Abstract

Introduction

Mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC)-based cell therapy is a promising approach for various inflammatory disorders based on their immunosuppressive capacity. Osteopontin (OPN) regulates several cellular functions including tissue repair, bone metabolism and immune reaction. However, the biological function of OPN in regulating the immunosuppressive capacity of MSCs remains elusive.

Objectives

This study aims to highlight the underlying mechanism of the proinflammatory cytokines affect the therapeutic ability of MSCs through OPN.

Methods

MSCs in response to the proinflammatory cytokines were collected to determine the expression profile of OPN. In vitro T-cell proliferation assays and gene editing were performed to check the role and mechanisms of OPN in regulating the immunosuppressive capacity of MSCs. Inflammatory disease mouse models were established to evaluate the effect of OPN on improving MSC-based immunotherapy.

Results

We observed that OPN, including its two isoforms iOPN and sOPN, was downregulated in MSCs upon proinflammatory cytokine stimulation. Interestingly, iOPN, but not sOPN, greatly enhanced the immunosuppressive activity of MSCs on T-cell proliferation and thus alleviated the inflammatory pathologies of hepatitis and colitis. Mechanistically, iOPN interacted with STAT1 and mediated its deubiquitination, thereby inducing the master immunosuppressive mediator inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in MSCs. In addition, iOPN expression was directly downregulated by activated STAT1, which formed a negative feedback loop to restrain MSC immunosuppressive capacity.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrated that iOPN expression modulation in MSCs is a novel strategy to improve MSC-based immunotherapy.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13287-024-03979-8.

Keywords: Mesenchymal stem cells, Intracellular osteopontin, Immunosuppression, Inflammation, STAT1

Introduction

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are adult progenitor cells that have attracted much attention for their ability to regulate inflammatory processes [1, 2]. Studies have shown that proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interferon (IFN)-γ and interleukin (IL)-1, can activate MSCs, allowing them to exhibit immunosuppressive functions and thus alleviating inflammation [1, 3]. Our previous work demonstrated that treatment with MSCs inhibited the infiltration, activation and proliferation of CD4+ T cells by inducing a subset of regulatory dendritic cells to alleviate liver damage [4]. Moreover, MSCs also act directly on T cells by recruiting activated T cells and inhibiting the activation and proliferation of them through the production of nitric oxide (NO), indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, prostaglandin E2, transforming growth factor-β and heme oxygenase to alleviate the severity of inflammatory diseases [5, 6].

Proinflammatory cytokines activate MSCs, which allows them to exert their immunomodulatory functions. However, in this process, these proinflammatory cytokines also have adverse effects on MSCs. For example, Shi and colleagues observed that the expression of Mir-155 in MSCs was upregulated after stimulation by inflammatory factors. This elevated Mir-155 level was found to diminish the immunosuppressive capabilities of MSCs [7]. Our previous studies also showed that inflammatory factors promoted the generation of autophagy in MSCs, and inhibition of autophagy can improve the immunosuppressive function of MSCs and the therapeutic effect of MSCs on experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis model animals [8]. In addition, IFN-γ plus TNF-α could promote the apoptosis of MSCs, which inhibited their therapeutic effects on bone repair [9]. Thus, a better understanding of the mechanisms by which the inflammatory microenvironment regulates the immunosuppressive capacity and survival of MSCs is needed to guide the future clinical use of MSCs.

Osteopontin (OPN), also known as early T lymphocyte activation 1 protein, is a phosphorylated glycoprotein that exists in bone, kidney, blood vessels and other tissues [10]. In early studies, OPN was considered a secretory protein (sOPN), mainly serving as a cytokine in the matrix that had diverse biological functions [11]. Recent studies have found that OPN can also be maintained inside the cytosol or the nucleus, and this form is defined as intracellular OPN (iOPN) [12]. These two forms are transcribed by the same RNA segment, but selective translation exists in the translation process. Both sOPN and iOPN play important roles in cell adhesion, migration, immunity and differentiation, but the regulatory mechanisms are different. sOPN can recognize its receptors (mainly integrins V3 and CD44) and activate downstream signaling, such as NF-κB and PI3K/AKT, while iOPN is usually recruited near intracellular receptors, such as TLR9, and interacts with the adaptor molecule MyD88 as its effector, promoting the transcription of downstream genes and the production of inflammatory cytokines in immune-mediated diseases [13]. In MSCs, OPN was found to have effects on differentiation [14]. In view of the different effects of sOPN and iOPN on immunity and MSCs, it is necessary to study the regulatory effect of OPN, especially its different forms, on the immunosuppressive function of MSCs.

In the present study, we found that OPN was downregulated by activated STAT1 in MSCs upon proinflammatory cytokine stimulation. We further identified that iOPN, but not sOPN, was essential for the immunosuppressive activity of MSCs by promoting STAT1-induced expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). Accordingly, overexpression of iOPN greatly promoted the therapeutic efficacy of MSCs in alleviating inflammatory diseases. Therefore, our study demonstrates a novel mechanism in restraining the immunosuppressive capacity of MSCs through the inhibition of iOPN under inflammatory conditions.

Materials and methods

Reagents and mice

Recombinant murine IFN-γ (CAT# 315-05) and TNF-α (CAT# 315-01A) were purchased from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, USA). Antibodies against GAPDH (CAT# 2118, RRID: AB_561053), NF-κB p65 (CAT# 8242, RRID:AB_10859369), phospho-NF-κB p65 (CAT# 3033, RRID:AB_331284), STAT1 (CAT# 14994, RRID:AB_2737027), phospho-STAT1 (Tyr701) (CAT# 7649, RRID:AB_10950970), IκBα (CAT# 4814, RRID:AB_390781), phospho-IκBα (CAT# 2118) and ubiquitin (CAT# 3936, RRID: RRID:AB_331292) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, Massachusetts, USA). Antibodies against iNOS (CAT# ab178945, RRID:AB_2861417) and recombinant mouse osteopontin protein (CAT# ab281820) were purchased from Abcam (San Francisco, USA). Antibodies against OPN (CAT# AF808, RRID:AB_2194992) and OPN neutralizing antibodies (CAT# 441-OP) were purchased from R&D Systems (Minnesota, USA). Antibodies against c-Myc (CAT# sc-40, RRID:AB_627268) and c-Myc-HRP (CAT# sc-40-HRP) were from Santa Cruz (California, USA). Antibodies against HA (CAT# 2013819) were purchased from Roche (Natley, New Jersey, USA). Antibodies for Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-goat IgG (CAT# A-11055, RRID:AB_2534102) and Alexa Fluor 647 goat anti-rabbit IgG (CAT# A27040, RRID:AB_2536101) were from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). L-NMMA (CAT# S7920) and fludarabine (CAT# S1491) were purchased from Selleckchem (Houston, USA). Antibodies against Flag (A8592, RRID:AB_439702), ConA (CAT# L7647) and Griess (CAT# 23479) reagents were purchased from Sigma‒Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Female WT and OPN−/− C57BL/6 mice (8–10 weeks old) were purchased from the Shanghai Laboratory Animal Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in the vivarium of Shanghai Institute of Nutrition and Health, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Sample sizes of all experiments were predetermined by calculations derived from our experience. No sample was excluded from the analyses. Animals were not randomly assigned during collection, but the strain, sex, and age of the mice were the same, and the data analysis was single masked. Investigators were not blinded to the group allocation during the experiment and outcome assessment. The number of replicates were indicated in each figure legend. All mice were housed in SPF-rated cages.

Cells

Murine bone marrow MSCs were isolated as previously described [8]. Briefly, murine MSCs were generated from the bone cavity of femurs and tibias of 3- to 4-week-old C57BL/6 mice. The cells were cultured in DMEM-low glucose containing 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine and 1% penicillin‒streptomycin (all from Life Technologies, Carlsbad, California, USA). A single-cell suspension of bone marrow cells was seeded in 100 mm culture dishes, nonadherent cells were removed after 24 h, and the medium was replenished every 2 days. Cells were used at the 9–16th passages. ‘Stemness’ of murine MSCs was determined by their expression of specific cell surface markers and by their capability to differentiate into adipocytes, osteoblasts, and chondrocytes. The MSCs used in each experiment were paired and at the same passage. 293T cells were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, USA).

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

TRIzol (Life Technologies) was added to mice tissues or MSCs for extraction of RNA. The collected tissues should be homogenized with homogenizer. Samples can be stored at − 80 °C before extraction. Total RNA extracted with TRIzol was tested by NanoDrop (Thermo Scientific) for the assessment of RNA quality and quantity. And then RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA with a reverse transcription kit from TaKaRa (Tokyo, Japan). Quantitative PCR was performed using FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master Kit (Roche) on an ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The reaction protocol used was 95 °C 5 min, 35 cycles with 95 °C 15 s, 60 °C 60 s, and 72 °C 5 min. β-actin, which was recommended as the reference gene in both software analysis and literature review, was used as an internal control to normalize for differences in the amount of total RNA in each sample. Primers are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Quantitative real-time PCR primers

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| β-actin forward | 5′-TGTCCACCTTCCAGCAGATGT-3′ |

| β-actin reverse | 5′-AGCTCAGTAACAGT-CCGCCTAGA-3′ |

| OPN forward | 5′-AGCAAGAAACTCTTCCAAGCAA-3′ |

| OPN reverse | 5′-GTGAGATTCGTCAGATTCATCCG-3′ |

| iNos forward | 5′-TGGAGCGAGTTGTGGATTGT-3′ |

| iNos reverse | 5′-GGGTCGTAATGTCCAGGAAGTA-3′ |

| IL-4 forward | 5′-GGTCTCAACCCCCAGCTAGT-3′ |

| IL-4 reverse | 5′-GCCGATGATCTCTCTCAAGTGAT-3′ |

| TNF-α forward | 5′-GGTCTGGGCCATAGAACTGA-3′ |

| TNF-α reverse | 5′-CAGCCTCTTCTCATTCCTGC-3′ |

| IFN-γ forward | 5′-TGAGCTCATTGAATGCTTGG-3′ |

| IFN-γ reverse | 5′-AGGCCATCAGCAACAACATA-3′ |

| IL-17a forward | 5′-CAAACACTGAGGCCAAGGAC-3′ |

| IL-17a reverse | 5′-CGTGGAACGGTTGAGGTAGTC-3′ |

| Sox9 forward | 5′-GAGCCGGATCTGAAGATGGA-3′ |

| Sox9 reverse | 5′-GCTTGACGTGTGGCTTGTTC-3′ |

| Col2 forward | 5′-ACCTTGGACGCCATGAAA-3′ |

| Col2 reverse | 5′-GTGGACAGTAGACGGAGGAA-3′ |

| Aggrecan forward | 5′-CCTGCTACTTCATCGACCCC-3′ |

| Aggrecan reverse | 5′-AGATGCTGTTGACTCGAACCT-3′ |

| T-bet forward | 5′-AGCAAGGACGGCGAATGTT-3′ |

| T-bet reverse | 5′-GGGTGGACATATAAGCGGTTC-3′ |

| hnRNP-A/B forward | 5′-CAGGGTAGTTGAGCCAAAACG-3′ |

| hnRNP-A/B reverse | 5′-TTCCAGACTGCCTATCGGTAA-3′ |

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation

Cells were harvested and lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Beyotime, Haimen, China) containing phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) (Beyotime) for 30 min on ice. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 30 min. The protein concentration of the supernatant fraction was determined by the Bradford assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, New Hampshire, USA). Protein samples were diluted in 4 × sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) loading buffer (TaKaRa), heated to 100 °C for 5 min and fractionated in a 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were electroblotted onto polyvinylidene fluoride and incubated for 1 h in 5% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or nonfat dry milk dissolved in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (PBST) at room temperature. The blotted membranes were incubated with primary antibodies diluted 1000-fold overnight at 4 °C, extensively washed in PBST, incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, USA) diluted 5000-fold for 1 h at room temperature, and washed again with PBST. The blotting membranes were developed with chemiluminescent reagents (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer. For immunoprecipitation, the indicated antibody was added to the cell lysates and incubated at 4 °C on a shaker overnight after preclear, followed by pulling down the desired protein with Protein A/G magnetic beads (HY-K0202, Med ChemExpress, New Jersey, USA). The precipitated proteins were boiled with SDS loading buffer and assessed by immunoblotting.

Overexpression and siRNA transfection

Full-length mouse iOPN cDNA was synthesized by Genscript (Nanjing, China). These cDNAs were subcloned into pcDNA3.1 vectors containing an N-terminal Myc epitope tag. Murine MSCs or 293T cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1 or pcDNA3.1 containing iOPN by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies). Full-length mouse STAT1-pcDNA3.0 containing Flag was also synthesized. siRNA oligonucleotides were purchased from GenePharma (Shanghai, China) and transfected into mouse MSCs with Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent (13,778, Invitrogen, California, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The effects of transfection were tested by immunoblotting or quantitative real-time PCR analysis.

Immunofluorescence

MSCs were seeded into 12-well plates with lysine-coated slides and stimulated with TNF-α and IFN-γ for 24 h. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 (T9284, Sigma‒Aldrich, Missouri, USA), blocked with 2% BSA (sc-2323, Santa Cruz, USA), and incubated with anti-OPN antibody overnight. Cells were washed with PBST and incubated with fluorescent secondary antibody and DAPI. For the OPN and STAT1 colocalization assay, murine MSCs and 293T cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with Triton X-100, followed by blocking with bovine serum albumin (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) at room temperature for 1 h and incubation with specific primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. After washing with PBS 3 times, secondary antibodies labeled with different fluorescence were added and incubated for 2 h. Confocal microscopy (ZEISS Cell Observer) was used to examine the slides, and images were obtained.

In vitro T-cell proliferation assay

Murine MSCs with different treatments were irradiated with 30 Gy from a 137 Cs source as previously described [8] to inactivate MSCs by inhibiting their proliferation while preserving their immunosuppressive capacity and then seeded into 48-well plates. Freshly isolated splenocytes (4 × 105 cells/well) from C57/BL6 mice were labeled with 5 μM carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA), cocultured with murine MSCs for 3 days in the presence of mouse anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies (eBiosciences, San Diego, CA, USA), and then collected for flow cytometric analysis on a fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) Calibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Griess assay

Fifty microliters of culture supernatant fraction of different treated murine MSCs and standards were added to a flat bottomed 96-well plate, and then 50 μL of Griess reagent (Sigma) was added. The absorbance at 540 nm was read after incubation for 15 min in the dark at room temperature, and the NO concentrations were calculated.

ConA-induced inflammatory liver injury in mice

Male C57BL/6 mice (8–10 weeks old) were intravenously injected with ConA in PBS at 20 mg/kg to induce inflammatory liver injury. Murine Vector-MSCs (control group) and iOPN-MSCs (1 × 106) were intravenously administered to mice immediately after ConA injection. Isoflurane was used as an inhaled anesthetic at a concentration of 2–3% to induce mice anesthesia 8 h after ConA injection. Blood was sampled from mice eyes. Mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation. Mice serum, spleens and liver tissues were sampled. Liver histological sections fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Liver MNCs were purified by a Percoll gradient, while spleen MNCs were purified by a Ficoll gradient, and both MNCs were stained with anti-CD4, CD25 and CD69 (eBiosciences) for 30 min at 4 °C in staining buffer and then analyzed by flow cytometry on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer. For T-cell proliferation analysis in vivo, 1 mg BrdU (Cat. No. 559619, BD Biosciences) in 100 μL PBS was intraperitoneally injected into mice. The mice were euthanized 2 h after BrdU administration, and immune cell suspensions from livers or spleens were prepared for flow cytometric analysis.

Inflammatory bowel disease in mice

Male C57BL/6 mice (8–10 weeks old) were given 2.5% (W/V) DSS drinking water, followed by fresh DSS drinking water on Days 3 and 5. Intestinal damage in mice was observed on Days 7 and 9. Murine Vector-MSCs (control group) and iOPN-MSCs (1 × 106) were intravenously administered to mice every 2 days. Mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation, and colon tissues and MLNs were isolated on Day 10. Colon histological sections fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Colon MNCs and MLNs were purified by a Percoll gradient, and both MNCs were stained with anti-CD4, LY6G and F4/80 (eBiosciences) for 30 min at 4 °C in staining buffer and then analyzed by flow cytometry on a FACS Calibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

TUNEL assay

Collected liver tissues were routinely embedded in OCT compound and then stored at -80 ℃. For the TUNEL assay, apoptotic cells were detected using a TUNEL Apoptosis Detection Kit (Alexa Fluor 488, Cat. No. 40307ES60, YEASEN Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Induction and detection of murine MSC proliferation and apoptosis

Murine MSCs were treated with IFN-γ plus TNF-α (10 ng/mL) for 24 h. For proliferation analysis, the medium was removed, and the cells were treated with new FBS-free medium followed by the addition of CCK-8 solution (Dojindo Laboratories, Mashikimachi, Kamimashiki gun Kumamoto, Japan). After 2 h, BioTEK (Winooski, VT) was used to record the absorbance at 450 nm. For apoptosis analysis, cells were stained with annexin V and propidium iodide (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and then analyzed by flow cytometry.

RNA-sequencing analysis

Total RNA was extracted from TNF-α (10 ng/mL) plus IFN-γ (10 ng/mL)-stimulated or unstimulated MSCs and subjected to RNA-sequencing analysis by Shanghai Biotechnology Corporation Tech Solutions. The Affymetrix Mouse 430 2.0 chip was used in the project. Slides were scanned by GeneChip® Scanner 3000 (Cat#00-00212, Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, US) and Command Console Software 3.1 (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, US) with default settings. Raw data were normalized by MAS 5.0 algorithm, Gene Spring Software 11.0 (Agilent technologies, Santa Clara, CA, US). Significantly differentially expressed genes were acquired by setting a threshold with corrected p < 0.005 and log2 ≤ − 1.5 or log2 ≥ 1.5, and are presented as heatmaps. The correlation analysis was conducted using the R package Hmisc, employing Spearman's rank correlation coefficient. Gene correlation heatmap was plotted by the R package heatmap.

Flow cytometry

For surface marker staining, the collected cell suspensions from mouse tissues were stained with the indicated antibodies for 30 min and subjected to flow cytometry analyses. For the intracellular staining of iNOS, MSCs were fixed and permeabilized by fixation/permeabilization buffer (Cat. No. 00-5523, eBioscience) before staining. An antibody against iNOS (Cell Signaling Technology) was incubated for 30 min, and the secondary antibody labeled with fluorescence was added after washing the cells. MSCs were analyzed by flow cytometry after 30 min.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

Chromatin of MSCs (1 × 107) was prepared using the EZ-ChIP Chromating Immunoprecipitation Kit (Cat. No. 17-371, Millipore, MA, USA) according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Chromatin was immunoprecipitated using anti-p-STAT1 or respective IgGs. ChIP-enriched and input DNA were extracted by a PCR Cleanup Kit (Cat. No. AP-PCR-500G, Axygen, California, USA) and analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR, with the inputs as the internal control. Three kinds of primers for the ChIP assay were provided according to the motif as follows: Opn-2667, sense 5′-cctcctcgagttagaagagcgt-3′ and antisense 5′-cattctaactcccaagtgccacac-3′; mouse Opn-2697, sense 5′-ctgctttgcagaattgctccca-3′ and antisense 5′-cattctaactcccaagtgccacac -3′; Opn-2743, sense 5′-gctggtatgagtgtaggaagagggaa-3′ and antisense 5′-cattctaactcccaagtgccacac-3′. Regions of the OPN promoter used for the ChIP assay ranged from − 5000 bp to the TSS.

Statistical analysis

All data are shown as the mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments. Significant differences were evaluated using one-way ANOVA or the Mann–Whitney U test with GraphPad Prism (version 9.0, GraphPad Software) and Statistical Package for Social Science software (version 22.0, SPSS). Values of p less than 0.05 were considered significant. Sample sizes of all experiments were predetermined by calculations derived from our experience. Test samples were assayed in replicates. To provide measures of reproducibility, three replicates per sample of the assay was considered for our analysis.

Results

iOPN, but not sOPN, is critical for the immunosuppressive capacity of MSCs

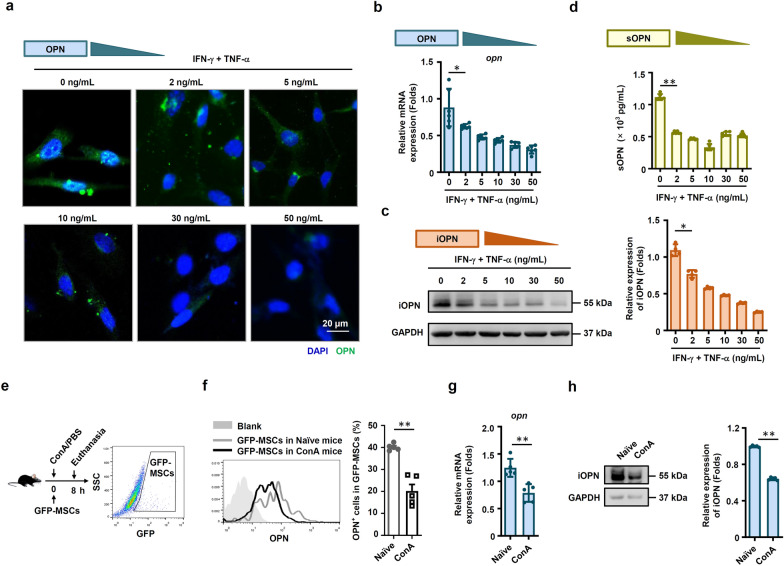

The expression of OPN was dramatically reduced in MSCs after stimulation with different doses of IFN-γ plus TNF-α (Fig. 1a, b). We further measured the expression of the two forms of OPN separately. The data also showed that the protein expression level of iOPN was decreased in MSCs treated with IFN-γ plus TNF-α in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1c). In addition, the secretion of sOPN by MSCs in the cell culture supernatant was decreased, indicating that sOPN protein expression levels were also decreased after inflammatory stimulation (Fig. 1d). We next examined whether OPN expression in MSCs was downregulated in inflammatory disease. We employed a ConA-induced liver injury mouse model, and GFP-labeled MSCs were injected into mice via the tail vein (Fig. 1e). The downregulated iOPN expression in the GFP-MSCs of liver injury mice sorted by flow cytometry was confirmed (Fig. 1e–h). Volcanic map showed that OPN was one of the genes whose expression was down-regulated after inflammatory stimulation in MSCs (Fig. S1). These data collectively suggested that the expression of OPN, including iOPN and sOPN, was dramatically downregulated in MSCs under inflammatory conditions both in vitro and in vivo.

Fig. 1.

OPN expression was downregulated in MSCs under inflammatory conditions. a MSCs were treated with TNF-α plus IFN-γ at the indicated concentration for 24 h. Images were collected by a Zeiss fluorescence microscope. Scale bar: 20 μm. b and c Murine MSCs were treated with IFN-γ plus TNF-α at the indicated concentration for 24 h, and mRNA and protein of MSCs were collected. OPN expression was determined at the mRNA and protein levels by quantitative real-time PCR and immunoblotting analysis. Full-length blots are presented in Additional file 1: Fig. 1c. d sOPN in the culture medium of MSCs treated with IFN-γ plus TNF-α at the indicated concentration for 24 h was tested by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. e–h MSCs with CFSE staining were administered intravenously to mice with ConA-induced liver damage. The mice were euthanized after 8 h, and the mononuclear cells in mouse lungs were collected. OPN expression in GFP+ mononuclear cells was evaluated by flow cytometry (f), quantitative real-time PCR (g) and immunoblotting analysis (h) (naïve: n = 5, ConA: n = 5). Full-length blots are presented in Additional file 1: Fig. 1h. The results are representative of three to six independent experiments. Values are shown as the mean ± SEM and statistical significance is indicated as *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01

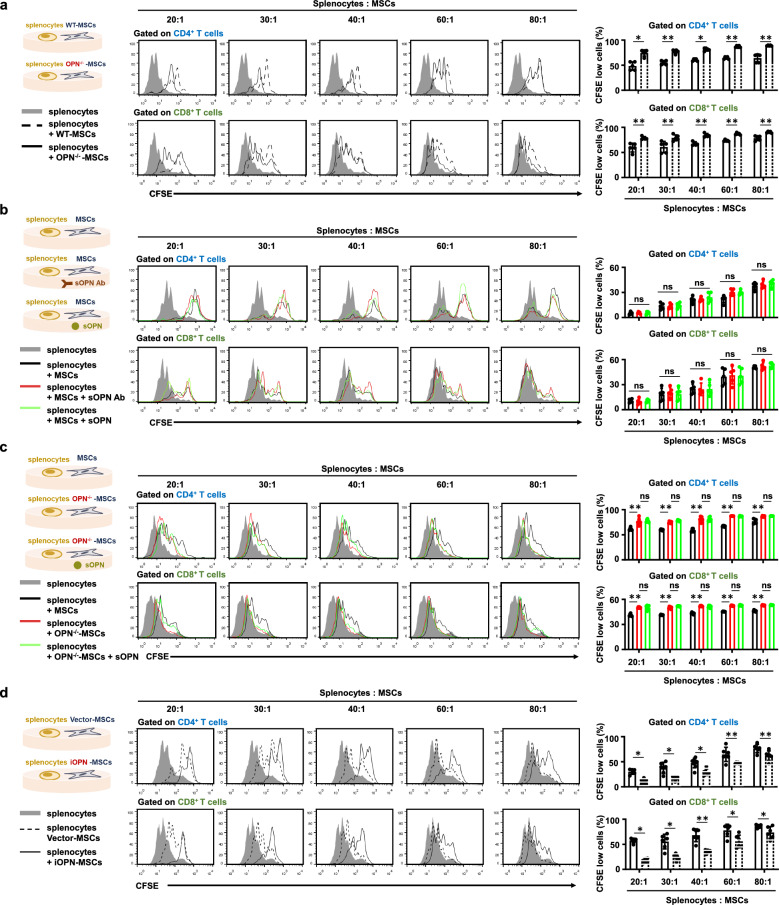

We then examined whether OPN could affect the immunosuppressive capacity of MSCs. MSCs from wild-type (WT) mice were isolated and cultured as previously described [8]. OPN-knockout (OPN−/−) was applied to further investigate the function of OPN in MSCs. The knockout efficiency in OPN−/−-MSCs was confirmed (Fig. S2a). We found that OPN deficiency had no effect on the surface marker expression of MSCs (Fig. S2b). However, OPN-deficiency promoted adipogenic differentiation and inhibited osteogenic differentiation of MSCs as previously reported [14] (Fig. S2c). The chondrogenesis ability was also weakened in OPN−/−-MSCs compared with WT-MSCs (Fig. S2c). Next, to better simulate the complex and chaotic immune microenvironment in the body, WT-MSCs and OPN−/−-MSCs were cocultured with splenocytes to evaluate the difference in their immunosuppressive capacity. Interestingly, WT-MSCs suppressed T-cell division more efficiently than OPN−/−-MSCs in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2a). However, adding a specific monoclonal antibody neutralized sOPN or exogenous OPN in the culture medium of WT- MSCs, and T-cell proliferation was not affected (Fig. 2b). The results also revealed that T-cell proliferation was not affected when OPN−/−-MSCs were supplemented with sOPN (Fig. 2c). In addition, the neutralizing antibody or exogenous OPN had no effects on MSC proliferation and apoptosis with proinflammatory cytokine stimulation (Fig. S3a, b). The addition of exogenous OPN to the culture supernatant did not reverse the impaired proliferation and apoptosis of OPN−/−-MSCs (Fig. S3c, d). These results suggested that sOPN did not affect the immunosuppression, proliferation and apoptosis of MSCs.

Fig. 2.

iOPN in MSCs, but not sOPN, inhibited T-cell proliferation. a Irradiated MSCs or OPN−/−-MSCs were cocultured with CFSE-labeled splenocytes for 3 days in the presence of anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies at the indicated ratios. CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells were collected for proliferation analysis by flow cytometry at the end of coculture. The percentages of proliferating T cells are shown. b MSCs treated with neutralizing antibody against OPN or replenished with sOPN for 24 h. Cells were irradiated and then cocultured with CFSE-labeled splenocytes for 3 days in the presence of anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies at the indicated ratios. CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells were collected for proliferation analysis by flow cytometry at the end of coculture. c Recombinational sOPN was added to the medium of OPN−/−-MSCs for 24 h. WT-MSCs and OPN−/−-MSCs were irradiated and then cocultured with CFSE-labeled splenocytes for 3 days in the presence of anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies at the indicated ratios. CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells were collected for proliferation analysis by flow cytometry at the end of coculture, and the percentages of proliferating T cells are shown. d Irradiated Vector-MSCs or iOPN-MSCs were cocultured with CFSE-labeled splenocytes for 3 days in the presence of anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies at the indicated ratios. CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells were collected for proliferation analysis by flow cytometry at the end of coculture, and the percentages of proliferating T cells are shown. The results are representative of three to six independent experiments. Values are shown as the mean ± SEM and statistical significance is indicated as *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. ns = no significance

In contrast, iOPN overexpressing MSCs dramatically enhanced their immunosuppressive effects on T-cell proliferation (Figs. S3e and 2d). It was also found that iOPN overexpression promoted proliferation and inhibited apoptosis of MSCs (Fig. S3f, g). These results suggested that the decreased immunosuppression of OPN−/−-MSCs is dependent on the lack of iOPN but not sOPN.

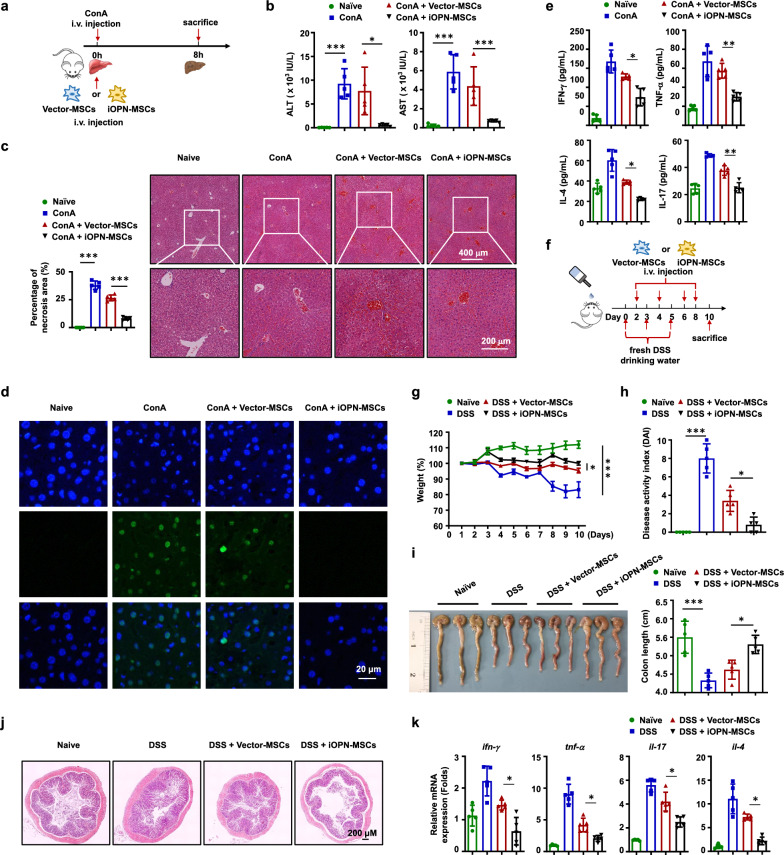

iOPN promotes MSC-mediated immunosuppression in inflammatory diseases

Next, we investigated whether iOPN overexpression enhanced the immunosuppressive capacity of MSCs in vivo. ConA-induced liver injury and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are well-established murine models of immune-mediated inflammatory disease in humans, which are considered more eligible for the study of pathophysiology of human hepatitis and colitis. Both models are common animal models for studying the effect of MSCs in treating inflammatory diseases [15, 16]. iOPN-MSCs were intravenously administered to treat ConA-induced acute liver damage (Fig. 3a). As expected, compared to Vector-MSCs, iOPN-MSCs significantly alleviated inflammation-induced liver damage, exhibiting a dramatic reduction in serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels (Fig. 3b). Histological examination showed less infiltration of mononuclear cells and centrilobular necrosis in the liver sections of iOPN-MSC-treated mice than in those treated with Vector-MSCs (Fig. 3c). Moreover, there was less hepatocyte apoptosis in the livers of ConA-induced liver damage mice treated with iOPN-MSC (Fig. 3d). Remarkably, the serum protein levels of key proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-17, were significantly reduced in iOPN-MSC-treated mice with liver damage compared with Vector-MSC-treated mice (Fig. 3e). Homoplastically, we induced another inflammatory disease mouse model, IBD, and treated the mice with Vector-MSCs and iOPN-MSCs (Fig. 3f). The results showed that iOPN-MSCs significantly decreased the weight loss (Fig. 3g) and the disease activity index (DAI) (Fig. 3h) and increased the length of colon (Fig. 3i) in IBD model mice compared to Vector-MSC-treated mice. In addition, iOPN-MSCs effectively alleviated colon damage and decreased intestinal inflammatory infiltration (Fig. 3j). The levels of proinflammatory cytokines in the mouse colon, such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-17, and IL-4, were also reduced in iOPN-MSC-treated IBD mice (Fig. 3k).

Fig. 3.

iOPN improved therapeutic effects of MSCs on ConA-induced acute liver damage and inflammatory bowel disease. Animals were divided into four groups: naïve, disease, Vector-MSCs-treated and iOPN-MSCs-treated groups. a–e Mice were intravenously injected with ConA (20 mg/kg); untreated, Vector-MSCs and iOPN-MSCs were transfused immediately (n = 5 per group). Eight hours later, liver and serum samples were collected. a Schematic diagrams of ConA-induced inflammatory liver injury. b Serum levels of ALT and AST were measured. c Hematoxylin and eosin staining of liver sections. d Hepatocyte apoptosis was determined by TUNEL staining. e Levels of serum IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-4 and IL-17 were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. f–k Mice were fed DSS, untreated, Vector-MSCs and iOPN-MSCs were transfused every two days (n = 5 per group). f Schematic diagrams of IBD. g Body weight changes are shown as the percentage of the initial weight of WT mice treated with DSS. h The DAI score of mice was calculated by observing the symptoms of fecal thinness and bleeding on Day 10. i The mice were dissected on Day 10, representative colonic specimens were observed, and the colonic length was measured. j The colon tissues of mice were collected on Day 10. HE staining was performed for histopathological examination of the colon. k The levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-4 and IL-17 in the colon were measured by quantitative real-time PCR. Representative pictures are shown. The results are representative of three to six independent experiments. Values are shown as the mean ± SEM and statistical significance is indicated as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001

To determine the mechanisms by which iOPN-MSCs alleviated ConA-induced acute liver injury, changes within T lymphocyte populations in the liver and spleen were examined. Compared with Vector-MSC treatment, administration of iOPN-MSCs significantly reduced the percentages and absolute numbers of CD4+ T cells in the spleens and livers of ConA-induced liver damage mice (Fig. S4a). We further observed the bioactivities of T cells in mice upon MSC-treatment in the pathogenesis of ConA-induced acute liver injury. Mononuclear cells derived from spleens and livers were isolated for further analyses. There was a considerably lower percentage of BrdU-positive CD4+ T cells in the liver and spleen of iOPN-MSC-treated mice with liver damage, indicating that iOPN-MSCs could inhibit T-cell proliferation in vivo (Fig. S4b). Accordingly, iOPN-MSCs markedly downregulated the expression of activation markers such as CD25 and CD69 in CD4+ T cells compared with Vector-MSCs (Fig. S4c). The effects of MSCs on immune cell subsets in IBD model mice were also evaluated. The percentage and number of CD4+ T cells in the colon and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) were decreased in iOPN-MSC-treated mice compared with Vector-MSC-treated mice (Fig. S4d). Moreover, the percentages of neutrophils and macrophages were decreased in the colons of mice treated with iOPN-MSCs (Fig. S4e). Thus, overexpression of iOPN enhanced the treatment effect of MSCs on inflammatory diseases.

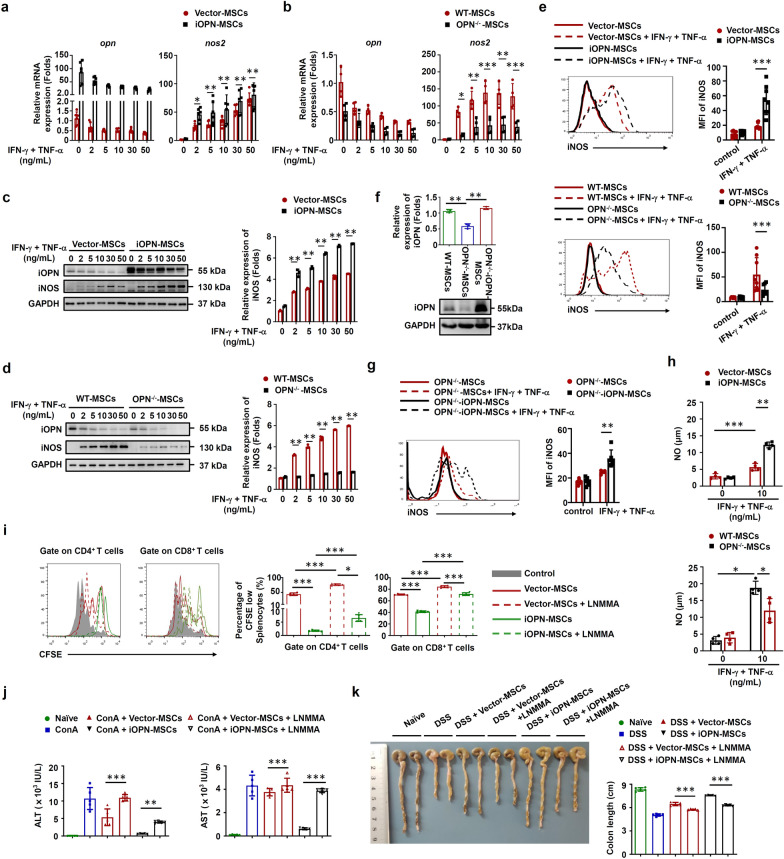

iOPN is essential for the induction of iNOS in MSCs

The immunosuppressive activity of MSCs is dependent on immunosuppressive mediators such as iNOS and IL-10 to inhibit T-cell proliferation [1]. To determine the mechanisms underlying iOPN-mediated regulation of MSC immunosuppression, iOPN was overexpressed in MSCs and then stimulated with IFN-γ plus TNF-α to evaluate the expression of these immunosuppressive factors. The results revealed that iOPN overexpression in MSCs significantly upregulated iNOS expression at both the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 4a, c, e–g). Accordingly, the levels of NO, a downstream product of iNOS in murine MSCs and an effector of immunosuppression, were significantly increased in the supernatant fraction of iOPN-MSCs stimulated with inflammatory cytokines (Fig. 4h). In addition, compared with WT-MSCs, OPN−/−-MSCs exhibited downregulated iNOS expression and less NO in the supernatant of the culture medium after IFN-γ plus TNF-α stimulation (Fig. 4b, d, e and h). Gene correlation heatmap also indicated that the gene expression of OPN and iNOS were positively correlated in MSCs (Fig. S5). Furthermore, a functional study showed that LNMMA, an inhibitor of iNOS, reversed the enhanced suppressive effects of iOPN-MSCs on T-cell proliferation and liver and intestinal damage (Fig. 4i–k). Altogether, these data collectively suggested that iOPN overexpression could enhance the immunosuppressive capacity of MSCs through upregulation of iNOS.

Fig. 4.

iOPN upregulated iNOS expression to promote the immunosuppressive capacity of MSCs. a–h Vector-MSCs and iOPN-MSCs or WT-MSCs, OPN−/−-MSCs and iOPN-OPN−/−-MSCs were treated with TNF-α plus IFN-γ as indicated for 24 h. Protein, mRNA and cells were collected. a and b Expression of Opn and Nos2 was measured by quantitative real-time PCR. c and d Expression of Opn and iNOS was measured by immunoblotting analysis. Full-length blots are presented in Additional file 1: Fig. 4c and d. f Murine OPN−/−-MSCs were transfected with pcDNA3.1-Vector or pcDNA3.1 containing iOPN, and OPN expression was measured by immunoblotting analysis. Full-length blots are presented in Additional file 1: Fig. 4f. e, g The expression of iNOS in MSCs was determined by flow cytometry. h The concentration of nitric oxide (NO) in the culture supernatant was determined by Griess assay. i iOPN-MSCs were pretreated with the iNOS inhibitor LNMMA for 12 h. Irradiated MSCs were cocultured with CFSE-labeled splenocytes for 3 days in the presence of anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies at the indicated ratios. CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells were collected for proliferation analysis by flow cytometry at the end of coculture. j and k Mice were intravenously injected with ConA or fed DSS, untreated, Vector-MSCs, or iOPN-MSCs were transfused every 2 days. LNMMA was intraperitoneally injected into the iOPN-MSC-treated group (n = 5 per group). Serum levels of ALT and AST were measured (j). Representative colonic specimens were observed, and the colonic length was measured (k). The results are representative of three to six independent experiments. Values are shown as the mean ± SEM and statistical significance is indicated as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001

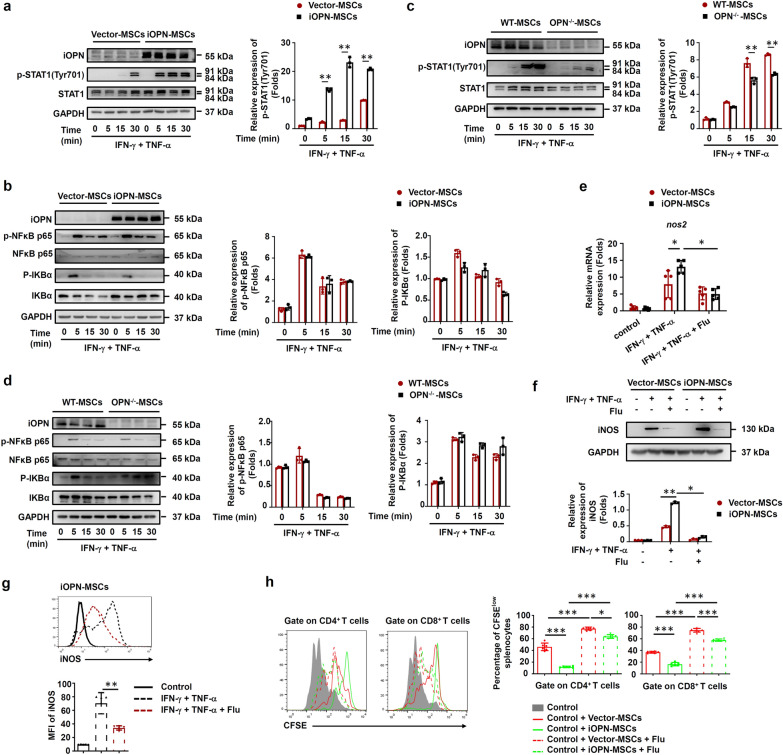

iOPN promotes STAT1 protein stability

NF-κB and STAT1 are essential for IFN-γ plus TNF-α-induced iNOS expression. As shown in Fig. 5a, iOPN overexpression in MSCs dramatically promoted the phosphorylation of STAT1 at Tyr701 after IFN-γ plus TNF-α stimulation. However, the phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 and IκBα was slightly different between iOPN-MSCs and Vector-MSCs (Fig. 5b). In contrast, OPN deficiency inhibited the activation of STAT1 and had little effect on the phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 and IκBα (Fig. 5c, d). In addition, iNOS expression was downregulated when the STAT1 inhibitor was added to iOPN-MSCs (Fig. 5e–g). Furthermore, the immunosuppressive effect of iOPN-MSCs on T-cell proliferation was impaired after STAT1 activity was inhibited (Fig. 5h). These results suggested that iOPN upregulates iNOS expression by activating the STAT1 pathway, thereby improving MSC immunosuppression.

Fig. 5.

iOPN promoted STAT1-mediated immunosuppression in MSCs. a–d Vector-MSCs and iOPN-MSCs or WT-MSCs and OPN−/−-MSCs were treated with or without TNF-α plus IFN-γ (10 ng/mL) for the indicated times. Cells were harvested, and OPN, NF-κB p65, STAT1, IKBα, phosphorylation of NF-κB p65, phosphorylation of STAT1 at Tyr701 and phosphorylation of IKBα were analyzed by immunoblotting analysis. Full-length blots are presented in Additional file 1: Fig. 5a-d. e–g Vector-MSCs and iOPN-MSCs were stimulated with TNF-α plus IFN-γ (10 ng/mL) for 12 h. The STAT1 inhibitor fludarabine (Flu, 2 μM) was then added to the culture medium of Vector-MSCs and iOPN-MSCs. The expression of iNOS was determined by quantitative real-time PCR (e), immunoblotting analysis (f) and flow cytometry (g). Full-length blots are presented in Additional file 1: Fig. 5f. h Vector-MSCs and iOPN-MSCs were pretreated with DMSO or fludarabine (Flu, 2 μM) for 6 h and then irradiated and cocultured with CFSE-labeled splenocytes activated by anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies for 3 days at a ratio of 1:20. CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells were stained for proliferation analysis by flow cytometry at the end of coculture, and the percentages of proliferating T cells are shown. The results are representative of three to six independent experiments. Values are shown as the mean ± SEM and statistical significance is indicated as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001

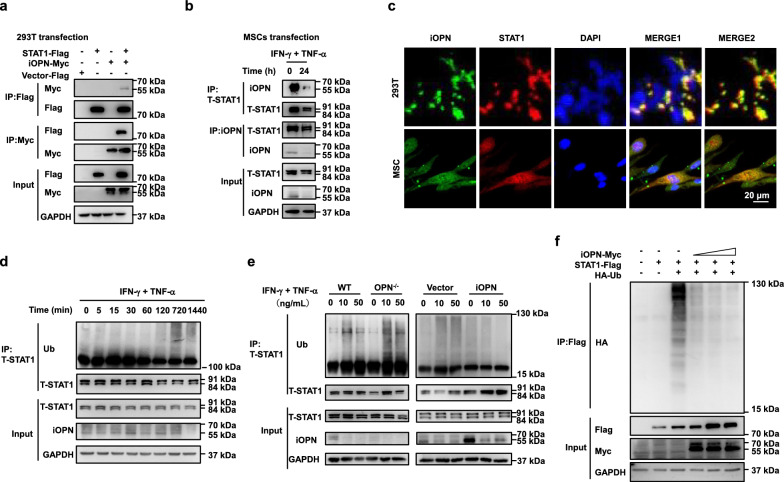

We next examined how iOPN modulated STAT1 activity. To define the targets regulated by iOPN, we performed coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiments. We found that iOPN bound to the STAT1 protein either in a 293T cell overexpression system (Fig. 6a) or in MSCs with or without inflammatory stimulation (Fig. 6b). The interaction of these two proteins was further supported by immunofluorescence analysis. GFP-iOPN and red fluorescent protein-STAT1 were colocalized in the cytoplasm and nucleus in 293T cells and MSCs (Fig. 6c). Previous studies have demonstrated that OPN can regulate protein polyubiquitination and degradation [17, 18], which suggested that we should investigate whether iOPN regulates STAT1 ubiquitination in MSCs. We found that STAT1 polyubiquitination was increased, especially after 12 h of inflammatory stimulation in MSCs (Fig. 6d). In addition, OPN deletion promoted the polyubiquitination of STAT1, while iOPN overexpression inhibited STAT1 polyubiquitination in MSCs (Fig. 6e). To confirm the effects of degradation of STAT1 by iOPN, we cotransfected Flag-STAT1 and different doses of Myc-iOPN into 293 T cells and found that the transfected amount of iOPN led to even less readily detectible ubiquitination (Fig. 6f). Collectively, these data demonstrated that iOPN interacts with STAT1 and inhibits its degradation, which contributes to increased NO production in MSCs.

Fig. 6.

iOPN promoted STAT1 deubiquitination. a 293T cells were transfected with Myc-iOPN expression plasmid together with expression plasmid of Flag-STAT1 or Vector-STAT1, followed by IP with anti-Myc antibody and western blot with anti-Flag antibody or adverse. Input, western blot of whole-cell lysate with the indicated antibodies. b MSCs were treated with or without TNF-α plus IFN-γ (10 ng/mL) for 24 h, followed by IP with anti-STAT1 antibody and western blot with anti-OPN antibody, IP with anti-OPN antibody and western blot with anti-STAT1 antibody. Input, western blot of whole-cell lysate with the indicated antibodies. c Fluorescent images of 293T cells transfected with Myc-iOPN together with Flag-STAT1. Nuclei, Myc-iOPN and Flag-STAT1 were labeled with DAPI (blue), antibody to Myc tag (green) and antibody to Flag tag (red), respectively. d MSCs were stimulated with TNF-α plus IFN-γ (10 ng/mL) for different periods of time, followed by immunoprecipitation with anti-STAT1 antibody and then blotted with anti-ubiquitin antibody. Next, lysates were immunoblotted with different antibodies, followed by band visualization. e Vector-MSCs and iOPN-MSCs or WT-MSCs and OPN−/−-MSCs were treated with or without TNF-α plus IFN-γ at the indicated concentration for 24 h, followed by immunoprecipitation with anti-STAT1 antibody and then blotted with the anti-Ubiquitin antibody. The lysates were immunoblotted with different antibodies. f 293T cells transfected with the indicated plasmids were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Flag antibody and then blotted with anti-HA antibody. Input, western blot of whole-cell lysate with the indicated antibodies. The data are representative of three biological replicates. All Full-length blots are presented in Additional file 1: Fig. 6a,b and d–f

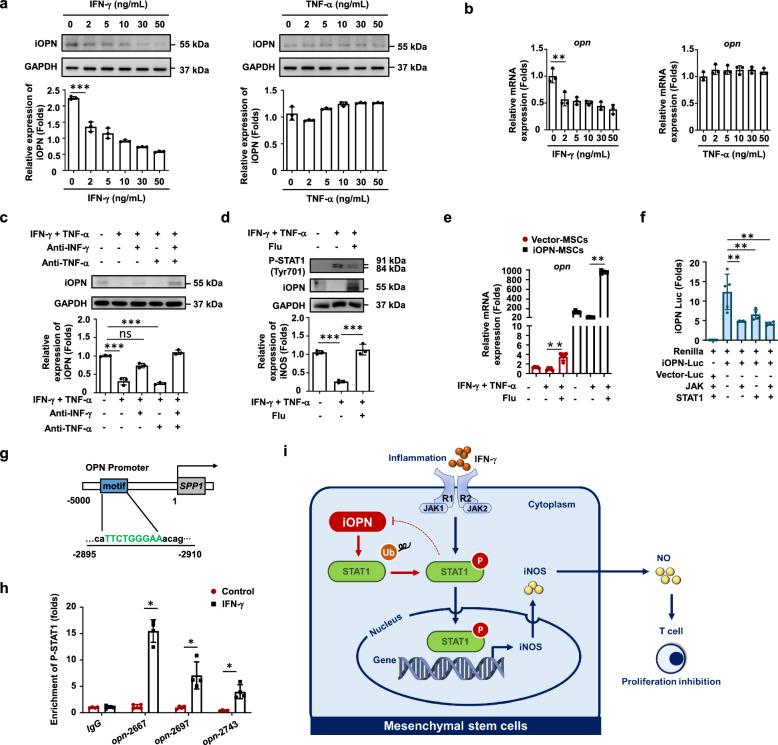

IFN-γ-activated STAT1 inhibits OPN expression in MSCs

To determine how OPN was inhibited upon inflammatory stimulation, IFN-γ or TNF-α alone was used to stimulate MSCs. The data showed that only IFN-γ significantly inhibited OPN expression in MSCs (Fig. 7a, b). Furthermore, we found that the neutralizing antibody against IFN-γ reversed the expression of iOPN, while the neutralizing antibody against TNF-α could not induce proinflammatory cytokine stimulation (Fig. 7c). These results indicated that IFN-γ, but not TNF-α, led to OPN downregulation in MSCs. Studies have reported that hnRNP-A/B proteins and T-bet can modulate OPN expression in murine macrophages and T cells [19, 20]. Therefore, we tested whether IFN-γ inhibited OPN expression in MSCs by regulating hnRNP-A/B or T-bet. The results revealed that the expression of both hnRNP-A/B and T-bet was upregulated in MSCs after IFN-γ stimulation (Fig. S6a). However, knockdown of hnRNP-A/B or T-bet in MSCs could not restore the expression of OPN in MSCs under inflammation (Fig. S6b, c). Interestingly, when a STAT1 inhibitor was added, the expression of iOPN in MSCs was recovered under inflammatory stimulation (Fig. 7d, 7e). As expected, the JAK/STAT1 protein inhibited iOPN luciferase activity in 293T cells (Fig. 7f). Since phosphorylated STAT1 enters the nucleus to promote the transcription of target genes, we hypothesized that phosphorylated STAT1 binds to the promoter regions of OPN to regulate OPN expression. ChIP assays identified that there was a strong enrichment of STAT1 in the promoter regions (− 5000 bp to TSS, transcription start site) of OPN in MSCs after inflammatory stimulation (Fig. 7g, h), whereas there was little STAT1-binding DNA of the OPN promoter in control MSCs (Fig. 7h). These results established that OPN is a direct target that is silenced by IFN-γ-activated STAT1 in MSCs.

Fig. 7.

iOPN was downregulated by IFN-γ-induced activation of STAT1 in MSCs. a and b Murine MSCs were treated with IFN-γ or TNF-α at the indicated concentration for 24 h. mRNA and protein of MSCs were collected. OPN expression was determined at the mRNA and protein levels by quantitative real-time PCR and immunoblotting analysis. Full-length blots are presented in Additional file 1: Fig. 7a. c Neutralizing antibodies against IFN-γ, TNF-α or both were added to the medium of MSCs stimulated with IFN-γ or TNF-α. OPN expression was determined by immunoblotting analysis. Full-length blots are presented in Additional file 1: Fig. 7c. d–e The STAT1 inhibitor fludarabine (Flu, 2 μM) was added to the culture medium of MSCs with TNF-α plus IFN-γ (10 ng/mL) for 24 h. The expression of OPN and phosphorylation of STAT1 at Tyr701 were determined by immunoblotting analysis (d). Full-length blots are presented in Additional file 1: Fig. 7d. The mRNA expression of OPN was determined by quantitative real-time PCR (e). f iOPN luciferase activity in 293 T cells transfected with luciferase reporter and indicated expression vectors. g Schematic representation showing a conserved STAT1-binding motif located in the promoter region of OPN genes between − 2,895 and − 2,910 bp. h Enrichment of p-STAT1 at the promoter of OPN was analyzed by ChIP-PCR. i Working model of the regulation of iOPN on the immunosuppressive capacity of MSCs. The results are representative of three to six independent experiments. Values are shown as the mean ± SEM and statistical significance is indicated as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. ns = no significance

As summarized in Fig. 7i, our studies reveal that iOPN positively regulated the immunosuppressive capacity of MSCs. When activated by IFN-γ, iOPN was down-regulated by activating STAT1 signaling, which further increased the ubiquitination of STAT1, thereby reducing the master immunosuppressive mediator iNOS in MSCs. NO was then decreased and T-cell proliferation was enhanced. Thus, the reduced iOPN in MSCs after IFN-γ stimulation impaired the immunosuppressive capacity of MSCs.

Discussion

MSCs are adult stem cells that play a role in immunoregulation, which suggests that MSCs have important research value and broad clinical application prospects in the treatment of a variety of inflammatory diseases. However, the mechanisms regulating the immunosuppressive capacity of MSCs are still poorly understood. We previously elucidated that autophagy occurred in MSCs in an inflammatory microenvironment, and inhibition of autophagy could improve the immunosuppression of MSCs to enhance their therapeutic effects on inflammatory diseases [8]. Here, we found that iOPN plays an essential role in the immunosuppression of MSCs induced by inflammatory factors. Our data showed that in response to IFN-γ, OPN was inhibited in MSCs, as manifested by increased phosphorylated STAT1 at the mRNA and protein levels. OPN depletion impaired, while iOPN overexpression effectively enhanced, the immunosuppression of MSCs on the proliferation of T cells by regulating the expression of iNOS, thus improving the therapeutic effects of MSCs on inflammatory diseases.

OPN belongs to the small integrin-binding ligand N-linked glycoprotein family. Recent studies have found that OPN plays important roles in immune responses and is involved in the pathogenesis of a wide variety of diseases [21–25]. For example, OPN production by DC subsets is emerging as a crucial mechanism of regulation in inflammatory bowel disease and has started to be exploited as a therapeutic target [26]. Moreover, OPN is also expressed in bone marrow stromal cells, negatively regulating the stem cell pool size and the function of hematopoietic stem cells [27, 28]. It was clarified that sOPN had effects on MSC osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation [14], but the effect of sOPN and iOPN on MSC immunosuppressive capacity was not clear. We identified that sOPN and iOPN expression was downregulated in MSCs by stimulation with the proinflammatory cytokines IFN-γ plus TNF-α. OPN exists as two isoforms: iOPN and sOPN. Opn mRNA has the canonical AUG translation initiation site and an alternative translation initiation site [13]. Compared with the translation initiation of iOPN, sOPN has an N-terminal signal sequence that regulates OPN secretion into the extracellular space [13].

Intervening with OPN by gene knockout, we first found that OPN positively regulated the immunosuppressive capacity of murine MSCs, characterized by decreased iNOS levels in murine MSCs. Thus, OPN knockout cannot distinguish the effects of iOPN or sOPN on MSC function. Neutralizing antibodies and exogenous OPN were used to exclude the impact of sOPN on MSC immunosuppression capacity in our study. iOPN overexpression was performed to confirm the impact of iOPN on MSC immunosuppression capacity. We observed that iOPN, but not sOPN, enhanced the immunosuppression capacity of MSCs by enhancing NO expression levels and promoting the survival of MSCs. The sources of sOPN in the inflammatory disease microenvironment are varied. Autocrine or paracrine sOPN binds to its receptors on immune cells and promotes the immune response by activating the phosphorylation of downstream signaling molecules, which in turn promote the proliferation, activation, and cytokine production, and suppresses the apoptosis, of immune cells [29]. Based on our results, dissociative sOPN in the disease microenvironment has no effect on MSC immunosuppression.

Since we have found that iOPN can affect the immunosuppression of MSCs in vitro, we employed ConA-induced inflammatory liver injury and IBD mouse models, two well-established models induced by acute immune responses, in which T lymphocytes are identified as the major effector cells [30, 31]. Several studies have reported that human tonsil and murine adipose tissue-derived MSCs can ameliorate the development of ConA-induced liver injury and IBD. Han et al. first found that murine bone morrow MSCs had no effect on this acute inflammatory disease model, while interleukin-17-pretreated MSCs exhibited enhanced therapeutic effects [32]. In the present study, untreated MSCs had poor therapeutic effects on ConA-induced liver injury, while iOPN-MSCs notably alleviated this inflammatory disease and IBD, further supporting the immunosuppressive function of MSCs. The high standard deviations were observed in our data, which mainly exists in Fig. 3. The variability could be due to the biological diversity within sample group in mice. In addition, potential errors in the measurement errors cannot be excluded. To address these issues, suggestions could be adopted in future studies such as by increasing sample size, improving experimental design, or using more precise measurement techniques. Despite the high variability in our study, it does not affect the statistical significance of our results. We came to a solid conclusion that overexpression of iOPN enhanced the treatment effect of MSCs on inflammatory diseases after three repetitions of the experiment.

Various regulatory mechanisms contribute to MSC-mediated immunosuppression. Among them, the immunosuppressive molecules produced by themselves were essential for the immunosuppressive effects of MSCs, which subsequently led to the inhibition of T-cell proliferation [33]. The majority of immunosuppressive molecules produced by inflammatory factor-activated MSCs are iNOS, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, prostaglandin E2, and heme oxygenase [5]. We found that overexpression of iOPN further increased cytokine-induced NO production in murine MSCs, and inhibition of iNOS by L-NMMA markedly abolished the enhanced immunosuppressive capacity of iOPN-overexpressing MSCs. Thus, iNOS plays an important role in iOPN-mediated modulation of murine MSC immunosuppression. MSCs also exert their immunosuppressive effects on innate immune cells such as B cells, DCs, and macrophages. For B cells, MSCs can block their cell cycle and downregulate the expression of chemokine receptors to inhibit B-cell proliferation and migration [34, 35]. Similarly, the proliferation, cytokine secretion, cell maturation and activation of DCs and macrophages are also suppressed by MSCs with inflammatory stimulation [36, 37]. In our study, the percentage of neutrophils and macrophages in the colon was decreased dramatically after iOPN-MSC treatment, and the molecular mechanisms through which iOPN affects the immunosuppression of innate immune cells by MSCs are still not clear.

Our results further revealed the molecular mechanisms underlying iOPN-mediated regulation of iNOS expression to promote immunosuppression of MSCs. STAT1 and NF-κB signaling are critical for IFN-γ-induced iNOS expression in macrophages and MSCs [38, 39]. The activation of STAT1 or NF-κB is involved in the induction of OPN expression, while OPN can in turn inhibit the activation of STAT1 to suppress the expression of target genes [40]. In this study, we found that the level and duration of STAT1 phosphorylation were significantly increased in iOPN-MSCs, resulting in enhanced activation of STAT1 signaling to upregulate iNOS expression in murine MSCs. Moreover, we found that the activation of NF-κB signaling, another pathway essential for iNOS expression, was not essential for the enhanced immunosuppressive capacity of iOPN-MSCs. In addition, after inhibition of STAT1 signaling using a specific inhibitor in MSCs, the upregulated expression of iNOS, its production of NO, and decreased T-cell proliferation resulting from overexpression of iOPN were abolished. These results suggested that iOPN-mediated immunosuppression of MSCs was dependent on the activation of STAT1.

iOPN was identified to function as an adaptor molecule to facilitate the formation of a receptor cluster or associate with signaling molecules, resulting in protein kinase activation. It is interesting and necessary to discover the substrate proteins undergoing regulation in iOPN-mediated increased activation of STAT1. Under the stimulus of extracellular signals, signaling molecules can be modified after translation, including phosphorylation, acetylation, methylation and ubiquitination [41]. Among them, there is synergistic crosstalk between phosphorylation and ubiquitination to precisely regulate intracellular signal transduction pathways, which play important roles in regulating cell function [42, 43]. Our results showed that STAT1 polyubiquitination was increased, especially after 12 h of inflammatory stimulation in MSCs. The results also revealed that iOPN interacted with STAT1 and that overexpression of iOPN decreased the ubiquitination of STAT1 in MSCs. We hypothesized that the iOPN-mediated enhanced levels of activated STAT1 resulted indirectly from decreased degradation. iOPN alone does not have the ability to modulate protein ubiquitination. STAT1 polyubiquitination is regulated by E3 ligases, such as RNF220 and TRIM6 [44, 45]. Thus, iOPN may recruit deubiquitinating enzymes to stabilize STAT1 or prevent the E3 ligase from binding to STAT1 in MSCs.

MSCs are activated to exert their immunomodulatory effects after stimulation with IFN-γ in the presence of one (or more) other cytokine(s), including TNF-α, IL-1α or IL-1β. The critical role of IFN-γ and its receptor IFN-γR in this process has been demonstrated in experiments with antibodies against IFN-γ or IFN-γR, as well as in MSCs deficient in IFN-γR1 [33, 46]. Our report indicated that IFN-γ-activated STAT1, but not TNF-α, led to OPN inhibition in MSCs, which further suggested the major role of IFN-γ among inflammatory cytokines in regulating the immunosuppressive capacity of MSCs. It was also found that iOPN interacted with and mediated the deubiquitination of STAT1, which forms a negative feedback loop to restrain the immunosuppressive capacity of MSCs.

Conclusion

Our study showed that inflammation downregulated iOPN expression, which weakened the immunosuppressive ability of MSCs. iOPN positively regulated the immunosuppressive capacity of MSCs by upregulating the expression of iNOS, thereby improving their therapeutic effects on ConA-induced inflammatory liver injury and IBD. The present study provides a new intervention target to improve the clinical therapeutic efficacy of MSCs in T-cell-mediated inflammatory disorders.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 3: Supplementary figures and figure legends

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (82271589, 82300584, 82000567, 82000553, 82001739, 82070191, 82071727) and the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFA0107201). The authors declare that artificial intelligence is not used in this study.

Author contributions

J.H., Y.Z. and G.Z. designed the research. W.Y. performed the experiments in vitro and wrote the paper. M.J. performed the experiments in vivo and assisted with the data analysis. Y.G., X.Z., L.Z., S.H., H.W., X.D., B.W., T.J. and Y.X. assisted with experiments. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Data availability

The data of RNA-sequencing was uploaded as a supplementary file named clean data. All data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The animal protocol (SINH-2020-ZYY-2), titled “Inflammatory and immune-related diseases” approved in September 2021 was performed according to the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences and complied with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The reporting of animal experiments adheres to the ARRIVE guidelines.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Wanlin Yang and Min Jin have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Guoqiang Zhou, Email: chowgq0568@163.com.

Jiefang Huang, Email: jfhuangsibs@126.com.

Yanyun Zhang, Email: yyzhang@sibs.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Shi Y, Wang Y, Li Q, Liu K, Hou J, Shao C, et al. Immunoregulatory mechanisms of mesenchymal stem and stromal cells in inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14:493–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Y, Fang J, Liu B, Shao C, Shi Y. Reciprocal regulation of mesenchymal stem cells and immune responses. Cell Stem Cell. 2022;29:1515–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prockop DJ, Oh JY. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs): role as guardians of inflammation. Mol Ther. 2012;20:14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y, Cai W, Huang Q, Gu Y, Shi Y, Huang J, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells alleviate bacteria-induced liver injury in mice by inducing regulatory dendritic cells. Hepatology. 2014;59:671–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Chen X, Cao W, Shi Y. Plasticity of mesenchymal stem cells in immunomodulation: pathological and therapeutic implications. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:1009–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han Y, Yang J, Fang J, Zhou Y, Candi E, Wang J, et al. The secretion profile of mesenchymal stem cells and potential applications in treating human diseases. Signal Transduct Tar. 2022;7:92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu C, Ren G, Cao G, Chen Q, Shou P, Zheng C, et al. miR-155 regulates immune modulatory properties of mesenchymal stem cells by targeting TAK1-binding protein 2. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:11074–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dang S, Xu H, Xu C, Cai W, Li Q, Cheng Y, et al. Autophagy regulates the therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Autophagy. 2014;10:1301–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Y, Wang L, Kikuiri T, Akiyama K, Chen C, Xu X, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-based tissue regeneration is governed by recipient T lymphocytes via IFN-γ and TNF-α. Nat Med. 2011;17:1594–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caputo S, Bellone M. Osteopontin and the immune system: another brick in the wall. Cell Mol Immunol. 2018;15:405–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pang X, Gong K, Zhang X, Wu S, Cui Y, Qian B-Z. Osteopontin as a multifaceted driver of bone metastasis and drug resistance. Pharmacol Res. 2019;144:235–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Del Prete A, Scutera S, Sozzani S, Musso T. Role of osteopontin in dendritic cell shaping of immune responses. Cytokine Growth F R. 2019;50:19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoue M, Shinohara ML. Intracellular osteopontin (iOPN) and immunity. Immunol Res. 2011;49:160–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Q, Shou P, Zhang L, Xu C, Zheng C, Han Y, et al. An osteopontin-integrin interaction plays a critical role in directing adipogenesis and osteogenesis by mesenchymal stem cells. Stem cells. 2014;32:327–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu J, Wang X, Chen J, Chen S, Li Z, Liu H, et al. Embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells promote colon epithelial integrity and regeneration by elevating circulating IGF-1 in colitis mice. Theranostics. 2020;10:12204–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang J, Huang J, Gu Y, Xue M, Qian F, Wang B, et al. Inflammation-induced inhibition of chaperone-mediated autophagy maintains the immunosuppressive function of murine mesenchymal stromal cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18:1476–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao K, Zhang M, Zhang L, Wang P, Song G, Liu B, et al. Intracellular osteopontin stabilizes TRAF3 to positively regulate innate antiviral response. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao C, Mi Z, Guo H, Kuo PC. Osteopontin regulates ubiquitin-dependent degradation of Stat1 in murine mammary epithelial tumor cells. Neoplasia. 2007;9:699–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shinohara ML, Jansson M, Hwang ES, Werneck MBF, Glimcher LH, Cantor H. T-bet-dependent expression of osteopontin contributes to T cell polarization. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17101–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao C, Guo H, Mi Z, Wai PY, Kuo PC. Transcriptional regulatory functions of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein-U and -A/B in endotoxin-mediated macrophage expression of osteopontin. J Immunol. 2005;175:523–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uede T. Osteopontin, intrinsic tissue regulator of intractable inflammatory diseases. Pathol Int. 2011;61:265–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shevde LA, Samant RS. Role of osteopontin in the pathophysiology of cancer. Matrix Biol. 2014;37:131–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inoue M, Moriwaki Y, Arikawa T, Chen Y-H, Oh YJ, Oliver T, et al. Cutting edge: critical role of intracellular osteopontin in antifungal innate immune responses. J Immunol. 2011;186:19–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leavenworth JW, Verbinnen B, Wang Q, Shen E, Cantor H. Intracellular osteopontin regulates homeostasis and function of natural killer cells. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:494–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rittling SR, Singh R. Osteopontin in Immune-mediated Diseases. J Dent Res. 2015;94:1638–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kourepini E, Aggelakopoulou M, Alissafi T, Paschalidis N, Simoes DCM, Panoutsakopoulou V. Osteopontin expression by CD103- dendritic cells drives intestinal inflammation. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E856–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kreke MR, Huckle WR, Goldstein AS. Fluid flow stimulates expression of osteopontin and bone sialoprotein by bone marrow stromal cells in a temporally dependent manner. Bone. 2005;36:1047–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nilsson SK, Johnston HM, Whitty GA, Williams B, Webb RJ, Denhardt DT, et al. Osteopontin, a key component of the hematopoietic stem cell niche and regulator of primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 2005;106:1232–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang KX, Denhardt DT. Osteopontin: role in immune regulation and stress responses. Cytokine Growth F R. 2008;19:333–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang H-X, Liu M, Weng S-Y, Li J-J, Xie C, He H-L, et al. Immune mechanisms of Concanavalin A model of autoimmune hepatitis. World J Gastroentero. 2012;18:119–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khor B, Gardet A, Xavier RJ. Genetics and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2011;474:307–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Han X, Yang Q, Lin L, Xu C, Zheng C, Chen X, et al. Interleukin-17 enhances immunosuppression by mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21:1758–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ren G, Zhang L, Zhao X, Xu G, Zhang Y, Roberts AI, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated immunosuppression occurs via concerted action of chemokines and nitric oxide. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:141–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fan L, Hu C, Chen J, Cen P, Wang J, Li L. interaction between mesenchymal stem cells and B-cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacFarlane RJ, Graham SM, Davies PSE, Korres N, Tsouchnica H, Heliotis M, et al. Anti-inflammatory role and immunomodulation of mesenchymal stem cells in systemic joint diseases: potential for treatment. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2013;17:243–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wada N, Gronthos S, Bartold PM. Immunomodulatory effects of stem cells. Periodontol. 2000;2013(63):198–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Castro LL, Lopes-Pacheco M, Weiss DJ, Cruz FF, Rocco PRM. Current understanding of the immunosuppressive properties of mesenchymal stromal cells. J Mol Med. 2019;97:605–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen X, Gan Y, Li W, Su J, Zhang Y, Huang Y, et al. The interaction between mesenchymal stem cells and steroids during inflammation. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5: e1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kanda N, Shimizu T, Tada Y, Watanabe S. IL-18 enhances IFN-gamma-induced production of CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 in human keratinocytes. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:338–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao C, Guo H, Mi Z, Grusby MJ, Kuo PC. Osteopontin induces ubiquitin-dependent degradation of STAT1 in RAW264.7 murine macrophages. J Immunol. 2007;178:1870–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hsu C-Y, Fu S-H, Chien M-W, Liu Y-W, Chen S-J, Sytwu H-K. Post-translational modifications of transcription factors harnessing the etiology and pathophysiology in colonic diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:3207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Si W, Zhou B, Xie W, Li H, Li K, Li S, et al. Angiogenic factor AGGF1 acts as a tumor suppressor by modulating p53 post-transcriptional modifications and stability via MDM2. Cancer Lett. 2020;497:28–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swaney DL, Beltrao P, Starita L, Guo A, Rush J, Fields S, et al. Global analysis of phosphorylation and ubiquitylation cross-talk in protein degradation. Nat Methods. 2013;10:676–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guo X, Ma P, Li Y, Yang Y, Wang C, Xu T, et al. RNF220 mediates K63-linked polyubiquitination of STAT1 and promotes host defense. Cell Death Differ. 2021;28:640–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rajsbaum R, Versteeg GA, Schmid S, Maestre AM, Belicha-Villanueva A, Martínez-Romero C, et al. Unanchored K48-linked polyubiquitin synthesized by the E3-ubiquitin ligase TRIM6 stimulates the interferon-IKKε kinase-mediated antiviral response. Immunity. 2014;40:880–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krampera M, Cosmi L, Angeli R, Pasini A, Liotta F, Andreini A, et al. Role for interferon-gamma in the immunomodulatory activity of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:386–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 3: Supplementary figures and figure legends

Data Availability Statement

The data of RNA-sequencing was uploaded as a supplementary file named clean data. All data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.