Significance

Understanding the mechanism of the ferroptosis processes is crucial as it can provide insights into pathogenesis. However, during ferroptosis, the dynamic mechanism involving membrane tension and morphology of the plasma membrane and the nuclear envelope remains unclear. To address this important problem, we present a robust fluorescence lifetime probe that can simultaneously target the plasma membrane and nuclear envelope with high mechanosensitivity. Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy reveals a dynamic mechanism of ferroptosis. During ferroptosis the membrane tension of the plasma membrane and nuclear envelope decreases, while during the advanced stage of ferroptosis the nuclear envelope exhibits budding, and membrane lesions are repaired in the low-tension regions by exocytosis.

Keywords: fluorescence lifetime probes, fluorescence lifetime imaging, mechanism of ferroptosis, membrane tension, nuclear envelope budding

Abstract

Deciphering the dynamic mechanism of ferroptosis can provide insights into pathogenesis, which is valuable for disease diagnosis and treatment. However, due to the lack of suitable time-resolved mechanosensitive tools, researchers have been unable to determine the membrane tension and morphology of the plasma membrane and the nuclear envelope during ferroptosis. With this research, we propose a rational strategy to develop robust mechanosensitive fluorescence lifetime probes which can facilitate simultaneous fluorescence lifetime imaging of the plasma membrane and nuclear envelope. Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy using the unique mechanosensitive probes reveal a dynamic mechanism for ferroptosis: The membrane tension of both the plasma membrane and the nuclear envelope decreases during ferroptosis, and the nuclear envelope exhibits budding during the advanced stage of ferroptosis. Significantly, the membrane tension of the plasma membrane is always larger than that of the nuclear envelope, and the membrane tension of the nuclear envelope is slightly larger than that of the nuclear membrane bubble. Meanwhile, the membrane lesions are repaired in the low-tension regions through exocytosis.

Several types of cell death, including autophagy, apoptosis, pyroptosis, necroptosis, and ferroptosis, have been reported (1–5). Ferroptosis is a unique type of non-apoptotic-regulated cell death, resulting from membrane damage mediated by massive lipid peroxidation (6, 7). Research over the past several years has revealed the key elements and functional consequences of ferroptosis, which have been found to play a key role in determining clinical outcomes of cancer treatments (8, 9). However, ferroptosis is a complex process, consisting of a series of events, requiring the involvement and regulation of many proteins on different subcellular organelles at different levels (10, 11). Therefore, it is important to decipher the mechanism of ferroptosis processes since it can provide insights into pathogenesis, which is valuable for biology and medical studies (12, 13). Functioning as vital material transporters, the plasma membrane and the nuclear envelope, linked by the endoplasmic reticulum, are involved in regulating the processes of ferroptosis (14, 15). Programmed cell death–induced changes in the nuclear envelope are important events in nuclear disruption (16, 17). Given that the nuclear envelope could be affected and influenced by the process of ferroptosis, understanding the biophysical hallmarks of living cells during the process of ferroptosis is an urgent requisite. The plasma membrane is the most critical interface that mediates the mechanobiological response of cells to external mechanical stimuli, while the nuclear envelope is a vital interface that responds to internal mechanical stress (18–20). During the process of cellular ferroptosis, changes in the membrane tension of the plasma membrane and nuclear envelope affect the ability of living cells to respond to mechanical stimuli, which may serve as an important factor in the subsequent induction of cell death. Therefore, combining the detection of membrane tension and morphology of the plasma membrane and the nuclear envelope could provide key mechanistic insights into ferroptosis.

Although investigations focusing on the membrane tension of plasma membranes in normal cells have progressed to some extent (21–23), the dynamic mechanism of membrane tension and morphology of both the plasma membrane and nuclear envelope during ferroptosis remain unknown to date. For example, will a change of the membrane tension and morphology of the nuclear envelope lead to nuclear envelope budding? Finally, at what stage of ferroptosis do these changes occur? These key problems are largely unknown. Based on the plasma membrane and the nuclear envelope, we outline the scientific questions concerning the ferroptosis mechanism in Scheme 1A. To address these important issues, we constructed robust fluorescence lifetime imaging probes, where the signals vary with changes of the membrane tension in the plasma membranes and the nuclear envelope. Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) is a time-resolved technique that enables quantitative analysis by mapping the spatial distribution of nanosecond excited-state lifetimes using microscopic images (24, 25). Compared with fluorescence intensity–based imaging techniques, FLIM imaging is based on the fluorescence decay rate rather than absolute intensity and as such avoids signal variations due to fluorophore diffusion or quenching, laser intensity, and detection gain. The superior quantitative detection technology of FLIM imaging makes it possible to detect small changes in membrane ordering by measuring fluorescence lifetime values. As such, our effort was directed toward the design and synthesis of ultrasensitive molecular probes with outstanding membrane targeting and membrane tension sensitivity suitable for FLIM.

Scheme 1.

Scientific question concerning the mechanism of ferroptosis and design strategy for fluorescence lifetime probes. (A) Schematic illustration of the scientific question concerning the mechanism of ferroptosis based on the membrane tension and morphology of both plasma membrane and nuclear envelope. (B) Probe design strategy based on part “a” (B1) concerns hydrophilic and lipophilic regulation, regulating the ability of the probe to target the membrane (B2). The part “b” (B3) is about charge transfer regulation, which affects the sensitivity of the molecular rotor. (B4) The sensing modes of membrane tension by the probes based on the fluorescence lifetime. (C) Theoretical calculations and spectral properties of DF1. (C1) TD-DFT calculated the energy profile of the S0 and S1 states of DF1 in the planar geometry state and twisted TICT state. The fluorescence emission spectra (C2) and the fluorescence lifetime decay (C3) of DF1 (10 μM) in the different volume ratios of glycerol and methanol (0, 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100% Gly in methanol).

In this research, using a hybrid design strategy, we engineered a series of fluorescence lifetime probes named DFs (DF1, DF2, DF3, and DF4) with varied hydrophilic–lipophilic and electronic donor–acceptor properties. Among them, considering the capability of targeting the membrane as well as delivering an ultra-mechanosensitive response, we illustrate that probe DF1 could be used to detect the membrane tension and morphology of the plasma membrane and the nuclear envelope during ferroptosis using FLIM imaging. Single-phase/mixed-phase giant uniflagellar vesicles (GUVs) and cell osmotic shock FLIM imaging experiments reveal the exquisite mechanosensitive properties of DF1, verifying the uniqueness of the theoretically and experimentally selected DF1. Using the mechanosensitive probe DF1, we investigated the dynamic mechanism of ferroptosis based on membrane tension and morphology of the plasma membrane and nuclear envelope.

Results

Design and Synthesis of DFs.

When evaluating the membrane tension and morphology of the plasma membrane and nuclear envelope using FLIM imaging, fluorescence lifetime probes must possess 1) accurate targeting of the plasma membrane and nuclear envelope and exhibit controlled cellular internalization, and 2) fluorescence lifetime mechanosensitivity. In this work, we selected the π-conjugated systems composed of naphthalene and pyridine as the chemical platform to design the fluorescence lifetime probes for FLIM imaging. Furthermore, to optimize the probe’s ability to target the membranes, control cellular internalization, and respond sensitively to membrane tension, we decided to adopt a hybrid strategy.

On the one hand, the hydrophilic–lipophilic properties of DFs could be regulated by linking R1 and R2 with different hydrophilic or lipophilic groups, as shown in part “a” of Scheme 1, B1. Among them, the R1 groups contain hydrophilic ethylenediamine and lipophilic dimethylamine, and membrane targeting groups R2 include lipophilic C12 chains and hydrophilic (3-propyl)trimethylammonium groups. With the inclusion of the membrane-targeting groups, we hypothesized that high lipophilicity would allow rapid cellular internalization of the probe with a short retention time in the membrane. While with high hydrophilicity, the probe will be repelled by the membrane and as such would not be inserted into the membrane. Thus, suitable amphiphilicity of the probes needs to be considered for effective membrane targeting (Scheme 1, B2). Through the structural properties of the orthogonal combination of R1 and R2, we judged the order of hydrophilicity as follows: DF2>DF1>DF4>DF3. To determine the accurate hydrophilic–lipophilic properties of the DFs compounds, we measured the lipid–water partition coefficients of the probes (SI Appendix, Table S1). As predicted, DF2 with two hydrophilic groups displays the strongest hydrophilicity (LgD value of -0.9145). DF1 and DF4 have hydrophilic and lipophilic groups; however, DF1 is more hydrophilic with an LgD value of -0.6952, while DF4 is more lipophilic with an LgD value of 0.4185. DF3 has the strongest lipophilicity with an LgD value of 0.9635 since it contains two lipophilic (hydrophobic) groups. By comparing the hydrophilic–lipophilic properties of the DFs, we postulated that DF1 and DF4 with hydrophilic and lipophilic groups should exhibit better membrane targeting properties.

On the other hand, the twisted intramolecular charge transfer (TICT) character of the DFs could be regulated by linking R1 and R2 with different electron donor or electron acceptor groups (26), as shown in part “b” of Scheme 1, B3. Among them, R1 contains the electron donor ethylenediamine and dimethylamine groups. While the positive N ion on the pyridine group exhibits a strong electron-withdrawing effect, the R2 includes the electron donating C12 chain or electron acceptor (3-propyl)trimethylammonium group which could weaken or enhance the electron-withdrawing effect of the positive N ion of the pyridine. To verify the electronic properties of the DFs, we carried out density functional theory (DFT) and time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) calculations at the B3LYP/6-31G (d, p) level of Gaussian 09 (27–29). The structures of the DFs were optimized using DFT calculations (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Lower energy gaps for DF1 and DF2 were determined which suggests that DF1 and DF2 have more pronounced electronic push–pull properties since the (3-propyl)trimethylammonium group enhances the electron-withdrawing nature. Then, we calculated the excited states of the DFs using TD-DFT (Scheme 1, C1 and SI Appendix, Table S2). In the optimized state of DF1, the electronic transitions from S0 to S1 for the planar structure have a large amplitude of 1.2303. When the double bond between the naphthalene and pyridine and the single bond of diphenylamine rotates, the S1 energy is lowered, the electrons return to the ground state in a nonradiative manner, and the amplitude drops to almost zero in this state. Thus, when DF1 is aggregated in a loosely packed disordered phase under low membrane tension, the molecular rotors of DF1 are free to rotate and twist out of conjugation, resulting in lower fluorescence intensity and shorter fluorescence lifetimes. Conversely, if DF1 is aggregated in a tightly lipid-ordered membrane phase under high membrane tension, the rotation of molecular rotors will be restricted and can form a planar conjugated system, thereby increasing the fluorescence lifetime (Scheme 1, B4). Therefore, we envisioned that DF1, which exhibits favorable molecular bond rotation properties, might exhibit an ultra-mechanosensitive response to membrane tension.

Therefore, based on the above hybrid probe design strategy, we developed a series of probes DFs. The synthetic route for the DFs is given in SI Appendix, Scheme S1, and the characterization data for the DFs compounds using 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and high-resolution mass spectrometry is also provided. (SI Appendix, Figs. S2–S16).

Photophysical Properties of DFs.

We first examined the spectral properties of the DFs in solvents with various viscosity. The absorption maximum of the DFs varies between 450 and 480 nm in pure Gly/MeOH solutions (SI Appendix, Fig. S17). The emission peaks and fluorescence lifetime of the DFs were measured in different volume ratios of glycerol and methanol (0, 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100% Gly). We observed that the maximum emission peaks of DFs vary between 600 and 670 nm at 100% Gly (SI Appendix, Fig. S18). As the viscosity of the environment increased, the fluorescence intensities of the DFs increased, and the emission peaks were blue-shifted. Compared with DF2, DF3, and DF4, the fluorescence response of DF1 to a viscous solution was the most pronounced (Scheme 1, C2). The fluorescence lifetime(s) of the DFs increased as the viscosity of the environment increased (SI Appendix, Fig. S19). Among them, the fluorescence lifetime of DF1 changes most drastically and exhibits excellent linearity between the fluorescence lifetime and solution viscosity (Scheme 1, C3). The DF1 fluorescence lifetime(s) calculated based on the decay curves are 0.515, 0.649, 0.803, 0.940, 1.165, and 1.576 ns in 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100% Gly solution, respectively. These results highlight the ultrasensitivity of DF1 to viscous environments in the fluorescence lifetime. The experimental results are consistent with the theoretically calculated predictions above and reveal a link between the strong TICT effect of the acceptor–donor groups and the ultrasensitive response to changes in the viscosity of the environment.

The Membrane Tension of Both the Plasma Membrane and the Nuclear Envelope Decreases during Ferroptosis.

To assess the mechanosensitive ability of DFs, FLIM imaging was conducted on GUVs and cells undergoing osmotic shock. Our findings demonstrate that DF1 exhibits robust mechanosensitivity, making it suitable for investigating the altered mechanical properties in the membranes (SI Appendix, Figs. S20–S23). Then, the biocompatibility of the DFs was examined prior to the cell imaging experiments. Based on the CCK8 assay of the 4T1 cells, the DFs did not exhibit marked cytotoxicity with over 90% cell viability observed even at 50 μM concentrations after 24 h incubation (SI Appendix, Fig. S24). We then performed colocalization experiments using confocal laser scanning microscopy to verify the targeting specificity of DF1 to the plasma membrane. Commercially available plasma membrane dye DiD was costained with DF1 in 4T1 cells in the presence of 0 or 30 μM cisplatin for 12 h. In the absence of cisplatin, excellent overlap of the red fluorescence signal of DF1 and the purple fluorescence signal of DiD in the cells was observed (SI Appendix, Fig. S25, a3). The DF1 and DiD intensity profiles at the localized region ROI.01 of the plasma membrane exhibited very good overlap (SI Appendix, Fig. S25, a4 and a5). However, when the cells were incubated with 30 μM cisplatin, DF1 targeted both the plasma membrane and the nuclear envelope (SI Appendix, Fig. S25, b1). The DF1 and DiD intensity profiles at the localized region ROI.02 of the plasma membrane exhibited nice overlap (SI Appendix, Fig. S25, b4 and b5), indicating that some of the DF1 remained in the plasma membrane after being internalized into the cells.

Cisplatin has been shown to induce ferroptosis by targeting glutathione (GSH) (30, 31). Initially, fluorescence lifetime imaging was conducted using DFs to assess the imaging capabilities of each probe in cisplatin-treated cells. Accordingly, the cells were stimulated by various concentrations (0 to 50 μM) of cisplatin for 12 h to determine the concentration dependence of the cisplatin lethality. Since cisplatin is widely known as an inducer of apoptosis, we thus used a commercial apoptosis kit to judge the stage of the stimulated cells with different concentrations of cisplatin (32, 33). The cells were stimulated with 0 to 50 μM of cisplatin for 12 h and validated using a commercial Annexin V-FITC apoptosis kit (SI Appendix, Fig. S26). The cells induced with 10 or 30 μM cisplatin were in the apoptotic state, while with 50 μM cisplatin stimulation, they were in a state of necrosis. We conducted the confocal imaging and FLIM imaging of 4T1 cells incubated with 0 to 50 μM cisplatin for 12 h. The results indicate that the autofluorescence of the cells following drug stimulation is nearly absent, with fluorescence lifetime values being very small (0.050 to 0.056 ns), rendering them negligible (SI Appendix, Fig. S27). The cell imaging and mean fluorescence lifetime of DF1 are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S28. The nuclear envelope is delineated with a white dotted line on the bright field image of the 10, 30, and 50 μM cisplatin-incubated cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S28), which was consistent with the nuclear envelope illuminated by DF1 in the fluorescence lifetime imaging. DF1 was anchored to the plasma membrane of the nonstimulated cells. Significantly, in the absence of cisplatin even after incubation for 1 h, DF1 was still not internalized. The heterogeneity and flow processes of the plasma membrane were visualized by changes of fluorescence lifetime pseudocolor (Movie S1). By sharp contrast, when the cells were stimulated with 10 μM cisplatin, DF1 started to be cellularly internalized and targeted the nuclear envelope when ferroptosis was initiated. The fluorescence lifetime pseudocolor on the plasma membrane changed from red to yellow, while the nuclear envelope was green, suggesting that the cells may be in the early stage of cisplatin lethality. When the cells were stimulated with 30 μM cisplatin for 12 h, the fluorescence lifetime pseudocolor on the plasma membrane changed from yellow to green. Interestingly, bubbles began to appear in the nuclear envelope at this stage, which could be taken as a sign of advanced ferroptosis. When 4T1 cells were stimulated by 50 μM cisplatin for 12 h, the cells appeared necrotic with large gaps in the plasma membrane and rupture of the nucleus. For comparison, DF2-4 were also evaluated using FLIM imaging under similar conditions. DF2 did not exhibit any signals in the fluorescence lifetime imaging, suggesting that it does not target the plasma membrane and so does not undergo cellular internalization (SI Appendix, Fig. S29). This result is in good agreement with the fluorescence lifetime imaging of GUVs, as large hydrophilic molecules are difficult to anchor to the plasma membrane. By contrast, after the cells were stimulated by cisplatin, DF2 was internalized and targeted to the nucleus due to an increase of plasma membrane permeability. DF3 and DF4 were rapidly internalized in the nonstimulated cells due to their strong lipophilicity (SI Appendix, Figs. S30 and S31). With the progression of ferroptosis, the fluorescence lifetime of DF3 and DF4 did not change significantly. The fluorescence lifetime decay of the 4T1 cells stained with DF2, DF3, and DF4 is shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S32, respectively.

We then investigated dynamic changes of the membrane tension and morphology of the plasma membrane and nuclear envelope during ferroptosis. Erastin is known to inhibit the system Xc−mediated cystine transport, acting as a cell-permeable ferroptosis activator (6, 34). Thus, the cells were stimulated with 10 μM erastin for various times (0 to 90 min) and 0 to 4 μM erasrtin for 12 h to enable erastin-incubation cell ferroptosis progression. We then used a commercial lipid peroxidation probe C11-BODIPY581/591 to evaluate the stage of the stimulated cells treated with erastin. Consequently, when the cells were stimulated with 10 μM erastin for 30 min, lipid peroxidation was observed, which became more pronounced with increasing duration of time (SI Appendix, Fig. S33). Similarly, when the cells were stimulated with 1 μM erastin for 12 h, cell lipid peroxidation was observed, which became more evident with increasing erastin concentrations (SI Appendix, Fig. S34). FLIM imaging without DF1 reveals that the erastin-stimulated cells exhibit minimal autofluorescence, with autofluorescence lifetimes ranging from 0.050 ns to 0.098 ns, which are negligible (SI Appendix, Figs. S35 and S36). For the unstimulated cells, in the preferroptotic stage, DF1 only anchored to the plasma membrane and the pseudocolor of the plasma membrane was red (Fig. 1A, a). When the cells were stimulated by 10 μM erastin for 30 min, DF1 began to be internalized and targeted the nuclear envelope at the onset of ferroptosis (Fig. 1A, b). The pseudocolor of the plasma membrane changed from red to yellow, and the nuclear envelope was green. This means that when the cells undergo ferroptosis, the permeability increases accompanied by a decrease in the tension of the membrane, causing some of DF1 to enter the cells. The cells in this state may be undergoing early ferroptosis. For the cells stimulated by 10 μM erastin for 60 min, the degree of ferroptosis increased. The fluorescence lifetime pseudocolor of the plasma membrane changed from yellow to green (Fig. 1A, c). We considered the cells in this state to be at the intermediate ferroptosis stage. When the cells were stimulated by 10 μM erastin for 90 min, the pseudocolor of the plasma membrane changed to be turquoise and two nuclear envelope bubbles appeared in the nuclear envelope (Fig. 1A, d). This behavior of nuclear envelope budding could be a sign of late ferroptosis. As the stimulation time of erastin ranged from 0 to 90 min, the mean fluorescence lifetime of DF1 (Fig. 1B) exhibited a significant decreasing trend, from 3.234 to 2.229 ns, clearly indicating that the membrane tension of the system is decreased during the process of ferroptosis.

Fig. 1.

FLIM imaging of cells incubated with erastin and then stained with 10 μM DF1. (A) FLIM imaging of cells incubated with 10 μM erastin during 0 to 90 min and then stained with 10 μM. Among them, ROI 1 represents part of the plasma membrane region for 0 min erastin-stimulated cells; ROI 2 represents part of the plasma membrane region for 30 min erastin-stimulated cells; ROI 3 represents part of the nuclear envelope region for 30 min erastin-stimulated cells; ROI 4 represents part of the plasma membrane region for 60 min erastin-stimulated cells; ROI 5 represents part of the nuclear envelope region for 60 min erastin-stimulated cells; ROI 6 represents part of the plasma membrane region for 90 min erastin-stimulated cells; ROI 7 represents part of the nuclear envelope region for 90 min erastin-stimulated cells; ROI 8 represents part of the first nuclear envelope bubble region for 90 min erastin-stimulated cells; ROI 9 represents part of the second nuclear envelope bubbles region for 90 min erastin-stimulated cells. (B) Fluorescence lifetime decay of the DF1 FLIM imaging of (A). (C) Average fluorescence lifetime τi of DF1 in the zoomed region 1 to 9 of (A). (D) The proportion of the two double exponentials fitting components τ1 and τ2 of (A). (E) Schematic illustration of the changes in the fluorescence lifetime of DF1 and the membrane tension and morphology changes of the plasma membrane and nuclear envelope during the ferroptosis process. λEx = 480 nm; λEm = 550 to 750 nm. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) PM represents the plasma membrane, NE represents the nuclear envelope, and NEB represents the nuclear envelope budding.

To study the membrane tension and morphological changes of the plasma membrane and nuclear envelope at the single-cell level, the plasma membrane, nuclear envelope, and nuclear envelope bubbles of the individual cells at each stage were divided into ten locally demarcated regions (Fig. 1A, ROI1-ROI9). Then, fluorescence lifetime analysis of these regions was performed separately (Fig. 1C). The results indicate that with the evolution of ferroptosis, the fluorescence lifetime of DF1 in the plasma membrane (ROI1, 2, 4, 6) decreased, from 3.677 to 2.728 ns. The lifetime of DF1 on the nuclear envelope (ROI3, 5, 7) diminished from 2.297 to 2.177 ns, and the lifetimes of DF1 on the two nuclear envelope bubbles (ROI8, 9) were 2.166 and 2.090 ns, which are slightly smaller than that of the nuclear envelope. Meanwhile, to examine the distribution of the dual fluorescence lifetimes in the cells, we fitted two biexponential components to provide the lower lifetime decay exponent τ1 in pseudocolor green and the higher lifetime decay exponent τ2 in pseudocolor red (Fig. 1A τ1, τ2). It can be seen from the results that the lower fluorescence lifetime τ1 was distributed both in the plasma membrane and the nuclear envelop. By contrast, the higher fluorescence lifetime τ2 is only distributed in the plasma membrane. The proportion of τ1 was 37% for the nonstimulated cells. After the cells started ferroptosis, the proportion of τ1 increased to 49% and became stable, implying that the internalization of DF1 to the cells increased the proportion of τ1 with a lower fluorescence lifetime as the cells underwent ferroptosis (Fig. 1D). The results of the above ferroptosis experiments were taken together and illustrated in a schematic diagram (Fig. 1E). The red pseudocolor at the preferroptotic stage represents the plasma membrane with the largest fluorescence lifetime. When the cells were in the early stage of ferroptosis, DF1 was internalized and targeted the nuclear envelope. The fluorescence lifetime of DF1 on the plasma membrane was reduced, indicated by a yellow pseudocolor, and the fluorescence lifetime of DF1 in the nuclear envelope was lower than that of the plasma membrane, indicated by a green pseudocolor. The continuous lower tension of the plasma membrane and nuclear envelope suggests that the cells were at an intermediate ferroptotic stage. When the nuclear envelope began to generate bubbles, the cells are in the stage of the late ferroptosis. The fluorescence lifetime of DF1 in the bubble is lower than that of the nuclear envelope. For the cells stimulated with 0 to 4 μM erastin for 12 h to establish erastin concentration-dependent cell ferroptosis progression, the morphological changes and alterations in the membrane tension of both the plasma membrane and nuclear envelope resemble the findings of the erastin-time-dependent experiments (SI Appendix, Fig. S37).

Furthermore, to spatially visualize the membrane tension and morphology changes of the plasma membrane and nuclear envelope, 3D fluorescence lifetime imaging was performed for the cells stimulated with cisplatin at 0, 10, or 30 μM for 12 h, respectively (SI Appendix, Fig. S38). In the unstimulated cells, DF1 was shown to anchor with the plasma membrane. For cells in the early ferroptotic state (stimulated with 10 μM cisplatin), DF1 was internalized and anchored to both the plasma membrane and nuclear envelope simultaneously. We could visualize the peripheral convex surface of both the plasma membrane and the nuclear envelope. For cells in an advanced ferroptosis state (stimulated with 30 μM cisplatin), the 3D plasma membrane, nuclear envelope, and nuclear envelope bubble could be clearly observed. The 3D fluorescence lifetime imaging also suggests that the nuclear envelope budding may be through the outward expansion of the nuclear envelope pores. The cell 3D panorama for these cells is shown in Movies S2–S4, providing an opportunity to analyze the membrane tension and morphology changes of the plasma membrane and nuclear envelope from a spatiotemporal perspective.

The Nuclear Envelope Exhibits Budding during the Advanced Stages of Ferroptosis.

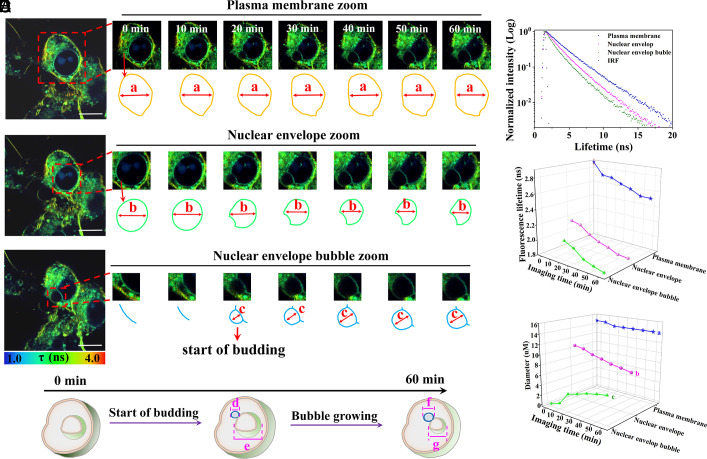

To observe the dynamics of nuclear envelope budding, we chose to scan advanced ferroptotic cells using time-lapse FLIM imaging. Toward this end, to explore the changes in the membrane tension and morphology of the plasma membrane, nuclear envelope, and nuclear envelope bubble during the nuclear envelope budding process at the advanced ferroptotic state, 4T1 cells were scanned by FLIM for 60 min after stimulation with 30 μM cisplatin for 12 h. With the progression of advanced ferroptosis, the budding process of the nuclear envelope was clearly observed in Movie S5. We then zoomed in on the plasma membrane, nuclear envelope, and nuclear envelope bubble of the cell from 0 to 60 min for detailed analysis (Fig. 2A). There is a slight change in the diameter of the plasma membrane when the scanning time was enhanced from 0 to 60 min, as shown in “a” in the model of the plasma membrane. The fluorescence lifetime pseudocolor of DF1 in the plasma membrane gradually changed from light yellow to green. Concurrently, the nuclear envelope gradually shrank, and the diameter decreased significantly, as shown in “b” in the model of the plasma membrane. Then at the 20th minute of FLIM scanning, the nuclear envelope started budding. With the enhancement of the scanning time to 60 min, the bubble gradually increased with stable growth in the later stages, as shown in “c” in the model of the plasma membrane. The fluorescence lifetime decay of the plasma membrane, nuclear envelope, and nuclear envelope bubble is shown in Fig. 2B. We can thus sum up the fluorescence lifetime of DF1 in the plasma membrane, nuclear envelope, and nuclear envelope bubble during 60 min FLIM imaging as shown in Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Table S3. The fluorescence lifetime of DF1 in the plasma membrane region (from 2.891 to 2.525 ns) displayed a negative correlation with the imaging time. Similarly, the fluorescence lifetime of DF1 in the nuclear envelope region exhibited a slight decrease over the imaging period from 2.147 to 1.851 ns, and then that of the nuclear envelope bubble region also continued to decrease, from 2.014 to 1.819 ns. The diameters of the plasma membrane, nuclear envelope, and nuclear envelope budding for 60 min FLIM imaging were also plotted as curves in Fig. 2D. The diameter of the plasma membrane changed slightly (from 14.86 to 14.18 μm). Concurrently, the diameter of the nuclear envelope progressively decreased from 10.62 to 7.68 μm, and that of the nuclear envelope bubble gradually increased to almost 5.21 μm at the 20th minute of FLIM imaging.

Fig. 2.

FLIM imaging of the dynamic mechanism of 4T1 cells stained with 10 μM DF1 after incubation with 30 μM of cisplatin for 12 h. (A) Time-lapse fluorescence lifetime imaging over 60 min, enlarged details of the plasma membrane, nuclear envelope, and nuclear envelope bubble of the cells at 0 to 60 min, respectively. (B) The fluorescence lifetime decay of the DF1 in FLIM imaging of (A). (C) Imaging time and fluorescence lifetime correlation curves of DF1 in the plasma membrane, nuclear envelope, and nuclear envelope bubble of (A). (D) Imaging time and diameter correlation curves with the diameter changes of the plasma membrane, nuclear envelope, and nuclear envelope bubble, corresponding to a, b, and c in (A). (E) Schematic illustration of the membrane tension and morphology changes of the plasma membrane and nuclear envelope during advanced ferroptosis based on the results of the time-lapse FLIM imaging. “d” and “f” represent the diameter of the nuclear envelope bubble, and “e” and “g” represent the diameter of the nuclear envelope. Among them, “d” < “f,” “e”> “g.” λEx = 480 nm; λEm = 550 to 750 nm. (Scale bar, 10 μm.)

Thus, we summarize the results of the dynamic experiments as a schematic illustration (Fig. 2E). In the process of time-lapse imaging at the advanced ferroptotic state, the pseudocolor of the plasma membrane changed from dark green to green, and the pseudocolor of the nuclear envelope changed from green to light green, indicating that the fluorescence lifetime of DF1 in the plasma membrane, nuclear envelope, and nuclear envelope bubble gradually decreased. During this process, the membrane tension of the plasma membrane and nuclear envelope gradually reduced. The morphology variations of the nuclear envelope indicated that the nuclear envelope gradually shrank when the budding began, while the morphology of the plasma membrane did not change significantly at this state. Among them, “d” and “f” represent the diameter of the nuclear envelope bubble, and “e” and “g” represent the diameter of the nuclear envelope. The diameter of the bubble gradually increased (“d” < “f”), while the nuclear envelope shrank and deformed (“e” > “g”).

The Membrane Lesions Are Repaired in the Low-Tension Regions through Exocytosis.

Membrane damage and repair is a dynamic process. To mimic simultaneous membrane damage and repair, we performed FLIM imaging of the cells simultaneously stimulated with both erastin and ferrostatin-1 utilizing DF1, as the plasma membrane may undergo a dynamic process of lesion and repair under the conditions of simultaneously inducing and inhibiting ferroptosis. The FLIM imaging experiments following the cell stimulation with ferrostatin-1 revealed negligible autofluorescence and autofluorescence lifetimes (ranging from 0.050 to 0.096 ns) (SI Appendix, Fig. S39 A and B). The fluorescence lifetime of DF1 in cells (3.234 ns) and DF1 in ferroptosis cells (2.477 ns) is significantly higher than that of the cellular autofluorescence (0.050 ns), even after treatment of the cells with cisplatin (0.056 ns), erastin (0.098 ns), or ferrostatin-1 (0.096 ns) (SI Appendix, Fig. S39C), suggesting that the short fluorescence lifetime of the cellular autofluorescence superimposed with DF1 does not account for the changes in the fluorescence lifetime attributed to ferroptosis. In addition, to further demonstrate that drugs (cisplatin, erastin, or ferrostatin-1) do not influence the fluorescence lifetime of DF1, we assessed the fluorescence lifetimes of 10 μM DF1, DF1 with cisplatin, DF1 with erastin, and DF1 with ferrostatin-1 in the glycerol (high viscosity), methanol (low viscosity) solutions, and GUVs (DOPC-DPPC-CL). The results revealed nearly overlapping fluorescence lifetime decay curves of DF1, DF1 with cisplatin, DF1 with erastin, and DF1 with ferrostatin-1 in both the glycerol and methanol solutions and GUVs (SI Appendix, Figs. S40 and S41), indicating that these drugs do not impact the fluorescence lifetime of DF1 independent of membrane tension.

At the single-cell level, we found a transition from homogeneity to heterogeneity in the plasma membrane of the poststimulated cell (Fig. 3A). The difference in the pseudocolor of region a-c (a is red, b is yellow, and c is green) shows that the membrane tension changed regionally. As shown in Fig. 3B, the mean DF1 fluorescence lifetime of the “Normal” region on the prestimulated cell is similar to that of region I on the poststimulated cell and higher than that of regions II and III (τNormal = 3.736 ns, τI = 3.731 ns, τII = 3.501 ns, τIII = 3.260 ns). In addition, many obvious agglomerations with green pseudocolor existed in different plasma membrane areas of the poststimulated cells. We thus zoomed in on the ROI1-4 area and circled the agglomerates in the area with red dotted lines ROI 1a- 4 g (Fig. 3A). Compared with the red pseudocolor of the plasma membrane, the abnormal agglomerates on the plasma membrane showed bright green pseudocolor, indicating that the membrane tension at the ROI area is much lower than that on the cell membrane. As shown in Fig. 3C, all the mean fluorescence lifetimes of DF1 for ROI 1a- 4 g are lower than 3.0 ns. (τ1a = 2.895 ns, τ1b = 2.921 ns, τ2c = 2.743 ns, τ2d = 2.632 ns, τ3e = 2.693 ns, τ3f = 2.599 ns, τ4g = 2.186 ns, τ4h = 2.706 ns). Subsequently, following incubation with 1 μM erastin for 6 h, the cells were washed with PBS. These cells were divided into two groups: one without the addition of ferrostatin-1 and the other with the addition of 5 μM ferrostatin-1, followed by 6 h incubation period. Finally, FLIM imaging was performed using DF1. When the cells were not incubated with ferrostatin-1, the plasma membrane slowly repaired damaged areas through the process of exocytosis (indicated by red arrows in image c of Fig. 3D). However, when the cells were stimulated with ferrostatin-1, the plasma membrane could globally and continuously repair to a state that was almost indistinguishable from that of the control group (image d of Fig. 3D). The mean fluorescence lifetime of DF1 in images a-d suggests that the membrane tension of the cells stimulated with ferrostatin-1 is increased to a level nearly comparable to that of the control cells (Fig. 3E). From Fig. 3F, the mean DF1 fluorescence lifetime of regions IV and V for the stimulated cell without ferrostatin-1 is lower than that of the “Normal” region for the prestimulated cell, while region VI for the stimulated cell with ferrostatin-1 is similar to that of the “Normal” region.

Fig. 3.

FLIM imaging of the cells incubated with erastin and ferrostatin-1 and then stained with 10 μM DF1. (A) FLIM imaging of prestimulated cells and poststimulated cells with 10 μM erastin and 10 μM ferrostatin-1 at 90 min and then stained with 10 μM DF1. (B) Fluorescence lifetime of the DF1 FLIM imaging in the regions Normal (Prestimulated) and I to III (Poststimulated) of (A). (C) Fluorescence lifetime of DF1 in the ROI zoomed region 1a-4 g of (A). (D) The cells were divided into two groups after incubation with 1 μM erastin for 6 h: one group without the addition of ferrostatin-1 and the other with the addition of 5 μM ferrostatin-1, followed by a 6-h incubation period. Subsequently, the cells were stained with 10 μM DF1 for FLIM imaging. (E) Fluorescence lifetime decay of DF1 in FLIM imaging a, b, c, and d of (A) and (D). (F) Fluorescence lifetime of the DF1 FLIM imaging in regions IV to VI of (D). λEx = 480 nm; λEm = 550 to 750 nm. (Scale bar, 10 μm.)

Therefore, using probe DF1, which evaluates membrane tension and permeability simultaneously, we have garnered insights into the dynamic interplay between the membrane tension and membrane permeability during the early stages of ferroptosis. One of the hallmarks of ferroptosis is unrestrained lipid peroxidation (35). As such for experiments using the commercial lipid peroxidation probe C11-BODIPY581/591, the cells exhibited lipid peroxidation in the early stages of ferroptosis (SI Appendix, Figs. S31 and S32). Therefore, we hypothesized that lipid peroxidation of the plasma membrane could play a role in contributing to the reduction in the membrane tension. When an inhibitor is added to the ferroptotic cells, phospholipid peroxidation is terminated, and membrane lesion repair begins. In the area of membrane damage, that is, the region with low membrane tension, the cells are repaired by exocytosis, as shown in ROI 1a- 4 h of Fig. 3A. Stimulation with ferrostatin-1 resulted in repair of the cell membrane, gradually restoring the membrane tension to the level observed in the control group (Fig. 3D). Combining the results of Figs. 1A and 3A, we thus suggest that at the onset of ferroptosis, the plasma membrane initially exhibits a decrease in membrane tension, followed by an increase in membrane permeability.

Discussion

Deciphering the mechanism of ferroptosis using membrane tension and morphology of the plasma membrane and the nuclear envelope are hampered by a lack of noninvasive, real-time, and signal-distinguishable molecular tools. One way to address this important problem is to use molecular probes that can simultaneously target the plasma membrane and the nuclear envelope and exhibit ultra-mechanosensitivity. Such probes could then be used to obtain high temporal and spatial resolution images using FLIM. To tackle these challenges, we proposed a hybrid strategy that involves combining hydrophilic–lipophilic properties and electronic push–pull ability to design robust molecular probes. Hydrophilic–lipophilic properties are essential to facilitate membrane targeting by the probes. The probes with high lipophilicity facilitate rapid cellular internalization and a short retention time in the membrane. By contrast, the probes with high hydrophilicity are repelled by the membrane and cannot insert into the membrane. Thus, DF1 and DF4 with both hydrophilic and lipophilic groups exhibit enhanced membrane targeting ability. Furthermore, to develop probes with ultrasensitive response to membrane tension, the push–pull characteristics of the probes is crucial, in addition to the molecular torsional properties. Optimized structures calculated using DFT/TD-DFT indicate that DF1 with strong electron-withdrawing groups could potentially exhibit ultrasensitivity to membrane tension.

We demonstrated the exquisite mechanosensitive properties of DF1 using FLIM imaging of GUVs and cell osmotic shock experiments. The colocalization experiments indicate that DF1 can target the plasma membrane both in the nonstimulated and ferroptotic cells. Thus, DF1 was evaluated for monitoring the membrane tension and morphology of the plasma membrane and nuclear envelope during ferroptosis induced using different drugs. In light of the imaging results, we propose a dynamic mechanism based on the membrane tension and morphology of the plasma membrane and nuclear envelope in the processes of ferroptosis. As shown in Scheme 2A, for the cells in a preferroptotic state, the mechanosensitive probe DF1 targets the plasma membrane, exhibiting a large fluorescence lifetime as represented by red pseudocolor. Then, when the cells are stimulated with both the activators and inhibitors of ferroptosis, the local membrane tension of the plasma membrane is reduced and is thus pseudocolored with different colors. In low-tension regions, repair of membrane lesions takes place by exocytosis. Then, in the presence of only the activator, at the initial stages of ferroptosis, a decrease of the fluorescence lifetime of DF1 in the plasma membrane indicates a continuous decline in the membrane tension, and the fluorescence lifetime pseudocolor changes from red to yellow. DF1 was then internalized and targets the nuclear envelope to afford a deep green pseudocolor. The difference between the membrane tension of the plasma membrane and nuclear envelope results in a large difference in the fluorescence lifetime of DF1, reflected by the marked change in the pseudocolor. When the cells are at an intermediate ferroptotic state, the fluorescence lifetime of DF1 in the plasma membrane continues to decrease, which is very different from that of the nonstimulated cells, and the pseudocolor changes from yellow to deep green. The fluorescence lifetime of DF1 in the nuclear envelope also decreases, indicating that the membrane tension of the nuclear envelope is in decline during ferroptosis. It is worth noting that the membrane tension state of the nuclear envelope in the process of ferroptosis has been revealed by lifetime imaging. Interestingly, we found that as the degree of ferroptosis increased, the nuclear envelope began budding. We therefore defined the nuclear envelope budding as a sign that the cells are undergoing advanced ferroptosis. Interestingly, the fluorescence lifetime of DF1 in the nuclear envelope bubbles is lower than that of the nuclear envelope. Thus, the membrane tension of the bubbles is lower than that of the nuclear envelop, which may be favorable for releasing small biomolecules from the nucleus into the cytoplasm at the later stages of ferroptosis. When the cells arrive at the ferroptotic necrotic state, the membrane tension of the plasma membrane and nuclear envelope are very low, and the nuclear envelope is ruptured. To monitor the process of the nuclear envelope bubble generation, we performed time-lapse FLIM imaging of advanced ferroptotic cells. As shown in the time lapse for advanced ferroptosis in Scheme 2A, the diameter of the nuclear envelope bubble “a” is smaller than that of “c,” and the diameter of the nuclear envelope “b” is larger than that of “d.” This suggests that for advanced ferroptosis, the generation of a nuclear envelope bubble is accompanied by shrinkage of the nuclear envelope, while the morphology of the plasma membrane changed only slightly in the advanced ferroptosis. With the progression of the time-lapse scanning for the advanced ferroptotic state, the membrane tension of the plasma membrane, nuclear envelope, and nuclear envelope bubble continues to decline.

Scheme 2.

Schematic summary of the proposed mechanism of ferroptosis. (A) Schematic representation of the mechanism during ferroptosis by imaging the fluorescence lifetime of DF1. Among them, the membrane tension changes of the plasma membrane, nuclear envelope, or nuclear envelope budding are reflected in the dashed rectangle. The color is used to distinguish the fluorescence lifetime of DF1. “a” and “c” represent the outer diameter of the nuclear envelope bubble, and “b” and “d” represent the outer diameter of the nuclear envelope. Among them, “a” < “c,” “b” > “d.” (B) The changes in the membrane tension of the plasma membrane, the nuclear envelope, or the nuclear envelope budding at each stage of ferroptosis are summarized, respectively. With the development of ferroptosis, the membrane tension of all these observed membrane systems declines. (C) Comparisons of the membrane tension of the different membrane systems in single cells at various stages of ferroptosis are summarized. Regardless of the stage, the membrane tension is in the order of the plasma membrane > nuclear envelope > nuclear envelope bubble.

We have summarized the results of the membrane tension and morphology of the plasma membrane, nuclear envelope, and nuclear envelope bubble for each ferroptotic state as obtained by FLIM imaging. The plasma membrane, nuclear envelope, and nuclear envelope bubble membrane tension were compared (Scheme 2B). From which, we found that the membrane tension of the plasma membrane, nuclear envelope, and nuclear envelope bubble all showed varying degrees of persistent tension decrease during the ferroptotic process. Where the plasma membrane, as revealed by the fluorescence lifetime changes of DF1, exhibits the most significant membrane tension changes. This could be attributed to the continuous destruction and permeation of the membrane system structure leading to an increase of water content during the process of ferroptosis. Scheme 2C displays a comparison of the membrane tension of the plasma membrane, nuclear envelope, and nuclear envelope bubble at the level of a single cell for each ferroptotic state. We found that the membrane tension of the plasma membrane is always greater than that of the nuclear envelope. While the membrane tension of the nuclear envelope bubble is always slightly smaller than that of the nuclear envelope during the nuclear envelope budding process.

With this research, a hybrid strategy for designing probes has been proposed, combining hydrophilicity and lipophilicity and the ability to donate and accept charge, which may lead to differences in membrane targeting and fluorescence lifetime sensitivity. This strategy can be applied for the development of robust lifetime imaging probes for the evaluation of a wide range of biological processes. Mechanosensitive probe DF1 exhibited both plasma membrane and nuclear envelope targeting and ultrasensitive fluorescence lifetime response to membrane tension. Through our research, it was possible to propose a mechanism for the process of ferroptosis and different stages of the ferroptotic process could be monitored in real time. Therefore, we formulated a dynamic mechanism based on membrane tension and morphology of the plasma membrane and nuclear envelope during ferroptosis, including: 1) membrane tension and morphological changes of the plasma membrane and nuclear envelope could be investigated using the mechanosensitive probe DF1 via quantitatively analyzable fluorescence lifetimes; 2) the dynamics of the nuclear membrane budding process during ferroptosis could be visualized in real time. The budding phenomenon of the nuclear envelope can be used as a marker for late-stage ferroptosis; 3) during ferroptosis, the membrane tension of the plasma membrane, nuclear envelop, and nuclear envelope bubble decreases. The membrane tension of the plasma membrane is always larger than that of the nuclear envelope, and the membrane tension of the nuclear envelope is also slightly larger than that of the nuclear membrane bubble; 4) at the onset of ferroptosis, the plasma membrane initially shows a decrease in the membrane tension, followed by an increase in the membrane permeability. Repair of damaged membranes takes place in the low membrane tension regions through exocytosis. As such, this study provides important guidance to help evaluate the membrane tension and morphology of the plasma membrane, nuclear envelope, and nuclear envelope bubble and provides insights into the dynamic mechanism of ferroptosis. We expect that this research will promote a more comprehensive understanding of ferroptosis mechanisms, assist investigation of biomarkers and signaling pathways of ferroptosis, and facilitate the development of drugs for diseases associated with ferroptosis.

Materials and Methods

Fluorescence Imaging.

For the FLIM imaging experiments of 4T1 cells induced by erastin stained with DF1, eight groups of the 4T1 cells were seeded in the 35 mm culture dishes for 24 h. The cells were incubated with 10 μM of erastin for 0, 30, 60, and 90 min and 0 to 4 μM erastin for 12 h, respectively. Then, the cells were washed with PBS for three times, and 1 mL of fresh medium was added. Furthermore, the cells were incubated with 10 μM of DF1 at 37 °C for 10 min. Without washing, the cells were visualized by FLIM imaging. λEx = 480 nm; λEm = 550 to 750 nm.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Movie of the dynamic behavior of non-stimulated cells plasma membrane based on FLIM imaging for the data shown in Figure S28.

3D FLIM movie of plasma membrane for the data shown in Figure S38a.

3D FLIM movie of plasma membrane and nuclear envelope for the data shown in Figure S38b.

3D FLIM movie of plasma membrane, nuclear envelope, and nuclear envelope bubble for the data shown in Figure S38c.

Movie of the dynamic behavior of the nuclear envelope budding as shown in Figure 2A.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China 21877048 (W.L.); National Natural Science Foundation of China 22077048 (W.L.); National Natural Science Foundation of China 22277014 (W.L.); Guangxi Natural Science Foundation 2021GXNSFDA075003 (W.L.); Guangxi Natural Science Foundation AD21220061 (W.L.); Startup fund of Guangxi University A3040051003 (W.L.); and Open Research Fund of the School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Henan Normal University 2020ZD01 (T.D.J.).

Author contributions

X.L. and W.L. designed research; X.L. J.Y. and Q.Z. performed research; W.L. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; X.L., Y.Z., and W.L. analyzed data; and X.L., W.L. and T.D.J. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. B.M. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

Contributor Information

Tony D. James, Email: chstdj@bath.ac.uk.

Weiying Lin, Email: weiyinglin2013@163.com.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Fuchs Y., The therapeutic promise of apoptosis. Science 363, 1050–1051 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu P., et al. , Pyroptosis: Mechanisms and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 6, 128 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shan B., Pan H., Najafov A., Yuan J., Necroptosis in development and diseases. Genes Dev. 32, 327–340 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Debnath J., Gammoh N., Ryan K. M., Autophagy and autophagy-related pathways in cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 560–575 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yan H.-F., et al. , Ferroptosis: Mechanisms and links with diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 6, 49 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixon S. J., et al. , Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 149, 1060–1072 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang D., Chen X., Kang R., Kroemer G., Ferroptosis: Molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell Res. 31, 107–125 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakamura T., et al. , Phase separation of FSP1 promotes ferroptosis. Nature 619, 371–377 (2023), 10.1038/s41586-023-06255-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Krusenstiern A. N., et al. , Identification of essential sites of lipid peroxidation in ferroptosis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 19, 719–730 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng J., Conrad M., The metabolic underpinnings of ferroptosis. Cell Metab. 32, 920–937 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao W., Wang X., Zhou Y., Wang X., Yu Y., Autophagy, ferroptosis, pyroptosis, and necroptosis in tumor immunotherapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 7, 196 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reza Sepand M., et al. , Ferroptosis: Environmental causes, biological redox signaling responses, cancer and other health consequences. Coord. Chem. Rev. 480, 215024 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang N., et al. , Stimuli-responsive ferroptosis for cancer therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 3955–3972 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dimanche-Boitrel M. T., Meurette O., Rebillard A., Lacour S., Role of early plasma membrane events in chemotherapy-induced cell death. Drug Resist. Updat. 8, 5–14 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buendia B., Courvalin J. C., Collas P., Dynamics of the nuclear envelope at mitosis and during apoptosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 58, 1781–1789 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ungricht R., Kutay U., Mechanisms and functions of nuclear envelope remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 229–245 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Denais C. M., et al. , Nuclear envelope rupture and repair during cancer cell migration. Science 352, 353–358 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Le Roux A. L., Quiroga X., Walani N., Arroyo M., Roca-Cusachs P., The plasma membrane as a mechanochemical transducer. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 374, 20180221 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee J., Abdeen A. A., Li Y., Goonetilleke S., Kilian K. A., Gradient and dynamic hydrogel materials to probe dynamics in cancer stem cell phenotypes. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 4, 711–720 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaudhuri O., et al. , Extracellular matrix stiffness and composition jointly regulate the induction of malignant phenotypes in mammary epithelium. Nat. Mater. 13, 970–978 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gustin M. C., et al. , A mechanosensitive ion channel in the yeast plasma membrane. Science 242, 762–765 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riggi M., et al. , Decrease in plasma membrane tension triggers PtdIns(4,5)P2 phase separation to inactivate TORC2. Nat. Cell Biol. 20, 1043–1051 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsujita K., Takenawa T., Itoh T., Feedback regulation between plasma membrane tension and membrane-bending proteins organizes cell polarity during leading edge formation. Nat. Cell Biol. 17, 749–758 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clegg R. M., Schneider P. C., “Fluorescence lifetime-resolved imaging microscopy: A general description of lifetime-resolved imaging measurements” In Fluorescence Microscopy and Fluorescent Probes, Slavík J., Ed. (Springer, Boston MA, 1996) pp. 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borlinghaus R., Kuschel L., Spectral fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy: New dimensions with Leica TCS SP5. Nat. Methods 3, 868 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanaoka K., et al. , General design strategy to precisely control the emission of fluorophores via a twisted intramolecular charge transfer (TICT) process. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 19778–19790 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frisch M. J., et al. , Gaussian09, Revision D.01. (Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford, CT, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fonseca Guerra C., Snijders J. G., Te Velde G., Baerends E. J., Towards an order-N DFT method. Theor. Chem. Acc. 99, 391–403 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blase X., Duchemin I., Jacquemin D., The Bethe-Salpeter equation in chemistry: Relations with TD-DFT, applications and challenges. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 1022–1043 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo J., et al. , Ferroptosis: A novel anti-tumor action for cisplatin. Cancer Res. Treat. 50, 445–460 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Du R., et al. , Mechanism of ferroptosis in a rat model of premature ovarian insufficiency induced by cisplatin. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–16 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lau A. H., Apoptosis induced by cisplatin nephrotoxic injury. Kidney Int. 56, 1295–1298 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang X., Martindale J. L., Holbrook N. J., Requirement for ERK activation in cisplatin-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 39435–39443 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yagoda N., et al. , RAS–RAF–MEK-dependent oxidative cell death involving voltage-dependent anion channels. Nature 447, 865–869 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang X., Stockwell B. R., Conrad M., Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 266–282 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Movie of the dynamic behavior of non-stimulated cells plasma membrane based on FLIM imaging for the data shown in Figure S28.

3D FLIM movie of plasma membrane for the data shown in Figure S38a.

3D FLIM movie of plasma membrane and nuclear envelope for the data shown in Figure S38b.

3D FLIM movie of plasma membrane, nuclear envelope, and nuclear envelope bubble for the data shown in Figure S38c.

Movie of the dynamic behavior of the nuclear envelope budding as shown in Figure 2A.

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.