Abstract

The transmembrane subunit (TM) of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) envelope protein contains four well-conserved sites for the attachment of N-linked carbohydrates. To study the contribution of these N-glycans to the function of TM, we systematically mutated the sites individually and in all combinations and measured the effects of each on viral replication in culture. The mutants were derived from SHIV-KB9, a simian immunodeficiency virus/HIV chimera with an envelope sequence that originated from a primary HIV-1 isolate. The attachment site mutants were generated by replacing the asparagine codon of each N-X-S/T motif with a glutamine codon. The mobilities of the variant transmembrane proteins in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis suggested that all four sites are utilized for carbohydrate attachment. Transfection of various cell lines with the resulting panel of mutant viral constructs revealed that the N-glycan attachment sites are largely dispensable for viral replication. Fourteen of the 15 mutants were replication competent, although the kinetics of replication varied depending on the mutant and the cell type. The four single mutants (g1, g2, g3, and g4) and all six double mutants (g12, g13, g14, g23, g24, and g34) replicated in both human and rhesus monkey T-cell lines, as well as in primary rhesus peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Three of the four triple mutants (g124, g134, and g234) replicated in all cell types tested. The triple mutant g123 replicated poorly in immortalized rhesus monkey T cells (221 cells) and did not replicate detectably in CEMx174 cells. However, at 3 weeks posttransfection of 221 cells, a variant of g123 emerged with a new N-glycan attachment site which compensated for the loss of sites 1, 2, and 3 and resulted in replication kinetics similar to those of the parental virus. The quadruple mutant (g1234) did not replicate in any cell line tested, and the g1234 envelope protein was nonfunctional in a quantitative cell-cell fusion assay. The synthesis and processing of the quadruple mutant envelope protein appeared similar in transient assays to those of the parental SHIV-KB9 envelope. Given their high degree of conservation, the four N-linked carbohydrate attachment sites on the external domain of gp41 are surprisingly dispensable for viral replication. The viral variants described in this report should prove useful for investigation of the contribution of carbohydrate moieties on gp41 to recognition by antibodies, shielding from antibody-mediated neutralization, and structure-function relationships.

Proteins containing amino acid motifs of the type N-X-S/T are subject to cotranslational glycosylation as they emerge from membrane-bound ribosomes (24). The envelope precursor of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), gp160, contains about 28 sites for N-linked carbohydrate attachment. After translation and oligomerization, gp160 is cleaved by a cellular protease to generate the surface (SU) and transmembrane (TM) proteins. Approximately 24 sites for N-linked glycosylation are found in the HIV type 1 (HIV-1) SU subunit (gp120), and glycosylation accounts for about 50% of this protein's mass (18). The HIV-1 TM protein, gp41, typically contains three or four sites for N-glycan attachment, located within a short stretch (20 to 30 residues) of the C-terminal half of the ectodomain (Fig. 1). There is a growing body of evidence demonstrating that N-linked glycosylation can serve to modulate the exposure of the HIV and SIV gp120 proteins to immune surveillance in patients or experimentally infected animals (2, 3, 6, 25, 29–32). For example, Reitter et al. demonstrated that SIVmac239 variants lacking specific N-linked carbohydrate attachment sites in gp120 were more sensitive to antibody-mediated neutralization and better elicitors of neutralizing antibody responses in rhesus monkeys (29). However, effects of glycosylation on the antigenicity and immunogenicity of the gp41 subunit have not been reported.

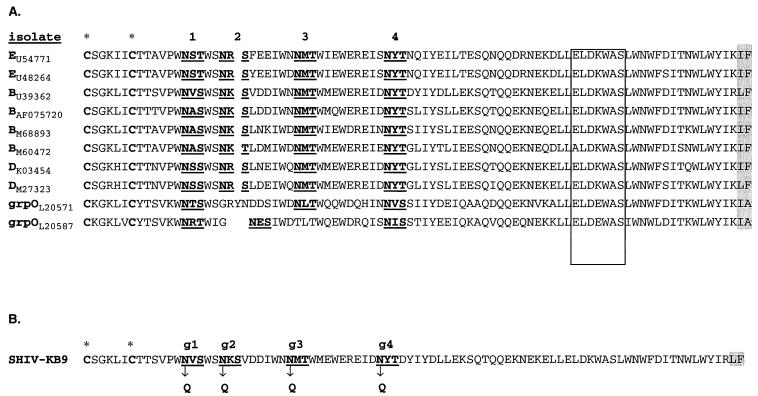

FIG. 1.

The TM proteins of HIV-1 envelopes contain three to four conserved sites for N-linked glycosylation. (A) Alignment of 10 representative HIV-1 amino acid sequences. The alignment extends from the conserved cysteine residues (boldface C) to the first two amino acids of the predicted membrane-spanning domain (grey box). Boldface capital letters at the beginning of each line indicate clades (E, B, and D) of group M; also included are two isolates of group O (grpO). Subscripts indicate the accession numbers for each sequence. Canonical carbohydrate attachment sites are indicated by boldface, underlined letters. (B) Amino acid sequence of the glycosylated region of the virus used in this study, SHIV-KB9.

The extracellular domain of gp41 consists of an amino-terminal fusion domain, N- and C-terminal heptad repeats, a short disulfide loop, and a tryptophan-rich domain (Fig. 1) (11). Sequential binding of gp120 to receptor (CD4) and coreceptor triggers conformational changes that promote insertion of the hydrophobic N terminus of gp41 into the target cell membrane. The conformational changes cause the gp41 oligomer to fold into a highly stable coiled-coil structure (4, 19, 35). Formation of the coiled-coil structure probably serves to bring the viral and cellular membranes into close proximity, allowing mixing of the lipid bilayers and release of the viral nucleoprotein complex into the target cell cytoplasm (5). gp41 is also required for oligomerization of the SU/TM complex and anchoring of the envelope complex in the viral membrane (11).

Several reports have described the effects of individual substitutions of the four conserved, N-linked glycosylation sites on the function of gp41. However, the results are difficult to compare because the studies differed in the choice of mutagenesis strategy, expression system, and cell line(s) used (7, 8, 10, 17, 26). While some reports claimed that specific attachment sites appear to be required for proper gp41 expression (7, 10), others reported that mutations at the same sites had only modest effects on protein function (8). Only two studies reported the effects of such mutations in the context of viral replication (8, 17), and to our knowledge, there are no reports on the replication of viruses lacking multiple N-linked glycans of gp41. In this study we have mutated each of the four sites singly and in all possible combinations and have tested the effects of the substitutions on viral replication in immortalized T-cell lines and activated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). The mutations were constructed and analyzed in the context of the chimeric virus SHIV-KB9, providing a useful tool for studying the impact of the HIV-1 gp41 N-glycan cluster on replication and pathogenesis in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Site-directed mutagenesis and subcloning.

Plasmids containing the 5′ and 3′ halves of the SHIV-89.6P molecular clone SHIV-KB9, and the SHIV-KB9 envelope expression vector, were kindly provided by B. Etemad-Moghadam and J. Sodroski (13). SHIV-KB9 proviral nucleotides are numbered as found in the GenBank database, accession no. U89134.

Individual N-linked glycosylation sites were mutagenized by the method of PCR followed by splicing by overlap extension (SOE) (34), using as a template a plasmid containing the 3′ half of the SHIV-KB9 provirus (from the SphI site at position 5929 through the 3′ long terminal repeat [LTR] and including all of env). For SOE, two overlapping PCR products are generated, with the desired substitution incorporated into the region of overlap. Then, in a second round of PCR, the two overlapping products are mixed together and fused by annealing and extension of the overlapping ends. Outside primers are included in the second round to amplify the fusion product. The result is a single PCR product containing the mutagenized site(s). Inclusion of relevant restriction sites in the outside primers facilitates subsequent cloning.

Overlapping first-round products, containing the four single-site mutations or the double substitution in sites 1 and 2, were generated by PCR. The overlapping fragments were then mixed and matched to construct full-length, SOE-fused fragments containing each of the single (g1, g2, g3, and g4) substitutions and one double (g12) substitution. DNA fragments generated by SOE were then digested with the restriction endonucleases KpnI and BamHI, and the resulting fragment was swapped into the SHIV-KB9 3′-half plasmid (13). The remaining double, triple, and quadruple mutants were also constructed by SOE, using the finished single and double mutant constructs as templates for the first-round PCR. For transient expression and fusion assays, KpnI-BamHI fragments corresponding to each mutant were also subcloned into a SHIV-KB9 envelope expression construct (9).

The outside primers used for amplification were WEJ-1 (positions 6457 to 6477; 5′ ATG GGG TAC CTG TGT GGA GAG 3′) and R13 (9092 to 9071; 5′ CCA AGG ATC CGT TCA CTG ATG G 3′). The following paired, overlapping primers were used for mutagenesis (the target site and position are indicated in parentheses, and lowercase letters specify the substituted nucleotides): WEJ-5 (g1, 8149 to 8201), 5′CTT CTG TGC CTT GGc AaG TTA GTT GGA GTA ATA AAT CTG TGG ATG ATA TTT GG3′; WEJ-6 (g1, 8185 to 8136), 5′ GAT TTA TTA CTC CAA CTA ACt TgC CAAGGC ACA GAA GTG GTG CAA ATG AG3′; WEJ-7 (g2, 8166 to 8201), 5′ GTT AGT TGG AGT cAa AAA TCT GTG GAT GAT ATT TGG3′; WEJ-8 (g2, 8201 to 8152), 5′ CCA AAT ATC ATC CAC AGA TTT tTg ACT CCA ACT AAC ATT CCA AGG CAC AG 3′; WEJ-9 (g3, 8187 to 8240), 5′ GTG GAT GAT ATT TGG AAT cAa ATG ACC TGG ATG GAG TGG GAA AGA GAA ATT GAC 3′; WEJ-10 (g3, 8222 to 8176), 5′ CTC CAT CCA GGT CAT tTg ATT CCA AAT ATC ATC CAC AGA TTT ATT AC 3′; WEJ-11 (g4, 8224 to 8271), 5′ GGG AAA GAG AAA TTG ACc AaT ACA CAG ACT ATA TAT ATG ACT TAC TTG 3′; WEJ-12 (g4, 8264 to 8210), 5′ GTC ATA TAT ATA GTC TGT GTA tTg GTC AAT TTC TCT TTC CCA CTC CAT CCA GGT C 3′; WEJ-13 (g12, 8149 to 8201), 5′ CTT CTG TGC CTT GGc AaG TTA GTT GGA GTc AaA AAT CTG TGG ATG ATA TTT GG 3′; and WEJ-14 (g12, 8200 to 8143), 5′ CAA ATA TCA TCC ACA GAT TTt TgA CTC CAA CTA ACt TgC CAA GGC ACA GAA GTG GTG C 3′.

Viral replication and cell culture.

221 cells (an immortalized rhesus monkey T-cell line), CEMx174 cells, and C8166-45 cells were maintained as described previously (21, 22). Rhesus monkey PBMC were purified by Ficoll separation of blood taken from specific-pathogen-free animals. Lymphocytes were activated by mixing PBMC from multiple animals in the same flask for 2 to 3 days; PBMC were then transferred to RPMI medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 10% interleukin-2.

To assay viral replication and to generate viral stocks, 5′ and 3′ viral clones (13) were digested with SphI and XhoI (5′ clone) or SphI and NotI (3′ clone), and the digested DNA was ligated overnight at 16°C with T4 DNA ligase to generate full-length proviral DNA. Five micrograms of ligated DNA was then used to transfect 221 cells, CEMx174 cells, or C8166-45 cells by the DEAE-dextran method (23). The medium was changed every 2 to 3 days, and viral replication was measured by monitoring the appearance of p27 in the supernatant. The p27 concentration was determined by antigen capture assay (Coulter Corporation, Hialeah, Fla.). For infections, medium was cleared of cells and debris by centrifugation, and aliquots containing 10 ng of p27 were used to inoculate 5 million pelleted cells. After 24 h, cells were pelleted, rinsed, and placed in fresh medium.

Env expression, immunoblots, and fusion assays.

Envelope expression constructs were constructed by replacing the KpnI-BamHI fragment of a SHIV-KB9 envelope expression construct (9) with the corresponding fragment from each of the mutant constructs. Expression was driven by the viral LTR and was dependent on coexpression of the tat and rev genes. For transient expression, 293T cells or COS-7 cells were transfected with 5 to 10 μg of calcium phosphate-precipitated DNA using the Profection Mammalian Transfection kit (Promega, Madison, Wis.).

For Western blotting, transfected 293T cells were rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline and lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer. Lysates were boiled in sample buffer, separated by electrophoresis, and transferred to membranes. The membranes were then treated sequentially with primary antibody (either anti-gp120 or anti-gp41) and secondary, horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibody and visualized using a chemiluminescent HRP detection system (Amersham). Primary antibodies were AD3 (anti-gp120) and 2F5 (anti-gp41) (National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program).

To assay levels of gp120 shedding by transfected cells, gp120 concentrations were determined using an HIV-1 gp120 antigen capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Advanced Biotechnologies, Inc., Columbia, Md.). gp120 levels in cell-free supernatants and in whole-cell lysates were determined; the level of gp120 in supernatants was calculated as a percentage of total gp120 (supernatant plus cell lysate) for each transfection. A construct expressing a secreted, soluble form of the HxBC2 gp120 protein was included as a positive control. The HxBC2 plasmid was a gift of S. Basmaciogullari and J. Sodroski.

The fusogenicity of various mutant envelopes was tested by cell-cell fusion assay. Briefly, target cells (293T cells) were seeded into 48-well plates, incubated overnight, and cotransfected with plasmids expressing Tat and either the parental or mutant Env proteins. At 18 to 24 h posttransfection the medium was removed, the cells were rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline, and fresh medium was added. At 48 h posttransfection the target cells were overlaid with effector cells. Effector cells expressed the CD4 receptor and an appropriate coreceptor and contained a Tat-inducible gene for secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP). In the event of Env-mediated fusion, the two cell types should fuse, allowing the Tat protein produced in the target cells to access and transactivate the SEAP reporter gene provided by the effector cells. Effector cells were either CEMx174 cells or C8166-45 cells engineered to contain the SEAP reporter (20). Fusogenicity was measured as the accumulation of SEAP activity in the supernatant over time. SEAP activity was assayed using the Phospha-Light Assay system (Tropix, Bedford, Mass.).

RESULTS

Conserved N-linked glycosylation sites of HIV-1 gp41.

Sequence alignments of the HIV-1 envelope protein revealed the presence of four well-conserved sites for the attachment of N-linked carbohydrates clustered within a 30-amino-acid stretch of the gp41 ectodomain (Fig. 1A). Related lentiviruses such as the SIVs typically have three or four sites for N-glycan attachment in this same region (16). Many of the nonprimate lentiviruses also have attachment sites in the analogous portions of their TM proteins. Using site-directed mutagenesis, we have replaced the asparagine residue of each of the conserved HIV-1 gp41 carbohydrate attachment sites with a glutamine (N-X-S/T → Q-X-S/T). There are four such sites in the gp41 ectodomain of SHIV-KB9; these sites were replaced singly and in combinations to generate all 15 possible variants. Substitutions were made by altering the first and third positions of each asparagine codon to create a codon for glutamine (AAT → CAA). Glutamine was chosen because it is structurally similar to asparagine, differing by only a single methylene group. Moreover, a minimum of two nucleotide changes are necessary for the altered sequence to revert to any codon specifying asparagine, thereby reducing the likelihood of direct reversion of the targeted codon during viral replication experiments. Mutants are indicated by a lowercase letter g followed by numerals designating which of the four attachment sites have been modified in that particular variant. For example, g123 refers to the triple mutant lacking the first, second, and third attachment sites of the gp41 protein (Fig. 1 and Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Replication of gp41 N-glycan attachment site mutants

| Virus | Replication ina:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEMx174 | 221 | C8166-45 | RhPBMC | |

| SHIV-KB9 | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| g1 | +++ | ++++ | ND | ++++ |

| g2 | +++ | ++++ | ND | +++ |

| g3 | +++ | ++++ | ND | +++ |

| g4 | +++ | ++++ | ND | +++ |

| g12 | + | ++ | ND | + |

| g13 | ++ | +++ | ND | +++ |

| g14 | ++ | +++ | ND | +++ |

| g23 | ++ | +++ | ND | +++ |

| g24 | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| g34 | ++ | +++ | ND | ++ |

| g123 | − | + | +++ | ND |

| g124 | − | ++ | +++ | ++ |

| g134 | + | +++ | +++ | + |

| g234 | + | +++ | +++ | ND |

| g1234 | − | − | − | ND |

+, replication was detectable by antigen capture assay; −, replication was below the limit of detection; ++++, peak replication similar to wild type; +++, slight delay (1 to 2 days) relative to wild type; ++, delayed (3 to 4 days) relative to wild type; ND, not done. The CEMx174, 221, and C8166-45 cell lines were tested by transfection; replication in rhesus monkey PBMC (RhPBMC) was tested by infection of 2 × 106 cells with viral supernatants normalized to contain 10 ng of p27 capsid antigen.

PCR fragments containing each mutation were generated using mutagenic primers and the method of SOE (see Materials and Methods for details); the template for PCR was a plasmid containing the 3′ half of the SHIV-KB9 genome (13). Once the single mutants were generated, each combination mutant was also generated by SOE, using the single mutant clones as templates for the first round of PCR. KpnI-BamHI fragments containing the substitutions were then used to replace the corresponding fragment in the parental plasmid. All mutant constructs were sequenced on both strands to confirm the absence of off-site mutations before being used for viral replication experiments.

Contribution of gp41 glycosylation to viral replication.

To assess the effects of the substitutions on viral replication, cloned viral DNAs containing each of the mutant envelope genes were transfected into CEMx174 cells, immortalized rhesus monkey T cells (221 cells), and, in some cases, the human T-cell line C8166-45. Transfection of 14 of the 15 mutants gave rise to replication-competent virus (Table 1), although the kinetics of replication varied considerably depending on the variant and the cell line. The replication-competent variants included all four of the single mutants (g1, g2, g3, and g4), the six double mutants (g12, g13, g14, g23, g24, and g34), and three of the four triple mutants (g123, g124, g134, and g234).

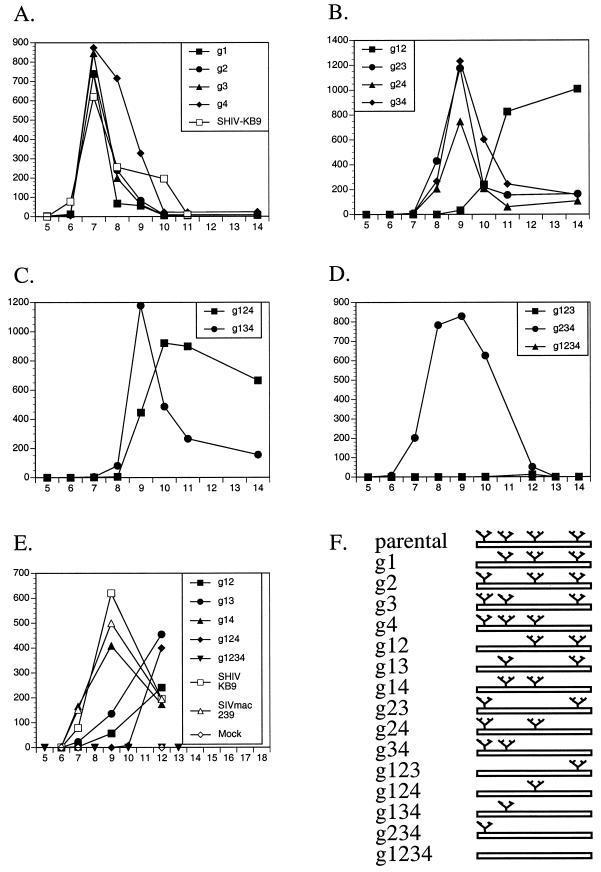

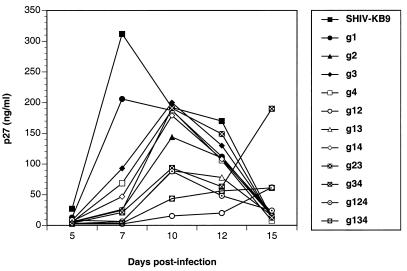

Results of representative transfection experiments are shown in Fig. 2. For these experiments, 221 cells (a rhesus monkey T-cell line) were transfected in parallel with each of the 15 mutants and the parental virus, SHIV-KB9. Replication of 13 of the 15 mutants produced peak yields within several days of the parental virus (as measured by p27 production in the supernatant) (Fig. 2), and a similar result was obtained with transfections of CEMx174 cells (data not shown). However, replication of the triple mutant g123 was severely reduced compared to that of the parental virus (Fig. 2D). The most severe defect in replication was exhibited by the g1234 mutant, which did not give rise to detectable virus production in repeated transfections (Fig. 2D and E). To rule out the possibility of unintended, inactivating, off-site mutations, the entire g1234 construct was regenerated twice, sequence confirmed, and retested by transfection. No replication was detected with either of the independent constructions upon multiple transfections with each (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Replication of glycosylation mutants in immortalized rhesus monkey T cells (221 cells) following transfection. Full-length viral DNAs containing the indicated substitutions were used to transfect 221 cells, and viral replication was monitored by the appearance of the p27 capsid antigen in the tissue culture supernatant. (A) Replication of SHIV-KB9 and the four single-site mutants. (B) Replication of four double mutants. (C) Replication of the g124 and g134 triple mutants. (D) Replication of g123, g234, and the quadruple mutant g1234. (E) Replication of various N-glycan attachment mutants, including g13 and g14. (F) Illustration depicting the glycosylation status of the four gp41 N-linked glycosylation sites in SHIV-KB9 and the 15 mutants used in this study.

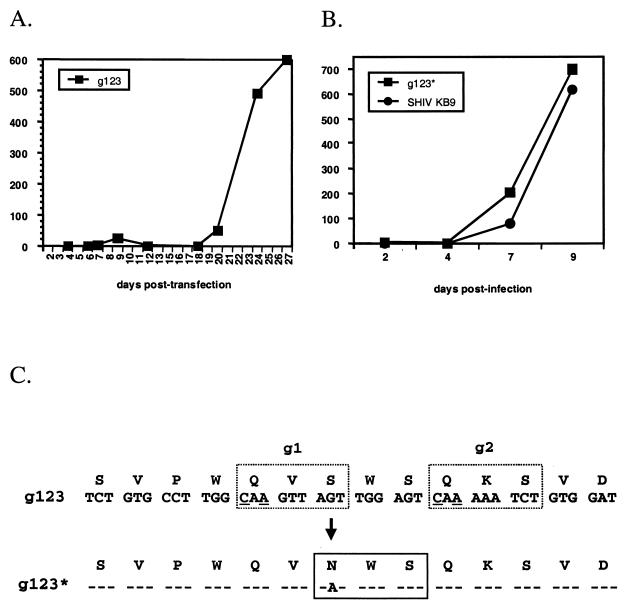

Viral p27 antigen was detected in the supernatant of the culture transfected with the g123 triple mutant DNA approximately 20 days after transfection of 221 cells (Fig. 3). This is in sharp contrast to the case for the other three triple mutants, which peaked at around day 9 posttransfection (Fig. 2). When virus-containing supernatant harvested on day 27 was used to infect fresh 221 cells, viral replication kinetics were similar to those of the parental virus (Fig. 3B). This result was consistent with reversion of one or more of the substituted N-X-S/T motifs in the g123 variant (designated g123*) or with the acquisition of compensatory changes. Sequencing of viral DNA amplified from infected 221 cells revealed a single G → A substitution in the gp41 ectodomain of g123, resulting in a serine-to-asparagine change at position 611 (Fig. 3C). The newly acquired asparagine replaced the serine residue of the first conserved attachment site and resulted in the creation of a new N-X-S/T glycosylation motif overlapping the first of the four conserved attachment sites. Since the appearance of compensatory changes is likely to be dependent upon errors made during viral replication, this result indicates that the original g123 mutant was replicating in the transfected 221 cells, albeit at or below the limit of detection of the p27 antigen capture assay. Transient expression and Western blotting confirm that the new N-X-S/T motif in the g123* protein is utilized for N-glycan attachment (see below). Sequence analysis was also performed on the g12 mutant, which showed a slight delay in peak replication. In the case of the g12 double mutant, the original substitutions were retained and there were no further coding changes in the gp41 ectodomain sequence.

FIG. 3.

Compensatory change in g123. (A) Replication of g123 after transfection of 221 cells. (B) 221 cells infected with supernatant harvested 24 days after transfection of mutant g123 (g123*) or with supernatant containing the parental virus (SHIV-KB9). (C) Top, sequence of the original g123 construct in the region of sites 1 and 2. Bottom, corresponding sequence of g123*, a variant of g123 which emerged at 24 days posttransfection. Dashed-line boxes indicate the substituted first and second sites in g123. The solid-line box indicates the new attachment site resulting from a single G → A nucleotide substitution.

Altogether, replication of each attachment site mutant was tested in a minimum of three independent transfections: two transfections of rhesus 221 cells and one transfection of CEMx174 cells. In addition, certain mutants were also tested for replication in C8166-45 cells (Table 1). Interestingly, the replication deficiency of mutant g123 was not apparent on C8166-45 cells (Table 1). Collectively, results from transfection experiments did not indicate that any individual attachment site(s) was absolutely required for viral replication, although mutants with substitutions in sites 1 and 2 were delayed (g12, g124, and g123) or defective (g1234) for replication in multiple experimental tests (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

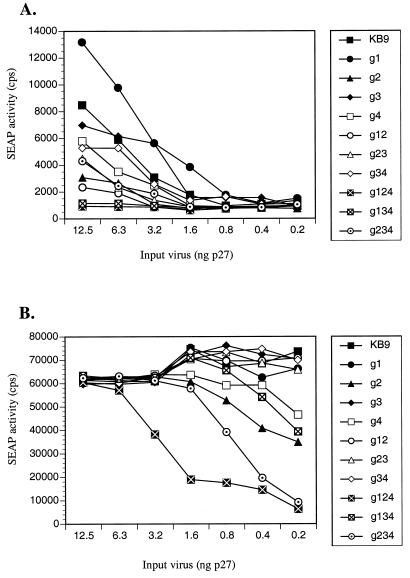

The infectious titer of viral stocks was measured on CEMx174SIV-SEAP and C8166-45SIV-SEAP indicator cells. These cell lines have been engineered to contain a gene for SEAP under the control of the SIV LTR promoter, which is activated by the SIV or HIV-1 Tat proteins (20). SEAP expression in the supernatant requires successful completion of the early stages of infection, including entry, reverse transcription, integration, and expression of the viral Tat protein. Viral stocks were normalized to contain the equivalent concentrations of p27 capsid antigen; stocks were then diluted and titers were determined on CEMx174SIV-SEAP and C8166-45SIV-SEAP cells (Fig. 4). SEAP activity was measured at 72 h postinfection to ensure that the results represented the initial infection events, prior to significant spread through the culture (20).

FIG. 4.

Infectious titers of attachment site mutants. Stocks of each virus were generated by transfection and normalized for p27 content. CEMx174SIV-SEAP (A) or C8166-45SIV-SEAP (B) indicator cells were infected with normalized amounts of each variant, and Tat-induced SEAP expression was measured on day 4 postinfection.

The C8166-45SIV-SEAP indicator cells were highly sensitive to infection by the parental virus as well as most of the mutant derivatives; the parental, g1, g12, g23, and g34 viruses showed little or no decrease in SEAP induction over the entire range of dilutions (12.5 to 0.2 ng of p27). The g2, g4, and g134 variants showed slight decreases at higher dilutions, and the only dramatic effect of the gp41 mutations on titer was evidenced by the g124 and g234 triple mutants (Fig. 4). When CEMx174SIV-SEAP indicator cells were used as target cells, differences in infectious titer were more apparent even at the lowest dilution (12.5 ng of p27). Although the two cell lines differed in overall sensitivity to infection, the rank orders of infectivities were similar. The parental virus and single-site mutants were among the most infectious, and the triple mutants were the least infectious. However, some variants, such as g12, did vary considerably in terms of relative infectivity (Fig. 4).

We also used normalized aliquots of each virus to infect pooled, activated rhesus monkey PBMC. Although none of the attachment site mutants replicated as well as the parental virus in PBMC, the single mutants and most of the double mutants replicated with only a slight delay (Fig. 5 and data not shown). g12, g34, g124, and g134 did not replicate as well as the other mutants on PBMC, with peak p27 levels of less than 100 ng/ml of supernatant. The results of both transfection and infection experiments indicate that no single attachment site is absolutely required for viral replication.

FIG. 5.

Replication of attachment site mutants in activated rhesus monkey PBMC. Approximately 5 million cells were infected with supernatant containing the indicated mutants after normalization for p27 content. Replication was monitored for 2 weeks by p27 antigen capture assay.

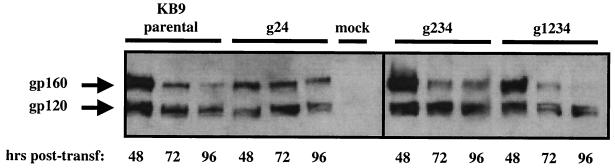

Expression and processing of glycosylation-deficient envelope proteins.

The effects of attachment site substitutions within the N-glycan cluster of gp41 on viral replication ranged from subtle (g1, g2, g3, and g4) to extreme (g123 and g1234). To analyze potential defects in expression or processing of the envelopes as possible causes for these differences, we cloned the mutant genes into an LTR-driven, tat- and rev-dependent expression vector. Expression constructs were then transfected into 293T cells, the cells were lysed at various time points, and the mutant proteins were visualized by Western blotting (Fig. 6). Expression and processing of the quadruple mutant protein (g1234), which is derived from a replication-defective variant, did not differ noticeably from expression and processing of the parental envelope protein or the g24 and g234 mutant proteins (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Expression and processing of attachment site mutants. 293T cells transfected with constructs expressing the parental (KB9) and g24, g234, and g1234 mutant proteins were lysed at 48, 72, and 96 h posttransfection, proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, and envelope proteins were visualized by Western blotting with an anti-gp120 antibody (AD3) and an appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibody.

To ascertain whether substitution of the N-glycan attachment sites affected the stability of the gp120-gp41 association, we investigated whether removal of the gp41 N-glycans led to an increase in shedding of gp120 from the surface of transfected cells. 293T cells and COS-7 cells were transfected with the constructs expressing the parental (SHIV-KB9) envelope, as well as the g134, g234, and g1234 combination mutant proteins. Antigen capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was used to quantitate the total gp120 protein in the transfected-cell supernatants and in whole-cell lysates at 48, 72, and 96 h posttransfection. As a positive control, cells were also transfected with a construct expressing a soluble, secreted form of HIV-1 gp120. gp120 in cell-free supernatant was then calculated as a percentage of the total (supernatant plus whole-cell lysate) gp120 production for each envelope variant (Table 2). The two triple mutants displayed a slight increase in gp120 shedding compared to the parental envelope protein (less than twofold), while the g1234 quadruple mutant exhibited significantly increased levels of shedding (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

gp120 shedding

| Cell type | Time (h) posttransfection | Envelope protein in supernatant (%)a

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental | g134 | g234 | g1234 | HxBC2 | ||

| COS-7 | 48 | 14.4 | 7.3 | 12.6 | 17.7 | 88.6 |

| 72 | 14.8 | 22.7 | 22.0 | 59.3 | 89.6 | |

| 96 | 16.4 | 26.8 | 23.5 | 60.7 | 91.6 | |

| 293T | 72 | 22.9 | 38.7 | 34.8 | 68.7 | 94.3 |

Values indicate gp120 present in cell-free supernatant as a percentage of total gp120 (supernatant plus whole-cell lysate). The HxBC2 construct used in this assay expressed a secreted form of gp120 protein.

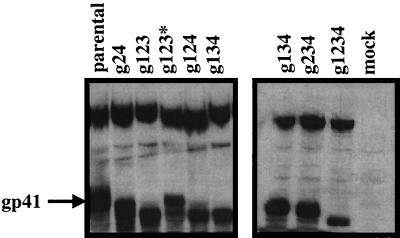

To confirm that each of the four predicted glycosylation sites of SHIV-KB9 is utilized for carbohydrate attachment, a subset of the mutant envelope genes was expressed by transient transfection of 293T cells. Proteins in transfected-cell lysates were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and analyzed by Western blotting. Migration of the altered gp41 proteins was visualized by reaction with a gp41-specific monoclonal antibody followed by incubation with an appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (see Materials and Methods).

On average, glycosylation of a single site is predicted to contribute approximately 2 to 3 kDa to the apparent molecular mass of a protein (15). Comparison of the migration patterns of several of the mutant proteins reveals that each of the four sites appears to be utilized for N-linked carbohydrate attachment (Fig. 7). For example, all four triple mutant proteins (g123, g124, g134, and g234) migrate at the same position, indicating that each of the four sites (4, 3, 2, and 1, respectively) can be utilized for N-linked glycosylation. The fastest-migrating species is the quadruple mutant g1234, at a position consistent with the loss of one additional site compared to any of the four triple mutant proteins. Moreover, the difference in migration between the g24 and g124 proteins is equivalent to the expected contribution of a single N-glycan.

FIG. 7.

Expression of gp41 attachment site mutants. Whole-cell lysates from 293T cells transfected with expression constructs were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by Western blotting. Proteins were visualized by probing with a monoclonal antibody to gp41 (2F5) followed with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. The mobility shifts of the double mutant (g24), each of the four triple mutants (g123, g124, g134, and g234), and the quadruple mutant (g1234) relative to the parental protein indicate that each of the canonical attachment sites is utilized for N-linked glycosylation. The slower migration of g123* is consistent with the acquisition of a new attachment site (compare lanes 3 and 4).

g123* (Fig. 7, lane 4) is the envelope protein of the variant that arose in cells originally transfected with the g123 viral clone (see above). The g123* gp41 sequence contains a new N-X-S/T glycosylation motif in addition to the unaltered fourth site and thus has the potential to be glycosylated at two positions (Fig. 3). The protein containing the new site migrates slower than the original g123 mutant protein but at the same position as the g24 double mutant (which contains two attachment sites), indicating that the newly acquired motif is in fact utilized for N-linked carbohydrate attachment (Fig. 7, lanes 2 and 4).

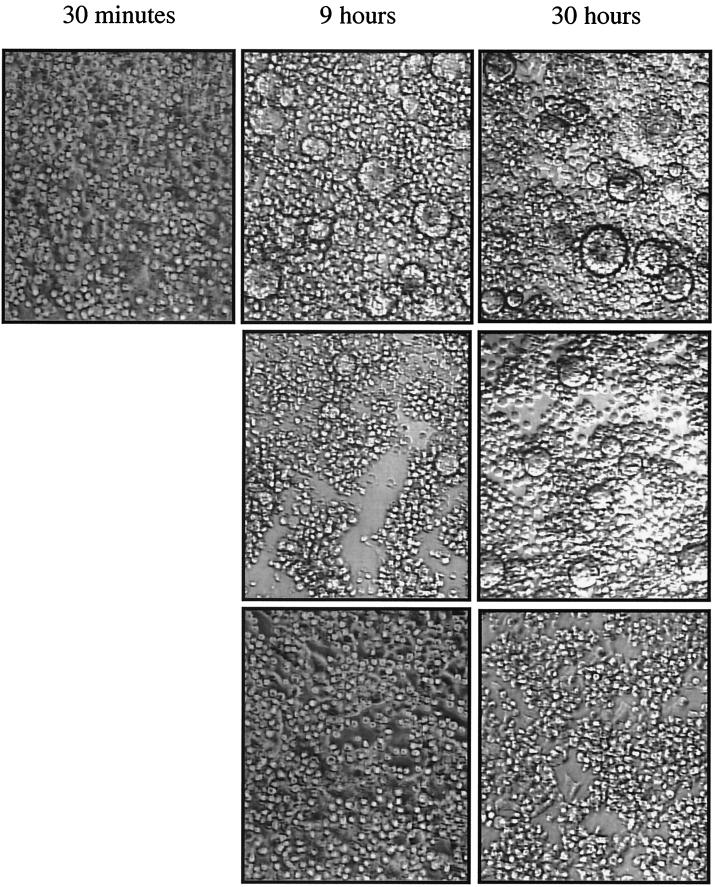

Fusogenicity of carbohydrate attachment site mutants.

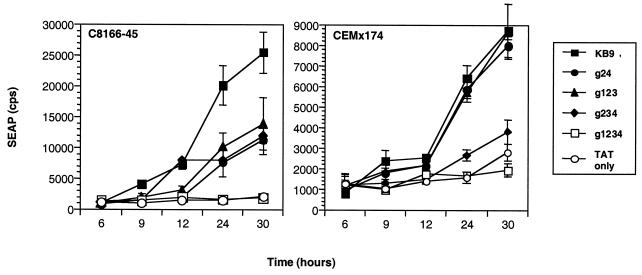

To assay fusogenicity, mutant envelope proteins and the HIV-1 Tat protein were coexpressed in target cells by transient transfection. At 48 h posttransfection, the target cells were mixed with effector cells. The effector cells express the viral receptor and coreceptor and contain an integrated, Tat-inducible SEAP reporter gene (20). In the event of Env-mediated fusion between target and effector cells, the contents of the two cell types mix and Tat protein produced by the target cells induces expression of the SEAP reporter gene. Fusion can then be visualized as the formation of syncytia and can also be measured as the accumulation of SEAP activity in the culture supernatant over time. Vectors expressing the parental, g24, g123, g124, g234, and g1234 envelope proteins were transfected into 293T target cells. CEMx174-SEAP and C8166-45SEAP cells, both of which support entry and replication of HIV-1 and SIV, were used as effector cells (20).

Formation of syncytia between the transfected target cells and CEMx174SEAP effector cells (Fig. 8) or C8166-45 cells (not shown) was observed using light microscopy. Expression of the parental envelope protein and the g24 protein gave rise to observable syncytium formation by 9 h after mixing of the two cell types, whereas there were no apparent syncytia in assays performed with the g1234 quadruple mutant, even at the 30-h time point (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Syncytium formation by SHIV-KB9 envelope and selected gp41 N-linked glycosylation mutants. The fusion assay was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 7. Representative fields were photographed at 30 min, 9 h, and 30 h after mixing of target and effector cells. Top row, SHIV-KB9 envelope. Middle row, g24 envelope. Bottom row, g1234 envelope.

Fusion-induced SEAP activity was also used to compare the activities of the parental and mutant envelope proteins. As can be seen in Fig. 9, the g123 envelope can mediate fusion with either effector cell type, despite being derived from a replication-deficient virus. Only the g1234 quadruple mutant exhibited no detectable fusogenic activity, even though the protein was expressed and processed to significant levels after transient transfection of 293T target cells (Fig. 6). Tat protein alone did not induce detectable SEAP expression, indicating that envelope expression is required for mixing of the contents of the two cell types (Fig. 8). The Tat-only control also rules out the possibility that soluble, secreted Tat interferes with the assay.

FIG. 9.

Fusogenicity of attachment site mutant envelopes. Effector cells were transfected with expression constructs and mixed with target cells at 48 h posttransfection. In the event of Env-mediated fusion, Tat protein from the effector cell induces SEAP expression from the target cell. Target cells are indicated in the upper left corner of each graph.

The envelope gene in SHIV-89.6, the progenitor of SHIV-KB9, was originally derived from a dual-tropic HIV-1 isolate (27). To test the receptor specificity of the envelope proteins, the fusion assay was repeated using GHOST cells as the effector cells. GHOST cells are a panel of cell lines expressing CD4 in the context of different coreceptors; additionally, each GHOST cell line contains an LTR-driven, Tat-inducible gene for green fluorescent protein (33). Successful fusion between an Env-expressing target cell and a GHOST effector cell is indicated by the formation of large, green syncytia. Using GHOST cells as effectors in the cell-cell fusion assay, we found that the parental SHIV-KB9 envelope, as well as the g24 double mutant and the g123 and g234 triple mutant envelopes, can mediate cell-cell fusion using either CCR5 or CXCR4 as a coreceptor (data not shown). As with the CEMx174SEAP and C8166-45SEAP effector cells, expression of the g1234 protein did not result in detectable fusion with GHOST cells bearing either coreceptor (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Studies utilizing SIV/HIV chimeric viruses (SHIV) combine the experimental advantages of a well-documented animal model for AIDS with access to a wealth of available HIV-1 reagents, including antibodies of defined specificity, banked sera, standardized assays, and established cell lines. Because one of the long-term aims of this work is to assess the potential effects of gp41 glycosylation on immunological control of the virus in vivo, the mutations described were engineered in the chimeric virus SHIV-KB9.

The ectodomain of the HIV-1 gp41 protein contains four canonical recognition sequences for the attachment of N-linked carbohydrates (16). The effects of single-site substitutions on protein expression and function have been reported (7, 8, 10, 17, 26), but only two of these studies looked at the role of individual N-glycans in viral replication (8, 17). In order to more thoroughly assess the role of the gp41 N-glycan cluster in viral replication, we constructed all possible multiply substituted variants and tested the effects of these substitutions on viral replication by transfection or infection of T-cell lines and primary rhesus monkey PBMC. Surprisingly, only 2 of the 15 possible attachment site mutants were severely deficient for viral replication (g123 and g1234). Each of the individual sites is dispensable for viral replication, although all sites appear to contribute to optimal replication efficiency. In general, the more completely glycosylated variants replicated better than those lacking multiple sites, with the triple mutants and the quadruple mutants displaying the greatest deficiency in viral replication. The same trend was seen when viral infectivity was measured on CEMx174SIV-SEAP indicator cells, suggesting that infectivity differences caused by combined substitution of multiple sites are a contributing factor to the differences in replication kinetics seen in viral replication assays.

The differences in replication, and the severe defects in replication displayed by some mutants, are not the result of gross defects in expression or processing of the envelope complex. Although cell surface expression was not addressed directly in this study, the positive results in fusion assays indicate that sufficient levels of the g123 envelope protein were expressed on the cell surface to promote cell-cell fusion. These experiments did not rule out subtle differences in the kinetics of expression and processing of the mutant proteins. However, such differences, if they exist, are not likely to explain the severity of the replication defect found in the g123- and g1234-containing viruses.

In addition to promoting membrane fusion, gp41 is also necessary for oligomerization of the envelope complex (11). It is possible that the various mutants tested here have less-than-optimal formation of functional envelope oligomers, with the most severe defect demonstrated by the g123 and g1234 mutants. A decrease in functional multimers could explain the general decrease in replication, if indeed glycosylation affects oligomerization. Once envelope complexes reach the cell surface, they also have to be incorporated into emerging virions. A defect in virion incorporation would not be detected in the cell-cell fusion assay. The experiments reported here do not address the possibilities that removal of N-linked attachment sites from gp41 can affect transport of envelope protein to the cell surface, incorporation of envelope complexes into virions, and/or gp41 oligomer stability. It remains possible that the g1234 mutant, which was not fusogenic in cell-cell fusion assays, may have a defect in the stability of the gp120-gp41 heterodimer (Table 2). Whether the degree of shedding seen with g1234 (three- to fourfold higher than that of the wild type) is sufficient to explain the defect in replication is not known.

Previous work in this laboratory has demonstrated that multiple N-linked carbohydrate attachment sites can be removed from the gp120 subunit of SIV, with little or no apparent effect on viral replication (28). Moreover, work done with SIV by our laboratory (29) and others (25), as well as with HIV-1 (1, 2, 31) and SHIV (6), has demonstrated a role for N-linked glycans in limiting recognition of gp120 protein sequences by antiviral antibodies. As far as we know, these types of observations have not been extended to include the N-glycan cluster of gp41. Interestingly, the regions of gp41 just N terminal and C terminal to the N-glycan cluster are highly antigenic, and numerous antibodies and polyclonal antisera directed to epitopes in these regions have been identified and characterized (14). In fact, the vast majority of antibodies against gp41 can be grouped into one of two clusters, depending on whether they recognize epitopes just N terminal to the N-glycans (cluster I) or just C terminal to the N-glycans (cluster II) (36). One possible explanation for the paucity of known antibodies to the region separating the two highly antigenic clusters is the presence of these four conserved N-glycans. The attachment site mutants of SHIV-KB9 described in this study will provide a useful framework for testing this possibility in vivo, using the well-characterized rhesus monkey model for AIDS pathogenesis (12).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

W.E.J. is supported by an Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation 2-Year Scholar Award, grant PF-77385. This work was also supported by Public Health Service grants AI25328, AI35365, and RR00168.

We thank B. Etemad-Moghadam, S. Basmaciogullari, and J. Sodroski for providing SHIV-KB9 constructs and the HxBC2 gp120 plasmid.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander S, Elder J H. Carbohydrate dramatically influences immune reactivity of antisera to viral glycoprotein antigens. Science. 1984;226:1328–1330. doi: 10.1126/science.6505693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Back N K, Smit L, De Jong J J, Keulen W, Schutten M, Goudsmit J, Tersmette M. An N-glycan within the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 V3 loop affects virus neutralization. Virology. 1994;199:431–438. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chackerian B, Rudensey L M, Overbaugh J. Specific N-linked and O-linked glycosylation modifications in the envelope V1 domain of simian immunodeficiency virus variants that evolve in the host alter recognition by neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 1997;71:7719–7727. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7719-7727.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan D C, Fass D, Berger J M, Kim P S. Core structure of gp41 from the HIV envelope glycoprotein. Cell. 1997;89:263–273. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan D C, Kim P S. HIV entry and its inhibition. Cell. 1998;93:681–684. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng-Mayer C, Brown A, Harouse J, Luciw P A, Mayer A J. Selection for neutralization resistance of the simian/human immunodeficiency virus SHIVSF33A variant in vivo by virtue of sequence changes in the extracellular envelope glycoprotein that modify N-linked glycosylation. J Virol. 1999;73:5294–5300. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5294-5300.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dash B, McIntosh A, Barrett W, Daniels R. Deletion of a single N-linked glycosylation site from the transmembrane envelope protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 stops cleavage and transport of gp160 preventing env-mediated fusion. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:1389–1397. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-6-1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dedera D A, Gu R L, Ratner L. Role of asparagine-linked glycosylation in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane envelope function. Virology. 1992;187:377–382. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90331-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Etemad-Moghadam B, Karlsson G B, Halloran M, Sun Y, Schenten D, Fernandes M, Letvin N L, Sodroski J. Characterization of simian-human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein epitopes recognized by neutralizing antibodies from infected monkeys. J Virol. 1998;72:8437–8445. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8437-8445.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fenouillet E, Jones I, Powell B, Schmitt D, Kieny M P, Gluckman J C. Functional role of the glycan cluster of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane glycoprotein (gp41) ectodomain. J Virol. 1993;67:150–160. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.1.150-160.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunter E. gp41., A multifunctional protein involved in HIV entry and pathogenesis, p. III-55–III-73. In: Korber B, Hahn B, Foley B, Mellors J W, Leitner T, Myers G, McCutchan F, Kuiken C L, editors. Human retroviruses and AIDS 1997: a compilation and analysis of nucleic acid and amino acid sequences. Los Alamos, N.Mex: Theoretical Biology and Biophysics Group, Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joag S V. Primate models of AIDS. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:223–229. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)00266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karlsson G B, Halloran M, Li J, Park I W, Gomila R, Reimann K A, Axthelm M K, Iliff S A, Letvin N L, Sodroski J. Characterization of molecularly cloned simian-human immunodeficiency viruses causing rapid CD4+ lymphocyte depletion in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1997;71:4218–4225. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4218-4225.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Korber B, Brander C, Haynes B F, Moore J P, Koup R, Walker B D, Watkins D I, editors. HIV molecular immunology database. Los Alamos, N.Mex: Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kornfeld R, Kornfeld S. Assembly of asparagine-linked oligosaccharides. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:631–664. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.003215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuiken C, Foley B, Hahn B, Korber B, McCutchan F, Marx P, Mellors J, Mullins J, Sodroski J, Wolinksy S, editors. Human retroviruses and AIDS 1999: a compilation and analysis of nucleic acid and amino acid sequences. Los Alamos, N.Mex: Theoretical Biology and Biophysics Group, Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee W R, Yu X F, Syu W J, Essex M, Lee T H. Mutational analysis of conserved N-linked glycosylation sites of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41. J Virol. 1992;66:1799–1803. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1799-1803.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leonard C K, Spellman M W, Riddle L, Harris R J, Thomas J N, Gregory T J. Assignment of intrachain disulfide bonds and characterization of potential glycosylation sites of the type 1 recombinant human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein (gp120) expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:10373–10382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malashkevich V N, Chan D C, Chutkowski C T, Kim P S. Crystal structure of the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) gp41 core: conserved helical interactions underlie the broad inhibitory activity of gp41 peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9134–9139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Means R E, Greenough T, Desrosiers R C. Neutralization sensitivity of cell culture-passaged simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1997;71:7895–7902. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7895-7902.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mori K, Ringler D J, Kodama T, Desrosiers R C. Complex determinants of macrophage tropism in env of simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1992;66:2067–2075. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2067-2075.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrison H G, Kirchhoff F, Desrosiers R C. Evidence for the cooperation of gp120 amino acids 322 and 448 in SIVmac entry. Virology. 1993;195:167–174. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naidu Y M, de Kestler H W, Li Y, Butler C V, Silva D P, Schmidt D K, Troup C D, Sehgal P K, Sonigo P, Daniel M D, et al. Characterization of infectious molecular clones of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIVmac) and human immunodeficiency virus type 2: persistent infection of rhesus monkeys with molecularly cloned SIVmac. J Virol. 1988;62:4691–4696. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.12.4691-4696.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Opdenakker G, Rudd P M, Ponting C P, Dwek R A. Concepts and principles of glycobiology. FASEB J. 1993;7:1330. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.14.8224606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Overbaugh J, Rudensey L M. Alterations in potential sites for glycosylation predominate during evolution of the simian immunodeficiency virus envelope gene in macaques. J Virol. 1992;66:5937–5948. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.10.5937-5948.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perrin C, Fenouillet E, Jones I M. Role of gp41 glycosylation sites in the biological activity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein. Virology. 1998;242:338–345. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.9016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reimann K A, Li J T, Voss G, Lekutis C, Tenner-Racz K, Racz P, Lin W, Montefiori D C, Lee-Parritz D E, Lu Y, Collman R G, Sodroski J, Letvin N L. An env gene derived from a primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate confers high in vivo replicative capacity to a chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1996;70:3198–3206. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.3198-3206.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reitter J N, Desrosiers R C. Identification of replication-competent strains of simian immunodeficiency virus lacking multiple attachment sites for N-linked carbohydrates in variable regions 1 and 2 of the surface envelope protein. J Virol. 1998;72:5399–5407. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5399-5407.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reitter J N, Means R E, Desrosiers R C. A role for carbohydrates in immune evasion in AIDS. Nat Med. 1998;4:679–684. doi: 10.1038/nm0698-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schonning K, Bolmstedt A, Novotny J, Lund O S, Olofsson S, Hansen J E. Induction of antibodies against epitopes inaccessible on the HIV type 1 envelope oligomer by immunization with recombinant monomeric glycoprotein 120. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1998;14:1451–1456. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schonning K, Jansson B, Olofsson S, Hansen J E. Rapid selection for an N-linked oligosaccharide by monoclonal antibodies directed against the V3 loop of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:753–758. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-4-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schonning K, Jansson B, Olofsson S, Nielsen J O, Hansen J S. Resistance to V3-directed neutralization caused by an N-linked oligosaccharide depends on the quaternary structure of the HIV-1 envelope oligomer. Virology. 1996;218:134–140. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trkola A, Ketas T, Kewalramani V N, Endorf F, Binley J M, Katinger H, Robinson J, Littman D R, Moore J P. Neutralization sensitivity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 primary isolates to antibodies and CD4-based reagents is independent of coreceptor usage. J Virol. 1998;72:1876–1885. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.1876-1885.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vallejo A N, Pogulis R J, Pease L R. Mutagenesis and synthesis of novel recombinant genes using PCR. In: Dieffenbach C W, Dveksler G S, editors. PCR primer: a laboratory manual. Plainview, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1995. pp. 603–612. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weissenhorn W, Dessen A, Harrison S C, Skehel J J, Wiley D C. Atomic structure of the ectodomain from HIV-1 gp41. Nature. 1997;387:426–430. doi: 10.1038/387426a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu J Y, Gorny M K, Palker T, Karwowska S, Zolla-Pazner S. Epitope mapping of two immunodominant domains of gp41, the transmembrane protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1, using 10 human monoclonal antibodies. J Virol. 1991;65:4832–4838. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.9.4832-4838.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]