Summary

Background

Mouse models that recapitulate key features of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection are important tools for understanding complex interactions between host genetics, immune responses, and SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. Little is known about how predominantly cellular (Th1 type) versus humoral (Th2 type) immune responses influence SARS-CoV-2 dynamics, including infectivity and disease course.

Methods

We generated knock-in (KI) mice expressing human ACE2 (hACE2) and/or human TMPRSS2 (hTMPRSS2) on Th1-biased (C57BL/6; B6) and Th2-biased (BALB/c) genetic backgrounds. Mice were infected intranasally with SARS-CoV-2 Delta (B.1.617.2) or Omicron BA.1 (B.1.1.529) variants, followed by assessment of disease course, respiratory tract infection, lung histopathology, and humoral and cellular immune responses.

Findings

In both B6 and BALB/c mice, hACE2 expression was required for infection of the lungs with Delta, but not Omicron BA.1. Disease severity was greater in Omicron BA.1-infected hTMPRSS2-KI and double-KI BALB/c mice compared with B6 mice, and in Delta-infected double-KI B6 and BALB/c mice compared with hACE2-KI mice. hACE2-KI B6 mice developed more severe lung pathology and more robust SARS-CoV-2-specific splenic CD8 T cell responses compared with hACE2-KI BALB/c mice. There were no notable differences between the two genetic backgrounds in plasma cell, germinal center B cell, or antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2.

Interpretation

SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron BA.1 infection, disease course, and CD8 T cell response are influenced by the host genetic background. These humanized mice hold promise as important tools for investigating the mechanisms underlying the heterogeneity of SARS-CoV-2-induced pathogenesis and immune response.

Funding

This work was funded by NIH U19 AI142790-02S1, the GHR Foundation, the Arvin Gottleib Foundation, and the Overton family (to SS and EOS); Prebys Foundation (to SS); NIH R44 AI157900 (to KJ); and by an American Association of Immunologists Career Reentry Fellowship (FASB).

Keywords: Mouse model, Delta, Omicron BA.1, CD8 T cells, CD4 T cells, B cells, hACE2, hTMPRSS2, C57BL/6, BALB/c

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Existing humanized mouse models of SARS-CoV-2 infection are constructed in the Th1-dominant C57BL/6 genetic background and, except for K18-hACE2 mice, these models generally exhibit mild symptoms upon viral infection. The Th2-dominant BALB/c background is considered a superior strain for modeling severe respiratory disease manifestations, and accumulating evidence indicates that mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2-induced pathogenesis differs in C57BL/6 versus BALB/c mice. Therefore, we generated humanized mouse strains expressing hACE2 and/or hTMPRSS2 on both C57BL/6 and BALB/c backgrounds.

Added value of this study

Our results show that SARS-CoV-2 elicits greater lung pathology and CD8 T cell responses in hACE2-knock-in mice in the C57BL/6 genetic background as compared with BALB/c. Thus, hACE2-and/or hTMPRSS2-knock-in C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice represent valuable tools for modeling the heterogeneity of SARS-CoV-2-induced disease and immune responses in the context of differing host genetics and MHC haplotypes.

Implications of all the available evidence

Investigation of the mechanisms of pathogenesis and immune responses in hACE2-and/or hTMPRSS2-knock-in mice in both C57BL/6 and BALB/c genetic backgrounds will aid development of new vaccines and therapeutics against future SARS-CoV-2 variants and novel coronaviruses.

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-19, was originally identified in late 2019.1 Since then, variants have emerged with greater transmissibility, pathogenicity, and/or immune escape characteristics,2 making it likely that acute and long COVID-19 will remain global health concerns for the foreseeable future. Thus, there remains an important need for next-generation vaccines and therapeutics to prevent and treat disease caused by contemporaneous and future SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Development of effective therapeutics requires preclinical mechanistic studies of how infection with different SARS-CoV-2 variants (ancestral and contemporaneous) shapes the immune response, and vice versa. Such studies have been hampered by the inability of ancestral SARS-CoV-2 to infect the lower respiratory tract of wild-type (WT) mice.3 One successful strategy to overcome this problem has been to engineer mice to express human angiotensin-converting enzyme (hACE2), the primary binding receptor of SARS-CoV-2, and/or human transmembrane serine protease 2 (hTMPRSS2), the co-factor for SARS-CoV-2.4,5 In humans, the primary mode of cell entry for ancestral SARS-CoV-2 is via binding between the viral spike (S) protein subunit S1 and hACE2, followed by TMPRSS2-mediated cleavage/activation of the S2 subunit and direct fusion to the cell membrane.4 However, recent SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern, including Omicron BA.1, appear to be less dependent on human TMPRSS2 and may use endosomal cysteine proteases for S protein priming and entry into cells.6, 7, 8, 9, 10

Studies in hACE2/hTMPRSS2 mice and other models have greatly increased our understanding of SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis and facilitated the development and testing of vaccines and therapeutic candidates.11,12 However, the most commonly utilized mouse model of infection, K18-hACE2, expresses high levels (up to 8 copies) of hACE2 under the direction of the K18 promoter, and is susceptible to death due to encephalitis.13 Aspects of the immune response that could profoundly impact SARS-CoV-2-elicited immune responses and pathology have not yet been investigated in physiologically representative mouse models. For example, decades of research have shown that the genetic background of humans and mice strongly biases cellular immune responses, such as polarization of naïve CD4 T cells towards differentiation into T helper 1 (Th1) or Th2 subsets, each of which have distinct effector roles.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 While strong Th1 cellular responses are essential to defend against intracellular pathogens such as viruses, Th2 responses promote humoral immunity and are most commonly associated with protection against parasites as well as responses to allergens.20,21 Human studies have shown that the clinical outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection is affected by host genetics22,23 and Th1 versus Th2 responses24,25; in particular, genomic and proteomic studies of COVID-19 patient samples suggest that Th1-biased and Th2-biased T cell responses tend to be protective and pathogenic, respectively.23, 24, 25

In the present study, we evaluated the influence of genetic background and Th cell bias on SARS-CoV-2 infection and pathogenesis by generating single-knock-in (KI) or double-KI (DKI) mice expressing hACE2 alone, hTMPRSS2 alone, or both hACE2 and hTMPRSS2, on two mouse genetic backgrounds that favor Th1-biased (C57BL/6, hereafter referred to as B6) or Th2-biased (BALB/c) CD4 T cell responses. We focused our analysis on two clinically important SARS-CoV-2 variants: Delta, which emerged in mid-2021 and has greater transmissibility and moderately increased immune escape compared with earlier variants; and Omicron BA.1, which became the dominant variant beginning in late 2021, harbors more than 30 S protein mutations, and has markedly increased immune escape capabilities compared with earlier variants.26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 We examined viral replication and clearance, lung pathology, and antibody and T cell responses in these mice. The results reveal the influence of the Th1/Th2-biased genetic background, the specific SARS-CoV-2 variant, and the expression of hACE2 and/or hTMPRSS2 on these parameters. Our findings underscore the importance and utility of these new mouse models for investigating the underlying immunological mechanisms that dictate protection against and pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2.

Methods

Ethics

All experiments used 8- to 10-week-old male and female mice (1:1 ratio) housed at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology under specific pathogen-free conditions with a 12-h on/off light cycle. All study protocols and procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol AP00001242). All viral and animal manipulations were performed in a Biosafety Level 3 facility at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology.

Mice

Single-KI mice expressing hACE2 or hTMPRSS2 were generated by targeted transgenesis using pronuclear injection and gRNA-Cas9 targeting, as previously described.33, 34, 35, 36 Each of the two mouse target loci was reconfigured using constructs to insert an in-frame human cDNA minigene into exon 1 of the mouse equivalent gene and, thereby, disrupt transcription of the mouse gene. For the hACE2-KI mice, human ACE2 cDNA was inserted immediately downstream of the mAce2 signal peptide sequence. For the hTMPRSS2-KI mice, a cassette with a P2A “self-cleaving” peptide sequence followed by hTMPRSS2 cDNA was inserted in mTmprss2 exon 1 immediately following codon 18; the P2A sequence allows expression of hTMPRSS2 protein without any appended mTmprss2. To improve transcription efficiency, each humanized cDNA had a small 97-bp SV40 artificial intron at the start of the human intron. The remainder of the minigene was the human cDNA, from the 3′ untranslated region to the poly-A+ site, followed by a strong 3-frame stop codon to prevent unplanned read-through. In the opposite transcriptional sense and 3′ to the minigene, we placed an active cassette containing a strong multi-tissue U6 type III RNA polymerase promoter followed by gRNA targeting the WT insertion site of the humanization locus. If Cas9 is not encoded in the strain, the active genetic cassette is silent.

The desired insertion events were validated using PCR reactions designed to detect five PCR products: (1) the humanizing insert; (2,3) the borders of the insert at the 5′ and 3′ edge of the homology arms into the plasmid backbone (guarding against tandem and random integration events); and (4,5) the 5′ and 3′ integration in the genome, through the homology arms and into the insert. Animals positive for PCR products 1, 4 and 5 and negative for 2 and 3 were likely candidate founders and were bred with WT C57BL/6 or BALB/c animals. The resulting transgenic lines were each fully sequenced from ∼500 bp into the genomic DNA outside the homology arms through the entire insert sequence, and animals with sequences perfectly matching the planned sequence of donor plasmid DNA were carried forward for further breeding. Offspring genotypes were monitored to verify Mendelian segregation ratios of the targeted alleles, to further ensure that no random chromosome vector integration events had occurred. The top 5 predicted off-target sites were identified using CRISPR-Cas9 design checker tool (Integrated DNA Technologies), sequenced, and checked for the presence of indels; all strains were confirmed to be free of indels at these off-target sites. Thus, each strain carried a single copy of one of the two target constructs integrated in exon 1 of the respective mouse target site. DKI strains were generated by traditional Mendelian breeding of the single-humanized strains. The resulting 6 strains are available through Jackson Laboratories: ACE2-KI B6 (36899), TMPRSS2-KI B6 (36900), DKI B6 (37000), ACE2-KI BALB/c (37077), TMPRSS2-KI BALB/c (37078), and DKI BALB/c (37079). In addition, WT B6, BALB/c, and hACE2-K18 mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory.

RT-PCR analysis of hACE2 and hTMPRSS2 expression in mouse tissue

RNA was extracted from organs/tissues using an RNAqueous-4PCR Total RNA Isolation Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) per the manufacturer's recommendations, and the purity/concentration was calculated by measuring optical density (OD) at 260 nm and 280 nm. Aliquots of RNA normalized to the least concentrated sample were reverse transcribed using a High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Kit (Applied Biosystems) per the manufacturer's instructions, and cDNA samples were diluted with nuclease-free water and stored at −20 °C. PCR reactions were performed using the Q5 High Fidelity PCR Kit (NEB) per the manufacturer's suggested reaction setup using the following primers: hACE2 Fwd 5′-CCA ACC ACT ATC ACT CCC ATC-3′; Rev 5′-AGG CCC TCT CTG CAC AAA TGTG-3′; mAce2 Fwd 5′-CTG GCT CCT TCT CAG CCT TG-3′; Rev 5′-GGC TTG ATC TCT GCG AAG GT-3′; hTMPRSS2 Fwd 5-AAA ACC CCT ATC CCG CAC AG-3′; Rev 5′-CCG CAG GCT ATA CAG CGT AA-3′; mTmprss2 Fwd 5′-CCA CGG GTA TCA GTC TGA GC-3′; Rev 5′-AAT CCT GCT CTG GCG TTT CA-3′; and mGapdh Fwd 5′-GTT GTC TCC TGC GAC TTCA-3′; Rev 5′-GGT GGT CCA GGG TTT CTTA-3′. Cycling conditions were: denaturation (30 s, 98 °C); 35 cycles of annealing/synthesis (10 s at 98 °C, 30 s at 68 °C, 30 s at 72 °C); and extension (2 min, 72 °C). Amplicons were visualized on a 1% agarose gel under UV light, digitally imaged with GelDoc instrumentation and Image Lab software v5.0 (both from Bio-Rad), and band intensities were quantified using NIH ImageJ software.

Virus stocks and mouse infection

SARS-CoV-2 variants Delta (B.1.617.2) and Omicron BA.1 (B.1.1.529) were obtained through BEI Resources (NIAID, NIH) and propagated in Vero E6 cells (ATCC, CRL-1586) in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (Corning) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin–streptomycin, 1% HEPES buffer, and 1% non-essential amino acids. After 3 days, supernatants were harvested, 10-fold serially diluted, and titrated using a plaque assay. Briefly, Vero E6 cells were plated in 24-well plates (8 × 104 cells/well), grown to confluence, and incubated with viral supernatants for 2 h. The supernatants were then removed, 1% carboxymethylcellulose medium was added, and the plates were incubated for an additional 3 days. The cells were fixed with 10% formaldehyde for 1 h and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 20 min, both at room temperature. The identity of viral stocks was validated using deep sequencing performed by the La Jolla Institute for Immunology Sequencing Core. Mice were infected intranasally (IN) with Delta or Omicron BA.1 at 105 plaque-forming units (PFU) in 30 μL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) per mouse (15 μL/nostril). Vero cells (ATCC, CRL-1586) from the American Type Culture Collection were validated by the provider. All cell lines were routinely tested for Mycoplasma by PCR.

Clinical scoring

Clinical scoring was performed by a single, appropriately trained individual who was blinded to the experimental group ID, using a standardized and common method of assessing clinical disease in virally infected mice.37,38 Clinical scores were recorded daily beginning on the day of infection for 14 or 15 days post-infection (PI). Scores ranged from 1 to 6 as follows: (1) smooth coat, animal active, alert, and healthy; (2) slightly ruffled coat around head/neck, animal active/alert; (3) ruffled coat throughout the body, animal active and alert; (4) very ruffled coat, slightly inset eyes, walking but scurrying, mildly lethargic; (5) requires euthanasia, very ruffled coat, closed eyes, slow or no movement, extremely lethargic; and (6) found dead. Surviving mice were euthanized at the end of the experiment (day 14 or 15).

Quantification of viral RNA in tissues by RT-qPCR

Tissues were placed in RNA/DNA shield (ZYMO Research, R1100-250) to inactivate the virus and maintain high-quality RNA, transferred to RLT lysis buffer (containing 1% 2-mercaptoethanol), and homogenized at 30 Hz for 3 min using a Tissue Lyser II (QIAGEN). Total RNA was then extracted using an RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN) and stored at −80 °C until analysis. SARS-CoV-2 genomic E RNA and subgenomic 7a RNA were quantified using a qScript One-Step qRT-PCR Kit (Quanta BioSciences). For the E gene, published primer sets39 were used. For the 7a gene, published primer sets40 were modified: Fwd, 5′-TCC CAG GTA ACA AAC CAA CCA ACT-3′; Rev, 5′-AAA TGG TGA ATT GCC CTC GT-3′; and Probe, FAM-CAG TAC TTT TAA AAG ACC TT GCT CTT CTG GAA C-Tamra-Q. Finally, viral RNA concentration was calculated using a standard curve constructed from four 10-fold serial dilutions of in vitro-transcribed SARS-CoV-2 RNA (isolate USA-WA1/2020; ATCC, NR-52347) as previously described.37,41

Histopathology

Lungs were fixed in zinc formalin for 24 h at room temperature, transferred to 70% alcohol, embedded in paraffin, sectioned (4 μm), H&E stained using a Leica ST5020 autostainer, and imaged using a Zeiss AxioScan Z1 microscope with a 40 × 0.95 NA objective. Analyses were performed by a board-certified veterinary pathologist blinded to the group ID. Sections were scored on a 0 to 5 scale for each of 9 criteria associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection of rodent lung42: necrosis of bronchiolar epithelial cells, cellular debris in bronchioles, suppurative bronchiolitis, bronchiolar mucin, inducible BALT (iBALT) hyperplasia, perivascular lymphocytic cuffing, bronchointerstitial pneumonia, alveolar hemorrhage, and microvascular thrombosis.

Flow cytometry and intracellular cytokine staining assay

Spleens were dissociated into single-cell suspensions, red blood cells were removed with ACK lysing buffer, and the resulting splenocytes were seeded into 96-well round-bottomed plates (2 × 106 cells/well) in complete RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% HEPES, and 1% penicillin–streptomycin.

For immunophenotyping, splenocytes were incubated with viability dye (efluor 455UV, Invitrogen) and then surface stained with combinations of fluorophore-conjugated monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against the following mouse proteins: CD19 (eBioscience, eBio-1D3), CD138 (BioLegend, 281-2), IgD (BD Pharmingen, 11-26c-2a), CD95 (BD Horizon, Jo2), and GL7 (BD Pharmingen). Data were acquired on an LSRFortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software.

For intracellular cytokine staining, splenocytes were stimulated for 1 h at 37 °C with 10 μg/mL of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I- and class II-restricted peptides from SARS-CoV-2 S and nucleocapsid (N) proteins: MHC class I (S262-270, S539-549, S555-562, N149-157, and N219-227 for B6; S24-32, S37-47, S160-168, S260-270, S267-277, S310-318, S321-329, N45-53, N85-94, and N296-304 for BALB/c); and MHC class II (S62-76, S263-277, S1013-1027, N109-123 N129-143, and N145-159 for B6; S60-74, S263-277, S453-467, S886-900, and N82-96 N87-101 for BALB/c). Brefeldin A (BioLegend; 1:1000 dilution) was then added and the cells were incubated for an additional 4 h at 37 °C. For positive controls, peptides were replaced by Cell Stimulation Cocktail (eBioscience), and for negative controls, splenocytes were cultured without stimulation. After washing, the cells were stained with efluor 455UV viability dye and the appropriate combinations of fluorophore-conjugated mAbs against the following mouse proteins: CD3e (Tonbo, 145-2C11), CD4 (eBioscience, GK1.5), CD8a (BioLegend, 53–6.7), CD11a (BioLegend, M17/4), CD49d (BioLegend, R1-2), CD44 (Invitrogen, IM7), and CD62L (BD Horizon, MEL-14). Cells were then fixed, permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm, and stained with fluorophore-conjugated mAbs against mouse interferon-γ (IFNγ) (Tonbo, XMG1.2), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) (eBioscience, MP6-XT22), interleukin (IL)-2 (BioLegend, JES6-5H4), and IL-4 (eBioscience, 11B11). Data were collected on an LSRFortessa flow cytometer and analyzed using FlowJo software. All antibodies used in this study were validated by their respective manufacturer.

Peptide prediction and selection

To predict MHC class I- and class II-restricted T cell epitopes, S and N protein sequences for SARS-CoV-2/human/USA/WA-CDC-WA1/2020 isolate (GenBank MN985325.1) were obtained from the NCBI protein database and analyzed using the Immune Epitope Data Base & Tools (www.iedb.org) and the “IEDB-recommended” method. Peptides used here were selected separately for B6 and BALB/c mice (H-2b and H-2d MHC haplotypes, respectively). MHC class I or class II peptide binding affinity predictions were obtained for all nonredundant 8- to 11-mer peptides that bind mouse MHC I and 15-mer peptides that bind MHC II. The resulting peptide lists were sorted by consensus percentile rank, and the top 1% were selected, synthesized, purified to ≥95% by reverse-phase HPLC, and validated by mass spectrometry at TC Peptide Lab. Peptides were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide for use.

SARS-CoV-2 S-specific IgG ELISA

High-binding affinity 96-well plates (Costar) were coated with 1 μg/mL of recombinant SARS-CoV-2 Delta or Omicron BA.1 S protein (Sino Biological, 40607-V08B) overnight at 4 °C and then blocked with 5% blotting-grade casein (Bio-Rad) for 1 h at room temperature. The remaining steps were all performed at room temperature. Mouse sera were serially diluted 5-fold (1:50 to 1:156,250) in PBS/1% BSA and added to the coated wells for 1.5 h. The wells were then washed 3 times with PBS/0.05% Tween-20 (pH 7.4), incubated for 1 h with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG polyclonal Ab (Jackson ImmunoResearch) diluted 1:5000 in PBS/1% BSA, and washed again. Color development was achieved by incubation for 15 min in the dark with TMB substrate (Pierce) and the reaction was stopped by addition of 2 N sulfuric acid (Fisher Chemical). OD 450 nm was read immediately using a SpectraMax M2 microplate reader (Molecular Devices). The OD cutoff for positive reactivity was 2 standard deviations above the mean OD of the negative control wells.

Neutralizing Ab assays

Neutralizing Ab activity was expressed as NT50 (serum titer giving 50% of the maximum neutralization activity) and calculated using a previously described pseudovirus neutralizing assay.43 In brief, mouse sera were serially diluted 5-fold starting at 1:25, incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with a pre-determined amount of rVSV-SARS-CoV-2/GFP (Omicron BA.1 or Delta), and the supernatants were then transferred to Vero cell monolayers in 96-well plates and incubated for 16–18 h at 37 °C. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, stained with 1 μg/mL Hoescht in PBS for 30 min, and washed twice with PBS. GFP− (uninfected) and GFP+ (infected) cells were quantified using a CellInsight CX5 imager (ThermoFisher Scientific). For each sample, the percentage of infected cells was normalized to control cells (virus incubated without serum). The limit of detection was set at 25, the lowest serum dilution tested for each sample, and non-linear regression was used to calculate the NT50.

Depletion of CD4 and CD8 T cells

On each of the 3 days prior to infection with SARS-CoV-2, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 250 μg anti-CD4 (InViVomAb clone GK1.5, Bio X Cell, BE0003-1) plus 250 μg anti-CD8α (InViVomAb clone 2.43, Bio X Cell, BE0061) or with 500 μg isotype control mAb (InViVomAb rat IgG2b, Bio X Cell, BE0090l).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with Prism software v10 (GraphPad) and are expressed as the mean ± 95% confidence interval (CI). Normality of the data was assessed by Prism software v10 (GraphPad) using the Anderson–Darling and Shapiro–Wilk tests. If significant deviations from normality were identified, one-way ANOVA was deemed inappropriate as it assumes the data are normally distributed and instead, one-way Kruskal–Wallis test, as a nonparametric alternative to this parametric procedure, was considered. The Kruskal–Wallis test does not make assumptions about the distribution of the data and is robust to deviations from normality. In the same manner, for analyses involving comparisons based on two groups, two-way ANOVA was considered inappropriate if significant deviations from normality of the data were observed and instead two-way Kruskal Wallis test was utilized. For the comparisons involving only a group with two categories, groups, the Mann–Whitney U test was utilized. Two-way ANOVA was used with Šídák's post hoc test for multiple comparisons, with antibody depletion and mouse/virus as factors. P values are reported to 2 significant digits or as <0.0001, as appropriate.

Role of funders

The funding sources played no role in study design, data collection/analysis/interpretation, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Results

Generation and validation of 6 novel transgenic mouse lines: hACE2 and/or hTMPRSS2 KI on Th1- and Th2-biased genetic backgrounds.

For this study, we generated 6 transgenic mouse lines by KO of the respective endogenous genes and KI of hACE2, hTMPRSS2, or both hACE2 and hTMPRSS2) on the Th1-biased B6 (MHC H-2b) and the Th2-biased BALB/c (MHC H-2d) backgrounds. Effective KO of the endogenous genes and KI of the respective human genes were verified by RT-PCR analysis of 9 organs and tissues (Figure S1). As expected, expression of human ACE2 and/or TMPRSS2 but not mouse Ace2 and/or Tmprss2 were detectable in all organs and tissues tested from all 6 transgenic mouse strains.

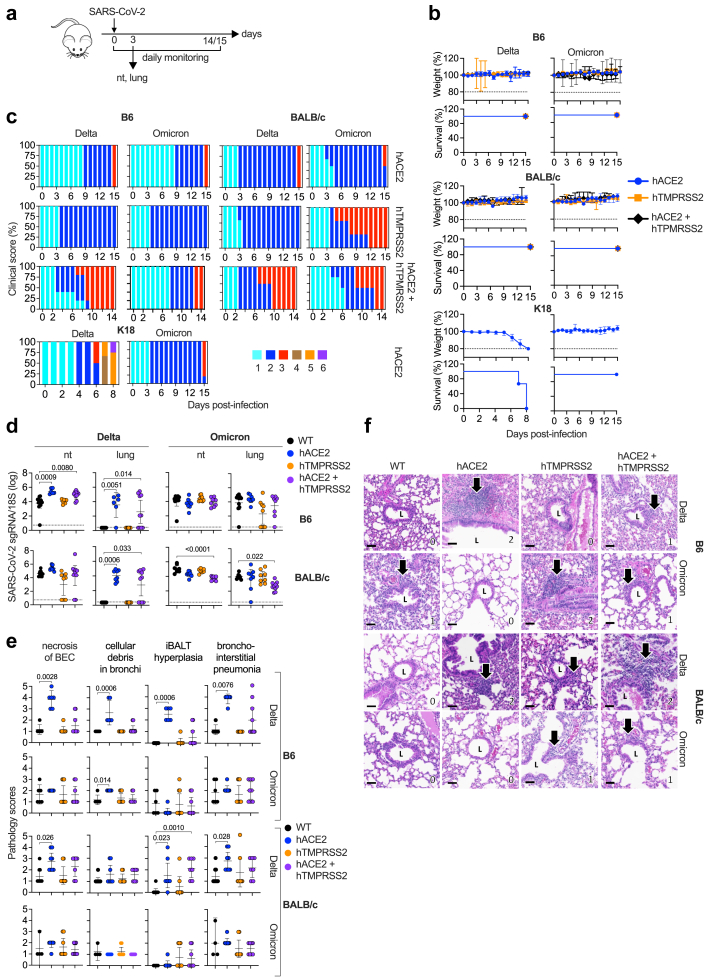

Disease course in SARS-CoV-2 Delta- and Omicron BA.1-infected single- and double-KI B6 and BALB/c mice

For SARS-CoV-2 to enter human cells, the viral S protein must be able to bind to hACE2. Delta also requires TMPRSS2-mediated S activation and membrane fusion,4,44,45 whereas Omicron BA.1 can enter cells using a TMPRSS2-independent mechanism of endocytosis.6, 7, 8, 9 To determine whether infection of cells with SARS-CoV-2 Delta or Omicron BA.1 via hACE2 and/or hTMPRSS2 is influenced by the genetic background, the 6 transgenic mouse lines were infected IN with Delta or Omicron BA.1 and then monitored for survival, weight, and clinical score for 14–15 days PI (Fig. 1a). Although none of the mice died or exhibited significant weight loss over the 15 days observation period (Fig. 1b), there were modest differences in clinical scores (Fig. 1c). For example, disease severity peaked more quickly in Delta-infected DKI mice than in single-KI mice, as reflected by the maximum clinical score of 3 occurring on day 7 PI in DKI mice compared with maximum clinical scores of 2 and 3 occurring on day 15 PI in single-KI hACE2 and hTMPRSS2 mice, respectively. In all three Omicron BA.1-infected mouse lines, clinical disease was relatively mild on the C57BL/6 background compared with the BALB/c background, where more severe disease was observed in both the single-KI hTMPRSS2 and DKI mice (clinical score of 3 starting on day 5 PI). We also performed the same analyses with K18-hACE2 B6 mice, which express very high levels of hACE2,46 and are highly susceptible to infection with ancestral SARS-CoV-2 strains (e.g., Delta) but less susceptible to infection with Omicron BA.1.47, 48, 49 Consistent with this, we observed that all Delta-infected K18-hACE2 B6 mice succumbed to (or were euthanized due to) disease by day 8 PI. In contrast, all Omicron BA.1-infected K18-hACE2 B6 mice survived through the 15-day observation period and exhibited relatively mild disease (score 2–3) that was only slightly accelerated compared with that seen in hACE2 B6 mice. Thus, the susceptibility of mice to infection and pathogenicity by Omicron BA.1, but not Delta, appears to be increased by expression of hTMPRSS2, and this was much more marked on the BALB/c compared with B6 background. In contrast, susceptibility of mice to Delta infection and pathogenicity appears to be increased by co-expression of hACE2 and hTMPRSS2 on both genetic backgrounds.

Fig. 1.

SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron BA.1 infectivity, clinical disease, and lung pathology in single- and double-KI hACE2 and hTMPRSS2 mice. (a) Experimental protocol: 8 mouse strains (B6 or BALB/c single-KI hACE2 and hTMPRSS2 or DKI, and WT B6 and BALB/c) were infected with Delta or Omicron BA.1 (105 PFU, IN) and monitored daily for 15 or 16 days (1 b and 1c), or sacrificed on day 3 PI for tissue harvest and analyses (1D–F). (b) Weight loss and survival in the 6 transgenic mouse lines. Mice that lost 20% or more of their body weight were euthanized. In survival analysis, all observations were considered as censored data because no deaths were observed. Median follow-up survival time was not calculated because all mice surviving to the end of the experiment were sacrificed for analysis. Survival curves were constructed using the Kaplan–Meier method. (c) Clinical scoring of the transgenic mouse lines generated here as well as the K18-hACE2 mouse line. Scores ranged from 1 (healthy) to 6 (found dead) (see Methods). (d) RT-qPCR analysis of SARS-CoV-2 subgenomic (sg) 7a RNA in the lungs and nasal turbinates (nt) of transgenic and WT mice. (e) Histopathology scores (range, 0–5 for least to most severe) for 4 parameters in the lungs of the transgenic and WT mice. (f) Representative H&E-stained histopathology images of iBALT hyperplasia (arrows). Scale bars = 50 μm. L, bronchiolar lumen. Numbers at the bottom right of each panel represent the scores for iBALT hyperplasia. Data in D and E are from 2 independent experiments and are presented as the mean ± 95% CI. Circles, individual mice; n = 6–12 mice/group. Dotted lines, limits of detection. Group means were compared using the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test.

Infection pattern in SARS-CoV-2 Delta- and Omicron BA.1-infected single- and double-KI B6 and BALB/c mice

We next examined whether hTMPRSS2 and/or hACE2 expression and the mouse genetic background influence Delta or Omicron BA.1 replication, as measured by RT-PCR quantification of SARS-CoV-2 subgenomic 7a RNA (a marker of recent virus replication50) in respiratory tissues collected on day 3 PI (Fig. 1a and d). Both Delta and Omicron BA.1 RNA were detected in the nasal turbinates of all WT B6 and BALB/c mice except for one Omicron BA.1-infected mouse on the B6 background (Fig. 1d). In contrast, Omicron BA.1, but not Delta, RNA was detected in the lungs of WT B6 and BALB/c mice (Fig. 1d). This result is consistent with studies showing that the S protein mutation carried by Omicron BA.1 (N501Y) enables it to bind more efficiently than Delta to mACE2, resulting in more productive infection in WT mice.3,51 Thus, in both B6 and BALB/c WT mice, Omicron BA.1 is able to productively infect both the upper and lower respiratory tracts, whereas Delta can infect the nasal turbinates but not the lungs of WT mice.

In contrast to WT mice, the expression of hACE2 and/or hTMPRSS2 and the genetic background both influenced the ability of Delta and Omicron BA.1 variants to infect the respiratory tract. Specifically, Delta exhibited complete dependence on hACE2 expression for infection of the lungs of both B6 and BALB/c mice, whereas Delta infection of the nasal turbinates was supported by either hACE2 or hTMPRSS2, albeit to a slightly lesser extent on the BALB/c compared with B6 background (Fig. 1d). In contrast, Omicron BA.1 was able to infect both the nasal turbinates and lungs of all single-KI and DKI mice, although the RNA levels were more variable in the lungs than the nasal turbinates on both B6 and BALB/c backgrounds. Thus, both Delta and Omicron BA.1 are able to utilize either hACE2 or hTMPRSS2 to productively infect the nasal turbinates, but the absence of hACE2 did reduce Delta infection of nasal turbinates in BALB/c mice. In the lungs, however, infection by Delta, but not Omicron BA.1, was completely dependent on hACE2 expression. Thus, comparing the data from the KI lines and WT mice indicates that expression of either mouse or human ACE2/TMPRSS2 proteins is sufficient for Omicron BA.1 to infect the upper or lower respiratory tract and for Delta to infect the upper respiratory tract, whereas hACE2 is absolutely required for Delta to infect the lungs of both B6 and BALB/c mice.

Histopathological lung disease induced by SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron BA.1 infection of single-KI and DKI B6 and BALB/c mice

Having demonstrated the influence of hTMPRSS2 and/or hACE2 expression and mouse genetic backgrounds on Delta and Omicron BA.1 infection of the respiratory tract, we next determined whether similar differences were observed in lung pathology. For this, lungs were harvested on day 3 PI, sectioned and H&E stained, and scored blinded by a board-certified veterinary pathologist for 9 histopathological parameters of SARS-CoV-2 infection, as previously described42 (Fig. 1e and f). Overall, the most marked lung damage caused by Delta infection occurred in hACE2 single-KI mice, with 4 parameters in hACE2 B6 and 3 parameters in hACE2 BALB/c mice being significantly higher than the scores in WT mouse lungs; moreover, the increases in severity appeared to be more robust in B6 mice than in BALB/c mice (Fig. 1e). In contrast, Omicron BA.1 infection resulted in significantly increased pathology scores compared with WT mice in only 1 parameter, and that was also observed in hACE2 B6 mice (Fig. 1e and Figure S2). Thus, Delta infection induced more severe lung damage than did Omicron BA.1 infection, and that was observed predominantly in hACE2-expressing mice.

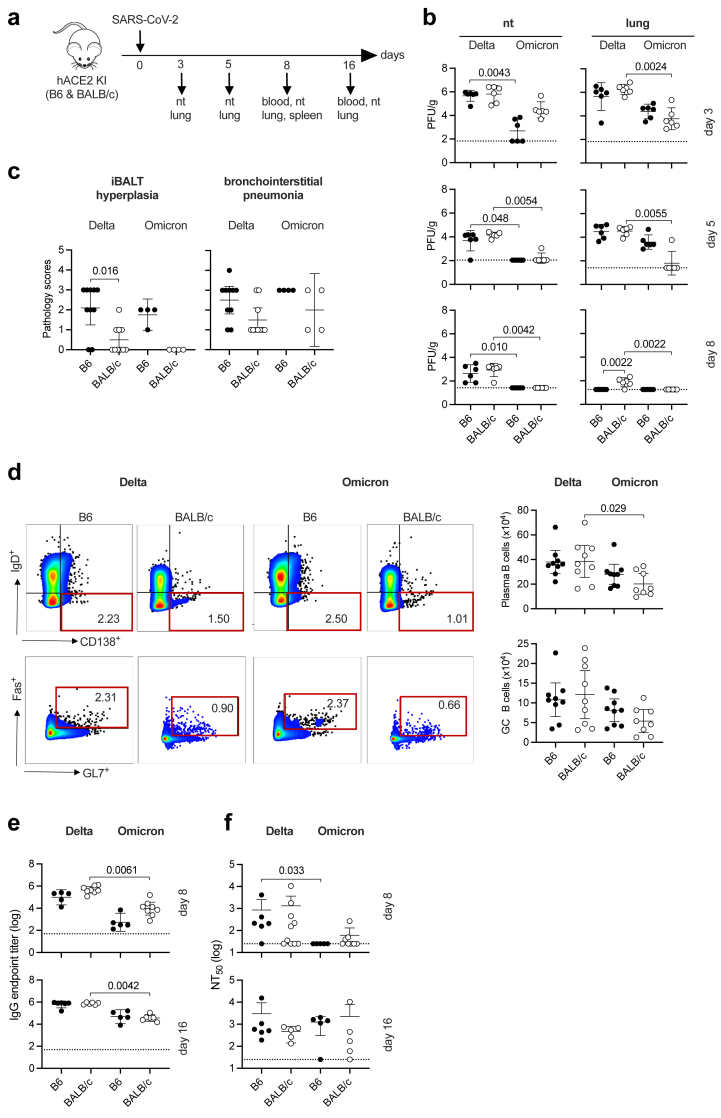

Viral dynamics and the humoral immune response in Delta- and Omicron BA.1-infected hACE2 B6 and hACE2 BALB/c mice

Because the most striking differences between Delta and Omicron BA.1 in terms of infection levels and lung pathology were observed in single-KI hACE2 mice (Fig. 1d and e, Figure S2), we focused our evaluation of viral kinetics and the immune response to these variants using hACE2 B6 and hACE2 BALB/c mice. Mice were IN infected with Delta or Omicron BA.1 and tissues were removed for analysis at various timepoints between 3 and 16 days PI (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron BA.1 infection kinetics, lung inflammation, and humoral immune responses in hACE2 B6 and hACE2 BALB/c mice. (a) Experimental protocol: hACE2 B6 and BALB/c mice were infected with Delta or Omicron BA.1 (105 PFU, IN) and tissues were harvested for analysis on the indicated days. (b) Levels of infectious virus (plaque assay) in the nasal turbinates (nt) and lungs on days 3, 5, and 8 PI (n = 6 mice/group). (c) Lung histopathology scores (0–5, least to most severe) on day 8 PI. N = 10 mice/group (Delta) or 4 mice/group (Omicron). (d) Flow cytometry plots and quantification of plasma cells (CD19+/CD138+/IgD−) and germinal center (GC) B cells (CD19+/CD138−/IgD−/FAS+/GL7+) in splenocytes prepared on day 8 PI (n = 8–9 mice/group). The full gating strategy is shown in Figure S4A. (e, f) Anti-SARS-CoV-2 S protein IgG endpoint titers (e) and NT50 titers (defined as serum titer with 50% maximal neutralizing activity) (f) in sera collected on days 8 and 16 PI (n = 5–10 mice/group). Data were pooled from 2 independent experiments except for the Omicron-infected mice in 2C, which were from a single experiment. All data are presented as the mean ± 95% CI. Circles, individual mice. Group means were compared using the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test.

We first analyzed the kinetics of Delta and Omicron BA.1 infection by quantifying infectious viral load in respiratory tissues of hACE2 B6 and BALB/c mice on days 3, 5, and 8 PI (Fig. 2b), and quantifying genomic and subgenomic RNA levels at day 16 PI (Figure S3). In nasal turbinates and lungs, levels of infectious Delta virus were similarly high in B6 and BALB/c mice on day 3 PI, and decreased thereafter until infectious Delta was detectable only in the lungs of B6 mice by day 8 PI (Fig. 2b). In contrast, infectious Omicron BA.1 levels were higher in the nasal turbinates of BALB/c than B6 mice on day 3, but levels were essentially undetectable in the nasal turbinates of both mouse strains by day 5. In the lungs, infectious Omicron BA.1 levels were higher in B6 compared with BALB/c mice on days 3 and 5 PI; but the virus was virtually undetectable in BALB/c mice by day 5 PI and in B6 mice by day 8 PI. Thus, in the hACE2 KI mice, Delta appears to be cleared more rapidly on the B6 compared with BALB/c background, whereas the reverse was true for clearance of Omicron BA.1 infection (Fig. 2b). Moreover, by day 16 PI, Delta and Omicron BA.1 subgenomic RNA was not detectable in the lungs or nasal turbinates of any of the KI mice, whereas genomic RNA was detectable in the nasal turbinates and lungs of all or most mice, respectively, with a trend towards higher levels of Delta than Omicron BA.1 genomic RNA (Figure S3). Thus, replicating Omicron BA.1 and Delta was completely eliminated from the respiratory tract of both mouse strains by day 16 PI.

Fig. 1e showed that lung damage was markedly more severe in Delta-infected hACE2 B6 and hACE2 BALB/c mice compared with in WT mice on day 3 PI, whereas little damage was observed in Omicron BA.1-infected mice at that time point (Fig. 1e). Analysis of lung histopathology at day 8 PI revealed increased iBALT hyperplasia and bronchointerstitial pneumonia scores in both Delta- and Omicron BA.1-infected hACE2 B6 compared with BALB/c mice (Fig. 2c), and interestingly, the scores at day 8 were lower than at day 3 for Delta-infected mice but higher than at day 3 for Omicron BA.1-infected mice (Fig. 2c and Figure S2). Thus, virus-induced lung pathology appears to resolve more rapidly in Delta-infected B6 mice compared with Omicron BA.1-infected mice on the same genetic background.

To analyze the humoral immune response to Delta and Omicron BA.1 in the hACE2 mice, B cell and total and neutralizing antibody profiles were evaluated. Flow cytometry was used to quantify plasma B cells and germinal center (GC) B cells in spleens of mice on day 8 PI (Fig. 2d), using the gating strategy shown in Figure S4a. The mean numbers of plasma and GC B cells were similar in Delta-versus Omicron BA.1-infected mice on both genetic backgrounds, although a small difference in plasma B cell numbers in BALB/c mice reached statistical significance (Fig. 2d). We next quantified Delta and Omicron BA.1 S protein-binding IgG levels and neutralizing Ab titers in blood collected on days 8 and 16 PI (Fig. 2e). Delta-specific IgG levels were significantly higher than Omicron BA.1-specific IgG in serum from BALB/c mice at both time points examined, but the strain background itself had no significant influence on individual virus-specific IgG levels (Fig. 2e). Similarly, neutralizing Ab titers elicited by either viral variant did not differ significantly between mouse strains on either day; however, there was a trend towards higher neutralizing Ab titers against Delta than Omicron in both mouse backgrounds on day 8, and this reached statistical significance in B6 mice (Fig. 2f). Thus, despite the faster clearance and greater iBALT hyperplasia observed in Delta-infected hACE2 B6 compared with BALB/c mice, we detected minimal differences overall between the two genetic backgrounds in terms of B cell expansion or Ab responses to primary infection with Delta and Omicron BA.1.

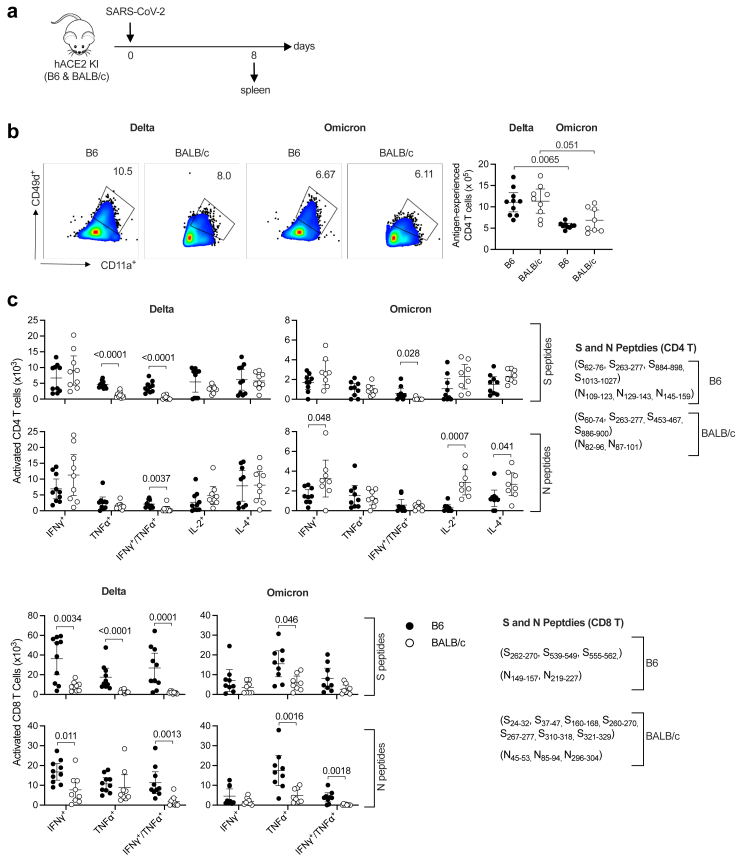

Antigen-specific CD4 and CD8 T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron BA.1 in hACE2 B6 and hACE2 BALB/c mice

To investigate T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron BA.1 in Th1- versus Th2-biased genetic backgrounds, splenocytes were isolated from hACE2 B6 or hACE2 BALB/c mice on day 8 PI (Fig. 3a) and stimulated in vitro with panels of SARS-CoV-2 S or N peptides (H-2b-restricted for B6 and H-2d-restricted for BALB/c). The cells were then immunolabeled for cell surface markers and intracellular cytokines and T cells were quantified by flow cytometry (Fig. 3b and c; gating strategies are shown in Figure S4b–d). The number of antigen-experienced CD4 T cells was significantly higher among splenocytes from Delta-infected mice compared with Omicron BA.1-infected mice, but there was no significant difference in the number of virus-specific cells between B6 and BALB/c mice (Fig. 3b). Similarly, more SARS-CoV-2 S- and N-specific CD4 T cells expressing cytokines (IFNγ+, TNFα+, IFNγ+/TNFα+, IL-2, or IL-4) were observed in Delta-infected than Omicron BA.1-infected mice on both the B6 and BALB/c backgrounds (Fig. 3c); in this case, however, there were significant mouse strain-specific differences in the abundance of Delta and Omicron BA.1 S- and N-specific CD4 T cells (Fig. 3c). Specifically, Delta elicited more S-specific TNFα+ and S- and N-specific IFNγ+/TNFα+ CD4 T cells in B6 compared with BALB/c mice; whereas Omicron BA.1 elicited more S-specific IFNγ+/TNFα+ CD4 T cells but fewer N-specific IFNγ+, IL-2+, and IL-4+ CD4 T cells in B6 compared with BALB/c mice (Fig. 3c). Strikingly, more activated S- and N-specific CD8 T cells producing IFNγ, TNFα, and IFNγ/TNFα were also elicited in Delta or Omicron BA.1-infected B6 mice compared with infected BALB/c mice (Fig. 3c). These data suggest that the Th1 response is more dominant in B6 mice than BALB/c mice, although the ratios of IFNγ-producing to IL-4-producing CD4 T cells were not significantly different between B6 and BALB/c mice (Table S1).

Fig. 3.

SARS-CoV-2 Delta- and Omicron BA.1- induced T cell responses in hACE2 B6 and hACE2 BALB/c mice. (a) Experimental protocol: hACE2 B6 and hACE2 BALB/c mice were infected with Delta or Omicron BA.1 (105 PFU, IN) and spleens were harvested on day 8 PI. (b) Flow cytometry plots and quantification of antigen-experienced CD4 T cells (CD11a+/CD49d+) in splenocytes. (c) Splenocytes were prepared and stimulated for 4 h in vitro with the indicated SARS-CoV-2 S or N peptides (see Methods) and activated CD4 T cells (CD44+) and CD8 T cells (CD44+/CD62L−) were identified and quantified by flow cytometry. The full gating strategies are shown in Figure S4b–d. Data were pooled from 2 independent experiments and are presented as the mean ± 95% CI. Circles, individual mice; n = 8–10 mice/group. Group means were compared using the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test (b) or the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test (c).

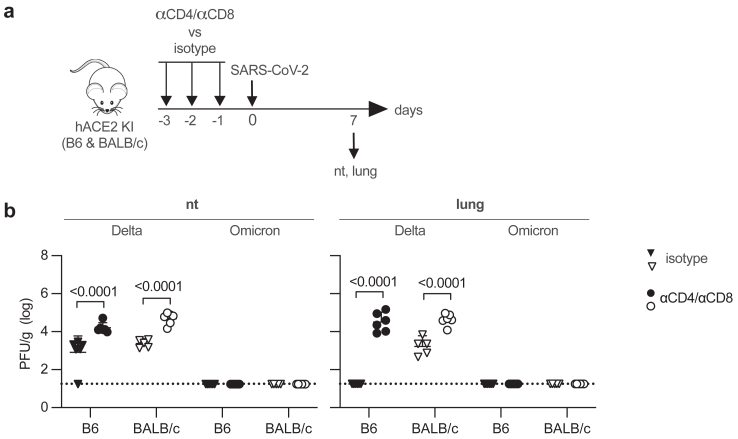

Contribution of CD4 and CD8 T cells to the clearance of SARS-CoV-2 Delta from hACE2 B6 and hACE2 BALB/c mice

The more robust CD4 and CD8 T cell responses observed in hACE2 B6 compared with BALB/c mice (Fig. 3c) suggested a possible role for T cells in the more rapid clearance of Delta from the lung of hACE2 B6 compared with BALB/c mice (Fig. 2b). To test this, CD4 and CD8 T cells were depleted in hACE2 B6 and BALB/c mice by injection of anti-CD4 plus anti-CD8 mAbs or isotype control mAb once daily for 3 days immediately prior to IN infection with Delta or Omicron BA.1. Infectious virus in the respiratory tract was then quantified on day 7 PI (Fig. 4a). Notably, levels of infectious Delta were significantly higher in both the nasal turbinates and lungs of T cell-depleted B6 and BALB/c mice than the corresponding control mAb-treated mice (Fig. 4b). As expected from the results of the viral kinetics experiments (Fig. 2b), infectious Omicron BA.1 was not detected in any of the tissue samples collected on day 7. These data identify a significant role for T cells in the clearance of SARS-CoV-2 Delta from the respiratory tract of infected hACE2-KI mice on both genetic backgrounds.

Fig. 4.

SARS-CoV-2 Delta clearance in the lungs of T cell-depleted hACE2 B6 and hACE2 BALB/c mice. (a) Experimental protocol: hACE2 B6 or BALB/c mice were injected intraperitoneally with a mixture of anti-mouse CD4-and anti-mouse CD8α-depleting mAbs or with rat IgG2b isotype control mAb on days −3, −2, and −1 and infected with Delta or Omicron BA.1 (105 PFU, IN) on day 0, and the nasal turbinates (nt) and lungs were harvested on day 7 PI. (b) Levels of infectious virus (plaque assay). Data were pooled from 2 independent experiments and are presented as the mean ± 95% CI. Circles, individual mice (n = 5–6 mice/group); dotted lines, limits of detection. Group means were compared using two-way ANOVA test followed by Šídák's post hoc test for multiple comparisons.

Discussion

In this study, we describe 6 new transgenic hACE2 ± hTMPRSS2 KI mouse strains on Th1- and Th2-biased genetic backgrounds representing 2 different mouse MHC haplotypes (H-2b and H-2d). These mice support productive SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron BA.1 infection to varying extents and recapitulate several key aspects of the pulmonary pathology and immunological consequences of viral infection seen in humans. We expect that these mice will be of great value for studying variant-specific tissue pathologies and heterogeneous immune responses, including their underlying mechanisms and effects on clinical outcome, thus advancing our understanding of studies using a single genetic background/MHC haplotype. Our data provide several insights into the pathological and immunological sequelae to SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron BA.1 infection, including the effect of host genetic background on viral clearance, lung pathology, and host immune response.

We found a significant difference between the ability of Delta and Omicron BA.1 to infect WT versus KI mice; specifically, the absolute dependence on hACE2 for infection of the lungs by Delta, which is consistent with the known inability of Delta S protein to bind to mAce2.3 However, in contrast to an earlier study, we found that Delta could infect the nasal turbinates in WT mice,52 suggesting that Delta infection of the upper and lower respiratory tract may depend on different host receptors. The reason for this discrepancy is unclear, but it may be due to differences un study design, such as different viral doses and RT-qPCR methods.52 We also observed that the kinetics of viral clearance from the lungs of hACE2 KI mice differed between B6 and BALB/c mice. Complete clearance of infectious Omicron BA.1 from the lungs was observed by day 5 PI in hACE2 BALB/c mice but not until day 8 PI in hACE2 B6 mice; conversely, Delta was cleared from the lungs of hACE2 B6 mice by day 8 PI, whereas it remained detectable in hACE2 BALB/c mice at the same time after infection. This finding aligns with prior studies suggesting enhanced viral clearance in ancestral SARS-CoV-2-infected B6 compared with BALB/c mice.53

Our histopathological assessment showed that lung pathology was more severe in Delta-infected compared with Omicron BA.1-infected hACE2-expressing mice, consistent with the more severe clinical outcomes in Delta-infected humans.54 Specifically, at day 8 PI, we observed a higher degree of iBALT hyperplasia in Delta-infected hACE2 on the B6 compared with BALB/c background, even though infectious viral loads were lower in the B6 mice. This finding suggests that a more robust local immune response in the lungs of hACE2 B6 mice may have contributed to faster viral clearance. iBALT has previously been shown to serve as an immune induction site capable of enhancing local and systemic B and T cell immune responses during viral respiratory infections.55 Some histopathologic changes were seen in the lungs of Delta-infected mice that did not express hACE2, even though Delta subgenomic RNA was not detected in the same lungs. We consider it likely that such histopathologic changes were due to aspiration of some of the IN inoculum, which can be immunogenic even if the virus is incapable of replication.

Despite the expectation that humanized mice on the B6 and BALB/c backgrounds may exhibit qualitatively distinct humoral responses to SARS-CoV-2,56 we observed no significant differences between the strains with respect to plasma cell and germinal center B cell responses, S protein-specific IgG levels, or neutralizing Ab titers PI. In contrast, S and N antigen-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells were more abundant in splenocytes from infected hACE2 B6 mice than from hACE2 BALB/c mice. mAb-mediated cell depletion studies showed that T cells were required for reducing infectious Delta in both hACE2 B6 and hACE2 BALB/c mice, revealing that the cellular immune response is a contributing factor in the viral clearance on both genetic backgrounds. This is in line with several human studies implicating a protective role for infection- and vaccine-induced T cell responses that produce the canonical Th1 cytokine IFNγ.57, 58, 59, 60, 61 More recent studies have identified the IFNγ pathway in natural killer and T cells as the dominant determinants of COVID-19 severity,23 and induction of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine-induced Th1-type cell responses have been shown to be decreased in older individuals,62 consistent with the greater vulnerability of older versus younger individuals to SARS-CoV-2 infection and disease.63 Thus, a Th1-biased response may be a key factor in determining the outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans.

Because genetic differences between B6 and BALB/c result in polygenic, far-reaching effects beyond Th1/Th2 bias, factors other than MHC haplotype and cellular immune response may confound the interpretation of our data. Previous studies comparing B6 and BALB/c responses to IN-inoculated bacterial pneumonia have also observed the respective prototypical Th1 and Th2 biases.19 Surprisingly, however, another study found that B6 mice infected with avian influenza virus exhibited more severe lung injury, slower recovery from lung damage, less effective viral clearance, and more of a Th2 phenotype with higher levels of IL-6 and lower levels of TNFα and IFNγ than infected BALB/c mice.18 Environmental and microbiomic confounding effects are less likely because our mice were all housed in the same facility and vivarium and were fed the same diet.

In conclusion, our study provides insights into the role of the host genetic background and immune response in SARS-CoV-2 infection and pathogenesis. Existing humanized models of SARS-CoV-2 infection have been constructed mainly on the B6 mouse genetic background, even though virus- and bacteria-infected mice on this background generally exhibit only mild symptoms14, 15, 16, 17 and BALB/c mice have been shown to develop more severe COVID-19-like disease than B6 mice.64,65 B6 and BALB/c mouse strains with transgenic KI of hACE2 and/or hTMPRSS2 thus provide valuable tools for modeling SARS-CoV-2 infection in the context of differing host genetics and MHC haplotypes. Understanding the key similarities and differences in the host immune response in these mice will likely play a critical role in producing new protective and therapeutic agents in our ongoing battle against future SARS-CoV-2 variants and novel coronaviruses.

Study limitations

Our study evaluated infection of 8 mouse strains with 2 SARS-CoV-2 variants, providing a strong foundation for future evaluation of additional aspects of host–virus dynamics in these models. Nevertheless, there are some limitations to our study. We did not conduct dose–response studies of viral infection or perform systematic analysis of infectious virus levels with plaque assays due to the large number of samples generated and the restrictions inherent to BSL3 facilities. Technical difficulties in performing FACS analysis under BSL3 conditions also resulted in a high percentage of non-viable lung cells for flow cytometric analyses.

Contributors

SKV, KK, and SS conceived the study. SKV, FASB, JT, and NS designed, performed, and analyzed the experiments. EM, PBAP, CC, KMV, RM, LT, KMV, and KK performed and analyzed the experiments. KJ and DW provided single-KI and DKI mice and reviewed the manuscript. SS, EOS, and KJ obtained funding. RPSA and AEN identified T cell epitopes. KMH provided rVSV-SARS-CoV-2/GFP (Omicron BA.1 or Delta) plasmids for neutralizing Ab assay. SS supervised the research. SKV, DOC, KK, and SS wrote the manuscript, with all other authors providing editorial comments. SKV, SS and KK have accessed and verified the data in this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data sharing statement

Qualified researchers who present a valid research question within the scope of the informed consent are eligible to access the deidentified data and study protocols utilized in this publication. For inquiries, please contact the lead corresponding author, Dr. Sujan Shresta.

Declaration of interests

CC, NS, and KJ were employees of Synbal, Inc. DOC is employed by and holds stock in TransViragen Inc.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge and remember the late Dr. Kurt Jarnagin, a visionary without whom this work would not have been possible. We also thank members of the Department of Laboratory Animal Care (Morag Mackay, Pascual Barajas, and Joseph Garza), Department of Environmental Health and Safety (Dr. Laurence Cagnon and David Hall), and Flow Cytometry Core (Cheryl Kim) at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology for their assistance with animal husbandry and experiments. We are also grateful to Dr. Michael Diamond, Division of Infectious Diseases, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, for providing the SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron BA.1 variants.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2024.105361.

Contributor Information

Kenneth Kim, Email: kenneth@lji.org.

Sujan Shresta, Email: sujan@lji.org.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Wu J.T., Leung K., Leung G.M. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):689–697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carabelli A.M., Peacock T.P., Thorne L.G., et al. SARS-CoV-2 variant biology: immune escape, transmission and fitness. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21(3):162–177. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00841-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shuai H., Chan J.F., Yuen T.T., et al. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants expand species tropism to murines. eBioMedicine. 2021;73 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271–280.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Letko M., Marzi A., Munster V. Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for SARS-CoV-2 and other lineage B betacoronaviruses. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5(4):562–569. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0688-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neerukonda S.N., Wang R., Vassell R., et al. Characterization of entry pathways, species-specific angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 residues determining entry, and antibody neutralization evasion of Omicron BA.1, BA.1.1, BA.2, and BA.3 variants. J Virol. 2022;96(17) doi: 10.1128/jvi.01140-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Willett B.J., Grove J., MacLean O.A., et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron is an immune escape variant with an altered cell entry pathway. Nat Microbiol. 2022;7(8):1161–1179. doi: 10.1038/s41564-022-01143-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meng B., Abdullahi A., Ferreira I., et al. Altered TMPRSS2 usage by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron impacts infectivity and fusogenicity. Nature. 2022;603(7902):706–714. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04474-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shuai H., Chan J.F., Hu B., et al. Attenuated replication and pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 Omicron. Nature. 2022;603(7902):693–699. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04442-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metzdorf K., Jacobsen H., Greweling-Pils M.C., et al. TMPRSS2 is essential for SARS-CoV-2 beta and Omicron infection. Viruses. 2023;15(2) doi: 10.3390/v15020271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Villadiego J., García-Arriaza J., Ramírez-Lorca R., et al. Full protection from SARS-CoV-2 brain infection and damage in susceptible transgenic mice conferred by MVA-CoV2-S vaccine candidate. Nat Neurosci. 2023;26(2):226–238. doi: 10.1038/s41593-022-01242-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robertson S.J., Bedard O., McNally K.L., et al. Genetically diverse mouse models of SARS-CoV-2 infection reproduce clinical variation in type I interferon and cytokine responses in COVID-19. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):4481. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-40076-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng J., Wong L.R., Li K., et al. COVID-19 treatments and pathogenesis including anosmia in K18-hACE2 mice. Nature. 2021;589(7843):603–607. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2943-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen J., Lau Y.F., Lamirande E.W., et al. Cellular immune responses to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) infection in senescent BALB/c mice: CD4+ T cells are important in control of SARS-CoV infection. J Virol. 2010;84(3):1289–1301. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01281-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsieh C.S., Macatonia S.E., O'Garra A., Murphy K.M. T cell genetic background determines default T helper phenotype development in vitro. J Exp Med. 1995;181(2):713–721. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mills C.D., Kincaid K., Alt J.M., Heilman M.J., Hill A.M. Pillars article: M-1/M-2 macrophages and the Th1/Th2 paradigm. J Immunol 2000. 164: 6166-6173. J Immunol. 2017;199(7):2194–2201. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts A., Paddock C., Vogel L., Butler E., Zaki S., Subbarao K. Aged BALB/c mice as a model for increased severity of severe acute respiratory syndrome in elderly humans. J Virol. 2005;79(9):5833–5838. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5833-5838.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao G., Liu C., Kou Z., et al. Differences in the pathogenicity and inflammatory responses induced by avian influenza A/H7N9 virus infection in BALB/c and C57BL/6 mouse models. PLoS One. 2014;9(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fornefett J., Krause J., Klose K., et al. Comparative analysis of humoral immune responses and pathologies of BALB/c and C57BL/6 wildtype mice experimentally infected with a highly virulent Rodentibacter pneumotropicus (Pasteurella pneumotropica) strain. BMC Microbiol. 2018;18(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s12866-018-1186-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carneiro M.B., Lopes M.E., Hohman L.S., et al. Th1-Th2 cross-regulation controls early leishmania infection in the skin by modulating the size of the permissive monocytic host cell reservoir. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27(5):752–768.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corripio-Miyar Y., Hayward A., Lemon H., et al. Functionally distinct T-helper cell phenotypes predict resistance to different types of parasites in a wild mammal. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):3197. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-07149-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Initiative C-HG Mapping the human genetic architecture of COVID-19. Nature. 2021;600(7889):472–477. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03767-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang S., Cooper-Knock J., Weimer A.K., et al. Multiomic analysis reveals cell-type-specific molecular determinants of COVID-19 severity. Cell Syst. 2022;13(8):598–614.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2022.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pavel A.B., Glickman J.W., Michels J.R., Kim-Schulze S., Miller R.L., Guttman-Yassky E. Th2/Th1 cytokine imbalance is associated with higher COVID-19 risk mortality. Front Genet. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.706902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gil-Etayo F.J., Suarez-Fernandez P., Cabrera-Marante O., et al. T-helper cell subset response is a determining factor in COVID-19 progression. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.624483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu L., Mok B.W.Y., Chen L.L., et al. Neutralization of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 Omicron variant by sera from BNT162b2 or CoronaVac vaccine recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;75(1):e822–e826. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu L., Iketani S., Guo Y., et al. Striking antibody evasion manifested by the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2022;602(7898):676–681. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04388-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cele S., Jackson L., Khoury D.S., et al. Omicron extensively but incompletely escapes Pfizer BNT162b2 neutralization. Nature. 2022;602(7898):654–656. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04387-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cao Y., Wang J., Jian F., et al. Omicron escapes the majority of existing SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies. Nature. 2022;602(7898):657–663. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04385-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Planas D., Saunders N., Maes P., et al. Considerable escape of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron to antibody neutralization. Nature. 2022;602(7898):671–675. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04389-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cameroni E., Bowen J.E., Rosen L.E., et al. Broadly neutralizing antibodies overcome SARS-CoV-2 Omicron antigenic shift. Nature. 2022;602(7898):664–670. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04386-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ai J., Zhang H., Zhang Y., et al. Omicron variant showed lower neutralizing sensitivity than other SARS-CoV-2 variants to immune sera elicited by vaccines after boost. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2022;11(1):337–343. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2021.2022440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ittner L.M., Gotz J. Pronuclear injection for the production of transgenic mice. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(5):1206–1215. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li D., Qiu Z., Shao Y., et al. Heritable gene targeting in the mouse and rat using a CRISPR-Cas system. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(8):681–683. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang H., Yang H., Shivalila C.S., et al. One-step generation of mice carrying mutations in multiple genes by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Cell. 2013;153(4):910–918. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conner C.M., van Fossan D., Read K., et al. A precisely humanized FCRN transgenic mouse for preclinical pharmacokinetics studies. Biochem Pharmacol. 2023;210 doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2023.115470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alves R., Wang Y.T., Mikulski Z., et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron (B.1.1.529) shows minimal neurotropism in a double-humanized mouse model. Antiviral Res. 2023;212 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2023.105580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dos Santos Alves R.P., Timis J., Miller R., et al. Human coronavirus OC43-elicited CD4(+) T cells protect against SARS-CoV-2 in HLA transgenic mice. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):787. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-45043-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corman V.M., Landt O., Kaiser M., et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(3) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alexandersen S., Chamings A., Bhatta T.R. SARS-CoV-2 genomic and subgenomic RNAs in diagnostic samples are not an indicator of active replication. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):6059. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19883-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bland J., Kavanaugh A., Hong L.K., Kadkol S.S. Development and validation of viral load assays to quantitate SARS-CoV-2. J Virol Methods. 2021;291 doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2021.114100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gruber A.D., Osterrieder N., Bertzbach L.D., et al. Standardization of reporting criteria for lung pathology in SARS-CoV-2-infected hamsters: what matters? Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2020;63(6):856–859. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2020-0280LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rydyznski Moderbacher C., Ramirez S.I., Dan J.M., et al. Antigen-specific adaptive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 in acute COVID-19 and associations with age and disease severity. Cell. 2020;183(4):996–1012.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koch J., Uckeley Z.M., Doldan P., Stanifer M., Boulant S., Lozach P.Y. TMPRSS2 expression dictates the entry route used by SARS-CoV-2 to infect host cells. EMBO J. 2021;40(16) doi: 10.15252/embj.2021107821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bayati A., Kumar R., Francis V., McPherson P.S. SARS-CoV-2 infects cells after viral entry via clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2021;296 doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Winkler E.S., Chen R.E., Alam F., et al. SARS-CoV-2 causes lung infection without severe disease in human ACE2 knock-in mice. J Virol. 2022;96(1) doi: 10.1128/JVI.01511-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Winkler E.S., Bailey A.L., Kafai N.M., et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection of human ACE2-transgenic mice causes severe lung inflammation and impaired function. Nat Immunol. 2020;21(11):1327–1335. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-0778-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Imbiakha B., Ezzatpour S., Buchholz D.W., et al. Age-dependent acquisition of pathogenicity by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.5. Sci Adv. 2023;9(38):eadj1736. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adj1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oladunni F.S., Park J.-G., Pino P.A., et al. Lethality of SARS-CoV-2 infection in K18 human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 transgenic mice. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):6122. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19891-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Speranza E., Williamson B.N., Feldmann F., et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals SARS-CoV-2 infection dynamics in lungs of African green monkeys. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13(578) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abe8146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stolp B., Stern M., Ambiel I., et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern display enhanced intrinsic pathogenic properties and expanded organ tropism in mouse models. Cell Rep. 2022;38(7) doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tarres-Freixas F., Trinite B., Pons-Grifols A., et al. Heterogeneous infectivity and pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 variants beta, delta and Omicron in transgenic K18-hACE2 and wildtype mice. Front Microbiol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.840757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leist S.R., Dinnon K.H., 3rd, Schafer A., et al. A mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 induces acute lung injury and mortality in standard laboratory mice. Cell. 2020;183(4):1070–1085.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fokam J., Essomba R.G., Njouom R., et al. Genomic surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 reveals highest severity and mortality of delta over other variants: evidence from Cameroon. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-48773-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moyron-Quiroz J.E., Rangel-Moreno J., Kusser K., et al. Role of inducible bronchus associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) in respiratory immunity. Nat Med. 2004;10(9):927–934. doi: 10.1038/nm1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bernal A.M., Fernandez-Brando R.J., Bruballa A.C., et al. Differential outcome between BALB/c and C57bl/6 mice after Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection is associated with a dissimilar tolerance mechanism. Infect Immun. 2021;89(5) doi: 10.1128/IAI.00031-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grifoni A., Weiskopf D., Ramirez S.I., et al. Targets of T Cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in humans with COVID-19 disease and unexposed individuals. Cell. 2020;181(7):1489–1501.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sekine T., Perez-Potti A., Rivera-Ballesteros O., et al. Robust T cell immunity in convalescent individuals with asymptomatic or mild COVID-19. Cell. 2020;183(1):158–168.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peng Y., Mentzer A.J., Liu G., et al. Broad and strong memory CD4(+) and CD8(+) T cells induced by SARS-CoV-2 in UK convalescent individuals following COVID-19. Nat Immunol. 2020;21(11):1336–1345. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-0782-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Painter M.M., Mathew D., Goel R.R., et al. Rapid induction of antigen-specific CD4(+) T cells is associated with coordinated humoral and cellular immunity to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination. Immunity. 2021;54(9):2133–21342.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mateus J., Dan J.M., Zhang Z., et al. Low-dose mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine generates durable memory enhanced by cross-reactive T cells. Science (New York, NY) 2021;374(6566) doi: 10.1126/science.abj9853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jo N., Hidaka Y., Kikuchi O., et al. Impaired CD4(+) T cell response in older adults is associated with reduced immunogenicity and reactogenicity of mRNA COVID-19 vaccination. Nat Aging. 2023;3(1):82–92. doi: 10.1038/s43587-022-00343-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen T., Dai Z., Mo P., et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of older patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75(9):1788–1795. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glaa089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dinnon K.H., 3rd, Leist S.R., Schafer A., et al. A mouse-adapted model of SARS-CoV-2 to test COVID-19 countermeasures. Nature. 2020;586:560. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2708-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sun J., Zhuang Z., Zheng J., et al. Generation of a broadly useful model for COVID-19 pathogenesis, vaccination, and treatment. Cell. 2020;182(3):734–743.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.