Abstract

Infection of epithelial cells by some animal rotaviruses, but not human or most animal rotaviruses, requires the presence of N-acetylneuraminic (sialic) acid (SA) on the cell surface for efficient infectivity. To further understand how rotaviruses enter susceptible cells, six different polarized epithelial cell lines, grown on permeable filter membrane supports containing 0.4-μm pores, were infected apically or basolaterally with SA-independent or SA-dependent rotaviruses. SA-independent rotaviruses applied apically or basolaterally were capable of efficiently infecting both sides of the epithelium of all six polarized cell lines tested, while SA-dependent rotaviruses only infected efficiently through the apical surface of five of the polarized cell lines tested. Regardless of the route of virus entry, SA-dependent and SA-independent rotaviruses were released almost exclusively from the apical domain of the plasma membrane of polarized cells before monolayer disruption or cell lysis. The transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) of cells decreased at the same time, irrespective of whether infection with SA-independent rotaviruses occurred apically or basolaterally. The TER of cells infected apically with SA-dependent rotaviruses decreased earlier than that of cells infected basolaterally. Rotavirus infection decreased TER before the appearance of cytopathic effect and cell death and resulted in an increase in the paracellular permeability to [3H]inulin as a function of loss of TER. The presence of SA residues on either the apical or basolateral side was determined using a Texas Red-conjugated lectin, wheat germ agglutinin (WGA), which binds SA residues. WGA bound exclusively to SA residues on the apical surface of the cells, confirming the requirement for SA residues on the apical cell membrane for efficient infectivity of SA-dependent rotaviruses. These results indicate that the rotavirus SA-independent cellular receptor is present on both sides of the epithelium, but SA-dependent and SA-independent rotavirus strains infect polarized epithelial cells by different mechanisms, which may be relevant for pathogenesis and selection of vaccine strains. Finally, rotavirus-induced alterations of the epithelial barrier and paracellular permeability suggest that common mechanisms of pathogenesis may exist between viral and bacterial pathogens of the intestinal tract.

Group A rotaviruses, which infect the polarized mature enterocytes of the villus epithelium of the small intestine, are the most important viral cause of acute gastroenteritis in young children and the young of many animal species (6). Rotavirus infection is mediated by binding of the virus attachment protein VP4 to the rotavirus cellular receptor(s) (10), but the identity of such a receptor(s) remains controversial (reviewed in reference 6). A minority of animal rotaviruses require the presence of N-acetylneuraminic (sialic) acid (SA) residues on the cell surface for efficient binding and infectivity, while most animal and human rotaviruses do not require SA for such functions (5). The isolation of SA-independent animal rotavirus strain variants, from SA-dependent strains that bind to and infect cells efficiently, confirms that binding to SA is not an essential step for rotavirus infection (5, 41). Protease treatment of rotaviruses enhances viral infectivity by cleaving the spike protein VP4 into VP5* and VP8* (6, 11). Binding of SA-dependent rotavirus strains to cells is initially mediated by VP8* through SA residues and then by VP5*, while binding of SA-independent rotavirus strains is mediated directly by VP5* (66), although the VP8* of SA-independent rotavirus strains may interact with other non-SA receptors. Hence, an SA-independent rotavirus receptor is likely involved in entry of both SA-dependent (after an initial interaction with SA residues) and SA-independent rotavirus strains.

The rotavirus infection process has been studied extensively in embryonic African green monkey kidney (MA104) cells because these cells are highly permissive to rotavirus infection, are well characterized, and grow easily in culture. However, MA104 cells do not fully display the complex morphological or functional characteristics of the natural rotavirus target cell. Human adenocarcinoma intestinal (Caco-2 or HT-29) cells have been used recently to study the molecular mechanisms that regulate rotavirus replication, intracellular trafficking, cellular responses, and pathogenesis (4, 6,14, 30–32, 35, 42, 49, 53, 57). Caco-2 and HT-29 cells are more suitable for studying rotavirus infection because these cells resemble the epithelial enterocytes of the intestine. For example, they express disaccharidases and peptidases found in cells of the small intestinal villi, form domes on impermeable substrates, transport ions and water, develop tight junctions which prevent the passage of macromolecules through underlying permeable membranes, and develop transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) typical of the polarized epithelium (15, 30, 39, 46, 57, 62). In addition, Caco-2, HT-29, and other polarized continuous cell lines can be grown on permeable supports (porous membrane filters), providing differential access to the apical and basolateral plasma membrane domains.

The apical membrane domain is a highly specialized surface that interacts with coating substances and does not contact adherent cells or extracellular components, while the basolateral membrane domain, which contains the specialized components for cell-to-cell interactions, interacts with the underlying cells and the lamina propria (15, 23, 26, 39, 46, 62). The apical and basolateral membrane domains possess distinct polypeptide and lipid compositions, and culture of polarized epithelial cells on permeable supports has facilitated the study of virus entry into cells relative to the receptor distribution on the apical or basolateral membrane domain of cells. Entry of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), vaccinia virus, reovirus type 1, human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), and Semliki Forest virus (SFV) is restricted to the basolateral surface of cells (19, 20, 29, 48, 50), while entry of simian virus 40 (SV40) and hepatitis A virus (HAV) occurs at the apical surface of cells (2, 7, 8). Influenza virus, poliovirus, and herpes simplex virus type 1 exhibit bidirectional (nonpolar) entry into polarized epithelial cells (20, 52, 61). It has been reported that an SA-dependent rotavirus strain enters polarized Caco-2 and MDCK-1 cells through either the apical or basolateral domain of the plasma membrane (57) and that the same SA-dependent rotavirus strain is released from the apical domain of Caco-2 cells before cell lysis (31).

In attempts to determine if rotavirus strains differ in their modes of cell entry and if cellular factors critical for rotavirus entry are present on a specific cell membrane domain, we examined the uptake of SA-dependent and SA-independent rotaviruses at the apical and basolateral membrane domains of several polarized intestinal and renal cells grown on permeable filters with 0.4-μm pores. Our studies indicate that SA-dependent rotaviruses preferentially enter cells through the apical surface, while the majority of rotaviruses, which are SA independent, enter cells apically or basolaterally and likely use a different receptor. Our results with the SA-dependent viruses differ from those in the earlier report of rotavirus entry into cells because in that study (57), cells were grown on larger-pore (3.0 μm) filters, and we found that cells grow through the 3.0-μm pores but not through the 0.4-μm pores, a fact also reported by others (60).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and culture conditions.

Embryonic rhesus monkey kidney (MA104) cells, originally obtained at passage 37 in 1978 from Microbiological Associates, Bethesda, Md., and at passage 7 in 1999 from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), were grown in medium 199 (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Summit Biotechnology, Fort Collins, Colo.), 0.03% l-glutamine (Gibco-BRL, Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.), and 0.075% sodium bicarbonate (Gibco-BRL). Human colonic adenocarcinoma Caco-2 and HT-29 cells (passages 40 to 62), obtained from ATCC, and primary human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells immortalized with adenovirus type 5 (Ad5, strain F2853-5b) and transformed with the T antigen of SV40, kindly supplied by Richard E. Sutton (Baylor College of Medicine), were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco-BRL) with high glucose (4,500 mg/ml), supplemented with 10% FBS, 0.2 mM nonessential amino acids (NEAA), 10 mM HEPES, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate. The human ileocecal carcinoma T84 cells, supplied by Sheila Crowe (University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Tex.), were cultured in DMEM-Ham's F-12 medium nutrient mixture (DMEM/F12; Sigma) supplemented with 5% newborn calf serum (NBCS; Sigma) and 1% l-glutamine. Human normal colonic CCD-18 and high-passage low-resistance Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK-2) cells, obtained from the ATCC (21, 44), were grown in Eagle's minimal essential medium (MEM) with Earle's balanced salt solution (BSS) and 2 mM l-glutamine supplemented with 10% FBS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.1 mM NEAA, and 1.5 g of sodium bicarbonate per liter. A low-passage, highly polarized subclone of the MDCK cell line (MDCK-1), kindly supplied by Lennart Svensson (Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden), was propagated in DMEM with high glucose (4,500 mg/ml) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM HEPES, and 1 mM l-glutamine as described (57). All media were supplemented with penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). All cell lines were grown in 75-cm2 tissue culture flasks (Corning Costar Corp., Cambridge, Mass.) and maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator (Forma Scientific, Inc., Marietta, Ohio).

For viral infection studies, cells were seeded at a density of 10,000 to 20,000 per cm2 on tissue culture-treated polyester Transwell-Clear filters (diameter, 6.5 mm) containing pores of 0.4 μm (catalog no. 3470) or 3.0 μm (catalog no. 3472) in diameter (Corning Costar Corp). MA104, CCD-18, HEK 293T, MDCK-1, and MDCK-2 cells became confluent after 2 to 4 days, while Caco-2, HT-29, and T-84 cells became confluent after 4 to 6 days. The medium (0.2 ml in the insert and 0.9 ml in the well) was replaced every 2 to 3 days. Rotavirus infections were performed on 5- to 6-day-old MA104, CCD-18, HEK 293T, MDCK-1 or MDCK-2 cells, or 14- to 16-day-old MA104, Caco-2, HT-29 or T-84 cells. At the time of rotavirus infection, confluent 5- to 6-day-old MA104, CCD-18, or HEK 293T cell monolayers contained approximately 5 × 104 to 7.5 × 104 cells per insert, while Caco-2, HT-29, T-84, MDCK-1, MDCK-2, and 14- to 16-day-old MA104 cell monolayers contained approximately 4.5 × 105 to 8 × 105 cells per insert.

TER and permeability measurements.

The integrity of cell monolayers was assessed by measurements of TER and permeability of the monolayers to [3H]inulin. The TER displayed by filters containing cells in cell culture medium was measured with a Millicell-ERS resistance apparatus (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) at 0, 6, 10, 18, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h postinoculation (hpi). The background resistance of membranes without cells was 108 to 130 Ω. The net TER was calculated by subtracting the background and multiplying the resistance (Ω) by the area (0.33 cm2) of the filter and expressed as Ω times square centimeter. At the time of rotavirus infection, the TER of all epithelial cells was measured, and for all experiments, only intact polarized cell monolayers with a net resistance of >200 Ω × cm2 (14- to 16-day-old MA104 cells), >250 Ω × cm2 (MDCK-2 cells), >600 Ω × cm2 (HT-29 cells), >900 Ω × cm2 (Caco-2 cells), >2,500 Ω × cm2 (T-84 cells), or >5,000 Ω × cm2 (MDCK-1 cells) were used. Confluent CCD-18, HEK 293T, or 5- to 6-day-old MA104 cells did not become polarized, as evidenced by a net resistance of <5 Ω × cm2.

For measurements of monolayer permeability, duplicate cell monolayers were grown to confluence on filters, and 2.5 μCi of [3H]inulin (5,000 Da) (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.) was added to the medium in the basolateral chamber. Apical and basolateral fluid samples (10 μl) were taken at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 10, 18, 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h after initial addition of [3H]inulin. Samples taken from apical and basolateral chambers were counted by using a Beckman LS 3801 scintillation counter (Beckman Instruments, Inc., Fullerton, Calif.), and [3H]inulin diffusion was calculated as the percentage of total [3H]inulin initially present in the apical chamber. A rate of [3H]inulin diffusion of less than 1% per h across the membrane of the insert was considered indicative of intact junction complexes between polarized cells (61). Diffusion of [3H]inulin across membranes in the absence of cells was >50% by 6 h.

Transmission EM.

To determine if cells grown on the polyester Transwell-Clear filters containing pores of 0.4 or 3.0 μm in diameter migrated through the pores of the filter, and to determine if differential morphological changes occurred following apical or basolateral infection with 10 FFU per cell of SA-dependent or SA-independent rotavirus strains, cells were fixed and processed for transmission electron microscopy (EM) analysis as described (17, 57) with some modifications. Briefly, cell monolayers were fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) for 1 h at 4°C. Following two washes with 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, the cells were postfixed in 1% OsO4 in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer for 1 h. Cells were then dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol, subjected to two changes of propylene oxide (C3H6O), one change of 1:1 propylene oxide-Epon resin 828 (Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, Pa.), and one change in Epon resin 828, and embedded in Spurr's resin. Subsequently, silver sections (60 to 90 nm thick) were cut on an RMC 6000XL microtome (Research & Manufacturing Corp., Cocoa, Fla.) and stained with 0.025% uranyl acetate–lead citrate before examination in a Hitachi H7000 transmission electron microscope.

Viruses.

SA-dependent simian RRV (P5B[3], G3), SA11 Cl3 (P5B[2], G3), equine H-1 (P9[7], G5), bovine NCDV (P6[1], G6), and porcine OSU (P9[7], G5), SA-independent human Wa (P1A[8], G1), HAL1166 (P11[14], G8), PA169 (P11[14], G6), equine H-2 (P4[12], G3), lapine ALA (P11[14], G3), and bovine WC3 (P7[5], G6) rotavirus strains, and the SA-independent SA11 Cl3 rotavirus variant 954/23R (SA11 954/23R) strain (5) were plaque purified three times and propagated in embryonic rhesus monkey kidney MA104 cells in the presence of trypsin as described previously (5). Virus titers were determined by focus fluorescent assay (FFA) and expressed as focus-forming units per milliliter (5).

Rotavirus infection.

Prior to infection of cells, rotaviruses were treated with 10 μg of porcine trypsin (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Lakewood, N.J.) per ml for 30 min at 37°C. Cells grown on polyester Transwell-Clear filters containing pores of 0.4 or 3.0 μm in diameter were inoculated apically or basolaterally with SA-dependent or SA-independent rotavirus strains at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 or 10 FFU per cell. Inocula placed on either side of the membrane filter contained identical quantities of virus. After virus adsorption for 1 h at 37°C, the inoculum was removed, and the cells were washed with medium and then incubated for 18 to 24 h at 37°C with the corresponding medium in the presence of 0.5 μg of trypsin per ml, crystallized twice, dialyzed against 1 mM HCl, and lyophilized (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Lakewood, N.J.). The specific activity of the trypsin preparation used was ≥180 p-toluenesulfonyl-l-arginine methyl ester (TAME) units per mg of trypsin. Cells were fixed at 0, 6, 10, 18, 24, 48, 72, or 96 hpi with cold methanol. Rotavirus antigen was stained with a rotavirus-specific rabbit polyclonal hyperimmune serum followed by fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (Ig) antibody (Sigma Chemical Co.) and examined by immunofluorescence as described (5) using an Olympus IX70 microscope (Olympus America, Inc., Lake Success, N.Y.).

Neuraminidase treatment of cells and detection of SA residues with lectin.

In some cases, cells grown on the polyester Transwell-Clear filters containing pores of 0.4 or 3.0 μm in diameter were treated for 1 h at 37°C with 100 μl (apical chamber) or 500 μl (basolateral chamber) of 40-mU/ml neuraminidase from Arthrobacter ureafaciens purified by affinity chromatography (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) or with Tris-sodium-calcium (TNC) buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 140 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2) as a control as described (5). Following treatment with neuraminidase, cells were washed with medium prior to apical or basolateral infection of cells with SA-dependent or -independent rotavirus strains at an MOI of 1 or 10 FFU per cell as detailed above. Viral infectivity was expressed as the number of FFU in neuraminidase-treated cells as a percentage of the number in control (TNC buffer treated) cells.

Virus release curves.

Duplicate cell monolayers grown on the polyester Transwell-Clear filters containing pores of 0.4 μm in diameter were infected apically or basolaterally with SA-dependent or -independent rotavirus strains at an MOI of 1 or 10 FFU per cell or mock infected with medium as detailed above. Apical or basolateral cell culture media from cells were collected at 0, 6, 12, 18, 24, 48, 72, and 96 hpi. The cell-associated virus was removed from cells by two cycles of freeze-thawing, the cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 900 × g, and virus titers present in this supernatant and the media collected from the apical and basolateral chambers were determined by FFA on confluent MA104 cell monolayers grown on 96-well plates (Corning Costar Corp.). Virus titers were expressed as FFU/ml (5). When fluorescent foci in 1:10 dilutions could not be visualized by fluorescent microscopy, the samples were considered negative, and a value of 50 FFU/ml was arbitrarily assigned.

Cell viability measurements.

Apically or basolaterally rotavirus- or mock-infected duplicate cell monolayers grown on the polyester Transwell-Clear filters containing pores of 0.4 μm in diameter were monitored for desquamation and viability as described (31, 57) with modifications. Briefly, the desquamated cells present in the apical or basolateral medium collected at 0, 6, 12, 18, 24, 48, 72, and 96 hpi were pelleted by centrifugation at 900 × g and suspended in serum-free medium containing 0.08% trypan blue (Sigma Chemical Co). To determine the percentage of desquamated cells, the cells attached to the membrane were suspended in 0.25% trypsin–1 mM disodium EDTA (Gibco-BRL), centrifuged at 900 × g, and then suspended in serum-free medium containing 0.08% trypan blue. Total and stained cell counts were made by using a hemacytometer.

Detection of SA residues.

The presence of SA residues on either the apical or basolateral surface of cells grown on the polyester Transwell-Clear filters containing pores of 0.4 or 3.0 μm in diameter was determined by using a Texas Red-conjugated lectin, wheat germ agglutinin (WGA), which binds SA residues and N-acetylglucosaminyl residues (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, Oreg.). Duplicate cell monolayers grown on filters were washed with medium, and WGA-conjugated to Texas Red placed in serum-free medium (5 μg/ml) was added apically or basolaterally for 20 min. Following a single wash with medium, cells were observed for fluorescence of cellular SA residues in an Olympus IX70 microscope (Olympus America, Inc.). Apical-to-basolateral or basolateral-to-apical passage of WGA across 0.4-μm pore-filter membranes in the absence of cells was >80% in 20 min, as measured by spectrometry.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 7.5 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Ill.). Differences in virus titers, TER, percent [3H]inulin diffusion, and cell viability measurements were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis followed by the Mann-Whitney U test. Trend analysis was performed by linear regression, and correlation coefficients were calculated by Pearson's correlation coefficients. Comparisons with a P value of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Epithelial cells migrate through and grow on the opposite face of 3.0-μm but not 0.4-μm membrane filters. To begin studying the site of rotavirus entry in different epithelial cells, polarized Caco-2, HT-29, T-84, MDCK-1, and MDCK-2 or nonpolarized HEK 293T and CCD-18 epithelial cells were grown on membrane filters containing 3.0- or 0.4-μm pores to gain access to the basolateral or lower domain of the plasma membrane of polarized and nonpolarized cells, respectively. MA104 cells, which were not known to be polarized in culture, were also examined. The integrity and polarization of cell monolayers grown on the two types of permeable supports were assessed by EM analysis and TER or permeability measurements to determine the most suitable type of membrane filter for our studies.

As reported by others (60), EM analysis revealed that all epithelial cell lines tested grew on both faces of the membrane filters containing 3.0-μm pores (data not shown). Caco-2, HT-29, T-84, MDCK-1, and MDCK-2 cells but not HEK 293T or CCD-18 cells exhibited junctional complexes indicative of a polarized epithelium (data not shown). Unlike MDCK-1 or MDCK-2, Caco-2, HT-29, and T-84 cells that grew on the opposite face of the filter appeared to have a more flattened morphology with fewer and smaller, if any, microvilli than cells growing on the upper face of the filter (data not shown). However, both cell populations exhibited junctional complexes (data not shown), suggesting that the cells on the lower face of the filter were polarized.

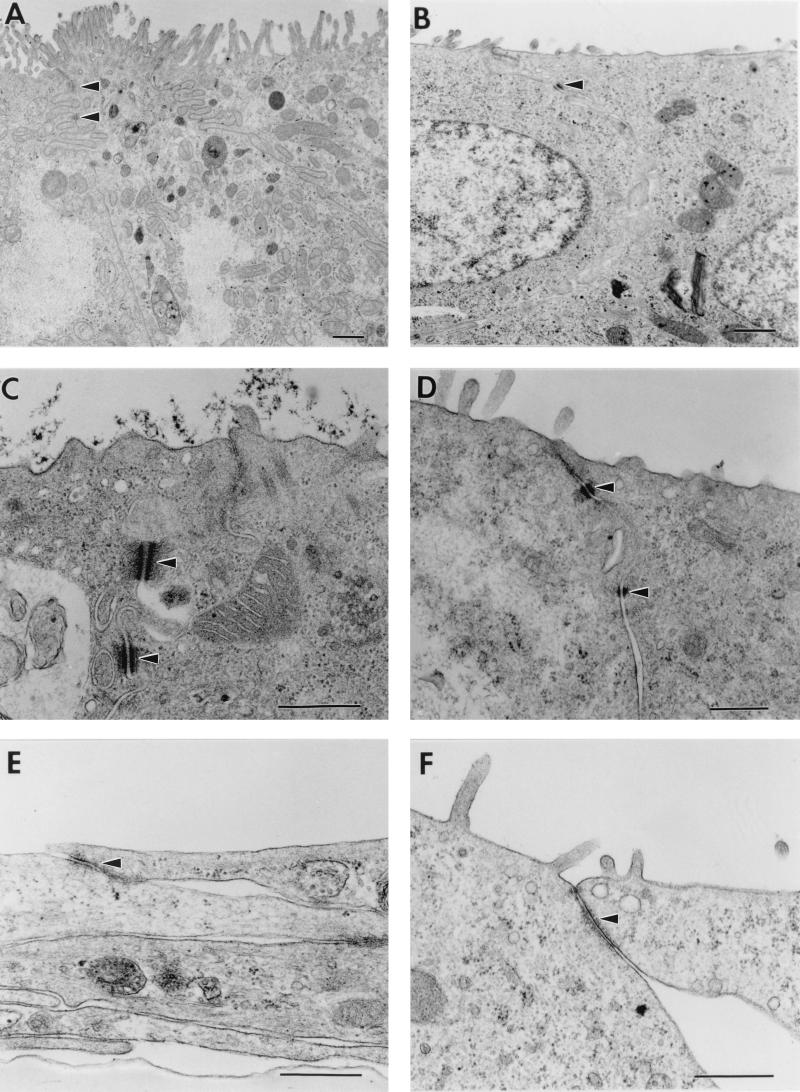

None of the epithelial cells grown on 0.4-μm-pore membrane filters grew on the opposite face of the membrane filter (data not shown). Similar to when cells were grown on 3.0-μm-pore membrane filters, Caco-2, HT-29, T-84, MDCK-1, and MDCK-2 cells but not HEK 293T or CCD-18 cells exhibited junctional complexes indicative of a polarized epithelium (Fig. 1 and data not shown). Although there are a number of well-established epithelial cell lines of renal origin that exhibit characteristics of differentiated tissues (62), MA104 cells, widely used to grow rotavirus in culture, had not been described to exhibit typical features of the polarized renal epithelium. In fact, when MA104 cells were grown for 5 to 6 days on membrane filters containing 3.0- or 0.4-μm pores, there was no evidence of junctional complexes between adjacent cells (data not shown). However, when MA104 cells obtained from either Microbiological Associates or ATTC were further grown for 14 to 16 days, the cells formed domes (data not shown), exhibited junctional complexes indicative of a polarized epithelium (Fig. 1E and 1F), and developed microvilli (Fig. 1F). Thus, MA104 cells possess the capability of becoming polarized in culture if grown for 2 weeks.

FIG. 1.

Electron micrographs of polarized intestinal Caco-2 (A), HT-29 (B), and T-84 (C) and polarized kidney MDCK-1 (D) and MA104 (E and F) cells. Cells were grown on permeable supports containing 0.4-μm pores. Intestinal Caco-2, HT-29, and T-84 cells exhibit an enterocyte-like appearance, with an apical brush border, microvilli, and typical tight junctions and desmosomes (arrows). Kidney MDCK-1 and MA104 cells show evidence of some microvilli along the apical surface typical of the polarized renal epithelium, and tight junctions and junctional complexes, respectively (arrows). Bars, 0.5 μm. Original magnifications: ×13,000 (A), ×16,000 (B), ×40,000 (C, E, and F), and ×32,000 (D).

As with all other epithelial cell lines tested, MA104 cells grown on 3.0-μm-pore but not 0.4-μm-pore membrane filters grew through the pores (data not shown). TER measurements of cells grown on membrane filters containing 0.4-μm pores also indicated that Caco-2, HT-29, T-84, MDCK-1, MDCK-2, and 14- to 16-day-old MA104 cells but not HEK 293T, CCD-18, or 5- to 6-day-old MA104 cells were polarized (data not shown). Caco-2, HT-29, T-84, MDCK-1, MDCK-2, and MA104 cells grown on 3.0-μm-pore membrane filters for 14 to 16 days also developed TER measurements indicative of polarized epithelium; however, TER measurements were about 30% less than those obtained when the cells were grown on 0.4-μm-pore membrane filters (data not shown).

SA-independent rotavirus strains infect polarized epithelial cells at the apical and basolateral membrane, while SA-dependent rotavirus strains preferentially infect polarized epithelial cells at the apical domain of the plasma membrane.

An earlier report (57) determined that RRV, an SA-dependent rotavirus strain, infects polarized Caco-2 and MDCK-1 epithelial cells grown on membrane filters containing 3.0-μm pores in a symmetric manner, by either the apical or basolateral plasma membrane domains. Our finding that epithelial cells migrate through and grow on the opposite face of membrane filters containing 3.0-μm pores prompted us to reexamine the entry pattern of both SA-independent and SA-dependent rotavirus strains into different polarized epithelial cells grown on membrane filters containing 0.4-μm pores. SA-independent and SA-dependent rotaviruses were allowed to adsorb to either the apical or basolateral surface of polarized 14- to 16-day-old MA104, MDCK-2, MDCK-1, Caco-2, HT-29, and T-84 cells. Nonpolarized 5- to 6-day-old MA104, CCD-18, and HEK 293T cells were used as control cell monolayers.

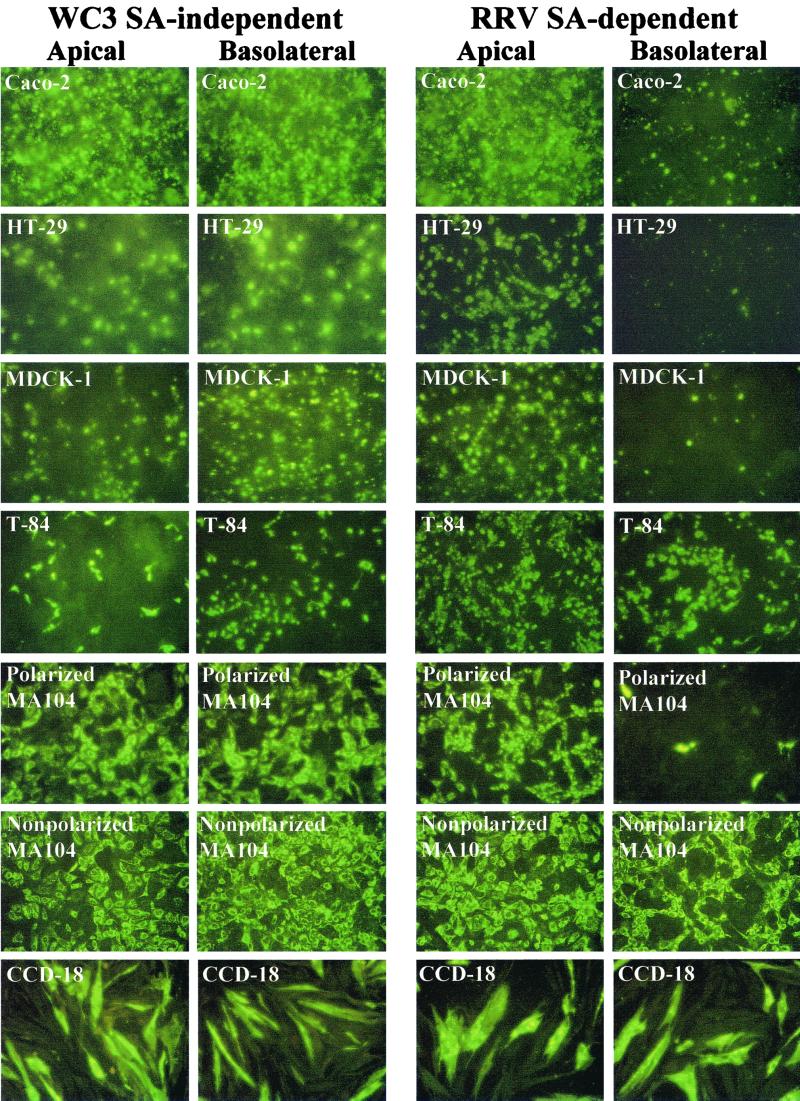

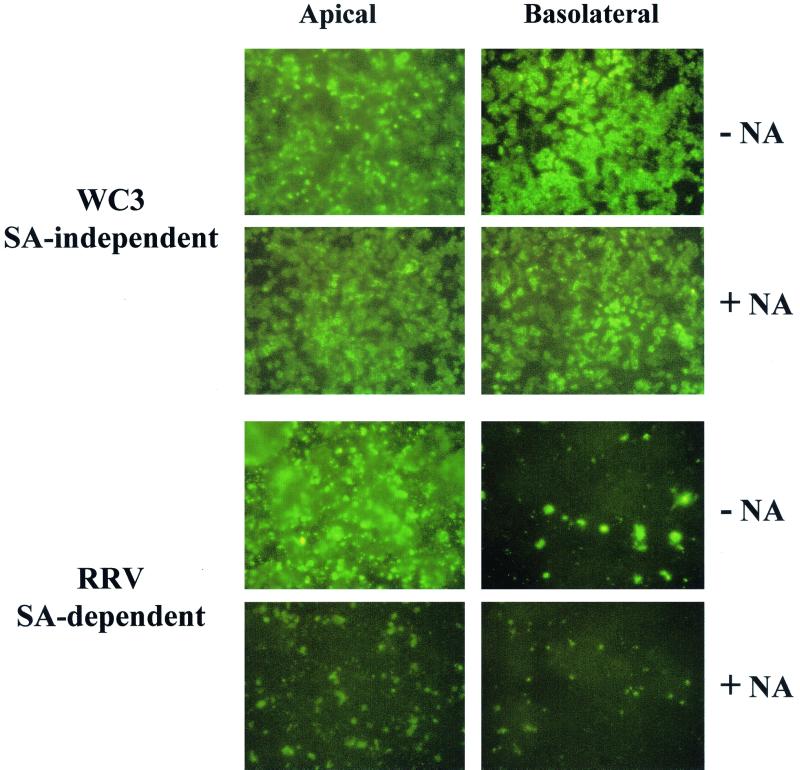

The ability of rotavirus to infect cells through the apical or the basolateral domain of the plasma membrane was determined by immunofluorescence, and the multiplicity of infection did not affect the results. Rotavirus infection of polarized cell monolayers with WC3, an SA-independent strain, resulted in a nonpolar (symmetric) infection of polarized Caco-2, HT-29, MDCK-1, MDCK-2, and 14- to 16-day-old MA104 cells, while infection with RRV, an SA-dependent strain, proceeded much more efficiently through the apical domain of the plasma membrane than through the basolateral membrane domain of the indicated polarized epithelial cells (Fig. 2 and data not shown). Nonpolarized CCD-18, HEK 293T, and 5- to 6-day-old MA104 epithelial cells were infected equally from both the upper and lower domains by both SA-independent WC3 and SA-dependent RRV strains (Fig. 2 and data not shown). Interestingly, both RRV and WC3 infected polarized intestinal T-84 cells from either the apical or the basolateral surface, although infection with RRV was more prominent (≥30%) at the apical surface than at the basolateral surface. In turn, WC3 infection was more efficient (≥50%) at the basolateral surface of T-84 cells than at the apical surface (Fig. 2). Following basolateral and apical infection of T-84 cells with WC3, ≥7.5 × 103 and ≤1.25 × 103 FFU were detected, respectively (data not shown). Similar patterns of infection were obtained with SA-independent human (Wa, HAL1166, and PA169), equine (H-2), and lapine (ALA), SA-independent simian variant SA11 Cl3 954/23R, and SA-dependent simian (SA11 Cl3), equine (H-1), bovine (NCDV), and porcine (OSU) rotavirus strains in all polarized and nonpolarized epithelial cells tested (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Immunofluorescence analysis of the infectivity of SA-independent (WC3) and SA-dependent (RRV) rotavirus strains inoculated apically or basolaterally with 10 FFU per cell onto polarized Caco-2, HT-29, T-84, MDCK-1, and MA104 and nonpolarized MA104 and CCD-18 epithelial cells grown on permeable supports containing 0.4-μm pores. At 24 hpi, the monolayers were fixed with methanol, stained for viral antigen with a rotavirus-specific rabbit polyclonal hyperimmune serum followed by fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-rabbit Ig antibody, and examined by immunofluorescence.

SA-independent and SA-dependent rotavirus strains are released almost exclusively from the apical membrane domain of polarized intestinal Caco-2 and HT-29 cells.

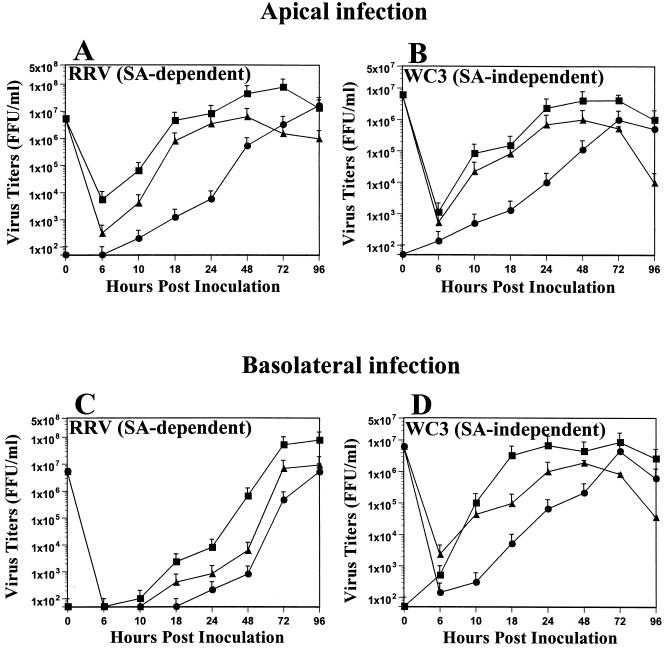

Since Jourdan et al. (31) reported that strain RRV is released from the apical surface of cultured human intestinal cells through nonconventional vesicular transport that bypasses the Golgi apparatus, we next examined whether the WC3 and RRV strains would be released in a polarized fashion. We examined the yields of progeny virus obtained at various time points after apical or basolateral infection of polarized Caco-2 and HT-29 cells with WC3 or RRV by determining the virus titers in the apical and basolateral culture medium (released virus) and inside the cells (intracellular virus not yet released). Our results show that, regardless of the route of entry, both WC3 and RRV were preferentially released from the apical domain of the plasma membrane of polarized Caco-2 cells, and virus release was first detected at 10 hpi (Fig. 3). Concurrent with the decreased infection efficiency of RRV through the basolateral surface of Caco-2 cells, apical release of RRV was delayed (Fig. 3C) in comparison to the apical release of RRV from apically infected Caco-2 cells (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

Comparison of yields of progeny of SA-dependent strain RRV and SA-independent strain WC3 in Caco-2 cells inoculated apically or basolaterally with RRV (A and C) or WC3 (B and D) at an MOI of 10 FFU per cell. Caco-2 cell monolayers displayed a TER of >900 Ω × cm2 prior to infection. At the indicated time points, Caco-2 cells (▴) and apical (▪) and basolateral (●) supernatant culture media were collected separately, and virus titers were determined by FFA (5). Values shown are arithmetic means of at least three independent experiments. Error bars represent 1 standard error of the mean.

Examination of Caco-2 cells infected apically or basolaterally with WC3 cells revealed that basolaterally infected cells (Fig. 3D) produced significantly (P < 0.03, Mann-Whitney U) higher virus titers at 10, 18, and 24 hpi than apically infected cells at the same time points (Fig. 3B). At 24 hpi, ≥95% of the released virus was found in the apical chamber of Caco-2 cells infected apically or basolaterally with RRV or WC3 (Fig. 3). By 72 and 96 hpi, almost the same quantities of virions were detected in the apical and basolateral chambers of RRV- and WC3-infected Caco-2 cells (Fig. 3). Similar results were obtained with polarized HT-29 cells infected apically or basolaterally with WC3 and RRV (data not shown). At 24 hpi, the yield of virus progeny of the apical and basolateral medium obtained following apical or basolateral WC3 or RRV infection of 5- to 6-day-old nonpolarized MA104 cells was 2.3 × 106 to 5.6 × 106 FFU/ml (data not shown).

To directly examine virus replication or production, intracellular virus antigen on duplicate polarized Caco-2 cells inoculated apically or basolaterally with WC3 or RRV was identified by immunofluorescence at 0, 6, 10, 18, 24, 48, 72, and 96 hpi. Immunofluorescence analysis indicated that the percentage of cells producing WC3 virus antigen in Caco-2 cells inoculated apically or basolaterally reached near maximum levels by 24 hpi, although additional cells exhibited antigen expression at later time points (Table 1). A similar pattern of virus antigen production was observed when Caco-2 cells were inoculated apically with RRV, but production of RRV antigen was significantly reduced (P < 0.001, Mann-Whitney U) at all time points measured when the cells were inoculated basolaterally with RRV (Table 1). By 72 hpi, only 55% of Caco-2 cells inoculated basolaterally with RRV were expressing RRV antigen, while 97% of Caco-2 cells inoculated apically with RRV were RRV antigen positive (Table 1). Virus antigen production patterns of WC3 and RRV as well as additional SA-dependent (SA11 Cl3, OSU, H-1, and NCDV) and SA-independent (Wa, HAL1166, PA169, H-2, ALA, and SA11 Cl3 954/23R) rotavirus strains tested in HT-29 cells were similar to those obtained in Caco-2 cells (data not shown). At 24 hpi, approximately 80 to 100% of the 5- to 6-day-old nonpolarized MA104 cell monolayers were rotavirus antigen positive regardless of the site of WC3 or RRV inoculation (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of CPE, percent infected cells, cell desquamation, and viability in polarized Caco-2 epithelial cells grown on membrane filters containing 0.4-μm pores and inoculated apically or basolaterally at an MOI of 10 FFU per cell with bovine WC3 (SA-independent) and simian RRV (SA-dependent) rotavirus strainsa

| Infection route and time (hpi) | CPEa | WC3 (SA independent)

|

RRV (SA dependent)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Infected cellsb | % Desquamated cellsc | % Cell viabilityd

|

CPE | % Infected cells | % Desquamated cells | % Cell viability

|

||||

| On filter | In suspension | On filter | In suspension | |||||||

| Apical | ||||||||||

| 0 | − | 0 | 14 (± 4) | >99 | >99 | − | 0 | 14 (± 6) | >99 | >99 |

| 6 | − | 6 (± 2) | 16 (± 4) | 97 | >99 | − | 11 (± 3) | 15 (± 4) | 96 | 97 |

| 10 | − | 28 (± 3) | 17 (± 6) | 95 | 98 | − | 34 (± 2) | 16 (± 4) | 95 | 94 |

| 18 | − | 71 (± 3) | 14 (± 5) | 90 | 91 | − | 79 (± 4) | 18 (± 6) | 91 | 91 |

| 24 | − | 83 (± 4) | 19 (± 3) | 88 | 81 | − | 91 (± 3) | 20 (± 7) | 87 | 85 |

| 48 | + | 94 (± 3) | 30 (± 11) | 68 | 71 | + | 95 (± 2) | 35 (± 10)* | 65 | 69 |

| 72 | ++ | 97 (± 1) | 49 (± 12) | 54 | 59 | +++ | 97 (± 2) | 54 (± 12) | 48 | 49 |

| 96 | +++ | 97 (± 1) | 65 (± 12) | 37 | 40 | ++++ | 97 (± 1) | 71 (± 12) | 33 | 34 |

| Basolateral | ||||||||||

| 0 | − | 0 | 15 (± 6) | >99 | >99 | − | 0 | 16 (± 4) | >99 | >99 |

| 6 | − | 10 (± 3) | 16 (± 6) | 98 | 97 | − | 0 | 15 (± 5) | >99 | >99 |

| 10 | − | 32 (± 3) | 17 (± 5) | 93 | 95 | − | 0 | 13 (± 6) | >99 | 98 |

| 18 | − | 80 (± 4) | 16 (± 6) | 90 | 91 | − | 2 (± 1) | 18 (± 4) | 97 | 98 |

| 24 | +/− | 89 (± 2) | 22 (± 8) | 79 | 80 | − | 13 (± 2) | 19 (± 4) | 94 | 95 |

| 48 | ++ | 95 (± 3) | 36 (± 9) | 54 | 65 | − | 27 (± 3) | 18 (± 7) | 91 | 89 |

| 72 | +++ | 98 (± 1) | 56 (± 13) | 44 | 43 | +/− | 55 (± 4) | 36 (± 10) | 81 | 78 |

| 96 | ++++ | 99 (± 1) | 73 (± 12) | 28 | 25 | + | 77 (± 5) | 50 (± 9) | 66 | 69 |

CPE was determined by inspection of nonstained monolayers from at least 10 separate filters. CPE was scored according to the following scale: −, 0%; +/−, 0 to 10%; +, 10 to 30%; ++, 30 to 50%; +++, 50 to 75%; ++++, >75%. Mock-inoculated Caco-2 cell monolayers did not develop any apparent CPE throughout the experiments.

Values are arithmetic means (± standard error of the mean) from at least three independent experiments. Infected Caco-2 cells were fixed with cold methanol, stained for intracellular rotavirus antigen with a rotavirus-specific rabbit polyclonal hyperimmune serum followed by fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-rabbit Ig, antibody, and examined by immunofluorescence.

Monolayer integrity was assessed by numeration of desquamated cells present in mock-inoculated and virus-infected cells and expressed as a percentage of desquamated cells. Values are arithmetic means (± standard error of the mean) from at least three independent experiments. Percent desquamated mock-inoculated Caco-2 cells ranged from 15% ± 5% to 23% ± 5% (0 to 96 hpi, respectively). A significant (P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U) difference in percent desquamated Caco-2 cells infected apically with respect to those infected basolaterally at a given point is indicated by an asterisk.

Cell viability is expressed as percent total live cells on membrane filter and in suspension. Caco-2 cells present in the apical medium, collected at indicated time points, were pelleted by centrifugation at 900 × g, suspended in serum-free medium containing 0.08% trypan blue (Sigma Chemical Co), and counted using a hemacytometer. Cells attached to the membrane filter were suspended in 0.25% trypsin–1 mM disodium EDTA (Gibco-BRL), centrifuged at 900 × g, and then suspended in serum-free medium containing 0.08% trypan blue before counting the cells with a hemacytometer.

SA-independent and SA-dependent rotaviruses are released from the apical surface of Caco-2 cells before cell lysis and monolayer disruption.

We also investigated monolayer integrity by cell desquamation and cell viability following apical or basolateral WC3 and RRV infection of polarized Caco-2 and HT-29 and nonpolarized 5- to 6-day-old MA104 cells. There was no significant change (P > 0.321, Mann-Whitney U) in monolayer integrity within the first 24 hpi in Caco-2 cells infected apically or basolaterally with either WC3 or RRV (Table 1). However, cell desquamation in cells infected apically and basolaterally with WC3 or only apically with RRV increased significantly (P < 0.02, Mann-Whitney U) by 48 hpi with respect to mock-inoculated cells (Table 1). The percentage of desquamated cells increased steadily (P < 0.01, r2 = 0.99, linear regression) from 48 to 96 hpi.

In addition, Table 1 shows that, although nearly all Caco-2 cells inoculated apically with RRV and apically or basolaterally with WC3 at 24 hpi (Fig. 2) were infected, cytopathic effect (CPE) was almost absent. The CPE appeared late and was characterized by rounding and enlargement of cells, accompanied by cell detachment from the membrane filters. The CPE was not clearly evident until 72 and 96 hpi. The CPE was even more delayed in Caco-2 cells infected basolaterally with RRV. Similar CPE results were observed in polarized HT-29 cells (data not shown). In spite of the efficient virus replication observed at 24 hpi, the majority (≥79%) of the cells on the membrane filter or in suspension were alive, as determined by trypan blue dye exclusion (Table 1). Although the reason for the prolonged viability exhibited by rotavirus-infected polarized cells is not understood, polarized epithelial cells are more resistant to CPE than nonpolarized cells (31, 55, 57). Altogether, these data confirm that WC3 and RRV are released from the apical surface of Caco-2 cells before cell lysis and monolayer disruption.

Transmission EM analysis of polarized Caco-2, HT-29, and MA104 cells infected apically with the SA-dependent SA11 Cl3 strain revealed (i) moderate to marked (Caco-2 and HT-29 cells) or mild (MA104 cells) cytoplasmic vacuolization (evident as early as 10 hpi and lasting until 48 or 72 hpi), (ii) relocation of the nucleus, and (iii) gradual disappearance of the tight junctions beginning at 10 hpi (MA104 cells) or 24 hpi (Caco-2 and HT-29 cells) and progressing until complete disappearance by 48 or 72 hpi (data not shown). Vacuolization, relocation of the nucleus, and gradual disappearance of the junctional complexes of polarized Caco-2, HT-29, and MA104 cells infected basolaterally with 10 FFU per cell of the SA-dependent rotavirus strain were delayed and did not appear until 48 hpi (MA104) or 72 hpi (Caco-2 and HT-29) (data not shown). Apical or basolateral infection of polarized Caco-2, HT-29 and MA104 cells with the SA-independent SA11 Cl3 954/23R variant rotavirus strain did not reveal morphological differences related to the route of virus entry, as vacuolization, relocation of the nucleus, and gradual disappearance of the junctional complexes occurred simultaneously at the same time intervals as these changes appeared in cells infected apically with the SA-dependent rotavirus strain (data not shown). Unlike Jourdan et al. (31), we observed no or few released (free) extracellular progeny viruses scattered between microvilli and brush border (data not shown), but the pathway that results in the apical release of rotaviruses requires further study.

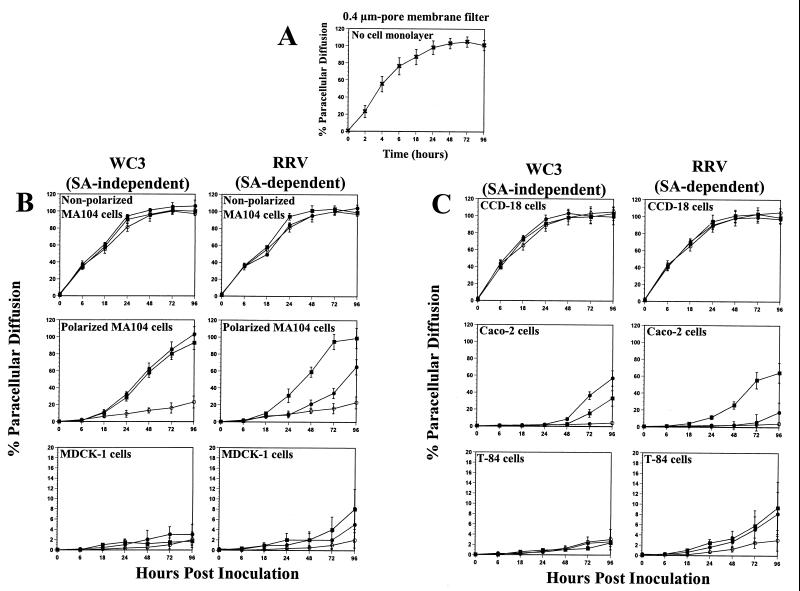

SA residues are primarily detected on the apical domain of the plasma membrane of polarized epithelial cells.

The distinct SA-independent and SA-dependent rotavirus patterns of entry in the different polarized cells tested might be related to the level of expression of specific viral receptors, including SA residues, present on the apical or the basolateral domain of the plasma membrane. To determine if the distribution of SA residues on polarized epithelial cells grown on 0.4-μm-pore membrane filters correlates with the pattern of entry of SA-dependent rotavirus strains, we used WGA conjugated to Texas Red to visualize the pattern of SA residue staining by fluorescence microscopy.

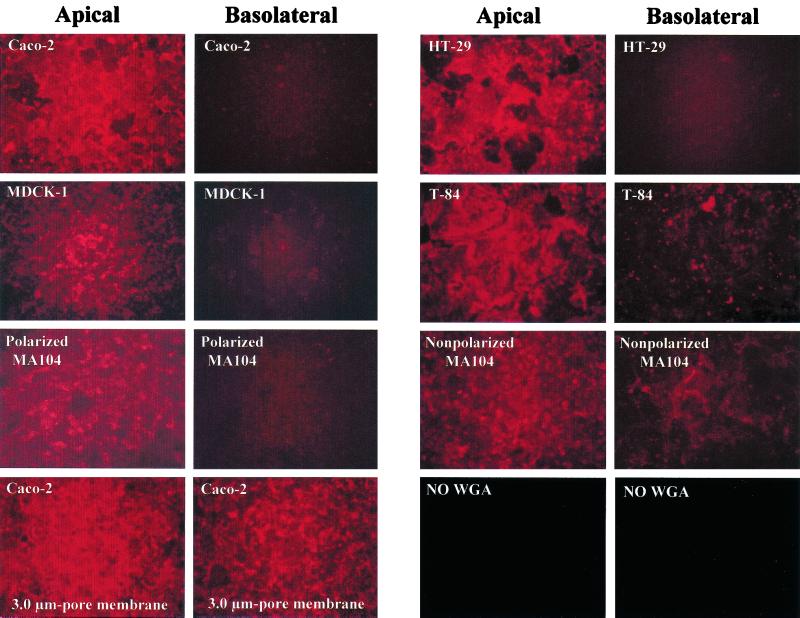

SA residue staining with WGA conjugated to Texas Red was primarily detected on the apical plasma membrane domain but limited or absent on the basolateral membrane domain of polarized Caco-2, HT-29, MDCK-1, and MA104 cells (Fig. 4) and MDCK-2 cells (data not shown). SA residue staining was stronger on the apical than on the basolateral surface of polarized T-84 cells, but the SA residue staining on the basolateral surface of polarized T-84 cells was greater than that observed on the basolateral surface of polarized Caco-2, HT-29, MDCK-1, and MA104 cells (Fig. 4). Nonpolarized MA104, HEK 293T, and CCD-18 possessed a more uniform distribution of SA residues on both the upper and lower surfaces (Fig. 4 and data not shown). Therefore, SA residues are mainly present on the apical surface of polarized epithelial cells and in both the upper and lower surfaces of nonpolarized cells, although proper quantification of the distribution of SA residues on apical versus basolateral cell surfaces would be necessary.

FIG. 4.

Detection of SA residues of polarized Caco-2, HT-29, T-84, MDCK-1, and MA104 and nonpolarized MA104 epithelial cells grown on permeable supports containing 0.4-μm pores, using a Texas Red-conjugated lectin, WGA. WGA (5 μg/ml) was added apically or basolaterally to cells, incubated for 20 min at 37°C, and washed before SA residue staining was visualized by fluorescence. The bottom left panels show the SA residue staining pattern in polarized Caco-2 cells grown on permeable supports containing 3.0-μm pores as the result of cells migrating through these large pores and growing on the opposite face of the membrane filter. Similar SA residue staining was detected when polarized HT-29, T-84, MDCK-1, and MA104 cells were grown on membrane filters containing 3.0-μm pores (data not shown). Background SA residue staining of Caco-2 cells grown on permeable supports containing 0.4-μm pores when no WGA was applied is also shown (bottom right panels).

Our results indicate that the localization of SA residues on cell monolayers correlates with the ability of SA-dependent rotaviruses to infect efficiently through the apical but not the basolateral surface of polarized Caco-2, HT-29, MDCK-1, MDCK-2, and MA104 cells. In addition, SA residues were detected on both faces of the membrane filters when polarized Caco-2, HT-29, T-84, MDCK-1, MDCK-2, and MA104 cells were grown on 3.0-μm-pore membrane filters (Fig. 4 and data not shown), possibly because the cells that grow through the 3.0-μm pores form a polarized monolayer on the lower surface of the filter (60).

SA residues on the apical domain of the plasma membrane of polarized epithelial cells are required for efficient infection of SA-dependent but not SA-independent rotavirus strains.

It is known that SA residues on the surface of nonpolarized MA104 cells are required for efficient binding and infectivity by SA-dependent but not SA-independent rotavirus strains (5, 41). Therefore, we next determined if the removal of SA residues with neuraminidase from the plasma membrane domains of polarized epithelial cells grown on membrane filters containing 0.4-μm pores would affect the infectivity of SA-dependent and SA-independent rotavirus strains.

As expected, removal of SA residues from the apical and basolateral membrane domains of polarized Caco-2 cells did not affect the infectivity of the SA-independent WC3 strain (Fig. 5). In contrast, removal of SA residues from the plasma membrane of polarized Caco-2 cells reduced the infectivity of the SA-dependent RRV strain at the apical but not basolateral surface (Fig. 5). In fact, removal of SA residues from both the apical and basolateral domains of the plasma membrane of polarized Caco-2 cells resulted in equally poor RRV infectivity levels.

FIG. 5.

Immunofluorescence analysis of the infectivity of SA-independent (WC3) and SA-dependent (RRV) rotavirus strains inoculated apically or basolaterally at 10 FFU per cell onto polarized Caco-2 epithelial cells grown on permeable supports containing 0.4-μm pores and treated with 40 mU of neuraminidase (Arthrobacter ureafaciens) per ml (+ NA) or mock-treated with TNC buffer (− NA) for 1 h at 37°C. At 24 hpi, the monolayers were fixed with methanol, stained for viral antigen with a rotavirus-specific rabbit polyclonal hyperimmune serum followed by fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-rabbit Ig antibody, and examined by immunofluorescence.

Similar results for WC3 and RRV infection were obtained when polarized HT-29, MDCK-1, and MA104 cells were treated with neuraminidase prior to infection of cells (data not shown). Removal of SA residues from the plasma membrane of polarized T-84 cells reduced the infectivity of the SA-dependent RRV strain at both the apical and basolateral domains (data not shown), indicating that the presence of small amounts of SA residues on the basolateral membrane domain of T-84 cells (Fig. 4) accounts for the basolateral infection of T-84 cells by the SA-dependent RRV strain. Neuraminidase treatment of nonpolarized 5- to 6-day-old MA104 cells resulted in a reduction in RRV but not WC3 infectivity in cells inoculated apically or basolaterally (data not shown). Similar infectivity results were obtained with SA-independent human (Wa) and lapine (ALA), SA-independent simian variant SA11 Cl3 954/23R, and SA-dependent simian (SA11 Cl3) and porcine (OSU) rotavirus strains in polarized Caco-2, HT-29, MDCK-1, and MA104 and nonpolarized MA104 epithelial cells (data not shown).

Since cells migrate or grow through the 3.0-μm pores and establish a polarized cell monolayer on the lower surface of the membrane filter, neuraminidase treatment of polarized Caco-2, MDCK-1, and MA104 cells grown on 3.0-μm-pore membrane filters resulted in a reduction of infectivity of the RRV strain but not the WC3 strain at both faces of the membrane filter (data not shown). Therefore, SA residues on cell membranes of polarized cells are required for efficient infection of SA-dependent but not SA-independent rotaviruses.

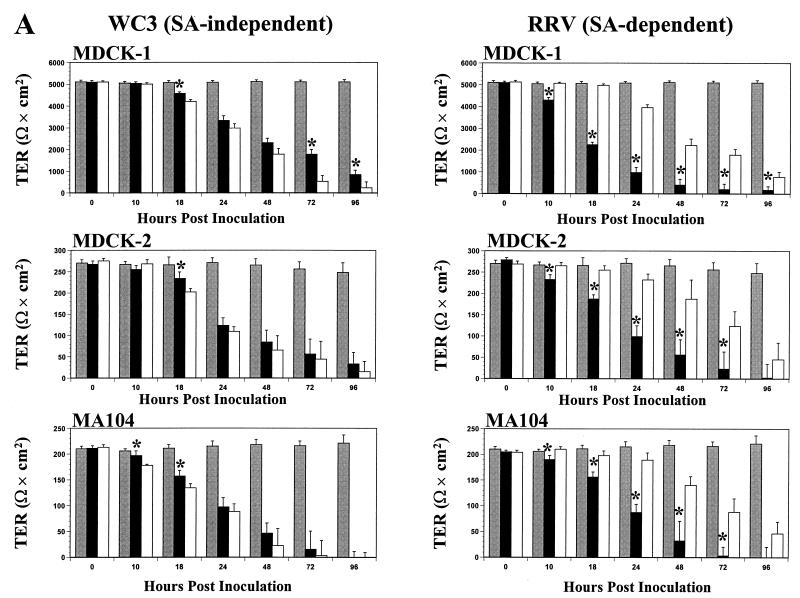

Changes in TER exhibit different kinetics depending on site of infection and rotavirus strain.

To determine the integrity of the junctional complexes that hold together the polarized epithelium, TER measurements were carried out in polarized MDCK-1, MDCK-2, MA104, Caco-2, HT-29, and T-84 cells grown on 0.4-μm-pore membrane filters, infected apically or basolaterally with 10 FFU per cell of SA-independent or SA-dependent rotavirus strains at various time points postinfection. Control cells were mock inoculated and monitored in a similar manner.

The TER measurements across the control mock-inoculated Caco-2 (>900 Ω × cm2), HT-29 (>600 Ω × cm2), T-84 (>2,500 Ω × cm2), MDCK-1 (>5,000 Ω × cm2), MDCK-2 (>250 Ω × cm2), and MA104 (>200 Ω × cm2) polarized monolayers remained constant (P > 0.821, Mann-Whitney U) for at least 96 hpi (Fig. 6). No significant decreases (P > 0.640, Mann-Whitney U) in TER measurements were noted at 6 hpi in any polarized cells infected apically or basolaterally with either SA-independent or SA-dependent rotavirus strains (data not shown). As early as 10 and 18 hpi, the TER of polarized renal MDCK-1, MDCK-2, and MA104 (Fig. 6A) and intestinal Caco-2 and HT-29 (Fig. 6B) epithelial cells infected apically or basolaterally with the SA-independent WC3 strain decreased simultaneously and significantly (P < 0.035, Mann-Whitney U). TER measurements continued to decrease simultaneously, and the rate of decline was linear (P < 0.011, r2 = 0.99, linear regression). By 96 hpi, TER measurements of the cell monolayers had either become zero or dropped dramatically (P < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney U). Similar results were obtained with additional SA-independent human (Wa, HAL1166, and PA169), lapine (ALA), and simian variant SA11 Cl3 954/23R rotavirus strains (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

TER of renal MDCK-1, MDCK-2, and MA104 polarized intestinal Caco-2, HT-29, and T-84 (A) and (B) epithelial cell monolayers grown on permeable supports containing 0.4-μm pores and mock inoculated (shaded bars) or inoculated apically (solid bars) or basolaterally (open bars) with 10 FFU per cell of the SA-independent rotavirus WC3 or SA-dependent RRV strain. The net TER was calculated by subtracting the background (membrane filter without cells) and multiplying the resistance (Ω) by the area (0.33 cm2) of the filter. TER measurements were taken at the indicated times. Each bar shows the arithmetic mean of at least three independent experiments. Error bars represent 1 standard error of the mean. A significant (P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U) difference in TER of cells infected apically with respect to those infected basolaterally at a given time point is indicated by an asterisk.

In contrast, a significant decrease (P < 0.021, Mann-Whitney U) in TER measurements was first observed at 10 hpi in polarized intestinal Caco-2 and HT-29 (Fig. 6B) and renal MDCK-1, MDCK-2, and MA104 (Fig. 6A) epithelial cells infected apically but not basolaterally with the SA-dependent RRV strain. At any given time point beyond 10 hpi, TER measurements of the cells infected apically with RRV decreased earlier and were significantly lower (P < 0.033, Mann-Whitney U) than those of cell monolayers infected basolaterally with RRV. Polarized cell monolayers infected basolaterally with RRV showed a slight drop in TER measurements beginning at 24 hpi. TER measurements continued to decline over time at a linear rate (P < 0.018, r2 = 0.99, linear regression), and by 96 hpi, the polarized monolayers infected apically or basolaterally had lost approximately 100 to 86% or 96 to 65%, respectively, of their resistance. At 96 hpi, TER measurements of all basolaterally RRV-infected cell monolayers except MA104 and MDCK-2 cells were still significantly higher (P < 0.033, Mann-Whitney U) than TER measurements of apically RRV-infected cell monolayers. Similar results were obtained with additional SA-dependent simian (SA11 Cl3), bovine (NCDV), and porcine (OSU) rotavirus strains (data not shown).

Thus, SA-dependent rotaviruses infected polarized Caco-2, HT-29, MDCK-1, MDCK-2, and MA104 cells in a polar (asymmetric) fashion, preferentially using the apical surface of the plasma membrane. Since efficient rotavirus infection decreases cellular TER before the appearance of CPE and considerable cell death (Table 1), these results suggest that the early drop in TER is possibly a direct result of structural and functional changes of the junctional complexes in polarized cells.

Polarized intestinal T-84 cells behaved differently than the other polarized intestinal and renal epithelial cells tested after apical or basolateral infection with SA-independent and SA-dependent rotaviruses. Although TER measurements of T-84 cells infected basolaterally with WC3 started to decrease at 10 hpi and continued to decrease steadily until 96 hpi (Fig. 6B), the decrease preceded (P < 0.02, Mann-Whitney U) the drop in TER values of the monolayer infected apically with WC3. Moreover, TER measurements of the polarized T-84 monolayer infected apically with WC3 dropped only up to 24 hpi before increasing again (Fig. 6B). When WC3 infection through the apical domain of the plasma membrane of polarized T-84 at 96 hpi was determined by immunofluorescence, the T-84 cells showed no sign of infection (i.e., no virus antigen was detected) (data not shown). Similar results were obtained with additional SA-independent human (Wa, HAL1166, and PA169), lapine (ALA), and simian variant SA11 Cl3 954/23R rotavirus strains (data not shown).

When polarized T-84 monolayers were inoculated apically or basolaterally with the SA-dependent RRV strain, a significant (P < 0.003, Mann-Whitney U) simultaneous drop in resistance was observed at 8 hpi (Fig. 6B). TER measurements obtained from polarized T-84 cells infected apically or basolaterally with RRV or other SA-dependent simian (SA11 Cl3), bovine (NCDV), or porcine (OSU) rotavirus strains (Fig. 6 and data not shown) continued to decline almost simultaneously at a linear rate (P ≤ 0.031, r2 = 0.97, linear regression). These results contrasted with those obtained with RRV and other SA-dependent rotavirus strains in the other five polarized cell lines tested (Fig. 6 and data not shown), which exhibited a marked and much earlier decrease in TER measurements when cells were infected apically than when infected basolaterally. The changes observed in TER measurements of infected polarized T-84 cells are in agreement with the pattern of infectivity exhibited by the polarized T-84 (Fig. 2). Therefore, not only can rotaviruses infect polarized epithelial cells differentially according to their dependency for SA residues, but infection can also depend on the type of cells being infected.

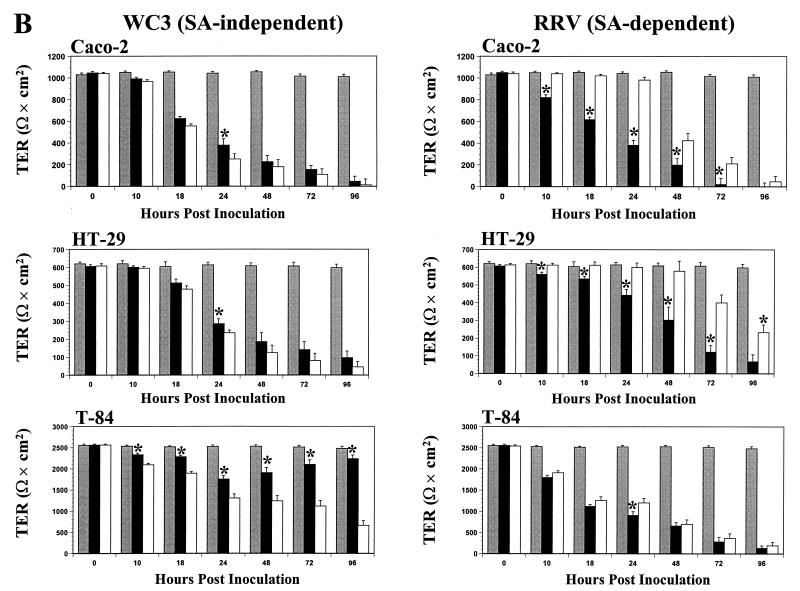

Rotavirus infection of polarized epithelial cells induces an increase in paracellular permeability as a function of loss of TER.

The integrity of the polarized Caco-2, HT-29, T-84, MDCK-1, and MA104 cell monolayers grown on 0.4-μm-pore membrane filters during apical or basolateral RRV (SA dependent) or WC3 (SA independent) rotavirus infection was also examined by determining the transepithelial permeability of [3H]inulin (5,000 Da). Nonpolarized MA104 and CCD-18 cells were used as controls.

Diffusion of [3H]inulin into the apical chamber across a 0.4-μm-pore membrane filter in the absence of cells was >50% by 6 h (Fig. 7A). Diffusion of [3H]inulin in RRV- or WC3-infected and mock-infected nonpolarized kidney MA104 and colonic CCD-18 cells had nearly reached equilibrium within 8 h (Fig. 7B and C), while only 0.7 to 9% of the [3H]inulin was found in the apical chamber when mock-infected monolayers of polarized kidney MA104 or MDCK-1 cells (Fig. 7B) and intestinal Caco-2 or T-84 cells (Fig. 7C) were examined at 24 hpi. By 96 hpi, the diffusion of [3H]inulin in the mock-infected polarized cell monolayers was 23% (MA104), 2% (MDCK-1), 3% (T-84), and 4% (Caco-2) (Fig. 7B and C). In rotavirus-infected polarized epithelial cells, the paracellular permeability of [3H]inulin increased progressively as a function of loss of TER and the time postinfection (Fig. 6 and 7B and C).

FIG. 7.

Paracellular diffusion of [3H]inulin across 0.4-μm-pore membrane filters with (A) no cells (×), (B) monolayers of nonpolarized kidney MA104 and polarized MA104 and MDCK-1 cells, and (C) monolayers of nonpolarized intestinal CCD-18 and polarized Caco-2 and T-84 epithelial cells, grown on permeable supports containing 0.4-μm pores, infected apically (▪) or basolaterally (●) at 10 FFU per cell with SA-independent rotavirus WC3 or SA-dependent RRV strain or left uninfected (○) at the indicated times. Paracellular diffusion of [3H]inulin across cell monolayers is expressed as a percentage of total [3H]inulin present in the apical chamber. Values shown are the arithmetic means of at least three replicate experiments. Error bars represent 1 standard error of the mean.

There was a significant increase (P < 0.03, Mann-Whitney U) in the paracellular permeability to [3H]inulin in polarized MA104 cells infected apically or basolaterally with the WC3 rotavirus strain with respect to that in mock-inoculated control cells as early as 24 hpi (Fig. 7B). While the [3H]inulin diffusion in polarized MA104 cells infected apically or basolaterally with the WC3 rotavirus strain occurred at the same rate (P > 0.790, Mann-Whitney U), the [3H]inulin diffusion in polarized MA104 cells infected apically with the RRV strain was significantly higher (P < 0.005, Mann-Whitney U) than that in cells infected basolaterally with RRV from 24 hpi to 96 hpi (Fig. 7B). By 96 hpi, [3H]inulin diffusion in apically or basolaterally WC3-infected cells or in apically but not basolaterally RRV-infected MA104 cells reached ≥95% (Fig. 7B), and TER measurements were 0 Ω × cm2 (Fig. 6A). [3H]inulin diffusion of polarized MA104 cells infected basolaterally with RRV only reached about 60% by 96 hpi (Fig. 7B), a time at which these cells were displaying TER measurements of 46 Ω × cm2 (Fig. 6A). These results corroborate that MA104 cells are capable of becoming polarized in cell culture and that SA-dependent rotaviruses infect in an asymmetric fashion.

Although TER measurements decreased simultaneously in Caco-2 cells infected apically or basolaterally with WC3 (Fig. 6B), [3H]inulin diffusion occurred significantly faster (P < 0.033, Mann-Whitney U) in Caco-2 cells infected basolaterally than in those infected apically (Fig. 7C). By 96 hpi, [3H]inulin diffusion in polarized Caco-2 cells infected apically or basolaterally with WC3 was 33 and 57%, respectively, while [3H]inulin diffusion rates in cells infected apically or basolaterally with RRV were 65 and 17%, respectively (Fig. 7C). Together, these results indicate that RRV infects polarized cells more efficiently at the apical surface than at the basolateral surface and that WC3 is capable of efficiently infecting both domains of the plasma membrane, with the possibility that WC3 infects better through the basolateral surface than through the apical surface of Caco-2 cells.

Compared to control mock-inoculated polarized MDCK-1 and T-84 cell monolayers, paracellular [3H]inulin diffusion in MDCK-1 and T-84 cells infected apically or basolaterally with WC3 did not increase significantly (P > 0.191, Mann-Whitney U) at any of the time points analyzed (Fig. 7B and C). Paracellular [3H]inulin diffusion in MDCK-1 cells infected apically with RRV was significantly greater (P < 0.03, Mann-Whitney U) than that of mock-inoculated MDCK-1 cells, but similar (P > 0.121, Mann-Whitney U) to that of MDCK-1 cells inoculated basolaterally with RRV (Fig. 7B) at 72 and 96 hpi. As observed with the TER measurements (Fig. 6B), [3H]inulin diffusion rates in polarized T-84 cells infected apically or basolaterally with RRV occurred simultaneously (P < 0.007, Mann-Whitney U) and were greater (P < 0.042, Mann-Whitney U) than that of mock-inoculated T-84 cells by 48 hpi (Fig. 7C). Although [3H]inulin did diffuse through T-84 and MDCK-1 cells infected with RRV, the rate of [3H]inulin diffusion was <10% by 96 hpi (Fig. 7B and C), possibly because T-84 and MDCK-1 cells infected with RRV still display high TER values of >200 Ω × cm2 at this time point (Fig. 6). Therefore, the observation by Tucker and Compans (62) that the degree of permeability varies among polarized epithelial cell types was clearly confirmed in this study, and the differences in the degree of permeability may be related to the nature of the junctional complexes in the polarized cells tested.

DISCUSSION

Polarized epithelial cells, which are often the initial target for pathogens, form a layer that lines all body cavity surfaces, function in selective secretion and adsorption, and provide a barrier to the external environment that is held together by specialized junctions between the cells. Polarized epithelial cells grown on permeable supports provide a model to mimic the natural target in vivo and allow the study of the site of entry and release, as well as insight into the possible mechanisms of pathogenesis for viruses and bacteria (2, 3, 7, 8, 16, 17, 19, 20, 27, 29, 31, 36, 40, 43, 47, 48, 50–52, 54–56, 57–62, 64). Rotavirus entry into cells appears to be a multistep process involving at least three sites or molecules on the cellular surface, and different results are obtained depending on the SA-binding properties of the particular rotavirus strain analyzed (5, 6, 9, 12, 41, 66; M. Ciarlet, J. E. Ludert, M. Iturriza-Gómara, F. Liprandi, J. J. Gray, U. Desselberger, and M. K. Estes, submitted for publication). The growth of polarized epithelial cell monolayers on permeable supports allowed us to explore whether rotavirus strains which differ in their requirement for SA residues to bind and initiate an efficient infection utilize the same site of entry into cells and to understand the mechanisms involved in rotavirus pathogenesis.

In this study, we show that (i) SA-dependent rotaviruses infect mainly through the apical membrane domain of five of six polarized epithelial cells tested, while SA-independent rotaviruses are capable of productive infection through both sides of the epithelium of all polarized cell lines tested, indicating that the rotavirus cellular SA-independent receptor is present on both surfaces of the polarized cell membranes; (ii) SA residues on the apical cell surface of polarized cells, visualized by direct staining using WGA conjugated to Texas Red, are required for and correlate with the efficient infectivity of SA-dependent but not SA-independent rotaviruses, because removal of SA residues from the plasma membrane of polarized cells reduces the infectivity of SA-dependent but not SA-independent rotavirus strains at the apical surface; and (iii) SA-dependent rotaviruses are less efficient than SA-independent rotaviruses at infecting the basolateral surface of most polarized cells, possibly due to the absence of SA residues on basolateral surfaces. These results provide new insight into the rotavirus entry process and suggest that SA-dependent and SA-independent rotaviruses enter cells through different mechanisms and likely use a different receptor. This observation may be important for selection of future live virus vaccine strains, because a complete understanding of the complex interactions between rotaviruses and cells that may affect viral pathogenesis is lacking.

The use of a permeable support with 0.4-μm pores is necessary to prevent cellular migration to the lower side of the membrane filter while still allowing viruses or other microorganisms to access the basolateral domain of the plasma membrane through the pores and has significant implications for proper interpretations of the results. In fact, data from Tucker et al. (60) revealed that polarized Vero C1008 and Caco-2 cells growing on the lower face of the membrane filter containing 3.0-μm pores are polarized because these Vero C1008 and Caco-2 cells exhibit the same polarity of influenza virus and VSV release, respectively, as the cells growing on the upper face of the membrane filter. Since the epithelial cells growing on the lower surface of the membrane filter can be polarized, a virus applied to the basolateral side of the membrane filter can encounter apical-like plasma membranes that could lead to misleading results.

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (52) and influenza virus, which utilizes SA as a receptor to initiate infection, have been reported to infect MDCK cells symmetrically (19, 20, 47), but these studies used cells grown on 3.0-μm-pore membranes. Nonetheless, VSV infection of cells grown on 3.0-μm-pore membrane occurs basolaterally only (19, 20, 47). Possible explanations are that (i) although cells grow through the pores and establish a polarized monolayer on the lower surface of the filter, these cells may be at a different differentiation state than the cells on the upper surface of the filter, or (ii) the cells on the lower surface, contrary to the cells on the upper surface of the filter, may lack a thick glycocalyx, which may prevent binding of VSV to the cells, since retargeting the coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor to the apical surface of polarized epithelial cells reveals that the glycocalyx impedes interaction of adenovirus vectors with apical receptors (44).

During the course of this study, we attempted to use embryonic monkey kidney MA104 cells as control monolayers to properly monitor access of virus to the basolateral surface of cells grown on 0.4-μm-pore membrane filters. Although many continuous cell lines of renal origin are known to exhibit structural and functional characteristics of the native epithelia (62), MA104 cells, originally derived by Microbiological Associates and used widely and mainly for rotavirus research for over 20 years, were not known to become polarized in culture. SA-dependent but not SA-independent rotavirus infection of MA104 cells obtained from either Microbiological Associates or the ATCC and grown on permeable supports for 14 to 16 days is dependent on the state of cellular differentiation of the cells. Unexpectedly, we found that MA104 cells form domes and become polarized, as evidenced by EM analysis, TER measurements, and paracellular diffusion of [3H]inulin, so we used human intestinal colonic CCD-18 cells, highly susceptible to rotavirus infection (M. Ciarlet, S. E. Crawford, E. Cheng, S. E. Blutt, D. A. Rice, J. M. Bergelson, and M. K. Estes, submitted for publication), as control nonpolarized cell monolayers for subsequent studies.

Reportedly, MA104 cells were originated by explant culture and subsequent passage by enzymatic dissociation from embryonic rhesus monkey kidney tissue, but karyology and isoenzyme analyses revealed that MA104 cells distributed to some sources showed properties of African green monkeys, not rhesus monkeys (65). Also, the original MA104 cell population was shown to be heterogeneous, based on porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus permissiveness, and by limiting dilutions, two homogeneous subpopulations that differ in their permissiveness to PRRS virus infection have been isolated (33). However, isoenzyme analysis of ampules of MA104 cells at passage 3, deposited at the ATCC in 1994, showed that the species of origin of the MA104 cells was a rhesus monkey. Based on our results of differential infectivity of MA104 cells, additional characterization of MA104 cells is needed to define the nature of the cell junctional complexes, to detect any functional characteristics typical of the polarized renal epithelia, and to distinguish separate strains of MA104 cells with different properties, similar to the two strains of MDCK cells (21, 46).

Most continuous polarized epithelial cells are of renal origin, but the number of polarized intestinal epithelial cells which will more closely mimic the natural rotavirus target in vivo is limited to three well-characterized cell lines, Caco-2, HT-29, and T-84 cells, and all of these cell lines were used in this study to examine rotavirus uptake. For the polarized Caco-2 and HT-29 epithelial cells, loss of cellular TER due to rotavirus infection, site of entry of SA-dependent and SA-independent rotavirus strains, and distribution of SA residues on the cell membrane were similar. However, results obtained with polarized T-84 cells differ from those obtained in Caco-2 and HT-29 cells, suggesting that although these three intestinal epithelial cell lines were derived from a cancerous (adenocarcinoma) colon, the cell lines do not have the same characteristics and behave differently. Although T-84 and Caco-2 cells synthesize and secrete similar basal lamina components (39), T-84 cells differ from Caco-2 and HT-29 cells in that T-84 cells (i) resemble colonic crypt cells, based on morphology, TER, and ionic transport properties, while HT-29 and Caco-2 cells resemble absorptive enterocytes (13, 23, 26, 38, 46), (ii) do not express the same brush border enzyme activities as or possess the well-developed apical cilia or microvilli of Caco-2 or HT-29 cells (38, 46), and (iii) develop higher TER values than Caco-2 or HT-29 cells (13, 38, 46).

In this study, entry of SA-dependent rotavirus strains into polarized T-84 cells was achieved through both the apical and basolateral surfaces, because T-84 cells, unlike Caco-2 and HT-29 cells or the other polarized cells of renal origin tested, exhibit enough SA residues on the basolateral membrane domain to allow initial binding of the SA-dependent rotaviruses. T-84 cells also differ from the other polarized cells tested in that they poorly support the spread of infection from cell to cell when cells are infected apically with an SA-independent but not an SA-dependent rotavirus strain. The ability of SA-independent rotaviruses to productively infect T-84 cells through the apical surface may be differentiation state dependent, because nonpolarized T-84 cells are more susceptible to rotavirus infection than polarized T-84 cells (Ciarlet, Crawford, et al., submitted). The maximal rotavirus infection occurring at early stages of differentiation of T-84 cells may be due to a greater expression of or better access to the SA-independent rotavirus cellular receptor on the apical surface of T-84 cells. The dependency of virus permissiveness on cellular differentiation state has also been observed with human cytomegalovirus infection of Caco-2 cells (29), although rotavirus infection of Caco-2 cells is equally productive in both undifferentiated and differentiated Caco-2 cells (30; Ciarlet, Crawford, et al., submitted). Caco-2 cells may be a better model for studying rotavirus-gastrointestinal cell interactions.

Recently, Jourdan et al. (31) showed that release of the SA-dependent RRV strain from polarized intestinal epithelial Caco-2 cells occurs through a nonconventional vesicular transport mechanism from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the apical plasma membrane that bypasses the Golgi apparatus. Our results demonstrate that both SA-dependent and SA-independent rotaviruses, regardless of the point of entry into the cells, mature at the apical membrane domain of polarized intestinal Caco-2 and HT-29 cells before monolayer disruption or cell lysis. This restriction of virus maturation to the apical membrane domain suggests that the asymmetric release of infectious virus may be a factor in pathogenesis. Release of rotavirus into the lumen of the intestine is important to limit the spread of infection to the intestinal epithelium and to shed the virus in fecal material to transmit the virus to other hosts. However, the ability of SA-independent rotaviruses, which include all human rotavirus strains, to spread laterally from cell to cell may increase the infectivity range to underlying tissues and to other organs, such as the liver or kidneys, in immunocompromised hosts (18, 22, 34, 63).

The relevance of the capacity of SA-independent rotaviruses to infect basolateral surfaces in vivo, cause disruption of tight junctions, and decrease TER may also be important for complete interactions of the virus with all necessary cellular components. Once the tight junctions are disrupted, the virus would have access to the basolateral surface, facilitating its spread. Since certain integrins may serve as possible secondary receptors (9, 24; Ciarlet et al., unpublished), access to the basolateral domain of the plasma membrane must be required, because, in the cellular epithelium of the gut, the integrins are found adjacent to the tight junctions on the basolateral, not apical, cell surface of enterocytes (28). Therefore, if integrins play an important role in rotavirus attachment or entry during natural rotavirus infection, the opening of cell-cell junctions between enterocytes may allow rotaviruses to interact with the integrins.

Paracellular permeability changes occur in response to a number of bacteria and contribute to diarrheal disease by altering intestinal secretion and absorption (3, 16, 17, 27, 40, 43, 51, 54, 56, 58, 64). Similar to some enteric bacteria, rotavirus produces an enterotoxin (1) and stimulates the enteric nervous system (37), and rotavirus or its proteins exert numerous physiological effects on the intestinal epithelium and host functions, including alteration of ion transport (25), disruption of the tight junction barrier (14, 25, 31, 42, 57, 59), production of cytokine and chemokine responses (4, 49, 53), and stimulation of cell signaling pathways (35), all of which play a role in pathogenesis and/or immune responses.

To improve our understanding of the pathophysiology of rotavirus disease, polarized epithelial cells grown on permeable supports represent an ideal system that can be used to integrate the biology, physiology, and genetics of rotavirus-cell interactions that result in pathogenesis, immune response, and signaling events relevant to rotavirus infection of the intestinal epithelium in vivo. Eventually, the identification of possible mechanisms common to viral and bacterial enteric pathogens could lead to development of broadly acting drugs to prevent diarrhea caused by different pathogens and should create opportunities to develop effective treatment and prevention strategies for the global, clinically important disease caused by rotavirus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Lennart Svensson (Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden), Sheila Crowe (University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston), and Richard E. Sutton (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Tex.) for supplying cell lines and Henry P. Adams and Frank Herbert (Integrated Microscopy Core, Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Baylor College of Medicine) for electron microscopy analyses.

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants DK30144 to M. K. Estes and DK56338 to the Texas Gulf Coast Digestive Diseases Center.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ball J M, Tian P, Zeng C Q-Y, Morris A P, Estes M K. Age-dependent diarrhea induced by a rotaviral nonstructural glycoprotein. Science. 1996;272:101–104. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blank C, Anderson D, Beard M, Lemon S M. Infection of polarized cultures of human intestinal epithelial cells with hepatitis A virus: vectorial release of progeny virions through apical cellular membranes. J Virol. 2000;74:6476–6484. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.14.6476-6484.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canil C, Rosenshine I, Ruschkowski S, Donnenberg M, Kaper J, Finlay B B. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli decreases the transepithelial electrical resistance of polarized epithelial monolayers. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2755–2762. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.7.2755-2762.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casola A, Estes M K, Crawford S E, Ogra P L, Ernst P B, Garofalo R, Crowe S E. Rotavirus infection of cultured intestinal epithelial cells induces secretion of CXC and CC chemokines. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:947–955. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70314-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciarlet M, Estes M K. Human and most animal rotavirus strains do not require the presence of sialic acid on the cell surface for efficient infectivity. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:943–948. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-4-943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciarlet M, Estes M K. Interactions between rotavirus and gastrointestinal cells. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2001;4:435–441. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(00)00232-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clayson E T, Compans R W. Entry of simian virus 40 is restricted to apical surfaces of polarized epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:3391–3396. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.8.3391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clayson E T, Brando L, Compans R W. Release of simian virus 40 virions from epithelial cells is polarized and occurs without cell lysis. J Virol. 1989;63:2278–2288. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.5.2278-2288.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coulson B S, Londrigan S, Lee D. Rotavirus contains integrin ligand sequences and a disintegrin-like domain that are implicated in virus entry into cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5389–5394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crawford S E, Labbé M, Cohen J, Burroghs M, Zhou J-Y, Estes M K. Characterization of virus-like particles produced by the expression of rotavirus capsid proteins in insect cells. J Virol. 1994;68:5945–5952. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5945-5952.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crawford S E, Mukherjee S, Estes M, Lawton J, Shaw A, Ramig R, Prasad B. Trypsin cleavage stabilizes the rotavirus VP4 spike. J Virol. 2001;75:6052–6061. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.13.6052-6061.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delorme C, Brüssow H, Sidoti J, Roche N, Karlsson K-A, Neeser J-R, Teneberg S. Glycosphingolipid binding specificities of rotaviruses: identification of a sialic acid-binding epitope. J Virol. 2001;75:2276–2287. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.5.2276-2287.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dharmsathaphorn K, McRoberts J, Mandel K, Tisdale L, Masui H. A human colonic tumor cell line that maintains vectorial electrolyte transport. Am J Physiol. 1984;246:G204–G208. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1984.246.2.G204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dickman K, Hempson S, Anderson J, Lippe S, Zhao L, Burakoff R, Shaw R D. Rotavirus alters paracellular permeability and energy metabolism in Caco-2 cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;279:G757–G766. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.279.4.G757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eaton S, Simons K. Apical, basal, and lateral cues for epithelial polarization. Cell. 1995;82:5–8. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fasano A, Uzzau S, Fiore C, Margaretten K. The enterotoxic effect of zonula occludens toxin on rabbit small intestine involves the paracellular pathway. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:839–846. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9041245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finlay B B, Gumbiner B, Falkow S. Penetration of Salmonella through a polarized Madin-Darby canine kidney epithelial cell monolayer. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:221–230. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.1.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitts S, Green M, Reyes J, Nour B, Tzakis A, Kocoshis S. Clinical features of nosocomial rotavirus infection in pediatric liver transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 1995;9:201–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuller S, von Bonsdorff C-H, Simons K. Vesicular stomatitis virus infects and matures only through the basolateral surface of the polarized epithelial cell line, MDCK. Cell. 1984;38:65–77. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90527-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fuller S, von Bonsdorff C-H, Simons K. Cell surface influenza haemagglutinin can mediate infection by other animal viruses. EMBO J. 1985;4:2475–2485. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03959.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaush C R, Hard W L, Smith T F. Characterization of an established line of canine kidney cells (MDCK) Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1966;122:931–935. doi: 10.3181/00379727-122-31293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilger M, Matson D, Conner M E, Rosenblatt H, Finegold M J, Estes M K. Extraintestinal rotavirus infections in children with immunodeficiency. J Pediatr. 1992;120:912–917. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81959-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]