Abstract

Background

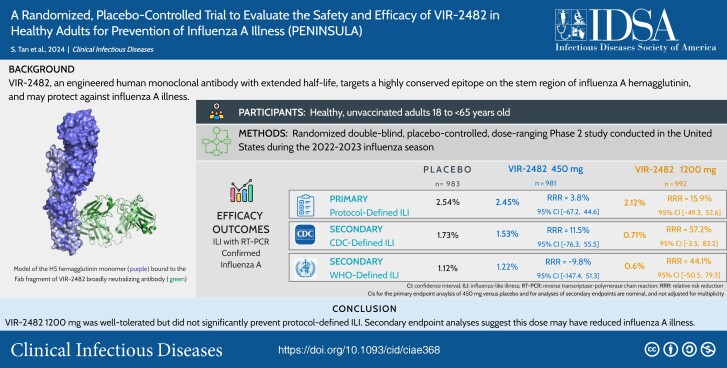

Influenza A results in significant morbidity and mortality. VIR-2482, an engineered human monoclonal antibody with extended half-life, targets a highly conserved epitope on the stem region of influenza A hemagglutinin and may protect against seasonal and pandemic influenza.

Methods

This double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study examined the safety and efficacy of VIR-2482 for seasonal influenza A illness prevention in unvaccinated healthy adults. Participants (N = 2977) were randomized 1:1:1 to receive VIR-2482 450 mg, VIR-2482 1200 mg, or placebo via intramuscular injection. Primary and secondary efficacy endpoints were the proportions of participants with reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction–confirmed influenza A infection and either protocol-defined influenza-like illness (ILI) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–defined ILI or World Health Organization–defined ILI, respectively.

Results

VIR-2482 450 mg and 1200 mg prophylaxis did not reduce the risk of protocol-defined ILI with reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction–confirmed influenza A versus placebo (relative risk reduction, 3.8% [95% confidence interval (CI), −67.3 to 44.6] and 15.9% [95% CI, −49.3 to 52.3], respectively). At the 1200-mg dose, the relative risk reductions in influenza A illness were 57.2% (95% CI: −2.5 to 82.2) using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ILI and 44.1% (95% CI: −50.5 to 79.3) using World Health Organization ILI definitions, respectively. Serum VIR-2482 levels were similar regardless of influenza status; variants with reduced VIR-2482 susceptibility were not detected. Local injection site reactions were mild and similar across groups.

Conclusions

VIR-2482 1200 mg intramuscular was well tolerated but did not significantly prevent protocol-defined ILI. Secondary endpoint analyses suggest this dose may have reduced influenza A illness.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT05567783.

Keywords: influenza A, monoclonal antibody, VIR-2482, seasonal influenza prevention, phase 2 clinical trial

Prophylactic administration of 1200 mg of VIR-2482, an engineered human monoclonal antibody targeting a highly conserved epitope on the stem region of influenza A hemagglutinin, did not significantly reduce risk of influenza-like illness from influenza A virus in healthy adults.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

This graphical abstract is also available at Tidbit: https://tidbitapp.io/tidbits/a-randomized-placebo-controlled-trial-to-evaluate-the-safety-and-efficacy-of-vir-2482-in-healthy-adults-for-prevention-of-influenza-a-illness-peninsula-5591c84c-e394-4788-af48-4b317660ef10?utm_campaign=tidbitlinkshare&utm_source=ITP

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 1 billion annual cases of seasonal influenza occur globally. Of these, an estimated 3 to 5 million cases are severe, with up to 650 000 deaths per year [1]. Influenza A and B are both responsible for seasonal epidemics, but influenza A infections account for the majority of hospitalizations and are the only influenza type to cause pandemics [2]. Some patient groups are at high risk of influenza-associated hospitalizations and mortality, including the elderly, immunocompromised hosts, and those with certain comorbidities [3–5].

Currently available seasonal influenza vaccines are influenza strain–specific, incompletely protective because of strain mismatch, and often inadequately immunogenic, especially in high-risk groups, such as the elderly and immunocompromised [6]. Specifically, vaccine effectiveness against medically attended influenza illness ranged from 19% to 60% in the United States between the 2009 to 2023 influenza seasons [7]. Therefore, we hypothesized that an immunoprophylactic antibody with long half-life and activity against a broad range of influenza A viruses could provide greater protection and obviate the need for updates to match the prevalent circulating strains, especially in individuals at high risk of complications. Additionally, such a neutralizing antibody could facilitate a rapid response to an influenza A pandemic [8].

VIR-2482 is a neutralizing, engineered human immunoglobulin G monoclonal antibody (mAb) that targets a highly conserved epitope on the stem region of the influenza A hemagglutinin (HA) protein [9, 10]. Epidemiologically, HA-stem binding antibodies have been shown to correlate with protection from illness [11] and are the focus of ongoing efforts to create universal influenza vaccines [8, 12].

VIR-2482 and its parent mAb bind to HAs representing all 18 influenza A subtypes and neutralize a broad panel of H1N1 and H3N2 influenza viruses spanning >100 years of antigenic evolution. Administration of VIR-2482 reduced morbidity and mortality from infection by seasonal and zoonotic strains of influenza in mice, ferrets, and macaques [9, 13–15]. VIR-2482 is engineered to include an Fc LS mutation (M428L/N434S) that extends the elimination half-life (T1/2) through increased FcRn-mediated antibody recirculation [9].

In a phase 1 study in healthy volunteers (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04033406), VIR-2482 doses of 60 to 1800 mg via intramuscular injection showed favorable local and systemic tolerability, with few injection site reactions [10]. Median time to maximum plasma concentration of VIR-2482 ranged from 7.0 to 12.5 days, and median plasma T1/2 was 57.1 to 70.6 days across dosing cohorts, indicating the potential for administration once per influenza season.

We undertook this proof-of-concept, phase 2 trial to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of VIR-2482 in preventing influenza A illness in healthy adults who had not received a seasonal influenza vaccine. Because vaccination was prohibited, participants were required to be at low risk of developing serious influenza-related complications.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study conducted at 53 centers in the United States during the 2022 to 2023 Northern Hemisphere influenza season. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was approved by the relevant institutional ethics committees (authorizing body: WCG institutional review board). All participants provided written informed consent.

Participants

Males and nonpregnant/nonlactating females aged 18 to <65 years were eligible to participate if they were in good health as determined from medical history. Key inclusion criteria included body mass index 18.0 to 35.0 kg/m2 and no clinically significant findings from physical examination, 12-lead electrocardiogram, and laboratory values. Participants were excluded if they had previous or planned receipt of any influenza vaccine for the upcoming season, history or clinical evidence of conditions considered high risk for developing influenza-related complications, or confirmed influenza infection within 3 months of randomization (see Supplementary Methods).

Antibody Administration and Safety Monitoring

VIR-2482 or saline placebo was administered as 2 separate 4-mL intramuscular injections. Participants were randomized 1:1:1 to VIR-2482 450 mg (1 dose of VIR-2482 and 1 dose of placebo), VIR-2482 1200 mg (2 doses of VIR-2482), or placebo (2 doses of placebo) on day 1. These doses were selected based on the acceptable safety and tolerability of VIR-2482 doses in the phase 1 study and target serum concentrations estimated from in vitro neutralization data [10]. VIR-2482 was administered as a 150-mg/mL solution. The preferred injection site was the thigh, with the buttock as an alternative.

Participants remained at the clinical study site for ≥2 hours postdose to assess safety, including solicited local tolerability at the injection sites performed at 1 hour postdose. Following discharge, participants completed an electronic diary card from days 1 to 7 to record injection site and systemic reactions and body temperature. Follow-up visits were conducted at 1, 4, and 12 weeks postdosing and at the end of the influenza season (EOIS).

Adverse events (AEs) were recorded through the end of the study, with severity assessed according to the Toxicity Grading Scale for Healthy Adult and Adolescent Volunteers Enrolled in Preventive Vaccine Clinical Trials [16]. Immunogenicity of VIR-2482 was evaluated according to incidence and titers of antidrug antibodies (ADAs) using validated methods [10].

Illness Surveillance

Participants completed an electronic diary for influenza-like illness (ILI) symptoms twice per week from day 1 through EOIS (16 April 2023). Signs and symptoms included sore throat, cough, sputum production, wheezing, difficulty breathing, temperature >37.8°C, chills, weakness, or myalgia. Participants experiencing any ILI symptoms were requested to visit the study center within 3 days of symptom onset for nasopharyngeal swab (NPS) collection. Influenza A was confirmed by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using a sponsor-provided point-of-care device (Xpert Xpress CoV-2/Flu/RSV plus; Cepheid; Sunnyvale, CA) or a central virology laboratory assay (Respiratory Panel 1; Seegene; Seoul, South Korea) performed at DDL Diagnostic Laboratories (Rijswijk, Netherlands). Noninfluenza respiratory viruses were also confirmed by RT-PCR. Participants with ILI were managed according to local standard of care, and symptoms were followed up daily via telephone through day 10 following initial presentation. Symptom severity of ILI was documented using the Influenza Intensity and Impact Questionnaire (Flu-iiQ) [17] administered from day 1 of symptom onset through day 10.

Pharmacokinetics

Serum samples for pharmacokinetics (PK) and immunogenicity analyses were collected predose and at the follow-up visits. NPS for PK analysis [10] were collected from all participants at the EOIS visit and at weeks 1, 4, and 12 from a subset of participants in an optional PK substudy. In participants with ILI, additional samples for PK, ADA, and virologic analyses were collected at the ILI confirmation clinic visit.

Outcomes

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of participants with RT-PCR positivity for influenza A and protocol-defined ILI. The protocol definition required ≥1 respiratory symptom (sore throat, cough, sputum production, wheezing, or difficulty breathing) and ≥1 systemic sign or symptom (temperature >37.8°C, chills, weakness, or myalgia). Prespecified secondary efficacy endpoints were the proportions of participants with RT-PCR–confirmed influenza A and ILI as defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; temperature >37.8°C with sore throat or cough and RT-PCR confirmation) and WHO (temperature >38°C with cough and RT-PCR confirmation).

Exploratory endpoints included the severity and duration, as the time of onset of the first symptom through when all respiratory symptoms were resolved for ≥24 hours, of participant-reported ILI signs and symptoms with the Flu-iiQ instrument [17]. Virologic analyses on NPS samples determined the proportion of participants with RT-PCR–confirmed influenza A by virus subtype and assessed the emergence of virus variants with reduced susceptibility to VIR-2482. Next-generation sequencing of the influenza A HA gene was performed at DDL Diagnostic Laboratories (Rijswijk, Netherlands). Virus successfully cultured in MDCK cells was assessed for reduced susceptibility using an in vitro neutralization assay at Viroclinics Biosciences (Rotterdam, Netherlands) [18]. Sequence and phenotypic results were compared with respective subtype vaccine reference strains (H1N1: A/Victoria/2750/2019; H3N2: A/Darwin/9/2021 and A/Darwin/6/2021, respectively).

Statistical Analysis

A sample size of approximately 3000 participants was needed to provide approximately 80% power to detect VIR-2482 efficacy (a true relative risk reduction [RRR] of 70%) of 1 VIR-2482 dose level compared with placebo, assuming an attack rate of ≥2.25% in the placebo group [19, 20]. Efficacy and safety were analyzed in all randomized participants receiving any amount of study drug or placebo. Efficacy was assessed based on the study intervention to which participants were randomly assigned; safety was assessed based on the intervention received. Details on primary and secondary estimands and statistical analyses are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

A modified Poisson regression with robust variance was used as the efficacy analysis model to estimate the relative risk of the incidence of protocol-/CDC-/WHO-defined ILI with RT-PCR–confirmed influenza A in each VIR-2482 group compared with the placebo group, with treatment group as the only factor in each model. A hierarchical fixed-sequence testing procedure was used to control the overall type I error as outlined in the Supplementary Methods. Formal comparisons precluded by the hierarchical testing strategy were considered descriptive.

RESULTS

Participants and Disposition

Between 13 October 2022 and 6 January 2023, participants (N = 2977) were randomized, and 2956 (99.3%) received study intervention (Figure 1). Across treatment groups, mean age was 39.5 years and 54% were female (Table 1). Study drug or placebo was administered in the thigh in approximately 78% of participants. Through the end of study, discontinuation rates were <5% and comparable across treatment groups.

Figure 1.

Participant disposition. Based on efficacy findings, the study was terminated early and follow-up into the second influenza season did not take place.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics (Full Analysis Set)

| Placebo (n = 983) | VIR-2482 450 mg (n = 981) | VIR-2482 1200 mg (n = 992) | Total (n = 2956) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at randomization, y | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 39.7 (12.3) | 39.2 (12.5) | 39.6 (11.7) | 39.5 (12.2) |

| Median (range) | 39.0 (18–64) | 38.0 (18–64) | 39.0 (18–64) | 39.0 (18–64) |

| Sex, no. (%) | ||||

| Male | 453 (46.1) | 436 (44.4) | 469 (47.3) | 1358 (45.9) |

| Female | 530 (53.9) | 545 (55.6) | 523 (52.7) | 1598 (54.1) |

| Race, no. (%) | ||||

| American Indian or Alaskan native | 7 (0.7) | 7 (0.7) | 7 (0.7) | 21 (0.7) |

| Asian | 26 (2.6) | 26 (2.7) | 29 (2.9) | 81 (2.7) |

| Black or African American | 166 (16.9) | 154 (15.7) | 176 (17.7) | 496 (16.8) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 4 (0.4) | 5 (0.5) | 4 (0.4) | 13 (0.4) |

| White | 758 (77.1) | 752 (76.7) | 747 (75.3) | 2257 (76.4) |

| Multiracial | 6 (0.6) | 17 (1.7) | 11 (1.1) | 34 (1.2) |

| Not reported/unknown | 16 (1.6) | 20 (2.0) | 18 (1.8) | 54 (1.8) |

| Ethnicity, no. (%) | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 357 (36.3) | 370 (37.7) | 370 (37.3) | 1097 (37.1) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 620 (63.1) | 607 (61.9) | 621 (62.6) | 1848 (62.5) |

| Not reported/unknown | 6 (0.6) | 4 (0.4) | 1 (0.1) | 11 (0.4) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 27.2 (4.1) | 27.3 (4.1) | 27.4 (4.2) | 27.3 (4.1) |

| Median (range) | 27.2 (18.0–35.0) | 27.5 (18.0–36.6) | 27.7 (18.0–35.1) | 27.5 (18.0–36.6) |

| Injection site location, no. (%) | ||||

| Thigh | 762 (77.5) | 757 (77.2) | 783 (78.9) | 2302 (77.9) |

| Buttock | 219 (22.3) | 223 (22.7) | 207 (20.9) | 649 (22.0) |

Efficacy Outcomes

The primary endpoint of protocol-defined ILI with RT-PCR–confirmed confirmed influenza A was observed in similar numbers of participants across groups (Table 2). A nonsignificant RRR of 15.9% (95% confidence interval [CI]: −49.3 to 52.6) comparing VIR-2482 1200 mg versus placebo was observed. Predefined subgroup analyses between these 2 groups showed RRRs consistent with that of the overall population (Supplementary Figure 1). In the VIR-2482 1200-mg group, RRRs versus placebo for CDC- and WHO-defined ILI with RT-PCR–confirmed influenza A were 57.2% (95% CI: −2.5 to 82.2) and 44.1% (95% CI: −50.5 to 79.3), respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Occurrence of Influenza-Like Illness With RT-PCR–Confirmed Influenza A Through End of Influenza Season (Full Analysis Set)

| Placebo (n = 983) | VIR-2482 450 mg (n = 981) | VIR-2482 1200 mg (n = 992) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary endpoint | |||

| No. (%) participants with protocol-defined ILIa | 25 (2.54) | 24 (2.45) | 21 (2.12) |

| RRR vs placebo, % | … | 3.78 | 15.85 |

| 95% CI (%)b | … | −67.23 to 44.63 | −49.27 to 52.56 |

| P value | … | … | 0.56 |

| Secondary endpoints | |||

| No. (%) participants with CDC-defined ILIa | 17 (1.73) | 15 (1.53) | 7 (0.71) |

| RRR vs placebo, % | … | 11.45 | 57.23 |

| 95% CI (%)b | … | −76.25 to 55.51 | −2.51 to 82.15 |

| No. (%) participants with WHO-defined ILIa | 11 (1.12) | 12 (1.22) | 6 (0.6) |

| RRR vs placebo, % | … | −9.80 | 44.13 |

| 95% CI (%)b | … | −147.41 to 51.27 | −50.49 to 79.26 |

Abbreviations: CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CI, confidence interval; ILI, influenza-like illness; RRR, relative risk reduction; RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction; WHO, World Health Organization.

aParticipants with multiple occurrences of protocol-, CDC-, or WHO-defined illness with RT-PCR–confirmed influenza A were counted once.

bThe 95% CI for the primary endpoint analysis of 450 mg versus placebo and for analyses of secondary endpoints are nominal and not adjusted for multiplicity.

To investigate the impact of preexisting infections or infections that may have been acquired before VIR-2482 achieving adequate tissue distribution, we conducted post hoc analyses excluding 10 cases of protocol-defined ILI, 5 cases of CDC-defined ILI, and 4 cases of WHO-defined ILI that occurred within 7 days following study drug administration. Numerically higher RRRs of ILI were observed in the VIR-2482 1200-mg group (protocol-defined: 34.0% [95% CI: −25.7 to 65.3]; CDC-defined: 64.9% [95% CI: 3.9–87.2]; WHO-defined: 42.9% [95% CI: −69.7 to 80.8]; Supplementary Table 1).

Most participants with protocol-defined ILI reported moderate to severe symptoms. Symptom severity of ILI measured by Flu-iiQ was similar across groups (Supplementary Table 2). Participants who received VIR-2482 1200 mg had a numerically shorter time to resolution of protocol-defined ILI than participants who received placebo (median: 85.8 hours [interquartile range, 57.7–137.2] vs 111.9 hours [interquartile range, 72.1–130.4]). No influenza-related hospitalizations or deaths were reported.

Safety

Treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) were reported in 62% to 65% of participants across study groups (Table 3). The most frequently reported TEAEs (>5% of participants in any group) were upper respiratory tract infection, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), oropharyngeal pain, cough, viral infection, and myalgia. Treatment-related TEAEs were reported in ≤2% of participants and were similarly distributed across groups. Serious TEAEs were uncommon (≤1% across groups), and none was considered related to study treatment. Five deaths occurred during the study, and none was considered related to treatment.

Table 3.

Occurrences of TEAEs Through the End of the Study (Safety Set)

| Placebo (n = 983) n (%) |

VIR-2482 450 mg (n = 981) n (%) |

VIR-2482 1200 mg (n = 992) n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Any TEAE | 639 (65.0) | 636 (64.8) | 613 (61.8) |

| TEAEs by maximum toxicity grade | |||

| Grade 1 | 441 (44.9) | 449 (45.8) | 406 (40.9) |

| Grade 2 | 181 (18.4) | 174 (17.7) | 190 (19.2) |

| Grade 3 | 14 (1.4) | 10 (1.0) | 12 (1.2) |

| Grade 4 | 3 (0.3) | 3 (0.3) | 5 (0.5) |

| Study treatment–related TEAEs | 15 (1.5) | 20 (2.0) | 17 (1.7) |

| TEAEs leading to study treatment discontinuation or interruption | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Serious TEAEs | 9 (0.9) | 10 (1.0) | 13 (1.3) |

| Study treatment–related serious TEAEs | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TEAEs leading to deatha | 0 | 2 (0.2) | 3 (0.3) |

| TEAEs occurring in >5% of participants in any treatment group | |||

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 248 (25.2) | 243 (24.8) | 245 (24.7) |

| COVID-19 | 106 (10.8) | 93 (9.5) | 92 (9.3) |

| Oropharyngeal pain | 75 (7.6) | 95 (9.7) | 87 (8.8) |

| Cough | 72 (7.3) | 88 (9.0) | 84 (8.5) |

| Viral infection | 70 (7.1) | 56 (5.7) | 48 (4.8) |

| Myalgia | 38 (3.9) | 51 (5.2) | 36 (3.6) |

A participant with multiple occurrences of the same TEAE was counted only once at the maximum toxicity grade or strongest relationship to study intervention.

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

aReasons for death were accidental drug overdose (nontreatment intervention) and suicide (both VIR-2482 450 mg), cardiac arrhythmia, cardiorespiratory arrest, and intentional multidrug overdose (nontreatment intervention; all VIR-2482 1200 mg). None of the deaths was considered related to study treatment.

Incidences of solicited injection site reactions at 1 hour postdose were <10% in all 3 groups (Supplementary Table 3). Grade 1 (mild) injection site pain was the most common self-reported injection site reaction (placebo, 5.6%; VIR-2482 450 mg, 6.1%; VIR-2482 1200 mg, 8.4%) during the onsite assessment. Mild injection site pain was also the most common injection site reaction reported on the electronic diary card during days 1 to 7 (placebo, 22.6%; VIR-2482 450 mg, 24.5%; VIR-2482 1200 mg, 23.9%; Supplementary Table 4). The most common participant-reported systemic reactions included mild myalgia (12.3%–14.9%), mild headache (12.5%–14.0%), and mild malaise (9.8%–10.3%; Supplementary Table 5). No treatment-emergent anaphylaxis events were reported. Incidences of treatment-emergent clinical laboratory and vital sign abnormalities were similar across groups.

Virologic Analyses

Among participants with protocol-defined ILI with RT-PCR–confirmed influenza A, H3 subtype virus was detected in 56% to 72% and H1 subtype in 16% to 36% of illnesses across study groups; 8% to 19.1% of illnesses had an unknown influenza A subtype (Supplementary Table 6).

Sequence and phenotypic data availability are described in Supplementary Table 7. Influenza A virus isolates, including the small number where a VIR-2482 epitope amino acid substitution was detected by sequence analysis, retained susceptibility to VIR-2482 with fold changes in half maximal effective concentration ranging from 0.23 to 2.55 compared with the respective subtype vaccine reference strain in vitro. Non–influenza A respiratory viral infections, most commonly severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, were detected in 8.5% to 10.5% of participants who received study intervention (Supplementary Table 8).

Pharmacokinetics

Following VIR-2482 1200 mg, median serum Tmax was 6.95 days, geometric mean serum Cmax was 111 µg/mL (CV% = 52.1%), and geometric mean serum concentration at EOIS was 18.5 µg/mL (CV% = 98.8). Median T1/2 was 54.7 to 55.4 days across VIR-2482 doses. Compared with gluteal administration, thigh injection resulted in 79.9% higher Cmax and 43.8% higher area under the curve for the 450-mg dose and 97.5% higher Cmax and 55.6% higher area under the curve for the 1200-mg dose (Supplementary Table 9).

Serum and NPS concentration-time data through 180 days postdose are displayed in Figure 2, and NPS:serum ratios are displayed in Supplementary Figure 2. The NPS concentrations of VIR-2482 averaged 2.1% to 7.8% of within-subject serum concentrations across doses and time points. VIR-2482 recipients who experienced breakthrough influenza A illness had serum levels that were comparable to those who did not (Supplementary Table 10).

Figure 2.

Pharmacokinetic profiles of VIR-2482 following intramuscular administration of (A) 450 mg and (B) 1200 mg doses.Abbreviation: NPS, nasopharyngeal swab.

Immunogenicity

The incidence of ADA was 5.4% (53/980) in the 450-mg group and 5.1% (51/992) in the 1200-mg group. A >4-fold increase in ADA titer relative to baseline was observed in 1 participant receiving VIR-2482 1200 mg, whereas the titer of all other preexisting ADAs was unaffected by treatment. Further, ADAs were not correlated with AEs, injection site reactions, or aberrant PK in any participant (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Neutralizing mAbs have demonstrated the ability to prevent symptomatic respiratory diseases, such as COVID-19 in adults [21] and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in infants [22]. Broadly neutralizing HA-stem binding antibodies are recognized as potential pandemic influenza countermeasures [13, 23], and studies of such antibodies have shown therapeutic efficacy in experimentally induced human influenza infections [24, 25] but have demonstrated inconsistent efficacy in treating uncomplicated seasonal influenza [26–28]. The current trial found that prophylactic intramuscular VIR-2482 administration was generally well tolerated but did not significantly protect against protocol-defined ILI with RT-PCR–confirmed influenza A compared with placebo. Several explanations could account for the lack of significant clinical efficacy observed in this study.

Two potential contributory factors were the early onset of influenza activity in the 2022 to 2023 influenza season [29] that coincided with study enrollment and dosing and the known lag between maximal serum and tissue concentrations following intramuscular dosing. When RT-PCR–confirmed illnesses that occurred <7 days after dosing were excluded, post hoc analyses showed greater reductions in ILI in VIR-2482 1200 mg recipients, including 65% RRR of the CDC-defined ILI cases in the 1200 mg group compared with placebo. These results suggest that early ILIs could have been due to either incubating infections before VIR-2482 dosing or infections acquired during the window before adequate tissue distribution. In addition, we noted that participants who received VIR-2482 1200 mg had a numerically shorter time to resolution of protocol-defined ILI than participants who received placebo, suggesting clinical activity at this dose.

The apparent dose-response observed in those who received VIR-2482 1200 mg versus 450 mg suggests the possibility that the onset and durability of protection was potentially limited by the drug levels achieved in relevant tissue compartments. The VIR-2482 1200-mg dose selection was based on modeling using in vitro EC90 data that estimated it would provide antiviral activity for >8 months [10]. Additional PK-pharmacodynamics analyses are needed to better understand the tissue distribution of VIR-2482 and the optimal drug levels needed in the respiratory tract.

The serum and nasopharyngeal exposures of VIR-2482 observed in this study were comparable to those reported in the phase 1 study of healthy volunteers [10]. Also, the overall incidence of ADAs was low and not correlated with reduced serum concentrations or incidence of infections. Consequently, dosing errors, manufacturing concerns, or aberrant PK are unlikely explanations for trial failure. Viral resistance was also unlikely to explain the lack of efficacy because viruses cultured from participants with influenza A infections retained susceptibility to VIR-2482 compared with respective subtype reference viruses in vitro.

One hypothesis that may account for these results is that the antiviral activities of HA-stem antibodies observed in vitro or in in vivo animal models do not translate into clinically meaningful benefit when administered to unvaccinated healthy adults for prophylaxis of symptomatic infection. The HA-stem antibodies that block fusion of the endocytosed virion within cells may not be as effective at preventing symptomatic infection compared with the head-binding HA antibodies typically induced by seasonal vaccines that block receptor binding.

An additional hypothesis is that VIR-2482 has clinically meaningful activity, but the selected endpoints, dose, study population, or timing did not enable a positive trial result. Unvaccinated healthy adults were selected as the trial population in this study to better understand the tolerability profile and clinical activity of VIR-2482 without prior vaccination. Notably, during the 2022 to 2023 influenza season, overall influenza vaccine effectiveness was 46.1% (95% CI: 20.4–63.6) by CDC estimates [30], similar to the potential efficacy observed with VIR-2482 1200 mg for the prespecified CDC-defined secondary endpoint. The CDC-defined endpoint, which requires a temperature >37.8°C, demonstrated numerically a 57.2% RRR in symptomatic RT-PCR–confirmed infection in VIR-2482 1200 mg recipients versus the 15.9% RRR observed for the primary endpoint. This raises the possibility that VIR-2482 could be more effective in preventing severe or systemic influenza illness in a more vulnerable patient population than unvaccinated healthy adults. Indeed, this concept has been demonstrated with mAbs targeting RSV in infants, where the primary endpoint is not mild symptomatic illness, but medically attended lower respiratory tract infection [22]. COVID-19 vaccines and mAbs have also demonstrated effectiveness against severe disease but are less effective in protecting against mild illness [31–33].

In conclusion, although VIR-2482 was well tolerated, it did not significantly prevent influenza A illness in healthy unimmunized adults at intramuscular doses up to 1200 mg. There remains a clinical need for long-duration prophylactic interventions that provide protection against the morbidity and mortality of influenza in individuals at high risk of complications. The findings from this trial provide valuable insights to support the future development of broad spectrum mAbs for the prevention of influenza illness.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Susanna K Tan, Vir Biotechnology, Inc., San Francisco, California, USA.

Deborah Cebrik, Vir Biotechnology, Inc., San Francisco, California, USA.

David Plotnik, Vir Biotechnology, Inc., San Francisco, California, USA.

Maria L Agostini, Vir Biotechnology, Inc., San Francisco, California, USA.

Keith Boundy, Vir Biotechnology, Inc., San Francisco, California, USA.

Christy M Hebner, Vir Biotechnology, Inc., San Francisco, California, USA.

Wendy W Yeh, Vir Biotechnology, Inc., San Francisco, California, USA.

Phillip S Pang, Vir Biotechnology, Inc., San Francisco, California, USA.

Jaynier Moya, Pines Care Research Center, Inc., Pembroke Pines, Florida, USA.

Charles Fogarty, Spartanburg Medical Research, Spartanburg, South Carolina, USA.

Manuchehr Darani, Marvel Clinical Research, Long Beach, California, USA.

Frederick G Hayden, Division of Infectious Diseases and International Health, University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, Virginia, USA.

Notes

Author contributions. S. K. T., D. C., D. P., M. L. A., K. B., C. M. H., W. W. Y., P. S. P., and F. G. H. conceptualized and designed the study. J. M., C. F., and M. D. acquired and analyzed data. D. C. conducted the statistical analyses. All authors interpreted data, drafted the manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to all the data in the study, take responsibility for the accuracy of the analysis, and had authority over manuscript preparation and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Acknowledgments. The authors thank all study participants, investigators, site personnel, and operational staff. The authors also thank Jeanne McKeon, PhD, of Lumanity Scientific Inc., for medical writing and editorial support, which was funded by Vir Biotechnology, Inc.

Financial support . This work was supported by Vir Biotechnology, Inc. and with federal funds from the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS); Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR); and Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) under contract number 75A50122C00081. The findings and conclusions herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the HHS or its components.

Data Sharing Statement. Relevant data can be found within the manuscript and Supplementary data.

References

- 1. World Health Organization . Influenza (seasonal) key facts. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal). Accessed 25 October 2023.

- 2. Wright P, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y. Orthomyxoviruses. In: Fields B, Knipe D, Howley P, eds. Fields Virology. 5 ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007:1691–740. [Google Scholar]

- 3. GBD 2017 Influenza Collaborators . Mortality, morbidity, and hospitalisations due to influenza lower respiratory tract infections, 2017: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Respir Med 2019; 7:69–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mertz D, Kim TH, Johnstone J, et al. . Populations at risk for severe or complicated influenza illness: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2013; 347:f5061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Collins JP, Campbell AP, Openo K, et al. . Outcomes of immunocompromised adults with laboratory-confirmed influenza in the United States, 2011–2015. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 70:2121–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Becker T, Elbahesh H, Reperant LA, Rimmelzwaan GF, Osterhaus ADME. Influenza vaccines: successes and continuing challenges. J Infect Dis 2021; 224:S405–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . CDC seasonal flu vaccine effectiveness studies. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/vaccines-work/effectiveness-studies.htm. Accessed 25 October 2023.

- 8. Wang WC, Sayedahmed EE, Sambhara S, Mittal SK. Progress towards the development of a universal influenza vaccine. Viruses 2022; 14:1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pizzuto M, Zatta F, Minola A, et al. . VIR-2482: a potent and broadly neutralizing antibody for the prophylaxis of influenza A illness [Poster #902873]. Presented at: IDWeek. Virtual, 2020.

- 10. Plotnik D, Sager JE, Aryal M, et al. . A phase 1 study in healthy volunteers to investigate the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of VIR-2482: a monoclonal antibody for the prevention of severe influenza A illness. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2024; 68:e0127323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ng S, Nachbagauer R, Balmaseda A, et al. . Novel correlates of protection against pandemic H1N1 influenza A virus infection. Nat Med 2019; 25:962–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. De Jong NMC, Aartse A, Van Gils MJ, Eggink D. Development of broadly reactive influenza vaccines by targeting the conserved regions of the hemagglutinin stem and head domains. Expert Rev Vaccines 2020; 19:563–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paules CI, Lakdawala S, McAuliffe JM, et al. . The hemagglutinin A stem antibody MEDI8852 prevents and controls disease and limits transmission of pandemic influenza viruses. J Infect Dis 2017; 216:356–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kallewaard NL, Corti D, Collins PJ, et al. . Structure and function analysis of an antibody recognizing all influenza A subtypes. Cell 2016; 166:596–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gillespie R, Cooper K, Guerra Canedo V, et al. . Pre-exposure antibody prophylaxis protects non-human primates from severe influenza disease [Poster #725]. Presented at: Ninth European Scientific Working Group on Influenza (ESWI) Influenza Conference. Valencia, Spain: ESWI, 2023.

- 16. US Food and Drug Administration . Toxicity Grading Scale for Healthy Adult and Adolescent Volunteers Enrolled in Preventive Vaccine Clinical Trials. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/73679/download. Accessed 16 September 2022.

- 17. Osborne RH, Norquist JM, Elsworth GR, et al. . Development and validation of the Influenza Intensity and Impact Questionnaire (FluiiQ™). Value Health 2011; 14:687–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van Baalen CA, Jeeninga RE, Penders GH, et al. . ViroSpot microneutralization assay for antigenic characterization of human influenza viruses. Vaccine 2017; 35:46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jayasundara K, Soobiah C, Thommes E, Tricco AC, Chit A. Natural attack rate of influenza in unvaccinated children and adults: a meta-regression analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2014; 14:670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Osterholm MT, Kelley NS, Sommer A, Belongia EA. Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2012; 12:36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Levin MJ, Ustianowski A, De Wit S, et al. . Intramuscular AZD7442 (tixagevimab–cilgavimab) for prevention of Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2022; 386:2188–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hammitt LL, Dagan R, Yuan Y, et al. . Nirsevimab for prevention of RSV in healthy late-preterm and term infants. N Engl J Med 2022; 386:837–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gostic KM, Ambrose M, Worobey M, Lloyd-Smith JO. Potent protection against H5N1 and H7N9 influenza via childhood hemagglutinin imprinting. Science 2016; 354:722–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McBride JM, Lim JJ, Burgess T, et al. . Phase 2 randomized trial of the safety and efficacy of MHAA4549A, a broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibody, in a human influenza A virus challenge model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 61:e01154–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sloan SE, Szretter KJ, Sundaresh B, et al. . Clinical and virological responses to a broad-spectrum human monoclonal antibody in an influenza virus challenge study. Antiviral Res 2020; 184:104763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lim JJ, Dar S, Venter D, et al. . A phase 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the monoclonal antibody MHAA4549A in patients with acute uncomplicated influenza A infection. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022; 9:ofab630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ali SO, Takas T, Nyborg A, et al. . Evaluation of MEDI8852, an anti-influenza A monoclonal antibody, in treating acute uncomplicated influenza. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018; 62:e00694–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hershberger E, Sloan S, Narayan K, et al. . Safety and efficacy of monoclonal antibody VIS410 in adults with uncomplicated influenza A infection: results from a randomized, double-blind, phase-2, placebo-controlled study. EBioMedicine 2019; 40:574–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Influenza activity in the United States during the 2022–23 season and composition of the 2023–24 influenza vaccine. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/spotlights/2023-2024/22-23-summary-technical-report.htm. Accessed 26 October 2023.

- 30. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Estimated influenza illnesses, medical visits, hospitalizations, and deaths prevented by vaccination in the United States – 2022-2023 influenza season. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden-prevented/2022-2023.htm. Accessed 20 May 2024.

- 31. Bar-On YM, Goldberg Y, Mandel M, et al. . Protection against Covid-19 by BNT162b2 booster across age groups. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:2421–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Altarawneh HN, Chemaitelly H, Ayoub HH, et al. . Effects of previous infection and vaccination on symptomatic omicron infections. N Engl J Med 2022; 387:21–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tseng HF, Ackerson BK, Luo Y, et al. . Effectiveness of mRNA-1273 against SARS-CoV-2 omicron and delta variants. Nat Med 2022; 28:1063–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.