Abstract

Background

Violence against people with intellectual disabilities is unfortunately a reality all over the world, as they are one of the populations most vulnerable to various forms of aggression. Assertive prevention and control measures are crucial to tackle and reduce this problem. The aim of this study was to map and summarize the main measures for preventing and controlling domestic violence against people with intellectual disabilities.

Methods

This was a scoping review conducted in accordance with the JBI guidelines. The databases consulted were: National Library of Medicine (PubMed); Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Web of Science; Excerpta Medica DataBASE (EMBASE); Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS) and SCOPUS. Studies included in this review reported on strategies to address domestic violence against people with intellectual disabilities, published in the last ten years, in Portuguese, Spanish or English.

Results

A total of 11 studies were included in this review. Six studies had high methodological quality and five had moderate. Cognitive-behavioral intervention programs, educational technologies and/or auxiliary tools, along with the full participation of people with intellectual disabilities in domestic violence prevention measures are appropriate strategies for dealing with this issue.

Conclusion

Domestic violence against people with intellectual disabilities is relatively unexplored in the health-field scientific literature. Prevention and control measures should be developed with the active involvement of people with intellectual disabilities, generating engagement and knowledge. Preventive measures should be adapted to the personal context and conditions of individuals with special needs, such as those with persistent or chronic mental disorders.

Keywords: Intellectual disability, Violence, Public Health, Domestic violence, Prevention and control

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines interpersonal violence as the intentional use of physical force or threats against oneself, another person, or a group or community, resulting in injury, psychological harm, deprivation or death [1]. It can be physical, sexual, psychological or neglectful [1, 2]. Everyone can be exposed to situations of violence throughout their life cycle. However, researchers have shown that some populations are more vulnerable to violence, such as women, children and the elderly, brown and black people, homosexuals, bisexuals, and transgender people, and people with disabilities, especially those with intellectual disabilities [2, 3].

Intellectual disability is characterized by significant limitations in intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior, covering conceptual, social and practical skills. This condition typically manifests itself before the age of 18 and affects the individual’s ability to perform daily activities independently. The causes can vary, including genetic factors, complications during pregnancy or childbirth, illness and trauma. Intellectual disability can range from mild to severe, impacting people’s lives in different ways.

Issues related to daily care demands, poor communication, insufficient employment or income, prejudice and discrimination increase the chances of violence against people with intellectual disabilities [4, 5]. Social isolation and limited support networks also increase vulnerability to violence, while negative perceptions and discrimination can create environments where violence is more likely and less recognized [5].

Violence against people with intellectual disabilities encompasses various forms, including physical violence (e.g., beatings or inappropriate restraints), emotional violence (e.g., intimidation, humiliation, and threats), sexual violence (often exacerbated by the victim’s difficulty in reporting abuse), and neglect (e.g., inadequate care regarding food, hygiene, health, and safety) [6, 7].

Violence against people with intellectual disabilities often occurs within the family, where the relationship of trust and power facilitates abuse. Parents, siblings, spouses, and other close relatives are the main aggressors, taking advantage of the victim’s dependency. However, caregivers, intimate partners and even acquaintances can perpetrate this type of violence, either because they have access to the victim in situations of vulnerability or because they exercise some kind of power over them [8]. Other less frequent perpetrators can be friends and acquaintances of the victim, such as neighbors and, although uncommon, strangers can also perpetrate violence against people with intellectual disabilities, but usually in situations of neglect by family members or guardians where the victim is left alone or without adequate supervision [8, 9].

The consequences of domestic violence against people with intellectual disabilities tend to be widespread and persistent, resulting in deep physical and psychological trauma, loss of trust, intense isolation and, in extreme cases, even death [10].

Studies suggest that violence prevention programs can effectively reduce victimization across the general population, as well as in more vulnerable groups, such as individuals with disabilities [9, 11]. Searches on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) and Open Science Framework (OSF) platforms found no records of systematic reviews and/or scoping reviews on successful measures to prevent and control domestic violence against people with intellectual disabilities, indicating a possible knowledge gap. Thus, this study is relevant as it compiles evidence to support effective intersectoral practices and public policies aimed at preventing and controlling violence. Finally, the aim of this study was to map and summarize the main measures for preventing and controlling domestic violence against people with intellectual disabilities.

Methods

Design, period and place of study

This study employed a scoping review methodology, following the JBI recommendations [12]. The research protocol was registered with the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/bhrmj/).

Data was collected between August and September 2023. The following databases were searched: National Library of Medicine (PubMed); Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Web of Science (WOS); Excerpta Medica DataBASE (EMBASE); Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS) and SCOPUS. Additional studies were identified through reference lists of primary articles.

The review included studies that reported on strategies for addressing domestic violence against individuals with intellectual disabilities, published in the last ten years (2014–2024), in Portuguese, Spanish or English. Editorials, reviews, response letters and event summaries were excluded. The authors selected this timeframe to ensure the inclusion of the most current measures for preventing and managing domestic violence within this population, avoiding outdated strategies that may not be applicable to the current socio-historical context. The level of evidence was not considered as an exclusion criterion.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-SCR): Checklist and Explanation [13] was used to construct the research report.

Study protocol

To develop the review question, the phases described by the JBI were followed. These phases included identifying the question, searching for relevant studies, selecting studies, extracting data, grouping, summarizing, and presenting the results.

The PCC [Population, Concept and Context] framework was used to formulate the research problem, with the following representations: P = domestic violence, C = people with intellectual disabilities and C = control and prevention measures. This led to the research question: “What is the main evidence available on prevention and control measures for domestic violence against people with intellectual disabilities?

The data search used a combination of the following descriptors in Portuguese: “Pessoa com deficiência intelectual”, “Vigilância em saúde”, “Violência doméstica”, and “Violência”. The descriptors in English were: “Person with Intellectual Disability”, " Health Surveillance”, " Domestic Violence”, and “Violence”. These descriptors were combined in various ways to broaden the search, as well as using terminological variations and synonyms in the languages listed.

The aforementioned descriptors were combined using the Boolean operators AND (restrictive combination) and OR (additive combination). OR was used between keywords within the same PCC component, while AND was used to combine different components, as shown in Table 1. The search terms used in this systematic review were obtained by consulting the Health Sciences Descriptors (DeCS).

Table 1.

Database search strategies, São Paulo, São Paulo, 2024

| Database | Search strategy |

|---|---|

| PubMed* |

(“domestic violence” OR “violence/psychology” OR “spouse abuse”) AND (“intellectual disability” OR “disabled persons” OR “persons with mental disabilities” AND “prevention and control”) OR (“prevention” AND “control” OR “prevention and control” “community mental health services) |

| LILACS** | domestic violence AND people with disabilities |

| CINAHL*** | (intellectual disability or mental retardation or learning disability OR developmental disability ) AND (interpersonal violence OR intimate partner violence OR domestic violence ) AND (prevention OR reduction OR minimize OR health promotion OR community mental health service ) |

| EMBASE | (‘intellectual impairment OR ‘intellectual disability’ OR ‘intellectual dysfunction’ OR ‘people with disabilities’ OR cognitive retard’ OR ‘deficiency, mental’ OR ‘incapacity, mental’ OR ‘mental handicap’ OR ‘mental ‘psychosocial |

| Web of Science | (“intellectual disability” OR “mental retardation” OR “learning disability” OR " AND (“interpersonal violence” OR “intimate partner violence” OR “domestic violence” OR violence or abuse) |

| SCOPUS | (“intellectual disability” OR “mental retardation” or “learning disability” OR “developmental disability” OR “learning disabilities”) AND (“interpersonal violence” OR “intimate partner violence” OR “domestic violence” OR violence OR abuse) |

*National Library of Medicine

**Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature

***Cummulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

Ethical aspects

National and international legislation was respected. As the research did not involve direct contact with human beings or animals, it was not necessary to submit the study for approval by a Research Ethics Committee.

Analysis of results

Data collection was based on the following variables: title, authors, year of publication and journal, country, language, objectives, design and main results.

The methodological quality and risk of bias of the selected studies were assessed using the JBI Appraisal Tools [14]. The results were analyzed descriptively, and summaries of the included studies were provided.

Results

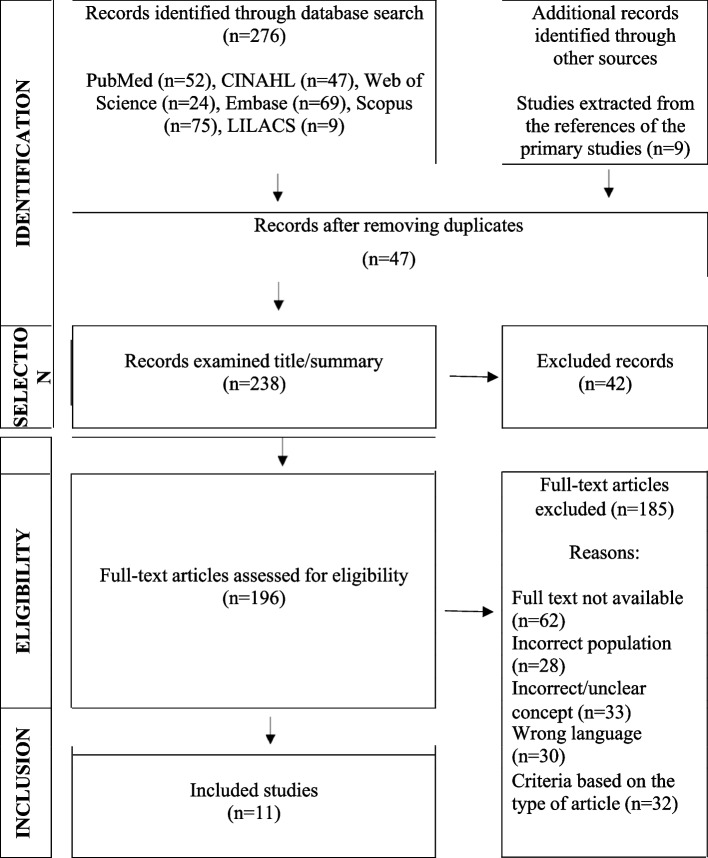

A total of 276 articles were initially identified from primary sources; nine articles were added through reference lists. After removing duplicates, the titles and abstracts of the remaining articles were reviewed, resulting in the exclusion of 42 articles at this stage. Upon full-text review, 185 articles were found to meet the exclusion criteria. Consequently, the final selection comprised 11 articles. The flowchart in Fig. 1 illustrates the article selection process.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart according to the criteria of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA- SCR), according to the JBI, Brazil, 2024

Among the studies included, the majority were published in English (n = 9; 81.8%) and Portuguese (n = 2; 18.2%), conducted in Australia (n = 1; 9%), the United Kingdom (n = 1; 9%), the Netherlands (n = 2; 18.2%), Greece (n = 1; 9%), Spain (n = 1; 9%), the United States (n = 2; 18.2%) and Brazil (n = 2; 18.2%). The methodologies encountered varied from reviews (n = 4; 36,4%), qualitative studies (n = 2; 18,2%), quasi-experiments (n = 2; 18,2%), technological validation (n = 1; 9%), cohort (n = 1; 9%) and case study (n = 1; 9%) published between 2018 and 2023. A summary of the selected articles is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of selected materials. São Paulo, São Paulo, 2024

| Year/ Country | Authors/ Title | Objective | Study design sample/ scenario | Outcomes | Methodological quality** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2023 Australia |

Saleme P et al [15]. An Integrative Literature Review of Interventions to Protect People with Disabilities from Domestic and Family Violence |

To systematically synthesize the evidence and effectiveness of intervention strategies to increase the awareness and skills of people with intellectual disabilities to reduce domestic violence. |

Review Sample: 17 studies Scenery: n/a* |

The strategies found focused on training and educating people with intellectual disabilities themselves, creating channels and physical facilities for victims to seek help. The majority showed positive results with a reduction in domestic violence. | High |

|

2022 United Kingdom |

Quinn S et al [16]. Risk for intellectual disability populations in inpatient forensic settings in the United Kingdom: A literature review |

Mapping and evaluating academic evidence on the concept of risk in the context of UK forensic services for patients with intellectual disabilities |

Review Sample: 22 articles Scenery: n/a* |

The results suggest that restrictive measures to decrease the forensic risk of violence can exacerbate the risk of health and well-being problems. There was limited evidence of direct involvement of the person with an intellectual disability in risk assessment and management. | Moderate |

|

2021 Brazil |

Nobrega KBG et al [17]. Validation of the educational technology "abuse won't happen" for girls with intellectual disabilities |

To validate, with expert judges, an educational technology aimed at preventing sexual abuse among young women with disabilities. intellectual disability. |

Technological validation Sample: 25 judges Scenery: n/a* |

The educational technology was validated by the judges with a Total Content Validation Index of 0.99. The judges pointed out that the technology contributes to the emancipation of people with intellectual disabilities, promotes rights, encourages sex education and prevents sexual abuse. | High |

|

2021 The Netherlands |

Ooms-Evers M et al [9]. Intensive clinical trauma treatment for children and adolescents with mild intellectual disability or borderline intellectual functioning: A pilot study |

Investigate the feasibility, safety and potential efficacy of treatment in children and adolescents with Mild Intellectual Disability or borderline intellectual functioning and trauma-related symptoms as a result of adverse childhood experiences or Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. |

Quasi-experiment Sample: 33 children (6 – 17 years old) Setting: outpatient clinic |

The treatment consisted of a daily program of prolonged exposure (average 8.4 days) which included desensitization and cognitive processing of traumas. There was a reduction in emotional and behavioral problems after treatment. Post-traumatic Stress Disorder scores decreased from 24 to 8 points at the end of treatment, including situations of moderate aggression. | Moderate |

|

2020 Brazil |

Oliveira GC et al [18]. Prolonged institutionalization, mental disorders and violence: a scientific review on the subject. |

A review of the scientific literature on violence, mental disorders and institutionalization. |

Review Sample: 59 articles Scenery: n/a* |

The identification of risk factors associated with violent behavior is fundamental in order to achieve an adequate assessment in relation to to mental illness, without referring strictly to the hospitalization/institutionalization model prolonged, archaic and stigmatizing, when seen as the only alternative. |

High |

|

2020 Australia |

Robinson S et al [19]. Feeling safe, avoiding harm: Safety priorities of children and young people with disabilities and high support needs |

To explore the conceptions of children and young people with disabilities about safety and violence. |

Qualitative Sample: 22 participants - children and young people (7 – 25 years old) Setting: outpatient clinic |

Children and young people with intellectual disabilities had greater barriers to accessing protection and safety environments than those with other types of disability. Strategies for minimizing risks, including violence, must be built with people with disabilities. | Moderate |

|

2019 United States of America |

Lofthouse RE et al [20]. Predicting aggression in adults with intellectual disability: A pilot study of the predictive efficacy of the Current Risk of Violence and the Short Dynamic Risk Scale |

To evaluate the effectiveness of predicting aggressors in adults with intellectual disabilities. |

Cohort Sample: 25 adults with intellectual disabilities Setting: outpatient clinic |

The instruments Current Risk of Violence and Short Dynamic Risk Scale were applied and were able to predict violent behavior (physical and verbal) in adults with intellectual disabilities. The use of these instruments can support professionals in using strategies to prevent violence and avoid retaliation in the home. | High |

|

2019 Greece |

Gkogkos G et al [21]. Sexual Education: A Case Study of an Adolescent with a Diagnosis of Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified and Intellectual Disability |

To report a case of behavior analytic intervention in an adolescent with intellectual disabilities and his guardian (father) on sexual behavior and reduction of sexual aggression. |

Case studies Sample: 01 Adolescent (15 years old) Setting: Hospital |

The professional intervention in the report had five objectives, including controlling an adolescent's sexual drive, which led to violent retaliation. The involvement of the guardian was fundamental in improving behavior and avoiding aggressive retaliation from victims and witnesses. The effects were temporary, and prolonged and/or continuous programs are recommended. | Moderate |

|

2019 Spain |

Gutiérrez-Bermejo et al [11]. Evidences of an Implemented Training Program in Consensual and Responsible Sexual Relations for People with Intellectual Disabilities. |

To implement and analyze an intervention program on sexual responsibility and rights for adults with intellectual disabilities. |

Almost experimental Sample: 44 adult people Setting: outpatient clinic |

Evidence of improvements obtained by adults with intellectual disabilities after participating in a program focused on training in sexual aspects (rights, health, self-determination, interpersonal relationships, risks, abuse). The program was effective in reducing sexual violence (either as victims or perpetrators). | High |

|

2019 The Netherlands |

Smit M et al [22]. Clinical characteristics of individuals with intellectual disability who have experienced sexual abuse. An overview of the literature |

To identify the clinical characteristics of individuals with intellectual disabilities who have experienced sexual abuse |

Review Sample: seven studies (children, young people and adults) Scenario: multiple |

The results suggest planning educational interventions and special, individualized attention for those with anxiety, depression and self-inflicted violence. | High |

|

2018 United States of America |

Hughes RB et al [23]. "I really want people to use our work to be safe"...Using participatory research to develop a safety intervention for adults with intellectual disability |

To identify the feasibility of a program to prevent interpersonal violence against people with intellectual disabilities. |

Qualitative Sample: ten adult people Setting: outpatient clinic |

A structured group cognitive-behavioral intervention program lasting eight sessions a week was considered feasible for implementing and reducing interpersonal violence against people with intellectual disabilities. The participation of people with intellectual disabilities in all stages of the project was seen as fundamental to ensuring the program's relevance, inclusion and accessibility. | Moderate |

*n/a- not applicable

**JBI Appraisal Tools

The JBI Appraisal Tools were used to assess the methodological quality of the selected articles, revealing that six studies were classified as high quality [9, 11, 15–19] with low risk of bias, while five were classified as moderate quality [8, 15, 17–19]. Due to the diverse methods employed across studies, it was not possible to accurately analyze the number of participants.

The strategies for preventing and controlling violence against people with intellectual disabilities were categorized based on their similarities into the following groups: I- cognitive-behavioral intervention programs [9, 11, 20, 21], II- educational technologies and auxiliary tools [16, 18], III- full participation of people with intellectual disabilities in domestic violence prevention measures [15–23] and IV- special considerations in situations of persistent mental disorders [17, 19].

The cognitive-behavioral intervention programs found were usually eight weeks long and included strategies such as group or individual activities (depending on specifics, such as the intense aggressive behavior or agitation of some participants), desensitization of violent experiences, retro-processing of traumas, training on sexual rights, interpersonal relationships, setting limits and identifying risks [9, 11, 20, 21]. Programs involving guardians or caregivers proved beneficial as it enhanced their awareness in daily care activities with people with intellectual disabilities. This involvement also facilitated the early identification of violence, as caregivers acted as protectors and were better able to address and prevent abusive situations [9, 20].

Educational technologies such as apps or games can be an important literacy tool for people with mild and moderate intellectual disabilities. They promote awareness of risks and the possibility of making quick decisions in a real or potential violent situation [16, 18]. Risk assessment tools like the Current Risk of Violence and the Short Dynamic Risk Scale, when presented in accessible language, can aid health professionals and caregivers to predict violent behavior in people with intellectual disabilities [18]. By using these tools, they can identify violent impulses, prevent retaliatory actions, and help break the cycle of violence.

Studies have shown the importance of the participation of people with intellectual disabilities in all the actions and strategies planned to control and prevent domestic violence. Their participation generates empowerment, knowledge about the subject and a greater sense of self-care. In addition, listening to their opinions and suggestions allows actions to be planned according to the relevance of the victim, not just from a health perspective, generating inclusion and accessibility [15–23].

However, two studies point out that there are special conditions in which the planning of prevention and control measures needs to be done with singularity [17, 19], since people with persistent mental disorders including depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation and psychotic disorders may not benefit from the standard cognitive-behavioral programs and educational technologies. While the focus should remain on the victims, educational measures for aggressors, especially those with persistent issues, are also emphasized.

A summary of the categories found and their main characteristics can be seen in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summaries of successful measures according to the categories found. São Paulo, São Paulo, 2024

| Category | Key characteristics/Results | Included references |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention Programs |

- Duration: ~8 weeks - Includes group/individual activities - Focus: desensitization, trauma processing, sexual rights training, boundary setting - Guardian/caregiver involvement beneficial |

[9, 11, 21, 23] |

| Educational Technologies and Auxiliary Tools |

- Tools: apps, games - Purpose: literacy for mild/moderate intellectual disabilities - Risk assessment tools: Current Risk of Violence, Short Dynamic Risk Scale - Supports quick decision-making and professional/caregiver support |

[17, 20] |

| Full Participation of People with Intellectual Disabilities |

- Empowers individuals - Promotes self-care - Ensures interventions are relevant to their needs - Fosters inclusion and accessibility |

[15, 16, 19] |

| Special Considerations for Persistent Mental Disorders |

- Tailored approaches needed - Standard programs/technologies may not be effective - Educational measures for aggressors are also important, especially persistent ones |

[18, 22] |

Discussion

Violence against people with intellectual disabilities presents a complex health challenge that requires a multifaceted approach for effective prevention and intervention. Effective prevention and intervention require education and awareness- raising among society and the victims themselves [21].

Structured intervention programs employing cognitive-behavioral techniques have shown promise in reducing violence risk and enhancing safety. Cognitive-behavioral techniques are interventions aimed directly at problems and are based on scientific methods from neuroscience. Some of the techniques mentioned included psychoeducation, recording dysfunctional thoughts, systematic desensitization, role-playing and distant observation. All of them enable people to find individual coping mechanisms for fear, anger, anxiety or even dealing with emergencies such as panic attacks [21–24]. American and South African research shows that short and medium-term programs can develop self-defense techniques and social skills [24, 25].

An Israeli study highlights that programs for preventing violence against people with intellectual disabilities are most effective when implemented by interdisciplinary teams. Such teams are equipped to adapt the programs to each participant’s unique capabilities and needs. This approach involves ongoing evaluations to ensure effectiveness and includes recommendations for personal safety workshops, abuse recognition training, and school interventions [26]. Tailoring these programs boosts participants’ self-confidence and contributes to a safer, more independent life. However, challenges remain, including the need for specialized resources and addressing the variability in cognitive abilities among participants and their guardians [26, 27].

Educational technologies and aids play a highly relevant role in violence prevention, offering innovative tools for education, awareness-raising and protection. Mobile apps can teach safety and self-defense skills, while online platforms can offer interactive modules on violence prevention, including virtual environments [28]. Research using virtual and augmented reality showed that safe simulations of risk situations and alternative communication software helped to communicate concerns and reports [29]. In addition, personal alert devices, monitoring systems, and adapted self-defense programs can increase emergency response capacity and promote autonomy. Despite these advances, limitations include high operating costs and language and access barriers, particularly for individuals with greater social vulnerability or severe intellectual disabilities [28, 29].

Australian researchers state that the participation of people with disabilities in domestic violence prevention and control actions and strategies is essential to ensure the effectiveness and appropriateness of these initiatives [30]. Involving the target population as advisors in the creation of policies and programs, incorporating their personal experiences into awareness campaigns, and involving their representation on policy-making committees and councils are ways of ensuring that their needs and experiences are taken into account. Specific education and training, using accessible materials, and the creation of support groups led by people with intellectual disabilities are also key. These groups provide a safe space to share experiences and develop protection strategies, as well as empowering participants [31].

Active participation of people with intellectual disabilities not only increases the relevance and effectiveness of interventions but also fosters social inclusion and challenges prejudices and stigmas. This inclusion empowers individuals, enhances their autonomy and self- confidence, and promotes a more inclusive and aware community [30, 31].

For individuals with both intellectual disabilities and persistent mental disorders – such as depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation – specialized planning is required due to their heightened vulnerability and complex needs. Mental disorders aggravate emotional and psychological sensitivity, making these people more susceptible to abuse and making it more difficult for them to communicate about their experiences of violence. Frequent social isolation limits their support networks, increasing their dependence on aggressors and their difficulty in seeking help [32]. In addition, integrating psychological, psychiatric, and social support is vital for providing holistic and continuous care tailored to individual needs.

Researchers cite that personalized interventions, which include emotional regulation techniques and self-care strategies, are crucial to help these people cope with abuse situations and prevent mental health deterioration. Creating safe and welcoming environments, along with ongoing training for caregivers and professionals, ensures an effective and empathetic response to their needs. Continuous mental health monitoring and the development of coping skills strengthen resilience and promote the protection and well-being of people with intellectual disabilities [32, 33].

In addition to the aspects mentioned above, it is essential that public policies are implemented to help reduce the vulnerability of people with intellectual disabilities, as successful measures include the sustainability of actions that can only be achieved through political engagement, as researchers in Sweden and Australia have pointed out [34, 35].

Limitations and contributions to the advancement of science

This study is not free from limitations. One key limitation is the selection of databases and languages, which may have excluded relevant studies published in other languages or indexed in less common databases. Another important limitation of this scoping review was the wide variety of methods found in the studies, making it challenging to directly compare or test specific strategies for preventing and controlling domestic violence against individuals with intellectual disabilities. Consequently, the review was limited to summarizing outcomes based on each study’s methodology.

Despite these limitations, the study makes significant contributions to the field. It brings visibility to the issue of domestic violence against individuals with intellectual disabilities and identifies potential measures with promising responses. Furthermore, it highlights the need for further intervention-focused research to develop and evaluate strategies in a more controlled and comparable manner.

Conclusion

This scoping review highlights that the issue of domestic violence against individuals with intellectual disabilities is a global concern, as evidenced by the diverse geographic locations of the publications reviewed. The findings suggest that the main measures to prevent and control domestic violence against people with intellectual disabilities include cognitive-behavioral intervention programs with victims and caregivers, which help to reduce situations of violence through early identification of risks.

The use of educational technologies (such as apps and games) and assessment tools also help professionals, caregivers and guardians to identify risks of violence against or from the person with a disability, with the potential for equally violent retaliation. However, it is noted that these measures may not be as effective for populations with major mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, psychosis and suicidal ideation, and that unique therapeutic projects with more frequent reassessments of effectiveness are needed.

The study’s broad methodological diversity highlights the need for more robust interventional and longitudinal research to identify the most effective long-term strategies.

The active participation of individuals with intellectual disabilities in the development and implementation of prevention and control measures is crucial. Their perspectives and experiences are essential for validating and refining interventions to ensure they address the specific needs and challenges faced by those most affected.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- WHO

World Health Organization

- PROSPERO

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

- OSF

Open Science Framework

- PubMed

National Library of Medicine

- CINAHL

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- EMBASE

Excerpta Medica DataBASE

- LILACS

Latin American and Caribbean Literature in Health Sciences

- WOS

Web of Science

- PRISMA- ScR

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews

- PCC

Population, Concept and Context

Authors' contributions

MTS, PH, MFPO, MT, DAB and HF conceptualized the review and design. MTS and HF conducted the review, data collection, and data analysis. MTS, PH, MFPO, MT, DAB and HF prepared the original draft of the manuscript. MTS, PH, MFPO, MT, DAB and HF contributed to revising and finalizing the manuscript by providing critical feedback to drafts. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Fundação Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior- Brazil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001.

Data availability

Data on the selected materials can be obtained from https://osf.io/bhrmj/. Additional information can also be requested from the authors.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

International ethical legislation was respected. There was no need for approval by a research ethics committee because the study was based on the analysis of articles published in scientific journals.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Injuries and violence. Geneva: WHO; 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/injuries-and-violence. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuran CHA, Morsut C, Kruke BI, Krüger M, Segnestam L, Orru K, et al. Vulnerability and vulnerable groups from an intersectionality perspective. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020;50:e101826. 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101826. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fernandes H, Bertini PVR, Hino P, Taminato M, Silva LCP, Adriani PA, Ranzani CM. Interpersonal violence against homosexual, bisexual and transgender people. Acta Paul Enferm. 2022;35:eAPE01486. 10.37689/acta-ape/2022AO0148666. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schalock RL, Luckasson R, Tassé MJ. An overview of intellectual disability: definition, diagnosis, classification, and systems of supports. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2021;26(6):439–42. 10.1352/1944-7558-126.6.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibbs V, Hudson J, Hwang YI, Arnold S, Trollor J, Pellicano E. Experiences of physical and sexual violence as reported by autistic adults without intellectual disability: rate, gender patterns and clinical correlates. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2021;89:e101866. 10.1016/j.rasd.2021.101866. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willot S, Badger W, Evans. People with an intellectual disability: under-reporting sexual violence. J Adult Prot. 2020;22(2):75–86. 10.1108/JAP-05-2019-0016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fanslow JL, Malihi ZA, Hashemi L, Gulliver PJ, McIntosh TKD. Lifetime prevalence of intimate partner violence and disability: results from a population-based study in New Zealand. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61(3):320–8. 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmer SJ, Dvir Y. Trauma and psychosocial adversity in youth with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. Front Psychiatry. 2024;15:e1322056. 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1322056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ooms-Evers M, Graaf-Loman S, Duijvenbode N, Mevissen L, Didden R. Intensive clinical trauma treatment for children and adolescents with mild intellectual disability or borderline intellectual functioning: a pilot study. Res Dev Disabil. 2021;117:e104030. 10.1016/j.ridd.2021.104030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirvikoski T, Boman M, Tideman M, Lichtenstein P, Butwicka A. Association of Intellectual Disability with all-Cause and cause-specific mortality in Sweden. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2113014. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutiérrez-Bermejo B, Flores N, Amor PJ, Jenaro C. Evidences of an implemented training program in consensual and responsible sexual relations for people with intellectual disabilities. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(5):2323. 10.3390/ijerph18052323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khalin HB, Bennett M, Godfrey C, Mclnerney P, Munn Z, Peters M. Evaluation of the JBI scoping reviews methodology by current users. Int J Evidence-Based Healthc. 2020;18(1):95–100. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Critical Appraisal Tools. Joanna Briggs Institute. Available from: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools/.

- 15.Saleme P, Seydel T, Pang B, Deshpande S, Parkinson J. An Integrative Literature Review of Interventions to protect people with disabilities from domestic and family violence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(3):e2145. 10.3390/ijerph20032145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quinn S, Rhinas S, Gowland S, Cameron L, Braid N, Connor SO. Risk for intellectual disability populations in inpatient forensic settings inthe United Kingdom: a literature review. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2022;35(6):1267–80. 10.1111/jar.13030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nóbrega KBG, Marinus MWLC, Belian RB, Gontijo DT. Validation of the educational technology “abuse no more” for young people with intellectual disabilities. Ciênc Saúde Colet. 2021;26(7):2793–806. 10.1590/1413-81232021267.09032021 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oliveira GC, Valença AM. Prolonged institutionalization, mental disorders and violence: a scientific review on the topic. Saude soc. 2020;29(4): e190681. 10.1590/S0104-12902020190681.

- 19.Robinson S, Graha A. Feelingsafe, avoiding harm: Safety priorities of children and young people withdisability and high support needs. J Intelect Disabil. 2021;25(4):583–602. 10.1177/1744629520917496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lofthouse RE, Golding L, Totsika V, Hastings R, Lindsay WR. Predicting aggression in adults with intellectual disability: a pilot study of the predictive efficacy of the current risk of violence and the short dynamic risk scale. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2020;33(4):702–10. 10.1111/jar.12665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gkogkos G, Staveri M, Galanis P, Gena A. Sexual education: a case study of an adolescent with a diagnosis of pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified and intellectual disability. 2019;39:439-453. 10.1007/s11195-019-09594-3.

- 22.Smit M, Scheffers M, Emck C, Busschbach JT, Beek P. Clinical characteristics of individuals with intellectual disability who have experienced sexual abuse. An overview of the literature. Res Dev Disabil. 2019;95:e103513. 10.1016/j.ridd.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes RB, Robinson-Whelen S, Goe R, Schwartz M, Cesal L, Garner KB, et al. “I really want people to use our work to be safe”...Using participatory research to develop a safety intervention for adults with intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil. 2020;24(3):309–25. 10.1177/1744629518793466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lund EM. Single-Session intervention for abuse awareness among people with developmental disabilities. Sex Disabil. 2014;32:99–105. 10.1007/s11195-013-9335-3. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chirwa E, Jewkes R, Heijden I, Dunkle K. Intimate partner violence among women with and without disabilities: a pooled analysis of baseline data from seven violence- prevention programs. BMJ Global Health. 2020;5:e002156. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karni N. Effectiveness of an intervention on verbal violence among students with intellectual disabilities. Int J Secondary Educ. 2014;2(5):87–93. 10.11648/j.ijsedu.20140205.11. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ray I, Simpson AIF, Jones RM, Shatokhina K, Trakur A, Mulsant BH. Clinical, demographic, and criminal behavior characteristics of patients with intellectual disabilities in a Canadian forensic program. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:e00760. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magalhães BC, Silva MMO, Silva CF, Alcântara PPT, Oliveira CAN, Araújo MM, et al. EMPODEREENF: construction of an application for nurses’ continuing education on psychological violence against women. Rev Bras Enferm. 2022;75(5):e20200391. 10.1590/0034-7167-2020-0391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xue J, Hu R, Zhang W, Zhao Y, Zhang B, Liu N, Li SC, Logan J. Virtual reality or augmented reality as a Tool for studying bystander behaviors in interpersonal violence. Scoping Rev J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(2):e25322. 10.2196/25322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Araten-BergmanT, Bigby C. Violence prevention strategies for people with intellectual disabilities: a scoping review. Aust Soc Work. 2020;76(1):72–87. 10.1080/0312407X.2020.1777315. [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGilloway C, Smith D, Galvin R. Barriers faced by adults with intellectual disabilities who experience sexual assault: a systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2018;33(1):51–66. 10.1111/jar.12445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silva MT, Fontoura AVB, Pires ANG, Carvalheira APP, Hino P, Okuno MFP, Taminato M, Caldas JMP, et al. Interpersonal violence against people with intellectual disabilities in São Paulo, Brazil: characteristics of victims, perpetrators and referrals. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:e1797. 10.1186/s12889-024-19211-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gomes CMS, Schiavo KV, Nascimento APC, de Macedo MDC. Meeting of powerful women: social occupational therapy intervention strategy with informal caregivers of people with intellectual disabilities. Cad Bras Ter Ocup. 2023;31(spe):e3402. 10.1590/2526-8910.ctoAO260834021. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Starke M, Larsson A, Punzi E. People with intellectual disability and their risk of exposure to violence: identification and prevention – a literature review. J Intellect Disabil. 2024;1–24. 10.1177/17446295241252472. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Davy L, Robinson S, Idle J, Valentine K. Regulating vulnerability: policy approaches for preventing violence and abuse of people with disability in Australian service provision settings. Disabil Soc. 2024;e2323456. 10.1080/09687599.2024.2323456.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data on the selected materials can be obtained from https://osf.io/bhrmj/. Additional information can also be requested from the authors.