Abstract

Introduction

Sedentary behaviour is a public health problem. We mainly have sedentary behaviour at work, transforming them into occupational risk. To our knowledge, there is no intervention study on the reduction of occupational sedentary behaviour in a real work situation and its impact on health and biomarkers of stress. The main objective is to study changes in sedentary behaviour following a behavioural intervention (sit-and-stand desk and cycle ergometer).

Methods and analysis

This is a randomised controlled trial in cross-over design conducted in a single centre. The study will be proposed to emergency medical dispatchers of Clermont-Ferrand. Each volunteer will be followed during three cycles of 1 week (3 weeks in total). Each 1-week cycle is made up of 12 hours of work (three conditions: a control and two interventions), 12 hours of successive rest and 6 days of follow-up. For each condition, the measurements will be identical: questionnaire, measure of heart rate variability, electrodermal activity and level of physical activity, saliva and blood sampling. The primary outcome is sedentary behaviour at work (ie, number of minutes per day standing/active). Data will be analysed with both intention-to-treat and per protocol analysis. A p<0.05 will be considered as indicating statistical significance.

Ethics and dissemination

The study protocol has been approved by the Ethics Committee Ouest IV, FRANCE. The study is registered in ClinicalTrials.gov. All patients will be informed about the details of the study and sign written informed consent before enrolment in the study. Results from this study will be published in a peer-reviewed journal. This study involves human participants and was approved by Comité de protection des personnes Ouest IVCPP reference: 23/132-2National number: 2022-A02730-43.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Occupational Stress, ACCIDENT & EMERGENCY MEDICINE, Randomized Controlled Trial, PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

The study uses a randomised controlled trial in cross-over design to assess the reduction of sedentary behaviour following a short-term behavioural intervention.

The study includes a holistic approach by measuring concomitantly perception of work and measures of stress (salivary and blood biomarkers) compared with previous studies.

This study is a preliminary study, aiming to determine, on a limited number of staff, the impact of the provision of tools that can reduce sedentary behaviour in a population frequently subjected to stressful events. A parallel arm design, requiring a larger number of subjects, may be considered in the second instance, depending on the results of this first study.

Introduction

Sedentary behaviour has increased over time and is now one of the greatest public health problems.1 Sedentary activities can be defined as any arousal behaviour characterised by energy expenditure ≤1.5 Metabolic Equivalent of Task (METs) while sitting or lying down.2 It must be distinguished from physical inactivity, which is characterised by an insufficient level of physical activity of moderate to high intensity.3 In France, a cross-sectional study was conducted on a cohort of more than 35 000 employed adults, aiming to estimate the average duration of sitting time during a typical workday, which was found to be approximately 12 hours.4 We mainly have sedentary behaviour at work,5 and, therefore, sedentary behaviour must be considered as an occupational risk.6 7 A sedentary lifestyle has been extensively linked to various adverse health effects, as supported by numerous epidemiological studies. The negative health impacts of a sedentary lifestyle have been observed to intensify with increased total daily sedentary time.8 Prolonged sedentary behaviour has been associated with elevated risks of all-cause mortality,9,11 cardiovascular disease (CVD)911,13 and certain cancers,14 as well as an increased risk for metabolic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia.11 13 Sedentary behaviour is also associated with weight gain, adiposity, chronic inflammation and an increased risk of obesity. Additionally, musculoskeletal issues such as back pain and osteoporosis have been linked to a sedentary lifestyle.15,17 Furthermore, sedentary behaviour is strongly related to a deterioration in mental health.18 19 Indeed, sedentary behaviour might be linked to stress through different ways, although the literature on the relations between sedentary behaviour and stress is heterogeneous. A systematic review concluded to insufficient evidence for the association between the total duration of sedentary behaviour and stress, particularly when using self-report questionnaire.20 However, a recent laboratory study showed that during a high-stress situation, people with sedentary behaviour were those with the highest physiological response to stress (greater cortisol responses as well as greater cardiovascular and inflammatory responses).21 Moreover, a meta-analysis on sedentary behaviour reductions found evidence for improvement of some cardiometabolic risk biomarkers simply by breaking the sedentary lifestyle for a few minutes every hour.22 The evidence from literature strongly supports the significant and wide-ranging negative effects of a sedentary lifestyle on health, emphasising the importance of reducing sedentary behaviour, especially in the workplace. Some professions are inherently more sedentary, such as the emergency medical dispatchers (EMDs) of the mobile intensive care unit (MICU) and the firefighters of the departmental fire and rescue centre (Centre opérationnel départemental d’incendie et de secours—CODIS) are responsible for managing emergency calls. They are mostly in a seated position in front of a desk. In addition, they are particularly exposed to stress due to the specific characteristics of their work environment (dealing with life-threatening emergencies, high workload, helping people in major distress).23,25 The stress experienced by EMDs can result in work-related exhaustion as well as impaired decision-making caused by misinterpreting the severity of the patient’s condition.26 These factors collectively contribute to higher rates of sick leave and increased turnover for EMDs towards less demanding professions.27 We previously demonstrated that emergency calls pose specific risks for EMDs, experiencing higher levels of perceived stress and a greater elevation in cortisol levels.23

In recent years, numerous studies have investigated the benefits of reducing sedentary behaviour. Various strategies have emerged to reduce the time spent sitting at work, such as active workstations,28,30 with promising results.31,34 Nevertheless, the use of sit-and-stand desk or cycle ergometer may differ in benefits between some working conditions.35 Hence, interventions ought to be tailored to the specific context and working environment of the populations they aim to reach.36 In real working conditions, interventions are often long (several months of follow-up), considering that the dose needs to be large and sustained to be impactful. However, given the specificities of EMDs, particularly with regard to the management of life-threatening emergencies, imposing a framework for reducing sedentary behaviour over a long period may be hard to implement, without first carrying out a short-term pilot study assessing the benefits/limitations of the different active workstation.37 More specifically for EMDs, the provision of sit-and-stand desk or cycle ergometer may not guarantee their use. Moreover, even short-term interventions have demonstrated high metabolic benefits. For example, a previous interventional laboratory study with a short-term design (8-hour conditions on 3 separate days) showed significant improvement in cardiometabolic markers with sedentary breaks.38 However, to our knowledge, there is no short-term intervention study on the reduction of occupational sedentary behaviour in a real stressful working situation, such as working in a MICU/CODIS with life-threatening situations. Furthermore, most studies on sedentary behaviour generally focused on a small number of measures, limiting the exploration of links between covariates. Very interestingly, biomarkers of stress can be influenced both by stressful events and sedentary behaviour.22 39 Among biomarkers of stress, heart rate variability (HRV) is a common biomarker reflecting both acute and chronic stress.40 Other common biomarkers are those derived from the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, such as cortisol or dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate (DHEA-S).39 Cytokines or appetite regulation hormones have also been proposed as biomarkers of stress.41 42 In addition, stress at work can also be measured by several validated questionnaires of psychosocial risk, such as the job-demand-control-support (JDCS) model of Karasek or the effort reward imbalance model of Siegrist.43 44 However, no study covered a holistic approach by measuring concomitantly perception of work and most biomarkers, in an interventional study aiming at decreasing sedentary behaviour, in highly sedentary and stressful phone operators of the MICU/CODIS.

The main objective will be to study changes in sedentary behaviour following a behavioural intervention (sit-and-stand desk, and cycle ergometer). More specifically, we want to determine the impact of the provision of sit-and-stand desk/cycle ergometer on sedentary behaviour in a population frequently subjected to stressful events. Secondary objectives will be to study (1) the short-term effects of the intervention on mental, physical and social health, measured subjectively (questionnaires) and objectively (biomarkers of stress such as autonomic nervous system, cortisol and DHEA-S) and (2) the factors influencing the benefits of the intervention (sociodemographic and lifestyle, personality and perception of work).

Methods and analysis

Study design

This study is a randomised controlled trial in cross-over design conducted in a single centre. The study is registered in ClinicalTrials.gov after the French Ethics Committee’s approval.

Participants

The study will be proposed to Emergency medical service dispatchers and firefighters from the departmental fire and rescue operational centre (CODIS) of Clermont-Ferrand. Firefighters in the proposed trial only perform call centre work. The participants will be included in this study if they meet all of the following criteria: being an EMDs or a firefighter from the departmental fire and rescue operational centre (CODIS), being able to use the sit-stand desk and the cycle ergometer, being able to give an informed consent to participate in research, being affiliated with a Social Security scheme. The participants will not be included if they are not affiliated to a health insurance, part of protected persons (minors, pregnant women, breastfeeding women, guardianship, curatorship, deprived of freedoms, safeguard of justice) or if they do not want to complete the written consent form.

Patient and public involvement

Emergency dispatch centre phone operators were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research. Volunteers are recruited by dissemination of information within their department and involved in the study from their inclusion. Presentations will be offered by the research team to participants after study completion to disseminate findings.

Randomisation

Following a cross-over design, the condition order will be randomised by random Latin squares, stratified by occupation. The biostatistician of the team has created the randomisation list, which will be incremented with the Redcap eCRF software. Blinding is not possible regarding the design and context of the study.

Study interventions

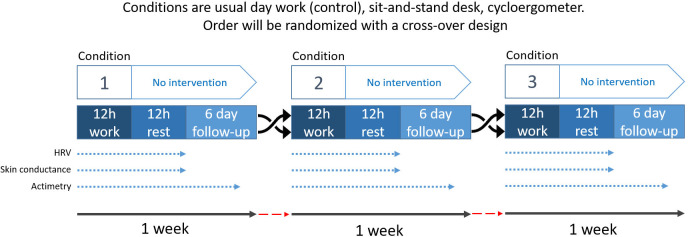

We plan to start the study in June 2024 and finish it in September 2026. During this period, each volunteer will be followed during three cycles of 1 week (3 weeks in total). Each 1-week cycle will be made up of 12 hours of work (three conditions: (1) one working day during which participants will be recommended to stand up for at least 5 min/hour (sit-stand desk), (2) a working day during which they can use a cycle ergometer installed under the desk and (3) a controlled working day without intervention), 12 hours of successive rest and 6 days of follow-up (just for the objective measurement of the level of physical activity/sedentary lifestyle). The 6 days of follow-up will be carried out under usual working conditions (no access to the sit-stand desk and the cycle ergometer). The time between two cycles may vary according to the constraints/schedules of the participants. The 3 weeks will not necessarily be consecutive (figure 1). In order to avoid the use/interest of the active workstations being based solely on a novelty effect, one of each active workstation will be available in the department. As part of the protocol and 6-day follow-up, participants will be asked to perform the control condition at their conventional desk (not active).

Figure 1. Study design. HRV, heart rate variability.

Outcomes

For each 1-week cycle, the measurements will be identical. All outcomes are presented in table 1.

Table 1. Synthesis of primary and secondary outcomes.

| Variables | Type of measures | Modalities to measure | Time of measures | Ref |

| Primary outcome | ||||

| Lifestyle | Sedentary behaviour | Actigraph wGT3X-BT | One week of measurement | 45 46 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| Autonomic nervous system | Heart rate variability | Zephyr BioHarness BT | 3 days of work, 24 hours of measure (3×24 hour) | 55 |

| Skin conductance—electrodermal activity (EDA) | Wristband electrodes—Empatica E4 | 3 days of work, 24 hours of measure (3×24 hour) | 56 | |

| Demographics | Age, gender, occupation, life and occupational events | Questionnaire | Once at inclusion | |

| Clinical measurements | Height, weight | Questionnaire | Once at inclusion | |

| Psychology and quality of life | Burn-out | Maslach Burn-Out Inventory | Once at inclusion | 57 |

| Perception of work | Job Content Questionnaire of Karasek | Once at inclusion | 58 | |

| Effort Reward Imbalance | Once at inclusion | 44 | ||

| Stress at home, fatigue, sleep quality and quantity, anxiety, mood, stress at work | Visual analogue scale of 100 mm | Beginning/end of each condition | ||

| Sleep quality, family support, burnout, job control, job demand, hierarchy support, colleagues support, effort reward imbalance | Visual analogue scale of 100 mm | Once at inclusion | 55 59 | |

| Lifestyle | Consumption of coffee/tea, alcohol, tobacco, cannabis and medication | Questionnaire | At inclusionBeginning/end of each condition | |

| Nutritional intake | Questionnaire/direct assessment by the clinical research assistant | At inclusionDuring each condition | ||

| Physical activity | Questionnaire | At inclusionBeginning/end of each condition | 45 46 | |

| Actigraph wGT3X-BT | One week of measurement | |||

| Sedentary behaviour | Questionnaire | At inclusionBeginning/end of each condition | ||

| Actigraph wGT3X-BT | One week of measurement | |||

| Allostatic load | Cortisol, DHEA-S, leptin, ghrelin, glycaemia, etc | Dry tube | Beginning/end of each condition | 41 42 60 61 |

| Saliva sampling | Beginning/end of each day+each 3 hour | |||

| BDNF | Dry tube, serum isolation and deep-freezing | Beginning/end of each condition | 62 | |

| Pro-inflammatory cytokines: IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, TNFα, etc | Dry tube, serum isolation and deep-freezing | Beginning/end of each condition | 63 | |

| NPY | Dry tube, serum isolation and deep-freezing | Beginning/end of each condition | 64 | |

BDNFbrain-derived neurotrophic factorDHEA-Sdehydroepiandrosterone sulphateNPYneuropeptide Y

The main outcome will be sedentary behaviour measured continuously during the entirety of each three 1-week cycle using the wGT3X-BT ActiGraph’s flagship activity monitor. Sedentary behaviour will be expressed as number of minutes per day standing/active during each condition. More specifically, we will detail the nature of postural comportments at work: standing, active, sitting not active and sitting active. We will further detail number of breaks of sedentary behaviour and their duration as well as quantification of intensity of active breaks: low, moderate or vigorous. Those classifications will also be applied in the analysis of leisure time recording. ActiGraph will be used to capture and record continuous, high-resolution physical activity and sleep/wake information. The Bluetooth Smart wGT3X-BT features ActiGraph’s validated 3-axis accelerometer and digital filtering technology and includes integrated wear time and ambient light sensors. It is the gold standard tool for measuring physical activity.45 46 It includes daily activity count (vector magnitude units), X, Y and Z-axis counts, vector amplitude, energy consumption, pedometer (steps per day), activity intensity level, including total hours of light, moderate, vigorous and very vigorous physical activity/sedentary time and metabolic equivalent. The GT3X+ is equipped with an inclinometer to judge the posture of participants as well as determine when the device is removed.

The secondary outcomes will be sedentary behaviour expressed as number of minutes per week standing/active during each condition.

TheHRV will be measured continuously during the 12 hours of work and the next 12 hours of rest. Several studies have established the association between HRV and stress. During chronic stress, the sympathetic nervous system is hyperactivated. Research has shown that people exposed to stressful situations tend to exhibit reduced HRV, which may indicate increased activation of the sympathetic nervous system and suppression of parasympathetic system activity.40 Measuring HRV can, therefore, be used as an objective indicator of stress. Zephyr BioHarness BT (Zephyr Technology, Annapolis, Maryland), a chest-mounted heart rate transmitter belt, which has a recording time of 26 hours, will be used. It can measure heartbeats per minute ranging from 25 to 240 and respiratory rates ranging from 3 to 70. In addition, Zephyr includes a 3-Axis accelerometer to measure movements of the trunk. The HRV data will be analysed following the guidelines set by the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society (Task Force). Both time and frequency domains will be used to investigate the HRV.47 Data will be analysed using Kubios HRV Software. We will apply a very low artefact correction. Multiple parameters will be examined in the time domain, including R–R intervals and their SD, the ratio of adjacent N–N intervals differing by more than 50 ms to the total number of N–N intervals (pNN50), and the square root of the average squared difference between successive R–R intervals (rMSSD). The parameters pNN50 and rMSSD are associated with high-frequency (HF) power, which in turn reflects parasympathetic activity. The spectral domain analysis will investigate HF (0.15–0.4 Hz) and low-frequency (LF) (0.04–0.15 Hz) power. HF power primarily represents parasympathetic (vagal) activity directed towards the sinus node, while LF power serves as an indicator of both parasympathetic and sympathetic functions. Normalised units (nu), which represent their relative values in relation to the total power minus the very LF (VLF) component, will be employed to assess LF and HF power components. Therefore, LFnu and HFnu are considered to reflect the most accurate measurements of sympathetic and parasympathetic activity, respectively. The LF/HF ratio, which indicates the balance between sympathetic and vagal influences, will also be calculated.48

Continuous measurement of electrodermal activity (EDA) will be conducted for a period of 12 hours during work and the subsequent 12 hours of rest. Numerous studies have demonstrated that measurements of EDA can offer reliable insights into an individual’s stress level.49 In stressful situations, the sympathetic nervous system is activated, leading to a series of physiological responses, including an increase in sweat gland activity. This increase in sweat gland activity translates into an increase in EDA, that is, an increase in skin conductance.50 For instance, when a person is confronted with a stressful situation, EDA generally increases compared with a calm state, and this increase can be detected and recorded using an electrodermograph.49 51 The Empatica E4 device will be used for this purpose. The measurements will be recorded in micro-Siemens and sampled at rates of 2, 4, 8, 16 and 32 Hz. The SC sensor (Q-Sensor-Affectiva, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA) is integrated into a wristband and can operate continuously for up to 24 hours when logging data. Additionally, it includes a built-in 3-Axis accelerometer to measure movements of the wrist.

Blood and saliva samples will be collected on each working day, at the beginning and end of the day, that is, two measures for blood samples, and every 3 hours, that is, 5 measures for saliva sampling. A nurse will take blood samples and participants will do a self-collection for saliva sampling. Saliva sampling will be collected with the use of dedicated Eppendorf’s, at the CHU of Clermont-Ferrand. The maximum volume of blood sampled in 1 day for this study will be 50 mL (5 tubes of 5 mL, 2 times per day), that is, a maximum of 150 mL over the total duration of the study per participant. Saliva and blood samples will both allow to measure biomarkers of stress such as cortisol, DHEA-S, leptin, ghrelin, glycaemia. Blood samples will also allow to measure brain-derived neurotrophic factor, neuropeptide Y and proinflammatory cytokines, which are all biomarkers of stress.39

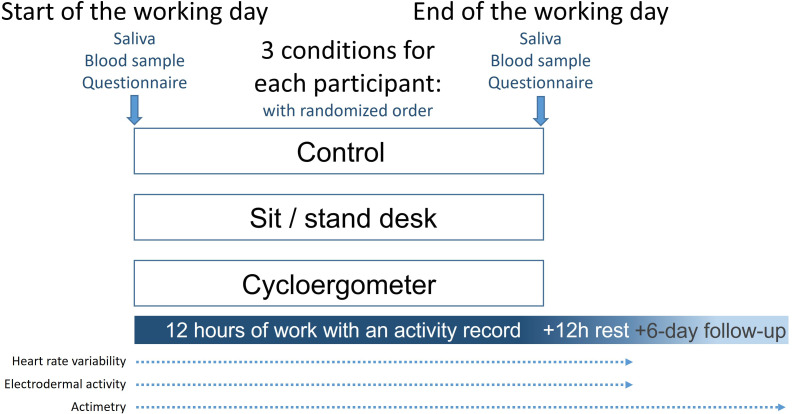

Participants will have to complete a detailed questionnaire to identify the particular events (vital emergencies, etc) as well as sleeping time and awakening time in the morning, and nutritional intakes over the day. We will carefully monitor the environment to retrieves factors that may influence the parameters measured including biomarkers of stress. At the end of each working day, a clinical research assistant with competence in nutrition will double check with the participant to verify the details of particular events (type and time), sleep (sleeping time and awakening) and nutritional intake (composition, quantity, time). The clinical research assistant will also retrieve pedalling distance and duration directly from the cycle ergometer. Participants will also answer a short questionnaire at the beginning and at the end of each measurement day. This questionnaire is composed of visual analogue scales assessing stress at home, sleep, fatigue, anxiety, mood and stress at work on a horizontal, non-calibrated line of 100 mm, ranging from very low (0) to very high (100). It is also composed of lifestyle variables related to coffee and tea consumption and physical activity. They will also answer a long questionnaire, once at the inclusion, composed of sociodemographic variables, lifestyle habits, visual analogue scales (sleep quality, family support, burnout, job control, job demand, hierarchy support, colleagues support and effort reward imbalance), clinical measurements (height, weight) and validated questionnaire (Recent Physical Activity Questionnaire (RPAQ); Maslach Burn-out Inventory (MBI); JDCS questionnaire of Karasek; Effort-Reward Imbalance Questionnaire (ERI) of Siegrist) (figure 2).

Figure 2. Outcomes’ measurement.

Data collected

The data relating to the protocol will be collected in an electronic case report form (e-CRF). Study data will be collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at CHU de Clermont-Ferrand. Questionnaires will be completed directly on REDCap by the participant. HRV, skin conductance and actimetry will be entered by a clinical research assistant on the e-CRF. Finally, all the information collected will be transcribed into the e-CRF: sociodemographic (age, gender, marital status, number of children, education level, occupation), clinical data (family, medical and surgical history, height, weight, treatment, allergy), lifestyle (physical activity—number of hours and intensity, smoking and alcohol consumption), self-report questionnaires (RPAQ, MBI, JDCS, ERI and visual analogue scales for level of burnout, job demand, job control, social support, effort-reward imbalance, sleep quality, fatigue, occupation stress, home stress, anxiety, mood); EDA; HRV; actimetry and biological parameters.

Following an evaluation of the characteristics of the study, the sponsor did not plan to carry out any monitoring visits on this protocol. This study has been classified as ‘research involving human persons second level’ according to both the level of risk for patients and the ‘Logistic and Impact Resources’ (LIR) score. The LIR score ranges from 0 and 20 and is calculated according to the logistical complexity of the study, the impact of the results and the resources of the participating centres. This study obtained a score of 2/20 and monitoring is planned from 7/20.

Sample size calculation

The primary endpoint will be sedentary behaviour expressed by standing/active time at work. Considering data from a pilot study conducted in our institution, number of minutes per day standing/active in control condition can be expected around 30 min, for a standard-deviation at 45 min. To highlight at least 50% relative difference (ie, absolute difference of 30 min: 30 min vs 60 min) between intervention (sit-and-stand desk and cycle ergometer) and control (usual working day) conditions, 27 participants are needed for a two-sided type I error at 0.017 (correction for multiple comparisons), a 80% statistical power and an intraindividual correlation coefficient equals 0.5 (cross-over design). It is proposed to include 36 participants for lost to follow-up and to have a satisfactory statistical power for secondary endpoints.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses will be performed using Stata software (V.15, StataCorp, College Station). A two-sided p value of less than 0.05 will be considered for statistical significance of all analyses. Categorical data will be described by frequencies and percentages whereas continuous data will be described by means and SD or medians and IQR, according to statistical distribution. The normality will be assessed using Shapiro-Wilk test. The primary analysis will be conducted using random effects model for cross-over designs. The following fixed effects will be considered: group conditions, period order, sequence and carry-over, in addition to participant as random effect and occupation (stratification variable) as covariate. The normality of residuals from these models will be analysed using Shapiro-Wilk test. If appropriate, a logarithmic transformation will be applied to achieve the normality of the dependent variable. The results will be expressed using effect size and 95% CI. The primary analysis will be conducted in the intention-to-treat population being all participants except those who withdraw consent for data use. Missing data will be replaced as suggested in 10.5. Then, a per-protocol analysis, including only participants who will follow the three conditions and without missing data for the primary endpoint, will be also carried out.

Then, the analysis of the primary outcome will be completed by multivariable analysis using a linear mixed model considering covariates determined according to univariate results and to clinical relevance. The results will be expressed using effect sizes and 95% CIs. The comparisons between conditions will be performed as aforementioned for continuous secondary endpoints (such as mental, physical and social health, measured with questionnaires and biomarkers of stress, blood glucose levels, insulinemia, DHEA-S, cortisol). The factors influencing the benefits of the intervention (sociodemographic and lifestyle, personality and perception of work) will be explored with same statistical approaches.

Missing data on the primary outcome measure would be negligible. However, a sensitivity analysis will be performed to describe missing data and to determine their statistical nature (random or not). Accordingly, the most appropriate missing data imputation approach will be proposed: last observation carried forward, multiple imputation or best–worst case.

Data availability statement

After contacting the corresponding author and signing a data sharing agreement, investigators will make available the documents and personal data strictly necessary in accordance with laws and regulations (Articles L.1121–3 and R.5121–13 of the French Code of Public Health).

Ethics and dissemination

The study protocol has been approved by the Ethics Committee Sud-Est I, University Hospital, Saint-Etienne, France. The study is registered in ClinicalTrials.gov after the French Ethics Committee’s approval. All patients will be seen by an investigating doctor and will be informed about the details of the study and sign written informed consent before enrolment in the study. Changes to the protocol will be considered as substantial or not by the promotor. They will, by their nature, subject to a new approval of the Ethics Committee. The results of questionnaires will be coded and managed through REDCap secure web platform with pseudonymous codification. The results will be reported according to the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials guidelines. Results from this study will be published in a peer-reviewed journal. The trial may be temporarily or permanently stopped following reasons all directives from the competent authorities requesting the temporary or permanent cessation of the trial or following the decision of the sponsor and the coordinating investigator.

Discussion

Sedentary lifestyles increased over time due to the growing reliance on motorised transportation and the widespread use of screens for work, education and leisure activities.7 Results between two cross-sectional population-based studies in France showed an increase of 27% of the prevalence of adults reporting three or more hours of daily leisure screen time in 10 years.52 Thus, sedentary behaviour is now one of the greatest public health problems.1 Due to our predominantly sedentary behaviour at work, it becomes imperative to regard it as an occupational risk.1 Studies indicate that engaging in prolonged sedentary behaviour is linked to various negative health consequences, including all-cause mortality, CVD, cancer or type-2 diabetes, irrespective of physical activity.4 14 53 54

Some professions accumulate occupational stress risk factors, in particular professions subjected to significant stressful situations. The EMDs and the firefighters responsible for managing emergency calls are mostly in a seated position in front of a desk, and they are also particularly exposed to stress due to the specific characteristics of their work environment (dealing with vital emergencies, high workload, helping people in distress).23,25 Considering this element, it seems essential to use objective measurements of stress in the context of sedentary behaviour to establish effective strategies for stress management. This protocol seems particularly interesting to study if the reduction of occupational sedentary behaviour in a real work situation has an impact on health and in particular on biomarkers of stress.

Potential limitations

This study is a preliminary study, aiming to determine, on a limited number of staff, the impact of tools that can reduce sedentary behaviour in a population frequently subjected to stressful events. Although the sample size is limited, we will work on groups of equivalent sizes determined by calculating the number of subjects necessary to draw conclusions. We will follow participants only 1 day per condition (short term). Indeed, it seemed complicated to impose on the participants to work a full week under the experimental conditions without having first assessed the short-term benefits/feelings. The modification of office equipment could also involve several biases: (1) equipment unsuited to needs or not corresponding to professional constraints inducing non-use and therefore no reduction in sedentary behaviour; (2) novelty effect linked to the availability of this new equipment, which could induce an increase in their use. In order to mitigate this risk, we will make the office available upstream, so that the staff can familiarise themselves and can be adapted to their needs. Moreover, a design with parallel arms, requiring a larger number of subjects, could be considered in the second instance, depending on the results of this first study. Another limitation may be the use of self-reported questionnaires, which introduces a potential bias of self-evaluation. To reduce this risk, we will use short questionnaires using visual analogue scales, which should also limit the frequency of missing data. In accordance with our preventive missions in occupational health, we chose to conduct the study in one of the most sedentary caregiver populations, which could be a selection bias. Moreover, this study is monocentric, precluding the generalisability of our results.

Footnotes

Funding: This research was funded by the Preventive and Occupational medicine (CHU Clermont-Ferrand), the Occupational Health Institute (Université Clermont-Auvergne) and by the LAPSCO–UMR UCA-CNRS 6024. This study is in the scope of the 'Nutrition and Mobility' research theme of the Clermont-Ferrand Hospital Center.

Prepublication history for this paper is available online. To view these files, please visit the journal online (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-080177).

Patient consent for publication: Consent obtained directly from patients.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer-reviewed.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Contributor Information

Maëlys Clinchamps, Email: mclinchamps@chu-clermontferrand.fr.

Jean-Baptiste Bouillon-Minois, Email: jbb.bouillon@gmail.com.

Marion Trousselard, Email: marion.trousselard@gmail.com.

Jeannot Schmidt, Email: jschmidt@chu-clermontferrand.fr.

Daniel Pic, Email: dpic@chu-clermontferrand.fr.

Thierry Taillandier, Email: t_taillandier@sdis63.fr.

Martial Mermillod, Email: martial.mermillod@univ-grenoble-alpes.fr.

Bruno Pereira, Email: bpereira@chu-clermontferrand.fr.

Frédéric Dutheil, Email: fdutheil@chu-clermontferrand.fr.

References

- 1.López-Valenciano A, Mayo X, Liguori G, et al. Changes in sedentary behaviour in European Union adults between 2002 and 2017. BMC Public Health. 2020;20 doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09293-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.SBR N Letter to the Editor: Standardized use of the terms ‘sedentary’ and ‘sedentary behaviours.’. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2012;37:540–2. doi: 10.1139/h2012-024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thivel D, Tremblay A, Genin PM, et al. Physical Activity, Inactivity, and Sedentary Behaviors: Definitions and Implications in Occupational Health. Front Public Health. 2018;6 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saidj M, Menai M, Charreire H, et al. Descriptive study of sedentary behaviours in 35,444 French working adults: cross-sectional findings from the ACTI-Cités study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15 doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1711-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parry S, Straker L. The contribution of office work to sedentary behaviour associated risk. BMC Public Health. 2013;13 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dutheil F, Duclos M, Esquirol Y. Editorial: Sedentary Behaviors at Work. Front Public Health. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dutheil F, Ferrières J, Esquirol Y. Occupational sedentary behaviors and physical activity at work. Presse Med. 2017;46:703–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park JH, Moon JH, Kim HJ, et al. Sedentary Lifestyle: Overview of Updated Evidence of Potential Health Risks. Korean J Fam Med. 2020;41:365–73. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.20.0165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chau JY, Grunseit A, Midthjell K, et al. Sedentary behaviour and risk of mortality from all-causes and cardiometabolic diseases in adults: evidence from the HUNT3 population cohort. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:737–42. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petersen CB, Bauman A, Grønbæk M, et al. Total sitting time and risk of myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease and all-cause mortality in a prospective cohort of Danish adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11:13. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-11-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilmot EG, Edwardson CL, Achana FA, et al. Sedentary time in adults and the association with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and death: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2012;55:2895–905. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2677-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bellettiere J, LaMonte MJ, Evenson KR, et al. Sedentary behavior and cardiovascular disease in older women: The Objective Physical Activity and Cardiovascular Health (OPACH) Study. Circulation. 2019;139:1036–46. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamilton MT, Hamilton DG, Zderic TW. Role of low energy expenditure and sitting in obesity, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes. 2007;56:2655–67. doi: 10.2337/db07-0882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmid D, Leitzmann MF. Television viewing and time spent sedentary in relation to cancer risk: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106 doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dzakpasu FQS, Carver A, Brakenridge CJ, et al. Musculoskeletal pain and sedentary behaviour in occupational and non-occupational settings: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2021;18 doi: 10.1186/s12966-021-01191-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kett AR, Sichting F. Sedentary behaviour at work increases muscle stiffness of the back: Why roller massage has potential as an active break intervention. Appl Ergon. 2020;82:102947. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2019.102947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodríguez-Gómez I, Mañas A, Losa-Reyna J, et al. Associations between sedentary time, physical activity and bone health among older people using compositional data analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang Y, Li L, Gan Y, et al. Sedentary behaviors and risk of depression: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10:26. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-0715-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang L, Cao Y, Ni S, et al. Association of Sedentary Behavior With Anxiety, Depression, and Suicide Ideation in College Students. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.566098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teychenne M, Stephens LD, Costigan SA, et al. The association between sedentary behaviour and indicators of stress: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2019;19 doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7717-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chauntry AJ, Bishop NC, Hamer M, et al. Sedentary behaviour is associated with heightened cardiovascular, inflammatory and cortisol reactivity to acute psychological stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2022;141 doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2022.105756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hadgraft NT, Winkler E, Climie RE, et al. Effects of sedentary behaviour interventions on biomarkers of cardiometabolic risk in adults: systematic review with meta-analyses. Br J Sports Med. 2021;55:144–54. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bedini S, Braun F, Weibel L, et al. Stress and salivary cortisol in emergency medical dispatchers: A randomized shifts control trial. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0177094. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodrigues S, Paiva JS, Dias D, et al. Stress among on-duty firefighters: an ambulatory assessment study. PeerJ. 2018;6:e5967. doi: 10.7717/peerj.5967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith EC, Holmes L, Burkle FM. Exploring the Physical and Mental Health Challenges Associated with Emergency Service Call-Taking and Dispatching: A Review of the Literature. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2019;34:619–24. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X19004990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montassier E, Labady J, Andre A, et al. The effect of work shift configurations on emergency medical dispatch center response. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2015;19:254–9. doi: 10.3109/10903127.2014.959217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rugless MJ, Taylor DM. Sick leave in the emergency department: staff attitudes and the impact of job designation and psychosocial work conditions. Emerg Med Australas. 2011;23:39–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2010.01372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pereira MA, Mullane SL, Toledo MJL, et al. Efficacy of the ‘Stand and Move at Work’ multicomponent workplace intervention to reduce sedentary time and improve cardiometabolic risk: a group randomized clinical trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17:133. doi: 10.1186/s12966-020-01033-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pressler A, Knebel U, Esch S, et al. An internet-delivered exercise intervention for workplace health promotion in overweight sedentary employees: A randomized trial. Prev Med. 2010;51:234–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wipfli B, Wild S, Donovan C, et al. Sedentary Work and Physiological Markers of Health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:3230. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18063230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunstan DW, Kingwell BA, Larsen R, et al. Breaking up prolonged sitting reduces postprandial glucose and insulin responses. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:976–83. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Healy GN, Dunstan DW, Salmon J, et al. Breaks in sedentary time: beneficial associations with metabolic risk. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:661–6. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peddie MC, Bone JL, Rehrer NJ, et al. Breaking prolonged sitting reduces postprandial glycemia in healthy, normal-weight adults: a randomized crossover trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98:358–66. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.051763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thosar SS, Bielko SL, Mather KJ, et al. Effect of prolonged sitting and breaks in sitting time on endothelial function. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47:843–9. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dupont F, Léger P-M, Begon M, et al. Health and productivity at work: which active workstation for which benefits: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med. 2019;76:281–94. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2018-105397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manini TM, Carr LJ, King AC, et al. Interventions to reduce sedentary behavior. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47:1306–10. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nooijen CFJ, Kallings LV, Blom V, et al. Common Perceived Barriers and Facilitators for Reducing Sedentary Behaviour among Office Workers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:792. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15040792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dempsey PC, Larsen RN, Sethi P, et al. Benefits for Type 2 Diabetes of Interrupting Prolonged Sitting With Brief Bouts of Light Walking or Simple Resistance Activities. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:964–72. doi: 10.2337/dc15-2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noushad S, Ahmed S, Ansari B, et al. Physiological biomarkers of chronic stress: A systematic review. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2021;15:46–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim HG, Cheon EJ, Bai DS, et al. Stress and Heart Rate Variability: A Meta-Analysis and Review of the Literature. Psychiatry Investig. 2018;15:235–45. doi: 10.30773/pi.2017.08.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bouillon-Minois J-B, Trousselard M, Thivel D, et al. Leptin as a Biomarker of Stress: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2021;13:3350. doi: 10.3390/nu13103350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bouillon-Minois J-B, Trousselard M, Thivel D, et al. Ghrelin as a Biomarker of Stress: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2021;13:784. doi: 10.3390/nu13030784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karasek R, Brisson C, Kawakami N, et al. The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): an instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. J Occup Health Psychol. 1998;3:322–55. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.3.4.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Niedhammer I, Siegrist J, Landre MF, et al. Psychometric properties of the French version of the Effort-Reward Imbalance model. Rev Epidém Santé Publ. 2000;48:419–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mikkelsen M-LK, Berg-Beckhoff G, Frederiksen P, et al. Estimating physical activity and sedentary behaviour in a free-living environment: A comparative study between Fitbit Charge 2 and Actigraph GT3X. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0234426. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wijndaele K, Westgate K, Stephens SK, et al. Utilization and Harmonization of Adult Accelerometry Data: Review and Expert Consensus. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47:2129–39. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Electrophysiology TFotESoCtNASoP Heart Rate Variability. Circulation. 1996;93:1043–65. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.93.5.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boudet G, Walther G, Courteix D, et al. Paradoxical dissociation between heart rate and heart rate variability following different modalities of exercise in individuals with metabolic syndrome: The RESOLVE study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2017;24:281–96. doi: 10.1177/2047487316679523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klimek A, Mannheim I, Schouten G, et al. Wearables measuring electrodermal activity to assess perceived stress in care: a scoping review. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2023;2023:1–11. doi: 10.1017/neu.2023.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kapp D, Schaaff K, Ottenbacher J, et al. Evaluation of environmental effects on the measurement of electrodermal activity under real-life conditions. 2014:S255–8.

- 51.Rahma ON, Putra AP, Rahmatillah A, et al. Electrodermal Activity for Measuring Cognitive and Emotional Stress Level. J Med Signals Sens. 2022;12:155–62. doi: 10.4103/jmss.JMSS_78_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Verdot C, Salanave B, Aubert S, et al. Prevalence of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviors in the French Population: Results and Evolution between Two Cross-Sectional Population-Based Studies, 2006 and 2016. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:2164. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19042164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Sedentary Behaviour, Physical Activity and Life Satisfaction, Happiness and Perceived Health Status in University Students from 24 Countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2084. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16122084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Biswas A, Oh PI, Faulkner GE, et al. Sedentary time and its association with risk for disease incidence, mortality, and hospitalization in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:123–32. doi: 10.7326/M14-1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dutheil F, Boudet G, Perrier C, et al. JOBSTRESS study: comparison of heart rate variability in emergency physicians working a 24-hour shift or a 14-hour night shift--a randomized trial. Int J Cardiol. 2012;158:322–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.04.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dutheil F, Chambres P, Hufnagel C, et al. ‘Do Well B.’: Design Of WELL Being monitoring systems. A study protocol for the application in autism. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007716. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dion G, Tessier R. Validation de la traduction de l’Inventaire d’épuisement professionnel de Maslach et Jackson. [Validation of a French translation of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI)] Can J Behav Sci Rev Can Des Sci Du Comport. 1994;26:210–27. doi: 10.1037/0008-400X.26.2.210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Niedhammer I, Ganem V, Gendrey L, et al. Propriétés psychométriques de la version française des échelles de la demande psychologique, de la latitude décisionnelle et du soutien social du « Job Content Questionnaire » de Karasek : résultats de l’enquête nationale SUMER. Santé Publique. 2006;Vol. 18:413–27. doi: 10.3917/spub.063.0413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dutheil F, Pereira B, Moustafa F, et al. At-risk and intervention thresholds of occupational stress using a visual analogue scale. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0178948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hellhammer DH, Wüst S, Kudielka BM. Salivary cortisol as a biomarker in stress research. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:163–71. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dutheil F, de Saint Vincent S, Pereira B, et al. DHEA as a Biomarker of Stress: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:688367. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.688367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carniel BP, da Rocha NS. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and inflammatory markers: Perspectives for the management of depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;108:110151. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miller AH, Maletic V, Raison CL. Inflammation and its discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:732–41. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morales-Medina JC, Dumont Y, Quirion R. A possible role of neuropeptide Y in depression and stress. Brain Res. 2010;1314:194–205. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.09.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]