Summary

Background

Influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (IAPA) is a severe fungal superinfection in critically ill influenza patients that is of incompletely understood pathogenesis. Despite the use of contemporary therapies with antifungal and antivirals, mortality rates remain unacceptably high. We aimed to unravel the IAPA immunopathogenesis as a means to develop adjunctive immunomodulatory therapies.

Methods

We used a murine model of IAPA to investigate how influenza predisposes to the development of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Immunocompetent mice were challenged with an intranasal instillation of influenza on day 0 followed by an orotracheal inoculation with Aspergillus 4 days later. Mice were monitored daily for overall health status, lung pathology with micro-computed tomography (μCT) and fungal burden with bioluminescence imaging (BLI). At endpoint, high parameter immunophenotyping, spatial transcriptomics, histopathology, dynamic phagosome biogenesis assays with live imaging, immunofluorescence staining, specialized functional phagocytosis and killing assays were performed.

Findings

We uncovered an early exuberant influenza-induced interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) production as the major driver of immunopathology in IAPA and delineated the molecular mechanisms. Specifically, excessive IFN-γ production resulted in a defective Th17-immune response, depletion of macrophages, and impaired killing of Aspergillus conidia by macrophages due to the inhibition of NADPH oxidase-dependent activation of LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP). Markedly, mice with partial or complete genetic ablation of IFN-γ had a restored Th17-immune response, LAP-dependent mechanism of killing and were fully protected from invasive fungal infection.

Interpretation

Together, these results identify exuberant viral induced IFN-γ production as a major driver of immune dysfunction in IAPA, paving the way to explore the use of excessive viral-induced IFN-γ as a biomarker and new immunotherapeutic target in IAPA.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO), project funding under Grant G053121N to JW, SHB and GVV; G057721N, G0G4820N to GVV; 1506114 N to KL and GVV; KU Leuven internal funds (C24/17/061) to GVV, clinical research funding to JW, Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) aspirant mandate under Grant 1186121N/1186123 N to LS, 11B5520N to FS, 1SF2222N to EV and 11M6922N/11M6924N to SF, travel grants V428023N, K103723N, K217722N to LS. FLvdV was supported by a Vidi grant of the Netherlands Association for Scientific Research. FLvdV, JW, AC and GC were supported by the Europeans Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement no 847507 HDM-FUN. AC was also supported by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT), with the references UIDB/50026/2020, UIDP/50026/2020, PTDC/MED-OUT/1112/2021 (https://doi.org/10.54499/PTDC/MED-OUT/1112/2021), and 2022.06674.PTDC (http://doi.org/10.54499/2022.06674.PTDC); and the “la Caixa” Foundation under the agreement LCF/PR/HR22/52420003 (MICROFUN).

Keywords: Influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (IAPA), Pathogenesis, Interferon-gamma, T-helper 17, Macrophages, LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP)

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Before this investigation, only limited research had been carried out on the underlying mechanism of influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (IAPA). A search on PubMed conducted on July 17, 2024, using the keywords “influenza” and “aspergillosis” yielded 290 search results. While several observational studies have reported on the incidence of IAPA in patients, and several reviews have proposed various hypotheses about the underlying pathophysiology of IAPA, only two studies examined the pathophysiology of IAPA in patient samples. Additionally, only seven studies described animal models for IAPA, with just four of them specifically focusing on unravelling the pathophysiology of IAPA and one study investigating IAPA in vitro. The next key research question to address is understanding the longitudinal immunological information that reveals how influenza alters the antifungal host innate and adaptive immune response during and at the time of fungal superinfection in these IAPA models. In addition, the immunopathogenesis of IAPA has not been investigated as a mean to explore potential adjunctive immunomodulatory therapies.

Added value of this study

We employed a physiologically relevant immunocompetent mouse model of IAPA to longitudinally profile the respiratory host immune response from a morphological and immunological point of view. We used this model to dissect the mechanisms driving life-threatening IAPA-pathogenesis, to identify targets relevant for therapeutical interventions, and validate the life-saving therapeutic potential of these targets. Using state-of-the-art techniques we identified an early exaggerated viral-induced production of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) as the major driver of immunopathology which resulted in a defective Th17-immune response, depletion of alveolar macrophages and impaired killing of Aspergillus conidia by macrophages due to the inhibition of NADPH oxidase-dependent activation of LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP). Partial or complete genetic ablation of IFN-γ production restored Th17-immune response, LAP-dependent killing and thus protected mice from invasive fungal infection and mortality.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our study represents the first steps towards understanding the host-pathogen factors driving IAPA and highlights the importance of a balanced IFN-γ immune response during infection. These findings open new avenues to explore the use of excessive viral-induced IFN-γ as a potential biomarker and as an immunotherapeutic target to be used in conjunction with standard antiviral and antifungal treatment in IAPA. Our results suggest a new paradigm in which timely modulation of the host immune response during influenza may be critical in preventing the progression into IAPA. Only by identifying host-pathogen factors that correlate with disease we can stratify patients for immunotherapy-based strategies or establish clinical interventional trials to study host-directed medicine approaches.

Introduction

Reports of fungal superinfection in respiratory viral infection are increasing worldwide.1, 2, 3 Aspergillus fumigatus is a ubiquitous mold that can cause invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) in susceptible individuals, including patients with severe viral respiratory tract infections such as influenza and COVID-19. Recent studies show incidences as high as 15–20% for influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (IAPA) and 10–15% for COVID-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA), with an associated mortality of around 50% in comparison with 25–35% in patients with severe influenza or COVID-19 as single infection.4 Despite contemporary antiviral and antifungal therapies, morbidity, mortality and length of hospital stay associated with viral-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (VAPA), remain unacceptably high. We address the unmet need for understanding the pathophysiology of VAPA in order to design targeted host-directed immunomodulatory therapies and improve disease outcome.

The pathogenesis of Aspergillus infection in severe influenza is largely unexplored, but the well-known association of bacterial superinfections with influenza suggests a specific role for influenza in the increased susceptibility to secondary infections.5 Only recently have efforts been devoted to the identification of host-pathogen interactions in the pathogenesis of IAPA. A three-level breach in the antifungal immunity in patients with IAPA or CAPA has been proposed, affecting neutrophils, the epithelial barrier, and functionality of macrophages.4 Underlying molecular mechanisms of immune dysfunction, however, remain uncharacterized.

Clinically relevant animal models of IAPA can be used to dissect the pathogenic mechanisms. Multiple mouse models of IAPA exist, with differences in immune competence.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 The immunosuppressed models of IAPA hamper the ability to provide immunological insights in the pathogenesis of IAPA in a host without pre-existing immunocompromised conditions.11 Immunocompetent models of IAPA overcome this drawback, but immunological observations remain scarce. Neutrophil recruitment to the lung and airways seemed diminished in a murine model of IAPA,6,12 while Liu et al. report an impaired capacity of neutrophils to phagocytose Aspergillus due to a phagolysosomal maturation defect in influenza infected mice.9 Sarden et al. found an influenza-induced depletion of B1a lymphocytes and anti-Aspergillus immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies in IAPA mice and confirmed their results in patient samples. This depletion allowed for invasive Aspergillus growth through reduced recognition by neutrophils.10 However, there are currently no studies investigating the longitudinal immunological response underlying IAPA. Knowing how influenza alters the anti-fungal host innate and adaptive immune response during and at the time of fungal superinfection is essential for identifying potential targets that could pave the way for the development of new host-directed immunomodulatory therapies or allocation of existing immunomodulatory drugs.

Therefore, we aimed to use our mouse model of IAPA to longitudinally profile the respiratory host immune response, to dissect the different influenza-induced cellular and functional defects in the innate and adaptive antifungal host immune response, to thereby identify targets relevant for host-directed immunomodulatory therapy and validate the therapeutic potential of these targets. Identifying relevant host-pathogen factors could open avenues to explore host-directed immunomodulatory therapy approaches alongside pathogen-directed antivirals and antifungals in interventional clinical trials, potentially reducing IAPA mortality.

Methods

Viral and fungal strain background

Influenza strain

For viral infection, a mouse-adapted influenza virus A/H3N2/Ishikawa/7/82 was used.7

Aspergillus fumigatus strain

For in vivo fungal infection, a previously constructed, wild-type bioluminescent A. fumigatus strain with a red spectrum light emission was utilized.7,13 The A. fumigatus strain is derived from the CBS144.89 strain, expressing a red-shifted thermostable firefly luciferase, and was cultured and harvested according previously established protocols.7,13 For the ex vivo Aspergillus infection experiments we used the CBS133.89 (CEA10) (Phagocytosis and killing in BAL); ATCC46645 (Killing assay in BMDM, total ROS in BAL) and Δpksp ATCC46645 (LC3 in BMDM and BAL, total ROS in BMDM).

Mouse model, experimental design and procedures

Ethics

All animal experiments were undertaken with approval of the Ethics Committee on Animal research (license ECD number p074/2018 & p094/2022). The sample size was determined based on a priori power calculations (unpaired t test, power = 80%, alpha = 0.05) upon formulating hypotheses, submitted to and checked by our animal ethics committee, which included a biostatistician. Total number of animals used are detailed in the figure legends. No animals were excluded during experiments.

Study design

WT, IFN-γ+/−, IFN-γ−/− on a C57BL/6 background were bred under specific pathogen free (SPF) conditions in the animal house of KU Leuven. During the experiments, mice were maintained in a conventional animal facility in individually ventilated cages with free access to food and water. Upon arrival, animals were acclimated to their new environment by transferring a small amount of cotton wool from their original cage into the new cage to reduce stress. An antibiotic (50 mg/kg/day, Baytril®, Bayer) was added to the drinking water to prevent bacterial infections. Eight to twelve weeks old immunocompetent male mice were randomly allocated to different experimental groups based on their genotype. Upon arrival, animals will be acclimated to their new environment by transferring a small amount of cotton wool from their original cage into the new cage. L.S. performed the in vivo experiments and was aware of the group allocation, all other authors were blinded. A longitudinal morphological and respiratory immunological profiling of our IAPA murine model was performed and the role of IFN-γ in IAPA was assessed in IFN-γ−/− and IFN-γ+/− mice. Mice were infected with 10 plaque forming units (PFU) mouse-adapted influenza virus A/H3N2/Ishikawa/7/82 or sham (PBS) on day 0 and orotracheally inoculated with 20 μL of a red-shifted thermostable firefly luciferase Aspergillus fumigatus spore solution (5 x 109 conidia/mL) or sham (PBS) under inhalation anesthesia with isoflurane (1.5–2% in 100% oxygen, Piramal Critical Care) on day 4.7 Mice were longitudinally followed up with micro-computed tomography (μCT) and bioluminescence imaging (BLI) to assess respectively lung pathology and fungal burden. After scanning, mice are placed on a heating pad to recover. Clinical scores were measured twice daily (body weight, respiratory parameters and condition) and sacrifice was performed at predefined endpoints with an overdose of pentobarbital via intraperitoneal injection or when humane endpoint was reached (Supplementary Figure S1). On specific endpoints mycological examinations, high parameter flow cytometry, spatial transcriptomics, histopathology, dynamic phagosome biogenesis assays with live imaging, immunofluorescence staining, specialized functional phagocytosis and killing assays in bronchoalveolar lavage, lungs or bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) of IAPA, healthy and single infection control mice were performed. All antibodies used in the study are commercially available antibodies.14,15

Assessment of longitudinal in vivo lung pathology and in vivo/ex vivo fungal burden

Acquisition, visualization and quantification of lung pathology with micro-computed tomography (μCT) (Bruker μCT, Kontich, Belgium) and bioluminescence imaging (BLI) (Perkin–Elmer, Hopkinton, MA, USA) of the luciferase-tagged A. fumigatus as a proxy of viable fungal burden were performed as previously described.7,8,16

For endpoint fungal load detection, we performed ex vivo BLI and colony forming unit (CFU) counting.

Assessment of the viral load

The viral load was assessed by determining the CCID50 in lung homogenates.7,8 Briefly, viral titer determination involved adding serial dilutions of right lung homogenate supernatants to MDCK cells in quadruplicate, incubating at 35 °C for 72 h, and assessing the cytopathic effect by microscopy scoring.

Tissue preparation

Perfused lungs were aseptically harvested in complete RPMI (RPMI 1640 (ThermoFisher Scientific)) supplemented with 10% FCS (Tico Europe, Amstelveen, Netherlands), nonessential amino acids (Gibco) and HEPES (Gibco) and kept on ice until further processing. Single cells were obtained after mechanical dissociation of the lungs and digestion in digestion buffer (PBS (ThermoFisher Scientific), 3% FCS (Tico Europe, Amstelveen, Netherlands), 2 mg/ml collagenase IV (ThermoFisher Scientific)) for 1 h at 37 °C. After incubation, cells were passed through a 100 μm nylon cell strainer and red blood cells were lysed with an erythrocyte cell lysis buffer as previously described.15

Lung leukocyte flow cytometry

Lung lymphoid, myeloid & cytokine staining

Lung cells (106 per sample) were transferred to a 96-well tissue-culture plates in complete RPMI (ThermoFisher Scientific). For lymphoid cytokine determination, cells were stimulated with RPMI (ThermoFisher Scientific) containing phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate (500 ng/ml, Bio-Techne), Ionomycin (750 ng/ml, Bio-Techne) and Brefeldin A (2 μg/ml, Bio-Techne) for 4 h at 37 °C. 2.4G2 supernatant (ATCC (cat: HB197)) was used for non-specific binding. For surface staining, cells were labeled with a fixable viability dye eFluor 780 (ThermoFisher, 65-0865-14), anti-CD4 (GK1.5, RRID:AB_2722549), anti-CD3 (17A2, RRID:AB_10900444), anti-CD8 (53-6.7, RRID:AB_2870186), anti-CD19 (1D3, RRID:AB_2722936), anti-TCRγδ (GL3, BD Biosciences). For intracellular staining, cells were fixed with 2% formaldehyde (VWR), permeabilized with a 1x eBioscience permeabilization buffer (ThermoFisher Scientific) and overnight stained with anti-TNF-α (MP6−XT22, RRID:AB_2562902), anti-CD3 (17A2, RRID:AB_10900444), anti-CD11b (M1/70, RRID:AB_2871704), anti-CD19 (1D3, RRID:AB_2722936), anti-TCR-beta (H57-597, RRID:AB_493345), anti-TCRγδ (GL3), anti−CD45 (30-F11), anti-NK.1.1 (PK136, RRID:AB_313389), anti-IL17 (TC11-18H10, RRID:AB_2722575), anti-CD4 (GK1.5, RRID:AB_2722549), anti-IFN-γ (XMG1.2, RRID:AB_2722494), anti-CD8 (53-6.7, RRID:AB_2870186), anti-FoxP3 (REA788, RRID:AB_2651768) and anti-IL22 (Poly5164, RRID:AB_2124255). For lymphoid cell determination, cells were incubated with 2.4G2 hybridoma supernatant (ATCC (cat: HB197)) for 30 min. For surface staining, cells were labeled with a fixable viability dye eFluor 780 (ThermoFisher, 65-0865-14), anti-CD19 (1D3, BD Biosciences), anti-CD45 (30-F11, BD Biosciences), anti-CD69 (H1.2F3, RRID:AB_313113), anti-CD4 (GK1.5, RRID:AB_2722549) and anti-CD62L (MEL-14, BD Biosciences). For intracellular staining, cells were fixed with eBioscience FoxP3 fix/perm buffer (ThermoFisher Scientific), permeabilized with 1x eBioscience permeabilization buffer (ThermoFisher Scientific) and overnight stained with anti-CD25 (PC61, RRID:AB_2739522), anti-CD44 (IM7, RRID:AB_10900641), anti-CD3 (17A2, RRID:AB_11204249), anti-PD1 (29 F.1A12, RRID:AB_2566158), anti-CD19 (1D3), anti-TCRβ (H57-597, RRID:AB_493345), anti-T-bet (4B10, BD Biosciences), anti-RORγt (B2D, RRID:AB_10805392), anti-NK1.1. (PK136, RRID:AB_313389), anti-CD4 (GK1.5, RRID:AB_2722549), anti-CTLA-4 (UC10–4F1, BD Biosciences), anti-GATA3 (L50-823, BD Biosciences), anti-CD8 (53-6.7, RRID:AB_2870186), anti-FoxP3 (REA788, RRID:AB_2651768) and anti-KI-67 (16A8, RRID:AB_2564285). For myeloid cells determination, cells were stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS (L2880, Sigma Aldrich) and Brefeldin A (2 μg/ml, Bio-Techne) for 4 h at 37 °C. Unstimulated control wells from each sample were included. 2.4G2 supernatant (ATCC (cat: HB197)) was used for non-specific binding. For surface staining, cells were labeled with a fixable viability dye eFluor 780 (ThermoFisher, 65-0865-14), anti-CD4 (GK1.5, RRID:AB_2722549), anti-CD163 (RRID:AB_2814063) and anti-CD8 (53-6.7, RRID:AB_2870186). For intracellular staining, cells were fixed with 2% formaldehyde (VWR), permealized with a 1x eBioscience permeabilization buffer (ThermoFisher Scientific) and overnight stained with anti-Ly6G (1A8, RRID:AB_10899738), anti-CD11b (M1/70, RRID:AB_2871704), anti-TNF-α (MP6-XT22, RRID:AB_493328), anti-TCRγδ (GL3, BD Biosciences), anti-TCRβ (H57-597, BD Biosciences), anti-CD64 (X54-5/7.1, RRID:AB_2566559), anti-CD11c (N418, RRID:AB_2925254), anti-CD4 (GK1.5, RRID:AB_2722549) anti-SiglecF (E50-2440, BD Biosciences), anti-CD8 (53-6.7, RRID:AB_2870186) and anti−IFN-γ (XMG1.2, RRID:AB_2722494). Cells were acquired with the BD FACSymphony and results were analyzed with FlowJo version 10.8.1 (Becton Dickinson, Ashland). Compensation for high parameter flow panels was performed using Autospill.17 The gating strategy can be found in Supplementary Figures S2 & S3.

Assessment of ROS levels in immune cells: single-cell and total ROS analysis

Flow cytometry: ROS determination on a single cell basis in broncho-alveolar lavage fluid (BALF)

BALF was collected after three lung lavages with 700 μL 0.9% NaCl (B. Braun). 1 × 106 BAL cells per sample were transferred to a 96-well tissue-culture plates in complete RPMI (ThermoFisher Scientific). Cells were stimulated with Phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate (500 ng/ml, Bio-Techne) or complete RPMI (ThermoFisher Scientific) and 0.025 mM Dihydrorhodamine (DHR) 123 (invitrogen, D23806, RRID: AB_3097834) for 20 min at 37 °C. After incubation cells were incubated for 15 min at room temperature (RT) in the dark with a viability dye, Zombie Aqua (BioLegend). For surface staining, BAL cells were stained for 20 min on ice with anti-CD11c (N418, RRID:AB_469588), anti-CD11b (M1/70, RRID:AB_469588), anti-Ly6G (1A8, RRID:AB_10897944), anti-CD45 (30-F11, RRID:AB_1548781), anti-SiglecF (E50-2440, RRID:AB_394341). Afterwards, cells were fixed with 0.5% formaldehyde (VWR) for 15 min in PBS (ThermoFisher Scientific) and acquired on the BD FACSCanto II. The gating strategy can be found in Supplementary Figure S2.

Live imaging to determine the total ROS levels in BALF

DHR-123 labelling of Aspergillus

For DHR-123 labelling, Δpksp A. fumigatus (ATCC46645) or A. fumigatus (ATCC46645) was diluted in 0.1 M NaHCO3 (Fluka) pH 8.3 and incubated with DHR-123 dye (final concentration in DMSO, 0.5 mg/ml, sc-203027 Santa Cruz) for 2 h at room temperature while rotating. After staining, ΔpksP conidia were washed two times with 100 mM glycine (Applichem) and 1x with PBS (ThermoFisher Scientific) and immediately used for experiments.

Live imaging and ROS measurement

100 000 BAL cells were plated in a 96-well plate and infected with DHR-123-labelled Aspergillus (ATCC46645) with a MOI of [3:1]. Immediately after infection, the 96-well plate was transferred to the Nikon Ti-2 microscope (Tokyo, Japan) with an Andor Dragonfly 200 spinning disk confocal microscope system (Andor, Oxford instruments, Belfast, UK), equipped with four excitation lasers (405, 488, 561, and 637 nm), controlled by the Fusion software for live imaging. All the images were acquired and images were taken with a Plan-Apo 60×, 1.4 NA Nikon oil immersion objective and a Sona 4.2B-6 USB DFly2 Back-illuminated sCMOS camera. After 0 h and 2 h imaging, mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of DHR-123 was measured by using ImageJ software.

Cytokine measurements

Cytokine quantification was performed using the Cytokine Target 48 panel from Olink (Olink service platform, KULeuven). Samples were incubated in the dark at 4 °C for 20 h with antibodies coupled to molecular probes. Afterwards, molecular probes were amplified with PCR using the T100 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad), followed by quantification through qPCR in the Olink Signature Q100. Quality control of the data was performed using the Olink NPX Signature software (version 1.12.1).

Histopathology

Lungs were fixed with 10%-formalin and 24 h post fixation stored in PBS-0.1% sodium-azide (Sigma–Aldrich) at 4 °C. Subsequently, paraffin embedded and 5 μm sagittal sections were stained with haematoxylin-eosin (H&E) and Grocott's methenamine silver staining (GMS). Stainings were scored by a blinded pathologist (E.Ve).

Spatial transcriptomics using GeoMx®

Inflammatory lung regions of influenza only, Aspergillus only and IAPA infected mice were analyzed with spatial transcriptomics by using GeoMx® Digital Spatial Profiler (DSP) using the Mouse NGS whole transcriptome Atlas. GeoMx DSP user manuals were used for slide preparation, sample collection, library preparation and data analysis (MAN-10115-05, SEV-00087-05, MAN-10117-05, SEV-00090-05).4 In brief, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) mouse samples were baked overnight at 37 °C and 1 h at 65 °C, and processed on Leica automation platform. The protocol includes three major steps: 1) slide baking, 2) Antigen Retrieval 20 min at 100 °C, 3) 1.0 ug/ml Proteinase K treatment for 15 min. After taking the tissue slide off the Leica automation platform, tissue slides were incubated with GeoMx WTA (Whole Transcriptome Atlas) assay probe cocktail overnight. The following day, the tissue slides were washed and stained with morphology markers (panCK, CD45, CD68 and DNA) before loading onto GeoMx machine. On the GeoMx machine, the tissue slides are scanned. ROI selection of inflammatory lung regions of influenza only, Aspergillus only and IAPA infected mice was performed in conjunction with a pathologist based on immunohistochemistry markers and consecutive tissue slides with H&E and GMS stainings (Supplementary Figure S4). Subsequently, barcodes were collected with Serial UV illumination and barcoding reading were finished on Illumina NGS platform. The data was processed and filtered for quality. FASTQ files for each ROI were demultiplexed and converted to digital count conversion (DCC) files using the GeoMx NGS Pipeline (version 2.3.4) application. Subsequently, DCCs were transferred to the GeoMx DSP Data Analysis Suite. A Q3 normalization was performed. Differential expression between Aspergillus only and IAPA & influenza only and IAPA inflammatory infiltrates ROIs were investigated using a non-paired t-test. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were plotted using EnhancedVolcano R package [Log2FC = 0.58 and p < 0.05]. In addition, a gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) with Reactome pathway analysis was performed. Correction for multiple testing was performed for pathway analysis using Benjamini-Hochberg method [q < 0.05 = Padj <0.05]. For the Volcano plot displaying the transcriptional signatures at the individual gene level, we chose to not adjust p-values for multiple testing. This decision was driven by our interest in exploring specific genes of interest and visualizing their expression patterns without imposing overly stringent corrections. Conversely, in the pathway analysis we opted for p-adjusted values. Pathway analyses entail evaluating coordinated expression patterns across multiple genes within biological pathways, and adjusting p-values becomes essential in this context to mitigate false positives and ensure the reliability of reported associations. Acknowledging the absence of multiple testing correction in the volcano plot, we recognize this as a consequence of prioritizing exploration at the individual gene level, considering the inherent limitations in statistical power associated with our sample size.

Phagocytosis and killing assay of A. fumigatus in BALF

Four days after influenza infection, BALF was collected and resuspended in complete RPMI culture medium (ThermoFisher Scientific). 1x105 cells from BALF were plated on a Nunclon delta surface 96 well plate (ThermoFisher Scientific) and allowed to adhere overnight followed by stimulation with conidia of a red-shifted thermostable firefly luciferase A. fumigatus (CBS133.89) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1:1, at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. One hour after infection, medium which contains the non-phagocytosed spores was collected, plated on Sabouraud agar plates and colony forming unit (CFU) counting was performed after 48 h incubation at 37 °C. BAL cells were then allowed to kill conidia for 2 h and 6 h before intracellular conidia were harvested by using Triton X-100 (ThermoFisher) and plated on Sabouraud agar plates. After 48 h incubation at 37 °C, CFUs were counted.

Killing assay of A. fumigatus in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs)

BMDM were generated from bone marrow cells obtained by healthy control and influenza infected mice in DMEM (ThermoFisher Scientific), supplemented with L929 cell-conditioned medium (30%) for 6 days. After differentiation, BMDMs were harvested and counted. BMDMs (1 Χ 105 per well) were resuspended in DMEM complete medium (supplemented with 10% FBS (Tico Europe, Amstelveen, Netherlands), 1% Pen/Strep (Gibco), 1% sodium pyruvate (Gibco)), allowed to adhere in 96-well flat bottom plates (Nunc™, Cat. No 167008) for 1 h, and subsequently infected with the indicated wild type A. fumigatus strain (ATCC46645) at a MOI of 1:10 (target: effector) at 37 °C. At 1 h of infection, cells were extensively washed with warm media to remove extracellular conidia. BMDMs were allowed to kill conidia for the indicated time points (1 h, 6 h) before intracellular conidia were harvested by sonication in 100 μl of 1X PBS (3 × 1 sec, Qsonica Sonicator Q55, amplitude:40, probe: 2 mm). Intracellular conidia were allowed to germinate following supplementation with 100 μl 2x RPMI. After confirmation of germination, the 96-well plate was transferred to the Nikon Ti-2 microscope (Tokyo, Japan) with an Andor Dragonfly 200 spinning disk confocal microscope system (Andor, Oxford instruments, Belfast, UK) for imaging. Fungal killing was calculated based on the percentage of inhibition of fungal growth determined by microscopic analysis of the presence of conidia and hyphae.

Fluorescent labelling of Aspergillus

For FITC labelling, Δpksp A. fumigatus ATCC46645 mutant were collected, diluted in NaHCO3 (Fluka) 0.1 M pH 9.3 and incubated with FITC (final concentration in DMSO, 0.1 mg/ml and 0.05 mg/ml respectively, F7250 Sigma) overnight at 4 °C and washed by centrifugation three times in PBS (ThermoFisher Scientific).

Immunofluorescence staining for LC3

BMDM or BAL cells (200 000 cells) were plated on poly-l-lysine (Sigma) treated coverslips and infected with FITC-labelled Δpksp Aspergillus ATCC46645 for 30 min or 1 h at a MOI of 2:1. Guided by recent research indicating that melanin in the Aspergillus cell wall impedes LC3-associated phagocytosis and enhances pathogenicity, we selected the albino ΔpksP ATCC46645 Aspergillus mutant as a model bioparticle for LAP experiments,18 although an effect of strain difference cannot be completely ruled out. Cells were fixed with methanol (Applichem) and, after three washes with PBS, cells were blocked for 1 h with blocking buffer (1x PBS, 5% normal goat serum (Gibco), 0,3% Triton X100 (Sigma)). After blocking, cells were incubated O/N at 4 °C with the primary antibody (LC3 AB, #4108, Cell Signaling), washed 3x with PBS and stained by the appropriate secondary antibody (Biotium CF555 Goat anti-Rabbit) for 1 h, RT. After washing, coverslips were mounted in Mowiol mounting medium. Acquisition of images was performed on a Nikon Ti-2 microscope (Tokyo, Japan) with an Andor Dragonfly 200 spinning disk confocal microscope system (Andor, Oxford instruments, Belfast, UK), equipped with four excitation lasers (405, 488, 561, and 637 nm), controlled by the Fusion software. All the images were acquired and images were taken with a Plan-Apo 60×, 1.4 NA Nikon oil immersion objective and a Sona 4.2B-6 USB DFly2 Back-illuminated sCMOS camera. The percentages of LC3- associated phagosomes were quantified by measuring the number of LC3+ phagosomes out of the total number of engulfed Aspergillus conidia. More specifically: %LC3+ phagosomes = number of LC3+ phagosomes colocalized with Aspergillus conidia/total number of phagosomes containing Aspergillus conidia).

Live imaging and ROS measurement for determination of total ROS production within BMDMs

BMDM (105) were plated in a 96-well plate and infected with DHR-123-labelled ΔpksP Aspergillus (ATCC46645) with a MOI of [2:1]. Immediately after infection, the 96-well plate was transferred to the Nikon Ti-2 microscope (Tokyo, Japan) with an Andor Dragonfly 200 spinning disk confocal microscope system (Andor, Oxford instruments, Belfast, UK), equipped with four excitation lasers (405, 488, 561, and 637 nm), controlled by the Fusion software for live imaging. All the images were acquired and images were taken with a Plan-Apo 60X, 1.4 NA Nikon oil immersion objective and a Sona 4.2B-6 USB DFly2 Back-illuminated sCMOS camera. After 0 h and 2 h imaging, mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of DHR-123 was measured by using ImageJ software.

Statistics

Statistics were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 8.1.2, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Longitudinal data were analyzed with repeated measures two-way ANOVA (day 0—day 7, factors: time and experimental group). Endpoint data was analyzed with one-way ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis with a hypothesis correction on day 7, and an unpaired t-test or Mann–Whitney test on day 4 depending of the result of the normality test (Shapiro–Wilk test). For correlations, Spearman's correlation test was used. For spatial transcriptomics pathway analysis, a gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed and p-value adjustment were obtained using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. For the Volcano plot we used a non-paired t-test. Log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test was used for analyzing survival curve. All graphs represent mean values ± SD. Significant differences are indicated and reflect in the p-values reported in the graph. n values represent the number of mice. Specific statistical tests used for each measurement were included in the figure legend.

Role of funders

Funders had no role in study design, data collection, analyses, interpretation, or writing of report.

Results

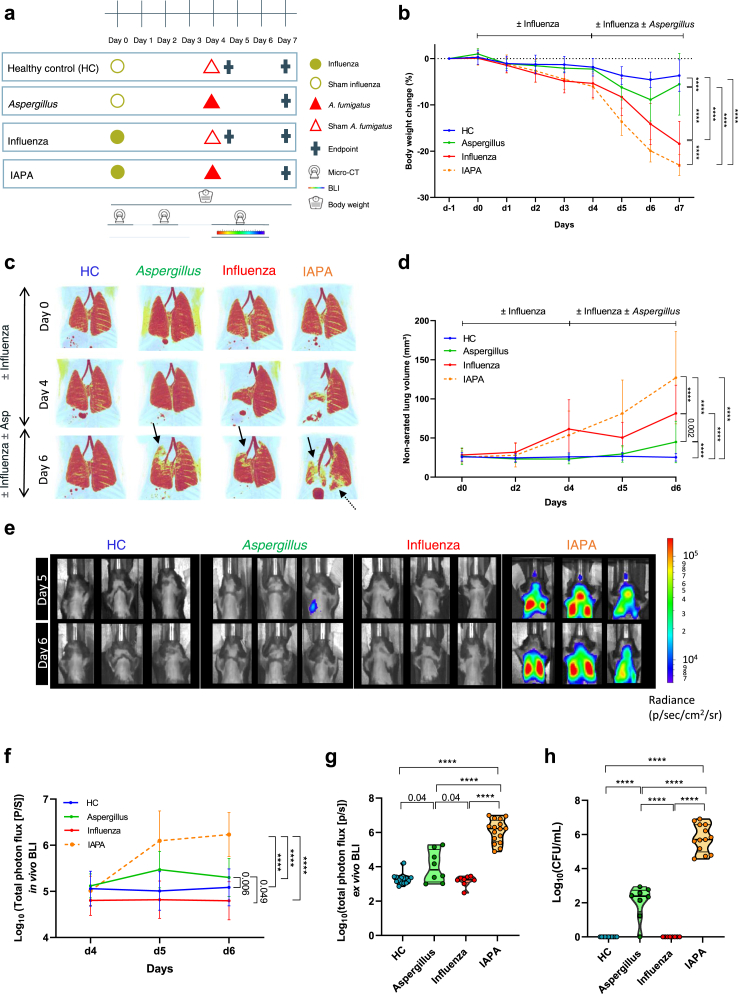

IAPA mice have severe pneumonia and invasive fungal burden compared to single infection controls

To investigate the effect of severe influenza on the antifungal host immune response at the day of and during the superinfection, we longitudinally performed a morphological and immunological profiling of the lung and BALF in our IAPA murine model (Fig. 1a). Over time, IAPA mice presented with a severe clinical deterioration as evidenced by drastic body weight loss (Fig. 1b), clinical appearance (Supplementary Figure S5a), pulmonary lesions (Fig. 1c–d) and obvious bronchial dilation (Supplementary Figure S5b) in comparison with single infection controls. Not only were more lung lesions observed, but also the fungal burden was significantly higher in IAPA mice, both longitudinally as well as at endpoint (day 7) compared to controls (Fig. 1e–h). This higher fungal burden was confirmed with histopathology showing invasive hyphal growth in IAPA mice (Supplementary Figure S5c). Mice infected with only Aspergillus showed an increased fungal burden compared to influenza only and healthy control (HC) and histopathology confirmed the presence of Aspergillus conidia (Fig. 1f–h, Supplementary Figure S5c). Thus, IAPA mice have progressively worse pulmonary lesions and fungal burden compared to single infection controls.

Fig. 1.

Influenza predisposes mice to invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. (a) Experimental design of the longitudinal morphological and immunological profiling of the IAPA murine model. The experimental setup compares four different conditions (Healthy control (HC), Aspergillus only, influenza only and IAPA (influenza—Aspergillus)) in which healthy mice received a challenge with a mouse-adapted H3N2 influenza virus or sham (PBS) on day 0 and a second hit with A. fumigatus or sham (PBS) on day 4. During the experiment we longitudinally assessed lung pathology with micro-computed tomography (μCT), fungal burden with bioluminescence imaging (BLI) and body weight. Sacrifice was performed at predefined endpoints, day 4 (before A. fumigatus instillation) and day 7. (b) Relative body weight change (%) over the course of the experiment of HC (n = 26), Aspergillus only (n = 11), influenza only (n = 21) and IAPA mice (n = 32). (c) μCT derived longitudinal three-dimensional visualization of pulmonary lung lesions. Red: healthy lung tissue (aerated lung volume), Black arrows point to examples of pulmonary infiltrates and bronchial dilation. (d) Graph represents quantification of the μCT derived biomarker non-aerated lung volume (marker for pulmonary lesions) of HC (n = 20), Aspergillus only (n = 11), influenza only (n = 21), and IAPA mice (n = 26). (e–f) Longitudinal in vivo visualization (bioluminescence images, n = 3 per group shown) and quantification (total photon flux) of the fungal burden in the lungs of HC (n = 26), Aspergillus only (n = 11), influenza only (n = 21) and IAPA mice (n = 32). (g) Endpoint (day 7) measurement of fungal burden with ex vivo bioluminescence imaging on lung homogenates of HC (n = 14), Aspergillus only (n = 8), influenza only (n = 8) and IAPA mice (n = 16). (h) Endpoint (day 7) measurement of fungal burden with colony forming unit (CFU) count on lung homogenates of HC (n = 11), Aspergillus only (n = 8), influenza only (n = 8) and IAPA mice (n = 13). Significant differences are indicated and reflect in the p-values reported in the graph. n values represent the number of mice. Longitudinal data is represented as mean ± SD, violin plots show median with quartiles. Experiments were repeated at least three times. For the longitudinal data, statistical analysis was conducted using a repeated measures two-way ANOVA. For the endpoint data collected on day 7, a one-way ANOVA was employed, followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test for post-hoc analysis.

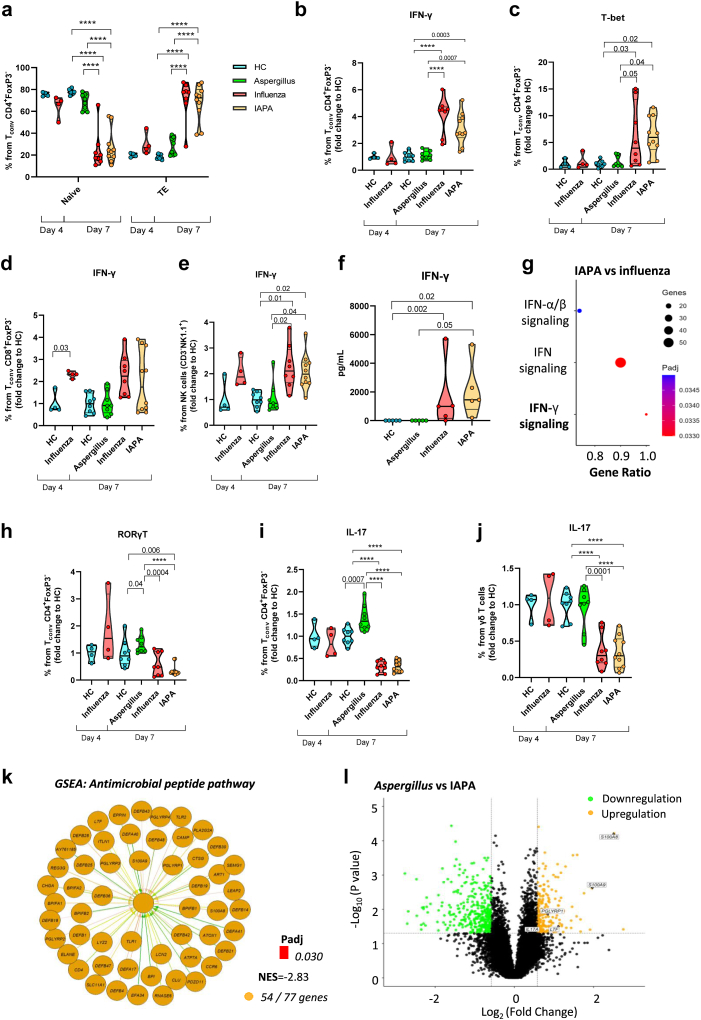

IAPA and influenza mice show extensive T-cell activation with abundant viral-induced IFN-γ production in CD4+ T cells and NK cells

In the lungs of influenza-infected mice (influenza only and IAPA) we observed an extensive T cell activation with increased CD4+ effector T cells as evidenced by elevated levels of CD25, CD69, Ki-67, CTLA-4 and PD-1 at endpoint day 7 (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Figure S6a-f). These were not present at the point of superinfection (day 4). This CD4+ T cell activation was characterized by an aberrant production of IFN-γ and expression of the transcription factor T-bet in the lungs of influenza-infected mice (influenza only and IAPA) in comparison with mice infected only with Aspergillus (Fig. 2b–c, Supplementary Figure S7a-c). In contrast, at day 4 there was a clear induction of CD8+ T cells and natural killer (NK) cells expressing IFN-γ in influenza-infected mice (influenza only and IAPA), which was still present at day 7 (Fig. 2d–e, Supplementary Figure S7d-g). We confirmed increased IFN-γ and CXCL9 (chemokine induced by IFN-γ) protein levels in BALF of influenza and IAPA mice on day 7 (Fig. 2f, Supplementary Figure S8a and b). This IFN-γ signature was also observed with spatial transcriptomics of the lung showing a major upregulation of the IFN-γ signaling pathway at day 7 (CAMK2D, CAMK2A, CAMK2B, CAMK2G, SOCS3, SOCS1, PTPN6, IFNG, IFNGR1, IFNGR2, JAK2, PRKCD, PTPN2, SUMO1, PIAS1) (Fig. 2g). In addition to the upregulation of the IFN-γ signaling pathway on day 7 we observed upregulation of the IFN-α/β and IFN-λ signaling pathway (Fig. 2g) and confirmed the presence of heightened levels of IFN-α and IFN-λ proteins in BALF of IAPA infected mice on day 7 (Supplementary Figure S8c and d). Furthermore, increased numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were found in mice infected only with influenza compared to healthy control mice, as well as a significant increase in NK cells in both influenza and IAPA mice on day 7 (Supplementary Figure S7a, d, f). Together, these results point towards an influenza-induced T-helper 1 (Th1) immune response hallmarked by an early extensive IFN-γ production in CD8+ T cells and NK cells, and in a later stage CD4+ T cells. Interestingly, this later stage of dominant Th1 response is not seen in Aspergillus only infected mice.

Fig. 2.

Extensive T cell activation and IFN-γ production but inhibition of Th17-mediated antifungal host response upon influenza infection. Violin plot showing the % (a) naïve and effector T cells (TE) from Tconv CD4+FoxP3- cells in the lung homogenates of healthy control (HC) (n = 4) and influenza only (n = 4) infected mice on day 4 and HC (n = 8), Aspergillus only (n = 8), influenza only (n = 8) and IAPA (n = 10) infected mice on day 7 assessed by flow cytometry. Percentage of IFN-γ & T-bet production by CD4+ T cells (b–c), CD8+ T cells (d) and NK cells (e) normalized to HC mice in the lung homogenates of HC (n = 4) and influenza only (n = 4) infected mice on day 4 and HC (n = 8), Aspergillus only (n = 8), influenza only (n = 8) and IAPA (n = 10) infected mice on day 7 assessed by flow cytometry. (f) IFN-γ protein levels in BALF on day 7 of healthy control (HC, n = 5), Aspergillus only (n = 5), influenza only (n = 5) and IAPA (n = 5) infected mice on day 7 assessed with a multiplex immunoassay (quantitative measurement of cytokines in pg/mL, OLINK). (g) Dot plot shows gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) with upregulated Reactome pathways in lung of IAPA vs influenza only infected mice determined by spatial transcriptomics of the inflammatory lung regions. Violin plot showing the % RORγt (h) and IL-17 from CD4+ T cells (i) and γδ T cells (j) normalized to healthy control (HC) mice in the lung homogenates of HC (n = 4) and influenza only (n = 4) infected mice on day 4 and HC (n = 8), Aspergillus only (n = 8), influenza only (n = 8) and IAPA (n = 10) infected mice on day 7 assessed by flow cytometry. (k) Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) showing downregulated antimicrobial peptide Reactome pathway in inflammatory infiltrates of IAPA vs Aspergillus only infected mice. Padj = adjusted p-value, NES = normalized enrichment score represents the degree to which a gene set is overrepresented at the top or bottom of a ranked list of genes. In the context of our analysis, a negative NES in comparison between IAPA and Aspergillus only infected mice suggests that the genes associated with the antimicrobial peptide pathway are enriched towards the bottom of the ranked list, indicating downregulation of the pathway and 54/77 genes indicating pathway coverage determined by spatial transcriptomics of the inflammatory lung regions. (i) Volcano plot showing up and downregulated differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (orange (up in Aspergillus, down in IAPA) and green (down in Aspergillus, up in IAPA) dots) related to antimicrobial peptides in Aspergillus vs IAPA determined with spatial transcriptomics of the inflammatory lung infiltrates. Significant differences are indicated and reflect in the p-values reported in the graph. n values represent the number of mice. Violin plots show median with quartiles. Measurement on day 4 were performed once while day 7 measurements were repeated at least twice. For data on day 4 a Mann–Whitney test was performed, while for data on day 7 we used a one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test for post-hoc analysis (a, b, c, h, i, j) or a Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple comparisons test (e,f). For spatial transcriptomics pathway analysis (k,g), a gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed and p-value adjustment were obtained using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. Differential expression between Aspergillus only and IAPA were investigated using a non-paired t-test (l).

Influenza inhibits Th17 mediated antifungal host response

Besides boosting the immune system by inducing a high viral Th1 immune response, influenza caused defects in T helper 17 (Th17) lymphocyte-mediated immunity in IAPA. We observed significantly increased RORγt and IL-17 production in CD4+ T cells in the lungs of Aspergillus only infected mice (Fig. 2h–i). In sharp contrast, influenza-infected mice (influenza only and IAPA) showed a significant reduction of RORγt and IL-17 in CD4+ (Fig. 2h–i, Supplementary Figure S7a, Supplementary Figure S7h and i) and γδ T cells (Fig. 2j, Supplementary Figure S7j and k) while total levels of IL-17 in BALF were increased in IAPA compared to HC (Supplementary Figure S8e-g). Spatial transcriptomics analysis of the lung in IAPA mice revealed a significant downregulation of the antimicrobial peptide pathway in comparison with Aspergillus infected mice (Fig. 2k). Differentially expressed genes in Aspergillus vs IAPA infected mice confirmed the downregulation of IL-17 as well as important genes in the antimicrobial peptide pathway in IAPA (Fig. 2l). All together, these findings indicate that primary influenza infection attenuates Th17 antifungal immunity in IAPA.

Influenza-induced depletion and functional impairment of macrophages facilitates IAPA

Next, we focused on the effect of influenza on the innate immunity, where phagocytes are the key orchestrators of the host-immune response against Aspergillus. We observed a severe depletion of alveolar macrophages in influenza-infected mice (influenza and IAPA) on day 7 post viral infection in both lung and BALF (Fig. 3a–b). Significant reduction of alveolar macrophages in influenza infected mice was already observed on day 4 (the day of superinfection) (Fig. 3b). Influenza infection can thus lead to a net reduction in the number of alveolar macrophages which play a significant role in antifungal host defense.

Fig. 3.

Influenza-induced depletion and functional impairment of alveolar macrophages. (a–b) Violin plot showing % single live cells and absolute count normalized to healthy control (HC) of alveolar macrophages present in lung homogenates (a) and BALF (b) of HC (lung n = 4, BALF n = 8) and influenza only (lung n = 4, BALF n = 8) infected mice on day 4 and HC (lung n = 11, BALF n = 8), Aspergillus only (lung n = 8, BALF n = 11), influenza only (lung n = 8, BALF n = 13) and IAPA (lung n = 13, BALF n = 14) infected mice on day 7 measured by flow cytometry. (c) Grocott's methenamine silver staining of left lung from Aspergillus only and IAPA infected mice on day 7 post viral infection. Blue box indicating Aspergillus conidia and red box indicating Aspergillus hyphae. (d) Violin plot showing % phagocytosis of Aspergillus (CBS133.89) observed in BALF of HC (n = 7) and influenza only (n = 7) infected mice on day 4. Dots represent individual mice from at least two independent experiments. (e) Violin plot showing % of CD163 from alveolar macrophages after ex vivo LPS stimulation normalized to HC mice in lung homogenates of HC (n = 4) and influenza only (n = 4) infected mice on day 4 and HC (n = 7), Aspergillus only (n = 4), influenza only (n = 4) and IAPA mice (n = 8) infected mice on day 7 measured by flow cytometry. (f) Violin plot showing % killing after 2 h and 6 h of Aspergillus (CBS133.89) in BALF of healthy control (n = 7) and influenza only (n = 7) infected mice on day 4. Dots represent individual mice from at least two independent experiments. (g) Violin plot showing % killing of Aspergillus (ATCC) in BMDM on day 4 of HC (n = 6) and influenza only infected mice (n = 5) after 1 h and 6 h of Aspergillus (ATCC). Dots represent individual mice from 2 independent experiments. Significant differences are indicated and reflect in the p-values reported in the graph. n values represent the number of mice. Violin plots shows median with quartiles. Flow cytometry measurement of % and absolute count of alveolar macrophages on day 4 in the lung were performed once (a) while day 4 measurements in BALF (b) and day 7 measurements in lung and BALF were repeated at least twice. At least two independent repeats were performed for killing and phagocytosis assays. For data on day 4 an unpaired t test (b absolute count), Mann–Whitney test (b %single cell, d) or two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test (f,g) was performed while for data on day 7 we used a one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test for post-hoc analysis (a absolute count, e) or a Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple comparisons test (a single cell, b).

To determine whether influenza also leads to functional impairment of macrophages, we investigated whether influenza could induce defects in phagocytosis and killing of Aspergillus conidia. Histopathological examination revealed germinating intracellular and extracellular conidia and invading hyphae in IAPA mice (Fig. 3c). These persistent conidia and intracellular germinating hyphae suggest defects in phagocytosis and killing, respectively, in IAPA mice. In Aspergillus single infected mice, only occasional intracellular dormant conidia were found (Fig. 3c). Indeed, we found an overall decreased capacity of pulmonary phagocytes recovered from BALF to phagocytose Aspergillus conidia 4 days after influenza infection (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Figure S9a) and observed significantly lower numbers of alveolar macrophages expressing the scavenging receptor CD163 important for phagocytosis (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Figure S9b). In addition, we observed a major downregulation of VASP (a gene that encodes a protein involved in actin polymerization, which plays a role in phagocytosis and the lateral transfer of Aspergillus conidia between macrophages19) in IAPA mice in comparison with Aspergillus only infected mice with spatial transcriptomics in the lung (Aspergillus only vs IAPA: log2 fold change = 1.05; −log10 p value = 1.75) (Supplementary Figure S10). Moreover, we confirmed the killing deficit on the day of the superinfection in pulmonary phagocytes from BALF and in BMDM cultivated from influenza-infected mice (Fig. 3f–g, Supplementary Figure S9c). These results indicated both local and systemic defects in anti-fungal immunity. Together these data suggest that influenza not only depletes alveolar macrophages but also impairs the phagocytosis and the killing capacity of the remaining phagocytes in BALF and BMDMs against Aspergillus.

Defective NADPH oxidase-dependent activation of the LAP pathway in macrophages induced by influenza

Lung-resident macrophages comprise a crucial arm of cellular immunity against Aspergillus. NADPH oxidase-dependent activation of LAP regulates killing of Aspergillus conidia. Accordingly, genetic or pharmacological inhibition of LAP results in susceptibility to invasive aspergillosis.20 Therefore, we investigated the mechanism of the influenza-induced macrophage defect in Aspergillus killing by exploring whether LAP is impaired in IAPA. In the spatial transcriptomics analysis of the lung in IAPA mice, we observed a major downregulation of the pathways related to NADPH oxidase activation, ROS production and ROS detoxification (Fig. 4a). Specifically, we found a downregulation of NCF1 and NCF4, genes encoding the cytosolic subunit of respectively p47-phox and p40-phox of the NADPH-oxidase complex (Fig. 4a). Importantly, functional studies confirmed the defect in total phagosomal ROS production in BMDMs and pulmonary phagocytes in the BALF in influenza infected mice on day 4 and 7 of infection, respectively (Fig. 4b–c). However, we did not observe defects in ROS production specifically by residual alveolar macrophages in BALF of influenza-infected mice both on day 4 and day 7 (Fig. 4d). Because NADPH-dependent ROS production is a master regulator of LAP, we investigated whether this pathway is inhibited by influenza infection.21 We found significantly less LC3+ phagosomes (LAPosomes) in BMDM and pulmonary phagocytes in the BALF from influenza infected mice on day 4 after ex vivo infection with Aspergillus (Fig. 4e–h), thereby confirming an influenza-induced LAP defect that is associated with the defective fungal killing of macrophages in IAPA.

Fig. 4.

Defective activation of LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP) upon influenza infection. (a) Chord plot showing downregulated reactome pathways linked to the downregulated differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for IAPA vs. Aspergillus in the lung on day 7. Log2FC = Log2 Fold change, Padj = adjusted p-value determined by spatial transcriptomics of the inflammatory lung regions. Downregulated reactome pathways were determined via reactome pathway analysis using an adjusted p-value threshold of <0.05 and downregulated differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were selected based on p-value <0.05 and log2 fold change >0.58. (b) Violin plot showing mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of DHR in BMDM on day 4 after 0 or 2 h infection with Aspergillus (Δpksp ATCC) from HC (n = 4) and influenza infected mice (n = 4) (total ROS) (c) Violin plot showing mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of DHR in BAL on day 7 after 2 h infection with Aspergillus (ATCC) from HC (n = 4) and influenza infected mice (n = 4) (total ROS). (d) Violin plot showing geometric mean fluorescence intensity of ROS normalized to HC in alveolar macrophages in BALF of HC (n = 4) and influenza only (n = 4) on day 4 and HC (n = 8), Aspergillus only (n = 8), influenza only (n = 8) and IAPA mice (n = 10) on day 7 assessed by flow cytometry. (e) Violin plot showing LC3+ phagosomes in BMDM of HC (n = 10) and influenza infected (n = 11) mice after 30 min infection with Aspergillus (Δpksp ATCC).(f) Violin plot showing LC3+ phagosomes in BMDM of HC (n = 2) and influenza infected (n = 3) mice after 1 h infection with Aspergillus (Δpksp ATCC).(g) Violin plot showing LC3+ phagosomes in BALF of HC (n = 3) and influenza infected (n = 3) mice after 6 h infection with Aspergillus (Δpksp ATCC).(h) Microscopic images of LC3 (green) and Δpksp (pink) in BMDM from HC and influenza infected mice on day 4 after 30 min and 1 h infection with Aspergillus. Significant differences are indicated and reflect in the p-values reported in the graph. n values represent the number of mice. Violin plots show median with quartiles. Total ROS in BMDM and BALF (b,c), ROS production by macrophages on day 4 (d) and LC3+ phagosomes in BMDM after 1 h (f) and BALF after 6 h were measured once. ROS production by macrophages on day 7 (d) and LC3+ phagosomes in BMDM after 30 min (e) were measured at least twice. For measurements on day 4 a two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test (b) or an unpaired t-test (e,g) was used. For measurement on day 7 an unpaired t-test (c), one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test for post-hoc analysis (d) was performed. For spatial transcriptomics pathway analysis (a), a gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed and p-value adjustment were obtained using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. Differential expression between Aspergillus only and IAPA were investigated using a non-paired t-test.

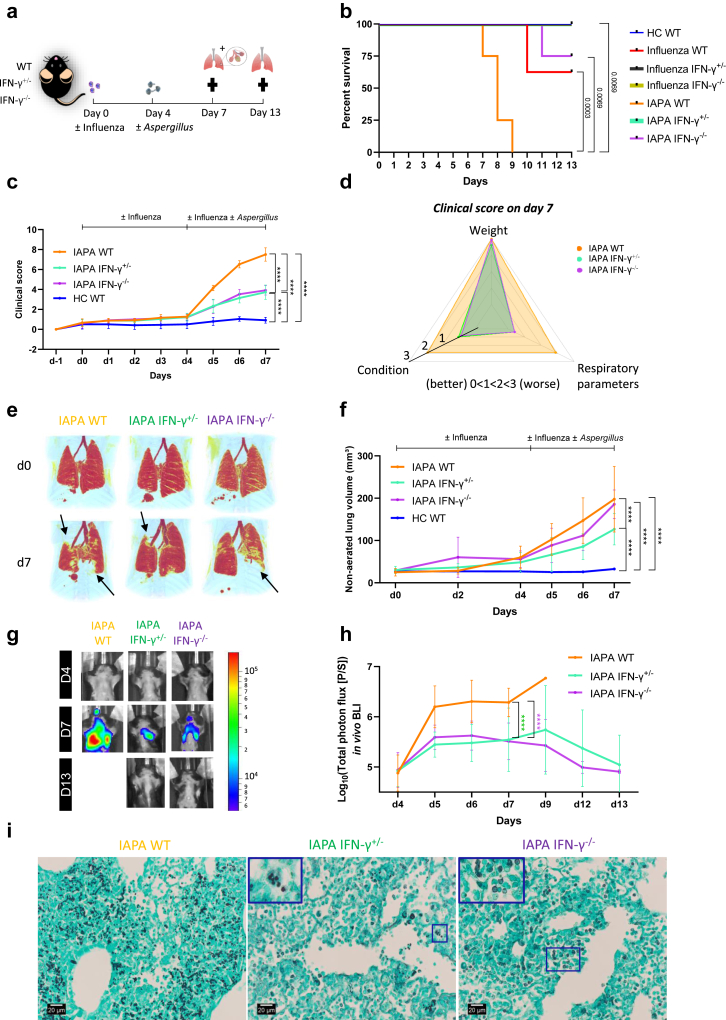

High viral-induced IFN-γ is detrimental and drives IAPA

To investigate whether the uncontrolled production of IFN-γ during influenza impairs the protective macrophage, LAP, and Th17 antifungal host immune response, we employed a genetic strategy. Specifically, we assessed the impact of IFN-γ dosing by utilizing IAPA-infected mice heterozygous (IFN-γ+/−) or homozygous (IFN-γ−/−) for the Ifng knockout allele (Fig. 5a). Mice infected with IAPA and influenza, possessing IFN-γ+/− and IFN-γ−/− genotypes, displayed a clear dose response in IFN-γ production: homozygous mice exhibited very low levels, heterozygous mice displayed intermediate levels, and wild-type (WT) mice showed very high levels of IFN-γ thus providing a model for understanding the impact of IFN-γ dosage on the susceptibility to develop IPA (Supplementary Figure S11a-c). We found a significant increase in survival rates and improvement on clinical appearance (respiratory parameters & condition) in IAPA IFN-γ+/− and IFN-γ−/− compared to IAPA WT mice (Fig. 5b–d). In addition, IFN-γ+/− IAPA mice presented with significantly fewer pulmonary lesions towards 7 days post viral infection in comparison with IAPA WT mice (Fig. 5e–f). No differences in clinical appearance or pulmonary pathology were found between influenza only infected WT, IFN-γ+/− and IFN-γ−/− mice (Supplementary Figure S12a and b). In addition, no difference in viral load at the time of the superinfection (day 4) and day 7 were found indicating that IFN-γ+/− and IFN-γ−/− mice are not inherently less susceptible to influenza than their WT counterparts (Supplementary Figure S13a and b). Besides the increased probability of survival and improved clinical appearance, IAPA IFN-γ+/− and IFN-γ−/− mice exhibited a significantly reduced fungal burden in the lung both longitudinally as well as at endpoint day 7 compared to IAPA WT mice (Fig. 5g–h, Supplementary Figure S14a-c). This lower fungal burden was confirmed by histopathology showing invasive hyphal growth in WT IAPA mice while IFN-γ+/− and IFN-γ−/− presented with very few (mostly intracellular) or no conidia (Fig. 5i). Furthermore, we observed epithelial damage/necrosis in all IAPA WT mice by day 7 (Fig. 6). In contrast, IAPA IFN-γ+/− and IFN-γ−/− mice only displayed epithelial activation without necrosis by day 7, transitioning to a restoration phase by day 13, characterized by clear reepithelization (Fig. 6). Thus, mice with partial or complete genetic ablation of IFN-γ were fully protected against the development of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis after primary influenza infection.

Fig. 5.

Absent or reduced viral-induced IFN-γ protects mice from invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in IAPA. (a) Experimental design of IAPA murine model using WT, IFN-γ+/− and IFN-γ−/− mice. (b) Survival curve of healthy control (HC) WT (n = 4), influenza only WT (n = 8), influenza only IFN-γ+/− (n = 4), influenza only IFN-γ−/− (n = 4), IAPA WT (n = 4), IAPA IFN-γ+/− (n = 4), IAPA IFN-γ−/− (n = 4) infected mice. (c) Longitudinal observation of the clinical score (including condition, respiratory parameter and body weight) of IAPA WT (n = 12), IFN-γ+/− (n = 12), IFN-γ−/− (n = 12) and HC WT mice (n = 12). (d) Clinical score on day 7 of IAPA WT (n = 12), IFN-γ+/− (n = 12), IFN-γ−/− (n = 12) represented as a radar graph. This clinical score is derived from the assessment of three parameters: body weight, condition, and respiratory parameters. Each parameter is graded on a scale from 0 to 3, with zero indicating no effect and 3 indicating the most severe effect. The radar graph provides a visual representation of the distribution of scores for each parameter. (e) Longitudinal three-dimensional visualization of pulmonary lung lesions in IAPA WT, IFN-γ+/− and IFN-γ−/−. Red: healthy lung tissue (aerated lung volume), Black arrows point to examples of pulmonary infiltrates. (f) Longitudinal non-aerated lung volume (pulmonary lesions) in IAPA WT (n = 12), IFN-γ+/− (n = 12), IFN-γ−/− (n = 12) and HC WT mice (n = 12). (g–h) Longitudinal in vivo visualization (bioluminescence images) (g) and quantification (total photon flux) (h) of the fungal burden in the lungs of IAPA WT (n = 12), IFN-γ+/− (n = 12) and IFN-γ−/− (n = 12) infected mice. (i) Grocott's methenamine silver staining of left lung on day 7 post viral infection from IAPA WT, IFN-γ+/− and IFN-γ−/− infected mice. Significant differences are indicated and reflect in the p-values reported in the graph. n values represent the number of mice. Longitudinal data is represented as mean ± SD. Violin plots show median with quartiles. Experiments were repeated at least twice. For the longitudinal data, statistical analysis was conducted using a repeated measures two-way ANOVA. Log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test was used for analyzing the survival curve.

Fig. 6.

Partial or complete genetic ablation of IFN-γ prevent epithelial necrosis in IAPA. (a) Histopathological observation of epithelial necrosis and activation in IAPA WT (n = 4), IFN γ+/− (n = 4) and IFN γ−/− (n = 4). (b) Histopathological observation of epithelial necrosis, activation and re-epithelialization in IAPA IFN γ+/− (n = 4) and IFN γ−/− (n = 4) on day 13. (c) Histopathological images of IAPA WT (day 7), IFN γ+/− (day 13) and IFN γ−/− (day 13).

Restoration of dysfunctional antifungal effector responses of IAPA in IFN-γ+/− and IFN-γ−/− mice

To further investigate whether uncontrolled production of IFN-γ after influenza infection causes potential cellular and functional defects in the immune response against Aspergillus, we performed an immune profiling of BALF fluid and lung homogenates in WT, IFN-γ+/− and IFN-γ−/− mice at day 7. We found significantly more alveolar macrophages in the lung and BALF of IAPA IFN-γ+/− and IFN-γ−/− mice in comparison with WT mice (Fig. 7a,c). This higher number of alveolar macrophages strongly correlated with a lower fungal burden (Fig. 7 b,d). In addition, we observed an enhanced ROS production in alveolar macrophages of influenza and IAPA IFN-γ−/− mice compared to respectively influenza and IAPA WT mice (Fig. 7e, Supplementary Figure S15a). Furthermore, we found significantly more CD163+ macrophages (important for phagocytosis) in IAPA IFN-γ+/− and IFN-γ−/− mice compared to WT, which moderately correlated with lower fungal burden (Fig. 7f–g, Supplementary Figure S16a). The %CD163+ macrophages in IAPA IFN-γ−/− and IFN-γ+/− mice was comparable or even higher than Aspergillus only infected mice (Supplementary Figure S15b). Similar to our observations in the IAPA infection group, we found a higher number of CD163+ alveolar macrophages in influenza infected IFN-γ−/− and IFN-γ+/− mice (Fig. 7f, Supplementary Figure S16b).

Fig. 7.

Absence or lower viral induced IFN-γ restores cellular and functional immunity against Aspergillus. (a–c) Violin plot showing absolute count of alveolar macrophages in BALF (a) and lung (c) assessed by flow cytometry. (b–d) Correlation graph between absolute count of BALF (b) and lung (d) alveolar macrophages and ex vivo bioluminescence imaging (BLI) of lung homogenates (fungal burden). (e) Violin plot showing geometric mean fluorescence intensity of ROS after ex vivo Pdbu stimulation normalized to healthy control (HC) in BALF assessed by flow cytometry. (f) Violin plot showing % CD163 from alveolar macrophages normalized to HC in lung after ex vivo LPS stimulation assessed by flow cytometry. (g) Correlation graph between the % CD163 from alveolar macrophages normalized to HC and ex vivo BLI of lung homogenates (fungal burden). (h) Violin plot showing the % RORγt from CD4+FoxP3- T cells normalized to HC in lung assessed by flow cytometry. (i) Violin plot of % IL-17 from CD4+FoxP3- T cells normalized to HC in lung assessed by flow cytometry (j) Correlation graph between IL-17 from CD4+FoxP3- T cells normalized to HC and ex vivo BLI of lung homogenates (fungal burden) assessed by flow cytometry. (k) Violin plot showing % IL-22 from CD4+FoxP3- T cells normalized to HC in lung assessed by flow cytometry. (l) Violin plot showing absolute count of neutrophils in BALF assessed by flow cytometry. (m) Violin plot showing % TNF-α from CD4+FoxP3- T cells normalized to HC in the lung assessed by flow cytometry. Graphs include groups of IAPA (orange, green, purple) and influenza only infected (red, grey, yellow) WT, IFN-γ+/− and IFN-γ−/− mice. Measurements were taken on experimental endpoint day 7 post viral infection. Significant differences are indicated and reflected in the p-values reported in the graph. Dots represent individual mice (dots = number of mice (n)). Violin plots show median with quartiles. Measurements in BALF in IAPA WT, and IFN-γ−/− (a) and lung IAPA and influenza WT mice were repeated at least twice. Measurements in lung of IAPA and influenza IFN-γ+/− and IFN-γ−/− were performed once. For correlations, Spearman's correlation test was used. One-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test for post-hoc analysis (f,l,m) or Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn's multiple comparison test (a,c,e,h,i,k) was performed.

In addition to elevated macrophage number and functionality, we also observed an improved Th17 immune response in the lung of influenza infected IFN-γ−/− and IFN-γ+/− mice on day 7. We observed increased levels of RORγt and IL-17 in CD4+ T-cells of IFN-γ−/− mice with IAPA and to a lesser extent in IFN-γ+/− mice compared to WT mice with IAPA (Fig. 7 h-i, Supplementary Figure S16c and d). This increased production of IL-17 was also seen in influenza-infected IFN-γ−/− mice compared to WT mice suggesting that in the absence of IFN-γ, the mice do not develop a deficient Th17 response (Fig. 7i, Supplementary Figure S16e). Moreover, elevated IL-17 levels were found to correlate significantly, albeit moderately, with reduced fungal burden (Fig. 7j). Increased production of IL-22 in CD4+ T cells in IFN-γ−/− mice with IAPA similarly correlated with elevated IL-17 in CD4+ T cells (Fig. 7k, Supplementary Figures S15c, S16f-g). Attenuation of IFN-γ ameliorated the hyperinflammatory state in IAPA. In BALF, there were significantly fewer neutrophils in IFN-γ+/− mice with IAPA compared to WT and IFN-γ−/−mice (Fig. 7l). Lung histopathological scoring showed a shift towards lower neutrophil and higher lymphocyte scores in IFN-γ+/− and IFN-γ−/− mice with IAPA on day 7 (Supplementary Figure S15d and e). Neutrophils in IFN-γ−/− seemed to be significantly less activated as demonstrated by lower TNF-α production (Fig. 7m, Supplementary Figures S15f, S16h).

Next, we tested whether the functional responses of macrophages against Aspergillus were also restored in IFN-γ−/− and IFN-γ+/− mice at the day of the superinfection (day 4) (Fig. 8a). Importantly, we found a significant increase in ROS production, LAPosome formation and killing of Aspergillus conidia by BMDM in IFN-γ−/− and IFN-γ+/− influenza infected mice compared to WT (Fig. 8b–d, Supplementary Figure S17). Not only in BMDM but also in the remaining pulmonary phagocytes in the BALF an increased overall ability to phagocytose and kill Aspergillus, as well as increased LAPosome formation were found in influenza infected IFN-γ−/− and IFN-γ+/− mice compared to WT mice (Fig. 8e–h). Collectively, we provide evidence that points toward a significant role for elevated concentrations of IFN-γ in impairing protective macrophage, LAP and Th17 responses.

Fig. 8.

Absent or reduced viral-induced IFN-γ restores killing, ROS and LAP defect in BMDM and phagocytosis, killing & LAP defect in BALF upon influenza infection. (a) Experimental design showing influenza/sham infection in WT, IFN-γ+/− and IFN-γ−/− mice with experimental endpoint on day 4. (b–d) % Killing of Aspergillus after 6 h infection with Aspergillus (ATCC) (b), %LC3+ phagosomes after 30 min infection with Aspergillus (Δpksp ATCC) (c) and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of DHR normalized to background after 2 h infection with Aspergillus (Δpksp ATCC)(d) in BMDM on day 4 of HC WT (n = 3), HC IFN-γ+/− (n = 3), HC IFN-γ−/− (n = 2), influenza WT (n = 3), influenza IFN-γ+/− (n = 2), influenza IFN-γ−/− (n = 2). (e) % Phagocytosis of Aspergillus (CBS133.89) in BALF on day 4 in HC (n = 4), influenza WT (n = 4), influenza IFN-γ+/− (n = 4), influenza IFN-γ−/− (n = 4) mice. (f) % Killing of Aspergillus (CBS133.89) after 2 h and 6 h in BALF on day 4 in HC (n = 4), influenza WT (n = 4), influenza IFN-γ+/− (n = 4), influenza IFN-γ−/− (n = 4) mice. (g) %LC3+ phagosomes in BALF on day 4 of HC WT (n = 3), HC IFN-γ+/− (n = 3), HC IFN-γ−/− (n = 2), influenza WT (n = 3), influenza IFN-γ+/− (n = 3), influenza IFN-γ−/− (n = 2) after 6 h infection with Aspergillus (Δpksp ATCC). (h) Microscopic images of LC3 (green) and Δpksp (pink) in BALF of HC and influenza infected mice after 6 h infection with Aspergillus. Significant differences are indicated and reflect in the p-values reported in the graph. n values represent the number of mice. Violin plots show median with quartiles. Experiments were performed once. One-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test for post-hoc analysis (c,e), Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn's multiple comparison test (b,d,g) or two-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test (f) was performed.

Discussion

In this study, we longitudinally profiled the respiratory innate and adaptive antifungal immune response in a murine model of IAPA. We identified a crucial role for influenza-induced IFN-γ in impairing key antifungal effector pathways. A defective Th17 immune response, a defect in the number of alveolar macrophages and, reduced effector function of macrophages likely due to an impaired NADPH-oxidase dependent ROS activation of LAP were all observed in IAPA. Critically, these defects were fully reversed in IFN-γ deficient mice in a dose dependent manner, providing evidence that early excessive production of IFN-γ is responsible for the impaired antifungal host response observed in influenza-infected mice. We underscore the importance of a balanced IFN-γ response in the early phase of influenza and IAPA and open the door to explore the use of excessive production of IFN-γ as a biomarker and new immunotherapeutic target in IAPA.

Despite treatment options and diagnostic tools, IAPA is still associated with an unacceptably high mortality and morbidity. Host-directed immunotherapies might overcome this clinical challenge.22 To identify such host-directed immunotherapies, an improved understanding of the host-pathogen factors driving influenza- Aspergillus superinfections is ultimately required. Clinically relevant murine models of IAPA and an observational clinical study of IAPA shed a first light on the mechanisms responsible for susceptibility to IAPA. However, information on the dynamics of the host immune response during and at the time of superinfection would provide crucial insights to identify potential targets for host-directed personalized medicine approaches or for the allocation of existing immunomodulatory therapies. To map the dynamic host immune response from a morphological and immunological point of view and to provide valuable insights for a potential host-directed medicine approach, we utilized our clinically relevant imaging-supported IAPA mouse model.7,8

Immunological profiling of the respiratory system revealed extensive T cell activation with abundant viral-induced IFN-γ production, and impaired Th17 responses in influenza and IAPA mice which were not present in Aspergillus only infected mice in parallel with a better outcome compared to IAPA mice. The reduction of RORγt and IL-17 in CD4+ and γδ T cells in the lungs of IAPA and influenza-infected mice we observed is in line with prior observation of lower IL-17 A levels in the lungs of these mice 24 h post Aspergillus infection12 and a recent preprint.23 In addition, our data in IAPA mice are in line with prior observations that viral induced Th1 immune responses can dampen Th17 immunity by repressing Th17 differentiation, and that IFN-γ can inhibit IL-17 production in a STAT1 dependent manner.24, 25, 26 In our IAPA IFN-γ−/− mice, and to a lesser extent IFN-γ+/− mice, we observed an improved Th17 antifungal immune response that correlated with lower fungal burden. This improved Th17 immunity could trigger epithelial cells to produce more antimicrobial peptides for an effective antifungal defense.27 Future studies should investigate whether the enhanced Th17 immunity in IFN-γ deficient mice leads to increased antimicrobial peptide production and effective antifungal defense, thereby protecting against IAPA. In addition, IL-17 is known as a neutrophil attractant27 and we observed higher levels of neutrophils in BALF in IFN-γ−/− mice, correlating with the level of IL-17 secretion. These neutrophils are essential for the eradication of Aspergillus on the one hand, but they need to be tightly regulated in order to avoid detrimental inflammatory pathology on the other hand, which emphasizes the need for a balanced IFN-γ response.

IFN-γ plays a key role in driving an antiviral and antifungal host response in the lung. In patients and murine models of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, IFN-γ proved to be an essential cytokine for the defense against fungal infections: IFN-γ activates phagocytes and restores LAP in chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) via restoration of death-associated protein kinase 1 (DAPK1) activity.28 Interestingly, mice with a genetic ablation of IFN-γ (IFN-γ−/−) are resistant to Aspergillus infection.29 Also, in cases of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis, impaired systemic production of IFN-γ correlated with a worse outcome.30 Furthermore, a small study showed the beneficial effect of recombinant IFN-γ in increasing HLA-DR expression in patients with Candida or Aspergillus infection.31 Parallels with the role of IFN-γ can be seen in sepsis where IFN-γ restores immune deactivation of monocytes.32 However, in contrast to the protective role of IFN-γ in the antifungal host defense, IFN-γ can also drive susceptibility to fungal infections in mice and humans. In the specific case of oral mucosal fungal infections by C. albicans, an excessive production of IFN-γ impaired the viability and integrity of the epithelial barrier.33 In murine models of influenza-associated bacterial superinfections, IFN-γ led to an increased susceptibility to a secondary bacterial infection and mortality following a primary influenza infection by either depleting macrophages or a reduced phagocytic activity in BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice respectively.34, 35, 36, 37 In addition to depletion of macrophages and suppressed phagocytic activity, IFN-γ impaired Th17-mediated immunity and drove inflammatory monocyte recruitment in influenza-associated bacterial superinfections.5,38,39 Patient studies also reveal risks of detrimental innate inflammatory response as a consequence of boosting the host defense with IFN-γ.40 A recent clinical trial showed that prophylaxis with IFN-γ did not reduce incidence of hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) or death, but rather increased the incidences of HAP. The trial was rapidly discontinued due to safety concerns.41 Thus, IFN-γ balance can be a crucial driver of disease outcome.

In our study, we observed an IFN-γ-induced depletion of alveolar macrophages in both airways and the lung, 4 and 7 days after influenza infection. Findings on day 7 align with prior research, that noted reduced frequencies of alveolar macrophages in the lungs of mice infected with influenza and IAPA, as compared to those infected solely with Aspergillus, 2 days post Aspergillus infection.6 These alveolar macrophages are key effector cells responsible for clearance of inhaled conidia and apoptotic cells in the lung, limiting apoptosis-induced inflammation and invasive fungal growth. Viral induced IFN-γ triggers cell death in alveolar macrophages.34,35 Interestingly, the combination of IFN-γ and TNF-α during COVID-19 can induce PANoptosis (pyroptosis, apoptosis, necroptosis) in murine macrophages via the IRF1/STAT1 pathway and induction of iNOS and NO.42 In addition to a high IFN-γ production, we also found a high production of TNF-α by neutrophils in our IAPA mice. It may well be that in murine IAPA the synergistic effect of IFN-γ and TNF-α causes PANoptosis in alveolar macrophages, driving their loss. In our IAPA IFN-γ+/− and IFN-γ−/− mice, we reversed this IFN-γ-induced depletion of alveolar macrophages, correlating with a lower fungal burden.

Beyond major loss of alveolar macrophages, the remaining pulmonary phagocytes in mice infected with influenza on the day of superinfection exhibited reduced phagocytic function. This implies that the remaining pulmonary phagocytes are incapable of engulfing Aspergillus on the day of superinfection. Furthermore, by day 7, there were indications of an IFN-γ dependent phagocytosis defect in IAPA. In IAPA mice, notably fewer CD163+ lung alveolar macrophages were present, and VASP was downregulated as seen in human IAPA data.4,19 These findings were reversed in IAPA IFN-γ−/− and IFN-γ+/− mice correlating with a lower fungal burden. Furthermore, lung histopathology of IFN-γ−/− and IFN-γ+/− IAPA pointed towards improved phagocytosis by alveolar macrophages in contrast to WT mice with IAPA. The mechanism of phagocytosis of Aspergillus conidia in IAPA has not been explored, and the role of phagocytic receptors (such as CD163) in antifungal immunity and conidial uptake deserves to be evaluated by dedicated studies. It is worth noting that IFN-γ is known to inhibit phagocytosis by downregulating the expression of the class A scavenger receptor MARCO and the scavenger receptor CD163 on macrophages, as demonstrated in an influenza bacterial superinfection model.36,43, 44, 45 However, in vitro data did not reveal altered binding or uptake of bacteria by naïve macrophages following treatment with IFN-γ.46 Sarden et al. also observed a defect in neutrophil-mediated phagocytosis of Aspergillus conidia but during the superinfection phase. Other models of IAPA did not observe phagocytosis defects in alveolar macrophages during the superinfection phase.9,12

Pulmonary phagocytes and BMDMs exhibited reduced killing of Aspergillus at the point of superinfection. This lost killing capacity at the point of superinfection may allow the fungus to gain a foothold, leading to invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. These findings are in line with the previously observed defects in antifungal killing during the superinfection phase. Accordingly, Liu et al. showed a defective neutrophil killing due to a phagolysosomal maturation defect in influenza-infected mice 36 h post Aspergillus infection.15 However, Lee et al. did not observe a killing defect in neutrophils and alveolar macrophages during the superinfection phase.12 Differences in infection timing/experimental models (e.g. d0-d4 vs d0-d6), timing of analysis (day of the superinfection vs later time points), viral and fungal strain/load, in vivo and ex vivo analysis and variation in the extent of fungal growth could explain the observed heterogeneity.

Next, we set out to elucidate the exact mechanism for this phenotype. We looked into an important mechanism of killing of phagocytosed Aspergillus conidia via LAP, a specialized anti-inflammatory autophagic pathway that depends on the NADPH-oxidase complex to drive phagosomal ROS production. This pathway regulates Aspergillus clearance and inflammatory immune homeostasis.20 In samples from patients with IAPA, we recently reported a significant downregulation of the MAP1LC3B autophagy gene related to LAP.4 In line with the results in these patient samples, we now report a significant defect in activation of LAP in pulmonary phagocytes and BMDM, which is likely related to upstream defects in NADPH-oxidase mediated ROS production in influenza infected mice. Here we observed downregulation of NADPH oxidase and ROS pathway, specifically NCF1 and NCF4, genes which encode for the cytosolic subunit of the NADPH-oxidase. We confirmed the defect in total ROS production in BMDM and BALF. Interestingly, we did not observe a reduced ROS production specifically by the few remaining alveolar macrophages in BALF of IAPA mice, suggesting that the net reduction in ROS is due to depletion of macrophages and the other inflammatory myeloid cells are unable to compensate. The suppression of NADPH oxidase and defects in ROS production align with previous findings in influenza bacterial superinfection models.47 However, the observed influenza-induced LAP defect in IAPA has not been reported in cases of influenza bacterial superinfection. Future studies could explore whether the LAP defect is specific to IAPA.