Abstract

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection in vivo is dependent upon the interaction of the viral envelope glycoprotein gp120 with CC chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) or CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4). To study the determinants of the gp120-coreceptor association, we generated a set of chimeric HIV-1 coreceptors which express all possible combinations of the four extracellular domains of CCR5 and CXCR4. Stable U87 astroglioma cell lines expressing CD4 and individual chimeric coreceptor proteins were tested against a variety of R5, X4, and R5X4 envelope glycoproteins and virus strains for their ability to support HIV-1-mediated cell fusion and infection, respectively. Each of the cell lines promoted fusion with cells expressing an HIV envelope glycoprotein, except for U87.CD4.5455, which presents the first extracellular loop (ECL1) and flanking sequences of CXCR4 in the context of CCR5. However, all of the chimeric coreceptors allowed productive infection by one or more of the viral strains tested. Viral phenotype was a predictive factor for the observed activity of the chimeric molecules; X4 and R5X4 HIV strains utilized a majority of the chimeras, while R5 strains were limited in their ability to infect cells expressing these chimeric molecules. The expression of CCR5 ECL2 within the CXCR4 backbone supported infection by an R5 primary isolate, but no chimeras bearing the N terminus of CCR5 exhibited activity with R5 strains. Remarkably, the introduction of any CXCR4 domain into the CCR5 backbone was sufficient to allow utilization by multiple X4 strains. However, critical determinants within ECL2 and/or ECL3 of CXCR4 were apparent for all X4 viruses upon replacement of these domains in CXCR4 with CCR5 sequences. Unexpectedly, chimeric coreceptor-facilitated entry was blocked in all cases by the presence of the CXCR4-specific inhibitor AMD3100. Our data provide proof that CCR5 contains elements that support usage by X4 viral strains and demonstrate that the gp120 interaction sites of CCR5 and CXCR4 are structurally related.

In a critical sequence of events leading to viral entry, the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) surface glycoprotein, gp120, binds its primary cellular receptor CD4 and undergoes a conformational change that exposes a coreceptor binding site (3). Subsequent binding of gp120 to a chemokine receptor coreceptor allows fusion of viral and cellular membranes to occur. The function performed by the binding of gp120 to a coreceptor in promoting membrane fusion is unknown, but it is evident that productive infection of the host ultimately depends on this association (15).

The chemokine receptors CCR5 and CXCR4 are the predominant coreceptors for HIV-1 in vivo, and all HIV-1 strains are now classified phenotypically as R5, X4, or R5X4 depending on whether they preferentially utilize CCR5, CXCR4, or either, respectively (3). R5 strains are the predominant species transmitted and may be isolated at any stage of HIV infection. X4 viruses evolve in a subset of patients through mutations in the envelope gene, and their emergence is associated with an accelerated course of disease (12, 37, 42, 44). This capacity to alter coreceptor usage increases the number of CD4+ cell populations that are susceptible to HIV infection and complicates the development of antiviral strategies targeting HIV coreceptors in vivo. Additionally, viruses may switch coreceptor in the presence of CCR5- or CXCR4-specific chemokines or small molecule inhibitors in vivo and in vitro (19, 38, 42), and replication of X4 virus in the presence of chemokine or bicyclam ligands can force the emergence of escape mutants with unaltered coreceptor usage (43). To counteract this adaptability we need to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the interaction of gp120 with CCR5 and CXCR4, which should facilitate the development of more precise and effective coreceptor antagonists. Furthermore, by investigating the similarities and differences in the ways these chemokine receptors associate with gp120 and CD4, we may be able to define requirements for a universal HIV coreceptor inhibitor.

As members of the seven transmembrane domain G protein-coupled receptor superfamily, CCR5 and CXCR4 share common structural features, including an extracellular N terminus, three extracellular loops (ECLs), three intracellular loops, and an intracellular C-terminal tail (3). The chemokine receptor and HIV-1 coreceptor functions are separable for both proteins; although the binding sites for chemokine ligands and gp120 overlap, they are discrete (1, 6, 17, 20, 26, 35, 50). An additional site in each protein for interaction with CD4 is suggested by the results of coimmunoprecipitation (34, 51) and colocalization (46) studies. CCR5 appears to be constitutively associated with CD4 (51), while the interaction of CXCR4 and CD4 requires the presence of gp120 (46). Although CCR5 and CXCR4 perform essentially the same function in HIV entry and promote infection with similar efficiency, their mode of interaction with the envelope glycoprotein differs, and the affinity of gp120 for CCR5 may be significantly higher than that for CXCR4 (17, 28).

The gp120 binding site is a complex structure formed primarily by the extracellular domains of the coreceptor molecule, and interactions with this site on CCR5 and CXCR4 are notably strain dependent (3). Studies utilizing chimeric and mutated chemokine receptors have failed to reveal a common mechanism for the association of gp120 with either CCR5 or CXCR4, although certain regions, found mainly within the N terminus and ECL2, appear to contribute significantly to gp120 recognition (4–8, 10, 16, 21, 31, 35, 40, 41, 47, 48, 50). The importance of these domains is also suggested by the ability of targeted peptides and monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) to inhibit infection by certain viral strains (23, 29, 35, 50). Mutations of specific tyrosine residues in the N-terminal region of CCR5 (Y15A) (40) and CXCR4 (Y7A, Y12A) (6) impair viral entry, yet deletions of these residues in CXCR4 through N-terminal truncation can be tolerated (7). Multiple acidic amino acid residues in the N-terminal regions of CCR5 and CXCR4 and especially in ECL2 of CXCR4 have been predicted to form electrostatic associations with basic residues in the hypervariable regions of gp120 (4, 18, 31). Mutational analyses have both supported and contradicted this hypothesis (4, 5, 8, 31, 48). Interestingly, substitution with the CCR5 N-terminal region (36) or a D187A point mutation in ECL2 (8, 10, 48) allows CXCR4 to function as a coreceptor for certain R5 HIV-1 strains, suggesting that the CXCR4 structure contains the determinants for R5 gp120 binding. The converse has not been demonstrated for CCR5, however. Either replacement of the CCR5 N terminus with the CXCR4 N-terminal domain (27, 48) or introduction of aspartic acid into the corresponding position in ECL2 of CCR5 (8) abolishes or greatly diminishes CCR5 coreceptor function.

To investigate the functional differences between CCR5 and CXCR4 we generated a set of chimeric coreceptors for stable expression in the coreceptor negative cell line U87.CD4. Because we wished to address the question of coreceptor specificity, we focused on replacing the extracellular domains, although the substituted regions included transmembrane and intracellular sequences as well. Each coreceptor-expressing cell line was susceptible to HIV-1-mediated cell fusion and infection. We demonstrate common coreceptor usage patterns evident for a diverse panel of X4 viruses and show that entry of X4 and R5X4 viruses into our chimeric coreceptor cell lines was blocked by the CXCR4-specific inhibitor AMD3100. Our data clearly demonstrate that the CCR5 molecule contains features that allow utilization by all X4 viral strains tested. These findings suggest that a common mechanism underlies the gp120-coreceptor interaction, regardless of viral phenotype.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

U87MG-CD4 (U87.CD4) cells were obtained from the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program and were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)–4 mM l-glutamine–1 mM sodium pyruvate–100 units of penicillin per ml–100 μg of streptomycin per ml (complete DMEM; WUMS Tissue Culture Support Center) supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 200 μg of Geneticin per ml (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.). BSC40 and 293T cells were maintained in complete DMEM containing 10% FBS. Human peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) were isolated on Ficoll-Hypaque from concentrated lympho-platelets obtained from normal donors by pheresis (BJC Hospital, St. Louis, Mo.). Human PBL were stimulated in complete RPMI medium containing 10% FBS and 10 μg of phytohemagglutinin per ml for 3 days and then were maintained in complete RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 50 units of interleukin 2 per ml.

Viruses.

Recombinant vaccinia viruses expressing LacZ (vCB21R), T7 polymerase (vPT7-3), CD4 (vCB-3), and HIV-1 envelopes from the JR-FL (vCB-28) and SF162 (vCB-32) strains were obtained from the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program. Vaccinia viruses encoding an uncleaved HIV envelope (UNC; vCB-16), ADA envelope (vCB-39), and HXB2 envelope (vSC60) were a gift from Edward Berger. Recombinant vaccinia viruses encoding the HIV envelopes from the YU2 (vSP-5), 89.6 (vDC-1), and UG92046 (vCB-51) strains were a gift from Christopher Broder. The R5, X4, and R5X4 HIV-1 primary isolates utilized for infection were obtained from the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program. All R5 and R5X4 viruses utilized and the X4 strains HXB2 and HT92599 are envelope subtype B. The envelope subtypes of the remaining X4 isolates are as follows: CMU08, subtype B; UG92029, subtype A; UG92021, UG93053, and UG93059, subtype D.

CCR5/CXCR4 chimeric constructs.

CCR5 lacking a termination codon and flanked by NheI and NotI restriction sites was generated by PCR using pBBS-CCR5 (from Stephen Peiper) as a template. A plasmid encoding a variant of green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Green Lantern Protein; Gibco BRL) was used as a template for PCR to produce GFP cDNA lacking an initiation codon and flanked by NotI and HindIII sites. The DNA encoding CCR5 and GFP was digested, ligated into the NheI and HindIII restriction sites of pBK-CMV (Stratagene), and sequenced. To assemble chimeras, CXCR4 cassettes were generated by PCR using human PBL cDNA as a template. CXCR4 cassettes were engineered by site-directed mutagenesis to contain NspI, ClaI, and EcoRI restriction sites at nucleotides 168, 394, and 798, respectively, in addition to flanking NheI and HindIII restriction sites. CXCR4 PCR products and CCR5-GFP were digested with appropriate enzyme pairs and ligated to produce CCR5/CXCR4 chimeras expressing all possible combinations of the four segments. The four nucleotide sequences exchanged correspond to the following stretches of amino acids in CXCR4: I, amino acids (aa) 1 to 53; II, aa 54 to 131; III, aa 132 to 267; and IV, aa 268 to 352. The substituted regions of CCR5 were as follows: 1, aa 1 to 45; 2, aa 46 to 123; 3, aa 124 to 263; and 4, aa 264 to 352.

Stable CCR5/CXCR4 chimera-expressing cell lines.

To produce U87.CD4 cell lines with stable expression of the chimeric coreceptors, the constructs were digested with NheI and HindIII, treated with Klenow, and blunt-end ligated into the retroviral vector pBABE (received as a gift from Dan Littman), which carries the gene for puromycin resistance. U87.CD4 cells were transfected with coreceptor DNA using Lipofectamine (Gibco BRL) and then selected in media containing 1 μg of puromycin per ml for 3 weeks. Bulk selected cells were stained with anti-CD4-phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled antibody (Calbiochem, La Jolla, Calif.) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5% FBS according to the manufacturer's directions and sorted (WUMS Flow Cytometry Facility) with a gate on cells expressing the highest levels of GFP and PE fluorescence. Cells were collected and maintained in media supplemented with 200 μg of Geneticin and 1 μg of puromycin per ml.

For confocal microscopy, stable cell lines were cultured in multiwell chamber slides and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at 25°C. Some slides were stained with anti-CD4-PE antibody as described above. Cells were viewed with a Zeiss axiovert microscope using a Bio-Rad confocal scanning imaging system.

Envelope-dependent fusion assay.

Coreceptor-expressing cell lines were tested for their ability to support HIV-1 envelope-mediated fusion using a modification of the assay developed in Edward Berger's laboratory (39). Briefly, the U87.CD4 cell lines were infected with vCB21R. Fusion partner BSC40 cells were infected with vPT7-3 and one of several HIV-1 envelope-expressing recombinant vaccinia viruses. Cells were infected for 1 h (multiplicity of infection, 1) at 37°C in PBS containing 1% FBS and 2 mM MgCl2. Infected cells were cultured overnight, trypsinized lightly, and washed prior to mixing. For fusion, 105 cells were mixed 1:1 with a fusion partner in DMEM containing 5% FBS in triplicate wells and incubated 3 h at 37°C. Fusion was stopped by addition of NP-40 to a final concentration of 1% and a single round of freeze-thaw. β-galactosidase activity of reaction lysates was determined using chlorophenol red–β-d-galactopyranoside (Calbiochem) as described previously (24). The absorbance of each sample was determined at a wavelength of 590 nm.

HIV-1 luciferase reporter virus infection assay.

To generate the luciferase reporter viruses, we utilized pNLluc E−R+, which encodes the firefly luciferase gene in place of Nef within the HIVNL43 sequence (11). The lab-adapted HXB2 envelope gene and several chimeric envelope constructs generated previously in our laboratory (30, 49) were substituted for the pNLluc E−R+ env, utilizing the unique SalI and BamHI restriction sites for digestion and ligation. The chimeric envelopes express the V3 loop of R5 (ADA, SF162, YU2) and R5X4 (SF2) strains within the HXB2 backbone. To produce the 89.6 reporter virus we inserted the SalI/BsaBI fragment of the R5X4 strain 89.6 into the corresponding sites of the HXB2-luciferase construct. The coreceptor usage phenotype of each envelope construct was characterized previously in our laboratory (30), with the exception of 89.6, which exhibited the expected R5X4 phenotype (see Results). In addition to the full-length proviral reporter clones, we generated a pseudotyped HIV luciferase reporter virus by cotransfection of pNLluc E−R+ and a plasmid encoding the vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) envelope glycoprotein, VSV-g, as described below for preparation of viral stocks.

Viral stocks were prepared by lipofection of 293T cells, and the harvested supernatants were analyzed by p24 antigen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Beckman-Coulter, Fullerton, Calif.). Cells were seeded in 24-well plates (5 × 104 cells per well) and cultured overnight prior to infection. Following an incubation with 20 to 100 ng of p24 in the presence of 20 μg of DEAE-dextran per ml of complete DMEM for 6 h, the cells were washed and fed fresh media. At 48 h postinfection (p.i.), culture supernatants were aspirated and cells were lysed in PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100 (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). Luciferase activity of cell lysates was assayed in an Optocomp luminometer as described previously (45). To confirm equal cell numbers for each cell type in all infection assays, including those performed with primary isolates, additional wells of cells were infected with 0.1 ng of p24 of the VSV-g-luciferase and assayed 48 h p.i. for luciferase activity with similar results for all cell lines. In experiments utilizing the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100, cells were pretreated with the drug for 30 min prior to viral adsorption, and the inhibitor was present throughout the remainder of the experiment.

HIV-1 primary isolate infection assay.

To generate viral stocks, phytohemagglutinin-stimulated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were inoculated with 1 ml of primary isolate stocks with various titers. Cells were fed fresh media every 3 to 4 days, and supernatants were harvested 7 and 10 days p.i. (d.p.i.). The p24 antigen content of each stock was quantitated by p24 antigen ELISA. Infections were performed with chimera-expressing U87.CD4 as described for the reporter viruses, except that the viral inoculum contained 2 to 10 ng of p24 and cells were washed extensively following the adsorption period to remove residual input virus. To assess viral infectivity, the p24 content of supernatants collected 2, 5, or 8 d.p.i. was quantitated by ELISA, and cell cultures were scored for the presence of syncytia 5 d.p.i. Infections with AMD3100 followed the protocol given for the reporter viruses.

RESULTS

Generation of CCR5/CXCR4 chimeric constructs and stable cell lines.

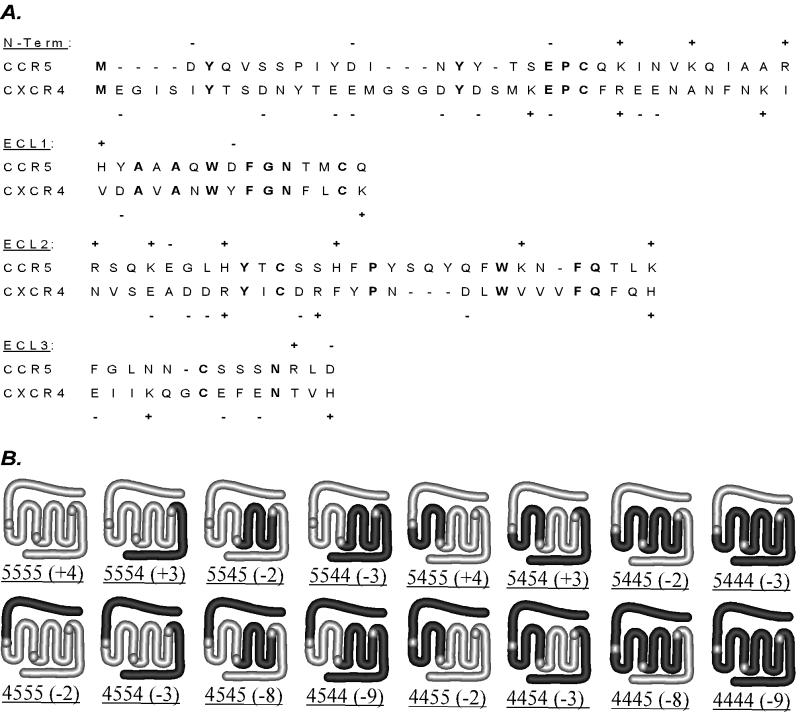

To study the structural determinants of coreceptor specificity, we constructed a set of chimeric coreceptors expressing all possible combinations of the four extracellular domains from CCR5 and CXCR4. For the analysis of coreceptor localization and expression levels, all the constructs were tagged at the C-terminal end with GFP. To generate the chimeric constructs, three unique restriction sites within the CCR5 cDNA which effectively separate the four encoded extracellular domains were engineered into similar positions in the CXCR4 sequence by site-directed mutagenesis. Restriction enzyme digest of CXCR4 PCR products yielded four cassettes for the exchange of CXCR4 and CCR5 sequences. The amino acid sequence of the predicted extracellular region encoded by each cassette was aligned with the corresponding CCR5 sequence as shown in Fig. 1A. The entire sequence of each extracellular domain was contained within a single cassette except for ECL3, for which the first three amino acids were encoded by cassette 3, with the remainder encoded by cassette 4. As depicted graphically in Fig. 1B, the structures produced from each cassette included the following: (i) the extracellular N terminus and first transmembrane (TM) domain; (ii) the first intracellular loop, the second and third TM domains, and ECL1; (iii) ECL2, the second and third intracellular loops, and TM domains 4 to 6; and (iv) ECL3, the seventh TM domain, and the C-terminal tail. As indicated, chimeras were named by listing the parental coreceptor for each segment in order, with CCR5-GFP represented by 5555 and CXCR4-GFP represented by 4444. The total charges of the extracellular domains were derived using the sequences given in Fig. 1A and ranged from −9 to +4 (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

(A) Amino acid sequences of putative extracellular domains of CCR5 and CXCR4 contained within the four substituted regions were aligned using Jellyfish software (Biowire). Sequence identity is highlighted in bold type. Charged amino acid residues are indicated. (B) Schematic representations of CCR5, CXCR4, and the CCR5/CXCR4 chimeras. The total charge of the extracellular domains is shown for each chimera. Chimera nomenclature is described in the text.

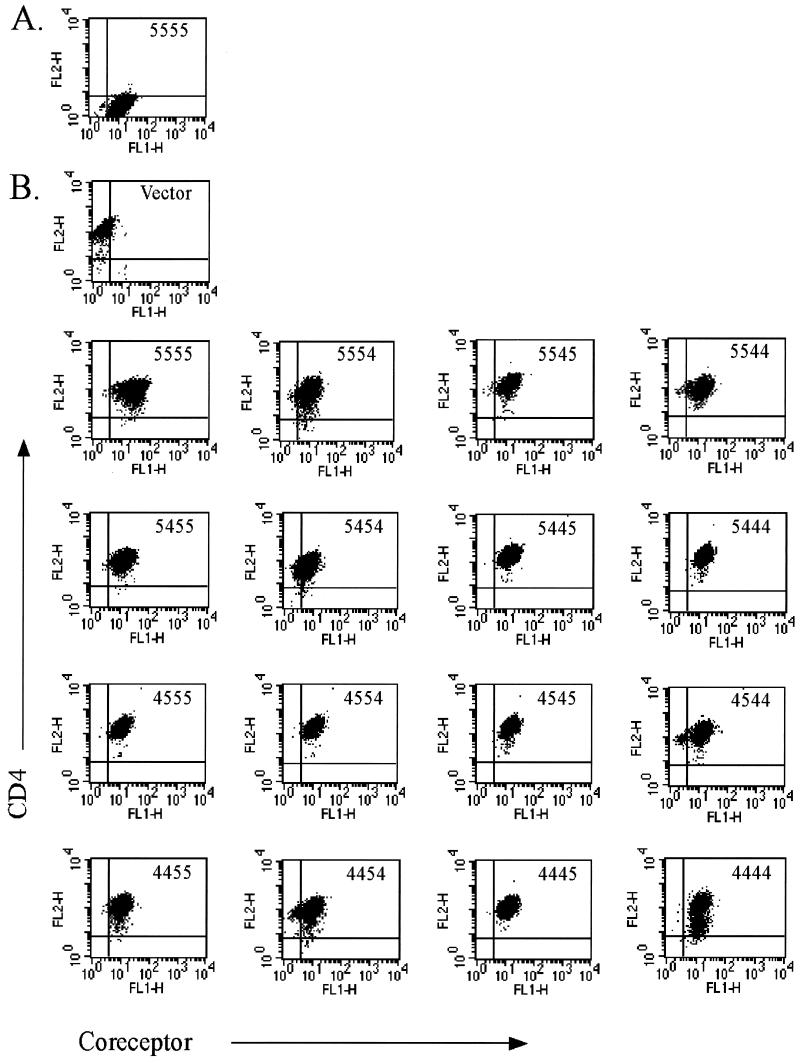

Preliminary experiments utilizing transiently transfected cells demonstrated that consistent expression levels were critical to the assessment of CCR5/CXCR4 chimeric coreceptor activity (data not shown). In addition, we observed that transient transfection did not allow for accurate normalization of coreceptor and CD4 cell surface expression. To address these issues we produced puromycin-resistant transfectants using the HIV coreceptor-negative astroglioma cell line U87.CD4. Stable chimera-expressing cell populations were sorted for high levels of GFP fluorescence and CD4 cell surface immunostaining as assessed during flow cytometry. The cell lines chosen for characterization of coreceptor activity were closely matched for chimeric coreceptor and CD4 expression levels, as shown in Fig. 2. The average mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for total GFP expression was 14.55 ± 3.8 (standard deviation) for the coreceptor-expressing cells versus 2.04 for the vector control cells. Cell surface CD4 staining yielded an average MFI of 149.20 ± 36.1 for all cells.

FIG. 2.

Flow cytometric analysis of stable coreceptor-expressing cell lines. U87.CD4 cell lines were stained with control immunoglobulin G-PE (A) or anti-CD4-PE antibody (B) and analyzed for GFP (FL1) and PE (FL2) fluorescence in a flow cytometer. The coreceptor construct expressed by each cell line is indicated in the upper right corner of each panel. Control U87 CD4 cells express vector alone.

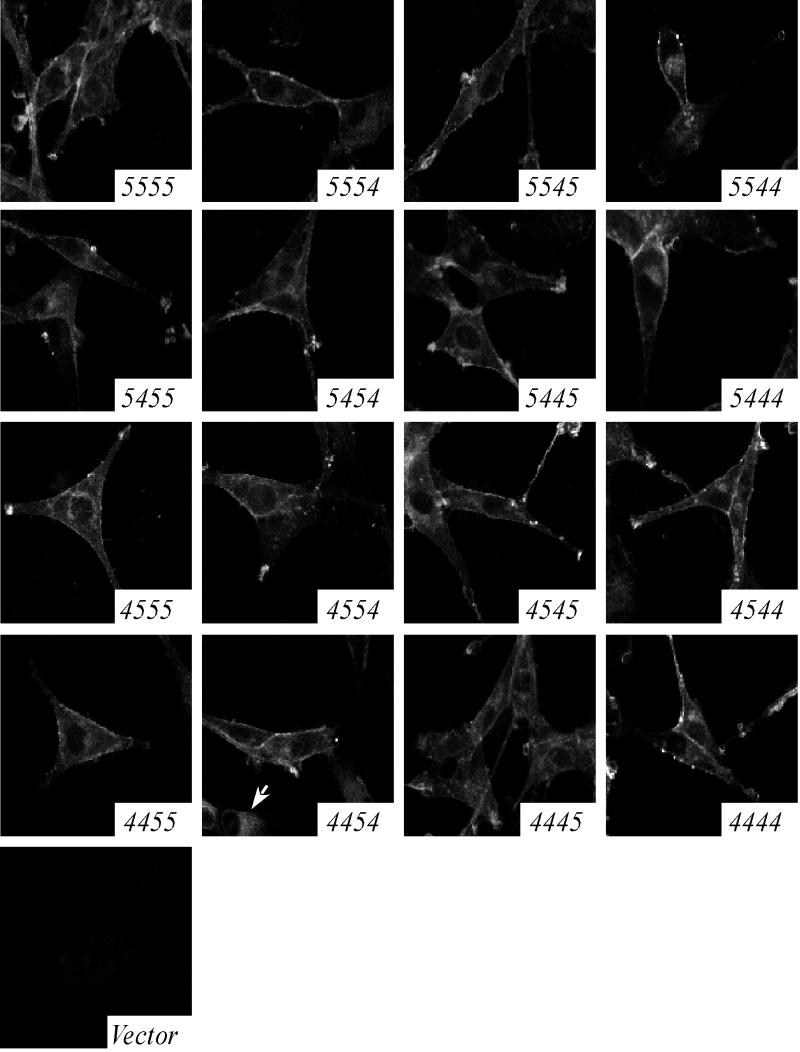

Direct assessment of cell surface levels of the parental coreceptors on our cell lines by flow cytometry required labeling with a cocktail of antibodies directed against multiple epitopes of the coreceptor molecules (data not shown). This observation suggested that the amount of coreceptor at the surface of the cell lines was lower than that of primary human monocyte-derived macrophages, which are readily labeled by single MAbs directed against CCR5 or CXCR4, as shown previously in our laboratory (29). Furthermore, certain chimeric coreceptors lacked epitopes recognized by commercially available antibodies. Therefore, to compare coreceptor cell surface expression levels, the subcellular distribution of the GFP-coreceptors was observed directly by confocal microscopy (Fig. 3). As expected, the fluorescence intensity was consistent across all cell populations, which were visually indistinguishable from each other, except for the two lines noted below. In each cell line, the chimeric coreceptors were localized at the plasma membrane and intracellularly. The cell surface fluorescence pattern was both evenly distributed across the cell surface and concentrated in distinct, bright patches, especially at the tips of cellular processes. Intracellular fluorescence was distributed in a perinuclear and vesicular pattern consistent with the biosynthetic pathway of membrane proteins. One exception was the 4454 cell line, which exhibited both a plasma membrane-perinuclear distribution and a second, entirely intracellular fluorescence pattern (Fig. 3). The 4445 cell line exhibited slightly reduced fluorescence intensity at the cell surface compared to the other cell lines. Immunofluorescent confocal microscopy also revealed consistently high plasma membrane localization of CD4 for all cell lines, often colocalized with coreceptor (data not shown). We concluded that these cell lines were accurately normalized for chimeric coreceptor and CD4 expression levels and that each chimeric construct was properly synthesized, correctly folded, and transported to the cell surface.

FIG. 3.

Subcellular localization of CCR5/CXCR4 chimeric coreceptors. U87.CD4 cell lines were fixed and viewed by confocal microscopy. The chimeric coreceptor expressed by each cell line is indicated in the lower right corner of each panel. Some cells expressing 4454 exhibit an entirely intracellular fluorescence pattern (arrow).

Activity of chimeric coreceptors in envelope-dependent cell fusion.

To assess the abilities of the chimeric coreceptors to promote membrane fusion, we mixed the CCR5/CXCR4 chimera cell lines with BSC40 cells expressing a panel of vaccinia-encoded HIV envelope glycoproteins. In addition, the BSC40 and chimera-expressing cells were infected with recombinant vaccinia viruses carrying either the T7 polymerase gene or the lacZ gene linked downstream of the T7 promoter, respectively. Positive fusion events resulted in the mixing of cellular contents and expression of the lacZ gene and were monitored by a colorimetric assay for β-galactosidase activity. Background levels of fusion were determined by using either BSC40 cells expressing an uncleaved envelope glycoprotein defective in fusion activity or vector control cells which express only CD4.

Results of one representative experiment are shown in Table 1. Each of the CCR5/CXCR4 chimeric coreceptors proved functional, promoting fusion with at least one of the envelope glycoproteins tested. The cells expressing X4 envelopes fused with 11 of 14 chimera-expressing cell lines at high levels, yielding >70% of the β-galactosidase activity obtained with U87.CD4.4444. Of the remaining lines, cells expressing 5455 and 4454 consistently promoted low levels of fusion with the HXB2 envelope, just 10 and 30% of that obtained with U87.CD4.4444, respectively. U87.CD4.4445 did not support fusion with cells expressing X4 viral envelopes. However, 4445 and 4454 permitted >60% of the fusion obtained using U87.CD4.4444 cells when the fusion partner expressed the 89.6 R5X4 envelope. In total, 8 of 14 chimera-expressing cell lines were able to fuse with cells displaying the R5X4 viral envelope at levels similar to those achieved with U87.CD4.4444 or U87.CD4.5555. For the remaining cell lines, 10 to 30% of the fusion seen with U87.CD4.4444 was observed with cells expressing 5544, 5455, 5445, and 4455, whereas cells expressing 5454 and 4544 did not support fusion with the R5X4 envelope glycoprotein. None of the chimeras exhibited activity with the R5 envelope glycoproteins, which allowed fusion only when U87.CD4 expressed the 5555 protein.

TABLE 1.

Relative activity of CCR5/CXCR4 chimeric coreceptor cell lines in HIV envelope-dependent cell fusion

| Coreceptor |

a HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein fusion activitya

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON

|

X4

|

R5

|

R5X4

|

||||

| UNC | HXB2 | UG92046 | ADA | JR-F1 | SF162 | 89.6 | |

| 5555 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 1.83 | 0.50 | 1.6 | 1.44 |

| 4444 | 0.07 | 2.05 | 0.48 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.57 |

| 4555 | 0.06 | 1.76 | 0.47 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 1.29 |

| 5455 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.16 |

| 5545 | 0.06 | 2.10 | 0.62 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.83 |

| 5554 | 0.02 | 1.48 | 0.36 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.37 |

| 5444 | 0.04 | 1.96 | 0.56 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.55 |

| 4544 | 0.04 | 1.86 | 0.33 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| 4454 | 0.02 | 0.62 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.36 |

| 4445 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.38 |

| 5544 | 0.05 | 1.61 | 0.44 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.10 |

| 5454 | 0.06 | 2.01 | 0.49 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| 5445 | 0.04 | 1.72 | 0.71 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.16 |

| 4554 | 0.02 | 2.18 | 0.78 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.56 |

| 4545 | 0.05 | 2.40 | 0.51 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.80 |

| 4455 | 0.02 | 1.90 | 0.43 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.10 |

| Vector | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

Values represent averages from one of four representative experiments of triplicate wells in which one-fifth of the total reaction lysate was assayed for absorbance at 590 nm for β-galactosidase activity using chlorophenol-red-galactylpyranoside as substrate. Standard deviations ranged from 1 to 16% of the averages. CON, control; UNC, uncleaved envelope glycoprotein. Values in bold, >15% of full activity with parental coreceptor.

Activities of chimeric coreceptors in infection by HIV-1 reporter viruses.

The CCR5/CXCR4 chimera cell lines were assayed for their ability to support infection by a panel of luciferase reporter viruses expressing V3 loop chimeric envelopes (Table 2). In this highly sensitive assay, 13 of 14 chimera-expressing cell lines were efficiently targeted by the HXB2 reporter virus, including U87.CD4.5455, which promoted low levels of fusion with HXB2 envelope-expressing cells. Therefore, HXB2 was able to utilize CCR5 as a coreceptor for infection upon substitution of any single CXCR4 domain. This virus was not utilizing single CXCR4 domains for entry, however, as U87.CD4.4445 was refractory to infection by HXB2 virus, although this line was readily infected by the 89.6 virus stock. The 89.6 reporter virus infected every chimera-expressing cell line. A second R5X4 virus, expressing the V3 loop of the SF2 envelope, exhibited infectivity for 8 of 14 chimeric coreceptor cell lines, suggesting that this virus was less tolerant of changes in coreceptor sequence than was the 89.6 reporter virus. Consistent with the results of the fusion assay, none of the chimera-expressing cell lines allowed infection by viruses displaying R5 envelope proteins.

TABLE 2.

Infection of CCR5/CXCR4 chimeric coreceptor cell lines by HIV-1 luciferase reporter viruses

| Coreceptor | HIV-1 luciferase reporter activitya

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X4

|

R5

|

R5X4

|

||||

| HXB2 | ADAV3 | YU2V3 | SF162V3 | SF2V3 | 89.6 | |

| 5555 | 0.9 | 3140 | 3720 | 6470 | 5,665 | 476 |

| 4444 | 486 | 0.1 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 2,470 | 4,770 |

| 5444 | 3,890 | 5.2 | 8.1 | 2.1 | 132 | 5,410 |

| 5455 | 3,540 | 3.5 | 17 | 7.6 | 14 | 5,260 |

| 5545 | 247 | 2.3 | 14 | 2.2 | 4.6 | 4,890 |

| 5554 | 4,320 | 4.2 | 36 | 2.4 | 57 | 4,480 |

| 4555 | 4,520 | 3.2 | 6.2 | 1.6 | 5,660 | 947 |

| 4544 | 3,452 | 3.3 | 3.8 | 5.3 | 378 | 7,630 |

| 4454 | 2,140 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 439 | 1,280 |

| 4445 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 2.2 | 1.4 | 6.1 | 1,530 |

| 5544 | 3,340 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 788 | 735 |

| 5454 | 3,360 | 3.0 | 9.4 | 4.7 | 4,110 | 2,310 |

| 5445 | 5,780 | 5.1 | 15 | 7.3 | 4,640 | 966 |

| 4554 | 7,680 | 5.1 | 33 | 3.8 | 6,390 | 4,230 |

| 4545 | 1,000 | 1.0 | 26 | 2.8 | 8.7 | 4,170 |

| 4455 | 5,630 | 3.1 | 5.1 | 1.2 | 4,130 | 1,220 |

| Vector | 2.0 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 4.7 | 3.1 | 4.8 |

Values of luciferase activity (RLU) are averages of triplicate wells from one of three representative experiments. Standard deviations ranged from 3 to 18%.

Activities of chimeric coreceptors in infection by HIV-1 primary isolates.

To determine whether the use of lab-adapted X4 or chimeric R5 and R5X4 envelope glycoproteins had affected the outcome of the reporter virus assay, we infected the U87.CD4 cell lines with several X4, R5, and R5X4 HIV-1 primary isolates. The kinetics of infection varied with both virus and coreceptor; at early time points some positive cultures failed to produce p24 antigen in quantities detectable above the background of input virus, while at later time points other cultures were characterized by abundant syncytium formation, cell death, and low p24 content in the media (data not shown). Therefore, positive infection was detected by p24 antigen ELISA of supernatants and by observation of syncytium formation. Results from a representative experiment, in which cells were assessed for infection on day 8 p.i., are shown in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Infection of CCR5/CXCR4 chimera cell lines by HIV-1 primary isolates

| Coreceptor | p24/syncytium formationa

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X4

|

R5

|

R5X4

|

||||||||

| HT92599 | UG93053 | UG92021 | UG92029 | CMU08 | UG93059 | BaL | SF162 | BR93019 | 89.6 | |

| 5555 | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | +/+ | +/− | +/+ | −/− |

| 4444 | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | +/+ | +/+ |

| 4555 | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | −/− | −/+ | −/− | +/− | −/− | −/+ |

| 5455 | +/+ | +/+ | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− |

| 5545 | −/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | −/+ | −/+ | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− |

| 5554 | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | −/+ | +/+ | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/+ |

| 5444 | +/+ | +/+ | −/+ | −/+ | −/+ | −/+ | −/− | −/− | −/− | +/+ |

| 4544 | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | −/+ | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/+ |

| 4454 | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | +/− | −/− | −/− | +/− | −/− | +/− |

| 4445 | −/− | +/+ | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− |

| 5544 | +/+ | +/+ | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− |

| 5454 | −/+ | +/+ | −/+ | −/+ | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− |

| 5445 | −/+ | +/+ | −/+ | −/+ | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | +/− |

| 4554 | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− |

| 4545 | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | −/− | −/+ | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/+ |

| 4455 | +/+ | +/+ | −/+ | +/+ | −/+ | −/− | −/− | −/+ | −/− | +/+ |

| Vector | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− |

Positive p24 content ranged from 40 to 160 ng/ml; negative p24 values were <2 ng/ml. Syncytium formation in the cultures was scored, with positive cultures containing >15 syncytia/well and negative cultures containing ≤1 syncytium/well. These values are averages of duplicate wells, from one of two representative experiments.

Chimera-expressing U87.CD4 were highly susceptible to the X4 primary isolates, with each line productively infected by at least one of the strains. Two X4 strains, HT92599 and UG93053, were able to utilize any single domain of CXCR4 expressed within CCR5, infecting cells expressing 4555, 5455, 5545, or 5554. These same strains were sensitive to exchanges of the third or fourth extracellular domains of CXCR4 with CCR5 domains; UG93053 was inactive with 4454, and HT92599 could not utilize either 4454 or 4445 for entry. Similarly, viral strains UG92021 and UG92029 infected cells expressing 4555, 5545, or 5554, were critically dependent on ECLs 2 and 3 of CXCR4, and were not affected by N-terminal substitution in 5444. The interactions of UG92021 and UG92029 with CXCR4 were independent of ECL1; however; no activity was detected with 5455, while cells expressing 4544 were infected. Two X4 strains, CMU08 and UG93059, exhibited a more restricted pattern of chimeric coreceptor usage.

The R5X4 isolates also utilized the chimeras distinctly. While 89.6 infected 8 of 14 chimera-expressing cell lines, BR93019 infected only U87.CD4.5555 and U87.CD4.4444. Cell lines expressing 4555, 4455, 4454, or 5555 were productively infected by the R5 primary isolate SF162. In the 4555- and 4454-infected cultures, p24 values were commensurate with those generated by U87.CD4.5555. The high level of syncytium formation and cell death observed with U87.CD4.4455 in this experiment indicated that the peak of p24 production by these cells had passed. In contrast to the SF162 isolate, only U87.CD4.5555 was infected by the BaL stock.

Inhibition of chimera coreceptor activity by AMD3100.

To investigate the mechanism behind the plasticity of the X4 envelope interaction with the CCR5/CXCR4 chimeras, we tested the efficacy of AMD3100 inhibition of infection. U87.CD4 cell lines were preincubated for 30 min with AMD3100 (1 μM) prior to infection with the SF162V3, HXB2, and 89.6 reporter viruses (20 ng of p24 per well) or the primary isolates HT92599 and UG92021 (5 ng of p24 per well). The representative results from one of two similar experiments are shown in Table 4 and confirm the specificity of AMD3100 for CXCR4. Infection of U87.CD4.4444 cells by X4 and R5X4 viruses was fully inhibited in the presence of AMD3100 at this concentration. No effect of the inhibitor was detected for any virus with U87.CD4.5555 (Table 4 and data not shown), and the inability of SF162V3 reporter virus to infect the other cell lines remained unaltered. Unexpectedly, AMD3100 completely inhibited infection of every chimera-expressing cell line by all X4 and R5X4 viruses tested. Syncytium formation was similarly blocked in the presence of AMD3100 for all cell lines in which HIV-mediated cell fusion was observed in the absence of drug (data not shown).

TABLE 4.

Percent inhibition of infection of CCR5/CXCR4 chimera-expressing cells by AMD3100

| Chimera | Luciferase reporter virus

|

Primary isolate

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HXB2 | 89.6 | HT92599 | UG92021 | |

| 5555 | NIa | 0 | NI | NI |

| 4444 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 4555 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 5455 | 100 | 100 | 100 | NI |

| 5545 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 5554 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 78 |

| 5444 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 4544 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 87 |

| 4454 | 100 | 100 | NI | NI |

| 4445 | NI | 100 | NI | NI |

| 5544 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 5454 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 5445 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 4554 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 4545 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 4455 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| pBABE | NI | NI | NI | NI |

NI, no infection detected.

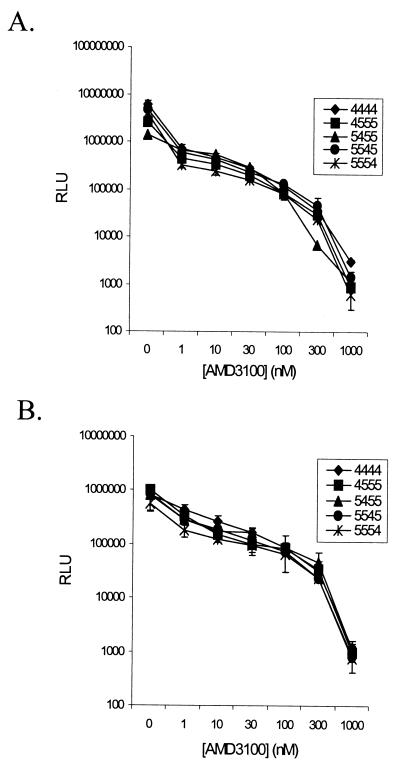

To determine whether there were differences in the sensitivities of chimeric coreceptors to the inhibitory action of AMD3100, infections were performed in the presence of increasing concentrations of the drug. Results from one of two representative experiments in which U87.CD4 expressing 4444, 4555, 5455, 5545, or 5554 were infected with the HXB2 and 89.6 reporter viruses (10 ng of p24 per well) are shown in Fig. 4 panels A and B, respectively. The inhibitory effect of AMD3100 was essentially the same for all cells tested, with 50% inhibition of infection occurring at or below 1 nM AMD3100 for 4444 and the chimeric coreceptors.

FIG. 4.

Dose-dependent inhibition of HIV infection by AMD3100. U87.CD4 cells expressing 4444 or the indicated chimeras were pretreated with increasing concentrations of AMD3100 prior to infection with HXB2 (A) or 89.6 (B) reporter viruses. Results of the luciferase assay performed 48 h p.i. are given as the average relative light units (RLU) of cell lysates from duplicate wells ± standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

Methodological issues in studies of coreceptor domains.

To investigate the structural features of the HIV-1 coreceptor-gp120 interaction, we constructed a set of CCR5/CXCR4 chimeras and generated stable cell lines normalized for chimeric coreceptor and CD4 levels. Based on the assumption that the major determinants of HIV coreceptor specificity lie on the extracellular face of the membrane and given that these regions exhibit the greatest sequence diversity between chemokine receptors, our chimeras express all combinations of the four extracellular domains of CCR5 and CXCR4. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that transmembrane or intracellular sequences contribute to chimeric coreceptor activity. Our study is novel in the use of chimeras of CCR5 and CXCR4, and this has allowed us to define, for the first time, distinct patterns of usage of each coreceptor domain. We would like to highlight particularly novel findings with regards to CXCR4 function.

The U87.CD4 cell line was chosen for expression of chimeric coreceptors because there was no endogenous expression of CCR5 or CXCR4 (data not shown). Moreover, endogenous CXCR4 or CCR5 was not induced by expression of the pBABE vector (Tables 1 to 3, vector control results; data not shown) or chimeric coreceptors. The latter conclusion is supported by the finding that none of the chimeric coreceptor-expressing cell lines mimic the spectrum of fusion and infection activity with different viral strains that is seen with CCR5 or CXCR4-expressing U87.CD4 (Tables 1 to 3).

Each chimera exhibited activity with one or more strains of HIV in assays of HIV-mediated cell fusion and infection, which allowed us to critically evaluate the function of the entire set of proteins. Direct measurements of gp120 binding to coreceptors were not performed since previous work has clearly demonstrated that this parameter does not accurately predict coreceptor function (2). Our data confirm and extend the findings of other studies which have demonstrated a complex and strain-dependent binding site for HIV within the coreceptor structure; envelope glycoproteins from R5, R5X4, and X4 viruses each displayed activity with a unique subset of chimeras. General trends based on coreceptor usage phenotypes were evident, however. For example, R5 HIV strains were highly restricted in coreceptor usage, with activity detected in 3 of 14 chimeras in only one of three functional assays. In contrast, X4 strains were extraordinarily flexible in their abilities to utilize these chimeras, and the presentation of any single CXCR4 domain within the CCR5 backbone was sufficient for fusion and infection mediated by multiple X4 primary isolates and the lab-adapted HXB2 strain.

Patterns of CXCR4 domain use.

While other groups have studied the behavior of CXCR4 domains in chimeric coreceptors, our study is the first to demonstrate the ability of each extracellular domain to support X4 fusion and infection. Additionally, our data indicate that although X4 viruses apparently utilize CXCR4 in different ways, there are common, and perhaps a finite number of usage patterns. The most permissive viral strains, which included HXB2, HT92599, and UG93053, infected cells expressing chimeras containing any one of the four CXCR4 domains within the context of CCR5 (Tables 2 and 3). Each was sensitive to changes in the CXCR4 molecule through substitution of the CCR5 domain(s) expressing ECL2 and/or ECL3 sequences but tolerated the exchange of the CXCR4 N terminus and ECL1 for CCR5 domains. A second group of X4 viruses, UG92021 and UG92029, exhibited a similar chimera usage pattern but were unable to utilize 5455, which expresses ECL1 of CXCR4 within CCR5 (Table 3). The HXB2 strain was also inactive with U87.CD4.5455 in the cell fusion assay (Table 1). A third grouping of X4 viruses includes those isolates that were the most sensitive to changes in coreceptor sequence, CMU08 and UG93059 (Table 3). These viruses were able to utilize ECL2 or ECL3 and sometimes the N terminus of CXCR4 for infection, and they exhibited the same restrictions to coreceptor usage as those described above but were also unable to utilize other chimeras. It would be of interest to determine if these distinct patterns of CXCR4 usage relate to virus evolution during disease progression.

Although all four extracellular domains of CXCR4 expressed individually in the CCR5 backbone are sufficient for virus entry, our findings indicate critical roles for the ECL2 and ECL3 domains. By focusing on the chimeras expressing single domains of CCR5 or CXCR4 with the remainder of the partner molecule, we can see that all the X4 viruses can use the chimeras with domains expressing ECL2 or ECL3 of CXCR4 alone. However, all X4 viruses are sensitive to the replacement of at least one of these domains in CXCR4 by CCR5 sequences (Tables 2 and 3). The information contained within one or both of these domains is therefore essential to all X4 viruses tested here, regardless of envelope subtype (see Materials and Methods). The presence of other domains, such as the N terminus or ECL1, may be sufficient to allow usage of CCR5 by some X4 viruses, but are not always critical to the interaction with CXCR4, as they can be replaced in the CXCR4 molecule by CCR5 sequences without effect. To explain these apparently paradoxical findings, we imagine the coreceptor binding site as a three-dimensional shape in which all viruses make one or more critical contacts, while a subset of virus strains require additional interactions for productive utilization. Whether the interaction of the X4 envelope with our chimeras requires the presence of specific CXCR4 sequences, the absence of inhibitory CCR5 sequences, or both is not clear. It is possible that the activity of each chimera is uniquely dependent on the characteristics of each swapped domain. Differences in the sequence, length, glycosylation state, or charge distribution of the substituted regions of CXCR4 and CCR5 may all require distinct compensatory contributions from the remainder of the molecule to form a functional HIV coreceptor. Importantly, our study provides the first clear demonstration that the CCR5 molecule contains enough structural homology with CXCR4 to produce a CXCR4-like gp120 interaction site.

CXCR4 inhibition.

The universal inhibition of X4 infection of our cell lines by AMD3100 shows unequivocally that a common, CXCR4-like structure is presented in each of the CCR5/CXCR4 chimeras. Inhibition of R5X4 viruses further demonstrates that these strains utilize the chimeras similar to CXCR4. Lu et al. (36) proposed that the evolution of the R5X4 phenotype in an R5 viral strain results from an acquired ability to utilize ECL1 and ECL2 of CXCR4 while retaining the capacity to interact with the N terminus of CCR5. However, the infection of U87.CD4.5554 by the 89.6 strain was also sensitive to AMD3100 inhibition (Fig. 4 and Table 4). Our data indicate that contacts made by AMD3100 with specific residues in ECL2 and TM domain 4 of CXCR4 (25, 33) either are mimicked in the presence of the CCR5 ECL2 or are not important to the antiviral action of the drug. Because CCR5 does not itself interact with this bicyclam (13), we favor the latter explanation. However, we cannot at this time provide an alternative rationalization for the interaction of AMD3100 with the CCR5/CXCR4 chimeras. Comparison of the overall charge presented at the extracellular face of the chimeras in Fig. 1 rules out the basic nature of AMD3100 as an underlying mechanism mediating the inhibition of infection. Therefore, some other intrinsic feature of the structure of AMD3100 must form the basis for its antagonistic effect on coreceptor function. We are currently investigating the activities of other coreceptor inhibitors against the CCR5/CXCR4 chimeras.

Requirements for CCR5 domain activity.

Our study also demonstrates an important role for the CCR5 ECL2 domain expressed in the CXCR4 backbone. SF162, an R5 primary isolate, was able to infect U87.CD4 expressing 4454, 4455, or 4555, suggesting that the ECL2 of CCR5 is important for its activity with HIV gp120. Unexpectedly, no activity was seen with any of the chimeras expressing the N-terminal domain of CCR5. Several studies have demonstrated the importance of the extracellular N terminus to CCR5 coreceptor function (4, 16, 18, 21–23, 27, 32, 35, 41, 47). However, it has also been shown that ECL2 participates in CCR5 coreceptor function based on reports of studies using CCR5-specific MAbs (29, 35, 50). Furthermore, Chabot et al. (8–10) have demonstrated that the molecular elements promoting activity with R5 viral envelopes are contained within the CXCR4 sequence and that specific point mutations in ECL2 of CXCR4 can reveal cryptic CCR5 activity. Therefore, it is not surprising that ECL2 of CCR5 expressed in the context of CXCR4 is active with an R5 envelope. However, we were able to detect activity only with the primary isolate of SF162, which expresses the entire SF162 envelope. When the SF162 V3 loop was expressed as a chimeric envelope, activity with the chimeric coreceptors was attenuated. While there are too many differences between the primary isolate and the luciferase reporter virus to draw conclusions about the function of the envelope glycoprotein, a potential explanation for this observation is that regions of gp120 outside the V3 loop contribute to the interaction with ECL2 of CCR5. However, we were unable to demonstrate fusion between cells expressing chimeric coreceptors and the full-length SF162 envelope glycoprotein. Efforts are under way to determine which elements of SF162 gp120 and CCR5 are involved in this interaction and whether they are sensitive to the actions of coreceptor antagonists.

Are these findings of coreceptor domain activity due to quantitative or qualitative differences in their function? Establishing consistent expression levels for all chimeric coreceptors was essential to the assessment of their activity in HIV fusion and infection assays. Differences in expression levels may explain the lack of activity of chimera 4555 observed by other researchers (27, 36). Most of our chimeric constructs functioned poorly or not at all when expressed by transient transfection, whereas selection of cell populations with the highest coreceptor levels allowed us to demonstrate a consistent level of chimeric coreceptor activity commensurate with that of the parental coreceptors. However, we were able to detect consistent activity of 5555 and 4444 in transiently transfected cells, which suggests that the parental coreceptors operate at a critical concentration lower than that of the chimeras. This observation supports the idea that for some HIV-1 coreceptors a threshold level of expression must be achieved for HIV-induced membrane fusion to occur efficiently (14). This phenomenon may reflect differences in the affinity of the coreceptors for gp120, in the ability of the coreceptors to associate with CD4 or themselves, or in their localization to specialized areas of the plasma membrane. We are now using the chimeric coreceptor cell lines to define potential CD4 interaction domains and to study the targeting of CCR5 and CXCR4 to specialized plasma membrane microdomains.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Chris Broder for the generous gift of recombinant vaccinia viruses and helpful correspondence, Michael Belshan for critical reading of the manuscript, Nancy Vander Heyden for preparation of human PBLs and virus stocks, and John Harding for excellent technical support.

This work was supported by an NRS grant, additional PHS grants, and a grant from AMFAR.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alkhatib G, Ahuja S S, Light D, Mummidi S, Berger E A, Ahuja S K. CC chemokine receptor 5-mediated signaling and HIV-1 co-receptor activity share common structural determinants. Critical residues in the third extracellular loop support HIV-1 fusion. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19771–19776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.32.19771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baik S S, Doms R W, Doranz B J. HIV and SIV gp120 binding does not predict coreceptor function. Virology. 1999;259:267–273. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger E A, Murphy P M, Farber J M. Chemokine receptors as HIV-1 coreceptors: roles in viral entry, tropism, and disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:657–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanpain C, Doranz B J, Vakili J, Rucker J, Govaerts C, Baik S S, Lorthioir O, Migeotte I, Libert F, Baleux F, Vassart G, Doms R W, Parmentier M. Multiple charged and aromatic residues in CCR5 amino-terminal domain are involved in high affinity binding of both chemokines and HIV-1 Env protein. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34719–34727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brelot A, Heveker N, Adema K, Hosie M J, Willett B, Alizon M. Effect of mutations in the second extracellular loop of CXCR4 on its utilization by human and feline immunodeficiency viruses. J Virol. 1999;73:2576–2586. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2576-2586.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brelot A, Heveker N, Montes M, Alizon M. Identification of residues of CXCR4 critical for human immunodeficiency virus coreceptor and chemokine receptor activities. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23736–23744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000776200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brelot A, Heveker N, Pleskoff O, Sol N, Alizon M. Role of the first and third extracellular domains of CXCR-4 in human immunodeficiency virus coreceptor activity. J Virol. 1997;71:4744–4751. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4744-4751.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chabot D J, Broder C C. Substitutions in a homologous region of extracellular loop 2 of CXCR4 and CCR5 alter coreceptor activities for HIV-1 membrane fusion and virus entry. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23774–23782. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003438200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chabot D J, Chen H, Dimitrov D S, Broder C C. N-linked glycosylation of CXCR4 masks coreceptor function for CCR5-dependent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates. J Virol. 2000;74:4404–4413. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.9.4404-4413.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chabot D J, Zhang P F, Quinnan G V, Broder C C. Mutagenesis of CXCR4 identifies important domains for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 X4 isolate envelope-mediated membrane fusion and virus entry and reveals cryptic coreceptor activity for R5 isolates. J Virol. 1999;73:6598–6609. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6598-6609.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen B K, Saksela K, Andino R, Baltimore D. Distinct modes of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proviral latency revealed by superinfection of nonproductively infected cell lines with recombinant luciferase-encoding viruses. J Virol. 1994;68:654–660. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.654-660.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connor R I, Sheridan K E, Ceradini D, Choe S, Landau N R. Change in coreceptor use correlates with disease progression in HIV-1–infected individuals. J Exp Med. 1997;185:621–628. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Clercq E. Inhibition of HIV infection by bicyclams, highly potent and specific CXCR4 antagonists. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57:833–839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doms R W. Beyond receptor expression: the influence of receptor conformation, density, and affinity in HIV-1 infection. Virology. 2000;276:229–237. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doms R W, Moore J P. HIV-1 membrane fusion: targets of opportunity. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:F9–F14. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.2.f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doranz B J, Lu Z H, Rucker J, Zhang T Y, Sharron M, Cen Y H, Wang Z X, Guo H H, Du J G, Accavitti M A, Doms R W, Peiper S C. Two distinct CCR5 domains can mediate coreceptor usage by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1997;71:6305–6314. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6305-6314.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doranz B J, Orsini M J, Turner J D, Hoffman T L, Berson J F, Hoxie J A, Peiper S C, Brass L F, Doms R W. Identification of CXCR4 domains that support coreceptor and chemokine receptor functions. J Virol. 1999;73:2752–2761. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2752-2761.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dragic T, Trkola A, Lin S W, Nagashima K A, Kajumo F, Zhao L, Olson W C, Wu L, Mackay C R, Allaway G P, Sakmar T P, Moore J P, Maddon P J. Amino-terminal substitutions in the CCR5 coreceptor impair gp120 binding and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry. J Virol. 1998;72:279–285. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.279-285.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Este J A, Cabrera C, Blanco J, Gutierrez A, Bridger G, Henson G, Clotet B, Schols D, De Clercq E. Shift of clinical human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates from X4 to R5 and prevention of emergence of the syncytium-inducing phenotype by blockade of CXCR4. J Virol. 1999;73:5577–5585. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5577-5585.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farzan M, Choe H, Martin K A, Sun Y, Sidelko M, Mackay C R, Gerard N P, Sodroski J, Gerard C. HIV-1 entry and macrophage inflammatory protein-1 beta-mediated signaling are independent functions of the chemokine receptor CCR5. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6854–6857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.6854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farzan M, Choe H, Vaca L, Martin K, Sun Y, Desjardins E, Ruffing N, Wu L, Wyatt R, Gerard N, Gerard C, Sodroski J. A tyrosine-rich region in the N terminus of CCR5 is important for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry and mediates an association between gp120 and CCR5. J Virol. 1998;72:1160–1164. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1160-1164.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farzan M, Mirzabekov T, Kolchinsky P, Wyatt R, Cayabyab M, Gerard N P, Gerard C, Sodroski J, Choe H. Tyrosine sulfation of the amino terminus of CCR5 facilitates HIV-1 entry. Cell. 1999;96:667–676. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80577-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farzan M, Vasilieva N, Schnitzler C E, Chung S, Robinson J, Gerard N P, Gerard C, Choe H, Sodroski J. A tyrosine-sulfated peptide based on the N terminus of CCR5 interacts with a CD4-enhanced epitope of the HIV-1 gp120 envelope glycoprotein and inhibits HIV-1 entry. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33516–33521. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007228200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng Y, Broder C C, Kennedy P E, Berger E A. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 1996;272:872–877. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerlach L O, Skerlj R T, Bridger G J, Schwartz T W. Molecular interactions of cyclam and bicyclam non-peptide antagonists with the CXCR4 chemokine receptor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:14153–14160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gosling J, Monteclaro F S, Atchison R E, Arai H, Tsou C L, Goldsmith M A, Charo I F. Molecular uncoupling of C-C chemokine receptor 5-induced chemotaxis and signal transduction from HIV-1 coreceptor activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5061–5066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hill C M, Kwon D, Jones M, Davis C B, Marmon S, Daugherty B L, DeMartino J A, Springer M S, Unutmaz D, Littman D R. The amino terminus of human CCR5 is required for its function as a receptor for diverse human and simian immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoproteins. Virology. 1998;248:357–371. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffman T L, Canziani G, Jia L, Rucker J, Doms R W. A biosensor assay for studying ligand-membrane receptor interactions: binding of antibodies and HIV-1 Env to chemokine receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:11215–11220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190274097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hung C S, Pontow S, Ratner L. Relationship between productive HIV-1 infection of macrophages and CCR5 utilization. Virology. 1999;264:278–288. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hung C S, Vander Heyden N, Ratner L. Analysis of the critical domain in the V3 loop of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 involved in CCR5 utilization. J Virol. 1999;73:8216–8226. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8216-8226.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kajumo F, Thompson D A, Guo Y, Dragic T. Entry of R5.X4 and X4 human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strains is mediated by negatively charged and tyrosine residues in the amino-terminal domain and the second extracellular loop of CXCR4. Virology. 2000;271:240–247. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuhmann S E, Platt E J, Kozak S L, Kabat D. Polymorphisms in the CCR5 genes of African green monkeys and mice implicate specific amino acids in infections by simian and human immunodeficiency viruses. J Virol. 1997;71:8642–8656. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8642-8656.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Labrosse B, Brelot A, Heveker N, Sol N, Schols D, De Clercq E, Alizon M. Determinants for sensitivity of human immunodeficiency virus coreceptor CXCR4 to the bicyclam AMD3100. J Virol. 1998;72:6381–6388. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6381-6388.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lapham C K, Ouyang J, Chandrasekhar B, Nguyen N Y, Dimitrov D S, Golding H. Evidence for cell-surface association between fusin and the CD4-gp120 complex in human cell lines. Science. 1996;274:602–605. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee B, Sharron M, Blanpain C, Doranz B J, Vakili J, Setoh P, Berg E, Liu G, Guy H R, Durell S R, Parmentier M, Chang C N, Price K, Tsang M, Doms R W. Epitope mapping of CCR5 reveals multiple conformational states and distinct but overlapping structures involved in chemokine and coreceptor function. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9617–9626. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu Z, Berson J F, Chen Y, Turner J D, Zhang T, Sharron M, Jenks M H, Wang Z, Kim J, Rucker J, Hoxie J A, Peiper S C, Doms R W. Evolution of HIV-1 coreceptor usage through interactions with distinct CCR5 and CXCR4 domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6426–6431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miedema F, Meyaard L, Koot M, Klein M R, Roos M T, Groenink M, Fouchier R A, Van't Wout A B, Tersmette M, Schellekens P T, et al. Changing virus-host interactions in the course of HIV-1 infection. Immunol Rev. 1994;140:35–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1994.tb00864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mosier D E, Picchio G R, Gulizia R J, Sabbe R, Poignard P, Picard L, Offord R E, Thompson D A, Wilken J. Highly potent RANTES analogues either prevent CCR5-using human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in vivo or rapidly select for CXCR4-using variants. J Virol. 1999;73:3544–3550. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3544-3550.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nussbaum O, Broder C C, Berger E A. Fusogenic mechanisms of enveloped-virus glycoproteins analyzed by a novel recombinant vaccinia virus-based assay quantitating cell fusion-dependent reporter gene activation. J Virol. 1994;68:5411–5422. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5411-5422.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rabut G E, Konner J A, Kajumo F, Moore J P, Dragic T. Alanine substitutions of polar and nonpolar residues in the amino-terminal domain of CCR5 differently impair entry of macrophage- and dualtropic isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1998;72:3464–3468. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.3464-3468.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rucker J, Samson M, Doranz B J, Libert F, Berson J F, Yi Y, Smyth R J, Collman R G, Broder C C, Vassart G, Doms R W, Parmentier M. Regions in beta-chemokine receptors CCR5 and CCR2b that determine HIV-1 cofactor specificity. Cell. 1996;87:437–446. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81364-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scarlatti G, Tresoldi E, Bjorndal A, Fredriksson R, Colognesi C, Deng H K, Malnati M S, Plebani A, Siccardi A G, Littman D R, Fenyo E M, Lusso P. In vivo evolution of HIV-1 co-receptor usage and sensitivity to chemokine-mediated suppression. Nat Med. 1997;3:1259–1265. doi: 10.1038/nm1197-1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schols D, Este J A, Cabrera C, De Clercq E. T-cell-line-tropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 that is made resistant to stromal cell-derived factor 1 alpha contains mutations in the envelope gp120 but does not show a switch in coreceptor use. J Virol. 1998;72:4032–4037. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4032-4037.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schramm B, Penn M L, Speck R F, Chan S Y, De Clercq E, Schols D, Connor R I, Goldsmith M A. Viral entry through CXCR4 is a pathogenic factor and therapeutic target in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 disease. J Virol. 2000;74:184–192. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.184-192.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trejo S R, Ratner L. The HTLV receptor is a widely expressed protein. Virology. 2000;268:41–48. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ugolini S, Moulard M, Mondor I, Barois N, Demandolx D, Hoxie J, Brelot A, Alizon M, Davoust J, Sattentau Q J. HIV-1 gp120 induces an association between CD4 and the chemokine receptor CXCR4. J Immunol. 1997;159:3000–3008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Z, Lee B, Murray J L, Bonneau F, Sun Y, Schweickart V, Zhang T, Peiper S C. CCR5 HIV-1 coreceptor activity. Role of cooperativity between residues in N-terminal extracellular and intracellular domains. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28413–28419. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Z X, Berson J F, Zhang T Y, Cen Y H, Sun Y, Sharron M, Lu Z H, Peiper S C. CXCR4 sequences involved in coreceptor determination of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 tropism. Unmasking of activity with M-tropic Env glycoproteins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15007–15015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.15007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Westervelt P, Gendelman H E, Ratner L. Identification of a determinant within the human immunodeficiency virus 1 surface envelope glycoprotein critical for productive infection of primary monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3097–3101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu L, LaRosa G, Kassam N, Gordon C J, Heath H, Ruffing N, Chen H, Humblias J, Samson M, Parmentier M, Moore J P, Mackay C R. Interaction of chemokine receptor CCR5 with its ligands: multiple domains for HIV-1 gp120 binding and a single domain for chemokine binding. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1373–1381. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xiao X, Wu L, Stantchev T S, Feng Y R, Ugolini S, Chen H, Shen Z, Riley J L, Broder C C, Sattentau Q J, Dimitrov D S. Constitutive cell surface association between CD4 and CCR5. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7496–7501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]