments have shown that (CCA)n RNAs of ca. 30 nucleotides (nt) or longer are good templates for Qβ replicase (38), supporting a cumulative level of RNA strand initiation similar to that observed with an amplifiable positive control RNA, DN3 (39). However, most initiation on such RNAs occurs upstream of the 3′ end (38) (see also Fig. 1, lanes marked CCA9), resulting in sequence loss that is incompatible with the requirements of viral RNA replication. More precisely, predominant initiation occurs opposite the downstream C of the 3′-penultimate CCA repeat (CCACCA, in box #8; 59% of the initiation products were longer than 12 nt), with weaker initiation opposite the 3′-most C (CCACCA, in box #9; 17% of initiations; Fig. 1, lanes 2, 8, 14, and 21). Note that the band heterogeneity present as bands 8a, b, and c in the above lanes is principally due to differences at the 3′ end of the product, a finding we have reported previously (38) and reconfirmed in this study (not shown). Whereas the longer CCA12 RNA (38) produces mainly doublets, CCA9 RNA yields the triplets labeled a, b, and c. Our studies indicate that (i) the “a” band represents transcription to the 5′ end of the template, followed by addition of a nontemplated A (25, 36) (CCA 3′ end), (ii) the “b” band represents a mixture of full-length transcripts that fail to acquire an additional A (CC 3′ end) and those that terminate 1 nt early and acquire a nontemplated A (CA 3′ end), while (iii) the “c” band represents termination 1 nt early with no adenylation (C 3′ end). We have shown that this pattern of products holds true with initiation from 3′-CCCA by labeling RNAs AAA71, AAA51, and AAA31 (see Fig. 4) with [α-32P]CTP and inspecting RNase T1-released fragments (results not shown).

FIG. 4.

Upstream CCA boxes contribute little to initiation from a 3′-CCCA sequence. (A) Derivatives of AAACCCA RNA in which CCA boxes #1 to #7 have been replaced progressively with A-rich sequences (underlined). (B) Analysis of the same RNAs as transcriptional templates for Qβ replicase, performed as described in Fig. 2. The dots placed to the left of lanes indicate absent signals from the mutated initiation boxes. The relative level of transcription (percentage of total, with reference to box #8 of CCA9) originating from box #9 of each RNA is given below each lane (average of three experiments; typical standard deviation = 10 to 20%), as is the proportion (percentage of total) of transcripts >12 nt in length originating from box #9.

To test whether the predominant initiation at CCA box #8 in CCA9 RNA results from the suppression of initiation from the 3′-terminal CCA box #9, we studied the spectrum of transcription products in a family of 15 templates in which the C residues of box #8 were mutated with single or double substitutions to NNA. As shown in Fig. 1, all single or double mutations in CCA9 RNA resulted in the almost complete loss of initiation from box #8, with little or no other changes in the spectrum of initiations from other sites. Most significantly, mutation of box #8 did not result in increased and preferential initiation from the 3′ end (box #9). The observations were uniform, regardless of whether the substitution of C was with the pyrimidine U or the purines A or G, at position −5, position −6, or both. These results indicate that the absence of predominant initiation from the 3′ end in CCA9 RNA is mostly due to the absence of an appropriately strong initiation signal and not due to competition by an upstream CCA.

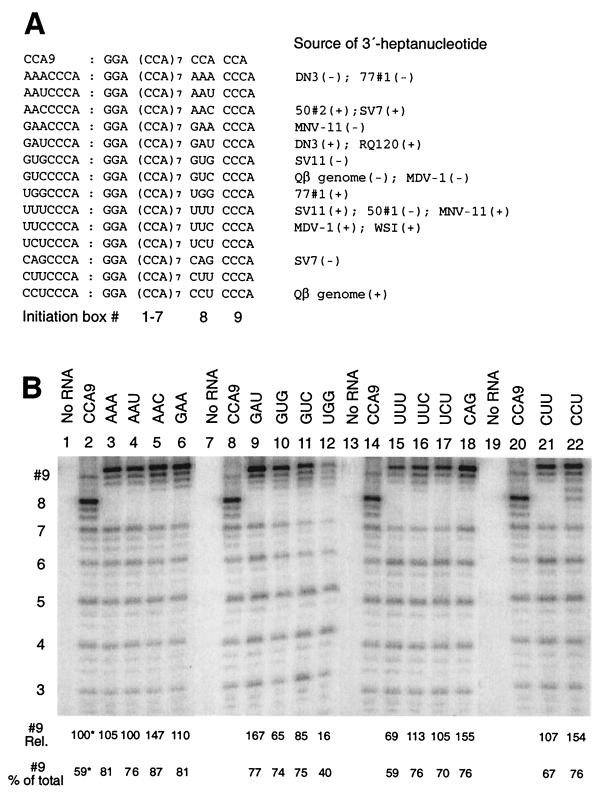

Thus, although the sequence CCA clearly does constitute a functional initiation box, the results of Fig. 1 indicate it is relatively weak in directing initiation from the 3′ terminus of an RNA. Indeed, RNAs reported in the literature as being amplifiable by Qβ replicase typically terminate in NCCCA (26, 34, 40), suggesting that a 3′-CCCA rather than 3′-CCA is necessary to ensure preferential initiation from the 3′ terminus. To test this idea, we studied transcription from a second family of templates based on CCA9 RNA, in which the CCACCA terminus was replaced with NNNCCCA. Of the 14 3′-heptanucleotide sequences tested, 11 were derived from the published sequences of amplifiable RNAs (Fig. 2A). As is evident from Fig. 2B, a CCCA terminus ensures predominant initiation from the 3′ end in the presence of a variety of trinucleotide sequences immediately upstream (mutations in initiation box #8). A total of 59 to 87% of all products longer than 12 nt initiated from within the CCCA initiation box for all templates tested, except for UGGCCCA RNA (Fig. 2B, lane 12), which was a poor template overall (accessibility probing with RNases suggested that this RNA exists in solution with some undetermined secondary structure, which presumably interferes with template activity). In contrast, 59% of the products longer than 12 nt transcribed from CCA9 RNA originated from the 3′-penultimate CCA initiation box (#8), with only 20% of the initiations occurring from the 3′-CCA (box #9). No change in product spectrum was observed when representative RNAs from Fig. 1 and 2 were analyzed under single-round transcription conditions in the presence of 5 μg of PES/ml (data not shown). There is therefore no indication of preferential reinitiation at certain sites.

FIG. 2.

A CCCA 3′-initiation box directs strong 3′-terminal initiation from a wide range of adjacent sequences. (A) RNAs in which the 3′-CCACCA of CCA9 RNA was changed to 3′-NNNCCCA were incubated in the presence of Qβ replicase and [α-32P]CTP for 10 min at 37°C as described in Materials and Methods, with MgCl2 present at 10 mM. As indicated, many of the 3′-heptanucleotide sequences were derived from the 3′ termini of RNAs exponentially amplifiable by Qβ replicase: Qβ genome(+), WSI (26); Qβ genome(−) (34); MDV-1 (24); DN3 (40); RQ120 (21); 50#1, 50#2, and 77#1 (7); MNV-1 (2); SV7 (GenBank accession no. L07339); and SV11 (GenBank accession no. L07337). (B) Analysis of transcription products labeled with [α-32P]CTP and separated by 12.5% denaturing PAGE, with templates identified by the sequence of their modified initiation box #8. The relative levels of transcription (with reference to box #8 of CCA9) originating from box #9 of each RNA is given at the foot of each lane (average of three experiments; typical standard deviation = 10 to 20%). Below the panel is shown the proportion (% of total) of transcripts >12 nt in length originating from box #9 (box #8 for CCA9). ✽, Quantitation of transcription from box #8 in the case of CCA9 RNA.

Similar levels of initiation were observed when the CCCA 3′-terminal initiation box was adjacent to various sequences (Fig. 2, mutated box #8), indicating that these adjacent sequences have little influence on transcription by Qβ replicase. The level of initiation from CCCA was similar to that from CCA box #8 of CCA9 RNA.

Relative initiation strength from 3′-most and 3′-penultimate initiation boxes is influenced by the number of cytosine residues.

The results presented above show that a CCCA initiation sequence is superior to CCA at the 3′ end, although CCA provides strong initiation from a position slightly internal to the 3′ end. To explore the relationship between initiation from these two positions, we analyzed transcription from RNAs with different numbers of cytosines in either the 3′ or 3′-penultimate initiation boxes. The addition of increasing numbers of C residues to box #9 of CCA9 RNA dramatically switches the initiation preference from box #8 to the 3′ end (Fig. 3B, lanes 1 to 5). Thus, the ratio of products initiating from box #9 relative to box #8 increases from 0.29:1 for CCA9 to 1.1, 4.7, and 14:1 when the 3′ box (#9) has the sequences C3A, C4A, and C5A, respectively (Fig. 3B).

In the absence of a functional 3′-penultimate initiation box (Fig. 3B, lanes 8 to 11), predominant end-to-end transcription is driven by 3′ initiation boxes with three, four, or five C residues. In these cases, 80 to 90% of products longer than 12 nt originate from the 3′ end (Fig. 3B). The level of transcription was some 30 to 60% higher from 3′-C4A or 3′-C5A than from 3′-C3A, indicating that C strings longer than three can provide modest additional initiation strength. Initiation from 3′-CCA is at about the same low level in the presence or absence of CCA at box #8 (Fig. 3B, lanes 7 versus 8), indicating that initiation boxes #8 and #9 act largely independently rather than in competition (compare also transcription from box #9 of Fig. 3, lanes 3 to 5 versus lanes 9 to 11). The decreasing level of transcription from box #8 in lanes 2 to 5 of Fig. 3B is attributable to the increasing distance from the 3′ end as C residues are added to box #9. Thus, box #8 of CCAC5A RNA (lane 5) is actually at the same position relative to the 3′ end as box #7 of CCA9 RNA (lane 2), and both show similar amounts of initiation.

Increased numbers of C residues at the 3′-penultimate initiation site leads to a higher ratio of initiation from the 3′-penultimate relative to 3′ boxes (Fig. 3B, lanes 16 versus 13). With more C residues at both sites, 3′ initiation becomes relatively more favored, although internal initiation is still important (Fig. 3B, lanes 14 and 15). These results indicate that the proportion of end-to-end transcription is strongly influenced by the CnA sequences present at and adjacent to the 3′ end. At both positions, but particularly at the 3′ end, initiation is favored by a larger number of C residues. Our results refine previous findings (15) that somewhere between 5 and 20 3′-C residues are able to activate transcription of an RNA by Qβ replicase.

To what extent do the upstream CCA boxes of AAACCCA and related RNAs contribute to transcription?

The template activities of AAACCCA and related RNAs analyzed in Fig. 2 indicate the capacity of 3′-CCCA to independently direct initiation, unsupported by a neighboring CCA box. However, we were interested to know whether the seven contiguous upstream CCA boxes were important contributors to the strong initiation from the 3′ end. Such a contribution seemed plausible in view of the well-known ability of Qβ replicase to transcribe poly(C) but not other homopolymers (6) and the prevalence of pyrimidine-rich sequences in replicons (7). To experimentally address this question, we analyzed transcription from variants of AAACCCA RNA in which (CCA)3 segments were changed to A4UA4 (RNAs AAA31 to AAA35), (CCA)5 segments were changed to A4UA5UA4 (RNAs AAA51 to AAA53), and (CCA)7 to (A2UA2UA)3 (AAA71 RNA) (Fig. 4A). The interspersed U residues were designed to prevent the replicase slippage anticipated on longer A tracts. As well as testing a role for C clusters as nonspecific transcriptional enhancers, these RNAs permitted testing a role for a short C cluster at an appropriate spacing upstream of the 3′-initiation box in enhancing transcription (proposed in reference 18), perhaps by binding to so-called Site II of the EF-Tu subunit (8).

All of the modified RNAs showed robust predominant initiation from the 3′ end (Fig. 4). Similar results were obtained with variants in which CCA boxes #1 to 7 were individually changed to AAA (not shown). Most convincingly, AAA71 RNA (Fig. 4B, lane 12), which lacks any C residues upstream of the 3′-CCCA initiation box, supported similar levels of end-to-end transcription as the AAACCCA parental RNA (lane 3); essentially all transcription was end to end. Similarly strong end-to-end transcription was observed from AAA72 RNA (Fig. 5, lane 3; 170% transcription relative to box #8 of CCA9), an RNA related to AAA71 RNA, but with only three U residues in the A-rich tract upstream of the 3′-CCCA. Mutation of each CCA box individually from the various RNAs tested in Fig. 4 resulted in the loss of initiation from that site (indicated with a dot next to each lane) but only modest (if any) changes in the initiation levels from adjacent CCA boxes. These results indicate that all CCA boxes serve as independent initiation sites and that the upstream CCA tract provides little or no enhancement of transcription initiation from the 3′-CCCA. The notion of a role for an upstream C cluster (18) has been questioned by the inapparent conservation of such a feature among RNAs amplifiable by Qβ replicase (26).

Contribution of the 3′-A to initiation box function.

The role of the 3′-A in the CCCA 3′-initiation box was tested by observing transcription from AAA72 RNA with the 3′-A present or absent (3′-CCCA and 3′-CCC termini, respectively). AAA72 RNA lacking the 3′-A yielded less than one-tenth the amount of transcript produced from full-length AAA72 RNA (Fig. 5, lanes 3 and 4), indicating the importance of the addition of nontemplated A by Qβ replicase to the 3′ end of product strands. Transcription from the 3′-CCC terminus was even poorer than from AAA72 RNA terminating in 3′-CCA (Fig. 5, lane 2). Comparison of the same three termini on two other RNAs likewise emphasized the importance of the 3′-terminal A residue: with both GGA(CCA)7AAAX and GGA(CCA)7CCUX RNAs, where X is CCA, CCCA, or CCC, about one-fifth the level of transcription observed from CCCA ends was observed for both CCA and CCC ends (not shown). Our results are consistent with studies reporting 33% template activity for Qβ genomic RNA lacking the 3′-A of Qβ genomic RNA (25), suggesting fundamentally similar recognition of the 3′ termini of the viral RNA and the synthetic templates we have used here.

A specific role for A at the 3′ end was tested with a GGA(CCA)7C5N RNA family, in which N was A, G, U, or C. Transcription was strongest with a 3′-A (Fig. 5, lane 6), and 56 to 66% that level with the other nucleotides at the 3′ end (lanes 7 to 9) when quantitated on the basis of the entire cluster of bands derived from the C-rich initiation box (bracketed “C” in Fig. 5B). The yield of full-length transcript (band N) was only 34 to 35% from RNAs with a 3′-C or -U (relative to RNA with 3′-A), reflecting the presence of considerable band heterogeneity in the “C” clusters of lanes 8 and 9. This heterogeneity includes an additional band N + 1, which could reflect initiation opposite the additional 3′-pyrimidine, stuttering during initiation, or a gel artifact: despite the use of antisense DNA to hybridize the template molecules (see Materials and Methods), some replicase products are harder than others to completely denature, and a shadow or faint band at the N + 1 position is occasionally seen. For the RNAs with 3′-U or -C (lanes 8 and 9), the band heterogeneity is also expressed as the N band being less prominent than the bands immediately below: we do not know whether this reflects staggered initiation at alternative C residues or a differential heterogeneity introduced during termination.

In summary, a 3′-A is an important feature of a template with three C residues in the 3′-initiation box, although it is less important when more C residues (five or six) are present. In the latter case, a 3′-A additionally has a potential role in minimizing initiation heterogeneity.

A 3′-CCCA initiation box alone supports transcription at levels similar to that seen with replicon RNAs.

Having concluded from the above study that no specific sequence other than a 3′-CCCA (or closely related sequences) is required for transcription by Qβ replicase, we wanted to test whether the transcription levels seen with our short, linear RNAs are comparable to those supported by RNAs capable of amplification. Transcription of CCA9, AAACCCA, and AAA71 RNAs (Fig. 4) was compared with product synthesis from two replicon RNAs capable of amplification by Qβ replicase: MDV and DN3 RNAs. Single-round transcription was studied through the addition of the polymerase scavenger PES (see Materials and Methods). In the presence of PES, AAACCCA and AAA71 RNAs (each 31 nt long) yielded similar amounts of transcript as DN3 RNA, a replicon of similar length (34 nt [40]) (Table 1). Some 3.5 times more transcript was obtained from MDV RNA, a 225-nt-long replicon (Table 1). We have previously observed a marked length effect with short transcripts, CCA12 (39 nt) supporting about three times the transcription derived from CCA9 RNA (38). The increased transcription from MDV relative to AAA71 RNA may be due to its greater length or other properties, such as the presence of a replicase recognition site (22). Nevertheless, the model RNA AAA71 with transcription driven solely by a 3′-CCCA initiation box supports transcription levels comparable to those of replicon RNAs. Similar results were observed at 10-fold-lower template and replicase concentrations of 10 and 5 nM, respectively (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Single-round transcription of RNAs by Qβ replicasea

| RNA template | % Relative molar transcription (+ PES) (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|

| DN3 | 86 ± 5 |

| MDV | 347 ± 63 |

| CCA9 | 54 ± 7 |

| AAACCCA | 88 ± 1 |

| AAA71 | 100 |

Transcription reactions were performed as described in Materials and Methods in the presence of the polymerase scavenger PES, added after a 1-min preincubation in the absence of CTP. DNA3 RNA is a 34-nt amplicon with the 3′ sequence GAUCCCA (40). The MDV RNA was a variant of MDV-1 (19) referred to as Syn5.0 RNA (10). The figure entered for CCA9 RNA refers to transcription initiating from CCA box #8.

Can a 3′-CCCA transcription signal provide sufficient template specificity in vivo?: the case of tRNAHis.

While the results presented above indicate that an accessible CCCA positioned at the 3′ end of an RNA is sufficient to make that RNA a strong template for Qβ replicase, we were concerned that this may not be sufficiently specific to prevent transcription of some of the abundant stable RNAs present in an E. coli cell, especially some of the tRNAs, all of which end in the conserved 3′-CCA. Perusal of the sequences of all E. coli tRNAs (32; http://www.uni-bayreuth.de/departments/biochemie/trna/) and other RNAs (Blattner et al., http://www.genome.wisc.edu/k12.htm) revealed that only tRNAHis has a 3′-CCCA. Note, however, that tRNAHis is also unique in possessing an additional 5′-G relative to other tRNAs, resulting in the underlined “discriminator base” being base paired (Fig. 6A).

To see whether tRNAHis could serve as a template for Qβ replicase, we synthesized by in vitro transcription a form of the RNA lacking the usual base modifications (Fig. 6A). Only weak end-to-end transcription was supported by the tRNAHis transcript (4.5% yield relative to transcription from box #8 of CCA9; Fig. 6B, lanes 1 and 2). To test whether this weak transcription was due to the poor accessibility of the 3′-CCCA, transcription was also tested from three variants which either lack the 5′-G or 5′-GGU or have an additional AACCCA at the 3′ end. Removal of bases from the 5′ end progressively resulted in increased transcription (Fig. 6B, lanes 3 and 4), while addition of the 3′-AACCCA resulted in a still-higher level of transcription (78% relative to box #8 of CCA9). This latter level of transcription is comparable to that observed from AAA71 and other RNAs in Fig. 4 that terminate in 3′-CCCA, indicating that the body of the tRNA neither enhances nor represses transcription directed by the CCCA initiation box. These results demonstrate that host tRNAHis is only a poor template for Qβ replicase and that this is due to the inaccessibility of the initiation site due to base pairing.

Transcription initiation from a 3′-UCCA terminus.

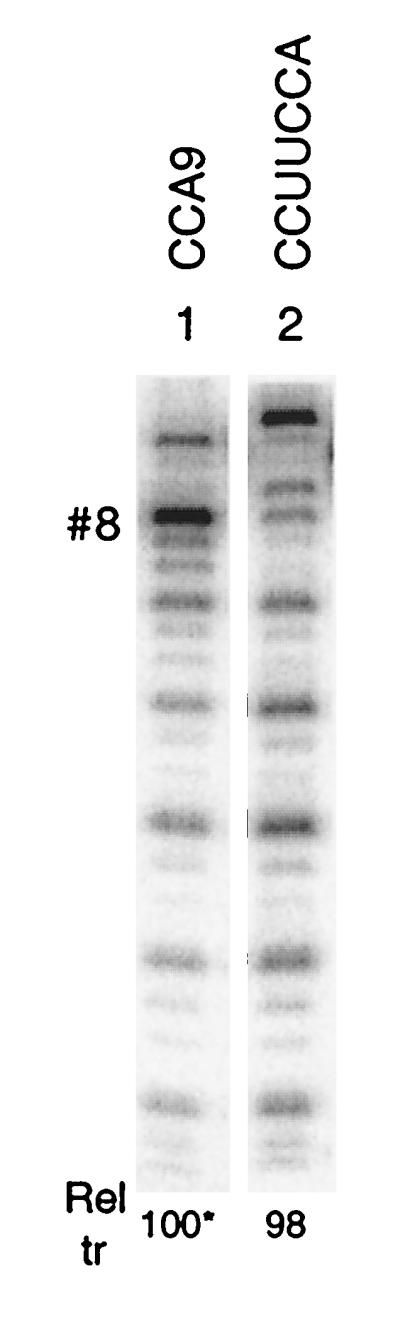

The results shown in Fig. 1 to 6 clearly demonstrate the ability of 3′-CCCA and related sequences with additional C residues to direct transcription by Qβ replicase, explaining the presence of such sequences at the 3′ ends of almost all replicons. However, we know of two instances in the literature that deviate from this rule: a host factor-independent variant of Qβ RNA that is able to amplify in vivo and has a CCUUCCA 3′ end (28) and a 6S RNA amplifiable in vitro with a GCCA 3′ end (33). We have tested the ability of the UCCA terminus to support transcription initiation by Qβ replicase with GGA(CCA)7CCUUCCA RNA as a template. This RNA supported a 98% end-to-end transcription level relative to transcription from box #8 of CCA9 RNA (Fig. 7), showing that at least with certain adjacent sequences a UCCA 3′ end is capable of supporting robust initiation. The levels of initiation from internal CCA boxes was elevated about twofold for this RNA relative to CCA9 RNA, suggesting that the absence of competing initiation sites may be more important with a UCCA 3′ end in a replicon RNA.

FIG. 7.

Transcription from a 3′-UCCA terminus. Transcription from GGA(CCA)7CCUUCCA and CCA9 RNAs by Qβ replicase was compared as described in Fig. 2. CCA9 RNA (30 nt) is the shorter of the two RNAs by 1 nt.

DISCUSSION

An accessible CCCAOH initiation box is sufficient to promote robust transcriptional initiation by Qβ replicase.

The results presented in Fig. 2 to 5, using short unstructured model templates, show that a 3′-CCCA terminus can direct strong end-to-end transcription by Qβ replicase in association with a number of adjacent and upstream sequences. We have also demonstrated that a 3′-CCCA initiation box can function as the sole transcriptional control element in a template. Related 3′ termini with four or five C residues direct somewhat more initiation (Fig. 3). A 3′-ACCA terminus is relatively ineffective at directing initiation from the 3′ end (Fig. 3), although UCCA can support significant initiation (Fig. 7). The level of transcription observed from 3′-CCCA is approximately the same regardless of whether the upstream region of the template is comprised of CCA repeats, an A-rich sequence, or a mixture of the two (Fig. 4). Similar levels of transcription were also observed when a structured RNA (tRNAHis) that is itself a weak template was provided with an accessible 3′-CCCA initiation site (Fig. 6). The levels of transcription observed from the short linear RNAs with a 3′-CCCA initiation box are similar to those supported by RNAs capable of amplification by Qβ replicase (tested in single-round transcription assays; Table 1). These experiments provide a clear demonstration of the importance of a 3′-CCCA terminus in directing productive end-to-end copying by Qβ replicase; its importance has previously been deduced from comparison of the sequences of amplifiable RNAs (26).

The 3′-most A residue of a CCCA initiation box plays a critical role, its removal leading to a 5- to 10-fold decrease in end-to-end transcription (Fig. 5A and experiments not shown). With an initiation box containing five C residues, the role of a terminal A is less distinct, its substitution with another base resulting in less than a twofold drop in transcription level (Fig. 5B). However, since Qβ RNA and its related short replicons typically possess 3′-initiation boxes with three or four C residues (e.g., see Fig. 2A), the 3′-A must be a critical feature of RNAs replicated in the cell by Qβ replicase. It is interesting that this A is not templated by the RNA being transcribed but rather is added by the replicase in a step associated with termination (25, 36). Nontemplated 3′-terminal residues are common among eukaryotic positive-strand RNA viruses (9, 13, 37) and have also been observed to be necessary for efficient transcription from the 3′ end (see, for example, references 14 and 31). In cases where the viral RdRp itself is responsible for the nontemplated addition, this activity could be a viable target for antiviral drugs.

We have previously reported the inability of Qβ replicase to initiate transcription from a base-paired initiation box (39), and the importance of a 3′ end free of secondary structure was earlier deduced from the properties common to replicating RNAs (4, 26). The results shown in Fig. 6 further demonstrate the importance of an accessible initiation site. Although the 3′-CCCA of E. coli tRNAHis lacking its normal 5′-G (Fig. 6, lane 3) is not base paired, it is poorly used by Qβ replicase. Transcription is increased by positioning the 3′-A at the end of a 6-nt unpaired tail (lane 4) and even more by positioning it at the end of a 9-nt single-stranded tail (lane 5). These results seem to indicate that an unstructured 3′ end more than 6 nt long is preferred by the enzyme active site for initiation at the 3′ end. The existence of base pairing at the 3′ end of Qβ RNA (3) is thought to be an important contributing factor in the requirement for host factor (Hfq) in positive-strand RNA transcription. 6S RNAs, which have unstructured 3′ ends, are transcribed independent of the host factor (6). Interestingly, the addition of CC to the 3′ end of Qβ RNA largely removes the Hfq dependence (28); applying the conclusions from our study, we can attribute this effect to a more extended single-stranded initiation site and the increased transcriptional strength derived from the additional C residues.

Optimal templates lack CCA or a closely related sequence adjacent to the 3′ end.

The results in Fig. 3 show that predominant initiation at the 3′ end (and consequently end-to-end transcription that is productive for replication) is not guaranteed by a 3′-CCCA. When C2-4A is present immediately upstream, considerable internal initiation can occur: in this position, CCA is about as potent an initiation site as CCCA is at the 3′ end (Fig. 3). Neither CCA, CCCA, nor CCCCA serve as strong initiation sites when placed further from the 3′ end (Fig. 3, lanes 13 to 15), although we have observed substantial initiation from a C8A tract 15 nt from the 3′ end of an RNA (39). A priority in the evolution of a Qβ replicon would thus clearly be the avoidance of C2-4A or related C-rich sequences immediately upstream of the 3′ initiation box or at least the placement of such sequences in base-paired structures. In fact, RNAs amplified by Qβ replicase typically lack C-rich sequences in this position (see box #8 in the RNAs listed in Fig. 2A). An exception is Qβ positive-strand RNA, in which CCU lies upstream of the 3′-CCCA. We have previously shown that A, and to a lesser extent G but not U, punctuating a run of C residues is critical in defining an internal initiation site (38): that is, initiation will occur from the 3′ end of a run of C-rich pyrimidine residues, either adjacent to a purine (preferably A) or from the 3′ end of the RNA. Thus, the CCUCCCA 3′ end of Qβ positive-strand RNA should not suffer from excessive internal initiation.

It is interesting that CCA suffices for strong internal initiation from near the 3′ end, whereas an additional C (i.e., CCCA) is required for a comparable level of initiation from the 3′ terminus. The polymerase active site has a clear preference for engaging a C-rich initiation box with a short 3′ overhang, which presumably stabilizes the template-enzyme interaction. The recent crystal structure of the RdRp of the double-stranded RNA bacteriophage φ6 (11), which has revealed strong similarities to the RdRp of the positive-strand RNA hepatitis C virus, suggests how such an overhang may provide initial binding stability. Cocrystallization of the RdRp with a DNA template mimic and subsequently with initiating nucleotide GTP showed that the template initially binds with its 3′-C positioned in a “specificity pocket” that is one nucleotide-equivalent beyond the active site. With GTP present, the template ratchets back to position the 3′-C in the active site to template initiation. Qβ replicase may have an analogous “specificity pocket,” but since initiation occurs opposite the 3′-penultimate nucleotide, there would be no need for the template to ratchet back. For internal initiation, low-specificity contacts to 3′-proximal nucleotides could provide sufficient binding stabilization so that only two C residues suffice. It is proposed that the “specificity pocket” of φ6 RdRp can swivel aside to provide a path for the template that has already been read to feed through (11), and a similar scheme for Qβ replicase could pertain to internal initiation.

Can an accessible 3′-CCCA be a sufficiently restrictive prescription for specific viral amplification in vivo?: the role of replicase binding sites.

Our studies described above defined a good template for end-to-end transcription by Qβ replicase as one possessing a 3′-CCCA and lacking CC(A/G) immediately upstream. Such a sequence will appear at the 3′ end of an RNA with a probability of ca. 1 in 264. This rather modest specificity is increased to a degree that cannot be quantitated by the requirement that the 3′-CCCA be accessible. Until in vivo experiments with decoy RNAs are conducted, we cannot judge whether the transcription dependent on a CCCA initiation box that we have described in this study is sufficiently specific for viable viral replication. However, because endogenous decoy RNAs that could serve as nonproductive templates will do so in proportion to their concentration in the cell, we have perused the range of stable, abundant E. coli RNAs for the presence of a 3′-CCCA. This sequence is found only in tRNAHis, which was demonstrated in Fig. 6 to be a poor template because of the proximity of the 3′-initiation box to a base-paired helix. tRNAHis should thus only be used to a limited degree as a template by Qβ replicase in vivo, and perhaps in practice not at all, considering that tRNAs are typically engaged in interactions with aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, EF-Tu, or the ribosome.

A viable variant of Qβ RNA with a 3′-UCCA has been reported (28), and we have confirmed that Qβ replicase can effectively initiate transcription from this sequence, at least when juxtaposed next to a CCU upstream sequence (Fig. 7). Among the stable RNAs of E. coli, a 3′-UCCA terminus is only present in tRNACys (CCUCCA) and tRNAGly (GCUCCA; underlined nucleotides are base paired). Based on the template activity of tRNAHis-Δ5′G (Fig. 6, lane 3), which also has a 4-nt non-base-paired 3′ end, these tRNAs should not be efficient templates.

While the above considerations suggest that transcriptional control solely by a 3′-initiation box may be feasible, this idea will certainly need to be tested experimentally. Specificity could be readily augmented with cis-acting elements that bind replicase, and such elements have been reported in the Qβ system: the M and S sites of Qβ positive-strand RNA (6) and short RNA sequences that were selected from random sequences by sequential in vitro binding (site I and II ligands that are bound by the S1 and EF-Tu subunits, respectively, of Qβ replicase [8]). Such binding sites could be of benefit in ensuring that replicase will preferentially interact with viral RNAs in its search for a template, limiting its interaction with other cellular RNAs. They could also be beneficial as promoters or enhancers, augmenting the transcriptional strength provided by the initiation boxes described here. No experiments have yet tested the contribution of replicase binding sites to the specific transcription or replication of Qβ RNA in vivo. It should also be remembered that other features in addition to an appropriate initiation site need to be provided in a successful replicon. One example is a high degree of secondary structure as has been shown necessary for Qβ replicons in vivo (1) and which has been interpreted to permit positive and negative strands to remain separate and to provide protection against RNases.

Three Qβ replicase binding sites have been implicated in providing transcriptional strength through in vitro transcription studies: the M site in Qβ positive-strand RNA (29) and the site I and II ligand RNAs (8). However, some observations suggest that cis-acting sites that tightly bind replicase do not enhance transcription or are not needed in RNAs with an accessible initiation box. First, as reported in Table 1, we observe comparably strong transcription from templates comprised of a 3′-CCCA initiation box coupled to A-rich sequences that are not tightly bound by Qβ replicase (6) as from the amplifiable RNA DN3. Second, we observed no improvement in the transcription of an RNA similar to CCA9 when the site II ligand sequence was appended to its 5′ end (39). Third, no cis-acting sites common to the various RNAs amplifiable by Qβ replicase have yet been discerned, although there is evidence that the so-called site II on the EF-Tu subunit is able to accommodate a rather wide range of single- and double-stranded pyrimidine-rich sequences (23). While such site II binding may allow a range of RNAs to bind the replicase, the loose specificity could render this site ineffective in discriminating against nontemplate RNAs in the cell. The clear requirement for M-site sequences (29) is a peculiarity of Qβ positive-strand RNA that likely relates to the regulated access of the replicase to an 3′-initiation site that is deliberately inaccessible in its default state (due to base pairing). It has already been convincingly shown that the S site functions in the regulation of translation and not transcription (34).

cis-Acting signals that function as replicase binding sites offer the appealing mechanistic view that productive transcription occurs after templates attract replicase molecules to the vicinity of the active site. On the other hand, transcriptional control by kinetic as distinct from binding discrimination has been well documented in at least two examples (16, 35) and could be the way in which the “accessibility” of the 3′-initiation box contributes to initiation discrimination by Qβ replicase. Indeed, such specificity control was suggested by Blumenthal (5), based on the observation that template specificity can be overcome by altering Mn2+, glycerol, and GTP concentrations, and that weak templates required higher GTP concentrations for initiation. One can imagine that the half-life of an initiation site poised in the active site awaiting initial phosphodiester bond formation will vary depending on the surrounding sequence and the tendency for the initiation site vicinity to participate in base pairing and folding. A tendency to fold will antagonize active site binding, and bond formation will only occur rapidly when the GTP concentration is high enough to ensure that the first two GTPs are present in the active site whenever the unfavored, unfolded conformation of the initiation site enters the enzyme active site.

Further experiments are needed to examine the contribution of the transcription control mechanisms discussed above to RNA synthesis by Qβ replicase. A biological system likely benefits from the use of diverse mechanisms, and transcription may be controlled by both replicase binding and kinetic control strategies. Nevertheless, the experiments presented in this study make a strong case that transcription by Qβ replicase is heavily dependent on control by 3′-CCCA (or closely related) initiation boxes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Michael Farrell of Vysis, Inc., for the generous gift of Qβ replicase.

This work was supported by NIH grant GM54610.

Footnotes

Technical report 11771 of the Oregon Agricultural Experiment Station.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arora R, Priano C C, Jacobson A B, Mills D R. cis-Acting elements within an RNA coliphage genome: fold as you please, but fold you must! J Mol Biol. 1996;258:433–446. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avota E, Berzins V, Grens E, Vishnevsky Y, Luce R, Biebricher C K. The natural 6S RNA found in Qβ-infected cells is derived from host and phage RNA. J Mol Biol. 1998;276:7–17. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beekwilder M J, Nieuwenhuizen R, van Duin J. Secondary structure model for the last two domains of single-stranded RNA phage Qβ. J Mol Biol. 1995;247:903–917. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biebricher C K, Luce R. Sequence analysis of RNA species synthesized by Qβ replicase without template. Biochemistry. 1993;32:4848–4854. doi: 10.1021/bi00069a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blumenthal T. Qβ replicase template specificity: different templates require different GTP concentrations for initiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:2601–2605. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blumenthal T, Carmichael G G. RNA replication: function and structure of Qβ replicase. Annu Rev Biochem. 1979;48:525–548. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.48.070179.002521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown D, Gold L. Selection and characterization of RNAs replicated by Qβ replicase. Biochemistry. 1995;34:14775–14782. doi: 10.1021/bi00045a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown D, Gold L. RNA replication by Qβ replicase: a working model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11558–11562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buck K W. Comparison of the replication of positive-stranded RNA viruses of plants and animals. Adv Virus Res. 1996;47:159–251. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60736-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burg J L, Cahill P B, Kutter M, Stefano J E, Mahan D E. Real-time fluorescence detection of RNA amplified by Qβ replicase. Anal Biochem. 1995;230:263–272. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butcher S J, Grimes J M, Makeyev E V, Bamford D H, Stuart D I. A mechanism for initiating RNA-dependent RNA polymerization. Nature. 2001;410:235–240. doi: 10.1038/35065653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapman M R, Kao C C. A minimal RNA promoter for minus-strand RNA synthesis by the brome mosaic virus polymerase complex. J Mol Biol. 1999;286:709–720. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collmer C W, Kaper J M. Double-stranded RNAs of cucumber mosaic virus and its satellite contain an unpaired terminal guanosine: implications for replication. Virology. 1985;145:249–259. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90158-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deiman B A L M, Koenen A K, Verlaan P W G, Pleij C W A. Minimal template requirements for initiation of minus-strand synthesis in vitro by the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of turnip yellow mosaic virus. J Virol. 1998;72:3965–3972. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3965-3972.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feix G, Sano H. Initiation specificity of the poly(cytidylic acid)-dependent Qβ replicase activity. Eur J Biochem. 1975;58:59–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1975.tb02348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaal T, Bartlett M, Ross W, Turnbough C L, Jr, Gourse R. NTP concentration as a regulator of transcription initiation: control of rRNA synthesis in bacteria. Science. 1997;278:2092–2097. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5346.2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kao C, Zheng M, Rudisser S. A simple and efficient method to reduce nontemplated nucleotide addition at the 3′ terminus of RNAs transcribed by T7 RNA polymerase. RNA. 1999;5:1268–1272. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299991033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Küppers B, Sumper M. Minimal requirements for template recognition by bacteriophage Qβ replicase: approach to general RNA-dependent RNA synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:2640–2643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.7.2640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mills D R, Kramer F R, Spiegelman S. Complete nucleotide sequence of a replicating RNA molecule. Science. 1973;180:916–927. doi: 10.1126/science.180.4089.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moody M D, Burg J L, DiFrancesco R, Lovern D, Stanick W, Lin-Goerke J, Mahdavi K, Wu Y, Farrell M P. Evolution of host cell RNA into efficient template RNA by Qβ replicase: the origin of RNA in untemplated reactions. Biochemistry. 1994;33:13836–13847. doi: 10.1021/bi00250a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munishkin A V, Voronin L A, Chetverin A B. An in vivo recombinant RNA capable of autocatalytic synthesis by Qβ replicase. Nature. 1988;333:473–475. doi: 10.1038/333473a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishihara T, Mills D R, and Kramer F R. Localization of the Qβ replicase recognition site in MDV-1 RNA. J Biochem. 1983;93:669–674. doi: 10.1093/jb/93.3.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Preuss R, Dapprich J, Walter N G. Probing RNA-protein interactions using pyrene-labeled oligodeoxynucleotides: Qβ replicase efficiently binds small RNAs by recognizing pyrimidine residues. J Mol Biol. 1997;273:600–613. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Priano C, Kramer F R, Mills D R. Evolution of the RNA coliphages: the role of secondary structures during RNA replication. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1987;52:321–330. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1987.052.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rensing U, August J T. The 3′-terminus and the replication of phage RNA. Nature. 1969;224:853–856. doi: 10.1038/224853a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaffner W, Ruegg K J, Weissmann C. Nanovariant RNAs: nucleotide sequence and interaction with bacteriophage Qβ replicase. J Mol Biol. 1977;117:877–907. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(77)80004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schuppli D, Barrera I, Weber H. Identification of recognition elements on bacteriophage Qβ minus strand RNA that are essential for template activity with Qβ replicase. J Mol Biol. 1994;243:811–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schuppli D, Georgijevic J, Weber H. Synergism of mutations in bacteriophage Qβ RNA affecting host factor dependence of Qβ replicase. J Mol Biol. 2000;295:149–154. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schuppli D, Miranda G, Qiu S, Weber H. A branched stem-loop structure in the M-site of bacteriophage Qβ RNA is important for template recognition by Qβ replicase holoenzyme. J Mol Biol. 1998;283:585–593. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh R N, Dreher T W. Turnip yellow mosaic virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase: initiation of minus strand synthesis in vitro. Virology. 1997;233:430–439. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sivakumaran K, Kao C C. Initiation of genomic plus-strand RNA synthesis from DNA and RNA templates by a viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. J Virol. 1999;73:6415–6423. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6415-6423.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sprinzl M, Horn C, Brown M, Ioudovitch A, Steinberg S. Compilation of tRNA sequences and sequences of tRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:148–153. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.1.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trown P W, Meyer P L. Recognition of template RNA by Qβ polymerase: sequence at the 3′-terminus of Qβ 6S RNA. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1973;154:250–262. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(73)90055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Duin J. Single-stranded RNA bacteriophages. In: Calendar R, editor. The bacteriophages. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1988. pp. 117–167. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Villemain J, Guajardo R, Sousa R. Role of open complex instability in kinetic promoter selection by bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol. 1997;273:958–977. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weber H, Weissmann C. The 3′-termini of bacteriophage Qβ plus and minus strands. J Mol Biol. 1970;51:215–224. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90138-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wengler G, Wengler G, Gross H S. Replicative form of Semliki Forest virus RNA contains an unpaired guanosine. Nature. 1979;282:754–756. doi: 10.1038/282754a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoshinari S, Dreher T W. Internal and 3′ RNA initiation by Qβ replicase directed by CCA boxes. Virology. 2000;271:363–370. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoshinari S, Nagy P D, Simon A E, Dreher T W. CCA initiation boxes without unique promoter elements support in vitro transcription by three viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases. RNA. 2000;6:698–707. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200992410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zamora H, Luce R, Biebricher C K. Design of artificial short-chained RNA species that are replicated by Qβ replicase. Biochemistry. 1995;34:1261–1266. doi: 10.1021/bi00004a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]