Abstract

Delivering attenuated lentivirus vaccines as proviral DNA would be simple and inexpensive. Inoculation of macaques with wild-type simian immunodeficiency virus strain mac239 (SIVmac239) DNA or SIVmac239 DNA containing a single deletion in the 3′ nef-long terminal repeat overlap region (nef/LTR) led to sustained SIV infections and AIDS. Injection of SIVmac239 DNA containing identical deletions in both the 5′ LTR and 3′ nef/LTR resulted in attenuated SIV infections and substantial protection against subsequent mucosal SIVmac251 challenge.

nef-deletion-containing live-attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) vaccines have been shown to be efficacious in macaques (3). However, a proportion of macaques and humans become immunodeficient following infection with nef-deletion-containing SIV or human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) strains (1, 4, 13). Should modified attenuated lentivirus vaccines eventually prove safe (17), delivering such viruses to large numbers of people in developing countries raises logistical problems, including quality control and cold-chain issues. These difficulties would be overcome if an infection with an attenuated HIV-1 vaccine could be initiated via proviral plasmid DNA. Pathogenic lentiviral infection of cats following wild-type feline immunodeficiency virus DNA inoculation and of macaques following SIVmac239 DNA inoculation have been induced by the intramuscular administration of 50 to 500 μg of DNA (7, 14, 16, 21). Attenuating deletions in the 5′ long terminal repeat (LTR) (which drives the initial round of transcription) affect the initial expression of reporter genes in macaques and in human skin ex vivo (9) and could render the 5′-LTR-deletion-containing constructs noninfectious in vivo. The utility of proviral DNA in initiating an attenuated SIV infection was therefore studied in macaques.

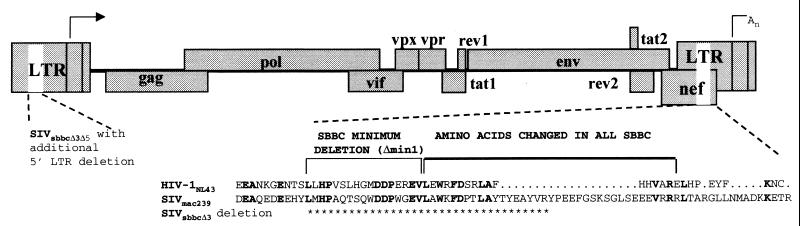

Proviral SIV constructs with either a single deletion in the 3′ nef-LTR overlap region (nef/LTR) (SIVsbbcΔ3) analogous to the common deletion observed in HIV-1 strains isolated from the Sydney Blood Bank Cohort (SBBC) or an additional identical deletion in the 5′ LTR (SIVsbbcΔ3Δ5) were engineered into a low-copy-number vector, pKP55, kindly provided by K. Peden (Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, Food and Drug Administration, Bethesda, Md.) (Fig. 1). The distal half of the SIVmac239 provirus, 3′ to the SphI site (position 6446, GenBank accession no. M33262), was cut with SphI and EcoRI from plasmid p239SpE3′ (contributed to the National Institutes of Health AIDS reagent repository by R. Desrosiers) and ligated into the unique sites of the pKP55 vector (5, 12). A 105-bp in-frame nef/LTR deletion from position 9657 that removes U3 sequences always changed in or deleted from HIV-1 strains from the SBBC (4, 6) was engineered using a Quick Change mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) with the oligonucleotide Δmin2F (CAGGAGGATGAGGAGCATTATTACCCAGAAGAGTTTGGAAGC) and its reverse complement, Δmin2R, to make plasmid pKP-SIV-3′Δmin2. The 5′ half of SIVmac239 was cut from p239SpSp5′ with SphI and cloned into the SphI-linearized plasmids to make one plasmid with full-length SIVmac239 and one with a 3′ nef/LTR deletion (pSIVsbbcΔ3). To make pSIVsbbcΔ5Δ3, the 5′ LTR was deleted from position 194 of p239SpSp5′ using oligonucleotides Δmin2F and Δmin2R and cloned into pKP-SIV-3′Δmin2. The constructs were confirmed to be correct by cloning and sequencing. Transfection stocks of both wild-type and nef/LTR-deletion-containing SIV constructs grew equally well, as determined by a reverse transcriptase (RT) assay (19) in CEMx174 cells in vitro (data not shown). The nef/LTR-deletion-containing SIVsbbc constructs did not express detectable Nef protein by immunoblotting (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

SIVmac239-based plasmids. Asterisks denote the 105-bp (35-amino-acid) deletion in the 3′ nef/LTR of construct SIVsbbcΔ3. A further, identical deletion in the 5′ LTR was made in SIVsbbcΔ3Δ5. The deletion in SIV nef/LTR is analogous to most of the shared nef/LTR sequence deletions present in HIV-1 strains found in the SBBC (4); amino acids common to Nef in both HIV-1NL4-3 and SIVmac239 are noted in bold.

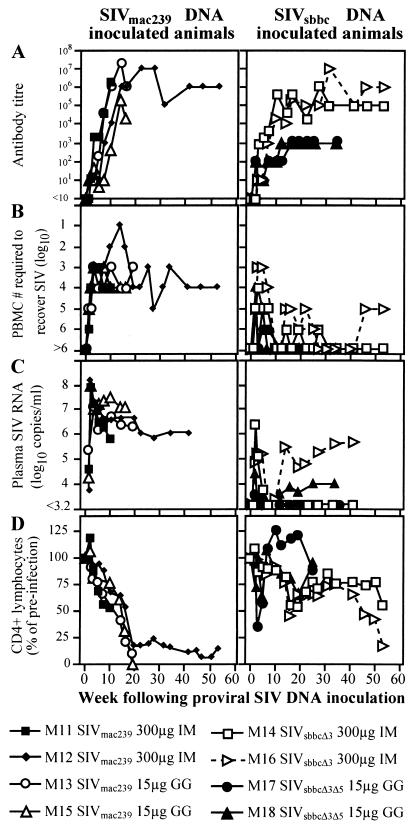

Eight pigtailed macaques were inoculated with wild-type or nef/LTR-deletion-containing SIV DNA constructs, delivered either intramuscularly (300 μg) or epidermally via gene gun (only 15 μg) (Fig. 2). All animals were shown to have seroconverted to HIV-2 antigens by Western blotting (not shown) and a particle agglutination assay (Serodia HIV-1/2; Fujirebio, Tokyo, Japan) (Fig. 2A). SIV was recovered from phytohemagglutinin- and interleukin-2-activated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of all inoculated animals by coculture with CEMx174 cells (Fig. 2B). The four SIVsbbc-inoculated animals required more input PBMC (>104) to recover SIV than did the four animals receiving SIVmac239. Plasma SIV RNA was measured either by bDNA analysis (Bayer Diagnostics, Emeryville, Calif.) or real-time RT-PCR as previously described (8). Both SIV RNA assays had a lower limit of detection of 1,500 copies/ml and had similar quantification levels. SIVmac239 DNA-inoculated macaques had higher peak levels of SIV RNA in plasma than SIVsbbc-inoculated macaques (Fig. 2C). SIVmac239-inoculated animals maintained SIV RNA levels of >106 copies/ml and were euthanized at weeks 11, 19, 20, and 53, showing SIV-associated coagulopathy, septicemia, and weight loss (two animals) with a marked decline in peripheral CD4+ lymphocytes measured by flow cytometry (11) (Fig. 2D). No attenuation of virulence was observed in the gene gun-inoculated animals despite the low dose of DNA administered.

FIG. 2.

SIV infection of macaques by administration of SIV proviral DNA. Plasmids, doses, and routes (GG, epidermally via a gene gun; IM, intramuscularly) are noted in the key. (A) SIV antibody response by endpoint dilution. (B) Quantification of cell-associated SIV. The lowest numbers of PBMC required to recover SIV are shown. For some cultures (M11, weeks 3 and 5; M12, weeks 3, 5, 7, 10, and 14; M13, weeks 3 and 10; M15, week 7; M16, weeks 3 and 5), SIV was recovered from the lowest cell dilution assayed. (C) Plasma SIV RNA levels. Plasma was assayed for SIV RNA by bDNA analysis, except M17 at weeks 10, 19, and 34 following inoculation and M18 at weeks 19 and 34 following inoculation, which were assayed by real-time RT-PCR. (D) CD4+ lymphocyte proportions. Serial PBMC samples were assayed for the proportion of CD4+ lymphocytes in the CD2+ lymphocyte population, and these values were compared to mean preinoculation levels standardized to 100%.

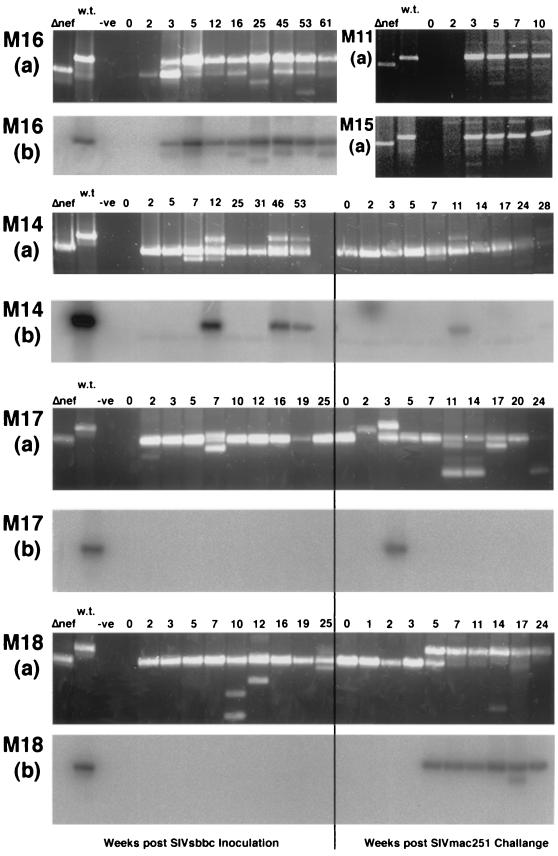

Macaques given the SIVsbbc plasmids had SIV RNA levels that fell below the detection threshold by week 7 following inoculation and remained low or stable in three of the four animals, which also had normal CD4+ lymphocyte levels (Fig. 2C and D). However, SIV RNA levels in macaque M16, inoculated with SIVsbbcΔ3, rose to >4 × 105 copies/ml by week 46, and this animal subsequently had a decline in CD4+ lymphocyte numbers and was euthanized with weight loss at week 61. To determine the cause of the loss of CD4+ lymphocytes in M16, nested-PCR analysis of SIV DNA from lysed PBMC was performed using oligonucleotide primers from positions 9129 to 9148 and 10016 to 10036 for the first round and primers from positions 9191 to 9208 and 9872 to 9890 for the nested round. Nested PCR amplified wild-type size SIV nef/LTR from week 3 following SIV inoculation and thereafter (Fig. 3, panel M16a). These wild-type-sized PCR fragments hybridized with a probe (oligonucleotide GTCATCCCACTGGGAAGTTTGAGCTG) internal to the nef/LTR deletion by Southern blotting, suggesting that a considerable wild-type sequence was present (Fig. 3, panel M16b). Additionally, M16, but not other SIVsbbc-inoculated animals, seroconverted to recombinant SIVmac239 Nef (supplied by AIDS reagent project, National Institute of Biological Standards and Control, Potters Bar, United Kingdom) by enzyme immunoassay (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 3.

PCR analysis of the SIV nef/LTR. (Panels a) Gel electrophoresis of PCR-amplified SIV proviral DNA isolated from macaque PBMC at various weeks following SIV plasmid DNA inoculation. As controls, nef/LTR PCR fragments were amplified from a control SIVmac239 plasmid bearing the wild-type (w.t.) sequence or the 105-bp SBBC strain deletion in SIV nef/LTR (Δnef). A wild-type-sized PCR product obtained after 25 cycles of PCR is shown from PBMC of two representative macaques, M11 and M15, that were inoculated with wild-type SIVmac239 plasmid DNA. Animals M14, M17, and M18 were challenged with SIVmac251 intrarectally at 68 weeks (M14) or 34 weeks (M17 and M18), and lanes with results for samples taken at these times are labeled week 0 to the right of the vertical line. (Panels b) Southern blotting of nested-PCR products from M16, M14, M17, and M18 probed with an oligonucleotide located within the nef/LTR deletion.

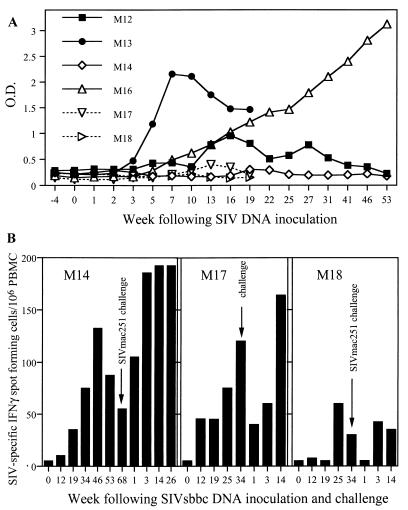

FIG. 4.

(A) SIV Nef-specific antibodies following SIV DNA inoculation of macaques. Antibodies were detected against whole recombinant SIV Nef by enzyme immunoassay. Wild-type SIVmac239 DNA-inoculated animals M12 and M13 (closed symbols) had detectable anti-Nef antibodies, but only monkey M16 of the SIVsbbc-inoculated animals developed anti-Nef antibodies. O.D., optical density. (B) ELISPOT detection of SIV-specific IFN-γ production by PBMC from SIVsbbc-vaccinated macaques prior to, and following, SIVmac251 challenge.

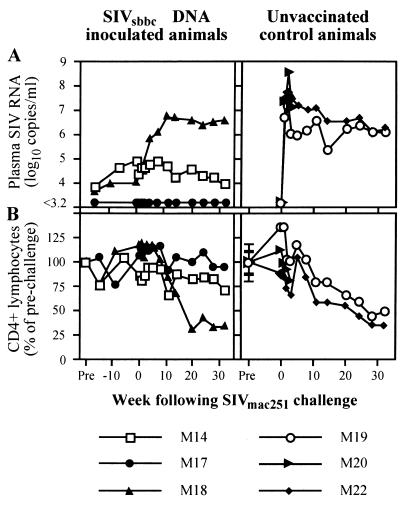

To determine if the attenuated SIV infections initiated by proviral DNA inoculation could protect simians from a pathogenic challenge, the remaining three SIVsbbc-inoculated animals and three naïve controls were challenged intrarectally with a stock of highly infectious SIVmac251 (20; R. Pal, submitted for publication). All control animals were shown to have seroconverted by particle agglutination assay and Western blotting (not shown). SIV was recovered by coculture from 104 or fewer of their PBMC (not shown), and their peak SIV RNA levels were high (>107 copies/ml) (Fig. 5A). One control animal (M20) developed diarrhea and weight loss and was euthanized 3 weeks after infection. The other two control animals (M19 and M22) had a progressive decline in CD4+ T cells over a 32-week period (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Virologic and immunologic outcome of SIVmac251 challenge of SIVsbbc-inoculated macaques and controls. (A) Plasma SIV RNA levels as measured by real-time RT-PCR. (B) CD4+ lymphocyte numbers are percentages of prechallenge counts.

All three macaques vaccinated with SIVsbbc strains via DNA injection were protected from the high peak level of SIV RNA observed in the control animals 1 to 3 weeks following SIVmac251 challenge (Fig. 5A). However, progressively higher SIV RNA levels were detected in M18 over the first 11 weeks following SIVmac251 challenge and subsequently had a progressive decline in CD4+ lymphocytes (Fig. 5). PCR of PBMC isolated from M18 following challenge demonstrated a wild-type-sized nef/LTR band that was shown to hybridize with an internal probe by Southern blotting and progressively became the dominant species (Fig. 3, panels M18). The two other SIVsbbc- inoculated macaques, M14 and M17, were protected from SIVmac251 challenge, as they maintained low SIV RNA levels, stable CD4+ lymphocyte levels, and a continued predominance of the PCR band of the nef/LTR deletion construct (Fig. 5 and 3, panels M14 and M17). Although protection was observed in two of three vaccinated animals, the small sample size meant that the result did not reach statistical significance (two sided, P = 0.40, Fisher's exact test).

To assess potential correlates of immunity, PBMC from vaccinated animals were assessed for the production of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) by ELISPOT (U-CyTech bv, Utrecht, The Netherlands) (2) in response to overnight stimulation with a 10-μg/ml concentration of whole Aldrithiol-2-inactivated SIVmne or control microvesicles purified from the cell lines used to grow SIVmne (kindly supplied by J. Lifson, National Cancer Institute, Frederick, Md. [15]). Antigen-stimulated PBMC (2 × 105/well) were incubated for 5 h in anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibody-coated ELISPOT plates, and spots were detected using labeled anti-biotin antibodies. The number of spot-forming cells in control wells was always ≤20/106 PBMC. Although the numbers of animals were small, PBMC from animals protected from SIVmac251 challenge (M14 and M17) had consistently high levels of production of IFN-γ in response to SIV antigen stimulation both prior to and following SIVmac251 challenge, which may have played a role in the protective immunity observed (Fig. 4B). The rise in T-cell responses following challenge most likely reflects the nonsterilizing immunity and is consistent with the transient detection of wild-type-sized SIV DNA in M17 early on following challenge (Fig. 3), as observed in previous studies (10, 11).

In summary, we showed that attenuated SIV infections capable of stimulating SIV-specific T- and B-cell responses and protecting a proportion of monkeys against a virulent challenge can be initiated easily and reliably with inoculation of as little as 15 μg of proviral DNA. If live attenuated HIV vaccine strategies are ultimately proven to be safe (e.g., with the use of genes capable of turning replication on or off, as shown by Marzio et al. [17]), they could be delivered in the field using proviral DNA solutions rather than virus suspensions. Our studies also demonstrate that attenuating LTR mutations need to be engineered into both 5′ and 3′ proviral LTRs to prevent a rapid reversion to wild-type virus during in vivo replication, as detected in macaque M16. Although live attenuated lentiviral vaccines are currently insufficiently attenuated for use in humans (18), should current protein- and vector-based HIV-1 vaccines prove ineffective in clinical trials, our studies suggest practical and economical methods for developing and delivering attenuated lentivirus vaccines.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge A. Joy, R. Sydenham, S. Lee, N. Deacon, D. McPhee, S. Crowe, M. Law, A. Solomon, P. Cameron, and S. Lewin for providing excellent technical assistance and advice.

This study was supported by the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative, the Macfarlane Burnet Centre Research Fund, the National Centre for HIV Virology Research (J.M.), and Commonwealth AIDS Research Grants of Australia 956043 (S.J.K.) and 111700 (D.F.J.P.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Baba T W, Jeong Y S, Pennick D, Bronson R, Greene M F, Ruprecht R M. Pathogenicity of live, attenuated SIV after mucosal infection of neonatal macaques. Science. 1995;267:1820–1825. doi: 10.1126/science.7892606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dale C J, Zhao A, Jones S L, Boyle D B, Ramshaw I A, Kent S J. Induction of HIV-1-specific T-helper responses and type 1 cytokine secretion following therapeutic vaccination of macaques with a recombinant fowlpoxvirus co-expressing interferon-gamma. J Med Primatol. 2000;29:240–247. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0684.2000.290317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daniel M D, Kirchhoff F, Czajak S C, Sehgal P K, Desrosiers R C. Protective effects of a live attenuated SIV vaccine with a deletion in the nef gene. Science. 1992;258:1938–1941. doi: 10.1126/science.1470917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deacon N J, Tsykin A, Solomon A, Smith K, Ludford-Menting M, Hooker D J, McPhee D A, Greenway A L, Ellett A, Chatfield C, Lawson V A, Crowe S, Maerz A, Sonza S, Learmont J, Sullivan J S, Cunningham A, Dwyer D, Dowton D, Mills J. Genomic structure of an attenuated quasi species of HIV-1 from a blood transfusion donor and recipients. Science. 1995;270:988–991. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibbs J S, Regier D A, Desrosiers R C. Construction and in vitro properties of SIVmac mutants with deletions in nonessential genes. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1994;10:333–342. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenway A L, Mills J, Rhodes D, Deacon N J, McPhee D A. Serological detection of attenuated HIV-1 variants with nef gene deletions. AIDS. 1998;12:555–561. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199806000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ilyinskii P O, Simon M A, Czajak S C, Lackner A A, Desrosiers R C. Induction of AIDS by simian immunodeficiency virus lacking NF-κB and SP1 binding elements. J Virol. 1997;71:1880–1887. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1880-1887.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin X, Bauer D E, Tuttleton S E, Lewin S, Gettie A, Blanchard J, Irwin C E, Safrit J T, Mittler J, Weinberger L, Kostrikis L G, Zhang L, Perelson A S, Ho D D. Dramatic rise in plasma viremia after CD8+ T cell depletion in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J Exp Med. 1999;189:991–998. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.6.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kent S J, Cameron P U, Reece J C, Thomson P, Purcell D F. Attenuated and wild type HIV-1 infections and long terminal repeat mediated gene expression from plasmids delivered by gene gun to human skin ex vivo and macaques in vivo. Virology. 2001;287:71–78. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kent S J, Hu S-L, Corey L, Morton W R, Greenberg P D. Detection of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-specific CD8+ T cells in macaques protected from SIV challenge by prior SIV subunit vaccination. J Virol. 1996;70:4941–4947. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.4941-4947.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kent S J, Zhao A, Best S J, Chandler J D, Boyle D B, Ramshaw I A. Enhanced T-cell immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vaccine regimen consisting of consecutive priming with DNA and boosting with recombinant fowlpox virus. J Virol. 1998;72:10180–10188. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.10180-10188.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kestler H W, Ringler D J, Mori K, Panicali D L, Sehgal P K, Daniel M D, Desrosiers R C. Importance of the nef gene for maintenance of high virus loads and for development of AIDS. Cell. 1991;65:651–662. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90097-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Learmont J C, Geczy A F, Mills J, Ashton L J, Raynes-Greenow C H, Garsia R J, Dyer W B, McIntyre L, Oelrichs R B, Rhodes D I, Deacon N J, Sullivan J S, McPhee D A, Crowe S, Solomon A E, Chatfield C, Cooke I R, Blasdall S, Kuipers H. Immunologic and virologic status after 14 to 18 years of infection with an attenuated strain of HIV-1—a report from the Sydney Blood Bank Cohort. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1715–1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906033402203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Letvin N L, Lord C I, King N W, Wyand M S, Myrick K V, Haseltine W A. Risks of handling HIV. Nature. 1991;349:573. doi: 10.1038/349573a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lifson J D, Rossio J L, Arnaout R, Li L, Parks T L, Schneider D K, Kiser R F, Coalter V J, Walsh G, Imming R J, Fisher B, Flynn B M, Bischofberger N, Piatak M, Jr, Hirsch V M, Nowak M A, Wodarz D. Containment of simian immunodeficiency virus infection: cellular immune responses and protection from rechallenge following transient postinoculation antiretroviral treatment. J Virol. 2000;74:2584–2593. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.6.2584-2593.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liska V, Khimani A H, Hofmann-Lehmann R, Fink A N, Vlasak J, Ruprecht R M. Viremia and AIDS in rhesus macaques after intramuscular inoculation of plasmid DNA encoding full-length SIVmac239. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1999;15:445–450. doi: 10.1089/088922299311196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marzio G, Verhoef K, Vink M, Berkhout B. In vitro evolution of a highly replicating, doxycycline-dependent HIV for applications in vaccine studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6342–6347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111031498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mills J, Desrosiers R, Rud E, Almond N. Live attenuated HIV vaccines: a proposal for further research and development. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2000;16:1453–1461. doi: 10.1089/088922200750005976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Purcell D F J, Martin M A. Alternative splicing of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mRNA modulates viral protein expression, replication, and infectivity. J Virol. 1993;67:6365–6378. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6365-6378.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romano J W, Shurtliff R N, Dobratz E, Gibson A, Hickman K, Markham P D, Pal R. Quantitative evaluation of simian immunodeficiency virus infection using NASBA technology. J Virol Methods. 2000;86:61–70. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(99)00184-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sparger E E, Louie H, Ziomeck A M, Luciw P A. Infection of cats by injection with DNA of a feline immunodeficiency virus molecular clone. Virology. 1997;238:157–160. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]