Abstract

Objective

To provide family physicians with a practical evidence-based approach to management of otitis externa.

Sources of information

The approach described is based on MEDLINE and PubMed literature published between 1993 and 2023.

Main message

Otitis externa is diffuse inflammation of the external auditory canal and typically occurs from moisture exposure and trauma. Management focuses on eliminating infection, pain management, education, and preventing recurrence. The primary treatment of uncomplicated otitis externa is topical. Complicated presentations may require additional systemic therapy.

Conclusion

History taking and physical examination can help differentiate among acute, chronic, and necrotizing otitis externa. At-risk populations, typically those who are immunosuppressed, are more likely to develop necrotizing otitis externa and should be carefully monitored.

Case introduction

V.E., a 68-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, osteoporosis, and hyperlipidemia, presents to her family physician with sudden-onset right ear pain. Following an aquatic fitness class, V.E. felt her ear get itchy and subsequently used cotton-tipped swabs. For 2 days her ear has been painful to touch and her hearing “muffled.” She experiences minor relief with ibuprofen. She denies changes to her voice or swallowing. She notes 3 prior episodes of “swimmer’s ear.”

Main message

Otitis externa is diffuse inflammation of the external auditory canal (EAC) generally caused by bacterial infection and can present as acute, chronic, or necrotizing (also referred to as malignant).1,2 Otitis externa affects approximately 10% of individuals during their lifetimes3 and in 2007 an estimated 8.1 health care visits per 1000 population in the United States were for acute otitis externa (AOE).4 The highest incidence of AOE was in patients between ages 5 and 14; however, 53% of health care visits were for patients 20 years and older.4

Patients with AOE are usually managed by primary care, with 3% of patients requiring specialist care.5 While uncomplicated cases of AOE respond well to topical treatment, patients with diabetes or immunosuppression may require systemic treatment.4,6 Complicated or necrotizing infections can substantially impact function and quality of life. Patients with these infections should be referred to an otolaryngologist–head and neck surgeon (OHNS) for management.7

Sources of information

MEDLINE and PubMed databases were searched for English-language human research, review articles, and guidelines on otitis externa published between 1993 and 2023. Most retrieved articles provided level II and III evidence.

Symptoms and causes

Acute otitis externa is inflammation of the EAC and can extend to the tympanic membrane or pinna.2 Known as swimmer’s ear or tropical ear, it often occurs after increased water exposure or humidity.8 More than 90% of AOE infections are bacterial; typical microbes include Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Staphylococcus aureus,9,10 and one-third of cases are polymicrobial.2 Dermatologic diseases including lupus erythematosus, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, acne, and seborrheic dermatitis can predispose patients to AOE.11

Cerumen is mildly acidic and produces lysosomes that inhibit microbial growth.8,12 Disruption of the cerumen barrier or altering the pH in the EAC through water exposure, trauma (eg, from cotton-tipped swabs, hearing aids, earplugs, excoriation), soap deposits, or alkaline drops can increase the risk of otitis externa.2,10,13,14

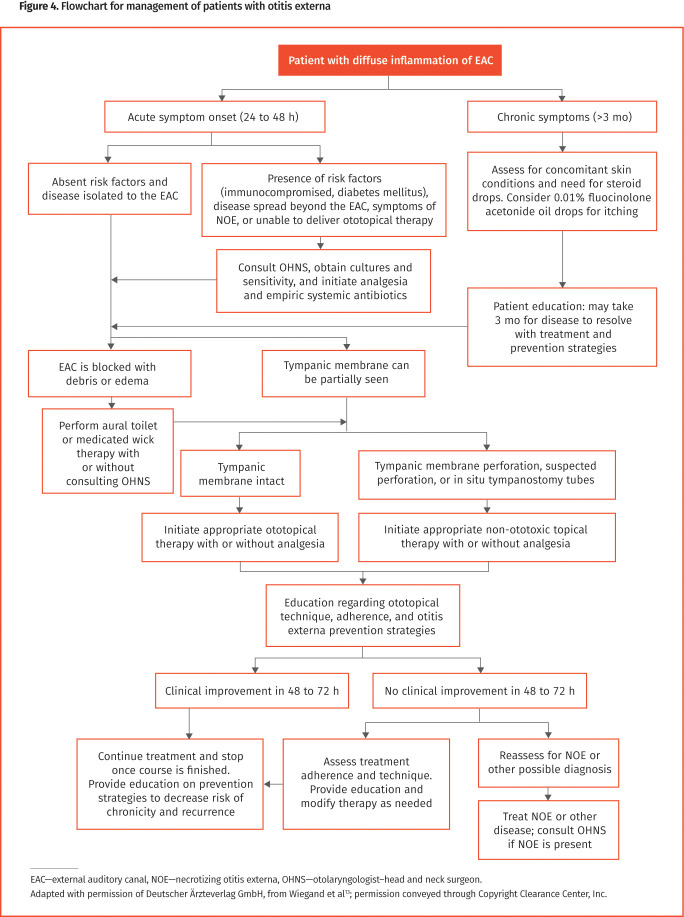

The onset of AOE is usually within 48 hours of cerumen barrier disruption.2 Associated symptoms include unilateral EAC pain, itching, feeling of fullness, jaw pain, and hearing loss. Physical examination typically reveals findings of external ear tenderness, EAC edema, erythema, and limited cerumen (Figure 1).15 Other physical findings include otorrhea, regional lymphadenitis, tympanic membrane erythema, or cellulitis of the pinna and adjacent skin.11,13 Instances of severe AOE are characterized by intense pain, auditory canal obstruction with edema or otorrhea, purulent discharge, adenopathy, and periauricular edema.8

Figure 1.

Otoscopic view of acute otitis externa: Note the canal edema, erythema, and lack of cerumen.

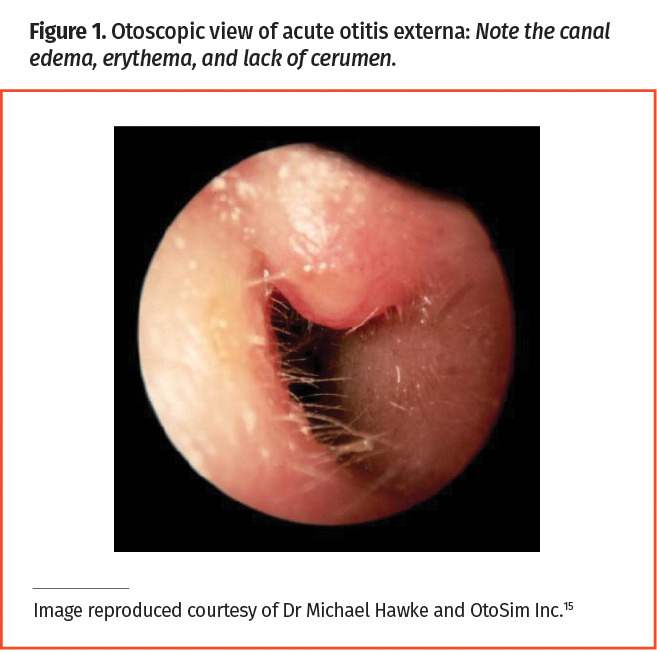

Acute otitis externa lasts for less than 6 weeks, whereas chronic otitis externa (COE) lasts for more than 3 months.3,10,16 Chronic otitis externa is characterized by painless, mild discomfort and itching. On examination, the skin of the ear canal may appear dry, flaky, and erythematous, with clear otorrhea17,18 (Figure 2).15 Patients with COE may exhibit episodes of AOE.19 Otoscope examination findings may resemble AOE; however, skin thickening may be noted.10 Chronic infections should be cultured to guide treatment.17

Figure 2.

Otoscopic view of chronic otitis externa with characteristic dry, flaky canal

Red flags. Necrotizing otitis externa (NOE) is an invasive infection more commonly seen in patients who have diabetes, are older than 65, or are immunocompromised.7,20 Pseudomonas aeruginosa is responsible for more than 90% of cases. Patients initially present with AOE, but when left untreated it progresses to osteomyelitis of the skull base and advances to the surrounding tissue of the middle ear, inner ear, and brain.2,21 On examination, granulation tissue may be observed in the EAC. Patients with advanced infections may exhibit facial nerve palsy21 and occasionally lower cranial nerve (ie, nerves 9 to 12) palsies.7,22 Patients with cranial nerve palsies may present with dysphagia, dysphonia, and shoulder weakness, and can develop meningitis or brain abscess.7,22 Progression to NOE is associated with considerable morbidity and mortality; therefore, it is important to identify patients early and monitor at-risk populations.20

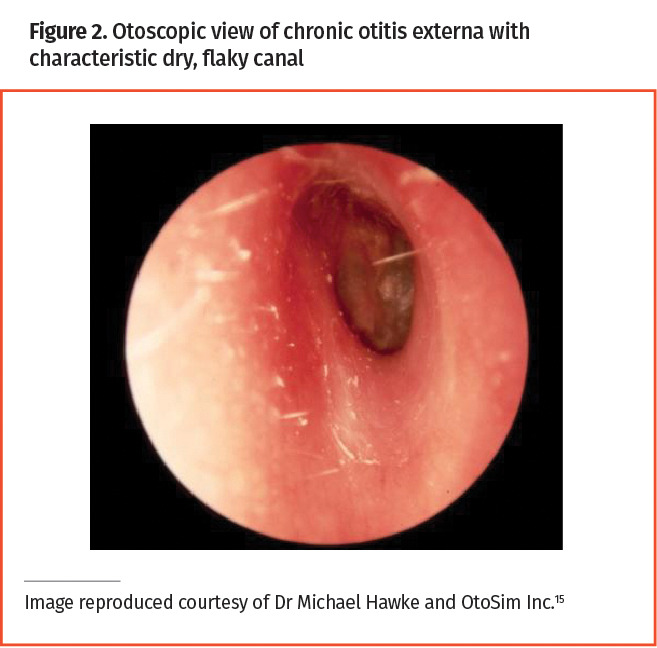

Otomycosis. Fungal pathogens Candida albicans and Aspergillus species are most often responsible for otomycosis, a fungal infection of the EAC.23 Fungal infections may be noted in patients who continue to have symptoms despite completion of antibiotic therapy. Risk factors are similar to those for AOE but also include chronic otitis media with tympanic membrane perforation and antibiotic use. Common symptoms include pruritis, otalgia, hearing loss, and otorrhea.24 Physical examination will classically show findings of otorrhea, edematous or erythematous EAC, and cottonlike fungal growth25 (Figure 3).15 Cultures can provide mycologic confirmation of fungal infection.

Figure 3.

Otoscopic view of otomycosis with fuzzy, cottonlike fungal hyphae

Diagnosis. A diagnosis of AOE or COE is clinical and based on history and physical examination findings. The physical examination should include otoscopic or otomicroscopic inspection of the EAC and tympanic membrane, and examination of the pinna, mastoid process, head and neck lymph nodes, cranial nerves, and surrounding skin.13 Patients may present with a fever.

Differential diagnosis of otitis externa includes acute otitis media, mastoiditis, furunculosis, cholesteatoma, herpes zoster oticus (Ramsay Hunt syndrome), otomycosis, contact dermatitis, and retained foreign body.2,8,13,26

For suspected NOE, magnetic resonance imaging is best for detecting early head and neck soft tissue changes, whereas computed tomography is ideal for identifying later bony erosion.13,21,27 Technetium 99 scanning is the most sensitive imaging modality for NOE and identifies early bony disease.28 Gallium 67 scintigraphy and indium 111–labelled leukocyte scans detect early stages of NOE bony involvement and are helpful to monitor for disease resolution.28 Cultures, a markedly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and biopsy findings can help distinguish NOE from squamous cell carcinoma, which may present with otorrhea and ear pain.13,20 Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level can help assess disease progression.20

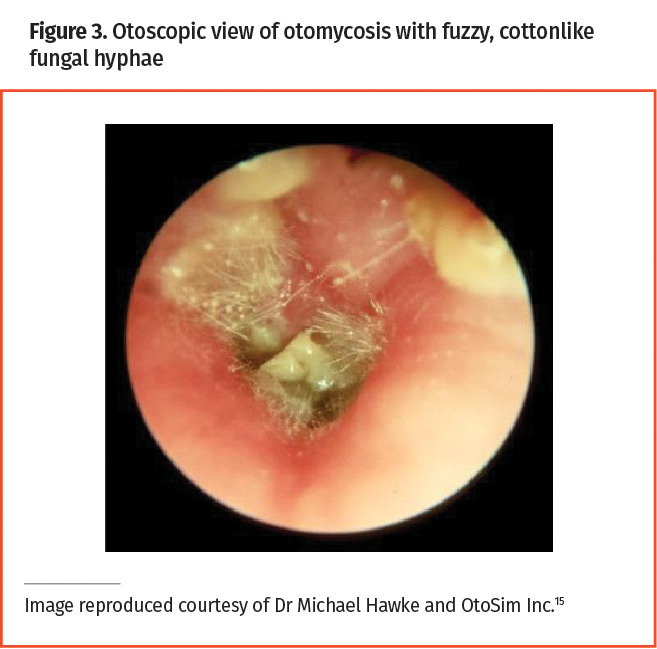

Management. Figure 4 is a flowchart for the management of patients with otitis externa in primary care.13

Figure 4.

Flowchart for management of patients with otitis externa

Topical therapy: In patients presenting with uncomplicated AOE, the 2014 American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery clinical practice guidelines recommend topical antimicrobial or antiseptic therapies as first-line treatment.2 Topical treatments are highly effective for AOE as they deliver concentrated medication directly to affected tissue. They are well tolerated and 65% to 90% of patients’ symptoms clinically resolve in 7 to 10 days.2,16,29 Patients typically note substantial improvement in 72 hours.30 Clinical outcomes are similar for topical antimicrobial treatments—either quinolones or nonquinolones with or without added steroids31 (Table 1).24,32-45 There is limited evidence to support use of topical steroid treatment alone.3 There are no systematic studies of dosing frequency for ototopical treatment of AOE; however, quinolone studies suggest that twice daily dosing is adequate.31,46 Topical aminoglycosides should be avoided in patients with tympanic membrane perforation, suspected perforation, or in situ tympanostomy tubes, as they can be ototoxic.29,47 Children with a history of tympanostomy tube insertion should be carefully examined as tubes can remain in situ for 3 years or longer. Quinolone drops are non-ototoxic and recommended for patients with suspected or perforated tympanic membrane.2 Antiseptic drops alone, such as those containing acetic acid, show similar rates of resolution if treatment duration is shorter than 1 week. Antibiotic treatments with or without steroids lasting longer than 1 week show improved rates of cure and shorter symptom duration.29 There are low rates of adverse events noted with ototopical therapy; however, pruritis (5% to 7% incidence) and site reaction (4% incidence) are most commonly reported.29,31 Contact dermatitis is rare after a single course of treatment for AOE; however, patients treated for COE with aminoglycosides are at increased risk (40% to 60%).48

Table 1.

Topical antimicrobial otic therapies for patients with otitis externa

| TREATMENT CLASS | ACTIVE AGENTS | POPULATION | DOSAGE | OTOTOXIC* | NOTES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic otic drops | 10,000 IU of polymyxin B and 0.025 mg of gramicidin per mL32 | ≥6 y | 1-2 drops 4 times a day for 5-7 days | Yes | Over the counter |

| Ofloxacin 0.3%33 | ≥6 mo |

|

No | Prescription | |

| Ciprofloxacin 0.2%34 | ≥1 y | Instill 1 container (0.25 mL) in ear twice a day for 7 days | No | Prescription | |

| Combined antibiotic otic drops | 10,000 IU of polymyxin B and 50 mg of lidocaine hydrochloride per mL35 | ≥6 y | Instill 3-4 drops 4 times a day for 5-7 days | Yes | Over the counter |

| Ciprofloxacin hydrochloride 0.3% and dexamethasone 0.1%36 | ≥6 mo | 4 drops twice a day for 7 days | No |

|

|

| Acetic acid 2% and hydrocortisone 1%38 | ≥3 y | 3-5 drops 3 or 4 times a day | Yes | Prescription | |

| Neomycin sulfate 0.35%, 10,000 IU of polymyxin B sulfate, and hydrocortisone 1%39 | ≥2 y | 4 drops 3 or 4 times a day for a maximum of 10 days | Yes | Prescription | |

| Ciprofloxacin hydrochloride 0.3% and fluocinolone acetonide 0.025%40 | >6 mo | Instill 1 container (0.24 mL) in ear twice a day for 7 days | No | Prescription | |

| Antiseptic drops | Isopropyl alcohol 95%41 | No guidelines | Apply 4-5 drops per ear once after water or moisture contact | Yes | Over the counter |

| Antifungal medication | Flumethasone pivalate 0.02% and clioquinol 1%42 | ≥2 y | 2-3 drops daily for fewer than 10 days | Yes | Prescription |

| Voriconazole 1%43·44 | No guidelines | No guidelines; suggest 3 drops 3-4 times daily for 14 days43,44 | No | Prescription, requires compounding, and is expensive | |

| Clotrimazole 1% | No guidelines | No guidelines; suggestions include a coated wick changed every 3 days for 1 wk24,45 | No | Over the counter |

Contraindicated in patients with perforated tympanic membrane.

Bacterial COE infections are treated similarly to AOE. Patients with COE with chronic dermatologic conditions benefit from topical steroid cream applied twice daily (0.1% triamcinolone cream or 0.05% desoximetasone cream).17 Chronic fungal infections should be treated with topical antifungal drops or creams and tympanic membrane perforation should guide treatment selection.13

Medicated wick therapy and aural toilet: Patients with severely edematous ear canals that preclude use of ototopical drops may benefit from medicated wick therapy. Wicks should ideally be made of compressed cellulose or ribbon gauze.2,49 Refrain from using cotton balls as they can disintegrate and be challenging to remove.2,49 Dry wicks should be placed in the ear canal and expanded immediately with instilled antibiotic drops. After 24 to 48 hours, replace the wick if the tympanic membrane cannot be seen; otherwise remove the wick and continue ototopical therapy for 7 to 10 days.29,30

Uncomplicated aural toilet of ear canals occluded with discharge or cerumen can be performed with a small suction cannula inserted less than 1 cm into the canal.2,50 More challenging cases should be referred to an OHNS. While no studies evaluate the efficacy of aural toilet and medicated wicks, these treatments continue to be suggested in guidelines.2,3,29 The risks of medicated wicks or aural toilet include pain and trauma.2

Patient education: Guidelines strongly recommend educating patients on proper administration of drops, as technique and adherence impact outcomes. Patients should lie with the affected ear upward with drops instilled until the ear canal is filled. Gentle manipulation of the pinna or tragus can help filling. Patients should maintain this position for 5 minutes or longer, then the ear should be left to drain and dry naturally.2 Patients should take their drops for the length of recommended treatment and inform their physician if symptoms persist. Failure of symptoms to respond to conservative treatment after 7 days is a risk factor for NOE.7

Systemic antibiotics: Patients with uncomplicated AOE should be first treated with topical antibiotics.2,51 Despite strong evidence for topical therapy, 20% to 44% of patients with AOE receive a prescription for systemic antibiotics.52,53 Indications for systemic therapy alongside topical treatment include diabetes, immunosuppression, symptoms of NOE, infection spread beyond the EAC, symptoms refractory to topical treatment, or substantial challenges with topical delivery.2,13 Systemic treatment should be selected according to bacterial cultures and sensitivity; however, empiric antibiotics that target P aeruginosa are appropriate.13,54 Treatment with oral quinolones, particularly ciprofloxacin, considerably reduces hospitalization and use of intravenous antibiotics, and resolves symptoms in 90% of patients with few adverse events.21 Length of NOE treatment is based on clinical presentation and requires close follow-up with an OHNS.20,21,55

Analgesia: Patients can take over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or acetaminophen for mild to moderate AOE pain.13 Some studies suggest that topical antibiotic treatments with steroids reduce pain and edema more than antibiotics alone.56,57 Opioids are infrequently indicated for AOE, as patients should experience considerable analgesia with appropriate topical therapy in 48 to 72 hours.2

Prevention: Patients with otitis externa are at high risk of chronicity or recurrence.3 During treatment, patients should avoid moisture or putting anything in their ears until infection resolution. Patients should avoid precipitating factors such as ear scratching, cotton-tipped swabs, or other ear canal trauma, and should treat underlying dermatologic conditions.2,13 Adjunct therapies to consider include drying ears after water exposure with a hair dryer on the cool setting and using acidifying drops (acetic acid) after ears are dry. There are no clinical trials that assess home remedies (eg, 1:1 solution of white vinegar with either isopropyl alcohol or water); however, they may be effective because of their acidifying and antiseptic properties.2 Patients should be advised to take precautions around water: Wearing a swim cap or placing cotton balls covered with petroleum jelly in the ear canal can create an excellent water seal before swimming or bathing.2 Earplugs may irritate the canal and increase the risk of otitis externa.2,11 Patients with COE should similarly avoid aggravating factors and use 0.01% fluocinolone acetonide oil drops to relieve itching; resolution may take 3 months or longer.18

Case resolution

V.E. winces when you move her pinna to inspect her ear canal. Her right ear is erythematous and edematous with mild discharge, and the tympanic membrane is intact but swollen. Findings of a cranial nerve, lymph node, and head and neck examination are unremarkable and she is afebrile. Her presentation is consistent with AOE. You initiate ciprofloxacin-dexamethasone drops twice daily for 7 days. You advise her to continue taking ibuprofen as needed, refrain from getting water in her ear or using cotton-tipped swabs, and return to her aquatic fitness classes upon symptom resolution. You suggest that she use a swim cap and gently blow dry her ears on the cool setting after water exposure. You call her 2 days later and she reports her symptoms have considerably improved. You advise her to call if symptoms persist beyond the length of treatment.

Conclusion

Otitis externa is diffuse painful inflammation of the EAC occurring in patients after exposure to moisture or trauma. Findings of a careful history and physical examination can help differentiate among AOE, COE, NOE, and other conditions with otorrhea and pain. Patients who are elderly, have diabetes, or are immunosuppressed, who are at higher risk of developing NOE, warrant special consideration. Antimicrobial drops with or without steroids are first-line treatment for uncomplicated otitis externa. Patients with complicated or severe disease require additional systemic antibiotics and evaluation by an OHNS. Patients may benefit from counselling on proper otic drop technique and strategies to prevent recurrence.

Editor’s key points

▸ Otitis externa is diffuse painful inflammation of the external auditory canal occurring in patients after exposure to moisture or trauma. Findings of a careful history and physical examination can help differentiate among acute, chronic, and necrotizing otitis externa, and other conditions with otorrhea and pain.

▸ Patients who are elderly, have diabetes, or are immunosuppressed are at higher risk of developing necrotizing otitis externa and warrant special consideration.

▸ Antimicrobial drops with or without steroids are first-line treatment of uncomplicated otitis externa. Patients with complicated or severe disease require additional systemic antibiotics and evaluation by an otolaryngologist–head and neck surgeon. Patients benefit from counselling on proper otic drop technique and strategies to prevent recurrence.

Footnotes

Contributors

Janjulee Ellis completed the literature review, wrote the manuscript, and created the charts and associated figures. Dr Jason A. Beyea provided an otolaryngology perspective and expertise. Dr Allison De La Lis and Emily Rosen provided audiology perspectives. Drs Matthew T.W. Simpson and Michael M. Beyea contributed family medicine and emergency medicine contexts, respectively. All authors contributed to conducting the literature review and to preparing the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

Dr Jason A. Beyea is the owner and Medical Director of the Kingston Ear Institute, which provides services and products for hearing, balance, and vestibular loss. The other authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

This article is eligible for Mainpro+ certified Self-Learning credits. To earn credits, go to https://www.cfp.ca and click on the Mainpro+ link.

This article has been peer reviewed.

La traduction en français de cet article se trouve à https://www.cfp.ca dans la table des matières du numéro d’octobre 2024 à la page e140 .

References

- 1.Ostrowski VB, Wiet RJ.. Pathologic conditions of the external ear and auditory canal. Postgrad Med 1996;100(3):223-8, 233-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenfeld RM, Schwartz SR, Cannon CR, Roland PS, Simon GR, Kumar KA, et al. Clinical practice guideline: acute otitis externa. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014;150(1 Suppl):S1-24. Erratum in: Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014;150(3):504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hajioff D, MacKeith S.. Otitis externa. BMJ Clin Evid 2015;2015:0510. Epub 2015 Jun 15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Estimated burden of acute otitis externa—United States, 2003-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011;60(19):605-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rowlands S, Devalia H, Smith C, Hubbard R, Dean A.. Otitis externa in UK general practice: a survey using the UK General Practice Research Database. Br J Gen Pract 2001;51(468):533-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khatri H, Huang J, Guazzo E, Bond C.. Review article: topical antibiotic treatments for acute otitis externa: emergency care guidelines from an ear, nose and throat perspective. Emerg Med Australas 2021;33(6):961-5. Epub 2021 Sep 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hopkins ME, Bennett A, Henderson N, MacSween KF, Baring D, Sutherland R.. A retrospective review and multi-specialty, evidence-based guideline for the management of necrotising otitis externa. J Laryngol Otol 2020;134(6):487-92. Epub 2020 Jun 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beers SL, Abramo TJ.. Otitis externa review. Pediatr Emerg Care 2004;20(4):250-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roland PS, Stroman DW.. Microbiology of acute otitis externa. Laryngoscope 2002;112(7 Pt 1):1166-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaefer P, Baugh RF.. Acute otitis externa: an update. Am Fam Physician 2012;86(11):1055-61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sander R. Otitis externa: a practical guide to treatment and prevention. Am Fam Physician 2001;63(5):927-36, 941-2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martinez Devesa P, Willis CM, Capper JWR.. External auditory canal pH in chronic otitis externa. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 2003;28(4):320-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiegand S, Berner R, Schneider A, Lundershausen E, Dietz A.. Otitis externa. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2019;116(13):224-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim JK, Cho JH.. Change of external auditory canal pH in acute otitis externa. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2009;118(11):769-72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.OtoSim [website]. Toronto, ON: OtoSim Inc; 2024. Available from: https://otosim.com. Accessed 2024 Aug 26. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osguthorpe JD, Nielsen DR.. Otitis externa: review and clinical update. Am Fam Physician 2006;74(9):1510-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wipperman JM. Otitis externa. Prim Care 2014;41(1):1-9. Epub 2013 Dec 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kesser BW. Assessment and management of chronic otitis externa. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2011;19(5):341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roland PS. Chronic external otitis. Ear Nose Throat J 2001;80(6 Suppl):12-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Treviño González JL, Reyes Suárez LL, Hernández de León JE.. Malignant otitis externa: an updated review. Am J Otolaryngol 2021;42(2):102894. Epub 2021 Jan 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grandis JR, Branstetter BF 4th, Yu VL.. The changing face of malignant (necrotising) external otitis: clinical, radiological, and anatomic correlations. Lancet Infect Dis 2004;4(1):34-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hatch JL, Bauschard MJ, Nguyen SA, Lambert PR, Meyer TA, McRackan TR.. Malignant otitis externa outcomes: a study of the University HealthSystem Consortium Database. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2018;127(8):514-20. Epub 2018 Jul 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin TJ, Kerschner JE, Flanary VA.. Fungal causes of otitis externa and tympanostomy tube otorrhea. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2005;69(11):1503-8. Epub 2005 May 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee A, Tysome JR, Saeed SR.. Topical azole treatments for otomycosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021;5(5):CD009289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vennewald I, Klemm E.. Otomycosis: diagnosis and treatment. Clin Dermatol 2010;28(2):202-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McWilliams CJ, Smith CH, Goldman RD.. Acute otitis externa in children. Can Fam Physician 2012;58:1222-4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grandis JR, Curtin HD, Yu VL.. Necrotizing (malignant) external otitis: prospective comparison of CT and MR imaging in diagnosis and follow-up. Radiology 1995;196(2):499-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khan HA. Necrotising otitis externa: a review of imaging modalities. Cureus 2021;13(12):e20675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaushik V, Malik T, Saeed SR.. Interventions for acute otitis externa. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(1):CD004740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Balen FAM, Smit WM, Zuithoff NPA, Verheij TJM.. Clinical efficacy of three common treatments in acute otitis externa in primary care: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2003;327:1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenfeld RM, Singer M, Wasserman JM, Stinnett SS.. Systematic review of topical antimicrobial therapy for acute otitis externa. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2006;134(4 Suppl):S24-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polysporin Eye and Ear Drops. Markham, ON: Johnson & Johnson Inc. Available from: https://www.polysporin.ca/products/antibiotic-eye-drops. Accessed 2023 Jul 6. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Floxin Otic (ofloxacin otic solution 0.3%). Montvale, NJ: Daiichi Pharmaceutical Corporation; 2003. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2003/20799slr012_floxin_lbl.pdf. Accessed 2023 Jul 6. [Google Scholar]

- 34.DailyMed . Cetraxal - ciprofloxacin solution/drops. Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine; 2024. Available from: https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=213b339a-75e0-4b1d-9052-8ee82a65d713. Accessed 2024 Aug 8. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polysporin Plus Pain Relief Ear Drops. Markham, ON: Johnson & Johnson Inc. Available from: https://www.polysporin.ca/products/pain-relief-ear-drops?gad_source=1. Accessed 2023 Jul 6. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ciprodex (ciprofloxacin and dexamethasone), otic suspension. Fort Worth, TX: Alcon Laboratories; 2019. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/021537s017lbl.pdf. Accessed 2023 Jul 6. [Google Scholar]

- 37.CEDEC final recommendation and reasons for recommendation. Ciprofloxacin HCl and dexamethasone otic suspension (Ciprodex – Alcon Canada). Ottawa, ON: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2007. Available from: https://www.cda-amc.ca/sites/default/files/cdr/complete/cdr_complete_Ciprodex_October-18-2007.pdf. Accessed 2024 Sep 10. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Acetasol HC prescribing information. Dallas, TX: Drugs.com; 2024. Available from: https://www.drugs.com/pro/acetasol-hc.html. Accessed 2024 Aug 8. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cortisporin otic solution sterile (neomycin and polymyxin B sulfates and hydrocortisone otic solution, USP). New York, NY: Pfizer; 2020. Available from: https://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=707. Accessed 2023 Jul 6. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Otovel (ciprofloxacin and fluocinolone acetonide) otic solution. Atlanta, GA: Arbor Pharmaceuticals; 2016. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/208251orig1s000lbl.pdf. Accessed 2023 Jul 6. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Auro-Dri - isopropyl alcohol liquid. Tarrytown, NY: Insight Pharmaceuticals; 2020. Available from: https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/fda/fdaDrugXsl.cfm?setid=85cb4973-6a81-4d8f-b187-4bf709d93a98. Accessed 2024 Jun 5. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Locacorten Vioform eardrops (flumethasone pivalate 0.02% - clioquinol 1%). Montréal, QC: Paladin Labs; 2009. Available from: https://www.paladin-labs.com/our_products/Locacorten_Vioform_Eardrops_en.pdf. Accessed 2023 Jul 6. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao WT, Yang M, Wu HM, Yang L, Zhang XM, Huang Y.. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between sarcopenia and dysphagia. J Nutr Health Aging 2018;22(8):1003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chappe M, Vrignaud S, de Gentile L, Legrand G, Lagarce F, Le Govic Y.. Successful treatment of a recurrent Aspergillus niger otomycosis with local application of voriconazole. J Mycol Med 2018;28(2):396-8. Epub 2018 Apr 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abou-Halawa AS, Khan MA, Alrobaee AA, Alzolibani AA, Alshobaili HA.. Otomycosis with perforated tympanic membrane: self medication with topical antifungal solution versus medicated ear wick. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2012;6(1):73-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Torum B, Block SL, Avila H, Montiel F, Oliva A, Quintanilla W, et al. Efficacy of ofloxacin otic solution once daily for 7 days in the treatment of otitis externa: a multicenter, open-label, phase III trial. Clin Ther 2004;26(7):1046-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roland PS, Stewart MG, Hannley M, Friedman R, Manolidis S, Matz G, et al. Consensus panel on role of potentially ototoxic antibiotics for topical middle ear use: introduction, methodology, and recommendations. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004;130(3 Suppl):S51-6. Erratum in: Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004;131(1):20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chandrasekhar SS, Tsai Do BS, Schwartz SR, Bontempo LJ, Faucett EA, Finestone SA, et al. Clinical practice guideline: sudden hearing loss (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2019;161(S1):S1-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pond F, McCarty D, O’Leary S.. Randomized trial on the treatment of oedematous acute otitis externa using ear wicks or ribbon gauze: clinical outcome and cost. J Laryngol Otol 2002;116(6):415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bhutta MF, Head K, Chong LY, Daw J, Schilder AGM, Burton MJ, et al. Aural toilet (ear cleaning) for chronic suppurative otitis media. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;(9):CD013057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roland PS, Belcher BP, Bettis R, Makabale RL, Conroy PJ, Wall GM, et al. A single topical agent is clinically equivalent to the combination of topical and oral antibiotic treatment for otitis externa. Am J Otolaryngol 2008;29(4):255-61. Epub 2008 Mar 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu Z, Slim MAM, Scally C.. Otitis externa in secondary care: a change in our practice following a full cycle audit. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2018;22(3):250-2. Epub 2017 Sep 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang X, Winterstein AG, Li Y, Zhu Y, Antonelli PJ.. Use of systemic antibiotics for acute otitis externa: impact of a clinical practice guideline. Otol Neurotol 2018;39(9):1088-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lambor DV, Das CP, Goel HC, Tiwari M, Lambor SD, Fegade MV.. Necrotising otitis externa: clinical profile and management protocol. J Laryngol Otol 2013;127(11):1071-7. Epub 2013 Oct 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arsovic N, Radivojevic N, Jesic S, Babac S, Cvorovic L, Dudvarski Z.. Malignant otitis externa: causes for various treatment responses. J Int Adv Otol 2020;16(1):98-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mösges R, Schröder T, Baues CM, Şahin K.. Dexamethasone phosphate in antibiotic ear drops for the treatment of acute bacterial otitis externa. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24(8):2339-47. Epub 2008 Jul 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mösges R, Domröse CM, Löffler J.. Topical treatment of acute otitis externa: clinical comparison of an antibiotics ointment alone or in combination with hydrocortisone acetate. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2007;264(9):1087-94. Epub 2007 May 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]