Abstract

Penile squamous cell carcinoma (PSCC) is classified into 2 prognostically distinct types: human papillomavirus (HPV)–associated and HPV-independent. However, the impact of p53 status on prognosis remains controversial. We correlated HPV and p53 status with the prognosis of a large series of patients with PSCC. p53 was analyzed according to a recently described immunohistochemical (IHC) pattern-based framework that includes 2 normal and 4 abnormal patterns and closely correlates with TP53 mutational status. A total of 122 patients with surgically treated PSCC in 3 hospitals were included. Based on HPV in situ hybridization and p16 and p53 IHC, the tumors were classified into 3 subtypes: HPV-associated, HPV-independent/p53 normal, and HPV-independent/p53 abnormal. All patients were followed up for at least 22 months (median: 56.9 months). Thirty-six tumors (29%) were HPV-associated, 35 (29%) were HPV-independent/p53 normal, and 51 (42%) were HPV-independent/p53 abnormal. Disease-related deaths were observed in 3/36 (8%), 0/35 (0%) and 14/51 (27%) of the patients, respectively (P < 0.001). A total of 7/14 deaths in the latter group were patients with tumors showing p53 abnormal patterns not recognized in the classic p53 IHC interpretation (basal, null, and cytoplasmic). According to our multivariate analysis, HPV-independent/p53 abnormal tumors and advanced stage were associated with impaired disease-specific survival (hazard ratio = 23.4, 95% CI = 2.7-3095.3; P = 0.001 and 16.3, 95% CI = 1.8-2151.5; P = 0.008, respectively). In conclusion, compared with patients with HPV-associated and HPV-independent/p53-normal PSCC, patients with HPV-independent/p53 abnormal PSCC have worse clinical outcomes. p53 IHC results define 2 prognostic categories in HPV-independent PSCC: HPV-independent/p53-normal tumors as low-risk tumors, whereas HPV-independent/p53-abnormal tumors as aggressive neoplasms.

Key Words: penile cancer, penile squamous cell carcinoma, HPV, p53, prognosis

Penile squamous cell carcinoma (PSCC) is an uncommon and aggressive neoplasm. Its incidence has marked geographic variability,1,2 and it is particularly high (2.5/100,000 inhabitants) in Spain.3 Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, phimosis, absence of circumcision, chronic inflammation, lichen sclerosus, and smoking have been described as risk factors for the development of the disease.4 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), PSCCs should be classified based on their association with HPV. For this reason, immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for p16, a surrogate of transforming HPV infection, is strongly recommended by the WHO in its last classification of urological tumors.5

Genomic instability secondary to the overexpression of the oncoproteins E6 and E7, leading to an uncontrolled progression of the cell cycle is considered a key molecular mechanism involved in HPV-associated PSCC.6,7 Conversely, the molecular background of HPV-independent PSCC is less well understood, with several recent series reporting that TP53 mutations are highly recurrent in this subset of tumors.6,8–12 Growing evidence suggests that the TP53 (p53 IHC) status is associated with nodal metastases and thus with a worse prognosis in patients with PSCC,8,9,13,14 in accordance with its adverse survival impact in other types of cancers.15 However, the prognostic impact of TP53 (p53 IHC) status has not been explored within the group of HPV-independent PSCC.

There are a few barriers to the successful implementation of p53 as a prognostic biomarker.15 One of these barriers includes the assessment of p53 IHC as merely “positive” or “negative.” In this regard, a pattern-based p53 IHC interpretation is being progressively recognized and implemented across several pathology subspecialties, particularly in gynecologic pathology.15 In a recent study,16 we applied a p53 IHC pattern-based framework described initially for vulvar tumors17 to a series of PSCC and demonstrated a strong correlation with TP53 mutational status. In this scheme, two p53 IHC patterns (scattered and mid-epithelial), defined as “normal,” indicate a wild-type TP53, whereas 4 patterns (diffuse overexpression, basal overexpression, cytoplasmic, and null), defined as “abnormal,” strongly correlate with a mutated TP53. Notably, 3 of the mutant patterns, namely, basal overexpression, cytoplasmic, and null, have been consistently classified as “normal” in previous studies on PSCC.18,19

We aimed to evaluate the HPV and TP53 statuses in a large series of PSCC from 3 public institutions in Spain by classifying the tumors based on HPV in situ hybridization (ISH) and p16 and p53 IHC analysis into 3 molecular categories: HPV-associated, HPV-independent/p53 normal, and HPV-independent/p53 abnormal. We analyzed the prognostic implications of this molecular classification system.

METHODS

Patients

We retrospectively identified all patients surgically treated for PSCC in 2 tertiary general hospitals (Hospital Clinic de Barcelona, Vall d’Hebron Barcelona Hospital) and a monographic urological center (Fundació Puigvert) in Barcelona, Spain, from January 2000 to December 2020. All patients fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: (1) had a primary diagnosis of PSCC, (2) had a follow-up of at least 22 months or until death, and (3) had sufficient available tumor tissue for ancillary IHC studies.

All patients were treated following the guidelines of the European Association of Urology18 depending on the clinical staging, which was determined on the basis of physical examination plus imaging techniques (ultrasound scan, computed tomography scan, and/or positron emission tomography, etc) when required. All local excisions aimed at organ sparing and reconstructive techniques were used when necessary to minimize the functional impact. Inguinal lymph node evaluation was performed if required. Guided sentinel node biopsy was the first option. Endoscopic inguinal modified lymphadenectomy was performed when sentinel node biopsy was not available. In all patients with positive sentinel node, a radical inguinal lymphadenectomy was performed.

The following clinical and pathologic variables were retrieved from the electronic files: age at diagnosis, tumor location, type and date/s of treatment/s, margin status, vascular invasion, perineural invasion, stage at diagnosis, date of first cancer recurrence, and patient status at follow-up.

The study was approved by the Healthcare Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona, Hospital Vall d’Hebron, and Fundació Puigvert (HCB/2020/1207, PR(AG)578/2021, FP2021/05c, respectively). Informed written consent was obtained from all the patients included in the study.

p16 IHC

IHC for p16 was performed for all samples using the CINtec Histology Kit (clone E6H4; Roche). Tumors with strong and diffuse block-type staining were considered positive, whereas patchy or completely negative p16 staining was considered p16 negative.20 In each run a p16-positive squamous carcinoma of the vulva was used as positive control. All patients were independently evaluated by 2 pathologists with expertise in the interpretation of p16 staining (I.T. and N.R.).

In Situ Hybridization

RNA ISH was performed for all samples using the automated Leica Biosystems BOND-III and RNAscope ISH probe high-risk HPV. The assay qualitatively detects E6 mRNA in 16, 18, 26, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68, 73, and 82 high-risk HPV types. In each run, carcinoma of the uterine cervix with known HPV16 positivity was used as a control.

p53 IHC

p53 IHC was performed in all patients with a monoclonal antibody (clone DO-7; Roche) on an automated staining system (Ventana Benchmark ULTRA, Ventana Medical Systems). IHC staining was evaluated following the recently described p53 pattern-based interpretation framework described for squamous cell carcinomas of the vulva17 and recently confirmed in PSCC;16 this method includes 2 major categories: “normal,” which correlates with wild-type TP53, and “abnormal staining,” which correlates with mutated TP53. The “normal” category included 2 patterns: (1) occasional positive nuclei in the basal and/or parabasal layer (scattered pattern) and (2) moderate to strong nuclear p53 IHC staining in the parabasal layers with absence of expression in the basal cells (mid-epithelial pattern). The “abnormal” category included four p53 IHC patterns: (1) continuous, strong nuclear staining of the basal layer (basal overexpression pattern), (2) continuous and strong nuclear basal staining with suprabasal extension (diffuse overexpression pattern), (3) cytoplasmic staining with or without nuclear positivity (cytoplasmic pattern), and (4) complete absence of staining in the tumor (null pattern), with evidence of intrinsic positive control (positive staining in adjacent inflammatory and stromal cells). All patients were independently evaluated by 2 pathologists with expertise in the interpretation of p53 staining (I.T. and N.R.). All discrepancies were discussed in a consensus meeting, and a final evaluation was achieved. In each run a normal tonsil showing scattered positive staining and a serous carcinoma of the ovary with diffuse p53 IHC overexpression were used as controls. Thirty-three patients were previously included in a recent study focused on the validation of this pattern-based p53 interpretation framework against TP53 mutational analysis, in which 95% concordance was observed.16

The Criteria for PSCC Classification Into Three Groups

All the study cases were classified into 3 main categories based on HPV ISH and p16 IHC results and the pattern of p53 IHC. The categories included the following: (1) HPV-associated PSCC (positive for HPV ISH and p16 IHC, independent of the p53 IHC pattern), (2) HPV-independent/p53 normal PSCC (negative for HPV ISH and p16 IHC and a scattered or mid-epithelial p53 IHC pattern), and (3) HPV-independent/p53 abnormal PSCC (negative for HPV ISH and p16 IHC and diffuse, basal overexpression, cytoplasmic or null patterns of p53 IHC).

Statistical Analyses

The statistical analyses were conducted using R Statistical Software (v4.3.2; R Core Team 2021). The χ2 test and Fisher exact test were employed for categorical data, whereas the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was utilized for numerical data, enabling the comparison of clinical and histopathological data.

The endpoints for prognosis were recurrence-free survival (RFS) and disease-specific survival (DSS), which were calculated from the date of treatment (primary surgery) to the date of first recurrence or progression or to death due to the disease, respectively. Cumulative incidences were depicted through plotted curves, and differences between the curves were assessed using a Gray test. Univariate and adjusted (multivariate) models were obtained using the Cox proportional hazards model. For the multivariate analysis, 2 models were built, one including the molecular type and the second including the p53 IHC status, due to the collinearity of these 2 variables. Two-sided tests were used, and a P value <0.05 indicated statistical significance.

RESULTS

Clinical Pathologic Features of the Overall Series

One hundred twenty-two patients were included in the study. Of these, 43 were from the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, 35 were from the Hospital Vall d’Hebron, and 44 were from the Fundació Puigvert. The mean age at diagnosis was 68.6 years (range: 40 to 96). Fifty-eight patients (47.5%) were stage I at diagnosis, 40 (32.8%) were stage II, 16 (13.1%) were stage III, and 8 (6.6%) were stage IV tumors. The median follow-up period was 56.9 months (range: 22 to 60 months). Sixty-five patients (53.3%) underwent penectomy (partial or radical), 48 (39.3%) glansectomy, and in 9 patients (7.4%) circumcision was performed. Metastatic involvement of the lymph nodes was identified in 24 patients (19.7%).

HPV ISH and p16 and p53 IHC Results and Tumor Classification

HPV ISH was positive in 36/122 tumors (29.5%), and in all of them, p16 IHC was positive. These tumors were classified accordingly as HPV-associated tumors. Thirty-two of the 36 HPV-associated tumors had a normal pattern of p53 IHC expression (88.9%), 31 had a scattered pattern, and 1 had a mid-epithelial pattern of p53 IHC. Only 4 (11.1%) HPV-associated tumors presented an abnormal p53: 2 had diffuse overexpression, 1 had basal overexpression, and 1 had a null pattern.

Eighty-six out of the 122 tumors (70.5%) were negative for HPV ISH and p16 IHC and were classified as HPV-independent. Among the 86 tumors, 35 (28.7% of the overall series) showed a normal p53 IHC and were classified as HPV-independent/p53 normal, all of which exhibited a scattered pattern. Fifty-one tumors in this HPV-independent category (41.8% of the overall series) had an abnormal p53 IHC and were classified as HPV-independent/p53 abnormal. The most common abnormal p53 IHC pattern in this cohort was diffuse overexpression (27/51, 53.0%), followed by a null pattern (14 patients, 27.4%), basal overexpression (8 patients, 15.7%), and cytoplasmic expression (2/51, 3.9%).

Characteristics of the Three Molecular Types of PSCC

Table 1 summarizes the clinical and pathologic features of the patients classified into the 3 molecular categories defined in this study. Patients with HPV-independent/p53 normal tumors were older (mean age of 72 years) than those with the other 2 categories (67 years for both HPV-associated and HPV-independent/p53 abnormal tumors [P = 0.040]). Patients with HPV-independent/p53 abnormal tumors had a greater risk of lymph node metastases than patients with HPV-independent/p53 normal tumors (P = 0.012).

TABLE 1.

Pathologic Features, Staging, and Follow-up Results in the 3 Types of PSCC: HPV-associated, HPV-independent With Normal p53 Expression, and HPV-independent With Abnormal p53 Expression

| HPV-associated | HPV-independent | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 36) | p53 normal (n = 35) | p53 abnormal (n = 51) | P | |

| Age | 67.1 (45.0, 94.0) | 72.5 (46.0, 96.0) | 67.1 (40.0, 87.0) | 0.223 |

| Anatomic location; n (%) | 0.195 | |||

| Glans | 21 (58.3) | 25 (71.4) | 41 (80.4) | — |

| Foreskin, coronal sulcus, body | 11 (30.6) | 8 (22.9) | 9 (17.6) | — |

| Not recorded | 4 (11.1) | 2 (5.7) | 1 (2.0) | — |

| Histologic type; n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Usual | 7 (19.4) | 27 (77.1) | 39 (76.5) | — |

| Verrucous | 0 | 5 (14.3) | 3 (5.9) | — |

| Basaloid | 16 (44.4) | 0 | 4 (7.8) | — |

| Warty | 4 (11.1) | 1 (2.9) | 0 | — |

| Mixed | 7 (19.4) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.0) | — |

| Sarcomatoid | 1 (2.8) | 0 | 4 (7.8) | — |

| Lymphoepitelioma-like | 1 (2.8) | 0 | 0 | — |

| Cuniculatum | 0 | 1 (2.9) | 0 | — |

| Vascular invasion; n (%) | 0.992 | |||

| No | 33 (91.7) | 32 (91.4) | 47 (92.2) | — |

| Yes | 3 (8.3) | 3 (8.6) | 4 (7.8) | — |

| Perineural invasion; n (%) | 0.340 | |||

| No | 33 (91.7) | 34 (97.1) | 47 (92.2) | — |

| Yes | 3 (8.3) | 1 (2.9) | 7 (13.7) | — |

| Lymph node metastases; n (%) | 0.040 | |||

| No | 28 (77.8) | 33 (94.3) | 37 (72.5) | — |

| Yes | 8 (22.2) | 2 (5.7) | 14 (27.5) | — |

| Stage; n (%) | 0.124 | |||

| I | 13 (36.1) | 22 (62.9) | 23 (45.0) | — |

| II | 15 (41.7) | 11 (31.4) | 14 (27.5) | — |

| III | 6 (16.7) | 1 (2.9) | 9 (17.6) | — |

| IV | 2 (5.6) | 1 (2.9) | 5 (9.8) | — |

| Surgical margins (invasive tumor); n (%) | 1.000 | |||

| Free | 31 (86.1) | 31 (88.6) | 44 (86.3) | — |

| Affected | 5 (13.9) | 4 (11.4) | 7 (13.7) | — |

| Chemotherapy; n (%) | 0.219 | |||

| No | 31 (86.1) | 34 (97.1) | 45 (88.2) | — |

| Yes | 5 (13.9) | 1 (2.9) | 6 (11.8) | — |

| Radiotherapy; n (%) | 0.118 | |||

| No | 31 (86.1) | 33 (94.3) | 40 (78.4) | — |

| Yes | 5 (13.9) | 2 (5.7) | 11 (21.6) | — |

| Recurrence; n (%) | 0.067 | |||

| No | 30 (83.3) | 29 (82.9) | 33 (64.7) | — |

| Yes | 6 (16.7) | 6 (17.1) | 18 (35.3) | — |

| Death of disease; n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| No | 33 (91.7) | 35 (100) | 37 (72.5) | — |

| Yes | 3 (8.3) | 0 | 14 (27.5) | — |

Significant values (p<0.05) are highlighted in bold.

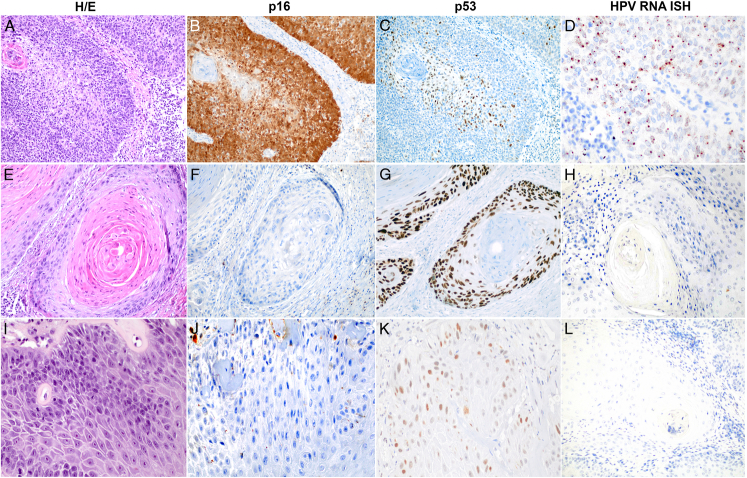

The histologic variants of the HPV-associated tumors significantly differed from the variants identified in the HPV-independent molecular types. Moreover, there were no differences in terms of histologic variants between HPV-independent/p53 normal and HPV-independent/p53 abnormal tumors. No differences were observed in terms of anatomic location, vascular or perineural invasion, margin status, or stage at diagnosis. Figure 1 shows a representative example of each of the 3 tumor categories, including hematoxylin and eosin staining features, as well as HPV ISH and p16 and p53 IHC staining.

FIGURE 1.

Histologic (hematoxylin and eosin), p16 and p53 IHC expression and HPV ISH of a typical example of HPV-associated PSCC (A–D), HPV-independent PSCC with abnormal p53 (E–H) and HPV-independent PSCC with normal p53 (I–L). A, E, and I, hematoxylin and eosin. B, F, and J, p16 IHC. C, G, and J, p53 IHC. D, H, and L, HPV RNA ISH.

Survival Analysis

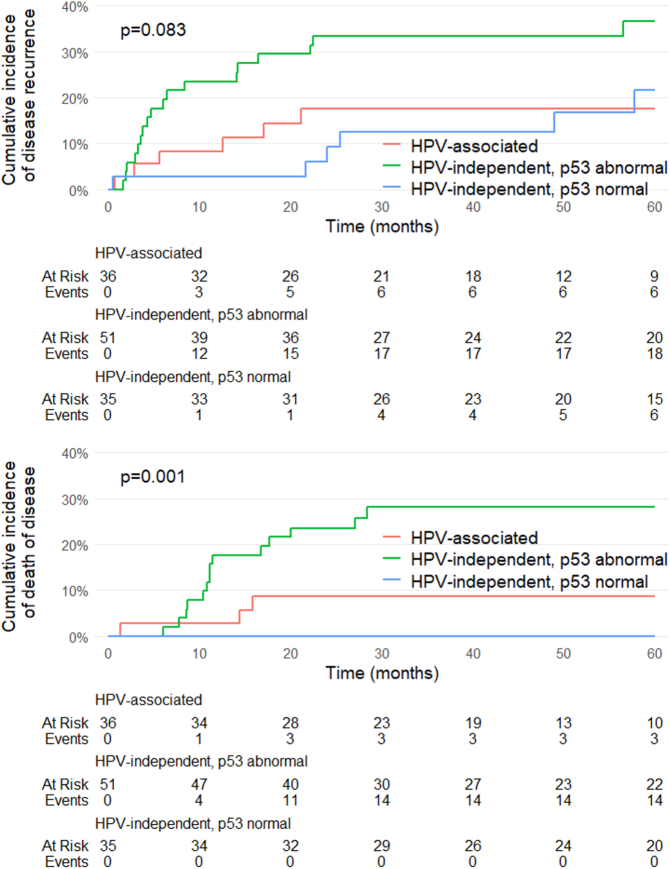

Thirty patients (24.6%) experienced disease recurrence during follow-up, but no differences were observed among the 3 molecular types in terms of recurrence rate (P = 0.067). Seventeen patients (13.9%) died due to PSCC, and 13 (10.6%) died due to other causes. Disease-related death was observed in 3/36 (8.3%) patients with HPV-associated PSCC and 0/35 (0.0%) patients with HPV-independent/p53 normal PSCC, with the highest number of events occurring in patients with HPV-independent/p53 abnormal PSCC (14/51 [27.5%]; P < 0.001). The patterns of p53 IHC in the HPV-independent tumors of the patients who died due to the tumor were diffuse overexpression (7/27; 25.9%), null pattern (5/14; 35.7%), basal overexpression (1/8; 12.5%), and cytoplasmic expression (1/2; 50%).

Figure 2 shows the cumulative incidence curves for RFS and DSS for the 3 molecular categories. No differences in RFS were observed among the 3 molecular types (P = 0.083); however, significant differences in DSS were detected (P = 0.001), with patients with HPV-independent/p53 abnormal PSCC having the worst survival outcomes. In terms of tumor staging, no differences in RFS were observed between patients with early-stage tumors and patients with advanced-stage tumors (P = 0.073); however, significant differences in DSS were identified (P < 0.001). Remarkably, 10/14 (71.4%) patients with HPV-independent/p53 abnormal PSCC diagnosed with stage III or IV died from the disease compared with only 2/8 (25.0%) of the patients with HPV-associated tumors in stages III or IV and 0/2 (0.0%) of the HPV-independent/p53 normal patients in stages III or IV (P = 0.048). Table 2 shows the Cox regression analysis for RFS. Vascular invasion, perineural invasion, lymph node metastasis, and advanced disease stage were associated with impaired RFS in the univariate analysis. According to the multivariate analysis, only vascular invasion reached statistical significance.

FIGURE 2.

Cumulative incidence graphs for disease recurrence and death due to the disease of the 3 types of PSCC: HPV-associated, HPV-independent with normal p53 expression, and HPV-independent with abnormal p53 expression.

TABLE 2.

Univariate and Multivariate Cox Model for RFS.

| Univariate model | Multivariate model with molecular type | Multivariate model with p53 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P |

| Age | 1 (0.9-1) | 0.415 | — | — | — | — |

| Molecular type | ||||||

| HPV-independent/p53 normal | 1 | — | 1 | — | — | — |

| HPV-associated | 1.1 (0.4-3.3) | 0.865 | 1.3 (0.4-4.2) | 0.672 | — | — |

| HPV-independent/p53 abnormal | 2.2 (0.9-5.9) | 0.062 | 2.3 (0.9-6.5) | 0.065 | — | — |

| p53 immunohistochemistry | ||||||

| Normal | 1 | — | — | — | 1 | — |

| Abnormal | 1.9 (0.9-4.1) | 0.062 | — | — | 1.2 (0.9-4.2) | 0.070 |

| Vascular invasion | ||||||

| No | 1 | — | 1 | — | 1 | — |

| Yes | 8.0 (3.2-18.0) | <0.001 | 3.9 (1.1-12.7) | 0.031 | 3.6 (1.1-11.7) | 0.037 |

| Perineural invasion | ||||||

| No | 1 | — | 1 | — | 1 | — |

| Yes | 6.8 (2.9-14.6) | <0.001 | 2.3 (0.7-6.4) | 0.150 | 2.3 (0.7-6.5) | 0.148 |

| Lymph node metastases | ||||||

| No | 1 | — | 1 | — | 1 | — |

| Yes | 4.4 (2.1-9.1) | <0.001 | 2.3 (0.9-5.9) | 0.079 | 2.4 (0.9-6.4) | 0.063 |

| Staging | ||||||

| Early (I) | 1 | — | 1 | — | 1 | — |

| Advanced (II-IV) | 2.2 (1.1-4.8) | 0.033 | 1.2 (0.5-3.1) | 0.712 | 1.2 (0.4-2.9) | 0.737 |

Significant values (p<0.05) are highlighted in bold.

HPV indicates human papillomavirus; HR, hazard ratio; RFS, recurrence-free survival.

The results of the Cox regression analysis for DSS are shown in Table 3. The molecular type (HPV-independent/p53 abnormal), p53 IHC abnormal pattern, vascular invasion, perineural invasion, lymph node metastases, and advanced stages were associated with impaired DSS in the univariate analysis. The 2 multivariate models showed that HPV-independent/p53 abnormal molecular type (P = 0.001) or p53 IHC expression (P = 0.001), in addition to vascular and perineural invasion, lymph node metastases, and advanced-stage, were significantly associated with impaired DSS.

TABLE 3.

Univariate and Multivariate Cox Model for Disease-specific Mortality.

| Univariate model | Multivariate model with molecular type | Multivariate model with p53 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI | P | HR (95% CI | P | HR (95% CI | P | |

| Age | 1 (0.9-1) | 0.808 | — | — | — | — |

| Molecular type | ||||||

| HPV-independent/p53 normal | 1 | — | 1 | — | — | — |

| HPV-associated | 7.3 (0.7-986.3) | 0.102 | 6.7 (0.6-929.2) | 0.138 | — | — |

| HPV-independent/p53 abnormal | 21.9 (2.9-2804.6) | <0.001 | 23.4 (2.7-3095.3) | 0.001 | — | — |

| p53 immunohistochemistry | ||||||

| Normal | 1 | — | — | — | 1 | — |

| Abnormal | 5.42 (1.9-20.9) | 0.001 | — | — | 5.9 (1.9-23.7) | 0.001 |

| Vascular invasion | ||||||

| No | 1 | — | 1 | — | 1 | — |

| Yes | 10.3 (3.7-26.7) | <0.001 | 3.5 (1.1-10.9) | 0.035 | 2.9 (0.9-9.2) | 0.071 |

| Perineural invasion | ||||||

| No | 1 | — | 1 | — | 1 | — |

| Yes | 9.7 (3.6-24.8) | <0.001 | 3.0 (1.0-8.7) | 0.049 | 2.8 (0.9-8.2) | 0.065 |

| Lymph node metastases | ||||||

| No | 1 | — | 1 | — | 1 | — |

| Yes | 13.5 (5.1-40.5) | <0.001 | 2.8 (1.0-8.8) | 0.045 | 3.2 (1.1-9.9) | 0.028 |

| Staging | ||||||

| Early (I) | 1 | — | 1 | — | 1 | — |

| Advanced (II-IV) | 36.9 (5.0-4706.3) | <0.001 | 16.3 (1.8-2151.5) | 0.008 | 16.0 (1.8-2103.0) | 0.008 |

Significant values (p<0.05) are highlighted in bold.

HPV indicates human papillomavirus; HR, hazard ratio.

DISCUSSION

The most remarkable finding of our study, which included a large series of patients with PSCC treated at 3 different institutions in Barcelona, Spain, was the difference in prognosis observed among the 3 molecular types of PSCC defined according to their association with HPV and p53 IHC: HPV-associated, HPV-independent with normal p53, and HPV-independent with abnormal p53 PSCC. Remarkably, the classification of the tumors based on HPV status and p53 IHC patterns had a stronger impact on DSS in the multivariate analysis than did the staging system, suggesting that not only HPV status but also p53 IHC should be routinely evaluated in all patients with PSCC.

The good prognosis of patients with HPV-associated tumors (over 90% DSS at 5 years) strongly supports the current 2022 WHO classification of PSCC, which separates tumors based on HPV status.5 Studies on the prognostic impact of HPV status in patients with PSCC have shown controversial results, with some reporting no differences in DSS,21 and others showing longer DSS in HPV-associated PSCC,22,23 in similarity to what occurs in HPV-associated carcinomas in other anatomic sites, such as the head and neck.24 The good DSS of patients with HPV-associated tumors in our study is remarkable, considering that these patients were frequently diagnosed in advanced stages and 25% of them had metastatic involvement of the lymph nodes. These results suggest that, as shown in HPV-associated tumors from other anatomic areas, HPV-associated PSCC is highly sensitive to radiation and chemotherapy.25 In accordance with the findings of other European series,26 HPV-associated tumors represented a small percentage (29.5%) of all PSCC. As previously reported,27 p16 IHC results have shown excellent correlation with HPV ISH, reinforcing the validity of the recent WHO 2022 recommendation of using p16 IHC as a surrogate for the presence of high-risk HPV.5 Our study revealed that the second type of PSCC defined by the WHO, HPV-independent tumors, includes at least 2 categories with different clinical and pathologic features and, most importantly, a different prognosis. In the first category, HPV-independent PSCC with normal p53 expression is associated with several specific clinical pathologic features. These tumors arise in older men, have a very low rate of lymph node metastases, and are rarely diagnosed at stage III or IV. Remarkably, although these patients had similar rates of recurrence compared with those in the other two groups, they had excellent DSS, with no tumor-related deaths. This category of HPV-independent tumors with normal p53 IHC has previously been described in the vulva,28,29 where they show similar behavior to that observed in our series of PSCC, with frequent recurrences but extremely good DSS.30

The most frequent category of PSCC in our study (60% of all HPV-independent tumors and 40% of all tumors) was HPV-independent/p53 abnormal PSCC. This percentage of abnormal p53 IHC results is similar to the percentage reported by other studies in HPV-independent PSCC.9,22 In contrast with the favorable DSS of patients with HPV-associated tumors and HPV-independent/p53 normal tumors, the prognosis of patients with HPV-independent/p53 abnormal PSCC is poor, with a 27% 5-year mortality. Importantly, the impaired DSS of this subgroup was confirmed through multivariate analysis. Our study confirmed that the pattern-based p53 IHC evaluation16 significantly improves the conventional evaluation of p53 IHC. In addition, this framework recognizes additional abnormal p53 patterns (null, cytoplasmic, and basal overexpression) usually misinterpreted as p53 normal (wild-type).31 As shown in this study, these patterns correlated with an adverse prognosis, as 7/14 deaths in the HPV-independent/p53 abnormal group were related to tumors showing p53 patterns not recognized through classic p53 IHC. These differences in p53 IHC results may explain the differences observed in previous studies regarding the prognostic impact of p53 IHC.32

Although the vast majority of HPV-associated PSCC showed a normal pattern of p53 expression, a small percentage of patients in our series (11%) exhibited an abnormal p53 IHC pattern. This finding has been previously described.19 Moreover, TP53 mutations have been detected in small percentages of HPV-associated PSCC6,8 and in HPV-associated tumors of other sites,33,34 indicating that abnormal TP53 (or abnormal p53 IHC) is not an exclusive finding of HPV-independent carcinomas. Interestingly, none of the patients with HPV-associated PSCC with an abnormal p53 IHC expression pattern died due to the disease, suggesting that TP53 mutation does not impair prognosis in this molecular category, although further studies including a greater number of HPV-associated tumors with abnormal p53 IHC staining are needed to reach strong conclusions. Finally, it should be emphasized that although in this study the correlation between p16 IHC overexpression and HPV detection was 100%, a percentage of around 10% of discrepant results has been reported in other studies focused on head and neck and vulvar tumors30 and that this phenomenon should also be expected as probably occurring in PSCC.

Interestingly, the presence of vascular invasion was the only factor associated with disease recurrence according to the multivariate analysis. This association is not surprising considering the previously reported association between vascular invasion and lymph node metastases in PSCC.35

Our study has several limitations. Due to the large time frame of inclusion, a significant number of patients, mainly from the initial period of inclusion, did not undergo inguinal staging using sentinel lymph node analysis; thus, some inguinal lymph node microscopic metastases could have been missed. Secondly, the results could not be corrected for the different treatments due to the small number of patients requiring adjuvant therapies. Thirdly, the small number of disease-related deaths in the series might have affected the strength of the statistical estimations. Finally, the pattern-based evaluation of p53 IHC has not been extensively validated in alternative PSCC cohorts. Thus, the results of this study should be confirmed in larger, more homogeneous cohorts.

CONCLUSION

We showed that patients with HPV-independent/p53 abnormal PSCC have adverse clinical outcomes than patients with HPV-associated and HPV-independent/p53 normal PSCC. p53 IHC defines 2 prognostic categories in HPV-independent PSCC: HPV-independent/p53 normal PSCC are low-risk tumors, whereas HPV-independent/p53 abnormal tumors can be considered aggressive neoplasms. Our study suggests that PSCC be stratified into 3 molecular types with distinct clinicopathological features and behaviors based on p16 (as a surrogate of HPV status) and p53 IHC (as a surrogate of TP53 mutational status) status. If these results are confirmed in prospective studies, they could help to refine the staging work-up, treatment schemes, and follow-up strategies for patients with PSCC.

Footnotes

ISGlobal receives support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation through the “Centro de Excelencia Severo Ochoa 2019-2023” Program (CEX2018-000806-S) and support from the Generalitat de Catalunya through the CERCA Program.

This manuscript was previously posted to Preprint.org: doi: https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202403.0996.v1.

All data used in this study are available and can be accessed upon reasonable request.

Adriana García-Herrera and Natalia Rakislova contributed equally and shared senior authorship.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: The authors have disclosed that they have no significant relationships with, or financial interest in, any commercial companies pertaining to this article.

Contributor Information

Isabel Trias, Email: itrias@clinic.cat.

Ferran Algaba, Email: falgaba@fundacio-puigvert.es.

Inés de Torres, Email: ines.detorres@vallhebron.cat.

Adela Saco, Email: masaco@clinic.cat.

Lorena Marimon, Email: lorena.marimon@isglobal.org.

Núria Peñuelas, Email: nuria.penuelas@isglobal.org.

Laia Diez-Ahijado, Email: laia.diez@isglobal.org.

Lia Sisuashvili, Email: lsisuash@clinic.cat.

Katarzyna Darecka, Email: kadarecka@clinic.cat.

Alba Morató, Email: alba.morato@isglobal.org.

Marta del Pino, Email: mdelpino@clinic.cat.

Carla Ferrándiz-Pulido, Email: carla.ferrandiz@vallhebron.cat.

María José Ribal, Email: mjribal@clinic.cat.

Tarek Ajami, Email: ajami@clinic.cat.

Juan Manuel Corral, Email: jmcorral@clinic.cat.

Josep Maria Gaya, Email: jmgaya@hotmail.com.

Oscar Reig, Email: oreig@clinic.cat.

Oriol Ordi, Email: oriol.ordi@gmail.com.

Inmaculada Ribera-Cortada, Email: itribera@clinic.cat.

Adriana García-Herrera, Email: apgarcia@clinic.cat.

Natalia Rakislova, Email: natalia.rakislova@isglobal.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Parza K, Mustasam A, Ionescu F, et al. The prognostic role of human papillomavirus and p16 status in penile squamous cell carcinoma—a systematic review. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ribera-Cortada I, Guerrero-Pineda J, Trias I, et al. Pathogenesis of penile squamous cell carcinoma: molecular update and systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borque-Fernando Á, Gaya JM, Esteban-Escaño LM, et al. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of penile cancer: results from the Spanish national registry of penile cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Douglawi A, Masterson TA. Penile cancer epidemiology and risk factors: a contemporary review. Curr Opin Urol. 2019;29:145–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menon S, Moch H, Berney DM, et al. WHO 2022 classification of penile and scrotal cancers: updates and evolution. Histopathology. 2023;82:508–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ermakov MS, Kashofer K, Regauer S. Different mutational landscapes in human papillomavirus–induced and human papillomavirus–independent invasive penile squamous cell cancers. Mod Pathol. 2023;36:100250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaux A, Velazquez E, Algaba F, et al. Developments in the pathology of penile squamous cell carcinomas. Urology. 2010;76:S7–S14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nazha B, Zhuang T, Wu S, et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of penile squamous cell carcinoma and the impact of human papillomavirus status on immune-checkpoint inhibitor-related biomarkers. Cancer. 2023;129:3884–3893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kashofer K, Winter E, Halbwedl I, et al. HPV-negative penile squamous cell carcinoma: disruptive mutations in the TP53 gene are common. Mod Pathol. 2017;30:1013–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feber A, Worth DC, Chakravarthy A, et al. CSN1 somatic mutations in penile squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2016;76:4720–4727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Wang K, Chen Y, et al. Mutational landscape of penile squamous cell carcinoma in a Chinese population. Int J Cancer. 2019;145:1280–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacob J, Ferry E, Gay L, et al. Comparative genomic profiling of refractory and metastatic penile and nonpenile cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: implications for selection of systemic therapy. J Urol. 2019;201:541–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopes A, Bezerra AL, Pinto CA, et al. p53 as a new prognostic factor for lymph node metastasis in penile carcinoma: analysis of 82 patients treated with amputation and bilateral lymphadenectomy. J Urol. 2002;168:81–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teixeira Júnior AAL, da Costa Melo SP, Pinho JD, et al. A comprehensive analysis of penile cancer in the region with the highest worldwide incidence reveals new insights into the disease. BMC Cancer. 2022;22:1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellizzi AM. p53 as exemplar next-generation immunohistochemical marker: a molecularly informed, pattern-based approach, methodological considerations, and pan-cancer diagnostic applications. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol AIMM. 2023;31:507–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trias I, Saco A, Marimon L, et al. P53 in penile squamous cell carcinoma: a pattern-based immunohistochemical framework with molecular correlation. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tessier-Cloutier B, Kortekaas KE, Thompson E, et al. Major p53 immunohistochemical patterns in in situ and invasive squamous cell carcinomas of the vulva and correlation with TP53 mutation status. Mod Pathol. 2020;33:1595–1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu JY, Li YH, Zhang ZL, et al. The risk factors for the presence of pelvic lymph node metastasis in penile squamous cell carcinoma patients with inguinal lymph node dissection. World J Urol. 2013;31:1519–1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zargar-Shoshtari K, Spiess PE, Berglund AE, et al. Clinical significance of p53 and p16ink4a status in a contemporary North American penile carcinoma cohort. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2016;14:346–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Darragh TM, Colgan TJ, Thomas Cox J, et al. The lower anogenital squamous terminology standardization project for HPV-associated lesions: background and consensus recommendations from the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2013;32:76–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kidd LC, Chaing S, Chipollini J, et al. Relationship between human papillomavirus and penile cancer-implications for prevention and treatment. Transl Androl Urol. 2017;6:791–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDaniel AS, Hovelson DH, Cani AK, et al. Genomic profiling of penile squamous cell carcinoma reveals new opportunities for targeted therapy. Cancer Res. 2015;75:5219–5227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrandiz-Pulido C, Masferrer E, Toll A, et al. mTOR signaling pathway in penile squamous cell carcinoma: pmTOR and peIF4E overexpression correlate with aggressive tumor behavior. J Urol. 2013;190:2288–2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou X, Wang X. Radioimmunotherapy in HPV-associated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Biomedicines. 2022;10:1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szymonowicz KA, Chen J. Biological and clinical aspects of HPV-related cancers. Cancer Biol Med. 2020;17:864–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Visser O, Adolfsson J, Rossi S, et al. Incidence and survival of rare urogenital cancers in Europe. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:456–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohanty SK, Mishra SK, Bhardwaj N, et al. p53 and p16ink4a as predictive and prognostic biomarkers for nodal metastasis and survival in a contemporary cohort of penile squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2021;19:510–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nooij LS, Ter Haar NT, Ruano D, et al. Genomic characterization of vulvar (pre)cancers identifies distinct molecular subtypes with prognostic significance. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:6781–6789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kortekaas KE, Bastiaannet E, van Doorn HC, et al. Vulvar cancer subclassification by HPV and p53 status results in three clinically distinct subtypes. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;159:649–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carreras-Dieguez N, Saco A, del Pino M, et al. Human papillomavirus and p53 status define three types of vulvar squamous cell carcinomas with distinct clinical, pathological, and prognostic features. Histopathology. 2023;83:17–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowie J, Singh S, O’hanlon C, et al. A systematic review of non-HPV prognostic biomarkers used in penile squamous cell carcinoma. Turkish J Urol. 2021;47:358–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yanagawa N, Osakabe M, Hayashi M, et al. Detection of HPV-DNA, p53 alterations, and methylation in penile squamous cell carcinoma in Japanese men. Pathol Int. 2008;58:477–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Westra WH, Taube JM, Poeta ML, et al. Inverse relationship between human papillomavirus-16 infection and disruptive p53 gene mutations in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:366–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zięba S, Kowalik A, Zalewski K, et al. Somatic mutation profiling of vulvar cancer: Exploring therapeutic targets. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;150:552–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slaton JW, Morgenstern N, Levy DA, et al. Tumor stage, vascular invasion and the percentage of poorly differentiated cancer: independent prognosticators for inguinal lymph node metastasis in penile squamous cancer. J Urol. 2001;165:1138–1142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]