Abstract

Humulus lupulus, or hops, is a vital ingredient in brewing, contributing bitterness, flavor, and aroma. The female plants produce strobiles rich in essential oils and acids, along with bioactive compounds like polyphenols, humulene, and myrcene, which offer health benefits. This study examined the aromatic profiles of five hop varieties grown in Brazil versus their countries of origin. Fifty grams of pelletized hops from each strain were collected and analyzed using HS-SPME/GC-MS to identify volatile compounds, followed by statistical analysis with PLS-DA and ANOVA. The study identified 330 volatile compounds and found significant aromatic differences among hops from different regions. For instance, H. Mittelfrüher grown in Brazil has a fruity and herbaceous profile, while the German-grown variety is more herbal and spicy. Similar variations were noted in the Magnum, Nugget, Saaz, and Sorachi Ace varieties. The findings underscore the impact of terroir on hop aromatic profiles, with Brazilian-grown hops displaying distinct profiles compared to their counterparts from their countries of origin, including variations in aromatic notes and α-acid content.

Keywords: Humulus lupulus, aromatic profile, terroir impact, volatile compounds, HS-SPME/GC-MS

1. Introduction

Humulus lupulus, commonly known as hops, is a species of flowering plant in the Cannabaceae family. It is native to Europe, Asia, and North America and is primarily known for its use in brewing beer [1]. The plant is a vigorous, climbing vine with rough stems and serrated leaves arranged oppositely along the stem. Hops are dioecious, meaning there are separate male and female plants. The female plants produce cone-like structures called strobiles, which are used in brewing to impart bitterness, flavor, and aroma to beer. These cones contain lupulin glands, which contain the essential oils and acids responsible for the characteristic bitterness and aroma of hops [2].

Apart from the most common compounds found in hop cones belonging to bitter acids (α- and β-acids) [3], there are at least several other bioactive compounds (essential oils and polyphenols) that make hop cones a feedstock with a broad range of microbiological properties [2,3,4]. Among various properties, hop cones contain compounds, such as prenylated flavonoids, which have been shown to possess sedative properties [5]. Certain compounds found in hops, such as phytoestrogens, have been investigated for their potential in hormone regulation. These compounds may have implications for conditions such as menopausal symptoms [6].

Hops offer health benefits due to their antioxidants, like polyphenols, which may reduce oxidative stress and chronic disease risk [7]. Compounds such as humulene and myrcene in hops are believed to have relaxing effects [8,9]. In addition, hundreds of aroma compounds are found in hop essential oils [10], though these oils constitute only about 0.5% to 3.0% of the hops’ dry weight [3]. The complex composition of hop essential oil makes characterizing its aroma a challenging task.

Despite the importance of characterizing aroma-related compounds in hops, the extraction methodologies commonly employed are often not very effective. Extraction techniques include steam distillation (SD), simultaneous distillation extraction (SDE), direct solvent extraction (DSE), and solvent-assisted flavor evaporation (SAFE). While SD and SDE are conventional methods, they can decompose volatile compounds due to high temperatures [11]. DSE extracts both volatiles and non-volatiles but is often used in combination with SAFE for thorough isolation. Although DSE-SAFE is an effective method, its high equipment costs and complexity limit accessibility. Headspace solid-phase microextraction (HS-SPME) is preferred for its solvent-free extraction and minimal sample volume requirements [11].

Regarding volatile and aromatic compounds, Su and Yin [11] conducted a study aimed at analyzing five fresh samples of Cascade and Chinook hops from different locations in Virginia using headspace solid-phase microextraction gas chromatography mass spectrometry olfactometry (HS-SPME-GC-MS-O). They identified 33 aromatic compounds, including esters, monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, terpenoids, an aldehyde, and an alcohol. Furthermore, the authors demonstrated how the cultivation location can significantly influence the aroma profiles of Cascade and Chinook hops [11]. This study demonstrated the effect of location on the production of volatile compounds in these hop varieties. Additionally, in Brazil, there has been an expansion in hop production involving foreign varieties.

Based on these principles and considering that volatile compounds are extremely important for determining the hop profile, as well as their application in the food, cosmetics, or pharmaceutical industries, this study aimed to evaluate the aromatic profile of the hop varieties Hallertauer Mittelfrüher, Magnum, Nugget, Saaz, and Sorachi Ace. Except for Sorachi Ace, the study compared samples from their countries of origin with samples of the same varieties grown in Brazil using headspace solid-phase microextraction coupled with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (HS-SPME/GC-MS).

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Samples

For this study, 50 g samples of pelletized hops from five distinct strains were collected, with samples planted in their countries of origin, except for Sorachi Ace, which was compared with samples of the same strains planted in Brazil. Samples of Magnum and Hallertauer Mittelfrüher hops were obtained from Germany, Nugget and Sorachi Ace from the United States, and Saaz from the Czech Republic, all sourced from Barth Haas (Nuremberg, Germany). The Brazilian hops, Hallertauer Mittelfrüher, Nugget, and Saaz, were sourced from Dalcin (Taguaí, SP, Brazil), and the Magnum and Sorachi Ace hops from Brava Terra (Fortuna, SP, Brazil) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the five hop (Humulus lupulus) varieties used in the present study.

| Hop Strain | Typical Use | Company | Origin | Harvest | Alpha Acid (%) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hallertauer Mittelfrüher | Aroma | Dalcin | Brazil | 2021 | 6.88 |

| Barth Haas | Germany | 2020 | 4.50 | ||

| Magnum | Bitter | Brava Terra | Brazil | 2021 | 12.81 |

| Barth Haas | Germany | 2020 | 14.70 | ||

| Nugget | Bitter | Dalcin | Brazil | 2021 | 9.66 |

| Barth Haas | United States | 2018 | 9.50 | ||

| Saaz | Aroma | Dalcin | Brazil | 2021 | 5.67 |

| Barth Haas | Czech Republic | 2020 | 3.50 | ||

| Sorcachi Ace | Aroma/Bitter | Brava Terra | Brazil | 2021 | 8.70 |

| Barth Haas | United States | 2020 | 10.80 |

* The measurement of alpha acids in hops was conducted using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). This method is regulated by organizations such as the American Society of Brewing Chemists (ASBC 1) and the European Brewery Convention (EBC 2). 1 ASBC methods of analysis—Hops-14 (HPLC method for alpha and beta acids in hops and hop products), American Society of Brewing Chemists, 2014. 2 Analytica-EBC, Method 7.4 (alpha acids in hops and hop products by HPLC), European Brewery Convention, 2010.

The samples were manually ground into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle for subsequent analysis. Ground hop samples (40 ± 0.5 mg) were placed in a 20 mL glass vial with an automatic sampler. The vials were sealed with PTFE/silicone septa and aluminum caps (Macherey-Nagel, Bethlehem, PA, USA).

2.2. Instrumentation

The volatile compound profiles were analyzed using headspace solid-phase microextraction (HS-SPME) combined with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS). This analysis employed the GCMSQP2020 NX system, incorporating the Nexis GC-2030 gas chromatograph, a quadrupole mass spectrometer, and the AOC-6000 Plus autosampler, all supplied by Shimadzu (Nakagyo-ku, Kyoto, Japan). For HS-SPME extraction, a DVB/CAR/PDMS (divinylbenzene–carboxen–polydimethylsiloxane) Smart Fiber (80 μm) from Shimadzu was utilized.

Prior to analysis, the fiber was preconditioned at 240 °C, and two blank injections were performed according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Samples were equilibrated for 10 min at 50 °C in the autosampler’s heat block. The extraction process involved exposing the SPME fiber to the sample headspace for 50 min. The fiber was then inserted into the GC injector port for 3 min at 230 °C in splitless mode (using an SPME glass liner with a 0.75 mm ID), enabling thermal desorption of the volatile compounds. GC separation was performed with a constant helium flow (1 mL/min) on a PEG capillary column (HP-INNOWAX, 30 m, 0.25 mm ID, 0.15 μm) from Shimadzu. The oven temperature was programmed to increase from 40 °C to 150 °C at a rate of 5 °C per minute, followed by a ramp to 225 °C at 20 °C per minute, with initial and final holding times of 5 min and 20 min, respectively, as described by Su and Yin [11].

Mass spectrometry detection was carried out using electron-impact (EI) ionization at 70 eV in full-scan mode within the 40–350 amu range. The transfer line and ion source were maintained at 250 °C. Data acquisition was conducted in total ion current (TIC) mode.

2.3. Volatile Compounds Identification and Database Software Analysis

The detection of volatile compounds was conducted by comparing each peak’s molecular fragmentation pattern against the mass spectra available in the 2020 NIST MS database library (National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). A compound was considered identified if it displayed a similarity index (SI) exceeding 85. In cases of ambiguous identifications, retention indices were calculated using a series of n-alkanes (C8–C23) as references for confirmation.

Chromatographic profiles from the samples were analyzed using chemometric classification methods. These methods aim to leverage experimental data to predict the qualitative properties of the samples, referred to as categories or classes. Specifically, the goal was to determine the aroma characteristics of the hop samples. Given the multivariate nature of the experimental data (i.e., the chromatographic profiles), this study focused on employing partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) to construct a classification model.

Each identified compound was queried using its CAS Registry Number in the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) (accessed on 1 August 2024). Furthermore, the flavor and aroma profiles of these compounds were examined using the Perflavory database (https://perflavory.com/search.php) (accessed on 1 August 2024).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

For statistical analysis, the results were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). To quantify the volatile compounds common in at least two of the analyzed styles, the identified peak areas were automatically converted into Area% using LabSolutions GCMSolutions software version 1 (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). This quantification approach was adopted because, as per the manufacturer, employing a specific standard for quantification ensures consistent concentration levels across all samples. Student’s t-test was utilized for comparing two samples, given that normal distribution was confirmed. For comparing three or more samples, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed, followed by the Tukey test. Differences were considered statistically significant when p ≤ 0.05 (5% significance level).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Classification by PLS-DA

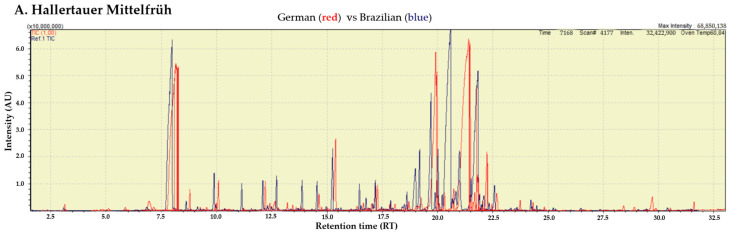

To investigate data trends and sample correlations, a multivariate analysis was utilized. A classification model was specifically created to highlight the differences related to the production method. Chromatographic profiles, illustrated as GC-MS total ion currents (TIC), were processed using PLS-DA to distinguish between the hop varieties planted in Brazil and those in their countries of origin (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Chemical interpretation of the PLS-DA model discriminating between hops planted in their countries of origin (red) and the same varieties planted in Brazil (blue). Samples are based on VIP scores and regression coefficients. The selected hop varieties were (A) Hallertauer Mittelfrüh, (B) Magnum, (C) Nugget, (D) Saaz, and (E) Sorachi Ace. The chromatogram regions significantly contribute to the PLS-DA model.

To evaluate chemical differences between the beer groups analyzed, variable importance in projection (VIP) scores were calculated from the PLS-DA model. VIP scores measure the contribution of individual variables to the model, with higher scores indicating greater importance. Normalized VIP scores greater than one are generally considered significant. By combining PLS regression coefficients with VIP scores, we can identify key compounds for distinguishing among sample types and gain insights into the direction of observed variations.

3.2. Aromatic Hop Profile

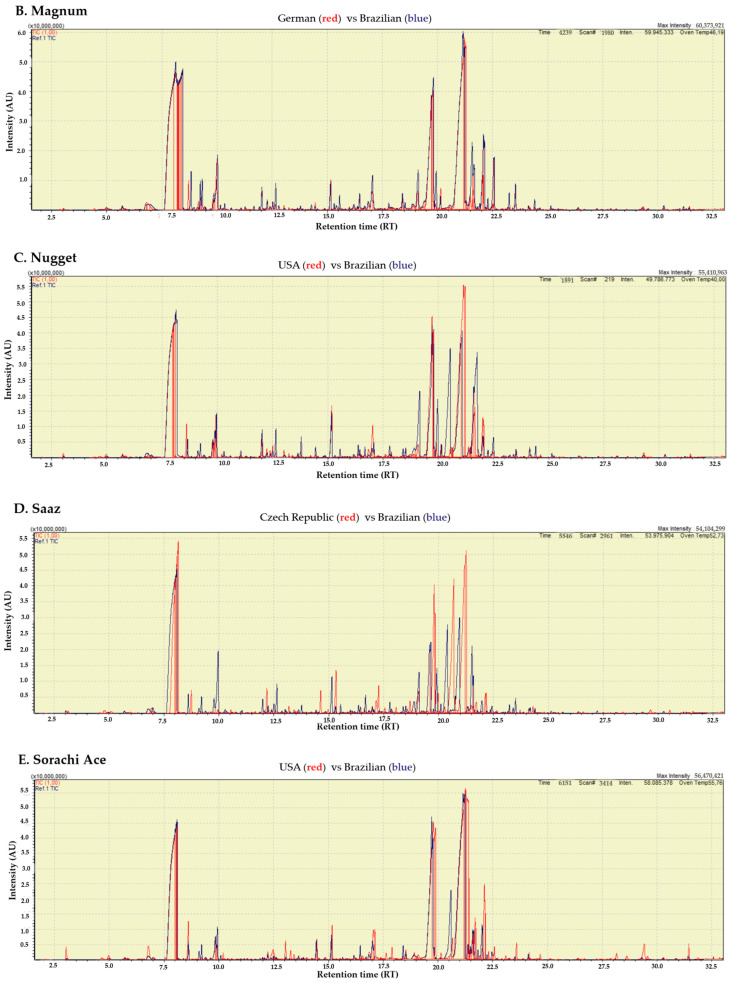

A total of 330 different volatile compounds were identified using HS-SPME/GC-MS across all hop samples (Table S1). Although several of these compounds exhibit distinct aroma and odor profiles, the suppliers of these hops, as well as Beer Maverick (https://beermaverick.com/) (accessed on 1 August 2024), have already reported differentiated profiles (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Aromatic profiles according to the hop (Humulus lupulus) strain producers for the varieties used in this study grown in their countries of origin (DE: Germany; USA: United States; and CZ: Czech Republic) and grown in Brazil (BR).

H. Mittelfrüher grown in Germany has a more spicy and herbal profile compared to the one grown in Brazil, which has a greener profile (Figure 2). Magnum grown in Germany has a spicier profile, whereas the one grown in Brazil features floral, berry, tropical fruit, citrus, and herbal notes. Nugget grown in the United States has a more herbal and woody profile, while the same variety grown in Brazil presents citrus, floral, and berry characteristics. Saaz grown in the Czech Republic has a slightly more woody and floral profile, while the same variety in Brazil exhibits more herbal, spicy, and citrus notes. Finally, Sorachi Ace grown in the United States shows almost the same pattern as the same variety in Brazil, except that the Brazilian variety is slightly more woody, tropical, citrus, herbal, and floral but maintains a very similar sensory pattern. It is interesting to note that the same variety planted in its country of origin, in this case, Japan, and according to Beer Maverick (https://beermaverick.com/), also has the same profile, except for the absence of a woody profile. This may indicate a variety with little terroir effect.

A study analyzed 33 active aromatic compounds in hop samples from the Cascade and Chinook varieties harvested from different locations in Virginia. Using chromatography and olfactometry techniques, the presence of esters, monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, and terpenoids, among other compounds, was identified, exhibiting various aromatic characteristics, such as fruity, herbal, woody, and citrus notes [11].

3.3. Hallertauer Mittelfrüher

H. Mittelfrüher (HM) is a hop variety that has shown a higher α-acid content when planted in Brazil, according to its suppliers (Table 1). When grown in Taguaí, São Paulo, it presents a content of 6.88%, compared to 4.50% in Germany. A more recent study with the same hop variety from the western region of Paraná, Brazil, indicated α-acid levels of 5.9%, β-acid levels of 1.80%, and an essential oil content of 1.1 mL/100 g [12].

In terms of compound quantities, calculated by % area, 14 compounds were more expressed in the German HM, while 23 were more expressed in the Brazilian HM (Table 2). Among the 14 compounds more expressed in the German variety, 11 are related to aroma or odor. In the Brazilian HM, 13 of the 23 more-expressed compounds are associated with aroma or odor. Regarding unique compounds, 64 were identified in the German HM compared to Brazilian HM, with 28 of these related to aroma (Table 3). In the Brazilian HM, 45 unique compounds were found compared to the German HM, with 22 being related to aroma.

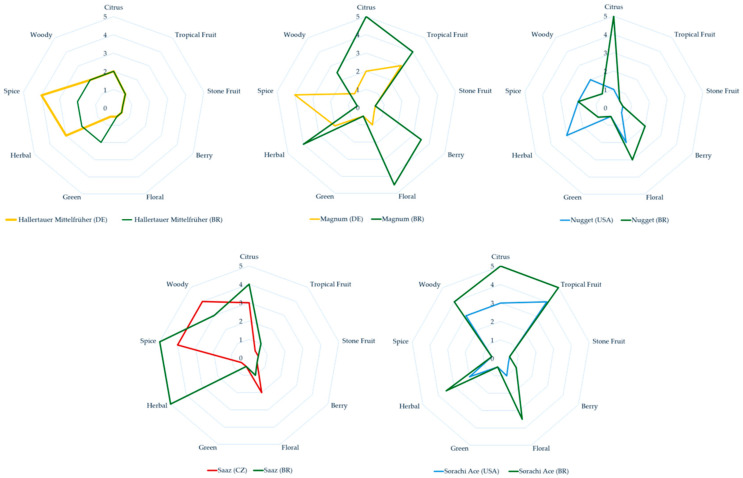

Table 2.

Compounds that showed their variation in expression (p ≤ 0.05) comparing the hop (Humulus lupulus) varieties planted in their country of origin with those planted in Brazil, in the hop variety of Hallertauer Mittelfruher, Magnum, Nugget, Saaz, and Sorachi Ace, planted in Germany (DE), United States (USA), Czech Republic (CZ), and Brazil (BR). Orange indicates higher expression, and blue is lower.

| Compound | CAS # | Retention Index | Odor | Flavor | H. Mittelfrüher | Magnum | Nugget | Saaz | Sorachi Ace | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Strength | Type | DE | BR | DE | BR | USA | BR | CZ | BR | USA | BR | |||

| alpha-Pinene | 80-56-8 | 948 | Herbal | High | Woody | ||||||||||

| 2-Methyl-1-butanol | 137-32-6 | 697 | Ethereal | Medium | Ethereal | ||||||||||

| 2-Methyl-1-Butanol | 1565-80-6 | 697 | |||||||||||||

| beta-Pinene | 127-91-3 | 943 | Herbal | High | Pine | ||||||||||

| Myrcene | 123-35-3 | 958 | Spicy | High | Woody | ||||||||||

| alpha-Phellandrene | 99-83-2 | 969 | Terpenic | Medium | Terpenic | ||||||||||

| alpha-Terpinene | 99-86-5 | 998 | Woody | Medium | Terpenic | ||||||||||

| dextro-Limonene | 5989-27-5 | 1018 | Citrus | Medium | Citrus | ||||||||||

| alpha-Terpineol | 555-10-2 | 964 | Minty | Medium | |||||||||||

| Pentan-2-yl propanoate | 54004-43-2 | 920 | |||||||||||||

| Methyl (E)-4-methylpent-2-enoate | 50652-78-3 | 828 | |||||||||||||

| 2-Pentene, 1-ethoxy-4-methyl-, (Z)- | 51149-75-8 | 836 | |||||||||||||

| 2-Methylpropyl 3-methylbutanoate | 589-59-3 | 955 | Fruity | Medium | Green | ||||||||||

| Isoamyl isobutyrate | 2050-1-3 | 955 | |||||||||||||

| 2-Methylbutyl 2-methylpropanoate | 2445-69-4 | 955 | Fruity | ||||||||||||

| Ortho-cymene | 527-84-4 | 1042 | |||||||||||||

| 1-Methyl-4-propan-2-ylidenecyclohexene | 586-62-9 | 1052 | Herbal | Medium | Woody | ||||||||||

| Methyl heptanoate | 106-73-0 | 984 | Fruity | Fruity | |||||||||||

| 2-Octanone | 111-13-7 | 952 | Earthy | Medium | Dairy | ||||||||||

| 3-Methylbut-2-enyl 2-methylpropanoate | 76649-23-5 | 1004 | Fruity | ||||||||||||

| Methyl Methylenecyclohexanoate | 73805-48-8 | 951 | |||||||||||||

| 1-Octen-3-ol | 3391-86-4 | 969 | Earthy | High | Mushroom | ||||||||||

| 3-Methylbutyl 2-methylbutanoate | 27625-35-0 | 1054 | Fruity | Fruity | |||||||||||

| 2-Methylbutyl 2-methylbutyrate | 2445-78-5 | 1054 | Fruity | Fruity | |||||||||||

| Isoamyl isovalerate | 2445-77-4 | 1054 | Fruity | Fruity | |||||||||||

| Methyl 6-methylheptanoate | 2519-37-1 | 1019 | |||||||||||||

| Perillene | 539-52-6 | 1125 | Woody | Medium | |||||||||||

| Hexahydro-1,1-dimethyl-4-methylene-4H-cyclopenta[c]furan | 344294-72-0 | 1052 | |||||||||||||

| Hexyl 2-methylpropanoate | 2349-7-7 | 1054 | |||||||||||||

| Methyl octanoate | 111-11-5 | 1083 | Waxy | Green | |||||||||||

| 2-Methylpropyl hexanoate | 105-79-3 | 1118 | Fruity | Medium | Fruity | ||||||||||

| Benzaldehyde | 100-52-7 | 982 | Fruity | High | Fruity | ||||||||||

| 2-Nonanone | 821-55-6 | 1052 | Fruity | Medium | Cheesy | ||||||||||

| 4-Hydroxy-3-hexanone | 4984-85-4 | 916 | |||||||||||||

| Octanol | 111-87-5 | 1059 | Waxy | Medium | Waxy | ||||||||||

| Linalool | 78-70-6 | 1082 | Floral | Medium | Citrus | ||||||||||

| Methyl 6-methyloctanoate | 5129-62-4 | 1118 | |||||||||||||

| Heptyl propanoate | 2216-81-1 | 1183 | Floral | Fruity | |||||||||||

| Heptyl isobutyrate | 2349-13-5 | 1218 | Fruity | Berry | |||||||||||

| Methyl nonanoate | 1731-84-6 | 1183 | Fruity | Winey | |||||||||||

| Hexanoic acid | 142-62-1 | 974 | Fatty | Medium | Cheesy | ||||||||||

| 2-Methylbutyl hexanoate | 2601-13-0 | 1218 | Ethereal | ||||||||||||

| alpha-Ylangene | 14912-44-8 | 1221 | |||||||||||||

| alpha-Copaene | 3856-25-5 | 1221 | Woody | ||||||||||||

| 2-Decanone | 693-54-9 | 1151 | Floral | Medium | Fermented | ||||||||||

| Decyl trifluoroacetate | 333-88-0 | 1216 | |||||||||||||

| 7-Decen-2-one | 35194-33-3 | 1159 | |||||||||||||

| Methylidenenonene | 55050-40-3 | 1156 | Aldehydic | Medium | |||||||||||

| 5-methylhexanoic acid | 628-46-6 | 1009 | Fatty | Medium | |||||||||||

| 2-(2,4-difluorophenyl)-1-[4-[6-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)pyridazin-3-yl]piperazin-1-yl]ethanone | 1191-2-2 | 868 | |||||||||||||

| beta-Copaene | 18252-44-3 | 1216 | |||||||||||||

| 2-Undecanone | 112-12-9 | 1251 | Fruity | Medium | Waxy | ||||||||||

| beta-Caryophyllene | 87-44-5 | 1494 | Spicy | Medium | Spicy | ||||||||||

| (Z)-Undec-6-en-2-one | 107853-70-3 | 1259 | |||||||||||||

| Trans-geranic acid methyl ester | 1189-9-9 | 1054 | |||||||||||||

| (E)-beta-farnesene | 18794-84-8 | 1440 | Woody | ||||||||||||

| alpha-Humulene | 6753-98-6 | 1579 | Woody | ||||||||||||

| (Z,E)-alpha-Farnesene | 26560-14-5 | 1458 | |||||||||||||

| (-)-alpha-Muurolene | 10208-80-7 | 1440 | Woody | ||||||||||||

| alpha-Selinene | 473-13-2 | 1474 | Amber | ||||||||||||

| (3R,4aS,8aR)-8a-methyl-5-methylidene-3-prop-1-en-2-yl-1,2,3,4,4a,6,7,8-octahydronaphthalene | 17066-67-0 | 1469 | Herbal | ||||||||||||

| alpha-Farnesene | 502-61-4 | 1458 | Woody | Green | |||||||||||

| (-)-alpha-Gurjunene | 489-40-7 | 1419 | Woody | ||||||||||||

| (-)-gamma-Cadinene | 39029-41-9 | 1435 | Woody | Medium | |||||||||||

| (+)-delta-Cadinene | 483-76-1 | 1469 | Herbal | ||||||||||||

| Zonarene | 41929-5-9 | 1440 | |||||||||||||

| Naphthalene, 1,2,3,4,4a,7-hexahydro-1,6-dimethyl-4-(1-methylethyl)- | 16728-99-7 | 1440 | |||||||||||||

| alpha-Cedrene | 24406-5-1 | 1440 | |||||||||||||

| Perilla alcohol | 18457-55-1 | 1261 | |||||||||||||

| 2-Tridecanone | 593-8-8 | 1164 | |||||||||||||

| Geranyl Propionate | 105-90-8 | 1451 | Floral | Medium | Waxy | ||||||||||

| Calamenene | 483-77-2 | 1537 | Herbal Spicy | Medium | |||||||||||

| Geranyl Butyrate | 106-29-6 | 1550 | Fruity | Medium | Fruity | ||||||||||

| (Z,Z)-1,8,11-heptadecatriene | 56134-3-3 | 1164 | |||||||||||||

| (Z)-3-decen-1-yl acetate | 81634-99-3 | 1389 | |||||||||||||

| Methyl ester 3,6-dodecadienoic acid | 16106-1-7 | 1164 | |||||||||||||

| Linalool oxide | 5989-33-3 | 1164 | Earthy | Medium | |||||||||||

| beta-Calacorene | 50277-34-4 | 1542 | |||||||||||||

| Heneicosapentaenoic acid methyl ester | 65919-53-1 | 2415 | |||||||||||||

| Linolenyl Alcohol | 506-44-5 | 2077 | |||||||||||||

| 2-n-Butyl-2-cyclopentenone | 5561_5-7 | 1280 | |||||||||||||

| 1-Epi-cubenol | 19912-67-5 | 1580 | |||||||||||||

| beta-Caryophyllene oxide | 1139-30-6 | 1507 | Woody | Medium | Woody | ||||||||||

| Isoascaridole | 19888-33-6 | 1592 | Herbal | ||||||||||||

| Neointermedeol | 5945-72-2 | 1613 | |||||||||||||

| Humulene oxide II | 19888-34-7 | 1592 | |||||||||||||

| Methyl (8Z,11Z,14Z,17Z)-icosa-8,11,14,17-tetraenoate | 132712-70-0 | 2308 | |||||||||||||

| Cadalene | 483-78-3 | 1706 | |||||||||||||

| Caryophylla-4(12),8(13)-dien-5.alpha.-ol | 19431-79-9 | 1677 | |||||||||||||

| Methyl (Z)-5,11,14,17-eicosatetraenoate | 59149-1-8 | 1280 | |||||||||||||

Table 3.

Unique volatile for each hop (Humulus lupulus) variety compared between samples planted and their country of origin with planted in Brazil. The varieties included Hallertauer Mittelfruher, Magnum, Nugget, Saaz, and Sorachi Ace, planted in Germany (DE), United States (USA), Czech Republic (CZ), and Brazil (BR). The green color indicates the presence of a specific compound in the hop samples studied.

| Compound | CAS # | Retention Index | Odor | Flavor | H. Mittelfrüher | Magnum | Nugget | Saaz | Sorachi Ace | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Strength | Type | DE | BR | DE | BR | USA | BR | CZ | BR | USA | BR | |||

| 2-Methyl-1-butanol | 137-32-6 | 697 | Ethereal | Medium | Ethereal | ||||||||||

| Methyl isobutyrate | 547-63-7 | 621 | Fruity | Ethereal | |||||||||||

| Dimethyl disulfide | 624-92-0 | 722 | Sulfurous | Sulfurous | |||||||||||

| alpha-Phellandrene | 99-83-2 | 969 | Terpenic | Medium | Terpenic | ||||||||||

| Isovaleric acid | 503-74-2 | 811 | Cheesy | High | Cheesy | ||||||||||

| Heptyl isobutyrate | 2349-13-5 | 1218 | Fruity | Berry | |||||||||||

| Linalool oxide | 5989-33-3 | 1164 | Earthy | Medium | |||||||||||

| Acetone | 67-64-1 | 455 | Solvent | High | |||||||||||

| Geranyl isovalerate | 109-20-6 | 1586 | Fruity | Medium | Green | ||||||||||

| alpha-Myrcene | 3338-55-4 | 976 | Floral | Medium | Green | ||||||||||

| Hexyl acetate | 142-92-7 | 984 | Fruity | Medium | Fruity | ||||||||||

| Pentyl isobutyrate | 2445-72-9 | 1019 | Fruity | ||||||||||||

| 2-Nonanol | 628-99-9 | 1078 | Waxy | Waxy | |||||||||||

| (-)-gamma-Elemene | 29873-99-2 | 1431 | Green | Medium | |||||||||||

| (-)-gamma-Cadinene | 39029-41-9 | 1435 | Woody | Medium | |||||||||||

| beta-Cadinene | 523-47-7 | 1440 | Woody | Medium | |||||||||||

| Neryl butyrate | 999-40-6 | 1550 | Green | Green | |||||||||||

| Calamenene | 483-77-2 | 1537 | Herbal Spicy | Medium | |||||||||||

| Isoascaridole | 19888-33-6 | 1592 | Herbal | ||||||||||||

| Cedrol | 19435-97-3 | 1580 | Herbal | Medium | |||||||||||

| alpha-Muurolene | 17699-14-8 | 1344 | Herbal | ||||||||||||

| beta-Bisabolene | 28973-97-9 | 1440 | Green | ||||||||||||

| Methyl Isovalerate | 23747-45-7 | 940 | Cheesy | Fermented | |||||||||||

| 1-Hexanol | 111-27-3 | 860 | Herbal | Green | |||||||||||

| Beta-Myrcene | 502-99-8 | 958 | Fruity | Medium | |||||||||||

| Methyl Heptenone | 110-93-0 | 938 | Citrus | Medium | Green | ||||||||||

| Isoamyl Isovalerate | 2445-77-4 | 1054 | Fruity | Fruity | |||||||||||

| Methyl Nonenoate | 13481-87-3 | 1191 | Fruity | Medium | Fruity | ||||||||||

| Delta-3-Carene | 13474-59-4 | 1430 | Woody | ||||||||||||

| Viridiflorol | 20307-83-9 | 1446 | Herbal | Medium | |||||||||||

| Geranyl Propionate | 105-90-8 | 1451 | Floral | Medium | Waxy | ||||||||||

| Geranyl Butyrate | 106-29-6 | 1550 | Fruity | Medium | Fruity | ||||||||||

| Beta-Farnesene | 21391-99-1 | 1547 | Woody | Medium | |||||||||||

| Muscone | 37609-25-9 | 2072 | Musk | Medium | |||||||||||

| Alpha-Phellandrene | 3779-61-1 | 976 | Sweet Herbal | Medium | |||||||||||

| Octyl Isobutyrate | 109-15-9 | 1317 | Waxy | Medium | Creamy | ||||||||||

| Methyl 2-Methylbutanoate | 868-57-5 | 721 | Fruity | Fruity | |||||||||||

| Methyl Isovalerate | 556-24-1 | 721 | Fruity | Medium | Fruity | ||||||||||

| beta-Pinene | 127-91-3 | 943 | Herbal | High | Pine | ||||||||||

| Methyl Caproate | 106-70-7 | 884 | Fruity | Medium | Fruity | ||||||||||

| Ethyl Propanoate | 105-37-3 | 686 | Fruity | High | Fruity | ||||||||||

| 2-Methyl-1-Butanol | 1565-80-6 | 697 | |||||||||||||

| Isobutyl Isobutyrate | 97-85-8 | 856 | Fruity | Fruity | |||||||||||

| Ethyl Isohexanoate | 25415-67-2 | 920 | Fruity | ||||||||||||

| alpha-Terpineol | 555-10-2 | 964 | Minty | Medium | |||||||||||

| Dodecane | 112-40-3 | 1200 | Alkane | ||||||||||||

| Methyl Octanoate | 15870-7-2 | 884 | |||||||||||||

| Methyl 2-Methylheptanoate | 51209-78-0 | 1019 | |||||||||||||

| 6-Methyl-5-Hepten-2-one | 49852-35-9 | 896 | |||||||||||||

| 2-Octanone | 111-13-7 | 952 | Earthy | Medium | Dairy | ||||||||||

| Methyl Methylenecyclohexanoate | 73805-48-8 | 951 | |||||||||||||

| Beta-Pinene | 514-95-4 | 992 | |||||||||||||

| Methyl 7-Methyloctanoate | 2177-86-8 | 1118 | |||||||||||||

| Octyl Acetate | 112-14-1 | 1183 | Floral | Medium | Waxy | ||||||||||

| Pentyl Cyclohexadiene | 56318-84-4 | 1143 | |||||||||||||

| Hexanoic Acid | 142-62-1 | 974 | Fatty | Medium | Cheesy | ||||||||||

| 7-Decen-2-one | 35194-33-3 | 1159 | |||||||||||||

| Methylidenenonene | 55050-40-3 | 1156 | Aldehydic | Medium | |||||||||||

| Octyl Propanoate | 142-60-9 | 1282 | Fruity | Estery | |||||||||||

| Pentadecene | 13360-61-7 | 1502 | |||||||||||||

| beta-Cedrene | 30021-74-0 | 1435 | Woody | ||||||||||||

| alpha-Cedrene | 24406-5-1 | 992 | |||||||||||||

| Geranyl Isovalerate | 51117-19-2 | 1586 | |||||||||||||

| Linolenyl alcohol | 506-44-5 | 2077 | |||||||||||||

| Methyl 4-Methylpentanoate | 2412-80-8 | 820 | Fruity | Fruity | |||||||||||

| Carene | 3387-41-5 | 897 | Woody | Woody | |||||||||||

| Ethyl Hexanoate | 123-66-0 | 984 | Fruity | High | Fruity | ||||||||||

| Pentyl Propanoate | 624-54-4 | 984 | Fruity | Fruity | |||||||||||

| 4-Pentenyl Butyrate | 30563-31-6 | 1073 | |||||||||||||

| 5-Methylheptan-2-ol | 54630-50-1 | 915 | |||||||||||||

| Ethyl 5-Methylhexanoate | 10236-10-9 | 1019 | |||||||||||||

| Methyl (E)-Hept-2-enoate | 22104-69-4 | 992 | |||||||||||||

| (Z)-Hex-2-enyl Acetate | 56922-75-9 | 992 | |||||||||||||

| Ethyl Octanoate | 106-32-1 | 1183 | Waxy | Medium | Waxy | ||||||||||

| beta-Bisabolene | 495-61-4 | 1500 | Balsamic | ||||||||||||

| 1-Methyloctyl acetate | 14936-66-4 | 1218 | |||||||||||||

| 2,3,5-Trithiahexane | 42474-44-2 | 1072 | Sulfurous | ||||||||||||

| Alloisolongifolene | 87064-18-4 | 1390 | |||||||||||||

| 1-Tetradecene | 1120-36-1 | 1403 | |||||||||||||

| Ethyl trans-4-decenoate | 76649-16-6 | 1389 | Green | Medium | Fatty | ||||||||||

| Neryl isobutyrate | 2345-24-6 | 1486 | Fruity | Medium | Fruity | ||||||||||

| Methyl petroselinate | 2777-58-4 | 2085 | |||||||||||||

| Germacrene B | 15423-57-1 | 1603 | Woody | ||||||||||||

| 1-Tridecene | 2437-56-1 | 1304 | |||||||||||||

| Agarospirol | 1460-73-7 | 1598 | |||||||||||||

| Muurola-4,10(14)-dien-1 beta-ol | 257293-90-6 | 1586 | |||||||||||||

| Ethyl octanoate | 106-32-1 | 1183 | Waxy | Medium | Waxy | ||||||||||

| Trans-propionate 2-methyl-cyclohexanol | 15287-79-3 | 1208 | |||||||||||||

| 2-Methylcyclohexyl butyrate | 15287-80-6 | 1307 | |||||||||||||

| 3-Methylpentanoic acid | 105-43-1 | 910 | Animal | Medium | Sour | ||||||||||

| cis-3-Hexenyl butyrate | 16491-36-4 | 1191 | Green | Medium | Green | ||||||||||

| (2S,4S)-2,4-Dimethylhexanoic acid methyl ester | 14251-45-7 | 955 | |||||||||||||

| Ethyl heptanoate | 106-30-9 | 1083 | Fruity | Medium | Fruity | ||||||||||

| Hexyl propanoate | 2445-76-3 | 1083 | Fruity | ||||||||||||

| Neo-alloocimene | 7216-56-0 | 993 | |||||||||||||

| Methyl non-4-enoate | 20731-19-5 | 1191 | |||||||||||||

| 2-Methyl-6-methyleneocta-2,7-dien-4-ol | 14434-41-4 | 1200 | |||||||||||||

| Eremophilene | 10219-75-7 | 1474 | |||||||||||||

| Geranyl acetate | 105-87-3 | 1352 | Floral | Medium | Green | ||||||||||

| Gamma-maalinene | 20071-49-2 | 1398 | |||||||||||||

| (-)-Aristolene | 6831-16-9 | 1403 | |||||||||||||

| 2-Tetradecanone | 2345-27-9 | 1549 | |||||||||||||

| trans-Nerolidol | 40716-66-3 | 1564 | Floral | Low | Green | ||||||||||

| 1-cyclododecyl-ethanone | 28925-0-0 | 955 | |||||||||||||

| Linolenyl alcohol | 506-44-5 | 2077 | |||||||||||||

| alpha-Cadinol | 481-34-5 | 1580 | Herbal | Medium | |||||||||||

| 2,2,4,6,6-pentamethylheptane | 13475-82-6 | 981 | |||||||||||||

| Butyl nitrite | 544-16-1 | 609 | |||||||||||||

| 1-Pentanol | 71-41-0 | 761 | Fermented | Fusel | |||||||||||

| 2-methylbutyl propanoate | 2438-20-2 | 920 | Fruity | ||||||||||||

| Benzaldehyde | 100-52-7 | 982 | Fruity | High | Fruity | ||||||||||

| 6-methylheptanoic acid | 929-10-2 | 1109 | |||||||||||||

| 5-Nonenoic acid methyl ester | 20731-20-8 | 1191 | |||||||||||||

| Heptanoic acid | 111-14-8 | 1073 | Cheesy | Waxy | |||||||||||

| Neryl isobutyrate | 2345-24-6 | 1486 | Fruity | Medium | Fruity | ||||||||||

| Perillyl alcohol | 536-59-4 | 1261 | Green | Medium | Woody | ||||||||||

| Isopentyl 8-methylnon-6-enoate | 1215128-16-7 | 1559 | |||||||||||||

| 4,8,11,11-tetramethylbicyclo[7.2.0]undec-3-en-5-ol | 913176-41-7 | 1677 | |||||||||||||

| (6Z,9Z,12Z,15Z)-Methyl octadeca-6,9,12,15-tetraenoate | 73097-0-4 | 943 | |||||||||||||

| Bicyclo[3.1.1]hept-2-ene, 2,6-dimethyl-6-(4-methyl-3-pentenyl)- | 17699-5-7 | 1474 | |||||||||||||

| Methyl 5-methyl-2-hexenoate | 68797-67-1 | 928 | |||||||||||||

| 4,6-Dimethyloctanoic acid | 2553-96-0 | 1154 | |||||||||||||

| 1,3-Nonadiene | 56700-77-7 | 914 | |||||||||||||

| Camphene | 79-92-5 | 943 | Woody | Medium | Camphoreous | ||||||||||

| alpha-Terpinene | 99-86-5 | 998 | Woody | Medium | Terpenic | ||||||||||

| Borneol | 464-45-9 | 1138 | Balsamic | Medium | Camphoreous | ||||||||||

| 10-Epizonarene | 41702-63-0 | 1469 | |||||||||||||

| alpha-Farnesene | 502-61-4 | 1458 | Woody | Green | |||||||||||

| (+)-delta-Cadinene | 483-76-1 | 1469 | Herbal | ||||||||||||

| Naphthalene, 1,2,3,4,4a,7-hexahydro-1,6-dimethyl-4-(1-methylethyl)- | 16728-99-7 | 1440 | |||||||||||||

| 1-Octadecene | 112-88-9 | 1801 | |||||||||||||

| (2Z,6E)-Farnesol | 3790-71-4 | 1710 | |||||||||||||

| 4-methyl-5-propylnonane | 62185-55-1 | 1185 | |||||||||||||

| 3-Methylbut-2-enyl 2-methylpropanoate | 76649-23-5 | 1004 | Fruity | ||||||||||||

| 2,6-dimethyl-1,3,5,7-octatetraene, E,E- | 460-1-5 | 955 | |||||||||||||

| Heptyl propanoate | 2216-81-1 | 1183 | Floral | Fruity | |||||||||||

| alpha-Guaiene | 3691_12-1 | 1054 | Woody | ||||||||||||

| Methyl linolelaidate | 2462-85-3 | 955 | |||||||||||||

| Methyl dodecanoate | 111-82-0 | 1481 | Waxy | Medium | Waxy | ||||||||||

| Methyl decanoate | 110-42-9 | 1282 | Fermented | Fatty | |||||||||||

| 2-methylpropyl propanoate | 540-42-1 | 955 | Fruity | Fruity | |||||||||||

| Pentan-2-yl propanoate | 54004-43-2 | 920 | |||||||||||||

| 3-methylbutyl 3-methylbutanoate | 659-70-1 | 1054 | Fruity | Medium | Green | ||||||||||

| S-propyl hexanethioate | 2432-78-2 | 1303 | |||||||||||||

| (Z)-Undec-6-en-2-one | 107853-70-3 | 1259 | |||||||||||||

| (-)-alpha-Gurjunene | 489-40-7 | 1419 | Woody | ||||||||||||

| .alpha.-Maaliene | 489-28-1 | 1403 | |||||||||||||

| Methyl petroselinate | 2777-58-4 | 2085 | |||||||||||||

| Perilla alcohol | 18457-55-1 | 1261 | |||||||||||||

| Heneicosapentaenoic acid methyl ester | 65919-53-1 | 2415 | |||||||||||||

| 2,2-dimethyldecane | 17302-37-3 | 1130 | |||||||||||||

| 3-methylbut-2-enal | 107-86-8 | 692 | Fruity | Fruity | |||||||||||

| 3,5-dimethyl-1,6-heptadiene | 68701-99-5 | 768 | |||||||||||||

| (Z)-9-methylundec-5-ene | 74630-65-2 | 1158 | |||||||||||||

| Methyl (E)-4-methylpent-2-enoate | 50652-78-3 | 828 | |||||||||||||

| (Z)-hex-3-en-1-ol | 928-96-1 | 868 | Green | High | Green | ||||||||||

| 2-methylbutanoic acid | 116-53-0 | 811 | Acidic | Medium | Fruity | ||||||||||

| Methyl 2,4-dimethylnonanoate | 54889-61-1 | 1253 | |||||||||||||

| 2-methyl-6-methylene-2-octene | 10054-9-8 | 1054 | |||||||||||||

| 3,3-dimethylcyclohexan-1-one | 2979-19-3 | 1025 | |||||||||||||

| Decyl trifluoroacetate | 333-88-0 | 1216 | |||||||||||||

| 2-Nonanone | 821-55-6 | 1052 | Fruity | Medium | Cheesy | ||||||||||

| Fenchol | 1632-73-1 | 1138 | Camphoreous | Medium | Camphoreous | ||||||||||

| 11,14-Eicosadienoic acid, methyl ester | 2463_02-7 | 1054 | |||||||||||||

| beta-Bisabolene | 495-61-4 | 1500 | Balsamic | ||||||||||||

| (E)-alpha-bisabolene | 25532-79-0 | 1518 | |||||||||||||

| 3-(1,1-dimethylethyl)-2,5-furandione | 18261-7-9 | 1054 | |||||||||||||

| 1-methyl-3-propan-2-ylbenzene | 535-77-3 | 1042 | |||||||||||||

| Methyl (Z)-octadec-9-enoate | 112-62-9 | 2085 | Mild fatty | Low | |||||||||||

| trans-Furan linalool oxide | 34995-77-2 | 1164 | Floral | Medium | |||||||||||

| 3-methoxybutan-2-ol | 53778-72-6 | 692 | |||||||||||||

| alpha-Pinene | 80-56-8 | 948 | Herbal | High | Woody | ||||||||||

| Butyl 2-methylpropanoate | 97-87-0 | 920 | Fruity | Fruity | |||||||||||

| 2-Methylpropyl 3-methylbutanoate | 589-59-3 | 955 | Fruity | Medium | Green | ||||||||||

| Isoamyl isobutyrate | 2050-1-3 | 955 | |||||||||||||

| (Z)-3-hexen-1-yl acetate | 3681-71-8 | 992 | Green | High | Green | ||||||||||

| Methyl (2S,4R)-2,4-dimethylheptanoate | 18450-78-7 | 1054 | |||||||||||||

| 2-methylpent-4-en-1-ol | 5673-98-3 | 786 | |||||||||||||

| [(Z)-hex-3-enyl] 2-methylbutanoate | 53398-85-9 | 1226 | Green | Medium | Green | ||||||||||

| Methyl 10-undecenoate | 111-81-9 | 1371 | Fatty | Waxy | |||||||||||

| alpha-Selinene | 473-13-2 | 1474 | Amber | ||||||||||||

| 2-Isopropenyl-4a,8-dimethyl-1,2,3,4,4a,5,6,7-octahydronaphthalene | 103827-22-1 | 1502 | |||||||||||||

| Geraniol | 106-24-1 | 1228 | Floral | Medium | Floral | ||||||||||

| Methyl ester 3,6-dodecadienoic acid | 16106-1-7 | 1164 | |||||||||||||

| 2-hexadecyloxirane | 7390-81-0 | 1054 | |||||||||||||

| Neryl propionate | 105-91-9 | 1451 | Fruity | Medium | Green | ||||||||||

| Aplotaxene | 10482-53-8 | 1725 | Costus | ||||||||||||

| 2-Nonadecanone | 629-66-3 | 2046 | |||||||||||||

| Methyl 7Z-hexadecenoate | 56875-67-3 | 1886 | |||||||||||||

| Methyl (8Z,11Z,14Z,17Z)-icosa-8,11,14,17-tetraenoate | 132712-70-0 | 2308 | |||||||||||||

| Prenol | 556-82-1 | 746 | Fruity | Fruity | |||||||||||

| Isobutyl 2-methylbutyrate | 2445-67-2 | 955 | Fruity | Fruity | |||||||||||

| Ortho-cymene | 527-84-4 | 1042 | |||||||||||||

| Methyl heptanoate | 106-73-0 | 984 | Fruity | Fruity | |||||||||||

| 2-Methylbutyl 2-methylbutyrate | 2445-78-5 | 1054 | Fruity | Fruity | |||||||||||

| Heptyl ester acetic acid | 112-6-1 | 1054 | |||||||||||||

| hexyl 2-methylpropanoate | 2349-7-7 | 1054 | |||||||||||||

| Methyl octanoate | 111-11-5 | 1083 | Waxy | Green | |||||||||||

| Mesityl oxide | 141-79-7 | 739 | Vegetable | Potato | |||||||||||

| 2-Heptanone | 110-43-0 | 853 | Cheesy | High | Cheesy | ||||||||||

| 3-Methylbutyl propanoate | 105-68-0 | 920 | Fruity | Medium | Fruity | ||||||||||

| 1-Dodecene | 112-41-4 | 1204 | |||||||||||||

| 1-Cyclohexyl-2-buten-1-ol | 79605-62-2 | 1249 | |||||||||||||

| 2-Methylpropyl hexanoate | 105-79-3 | 1118 | Fruity | Medium | Fruity | ||||||||||

| 1,1-Cyclohexanedimethanol | 2658-60-8 | 1339 | |||||||||||||

| 2-Methyl-2-(4-methyl-3-pentenyl)-cyclopropanemethanol | 98678-70-7 | 1280 | |||||||||||||

| 2-Methyl-2-pentenoic acid | 16957-70-3 | 1054 | Fruity | Medium | |||||||||||

| (1S,4S,4aS)-1-Isopropyl-4,7-dimethyl-1,2,3,4,4a,5-hexahydronaphthalene | 267665-20-3 | 1440 | |||||||||||||

| Calarene | 17334-55-3 | 1403 | |||||||||||||

| Cyclodecene | 3618-12-0 | 1181 | |||||||||||||

| Alpha-dehydro-ar-himachalene | 78204-62-3 | 1601 | |||||||||||||

| 2-ethylidene-1,7,7-trimethylbicyclo[2.2.1]heptane | 62413-60-9 | 1134 | |||||||||||||

| 2-n-Butyl-2-cyclopentenone | 5561_5-7 | 1054 | |||||||||||||

| beta-Caryophyllene oxide | 1139-30-6 | 1507 | Woody | Medium | Woody | ||||||||||

| (-)-Camphene | 5794_04-7 | 1280 | |||||||||||||

| 5-Methylhexan-3-one | 623-56-3 | 789 | |||||||||||||

| 2-Pentene, 1-ethoxy-4-methyl-, (Z)- | 51149-75-8 | 836 | |||||||||||||

| (E)-hex-4-en-1-ol | 928-92-7 | 868 | Green | Green | |||||||||||

| Di(imidazol-1-yl)methanone | 530-62-1 | 1445 | |||||||||||||

| Ethyl 3-hexenoate | 2396-83-0 | 992 | Fruity | Medium | Fruity | ||||||||||

| 2-methylbutyl butanoate | 51115-64-1 | 1019 | Fruity | Fruity | |||||||||||

| 1-Heptanol | 111-70-6 | 960 | Green | Medium | Solvent | ||||||||||

| Methyl nonanoate | 1731-84-6 | 1183 | Fruity | Winey | |||||||||||

| 2-Methylbutyl hexanoate | 2601-13-0 | 1218 | Ethereal | ||||||||||||

| 2-methyl-6-methylideneocta-1,7-dien-3-one | 41702-60-7 | 1076 | |||||||||||||

| 3,5-Dimethyl-1,6-heptadiene | 68701-99-5 | 768 | |||||||||||||

| Nalpha,Nomega-Dicarbobenzoxy-L-arginine | 53934-75-1 | 3543 | |||||||||||||

| 2-(2,4-difluorophenyl)-1-[4-[6-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)pyridazin-3-yl]piperazin-1-yl]ethanone | 1191-2-2 | 868 | |||||||||||||

The German HM exhibits an aromatic profile rich in herbal, spicy, floral, fruity, and woody notes, whereas those from Brazil have an aromatic profile characterized by fruity, herbal, sweet, and woody notes. This aromatic profile aligns with the descriptions provided by the suppliers for both (Figure 2).

Among the compounds that are more highly expressed, we can highlight dextro-limonene (citrus), also known as D-limonene (Table 2). This compound acts against the cytoplasmic membranes of microorganisms, resulting in a loss of membrane integrity, altering its permeability, and leading to the loss of ions and proteins [13]. Benzaldehyde (fruity) is another significant compound, known as an inhibitor of quorum sensing for the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa [14]. Hexanoic acid (fatty) has been considered to have high sensory potential effects in Chinese ‘Marselan’ wines [15]. Additionally, 2-undecanone (fruity) is known for its antifungal activity against Colletotrichum gloesporioides [16]. Another property of this compound is its ability to alleviate asthma by reducing airway inflammation and remodeling. This beneficial effect is achieved through the inhibition of the NF-κB pathway [17].

Among the unique compounds in the Brazilian HM (Table 3), notable ones include 1-octen-3-ol (earthy), known for its antioxidant and antimicrobial properties [18]. This compound acts as a defense mechanism in seaweeds [19], potentially enhancing food preservation and contributing to overall health. It is also associated with aging flavors [18]. 1-Hexanol (herbal) is found abundantly in Pale Ale and Lambic beer styles [20] and holds significant potential for applications in the food and cosmetic industries [21]. Ethyl hexanoate (fruity), providing flavors typical of apples and pineapples, is a maturity marker in pequi fruits (Caryocar brasiliense) and is the most predominant compound in this fruit [22]. Methyl isobutyrate (fruity) can be detected in numerous foods and beverages and has been identified as a key volatile compound in Hunan Changde rice noodles fermented with Lactococcus [23]. Hexyl acetate is frequently used as a flavoring agent in a variety of food products, including candies, baked goods, and beverages. It is also an ingredient in perfumes, soaps, and other personal care products [24]. Moreover, the hexyl acetate identified in the grape pomace of the investigated grape varieties can be used similarly, serving as a flavoring agent in various food items and as a component in perfumes, soaps, and other personal care products [21]. This ester is also known for imparting a fragrance known as ‘Orange Beauty’ [25].

Among the most expressed compounds in the Brazilian HM, noteworthy ones include methyl heptanoate (fruity), which contributes to a fruity flavor and is found in various fruits. Methyl octanoate (waxy) adds a smooth, sweet flavor, common in some fruits and wines, and is one of the main flavoring agents in foods, possessing a vinous, fruity, and orange-like odor [26]. Octanol (waxy) has a pleasant aroma that contributes to the complexity of flavors in foods and is common in various beer styles [20].

3.4. Magnum

Unlike H. Mittelfrüher, Magnum is a hop variety that showed a lower α-acid content when planted in Brazil, according to its suppliers (Table 1). Regarding the quantity of compounds, calculated by % area, 26 compounds were more expressed in the German Magnum, while 20 were more expressed in the variety planted in Brazil (Table 2). Of the 26 more expressed in the German Magnum, 17 are related to aroma or odor. Of the 23 compounds more expressed in the Brazilian Magnum, 11 are related to aroma or odor. Regarding the compounds found in the German Magnum, 34 unique compounds were identified compared to the Brazilian Magnum (Table 3). Of this total, only 22 are related to aroma. In the Brazilian Magnum, seven unique compounds were found compared to the German Magnum. Among them, six are related to aroma.

The German Magnum hop profile is characterized by a blend of herbal, terpenic, woody, citrus, fruity, floral, and fatty notes. The key compounds contributing to this profile include alpha-pinene (herbal), alpha-phellandrene (terpenic), and geranyl butyrate (fruity), among others. The Brazilian Magnum exhibits a profile with fruity, floral, and woody notes. The key compounds responsible for this profile include 2-methylpropyl 3-methylbutanoate (fruity), methyl heptanoate (fruity), and (+)-delta-cadinene (herbal). The aromatic profiles of the German and Brazilian Magnum hop varieties are influenced by the specific compounds present in each group. The German Magnum is characterized by a complex mix of herbal, fruity, and woody notes, while the Brazilian Magnum is dominated by fruity, floral, and herbal aromas. These differences are due to the unique combination of compounds present in each group, influenced by factors such as terroir and cultivation practices.

Beer flavored with total Magnum hop oil has a unique sensory profile, featuring strong “crushed grass, sap”, “resinous”, “earthy”, and “musty” aromas. Magnum hop oil consists mainly of β-myrcene, β-caryophyllene, and α-humulene, making up to 80% of the oil. β-myrcene, the most abundant compound, can smell “spicy”, “resinous”, “metallic”, or “geranium-like” at different concentrations. The aromas of β-caryophyllene and α-humulene are less distinct but are described as “rubber-like”, “mouldy”, “woody”, and “spicy.” These aroma characteristics are also found in sesquiterpene-flavored beer, but at lower intensities, indicating that the total oil enhances them [27].

3.5. Nugget

In contrast to the hops mentioned in the previous sections, the α-acid content was the same in both the American and Brazilian Nugget (Table 1). Regarding the quantity of compounds, calculated by % area, 25 compounds were more expressed in the variety planted in the United States, while 19 were more expressed in the variety planted in Brazil (Table 2).

Among the 25 compounds more expressed in the American Nugget, 17 are related to aroma or odor (Table 2). Among the 19 compounds more expressed in the Brazilian Nugget, 7 are related to aroma or odor. Regarding the compounds found in the variety planted in the United States, 42 unique compounds were identified compared to the Brazilian Nugget (Table 3). Of this total, only 25 are related to aroma. In the Brazilian Nugget, 37 unique compounds were found compared to the American Nugget. Among them, 24 presented some relation to aroma.

Among the compounds most abundantly expressed in the American Nugget, notable ones include dextro-limonene (citrus), which is one of the primary compounds identified in the essential oil of Okoume (Aucoumea klaineana) [28], being studied for its bioactive constituents and antibacterial activities. Linalool (floral) is commonly found in large quantities in Indian Pale Ale beers but in smaller amounts in Pale Ale (IPA) [20]. 3-Methylbutyl 2-methylbutanoate (fruity) is reported to occur in foods such as apple brandy (Calvados), banana (Musa sapientum L.), cider (apple wine), date (Phoenix dactylifera L.), grape brandy, and passion fruit (Passiflora species), among others [29].

Among the compounds most abundantly expressed in the variety planted in Brazil, noteworthy is methyl octanoate (waxy), which, interestingly, was found in Annona crassiflora, known as marolo fruit from the cerrado biome. This species is one of the most consumed in the Brazilian Midwest, with this compound significantly contributing to its aroma [30].

Among the compounds found exclusively in the American Nugget, methyl isobutyrate (fruity) was previously mentioned as a volatile compound in Hunan Changde rice noodles fermented by Lactococcus [23] and is also an exclusive compound of Brazilian HM hops. Dimethyl disulfide (sulfurous) adds a sulfurous character, which is interesting for certain aromatic profiles. It is also one of the most abundant compounds in microwave-cooked radish (Raphanus sativus L.) oils [31]. Isovaleric acid (cheesy) imparts a cheesy character and was exclusively found in Bock beers [20], being perceived by many individuals as a very strong odor impression [32].

Among the compounds found exclusively in the Brazilian Nugget, hexyl acetate (fruity) is also an exclusive compound of Brazilian HM hops. It is a flavoring agent in a variety of food products and an ingredient in perfumes, soaps, and other personal care products [24]. Methyl dodecanoate (waxy) adds a waxy and sweet flavor and is one of the most variable compounds for distinguishing wine cultivars, contributing significantly to their sensory characteristics [33]. It was also isolated from the ethyl acetate extract of the culture filtrate of the probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum H24 [34]. 3-methylbutyl 3-methylbutanoate (fruity) contributes a fruity flavor, enhancing the complexity of the aroma. It is the most abundant compound in all of the flowering stages of Asian skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus renifolius, Araceae) [35] and is present in the odors of ripe bananas, guavas, and oranges. It is also found among the compounds that attract both sexes of the invasive African fruit fly Bactrocera invadens [36].

3.6. Saaz

The Saaz hop exhibits an α-acid content of 3.5 for the Czech, compared to 5.67 for the Brazilian (Table 1). Regarding the quantity of compounds, calculated by % area, 17 compounds were more expressed in the Czech Saaz, while 15 were more expressed in the Brazilian Saaz (Table 2).

Among the 17 compounds more expressed in the Czech Saaz, 10 are related to aroma or odor (Table 2). Of the 15 compounds more expressed in the Brazilian Saaz, 9 are related to aroma or odor. Regarding the compounds found in the variety planted in the Czech Saaz, 26 unique compounds were identified compared to the Brazilian Saaz (Table 3). Of this total, only 18 are related to aroma. In the Brazilian Saaz, 28 unique compounds were found compared to the Czech Saaz. Among them, 18 were related to aroma.

The differences in the aromatic profiles of the Czech and Brazilian Saaz are largely due to the variation in the expression of specific compounds, which are influenced by factors such as climate, soil, and cultivation practices. The presence of more spicy, earthy, woody, and floral compounds in the Czech Saaz suggests a more traditional and balanced aroma profile, while the Brazilian Saaz’s higher expressions of ethereal, herbal, fruity, and spicy compounds offer a unique and potentially more vibrant aroma.

These aromatic differences are crucial for brewers when selecting hops for specific beer styles, as the aroma profile of the hops can significantly influence the final product’s flavor and aroma. Understanding the specific compounds responsible for these aromas allows brewers to tailor their hop selections to achieve the desired sensory characteristics in their beers.

Regarding the compounds most expressed in Czech Saaz hops, linalool (floral) is commonly found in higher quantities in Indian Pale Ale beers [20]. 1-Octen-3-ol (earthy), known for its mushroom-like aroma, is a byproduct of the enzymatic degradation of linoleic acid and ethanol [37], and previous studies have shown that it functions as a defense compound in marine algae [19,38,39].

Among the compounds most expressed in Brazilian Saaz hops, benzaldehyde (fruity) primarily manifests as a sweet note. Regarding the unique compounds in Czech Saaz hops, isovaleric acid (cheesy) is noted for its sweaty–cheesy aroma and contributes to the sensory characteristics of Gouda cheese [40]. Hexanoic acid (fatty) plays a role in aromatic complexity and has been documented for its effects in Chinese wines [15].

For the unique compounds in Brazilian Saaz hops, hexyl acetate (fruity) is widely used in the food and cosmetic industries [24], is present in grape pomace [21], and is recognized for its distinct ‘Orange Beauty’ fragrance [25]. 3-Methylbutyl 3-methylbutanoate (fruity) contributes a fruity flavor and is the predominant compound in the flowering of Symplocarpus renifolius, Araceae [35].

3.7. Sorachi Ace

The Sorachi Ace (SA) hop exhibits an α-acid content of 10.8 in the American, while the Brazilian SA has an α-acid content of 8.7 (Table 1). Regarding the quantity of compounds, calculated by % area, 24 compounds were more expressed in the American SA, whereas 21 were more expressed in the Brazilian SA (Table 2).

Of the 24 compounds more expressed in the American SA, 13 are related to aroma or odor (Table 2). Of the 21 compounds more expressed in the Brazilian SA, 12 are related to aroma or odor. Regarding the compounds found in the American SA, 17 unique compounds were identified compared to the same Brazilian SA (Table 3). Of this total, only 13 are related to aroma.

In the Brazilian SA, 25 unique compounds were found compared to the American SA, among them, 17 have some relation to aroma.

The American SA tends to have a more diverse aromatic profile with herbal, citrus, and woody notes being dominant. The presence of compounds like 2,6,6-trimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]hept-2-ene and dextro-limonene significantly contribute to the herbal and citrus characteristics. The Brazilian SA exhibits a more fruity and spicy aromatic profile. Compounds such as myrcene and 3-methylbut-2-enyl 2-methylpropanoate are responsible for these attributes, providing a unique aroma compared to its American counterpart. The presence and concentration of specific volatile compounds influence the aromatic profile. Terpenes and esters are particularly important, as they are responsible for the distinct aromas of hops, affecting beer’s aroma and flavor. The unique environmental conditions and cultivation practices in the US and Brazil likely contribute to the differences in these aromatic compounds, resulting in variations in the hop profiles.

Sorachi Ace is a hop variety that imparts distinctive varietal aromas to the final beer, including woody, pine, citrus, dill, and lemongrass notes. The research concludes that the unique aroma of Sorachi Ace hops is due to the high levels of geranic acid, which acts synergistically with other hop-derived compounds to enhance the overall aroma. Sensory evaluations showed that late and dry hopping resulted in beers with significantly higher scores for flowery, fruity, tropical, and lemon characteristics compared to kettle-hopped beer [41].

Regarding the compounds most expressed in the American SA, we can highlight dextro-limonene (citrus), which is a compound exclusively found in the Gose style compared to other sours [20]. It is found in the essential oil of okoume [28] and also acts against the cytoplasmic membranes of microorganisms [13]. Benzaldehyde (fruity) provides fruity notes. Linalool (floral) is common in IPA. Regarding the compounds most expressed in the Brazilian SA, we can highlight 3-methylbut-2-enyl 2-methylpropanoate (fruity), which is one of the exclusive compounds found in the Farmhouse Ale beer style. 1-Octen-3-ol (earthy) is known for being an antioxidant and antimicrobial [18], acting as a defense mechanism in marine algae [19], and is associated with the aging of flavors [18]. This compound is produced from 10-linoleate hydroperoxide [42] and is the most abundant alcohol found in soybeans cultivated in North America [43]. 2-Nonanone (fruity) is a bioactive compound capable of promoting rice growth [44]. It was identified in the volatilome of Bacillus sp. BCT9, showing the ability to increase lettuce biomass by up to 48% after 10 days of exposure [45]. Regarding the compounds exclusive to the American SA, we can highlight isovaleric acid (cheesy), which, as discussed, is found exclusively in Bock beers [20] and has a strong impression on individuals [32]. Camphene (woody) is a component of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) essential oil (Hendel et al., 2024). 1-Hexanol (herbal) is found in Lambic and Pale Ale beers [20] and has potential applications in the food industry (Abreu et al., 2023). Methyl heptenone (citrus) is a compound that signals freshness in algae (Cladostephus spongiosus) [46]. Hannaella and Neomicrosphaeropsis showed a significantly positive correlation with this compound produced during the fermentation of Petit Manseng sweet wine [47].

Regarding the compounds exclusive to the Brazilian SA, we can highlight hexyl acetate (fruity). As discussed, it is an important compound for food and perfume [24]. Octyl acetate (floral) is an exclusive compound found in Pilsen beers with hop extract [20], as well as in the Quadruppel beer style as an exclusive compound [20]. This compound is a useful marker for monitoring the fermentation process, as its post-fermentation concentration increases proportionally to the pre-fermentation concentration of the corresponding alcohol [48]. Large amounts of this compound have also been associated with potential antioxidant and anticancer effects in the leaves of the Pittosporum species (Pittosporaceae) [49]. Pentyl propanoate (fruity), which is a metabolic product derived from 1-pentanol, is an important flavoring ingredient formed by the condensation of pentanol and propanoic acid. The fruity smell of esters makes them unique, with wide applications in the flavor, fragrance, and solvent industries [50]. This compound is also found in truffles (Tuber canaliculatum) harvested in Quebec, Canada [51]. Alpha-Phellandrene (terpenic) is a compound found in the industrial product Monash Pouch diet, although its role in the flavor of this product is still unknown [52]. 3-Methylpentanoic acid (animal) receives special attention due to its peculiar aroma and its importance for fermented beverages. Acids can be obtained by lipid oxidation or by the conversion of aldehydes or ketones. Additionally, acids can react with alcohols to form esters and provide wine aroma, among them 3-methylpentanoic acid [53], which is also found in rice wine [54]. The presence of this compound seems to be stable in amounts in different wines [55] and has also been described in beers [56]. It is interesting to note that this aroma is present in the Brazilian SA, which can be very interesting for the country’s scenario. Recently, Brazil developed its first beer style, the Catharina sour. This style has been studied [57,58] and has already shown complexity in its volatile compound composition [20]. Thus, this could be a good hop for the local production of Catharina sour-style beers, even to enhance the flavor.

3.8. The Brazilian Touch in Hops

Regarding hops cultivated in Brazil, we observed a pattern, specifically compounds that were present in higher quantities or exclusively in all Brazilian-cultivated varieties. All varieties showed a higher amount of methyl 6-methylheptanoate (unrelated to aroma) and lower amounts of 3-(4-methylpent-3-enyl) furan (woody), linalool (floral), and 2-undecanone (fruity). Concerning exclusive compounds, none were found to be common in all varieties planted in Brazil. However, some are frequent in more than one hop. Pentyl propanoate (fruity), hexyl acetate (fruity), and 2-methylpropyl propanoate (fruity) were found in all hops except H. Mittelfrüher. Geranyl propionate (floral) was found in all except Magnum. Octyl acetate (floral) and octyl propanoate (fruity) were absent only in the German varieties H. Mittelfrüher and Magnum. Cis-3-hexenyl butyrate (green) and Geranyl acetate (floral) were absent only in the varieties H. Mittelfrüher and Sorachi Ace.

Regarding hops cultivated in their places of origin, isovaleric acid (cheesy) was the only exclusive compound found in all varieties. Dimethyl disulfide (sulfurous) was found in all except Sorachi Ace, while acetone (solvent) was found in all except Magnum, and dodecane (alkane) in all except H. Mittelfrüher. Methyl caproate (fruity), alpha-cadinol (herbal), and camphene (woody) were found in all American hops, possibly indicating a terroir effect.

H. Mittelfrüher and Magnum strains, which are German strains, have shown unique compounds compared to the German hop versus the Brazilian ones. Fourteen compounds are common between the H. Mittelfrüher and Magnum strains planted in Germany (Table 3), seven of which are aromatic, namely 2-methyl-1-butanol (ethereal); methyl isobutyrate (fruity); dimethyl disulfide (sulfurous); alpha-phellandrene (terpenic); isovaleric acid (cheesy); heptyl isobutyrate (fruity); and linalool oxide (earthy); while two compounds are common between the H. Mittelfrüher and Magnum strains planted in Brazil, namely alpha-muurolene (herbal) and beta-bisabolene (green).

It is given that H. Mittelfrüher and Magnum are both cultivated in the same region in Germany, known as Hallertau in Bavaria, and our Brazilian hop also originates from the same region. The cultivation in Germany would suggest a hop with more fruity, earthy, and cheesy notes, while in Brazil, it would suggest more herbal and green notes. Of course, further studies would be necessary to confirm this.

4. Conclusions

The analysis conducted through PLS-DA revealed significant variations in the aromatic profiles of hops cultivated in Brazil compared to their native counterparts, uncovering a total of 330 distinct volatile compounds. The differences in volatile compounds among the varieties, such as Hallertauer Mittelfrüher, Magnum, Nugget, Saaz, and Sorachi Ace, reflect the influence of terroir and cultivation conditions. Although the α-acid content of Nugget is similar between the Brazilian and American samples, the Magnum hop grown in Brazil stood out for its more fruity and floral profile. The Brazilian Saaz, on the other hand, exhibited an increase in α-acid content and fruity compounds compared to its Czech counterpart. These variations not only enrich the sensory complexity of beers but also open new opportunities for innovations in the industry, allowing brewers to select hops suitable for different styles, thereby enhancing the diversity and quality of the beverages produced.

Acknowledgments

The staff of the School of Pharmaceutical Sciences of the University of São Paulo for their support

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/plants13192675/s1: Table S1: Quantification of volatile compounds by Area% identified in the hops (Humulus lupulus) variety of Hallertauer Mittelfruher, Magnum, Nugget, Saaz, and Sorachi Ace, planted in Germany (DE), United States (USA), Czech Republic (CZ), and Brazil (BR).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.E.H.; methodology, M.E.H. and O.B.; formal analysis, M.E.H. and O.B.; investigation, M.E.H. and O.B.; resources, M.E.H. and M.F.; data curation, M.E.H. and O.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.E.H.; writing—review and editing, M.E.H., O.B. and M.F.; supervision, M.F.; project administration, M.E.H.; funding acquisition, M.E.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP), fellowships #2019/02583-0 and 2021/08621-0.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Przybyś M., Skomra U. Hops as a source of biologically active compounds. Pol. J. Agron. 2020;43:83–102. doi: 10.26114/pja.iung.438.2020.43.09. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kowalska G., Bouchentouf S., Kowalski R., Wyrostek J., Pankiewicz U., Mazurek A., Sujka M., Włodarczyk-Stasiak M. The hop cones (Humulus lupulus L.): Chemical composition, antioxidant properties and molecular docking simulations. J. Herb. Med. 2022;33:100566. doi: 10.1016/j.hermed.2022.100566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almaguer C., Schönberger C., Gastl M., Arendt E.K., Becker T. Humulus lupulus—A story that begs to be told A review. J. Inst. Brew. 2014;120:289–314. doi: 10.1002/jib.160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tyśkiewicz K., Gieysztor R., Konkol M., Szałas J., Rój E. Essential oil from Humulus Lupulus scCO2 extract by hydrodistillation and microwave-assisted hydrodistillation. Molecules. 2018;23:2866. doi: 10.3390/molecules23112866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Franco L., Sánchez C., Bravo R., Rodríguez A.B., Barriga C., Romero E. The sedative effect of non-alcoholic beer in healthy female nurses. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e37290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miranda C.L., Stevens J.F., Helmrich A., Henderson M.C., Rodriguez R.J., Yang Y.H., Deinzer M.L., Barnes D.W. Antiproliferative and cytotoxic effects of prenylated flavonoids from hops (Humulus lupulus) in human cancer cell lines. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1999;37:271–285. doi: 10.1016/S0278-6915(99)00019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevens J.F., Page J.E. Xanthohumol and related prenylflavonoids from hops and beer: To your good health! Phytochemistry. 2004;65:1317–1330. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartsel J.A., Eades J., Hickory B., Makriyannis A. Nutraceuticals. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2016. Cannabis sativa and hemp. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rufino A.T., Ribeiro M., Sousa C., Judas F., Salgueiro L., Cavaleiro C., Mendes A.F. Evaluation of the anti-inflammatory, anti-catabolic and pro-anabolic effects of E.-caryophyllene, myrcene and limonene in a cell model of osteoarthritis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015;750:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rettberg N., Biendl M., Garbe L.A. Hop aroma and hoppy beer flavor: Chemical backgrounds and analytical tools-A review. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2018;76:1–20. doi: 10.1080/03610470.2017.1402574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su X., Yin Y. Aroma characterization of regional Cascade and Chinook hops (Humulus lupulus L.) Food Chem. 2021;364:130410. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Araldi L., Sato A.J., Leles N.R., Roberto S.R., Jastrombek J.M., Rufato L. Caracterização química da cultivar Hallertau Mittelfrüher cultivada na região oeste do Paraná. In: Anais do Seminário Mercosul de Bebidas. Anais, Cascavel(PR) Fundetec. Disponível em: 2022. [(accessed on 18 July 2024)]. Available online: https://www.even3.com.br/anais/9seminariodebebidas/546295-CARACTERIZACAO-QUIMICA-DA-CULTIVAR-HALLERTAU-MITTELFRUHER-CULTIVADA-NA-REGIAO-OESTE-DO-PARANA.

- 13.Zhang Z., Vriesekoop F., Yuan Q., Liang H. Effects of nisin on the antimicrobial activity of d-limonene and its nanoemulsion. Food Chem. 2014;150:307–312. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.10.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woods K.E., Akhter S., Rodriguez B., Townsend K.A., Smith N., Smith B., Wambua A., Craddock V., Abisado-Duque R.G., Santa E.E., et al. Characterization of natural product inhibitors of quorum sensing reveals competitive inhibition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa RhlR by ortho-vanillin. Microbiol. Spectr. J. 2024;12:e0068124. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.00681-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y., Li C., Ge Q., Huo X., Ma T., Fang Y., Sun X. Geographical characterization of wines from seven regions of China by chemical composition combined with chemometrics: Quality characteristics of Chinese ‘Marselan’ wines. Food Chem. X. 2024;23:101606. doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2024.101606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurmanbayeva A., Ospanov M., Tamang P., Shah F.M., Ali A., Ibrahim Z.M.A., Cantrell C.L., Dinara S., Datkhayev U., Khan I.A., et al. Regioselective Claisen-Schmidt adduct of 2-undecanone from Houttuynia cordata thunb as insecticide/repellent against Solenopsis invicta and repositioning plant fungicides against Colletotrichum fragariae. Molecules. 2023;28:6100. doi: 10.3390/molecules28166100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song G., Yu S., Zhang Y., Sun M., Zhang B., Peng M. 2-Undecanone alleviates asthma by inhibiting NF-κB pathway. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2023;101:101–111. doi: 10.1139/bcb-2022-0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng Y., Meng Y., Xu L., Yu H., Guo Y., Xie Y., Yao W., Qian H. Study on the correlations between quality indicators of dry-aged beef and microbial succession during fermentation. Foods. 2024;13:1552. doi: 10.3390/foods13101552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jerković I., Radman S., Jokić S. Distribution and Role of Oct-1-en-3-ol in Marine Algae. Compounds. 2021;1:125–133. doi: 10.3390/compounds1030011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herkenhoff M.E., Brödel O., Frohme M. Aroma component analysis by HS-SPME/GC–MS to characterize Lager, Ale, and sour beer styles. Food Res. Int. 2024;194:114763. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2024.114763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abreu T., Jasmins G., Bettencourt C., Teixeira J., Câmara J.S., Perestrelo R. Tracing the volatilomic fingerprint of grape pomace as a powerful approach for its valorization. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023;7:100608. doi: 10.1016/j.crfs.2023.100608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.da Costa C.A.R., do Nascimento S.V., da Silva Valadares R.B., da Silva L.G.M., Machado G.G.L., da Costa I.R.C., Nahon S.M.R., Rodrigues L.J., Vilas Boas E.V.B. Proteome and metabolome of Caryocar brasiliense camb. fruit and their interaction during development. Food Res. Int. 2024;191:114687. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2024.114687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang A.X., Yi C., Xiao T., Qin W., Chen Z., He Y., Wang L., Liu L., Wang F., Tong L.T. Volatile compounds, bacteria compositions and physicochemical properties of 10 fresh fermented rice noodles from southern China. Food Res. Int. 2021;150 Pt A:110787. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Melo Pereira G.V., Medeiros A.B.P., Camara M.C., Magalhães Júnior A.I., De Carvalho Neto D.P., Bier M.C.J., Soccol C.R. The Role of Alternative and Innovative Food Ingredients and Products in Consumer Wellness. Academic Press; Cambridge, MA, USA: 2019. Production and recovery of bioaromas synthesized by microorganisms; pp. 315–338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y., Gong Z., Zhu Z., Sun J., Guo W., Zhang J., Ding P., Liu M., Gao Z. Identification of floral aroma components and molecular regulation mechanism of floral aroma formation in Phalaenopsis. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024 doi: 10.1002/jsfa.13742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Food Safety and Quality: Online Edition “Specifications for Flavourings”. 2021. [(accessed on 1 August 2024)]. Available online: http://www.fao.org/food/food-safety-quality/scientific-advice/jecfa/jecfa-flav/details/en/c/220/

- 27.Dietz C., Cook D., Wilson C., Oliveira P., Ford R. Exploring the multisensory perception of terpene alcohol and sesquiterpene rich hop extracts in lager style beer. Food Res. Int. 2021;148:110598. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aghoutane Y., Moufid M., Motia S., Padzys G.S., Omouendze L.P., Llobet E., Bouchikhi B., El Bari N. Characterization and analysis of okoume and aiele essential oils from gabon by GC-MS, electronic nose, and their antibacterial activity assessment. Sensors. 2020;20:6750. doi: 10.3390/s20236750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Api A.M., Belsito D., Botelho D., Bruze M., Burton G.A., Jr., Cancellieri M.A., Chon H., Dagli M.L., Date M., Dekant W., et al. RIFM fragrance ingredient safety assessment, 3-methylbutyl 2-methylbutanoate, CAS Registry Number 27625-35-0. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022;167((Suppl. S1)):113276. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2022.113276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carvalho N.C.C., Monteiro O.S., da Rocha C.Q., Longato G.B., Smith R.E., da Silva J.K.R., Maia J.G.S. Phytochemical analysis of the fruit pulp extracts from Annona crassiflora mart. and evaluation of their antioxidant and antiproliferative activities. Foods. 2022;11:2079. doi: 10.3390/foods11142079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jia X., Yu P., An Q., Ren J., Fan G., Wei Z., Li X., Pan S. Identification of glucosinolates and volatile odor compounds in microwaved radish (Raphanus sativus L.) seeds and the corresponding oils by UPLC-IMS-QTOF-MS and GC × GC-qMS analysis. Food Res. Int. 2023;169:112873. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2023.112873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ritter S.W., Ensslin S., Gastl M.I., Becker T.M. Identification of key aroma compounds of faba beans (Vicia faba) and their development during germination-a SENSOMICS approach. Food Chem. 2024;435:137610. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.137610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao F., Guan L., Zeng G., Hao X., Li H., Wang H. Preliminary characterization of chemical and sensory attributes for grapes and wines of different cultivars from the Weibei Plateau region in China. Food Chem. X. 2023;21:101091. doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2023.101091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Momo C.H.K., Mboussaah A.D.K., François Zambou N., Shaiq M.A. New pyran derivative with antioxidant and anticancer properties isolated from the probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum H24 strain. Nat. Prod. Res. 2022;36:909–917. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2020.1849201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oguri S., Sakamaki K., Sakamoto H., Kubota K. Compositional changes of the floral scent volatile emissions from Asian skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus renifolius, Araceae) over flowering sex phases. Phytochem. Anal. 2019;30:139–147. doi: 10.1002/pca.2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Biasazin T.D., Karlsson M.F., Hillbur Y., Seyoum E., Dekker T. Identification of host blends that attract the African invasive fruit fly, Bactrocera invadens. J. Chem. Ecol. 2014;40:966–976. doi: 10.1007/s10886-014-0501-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morawicki R.O., Beelman R.B. Study of the biosynthesis of 1-octen-3-ol using a crude homogenate of Agaricus bisporus in a bioreactor. J. Food Sci. 2008;73:C135–C139. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herrero-Garcia E., Garzia A., Cordobés S., Espeso E.A., Ugalde U. 8-Carbon oxylipins inhibit germination and growth, and stimulate aerial conidiation in Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal Biol. 2011;115:393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jian Q., Zhu X., Chen J., Zhu Z., Yang R., Luo Q., Chen H., Yan X. Analysis of global metabolome by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry of Pyropia haitanensis stimulated with 1-octen-3-ol. J. Appl. Phycol. 2017;29:2049–2059. doi: 10.1007/s10811-017-1108-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duensing P.W., Hinrichs J., Schieberle P. Influence of milk pasteurization on the key aroma compounds in a 30 weeks pipened pilot-scale gouda cheese elucidated by the sensomics approach. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024;72:11062–11071. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.4c01813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanekata A., Tanigawa A., Takoi K., Nakayama Y., Tsuchiya Y. Interesting behavior of geranic acid during the beer brewing process: Why could geranic acid remain at a higher level only in the beer using Sorachi Ace hops? J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023;71:18489–18498. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.3c04740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Y., Guo S., Liu Z., Chang S.K. Off-flavor related volatiles in soymilk as affected by soybean variety, grinding, and heat-processing methods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60:7457–7462. doi: 10.1021/jf3016199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim S.Y., Kim S.Y., Lee S.M., Lee D.Y., Shin B.K., Kang D.J., Choi H.K., Kim Y.S. Discrimination of cultivated regions of soybeans (Glycine max) based on multivariate data analysis of volatile metabolite profiles. Molecules. 2020;25:763. doi: 10.3390/molecules25030763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Almeida O.A.C., de Araujo N.O., Mulato A.T.N., Persinoti G.F., Sforça M.L., Calderan-Rodrigues M.J., Oliveira J.V.C. Bacterial volatile organic compounds (VOCs) promote growth and induce metabolic changes in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2023;13:1056082. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1056082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fincheira P., Quiroz A. Physiological response of Lactuca sativa exposed to 2-nonanone emitted by Bacillus sp. BCT9. Microbiol. Res. 2019;219:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hendel N., Sarri D., Sarri M., Napoli E., Palumbo Piccionello A., Ruberto G. Phytochemical Analysis and Antioxidant and Antifungal Activities of Powders, Methanol Extracts, and Essential Oils from Rosmarinus officinalis L. and Thymus ciliatus Desf. Benth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024;25:7989. doi: 10.3390/ijms25147989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma Y., Li T., Xu X., Ji Y., Jiang X., Shi X., Wang B. Investigation of Volatile Compounds, Microbial Succession, and Their Relation During Spontaneous Fermentation of Petit Manseng. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12:717387. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.717387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dennis E.G., Keyzers R.A., Kalua C.M., Maffei S.M., Nicholson E.L., Boss P.K. Grape contribution to wine aroma: Production of hexyl acetate, octyl acetate, and benzyl acetate during yeast fermentation is dependent upon precursors in the must. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60:2638–2646. doi: 10.1021/jf2042517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]