Meiosis, the specialized cell division cycle that produces gametes, requires intricate chromosomal choreography (1). Maternal and paternal chromosomes pair and align with each other, exchange genetic information through a tightly regulated repair of breaks in the DNA, and then undergo two sequential divisions. These events are mediated by tethering chromosomes to motor proteins and cytoskeletal filaments but also through the regulated construction, and subsequent destruction of dedicated chromosomal scaffolds. Work in this issue of PNAS sheds light on the role of the ubiquitin pathway in regulating one of the quintessential meiotic structures—the synaptonemal complex (2).

The synaptonemal complex debuted on the chromosome biology stage as striking, ladder-like threads in 1950s negative-stained electron micrographs (3). As one of the few clearly delineated nuclear structures, it was an important tool in early studies of nuclear organization and chromosome dynamics (4). Extensive work since then has led to a deep understanding of the molecular genetics of the synaptonemal complex in diverse model organisms (1). The synaptonemal complex brings the parental chromosomes in close proximity, aligning them end-to-end and placing them ~150 nm apart. This positions homologous sequences from the two parental chromosomes adjacent to each other and in register, allowing for the formation of genetic exchanges, called crossovers. In addition to this “structural” role as the interface between the two parental chromosomes, synaptonemal complex components directly interact with the DNA repair machinery and with crossover regulators to control the number and distribution of crossovers.

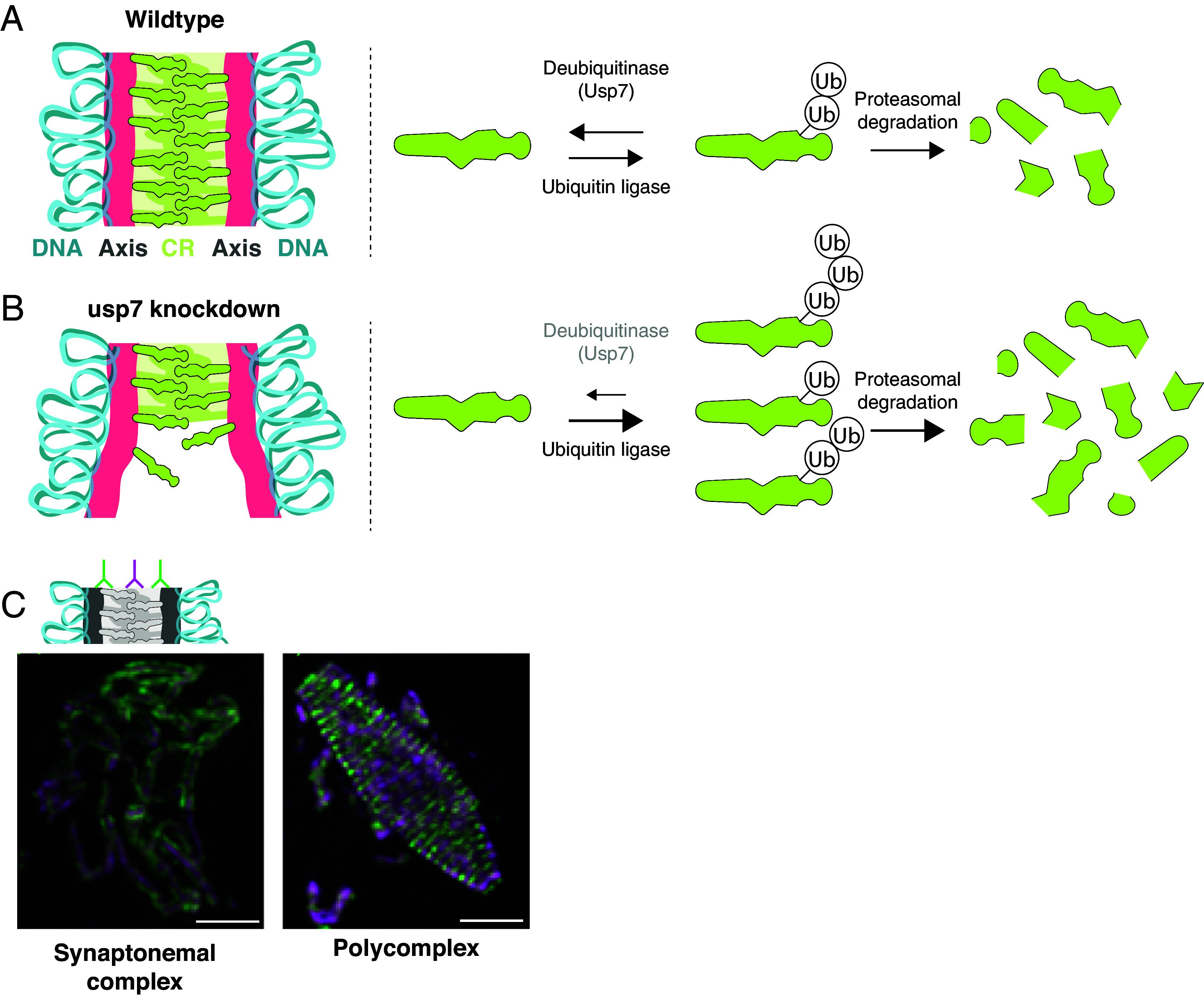

The synaptonemal complex moves chromosomes by undergoing distinct stages of assembly and disassembly (1). First, each chromosome assembles a stiff proteinaceous structure called the axis (also referred to as lateral or axial elements; see Fig. 1A). Axis assembly molds chromatin into an array of loops stacked at their base—a crucial configuration for many meiotic processes. The synaptonemal complex then assembles by sandwiching a second element—the central region—in between two parallel axes. (Some organisms also include a more poorly defined “central element” at the very middle of the synaptonemal complex.) Complete assembly of the synaptonemal complex, spanning all chromosomes end-to-end, defines the meiotic stage known as pachytene (“thick threads” in Greek). Complete assembly is also required for crossover formation and for tight regulation of their number and distribution. Following the formation of crossovers, the synaptonemal complex disassembles and the two parental chromosomes start to drift apart, remaining connected only by crossovers, which allow them to align on the meiotic spindle and segregate accurately into the gametes.

Fig. 1.

Cartoons depicting the synaptonemal complex (axes, salmon; central region [CR], green; chromosomes [DNA], blue) in wild-type flies (A) and upon usp7 knockdown (B). The right side of (A) and (B) depicts a potential mechanism by which Usp7 regulates synaptonemal complex components. usp7 knockdown could lead to increased degradation of synaptonemal complex proteins, resulting in an unbalanced deubiquitinase and ubiquitin ligase activity. Lower levels of synaptonemal complex components would result in an inability to maintain a fully assembled synaptonemal complex. (C) Fluorescent images of the fly synaptonemal complex (Left) and a polycomplex (Right). The cartoon depicts antibodies that label regions near the axes (green), which form parallel tracks ~120 nm apart, and the center of the synaptonemal complex (magenta). Polycomplexes resemble stacked synaptonemal complexes, resulting in alternating green and magenta threads with a periodicity similar to the width of the synaptonemal complex assembled on chromosomes. (Scale bar, 0.2 µm.) Images adapted from ref. 5, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

In PNAS, Lake et al. report an extensive set of genetic and cytological experiments to reveal that the activity of the ubiquitin protease Usp7 regulates synaptonemal complex dynamics in D. melanogaster.

In some species, the synaptonemal complex orchestrates other specialized chromosome dynamics. In silk moths, synaptonemal complex components form a so-called “bivalent bridge”: a thick structure that forms between the parental chromosomes following the disassembly of the synaptonemal complex (6). The bivalent bridge is maintained until the first meiotic division and helps position chromosomes in female moths, which lack crossovers. In Caenorhabditis elegans nematodes, the synaptonemal complex redistributes to one end of their holocentric chromosomes following crossover formation. This redistribution controls the two-step removal of sister chromatid cohesion in the first and second meiotic divisions—a canonical function of point centromeres (7).

In this issue of PNAS, Lake et al. reveal that the activity of the ubiquitin protease Usp7 regulates synaptonemal complex dynamics in Drosophila melanogaster (2). Through an extensive set of genetic and cytological experiments, they found that usp7 knockdown results in an inability to maintain an assembled synaptonemal complex (Fig. 1 A and B). In control flies, extensive threads of synaptonemal complex are maintained throughout pachytene. In usp7 knockdown flies the synaptonemal complex assembles normally in early pachytene and its morphology is unaffected. However, it later fragments and disassembles prematurely, revealing that ubiquitin removal regulates synaptonemal complex maintenance.

The consequences of the synaptonemal complex maintenance defect are severe. Knockdown flies have a reduced number of crossovers, leading to incorrect chromosome segregation into the eggs. As would be expected, this results in a large number of aneuploid, inviable progeny.

Given the interdependencies between various meiotic processes, it was important to demonstrate that other aspects of meiotic chromosome regulation are not altered by usp7 knockdown. The authors find that oocyte designation and development, sister chromatid cohesion, and double-strand break formation are unaffected. These data suggested that the synaptonemal complex phenotype in usp7 knockdown flies is the result of a direct effect on synaptonemal complex components. To further support this idea, the authors analyzed chromatin-free assemblies of synaptonemal complex material called polycomplexes [Fig. 1C; (8)] and found them to be smaller and narrower in usp7 knockdown flies. Given that polycomplexes are not associated with chromosomes and can form even in nonmeiotic cells that express synaptonemal complex components, the effects on their morphology strongly support a direct effect on synaptonemal complex components.

Taken together, the results by Hawley et al. support the elegant hypothesis that Usp7, by deubiquitination of a synaptonemal complex component or components, slows down their degradation, stabilizing full-length synaptonemal complexes on chromosomes [Fig. 1A; (2)]. Knocking down Usp7 destabilizes the synaptonemal complex by making it more susceptible to proteasomal degradation resulting in the observed maintenance phenotype (Fig. 1B). Alternatively, the protein deubiquitinated by Usp7 may not be a structural component of the synaptonemal complex but one that indirectly regulates synaptonemal complex stability and maintenance. Future work to identify the target(s) of deubiquitination will help differentiate between these hypotheses.

The “maintenance” function of Usp7 identified by Lake et al. (2) could be related to the evolution of the meiotic program. Studies in various organisms revealed that the duration of pachytene is highly variable. For instance, in budding yeast, the synaptonemal complex disassembles quickly after crossover formation, whereas in worms, completely synapsed chromosomes are maintained for ~24 h. An intriguing possibility is that nodes in the ubiquitin machinery—such as Usp7—are crucial in determining such temporal changes during evolution.

The effect on synaptonemal complex stability underscores an important gap in our understanding of its disassembly. The ladder-like appearance of the synaptonemal complex initially suggested that it assembles like cytoskeletal filaments. If that were the case, the stabilizing effects of Usp7 may be specifically required at the ends of synaptonemal complex threads, akin to the stabilizing effects of end-binding proteins on actin filaments and microtubules. However, more recent work suggested that the synaptonemal complex has liquid properties, with subunits constantly diffusing into and within the synaptonemal complex (9). In this scenario, deubiquitination can control synaptonemal complex subunit levels throughout the nucleoplasm, with lower levels manifesting as shorter and incomplete synaptonemal complex structures. A better understanding of the mechanism of action of Usp7 could help shed light on the functional importance of these different material states of the synaptonemal complex.

The study by Lake et al. (2) contributes to a growing body of work that points to the importance of posttranslational modifications in regulating synaptonemal complex dynamics (10). Interestingly, the Hawley lab previously identified a ubiquitin E3 ligase, Sina, that is required for synaptonemal complex assembly (5). Ubiquitin E3 ligase complexes play related roles in various model organisms, including flies (11), worms (12), yeast (13, 14), plants (15), and mice (16). The importance of synaptonemal complex component homeostasis is further underscored by the localization of the proteasome itself to meiotic chromosomes in mice, yeast, and worms (17, 18).

Curiously, the long-standing, intimate association between the ubiquitin machinery and the synaptonemal complex may have set the stage for protein repurposing between the two. Recent work found that Skp1, an essential member of the Skp1/Cullin/F-box (SCF) ubiquitin E3 ligase complex, localizes to the synaptonemal complex and is essential for its assembly in C. elegans and Pristionchus pacificus (19, 20). These studies indicate that Skp1 is a structural component of the synaptonemal complex and suggest that it was co-opted to this role at least 100 Mya. The C. elegans Skp1 homolog also happens to be the unexpected “missing piece” that stabilizes synaptonemal complex components expressed in bacteria. This allowed Yumi Kim et al. to isolate recombinant central region protein complexes—the first such purification reported (19). Future work in other model organisms could help identify whether cooptation of ubiquitin machinery components has been a leitmotif during synaptonemal complex evolution.

Acknowledgments

We are supported by grants R35GM128804 from NIGMS and 2219605 from NSF.

Author contributions

L.E.K. and O.R. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

See companion article, “The deubiquitinase Usp7 in Drosophila melanogaster is required for synaptonemal complex maintenance,” 10.1073/pnas.2409346121.

Contributor Information

Lisa E. Kursel, Email: lisa.kursel@utah.edu.

Ofer Rog, Email: ofer.rog@utah.edu.

References

- 1.Zickler D., Kleckner N., Meiosis: Dances between homologs. Annu. Rev. Genet. 57, 1–63 (2023), 10.1146/annurev-genet-061323-044915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lake C. M., et al. , The deubiquitinase Usp7 in Drosophila melanogaster is required for synaptonemal complex maintenance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 121, e2409346121 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moses M. J., Chromosomal structures in crayfish spermatocytes. J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 2, 215–218 (1956). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carpenter A. T., Electron microscopy of meiosis in Drosophila melanogaster females: II. The recombination nodule–A recombination-associated structure at pachytene? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 72, 3186–3189 (1975). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hughes S. E., et al. , The E3 ubiquitin ligase Sina regulates the assembly and disassembly of the synaptonemal complex in Drosophila females. PLoS Genet. 15, e1008161 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiang Y., et al. , Multiple reorganizations of the lateral elements of the synaptonemal complex facilitate homolog segregation in Bombyx mori oocytes. Curr. Biol. 34, 352–360.e4 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinez-Perez E., et al. , Crossovers trigger a remodeling of meiotic chromosome axis composition that is linked to two-step loss of sister chromatid cohesion. Genes Dev. 22, 2886–2901 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes S. E., Hawley R. S., Alternative synaptonemal complex structures: Too much of a good thing? Trends Genet. 36, 833–844 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rog O., Köhler S., Dernburg A. F., The synaptonemal complex has liquid crystalline properties and spatially regulates meiotic recombination factors. Elife 6, e21455 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao J., Colaiácovo M. P., Zipping and unzipping: Protein modifications regulating synaptonemal complex dynamics. Trends Genet. 34, 232–245 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barbosa P., et al. , SCF-Fbxo42 promotes synaptonemal complex assembly by downregulating PP2A-B56. J. Cell Biol. 220, e202009167 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brockway H., Balukoff N., Dean M., Alleva B., Smolikove S., The CSN/COP9 signalosome regulates synaptonemal complex assembly during meiotic prophase I of Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004757 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu Z., Bani Ismail M., Shinohara M., Shinohara A., SCFCdc4 ubiquitin ligase regulates synaptonemal complex formation during meiosis. Life Sci. Alliance 4, e202000933 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang X., et al. , The ubiquitin-proteasome system regulates meiotic chromosome organization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 119, e2106902119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ren L., et al. , The E3 ubiquitin ligase DESYNAPSIS1 regulates synapsis and recombination in rice meiosis. Cell Rep. 37, 109941 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guan Y., et al. , SCF ubiquitin E3 ligase regulates DNA double-strand breaks in early meiotic recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, 5129–5144 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao H. B. D. P., et al. , A SUMO-ubiquitin relay recruits proteasomes to chromosome axes to regulate meiotic recombination. Science 355, 403–407 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahuja J. S., et al. , Control of meiotic pairing and recombination by chromosomally tethered 26 S proteasome. Science 355, 408–411 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blundon J. M., et al. , Skp1 proteins are structural components of the synaptonemal complex in C. elegans. Sci. Adv. 10, eadl4876 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kursel L. E., Goktepe K., Rog O., Skp1 is a conserved structural component of the meiotic synaptonemal complex. bioRxiv [Preprint] (2024). 10.1101/2024.06.24.600447 (Accessed 30 August 2024). [DOI]